Abstract

This study aimed to design an online, collaborative, project-based environment and process based on constructivist learning to enhance teachers’ design thinking skills and to test the effectiveness of the application. In the study, design thinking skills were tried to be developed online with processes based on scenario writing and animation. Since there is a need for interdisciplinary collaborative work due to the nature of design thinking, the study was carried out with a sample consisting of 7 history teachers, 7 geography teachers, and 8 social studies teachers. A total of 1080 min of online project-based design thinking teaching was given to teachers by the researcher for 12 days, 90 min per day. The study was designed with an embedded complex mixed methods research design. In the study, quantitative data were collected at the beginning and end of the implementation, while qualitative data were collected before, during, and at the end of the implementation. The designed design thinking teaching process was successfully carried out within the scope of the constructivist learning approach, in an online learning environment, in a project-based teaching process, by applying learning practices. At the end of the process, contributions were observed in terms of professional development, such as a roadmap for design thinking, project ideas, interdisciplinary and teamwork. The processes and outcomes of the research have contributed to the development of an instructional design grounded in design thinking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Instructional design is a field of study that provides clear guidance to help people learn and develop more effectively (Reigeluth, 1999). Instructional design, with its general goal to facilitate learning and make it more efficient and effective, is a problem-solving process that addresses skill and knowledge gaps (Morrison et al. 2012). This process starts with identifying the problem, and then the solutions that are considered appropriate are identified and tested. In other words, instructional design is the decision-making process for systematic design and planning of instruction. Teachers, as the designers of environments where the learner and what is to be learned come together, are one of the fundamental elements of this process. Teachers are instructional designers who have duties and responsibilities such as transforming the language of science into the language of daily life, creating a positive classroom experience, and producing effective uses by manipulating tools and methods. The achievement of these functions is closely related to teachers’ design thinking skills.

Tsai and Chai (2012) cite three key obstacles to creating instructional technology. The first is the problem of access to technology, while the second is related to pedagogical beliefs and skill issues related to technological integration. These two obstacles have already been largely overcome. The third obstacle is the problem of design thinking, in other words, the weakness of design thinking. In other words, it is related to the level of having a creative thinking form that involves the skills of presenting or doing different options for doing something different. Additionally, it is a desire to make an effort regarding this and self-efficacy. Scheer et al. (2012) emphasized the need for design thinking research in teacher education, highlighting that design thinking could bridge the gap between theoretical findings in pedagogical science and the actual implementation in schools. Additionally, based on the findings of the study, Özaydınlık (2024) recommends the implementation of design thinking instruction through a mixed-methods approach to address the gap in the literature.

Design thinking seems to support teachers in developing new thinking skills. Design thinking is a way of thinking that supports creativity in design processes, emphasizes creative confidence and competence, and is valid and critical in all process designs, including teaching processes (Rauth et al. 2010). Researchers have widely agree that design thinking is a promising teaching approach, especially in higher education. (Guaman-Quintanilla et al. 2023; Lynch et al. 2021; Thuan and Antunes, 2024).

Review of design thinking literature

Design thinking has been addressed and interpreted by many different disciplines. This situation has made it difficult to reach a consensus on the definition of design thinking. Design thinking has become a paradigm that is thought to be useful in solving many problems in different fields (Dolata and Schwabe, 2016; Dorst 2010; Liedtka, 2018; Owen, 2007; Vanada, 2013). According to Friedman (2003), design is a goal-oriented process that is carried out to solve problems, meet needs, transform less desirable situations into preferred situations by improving conditions, or produce new and useful things. On the other hand, the nature of design as an integrative discipline is related to six common areas: Natural sciences, humanities, social sciences, service sector, arts, technology, and engineering sciences (Friedman, 2003). Design thinking allows exploration in complexity, enabling an approach with nonlinear thinking to nonlinear problems (Kolko, 2015). Design thinking is of great importance for the elimination of chaotic, ambiguous, and complex problems (Buchanan, 1992; Liedtka, 2015; Pande and Bharathi, 2020; Schoormann et al. 2023). Design Thinking seems important for solving complex problems and achieving mental transformation. Although there are many definitions of design thinking, the one adopted in this study by Rauth et al. (2010) is viewed as a way of thinking that fosters creativity in design processes, emphasizes creative confidence and competence, and is essential and applicable to all process designs, including teaching processes.

Key characteristics of the design thinker

Brown (2008) stated that people with design thinking do not necessarily have to receive design education, and stated that individuals with design thinking can empathize, think holistically, and are optimistic, experimental, and collaborative. Design thinking is based on expansive thinking that includes numerous alternative solutions and experiments, while individuals who can prefer the most suitable one in decision contexts with high uncertainty are considered design thinkers (Liedtka, 2015). Accordingly, design-oriented thinkers are future-focused, produce hypothesis-based results, have the potential to produce radical innovation, and are agile in thinking (Liedtka, 2015). It can be stated that the model preferred or developed while operating the design thinking process, the tools chosen, and the flow and efficiency of the process are directly related to the characteristics of the design thinker (Chesson, 2017; Sürmelioğlu and Erdem 2021).

Chesson (2017) listed the characteristics of the design thinker as a dynamic mind, human-centered, empathetic, visual, comfortable in uncertainty, prototyping, reflective, open to taking risks, embracing failure, collaborative, and optimistic. Dosi et al. (2018) listed the characteristics of a design thinker as being someone who embraces risk and uncertainty, is human-centered, empathetic, process-aware, has a holistic perspective, problem-solver, interdisciplinary, open to diversity, learning-focused, critically questioning, expansive thinking, anticipatory, and optimistic. Sürmelioğlu and Erdem (2021) have categorized the design thinker characteristics that teachers should possess into four dimensions (relationship, process, individual, and ethics), as shown in Table 1.

With these identified characteristics, design thinking in technology-based instructional design represents a relationship-focused, human-centered, and ethical process.

Design thinking models

Design thinking, as a solution-oriented design method, helps overcome complex problems by sustaining in-depth learning processes in problem perception and various solution paths (Kröper et al. 2011). According to Doppelt (2009), the design process has a general structure consisting of six stages: Defining the problem and identifying the need, gathering information, coming up with alternative solutions, choosing the most appropriate solution, designing and developing a prototype, and evaluating. Brown (2008) stated that the design process is the result of a creative, human-centered exploration process strengthened by the iterative and intensive work of prototyping, testing, and improvement. According to Brown (2008), design processes should go through three stages; inspiration, ideation, and implementation. These stages are “inspiration” for situations that motivate the search for solutions, “ideation” for the process of generating, developing, and testing ideas that can lead to solutions, and “implementation” for planning a path to the market.

As can be seen, the design process includes different activities. These processes have been transformed into a logical methodological research system with design thinking models. Design thinking models involve organized technical processes that provide reliable data on researchable phenomena and processes, and can be applied to identify process management practices and predict outcomes (Irbīte and Strode, 2016). Many different design thinking processes have been modeled in the literature, and almost every model can be used in many different disciplines.

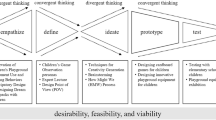

Stanford University’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (d.school) is the leading university for teaching design thinking (Stanford Üniversitesi Hasso Plattner Institude of Design, 2010; The Interaction Design Foundation, 2024). According to d.school, the five stages of design thinking (empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test) are shown in Fig. 1. These processes can be carried out in parallel, repeated, and at any stage of the process, one may revert to a previous phase (Baraji and Siang, 2025; Yeung and Ng, 2023; Sürmelioğlu, 2021).

As can be seen in Fig. 1, the stages of design thinking are not linear. According to the model, the first stage is about understanding the user’s point of view. At this stage, various empathy techniques such as 5 W questions, interviewing the relevant person/s, and interacting with the user are used. At the definition stage, the problem is clearly revealed. When defining the problem, a human-centered approach is taken, a broad space is created for creative thinking, and the user’s empathy map, experience map, and analogy map are drawn. At the ideate stage, creative solutions are developed through brainstorming. After the ideation, the prototype stage begins. In this stage, design thinking seeks answers about the feasibility of the idea until it is tested with real users. It can be created with tools such as social media, websites, cardboards, etc. According to the model, the final stage is the test. The purpose of the test stage is to determine what works and what doesn’t, and to evaluate the results by making improvement adjustments. For this, the prototype is introduced to the user, and feedback is requested on how suitable the product/service is, and areas for improvement are identified. User feedback encompasses an iterative process that continues until the prototype is transformed into the expected final product.

The double diamond model is particularly used in business and marketing (Design Council, 2024; Norman, 2013). The model presents four main stages (discover, define, develop, deliver) on two adjacent diamonds. According to the model, correctly identifying a problem and determining the right solution are equally important, and as indicated by the arrows in the figure, it is not a linear process. Another model is the DEEP Design Thinking model proposed by Mary Cantwell in 2010 (Cantwell, 2024). The DEEP Design Thinking model takes its name from the steps of the model; discover, empathize, experiment, and produce.

In this study, the model developed by Stanford University’s d.school, which has been widely accepted in online project-based design thinking education, was utilized. The main reason for choosing this model is that it is used extensively in the educational sciences literature (Alhamdani, 2016; Benson and Dresdow, 2015; Girgin, 2019; Häger and Uflacker, 2016; Henriksen et al. 2020; Pande and Bharathi, 2020; Rauth et al. 2010; Yang and Hsu, 2020).

Design thinking tools

A wide variety of design thinking tools are used in the design thinking process. Design thinking works functionally when the tools and methods used are compatible with the way of thinking (Brenner et al. 2016). Whichever model is used, the important thing is to choose the most suitable tool during the relevant step. Moreover, in one-on-one interviews with design teachers about the essence of design thinking, Rauth et al. (2010) encountered teachers who described design thinking as a toolbox.

Design thinking offers a new perspective on problem-solving, accompanied by a toolkit that facilitates its practical application. The toolkit provides instructions to the practitioner for exploring design thinking (Design Thinking for Educators, 2021; Dolata and Schwabe, 2016; Sürmelioğlu and Seferoğlu, 2023). Some of the design thinking tools mentioned in the literature include empathy maps, journey maps or user journey maps, mind maps, affinity diagrams, effort-impact matrix, brainstorming, reverse brainstorming, comparison techniques, idea innovation axes, prioritization, experience scenario maps, and storytelling.

Gaining design thinking skills

Pande and Bharathi (2020) detailed the design thinking experiences by combining them with a constructivist learning approach in a fundamental design course at a business school in higher education and revealed that there is a close relationship between constructivist principles and each activity within the process.

Due to its compatibility with the nature of design thinking, the constructivist learning theory is the basis for the instruction of design thinking (Assaf, 2009; Pande and Bharathi, 2020). The constructivist teaching approach includes a design that supports the learners to create their meaning by activating the learner’s positions within the interaction of teaching (Erdem, 2020). In cases where a constructivist learning perspective and a collaborative, creative process are involved, project-based learning methods that allow for design development, imagination, planning, and construction in the process in a learner-centered manner have gained prominence.

At the point of what the project is to be put forward in the project-based learning process is about, animation technology has been envisioned as an option that can be produced through design thinking. Today, teachers can create, develop, use, and share their instructional technologies. It can be stated that teachers’ ability to perform these functions is closely related to their design thinking skills. Therefore, in the technology dimension of this study, animation technology, whose importance is increasing day by day and which is known to contribute to learning, has been used. In the literature, the use of animation at different levels has been found to facilitate learning (Höffler and Leutner, 2007), increase class participation (Ertuğrul-Akyol et al. 2017), appeal to the learner (Edsall and Wentz, 2007), make learning permanent (Efe, 2015), combine complex systems (Yang et al. 2003), make abstract concepts more concrete (Burke et al. 1998), and facilitate the mental visualization of events and phenomena (Betrancourt, 2005). In addition, animation technology should be supported by scenario writing. In the process of instructional scenario writing, scientific language needs to be transformed into everyday language. During this transformation, it was envisaged that the teacher’s design thinking ability is an important skill. Within the scope of the study, learning practices based on scenario writing, story card drawing, and animation were included in the process of teaching design thinking skills.

This study is an exemplary study for the development of teachers’ design thinking skills with a collaborative practice module, together with an interdisciplinary theoretical study. In the globalized world, the importance of individuals having a multidimensional perspective on situations is emphasized, making it additionally important for this study to be conducted in an interdisciplinary manner. This study was carried out, on its own scale, to address the issue of the lack of design thinking, which is one of the problems in question, and to develop solutions and recommendations for it.

Aim and objectives of the study

This study aimed to design an online, collaborative, project-based environment and process based on constructivist learning to enhance teachers’ design thinking skills and to test the effectiveness of the application. The skill of design thinking has been attempted to be developed through processes based on scenario writing and digital animation design, to allow participating teachers to transfer the skills they have acquired in the process to their own teaching processes and thus create sustainable and effective teaching technology. In contrast to a purely technical, single-disciplinary, and solution-focused approach to problem-solving, design thinking emphasizes a holistic perspective by leveraging strategies and interdisciplinary teams (Brown, 2008; Dosi et al. 2018; Häger and Uflacker, 2016; Schoormann et al. 2023; Sürmelioğlu, 2021). Due to the inherently interdisciplinary nature of design thinking, this study was carried out with a participant group consisting of history, geography, and social studies teachers and heterogeneous teams.

Within the scope of the study, the following were targeted:

-

While examining the effect of online project-based design thinking teaching on teachers’ design thinking level, to determine the significance between branches, within branches, between teams, and within teams,

-

To determine the quality of the team products developed in the online project-based design thinking teaching process according to the type of self, peer, and instructive evaluation,

-

To determine the first impressions of the teachers who participated in the online project-based design thinking teaching process and their satisfaction throughout the process,

-

To determine the views of teachers on the professional contribution of the online project-based design thinking teaching process

Method

In the study, a mixed research method was used, which allows quantitative and qualitative research methods to be used together. Following Creswell’s (2014) categorization of mixed methods, the study was designed with embedded design mixed methods research.

Study group

The study group consists of 7 history teachers, 7 geography teachers, and 8 social studies teachers who voluntarily participated in the study during the summer semester of the 2019–2020 academic year, in line with the purpose of the study.

While the information and opinions of the participants were analyzed and presented, in accordance with ethical principles, each participant was assigned a code, and the participants were referred to by these codes throughout the study. The letter “T” used at the beginning of the code represents the team, the number that follows it indicates which team it is, and the third letter from the left represents the branch (“H” stands for history, “G” stands for geography, and “S” stands for social studies). The number after this letter indicates the number of people belonging to that branch in the relevant team. For example, the code “T3G2” means that the participant is the geography teacher in Team 3 and the second geography teacher on that team. Details are presented in Table 2.

Teams were formed with at least one teacher from each of the history, geography, and social studies branches in each team. It was ensured that there was at least one male and one female participant in each team. In addition, while forming the teams, at least one graduate participant was placed in each team, taking into account the level of graduate education.

Data collection

Quantitative data were collected using scales at the beginning and end of the implementation, and qualitative data were collected at the beginning, during the implementation, and at the end of the process.

In this study were used as data collection tools, design thinking scale, material development guide evaluation scale, satisfaction form, study logbook, video recordings, web portal forum records and a semi-structured interview were used as data collection tools in the study. The Design Thinking Scale is a 25-item scale consisting of relationship, process, ethics, and individual sub-dimensions (Sürmelioğlu and Erdem, 2021). The Design Thinking Scale was developed to assess individuals’ self-efficacy in design thinking skills. Six-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 125. Higher scores reflect a greater tendency toward design thinking. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (internal consistency reliability) of the scale was calculated to be 0.93.

The Material Development Guide Evaluation Scale was developed by Erdem (2009) to evaluate teaching materials. The Material Development Guide Evaluation Scale is a 36-item scale comprising of the sub-dimensions of scope adequacy, scientificity, organization, and originality. The scale produces scores ranging from 0 to 108 and does not contain any reverse-scored items. Higher scores reflect the adequacy of the material in these dimensions. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (internal consistency reliability) of the scale was calculated to be 0.97.

Other data collection tools were developed by the researchers within the scope of this research. The satisfaction form was developed to determine the satisfaction of the participants in their first session. The aim of the study logbook is to enable participants to evaluate their day at the end of each session. Teachers were asked to score (out of 10) what they did, thought, felt and enjoyed during the session through the study logbook. Video recordings were taken with the permission of the participants. These records aim to monitor the process management of the participants during the implementation process, confirm the validity of the research data, and prevent data loss. Web portal forum records are records created by the system about what participants do in the environment, such as opening topics, commenting, creating surveys, adding friends, writing private messages, from the time they log in to the learning environment until they log out. The aim of the semi-structured interview form is to reveal teachers’ thoughts about the process. The extent to which the training met the expectations of the participants, their contributions, their reflections on instructional designs, what they might suggest to their colleagues, and their suggestions were questioned.

The necessary permissions for the planned data collection process were secured through the Ethics Committee Approval from Hacettepe University and the decision of the Board of Directors of Sinop University regarding the feasibility of the course. The data collection process of the study was conducted as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Data analysis

Since the study was planned with a mixed method, both quantitative and qualitative data were studied. Therefore, different analysis methods were used in the analysis of the study data. Since the study group consisted of 22 participants, non-parametric methods were used in quantitative data analysis, while content analysis was used in qualitative data analysis.

In terms of the validity and reliability of the study, long-term participation and continuous observation, data triangulation, direct reporting of sample participant expressions, rich and intensive descriptions, detailed descriptions of participants and the context, as well as a detailed explanation of the data collection process, data analysis, and the study’s design have been provided. During the observations made by the researcher, field notes were kept, the study logbook was filled in by the participants in writing, and records were taken with the approval of the participants during the interviews. The recordings of the interviews were transcribed into written texts. The data obtained were analyzed by a field expert as well as the researcher, and a consensus was reached among the coders.

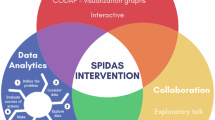

Environment and process design

Each stage of the study was carried out online. To initiate and maintain communication with the participants, an email account and social media accounts were created, and a web portal was established. Various features were added to the web portal, including the ability for participants to express themselves, like topics, subscribe to topics, comment, tag, create surveys, and share files, to encourage interaction and promote design thinking (Fig. 3).

The first examples of the products aimed to be developed by teachers in the process were developed by researchers. These examples include scenario text, story card drawing, and digital animation, developed after the empathy study, definition, and ideation process. Design thinking stages were applied for subject-specific scenario writing specific to the branches within the scope of the study. Following the collection of opinions from a group of teachers, the empathy study data was analyzed and identified, and through ideation, a decision was made to prepare a scenario that delves into the historical, cultural, and geographical aspects of the opening of the Turkish Grand National Assembly on April 23, 1920. In the scenario, the lesson took place remotely online, and by integrating design thinking steps in the teaching, a flow was designed depicting students’ creation of instructional technologies with project-based collaborative teams under the guidance of the teacher. Some screenshots of online presentations and applications are presented in Fig. 4.

A pilot study was conducted before the implementation process (Sürmelioğlu and Erdem, 2024; Sürmelioğlu, 2021). The implementation process was designed with the data obtained from the pilot study findings. The instructional program covered 12 days, with daily 90-min sessions taking place on weekdays. The first session of the day, lasting 40 min, was planned for the instructor’s theoretical knowledge sharing and presentation of sample applications, and this session was described as the study in a large group setting. The second session, lasting 50 min, was designed as the time for teams to work, and this session was labeled as the study in a small group setting. In these types of sessions, the instructor and the participants had different tasks. In each session, the processes of the design thinking stages are included.

The theoretical foundations that form the structure of the designed design thinking teaching environment and process are illustrated in Fig. 5. Within the scope of the study, teachers’ design thinking skills were developed through online project-based design thinking instruction, scenario writing, and digital animation creation processes.

As can be seen in Fig. 5, the designed design thinking teaching was successfully carried out within the scope of the constructivist learning approach, in an online learning environment, in a project-based teaching process, by applying learning practices.

Results and Discussion

Within the scope of the study, an online instructional design based on constructivist learning to improve teachers’ design-oriented thinking skills was developed and its effectiveness was tested in practice. The study was carried out with 6 heterogeneous teams and the teaching process was completed in 12 days, in two sessions of 90 min per day, in a total of 1080 min. This 1080-min online process was designed in the form of large-group and small-group sessions. The total time allocated to large group sessions of this process is 510 min, while the total time allocated to small group sessions is 570 min. The content of the instructional program or learning practices directly affects the duration.

In the study, the design of the instructional process and the work of the teams were carried out by applying the steps of the Stanford University d.school design thinking model (empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test), to help teachers become design thinkers. Throughout the process, design thinker characteristics (Sürmelioğlu and Erdem, 2021) were tried to be activated. In the literature, it is seen that teachings are designed using the d.school model in similar or different forms (Alhamdani, 2016; Benson and Dresdow, 2015; Girgin, 2019; Häger and Uflacker, 2016; Henriksen et al. 2020; Pande and Bharathi, 2020; Rauth et al. 2010; Yang and Hsu, 2020).

Findings on the level of design thinking

The change in the design thinking levels of all teachers before and after the implementation was examined. For this purpose, the Wilcoxon test, a non-parametric method, was used to compare the pre-test and post-test results of the dimensions of the Design Thinking Scale. The findings are presented in Table 3.

The process sub-dimension of the scale represents characteristics of experimentation/risk-taking, creative confidence, holistic perspective, and a dynamic mind, and the individual sub-dimension represents characteristics of innovation/comfort in uncertainty, optimism, critical thinking, and design style, which expresses self-awareness of the person. Statistically significant results were obtained in the process sub-dimension (p = 0.007) and individual sub-dimension (p = 0.022). In this case, the online process has benefited individual awareness. Chesson (2017) introduced the Design Thinker Profile Scale for individuals working in organizations, including dimensions such as personalized solution optimism, visual storytelling, and collaborative exploration. It has been observed that self-awareness is a significant characteristic in the individual’s design-oriented thinking process.

The other two sub-dimensions of the Design Thinking Scale, namely, relationship (human-centered, empathy, reflective, collaborative teamwork) and ethics, encompass an individual’s awareness of their relationship with others. There were no statistically significant changes in the relationship (p = 0.064) and ethics (p = 0.126) sub-dimensions. The lack of significance in the relationship sub-dimension can be explained by the fact that the participants in the study were individuals who did not know each other and met online within the scope of the study. In addition, the fact that the participants were in the occupational group with high social relations (Çelikten et al. 2005) may have limited the change due to the design thinking teaching process. The lack of statistical significance in the ethics sub-dimension is considered important within the scope of the study. No significant difference (p = 0.126) was found between the pre-test median value (4.75) and the post-test median value (5) in the ethics sub-dimension. The answers given to the ethics items of the scale indicate that teachers have a high ethical awareness before the implementation. However, during the process, there were instances where participants did not specify the resources they benefited from and did not explicitly mention their sources of inspiration. This suggested that participants had uncertainties about what was ethical. Despite this, the high scores obtained from the ethics-related items in both the pre-test and post-test indicate that the participants may have been affected by social likability (Erzen et al. 2021; Randall and Fernandes, 1991). The possibility that the influence of socially acceptable and desirable behavior in society could have affected the response to a scale item (Erzen et al. 2021) may have led to the result in the ethics sub-dimension of the design thinking scale.

In the branch-specific examinations, a significant difference was found among social studies teachers in favor of geography teachers in the process sub-dimension of the design thinking scale. Although it was revealed that social studies teachers demonstrated significant changes in the relationship sub-dimension of the design thinking scale and the geography teachers showed significant changes in the process sub-dimension, there was no significant difference between the project teams in terms of design thinking. The individual changes in design thinking levels of teachers did not statistically reflect on the teams. In this case, it can be stated that the process similarly and positively affected all teams, leading to no significant difference among them.

Findings on the quality of products by evaluation type

The effect of the online process on team products was determined by the material development guide evaluation scale. As a result, there was no significant difference between the self-assessments of each individual and the team. Peer and instructor assessments resulted in parallel findings, indicating a difference in the scientific sub-dimension. Significant scientific differences between the teams in which the difference occurred were noted throughout the process. Considering the participant opinions regarding assessment, the cognitive benefits provided by self-assessment (Kösterelioğlu and ve Çelen, 2016; Pala and Erdem, 2018; Şahin and ve Kalyon, 2018) and peer assessment (Şahin and ve Kalyon, 2018; Demiraslan Çevik, 2014; Uçar and Demiraslan Çevik, 2020) for participants who received feedback and those who gave feedback are also observed in the relevant literature.

Three types of evaluation have been made regarding the assessment of the quality of products. These are self-assessments (individual and team self-assessments), peer assessments (individual and team peer assessments), and instructor assessments. Table 4 shows the three types of assessment findings for the materials.

Similarities were observed between the dynamics of the teams in the production process and the dynamics in the evaluation processes. In addition, differences were observed between team assessment and self-assessment in the evaluation processes. In intra-team assessments, three themes have emerged regarding what stands out in more qualified evaluations regarding evaluation through collaborative processes. These themes include the information provided in the content being scientific and consistent, the conveyed information being suitable for the target audience, and the design being original. This finding, as emphasized by Erdem and ve Ekici (2016), can be interpreted as evaluation in collaborative processes transforming from an evaluation based on external criteria that produces comparative data to an evaluation based on internal criteria that produces developmental data.

During the online teaching process, teams have been influenced by various factors. The most significant of these is the ability to use digital technology. The subsequent factors were determined to be the speed of adaptation to the web portal, intra-group conflict, collaboration within the group, communication (messaging on the team forum and online communication), and time management anxiety, respectively. Similarly, Häger and Uflacker (2016) found that design experts, students, and program organizers were greatly influenced by several individuals such as coaches, project partners, competitors, and team members.

During the online process, teams showed two different structures referred to as balanced and extreme based on their working methods and the time they used. Balanced teams completed the planned flow on time at every stage of the process. Extreme teams, on the other hand, either completed their work in a time well below the planned time or used well above the planned time. Lower-extreme teams have experienced anxiety about time management, although they have not exceeded the planned time. It was observed that the primary reason for this is the low skill of the team members in the use of digital technology. The main reason for the upper-extreme team exceeding the time is that the scenario work of the decided idea is done on a ready-made text. This misled them and caused them to do additional work many times. Häger and Uflacker (2016) examined how experts, students, and program organizers at the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design implemented team time management and agreed that time management is necessary. They recommended daily agendas, time counters, and breaks for time management. In their study, designed with a project-based teaching approach with teacher candidates, Dağ and ve Durdu (2011) reported that there were difficulties in time management. Girgin (2019) found that teachers had the most difficulty in empathizing, generating ideas, and time management after design thinking training. Considering these findings and information together with Tsai’s (2021) emphasis that higher-order thinking, interactive collaboration, and time management can be improved with design thinking, time management emerges as both a challenge and a goal for teaching design thinking.

Findings on the effect of the process on satisfaction

Participant satisfaction was measured after the first session of the online process, and it was determined that participant satisfaction was high. In this case, it can be stated that the procedures carried out during the opening, meeting, and introduction process, which is the first event, were very useful. At this stage, the process, purpose, and platforms to be used were explained, the meeting took place, the web portal was subscribed, fun and general culture icebreaker questions were answered in the forum of the portal, and the teachers, who were randomly divided into rooms through the digital platform, were enabled to chat for 10 min in small groups. This situation was also determined by the content analysis conducted on the participants’ opinions on the first activity in the logbook, which was examined to determine the satisfaction of the teachers throughout the process. The satisfaction of the teachers at the beginning of the process also positively affected their satisfaction with the subsequent activities.

To discover how the implementation process leads to a change in teachers and teachers’ satisfaction with the process, logbook comments kept by teachers were examined. Teachers’ statements about what they do, think, and feel about each activity of the online process indicate that they have developed awareness of the requirements of design thinking, and they are very satisfied with the process. Benson and Dresdow (2015) developed a list that captures the essence of students’ actions and behaviors associated with reflective diary and design thinking in the process of teaching design thinking. These are clustered into five categories, consistent with the design thinker attitude: empathy, integrative thinking, optimism, experimentation, and collaboration. In their study, Akkoyunlu et al. (2016) enabled pre-service teachers to keep a reflective diary during the teaching practice course. At the end of the process, participants stated that they had the opportunity to evaluate themselves holistically, monitor their development, gain a critical perspective, and develop a sense of responsibility and writing skills thanks to the diaries, and it was revealed that reflective diaries contributed to the personal and professional development of the participants. Henriksen et al. (2020) stated that there is a need to understand how design thinking can be applied in teacher education, and questioned what teachers understand from learning and using design thinking and found three main themes. These are valuing empathy, being open to ambiguity, and considering teaching as design. As a result, the categories obtained for each activity within the scope of this study are supported by the literature.

Teachers’ views on the teaching process

After the online teaching process, the opinions of the teachers were taken regarding five themes. The first of these themes is teachers’ process-related gains. Gains are clustered into five categories: Design thinker characteristics, design thinking teaching process, animation directing, professional development, and digital technology skills. Girgin (2019) asked why teachers wanted to participate in design thinking training and determined the categories of the responses as a contribution to professional development, and curiosity, interest, and desire for the design process. Teachers’ professional development is crucial to improving student outcomes (Sancar et al. 2021). In addition, Benson and Dresdow (2015) developed products (visual software, graphic design, and 3D models) in the process of developing their students’ design thinking skills in the undergraduate course they designed with the project-based teaching method, and carried out all studies in a digital environment. In the process, students were required to take time to learn how to use digital technology, and the development of their other digital skills (e-mail, learning management system, and virtual classroom use) was supported. The results of the literature and the contributions of the study to the design thinking teaching process were parallel.

Secondly, the contributions of the online process to teachers’ instructional designs were questioned, and the responses were clustered in three categories. These categories are design thinking contributions, animation contributions, and project ideas.

Thirdly, the possible contributions of the online process to subsequent instructional design and technology creation situations were asked, and the findings were clustered into two categories. The first category is individual development (increase in self-confidence towards the use of digital technology, increase in digital technology knowledge, awareness of animation software), and the second is methodological development (roadmap, idea of producing own animation, product release effect with the team). In this regard, digital animation teaching was also carried out in the online process, and evidence was found that teaching was beneficial. It was concluded that teachers have the competence to produce animations individually or together with their students in the next teaching process. In the study of Rauth et al. (2010), it was found that competencies such as prototyping, adopting different perspectives, and empathy developed in individuals after teaching design thinking, and this resulted in confidence in creativity in the participants.

Fourthly, it was questioned whether the branch (history, geography, social studies) teachers who participated in the online process needed this kind of training, and it was determined that they needed such training. When the reasons for these needs were questioned, codes such as the need to embody abstract subjects, the need for visuality, the need for design thinking, the need to design one’s own material, and not being taught in the faculty of education emerged. These results highlighted the need and benefits of both design thinking and animation learning.

In the fifth theme, it was asked what the participants’ suggestions would be to researchers for the teaching process if the teaching process were to be replanned. Two categories have been created regarding these suggestions. These are the teaching process and the entire process. The contents of these categories are as follows:

-

Teaching process:

-

Increased mentor participation

-

Extension of the creation process

-

Teaching two animation software as electives

-

Determination of gains after the ideate phase

-

Including a literature teacher to the teams

-

The entire process:

-

Rescheduling this training

-

Expansion to other branches

-

Face-to-face training of the same

-

Previous participants mentoring the teams

-

The same participants attend this training for the second time

In the online project-based design thinking teaching process, rich scenario writing, story card drawing, and animation design were taught as learning practices, and all practices were carried out by all teams. In the online project-based design thinking teaching process, the development of products to be produced was supported.

Conclusion and recommendations

In the online project-based design thinking teaching, rich scenario writing, story card drawing, and animation design were taught as learning practices, and all practices were carried out by all teams. In the online project-based design thinking teaching process, the development of products to be produced was supported. It can be argued that the online design thinking teaching process offers significant advantages by providing more space for diverse voices to be heard and emphasizing the centrality of people (Zeivots et al. 2021).

Individuals may not always be aware of their problem-solving thought processes. Therefore, regardless of the specific thinking skill targeted in thinking instruction, initiating awareness of the thinking process is important (Assaf, 2009; Sayın, 2020). Design thinking skill is a collaborative design process that focuses on the target audience (Chesson, 2017; Schoormann et al. 2023). Activities related to the design process should be used in teaching design thinking. These activities support participants to analyze their thinking processes and raising awareness. In addition, design thinking is not a skill set that develops spontaneously, regardless of the work carried out in the teaching process. Therefore, it needs to be developed with special-purpose activities and technical tools.

According to the study results, it can be stated that the online learning environment designed to improve teachers’ design thinking skills leads to positive changes in teachers’ design thinking skills. It was observed that the environment and process have the potential to produce effective results. The designed design thinking teaching was successfully carried out within the scope of the constructivist learning approach, in an online learning environment, in a project-based teaching process, by applying learning practices. It is considered that a path has been opened for participating teachers to create sustainable and effective instructional design and technology by carrying the skills they have gained into their own teaching processes.

Within the framework of the study results, recommendations to future researchers:

-

A similar online project-based design thinking instruction, adapted to current dynamics, is recommended to be conducted both online and in face-to-face settings.

-

In online project-based design thinking teaching, teams have been influenced by a variety of dynamics. Therefore, to support the process to be more efficient in future studies, the digital technology usage skills of the participating teachers can be determined before the implementation, and the participants can be distributed to the teams according to this variable.

-

It is recommended that future studies be conducted with participants from similar and different branches. It may also be recommended to transfer this process to different branches or to study with a limitatio,n such as only administrator teachers.

-

To support teachers in integrating project-based design thinking into their instructional designs, it is recommended to develop an implementation guide booklet and provide in-service training.

-

Although there was at least one history, one geography and one social studies teacher in the project teams of this study, there were inconsistencies in ideas, concepts and knowledge deficiencies in the scenarios and this situation was not noticed within the team, and various deficiencies or errors were noticed and criticized by other team teachers during the team evaluations. Since the products obtained in the process are learning materials, it is expected that the material has been refined to prevent misconceptions. Furthermore, during the testing phase, Prof. Dr. Erdem also participated and provided necessary feedback and suggestions by observing the presentations. Teachers have reported their satisfaction with this situation in both the study logbook and semi-structured interviews. Participants stated that there should be more mentor participation. Therefore, to identify and prevent material deficiencies and inconsistencies in future studies and to provide support and different perspectives to the participants, mentor support and more frequent participation from related field experts are recommended.

The data for this study are limited to the information obtained from history, geography, and social studies teachers who voluntarily participated in the research. The study aimed to develop design thinking skills, scenario writing, and animation creation through structured processes in an online environment during the summer term of 2019–2020. Therefore, the study’s data are limited to this time frame and the specified data collection methods.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Akkoyunlu B, Telli E, Çetin NM, Dağhan G (2016) Öğretmen eğitiminde yansıtıcı günlüklere ilişkin öğretmen adaylarının görüşleri. Turk Online J Qualit Inq 7(4):312–330

Alhamdani WA (2016) Teaching cryptography using design thinking approach. J Appl Secur Res 11(1):78–89

Assaf MA (2009) Teaching and thinking: a literature review of the teaching of thinking skills. Online Submission

Baraji RF, Siang TY (2025) What is design thinking and why is it so popular? Retrieved 22.02.2025 from https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/what-is-design-thinking-and-why-is-it-so-popular

Benson J, Dresdow S (2015) Design for thinking: engagement in an innovation project. Decis Sci J Innov Educ 13(3):377–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12069

Betrancourt M (2005) The animation and interactivity principles in multimedia learning. In R Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 287–296). New York: Cambridge University Press

Brenner W, Uebernickel F, Abrell, T (2016) Design thinking as mindset, process, and toolbox. In Design thinking for innovation (pp. 3-21). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26100-3_1

Brown T (2008) Design thinking. Harv Bus Rev 86(6):84–92

Buchanan R (1992) Wicked problems in design thinking. Des issues 8(2):5–21

Burke KA, Greenbowe TJ, Windschitl MA (1998) Developing and using conceptual computer animations for chemistry instruction. J Chem Educ 75(12):1658. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed075p1658

Cantwell M (2024) DEEP design thinking. Retrieved 22.07.2024 from https://www.deepdesignthinking.com/

Çelikten M, Şanal M, ve Yeni Y (2005) Öğretmenlik mesleği ve özellikleri. Erciyes Üniv Sos Bilimler Enst ü Derg 1(19):207–237

Chesson D (2017) Design Thinker Profile: Creating and Validating a Scale for Measuring Design Thinking Capabilities. (Doctoral dissertation). Antioch University, Kaliforniya, ABD

Creswell JW (2014) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Dağ F, ve Durdu L (2011) Öğretmen adaylarının proje tabanlı öğrenme sürecine yönelik görüşleri. Educ Sci 7(1):200–211

Demiraslan Çevik Y (2014) Dönüt alan mı memnun veren mi? Çevrimiçi akran dönütü ile ilgili öğrenci görüşleri. J Instruct Technol Teach Educ, 3(1)

Design Council (2024) What is the framework for innovation? Retrieved 22.04.2024 from https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/framework-for-innovation/

Design Thinking for Educators, (2021) Retrieved 01.01.2021 from http://www.design.thinking.for.educators.com/

Dolata M, Schwabe G (2016) Design thinking in IS research projects. In Design thinking for innovation (pp. 67–83). Springer, Cham

Doppelt Y (2009) Assessing creative thinking in design-based learning. Int J Technol Des Educ 19(1):55–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-006-9008-y

Dorst K (2010) The nature of design thinking. In Design Thinking Research Symposium. DAB Documents

Dosi C, Rosati F, Vignoli M (2018) Measuring design thinking mindset. In DS 92: Proceedings of the DESIGN 2018 15th International Design Conference (pp. 1991-2002). https://doi.org/10.21278/idc.2018.0493

Edsall R, Wentz E (2007) Comparing strategies for presenting concepts in introductory undergraduate geography: Physical models vs. computer visualization. J Geogr High Educ 31(3):427–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260701513993

Efe HA (2015) Animasyon destekli çevre eğitiminin akademik başarıya, akılda kalıcılığa ve çevreye yönelik tutuma etkisi. J Comput Educ Res 3(5):130–143. https://doi.org/10.18009/jcer.90852

Erdem M (2009) Effects of learning style profile of team on quality of materials developed in collaborative learning processes. Act Learn High Educ 10(2):154–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787409104902

Erdem M (2020) Yeniden öğretmeyi öğrenmek: Organizmadan bireye öğretim süreçleri tasarımı. Pegem Akademi, Ankara

Erdem M ve Ekici, M (2016) Yapılandırmacı değerlendirme ve çevrimiçi öğrenme ortamları. A İşman, HF, Odabaşı, B Akkoyunlu (Ed.) Eğitim Teknolojileri Okumaları 2016. (32. Bölüm, s. 575-592). Turk Online J Educ Tech, Ankara

Ertuğrul-Akyol B, Kahyaoğlu H, ve, Köksal EA (2017) Ortaokul Fen ve Teknoloji Dersinde Müzikli Fen Animasyonu Kullanımı Hakkında Öğretmen Görüşleri. Int J Act Learn 2(1):22–37

Erzen E, Yurtçu M, Ulu Kalın Ö, Koçoğlu E (2021) Sosyal beğenirlik ölçeği’nin geliştirilmesi: geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalişması. Elektro Sos Bilimler Derg 20(78):879–891. https://doi.org/10.17755/esosder.774947

Friedman K (2003) Theory construction in design research: criteria, approaches, and methods. Des Stud 24(6):507–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(03)00039-5

Girgin D (2019) 21. yüzyılın öğrenme deneyimi: öğretmenlerin tasarım odaklı düşünme eğitimine ilişkin görüşleri. Milli Eğitim Derg 49(226):53–91

Guaman-Quintanilla S, Everaert P, Chiluiza K, Valcke M (2023) Impact of design thinking in higher education: A multi-actor perspective on problem solving and creativity. Int J Technol Des Educ 33:217–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-021-09724-z

Häger F, Uflacker M (2016) Time management practice in educational design thinking projects. DS 85-2: Proceedings of Nord Design 2016, Volume 2, Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th August 2016, 319–328

Henriksen D, Gretter S, Richardson C (2020) Design thinking and the practicing teacher: addressing problems of practice in teacher education. Teach Educ 31(2):209–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2018.1531841

Höffler TN, Leutner D (2007) Instructional animation versus static pictures: A meta-analysis. Learn Instr 17(6):722–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.013

Irbīte A, Strode A (2016) Design thinking models in design research and education. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. Volume IV (Vol. 488, p. 500). https://doi.org/10.17770/sie2016vol4.1584

Kolko J (2015) Design thinking comes of age. Harv Bus Rev 93(9):66–71

Kösterelioğlu İ, ve Çelen Ü (2016) Öz Değerlendirme Yönteminin Etkililiğinin Değerlendirilmesi. Elem Educ Online 15(2):671–681. https://doi.org/10.17051/io.2016.44304

Kröper M, Fay D, Lindberg T, Meinel C (2011) Interrelations between Motivation, Creativity and Emotions in Design Thinking Processes – An Empirical Study Based on Regulatory Focus Theory. In: Taura, T, Nagai, Y (eds) Design Creativity 2010. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-85729-224-7_14

Liedtka J (2015) Perspective: Linking design thinking within novation outcomes through cognitive bias reduction. J Prod Innov Manag 32(6):925–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12163

Liedtka J (2018) Exploring the impact of design thinking in action. Darden Working Paper Series

Lynch M, Kamovich U, Longva K, Steinert M (2021) Combining technology and entrepreneurial education through design thinking: Students’ reflections on the learning process. Technol Forecast Soc Change 164:119689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.06.015

Morrison GR, Ross,SM, Kemp JE (2012) Etkili öğretim tasarımı. İstanbul: Bahçeşehir Üniversitesi Yayınları

Norman D (2013) The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition. ABD: Basic Books

Owen C (2007) Design thinking: Notes on its nature and use. Des Res Q 2(1):16–27

Özaydınlık K (2024) Online Design Thinking Instruction and changes in pre-service teachers’ self-perceptions of Design Thinking and reflective thinking: A mixed-method study. Think Skills Creat 54:101687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2024.101687

Pala F, Erdem, M (2018) Çoklu ortam tabanlı tartışmalarla desteklenmiş bir çevrimiçi öğrenme ortamının geliştirilmesi. B Akkoyunlu, A İşman & HF Odabaşı, (Ed.), Eğitim Teknolojileri Okumaları 2018 (13. Bölüm s. 203–219). Turk Online J Educ Technol, Ankara

Pande M, Bharathi SV (2020) Theoretical foundations of design thinking– A constructivism learning approach to design thinking. Think Skills Creat 36:100637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100637

Randall DM, Fernandes MF (1991) The social desirability response bias in ethics research. J Bus Ethics 10:805–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00383696

Rauth I, Köppen E, Jobst B, Meinel C (2010) Design thinking: an educational model towards creative confidence. In DS 66-2: Proceedings of the 1st. İnternational conference on design creativity (ICDC 2010)

Reigeluth CM (1999) What is instructional-design theory and how is it changing. Instruct-Des Theories Models: A N. Paradig Instruct Theory 2:5–29

Şahin MG, ve Kalyon DŞ (2018) Öğretmen adaylarının öz-akran-öğretmen değerlendirmesine ilişkin görüşlerinin incelenmesi. Kastamonu Eğitim Derg 26(4):1055–1068. https://doi.org/10.24106/kefdergi.393278

Sancar R, Atal D, Deryakulu D (2021) A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103305

Sayın, Z (2020) Öğretmenler için bilgi işlemsel düşünmeye özelleşmiş bir çevrimiçi öğrenme ortamının tasarımı. Yayınlanmamıs¸ Doktora Tezi, Hacettepe Üniversitesi

Scheer A, Noweski C, Meinel C (2012) Transforming constructivist learning into action: Design thinking in education. Des Technol Educ: Int J, 17(3)

Schoormann T, Stadtl¨ander M, Knackstedt R (2023) Act and reflect: Integrating reflection into design thinking. J Manag Inf Syst 40(1):7–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2023.2172773

Stanford Üniversitesi Hasso Plattner Institute of Design. (2010) An Introduction To Design Thinking Process. Retrieved 22.02.2025 from Guide. https://web.stanford.edu/~mshanks/MichaelShanks/files/509554.pdf

Sürmelioğlu Y, Erdem M (2021) Öğretimde tasarım odaklı düşünme ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi. OPUS–Uluslar Toplum Araştırmaları Derg 18(39):223–254. https://doi.org/10.26466/opus.833362

Sürmelioğlu Y, Erdem M (2024) Tasarım odaklı düşünme üzerine öğretim tasarımı örneği. 17th International Computer and Instructional Technologies Symposium, (pp 481–510). https://icits2024.kastamonu.edu.tr/tr/icits-2024-tam-metin-kitabi-yayinlanmistir/

Sürmelioğlu Y (2021) Tasarım odaklı düşünmenin gelişimi için çevrimiçi proje tabanlı bir öğretimin tasarımı ve etkililiğinin incelenmesi. (Yayınlanmamıs¸ Doktora Tezi), Hacettepe Üniversitesi

Sürmelioğlu Y, Seferoğlu SS (2023) Eğitimde Tasarım Odaklı Düşünme ve 21. Yüzyıl Becerileri: Dijital Okuryazarlık Becerileri, Eğitimde Tasarım Odaklı Düşünme Yaklaşımı ve Uygulama Örnekleri, (pp. 151-172), D, Girdin, Z, Toker, Nobel Yayıncılık, Türkiye

The Interaction Design Foundation (2024) 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process. Retrieved 22.07.2024 from https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/5-stages-in-the-design-thinking-process

Thuan NH, Antunes P (2024) A conceptual model for educating design thinking dispositions. Int J Technol Des Educ, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-024-09881-x

Tsai CC, Chai CS (2012) The” third”-order barrier for technology-integration instruction: Implications for teacher education. Australas J Educ Technol, 28(6). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.810

Tsai M (2021) Exploration of Students’ Integrative Skills Developed in The Design Thinking of a Psychology Course. Think Skills Creativity. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100893

Uçar B, Demiraslan Çevik Y (2020) The effect of argument mapping supported with peer feedback on pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills. J Digit Learn Teach Educ 37(1):6–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2020.1815107

Vanada D (2013) Practically Creative: The Role of Design Thinking as an Improved Paradigm for 21st Century Art Education. Learn X Design Conference Series

Yang CM, Hsu TF (2020) Integrating design thinking into a packaging design course to improve students’ creative self-efficacy and flow experience. Sustainability 12(15):5929. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155929

Yang EM, Andre T, Greenbowe TJ, Tibell L (2003) Spatial ability and the impact of visualization/animation on learning electrochemistry. Int J Sci Educ 25(3):329–349

Yeung WL, Ng OL (2023) Using empathy maps to support design-thinking enhanced transdisciplinary STEM innovation in K-12 setting. Int J Technol Des Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-023-09861-7

Zeivots S, Vallis C, Raffaele C, Luca EJ (2021) Approaching design thinking online: Critical reflections in higher education. Issues Educ Res 31(4):1351–1366

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all constructive comments from reviewers. We also would like to thank the research participants who generously agreed to participate in this study and share their time and experience.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We declare that each of us made a significant contribution to conducting this work. This study is adapted from Yeşim Sürmelioğlu, doctoral dissertation at the Hacettepe University, Ankara. Yeşim Sürmelioğlu drafted the design and work. Mukaddes Erdem revised the work. All authors were involved in analyzing and interpreting the data for the paper. Yeşim Sürmelioğlu and Mukaddes Erdem reviewed and proofread the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of University Hacettepe (Date: 23.03.2020 /No: 51944218-300/00001064102).

Informed consent

All participants provided oral informed consent prior to participation. Written consent was waived due to the following reasons: (1) The research was conducted online; (2) Sensitive personal data was not collected in the study. Participants’ responses were anonymized, and no identifiable information was linked to their task outputs. The consent process was conducted via online dialog between experimenters and participants on July 10, 2020. Audio recordings of consent dialogs were made for participants. All data were anonymized and stored on an encrypted server accessible only to the research team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sürmelioğlu, Y., Erdem, M. Design, implementation, and evaluation of an online instructional process to enhance teachers’ design thinking skills. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 820 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05131-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05131-0