Abstract

Factors influencing environmental legislation have long attracted scholarly attention, yet existing research tends to focus on laws regulating market actors while relatively neglecting legislation that oversees government regulators and enforcement agencies. This study addresses this gap by uncovering the complex configurations of political, institutional, economic, and social drivers behind local environmental inspection legislation in China. Drawing on stakeholder theory and configurational policymaking perspectives, fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) was applied to data from all 31 provincial-level regions in mainland China, with five conditions—central political pressure, legislative stock for supervising administrative enforcement, secondary-sector economic share, allocation of enforcement resources, and public demand for environmental quality—calibrated into fuzzy-set scores. The analysis identifies three distinct pathways to robust local inspection laws: Industry-Driven Legislation under Low Central Pressure, Institutional Inertia-Driven Legislation, and Political Pressure-Driven Legislation. These results demonstrate that no single factor is sufficient on its own; instead, conjunctural combinations shape legislative outcomes. Higher-level accountability mechanisms and preexisting legal frameworks emerge as pivotal forces, while under certain configurations, local economic structures, public demand, and resource availability further influence enactment. These findings imply that legislation governing the supervision of environmental enforcement is shaped by multiple extra-legal factors, and that promoting the rule of law in environmental inspections requires moving beyond normative assertions to undertake in-depth consideration of higher-level political pressures, existing legislative stocks, and socio-economic development dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scholars have a long-standing tradition of conducting political-economic analyses of environmental legislation, which has yielded a wealth of research findings (Oates and Portney 2003). However, existing literature on environmental legislation tends to focus predominantly on laws that are implicitly regarded as “regulations of the market”. For instance, traditional theories view environmental regulation as a tool for internalizing negative environmental externalities (Oates and Portney 2003), while median-voter models often conceptualize industries as the primary targets of environmental legislation (Peltzman 1976; Stigler 1971). What if the target of environmental legislation is the government and its officials, rather than corporations or individual citizens? Unlike “laws regulating the market”, laws designed to “oversee the regulators” primarily impose legal obligations on environmental regulators (such as local environmental protection agencies and their officials) to diligently investigate environmental violations and ensure local environmental quality, accompanied by corresponding liability for non-compliance. Under such circumstances, what factors might influence the development of environmental legislation?

Although existing studies on the factors influencing environmental legislation are extensive, they remain insufficient to address the questions raised above. This limitation is evident in two main aspects: First, as noted earlier, most research—whether in the environmental field or other domains—focuses primarily on legislation regulating the market, with relatively little attention given to laws that oversee environmental regulators (Boyer and Laffont 1999; Dougherty and Heckelman 2008; Ekelund et al. 2010; Jenkins and Weidenmier 1999). The distinction between legislation regulating the market and laws overseeing environmental regulators lies in their respective governance targets and institutional functions. While the former primarily constrains market actors’ environmental behaviors through compliance mandates, the latter establishes accountability mechanisms for regulatory agencies themselves, addressing principal-agent dilemmas that could otherwise lead to lax enforcement, regulatory capture, or bureaucratic inertia. This institutional oversight dimension proves critical because even the most sophisticated market-oriented environmental laws risk becoming symbolic gestures if the regulators entrusted with their implementation lack effective supervision and performance evaluation frameworks (Gunningham et al. 1998; McAllister 2010).

Second, existing scholarship on environmental legislation has predominantly focused on analyzing the influence of individual determinants, such as conflicts between local economic interests and environmental objectives (Adetutu 2024), shifts in policymaker risk perceptions triggered by environmental disasters (Emam et al. 2020), disparities in subnational governance capacities (Provins 2024), and public opinion pressures amplified by climate extremes (Herrnstadt and Muehlegger 2014). These studies collectively emphasize how singular factors—whether institutional, perceptual, or socio-political—shape legislative outcomes. While emerging research has begun examining contextual drivers in non-Western settings, including China’s centralized environmental governance mechanisms like central inspection systems (Ding et al. 2022) and localized legislative responses to environmental accidents (Zang 2022), the field remains dominated by analyses of isolated variables rather than their systemic interactions. Such an approach, however, risks oversimplifying the complexity of environmental lawmaking, which is shaped by the interplay of political, economic, and institutional dynamics rather than any single determinant (Harrison and Sundstrom 2010; Vogel 2003). A fragmented analytical lens may obscure the cumulative and interactive effects of these factors, leading to partial or even misleading conclusions about the drivers of legislative change.

To bridge these research gaps, this study employs fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to examine the complex configurations of factors shaping environmental inspection legislation in China. The establishment of the Central Environmental Inspection System is widely regarded as a landmark event marking China’s shift in environmental governance from “regulating enterprises” to “regulating governments” (Feng et al. 2022). Since 2016, China has conducted three rounds of Central Environmental Inspections. However, this system is currently stipulated only in the internal Party regulation, Regulations on Central Environmental Protection Inspections, and has yet to be codified into national law. Consequently, the system has been criticized by scholars for its “lack of legitimacy” (Zhang 2017), its limited long-term effectiveness as a campaign-style governance tool (Tan and Mao 2021; Xiang and van Gevelt 2020), and its tendency to result in overly rigid enforcement practices at the local level (Kou et al. 2024). Against this backdrop, some regions have proactively incorporated the environmental inspection system into local legislation ahead of national codification. Regional approaches vary significantly in terms of whether and how environmental inspections are included in local laws. This variation provides valuable material for studying the factors influencing environmental inspection legislation. Adopting a configurational perspective and employing fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA), this study examines the local environmental inspection legislation of 31 provincial-level administrative regions in mainland China to identify and analyze the factors shaping such legislation.

This study offers potential contributions in three main areas: First, it fills a void in the study of the factors affecting “oversight of regulators” within environmental legislation. Second, it employs fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to rigorously explore the complex interactions among the various determinants shaping environmental lawmaking. Third, it broadens the research perspective on environmental inspections. While scholars have conducted extensive research on environmental inspections, the majority of studies have focused on the environmental governance performance resulting from central environmental inspections (Jia and Chen 2019; Li et al. 2020; Lin et al. 2021; Lu 2022; Pan and Hong 2022; Tan and Mao 2021; Wang et al. 2021; Wei and Kang 2023; Wu and Hu 2019; Yuan et al. 2022), their impacts on corporate investment, environmental information disclosure, and green technological innovation (Cheng and Yu 2023; Pan and Yao 2021; H. Wang et al. 2021; J. Wang et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2023), as well as their influence on regional industrial structure upgrading (Chen and Shen 2022; B. Wang et al. 2022; Zeng et al. 2023). However, there has been a lack of research specifically focused on environmental inspection legislation, particularly concerning provincial-level environmental inspection systems.

This study is structured into five sections. Apart from the Introduction, the second section provides an overview of China’s environmental inspection system, followed by an analysis of the factors influencing environmental inspection legislation from a political-economy perspective. The third section employs a configurational analysis approach, utilizing fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to conduct an empirical analysis of the factors affecting environmental inspection legislation. The fourth section focuses on the analysis and discussion of the empirical results. Finally, the fifth section presents the conclusions.

Context and theory

Environmental inspection system in China

Central environmental inspection practices in China

Since the beginning of the 21st century, China has increasingly emphasized strengthening environmental regulation in response to mounting environmental challenges. A milestone in this effort was the enactment of the revised Environmental Protection Law in 2014, widely regarded as “the strictest environmental protection law in history”. However, despite the introduction of a progressively comprehensive environmental regulatory framework, China’s environmental issues remain unresolved, leading to growing public dissatisfaction (Xiang and van Gevelt 2020). The central government attributes these persistent issues to a critical factor: the failure of local governments to fulfill their environmental protection responsibilities in accordance with the law. To ensure the effective implementation of local governments’ environmental obligations, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council jointly issued the Environmental Inspection Plan (Trial) in 2015, formally establishing the Central Environmental Inspection (CEI) systemFootnote 1.

The Central Environmental Inspection (CEI) refers to a mechanism through which the central government establishes dedicated inspection bodies to oversee the environmental performance of provincial-level Party committees, governments, and other relevant organizations. The CEI teams serve as the primary implementation entities, typically led by provincial-level or ministerial-level leaders from the central government, with the vice minister of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment acting as the deputy leader. Other team members include experts in environmental protection and officials from central government departments.

The scope of the inspections includes assessing regional compliance with national environmental laws, regulations, policies, standards, and plans; identifying and addressing prominent environmental problems; and examining how complaints from the public regarding environmental issues are handled. Sources of inspection leads include both information collected independently by CEI teams and environmental complaints lodged by the public. For cases of environmental damage resulting from failure or improper fulfillment of duties by local Party and government leaders uncovered during inspections, CEI teams are authorized to refer case leads to relevant authorities for investigation and accountabilityFootnote 2.

As of December 19, 2024, China has conducted three rounds of Central Environmental Inspections. The first round began in 2015 and was completed in 2018, covering all 31 provincial-level administrative regions. The second round, conducted from 2019 to 2022, also achieved full coverage of the 31 provincial-level regions across six batches. The third round commenced in November 2023 and, as of now, has completed three batches of inspections, covering 20 provincial-level regionsFootnote 3. Statistics from the first round of CEI reveal that over 135,000 public complaints were processed, resulting in penalties for approximately 29,000 enterprises, with total fines amounting to about 1.43 billion yuan. Additionally, 1518 enterprises faced criminal investigations, and 1527 individuals were detained. The inspections also led to the questioning of 18,448 Party and government officials and the accountability of 18,199 individualsFootnote 4.

Environmental inspection legislation in China

At the central legislative level, the Central Environmental Inspection (CEI) mechanism remains underdeveloped in formal legal frameworks. While Chinese central legislation typically operates through a three-tier hierarchy—comprising laws (法律), administrative regulations (行政法规), and departmental rules (部门规章)—CEI currently lacks anchoring in national laws or State Council-issued administrative regulations. Its sole statutory basis resides in a single departmental regulation: Article 3(6), 20, and 31(4) of the Measures for Supervision and Administration of Energy Conservation and Environmental Protection by Central Enterprises (2022) outline the obligations for the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) and central enterprises to cooperate with CEI activities.

Beyond this limited regulatory footing, CEI primarily derives authority from administrative normative documents (行政规范性文件). For example, the Implementation Opinions on Strengthening the Supervision and Management of Sewage Outlets into Rivers and Seas, issued by the General Office of the State Council in 2022, states that “the rectification and supervision of sewage outlets should be included as a key element in central and provincial-level environmental inspections”. Nonetheless, administrative normative documents (行政规范性文件) are not recognized as formal sources of law under the Legislation Law. The absence of formal legislation is the primary factor underpinning scholarly critiques regarding the CEI’s lack of legitimacy (Zhang 2017).

This contrasts markedly with provincial-level environmental inspection regimes, which exhibit greater legislative maturity. Twenty-four provincial-level jurisdictions have formally institutionalized environmental inspection systems through local legislations (地方性法规)—legislative instruments enacted by provincial People’s Congresses or their Standing Committees. These binding legal frameworks establish comprehensive procedures for inspection implementation, rectification mandates, and accountability mechanismsFootnote 5.

The term “local legislation” herein specifically refers to these province-level statutory instruments, distinct from both central-level departmental rules and non-binding administrative directives. This subnational legislative development addresses the regulatory gap observed at the national level, providing formalized legal bases for environmental governance that align with regional enforcement realities.

In terms of local legislative models for environmental inspections, three primary approaches can be identified: the comprehensive environmental legislation model (hereinafter referred to as the “comprehensive model”), the specific environmental legislation model (hereinafter referred to as the “specific model”), and the hybrid model combining comprehensive and specific legislation (hereinafter referred to as the “hybrid model”). Details of local environmental inspection legislation for each provincial-level region are provided in Table 1.

Specifically, the comprehensive model incorporates the establishment of environmental inspection systems into general environmental protection legislation. For instance, Article 28(1) of the revised Hunan Province Environmental Protection Regulations (2019) states: “The provincial people’s government shall inspect the performance of environmental protection responsibilities by lower-level governments, their achievement of environmental protection targets, improvements in environmental quality, and their resolution of prominent environmental issues. For violations identified during inspections, the relevant people’s government shall be urged to address them promptly in accordance with the law, and the results shall serve as a basis for assessment and evaluation. Inspection results shall be disclosed to the public”. A total of 10 provincial-level administrative regions have adopted the comprehensive model for legislating environmental inspections, including Shanghai, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Tibet, Qinghai, and Xinjiang.

The specific model refers to the establishment of environmental inspection systems within specialized environmental legislation. For example, Article 7 of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Water Pollution Prevention and Control Regulations (2019) stipulates: “The people’s government of the autonomous region shall establish systems related to water pollution prevention and control, including ecological protection compensation for water environments, monitoring and early warning of water environment carrying capacity, and environmental inspections”. A total of 3 provincial-level administrative regions have adopted the specific model for legislating environmental inspections: Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, and Henan.

The hybrid model establishes environmental inspection systems in both comprehensive environmental legislation and specific environmental legislation. For instance, Article 23 of the Tianjin Municipal Environmental Protection Regulations (2019) establishes a specialized inspection system for environmental protection: “The municipal people’s government shall establish an environmental supervision system to conduct routine supervision and specialized inspections of the implementation of environmental protection laws and regulations and the fulfillment of environmental quality responsibilities by municipal departments and district governments”. Meanwhile, Article 20 of the Tianjin Municipal Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality Promotion Regulations (2021) explicitly applies environmental inspection to the “dual carbon” field: “The implementation of laws, regulations, and responsibilities related to carbon peaking and carbon neutrality by municipal departments and district governments shall be included in environmental inspections”. A total of 11 provincial-level administrative regions have adopted the hybrid model for legislating environmental inspections: Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Jilin, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong, Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu, and Chongqing.

Factors driving environmental inspection legislation: a theoretical framework

The heterogeneity of provincial-level environmental inspection legislation in China’s political-legal landscape calls for a theoretical framework that captures the multi-actor dynamics inherent in legislative processes. Stakeholder theory—originally formulated by Freeman (2010) for corporate governance—posits that organizational decisions emerge from interactions among diverse actors who hold varying interests, wield different degrees of power, and offer distinct value propositions. This perspective has been effectively extended to environmental governance research, illuminating how government agencies, industries, civil society groups, and citizens negotiate competing priorities in regulatory policymaking (Driscoll and Starik 2004; Zhang and Cao 2015). Recent studies further demonstrate its utility in explaining environmental legislation variations through the lens of power-resource configurations among legislators, bureaucrats, and advocacy coalitions (Berrone et al. 2013; Delmas and Toffel 2008).

Drawing on existing research based on stakeholder theory, this study develops a tailored theoretical framework for analyzing local environmental inspection legislation in China. The framework identifies four primary stakeholder groups in the legislative process: legislators, enforcement authorities, market entities, and the general public. Legislators—embodied by local People’s Congresses and their Standing Committees—are responsible for drafting, reviewing, enacting, and amending laws (Bektas 2023; Trajkovska-Hristovska 2022). Although enforcement authorities typically have limited direct involvement in the legislative process, their role is pivotal in implementing laws and ensuring compliance, thereby translating legislative intent into practice (Van Kreij 2022). Market entities, such as industrial enterprises, actively shape legislative processes by providing information and lobbying for favorable policies, which can influence legislators’ perceptions of public opinion and the broader representation of societal interests (Hertel-Fernandez et al. 2019; Judge and Thomson 2019). Meanwhile, the public and civil society organizations participate through consultations and public hearings, contributing diverse perspectives and expertise essential for democratic representation and shaping legislative outcomes (Rasmussen and Toshkov 2013; Tao and Jasper 2022).

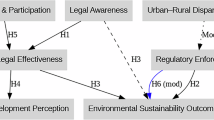

Building on “Power-Legitimacy-Urgency” framework by Mitchell et al. (1997), this study identifies the key stakeholders in local environmental inspection legislation and elucidates their interactional dynamics (see Fig. 1). The definition of significant stakeholders requires meeting at least two of the three dimensions outlined in the framework. In the context of China’s environmental inspection legislation, four categories of significant stakeholders are identified: legislators (local People’s Congress and its Standing Committee), enforcers (local governments and environmental protection departments), market entities (industrial enterprises), and the general public. The following sections will examine the three-dimensional attributes and roles of each stakeholder.

Legislators: local people’s congresses and their standing committees

Local legislative bodies possess high levels of power and legitimacy in the process of local environmental inspection legislation. This is primarily due to the exclusive powers granted to them by the ConstitutionFootnote 6 and the Legislation LawFootnote 7, which enable them to formulate, amend, and repeal local regulations. As the statutory authorities, they are the final decision-makers on whether local environmental inspection legislation will be enacted. However, because legislators must balance multiple interests during the drafting, revision, and deliberation phases of the legislation, their sense of urgency is relatively low. For instance, local People’s Congresses must weigh the accountability pressure from central environmental inspections, the capacity of local enforcement agencies, and the practical needs of local economic development. This process is often accompanied by complex negotiations and coordination of interests.

For legislators, an assessment of the existing legislative stock in a related field is typically conducted before initiating new legislation. Generally, if there is already a significant body of existing legislation, the likelihood of enacting new laws decreases (Fankhauser et al. 2015). Environmental inspections fall under the category of administrative enforcement supervision within the specialized domain of environmental protection. Prior to the enactment of local legislation on environmental inspections, there may already have been laws addressing administrative enforcement supervision in a general context. For legislators, if existing administrative enforcement supervision legislation sufficiently supports local environmental administrative enforcement efforts, there is little necessity to incorporate environmental inspections into local legislation. This is because enacting new laws imposes additional responsibilities on local legislators, such as conducting subsequent enforcement reviews and post-legislation evaluations, which significantly increase their workloadFootnote 8.

However, on the other hand, diverging from the conventional theories discussed above, this study contends that within the Chinese context, a larger legislative stock may actually promote a higher degree of local environmental inspection legislation. Specifically, local legislators do not necessarily approach environmental inspection legislation purely from a functional standpoint; they may also be driven by a desire to “keep pace with national policy trends” or to “outperform other regions”, resulting in these laws being difficult to enforce in practice and ultimately becoming “zombie provisions”Footnote 9. The research by Qin et al. (2023) has also noted that Chinese local legislative practice is characterized by an overemphasis on quantity at the expense of quality, as well as a tendency toward blind competitive behavior. In regions with a higher stock of enforcement supervision legislation, local legislators generally exhibit greater initiative and efficiency in the legislative process, which can help them distinguish their environmental inspection legislation efforts on a national scale.

Enforcers: local governments and environmental protection departments

In the context of local environmental inspection legislation, enforcers exhibit both high power and high urgency. The power of enforcers is reflected in their substantial capacity to influence the legislative process. According to Article 73 of the Legislation Law, although local governments do not hold direct legislative power, they can indirectly shape the content of legislation through activities such as drafting regulatory proposals, making legislative suggestions, and coordinating stakeholder interests. From a legitimacy standpoint, local governments’ participation in the legislative process must be bounded by their statutory functions. Article 59 of the Organic Law of Local People’s Congresses and Local Governments clearly assigns local governments the responsibility to “implement the resolutions of the local People’s Congresses”. However, proactive involvement in legislation can provoke controversy over “executive overreach” into the legislative domain, particularly within the framework of “campaign-style governance”, where policy-driven acceleration of legislation may undermine procedural legitimacy. The high urgency of enforcers stems from the rigid constraints imposed by central environmental inspections—such as deadlines for corrective actions and the public disclosure of accountability lists—which compel local governments to view legislation as a tool for risk mitigation.

For enforcers, their attitudes toward environmental inspection legislation are primarily influenced by two factors: motivation and capacity. First, central environmental inspections provide a strong impetus for local governments to improve environmental legislation (Ding et al. 2022). According to the Regulations on Central Environmental Inspections, inspection results serve as a critical basis for assessing the leadership teams and officials of inspected entities. These results are submitted to the relevant organizational (personnel) departments according to the cadre management authority for decision-making regarding rewards, punishments, appointments, and removals. Additionally, inspection teams must compile accountability issue lists and case files on significant environmental problems, along with any associated negligence or misconduct. These are transferred to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the National Supervisory Commission, the Central Organization Department, or other relevant authorities based on jurisdiction, procedures, and requirements.

Under the pressure exerted by central environmental inspections, provincial-level administrative regions may standardize procedures, methods, and criteria for provincial environmental inspections through local legislation. This allows for the establishment of routine inspection mechanisms that enable more comprehensive and in-depth monitoring of local environmental issues. These mechanisms can identify and address problems that central inspections might overlook or deprioritize, aiming to minimize exposed issues in subsequent rounds of central inspections. This paper argues that the greater the pressure from central environmental inspections, the stronger the motivation of local enforcers to support and promote local legislation on environmental inspections.

It should be explicitly stated that within the framework of this study, the central government is treated not as an independent legislative stakeholder but as an external source of pressure on local enforcers. This classification is based on the following considerations: the legislative authority for environmental inspections rests with the provincial People’s CongressFootnote 10, and the central government indirectly drives local legislation through the environmental inspection system (e.g., accountability case counts serving as pressure indicators), rather than by directly participating in the legislative process. In other words, the role of the central government is primarily manifested in its supervision and accountability mechanisms over local enforcers, rather than through the direct allocation of legislative resources (Du et al. 2023; Kou and Han 2021). Consequently, the political pressure exerted by the central government is internalized as a behavioral constraint on local enforcers rather than representing an independent stakeholder.

Additionally, enforcers’ attitudes toward environmental inspection legislation are constrained by their enforcement capacity. The formulation of laws often takes enforcement costs into account (Ehrlich and Posner 1974). If a region lacks sufficient enforcement resources to support the actual implementation of provincial environmental inspections, the corresponding local legislation would ultimately become an unenforceable “paper tiger”. Therefore, this paper contends that the more resources local governments allocate to environmental enforcement, the stronger the support of enforcers for local legislation on environmental inspections.

Market entities: industrial enterprises

In the process of local environmental inspection legislation, market entities hold both high power and high urgency. Market entities, particularly industrial enterprises, primarily participate in the legislative process through their economic influence (Liu and Ren 2023). When industrial enterprises anticipate that forthcoming environmental legislation may impact their operations, they often promptly exert pressure on local legislators through mechanisms such as emphasizing their tax contributions and job creation roles. This strategic lobbying aims to influence the legislative process in their favor (Hobbs 2020). However, the legitimacy of the demands from market entities, especially industrial enterprises, is relatively low, as their profit-maximizing goals often conflict with environmental protection obligations.

In general, for market entities, environmental legislation signals a tightening of regulatory oversight and the imposition of greater environmental obligations on industrial enterprises, potentially disrupting their routine production and business operations (Cai and Ye 2020). Consequently, industrial enterprises are inclined to oppose such measures. However, within the context of local environmental inspection legislation, these enterprises may exhibit two distinct responses.

On one hand, if the legislation primarily enhances the supervision of local environmental enforcement inaction, it indirectly increases regulatory pressure on industrial enterprises—thereby reinforcing their opposition. On the other hand, if the legislation functions to standardize local environmental inspection practices, it can protect the legitimate rights and interests of industrial enterprises by preventing local governments from overreaching in their enforcement effortsFootnote 11 to meet environmental performance targets (Slivka and Lesko 2021), which in turn may garner support from these enterprises.

Importantly, the eventual impact of environmental inspection legislation is not determined solely by its textual provisions—typically a blend of measures to address both enforcement inaction and overaction—but rather by the level of political pressure exerted by the central government (He et al. 2022). Specifically, under high central political pressure, local governments are more likely to emphasize measures curbing enforcement inaction, leading industrial enterprises to oppose the legislation. Conversely, under lower central political pressure, local governments tend to focus on mitigating excessive enforcement, thereby protecting industrial interests and securing their support.

The general public

In the process of environmental inspection legislation, the key characteristics of the general public are high legitimacy and high urgency. As an essential human right, the public’s demand for clean air and water carries both moral and legal legitimacy. The direct threat of environmental pollution to public health and quality of life further intensifies the immediacy of these demands. However, the public’s power to participate directly in the legislative process is limited, primarily relying on indirect channels such as petitioning and public opinion supervision to exert pressure. For example, environmental mass incidents may compel local governments to accelerate legislation, but the public faces challenges in directly intervening in legislative decision-making.

Local environmental inspection legislation is influenced by the public’s demand for environmental quality. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, when people have low incomes, their primary focus is on meeting basic survival needs, such as food and housing, with less attention given to environmental quality. However, as income levels rise and basic needs are met, people begin to focus on quality of life and higher-level spiritual needs, with a good environment becoming a key factor in fulfilling these higher-level needs (Maslow 1943).

Based on the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) theory, environmental quality may deteriorate during the initial stages of economic growth but improves as income levels reach a certain threshold. This improvement partly reflects increased demand for and provision of environmental protection in higher-income societies (Grossman and Krueger 1995).

In the legislative process, public demand for environmental quality can translate into environmental legislation. For instance, during the 2014 revision of the Environmental Protection Law, public feedback prompted lawmakers to add 14 provisions to the second draft and an additional 7 provisions to the third draft (Zhu and Wu 2017).

Methods and data

In this study, I have chosen to apply fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to investigate the factors influencing local environmental inspection legislation. fsQCA is particularly well-suited for examining complex causal relationships and identifying patterns across multiple cases, making it an ideal method for this research. Unlike traditional statistical techniques, fsQCA allows for the exploration of how different combinations of conditions lead to a particular outcome, providing a nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to the development of local environmental legislation.

The legitimacy of fsQCA is anchored in its foundations in set theory and Boolean algebra, with a focus on analyzing necessary and sufficient conditions for outcomes (Ragin 2000). This method operates under the principle of “causal complexity”, acknowledging that outcomes often result from combinations of conditions rather than isolated factors. Unlike regression-based methods that emphasize net effects, fsQCA examines how conditions interact conjunctively (through logical AND) and substitutively (through logical OR) to produce outcomes (Schneider and Wagemann 2012). This approach aligns with the study’s configurational perspective, which posits that local environmental legislation emerges from the interplay of political, economic, and social factors.

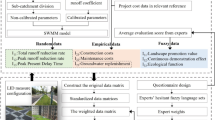

The fsQCA process comprises three key steps: calibration, truth table construction, and solution evaluation. First, variables are calibrated into fuzzy-set membership scores ranging from 0 (full non-membership) to 1 (full membership), reflecting the degree to which cases belong to a given set. A critical assumption underlying fsQCA is that set membership must be well-defined, which necessitates careful determination of appropriate cut-off points for fuzzy sets (Olsen and Nomura 2009; Tóth et al. 2017). Second, a truth table is constructed to systematically compare case configurations. This study analyzed 31 provincial-level cases, generating a truth table with 25 = 32 possible configurations. Third, logical minimization algorithms simplify complex configurations into parsimonious solutions, distinguishing between core and peripheral conditions (Rihoux and Lobe 2009).

The choice of fsQCA is justified by three methodological considerations. First, the study addresses the issue of “multiple conjunctural causation”, recognizing that different combinations of conditions may lead to the same outcome (Fiss 2011). For example, both public demand and political pressure might independently drive legislation under specific contexts. Second, the sample size (N = 31) is moderate, making fsQCA preferable to large-N regression methods that require stricter assumptions about linearity and independence. Third, fsQCA accommodates asymmetric causality, recognizing that the presence and absence of a condition (e.g., high vs. low political pressure) may have distinct effects on the outcome (Misangyi et al. 2017).

Despite its advantages, fsQCA is not without limitations. In addition to the challenges of establishing a well-defined set membership and determining appropriate fuzzy-set thresholds, there is an inherent risk of oversimplification. The subjectivity involved in setting these thresholds may also influence the configuration results, potentially affecting the robustness and generalizability of the findings. Acknowledging these limitations, this study has taken care to define and operationalize each condition in a manner that is both theoretically informed and empirically grounded, while remaining mindful of the methodological challenges posed by fsQCA.

Methods

This study primarily employs the fsQCA method to investigate the driving factors behind local legislation on environmental inspection. fsQCA is a case-oriented method that analyzes causal complexity from a configurational perspective, exploring combinations of multiple condition variables that lead to an outcome variable (Ragin et al. 2005). The fsQCA method posits that multiple combinations of conditions can lead to the same outcome (e.g., A × B + C × D = Y, where both A × B and C × D are sufficient combinations for the outcome Y). It also emphasizes that the effect of a single condition on the outcome is substitutable and asymmetric (e.g., if the combination of A and B leads to Y, it is possible for ~A, in combination with other conditions, to also produce Y).

To operationalize fsQCA, this study followed standardized procedures (Rihoux and Ragin 2009): First, continuous variables (e.g., per capita GDP) were transformed into fuzzy-set scores using direct calibration in fsQCA 3.0, with thresholds for full membership (0.95), the crossover point (0.50), and full non‐membership (0.05) determined through theoretical reasoning and case knowledge. We then conducted a necessity analysis to evaluate whether any single condition was necessary for the outcome (consistency > 0.90). Next, a truth table was constructed to define configurations and assess each configuration’s consistency (threshold = 0.80) and coverage. Boolean algebra was then applied to simplify the solution by eliminating redundant conditions, yielding the most streamlined configuration. Finally, the resulting solution was elucidated and interpreted in light of the study’s theoretical framework.

Data

Dependent variable: local environmental inspection legislation

Local legislation is a variable that is challenging to quantify. To ensure objectivity in this study, we adopt a binary approach by measuring whether a provincial-level administrative region has enacted relevant local legislation on environmental inspection, while avoiding subjective evaluations of legislative content.

Based on this standard, three questions are posed to assign values to local environmental inspection legislation across provincial-level regions: First, has the provincial-level region enacted internal Party regulations on environmental inspection? (If yes, the value is 0.5; if no, the value is 0.) Second, has the region incorporated environmental inspection into comprehensive environmental legislation? (If yes, the value is 1; if no, the value is 0.) Third, has the region incorporated environmental inspection into specific environmental legislation? (If yes, the value is 1; if no, the value is 0.)

It should be noted that provincial-level Party regulations do not strictly qualify as local legislation enacted by provincial legislative bodies, such as the provincial people’s congress or its standing committee. However, given that Party regulations constitute an important institutional source for environmental inspection, excluding them would omit critical information. Therefore, this study extends the scope of local environmental inspection legislation to include Party regulations. To distinguish between Party regulations and formal local legislation, the former is assigned a value of 0.5, while the latter is assigned a value of 1.

The analysis reveals eight possible scenarios for provincial-level environmental inspection legislation: “no legislation”, “Party regulations only”, “comprehensive environmental legislation only”, “specific environmental legislation only”, “Party regulations + comprehensive legislation”, “Party regulations + specific legislation”, “comprehensive legislation + specific legislation”, and “Party regulations + comprehensive legislation + specific legislation”. Following the coding rules, these eight scenarios are assigned six distinct values ranging from low to high (see Table 2 for details).

Independent variables

Political pressure from the central government

This study measures the political pressure exerted by the central government on provincial-level administrative regions through the number of environmental damage accountability cases transferred by the Central Environmental Inspection Teams. Environmental damage accountability cases refer to investigations and determinations of behaviors that violate environmental protection laws, regulations, or policies, or failures to fulfill environmental protection duties, resulting in environmental damage. These cases primarily hold government departments and their officials accountable.

As a result, environmental damage accountability cases heighten local governments’ attention to environmental inspection efforts, thereby accelerating the process of local environmental inspection legislation. Accordingly, this study collects data on the number of environmental damage accountability cases transferred to each provincial-level administrative region during the first round of Central Environmental Inspections and uses it as a conditional variable representing pressure from higher authorities.

Notably, this study exclusively utilizes data from the first round of Central Environmental Inspections due to the following two reasons: First, compared to other indicators, the environmental damage accountability cases transferred by the central government to local authorities during inspections offer a more direct measure of the political pressure exerted on local governments. For instance, while other environmental inspection-related metrics—such as the post-inspection accountability of local cadres—are available, the number of officials held accountable is determined by local authorities based on their independent investigations of potential legal violations. As a result, these figures do not directly capture the extent of political pressure imposed by the central government. Second, official disclosures on the website of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment indicate that only the first round provides complete and publicly accessible records of transferred accountability cases across all 31 provincial-level regions. In contrast, for the second round, accountability case statistics for 12 provinces remain undisclosedFootnote 12, and for the ongoing third round (since 2023), no provincial-level data have yet been released. This limitation necessitates reliance on first-round data to ensure methodological consistency and comparability.

The legislative stock for supervising administrative enforcement

As analyzed in Section “Legislators: local people’s congresses and their standing committees”, drawing on the approach of Fankhauser et al. (2015), this study uses the stock of administrative law enforcement supervision legislation in each region to represent the stance of local legislators on environmental inspection legislation. To achieve this, I collected all provincial-level legislations for administrative enforcement supervision enacted by the people’s congresses or their standing committees across China’s 31 provincial-level administrative regions.

Based on this dataset, I categorized and synthesized the legislative landscape of each region, and six distinct models of administrative enforcement supervision legislation were identified across provincial-level administrative regions. The various legislative models and their assigned values in this study are as follows: no local legislation or government regulations (0); only non-specialized local legislation (0.2)Footnote 13; only specialized local government regulations (0.4)Footnote 14; both non-specialized local legislation and specialized local government regulations (0.6)Footnote 15; only specialized local legislation (0.8)Footnote 16; and both specialized local legislation and specialized local government regulations (1)Footnote 17.

The share of the secondary sector

This study employs the share of the secondary industry as an indicator to represent industrial enterprises—key stakeholders in local environmental inspection legislation. This choice is based on three main considerations.

First, industrial pollution remains the primary source of environmental degradation in China (Shi et al. 2017), and empirical studies have shown that, controlling for other factors, regions with a higher secondary industry share tend to experience more severe pollution (Luo et al. 2018). Given this, industrial enterprises are among the market actors most directly affected by environmental legislation (Peng et al. 2018), which suggests they have a strong incentive to actively engage in and influence the legislative process.

Second, in this study, the secondary industry share is not used as a measure of regional environmental pollution but rather as an indicator of the bargaining power of industrial enterprises in environmental legislation. Generally, larger enterprises have stronger bargaining power in negotiations with the government (Egger et al. 2020). In the context of environmental regulation, industries that constitute a larger portion of a region’s economy, especially those in the secondary sector, typically exert greater influence over local environmental policies. This influence stems from their critical role in sustaining local economic stability and employment (Decker 2006).

Third, in existing literature, the share of the secondary industry is explicitly used as a key variable in both the theoretical framework and empirical analysis to examine its role in shaping the relationship between environmental tax legislation and air pollution reduction (Tang and Yang 2023).

Considering industrial enterprises’ motivation to engage in local environmental inspection legislation, the effectiveness of the secondary industry share in capturing their bargaining power, and its established use in existing environmental legislative research, this study argues that employing the secondary industry share as an indicator to analyze the role of industrial enterprises in local environmental inspection legislation is an appropriate approach.

Notably, as analyzed in the “Market entities: industrial enterprises” section, industrial enterprises may exhibit divergent attitudes toward environmental inspection legislation depending on the specific regulatory context—they may either oppose or support such legislation. The proportion of the secondary industry reflects the intensity of either support or opposition rather than a unidirectional stance. To capture this dimension, I compiled data on the proportion of the secondary industry from the China Statistical Yearbook (2018–2023) for China’s 31 provincial-level administrative divisions. The six-year average for each region was calculated as an indicator of its industrial structure.

Resource allocation for environmental enforcement

Drawing on the approach of Blundell et al. (2021), this study uses public fiscal expenditures on energy conservation and environmental protection to represent enforcement resources across provincial-level regions. Such expenditures provide financial support for environmental enforcement personnel, including equipment, salaries, and training, as well as funding for routine and specialized enforcement actions (Ercolano and Romano 2018). Similarly, the implementation of provincial-level environmental inspection systems also relies on these financial resources. Compared to general public fiscal expenditures, expenditures specifically allocated to energy conservation and environmental protection more directly reflect a region’s investment in enforcement resources.

I compiled data on public fiscal expenditures on energy conservation and environmental protection for China’s 31 provincial-level administrative regions from the China Statistical Yearbook (2018–2023). The six-year average for each region was calculated as an indicator of its enforcement resources.

Public demand for environmental quality

Following extant literature, this study employs per capita GDP at the provincial level as a proxy for public environmental demand (Ahmad et al. 2021; Pata 2018). The underlying rationale is that as per capita GDP increases, individuals’ basic material needs are increasingly satisfied. Drawing on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow 1943), once these lower-level physiological and safety needs are met, attention tends to shift toward higher-level aspirations, including the desire for improved environmental quality (Ahmad et al. 2021; Verbič et al. 2021). Consequently, higher per capita GDP is generally associated with a stronger public demand for environmental sustainability.

I acknowledge, however, that per capita GDP alone may not fully capture the complexities of public environmental demand, particularly in regions with varying levels of environmental awareness, divergent policy frameworks, and distinct socio-political contexts. While measures such as the frequency of public environmental complaints might offer a more direct reflection of public environmental concerns, my ability to utilize such indicators was limited. Specifically, according to the China Environment Yearbook (2018–2023), comprehensive data on public environmental complaints for the years 2017 and 2019 across provincial-level regions are unavailable.

Despite these limitations, per capita GDP remains a practical and consistent proxy within the scope of our analysis, providing a valuable comparative metric across China’s provinces.

Drawing on data from the China Statistical Yearbook (2018–2023), this study extracted per capita GDP figures for China’s 31 provincial-level administrative regions spanning 2017 to 2022. The six-year average per capita GDP for each region was then computed and employed as a proxy indicator for public environmental demand.

Table 3 summarizes the operational definitions, data sources, and calibration methods for each condition variable. Except for X2 (The Legislative Stock for Supervising Administrative Enforcement), which is directly assigned based on legislative model classification, all other variables are calibrated using the direct calibration method based on theoretical thresholds or percentile ranks (Ragin 2000). The specific calibration logic is detailed in the table.

Based on the established criteria for assigning and calibrating values for the outcome and condition variables, the 31 selected cases in this study were evaluated, yielding the results presented in Table 4.

Results and discussion

Necessity analysis of condition variables

The necessity analysis of condition variables aims to determine whether these variables are essential factors influencing the outcome. The preliminary criterion for identifying a necessary condition is that the necessary consistency score should exceed 0.9. After running calculations with the fsQCA 3.0 software, the output results for the consistency and coverage of the condition variables related to local environmental inspection legislation are presented in Table 4.

From the consistency results shown in Table 5, it is evident that the consistency scores for each individual variable fall below 0.9. This indicates that none of the condition variables are necessary conditions for the outcome variable; in other words, each individual condition variable can be substituted for others in the context of producing the outcome. Given this situation, it is essential to employ configurational analysis to explore which combinations of factors provide a sufficient explanation for local environmental inspection legislation.

Configurational analysis of conditions

Configurational analysis of high-level local environmental inspection legislation

After conducting the consistency test, it is necessary to perform a configurational analysis of the constructed truth table. First, the case frequency for the configurations should be set according to the sample size. Generally, the selected case frequency should retain at least 75% of the observed cases. Based on this criterion, this study sets the case frequency to 1. Next, the consistency threshold is established. Following research conventions, the threshold is set at the default value of 0.8 in fsQCA 3.0 (Ragin et al. 2005). Condition configurations with consistency below 0.8 are recorded as 0, while those above 0.8 are recorded as 1. Through configurational analysis, three types of solutions can be obtained: parsimonious solutions, complex solutions, and intermediate solutions. This study follows Ragin’s (2014) recommendation and adopts an intermediate solution for explanation. The results of the model analysis are presented in Table 6.

Analyzing Table 6 reveals that five distinct conditional configurations can lead to the achievement of high-level local legislation on environmental inspection. The model’s intermediate solution demonstrates robust explanatory power. On one hand, its consistency value of 0.877 indicates that 87.7% of the cases conforming to these configurations have successfully enacted high-level legislation; on the other hand, a coverage value of 0.624 shows that these five configurations account for 62.4% of the high-level legislative cases. Based on these configurations, we can further identify the corresponding roles of The Legislative Stock for Supervising Administrative Enforcement, Political Pressure from the Central Government, The Share of the Secondary Sector, Public Demand for Environmental Quality, and Resource Allocation for Environmental Enforcement in advancing local environmental inspection legislation. The following discussion elaborates on these relationships:

Pathway 1—3: Industry-Driven Legislation under Low Central Pressure

Pathway 1 indicates that when a region possesses a high legislative stock and strong public demand for environmental quality, it can still achieve a high level of local environmental inspection legislation even in the context of a high share of the secondary sector and low political pressure from the central government. This pathway has an initial coverage of 0.352, meaning that it accounts for 35.2% of cases exhibiting high-level environmental inspection legislation, with 2.2% of cases being exclusively explained by this pathway.

Pathway 2 shows that when a region has a high legislative stock coupled with abundant enforcement resources, it can also realize high-level local environmental inspection legislation despite a high secondary sector share and low central political pressure. This pathway explains 38.2% of cases, of which 2.4% are solely attributable to it.

Pathway 3 demonstrates that when a region features high public environmental demand together with substantial enforcement resources, it can achieve high-level local environmental inspection legislation even with a high share of the secondary sector and low central political pressure. This pathway explains 29.4% of cases, with 2.7% exclusively explained by this configuration.

At the level of provincial administrative divisions, these three pathways show some overlap, as all include Zhejiang ProvinceFootnote 18. The three pathways share a common feature: low central political pressure combined with a high proportion of secondary industry. This observation is consistent with the study’s theoretical assumptions. In contexts where local governments face minimal central oversight, industrial enterprises are less likely to view environmental inspection legislation as a threat; rather, such legislation operates as a regulatory framework that standardizes supervision and safeguards their legitimate rights. Across all pathways, low central political pressure and a dominant secondary industry emerge as pivotal factors—a combination we term the “Industry-Driven Model under Low Central Pressure”. Nonetheless, distinctions remain among the pathways. Path 1 is marked by a high legislative stock alongside strong public demand for environmental quality; Path 2 features a high legislative stock paired with abundant enforcement resources; and Path 3 exhibits strong public environmental demand and substantial enforcement resources. These findings suggest that in provincial administrative divisions characterized by low central political pressure and a dominant secondary sector, these conditions are functionally equivalent in fostering robust local environmental inspection legislation.

To provide a more concrete and intuitive illustration of Industry-Driven Legislation under Low Central Pressure, the following content will take Jiangsu Province as an example:

First, political pressure in the region has remained relatively low. During the second round of central environmental inspection conducted by the Second Central Environmental Protection Inspection Team from March 25 to April 25, 2022, only three environmental damage accountability issues were transferred to Jiangsu Province for investigationFootnote 19. This figure is notably lower compared to economically developed regions such as Guangdong Province and Shandong Province, which received five accountability cases each. Besides, according to statistics compiled by the author, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment has publicly reported 227 cases of insufficient local rectification following environmental inspections. Among these, Jiangsu Province accounted for only 5 cases, representing a mere 2.2% of the total. This indicates that Jiangsu has faced relatively limited political pressure during the implementation of central environmental inspection.

Second, in terms of economic structure, from 2017 to 2023, the secondary industry’s share of GDP in Jiangsu Province remained stable between 43% and 46%, significantly higher than the national average of approximately 39%. This reflects a strong industrial base and high reliance on secondary industry.

Third, regarding public demand, according to the 2019 China Environmental Yearbook, Jiangsu Province handled 88,775 environmental complaints in 2018, far exceeding the national average of 22,907 cases. This figure ranked first nationwide, accounting for 12.5% of the total complaints across all provinces, highlighting strong public demand for improved environmental quality.

Fourth, in terms of enforcement resources, from 2017 to 2022, Jiangsu Province’s average public fiscal expenditure on environmental protection and energy conservation reached 3.226 million RMB, ranking third nationwide. This substantial investment demonstrates robust environmental enforcement capacity.

Under the aforementioned conditions, Jiangsu Province promulgated the Jiangsu Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Regulation in 2022, which explicitly grants the provincial government the authority to supervise and inspect the soil pollution prevention performance of municipal governmentsFootnote 20. In 2024, Jiangsu Province promulgated the Jiangsu Environmental Protection Regulation, which provides a more comprehensive framework for provincial-level environmental inspection, including inspection formats, utilization of results, and rectification processesFootnote 21.

It is particularly noteworthy that the Jiangsu Environmental Protection Regulation explicitly stipulates that inspection authorities must publicly disclose inspection results and that inspected entities must disclose their rectification progress to the public. This legislative provision directly addresses public environmental demands and ensures citizens’ right to know. For a long time, the public’s right to information regarding local governments’ environmental inspection rectification efforts has lacked legal guarantees. The primary reason lies in the nature of the documents produced during inspections, which are often joint party-government documents. Such documents do not fall under the purview of the Regulations on Open Government Information, making it difficult for the public to access them through formal information disclosure requests.

For example, in the case of Yingkou Haigong Fuel Petrochemical Co., Ltd. v. Dashiqiao City People’s Government on Information Disclosure, the Dashiqiao City government conducted a “Special Rectification of Oil Storage and Transport Enterprises” as part of an inspection rectification initiative. The plaintiff, Yingkou Haigong Fuel Petrochemical Co., Ltd., was ordered to suspend operations due to insufficient regulatory compliance. Consequently, the plaintiff requested the disclosure of the “Detailed Measures and Responsibility List for the Special Rectification of Oil Storage and Transport Enterprises” from the Dashiqiao City government. Upon review, the court held that the document in question was jointly issued by the Dashiqiao Municipal Party Committee and the Dashiqiao Municipal Government, thereby classifying it as a party-government joint document. According to the Regulations on the Disclosure of Party Affairs, such documents do not fall within the scope of the Regulations on Open Government Information. As a result, the court rejected the plaintiff’s claimFootnote 22. This indicates that in the absence of explicit provisions in laws or administrative regulations, the specification of information disclosure obligations for relevant parties regarding the implementation of environmental inspection and subsequent rectification in local regulations can provide tangible legal guarantees for the public’s right to be informed about these inspections.

Pathway 4: Institutional Inertia-Driven Legislation

Path 4 demonstrates that when a region exhibits a high legislative stock alongside a low share of the secondary sector, it can still achieve high-level local environmental inspection legislation even under conditions of low central political pressure, limited public environmental demand, and scarce enforcement resources. This pathway explains 36.2% of the cases, with 11.4% of the cases being exclusively attributable to it. Unlike Paths 1, 2, and 3—which feature a high share of the secondary sector and other high-intensity factors—Path 4 is primarily driven by the existing legislative stock for enforcement supervision, rather than by high central political pressure, strong public demand, or abundant enforcement resources. Regions that conform to Path 4 include Gansu, Yunnan, and Tibet.

In these regions, environmental protection is a central pillar of governmental priorities. For example, environmental initiatives in Gansu are regarded as a key component in “strengthening the ecological security barrier in western China” as emphasized by President Xi Jinping during his visit to Gansu in September 2024Footnote 23. Yunnan is charged with the important mission of “strengthening the ecological security barrier in southwest China”Footnote 24. Tibet, meanwhile, is considered “an important national ecological security barrier occupying a key position in China’s ecological security framework”, with environmental supervision recognized as a critical means to bolster this barrierFootnote 25. Thus, given the paramount importance of environmental protection in these three western regions, coupled with institutional inertia, Gansu, Yunnan, and Tibet have been notably proactive in formulating local environmental supervision legislation. Consequently, this study categorizes Path 4 as an “institutional inertia-driven” model.

Taking Yunnan Province as an example, the political pressure it faces is relatively low, similar to Jiangsu Province, under the framework of central environmental inspection. During the central government’s “review” of previous inspections, Yunnan Province accounted for only two typical cases, below the national average of 2.76 cases per provincial-level region.

However, unlike Jiangsu Province, Yunnan’s economic development is less dependent on industrial activities, with the secondary industry accounting for only about 35% of its GDP. Regarding public demand, Yunnan handled 6,578 environmental complaints in 2018, significantly lower than the national average of 22,907 cases and accounting for only 0.93% of the total complaints nationwide. In terms of enforcement resources, Yunnan’s average public expenditure on environmental protection from 2017 to 2022 was 16.69 million yuan, below the national average of 18.59 million yuan.

Nevertheless, Yunnan Province has undertaken “high-level” local legislation on environmental inspection. Not only has Yunnan issued dedicated provincial-level Party regulations on inspections—such as the Measures for the Implementation of Environmental Inspection in Yunnan Province (promulgated in 2020)—but it has also integrated inspection mechanisms into comprehensive environmental protection legislation. For instance, Article 24 of the Regulations on Environmental Protection in Yunnan Province (promulgated in 2024) states: “A sound environmental inspection system shall be established and improved to supervise and inspect the implementation of environmental protection in accordance with relevant national and provincial regulations”.

Moreover, Yunnan has incorporated environmental inspection mechanisms into sector-specific environmental laws. Article 9 of the Regulations on the Prevention and Control of Environmental Pollution by Solid Waste in Yunnan Province (promulgated in 2022) stipulates: “The provincial government shall include the prevention and control of environmental pollution by solid waste in the provincial environmental inspection framework, inspecting the fulfillment of related responsibilities by relevant departments and subordinate governments”.

In terms of the function of local legislation on environmental inspection, rather than alleviating industrial structural pressures or improving environmental quality, institutional inertia-driven legislation primarily serves to establish the environmental inspection system. Consequently, the content of such legislation is largely declaratory, focusing on the formalization of the inspection framework while lacking detailed procedural provisions. Scholars often refer to this approach as “institutional empowerment” (McElwee 2010). For example, Yunnan Province has incorporated environmental inspection systems into nine pieces of local legislation—the highest number among all provincial-level regions in China. These laws uniformly proclaim the establishment of a provincial-level inspection system without offering detailed provisions for its operation. For instance, Article 24 of the Regulations on Environmental Protection in Yunnan Province (promulgated in 2024) states: “A sound environmental inspection system shall be established and improved to supervise and inspect the implementation of environmental protection in accordance with relevant national and provincial regulations”. Similarly, Article 9 of the Regulations on the Prevention and Control of Environmental Pollution by Solid Waste in Yunnan Province (promulgated in 2022) stipulates: “The provincial government shall include the prevention and control of environmental pollution by solid waste in the provincial environmental inspection framework, inspecting the fulfillment of related responsibilities by relevant departments and subordinate governments”.

Pathway 4 represents a model of local legislation on environmental inspection driven by the core impetus of a high legislative stock for supervising administrative enforcement. This pathway demonstrates that even in the absence of significant political pressure, strong public demand, or ample enforcement resources, regions with relatively low dependence on secondary industries and a strong emphasis on legislative oversight and environmental protection can actively advance local legislation on environmental inspections.

Pathway 5: Political Pressure-Driven Legislation

Path 5 demonstrates that when a region is characterized by a high legislative stock, high central political pressure, a low share of the secondary industry, and high public demand for environmental quality, even limited enforcement resources do not preclude the achievement of high-level local environmental inspection legislation. This pathway accounts for 25.6% of the cases, with 6.3% being exclusively attributable to this configuration. Liaoning Province is a prototypical example of Pathway 5:

First, in terms of political pressure, the Central Third Environmental Inspection Team conducted an inspection in Liaoning Province from April 25 to May 25, 2017, identifying 14 cases of accountability for ecological and environmental damage, a notably high number.

Second, regarding economic structure, the secondary industry in Liaoning accounted for approximately 38% of GDP from 2017 to 2022, lower than Jiangsu Province but slightly higher than Yunnan Province.

Third, in terms of public demand, Liaoning received 45,297 environmental complaints in 2018, significantly higher than the national average of 22,907 cases, accounting for 6.4% of the total—among the highest nationwide.

Fourth, as for enforcement resources, Liaoning’s average public expenditure on environmental protection from 2017 to 2022 was only 9.73 million yuan, far below the national average of 18.59 million yuan.

Following the first round of central environmental inspection, Liaoning introduced the Provisional Guidelines for Handling Matters Assigned by Environmental Inspection in Liaoning Province in 2019. In 2022, during the amendment of the Regulations on Air Pollution Prevention and Control in Liaoning Province, the environmental inspection system was formally incorporated. Article 25 of the amended regulations states:

“The provincial government shall establish and improve an air environment protection inspection system, ensure regular inspections, strengthen accountability, and promptly disclose inspection results.

For major air environment violations or significant air pollution issues that are inadequately addressed or provoke strong public concerns, the provincial environmental department shall prioritize supervision in accordance with relevant regulations and publicly disclose the supervision results.”

In terms of legislative content, under the dual influence of political pressure and strong public demand, the Regulations on Air Pollution Prevention and Control in Liaoning Province emphasize both the effectiveness of inspection and rectification and the transparency of inspection processes. Specifically, Clause 2 of Article 25 underscores the importance of disclosing key supervision results to the public, aiming to enhance accountability and social oversight.

Pathway 5 represents a model of local legislation on environmental inspection driven primarily by political pressure. This pathway illustrates that under conditions of significant political pressure and strong public demand, regions may actively promote such legislation despite limited enforcement resources.

Regions following this model typically exhibit levels of economic development and dependence on secondary industries that fall between those observed in Pathways 3 and 4. Without political pressure from the central government, even strong public demand alone would not suffice to motivate these regions to enact local inspection legislation, as their lack of sufficient enforcement resources would undermine their ability to do so effectively.

Configurational analysis of low-level local environmental inspection legislation

Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) emphasizes the asymmetry of causal relationships. Therefore, this study further examines the specific configurational conditions that lead to low-level environmental inspection legislation. The intermediate solution is presented in Table 7. The results indicate that a provincial administrative region tends to exhibit low-level environmental inspection legislation under two distinct conditions. The overall consistency of these two pathways is 0.866, meaning that 86.6% of the cases conforming to these configurations exhibit low-level environmental inspection legislation. The overall coverage is 0.512, suggesting that these two configurations collectively explain 51.2% of the cases characterized by low-level environmental inspection legislation. The detailed interpretations are as follows:

Pathway 1 indicates that when a region has a low legislative stock for enforcement supervision, low central political pressure, low public demand for environmental quality, and limited enforcement resources, it is likely to exhibit low-level environmental inspection legislation. This pathway has a raw coverage of 34.1%, meaning it accounts for 34.1% of the cases with low-level legislation. Representative regions following this pattern include Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Qinghai Province, Guizhou Province, and Hainan Province. These results corroborate the high-level environmental inspection legislation model—termed “Industry-Driven Legislation under Low Central Pressure”—by showing that even in areas with a high share of secondary industry and low central political pressure, robust legislation emerges only when at least two of the following conditions are met: high legislative stock, strong public demand for environmental quality, and abundant enforcement resources. Failure to satisfy these conditions invariably results in low-level legislation, underscoring that an industry-driven approach requires supportive external factors.

Pathway 2 reveals that even if a region has a low share of the secondary sector, high public demand for environmental quality, and abundant enforcement resources, its environmental inspection legislation remains weak if the legislative stock for enforcement supervision is low. This pathway explains 28.8% of the cases characterized by low-level legislation, with representative regions including Beijing, Shanghai, and Hunan Province. The analysis further suggests that in regions with both low legislative stock and low secondary sector share, central political pressure exerts minimal influence on legislative outcomes. In conjunction with the Political Pressure-Driven Legislation model for high-level legislation, these findings indicate that high central political pressure can effectively promote robust legislation only when accompanied by a high legislative stock.

Notably, both pathways highlight a common constraint—low legislative stock for enforcement supervision—which appears to be a critical bottleneck in advancing environmental inspection legislation in these regions. This empirical finding diverges from some existing research. Generally, when a significant body of legislation already exists, the likelihood of enacting new laws tends to decrease (Fankhauser et al. 2015). However, this study demonstrates that a high legislative stock facilitates a higher degree of local environmental inspection legislation, while a low legislative stock tends to result in less comprehensive local legislation in this area. This finding partially validates the theoretical hypothesis proposed in Section “Legislators: local people’s congresses and their standing committees”, suggesting that local legislators do not approach environmental inspection legislation purely from a functional perspective; they may also be motivated by a desire to “keep pace with national policy trends” or to “outperform other regions”.

Conclusion

Local legislation on environmental inspection is a crucial manifestation of the rule of law in the inspection system and a key pathway to promoting regular inspections and avoiding “campaign-style governance”. This article conducts a configurational analysis of the influencing factors on local legislation for environmental inspection across 31 provincial-level administrative regions in China, identifying three pathways: “Industry-Driven Legislation under Low Central Pressure”, “Institutional Inertia-Driven Legislation”, and “Political Pressure-Driven Legislation”. These pathways delineate the internal logic of how various regions advance local legislation for environmental inspection under different legislative stocks, political pressures, and socio-economic development characteristics.