Abstract

Eleven nations launched the Great Green Wall (GGW) initiative to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land in the Sahel by 2030 and combat worsening desertification. However, investment in the initiative has stagnated, and public funding may be necessary. A key barrier to mobilizing such support is the difficulty in comparing the economic benefits of investing in nature against the trade-offs it may pose for other sectors of the economy. This study applies the Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI) framework to assess the net economic value of the GGW. The IWI measures long-term national productivity by accounting for changes in human capital (HC), produced capital (PC), and natural capital (NC). We compare the growth of these assets and overall IWI between GGW and non-GGW countries. Findings show that in 2019, natural capital comprised 19% of Africa’s wealth, down from 31% in 1992. While NC declined in 16 of 40 African countries over this period, HC and PC expanded in all. Between 1990 and 2019, NC grew by 0.1% annually in GGW countries, compared to a −0.06% decline among non-GGW participants. Despite this, IWI growth in GGW countries was 1.3%, substantially lower than the 3.11% observed in other nations. Projections based on historical growth suggest NC could grow by 3.1% if GGW goals are fully met, or by 1.8% if only partially achieved, both significantly higher than business-as-usual trends elsewhere. However, increased investment in NC may reduce growth in HC, PC, and overall IWI for GGW countries. These results underscore that NC investments under the GGW may slow future economic growth unless external funding offsets opportunity costs. There is a need for external funding to balance ecological restoration with sustained economic development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Sahel is a region with a hot and semi-arid climate stretching across the southernmost of North Africa. Globally, it is one of the areas hardest hit by land degradation and desertification owing to climate change and poverty (Nkonya et al., 2016). Research suggests that the Sahara Desert expanded over the Sahel by 8% from 1950 to 2015 while displacing and eradicating diverse ecosystems (Liu and Xue, 2020). This expansion has had profound implications for the 135 million Sahelians, who heavily rely on rain-fed agriculture and are confronted with significant economic limitations to adapt to this evolving climatic circumstance (Barbier and Hochard, 2018; Coulibaly et al., 2020; O’Connor and Ford, 2014).

In response, a consortium of nations comprising Burkina Faso, Chad, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sudan joined forces to strengthen investment in nature. They conceived the Great Green Wall (GGW) initiative, which is an African-originated program aimed at stopping the environmental, climatic, and developmental challenges of desertification and environmental degradation (Mbow, 2017). Since its active implementation in 2007, the GGW consisted of a holistic approach to ecosystem management envisioning the establishment of a barrier of trees across Sahelian nations (O’Connor and Ford, 2014). The initiative’s main goal is to restore 1 million km2 of degraded land in the Sahel, sequester 250 million tons of carbon, and create 10 million jobs in rural areas by the year 2030. However, the holistic economic benefits of investment in nature under the GGW remain difficult to appraise (Johnson et al., 2023).

This study adopts the Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI) framework to assess the net benefit of a successful GGW initiative for the overall wealth of these nations. Developed by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the IWI framework provides a comprehensive accounting system for evaluating nations’ productive bases across three forms of capital: produced capital (PC), natural capital (NC), and human capital (HC) (Managi and Kumar, 2018). An assessment of variations of this productive base indicates the sustainability of the development of countries and highlights the relevance of investment choice. Therefore, this framework is fit to assess the benefits of investing in nature as it economically values it. It can be used to illuminate the worth of current investment and the tradeoff between investment under the GGW against investment in other forms of capital (Aly and Managi, 2018; Cheng et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024).

Particularly, progress for the GGW goals has been slow. As illustrated in Table 1, only 2.31% of the GGW goal concerning land degradation has been achieved as of 2019. The main reason for the slow progress under the GGW initiative may be financial since countries involved in the GGW initiative, henceforth referred to as GGW nations need to prioritize the most valuable investment. Previous studies argue that USD 33 billion (UNCCD, 2022) or USD 44 billion (Mirzabaev et al., 2022) are required for the initiative. As of 2021, the international community had pledged to disburse 19 billion USD for the program through the GGW Accelerator program (Macia et al., 2023). Hence, an important share of the program needs to be funded by the governments of the GGW nations. However, their budget is highly limited. For instance, the total fiscal budget for Nigeria, which is the most developed Sahel country, was USD 19 billion total in 2020. Thus, although research shows that African countries may benefit between 1.1 and 4.4 USD for every USD invested in land restoration under the GGW (Mirzabaev et al., 2022), they may not move policymakers for one important reason. Governments may not invest in environmental projects if their profitability is lower than other sectors of the economy (Bilal et al., 2019). African economies are geared around income maximization, whereas benefits from investment in nature can mostly be appreciated in the long run (Tenaw and Beyene, 2021; Turner et al., 2021). In this context, there is a lack of study assessing this optimization issue faced by governments which can be filled by an analysis with the IWI framework (“Get Africa’s Great Green Wall back on track,” 2020).

Our analysis addresses this gap with an approach in two parts. First, we evaluate the historical performance of GGW nations compared to other African nations between 1992 and 2019 by measuring IWI in a sample of 40 countries. NC is estimated based on historical remote sensing data of land cover and ecosystem therein (Coulibaly and Managi, 2023; Zhang et al., 2021). We relied on Mirzabaev et al. (2022) study to value ecosystems in wetlands, grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, forests, and cropland concerning NC. HC was estimated by valuing the labor force based on their education level and current income, while PC was valued as the discounted worth of current infrastructure. Comparisons across countries are based on the average difference as well as a Synthetic Control Method (SCM).

Second, the analysis estimates the trajectory of growth in NC and IWI under two main scenarios and multiple complementary scenarios. The first scenario envisions nations reaching their goals of land restoration under the GGW initiative, while the second assumes they achieve half by 2030, the deadline of the initiative. Both scenarios account for the tradeoffs that investment in NC will have on PC and HC by accounting for the return on investment on these three types of capital. One set complementary scenario depicts IWI and NC outcomes in intermediary success rates of the initiative. Another set of sensitivity analyses projects growth in IWI and NC with varying mixes of tradeoffs concerning the funds that will be redirected from HC and PC.

The analyses reveal that investment in NC will enable sustainable development for all but two of the GGW nations and positive growth in their three types of capital, under a successful GGW initiative. This pattern contrasts with other nations, which will experience a decrease in NC but an increase in other types of capital and IWI. However, an emphasis on investment in NC under the GGW will slow down the IWI rate of growth for GGW countries. Therefore, financial assistance for the initiative will be paramount to ensure future economic growth in the GGW nations is not hampered.

The study provides two added values to the literature. First, like in previous studies (Mirzabaev et al., 2022; Turner et al., 2021), the study notes a historical reduction of natural land covers and cropland in GGW nations. However, the IWI approach shows that despite this decrease, renewable NC increases on average in these countries over time. It means that there is a conversion of land cover from a less to a more lucrative ecosystem. Second, the study shows that although investment under the GGW is profitable for countries, as mentioned in a previous study (Mirzabaev et al., 2022), investment in other types of capital is more lucrative. Therefore, there is an incentive for the government not to publicly fund the program.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: The second section briefly describes the GGW initiative. The third section presents the methodology used to estimate the IWI and to project the impact of the GGW on IWI. The fourth section portrays the results. Finally, the fifth and sixth sections introduce the discussion and conclusion of the analysis, respectively.

The GGW initiative

The GGW is an approach to ecosystem management for establishing a barrier of trees across Sahelian nations (O’Connor and Ford, 2014). This barrier will be 8000 km-long line of trees and plants from the Atlantic coast of Senegal to the east coast of Djibouti to stop desertification and create a buffer of green land in Africa (Turner et al., 2021). To this end, the initiative encompasses sustainable dryland management, habitat restoration, and the revitalization of natural vegetation and water retention systems (UNCCD, 2020). The project engages a diverse set of stakeholders, including national governments, international organizations, private entities, and civil society (Sacande et al., 2021). They collaborate under a Pan-African umbrella through government-determined plans, executed by local farmers, land users, municipalities, and local authorities.

The primary quantitative goal of the initiative is to restore 1 million km2 of degraded land in the Sahel and sequester 250 million tons of carbon by the year 2030. This goal also entails the training of stakeholders for roles such as rangers, nature guardians, and producers and vendors of non-timber forest products. This program plans to create 10 million jobs in rural areas. As of 2019, across these rubrics, governments estimated that actions taken under the GGW leadership enabled the restoration of 40,000 km2 and contributed to the production and/or seeding of 8 billion plants. They are also estimated to have garnered around USD 90 million, created more than 335,000 jobs, and trained around 900,000 farmers, land users, municipalities, and local governments on sustainable land management (SLM) since 2007 (UNCCD, 2020).

Yet, progress under GGW land restoration actions is still low since achievement rates range between 15% in Ethiopia and 0.1% in Djibouti as of 2019, despite large investment to be expected from pledges by the international community (see Table 1). Thus, motivations to internally finance the project is a factor determining its progress since national GGW funding is positively correlated with the achievement rate of land restoration (Pearson correlation = 0.0664 (p < 0.01)). However, governments of GGW nations face budget constraints and their nations are either lower-middle- or low-income countries, and investment in improving education, income, or infrastructure is much needed to improve HC and PC (Dieng, 2021). In this context, comparing the profitability of investment in NC against those in HC and PC to show that the GGW does not dwarf the resources necessary for development may bolster the incentive to invest in the GGW.

Methodology

The goal of the study is to estimate the net benefits of GGW if successful under its land restoration practices. The concept of IWI is instrumental in illustrating how redirecting investment from the HC and PC to the NC will affect nations involved in the initiative in terms of sustainability. The IWI is the sum of natural, produced, and human capital in monetary terms. In this framework, a nation can be considered sustainable if its IWI is not decreasing over time and it is unsustainable otherwise. In addition, a nation whose three forms of capital are not decreasing in time is classified as following a strong sustainability pattern. Therefore, the study estimates yearly IWI trends and capital types from 1992 to 2019 between nations involved in the GGW and others.

It also compares the growth in IWI and NC across nations while investigating simple differences in mean, and SCM statistical analyses. SCM is a statistical technique used to estimate the causal effect of a treatment or intervention on a unit by comparing its outcomes to a “synthetic control” group. This control group is a weighted average of other, untreated units in the data, designed to mimic the treated unit’s pre-treatment trends. The estimated impact is then the difference in outcomes between the treated unit and its synthetic control after the intervention (Coulibaly et al., 2022; Doudchenko and Imbens, 2016). Details on the SCM tests are presented in the Appendix Tables A1 and A2.

Then, it projects these trends up to 2030 to derive the implications of a successful initiative. Owing to data availability, GGW countries in our sample are limited to Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, and Djibouti.

Natural capital

Renewable natural capital

Renewable NC is the sum of the economic values of services provided to the populations by ecosystems in each country. The study uses the concept of shadow price to estimate these values. A shadow price is an estimated price of a good or service for which no market price exists. Shadow prices are collected from Mirzabaev et al. (2022). Their database reports the median economic benefits of the ecosystems based on the worth of their provisioning, regulating, habitat, and cultural services. Like this previous study, we focus on forests, woodlands and shrublands, grasslands, wetlands, and cropland ecosystems to estimate NC.

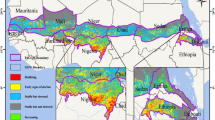

Estimates of ecosystem areas are measured by the ESA (European Space Agency) CCI (Climate Change Initiative) land cover product. It describes a land cover dataset at a 500 m2 resolution yearly. Using Coulibaly and Managi (2023) land cover types linked to ecosystems to estimate the total areas of each ecosystem, as described in Table 2.

Using the areas of ecosystems and their respective shadow prices, the renewable natural capital was estimated as follows:

where \({{RNC}}_{{ij}}\) is the renewable NC of the country i in year j that is the sum of values of the six types of ecosystems denoted by the index e. These values are estimated by multiplying \({{Area}}_{{iej}}\), the area of the ecosystem e, and Shadow pricee of the economic benefits of the ecosystem e.

Non-renewable natural capital

The scope of the research for non-renewable NC is restricted to fossil fuels owing to data unavailability in the mining sector in Africa (UNEP, 2023). Data on non-renewable NC about natural gas, oil, and coal reserves is collected from the (UNEP, 2023).

Human capital

HC was estimated as a function of educational attainment and the cumulative actualized sum of future employment compensation individuals may expect to earn in their lifetime. Estimation of the human capital can be presented as follows:

where HCij denotes the human capital of the country i at year j. The estimation of human capital is composed of three terms \({e}^{({A}_{{ij}}\cdot \rho )}\), \({P}_{{ij}{15}^{+}}\), and \({\int }_{0}^{{J}_{i}}{\bar{r}}_{i}\cdot {e}^{-\delta \cdot j}{dj}\). The term \({e}^{({A}_{{ij}}\cdot \rho )}\) represents the benefit of education to human capital. The component Aij is the average years of formal education, and ρ represents the average return of education on future wages, set to 8.5% based on (Managi and Kumar, 2018; UNU-IHDP and UNEP, 2014).

The term \({P}_{{ij}15-60}\) stands for the total working population. The population older than 15 years old and younger than 60 years old is used as a proxy for the working population. Finally, \({\int }_{0}^{{J}_{i}}\bar{{r}_{i}}\cdot {e}^{-\delta \cdot j}\) is the discounted sum of average income (\(\bar{{r}_{i}}\)) an individual may expect to earn in her lifetime (\({T}_{i}\)). Average income is multiplied by the discount rate of future earnings, \({e}^{-\delta \cdot j}\), where δ is the interest rate set at 8.5% following (Managi and Kumar, 2018).

The effective working lifetime, Ji, is the remaining working time per individual after 15 years of age. Following previous studies (Coulibaly and Managi, 2023), we set the average retirement age to 60 for all countries and defined Ji as follows:

The estimation described in Eq. (3) is separately applied for age groups 15–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, and 50–60 and then summed since populations in these age groups have different remaining working time. For each range, the median age is postulated to be the age of the population in that range (Coulibaly and Managi, 2023).

Produced capital

PC is estimated based on a perpetual inventory method (PIM). PIM suggests that PC in year j is equivalent to the value of capital in \(j-1\) plus the new investment on capital and minus depreciation of capital between j and \(j-1\). This method requires the valuation of the initial capital \({K}_{0}\) of each country.

The initial capital \({K}_{0}\) in each economy is estimated in a year where it is posited that the economy is in a steady state, that is, the capital-output ratio is constant in the long term (Cheng et al., 2022) as in the following equation:

where k is the capital-output ratio, I is investment; y is the output of the economy; γ is the steady-state growth rate of the economy; δ is the depreciation rate of the capital. Consistent with (Managi and Kumar, 2018), γ is estimated as a weighted average growth rate of the economy under study while δ is assumed to be 4% across countries and time. This steady state refers to a period where there is an assumed long-term equilibrium of the economy.

For each country, this ratio is then multiplied by the output (\({{GDP}}_{i0}\)) to estimate \({K}_{i0}\), the initial capital. The analysis uses values in 1970 as initial capital estimates consistent with previous estimation techniques (Managi and Kumar, 2018). Following the estimation of the initial capital, PIM can be applied as described here:

Finally, regarding the lifetimes of PC assets, we have assumed an indefinite depreciation period J. All data for this calculation come from (UNEP, 2023).

Projections

Projections are estimated up to 2030. For GGW nations, future wealth is estimated based on the land restoration goals and the achievements by countries, displayed in Table 1. The projections assumed that efforts of land restoration occur on bare land and consist of rehabilitation of ecosystems in wetlands, grasslands, shrublands, woodland, forest, and cropland, which are the main land cover targeted in afforestation projects (Liu et al., 2023; Mirzabaev et al., 2022). Thus, for every year between 2019 and 2030, we assume that countries convert the total area of bare land to areas of these six types equally as follows:

where \({{RL}}_{{iej}}\) is the restored land from bare land areas to the ecosystem e, made in year j and by country i. \({{RL}}_{{ij}}\) is the total area that country i has restored until the year j, and GGW area goali2030 is the total area that country i set as a goal of restoration.

Following this projection, NC is measured using the net present value approach:

where T is the planning horizon of the users of the ecosystems which is represented by the subtraction of year 2030 minus year j (j ranges between 2020 and 2030). ρ equals 1 + r, where r is the land user’s discount rate, set at 10 percent. Data on the benefit of restored ecosystems and the discount rate come from Mirzabaev et al. (2022).

During this same period, variations of HC, PC, and NC for countries not involved in the GGW are estimated under a business-as-usual scenario (BAU). The BAU uses the average growth rate of the respective capital between 1992 and 2019 to estimate future values. However, the projection considers that additional funding under the GGW stems from investments that could have been made in HC and PC in GGW countries. For simplicity, our analysis assumes that investment in NC under the GGW will be equally subtracted from HC and PC. We use the elasticity of public funding on HC and PC to estimate the opportunity cost that the GGW will cause them after applying the BAU.

The elasticity between HC and public spending on primary education is used as a proxy for the marginal rate of return on investment on HC. This elasticity is estimated with an ordinary least squares regression (OLS) and WBG data on education and government spending between 1992 and 2019. OLS results are presented in Table 3. As for PC, it is assumed that the return on investment on PC is equivalent to the elasticity between gross capital formation (GCFC) and PC estimated via an OLS (see Table 4). Then, the opportunity cost for HC and PC is valued as a sum of actualized expenses for GGW every year between 2020 and 2030 that are multiplied by the respective capital elasticities as follows:

where \({\triangle {HC}}_{i}\) and \({\triangle {PC}}_{i}\) represent the opportunity costs for HC and PC in the country i, with ∆ being the variation symbol. fHC () and fPC () are the functions converting investment to HC and PC estimated via OLS regressions, respectively. Cost GGWit is the cost necessary for rehabilitation of land covers estimated in Equation (6) in year t. The costs are composed of establishment costs, and maintenance costs of the restored ecosystem collected using scenario S9 of Mirzabaev et al. (2022). This scenario stipulates that the benefits of ecosystems from investment under the GGW are noticeable in the establishment years, and ecosystems restored have a survival rate of 0.6.

Finally, two sets of robustness checks are performed. First, it is useful to understand the implications of countries not reaching the full success of the initiative since less than 3% of the overall goal is achieved as of 2019. Therefore, we investigate scenarios where countries only achieve fractions of 10 s of their pledged goals for sensitivity analyses. In these robustness checks, the term GGW area goali is multiplied by the success rate of their goals before applying Equation (6) and implications for IWI and NC are estimated.

Second, we examine the sensitivity of our findings to assumptions regarding the sources of investment for NC restoration in a self-funded GGW scenario. The baseline assumes an equal reallocation of investment from HC and PC, as specified in Equations (8) and (9). Since this is a simplifying assumption, we explore alternative funding mixes, varying the proportion of redirected investment from HC and PC between 10% and 90%. This allows us to test whether our conclusions are robust to different resource allocation strategies.

Results

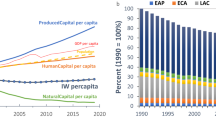

Composition of IWI in Africa

Figure 1 presents the evolution of Africa’s IWI from 1992 to 2019, shown as the cumulative sum of HC, PC, renewable NC, and non-renewable NC. Figure 2 reports the percentage contribution of each capital type to total IWI over time. During this period, Africa’s IWI increased from USD 211 billion in 1992 to USD 270 billion in 2019. This growth was primarily driven by a substantial rise in HC, from USD 113 billion to USD 267 billion, and an increase in PC from USD 4 billion to USD 12 billion. In contrast, renewable NC remained nearly stagnant at around USD 43 billion, while non-renewable NC declined slightly, from USD 50 billion to USD 47 billion. As a result of the rapid accumulation of HC, the composition of IWI in 2019 was dominated by HC (71%), followed by renewable NC (19%), non-renewable NC (6%), and PC (3%). Notably, the share of renewable NC in total wealth declined significantly from 31% in 1992 to 19% in 2019.

Country-level discrepancies in IWI

Figure 3 describes IWI and its composition by capital type in 2019. It describes the average IWI values of groups of countries based on participation in the GGW initiative in Panel A and the average values for each country in Panel B. Figure 3B highlights that there is a large discrepancy in wealth on the continent. South Africa, Egypt, Angola, Nigeria, and Algeria come out as the wealthiest African nations. Their IWI exceeds USD 1,000 billion. On the other side, the least wealthy states are Burundi, Lesotho, the Gambia, and Djibouti, with wealth lower than USD 20 billion.

Concerning the involvement in the GGW initiative, Fig. 3A reveals that GGW nations have an average IWI of USD 262.3 billion against USD 396.6 billion for non-GGW nations. The proportion of capital type is also different across countries participating in the initiative. Sahelian countries are composed of 41% of HC, 5% of PC, 9% of renewable NC, and 13% of non-renewable NC in 2019. Non-GGW nations have a population composed of 77% of HC, 3% of PC, 12% of renewable NC, and 8% for non-renewable NC in 2019. In sum, these figures show that there is a relatively low renewable NC density in GGW nations, and they are less wealthy on average, with Nigeria being the noticeable exception to this trend. In sum, the discrepancies displayed in Fig. 3A suggest that attributing the difference in mean variation in IWI and NC to actions taken under the GGW can be biased.

Historical capital variation between 1992 and 2019 presented in Fig. 4 also differs between GGW nations and others. Average growth of countries based on their participation in the GGW is presented in Fig. 4A, and average growth for each country is displayed in Panel B. For each observation presented in Fig. 4, the growth in PC, HC, and NC is shown as cumulative bars while IWI growth, which corresponds to the weighted average of the capital types is drawn inside the cumulative bars. Panel A of the plot shows that on average, IWI growth for GGW nations was 1.3% per year, against 3.11% for other African nations. However, nations involved in the initiative increased their renewable NC by an average of 0.1% unlike other countries, where NC declined by 0.06%. These figures may suggest a stronger effort by GGW countries to invest in their environment although they do not grow economically faster than other countries.

In panel B of Fig. 4, two important continental patterns emerge when assessing country-level IWI growth between 1992 and 2019. First, all African countries increased their IWI, with the lowest increase in the Central African Republic (CAR) with 0.2% growth and the highest in Djibouti with a 7.1% rise. Second, HC and PC were the main capital driving the positive growth of IWI in time. All African countries but CAR increased their PC and HC. On the other side, NC contracted in 19 countries out of the 40 countries in the sample. Burkina Faso and Chad are the only GGW nations in the sample to have a negative historical NC growth with 0.17% and 0.0023% declines, respectively.

Overall, historical growth in IWI highlights that GGW nations have slower IWI growth but faster NC growth than other African countries. Djibouti, a GGW nation, is the country with the fastest IWI increase, with a total increase of 7.1% per year, supported by growth in the three types of capital. However, CAR, Somalia, and Nigeria had the slowest IWI growth, with increases lower than 1% per year owing to the low increase in HC during this period and despite noticeable PC and renewable NC growth in all three countries.

Additional sensitivity analysis with historical data between 2007 (the beginning of the GGW initiative) and 2019 also supports the claim that IWI in non-GGW nations grew faster than that of GGW nations, but their NC increased less strongly than GGW nations. The SCM is used for this sensitivity analysis to account for inherent discrepancies between GGW countries and other African countries described in Fig. 3. The SCM uses observations of IWI, NC, GDP, and population before 2007 to create a synthetic control unit corresponding to a weighted average of non-GGW countries whose characteristics are the closest to GGW participants. Figure A1 in the Appendix shows estimates of NC by year and for GGW nations and their synthetic control unit. It highlights that the NC of GGW participants decreased at a pace slower than that of their synthetic counterfactuals after 2007. Figure A2 which displays the average IWI growth between GGW participants, and their control unit highlights that the IWI increase of the former is slower than the synthetic observation after 2007.

IWI Projection under the GGW initiative up to 2030

The results of the projection until 2030 are presented in Fig. 5 under the scenario that the GGW initiative enables the restoration of 156 million ha of land. Panel A of the Figure shows the average growth of countries based on their involvement in the GGW and the panel B shows growth for each country individually. In Panel A, the figure reveals that GGW countries will have an IWI growth of 1.1% against 2.9% for other countries. Their HC and PC are expected to grow by 1.4% and 3%, and renewable NC will expand by 3.1% for GGW nations. On the other hand, non-GGW nations will experience growth in HC, PC, and renewable NC by 3.4%, 7.6%, and 0.04%, respectively. Both groups of countries will experience a decrease in non-renewable NC. In sum, although the achievement of goals set for the initiative

Panel B reports that Djibouti, which is involved in the GGW initiative, will have the fastest IWI growth on the continent (5.3%). The IWI growth of all GGW nations includes an important increase in renewable NC. Thus, most of these countries follow a strong sustainable development whereby all forms of capital increase in time. Nevertheless, this projection shows that the performance of IWI growth in GGW nations will pale compared to the rest of Africa since they are at the bottom of the ranking of IWI growth. It shows that self-funding the initiative will cause important tradeoffs between NC and both HC and PC. The case of Niger and Burkina Faso is the direst. PC and HC will deplete in Niger and PC in Burkina Faso if the GGW initiative is self-funded by the countries.

Sensitivity analyses of the achievement rate of the GGW goals suggest that IWI in GGW nations is expected to grow at a slower pace with more advancement of the initiative, provided investment comes from funds that would have invested in potential HC and PC. In the sensitivity analysis using a scenario where countries achieve only half of their goals, the IWI of GGW countries will increase by 1.3% and so will NC by 1.7% on average, as presented in Fig. 6. HC and PC are estimated to increase by 2.3% and 3.7%, respectively. In this scenario, Niger and Burkina Faso do not experience a decrease in HC, while all GGW nations still increase their NC. More detailed investigations bolster the claim of faster IWI growth in case of low GGW achievement. Figure A3 in the Appendix depicts achievement rates varying between 10 to 90% by an increment of 10% bolster highlight faster IWI growth with lower achievement rate of the initiative.

The extreme case presented by a scenario in which ecosystems of GGW nations grow at their historical rate is also explored. This scenario suggests that the IWI growth of the GGW nations will be 1.8% and NC growth will be 0.1% on average (see Fig. 7). HC and PC will grow by 3.3% and 4.8% for these countries and will drive their IWI growth.

Another set of sensitivity analyses was conducted to identify the most effective mix of resources to fund the GGW initiative. The results suggest that relying heavily on HC investment to finance the program slows overall IWI growth the most. Specifically, the analyses examine scenarios where 10% to 90% of funding comes from HC investment, with the remainder coming from PC. This creates a range of HC-PC investment ratios from 90:10 to 10:90, as shown in Fig. A4 in the Appendix. The findings indicate that when 90% of the funding is diverted from HC investment, IWI grows by only 0.9% over the study period. In contrast, when 90% of the funding comes from PC, IWI grows by 1.4%. These trends remain consistent even under scenarios where the GGW is only partially completed (see Fig. A5 in the Appendix).

Overall, the sensitivity analyses suggest that GGW countries will achieve greater long-term wealth growth if they prioritize investment in human capital.

Discussions

In summary, the results provide three main implications. First, it underscores the important composition of wealth in Africa. In 2019, the main source of wealth on the continent is human capital, composing 71% of the IWI, while the second most valuable resource is the renewable NC, contributing 19% of the continental IWI. PC contributes to only 3% of this wealth. These results call for actions concerning the need for governments to monitor NC as meticulously as HC and PC, given its importance as a source of wealth. The prevailing reliance on traditional economic indicators such as GDP and HDI for policy analysis overlooks the critical role of NC while emphasizing factors about human and PC. It is imperative to incorporate the IWI and similar indices into policy to foster sustainable growth and ensure the protection of NC (Aly and Managi, 2018; Jingyu et al., 2020; Lange et al., 2018). These results also show an important lack of PC on the continent compared with other resources. Investment in PC is necessary to ensure the population can use the machinery to improve their productivity (Managi et al., 2024).

Second, the declining trend in renewable NC in 19 out of 40 countries highlights the urgency to invest in this vital resource. Figure 8 presents a more detailed analysis of the components of renewable NC, aiming to explain the causes of its depletion on the continent. These components are the different stocks of land covers used to value the ecosystems. The graph presents the growth of land cover and NC between 1992 and 2019 in all countries. There are mixed patterns for almost all countries in the variation of their NC, but most African countries decreased their surface area in forest, grassland, woodland, and shrubland. This contrasts with the fast expansion of cropland, which is positive in almost all African countries. Therefore, it is important to monitor the benefits of public natural land cover such as woodland and shrubland to ensure they increase or decrease in smaller proportions (Li et al., 2023). Particularly, previous studies have shown that Sahelian countries are experiencing a fast decrease in natural land cover. Although the data in Fig. 8 supports this concern and the need to address it, it also appears that all but two GGW countries in our sample increased their NC. A general increase in NC is driven by the expansion of croplands.

Third, our projections estimate that more than USD 76.1 billion will be required to fully implement the GGW initiative. The USD 14.3 billion pledged by the international community for the GGW Accelerator programs falls short of this target. Notably, our estimate exceeds previous projections, such as the USD 33 billion cited by UNCCD (2022). This higher figure may reflect the simplified assumption in our model, which distributes restoration efforts equally across six land cover types, despite likely variations in cost. The lack of specific targets, for each land cover from participating countries limits our potential for a more refined cost analysis.

Lastly, the results show that projects targeting NC growth are profitable but slow avenues for increasing a nation’s wealth. At a micro-scale, GGW support can increase income and reduce food insecurity in communities where it is implemented (Sacande et al., 2021). Thus, the low achievement rate in the GGW program per country in 2019 may underscore the challenges posed by security issues (O’Connor and Ford, 2014), political stability (Turner et al., 2023), armed conflicts (Gwaza and Akpan, 2022), and climate change (Oxford Analytica, 2022). Here, the results highlight that governments have an incentive to prioritize investment in HC and PC because it will lead to faster long-term development. It adds up to the challenge of meeting the ambitious goal of completing the GGW program by 2030. Hence, financial assistance will be required for countries to ensure the most efficient application of this program.

Conclusions

This study employs the IWI framework and diverse datasets for two objectives: First, it assesses Africa’s IWI; second, it quantifies the impact of the GGW initiative on the growth of NC and total wealth in participating countries by comparing their growth with that of non-participating countries. Regarding IWI estimation, there is fast growth from 1992 to 2019, with a valuation of USD 270 billion in 2019. This wealth is largely composed of NC, particularly its non-renewable component, standing by as much as 19% of the total wealth on the continent. However, there is a mismanagement of this resource across nations, with 19 out of 40 states experiencing a decline in this critical asset between 1992 and 2019. On the other side, all African countries expanded their human and PC. These results underscore the diligence for investment in HC and PC and a relative indifference concerning natural capital protection.

Regarding the impact of the GGW, historical data reveals a marginally higher growth of renewable NC in GGW nations compared with other African nations, as of 2019. However, GGW countries display an IWI growth lower than that of other countries during the same period. Our projections indicate that this initiative could boost renewable NC growth to an average of 3.6% if fully successful and 2.3% if half successful, compared to the historical 0.1% growth in NC. However, progress under the initiative will cause underperformance in terms of IWI growth if they use investment planned for HC and PC to fund this project. Therefore, foreign aid will be key to an effective implementation of the GGW while not slowing down long-term development.

Nevertheless, our study comports some limitations. First, benefits to local communities, countries, and the world are not differentiated in the analyses. This differentiation plays an important role in the implementation of the reforestation project since investors in the project are those who are the most interested in net benefits. This limit can cause difficulties in gathering these three types of stakeholders to discuss fair contributions of investment for the project. Second, we made several simplifications in the land cover that will be invested in. Further analyses are required with actual plans of restoration land per country to improve the accuracy of the interpretations. Moreover, our estimates of progress made during the project are measured with 2019 data. It obstructs the accounting of several events that occurred in the countries studied and the novel issues they face such as COVID-19. The lack of more recent data on the project limits our analyses in this context. Finally, it is important to note that these statistical analyses cannot ascertain the causal claim because efforts to decelerate desertification had started before the launch of the initiative. Therefore, endogeneity issues may persevere despite our use of the SCM. These shortcomings remain for future studies to address.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due permission right with agencies funding the research but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aly EA, Managi S (2018) Energy infrastructure and their impacts on societies’ capital assets: a hybrid simulation approach to inclusive wealth. Energy Policy 121:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.05.070

Barbier EB, Hochard JP (2018) Land degradation and poverty. Nat Sustain 1:623–631. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0155-4

Bilal B, Mehjabeen, Rafia J (2019) The investment-return-environment triangle in Cleaner Production projects. Sustain Prod Consum 19:161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2019.03.007

Cheng D, Xue Q, Hubacek K, Fan J, Shan Y, Zhou Y, Coffman DM, Managi S, Zhang X (2022) Inclusive wealth index measuring sustainable development potentials for Chinese cities. Glob Environ Change 72:102417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102417

Coulibaly T, Islam M, Managi S (2020) The impacts of climate change and natural disasters on agriculture in African countries. Econ Disaster Clim Chang 4:347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-019-00057-9

Coulibaly TY, Managi S (2023) Subnational administrative capabilities shape sustainable development in Africa. Environ Dev 100817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2023.100817

Coulibaly TY, Wakamatsu MT, Managi S (2022) The use of geographically weighted regression to improve information from satellite night light data in evaluating the economic effects of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Area Dev Policy 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2022.2030774

Dieng A (2021) The Sahel: challenges and opportunities. Int Rev Red Cross 103:765–779. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383122000339

Doudchenko N, Imbens G (2016) Balancing, regression, difference-in-differences and synthetic control methods: a synthesis. Cambridge, MA. https://doi.org/10.3386/w22791

Get Africa’s Great Green Wall back on track (2020) Nature 587:8–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03080-z

Gwaza PA, Akpan C (2022) Africa’s Great Green Wall and the challenges of peacebuilding in Nigeria. Arts Soc Sci Res 12:297–320

Jingyu W, Yuping B, Yihzong W, Zhihui L, Xiangzheng D, Islam M, Managi S (2020) Measuring inclusive wealth of China: advances in sustainable use of resources. J Environ Manag 264:110328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110328

Johnson JA, Baldos UL, Corong E, Hertel T, Polasky S, Cervigni R, Roxburgh T, Ruta G, Salemi C, Thakrar S (2023) Investing in nature can improve equity and economic returns. Proc Natl Acad Sci 120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2220401120

Lange G-M, Wodon Q, Carey K (2018) The changing wealth of nations 2018: building a sustainable future. World Bank, Washington DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1046-6

Li J, Xie B, Dong H, Zhou K, Zhang X (2023) The impact of urbanization on ecosystem services: both time and space are important to identify driving forces. J Environ Manag 347:119161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119161

Liu X, Ding J, Zhao W (2023) Divergent responses of ecosystem services to afforestation and grassland restoration in the Tibetan Plateau. J Environ Manag 344:118471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118471

Liu Y, Xue Y (2020) Expansion of the Sahara Desert and shrinking of frozen land of the Arctic. Sci Rep. 10:4109. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61085-0

Macia E, Allouche J, Sagna M, Diallo A, Boëtsch G, Guisse A, Sarr P, Cesaro J-D, Duboz P (2023) The Great Green Wall in Senegal: questioning the idea of acceleration through the conflicting temporalities of politics and nature among the Sahelian populations. Ecol Soc 28:art31. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-13937-280131

Managi S, Coulibaly TY, Chen S, Islam M, Kumar P (2024) Inclusive wealth Africa 2024 moving beyond GDP. Nairobi. Available at: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/43651 (Accessed: 02 May, 2025)

Managi S, Kumar P (2018) Inclusive wealth report 2018. Routledge, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351002080

Mbow C (2017) The Great Green Wall in the Sahel, in: Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.559

Mirzabaev A, Sacande M, Motlagh F, Shyrokaya A, Martucci A (2022) Economic efficiency and targeting of the African Great Green Wall. Nat Sustain 5:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00801-8

Nkonya E, Johnson T, Kwon HY, Edward K (2016) Economics of land degradation in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Economics of land degradation and improvement–a global assessment for sustainable development. Springer, Cham, pp 215–259

O’Connor D, Ford J (2014) Increasing the effectiveness of the “Great Green Wall” as an adaptation to the effects of climate change and desertification in the Sahel. Sustainability 6:7142–7154. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6107142

Oxford Analytica (2022) Africa’s Great Green Wall project may lose momentum. London

Sacande M, Parfondry M, Cicatiello C, Scarascia-Mugnozza G, Garba A, Olorunfemi PS, Diagne M, Martucci A (2021) Socio-economic impacts derived from large scale restoration in three Great Green Wall countries. J Rural Stud 87:160–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.09.021

Tenaw D, Beyene AD (2021) Environmental sustainability and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa: a modified EKC hypothesis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 143:110897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110897

Turner MD, Carney T, Lawler L, Reynolds J, Kelly L, Teague MS, Brottem L (2021) Environmental rehabilitation and the vulnerability of the poor: the case of the Great Green Wall. Land use policy 111:105750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105750

Turner MD, Davis DK, Yeh ET, Hiernaux P, Loizeaux ER, Fornof EM, Rice AM, Suiter AK (2023) Great Green Walls: hype, myth, and science. Annu Rev Environ Resour 48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-112321-111102

UNCCD (2022) Green Wall Accelerator. Great Green Wall Initiative Available at: https://www.unccd.int/our-work/ggwi/great-green-wall-accelerator. (Accessed: 02 May, 2025)

UNCCD (2020) The Great Green Wall implementation status and way ahead to 2030. Bonn, Germany, UNCCD Available at: https://www.unccd.int/resources/publications/great-green-wall-implementation-status-and-way-ahead-2030 (Accessed: 02 May, 2025)

UNEP (2023) Inclusive Wealth Report 2023. Nairobi, UNEP, Available at: https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43131 (Accessed: 02 May, 2025)

UNU-IHDP & UNEP (2014) Inclusive Wealth Report 2014—Measuring Progress Toward Sustainability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/inclusive-wealth-report (Accessed: 02 May, 2025)

Zhang B, Imbulana Arachchi J, Managi S (2024) Forest carbon removal potential and sustainable development in Japan. Sci Rep. 14:647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51308-z

Zhang B, Nozawa W, Managi S (2021) Spatial inequality of inclusive wealth in China and Japan. Econ Anal Policy 71:164–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2021.04.014

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: TYC, SM. Methodology: TYC, SM. Investigation: TYC. Visualization: TYC. Supervision: SM. Writing—TYC. Writing—review & editing: TYC, SM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study, which did not involve human participants, were conducted following the ethical standards of Kyushu University and the relevant national research committee. This research adheres to the ethical principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Since the study did not involve any procedures requiring ethical approval by an institutional review board, no specific protocol number was assigned.

Informed consent

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, no informed consent was required. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines and standards of the Urban Institute of Kyushu University and/or the relevant national research committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Coulibaly, T.Y., Managi, S. Valuing the Great Green Wall economic benefits with the Inclusive Wealth Index approach. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 935 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05221-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05221-z