Abstract

In contrast to the hesitant attitudes toward translation in imperial China, both the government and individuals in the Republic of China (1912–1949, ROC) recognized the critical importance of translation for the nation and society. This consensus is evidenced by the establishment of at least 86 translating institutions during the Republican Era. The emergence of these institutions brings translation planning to the fore. Based on González Núñez’s conception of translation policy, this study compares translation policies across governmental, semi-governmental and non-governmental institutions in the ROC through case analyses. The findings reveal that governmental institutions implemented strict translation policies aligned with state values, undertaking large-scale projects such as translating foreign academic books and standardizing terminology, in order to strengthen state authority and pursue strategic aims. Semi-governmental institutions, though primarily reliant on government funding, maintained considerable managerial autonomy and prioritized translating works in the humanities to introduce progressive Western ideas to conservative Chinese audiences. Non-governmental institutions, constrained by unstable funding, limited translators, and unclear regulations, mainly focused on single-book translations. Their translation practices, though the quality was inconsistent, still played a crucial role in promoting specific ideologies and advancing particular disciplines during this period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Republic of China (1912–1949) was the first democratic republic in Asia. Between the fall of the Qing Dynasty (the last imperial dynasty of China) and the founding of the People’s Republic of China (1949-present), this period was relatively unstable marked by “civil war, revolution and invasion”, and by change and growth in the economic, social and cultural aspects (Twitchett and Fairbank, 1983, p. 1). It witnessed an array of historic events that might decide or affect the nation’s survival: partisan conflicts between royalists and republicans, political frictions between the Nationalist Party and the Communist Party, frequent wars and uprisings like the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), and the dispute between classical Chinese ideas and modern Western ideas led by the New Culture Movement (1915–1923), etc. However, translation thrived during the complex historical conditions of the Republican era. Many Chinese intellectuals who had studied abroad engaged in translation, with a substantial portion of their work conducted within institutional settings. According to our research, 86 translating institutions were founded in the ROC, exerting a considerable influence on the then society. These institutions presented distinctive translation policies that distinguished them from their counterparts in previous and subsequent eras. The peculiar phenomenon raises the question: How was translation policy formulated and implemented in different translating institutions within the historical context?

Translating institutions or institutional translation has gained global attention since Brian Mossop (1988, p. 70) introduced the concept of “institution” into translation practice as a vital actor in the translation process and emphasized “the production of translations (by institutions in particular historical conditions)”. China has a long history of institutional translation, initially aimed at the dissemination of Buddhist scriptures and communication among ethnic groups, and later expanding to serve more diversified purposes. In recent years, several well-known cases have drawn scholarly attention from history studies to translation studies, such as the Sutra translation workshop (Gao and Ren, 2020), the Beijing Institute of Russian Language (Bugayevska, 2019), governmental translating institutions in the Yuan Dynasty (Gao and Moratto, 2022), Jiangnan Arsenal (Wright, 1998; Lung, 2016). However, little research has been conducted on translating institutions in the ROC. Building on González Núñez’s conception of translation policy as an analytical framework, this article first examines three representative cases to analyze translation policy within governmental, semi-governmental, and non-governmental institutions. It then expands the comparison by incorporating additional data from other translation institutions in the ROC.

Translating institutions and translation policy

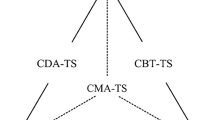

It is not easy to find a clear and consistent notion of “institution” in academic discourse (Kang, 2014). In the ROC, translations were usually conducted along with compilation, and translating institutions were often called Bian Yi She (compilation and translation agency), Bian Yi Guan (compilation and translation institute) or Bian Yi Ju (compilation and translation bureau). Here, Bian (编) referred to editing or compilation, and Yi (译) referred to translation. Therefore, this study defined institutional translation and translating institution in a broad sense where institutional translation encompasses “any translation that occurs in an institutional setting”, and consequently, a translating institution is “the institution that manages translation” (Schäffner et al., 2014, p. 493). This study systematically searched for translating institutions established in the ROC using the “Chinese Periodical Full-text Database” developed by the Shanghai Library (https://www.cnbksy.com), which encompasses approximately 10 million pieces of literature from about 20,000 periodicals published between 1911 and 1949. A total of 86 documented translating institutions were identified and classified into three categories based on the degree of governmental involvement. In this study, governmental translating institutions were initiated, patronized and managed by the central or local governments. These institutions operated entirely under government policies regarding text selection, source and target languages, translator recruitment, and translation processes. According to our statistics, 19 governmental translating institutions were established during the Republican Era, as shown in Table 1. Semi-governmental translating institutions are defined as those that were partially funded or governed by the government. These institutions maintained some degree of operational independence while adhering to certain governmental guidelines. Two such institutions in the ROC were China Foundation for the Promotion of Education and Culture (中华教育文化基金委员会, CFPEC, 1924–1949) and Sun Yat-sen Institute for Advancement of Culture and Education (中山文化教育馆, SIACE, 1933–1949). Non-governmental translating institutions were founded by individuals or private organizations. These institutions were financially and administratively independent of governmental influence. With the fall of the imperial Qing Dynasty, the government gradually deregulated private translating institutions, leading to the establishment of 65 non-governmental translating institutions during the Republican era, as shown in Table 2.

In a narrow definition, policies are “the conduct of political and public affairs by a government or an administration”, but in a broader sense policies encompass all institutional settings such as governmental agencies, international organizations, private companies, and even relatively informal situations where “a lack of policy may constitute a policy” (Meylaerts, 2011, p.163). In Language Studies, Spolsky (2004) distinguishes three related but independent components of language policy, namely, language practice, beliefs and management. Based on Spolsky’s influential definition, González Núñez (2016, p.103) proposes that translation policy is “a complex phenomenon that encompasses translation management, practice, and beliefs in any number of domains”. By gathering data from the “three components of policy” in a specific domain, “the researcher can approach policy systematically”. In his interpretation, translation management refers to the decisions made by people who have the authority to decide whether to use or not to use translation in a domain. Translation practice describes the actual practices regarding translation in a given community, involving such issues as what text and from which language to translate, what strategies to use, and when and where to do it. Translation beliefs are the beliefs about issues like “what the value is, or is not, of offering translation in certain contexts for certain groups or to achieve certain ends” (González Núñez, 2016, p. 90). González Núñez’s conception of translation policy has been recognized as a practical approach for studying translation policy in various domains (Li et al., 2017; González Núñez, 2019; Jiang and Ma, 2022). However, it primarily proposes that translation policy can be understood by “observing translation management, translation practice, and translation beliefs” (González Núñez, 2019, p. 778), without specifying particular factors to be examined. This lack of specificity poses certain challenges for analysis. To address this, this article develops a model of translation policy by incorporating specific factors that may reflect translation management, translation practice, and translation beliefs, which in turn shape translation policy, as outlined in Table 3. It is important to note that many factors can shape translation policy, and this framework is intended to provide entry points for analysis rather than to imply that translation policy is confined solely to these factors. Moreover, translation policies, both explicit and implicit, can be recorded in various forms, not only in laws and regulations but also in diaries, correspondence, manuscripts and even oral archives.

Translation policies in three representative institutions of the ROC

This section examines translation policies of three representative institutions: the National Institute for Compilation and Translation (国立编译馆, NICT, 1932–1949), the China Foundation for the Promotion of Education and Culture (中华教育文化基金委员会, CFPEC, 1924–1949), and the Fu Association (复社, 1937–1941). These institutions, selected from governmental, semi-governmental, and non-governmental bodies, were chosen for two reasons. First, historical consistency: All three operated during the 1930s, a period characterized by internal political consolidation under the Nationalist Government and escalating external threats from foreign aggression. Second, historical impact: Each institution has been recognized for its significant influence on Chinese history. NICT, as the highest translation authority under the Nationalist Government, established policies and standards that had long-term effects. CFPEC, a product of Sino-American political collaboration, facilitated the translation of Western works. The Fu Association, meanwhile, played a pivotal role in spreading Communist ideology, laying the foundation for the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

Governmental: National Institute for Compilation and Translation

In 1927, the Nationalist Government was established as the highest administrative authority during the Republican era, overseeing governments across the country. Subsequently, the Nationalist Government implemented a series of measures aimed at unifying leadership and advancing the ROC’s political, economic, cultural, military, diplomatic, educational, and judicial systems. A key prerequisite for progress in these areas was translation. To address this, the Nationalist Government established NICT in 1932, building upon the foundation of the Ministry of Education’s Compilation and Review Department. Xin Shuzhi (辛树帜), the then-director of the Compilation and Review Department, was appointed as the institute’s first director (NICT, 1934). NICT was mandated to adhere to the Ministry of Education’s directives on translation management, including stringent regulations for the recruitment, training and evaluation of translators. Most translators were directly appointed by the Ministry of Education, and any additional hires had to be proposed by the director and approved by the Ministry. Translators were required to work on-site daily and complete assigned tasks within set deadlines. A strict performance evaluation system was enforced, with supervisors regularly assessing employees on their work ethic, attendance, translation quality, and productivity. These evaluations had direct implications for salary adjustments and career progression. As a state-funded institution, NICT operated with a monthly budgetary allocation of roughly 13,500 yuan (or rather silver yuan 银元) from the central government treasury. (NICT, 1934, p. 28). This financial support enabled the institute to expand its staff, maintaining between 95 and 140 employees specialized in translation, editing, and review (NICT, 1947). As a result, NICT became the largest governmental translation institution in the ROC, with the capacity to handle large-scale translation projects. NICT’s translation efforts focused on three key areas: the standardization of terminology, the translation of foreign books, and the translation of Chinese classics into English.

In the Republican era, numerous Western concepts flooded into the ROC through various Chinese translations, but the chaotic translation impeded the promotion and reception of new terms, thereby undermining the government’s ability to regulate ideology (Zhu and Feng, 2023). In this circumstance, NICT was tasked with the unification of Western terminology. NICT first collected the English, French, German and Japanese versions of a new term, referred to its existing Chinese translations, and either selected one as the standard translation or created a new name if necessary. Then, experts appointed by the Ministry of Education formed a committee to review and revise these new terms, which were eventually submitted to the Ministry of Education for publication (NICT, 1940, p. 2). Our investigation shows that by 1946, NICT had translated a total of 93 categories of terminology, including Physics, Chemistry, Engineering, Medicine, Pharmacy, Geology, Zoology, Botany, Politics, Law, Economics, Management, Agriculture, Arts, Education, and Sociology. Each category encompassed nearly all newly introduced foreign terms of the time. For example, under the terminology of Politics, there were three sub-categories: 3474 terms on international relations, 3443 terms on government and administration, and 1454 terms on political ideology (NICT, 1946, p. 13). Building on this, NICT compiled terminology into dictionaries and encyclopedias, requiring translation institutions nationwide, particularly governmental ones, to use these as standard references to ensure consistency in translated terms.

For the Nationalist Government, education was a crucial tool for maintaining national governance. During the Republican era, a severe shortage of textbooks, especially in higher education, prompted NICT to translate significant foreign academic works to meet educational needs. Our statistics show that NICT translated 110 foreign books between 1932 and 1946 (NICT, 1936, 1940, 1946), whose source languages included English (75), Japanese (16), French (12), and German (7). This distribution reflects two points: 1) these countries served as China’s primary sources of learning during that period, and 2) the language proficiency of Chinese translators at the time, with English and Japanese being the most commonly chosen languages for translation and study. The books selected by NICT could be divided into three categories: (1) introductory or influential books in science and technology such as A. A. Michelson’s Studies in Optics and Gihei Yamaha’s Introduction to Cytology, aimed at accessing to cutting-edge technologies and advancing the development of specific disciplines; (2) essential books on the politics, economy, and diplomacy of foreign countries during the war, such as A. C. Pigou’s Political Economy of War, intended to enhance understanding of foreign national conditions; and (3) books on Chinese history, culture and minority groups that could assist in national governance, such as Torii Ryuzo’s A Survey of the Miao Nationality.

Another major focus of NICT was the translation of Chinese classics into English, a practice that was exceptionally rare during the wave of Western knowledge flowing into China at the time. NICT recognized the importance of cultural exchange, not only importing and learning from the West but also introducing China’s profound traditional culture to the world, in order to improve Western perceptions of China and counter stereotypes. Therefore, in the 1940s, NICT hired Yang Xianyi (杨宪益) and his wife Gladys Yang to translate Chinese classics into English, such as Shi Ji (Records of the Grand Historian), Zi Zhi Tong Jian (a chronicle recording Chinese history from 403 BC to 959 AD), The History of Chinese Culture, The History of Chinese Theater, etc. In 1946, NICT formally included the translation of Chinese classics in its work plan, stating, “Chinese culture is one of the world’s cultures. In addition to translating Western masterpieces, it is also necessary to translate important Chinese classics into Western languages to bridge the gap between the East and the West” (NICT, 1946, p. 11). This marked the earliest institutional translation of Chinese classics initiated and sponsored by the government.

NICT’s translation practices reflected the institution’s alignment with the Nationalist Government’s values and objectives. These practices were strategically designed to reinforce the government’s authority and advance its broader goals. The translation of foreign academic works served to introduce advanced Western technologies, promote academic progress, and strengthen national capacity. Efforts to standardize terminology aimed to resolve inconsistencies in translation, create a cohesive educational framework, and ensure ideological uniformity across disciplines. Meanwhile, the translation of Chinese classics into foreign languages sought to project a favorable cultural image of China on the international stage. Collectively, these initiatives were deeply intertwined with the government’s overarching strategies for national governance, nation-building, and cultural diplomacy.

Semi-governmental: Committee on Editing and Translation of CFPEC

CFPEC was established with the background of the remission of Boxer Rebellion Reparations paid to the United States by China (庚子退款). In 1924, the United States resolved to refund a total of $12,545,437 in principal and interest accumulated from 1917 to December 1940, to be paid over a twenty-year period (Wang, 1974, p. 305). That same year, China and the United States jointly established CFPEC to oversee the management of these funds. Although CFPEC was a political creation shaped by the collaboration of the Chinese and U.S. governments, it operated with substantial autonomy in its management and practice. In 1924, Paul Monroe, a CFPEC board member, emphasized that the fund originated from the Chinese and should therefore benefit the Chinese people. He proposed that CFPEC should have sole control over the funds, asserting that “the U.S. Government had no strings attached to it” (Yang, 1991, p. 75). Similarly, as the funds were derived from U.S. refunds, the Chinese government also maintained a relatively hands-off approach to CFPEC’s operations. By consensus, CFPEC decided to use the refund to develop science and education in China, and established the Committee on Editing and Translation (编译委员会) at CFPEC’s Sixth Annual Meeting in 1930, intended to translate and compile scientific textbooks for schools (CFPEC, 1931, p. 24).

While financially dependent on CFPEC, which in turn relied on annual appropriations from the Chinese and the U.S. government, the Committee operated independently in its management and practice. The Committee was chaired by Hu Shih (胡适), who was a doctoral student of Paul Monroe and a promoter of the New Culture Movement. Hu Shih personally invited 13 renowned translators, most of whom were university professors, to join the Committee. These translators were divided into two groups: one focused on translating works in the humanities (history, literature, and philosophy) and the other on scientific texts (primarily textbooks). Their duties included identifying translation projects, liaising with translators, and proofreading completed works. To attract talent, Hu Shih recruited intellectuals who had studied abroad by offering competitive remuneration. The Committee set translation rates at approximately five to ten yuan per thousand words, significantly higher than the average rate of two yuan per thousand words at the time (CFPEC, 1930, p. 51).

Having a big say in the Committee, Hu Shih (1994, pp. 362–369) formulated a package of translation policies on translation practice based on his preference, which were prominently reflected in the Translation Plan and the Translation Convention. First, Hu Shih believed that producing high-quality translations was far more valuable than creating mediocre original works. Consequently, he consistently advocated translating influential global classics over original writing or editing (Hu, 1918). Although the CFPEC established the Committee to focus on both translation and editing, Hu prioritized translation. Under his leadership, the Committee adopted the view that translation was more important than editing, leading to a shift in focus from editing to translating.

Second, Hu Shih emphasized the transformative power of modern Western ideas in reshaping the conservative mindset of the Chinese people (Zhu and Feng, 2024). He argued that “No matter whether it is an era or a country, we should choose the best historical, literary and ideological works that can represent that era or that country, so that we can have a clear understanding of the culture of that era or that country” (Hu, 1994, p. 362). Based on this vision, the Committee prioritized translating works in three main areas: world history, literary classics, and scientific textbooks. By the end of 1939, it had translated 182 books. As documented in The 14th Report of CFPEC, these included 64 scientific textbooks (encompassing physics, chemistry, and biology), 63 books in the humanities (encompassing history, geography, culture, philosophy, and art), and 55 literary classics (encompassing novels and dramas) (CFPEC, 1939). This indicates that while the Committee was originally established by CFPEC to focus on translating and editing scientific textbooks for schools, only one-third of its resources were ultimately dedicated to this purpose.

Third, Hu Shih (1918) believed that translation was an effective way to promote linguistic modernization, provided it adhered to “new standards”. To ensure this, Hu established specific translation requirements outlined in the Translation Convention: “(1) use the vernacular (白话文) in translation; (2) use new standard punctuation; (3) personal names and place names should be transliterated based on the national standard, providing the original text and a summary of transliteration for indexing at the same time; (4) add notes when it comes to obscurities; (5) the translation should render the author’s original intention, but also make it understandable; (6) translators should make best use of dictionaries, reference books and encyclopedias when translating in order to avoid mistranslation” (Hu, 1994, p. 369). Through the Translation Convention, we see Hu’s efforts to promote a translation standard according to his translation ideas. The most striking one was “using the vernacular in translation”. As a pioneer of the Vernacular Movement, a key component of the New Culture Movement, Hu Shih frequently criticized classical Chinese (文言文) and advocated writing in the vernacular on various public platforms (Zhu and Feng, 2024). Leveraging his authority within the Committee, he mandated that translators adopt the vernacular in their work. This requirement undeniably contributed to the widespread adoption of the vernacular in the Republic of China.

From the above analysis, it is evident that the Committee’s translation practices aligned closely with Hu Shih’s propositions but diverged from the original aims of the CFPEC. The Committee shifted its focus from editing to translating, prioritized the humanities and literature over scientific subjects, and adopted vernacular Chinese as the standard for translation. The translation beliefs of the Committee could be considered, to a large extent, as the translation beliefs of Hu Shih. Since Hu’s ideas embodied the intellectual ideals of the New Culture Movement, the Committee could be viewed as a practical field for advancing progressive ideas associated with the movement. However, it is important to note that despite the Committee’s relative autonomy in formulating and implementing its translation policies, it remained part of the CFPEC, which was supported by the United States. As a result, the Committee’s work was inevitably influenced by ideological biases. This was most evident in the overwhelming focus on Western culture, history, and literature in its translations, with minimal attention given to communism or Marxism.

Non-governmental: Fu Association

In 1937, Hu Yuzhi (胡愈之), a communist, initiated the Fu Association in Shanghai with a direct motive to translate and publish the American reporter Edgar Snow’s Red Star Over China, which recounted Snow’s experiences with the Chinese Red Army (the Communist Party) in 1936. In his later memoir, Hu (1956) described it as a budding socialist cooperative organized by a group of intellectuals who stayed in the Shanghai Concession in the Solitary Island Period (孤岛时期). The management and practice of the Fu Association can be found in two files: The Agreement of the Fu Association and Records of the First Annual Meeting (Feng, 1983, pp. 69–71). The Association was composed of no more than 30 members and their associates. Among the five executive members, there was a president, a secretary, an editorial director, a publication director, and a distribution director. Based on the member lists organized by some scholars (Liang, 2010; Xing, 2021), we found that most of the members were Hu Yuzhi’s comrades, friends and relatives, such as his brothers Hu Zhongchi (胡仲持) and Hu Huo (胡霍), rather than professional translators. All members volunteered their services without receiving any monetary compensation. Moreover, the Association relied heavily on member contributions to fund its activities, with each member required to pay a 50-yuan membership fee. At the First Annual Meeting held on April 1, 1939, there were about 20 members, raising around 1000 yuan in total as the start-up capital.

The Fu Association outlined three primary activities in The Agreement of the Fu Association: translating and publishing books, issuing periodicals, and collecting historical materials on the Sino-Japanese War (Feng, 1983, p. 69). However, the Association faced numerous challenges in wartime. After the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941 and the subsequent Japanese occupation of the concession area, the Association was forced to cease its activities. Due to its brief existence of less than four years, the Association managed to publish only two translated works—Edgar Snow’s Red Star Over China (1938) and Nym Wales’s Inside Red China (1939). This underscores the inherent instability of non-governmental institutions, particularly in terms of financial resources and operational security, when functioning in politically and militarily volatile environments.

Red Star Over China was the first and the most important translation practice by the Association. In the Translator’s Note of the first edition of Red Star Over China, Hu mentioned that “it is the first book to be published by readers themselves, organized and printed by themselves, and without any profit motive. This kind of publication by readers themselves was a risky experiment” (Hu, 1979, p. 140). The workflow adopted by the Association exemplified a collective, voluntary, and flexible approach, characterized by the absence of clear policy constraints. First, in view of his personal relationship with Hu Yuzhi, Edgar Snow transferred the copyright to the Association free of charge and provided additional photographs not included in the original edition (Liang, 2010). Then Hu enlisted 12 comrades from the “Tuesday Symposium”—a weekly gathering of intellectuals in Shanghai discussing anti-Japanese propaganda—to collaborate on the translation (Hu, 1979). For publishing, the Association, facing a lack of funds, negotiated with the publisher to print the book first and defer the printing fees until after sales. Simultaneously, the Association raised funds by selling book coupons at the Tuesday Symposium for one yuan each, allowing interested buyers to pre-register and pay in advance. For distribution, the Association employed several covert methods to sell the book. Copies were sold by reservation through book coupons issued at the Tuesday Symposium, at the Shanghai Social Science Seminar led by the Communist Party, and at the Yamei Bookstore, a Communist-affiliated outlet where it was categorized as an in-house publication. Additionally, copies were distributed under the guise of foreign merchants (Hu, 1956; Hu, 1984). Building on the experience of translating Red Star Over China, the Association went on to translate and publish Inside Red China by Nym Wales (Edgar Snow’s wife) in 1939. This project also adopted a collective translation model, engaging eight volunteer translators and employing covert sales methods.

The workflow involved in translating these two books reveals that the Fu Association lacked standardized procedures for book selection, translator recruitment, and translation guidelines. First, the decision to translate Edgar Snow’s book was purely incidental—Hu Yuzhi, a friend of Snow, happened to come across the newly published Red Star Over China at Snow’s residence in Shanghai, and believed that the book should be translated into Chinese to let more Chinese people know about the anti-Japanese activities of the Communist Party (Hu, 1979: p. 137). Similarly, the decision to translate Nym Wales’s book was driven by the fact that she was Snow’s wife. Second, the Fu Association did not select translators based on their expertise or knowledge. Instead, the task was assigned to comrades attending anti-Japanese propaganda meetings among intellectuals in Shanghai. Lastly, the Association did not establish clear translation principles or methods. For example, no guidelines were set regarding whether to adopt a literal or free translation approach, how to handle terminology, or how to ensure stylistic consistency across multiple translators. However, given the political climate, where the Communists faced suppression by both the Nationalists and the Japanese, the Association adopted some strategic methods to evade strict censorship. For example, the translators could not literally translate the titles Red Star Over China and Inside Red China because “Red” explicitly indicated that the books supported the Communist Party. Therefore, the Association chose more cryptic renderings “西行漫记” and “续西行漫记”, literally meaning “Records on Western China” and “A Sequel to Records on Western China”, respectively.

Ideologically, the Fu Association was more than just a translation and publishing house. It functioned as a vital part of the left-wing propaganda network. The members were ideologically aligned with the Communist Party, and their translation activities focused on themes related to the Sino-Japanese War and the promotion of Communist ideology. The translation of Red Star Over China was a landmark achievement. It became a sensation upon publication, with four reprints within a year and further editions released in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia (Liang, 2010). Inspired by the book, many young people were motivated to join the Communist Party and its revolution (Hu, 1979).

Comparison of translation policies in governmental, semi-governmental and non-governmental institutions in the ROC

The above analysis reveals that NICT, as the highest governmental translating institution, implemented strict policies on translators and translations, explicitly aiming at reinforcing national control. CFPEC, a semi-governmental institution jointly initiated and funded by the Chinese and U.S. governments, adopted flexible translation policies strongly influenced by Hu Shih’s personal style, reflecting the ideals of the New Culture Movement. In contrast, the Fu Association, a covert socialist translation organization, relied on collaborative and voluntary management and practices, operating without standardized procedures. To further illustrate the similarities and differences in translation policies during the ROC period, this section highlights key features of translation policies across governmental, semi-governmental, and non-governmental settings, drawing on additional data from the 86 identified translating institutions, as summarized in Table 4.

Translation management in the ROC was similar between governmental and semi-governmental institutions, but quite different in non-governmental institutions. Regarding the initiator, governmental and semi-governmental institutions were initiated by the central and local governments, or by individuals with a governmental background. In contrast, non-governmental institutions were usually initiated by well-educated and socially influential individuals, such as publishers, politicians, educators, and activists. These figures recognized translation as a powerful tool for challenging stereotypical Chinese ideas and revitalizing the nation by drawing inspiration from the West. Therefore, they proposed to set up translation institutions across the country. For instance, in 1919, scholars in Tianjin noted that educational methods were evolving rapidly worldwide. They expressed concern that despite China’s long-term efforts in educational reform, significant progress remained lacking. Thus, Li Jinzao (李金藻), the head of the Tianjin Academic Community, founded the Education and Academic Compilation and Translation Agency to translate, compile and issue publications for schools.Footnote 1 Regarding patronage, governmental and semi-governmental translating institutions had stable financial support from the government treasury on a monthly or yearly basis, which allowed them to offer more generous remuneration to their staff. For example, NICT, CFPEC and SIACE received considerable patronage from the central and local governments and offered an average remuneration of 5–10 yuan per thousand words to their translators and reviewers. However, non-governmental institutions struggled to find a stable patron, and they often relied on collective funding and book sales to raise capital. As a result, their translators could only receive an average remuneration of 2 yuan per thousand words or even work for free. Regarding organization, governmental and semi-governmental institutions consisted of several departments, including translation, reviewing, and publishing, and each department played its own role. On the other hand, members of non-governmental institutions often took on multiple roles, such as translating, editing, revising and organizing, resulting in a disordered management. Regarding translators, the translators of governmental and semi-governmental institutions were close to modern professional translators. They were hired through examination and authorized by the government. As full-time translators, they had fixed wages and working hours, regular training and assessment from the institution. For example, the translators and editors of SIACE should abide by the following rules: “(1) work on time every day and abide by all disciplines; (2) except for specific tasks, a daily translation of 1600 words is required, and be ready to prepare journal materials or review incoming manuscripts at any time; (3) the translation shall be submitted to the director for review and registration every week; (4) one must take on the responsibility of the final proofreading before printing for the manuscripts translated or edited by him or her (SIACE, 1935, p. 86). On the contrary, the translators from non-governmental institutions were often amateur or part-time translators lacking systematic training. Many of them were acquaintances, friends, or relatives of the initiators, and therefore their qualifications could not always be assured. The varying translation management led to differing outcomes for translation institutions. Governmental and semi-governmental institutions, such as NICT, CFPEC, and SIACE, were able to sustain operations for over a decade. In contrast, many non-governmental translation institutions, plagued by funding shortages and poor management, were forced to shut down during the wartime turmoil of the 1930s.

Translation practice reflects the translation policy in a concrete manner. The three types of translating institutions in the ROC had similarities in the direction of translation. Both the Chinese government and the Chinese people were curious about the West and eager to learn about and from it through translation. Therefore, the general direction of translation in the ROC was from foreign languages to Chinese. The two most common source languages in institutional translation were English and Japanese, as the government had sponsored some teenagers studying abroad in Japan and English-speaking countries like the U.K. and the U.S. during the late Qing Dynasty. However, it is worth noting that governmental institutions also undertook Chinese-to-English translation as well as mutual translation between Chinese and minority languages for political purposes. Differences mainly showed in translation projects, text selection, and the translation process. Regarding translation projects, governmental and semi-governmental institutions tended to undertake large-scale translation projects, such as the unification of terminology, the editing and translation of textbooks, and the translation of book series. In contrast, non-governmental institutions tended to carry out low-cost translation practices, such as translating single books, and had to carefully consider the social and economic impact of their translations. Regarding text selection, governmental institutions prioritized materials aligned with national interests, focusing on influential academic works in science and technology. In contrast, semi-governmental and non-government institutions emphasized translating works in the humanities and literature over those in science and technology. Statistical analysis shows that CFPEC translated at least 182 Western books, of which 118 were related to the humanities and literature (CFPEC, 1939). SIACE translated a minimum of 56 Western books, with 50 falling into the humanities category (SIACE, 1943). Regarding the translation process, governmental and semi-governmental institutions formulated policies outlining when, where, and how translation should occur. Translators were required to follow prescribed guidelines, such as specified translation strategies and methods. By contrast, most non-governmental institutions lacked specific regulations governing the translation process, resulting in inconsistent translation quality.

Translation beliefs reflect the values a translating institution embraces and largely determine its translation practices and management (González Núñez, 2016). The translation beliefs of the three types of institutions differ markedly. The primary intention of governmental translating institutions was to reinforce political control over the country. Consequently, these institutions were often located in the central government’s seat, such as Nanjing, or in key regions like Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, where ethnic minorities were concentrated. They were responsible for developing translation policies related to book translations and terminology standardization across Chinese, foreign languages, and ethnic minority languages. Compared to governmental institutions, the managers of semi-governmental institutions wield significant influence, as a result of which their translation beliefs often shape the institution’s overall translation practice. Both semi-governmental institutions shared the goal of disseminating progressive Western ideas, focusing on translating influential global classics to enlighten the conservative Chinese audience. The intention of non-governmental institutions was driven by the initiator’s specific intentions, such as spreading certain ideologies or advancing particular disciplines. Prior to the Sino-Japanese War, most non-governmental institutions aimed at reconstructing the ROC from various aspects. For example, in 1914, a group of students who had studied in Japan established the Shi Ye Compilation and Translation Agency in Shanghai to offer commercial translation services for businesses and individuals. It compiled a ten-volume series titled Banking Lectures (银行讲义), which included topics such as Banking Operations, Foreign Exchange and Banking English. Similarly, the Shao Wen Compilation and Translation Agency, the Law Faculty Compilation and Translation Agency of Soochow University, and the Law Compilation and Translation Agency focused on translating law books, and publishing law-related periodicals, in order to advance the development of ROC’s legal system. However, during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the concurrent civil conflict between the Nationalist and Communist parties, nearly all non-governmental institutions were established either out of personal commitment to national salvation or as vehicles for political propaganda. For the former, their primary objective was to inspire the Chinese people to resist foreign aggression through translation efforts. For example, in 1931, following Japan’s invasion of Northeast China, Ma Xiangbo (马湘伯) established the Northeast Culture Compilation and Translation Agency with the aim of raising awareness among the Chinese about the wealth and dangers of the Northeast and encouraging them to fight against the enemy. Its work involved translating Japanese and Russian books on Northeastern issues and editing textbooks on Northeastern history and geography for schools.Footnote 2 For the latter, their primary objective was to promote specific ideologies, exemplified by the efforts of the Fu Association and the Wartime Reading Compilation and Translation Agency to disseminate Communist thought. They focused on translating works about Marxism, the Soviet Union, and the Communist Party. However, their translation activities were often carried out in secret due to the political sensitivity of their content.

Conclusion

Compared with the hesitating attitudes towards translation in imperial China, translating institutions in the ROC reached a consensus that translation was highly necessary for the nation and the society, and thus translation planning became one of the major tasks of the ROC. To consolidate political control over the country, the authorities actively established governmental translation institutions in both central and minority areas. These institutions were responsible for developing translation policies related to book translations and terminology standardization across Chinese, foreign languages, and ethnic minority languages. Meanwhile, the growing societal demand for translation prompted the government to relax restrictions on private translation, leading to a surge in non-governmental translation institutions. Most of these institutions aimed to advance specific disciplines or promote particular ideologies through translation. However, due to limited funding and a shortage of translators, they typically focused on single-book translations. Members often assumed multiple roles—translators, editors, revisers, and organizers—resulting in organizational inefficiencies and inconsistent translation quality. Semi-governmental translating institutions represented an early endeavor towards public-private partnership. While financially dependent on the government, semi-governmental institutions operated independently in their management and practices, and their translation policies were often influenced by their administrators’ beliefs. Supported by considerably stable government funding, they translated many Western works on the humanities and literature to introduce progressive Western ideas to a conservative Chinese audience. In summary, although translation policies in the ROC demonstrated immaturity, they played a constructive role in facilitating cultural exchange, promoting educational development, and accelerating technological progress during the transition from imperial China to modern China.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Notes

For detailed information, see the article Official Document on Granting Record-filing Approval to the Education and Academic Compilation and Translation Agency by the Governor of Zhili Province 咨直隶省长教育学术编译社准予备案文 (1919) published in Education Bulletin 教育公报, 6(5), p. 66–68.

For detailed information, see the article Ma Xiangbo and others initiated the organization of the Northeast Culture Translation Society 马相伯等发起组织东北文化编译社 published in Shen Bao 申报, June 15, 1931, p. 10.

References

Bugayevska K (2019) The Beijing institute of Russian language and translation of Russian literature in 20th century China. Asia Pac Transl Intercult Stud 6(1):46–63

CFPEC (1930) The 5th Report of CFPEC中华教育文化基金董事会第五次报告 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=09003865&source=card

CFPEC (1931) The 6th Report of CFPEC中华教育文化基金董事会第六次报告 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=51020216&source=card

CFPEC (1939) The 14th Report of CFPEC中华教育文化基金董事会第十四次报告 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=51020172&source=card

Feng S (1983) Two pieces of material of the Fu association. Hist Arch 3(4):69–71

Gao Y, Ren D (2020) Origin of state translation program in China. Transl Q 95:1–10

Gao Y, Moratto R (2022) Governance-oriented state translation program in the Yuan Dynasty. Translator 28(3):308–326

González Núñez G (2016) On translation policy. Target 28(1):87–109

González Núñez G (2019) The shape of translation policy: a comparison of policy determinants in Bangor and Brownsville. Meta 64(3):776–793

Hu D (1984) The Fu Association and Hu Zhongchi. In: Institute of Literature of Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences (ed.) Memoirs of literature in the solitary island period of Shanghai. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing. pp. 54–65

Hu S (1918) A constructive revolution in literature. Xin Qing Nian 4(4):305–306

Hu S (1994) Translation plan and translation convention. In: Geng Y (ed.) Hu Shih’s manuscripts and letters, vol. 13. Huang Shan Publisher, Hefei. pp. 362–369

Hu Y (1979) On the translation and publication of Journey to the West. Dushu 1(1):135–141

Hu Z (1956) The memory of 1938. People’s Daily (1956-10-11)

Jiang J, Ma H (2022) Book translation policy of China Foreign Languages Bureau from 1949 to 1999: a historical and bibliometric perspective. Perspectives 30(5):760–775

Kang J-H (2014) Institutions translated: discourse, identity and power in institutional mediation. Perspectives 22(4):469–478

Li S, Qian D, Meylaerts R (2017) China’s minority language translation policies (1949–present). Perspectives 25(4):540–555

Liang Z (2010) Translation, culture and revival—a special translation institute “Fu Association” in the Solitary Island Period of Shanghai. Shanghai J Transl 102(1):66–69

Lung R (2016) The Jiangnan Arsenal: a microcosm of translation and ideological transformation in 19th-century China. Meta 61:37–52

Meylaerts R (2011) Translation policy. In Gambier Y, Van Doorslaer L (eds.), Handbook of translation studies, vol. 2. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. pp. 163–168

Mossop B (1988) Translating institutions: a missing factor in translation theory. Trad Terminol Edac 1(2):65–71

NICT (1936) Catalogue of Books Published by NICT 国立编译馆出版书籍目录 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=11107820&source=card

NICT (1934) A General Report of the NICT国立编译馆一览 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=09002875&source=card

NICT (1940) Overview of the Work of NICT in 1940国立编译馆工作概况 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=03005929&source=card

NICT (1946) Overview of the Work of NICT in 1946国立编译馆工作概况 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=16002284&source=card

NICT (1947) Regulations on the Organization of NICT in 1947 https://zh.m.wikisource.org/wiki/国立编译馆组织条例

Schäffner C, Tcaciuc LS, Tesseur W (2014) Translation practices in political institutions: a comparison of national, supranational, and non-governmental organisations. Perspectives 22(4):493–510

SIACE (1935) Special Issue of the Second Anniversary of the Establishment of SIACE中山文化教育馆成立二周年新馆落成纪念刊 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=09014400&source=card

SIACE (1943) The Ten-Year Work Overview of SIACE 中山文化教育馆十年工作概况 http://cadal.edu.cn/cardpage/bookCardPage?ssno=16003253&source=card

Snow E (1938) Red Star over China. Translated by Changqing W, Danqiu L, Zhongyi C, Yuwu Z, Jingsong W, Zhongzhi H, Da X, Donghua F, Zonghan S, Wenzhou N, Yi M, Binfu F. Fu Association, Shanghai

Spolsky B (2004) Language policy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Twitchett DC, Fairbank JK (eds.) (1983) The Cambridge History of China. vol. 12: Republican China 1912–1949. Part 1. Cambridge University Press, New York and Cambridge

Wales N (1939) Inside Red China. Translated by Zhongchi H, Binfu F, Mo L, Dichen X, Sixun K, Yi M, Danqiu L, Huo H. Fu Association, Shanghai

Wang S (1974) Gengzi compensation. Institute of Modern History of Academia Sinica, Taipei

Wright D (1998) The translation of modern western science in nineteenth-century China, 1840-1895. Isis 89(4):653–673

Xing K (2021) On the Fu association during the isolated island period of Shanghai. Res Hist Publ China 25(3):27–48

Yang C (1991) Patronage of sciences: the China Foundation for the Promotion of Education and Culture. Institute of Modern History of Academic Sinica, Taipei

Zhu H, Feng Q (2023) A historical study of the activities and good practices of National Institute for Compilation and Translation. Foreign Lang Cult 7(2):76–87

Zhu H, Feng Q (2024) Patronage and contribution to the translation enterprise in the Republic of China by the committee on editing and translation of CFPEC. Foreign Stud 12(3):89–110

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hanxi Zhu (first author) designed the research and drafted the manuscript. Quangong Feng (corresponding author) provided guidance throughout the process, reviewed the content, and refined the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, H., Feng, Q. Translation policies in the Republic of China (1912–1949): a comparative study of governmental, semi-governmental, and non-governmental translating institutions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1472 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05328-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05328-3