Abstract

Unfocused corrective feedback is pivotal in second language (L2) writing instruction, yet its differential impacts on various linguistic elements remain underexplored in existing literature. The present study investigated the effectiveness of unfocused corrective feedback versus no corrective feedback in enhancing English article, prepositional, and verb tense accuracy among L2 student writers. Conducted over an 18-week period with 57 participants, the research employed a pretest-posttest-delayed posttest design to evaluate the impacts of these feedback types on linguistic accuracy. Participants were divided into two groups: a group that received only content feedback, and an experimental group that received both content feedback and unfocused corrective feedback. The findings indicate that unfocused corrective feedback effectively improved the accuracy of English articles, with notable gains observed in the delayed posttests. However, the effects on prepositional and verb tense accuracy were less pronounced, suggesting that more targeted feedback strategies may be necessary for these error types. The results highlight the utility of unfocused corrective feedback in writing instruction, emphasizing its role in enhancing grammatical accuracy, particularly in articles. This underscores the need for incorporating diverse feedback mechanisms to address varied linguistic challenges in L2 writing contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Receipt of feedback is necessary for second language (L2) writing development (Lee 2023; Liu and Brown 2015). Most L2 writing researchers and teachers would not have a problem agreeing with this statement. This is because there is a large body of research that supports varying levels of L2 writing improvement for writers that are provided with feedback (Peng 2024; Rastgou 2022; Reynolds 2023; Zhang and Hyland 2018). However, agreement gets more complicated and nuanced when discussing the type or provider of the feedback in question. Qualitative-oriented researchers have attempted to understand the complex working mechanism of feedback reception and uptake through a close examination of the mediating role of multitudinous factors (Gao and Wang 2022; Lee and Evans 2019; Kong and Teng 2023). Such a route has the potential of pushing the boundaries of theory for the complex learning that occurs in complex social systems surrounding the teaching and learning of L2 writing. Going such a route, therefore, may inadvertently take the product of these processes—L2 writing—out of the limelight. By contrast, quantitative-oriented researchers have attempted to understand the complex working mechanism of feedback reception and uptake through a long series of discrete quasi-experimental studies aimed at providing incremental knowledge on feedback effectiveness. While more tightly controlled, quasi-experimental studies run the risk of oversimplifying the feedback process and corresponding effects on L2 writing. It is at this juncture where the current study resides. This study, hence, conducted an experiment for an 18-week period by employing a pretest-posttest-delayed posttest design to longitudinally keep track of student writers’ acquisition of specific linguistic features through corrective feedback.

The scope of feedback that encompasses both focused and unfocused feedback has garnered increased attention in recent studies (e.g., Lee et al. 2021; Mao and Lee 2020; Rahimi 2019). The distinction between focused and unfocused feedback primarily hinges on the quantity of error types corrected. Unfocused feedback is typically provided to correct all or the majority of students’ linguistic errors (Ellis 2009). Conversely, focused feedback is generally offered to target a particular error type for correction (i.e. Bitchener 2008; Ellis et al. 2008; Sheen 2007).

Previous research has shown that L2 writing teachers’ written corrective feedback can have a significant effect on the grammatical accuracy of subsequent drafts produced by L2 writers (Brown 2012; Gao and Wang 2022; Lee 2019). To be exact, most of these studies has dealt with the correction of a single or a set of focused error types and showed a more robust effect for focused written corrective feedback provided by teachers in comparison to unfocused written corrective feedback (Deng et al. 2022; Sheen 2007; Sheen et al. 2009). However, most of these studies have ignored two critical issues. The first issue is that many of these quasi-experimental studies have been situated in research contexts that are not congruent with common classroom practices. Because student writers normally produce more than one error type in a single piece of writing, focused corrective feedback might not be pedagogically practical in second language writing classrooms. The second issue concerns the potential bandwagon effect present in the methodologies used by written corrective feedback researchers. In other words, it has been widely suggested that unfocused corrective feedback should be harmful to students’ written accuracy; additionally, it decreases writing fluency, increases anxiety, and lowers confidence (Lalande 1982; Robb et al. 1986; Truscott 2023; Truscott and Hsu 2008). These criticisms have relegated unfocused corrective feedback to the periphery of second language writing development. However, we suggest erring on the side of caution by fully examining whether the unfocused feedback has produced these less effective results or has it been the product of certain targeted linguistic features (e.g. English articles, verb tenses or prepositions) of these studies.

Meta-analyses of studies on corrective feedback (Brown et al. 2023; Kang and Han 2015; Kao and Wible 2014; Lim and Renandya 2020; Reynolds and Kao 2022) do not support the assertion that unfocused feedback is ineffective in decreasing linguistic errors. Conversely, these meta-analyses pointed out that unfocused feedback could be advantageous, though the effect size was modestly positive. Research on unfocused feedback has typically encompassed various error categories, indicating its low efficacy. Consequently, a thorough examination of the use of unfocused feedback to track specific error categories may uncover a more advantageous impact on those errors (Brown et al. 2023). For instance, previous studies showed that unfocused feedback effectively enhanced L2 students’ learning outcomes in definite and indefinite English article usages (Ellis et al. 2008), subject-verb agreement structures (Karimi and Fotovatnia 2012), and regular past tense use (Frear and Chiu 2015). These studies suggest a need for future analyses of the potential advantages of unfocused written corrective feedback on second language acquisition by examining student writers’ usage of specific linguistic features over time (Van Beuningen 2021).

In this sense, this study utilizes a quasi-experimental design to analyze the effects of unfocused written corrective feedback practices without manipulation, extending its focus beyond the traditional single error type study to include three linguistically distinct word classes: articles, prepositions, and verbs, which are typical item-based, idiosyncratic, and rule-governed error types, respectively, in previous corrective feedback research (Brown et al. 2023). This research design not only provides a more realistic reflection of actual classroom practices but also allows for an exploration into whether broader, less targeted, forms of feedback can still yield significant improvements in L2 writing. In addition, by diversifying the focus to include multiple grammatical word class categories, the study offers a unique opportunity to observe the nuanced effects of unfocused corrective feedback across different linguistic structures. This approach challenges the prevailing emphasis on narrowly focused feedback, potentially reshaping pedagogical strategies to accommodate a wider range of learning styles and linguistic needs in diverse educational contexts. The following research question was proposed to guide this research.

To what extent is unfocused direct corrective feedback effective in increasing linguistic accuracy in English article, prepositional and verb tense usages?

Literature review

The notion of error type in corrective feedback studies

Corrective feedback plays a crucial role in L2 writing as it helps learners identify and rectify their errors (Lee 2013; Zhang 2021). To implement corrective feedback effectively, it is crucial to understand the different types of errors identified in corrective feedback studies (Kao, 2024). Furthermore, the classification of these errors should consider the context-oriented nature of written corrective feedback (Lee 2020). It is generally beneficial to adhere to the error types employed by teachers in instruction, as this enables written corrective feedback to closely align with the teaching process. Various categorizations of errors have been proposed, such as local and global errors (Lee, 2013), treatable and untreatable errors (Ferris 2011), as well as grammatical and non-grammatical errors (Van Beuningen et al. 2012). Lee (2013) noted that while local errors, such as morphological errors, are made within clauses and do not hinder communication, global errors involving syntax and lexical errors can confuse the relations among clauses and lead to communication failure. In addition, Ferris (2011) has differentiated between treatable errors, which have grammatical rules for learners to follow (e.g. subject-verb agreement errors, verb tense errors, article errors), and untreatable errors, which are idiosyncratic and have no systematic rule for learners to consult (e.g. prepositional errors, word choice errors, collocation errors), arguing that written corrective feedback is more effective when targeted at treatable errors. Van Beuningen et al. (2012) made a distinction between grammatical errors, such as morphological and syntactic errors, and non-grammatical errors, such as spelling and punctuation errors. Grammatical errors arise from a sophisticated system linked to universal grammar, whereas non-grammatical errors pertain to orthographical mistakes that deviate from accepted conventions of language writing. Their findings indicate that direct written corrective feedback is more effective in addressing grammatical errors, while indirect corrective feedback proves to be more advantageous for non-grammatical errors.

The application of different error types in research contributes to the development of evidence-based practices in implementing corrective feedback. Truscott (2001) suggests that errors with straightforward issues in isolated elements are more amenable to correction, whereas errors originating from complexities within a system, particularly the syntactic system, are less likely to be successfully corrected. For example, lexical errors are often seen as engaging targets for correction (Truscott 2001). Conversely, syntax errors present a more complex challenge for both students and teachers (Ellis 1984). Considering both lexical and syntax errors, Kao (2024) highlighted that direct written corrective feedback assists learners in identifying their errors and explore both the lexical and syntax aspects of the target language. Through two experimental studies, Kao (2024) investigated the impact of direct corrective feedback on rule-based and lexically-based error types, finding that feedback targeting narrowly-defined rule-based but broadly-defined lexically-based error types can be effective. Extensive research has been conducted to explore the effectiveness of written corrective feedback, but these studies do not provide explicit instructions regarding the specific types of errors that were corrected (Kao 2023). Specifically, when the targeted error type was broadly defined (i.e. subject-verb agreement errors involving both copula be and lexical verbs), focused direct feedback did not effectively address learners’ subject-verb agreement errors. These findings suggest that corrective feedback effectiveness should vary with different error types.

Written corrective feedback on English article, prepositional, and verb tense usages

Many previous studies focused on only a few error types, particularly the English definite and indefinite articles (Bitchener and Knoch 2010; Lim and Renandya 2020; Shintani and Ellis 2013). Given their nuanced and contextually-dependent nature, articles often challenge language learners with form selection (i.e., a, an, the), omission, and overuse (Young 1996). Some previous studies have demonstrated that corrective feedback provided by teachers can improve learners’ accuracy in English article usages over time (Bitchener 2008; Chandler 2003; Hosseini and Branch 2015). In addition, the provision of metalinguistic explanations has also been found to enhance learners’ understanding and retention of correct English article usages, highlighting the importance of explicit instruction in the feedback process (Reynolds and Kao, 2021; Rezazadeh et al. 2015; Sheen 2007; Shintani and Ellis 2013). Shintani and Ellis (2013) compared the effect of direct corrective feedback and metalinguistic explanation on low-intermediate English as a second language students’ use of the English indefinite article in their writing. Their findings revealed that the direct corrective feedback had no impact on the accurate utilization of the English indefinite article, indicating that it did not benefit students’ L2 knowledge development. In contrast, metalinguistic explanations were found to facilitate student writers’ short-term learning of English indefinite article use in subsequent writing. Furthermore, Rezazadeh et al. (2015) demonstrated that metalinguistic explanations not only improved immediate post-test performance but also showed lasting benefits, maintaining improvements three weeks later, highlighting their potential for enduring impact in L2 acquisition.

Prepositional usages in English contribute to establish coherence and convey meaning within sentences, highlighting the significance of their accurate application for effective communication. Truscott (2001) noted that learners commonly encounter difficulties with prepositional usages, including associating a preposition with a given word, selecting the appropriate preposition, and using correct collocations. Consequently, studies have consistently investigated the effectiveness of corrective feedback in addressing these errors (Bitchener et al. 2005; Kassim and Ng 2014; Sachs and Polio 2007). For example, Bitchener et al. (2005) found that the average accuracy performance in prepositional usages did not differ between direct corrective feedback and direct corrective feedback along with student-researcher conference. This outcome is attributed to the idiosyncratic nature of prepositions, in contrast to more rule-bound grammatical structures. Kassim and Ng (2014) revealed that learners were able to maintain their accuracy in both immediate and delayed posttests, indicating the long-term effectiveness of corrective feedback on prepositional usages. Interestingly, their study revealed no significant differences between focused and unfocused feedback approaches, thus underscoring the broad applicability of corrective strategies in enhancing prepositional mastery.

In addition, errors related to verb tenses can be addressed effectively by using written corrective feedback (Benson and DeKeyser 2019; Bitchener et al. 2005; Yang and Lyster 2010), because they follow a structured and rule-based pattern (Ferris 1999; Truscott 2001). For example, Frear (2012) found that written corrective feedback had a positive impact on learners’ utilization of the regular past tense, but not on the irregular past tense. This finding suggests that verb tense structures with clear patterns are more amenable to improvement through corrective feedback. Additionally, Mujtaba et al. (2021) demonstrated that both the individual and collaborative processing groups in their study displayed a reduction in lexical, grammatical, and structural errors from the pre-test to the post-test across all nine error categories (i.e., word choice, word form, verb tense, verb form, subject-verb agreement, noun error, sentence fragment, comma splice, and run-on sentence), thereby confirming the effectiveness of indirect written corrective feedback in minimizing verb tense errors.

The effectiveness of unfocused written corrective feedback

Previous studies investigating the effectiveness of unfocused feedback have generally revealed insignificant differences in grammar accuracy between groups that received grammar error correction and those that did not (Kepner 1991; Robb et al. 1986; Semke 1984; Sheppard 1992). Building on these findings, Truscott (1996) reviewed these studies and concluded that error correction lacked robust evidence to support its efficacy. Subsequently, Truscott (2007) conducted a meta-analysis on the topic and determined that error correction exerted a slightly negative effect on students’ grammar accuracy in writing. Continuing this line of inquiry, more recent studies have consistently reported no significant differences in error correction outcomes between control groups and those receiving unfocused feedback (e.g., Chuang 2009; Deng et al. 2022; Rouhi and Samiei 2010; Sheen et al. 2009; Truscott and Hsu 2008). For example, Deng et al. (2022) investigated the effects of both coded focused and unfocused written corrective feedback by offering error codes (e.g. Art as article errors, V-T as verb tense errors, Prep as prepositional errors) to correct English as a second language learners’ linguistic errors in writing. No notable differences existed between the control group and the unfocused corrective feedback group across three error types: article usages, verb forms, and noun countability. This indicates that the unfocused corrective feedback group produced a similar number of errors in linguistic accuracy compared to the control group for the writing tasks. Conversely, the focused corrective feedback group demonstrated significantly improved performance when compared to the unfocused corrective feedback group.

Contrary to prior research, several studies have demonstrated promising outcomes favoring unfocused corrective feedback for error correction (e.g. Reynolds and Kao 2022; Ellis et al. 2008; Mujtaba et al. 2021; Van Beuningen et al. 2008, 2012). Specifically, Brown et al. (2023) found that an effective strategy for assisting students in enhancing overall accuracy may involve rotating the focus on different (individual) error types across various writing assignments or within longer written pieces. Alternatively, they proposed employing unfocused corrective feedback for shorter texts while reserving focused corrective feedback for lengthier texts (Brown et al. 2023; Lee 2020). These studies highlighted the potential advantages of unfocused feedback in terms of long-term learning outcomes (Reynolds and Kao 2022; Ellis et al. 2008; Mujtaba et al. 2021). Additionally, Loo (2022) contended that if the objective of written corrective feedback is to encourage students to develop awareness and understanding in writing discourse, then unfocused corrective feedback would be particularly effective. This method prompts students to address broader language and writing issues that influence their academic discourse. Consequently, unfocused written corrective feedback emerges as an optimal strategy to facilitate students’ engagement and awareness in their learning environment.

Material & methods

Participants

Eighteen male students and thirty-nine female students were recruited from a university in northern Taiwan to participate in the research. The students were sophomores, with an age range of 20–21. Before commencing the study, they were required to perform English language usage tests. The language usage test originated from the Structure and Written Expression section of the Test of English as a Foreign Language: Institutional Testing Program. The potential total for this section is between 31 and 68 points. This study recruited students whose English language proficiency was assessed between B1 and B2 (43–63 points) according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. The research participants were divided into two groups: one group that did not receive corrective feedback (N = 32) and one experimental group that received unfocused corrective feedback (N = 25). Both groups completed four writing assignments after the English language usage tests were completed. The first task was used as the pretest, the second and third as immediate posttests, and the fourth as a delayed posttest in a pretest–posttest–delayed posttest design.

The research methodology was reviewed and approved by The Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University under the reference no. 201810ES011. All participants were provided with a comprehensive explanation of the research purpose and information regarding the protection of their privacy, which included the assurance that their anonymity would be maintained throughout the study. Their participation was entirely voluntary, and withdrawal was not subject to any penalties. Before their participation, each participant signed an informed consent form that verified their understanding of the research procedures.

Targeted linguistic features

All the linguistic errors including both lexical and grammatical errors from students were corrected. The accuracy rates of students’ accurate usages in English articles, prepositions, and verb tenses were calculated to investigate the effect of written corrective feedback because the three linguistic features frequently occurred among students’ writing. In what follows, explanations of the three linguistic features are provided.

Initially, the accuracy rates of all functional uses of English articles were calculated, including the referential indefinite article “a” for the initial mention of a noun phrase and the referential definite article “the” for subsequent mentions. These uses have been the subject of a series of corrective feedback studies (e.g. Bitchener 2008; Ellis et al. 2008; Sheen 2007). The accuracy rates of other functional uses of the English article system were calculated as well, such as the use of the definite article in cases such as “I had spaghetti in the north,” in which “north” is mentioned for the first time, but “the” should be used. Moreover, the use of zero articles should be employed when referring to things or people in general, as in the sentence “I was scared of eating snake meat.”

In addition to the English article usages, the accurate rates of prepositional usages were calculated. A preposition is a linguistic element that precedes a noun, pronoun, or noun phrase, serving to indicate direction, time, place, location, spatial relationships, or to introduce an object such as “in,” “at,” “on,” “of,” and “to” and so on. While there are certain rules for prepositional usages, the majority of the usages involve idiosyncratic conventions of how a specific lexical item behaves, such as the choice of prepositions on “pay attention to” and “focus attention on” (Ferris 2011). Regardless of the variety of the functional usages of a preposition, the accuracy rates of all functional uses of the preposition were calculated to investigate the effects of corrective feedback.

The accurate rates of verb tenses including regular and irregular verbs were calculated as well. Regular verb tense errors are the most frequent inflectional errors in the morphological error type among EFL student writers; on the other hand, irregular verbs are verbs that do not adhere to the standard norms of conjugation in English, particularly with regard to the production of the past tense and the past participle such as “ate” in the past tense and “eaten” in the past participle for the lexical verb “eat” (Anggraeni, 2018). Verb tenses are grammatical forms of verbs that indicate the time of an occurrence, whether it is happening in the present, has already happened in the past, or will happen in the future. Verb tense errors occur when there are inconsistencies in the usage of verb tenses that impact the intended meaning and clarity. For example, a student writer might recount how they “enjoy dessert” by the time of another event in the past occurred. In this instance, the use of the simple present verb form “enjoy” is inaccurate and therefore indicates a verb tense error. The verb tense here should be past perfect “had enjoyed.”

Corrective feedback

In order to compare the results of this research with those of previous studies, only direct corrective feedback was provided to experimental groups, as the majority of unfocused feedback studies investigated the efficacy of direct feedback. The following are examples of corrective feedback on English article errors, prepositional errors, and verb tense errors.

Corrections on English article errors

Corrections on prepositional errors

Corections on verb tense errors

Writing tasks

Communicative tasks were designed in this study. Language features including English articles, verb tenses or prepositions targeted in this study are necessary, natural and useful to learning tasks. Students, therefore, incidentally do not intentionally use the three language features within a communicative context because they subconsciously produce these linguistic features to fulfill task demands (Ellis 2003). Students were invited to engage in a series of academic writing topics regarding food. They were requested to write 250–300 word essays about the following topics. Topic 1 (i.e. My Favorite Foods) serves as the pretest; topic 2 (i.e. Your Impressions of the Food from Another Country) and topic 3 (i.e. Your Thoughts on How the Foods You Eat Affect Your Health) serve as the immediate posttests 1 and 2; and topic 4 (i.e. Your Opinion about Genetically Altered Foods) serves as the delayed posttests.

Research procedures

Students in intact English writing classes were divided into two groups including one group that received no corrections and one experimental group that received unfocused corrective feedback. After taking English language usage tests, both groups were engaged in four communicative writing tasks. Using a pretest-posttest-delayed posttest design, the first task serves as the pretest; the second and the third, immediate posttests; and the fourth, delayed posttests.

The research procedures took place as follows. Performance on the first task was used to calculate all participants’ language accuracy. One week later, the unfocused feedback group received unfocused corrective feedback on all grammatical errors while the no corrective feedback group received no corrections on language errors. Content feedback was offered to control and experimental groups to help them write more communicatively. After receiving corrected essays, control and experimental groups were asked to read the feedback for ten minutes, revise their essays, and return the corrected revised essays. Immediately after reading the feedback, both groups were asked to complete the second writing task as a posttest 1. Again, both groups received content feedback for their writing organization. After they read the feedback, finished the revisions, and returned the essays, they were requested to finish the third writing task as a posttest 2. Eight weeks later, the fourth writing task as a delayed posttest in the similar form of the previous writing tasks was administered to determine whether the benefits of corrections could be retained. After two weeks, the two groups received content feedback for their future writing improvements. The research procedures for each group are summarized in Table 1.

Data analysis

The accuracy rates of language usages were calculated. The targeted language features were first scored respectively for correct uses in each obligatory context. These scores then respectively became numerators of ratios whose denominators were the sums of the numbers of obligatory contexts for the targeted linguistic features and the number of nonobligatory contexts for the improper use of language features (Pica 1991). For example, one of the participants produced 25 tokens of English article usages in an essay in which 20 tokens were required (i.e. number of obligatory contexts) and 5 tokens were overused (i.e. number of nonobligatory contexts) in the essay. Among the 20 tokens of English article usages, 18 tokens were regarded appropriate English article uses. Therefore, the participant’s accuracy rate of English article uses in this essay is 72%. The following equation showed how the accuracy rates of language usages were calculated.

Inter-rater reliability calculations between two raters were performed to show the agreement on the accuracy rate of specified language features in the initial analyses. At least 90% agreement was reached for the accuracy rate of the English article, prepositional usages and verb tenses separately after collaborative analyses on the instances in which two raters initially disagreed with each other. Eventually, 100% agreement was obtained for the accuracy rate of each linguistic features after more discussions and collaborative analyses. To answer the research question, data of students’ accuracy rates of language usages were submitted to two-way ANOVA to analyze the effects of the treatments in two posttests and one delayed posttest. If the interaction effect reached a significant level, statistical analysis of simple main effects was performed to separately investigate whether students improved from pretests to posttests and delayed posttests and whether the grammar correction effects could be detected between control and experimental groups in terms of their linguistic performance.

Results

This section reports on the statistical analyses performed to investigate the unfocused feedback effects on English article errors, prepositional errors, and verb tense errors separately. Tables 2–4 show the descriptive statistics for different error types. Table 2 presents both groups’ English article accuracy from the pretest to the posttest 1, posttest 2 and delayed posttest. The descriptive statistics for the unfocused feedback group were: pretest, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=83.20\), SD = 8.45; posttest 1, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=88.44\), SD = 8.71; posttest 2, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=86.24\), SD = 13.72; delayed posttest \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=96.32\), SD = 6.52. The descriptive statistics for the no corrective feedback group were: pretest, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=85.31\), SD = 4.13; posttest 1, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=85.09\), SD = 4.88; posttest 2, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=84.94\), SD = 5.67; delayed posttest \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=76.66\), SD = 16.12.

Table 3 presents both groups’ prepositional accuracy from the pretest to the posttest 1, posttest 2 and delayed posttest. The descriptive statistics for the unfocused feedback group were: pretest, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=89.20\), SD = 6.45; posttest 1, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=91.52\), SD = 7.54; posttest 2, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=90.48\), SD = 10.21; delayed posttest \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=90.20\), SD = 8.76. The descriptive statistics for the no corrective feedback group were: pretest, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.44\), SD = 7.23; posttest 1, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.78\), SD = 7.77; posttest 2, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.47\), SD = 12.95; delayed posttest \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=81.44\), SD = 17.38.

Table 4 presents both groups’ verb tense accuracy from the pretest to the posttest 1, posttest 2 and delayed posttest. The descriptive statistics for the unfocused feedback group were: pretest, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=84.52\), SD = 8.55; posttest 1, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=89.84\), SD = 6.29; posttest 2, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.16\), SD = 6.12; delayed posttest \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=90.32\), SD = 7.36. The descriptive statistics for the no corrective feedback group were: pretest, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=88.22\), SD = 5.51; posttest 1, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=81.66\), SD = 22.52; posttest 2, \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=90.59\), SD = 7.38; delayed posttest \(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.06\), SD = 7.62.

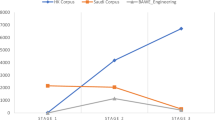

Figs. 1–3 illustrate the changes of students’ linguistic accuracy (i.e. article, prepositional and verb tense) from pretest, posttest 1, posttest 2 to delayed posttest for different groups. Figure 1 demonstrates the changes in English article accuracy from the pretest to the posttest 1, posttest 2 and delayed posttest between the two groups. What is noteworthy is that the English article accuracy in the unfocused feedback group soared from 86.24 in the posttest 2 to 96.32 in the delayed posttest while the article accuracy in the no corrective feedback group sharply dropped from 84.94 in posttest 2 to 76.66 in the delayed posttest.

Figure 2 illustrates the changes in prepositional accuracy from the pretest to posttest 1, posttest 2 and delayed posttest between the two groups. The prepositional accuracy in the unfocused feedback group appeared to slightly decrease from posttest 1 to posttest 2 and delayed posttest. On the other hand, there was a plunge in the no corrective feedback group’s prepositional accuracy in the delayed posttest.

Figure 3 demonstrates the changes in verb tense accuracy from the pretest to posttest 1, posttest 2 and delayed posttest between two groups. The verb tense accuracy in the unfocused corrective feedback slightly increased from the pretest to posttest 1 and posttest 2 but a slight decline of verb tense accuracy was observed in the delayed posttest. On the contrary, after the no corrective feedback group’s verb tense accuracy slumped from 88.22 in the pretest to 81.66 in posttest 1, the verb tense accuracy soared from 81.66 in posttest 1 to 90.59 in posttest 2 and 92.06 in the delayed posttest.

Three two-way ANOVAs were separately conducted to examine whether there were interaction effects for groups (unfocused feedback and no corrective feedback groups) and testing times (pretest, posttest 1, posttest 2 and delayed posttest) in terms of accuracy rates of different linguistic features. Statistically significant interaction effects for the groups and testing times were found in terms of the accuracy rates of English article usages (F = 16.32 p < 0.05, partial eta-squared = 0.23), prepositional usages (F = 4.41 p < 0.05, partial eta-squared = 0.07), and verb tense usages (F = 3.47 p < 0.05, partial eta-squared = 0.06) (Tables 5–7). The significant interaction effects indicated that there were differences in accuracy of the English article, prepositional, and verb tense usages for unfocused feedback and no corrective feedback groups in different testing times. Thus, to provide a deeper understanding of this result, simple main effects for the English article, prepositional, and verb tense usages were analyzed.

A statistically significant difference in the English article accuracy rate at different testing times was found in the unfocused feedback group (F = 8.05, p < 0.05) and in the no corrective feedback group (F = 8.53, p < 0.05). Therefore, the analyses of post hoc comparison were run for both groups. Post hoc results of the unfocused feedback group showed statistically significant differences between posttest 1 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=88.44\)) and the pretest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=83.20\)), delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=96.32\)) and the pretest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=83.20\)), the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=96.32\)) and posttest 1 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=88.44\)), as well as the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=96.32\)) and posttest 2 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=86.24\)). Post hoc results of the no corrective feedback group showed statistically significant differences between the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=76.66\)) and the pretest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=85.31\)), the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=76.66\)) and posttest 1 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=85.09\)), as well as the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=76.66\)) and posttest 2 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=84.94\)).

A statistically significant difference in the prepositional accuracy rate at different testing times was found for the no corrective feedback group (F = 7.96, p < 0.05) but not for the unfocused feedback group (F = 0.37, p > 0.05). Therefore, the analysis of post hoc comparison was run for only the no corrective feedback group. Post hoc results of the no corrective feedback group showed statistically significant differences between the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=81.44\)) and the pretest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.44\)), the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=81.44\)) and posttest 1 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.78\)), as well as the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=81.44\)) and posttest 2 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.47\)).

A statistically significant difference in the verb tense accuracy rate at different testing times was found for the unfocused feedback group (F = 6.66, p < 0.05) and the no corrective feedback group (F = 4.13, p < 0.05). Therefore, the analyses of post hoc comparisons were run for both groups. Post hoc results of the unfocused feedback group showed statistically significant differences between posttest 1 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=89.84\)) and the pretest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=84.52\)), posttest 2 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.16\)) and the pretest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=84.52\)), as well as the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=90.32\)) and the pretest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=84.52\)). Post hoc results of the no corrective feedback group showed statistically significant differences between the posttest 2 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=90.59\)) and posttest 1 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=81.66\)), the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.06\)) and posttest 1 (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=81.66\)), as well as the delayed posttest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=92.06\)) and the pretest (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=88.22\)).

Statistically significant differences in the English article accuracy rate for the unfocused feedback and no corrective feedback groups were found only for the delayed posttest (t = 6.28, p < 0.05) but not for the pretest (t = −1.15, p > 0.05), posttest 1 (t = 1.72, p > 0.05) and posttest 2 (t = 0.45, p > 0.05). Therefore, the analysis of post hoc comparisons was run for the delayed posttest. Post hoc results show a statistically significant difference in the delayed posttest results for students that received unfocused feedback (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=96.32\)) in comparison to those that did not receive corrective feedback (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=76.66\)).

Significant differences in the prepositional accuracy rates for the unfocused feedback and no corrective feedback groups were found for the delayed posttest (t = 2.48, p < 0.05) but not for the pretest (t = −1.76, p > 0.05), posttest 1 (t = −0.62, p > 0.05) and posttest 2 (t = 0.63, p > 0.05). The analyses of post hoc comparisons were run for the delayed posttest, showing a statistically significant difference between the unfocused feedback group (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=90.20\)) and the no corrective feedback group (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}=81.44\)) for the delayed posttest.

As to the effects of unfocused feedback on verb tense errors, no significant difference in the verb tense accuracy rates for the unfocused feedback and no corrective feedback groups were found for the pretest (t = −1.88, p > 0.05), posttest 1 (t = 1.96, p > 0.05), posttest 2 (t = 0.86, p > 0.05) and the delayed posttest (t = −0.87, p > 0.05).

Discussion

The impact of unfocused corrective feedback on English language accuracy

The present study investigated the effectiveness of unfocused corrective feedback in enhancing English article, prepositional, and verb tense accuracy among L2 student writers. Conducted over 18 weeks with 57 participants, this study utilized a pretest-posttest-delayed posttest design to assess the impact of unfocused feedback on linguistic accuracy. The participants were divided into two groups: a no corrective feedback group, which received only content feedback, and an experimental group, which received both content feedback and unfocused corrective feedback. Student writer performance for each linguistic dimension discussed in this study—articles, prepositions, and verb tenses—improved differently to the unfocused corrective feedback, challenging the prevailing assumptions about the universal inapplicability of unfocused feedback approaches. These outcomes underscore the necessity of aligning feedback strategies with specific linguistic targets to optimize learning outcomes in L2 writing instruction.

The study’s results reveal that unfocused corrective feedback significantly improved English article accuracy, particularly in the long term. This aligns with findings from Bitchener (2008), Ellis et al. (2008) and Hosseini and Branch (2015), who reported that explicit corrective feedback could enhance learners’ English article accuracy over time. This, nevertheless, contrasts with Shintani and Ellis (2013), who found that direct corrective feedback did not significantly impact the accuracy of English indefinite articles. Different from their study that focused only on English indefinite articles, this study targeted all the functional usages of English articles for correction, which might provide sufficient linguistic input to increase student writers’ understanding of the English article system. The current study’s results, therefore, highlight that unfocused corrective feedback, despite its broader approach, may provide sustained benefits in article usage, challenging the notion that focused feedback is always superior. What is noteworthy is that while the unfocused corrective feedback group demonstrated substantial gains from the pretest to the delayed posttest, the no corrective feedback group’s accuracy declined, which is similar to Bitchener et al.’s (2005) finding that student writers who did not receive corrective feedback tended to commit more definite article errors overtime. The result might lend support to the trade-off hypothesis (Skehan, 1998, 2009). In the current study, the no corrective feedback group that received only content feedback to improve their writing content and organization might pay more attention to their linguistic complexity and fluency at the expense of linguistic accuracy.

The unfocused corrective feedback group did not show any significant improvements in terms of the prepositional accuracy. The lack of significant improvement in the unfocused corrective feedback group supports Ferris (1999), who claimed that prepositional errors are often complex and resistant to unfocused corrective feedback. The prepositional usages, therefore, might benefit more from focused direct corrective feedback along with a student-teacher conference (Bitchener et al. 2005) or indirect corrective feedback (Kassim and Ng 2014). On the other hand, the no corrective feedback group significantly dropped in their scores from the pretest to the delayed posttest. The result might also buttress Skehan’s (1998, 2009) trade-off hypothesis which suggests that content feedback that aims to improve students’ writing content and organization should reduce their attentional resources for processing linguistic accuracy particularly for function words such as prepositions or articles that contain little substantive meaning.

In terms of verb tense accuracy, both groups showed improvements. However, the unfocused direct corrective feedback group did not outperform the no corrective feedback group, which is consistent with the findings of Frear (2012), who reported that unfocused corrective feedback, could positively impact verb tense accuracy but might not always lead to superior long-term outcomes. Frear and Chiu (2015) suggests that unfocused indirect corrective feedback should be more advantageous for regular past tense usages as it allows learners to recollect the concept of verb tenses. Since the majority of the verb tense errors in the current study involved regular past tense errors, the finding that verb tense structures could not benefit from corrective feedback echoes Truscott’s (2001) claim that errors involving inflectional morphology are normally least correctable. Such discourse-related features as verb tense use might be particularly difficult for intermediate-level student writers who are still at the learning stage of developing their linguistic and communicative competence because the selection of verb form is contingent upon a specific context.

Challenging assumptions with a closer look at unfocused corrective feedback

While the study generally aligned with existing literature on corrective feedback, several unexpected results emerged that warrant further examination and challenge conventional assumptions about the effectiveness of unfocused corrective feedback. These findings provide new insights into corrective feedback practices, particularly concerning the hidden effectiveness of unfocused corrective feedback on prepositional usage and verb tense accuracy.

An unexpected result of this study was the lack of significant improvement in prepositional accuracy for the unfocused corrective feedback group from the pretest to the delayed posttest. However, it is noteworthy that the unfocused corrective feedback group significantly outperformed the no corrective feedback group in the delayed posttest. This suggests that while the unfocused corrective feedback did not result in immediate, measurable improvements, it may have played a crucial role in helping learners retain their acquisition of prepositional usages over time. This contrasts with the general expectation that unfocused corrective feedback would lead to immediate improvements across various linguistic features. It appears that the maintenance of accuracy, rather than improvement, is a potentially significant benefit of unfocused corrective feedback, particularly when compared to the decline observed in groups receiving no corrective feedback. This finding suggests that prepositional errors, which are often nuanced and context-dependent (Ferris, 1999), may not benefit from unfocused corrective feedback. The idiosyncratic nature of prepositional usage, as highlighted by Bitchener et al. (2005), means that learners may require more focused, explicit feedback to address specific prepositional errors effectively. The absence of improvement in the unfocused corrective feedback group underscores the need for tailored feedback strategies that address the challenges associated with prepositional usage.

Another surprising result was the lack of significant long-term advantages of unfocused corrective feedback over content feedback for verb tense accuracy. Although both groups improved in their verb tense usage, the unfocused corrective feedback group did not outperform the no corrective feedback group in terms of long-term retention of verb tense accuracy. This outcome suggests that unfocused corrective feedback may not offer additional learning advantages for discourse-related features like verb tenses. The effectiveness of unfocused corrective feedback in addressing grammatical errors, which are often systematic and rule-governed (Truscott 2001), may be limited when compared to more focused feedback approaches. The lack of sustained improvement in the unfocused corrective feedback group could indicate that learners need more explicit and focused instruction to improve accuracy in complex grammatical areas over time.

The unexpected findings are important as they reveal the limitations of unfocused corrective feedback in effectively addressing L2 writers’ errors involving certain linguistic features. The results highlight that while unfocused corrective feedback can lead to some improvements, its broad approach may not always be the most effective for every type of error. Specifically, the lack of improvement in prepositional usage and the comparable long-term impact on verb tense accuracy suggest that unfocused corrective feedback may need to be complemented with more focused feedback strategies to address the diverse needs of language learners. These unexpected results emphasize the importance of considering the nature of specific linguistic features when teachers are designing corrective feedback strategies. They also suggest that further research is needed to explore how different types of feedback, including unfocused corrective feedback, can be optimized to support various aspects of language development more effectively.

Conclusion

This study examined the impact of unfocused corrective feedback on English article, prepositional, and verb tense accuracy, utilizing a comprehensive methodology involving pretests, posttests, and delayed posttests over an 18-week period. The primary findings indicate that unfocused feedback was effective in improving the accuracy of English article usages. However, no significant difference was found between the unfocused corrective feedback group and the no corrective feedback group in terms of the accuracy of verb tense use. In contrast, the effectiveness of unfocused corrective feedback on prepositional usage was not as marked, highlighting the need for more focused feedback strategies for this specific error type. The findings underscore the importance of incorporating unfocused corrective feedback in writing instruction, particularly for enhancing accuracy in articles and verb tenses.

This has practical implications for L2 writing teachers, suggesting that regular unfocused corrective feedback can support sustained language development. However, for more challenging areas such as prepositional usage, focused feedback approaches may be necessary to achieve similar improvements. For example, the implementation of both unfocused and focused corrective feedback is recommended for diagnostic purposes (Lee, 2017, 2019). Unfocused corrective feedback should be included in the initial writing to aid instructors in identifying specific types of errors for correction. In the following writing, teachers may provide focused feedback to address specific error types that remain unaddressed by unfocused corrective feedback. By aligning with existing literature, this study extends our understanding of unfocused corrective feedback’s role in learning to write in an L2. Previous research has shown mixed results regarding unfocused corrective feedback’s effectiveness, with some studies highlighting its limitations (e.g., Truscott, 1996; Sheen et al. 2009). This study’s positive outcomes in article accuracy provide new evidence supporting the use of unfocused corrective feedback, while also calling for further investigation into its effects on different linguistic features.

While this study offers valuable insights into the effectiveness of unfocused corrective feedback, several limitations warrant acknowledgment to fully appreciate the scope and implications of the findings. A primary limitation is the relatively small sample size of 57 L1-Chinese participants, which may not adequately represent the broader population of L2 writers, potentially affecting the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, the study concentrates solely on the impact of unfocused corrective feedback without a detailed comparative analysis with other feedback types. Although it included a no corrective feedback group receiving content feedback, a more extensive exploration involving focused corrective feedback and metalinguistic explanations would enrich our understanding of unfocused corrective feedback’s relative efficacy. Additionally, the research was limited to English article, prepositional, and verb tense accuracy. These grammatical features, while significant, constitute only a portion of the linguistic challenges faced by L2 writers, suggesting a need for broader linguistic assessments in future research.

To build on the current study’s limitations, future research could enhance understanding by adopting several strategic approaches. First, expanding the sample size and diversity is crucial to ensure broader representation and improve the generalizability of findings, potentially including participants from various linguistic and demographic backgrounds. Second, future studies should conduct systematic comparisons of unfocused corrective feedback with other types of feedback, such as focused corrective feedback and metalinguistic explanations, through parallel settings or factorial designs to clearly delineate their relative impacts and identify optimal practices. Finally, broadening the linguistic focus beyond article, prepositional, and verb tense usage to include other complex aspects of English grammar, such as idiomatic expressions and phrasal verbs, would provide a more comprehensive view of unfocused corrective feedback’s effectiveness across diverse linguistic challenges faced by L2 writers. These steps would significantly contribute to refining feedback methodologies and enhancing second language student writers’ instructional strategies.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

References

Anggraeni NKP (2018) Morphological and syntactical errors in English essays written by EFL students. INFERENCE: J Engl Lang Teach 1:74–81

Benson S, DeKeyser R (2019) Effects of written corrective feedback and language aptitude on verb tense accuracy. Lang Teach Res 23(6):702–726

Bitchener J (2008) Evidence in support of written corrective feedback. J Second Lang Writ 17(2):102–118

Bitchener J, Knoch U (2010) The contribution of written corrective feedback to language development: A ten month investigation. Appl Linguist 31(2):193–214

Bitchener J, Young S, Cameron D (2005) The effect of different types of corrective feedback on ESL student writing. J Second Lang Writ 14(3):191–205

Brown D (2012) The written corrective feedback debate: Next steps for classroom teachers and practitioners. TESOL Q 46(4):861–867

Brown D, Liu QD, Norouzian R (2023) Effectiveness of written corrective feedback in developing L2 accuracy: A Bayesian meta-analysis. Lang Teaching Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221147374

Chandler J (2003) The efficacy of various kinds of error feedback for improvement in the accuracy and fluency of L2 student writing. J Second Lang Writ 12(3):267–296

Chuang WC (2009) The effects of four different types of corrective feedback on EFL students’ writing in Taiwan. J DYU Gen Educ 4:123–138

Deng CR, Wang X, Lin SY, Xuan WH, Xie Q (2022) The effects of coded focused and unfocused corrective feedback on ESL student writing accuracy. J Lang Educ 8(4):36–57. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2022.16039

Ellis R (1984) Can syntax be taught? A study of the effects of formal instruction on the acquisition of WH questions by children. Appl Linguist 5(2):138–155

Ellis R (2003) Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ellis R (2009) A typology of written corrective feedback types. ELT J 63:97–107

Ellis R, Sheen Y, Murakami M, Takashima H (2008) The effects of focused and unfocused written corrective feedback in an English as a foreign language context. System 36:353–371

Ferris D (1999) The case for grammar correction in L2 writing classes: A response to Truscott (1996). J Second Lang Writ 8(1):1–11

Ferris D (2011) Treatment of error in second language student writing. University of Michigan Press

Frear D (2012) The effect of written corrective feedback and revision on intermediate Chinese learners’ acquisition of English. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Frear D, Chiu YH (2015) The effect of focused and unfocused indirect written corrective feedback on EFL learners’ accuracy in new pieces of writing. System 53:24–34

Gao Y, Wang X (2022) Towards understanding teacher mentoring, learner WCF beliefs, and learner revision practices through peer review feedback: A sociocultural perspective. J Lang Educ 8(4):58–72

Hosseini SB, Branch IST (2015) Written corrective feedback and the correct use of definite/indefinite articles. Int J N. Trends Educ Their Implic 6(4):98–112

Kang E, Han Z (2015) The efficacy of written corrective feedback in improving L2 written accuracy: A meta-analysis. Mod Lang J 99:1–18

Kao CW (2023) A preliminary investigation into student writers’ perception of corrective feedback focus. Feedback Res Second Lang 1(1):236–246

Kao CW (2024) Does one size fit all? The scope and type of error in direct feedback effectiveness. Appl Linguist Rev 15:189–218. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2021-0143

Kao CW, Wible D (2014) A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of grammar correction in second language writing. Engl Teach Learn 38:29–69

Karimi M, Fotovatnia Z (2012) The effects of focused vs. unfocused written teacher correction on the grammatical accuracy of Iranian EFL undergraduates. Asian EFL J 62:42–59

Kassim A, Ng LL (2014) Investigating the efficacy of focused and unfocused corrective feedback on the accurate use of prepositions in written work. Engl Lang Teach 7(2):119–130

Kepner CG (1991) An experiment in the relationship of types of written feedback to the development of second language writing skills. Mod Lang J 75:305–313

Kong A, Teng MF (2023) The operating mechanisms of self-efficacy and peer feedback: An exploration of L2 young writers. Appl Linguist Rev 14(2):297–328

Lalande II JF (1982) Reducing composition errors: An experiment. Mod Lang J 66:140–149

Lee I (2013) Research into practice: Written corrective feedback. Lang Teach 46(1):108–119

Lee I (2017) Working hard or working smart: Comprehensive versus focused written corrective feedback in L2 academic contexts. In J Bitchener, N Storch & R Wette (Eds.). Teaching writing for academic purposes to multilingual students: Instructional approaches (pp. 182-194). New York: Routledge

Lee I (2019) Teacher written corrective feedback: Less is more. Lang Teach 52(4):524–536

Lee I (2020) Utility of focused/comprehensive written corrective feedback research for authentic L2 writing classrooms. J Second Lang Writ 49:100734

Lee I (2023) Problematising written corrective feedback: A global Englishes perspective. Appl Linguist 44(4):791–796

Lee I, Luo N, Mak P (2021) Teachers’ attempts at focused written corrective feedback in situ. J Second Lang Writ 54:100809

Lee MK, Evans M (2019) Investigating the operating mechanisms of the sources of L2 writing self‐efficacy at the stages of giving and receiving peer feedback. Mod Lang J 103(4):831–847

Lim SC, Renandya WA (2020) Efficacy of written corrective feedback in writing instruction: A meta-analysis. TESL-EJ 24(3):n3

Liu Q, Brown D (2015) Methodological synthesis of research on the effectiveness of corrective feedback in L2 writing. J Second Lang Writ 30:66–81

Loo DB (2022) Unfocused Written Corrective Feedback for Academic Discourse: The Sociomaterial Potential for Writing Development and Socialization in Higher Education. J Lang Educ 8(4):193–198. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2022.12996

Mao Z, Lee I (2020) Feedback scope in written corrective feedback: Analysis of empirical research in L2 contexts. Assess Writ 45:100469

Mujtaba SM, Reynolds BL, Parkash R, Singh MKM (2021) Individual and collaborative processing of written corrective feedback affects second language writing accuracy and revision. Assess Writ 50:100566. Article

Peng CX (2024) Beyond accuracy gains: Investigating the impact of individual and collaborative feedback processing on L2 writing development. Assess Writ 61:100876

Pica T (1991) Foreign language classrooms: Making them research-ready and researchable. In B Freed (Ed.), Foreign language acquisition research and the classroom (pp. 393–412). Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath

Rahimi M (2019) A comparative study of the impact of focused vs. comprehensive corrective feedback and revision on ESL learners’ writing accuracy and quality. Lang Teach Res 25(5):687–710

Rastgou A (2022) How feedback conditions broaden or constrain knowledge and perceptions about improvement in L2 writing: A 12-week exploratory study. Assess Writ 53:100633

Reynolds BL (2023) Exploring learner attention and processing in second language writing: The role of eye-tracking and written corrective feedback. Feedback Res Second Lang 1(1):226–235

Reynolds BL, Kao C-W (2021) The effects of digital game-based instruction, teacher instruction, and direct focused written corrective feedback on the grammatical accuracy of English articles. Comput Assist Lang Learn 34(4):462–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1617747

Reynolds BL, Kao CW (2022) A research synthesis of unfocused feedback studies in the L2 writing classroom: Implications for future research. J Lang Educ 8:5–13

Rezazadeh M, Tavakoli M, Eslami Rasekh A (2015) The effects of direct corrective feedback and metalinguistic explanation on EFL learners’ implicit and explicit knowledge of English definite and indefinite articles. Two Q J Engl Lang Teach Learn Univ Tabriz 7(16):113–146

Robb T, Ross S, Shortreed I (1986) Salience of feedback on error and its effect on EFL writing quality. TESOL Q 20:83–95

Rouhi A, Samiei M (2010) The effects of focused and unfocused indirect feedback on accuracy in EFL writing. Soc Sci 5:481–485

Sachs R, Polio C (2007) Learners’ uses of two types of written feedback on a L2 writing revision task. Stud Second Lang Acquis 29(1):67–100

Semke HD (1984) Effect of the red pen. Foreign Lang Ann 17:195–202

Sheen Y (2007) The effect of focused written corrective feedback and language aptitude on ESL learners’ acquisition of articles. TESOL Q 41(2):255–283

Sheen Y, Wright D, Moldawa A (2009) Differential effects of focused and unfocused written correction on the accurate use of grammatical forms by adult ESL learners. System 37:556–569

Sheppard K (1992) Two feedback types: Do they make a difference? RELC J 23:103–110

Shintani N, Ellis R (2013) The comparative effect of direct written corrective feedback and metalinguistic explanation on learners’ explicit and implicit knowledge of the English indefinite article. J Second Lang Writ 22(3):286–306

Skehan PA (1998) A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Skehan PA (2009) Modelling second language performance: Integrating complexity, accuracy, fluency, and lexis. Appl Linguist 30:510–532

Truscott J, Hsu YP (2008) Error correction, revision, and learning. J Second Lang Writ 17:292–305

Truscott J (1996) The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Lang Learn 46:327–369

Truscott J (2001) Selecting errors for selective error correction. Concentric: Stud Linguist 27(2):93–108

Truscott J (2007) The effect of error correction on learners’ ability to write accurately. J Second Lang Writ 16:255–272

Truscott J (2023) What about validity? Thoughts on the state of research on written corrective feedback. Feedback Res Second Lang 1:33–53

Van Beuningen C (2021) Focused versus unfocused corrective feedback. In H Nassaji & E Kartchava (Eds.). The Cambridge handbook of corrective feedback in second language learning and teaching (pp. 300-321). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Van Beuningen CG, De Jong NH, Kuiken F (2012) Evidence on the effectiveness of comprehensive error correction in second language writing. Lang Learn 62:1–41

Van Beuningen C, de Jong NH, Kuiken F (2008) The effect of direct and indirect corrective feedback on L2 learners’ written accuracy. ITL Int J Appl Linguist 156:279–296

Yang Y, Lyster R (2010) Effects of form-focused practice and feedback on Chinese EFL learners’ acquisition of regular and irregular past tense forms. Stud Second Lang Acquis 32(2):235–263

Young R (1996) Form-function relations in articles in English interlanguage. Second language acquisition and linguistic variation, 135-175

Zhang TF (2021) The effect of highly focused versus mid-focused written corrective feedback on EFL learners’ explicit and implicit knowledge development. System 99:102493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102493. Article

Zhang ZV, Hyland K (2018) Student engagement with teacher and automated feedback on L2 writing. Assess Writ 36:90–102

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan—NSTC 112-2628-H-263-001 and the University of Macau MYRG2022-00091-FED.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CWK and BLR were responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Resources, Project administration, and Funding acquisition; CWK was responsible Software and Formal Analysis; BLR was responsible for Investigation; CWK, BLR, XZ, and MPW were responsible for Writing—Original Draft; CWK and BLR were responsible for Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted on December 19, 2018 by the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University under the reference no. 201810ES011. This approval included the review of the research protocol and the informed consent form.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in March 2019 by the first author. The participants were ensured of their anonymity and there were no risks involved with the participation in the study. The scope of the consent included participation, data use, consent to publish, and right to withdraw from the study. This study did not involve vulnerable individuals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kao, CW., Reynolds, B.L., Zhang, X. et al. The effectiveness of unfocused corrective feedback on second language student writers’ acquisition of English article, prepositional and verb tense usages. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1052 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05126-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05126-x