Abstract

Political factors are widely acknowledged determinants of local environmental outcomes, yet their precise influence on air pollution, particularly in the context of leadership transitions, remains a subject of ongoing debate without a clear consensus. This study addresses this gap by investigating the impact of changes within China’s dual local political system—the government and Party systems—on air quality in prefectural-level cities. Leveraging mayoral turnover and Party secretary turnover as indicators of these system changes, we analyze their impact on local air pollution levels. Utilizing a difference-in-difference model, we estimate the effects using monthly data on local political official turnover and air quality collected from 337 Chinese cities over a 36-month period. Our findings reveal significant and differentiated short-term impacts of mayoral and Party secretary turnover on local air pollution. Specifically, we observe a deterioration in air quality in the months following mayoral turnover, while Party secretary turnover shows no significant immediate impact. Furthermore, the effect of mayoral turnover is heterogeneous, varying significantly with regional characteristics, the geographic origin and age of the newly appointed official, the former official’s tenure, and the central government's environmental inspections. This research contributes to understanding the distinct roles of different local political leadership in shaping environmental governance outcomes in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past four decades, China has achieved remarkable economic progress since the initiation of reform and opening-up in 1978. However, this economic boom has been accompanied by severe environmental consequences, notably escalating air pollution, which now poses a significant obstacle to sustainable economic development (He and Chen 2022; Wang et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2014). In response to this environmental degradation, both central and local Chinese authorities have implemented a range of regulatory measures and policies aimed at mitigating pollution. These measures include the “one-vote veto” system for environmental protection, the green performance assessment system, and rigorous central environmental protection inspections. These interventions have led to gradual improvements in air quality (Lu, 2022; Yin and Wu, 2022). Nevertheless, challenges persist, with air pollution remaining a significant issue across many prefecture-level jurisdictions (Shao and Chou, 2023; Tang et al., 2024).

On a global scale, the issue of air pollution has been thoroughly documented, particularly in emerging markets. A growing body of literature has identified the nexus between political factors and the issue of air pollution, encompassing elements such as the political cycle (e.g., Cao et al., 2019), policy uncertainty (e.g., Wu et al., 2023), shifts in political leadership (e.g., He and Chen, 2022; Song et al., 2021), anti-corruption initiatives (e.g., Ivanova, 2011; Zhou et al., 2020), and political promotion incentives (e.g., Tang et al., 2024; Yin and Wu, 2022). Research indicates that the political cycle can significantly impact air pollution levels (e.g., Cao et al., 2019; Tian and Tian, 2021; Wang and Lin, 2024). For instance, Shao and Chou (2023) found that air quality in Chinese cities was significantly improved surrounding the annual Party Congress. Moreover, the turnover of local political officials has been associated with fluctuations in local air pollution (Deng et al., 2019; Yin and Wu, 2022). For example, using the regression discontinuity method, Chen and Gao (2020) demonstrated a negative influence of local official turnover on local air quality in Chinese cities. Similarly, Deng et al. (2019) exhibited that the local political official turnover was associated with an increase in the discharge of firm pollutants. In contrast, Zhu and Yang (2023) found significant reductions in firm pollutant emissions in the year that the local political official rotated. Furthermore, anti-corruption measures and central environmental inspections have been demonstrated to effectively curb government-firm “collusion”, thereby leading to a reduction in pollutant emissions and an improvement in air quality. For Chinese cities, Zhou et al. (2020) suggested that the national anti-corruption campaign led to approximately a 20% reduction in air pollution, and Lin et al. (2021) demonstrated that the central environmental protection inspections were effective in reducing air pollutants such as PM2.5, PM10, SO2, and NO2.

In China, the influence of political factors on air quality is considerably more complex, largely due to the unique local political system. In general, local authorities in prefectural-level cities operate under a dual leadership structure: the Party system and the government system, led separately by the municipal Party secretary and the mayor (Cai, 2008; Song et al., 2021). The Party secretary is in charge of implementing the Communist Party of China (CPC) policies, setting the “vision” and “strategy” of local development, and overseeing the operation of the local government system; while the mayor is responsible for daily government administration, especially local economic development and public services. Importantly, the municipal Party secretary outranks the mayor in the Chinese political hierarchy. Despite the significance of this dual leadership system, research specifically examining its impact on regional air quality remains limited.

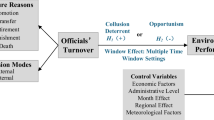

This paper aims to address this research gap by investigating how changes in the local political system—specifically mayoral turnover and Party secretary turnover—affect air quality in prefectural-level cities. Leveraging monthly data on local political official turnover and air quality, our difference-in-difference modeling approach yields several key findings. First, our findings reveal differentiated short-term impacts: changes within the local government system, i.e., mayoral turnovers, lead to a significant exacerbation of local air quality, whereas changes within the Party system, i.e., Party secretary turnovers, have no significant influence on local air quality. Second, the impact of mayoral turnover on local air quality varies significantly depending on factors such as regions, officials’ characteristics, and central governmental environment inspections. Specifically, the negative effect is more pronounced in eastern Chinese cities, for newly appointed mayors from outside the jurisdiction, in cities with longer-tenured former mayors, in cities with younger new mayors, and in cities not subject to central environmental protection inspections.

This study contributes marginally to the existing literature in two key areas. First, it expands on existing studies by systematically considering the influence of both mayoral turnover and Party secretary turnover on short-term fluctuations in local air quality. While prior literature has acknowledged the impacts of political official turnover on air quality, these studies have primarily focused on examining the role of the government system (typically represented by mayoral turnover), often neglecting the influence of the Party system (He and Chen, 2022; Zhu and Yang, 2023). Second, this study complements the theory of policy uncertainty by highlighting the specific pathways through which local political leadership changes, particularly mayoral turnover, impact local environmental outcomes.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section “Literature review and research hypotheses” reviews the relevant literature and formulates theoretical hypotheses. Section “Data, measurement, and model” presents the data collection, measurements, and analytical methods employed. Section “Results” presents the empirical findings and conducts robustness checks. Section “Heterogeneity analysis” delves further into the findings by conducting heterogeneity analyses. Section “Conclusion and implications” concludes and discusses the implications for practices and policymakers.

Literature review and research hypotheses

The theory of policy uncertainty

In this study, we draw upon policy uncertainty theory to explain the relationship between local air quality and government officials’ turnover. The concept of policy uncertainty has become increasingly recognized by academics since the publication of John Kenneth Galbraith’s book The Age of Uncertainty in 1977. It was initially associated with economic sectors like finance or trading, defined with two components in Pástor and Veronesi’s research (2013). First, political uncertainty, uncertainty caused by future government actions. Second, impact uncertainty, uncertainty about the impact of future government actions. In empirical research, researchers normally capture policy uncertainty in three dimensions: the specific individuals who make policy decisions, the specific policy decisions made by the new leaders, and how particular policy decisions will affect other observed variables. Influential research by Baker et al. (2016) developed a widely used index of economic policy uncertainty (EPU) based on newspaper coverage frequency. They found that policy uncertainty was associated with greater stock price volatility and reduced investment and employment. Handley and Nuno’s model (2017) developed another important model to quantify the effects of trade policy uncertainty (TPU) on U.S.-China trade. Broader evidence shows that the economic behaviors of companies and industries are strongly associated with political uncertainty and highly sensitive to the anticipated policy changes (Nguyen and Phan, 2018; Bonaime et al., 2018).

In the application of the policy uncertainty model, official turnover has become one of the most convenient variables because of its easier access to be collected and measured compared with other measures. Julio and Yook (2012) explored the uncertainty around American election years and found that it led firms to shrink their investments. Chen et al. (2018) further examined the impact of policy uncertainty, proxied by national elections, on foreign direct investment through 126 countries’ data over 20 years. In China’s unique political context, the frequent turnover of officials under the cadre promotion system and the policy uncertainty it triggers are often considered a contributing factor to ineffective environmental regulations and inefficient pollution control (Wu et al., 2023). However, relatively few studies have directly combined these two using empirical methods, particularly in the context of local environment governance (Huang et al., 2023). Unlike existing literature, this study argues that local officials’ turnover, specifically the turnover of mayors and municipal Party secretaries, causes policy uncertainty, which in turn worsens local air quality.

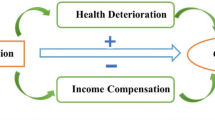

The mayoral turnover and local air quality

In the Chinese bureaucratic system, mayors of prefectural-level cities play a pivotal role in driving local economic development. Research indicates that mayoral turnover typically triggers a reconfiguration of the local economic system and a reallocation of local economic resources, which can have negative effects on local air quality (Li and Zhou, 2005; Man, 2016). First, under the inherent pressure of political tournaments, newly appointed mayors tend to prioritize stimulating local GDP growth over achieving a harmonious balance between economic development and environmental protection. According to the political tournament perspectives, local political officials are assessed by their upper-level government and get promoted if local economic growth outperforms their counterparts (Su et al., 2012; Xu, 2011). Consequently, engrossed in promotion competition, local political leaders have scant motivation to improve local environmental quality (Chen and Gao, 2020; He and Chen, 2022; Man, 2016). To gain political promotion faster, newly appointed political officials often resort to proactive economic policies, such as attracting large-scale industrial investment at the beginning of their tenure, to quickly catalyze short-term GDP gains and further demonstrate their potential in fostering local economic expansion. Additionally, facing tenure constraints, local officials are more inclined to invest in short-term projects with low costs and high returns, relegating long-term environmental governance to the periphery (Li and Zhou, 2005). Consequently, the incentive structures underpinning political promotion invariably dissuade and detract the focus of transferred local officials from local air quality improvement, leading to short-term environmental deterioration.

Second, the turnover of local mayors often induces uncertainty in local economic and environmental policy, confounding firms’ expectations regarding local environmental policy in the short term. Mayors have discretionary power to design and implement locally adapted economic and environmental policies during their tenure. Thus, mayoral turnover implies changes in local administration system that disrupt the continuity of policy implementation, leading to policy uncertainty (He and Chen, 2022; Wu et al., 2023). Policy uncertainty is detrimental to local environmental governance through weakening environmental regulations, inducing more pollutant emissions, demotivating green innovation, and potentially fostering firm-government collusion to evade environmental regulation (Cheng et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2023).

Third, local mayor turnovers may weaken environmental supervision, leading to increased pollutant emissions. Within the Chinese political system, mayors are usually the first person who bears the responsibility for local environmental governance (Cai, 2008). Mayor turnovers can signal a temporary lapse in focused environmental supervision in the jurisdiction. On the one hand, outgoing mayors would gradually shift their focus from local affairs to their new positions, thereby diluting the implementation and supervision of environment-related policies. On the other hand, incoming mayors require time and energy to adapt to new appointments, limiting their attention to local environmental governance. As a result, the lessening pressure of environmental supervision during the transition period following official turnover induces firms to escalate pollutant emissions (Deng et al., 2019).

Hypothesis 1 (H1) The mayoral turnover has a negative effect on local air quality in the short term.

The Party secretary turnover and local air quality

Within the Chinese leadership system, municipal Party secretaries normally serve as the primary decision-makers and hold a higher rank than mayors (Eaton and Kostka, 2014). Although the Party secretaries are mainly responsible for political leadership and personnel affairs, they are usually regarded as the final authority in charge of all regional affairs, including environmental governance. According to the Regulations of the Communist Party, the local Party committee takes the core leadership in local economics, social development, and ecological conservation of the region (Song et al., 2021). Considering the overlap of local administrative power, the turnover of municipal Party secretaries, who serve as the final decision makers, is viewed as related to the improvement of environmental quality. Consistent with policy uncertainty theory, a survey shows that the average tenure of municipal Party secretaries in prefecture-level cities is 3.2 years (Ji et al., 2022). Such short tenures can typically lead to greater and more frequent policy uncertainty.

Prior researchers have suggested that the turnover of Party secretaries plays a dynamic role in reducing environmental pollution in resource-exhausted cities (Zhang et al., 2017). With the establishment of the Central Environmental Protection Inspection (CEPI) as a key vertical supervision mechanism in China in 2016, common environmental responsibilities shared by both Party secretaries and mayors have been increasingly emphasized (Zeng et al., 2023). This has complicated the analysis, as official turnover has sometimes been treated generally, without distinguishing between mayors and Party secretaries, making it difficult to isolate their respective functions. Some analyses, treating turnover generally, have suggested that the turnover of either Party secretaries or mayors can increase air pollution to a certain extent (Chen and Gao, 2020). Given that Party secretaries play distinct roles from mayors in the Chinese administrative system, and the very mechanisms linking their turnover to air pollution remain unclear, it is necessary to distinguish the effect of Party secretaries’ turnover on local air quality from that of mayors. And this will be one of the contributions that our paper makes to previous research, trying to explain something unique in the Chinese context.

Hypothesis 2: The turnover of municipal Party secretary has a negative impact on local air quality in the short term.

Data, measurement, and model

Data collection

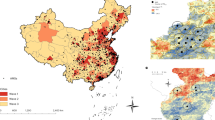

To test our research hypotheses, we construct a panel dataset covering 337 Chinese cities from 2015 to 2017. This includes 4 centrally-administrated municipalities (i.e., Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing) and 333 prefectural-level cities. This dataset integrates four distinct data sources, each contributing critical dimensions to our analysis, as detailed below.

Data on local political official turnover. We manually collected the resumes of local political officials, i.e., cities’ mayors and Party secretaries. First, we obtain the names of mayors and Party secretaries from Hotelaah (https://www.hotelaah.com/liren/index.html), a commercial website that maintains historical records of Chinese local political appointments (Wang et al., 2024). We then collected detailed personal information for these officials, including their place and date of birth, gender, education, and career records from a variety of authoritative sources. These sources include the People’s Daily (www.people.com.cn), the China Economic Net (http://district.ce.cn/zt/rwk/), the CPC News (www.cpcnews.cn), the official government web portals of prefectural and provincial administrations (e.g., The People’s Government of Beijing Municipality, www.beijing.gov.cn), and Baidu’s search engine (www.baidu.com). Leveraging these resumes, we systematically extract turnover information for mayors and Party secretaries across 337 cities, encompassing key details such as the timing of turnover events, the ages of local political officials, their prior positions, and their respective tenures.

Data on local air quality. This study utilizes air quality data obtained from the China Air Quality Online Monitoring and Analysis Platform (www.aqistudy.cn/historydata/), a publicly accessible and authoritative environmental monitoring resource in China. The dataset provides comprehensive city-level monthly measurements of key air pollutants, including particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) concentrations, with a temporal scope spanning from December 2013 to the present. As a reliable and extensively utilized data source in environmental research, this platform’s data has been empirically validated and widely adopted in previous scholarly investigations (e.g., Wu and Lin, 2019; Liu et al., 2023).

Social and economic data. We collected each city’s social and economic information, such as land area, population, gross domestic product (GDP), industrial employees, and manufacturing enterprises, from provincial statistical yearbooks and the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database (https://data.csmar.com/).

Meteorological data. We obtained detailed meteorological data at the city level, including critical variables such as precipitation, wind speed, and temperature. These data are sourced from the China Meteorological Data Service Center (https://data.cma.cn), the official platform for meteorological data in China, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of the measurements (Liu et al., 2023).

Subsequently, we construct our final data sample by integrating these four datasets using a city-month unit identifier. The resulting dataset covers 337 Chinese cities in a range of 36 months, from January 2015 to December 2017, offering a comprehensive and robust foundation for empirical analysis.

Measures

Local air quality

In this paper, we employ monthly PM2.5 concentration (PM25) as a proxy for local air quality. PM2.5, defined as fine particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less in ambient air, is widely recognized for its detrimental effects on both physical and mental health, rendering it a critical indicator of air pollution. In China, PM2.5 monitoring has become a priority for governments at all levels, with reducing PM2.5 concentrations established as a key objective in air pollution prevention and control policies. To ensure consistency with the existing literature, we adopt the PM2.5 indicator as our primary measure of local air quality, aligning with the usage of prior studies (e.g., Mardones and Cornejo, 2020; Wu and Cao, 2021). Specifically, we use the monthly average PM2.5 concentration to capture temporal variations in air quality.

Political official turnover

In the Chinese political system, local governance at the prefectural level is jointly managed by two key political leaders: the Party secretary, who is responsible for Party and personnel affairs, and overall political leadership; and the mayor, who administers economic growth, social development, environmental protection, education and public health affairs (Zuo, 2015). In this study, we define a political official as either the mayor or the Party secretary of a prefectural city or municipality. To operationalize political turnover, we systematically analyze the collected resumes of these officials to identify the timing of new appointments. Based on this approach, we construct two dummy variables to measure local political turnover: Mayor and PartySecret. The variable Mayor is coded as 1 if a new mayor is appointed for the city during the observation month and 0 otherwise. Similarly, PartySecret takes the value 1 if a new Party secretary is appointed for the city in the month and 0 otherwise. These measures align with established literature on Chinese local political leadership (e.g., Wang and Lin, 2024).

Control variables

Following the previous studies (e.g., Li et al., 2019; Song et al., 2021; Zheng and Na, 2020), this paper includes weather and economy-related factors in the model to control for the potential confounding effects. First, we consider weather factors, including temperature, rain, and wind speed. The existing literature indicates a direct influence of weather characteristics on regional air pollution (Zheng and Na, 2020). For instance, the concentration of PM10, indicative of particulate matter with a diameter of 10 microns or less in ambient air, is very dependent upon wind speed, whereas ozone is less likely to be formed under cloudy and cool weather (Fu and Gu, 2017). In line with previous studies, we include monthly average temperature (Temp), monthly cumulative precipitation (Rain), and monthly average wind speed (Wind) as control variables in the analytical model.

Second, we control for the socioeconomic factors at the prefectural level, including GDP per capita, population density, and industry-related variables, to account for their potential influence on environmental outcomes. The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) posits an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation, wherein pollution initially intensifies with industrialization but diminishes after surpassing a development threshold (Stern, 2004). Following empirical studies that have consistently demonstrated the significant impact of local economic development on environmental outcomes—such as pollution reduction and air quality deterioration (e.g., Shahbaz et al., 2013), we introduce the logarithm of a prefecture’s GDP per capita (Pgdp) to capture the effects of economic development. In addition, we control for the effect of population density, as demographic factors such as population size have been shown to significantly impact environmental outcomes, including air pollution (Li et al., 2019; Rahman and Alam, 2021). Accordingly, this study incorporates population density (Density), defined as the total population of a city divided by its total land area, as a control variable in the regression model. Furthermore, we account for industrial influences by introducing two key variables: the number of employees in the secondary industry (Employee) and the number of industrial enterprises with annual revenue exceeding 20 million Yuan (Firmscale), as larger industrial scale reflects higher resource consumption and industrial pollutant emissions (Cole et al., 2005).

Model

To explore the causal effects of political turnover on local air quality, we employ the staggered difference-in-difference (SDiD) estimation strategy, which is a variant of the basic DiD. The main reason for selecting this approach over the basic DiD is rooted in the nature of the political official turnover event, which does not occur simultaneously across all cities in the treatment group but instead occurs at different times in different cities, creating a “staggered treatment” situation. This violates the assumption that the treatment occurs at the same time for all units in the treatment group, a key assumption in the basic DiD model. Following Wing et al. (2024), this staggered timing of the turnover event allows for variation in exposure to the treatment, making the staggered DiD method more suitable for capturing the dynamic effects of political turnover on local air quality.

In this study, the treatment group comprises cities that experience political official turnover during the study period (January 2015 to December 2017), while the control group consists of cities that do not experience such turnover within the same timeframe. To better capture the short-term effects of political official turnover on local air quality, we define the event time window as the month when the official was appointed and the subsequent five months, in line with Guo and Shi (2017) and Chen and Gao (2020). This approach allows for a focused analysis of the immediate influence of political leadership changes on environmental outcomes, distinguishing it from longer-term effects (Guo and Shi, 2017).

In line with the considerations of previous studies (e.g., Zuo, 2015), we construct two separate regression models to examine the influence of mayoral turnover (Model 1) and Party secretary turnover (Model 2) on local air quality in Chinese cities. The specific models are as follows:

Where i, t, and j represent city, month, and political official, respectively. \({Y}_{i,t}\) denotes air quality (i.e., PM2.5) of city i in month t, while \({{Controls}}_{i,t}\) indicates a vector of control variables for city i at month t. The terms \({\mu }_{i}\), \({\delta }_{t}\), and \({\tau }_{j}\) represent city, month, and political official fixed effects, respectively. In particular, \({{Mayor}}_{i,t}\), and \({{Partysecrt}}_{i,t}\) represent whether a new mayor or Party secretary was appointed in city i at month t. In particular, \({{Mayor}}_{i,t}\) and \({{Partysecrt}}_{i,t}\) are dummy variables coded to 1 for the six-month event window described previously (t to t + 5) and 0 otherwise, consistent with prior literature (e.g., Chen and Gao, 2020; Guo and Shi, 2017), to capture the short-term effects. To address potential bias from group-specific autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity in the error terms, we cluster robust standard errors at the city level in our estimations. The coefficients \({\beta }_{1}\) and \({\beta }_{2}\) in Model 1 and Model 2, respectively, capture the influence of mayoral turnover and Party secretary turnover on local air quality during the defined 6-month post-turnover window, relative to the control group. The positive and significant \(\beta\) values indicate that the political turnover has a detrimental effect on local air quality (i.e., increased PM2.5 concentration).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics, correlation matrix, and variance inflation factors (VIFs) for the key variables. As observed, the turnover of local Party secretaries exhibits a slight negative correlation with PM2.5 concentration (\(\beta =-0.06\)), which is statistically significant at the 5% level. As for mayors, their turnover has a significant negative correlation with PM2.5 concentration (\(\beta =-0.02\)) at the 10% statistical level. Among the control variables, meteorological factors, including wind speed, temperature, and precipitation, demonstrate significant negative correlation with PM2.5 levels at the 5% statistical level. Conversely, socioeconomic factors, such as GDP per capita, population density, the number of employees in the secondary industry, and the number of industrial enterprises, show significant positive correlations with PM2.5 concentration. Furthermore, the VIF values for all independent variables remain well below the threshold value of 5, indicating the absence of substantial multicollinearity in the regression models.

Parallel trend test

Validation of the DiD analysis requires satisfying the parallel trend assumption. That is, in the absence of the treatment, the control group and the treated group would have followed the same outcome trend over time. To be specific, if the difference in PM2.5 concentration between the control and treated groups before the turnover event is not statistically significant, then our DiD model satisfies the parallel assumption. We set up event time dummies relative to the month of political official turnover; that is, M−6, M−5, M−4, M−3, M−2, and M−1 indicate the months before the turnover, M0 denotes the month of the turnover, M+1, M+2, M+3, M+4, and M+5 indicate the month thereafter the turnover. Following standard practice, we omit the dummy for M−1 as the reference period. We then interact these event time dummies with the respective turnover indicator variable (i.e., Mayor for model 1 and Partysecrt for model 2), replacing the single treatment indicator in the main regression models. Table 2 presents the regression results of the parallel trend test, and Fig. 1 depicts the coefficients for the estimated event time dummies with their 95% confidence intervals. As indicated in Model 1 of Table 2 and Fig. 1a, the six estimate coefficients for the pre-mayoral turnover periods are statistically insignificant, supporting the parallel trend assumption for the mayoral turnover effects. Model 2 of Table 2 and Fig. 1b reveal no significant difference between the treatment and control groups during the pre-Party secretary turnover periods, validating the parallel trend assumption for the Party secretary turnover effects.

Benchmark model result

Table 3 reports the results of the baseline models examining the impact of mayors and Party secretary turnover on local air quality. Hypothesis 1 proposes that mayoral turnover in Chinese cities has a negative effect on local air quality in the short term. In Model 1, which only includes mayoral turnover, the results show a significant positive effect on PM2.5 concentration at the 0.1% statistical level (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=3.563,\,p \,<\, 0.001\)). When all control variables are introduced in Model 2, the coefficient suggests that mayoral turnover leads to an increase in PM2.5 concentration by approximately 2.207 units, significant at the 0.1% statistical level (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=2.207,\,p \,<\, 0.001\)). Clearly, these empirical results strongly support Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 argues that the Party secretary turnover in Chinese cities has a negative impact on local air quality improvement in the short term. However, the results do not support this hypothesis. Model 3, including only Party secretary turnover, shows no statistically significant influence on local air quality (\({\beta }_{{\rm{Partysecrt}}}=0.990,\,p \,>\, 0.10\)). Similarly, in Model 4, which includes all control variables, the coefficient for Party secretary turnover indicates a positive but statistically insignificant effect on PM2.5 concentration (\({\beta }_{{\rm{Partysecrt}}}=0.677,\,p \,>\, 0.10\)). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 fails to receive empirical support. One possible explanation for these results is that mayors, who are directly responsible for environmental regulatory decisions, have a more immediate and tangible impact on air quality. In contrast, Party secretaries play a more indirect role, primarily influencing overall local governance and policy direction rather than directly administering environmental regulations.

For the control variables, the DiD regressions show consistent and interpretable results. First, weather factors like wind (Wind), temperature (Temp), and precipitation (Rain) have negative impacts on PM2.5 concentration at the 0.1% statistical level. Second, the results reveal that GDP per capita (Pgdp) shows a significant negative effect on PM2.5 concentration at the 0.1% statistical level, which is consistent with explanations from the environmental Kuznets curve theory. To be specific, as local leading industrial sectors become cleaner, environmental pollution decreases as economic wealth grows (Grossman and Krueger, 1993), which is reflected in the GDP per capita. Third, population density (Density) also reports a negative effect on PM2.5 concentration at the 1% level, possibly attributed to the relocation of polluting industries from urban centers to peripheral areas. Lastly, both the number of employees in the secondary industry (Employee) and the number of industrial enterprises (Firmscale) display positive effects on local PM2.5 concentration.

Robustness test

Placebo test

To ensure that our findings remain unaffected by unobserved factors, we perform a placebo test following established procedures (Chetty et al., 2009; Eggers et al., 2024). To be specific, we conduct additional difference-in-differences (DiD) estimations by artificially assigning pseudo-political official turnover events to cities. If no systematic differences in PM2.5 concentrations emerge between the pseudo-treat and control groups during these placebo events, it suggests that unobserved confounders are unlikely to bias our baseline estimates (Eggers et al., 2024; Li et al., 2016). Following the approach of Li et al.’s (2016), we conduct 5000 randomized DiD regressions, randomly assigning both the timing of the turnover event and the treated cities in each replication. Figure 2 displays the kernel density distribution of the DiD estimates from these 5000 replications. The estimated coefficients, which range from −1 to 1 and are centered around 0, suggest that no systematic unobserved effects are associated with the placebo treatment assignments. This result confirms that our findings are robust to potential endogeneity arising from omitted variable bias.

EBM-DiD regression

To further address potential endogeneity arising from selection bias due to covariate imbalances, we employ Hainmueller’s (2012) Entropy Balancing Method (EBM). This approach reweights the observations in the treatment and control groups to achieve covariate balance, thereby reducing bias from observable differences. Once balance is achieved, we re-estimate our DiD models. As reported in Table 4, the results remain robust. Model 1 and 2 indicate that the coefficient for Mayor remains significant at 0.1% statistical level (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=2.518,{P} \,<\, 0.001\)), reaffirming that mayoral turnover exacerbates local air pollution. Conversely, Model 3 and 4 demonstrate that the effect of Party secretary turnover on local air quality remains statistically insignificant (\({\beta }_{{Partysecrt}}=0.49,{P} \,>\, 0.10\)). The EBM-DiD results demonstrate that our baseline estimates are not driven by covariate imbalances, thereby mitigating endogeneity concerns stemming from selection bias on observed confounders.

Alternative measure of local air quality

To ensure the generalizability and reliability of our benchmark findings, we conduct robustness checks using alternative measurements of air quality. By re-estimating our models with alternative dependent variables, we address concerns about whether the observed relationship between political turnover and air quality is sensitive to the choice of pollutant indicators. In Table 5, we replace the original dependent variable, PM2.5 concentration, with two other nationally recognized pollutants: PM10 and SO2. These pollutants are selected based on their status as nationally recognized indicators, featuring prominently in China’s National Air Quality Report published by China National Environmental Monitoring Center (https://www.cnemc.cn/jcbg/). PM10 is an inhalable coarse particulate with a larger diameter than PM2.5 and is widely recognized by the World Health Organization as a substantial health hazard. SO2 concentration, another critical measure of air pollution, originates primarily from the fuel combustion and industrial emissions. As shown in Table 5, the coefficient for the effect of mayoral turnover on local PM10 concentration is positive and statistically significant at 1% level (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=2.982,{p} \,<\, 0.01\), Model 1), similarly for the impact of mayor turnover on SO2 concentration (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=2.150,{p} \,<\, 0.01\), Model 2). Conversely, Party secretary turnover shows insignificant influence on either PM10 (\({\beta }_{{Partysecrt}}=-0.203,{p} \,>\, 0.10\), Model 3) or SO2 concentration (\({\beta }_{{Partysert}}=0.477,{p} \,>\, 0.10\), Model 4). In summary, these results align with the findings from the baseline regression (i.e., Table 3), further validating that our conclusions are not limited to a specific air quality measure, but rather are robust across a range of relevant pollutants.

Excluding extreme values of the dependent variable

To further validate the reliability of our findings, we conduct an additional robustness check by excluding extreme values of the dependent variable, thereby minimizing the potential undue impact of outliers on the results. Specifically, we define the extreme values as those at the 5th percentile and 95th percentile of the dependent variable distribution, and get them removed from the analysis. As indicated in Table 6, the results remain consistent with those of the baseline regressions, even after excluding outliers. The stability of these results across trimmed and untrimmed samples suggests that the observed turnover effects are not artifacts of outlier-driven noise but rather reflect robust and consistent patterns.

Heterogeneity analysis

Regional heterogeneity

China’s economic system is characterized by significant regional disparities, which may influence the relationship between local political official turnover and air quality. In light of this, it is essential to explore potential regional heterogeneity in the effects of political turnover on environmental outcomes. To account for these variations, we divide our sample into two groups based on the geographic locations: Eastern and non-Eastern cities (Yu et al., 2019). The regression results are shown in Table 7. As demonstrated, the effects of official turnover on local air quality exhibit variations across regions. Specifically, with respect to mayoral turnover, the effects on pollutant emission in Eastern cities (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=2.406,{P} \,<\, 0.01\), Model 1) is larger than that in non-Eastern cities (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=1.192,{P} \,<\, 0.05\), Model 2), with both coefficients statistically significant. Conversely, Party secretary turnover shows positive effects on PM2.5 concentration in both Eastern cities (\({\beta }_{{\rm{Partysecrt}}}=0.289,{P} \,>\, 0.10\), Model 3) and non-Eastern cities (\({\beta }_{{\rm{Partysecrt}}}=0.422,{P}\,>\, 0.10\), Model 4), but neither effect is statistically significant. These results contrast with the conclusion of Ruan et al. (2020) research, which argued that non-Eastern cities, due to their reliance on resource-intensive industries, would experience stronger environmental policy effects. One possible explanation for our results is that Eastern cities tend to have larger industry scales compared to their non-Eastern counterparts, which makes them more vulnerable to disruptions in policy continuity. Consequently, the policy uncertainty induced by major turnover may have a more pronounced impact in these areas, where industrial activity and environmental effects are more concentrated.

Central environmental protection inspection

To address environmental pollution, the Chinese central government has implemented a series of initiatives, among which the Central Environmental Protection Inspection (CEPI) system stands out as a critical regulatory mechanism. Led by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, CEPI represents a significant effort to strengthen environmental governance and pollution control. The inaugural round of the CEPI commenced in January 2016 and concluded in September 2017 (Liu et al., 2022). Under this framework, the environmental protection inspection teams were empowered with significant enforcement authority, allowing them to directly hold local governments accountable. This has resulted in measurable improvements in air quality within the inspected provinces and municipalities (Li et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). Empirical studies have consistently highlighted CEPI’s role in driving local air quality improvements. For instance, Lin et al. (2021), utilizing data from 291 Chinese cities, demonstrated that CEPI led to significant reductions in the air quality index (AQI) and the concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, and SO2, highlighting its effectiveness in environmental governance. Similarly, Zheng and Na (2020), based on data from 131 cities, revealed that CEPI has a short-term effect in improving local air quality.

Drawing on the above analysis, we argue that the CEPI mitigates the adverse effects of local political turnover on local air quality, primarily through its institutionalized deterrence mechanism. On the one hand, the accountability framework of CEPI—featuring public disclosure of violations and penalties for non-compliance—serves as a powerful incentive for newly appointed mayors to prioritize environmental governance. The system’s centralized oversight and the accountability risks it entails curb local officials’ inaction in environmental governance during periods of political turnover (Li et al., 2022; Lu, 2022). On the other hand, beyond imposing substantial regulatory costs on polluting enterprises, the CEPI system mobilizes widespread public supervision over corporate emissions through its transparent reporting mechanisms. This multi-stakeholder oversight framework, combining regulatory enforcement with societal monitoring, effectively constrains industrial pollutant emissions during the local leadership transitions (Lu, 2022).

It is important to acknowledge potential heterogeneity in the impact of political turnover across cities, as differences in the implementation of CEPI may lead to varying outcomes. To explore this, we divide our sample into two groups, cities with CEPI and cities without CEPI. We then run regression analysis and report the results in Table 8. The findings indicate that mayoral turnover leads to a significant increase in PM2.5 concentrations in cities without CEPI (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=1.268,{P} \,<\, 0.05\)). In contrast, cities with CEPI show an insignificant tendency to increase PM2.5 concentrations (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=1.944,{P} \,>\, 0.10\)). These results suggest that the Central Environmental Protection Inspection may depress the negative effects of mayoral turnover on regional air quality. However, the impact of Party secretary turnover on air quality in cities with CEPI (\({\beta }_{{\rm{Partysecrt}}}=-0.283,{P} \,>\, 0.10\)) and without CEPI (\({\beta }_{{\rm{Partysecrt}}}=2.978,{P} \,>\, 0.10\)) is not statistically significant.

Geographic origins of newly appointed political officials

Previous research has highlighted the significant impact of cross-regional redeployment (relocation) of government officials in China on both local economic development and environmental pollution (Zhou et al., 2019). Generally, the origin of newly appointed local officials can be categorized into two scenarios: those who are promoted from within the same city and those who are redeployed from other cities. When the officials are promoted internally, they are less likely to disrupt the established political-business framework to abruptly introduce new environmental policies, leading to a less pronounced impact on air pollution. In contrast, when officials are transferred from other cities, the temporary absence of environmental oversight and the anticipated policy uncertainty often encourage local enterprises to adopt less compliant behaviors, resulting in increased pollutant emissions (Chen and Gao, 2020). This study tests the different effects of the geographic origin of mayors and Party secretaries, whether external or internal, on air quality. The results, presented in Table 9, demonstrate that turnover involving externally relocated mayors leads to a more pronounced increase in PM2.5 concentrations (\({\beta }_{{DiD}}=2.250,{P} \,<\, 0.01\)) compared to their internally promoted counterparts (\({\beta }_{{DiD}}=1.951,{P} \,<\, 0.05\)), with the results being statistically significant at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively. A possible explanation for this is that externally relocated mayor, who is unfamiliar with local conditions, may introduce a longer adjustment period in policy implementation. During this transition period, enterprises may take advantage of the lack of local regulatory oversight, leading to a temporary increase in pollutant emissions due to insufficient enforcement or policy action. However, the geographic origins of newly appointed Party secretary, internal promotion (\({\beta }_{{Partsecrt}}=0.694,{P} \,>\, 0.10\)) or external relocation (\({\beta }_{{Partysecrt}}=1.815,{P} \,>\, 0.10\)), have a statistically insignificant influence on PM2.5 concentrations.

Tenure length of predecessor officials

Previous research demonstrates that longer tenures of government officials are systematically associated with detrimental environmental outcomes (Yu et al., 2019). Specifically, prolonged tenures of predecessors foster the entrenchment of government-business networks, which strengthens institutional inertia and obstructs the development of adaptive governance frameworks. This entrenched network structure often leads to significant disruptions within the political ecosystem following leadership transitions, thereby heightening policy uncertainty for firms as shifting power dynamics destabilize established regulatory expectations. In this study, we examine this heterogeneity by dividing our sample into two groups based on tenure length: one group for predecessor officials who served for 36 months or less, and another for those who served more than 36 months (Ji et al., 2022). As shown in Table 10, when the predecessor mayor’s tenure is less than or equal to 36 months, turnover has no statistically significant effect on PM2.5 concentration (\({\beta }_{{mayor}}=0.847,{P} \,>\, 0.10\), Model 1). However, when the tenure of the predecessor mayor exceeds 36 months, turnover is associated with a significantly positive impact on pollution levels (\({\beta }_{{mayor}}=2.771,{P} \,<\, 0.001\), Model 2). This finding may be explained by the higher policy uncertainty that arises from the turnover of a long-tenured mayor. Longer tenure often leads to more entrenched government-enterprise collusion, which can impede the new mayor’s ability to implement more effective environmental policies. In contrast, the tenure length of the predecessor Party secretary shows no statistically significant influence on the relationship between Party secretary turnover and local air quality.

Age of the appointed political officials

Age is considered a vital factor influencing an official’s political performance, as it is strongly associated with the probability of being promoted within the political system (Zhang and Gao, 2008). Prior studies have suggested that the age of local officials may also have a substantial negative impact on air pollution, with older officials typically having a more conservative approach to policy changes (Yu et al., 2019). Building on previous findings that Chinese officials over the age of 55 only have limited access to further promotion (Ji et al., 2022), we divide our sample into three age groups: officials aged 50 or younger, those aged between 51 and 55, and officials aged 56 or older. As presented in Table 11, the effect of mayoral turnover on air pollution varies significantly across three age groups. The turnover of younger mayors (under 50) is associated with a significantly positive effect on air pollution (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=1.612,{P} \,<\, 0.001\)). Similarly, the turnover of mayors aged between 51 and 55 also has a positive but weaker significant effect on air pollution (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=1.622,{P} \,<\, 0.05\)). Notably, for mayors aged 56 or older, the estimated turnover effect on air pollution, while larger in magnitude, is not statistically significant (\({\beta }_{{Mayor}}=3.220,{P} \,>\, 0.10\)). This pattern may be attributed to differing promotion incentives. Younger officials, who are still focused on career advancement and motivated by promotion prospects, are more likely to prioritize short-term economic gains over long-term environmental protection. In contrast, older officials with limited promotion prospects may have less incentive for such rapid, environmentally detrimental growth. In terms of Party secretaries, studies indicate that environmental performance does not significantly impact their promotion, even for younger ones (Feng et al., 2018; Wu and Cao, 2021). This likely explains why no statistically significant results are found in Table 11 for turnover across all three age groups of Party secretaries.

Conclusion and implications

Existing literature suggests that political factors can significantly impact local air quality improvements in China. However, a notable gap exists in the direct investigation of how changes within the local political system specifically affect air pollution in prefectural-level cities. To fill this gap, this study examines the influence of changes within the local political system—both the government system and the Party system— of Chinese prefecture-level cities on their air quality in these jurisdictions. Our quasi-experimental analysis reveals several key insights.

First, changes within the government system, proxied by mayoral turnover, have a significant short-term impact on local air pollutant emissions. Specifically, mayoral turnover is associated with increased pollutant emissions, reflecting the fact that mayoral turnover is a disruptive factor in ongoing local environmental governance. This effect can be attributed to the policy uncertainty inherent in the turnover period, which causes discontinuity of policy implementation and weakens both regulations and supervision. In this respect, the study complements the theory of policy uncertainty by highlighting the dominant role of mayors in affecting local air quality, with empirical evidence from prefectural-level cities.

Second, changes within the Party system, as indicated by the Party secretary turnover, have a negligible effect on reducing or worsening local air pollution in the short term. This suggests that Party secretary turnover does not significantly influence immediate air quality outcomes. This result may stem from the Party system’s indirect authority over administrative affairs, especially in areas like environmental governance, where policy implementation is crucial. Furthermore, as previous studies (Feng et al., 2018; Wu and Cao, 2021) have shown, there is no robust evidence of a link between environmental performance and the promotion of Party secretaries, potentially reducing their motivation to directly intervene in environmental issues.

Third, the adverse effects of mayoral turnover on local air quality are not uniform across heterogeneous cities. These negative effects are more pronounced in eastern Chinese cities, those with newly appointed mayors from outside the jurisdiction, those with longer-serving previous mayors, those with younger newly appointed mayors, and those not subject to central environmental protection inspections. These variations suggest that the influence of mayoral turnover is contingent on geographical, political, and official-specific factors.

In conclusion, our findings reveal that changes within the government system exert a more substantial influence on air quality improvement than those within the Party system in Chinese prefectural-level cities. Specifically, mayoral turnover has a statistically significant short-term negative impact on local air quality, underscoring the pivotal role mayors play in air pollution control. In contrast, Party secretary turnover shows no statistically significant effect.

These findings have important implications for environmental governance in China. First, mayors play a critical role in local air pollution control efforts, as mayoral turnover has a direct impact on pollutant emissions. This highlights the importance of both empowering mayors with sufficient authority and ensuring effective regulatory oversight to support the implement and continuity of environmental policies. Greater emphasis should be placed on holding mayors accountable for environmental outcomes, particularly in the period surrounding turnover events.

Second, ensuring policy stability and continuity in local environmental governance is essential. Given that mayoral turnover negatively affects short-term air quality, maintaining stable leadership and consistent environmental policies is likely to produce more favorable long-term environmental outcomes. Policymakers should consider providing transitional support for newly appointed officials to ensure the continuity of ongoing environmental initiatives. Moreover, environmental performance should be explicitly integrated into the promotion criteria for both mayors and Party secretaries, serving as a key lever to foster long-term, sustainable development.

Third, short-term disruptions resulting from political turnover can impede progress in air quality improvements, highlighting the need to strengthen long-term environmental governance mechanisms. These mechanisms, including well-established and strictly implemented environmental laws and regulations, are essential to prevent the formation of an environmental-political business cycle, where pollution levels fluctuate with political changes. Developing comprehensive environmental plans with clear targets and milestones that span multiple administrations can ensure consistency and continuity of environmental governance, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of policy uncertainty on environmental outcomes.

Finally, vertical supervision mechanisms, such as the Central Environmental Protection Inspection (CEPI), play a critical role in mitigating the negative influence of mayoral turnover. During periods of potential disruption in environmental policies and enforcement due to mayoral turnover, robust vertical supervision provides a stabilizing force by deterring deviations from environmental commitments and incentivizing local officials to maintain or improve environmental performance despite leadership transitions.

Data availability

All data in this study are obtained from authoritative public repositories and government-maintained platforms, and the specific sources have been described in detail in the Data collection section. The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ (2016) Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q J Econ 131(4):1593–1636. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw024

Bonaime A, Gulen H, Ion M (2018) Does policy uncertainty affect mergers and acquisitions? J Financ Econ 129(3):531–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.05.007

Cai Y (2008) Power structure and regime resilience: contentious politics in China. Br J Political Sci 38(3):411–432. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000215

Cao X, Kostka G, Xu X (2019) Environmental political business cycles: the case of PM2.5 air pollution in Chinese prefectures. Environ Sci Policy 93:92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.12.006

Chen L, Gao M (2020) The effects of three types of China’s official turnover on air quality: a regression discontinuity study. Growth Change 51(3):1081–1101. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12406

Chen K, Nie H, Ge Z (2018) Policy uncertainty and FDI: evidence from national elections. J Int Trade Econ Dev 28(4):419–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2018.1545860

Cheng D, Shi X, Yu J (2021) The impact of green energy infrastructure on firm productivity: evidence from the Three Gorges Project in China. Int Rev Econ Financ 71:385–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2020.09.022

Chetty R, Looney A, Kroft K (2009) Salience and taxation: theory and evidence. Am Econ Rev 99(4):1145–1177. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.4.1145

Cole MA, Elliott RJR, Shimamoto K (2005) Industrial characteristics, environmental regulations and air pollution: an analysis of the UK manufacturing sector. J Environ Econ Manag 50(1):121–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2004.08.001

Deng Y, Wu Y, Xu H (2019) Political turnover and firm pollution discharges: An empirical study. China Econ Rev 58:101363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2019.101363

Eaton S, Kostka G (2014) Authoritarian environmentalism undermined? Local leaders’ time horizons and environmental policy implementation in China. China Q 218:359–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741014000356

Eggers AC, Tunon G, Dafoe A (2024) Placebo tests for causal inference. Am J Polit Sci 68(3):1106–1121. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12818

Feng G, Dong M, Wen J, Chang C (2018) The impacts of environmental governance on political turnover of municipal party secretary in China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:24668–24681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-2499-8

Fu S, Gu Y (2017) Highway toll and air pollution: evidence from Chinese cities. J Environ Econ Manag 83:32–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2016.11.007

Grossman G, Krueger A (1993) Environmental impacts of the North American Free Trade Agreement. In: Garber P (ed.) The U.S.-Mexico Free Trade Agreement, MIT Press, Cambridge, pp. 13–56

Guo F, Shi Q (2017) Official turnover, collusion deterrent and temporary improvement of air quality. Econ Res J 52(7):155–168. (in Chinese)

Hainmueller J (2012) Entropy balancing for causal effects: a multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Anal 20(1):25–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr025

Handley K, Nuno L (2017) Policy uncertainty, trade, and welfare: theory and evidence for China and the United States. Am Econ Rev 107(9):2731–2783. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141419

He L, Chen N (2022) Turnover of local government officials and local air quality. China World Econ 30(4):100–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12429

Huang J, Wang Z, Jiang Z, Zhong Q (2023) Environmental policy uncertainty and corporate green innovation: evidence from China. Eur J Innov Manag 26(6):1675–1696. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-12-2021-0591

Ivanova K (2011) Corruption and air pollution in Europe. Oxf Econ Pap 63(1):49–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpq017

Ji X, Liu S, Lang J (2022) Assessing the impact of officials’ turnover on urban economic efficiency: from the perspective of political promotion incentive and power rent-seeking incentive. Socio-Econ Plan Sci 82:101264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2022.101264

Julio B, Yook Y (2012) Political uncertainty and corporate investment cycles. J Financ 67(1):45–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01707.x

Li H, Zhou L (2005) Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China. J Public Econ 89:1743–1762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009

Li K, Fang L, He L (2019) How population and energy price affect China’s environmental pollution? Energy Policy 129:386–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.02.020

Li K, Yuan W, Lin B (2022) Does the environmental inspection system really reduce pollution in China? Data on air quality in China. J Clean Prod 377:134333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134333

Li P, Lu Y, Wang J (2016) Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J Dev Econ 123:18–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.07.002

Lin J, Long C, Yi C (2021) Has central environmental protection inspection improved air quality? Evidence from 291 Chinese cities. Environ Impact Assess Rev 90:106621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106621

Liu Q, Wang Z, Lu J, Li Z, Martinez L, Tao B, Wang C, Zhu L, Lu W, Zhu B, Pei X, Mao X (2023) Effects of short-term PM2.5 exposure on blood lipids among 197,957 people in eastern China. Sci Rep. 13:4505. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31513-y

Liu X, Zhong S, Li S, Yang M (2022) Evaluating the impact of central environmental protection inspection on air pollution: an empirical research in China. Process Saf Environ Prot 160:563–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2022.02.048

Lu J (2022) Can the central environmental protection inspection reduce transboundary pollution? Evidence from river water quality data in China. J Clean Prod 332:130030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130030

Man G (2016) Competition and growth in global perspective: evidence from panel data. J Appl Econ 19(2):363–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1514-0326(16)30015-0

Mardones C, Cornejo N (2020) Ex-post evaluation of environmental decontamination plans on air quality in Chilean cities. J Environ Manag 256:109929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109929

Nguyen NH, Phan HV (2018) Policy uncertainty and mergers and acquisitions. J Financ Quant Anal 52(2):613–644. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109017000175

Pástor L, Veronesi P (2013) Political uncertainty and risk premia. J Financ Econ 110(3):520–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.08.007

Rahman MF, Alam K (2021) Clean energy, population density, urbanization and environmental pollution nexus: evidence from Bangladesh. Renew Energy 172:1063–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.03.103

Ruan F, Yan L, Wang D (2020) The complexity for the resource-based cities in China on creating sustainable development. Cities 97:102571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102571

Shahbaz M, Ozturk I, Afza T, Ali A (2013) Revisiting the environmental Kuznets curve in a global economy. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 25:494–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.05.021

Shao W, Chou L (2023) Political influence and air pollution: evidence from Chinese cities. Heliyon 9(7):E17781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17781

Song C, Sesmero J, Delgado MS (2021) The effect of uncertain political turnover on air quality: evidence from China. J Clean Prod 303:127048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127048

Stern DI (2004) The rise and fall of the environmental Kuznets curve. World Dev 32(8):1419–1439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.03.004

Su F, Tao R, Xi L, Li M (2012) Local officials’ incentives and China’s economic growth: tournament thesis reexamined and alternative explanatory framework. China World Econ 20(4):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-124X.2012.01292.x

Tang T, Jiang X, Zhu K, Ying Z, Liu W (2024) Effects of the promotion pressure of officials on green low-carbon transition: evidence from 277 cities in China. Energy Econ 129:107159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.107159

Tian Z, Tian Y (2021) Political incentives, Party Congress, and pollution cycle: empirical evidence from China. Environ Dev Econ 26:188–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X2000025X

Wang C, Wu J, Zhang B (2018) Environmental regulation, emissions and productivity: evidence from Chinese COD-emitting manufacturers. J Environ Econ Manag 92:54–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2018.08.004

Wang J, Lin B (2024) The dilemma between economic development and environmental protection: how political leadership turnover influences urban air pollution in China? Environ Dev Sustain 26:23663–23681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03617-y

Wang JSH, Zhu Y, Peng C, You J (2024) Internal migration policies in China: patterns and determinants of the household registration reform policy design in 2014. China Q 258:457–478. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741023001674

Wang S, Zhang R, Wan L, Chen J (2023) Has central government environmental protection interview improved air quality in China? Ecol Econ 206:107750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107750

Wing C, Yozwiak M, Hollingsworth A, Freedman S, Simon K (2024) Designing difference-in-difference studies with staggered treatment adoption: key concepts and practical guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health 45:485–505. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-061022-050825

Wu J, Deng Y, Huang J, Morck R, Yeung B (2014) Incentives and outcomes: China’s environmental policy. Capitalism Soc 9(1):1–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107750

Wu M, Cao X (2021) Greening the career incentive structure for local officials in China: does less pollution increase the chances of promotion for Chinese local leaders? J Environ Econ Manag 107:102440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102440

Wu Q, Lin H (2019) Daily urban air quality index forecasting based on variational mode decomposition, sample entropy and LSTM neural network. Sustain Cities Soc 50:101657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101657

Wu X, Ma J, Gao Y, Li B, Chen X, Song M (2023) Policy uncertainty and air pollution: Evidence from the turnover of local officials in China. Econ Anal Policy 80:532–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102440

Xu C (2011) The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development. J Econ Lit 49(4):1076–1151. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.4.1076

Yin L, Wu C (2022) Promotion incentives and air pollution: from the political promotion tournament to the environment tournament. J Environ Manag 317:115491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115491

Yu Y, Yang X, Li K (2019) Effects of the terms and characteristics of cadres on environmental pollution: evidence from 230 cities in China. J Environ Manag 232:179–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.11.002

Zeng M, Zheng L, Huang Z, Cheng X, Zeng H (2023) Does vertical supervision promote regional green transformation? Evidence from Central Environmental Protection Inspection. J Environ Manag 326:116681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116681

Zhang H, Xiong L, Qiu Y, Zhou D (2017) How have political incentives for local officials reduced the environmental pollution of resource-depleted cities? Energy Procedia 143:873–879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111941

Zhang J, Gao Y (2008) Term limits and rotation of Chinese governors: do they matter to economic growth? J Asia Pac Econ 13(3):274–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860802131284

Zheng L, Na M (2020) A pollution paradox? The political economy of environmental inspection and air pollution in China. Energy Res Soc Sci 70:101773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101773

Zhou B, Li Y, Lu X, Huang S, Xue B (2019) Effects of officials’ cross-regional redeployment on regional environmental quality in China. Environ Manag 64:757–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-019-01216-0

Zhou M, Wang B, Chen Z (2020) Has the anti-corruption campaign decreased air pollution in China? Energy Econ 91:104878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104878

Zhu X, Yang Y (2023) The pollution reduction effect of official turnover: Evidence from China. Sci Total Environ 868:161459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161459

Zuo C (2015) Promoting city leaders: the structure of political incentives in China. China Q 224:955–984. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741015001289

Acknowledgements

The authors received funding for writing and revising the manuscript from the following grants: Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, DUT22RC(3)104; Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China, 24YJCZH417; National Natural Science Foundation of China, 71904022; and Humanities and Social Sciences Planning Fund of Liaoning Province, L23CSH006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RL and CY contributed to the key conception and research design. CY contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing—original draft. RL contributed to conceptualization, validation, project administration, writing-review & editing, and supervision. JZ contributed to material preparation, data collection, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

Not applicable for this research because it does not involve human participants.

Ethical approval

Not applicable for this research because it does not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Not applicable for this research because it does not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, C., Zhang, J. & Li, R. Political official turnover and environmental governance: who is more influential on local air pollution in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05052-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05052-y