Abstract

Achieving sustainable and long-lasting ecological conservation incentives necessitates incorporating the intrinsic motivations of farmers into policy design frameworks. Currently, existing payments for ecosystem services (PES) projects overly focus on monetary incentives, particularly in Chinese projects that primarily revolve around payment standards and place little emphasis on payment design. In this study, a multi-factor mixed field experiment was conducted in Napo County, Southwest China, based on the three dimensions of the bystander effect: diffusion of responsibility (population size), evaluation apprehension (disclosure or non-disclosure), and pluralistic ignorance (emergency level). The key factors that motivate farmers’ sense of responsibility for ecological protection were analysed, showing that: (1) a high emergency level plays a significant role in stimulating farmers’ awareness for ecological protection; (2) the influence of disclosure is significant in smaller areas but weakens with increasing area; (3) faced with the long-term, collective responsibility event of ecological protection, population size does not trigger the bystander effect in ecological protection; (4) most interestingly, patriotism has extreme application potential in ecological protection. This study explores the non-economic factors that encourage ecological stewardship among farmers and applies new approaches to field experiments in payments for ecosystem services, with a specific focus on developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intrinsic motivation provided by the environmental behaviour of farmers cannot be ignored. How the farmers’ sense of ecological protection responsibility can be awakened through non-monetary incentive policy design is an important matter, and the use of non-monetary incentives is a cost-effective and long-lasting approach (Dayer et al. 2018). In 2021, the United Nations Environment Programme and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations proposed an ambitious initiative. They announced the implementation of the United Nations Decade of Ecosystem Restoration program (United Nation Environment Program 2021). The aims of this initiative are to mobilise local communities, indigenous groups, private companies, and governments to participate in a global movement towards ecosystem recovery. Without a doubt, protecting existing forests and cleaning up rivers and farmland requires the participation of nearly 3.4 billion farmers, who account for 43% of the world’s population (World Bank 2022).

In recent decades, the widespread adoption of payments for ecosystem services (PES) has emerged as a crucial strategy to enhance ecosystem services and ensure sustainable development on a global scale (Kumar et al. 2014; Yan et al. 2022). With a global presence of more than 550 active programs and an estimated annual transaction volume of US$36–42 billion (Salzman et al. 2018), many countries have provided economic incentives to reward farmers’ pro-ecological behaviours through PES projects, which have achieved clear results (Frey et al. 2021; Sgroi et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2022). However, because of the complexity of the management system (Fauzi and Anna 2013), weak supervision (Jayachandran 2013; Oliveira Fiorini et al. 2020), and low intention to participate (Kosoy et al. 2008), several PES did not achieve the aspired goals. A more thorough study of the design of PES through revisiting the PES procedure has become crucial to better achieve the desired goals (Yan et al. 2022).

China is home to a substantial number of PES programs, known for their considerable size (Li et al. 2023; Salzman et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2020). In the early 21th century, the increasingly prosperous Chinese government embarked on efforts to improve the ecological environment and started to initiate several PES programs (Liu et al. 2008; Pan et al. 2017). Currently, the Chinese government has implemented a range of PES program designs in the domains of agriculture, forestry, and animal husbandry, which have achieved notable progress. Several exemplary PES programs have been implemented in China. One of them is the Grain to Green Program, also known as the Sloping Land Conversion Program, or the Farm to Forest Program. This program is considered the world’s largest ecological restoration program (Liu et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2019) and includes four restoration modes: farmland afforestation, the establishment of fruit tree plantations, afforestation of degraded land, and natural forest conservation (Xian et al. 2020). Another notable program is the Three-North Shelter Forest Program, also called the Green Great Wall program. This is the largest afforestation program globally, with a planned completion date of 2050 (Cao et al. 2020; Suo and Cao 2021; Zhai et al. 2023). The program spans three stages and eight phases, covering 725 counties and 13 provinces of China, costing a total of CNY 93.3 billion (Chu et al. 2019; Zhai et al. 2023). The Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy is another important PES program in China. It is the largest grassland conservation program globally, to which the Chinese government has allocated a substantial investment of CNY 7.7 billion. A sizeable portion of this funding is directly disbursed to herders as compensation for reducing grazing intensity or ceasing grazing activities altogether (Hou et al. 2021; Hu et al. 2019).

However, monetary incentives have received considerable criticism, and scholars have constantly proved that external incentives only achieve short-term environmental protection (Brown et al. 2021; Ravikumar et al. 2023; Rode et al. 2015). In particular, once economic incentives stop, environmental protection efforts will suddenly degenerate or even stop entirely. Internal motivations are replaced by monetary incentives, thus, carrying the risk of “crowding out” moral responsibility (Srivastava et al. 2001). Despite the concern that such economic incentives may backfire, how non-monetary incentives can successfully stimulate farmers’ sense of responsibility for ecological protection remains unknown. Also, the factors that can effectively stimulate farmers’ sense of responsibility for ecological protection remain largely unknown. Answering these questions accurately carries great importance for improving the ecological and environmental quality and achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Clark and Wu 2016) as well as the goals of the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (Abhilash 2021).

While protective behaviour may diminish when monetary incentives are discontinued, existing ecological protection policies tend to stimulate farmers’ responsibility for ecological protection through monetary incentives (Pan et al. 2017; Yin et al. 2013). There are several noteworthy gaps in the current empirical research on ecological protection policy design. First, in China, most designs focus on economic factors, and often overlook the internal motivation of farmers participating in ecological protection efforts. Second, experimental evidence for farmers ramains limited, even though they are the primary group responsible for ecological protection in developing countries. Moreover, the strength of the effects of these factors still needs to be measured.

In this study, the key elements that motivate a sense of responsibility for ecological protection in farmers were analysed. A multi-factor field experiment was designed based on the bystander effect, also known as diffusion of responsibility. The term of the bystander effect implies that in an emergency, bystanders often assume that others will act, thereby dispersing the responsibility to others without acting out of their own initiative (Fischer et al. 2011). Field experiments require a high level of representativeness of the experimental environment (List 2007). Napo County is located in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. The reason why this county was chosen for field experiments is that it represents an ecologically vulnerable area with limited external interventions. This makes it an ideal setting to examine the impact of research interventions on the ecological environment. Additionally, its geographical location and diversity of ethnic communities offer an enriching context for exploring intervention effects.

This study tests hypotheses on the intrinsic motivation of farmers’ ecological protection responsibility by integrating the bystander effect theory. Through a field experiment, conducted on farmers in ecologically fragile areas, the impact of non-monetary motivational factors on promoting farmers’ environmental behaviour was examined. The findings provide empirical support for optimising the design of PES projects in practice.

The key findings of this study: (1) theoretically expand the understanding of the bystander effect in environmental conservation and how it influences ecological preservation; and (2) methodologically expand the field by highlighting the value of field experiments for studies under similar contexts, by choosing an experimental approach tailored for small-scale farmers in developing countries. Our study identified the non-economic factors that encouraged farmers to adopt eco-friendly practices and provided new strategies to promote environmental stewardship without relying solely on financial incentives.

Literature review

Effectiveness and sustainability of PES programs

In China, the terms “eco-compensation” and PES are frequently conflated and have been used interchangeably in numerous research studies (Guihuan et al. 2021; Shang et al. 2018). Most discussions regarding PES programs in China revolve around compensation standards, while less emphasis has been given to studying compensation modalities (Feng et al. 2018). When assessing previous PES initiatives in China, it becomes apparent that similar to PES projects carried out globally, not all endeavours have successfully realised their intended goals (Blundo-Canto et al. 2018; Grima et al. 2016). Moreover, a certain degree of adverse consequences can be observed. Cao et al. (2020) have devised an enhanced methodology for the quantification of costs and benefits; they found that under the Grain to Green Program, out of 25 Chinese provinces, 11 have experienced net losses as a result of substantial cost escalations paired with minimal increments in benefits. Hou et al. (2021) found that although the Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy has achieved modest improvements in grassland quality and significantly positively impacted income, it exacerbated existing income inequality among local community herders.

More and more scholars are focusing on the limitations of monetary incentives and the potential to integrate non-monetary factors in the design of PES programs. Blundo-Canto et al. (2018) assessed 46 evaluated livelihood impacts of PES, finding predominantly positive effects on livelihoods. Nonetheless, they highlighted a substantial gap in the literature, pointing out that the non-monetary and immaterial impacts of ecosystem service fee payment systems remain largely unexplored. Monetary incentives might decrease intrinsic motivation, compromise individual autonomy, or lead to perceptions of distrust, disrespect, and unfair intentions (Bowles 2008). Critics have argued that economically incentivised PES programs may undermine the intrinsic motivation of recipients to engage in environmental conservation behaviours, which is known as the “crowding-out” effect (Agrawal et al. 2015; Chan et al. 2017). This effect could diminish the effectiveness of PES and even exacerbate conservation outcomes after the termination of the project (Ezzine-de-Blas et al. 2019).

The reasonable design and continuity of PES are controversially discussed (Kroeger 2013; Rode 2022; Wunder et al. 2008). Several empirical papers have already pointed out that the motivation of farmers to engage in pro-environmental behaviours in PES projects is weakened to a certain extent. This has led to a sense of frustration among many individuals and a loss of trust in these programs (Brown et al. 2021; Ravikumar et al. 2023; Rode et al. 2015). The existing literature has not reached consensus on whether the intrinsic motivation for conservation in PES projects persists after they are discontinued. Some scholars have empirically observed the existence of crowding-out effects in PES projects (Bose et al. 2019; Maca-Millán et al. 2021; Royal 2021). Moreover, concerns have been expressed over potential consequences arising from the termination or abrupt cessation of these projects (Rode 2022). However, compelling evidence also suggests that PES will not eliminate pro-ecological behaviours entirely (Hayes et al. 2022; Vorlaufer et al. 2023). The present study also provides empirical evidence that adds to this debate from the perspective of the effectiveness of non-monetary incentives.

Social psychology in environmental conservation

The motivation theory of social psychology offers a fresh perspective on understanding farmers’ protection of the ecological environment. Intrinsic motivation refers to engagement in inherently satisfying or enjoyable behaviours, whereas extrinsic motivation refers to behaviours performed for a specific purpose (Legault 2020). Intrinsic motivation is essentially non-instrumental, as individuals do not have a specific goal when engaging in these behaviours. However, extrinsic motivation is essentially instrumental, serving a specific purpose with the aim to achieve certain outcomes. Actions driven by intrinsic motivation tend to have a longer lifespan and greater persistence compared to those driven by external factors (Hidi 2000). Moreover, basing extrinsic motivation solely on economic incentives can undermine farmers’ willingness to reduce their participation in environmentally friendly actions (Meyer et al. 2014). In endeavours to incorporate the intrinsic motivation for ecological protection in explaining farmers’ pro-environmental behaviours, scholars have increasingly acknowledged the importance of intrinsic motivation and non-monetary incentives (Bopp et al. 2019; Greiner et al. 2009; Greiner and Gregg 2011).

Understanding the intrinsic motivations underlying farmers’ ecological conservation behaviours is essential. However, in the implementation process of China’s ecological compensation projects, farmers’ intrinsic motivations have received insufficient attention, and a greater focus has been directed on the amount of economic compensation (Feng et al. 2018). To establish more effective incentive mechanisms, future designs and implementations of ecological compensation projects should place greater emphasis on farmers’ intrinsic motivations and non-monetary incentive factors (Ezzine-de-Blas et al. 2019). Mills et al. (2013) have already identified several intrinsic motivations for environmental protection, such as a personal sense of environmental responsibility and accountability, and personal enjoyment. Based on interviews, Ezzine-de-Blas et al. (2019) concluded that from the perspectives of social recognition and self-recognition, farmers are intrinsically motivated to engage in ecological conservation, which includes factors such as a moral sense, guilt, and social reputation. These intrinsic motivations can substantially influence farmers’ behaviours and environmental management. Extensive research has demonstrated that farmers’ sense of personal responsibility towards the environment is a crucial intrinsic motivation driving their involvement in ecological conservation efforts (Darragh and Emery 2018; Hayes et al. 2022; Mills et al. 2018).

In social psychology, the bystander effect is often used to explain an increase or decrease of the sense of responsibility (Fischer et al. 2011). It provides a theoretical framework for examining the intrinsic motivation of farmers’ ecological conservation from a monetary perspective via experimental design. In a situation where a passive bystander appears in a critical situation, the bystander effect refers to and assesses the possibility that the personal help of this bystander will reduce a certain phenomenon (Hortensius and De Gelder 2018). Often, the bystander effect is used to interpret whether the responsibility individuals assume increases or weakens (Fischer et al. 2011). Previous studies on the bystander effect mostly focused on crime (Banyard et al. 2004; Hollis-Peel et al. 2011; Moriarty 1975) and various forms of bullying (Polanin et al. 2012; Salmivalli 2010); however, this phenomenon has not been widely extended to the environmental and ecological field. There are many similarities between bullying and environmental and ecological fields, such as the existence of a power imbalance, impacts on well-being, and long-lasting effects. Scholars have suggested that bystanders should not be limited to individuals who call for help but also to groups and institutions that ignore the plight of others either in their own countries or in other countries. In particular, in their research on sewage treatment in Germany, Seifert et al. (2019) defined the environment and water quality as victims and employed a bystander effect perspective. Consequently, the ecological environment is gradually personified as the victim in the bystander effect (Geller 1995; Seifert et al. 2019; Tam et al. 2013). However, few studies have systematically connected the bystander effect theory to the protection of the ecological environment. The aim of this paper is to expand the application of social psychology, represented by the bystander effect, in policy design. In the future, a balance should be struck between monetary and non-monetary factors when designing environmental conservation incentive policies.

Sample size in social experiments

When planning the experimental design, several common classes of experimental paradigms used in social sciences have been reviewed. Commonly, social science experiments are categorised based on factors such as the experimental environment (i.e., laboratory or real world), participant identity, treatment, background, and result measurements. In addition to laboratory experiments, field experiments have gained in popularity among social scientists since the 20th century (Shadish 2002). Compared to observational studies, field experiments provide higher internal validity (Grose 2014) and have thus become the preferred strategy for data collection. In social sciences, field experiments broadly fall into the following four areas of substantive and policy research (Baldassarri and Abascal 2017): First, randomised controlled trials focus on policy interventions associated with economic development, poverty reduction, and education. Second, experiments are conducted to explore how norms, motivations, and incentives affect behaviour. Third, experiments are conducted to examine political mobilisation, social influence, and institutional impacts. Fourth, experiments are conducted that specifically focus on examining prejudice and discrimination. Undoubtedly, randomised controlled trials are one of the most prominent experimental paradigms in economics, and many economic articles have established clear causality through randomised controlled trials. However, most randomised controlled trial studies require appropriate planning, adequate research funding, and long-term follow-up efforts (Duflo and Banerjee 2017). Importantly, randomised controlled trials have been criticised for primarily assessing the effectiveness and relative cost-effectiveness of interventions without sufficiently focusing on the underlying mechanisms. However, field experiments that explore norms, motivations, and incentives enable research beyond the classical laboratory paradigm and are designed to test both theoretical derivations and explicit assumptions (Baldassarri and Abascal 2017). This aligns with the goals of the present study.

The determination of sample sizes in social science experiments, particularly in economics experiments, has long been a subject of controversy. While framed field experiments are commonly used to assess ex-ante policy elements (List and Price 2016), identifying the appropriate sample size remains challenging. A review by Grüner (2020) found that less than 10% of publications use G power to calculate power and determine sample size. Experimental economists often rely on previous studies and cost considerations when determining sample sizes before conducting empirical experiments; however, this approach often overlooks important factors like the properties of critical experimental variables. For example, the between-subject design effectively avoids errors caused by experimental sequence, but the required number of subjects is enormous, making it difficult to exclude the impact of individual differences. While the within-subject design is unsuitable for certain variables, it requires fewer subjects in repeated tests of homogeneous participants and can rule out the impact of individual differences. Hence, the authors believe that the determination of sample size should be more appropriate, meaningful, and humanised, while also emphasising the importance of experimental design.

Hypotheses

The applied experimental design is based on the bystander effect. However, the bystander effect is not fixed; through the bystander effect, various factors affect both cognition and emotion (Hortensius and De Gelder 2018), causing noticeable weakening or enhancement. Latané and Darley (1970) explored the bystander effect from three different psychological perspectives.

The first perspective is the diffusion of responsibility, which refers to the tendency to subjectively divide personal help responsibility among the number of bystanders (N). It is traditionally assumed that the more bystanders, the less individual responsibility each bystander experiences (Fischer et al. 2011). Bystanders prefer to contribute little or nothing at all (Thomas et al. 2016), which is expected in larger groups because the failure rate of cooperation increases with the generation of the bystander effect and the associated decrease in contribution. Furthermore, joint returns lead to fewer social responsibility decisions, perhaps because they provide participants with moral leeway to act less socially responsibly (Vecchi 2022). If there are more bystanders in cyber bullying cases, participants will feel less responsible to help and are consequently less willing to help (Obermaier et al. 2014). However, the weakened proportional relationship between scale and the bystander effect has been challenged. In their analysis of the rational component of a bystander, Greitemeyer and Mügge (2013) found that the bystander effect did not occur when the bystander had to be more responsive and it was not possible for one person to complete the task. Variation in the number of participants can correspond to the community size and level of involvement in PES projects. The donation of each person may receive more attention and evaluation in smaller communities or groups, which potentially increases the individual motivation to participate. This can be reflected in small-scale ecological compensation projects within smaller communities, where individual contributions are more important for the overall goal, and each person’s actions can be more easily recognised. However, in larger groups, individuals may perceive their contributions as relatively minor, leading to free-riding behaviour. This corresponds to larger community or national-level ecological compensation projects, where individuals may feel that their contributions only have a limited impact on the achievement of the overall goal. Ecological conservation is a long-term and collective responsibility. Compared to two, four, or multiple bystanders, when there is only one bystander, during the cost analysis phase, individuals will assess whether they can complete the ecological conservation task alone. An increase in the number of bystanders may enhance an individual’s expectations of completing the task, thereby potentially weakening the bystander effect. To this end, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Faced with the collective responsibility event of ecological protection, an increase in the number of farmers will not lead to decentralised responsibility, and the number of farmers’ donations does not decrease as the number of farmers increases.

The second perspective is evaluation apprehension, which refers to the fear of being judged by others when acting publicly. When people feel observed, they become afraid to make mistakes or perform acts of misconduct, making them less willing to intervene in critical situations (Markey 2000). While each bystander is a potential judge of behaviour, in a large group, people are less likely to identify others and feel more anonymous because they can hide in the crowd (Prentice-Dunn and Rogers 1982). Thus, individuals are less likely to be judged and evaluated individually, and the presence of others may be associated with an associated loss of responsibility (Diener et al. 1980). In actual PES projects, the disclosure or non-disclosure of the amount of the compensation reflects a trade-off between project transparency and participant privacy. For example, PES projects may choose to disclose the compensation amounts of donors to increase their transparency. However, other projects opt for non-disclosure of the specific compensation amounts to respect the privacy of donors. Instead, they adopt individual negotiations with each household, especially in smaller communities or under sensitive situations involving individual donations. This approach can alleviate potential social pressures and encourages those who may not be willing to disclose their donation amounts when participating publicly. Banerjee et al. (2021) discussed the importance of interactions and comparisons among farmers, emphasising the vital importance of close interaction and comparison. However, the unique value and importance of anonymity should also be noted. Conversely, such interactions and comparisons may increase the need for and perceived value of anonymity under certain circumstances. In closely-knit communities, individuals prefer to remain anonymous in certain situations to avoid potential negative social evaluations or conflicts. This suggests that anonymity plays a key psychological buffer role in specific contexts, such as in the choice and implementation of environmental conservation behaviours.

Furthermore, the literature indicates that anonymity can still considerably impact individual behaviour, even in highly interactive and non-anonymous environments. Anonymity can reduce the fear of social evaluation and encourage individuals to engage in behaviours that may not fully align with group norms (Kim et al. 2019; Pan et al. 2023). Because of their close community relationships and frequent interaction and comparison, anonymity becomes particularly important for farmers. In the non-anonymous (i.e., disclosed) state, self-awareness of people can also lead to a reversal and weakening of the bystander effect (Van Bommel et al. 2012). When non-anonymity is established, it is highly likely that a reversal of the bystander effect emerges, and that farmers’ awareness of ecological protection increases. To this end, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: In case of anonymity, farmers will donate more because of the bystander effect.

The third perspective is pluralistic ignorance. The strongest bystander effect occurs when nobody intervenes, as everyone feels that no one else perceives an emergency. As with ignorance, the presence of more potential helpers dilutes everyone’s responsibility, which is further enhanced by the bystander effect (Thomas et al. 2016). In particular, the perception of an emergency further weakens the bystander effect (Liu et al. 2021). In the face of naturally occurring violent emergencies, Liebst et al. (2018) identified the setting of emergencies and the type of bystander intervention as risk factors for victimisation. The strength of the bystander effect varied systematically with the bystander’s perception of the danger to be expected. Levine and Thompson (2004) also noted that a change of bystander effects (i.e., their increase or weakening) can also affect personal emotions. The designation of emergency levels reflects the influence of the real-world emergency of ecological issues on public acceptance and public participation. In the context of PES projects, when the public is confronted with ecological problems characterised by high emergency levels (such as deforestation and water pollution), people are often more readily mobilised because of the evident consequences associated with these issues. Conversely, attracting public attention and resources to problems with lower emergency levels (such as biodiversity loss and land degradation) may prove more challenging, as the impacts of such problems may be less immediate and conspicuous. In the present paper, the ecological situation is either described as a high emergency (e.g., disasters caused by severe ecological damage, debris flow, and earthwork collapse) or a low emergency (ordinary degree of pollution without a specific disaster). When faced with a more urgent ecological problem, farmers further enhance their sense of responsibility for protection. To this end, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: In a high emergency ecological situation, the weaker the bystander effect, the more farmers will donate.

However, although the regional scale itself has rarely been the central focus of research on the bystander effect, it is valuable for the perception of ecological protection responsibility. Cuba and Hummon (1993) established a social-spatial scale (i.e., community, region, state, and supranational scale) along which, the common interests of loyalty and perception can be gauged. Goldberg (1994) showed that boundaries at social and spatial scales may define individual responsibility to others, and they argued to prioritise obligations: the most substantial obligations should be at the centre and weakening as more marginal space emerges. Moreover, the cost-reward model by Dovidio et al. (1991) indicates that people have a stronger sense of responsibility when they expect a greater return. With increasing area, people will obtain less return from their ecological protection efforts. To this end, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: With increasing regional scale, the stronger the bystander effect, the smaller the contribution of individual farmers.

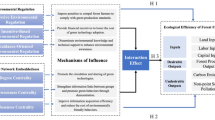

The specific research hypotheses is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Depicts how the experimental hypotheses are integrated into the experimental design. At the start, the three dimensions of the bystander effect—diffusion of responsibility, evaluation apprehension, and pluralistic ignorance—as well as location dependence are incorporated. Then, whether the bystander effect in environmental conservation is influenced by people’s pro-environmental behaviour is explored from both emotional (evaluation apprehension and location dependence) and cognitive (diffusion of responsibility and pluralistic ignorance) perspectives.

The relationship between the bystander effect and ecological conservation is still an area of ongoing exploration. In our study, we aim to highlight that the role of theory is primarily to offer a framework for developing testable hypotheses, rather than to provide a comprehensive explanation of ecological behavior. As Smith (2010) suggests, the process of hypothesis testing often involves adapting theoretical frameworks to new contexts, which can offer valuable insights. In this study, the bystander effect serves as a starting point for hypothesizing that social influences may reduce individuals’ pro-environmental behaviors when they perceive others as inactive. Our experiment was designed to test this hypothesis within the context of ecological conservation, specifically under conditions where non-monetary incentives are involved. Thus, the theoretical framework should not be seen as a full explanation of the complexity of ecological behavior, but rather as a foundation for empirical testing. By integrating social psychological theories with ecological conservation, we hope to offer an exploratory approach that contributes new perspectives to the understanding of environmental behavior, while acknowledging that further research is needed to refine these insights (Steg and Vlek 2009; Epley et al. 2007).

Experimental Design

Research area

Because of considerations of the representativeness of the experimental environment, field experiments were conducted in Napo County, China. Napo County is located in the western part of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China, bordering the provinces of Cao Bang and Ha Giang of Vietnam. The border length is 207 km, identifying it as the county with the longest land border in Guangxi. Napo County covers a total area of 2,231.11 km2, with a forest coverage rate of 57.3%. Napo County has a population of approximately 170,000 people and is a typical rocky desertification area that has been categorised as an ecologically vulnerable area by the Chinese government. Napo County cannot sustain a sufficient self-sustaining population; therefore, the population has always been in an outflow state, and local farmers must strike a balance between livelihoods and ecological protection.

As a representative example of an ecologically vulnerable area, the Chinese government has designated the county as facing challenges related to rocky desertification and fragile ecological resources. This makes Napo County an ideal setting to examine the impact of research interventions on the ecological environment. Furthermore, the remote and isolated nature of Napo County ensures a reduced level of external interventions and influences, making it a perfect location to observe the specific effects of experimental treatments. The absence of large-scale industrial activities and industrialised agricultural practices in this area also allows to study the impacts of interventions without strong confounding factors.

In addition to its ecological characteristics, the geographical location of Napo County is of particular interest for this study. Bordering Vietnam, the county provides cultural exchanges between different ethnic groups such as the Zhuang, Yi, and Han. This diverse community context offers an enriching environment in which the effects of research interventions on different ethnic communities can be explored.

Determination of sample size

At the interview stage, mainly local basic human and geographical information was obtained and various materials for interventions were collected. Because of its wide use as a classical experimental paradigm for altruistic behaviour in ecological donation experiments (Wolf and Dron 2020; Ziegler 2021), the traditional dictator game was adopted in the experimental design. The subjects were assigned to the role of bystander, the virtual receiver role was set, and the position remained fixed throughout the experiment.

Because this is a field experiment with local villagers in an ecologically fragile area, the researchers faced difficulties such as rugged mountain roads, lack of a universal local language, and time constraints caused by villagers’ agricultural work and childcare responsibilities. In this case, subject recruitment was conducted as reasonably as possible to not disturb the subjects. To avoid the retrieval practice effect and mental fatigue effect while reducing the number of subjects, the experiment was designed as a mixed experiment. The three dimensions of the bystander effect, namely diffusion of responsibility (population size), evaluation apprehension (disclosure or non-disclosure), and pluralistic ignorance (emergency level), were used as between-subject variables. The administrative region corresponds to the donation as the within-subject variable, and the administrative unit checking the donation itself is progressive and different; this differs from the round set design between subjects. The required sample size was determined using the “a priori” function in G-Power 3.1 (Faul et al. 2007). An effect size of 0.25 and a significance level of 0.05 were established, yielding a power of 0.8003 for a sample size of 54. To ensure robustness, the sample size was adjusted to 56. Subsequently, the “post hoc test” feature of G-Power 3.1 was employed to reassess the required sample size under the same parameters (effect size = 0.25, significance level = 0.05, and total sample size = 56). The recalculated results had a power of 0.823, which exceeds the threshold of 0.8, thereby confirming that the power of the sample size for the test meets the specified requirements.

After calculating the sample size, experimental studies were briefly reviewed with smaller samples. Despite the small size, many scholars have successfully reflected actual mechanisms in field or laboratory experiments (Brozyna et al. 2018; Sullivan et al. 2022; Müller et al. 2022). For example, Haider et al. (2019) conducted a field experiment in restaurants in Pakistan with a total sample size of 51, and divided 28 and 23 hospitality employees into experimental and control groups, respectively. Using a pre-post questionnaire design, they measured the awareness of environmentally sustainable work practices and other variables among employees. The results indicated that after cognitive intervention, employees’ pro-environmental practices increased by 87%. Therefore, it can be assumed that the sample size used for this study is appropriate, meaningful, and humanistic.

Participant recruitment

After Napo County had been selected as study area, a specific sampling of experimental sites was conducted. Two administrative villages were selected as experimental sites, considering the sample size.

First Stage: To minimise interference by irrelevant variables and facilitate future coordination with local governmental agencies, one township was selected at this stage. A list of townships under the jurisdiction of Napo County was obtained (totalling nine) of which Chengxiang Town was randomly chosen using the RANDBETWEEN function in Excel.

Second Stage: Then, a list of communities or administrative villages under Chengxiang Town’s jurisdiction was acquired, totalling 30. Zhengyu, Chengbei, Chengnan, and Kedong were categorised as community types and were excluded from the experiment because of the requirements, leaving 26 administrative villages. Of these, Zhezhong Village and Dala Village were randomly selected using the RANDBETWEEN function in Excel.

Third Stage: Ethical approval for the experiment was obtained before village officials were officially contacted. In the preparatory phase of the survey, the village cadres of the sample villages were contacted. Letters were submitted to cadres, explaining our identity and the purpose of our visit (i.e., to conduct field experiments). After signing a data confidentiality agreement that precluded the disclosure of personal communication information, a real-time roster of village households was obtained from cadres, including the names of household heads, addresses, and contact details.

At this time, Zhezhong Village had 310 households with 1294 individuals, and Dala Village had 393 households with 1515 individuals. For the experiment, 28 households from each administrative village were required and one member from each household was invited to participate in the experiment. The day before the official experiment, the researchers visited the experimental villages, using a randomisation function in Excel to select potential participants. After the selection, the chosen participants were visited to inquire about their availability and willingness to participate in the survey. At this stage, potential participants received information about the research background and objectives. Other participants were selected if the response was negative (e.g., no time or willingness to participate or all family members not at home). Upon receiving a positive response, participants were invited to a designated location (a village library was utilised) during their randomly assigned time slot (either the morning or afternoon of the experimental day). Upon their arrival, participants were asked to draw lots to determine their assigned experimental group. The specific sampling process is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Informed consent

Before the official start of the experiment, each participant received an informed consent form. The informed consent form provides potential participants with comprehensive information regarding the research background and objectives. It is worth noting that because of concerns that participants might have difficulty understanding Mandarin or written content, local residents were recruited to act as experimenters. They helped to confirm whether the interviewees truly understood the content of the informed consent form. Additionally, as some participants were unable to sign the document with their complete names, they were asked to make a circle as a representation of their signature. Once participants had signed the informed consent form, the experiment began officially. The informed consent forms were organised and securely stored. After completing the experiment, the researchers further engaged in conversations with the villagers, expressing thanks and well wishes. The authors believe that demonstrating humanitarian care and respect for the participants during the field experiment is of the utmost importance.

External validity of the experiment

In discussions on the internal and external validity of economic experiments, often, a distinction is made between laboratory and field experiments. Roe and Just (2009) defined the external validity as the ability to generalise the relationships discovered in the experiments to other people, times, and environments. In this study, the authors discuss laboratory experiments, field experiments, natural experiments, and empirical evidence in terms of internal validity, external validity, topic and subject limits, as well as replicability. Furthermore, researchers have identified challenges to the external validity of experiments, such as generalisability, realism (or ecological validity), and robustness (Lynch Jr 1982; Roe and Just 2009; Winer 1999).

The aim of this experiment was to maximise its external validity. Initially, in the setup of this study, the authors planned to explore potential non-monetary incentives in ecological conservation through laboratory experiments. In fact, two small-scale pilot experiments were conducted and multiple modifications to the experimental procedures were tested. The results obtained from the laboratory experiments were similar to those obtained in the field experiments. However, considering the central role of farmers in ecological conservation and the primary target audience of PES projects, the external validity of this experiment needed to be enhanced in terms of sample representativeness. Therefore, the authors decided to switch from laboratory experiments to field experiments to address the research question.

Because of the external validity challenges field experiments face, the external validity of the experimental design was enhanced. A discussion on the challenges faced by external validity is presented in the following:

Generalisability

Generalisability refers to whether the results of a research study obtained using specific sampling methods (e.g., recruitment and purposive sampling) can be generalised to a larger population of interest. Just as many laboratory experiments have been criticised for predominantly using samples of western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic (so called “WIRED”) students (Henrich et al. 2010), field experiments often recruit participants from other specific populations. Taking this into consideration, the current experimental design did not rely on village cadres to recruit participants from the village. During the preliminary survey phase, the village cadres of the sample villages were contacted. A roster of the village was obtained, which included the names of household heads, specific village groups, contact information, and other relevant information. Using the RANDBETWEEN function in Excel, the appropriate number of potential participants was randomly selected. Then, the selected participants were visited in their village prior to the experiment, and they were asked about their availability and willingness to participate in the survey. If the response was negative, a different participant was selected. At the same time, when scheduling the experimental sessions for participants, random assignment was conducted again. Participants were only informed in which field experimental session they would participate shortly before the formal experiment began. The research team made every effort to enhance the generalisability of the experiment by minimising systematic errors through random sampling.

Realism (or ecological validity)

Realism (or ecological validity) refers to the representativeness of the experimental environment and whether results can be generalised to more natural settings. In the conducted experiment, considering the representativeness of the experimental environment, field experiments were conducted in Napo County, China, which is a typical rocky desertification area that had been designated as an ecologically vulnerable region by the Chinese government. During the preliminary exploration, an initial understanding of the two sample villages was gained. Because of a lack of infrastructure and weak hygiene awareness, pollution still exists in these villages. As experimental stimuli from specific regions within each administrative area were needed as village-level stimuli, real photos of small rivers, household garbage, and land pollution in these villages were taken. In the experiment, village-level stimuli were derived from real sources within their communities, including river pollution and littering. Moreover, the experimental goals were also addressed by exposing participants to pollution stimuli from their real-life regional environments.

In China’s administrative system and real life, Article 30 of the Chinese Constitution stipulates that the country’s three-level administrative regions are divided into provinces (autonomous regions), counties, and towns. However, because the two villages sampled in the experiment are also the residences of the county government, in fact, the towns in the experimental area overlap with the town buildings in the county. This peculiarity weakens the local farmers’ perception of the town level. Therefore, in this study, an administrative region is defined as the five levels including village, Napo (county), Guangxi (provincial area), China (country), and the whole world.

Regarding the decision on population size, the group sizes were set to 2-person, 4-person, and 8-person groups. Small-scale groups (i.e., 2-person groups) can simulate decision-making processes within a single household, such as discussions between spouses or parent-child interactions. In this setting, decisions often rely on close personal relationships and direct dialogues, reflecting how individuals in small-scale groups balance their personal interests with their environmental responsibilities. Medium-scale groups (4-person groups) can represent small-scale discussions among neighbours or relatives, for example, several neighbouring farming households gathering to discuss whether to join an ecological compensation program. This medium scale allows for more exchange of viewpoints and may introduce a certain degree of social pressure or consensus formation. Large-scale groups (8-person groups) may represent broader community meetings or collective decision-making scenarios involving multiple households. In such large groups, individuals may feel pressure from the group or consider more group-oriented interests rather than their personal interests.

Robustness

Robustness refers to whether the tasks, stimuli, and settings of the experiment produce extraneous differences that should not occur. To ensure the robustness of the experiment, consistency was ensured in the experimental design. Therefore, in all experimental groups, the same staff was used, and for groups corresponding to the same stimuli, identical pictures and videos were used in the presentation. Even for different types of stimulus materials, it was ensured that the durations of all stimuli were roughly the same. The experimental locations are village libraries, and to avoid any unintended variables, all these aspects were kept consistent throughout the entire experiment. As pointed out by Cherry et al. (2002), the initial amount of money given to participants in the experiment significantly impacts the outcomes. To enhance the practical significance of participants’ decisions, the time participants might spend has been calculated, including an estimated 2-h commuting time. Additionally, based on the local labour market hourly rate (with an additional 50% premium), a payment value of 30 yuan has been determined for participation. One-third of this value was provided in the form of adjustable tokens, where donation of these tokens in the experiment was considered equivalent to participants donating their own money.

Replicability

Replicability refers to whether the discovered relationships can be replicated across participants, research environments, and time intervals. The importance of replication in improving the external validity of experiments was fully acknowledged. However, it must be recognised that one potential drawback of conducting field experiments is that compared to laboratory experiments, replication can be more challenging. Levitt and List (2009) discussed replication in three degrees: the first degree involves obtaining the actual data from someone else’s experiment and reanalysing these data to test the original findings. The second degree involves running a similar experiment with a new sample to determine if similar results can be generated with different participants. The third degree involves using a new research design to test the hypotheses of the original study. While the first and third types of replication are relatively simple to accomplish, the second type of replication (i.e., rerunning the original experiment with a different sample) is more difficult. This difficulty arises because many field experiments of this nature require the cooperation of external entities, detailed knowledge, and the ability to manipulate specific factors.

Additionally, when replicating empirical results, differences in cultural backgrounds can lead to substantial deviations. For example, Cohn et al. (2019) measured civic honesty by the email response rates of “lost” wallets returned to social institutions across 40 countries. However, in a replication study by Yang et al. (2023) that incorporated the cultural dimensions of individualism and collectivism, civic honesty was assessed using email responses and wallet recovery, leading to markedly different empirical results. This difference serves as a reminder that cultural differences among participants should be thoroughly considered during such experimental replication, often requiring the reorganisation of experimental materials and the selection of key experimental indicators.

Experimental procedures

During the experiment, to ensure randomness, lots were randomly drawn and participants received a number (represented by a label) as a form of identification in the game. Before the formal experiment, participants must pass an experiment rule questionnaire, designed to test if participants really understood the rules; they could only join the formal experiment after they passed the test. In the standard experiment, there were 2, 4, or 8 participants in each experiment for a total of five rounds. Participants were prohibited from communicating with other participants.

In the “Intervention Implementation” stage, the core of the experiment involved presenting these groups with visual content that illustrates two degrees of ecological crises. The “High Emergency Level” involves images and videos that portray major ecological disasters, whereas the “Low Emergency Level” involves images and videos portraying less intense ecological distress situations. Consistency was maintained in both the type and length of the content. Following the presentation of the materials, the host commenced the donation proceedings.

In the “Donation” stage, following exposure to these scenarios, the experiment bifurcated into two informational disclosure pathways. In the “Disclosure” pathway, a disclosed approach was adopted, where the host queried participants about their donation amounts each round and publicly disclosed these amounts. In contrast, in the “Non-Disclosure” pathway, confidentiality regarding the participants’ contributions was maintained, with the host refraining from inquiring about the donation amounts, which were then recorded in private.

In the “Outcomes” stage, participants chose a donation amount within a 0–10 yuan range from their tokens in each round, placed it in the envelope designated for that region, and noted the amount on the donation record form. Tokens could not be reused across rounds. Participants were encouraged to consider both their ecological protection responsibilities and expected returns for the region. Return ratios were set as follows: village 50%, county 40%, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region 30%, China 20%, and the world 10%, mirroring real-life implications. Following each round, the host asked each participant about their donation, which was then recorded publicly.

Upon completing all rounds, the total donations for each region were tallied with respective return values and evenly distributed among group members. Accumulated tokens were converted into cash at a predetermined rate, plus a 20 yuan participation reward for each participant. After deducting the return proportion from the total amount of donations in each round, the actual amount was donated to the ecological protection organisation or government in the corresponding region. Figure 3 shows the procedures in more detail.

Shows the experimental process starting from random grouping, with different strategies in both stimulus reception and donation areas, resulting in 12 different data types representing a between-subjects design. The outcomes phase reflects the within-subject experimental design, where the set return rate corresponds to the expected reporting in location dependence.

Data collection and analytic strategies

The utilised data collection tool comprises three components: The first component is the donation form, which was completed by the participants in the experiment. This component records the participants’ specific groups, numbers, and donations for each region. The second component involves participants completing a post-experiment questionnaire that primarily collects their socio-demographic information. Additionally, to assess the farmers’ subjective perception, the third component is a “responsibility-profit ranking”, which was incorporated into the questionnaire. Participants were asked to rank the level of ecological protection responsibilities (1 = highest responsibility; 7 = lowest responsibility) and profit for different entities. These entities encompass all human beings, the central government, local governments, village organisations, individuals who could potentially contribute to environmental pollution (such as plant or animal breeders benefiting from high environmental consumption and industrialists), relatives and friends, as well as the participants themselves. When all experiments were finished, all questionnaires were carefully examined and the data were promptly recorded.

Overall, this study focuses on the amount donated and total donation volume by area as dependent variables, and the mean values of each group category are compared. The use of a symmetric mixed experimental design ensures that interventions caused by other internal factors within each group category cancel each other out. Both grouping variables, “emergency level” and “disclosure or non-disclosure” are categorical and only include two groups, with the dependent variable “regional donation” being ratio data. Given that the overall sample size exceeds 30 and preliminary tests indicate that the values of each dependent variable are normally distributed, it is appropriate to use the independent t-test for a preliminary analysis of “emergency level” and “disclosure or non-disclosure”. Levene’s test for equality of variances is utilised in SPSS version 26 for variance homogeneity. Combined with the overall experimental design, repeated measures ANOVA is used for further interaction analysis. The specific Formula (1) is as follows:

\({{\rm{T}}}_{{{emergency}}}\) is the t-value for testing under each regional donation amount, \({{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{h}}}\) represents the mean donated amount in the sample under High Emergency Level; \({{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{l}}}\) represents the mean donation amount in the sample under Low Emergency Level; and \({{\rm{n}}}_{{\rm{l}}}\) are the sample sizes for the two samples; \({{{S}}}_{{{p}}}^{2}\) is the pooled variance, with \({S}_{h}^{2}\) and \({S}_{l}^{2}\) being the variances of the two samples.

Similarly, for the disclosure group, Formula (2) is as follows:

\({{\rm{T}}}_{{{disclosure}}}\) is the t-value for testing under each regional donation amount, indicating the mean donation amount in the sample with disclosure versus non-disclosure; \({{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{y}}}\) and \({{\rm{X}}}_{{\rm{n}}}\) are the mean values of donations under disclosure and non-disclosure, respectively; \({{\rm{n}}}_{{\rm{y}}}\) and \({{\rm{n}}}_{{\rm{n}}}\) are the sample sizes for the two samples; \({S}_{p}^{2}\) is the pooled variance, with and \({S}_{n}^{2}\) being the variances of the two samples.

The grouping variable “population size” was categorised into three groups, and the dependent variable “regional donat \({S}_{y}^{2}\) ion” was quantitative. The overall sample size exceeded 30 and preliminary checks indicated a normal distribution of dependent variable values; therefore, the F-test can be applied for a preliminary analysis of “population size.” The specific Formula (3) is as follows:

\({\rm{F}}_{peopulation}\) is the F-value for testing under each regional donation amount, indicating the ratio of between-group variance to within-group variance; \({{\rm{SS}}}_{\_{\rm{between}}}\) and represent the mean squares between groups and within groups, respectively; the number of groups k and total sample size N, along with sample sizes \({({{\beta }}{{\gamma }})}_{{{\_jk}}}\) \({{\rm{n}}}_{\_{\rm{i}}}\) and mean values \({{\rm{X}}}_{\_{\rm{i}}}\) for each group, are used to calculate the variances; X is the total mean value of all samples; \({{\rm{X}}}_{\_{\rm{ij}}}\) is the j-th observation in group i.

The analysis of repeated measures ANOVA includes three between-subjects factors (i.e., emergency level, disclosure or non-disclosure, and population size) and one within-subjects factor (i.e., administrative region). The specific Formula (4) is as follows:

\({{\rm{\mu }}}_{\_{\rm{donations}}}\) represents the population mean donation for each level; \({{\rm{\alpha }}}_{\_{\rm{emergency}}}\) represents the main effect of the emergency level i (high emergency level vs. low emergency level); \({{\rm{\beta }}}_{\_{\rm{disclosure}}}\) refers to the main effect of the disclosure status j (disclosure vs. non-disclosure); \({{\rm{\gamma }}}_{\_{\rm{poupulation}}}\) represents the main effect of the population size k (2, 4, and 8); \({{\rm{\theta }}}_{{{\_l}}}\) denotes the main effect of the administrative scale l (i.e., sample villages, Napo County, Guangxi, China, world, and total) as the within-subject variable. \({({{\alpha }}{{\beta }})}_{{{\_ij}}}\), \({({{\alpha }}{{\gamma }})}_{{{\_ik}}}\), and indicate the interaction effects between pairs of independent variables. U represents the overall interaction effects among variables. \({({{\alpha }}{{\theta }})}_{{{\_il}}}\), \({({{\beta }}{{\theta }})}_{{{\_jl}}}\), and \({({{\gamma }}{{\theta }})}_{{{\_kl}}}\) reflect the interaction effects between independent variables across subjects and within subjects. \({({{\alpha }}{{\beta }}{{\gamma }}{{\theta }})}_{{{\_ijkl}}}\) represents the four-way interaction effect among all independent variables. \({{{\varepsilon }}}_{{{\_ijkl}}}\) is the error term, accounting for unexplained random variation. Following repeated measures ANOVA, multiple post hoc comparisons and simple effect analyses were conducted.

In addition, combined with the questionnaire, the calculation of differences between two adjacent levels of donation within subjects was introduced, denoted as ∆re = (n_donations + 1) - n_donations, and samples with reversal (∆re > 0) were identified. Simultaneously, ∆r - b = (S_rank_r - S_rank_p) was explored based on subjective weight rankings. ∆r-b > 0 indicates that farmers perceive a smaller responsibility and larger profit for the subject; ∆r-b < 0 indicates that farmers perceive a greater responsibility and smaller profit for the subject; ∆r-b = 0 indicates that farmers perceive the assumed responsibility of the subject as equal to the profit.

Results

Descriptive statistical analysis

By combining supplementary questionnaires, specific data statistics on the personal socioeconomic characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 1.

A total of 56 subjects were drawn for this experiment, among which 35 were males, accounting for 62.5%, exceeding the number of female participants. Regarding their educational level, 41.07% of participants had primary education or below. At the same time, the proportions of junior high, high school/secondary vocational, and college or above were 17.86%, 26.79%, and 14.29%, respectively, indicating a generally low education level among participants. This reflects the limited availability of educational resources in the area, which is consistent with the educational level in most rural areas, highlighting the cognitive representativeness of the subject group. Farmers’ education levels may influence their sense of social responsibility and participation in ecological conservation. Those with lower education levels may have a limited understanding of the long-term benefits of ecological protection, leading to a weaker sense of responsibility. They may prioritize immediate economic returns over long-term ecological gains. (Postma 2006). Most families had a cultivated land area of 0–6 Mu (accounting for 80.36% of the total), reflecting limited local arable land resources. Regarding the family structure of participants, the area is dominated by nuclear families, with those having six or fewer members accounting for 91.07%. Most families (67.86%) had 4–6 members, while the farming population was mainly concentrated in the 0–2 range, accounting for 69.64%, suggesting a dispersion of labour or a common working mode of working away from the area. Small land holdings and labor outflow are common in many rural areas. With limited arable land, farmers might prioritize livelihood security over long-term ecological responsibilities(Jayne et al. 2014). Moreover, resource scarcity and labor outflow affect farmers’ collective action. While labor migration may ease economic pressures, it can disperse family responsibilities and reduce collective participation in ecological conservation. The division of household and land management tasks may also weaken ecological responsibility, particularly for migrant workers who are less engaged in daily environmental protection.

Economically, nearly half of all sampled families had an annual total income of 30,000 or less, indicating a low level of economic development in the area. Moreover, income generated through farming was generally low, with nearly half (48.21%) of the families reporting an annual farming income of only 1000 yuan or less, which is typical of self-sufficient small-scale farmers. Most families (98.21%) had a monthly farming income of less than 1500 yuan. In terms of their living environment, the vast majority of participants (92.86%) lived in the village long-term. The original questionnaire indicated that all participants choosing to live in the county town were students residing in the countryside during summer and winter vacations, which is consistent with the situation of hollow villages in the area. The proportion of Party members was 19.6%, reflecting a relatively small proportion of Party members in the community. This characteristic aligns closely with the situation of Chinese farmers. Agricultural production in China is mainly based on small-scale family farms (Ren et al. 2019). Meanwhile, the massive outflow of rural labor, with young people migrating to cities, has led to an aging rural population and a decline in social functions. These issues are pressing in many rural areas. Such demographic changes have also weakened social cohesion and environmental governance in rural communities (Li et al. 2019).

Based on the descriptive statistics of demographic characteristics obtained from the questionnaire, SPSS version 26 was used to calculate and analyse the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values of each item under various dimensions in the questionnaire. These data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that the average age of subjects was 46.07 years (±16.613), with a maximum age of 73 and a minimum age of 16. The scores on ecological tests varied greatly among subjects, with a range of 70 points and an average score of 69.46 points, with a standard deviation of 18.822 points. These data indicate that the awareness of ecological protection among the residents of these villages was at a moderate level with room for improvement, and there were significant differences in awareness among subjects. The total donation amount ranged from 20 to 44 yuan, with an average amount of 30.607 ± 6.214 yuan, indicating substantial variation in donation amounts. At the village level, the average donation amount was 8.259 ± 1.160 yuan. For Napo County, the average donation amount was 6.795 ± 1.257 yuan; for Guangxi, it was 5.607 ± 1.364 yuan; for China, it was 6.313 ± 1.923 yuan; and for the world, it was 3.634 ± 1.767 yuan. Differences in donation amounts were found across different levels, necessitating further analysis.

T-test under the pluralistic ignorance dimension

First, the t-test was conducted under the pluralistic ignorance dimension (i.e., emergency level). The aim was to analyse whether a significant difference exists in eco-donations between high and low emergency level groups. The data show that the amount donated to a high emergency is generally higher than that donated to a low emergency, even across different donation areas from the sample villages to worldwide. This evidence suggests that the perception of an emergency stimulates ecological conservation responsibility. At the same time, the results of the analysis strongly support Hypothesis 3, which states that a high level of emergency can substantially reduce the bystander effect and encourage farmers to donate more money. Detailed results are shown in Table 3.

At the village level, the donation level under a low emergency was 7.59 ± 1.03 yuan. In comparison, the donation level under a high emergency increased to 8.93 ± 0.87 yuan, the t-test result was −5.267, and the p-value was less than 0.001, which is a significant result. This result indicates that under an emergency, the amount donated to the village increased significantly. Regarding donations to Napo County, the donations under a low emergency level were 5.96 ± 0.87 yuan, while those under a high emergency level were 7.63 ± 1.01 yuan. The t-test result was −6.572, with a p-value of less than 0.001, further validating the trend of increased donations under a higher emergency level. In the case of donations to Guangxi, the donation amount was 4.84 ± 1.05 yuan under a low emergency level, and 6.38 ± 1.21 yuan under a high emergency level. The t-test yielded a result of −5.071, with a p-value of less than 0.001, indicating that this sector also follows the same significant trend. According to the donations for China, a low emergency donation averaged 5.39 ± 1.55 yuan, while high emergency donations were 7.23 ± 1.83 yuan. The t-test result was −4.050, with a p-value below 0.001, further confirming this significant trend. Regarding donations for global ecological protection, donations under a low emergency level were 2.59 ± 1.03 yuan, increasing to 4.68 ± 1.74 yuan under a high emergency level. The t-test result was −5.462, with a p-value of less than 0.001, suggesting that the same phenomenon was also observed here. Integrating data from all regions, the total contribution under a low emergency level was 26.38 ± 3.50 yuan, while under a high emergency level, this value surged to 34.84 ± 5.41 yuan. The t-test result was −6.952, with a p-value of less than 0.001.

The results supported previous research on the bystander effect and the role of emergency perception. Fischer et al. (2006) found that in high-emergency situations, the bystander effect is reduced because the emergency is more clearly recognized and the cost of inaction is higher. Liu et al. (2021) also showed that when bystanders perceive a situation as a higher emergency, they are more likely to help, driven by increased empathy and a stronger sense of responsibility. This aligns with our findings, where donations increased significantly in high-emergency situations across different donation areas, from village-level contributions to global ecological causes. The increased donations suggest that a high level of perceived emergency enhances the sense of responsibility for ecological protection, consistent with the cognitive processes identified in these studies. Moreover, Dovidio et al. (1991) argue that the cost-reward model explains this behavior: the perceived cost of not acting in response to an emergency outweighs the cost of donating, leading to higher contributions.

T-test under the evaluation apprehension dimension

Subsequently, a t-test was conducted under the evaluation apprehension dimension (disclosure or non-disclosure). The presence or absence of a significant difference between disclosure and non-disclosure groups regarding eco-donation was examined. The results show that the impact of information disclosure is significant in smaller regions but diminishes with increasing area, possibly because of a weakening of social network radiation caused by regional expansion. Hypothesis 4 received partial support. However, it is noted that at large-scale scopes, such as national and global levels, the significant impact of donation disclosure on donation amounts decreased. This finding differs from previous studies in several ways, which are analysed in the Discussion section. The detailed results are presented in Table 4.

At the village level, donations without disclosure amounted to 7.84 ± 1.11 yuan, while those with disclosure were 8.68 ± 1.06 yuan. The t-test yielded a result of −2.882 with a p-value of 0.006, indicating that disclosed donations significantly exceed anonymous donations. In the context of ecological fundraising in Napo County, undisclosed donations were 6.32 ± 1.16 yuan compared to 7.27 ± 1.18 yuan for disclosed donations, with a t-test result of −3.018 and a p-value of 0.004, further proving that disclosed donation amounts significantly surpass undisclosed amounts. In Guangxi, undisclosed donations were 5.20 ± 1.31 yuan, versus 6.02 ± 1.31 yuan for disclosed donations, with a t-test result of −2.343 and a p-value of 0.023, showing a certain reduction in effect. At the national level, non-disclosed donations were 5.96 ± 1.80 yuan, compared to 6.66 ± 2.01 yuan for disclosed donations, with a t-test result of −1.366 and a p-value of 0.178, indicating that the impact of disclosure on donation amounts is not significant across China. On a global scale, non-disclosed donations were 3.18 ± 1.36 yuan versus 4.09 ± 2.02 yuan for disclosed donations, with a t-test result of −1.979 and a p-value of 0.053. Although disclosed donations were higher than non-disclosed donations, this difference is not significance, as it is slightly above the threshold of 0.05. Judging from the total amounts, non-disclosed donations totalled 28.50 ± 5.40 yuan, compared to 32.71 ± 6.35 yuan for disclosed donations, with a t-test of −2.676 and a p-value of 0.010. These data show that overall, disclosed donations significantly exceed non-disclosed donations.

Existing literature suggests that anonymity can influence individual behavior by reducing the fear of social evaluation. Kim et al. (2019) argued that anonymity decreases the impact of group identity, allowing private self-concept to drive behavior, especially in online communities. Similarly, Pan et al. (2023) found that anonymity in social media enhances moral courage, promoting prosocial behaviors despite social risks.However, our findings contrast with these studies. We observed that information disclosure significantly increased donations in smaller areas, such as villages and counties. This suggests that disclosure can encourage more donations by raising individuals’ awareness of social norms and the impact of their actions. This is in line with the bystander effect reversal noted by Van Bommel et al. (2012), where public self-awareness increased helpful behaviors in social contexts. On the other hand, as the scale increased (e.g., national and global levels), the impact of disclosure weakened. At the global level, the difference in donations between disclosed and undisclosed groups was not significant. This could be explained by the reduced influence of local social networks as the area expands. In larger social contexts, the fear of social evaluation becomes less influential, supporting the findings of Kim et al. (2019) that group identity has a weaker impact in larger settings. Overall, our study suggests that information disclosure can significantly encourage eco-donations in smaller regions, but its effectiveness diminishes in larger, more dispersed areas. Future research should explore how to design disclosure mechanisms that can maintain their effectiveness at larger scales.

F-test under the diffusion of responsibility dimension

Next, F-tests were conducted under the diffusion of responsibility (population size). The aim was to analyse whether there were significant differences in eco-contributions between 2-person groups (representing intra-nuclear family decision-making), 4-person groups (representing small-scale discussions among neighbours or relatives), and 8-person groups (representing broader community meetings or collective decision-making scenarios involving multiple families). The results show that there are no significant differences in donation amounts across different group sizes. Notably, in donations for Nanning, Guangxi, China, and the world, the average donated amounts were below the average. Notably, in these donations, the average donation from 8-person groups was the highest. From the analysis above, Hypothesis 1 is supported for most regions, suggesting that an increase in the number of farmers does not lead to a diffusion of responsibility, nor does it decrease the amount farmers donate for collective ecological conservation efforts. The only exception was observed for donations to the world, where an increase in group size seems to encourage more donation behaviour. This result possibly indicates that the drive towards contributing to collective goals may differ between larger areas compared to smaller areas. Detailed results are shown in Table 5.

Drawing from these data, at the village level, the donation amounts for 2-person groups were 8.56 ± 1.40 yuan, those for 4-person groups were 7.94 ± 1.18 yuan, and those for 8-person groups were 8.34 ± 1.09 yuan. The F-test result was 0.844 with a p-value of 0.447, indicating that differences in donation amounts across various group sizes at the village level were not statistically significant. If Napo County served as the ecological donation area, the donation amounts were 6.63 ± 1.41 yuan for 2-person groups, 6.56 ± 1.01 yuan for 4-person groups, and 6.95 ± 1.34 yuan for 8-person groups. The F-test yielded a result of 0.648 with a p-value of 0.535, further corroborating that there is no significant difference in donation amounts across different group sizes. At the Guangxi level, the amounts were 5.25 ± 1.39 yuan for 2-person groups, 5.19 ± 1.22 yuan for 4-person groups, and 5.91 ± 1.39 yuan for 8-person groups. The F-test value was 1.866 with a p-value of 0.183, suggesting that despite a slightly higher donation amount from 8-person groups, the difference remained non-significant. At the national level, the amounts were 6.00 ± 1.85 yuan for 2-person groups, 6.06 ± 1.84 yuan for 4-person groups, and 6.52 ± 2.01 yuan for 8-person groups, with an F-test result of 0.407 and a p-value of 0.671, indicating no significant correlation. At the global level, the amounts were 3.13 ± 1.36 yuan for 2-person groups, 2.63 ± 1.20 yuan for 4-person groups, and 4.27 ± 1.85 yuan for 8-person groups, with an F-test result of 6.712 and a p-value of 0.006, marking the only region that shows a significant difference. In terms of total donations, 2-person groups contributed a total of 29.56 ± 5.45 yuan, 4-person groups contributed 28.38 ± 5.42 yuan, and 8-person groups contributed 31.98 ± 6.54 yuan. The F-test result was 2.073 with a p-value of 0.152, indicating that overall, there was no significant difference in donation amounts across different group sizes.