Abstract

Household energy use for cooking constitutes a significant portion of energy consumption in Pakistan. The use of unclean fuels releases harmful pollutants, increasing the risk of respiratory infections, which are a leading cause of mortality among children under five worldwide. This study assesses the impact of household fuel use on respiratory infections in children under five in Pakistan. This cross-sectional study utilized data from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey. The population included children less than five years of age. Logistic regression models were applied to assess the relationship between household energy type and respiratory infections, adjusting for confounding factors such as wealth status, maternal tobacco use, place of residence, and maternal education. The findings revealed that children in households using clean energy fuels had lower odds of respiratory infections (odds ratio [OR]: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.60–0.80). Having a separate kitchen was associated with reduced odds (OR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.68–0.94), while children from the wealthiest households were significantly less likely to develop respiratory infections (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.44–0.66). Conversely, maternal tobacco use increased the odds of respiratory infections in children (OR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.34–2.04). Regional differences, urban vs. rural residence, and maternal education also emerged as important determinants. This study highlights the critical public health importance of promoting clean energy sources for cooking, improving kitchen design, discouraging maternal tobacco use, and addressing socioeconomic disparities to reduce respiratory infections among children in Pakistan. Policymakers should prioritize accessible clean energy solutions and targeted health interventions to improve child health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Economic progress has largely resulted from a shift from an agrarian-based economy to an industrialized and knowledge-based economy. Such structural changes influence energy utilization levels and patterns across various sectors. Households represent a crucial component of the economy, consuming energy for daily activities such as cooking, washing, cleaning, and heating. Among these, cooking accounts for the majority of household energy consumption. Households rely on various types of fuel, including wood, charcoal, electricity, coal, animal dung, agricultural crops, grass, and biogas. When these fuels are burned, smoke is released which contains several air pollutants, including particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 10 mm (PM10), and particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 2.5 mm (PM2.5), soot, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide (CO) (World Health Organization WHO, 2006a). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), households that use biomass fuel (BMF) are frequently exposed to peak indoor PM10 levels above the recommended limit of 50 mg/m3 (Smith, 2002; World Health Organization WHO, 2006a, 2006b). High CO emissions from BMF combine with hemoglobin to generate carboxyhemoglobin, which lowers blood hemoglobin levels and causes anemia. Hemoglobin is necessary for transporting oxygen to the body tissues. Homes utilizing BMF can occasionally experience CO levels that are sufficiently high to produce carboxyhemoglobin levels comparable to those of tobacco smokers (Behera et al., 1988; Dary et al., 1981; Tympa-Psirropoulou et al., 2008). Human dependence on customary biomass has been associated with negative ecological and well-being outcomes. Cooking fill (smoke and no smoke delivery) and cooking destination (indoor and open air)-related data reflect different levels of home air contamination. The negative outcomes of air contamination include lower levels of child development, stunting, serious weakness, respiratory infections, early mortality, lost efficiency, and social consequences such as respiratory illnesses, which put a massive expense on the worldwide economy as immediate medical service costs (Goyal and Canning, 2018; Hay et al., 2017).

Cooking with solid fuel has been associated with increased blood pressure (BP) and higher odds of hypertension (Arku et al., 2018). Solid fuels, when burned over an open flame, create harmful pollutants and toxins. In Pakistan, approximately 49% of households rely on solid fuels for cooking a trend mirrored in other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as India, Bangladesh, and Nigeria (Cascio et al., 2007; Janjua et al., 2012; Balakrishnan et al., 2019). Despite global progress toward cleaner energy adoption, Pakistan’s limited access to modern energy sources exacerbates reliance on biomass, contributing to its ranking as the third most polluted country worldwide (IQAir, 2023). This reliance on solid fuels leads to elevated levels of indoor air pollution (IAP), particularly in rural and impoverished areas. Comparative studies indicate that while some nations have made strides in adopting clean energy technologies, Pakistan continues to face significant barriers, including economic constraints and a lack of infrastructure to support cleaner alternatives.

It is estimated that more than three billion individuals are at risk of being exposed to household air pollution (HAP) due to cooking with biomass-based cooking stoves, with 66 percent of those living in Southeast Asia and Africa (Pratiti et al., 2020). Women and children are excessively affected by indoor pollution because women do most of the cooking, and children invest a great deal of energy with their mothers when the mothers are doing so. Children are particularly at risk because their immune and respiratory systems are still developing (Kurata et al., 2020). Owing to several biological and socioeconomic variables, children in poor nations are more vulnerable. First, the majority of underprivileged households in developing nations lack access to contemporary energy sources and are consequently compelled to rely on conventional solid fuels (such as wood, animal dung, and agricultural waste), candles, and kerosene for lighting and cooking, all of which exacerbate HAP (Lam et al., 2012). Unprocessed biomass (wood, creature compost, agrarian squanders, and grasses) and coal have been connected to a few medical issues, yet an enormous amount of the total population continues to use them as their essential well-spring for cooking energy (Pun et al., 2019). HAP from cooking fuel has become a critical cause of respiratory illness and mortality, and continues to be a genuine global medical problem (Fullerton et al., 2008). In developing nations, acute lower respiratory disease (ALRI) is viewed as a significant reason for younger mortality, representing up to 15 percent of overall deaths in this age group (Forum on International Respiratory Societies, 2017). Thirty-three of the ALRI cases were considered to have been brought about by HAP.

Respiratory infections have significant social implications beyond individual health concerns. Frequent respiratory infections among children lead to increased medical expenses for families, particularly those in low-income settings. The costs associated with doctor visits, medications, and hospitalizations can be overwhelming, pushing vulnerable households deeper into poverty (Woolley et al., 2020). Additionally, caregivers, often mothers, must take time off work to care for sick children, reducing family income and perpetuating cycles of financial hardship. At a national level, the economic burden on healthcare systems increases due to the higher prevalence of pollution-induced diseases, leading to resource strain and reduced healthcare accessibility for other illnesses. Studies show that exposure to household air pollution negatively impacts school performance and cognitive development, particularly in early childhood. In areas where severe air pollution leads to widespread illness, entire communities may experience disruptions in education, leading to long-term socioeconomic disparities. Indoor air pollution disproportionately affects women and children, as they spend more time indoors, particularly in homes using traditional cooking fuels. Women, often primary caregivers, bear the burden of managing sick children while also being at risk for their own respiratory illnesses (Rana et al., 2019). The impact of childhood respiratory infections due to indoor air pollution extends to entire communities. High disease prevalence can reduce overall workforce productivity as parents miss work to care for sick children. Increased school dropout rates contribute to lower literacy levels and hinder economic development in affected regions.

The widespread reliance on solid fuels and poor ventilation in Pakistani households significantly amplifies the adverse effects of HAP. Insufficient ventilation traps harmful pollutants indoors, exposing household members to prolonged and concentrated levels of toxins. Traditional methods of using solid fuels (such as wood, straw/shrub/grass, animal dung, charcoal, and coal) are the only options for domestic cooking, and access to commercial and clean energy resources is scarce (Bhutto et al., 2011). This study seeks to investigate the relationship between HAP and respiratory infections among children under five in Pakistan. This study underscores how household energy choices affect respiratory health outcomes for children under five. By distinguishing household fuel types into clean and unclean energy sources, it clarifies the health risks tied to these fuel choices—a topic that has received limited attention in the Pakistani context. By examining the associations between household fuel types, ventilation practices, and pediatric respiratory infections, the research aims to provide evidence-based recommendations to mitigate the health impacts of HAP and inform public health interventions in similar contexts.

Materials and methods

Study design and data source

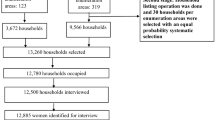

This study employed a cross-sectional design to investigate the determinants of respiratory health infections among children under five years of age in Pakistan, with a specific focus on household energy fuel consumption. The latest available relevant data came from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18, and a new survey has not been conducted yet. So, this study has relied on the 2017–18 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) data. It is a nationally representative survey conducted by the National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) in collaboration with international organizations. The PDHS utilized a two-stage stratified sampling technique to collect data on health indicators, maternal and child health, and environmental factors. These publicly available datasets can be accessed through the NIPS website with prior authorization.

Study variable

Table 1 presents the detailed descriptive statistics for the variables analyzed in the study, highlighting the distribution of characteristics across the surveyed population and the construction of variables. The table shows that approximately 38.15% of children under five years of age experienced a cough in the two weeks preceding the survey, while 61.85% did not. Clean cooking fuels are used by 46.46% of households, whereas 53.54% rely on unclean fuels such as wood and animal dung. A majority of respondents (54.53%) reside in rural areas, while urban areas account for 45.47% of the population. Most households (73.02%) have a separate kitchen, whereas 26.98% do not. Among households, 46.47% use clean fuels, 33.79% use unclean fuels with a separate kitchen, and 19.74% use unclean fuels without a separate kitchen. Additionally, only 6.07% of mothers reported tobacco use, while 93.93% did not. Regarding antenatal care, nearly half (49.45%) of mothers had more than three antenatal visits during pregnancy, 34.51% had up to three visits, and 16.04% had no visits.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the study population. A binary logistic regression model was employed to assess the association between respiratory health conditions in children and the independent variables. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed to evaluate the strength and direction of associations. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13.0. The model included various socioeconomic factors, such as region, place of residence, maternal education level, maternal tobacco use, antenatal care, cooking place, and cooking practices, along with household fuel consumption, to account for potential confounding effects. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical consideration

This study utilized secondary data from the PDHS 2017–18. PDHS data are anonymized to ensure participant confidentiality, and no individual-level identifiers were included in the analysis. The data are publicly available on the National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) website (National Institute of Population Studies Pakistan, Macro International, Institute for Resource Development, Demographic and Health Surveys, 2018).

Results and discussion

Table 2 presents the results of a chi-square test assessing the association between respiratory infections among children under five years of age and various socioeconomic variables. The analysis identifies several significant relationships at different levels of significance. Regional disparities in respiratory health outcomes are evident, as the region variable is significantly associated with respiratory infections (p = 0.0187). Household wealth status exhibits a strong association (p < 0.001), indicating that children from wealthier households are more likely to have better respiratory health conditions. Cooking fuel (p = 0.0056) and place of cooking (p = 0.0016) are also highly significant, underscoring the importance of clean fuel usage and proper cooking environments in reducing respiratory health risks. Additionally, cooking practices, which combine fuel type and kitchen setup, show a significant association with respiratory issues (p = 0.018), emphasizing the compounded effect of these factors. Antenatal care during pregnancy (p = 0.0002) and maternal education level (p < 0.001) highlight the crucial role of maternal healthcare and education in mitigating respiratory health conditions in children. Lastly, maternal tobacco use is a strong predictor (p < 0.001), reflecting the adverse health impacts of tobacco exposure.

After checking the association between respiratory infections and the independent variables, in the next step a regression analysis was performed to check the direction of causality. The results of logistic regression analysis are reported in Table 3.

The first independent variable considered was the type of cooking fuel used by households. According to an odds ratio of 0.667, compared to the base category (use of unclean cooking fuel), children in households using clean cooking fuel are 1.43 times less likely to suffer from respiratory infections. This can be interpreted as: “Compared to households using unclean cooking fuel, the odds of respiratory infections in children from households using clean cooking fuel are 0.667.” Alternatively, this can be converted into how many times it is less likely by dividing 1 by the given odds ratio (1/0.667 = 1.43 times). A similar interpretation is applied when odds ratios are less than 1. This interpretation of the odds ratio has been adopted from (Nadeem et al., 2024). Access to clean cooking fuel is critical to reducing the negative impact of household air pollution on respiratory health. The use of traditional cooking fuels, such as solid biomass (wood, charcoal, crop waste, and dung) and kerosene, results in high levels of indoor air pollution. Exposure to such pollutants is particularly harmful to children’s respiratory health, as their lungs are still developing and they breathe more rapidly than adults. The findings of the current study are consistent with a study in Nigeria, which also found that households using Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) (which is a clean cooking fuel) had significantly lower rates of respiratory symptoms and illnesses than those using solid fuels (Oluwole et al., 2019). Another study conducted in rural India also found that switching from traditional solid fuels to LPG resulted in a 35% reduction in the incidence of acute lower respiratory infections among children under 5 years old (Balakrishnan et al., 2013). Another study found that pregnant women exposed to secondhand smoke at home have a higher likelihood of delivering low birth weight infants (Andriani et al., 2023).

The second variable was the place of cooking. The base category was, “there was no separate kitchen available in the house for cooking”. The odds ratio associated with cooking place, where a separate kitchen is available for cooking, was 0.797, which indicates that if cooking takes place in separate kitchens in the house, then the child of that household is 1.25 times less likely to suffer from respiratory infections. Cooking practices are the next variable that can significantly impact the respiratory health of children. The odds ratio associated with cooking practices (use of clean fuel for cooking in a separate kitchen) was 0.804, which indicates that if households use clean fuel for cooking in a separate kitchen, then the child of such a household is 1.25 times less likely to suffer from respiratory infections. Using cleaner fuels, proper ventilation, and adopting safe cooking practices can help reduce exposure to air pollutants and lower the risk of respiratory symptoms and diseases. In many homes, cooking is performed in the same space in which people spend their time, which can increase the risk of exposure. However, having a separate kitchen where cooking is performed away from the rest of the living space can potentially reduce exposure to cooking-related air pollutants. Similar findings were reached by a study conducted in China, which found that children living in homes with separate kitchens had a lower prevalence of respiratory symptoms such as coughing and wheezing than those living in homes without separate kitchens (Chen et al., 2014). Another study conducted in the United States found that children living in homes with gas stoves and no-range hoods, which can contribute to higher levels of cooking-related air pollutants, had a higher risk of asthma if they did not have a separate kitchen (Belanger et al., 2014). The use of solid fuels like wood and charcoal, coupled with cooking indoors without proper ventilation, significantly increases the risk of respiratory and other health issues among household members, especially women and children (Ahamad et al., 2021).

Antenatal care is another important determinant of child health. The base category has been antenatal care received. The odds ratio associated with antenatal care not received was 1.08. This finding indicates that if antenatal care is not sought by the mother during pregnancy, the child is slightly more prone to respiratory infections. Antenatal care can provide opportunities for health education and counseling on topics such as breastfeeding, nutrition, and maternal smoking cessation, which can reduce the risk of respiratory problems in children. A study conducted in India found that antenatal care is associated with a reduced risk of childhood respiratory infections. Children born to mothers who received adequate antenatal care had a lower incidence of respiratory infections than did those whose mothers did not receive antenatal care (Thakur et al., 2016).

Mothers’ tobacco use was another important variable. The base category used for this variable was that the mother of the child did not use tobacco. The odds ratio associated with the mother’s tobacco use was 1.656, which indicates that if the mother of the child smoked tobacco, the child was 1.656 times more likely to suffer from respiratory infections. Maternal tobacco use during pregnancy and the postpartum period is associated with respiratory issues in children. Nicotine and other harmful chemicals in tobacco can cross the placenta and affect fetal lung development, leading to a higher risk of respiratory problems in children. Findings of this study are consistent with a study conducted in Iran, which found that children born to mothers who smoked during pregnancy were more likely to develop respiratory problems, such as wheezing and asthma, than children born to non-smoking mothers (Hosseini et al., 2018).

Geographical region is also an indicator; each province of the country has been taken as a region. The base category was Sindh Province. The odds ratio associated with Punjab province is 1.321, which indicates that compared to Sindh province, children in Punjab province are 1.321 times more likely to suffer from respiratory infections. The odds ratio associated with KPK province was 1.249, which indicates that children in KPK are 1.249 times more likely to suffer from respiratory infections. The odds ratio associated with Baluchistan province was 0.92, indicating that the children in Baluchistan province were 1.086 times less likely to suffer from respiratory infections. The odds ratio associated with ICT was 1.253, indicating that children of ICT are 1.253 times more likely to suffer from respiratory infections. Geographical regions have also been found to be strong predictors; they are higher in Punjab, KPK, and Sindh and lower in Baluchistan. This may be because the houses have smaller areas in Punjab, KPK, and ICT, and small areas, there will be dense smoke, and the smoke of the cooking fuel can be more dangerous to the respiratory system of children. In Baluchistan, the area of the houses may be larger, due to which smoke may disperse in the air, and it may be less dense and less dangerous for the respiratory system of the children.

Place of residence can also be an important factor in determining the child's health. In the current study, the place of residence has been divided into rural and urban areas, and the base category was the urban area; the odds ratio associated with the rural area was 0.779, which indicates that the children of the rural area are 1.28 times less likely to suffer from respiratory infections. Respiratory problems were found to be lower in rural areas. This may be due to the fact that in rural areas, the houses are not as congested and a lot of open spaces are available in the houses, so smoke can disperse and is less injurious to the health of the young ones as compared to urban areas. Children living in urban areas are more likely to suffer from respiratory problems than those living in rural areas because of their increased exposure to air pollution and other environmental factors. A study conducted in India found that children living in urban areas were more likely to suffer from respiratory problems such as wheezing and coughing than those living in rural areas (Padhi et al., 2020). Overcrowding, poor housing conditions and a lack of access to basic amenities such as clean water and sanitation are more common in urban areas and have also been found to be associated with respiratory problems among children (Osimani et al., 2020).

A mother’s educational level can play a very important role; the base category is that the mother has no education. The odds ratio associated with the primary level of the mother’s education was 1.282, which indicates that the child of a mother with a primary level of education is 1.28 times more likely to suffer from respiratory infections. However, the value of the odds ratio decreases as the level of mother's education increases This indicates that the respiratory issue of the children is less likely for the children of more educated mothers which may be due to the reason that a more educated mother is more likely to adopt various precautionary measures to avoid the children being exposed to smoke. Mothers with higher education levels are more likely to have better knowledge and awareness of health-related issues, including respiratory problems, and are more likely to adopt healthier behaviors for their children. Our findings are consistent with a study conducted in Bangladesh, which found that the children of mothers with higher education levels were less likely to suffer from respiratory problems than those of mothers with lower education levels (Tiwari et al., 2020). Similarly, a study in Nigeria also found that maternal education level was a significant predictor of respiratory problems among children, with children of mothers with higher education levels being less likely to suffer from respiratory problems (Ojo et al., 2020).

Household wealth status has the poorest households as the base category. The odds ratio associated with poorer households is 0.943, indicating that, compared to the poorest households, the children of poorer households are less likely to suffer from respiratory infections. The odds ratio value decreases as the household moves to the next level of wealth status. The odds ratio for the richest households is 0.541, which indicates that the children of the richest households are 1.84 times less likely to suffer from respiratory infections. This may be because the richest households are more likely to use clean cooking fuel, and they are also more likely to have separate kitchens in the house. Therefore, the children of such households may be less likely to suffer from respiratory issues. Children from households with lower wealth status are more likely to suffer from respiratory problems than those from wealthier households. This is because households with a lower wealth status are more likely to be exposed to environmental hazards, such as indoor air pollution, inadequate ventilation, and poor housing conditions. This is consistent with a study conducted in India, which found that children from poorer households were more likely to suffer from respiratory problems than those from wealthier households (Sreeramareddy et al., 2015). Similarly, a study in Ethiopia also found that household wealth status was a significant predictor of respiratory problems among children, with those from poorer households being more likely to suffer from respiratory infections (Getachew et al., 2018).

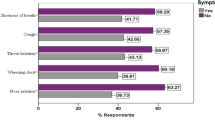

The results of logistic regression are summarized in Fig. 1, which is a bar chart of odds ratios of key independent variables affecting respiratory infections in children. Variables with odds ratios less than 1 (green bars) indicate protective effects, while those greater than 1 (red bars) indicate increased risk. It shows that children of households that use clean cooking fuel, households having a separate kitchen, residing in rural areas, being residents of Baluchistan and belonging to well-off wealth status are less likely to be affected by respiratory health infections. In addition, it is evident from Fig. 1 that the children whose mother has no antenatal care, the mothers smoke tobacco and a low level of the mother’s education are more likely to be affected by respiratory infections.

Conclusion

Households are the basic unit of any economy, utilizing fuel for various domestic activities. The majority of household energy consumption is centered on cooking, with different types of fuels classified based on their impact on health and the environment. Clean cooking fuels include electricity, LPG, natural gas, and biogas, while unclean fuels comprise coal, charcoal, wood, straw, plants, grass, crops, and animal waste. The combustion of unclean fuels releases smoke containing harmful air pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, PM10, and PM2.5. These pollutants have severe adverse effects, including impaired child development, frailty, early mortality, reduced productivity, and respiratory ailments. Reducing health risks associated with household air pollution (HAP) and ambient air pollution (AAP) is crucial for achieving sustainable global development, particularly in low-income countries. Children are especially vulnerable to the negative effects of household air pollution, with respiratory issues being among the leading causes of mortality for children under five worldwide. This study investigated this issue using demographic and health survey data from Pakistan. The analysis was conducted through theoretical reasoning, association tests, and logistic regressions. Various socioeconomic factors were incorporated to control for confounding variables affecting respiratory infections. The results of the study revealed that the children of households that did not use clean energy fuels were more likely to suffer from respiratory infections. Besides cooking fuel, the place of cooking, cooking practices, mother’s tobacco use, region, place of residence, and household wealth status are also important determinants of respiratory infections among children. There is a need to adopt clean cooking fuel use practices, cook in a place which is away from the reach of children, mothers should avoid tobacco use, and there is a need to enhance the earning potential of the poor households so that children may be saved from respiratory infections. Furthermore, it is suggested that better cooking ovens, which can mitigate smoke emission, be created, advanced, and financed for poor families. Pakistan has several national programs that can integrate these findings into policy and practice. Firstly, clean energy adoption plays a crucial role in reducing respiratory infections in children. The Pakistan Clean Air Program can expand efforts to target indoor air pollution by subsidizing clean cooking fuels and low-emission stoves for low-income households. Secondly, household wealth significantly affects child respiratory health. The Benazir Income Support Program (BISP)/Ehsaas Program can help by linking cash transfers to clean energy adoption, providing financial support for cleaner stoves, and promoting mothers’ economic empowerment to reduce reliance on polluting fuels. Thirdly, maternal tobacco use is a major risk factor. The Lady Health Worker (LHW) and Maternal, Newborn & Child Health (MNCH) Programs can be strengthened by training LHWs to support mothers in quitting tobacco, educating families on secondhand smoke risks, and incorporating indoor air quality assessments into health visits. Lastly, regional disparities in respiratory infections highlight the need to integrate indoor air quality into climate change and regional development policies.

Limitations of the study

The latest relevant data came from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18, and a new survey has not been conducted yet. So, relying on the 2017–18 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) data might not fully represent the current situation.

Despite the data limitation of using PDHS 2017–18, the study’s findings remain highly relevant today because the core risk factors for childhood respiratory infections—such as energy use, housing conditions, socioeconomic status, tobacco exposure, and regional disparities—have not changed significantly.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are publicly available at https://www.nips.org.pk/ and from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Ahamad MG, Tanin F, Shrestha N (2021) Household smoke-exposure risks associated with cooking fuels and cooking places in Tanzania: a cross-sectional analysis of demographic and health survey data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(5):2534

Andriani H, Rahmawati ND, Ahsan A, Kusuma D (2023) Secondhand smoke exposure inside the house and low birth weight in Indonesia: Evidence from a demographic and health survey. Popul Med 5(June):1–7

Arku RE, Ezzati M, Baumgartner J, Fink G, Zhou B, Hystad P, Brauer M (2018) Elevated blood pressure and household solid fuel use in premenopausal women: analysis of 12 demographic and health surveys (DHS) from 10 countries. Environ Res 160:499–505

Balakrishnan K et al. (2019) Exposure to household air pollution and its effects on health in LMICs. Annu Rev Public Health 40:47–66

Balakrishnan K, Ghosh S, Ganguli B, Sambandam S, Bruce N, Barnes DF, Smith KR (2013) State and national household concentrations of PM2. Five from solid cookfuel use: results from measurements and modeling in India for estimation of the global burden of disease. Environ Health 12(1):1–14

Behera D, Dash S, Malik SK (1988) Blood carboxy hemoglobin levels following acute exposure to biomass fuel smoke. Indian J Med Res 88:522–524

Belanger K, Gent JF, Triche EW, Bracken MB, Leaderer BP (2014) Association between indoor nitrogen dioxide exposure and respiratory symptoms in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190(11):1168–1175

Bhutto AW, Bazmi AA, Zahedi G (2011) Greener energy: issues and challenges for Pakistan, Biomass Energy Prospective. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 15(6):3207–3219

Cascio WE, Cozzi E, Hazarika S, Devlin RB, Henriksen RA, Lust RM, Wingard CJ (2007) Cardiac and vascular changes in mice after exposure to ultrafine particulate matter. Inhalation Toxicol 19(sup1):67–73

Chen C, Zhao B, Weschler LB, Wang S, Zhang Y, Zhang JJ, Sundell J (2014) Indoor air quality, ventilation, and respiratory health in children: a literature review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 21(9):5762–5776

Dary O, Pineda O, Belizán JM (1981) Carbon monoxide contamination in dwellings in poor rural areas of Guatemala. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 26(1):24–30

Forum on International Respiratory Societies (2017) The global impact of respiratory disease. European Respiratory Society

Fullerton DG, Bruce N, Gordon SB (2008) Indoor air pollution from biomass-fuel smoke is a major health concern in developing countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102(9):843–851

Getachew A, Ricciuto LE, Sia D, Taddesse HB, Kirolos A (2018) Household wealth status and respiratory problems among Ethiopian children. PLoS ONE 13(11):e0206870

Goyal N, Canning D (2018) Exposure to ambient fine particulate air pollution in utero is a risk factor of stunting in children. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(1):22

Hay SI, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Ciobanu LG (2017) Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries, and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390(10100):1260–1344

Hosseini M, Sarrafzadeh F, Tolide-ei HR, Movahedi M (2018) Maternal smoking during pregnancy and respiratory problems in the offspring. J Res Med Sci 23(1):3

IQAir (2023) World air quality report. Retrieved from IQAir website

Janjua NZ, Mahmood B, Dharma VK, Sathiakumar N, Khan MI (2012) Use of biomass fuel and acute respiratory infections in rural Pakistan. Public Health 126(10):855–862

Kurata M, Takahashi K, Hibiki A (2020) Gender differences in the associations of household and ambient air pollution with child health: Evidence from household and satellite-based data in Bangladesh. World Dev 128:104779

Lam NL, Smith KR, Gauthier A, Bates MN (2012) Kerosene: a review of household use and its hazards in low-and middle-income countries. J Toxicol Environ Health, Part B 15(6):396–432

Nadeem M, Anwar M, Adil S, Syed W, Al-Rawi MBA, Iqbal A (2024) The association between water, sanitation, hygiene, and child underweight in Punjab, Pakistan: an application of population attributable fraction. J Multidiscip Healthcare 17:2475–2487

National Institute of Population Studies (Pakistan), Macro International. Institute for Resource Development, Demographic and Health Surveys (2018) Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey. National Institute of Population Studies

Ojo OA, Ojo AO, Adeniyi OV, Agunbiade OM (2020) Maternal sociodemographic determinants of childhood respiratory diseases in a tertiary health facility in southwestern Nigeria. Afr J Respir Med 16(1):1–8

Oluwole O, Arinola GO, Huo D, Olopade CO, Olopade OI (2019) Clean cookstove intervention improves lung function and reduces airway inflammation in rural Nigerian women: a randomized controlled trial. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 181:494–500

Osimani CK, Hennessy-Burt TE, Rodriguez-Llanes JM (2020) Children’s respiratory health and air pollution in Latin America: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(12):4568

Padhi BK, Mishra OP, Panigrahi S (2020) Prevalence and risk factors for respiratory problems among rural and urban schoolchildren in Odisha, India. J Fam Med Prim Care 9(3):1393–1397

Pratiti R, Vadala D, Kalynych Z, Sud P (2020) Health effects of household air pollution related to biomass cooking stoves in resource-limited countries and its mitigation by improved cooking stoves. Environ Res 186:109574

Pun V, Mehta S, Dowling R (2019) Air pollution and child stunting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Epidemiol 3:318

Rana J, Uddin J, Peltier R, Oulhote Y (2019) Associations between indoor air pollution and acute respiratory infections among under-five children in Afghanistan: do SES and sex matter? Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(16):2910

Smith KR (2002) Indoor air pollution in developing countries: recommendations for research. Indoor Air 12(3):198–207

Sreeramareddy CT, Shidhaye RR, Sathiakumar N (2015) Association between household wealth inequality and chronic childhood undernutrition in Bangladesh. Int J Equity Health 14(1):100

Thakur N, Sharma R, Jaswal N (2016) Impact of antenatal care on perinatal and postnatal outcomes in an urban slum in Northern India. J Clin Diagn Res 10(3):LC10–LC14

Tiwari S, Rahman M, Hossain MA, Akter S (2020) Household wealth and healthcare utilization for childhood morbidity in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 39(1):1–13

Tympa-Psirropoulou E, Vagenas C, Dafni O, Matala A, Skopouli F (2008) Environmental risk factors for iron-deficiency anemia in children aged 12–24 months in Thessalia, Greece. Hippokratia 12(4):240

Woolley KE, Bagambe T, Singh A, Avis WR, Kabera T, Weldetinsae A, Bartington SE (2020) Investigating the association between wood and charcoal domestic cooking, respiratory symptoms and acute respiratory infections among children aged under 5 years in Uganda: a cross-sectional analysis of the 2016 demographic and health survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(11):3974

World Health Organization (WHO) (2006a) WHO. Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. Global update 2005. World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/786, 38, E90038

World Health Organization (WHO) (2006b) Air quality guidelines: global update 2005: particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. World Health Organization (WHO)

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-1099), King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia for their encouragement and assistance. This work was funded by the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-1099), King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed equally.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not needed as the authors used secondary data that were publicly available; furthermore, this study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not needed as the authors used secondary data that were publicly available.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nadeem, M., Anwar, M., Ul Rehman, W. et al. Household fuel consumption, indoor air pollution, and respiratory health infections among children in Pakistan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1323 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05070-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05070-w