Abstract

Over the past decade, a significant body of research has focused on problematic smartphone use and smartphone addiction among children and adolescents. Much of this research focuses on the negative consequences of smartphone use. Still, it assumes universal adoption of this technology without questioning the age of acquisition or without paying attention to the determinants of early smartphone ownership. Through a systematic review of 1053 scientific publications, a gap in the existing literature was identified: only 14 studies (1.3%) address the topic of smartphone ownership in children and adolescents—some of them identifying it as a predictor of future problematic smartphone use—and among them, only 8 of these studies (0.8%) explore the factors associated with early smartphone ownership, covering a population of n = 12,912 individuals. According to the results of this review, at least four factors emerge as relevant to understanding early smartphone ownership: peer pressure combined with fear of social exclusion, household characteristics (having multiple children, parental separation, free internet access at home, the use of electronic devices during meals, parental age, and parental education level), perceived adolescent’s maturity and parental concerns about safety and location. Other factors that may have an impact but need to be further explored are: gender differences and trust in tools to control use. Despite these identified factors, more research is needed to better understand their mixed relationships and their precise influence on parents’ choices. Our research highlights the need to expand the study of Early Smartphone Ownership as a research category. A deeper understanding of this issue is crucial to inform the policy debates currently taking place in many countries, as well as to guide parental strategies in building a new social consensus around smartphones and childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread use of smartphones in children’s and adolescents’ lives has sparked growing concern and debate around the world. As digital technologies become increasingly integrated into daily life, they shape the well-being and development of younger generations, raising critical questions about the balance between benefits and potential harms. Over the past decade, a significant body of research on digital addiction has emerged in psychology, psychiatry, sociology, and communication studies, highlighting the detrimental effects of problematic smartphone use (PSU) and smartphone addiction (SA) (Fischer-Grote et al., 2019; Karakose et al., 2022; Kumcagiz, 2019). However, it is important to examine not only the risks and potential harms but also how smartphone use (SU) intersects with children’s social, emotional, and cognitive development.

The prevalence of PSU and SA among children and adolescents varies widely across regions and contexts, underscoring the global scope of this issue. Global estimates suggest that approximately 27% of individuals across 64 countries exhibit symptoms of SA, with higher rates among youth populations (Meng et al., 2022), while PSU affects 37.1% of individuals globally (Lu et al., 2024). Additionally, a meta-analysis also suggests that 25% of children and adolescent smartphone users show signs of PSU (Sohn et al., 2019). National studies show regional disparities: in Iran, 29.8% of adolescents aged 10–15 meet SA criteria (Azizi et al., 2024), while PSU rates in India reach 79.1% among adolescents (Ganesamoorthy et al., 2024). In Europe, SA prevalence reaches 16.9% in Switzerland (Haug et al., 2015) and 17.19% in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Tomczyk et al., 2024); in Spain, 94.8% of adolescents in secondary education own a smartphone (INE, 2023), with 82.1% receiving it before age 12 despite 61.7% of parents considering 16 the ideal age (Adolescència Lliure de Mòbils, 2024); in Italy, almost 30% of children aged 2–14 own a smartphone, rising to 68.1% among those aged 10–14 (Cerimoniale et al., 2023); and in Greece, over 80% of children under two are exposed to SU (Papadakis et al., 2022). In the United States, smartphone ownership rose sharply: from 45% to 78% between 2004 and 2012 (Lenhart 2009; Madden et al., 2013), and among adolescents aged 12–17, access or ownership increased from 23% in 2011 to 95% in 2018 (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Madden et al., 2013). By 2018, smartphone ownership was described as nearly universal among teens of all genders, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds (Anderson & Jiang, 2018), and nearly half of children aged 10 to 12 already owned a smartphone (Nielsen, 2017).

These patterns of early exposure reflect a broader shift in digital engagement among younger populations. To illustrate this, in 2010 only 5% of 9- to 16-year-olds accessed the internet via smartphones, compared to over 80% in 2020 (Livingstone et al., 2011; Smahel et al., 2020). In the United States, 45% of adolescents aged 13 to 17 report being online “almost constantly,” and an additional 44% connect several times a day (Anderson & Jiang, 2018), highlighting the increasing normalisation of constant connectivity during key developmental stages. Combined with the globally documented rise in screen time (Harvey et al., 2022), these figures underscore a profound transformation in how children and adolescents interact with digital technology.

Current research focuses primarily on the consequences of SU/PSU/SA, and it’s quite extensive. These include mental health risks and reduced overall well-being (Ahmed et al., 2023; Brodersen et al., 2022), sleep disturbances (Martínez-Estévez et al., 2024), behavioural problems (Setiadi et al., 2019), and emotional conditions such as increased fear of missing out (Adelhardt et al., 2018), nomophobia (Safaria et al., 2024), and lower self-esteem (Khalaf et al., 2023). Social consequences are also prominent, including loneliness (Amran et al., 2024) and weakened face-to-face relationships—also referred to as peer phubbing (Li et al., 2023)—as well as a documented decline in the quality of parent–child relationships (Yue et al., 2022). In the academic sphere, smartphone overuse has been linked to lower academic performance (Kumcagiz, 2019), with some evidence also suggesting a negative impact on the development of digital competence (Gerosa et al., 2024), contrary to common assumptions about its educational benefits. Excessive SU has also been associated with decreased physical activity (Jeong et al., 2023). In addition, studies report increased exposure to cyberbullying (Ban & Kim, 2024) and to inappropriate content (Terras & Ramsay, 2016), such as pornography, violent material, or hate-promoting content.

However, to effectively address these negative outcomes, it is crucial to understand their underlying causes. Yet much less attention has been paid to the underlying factors that lead parents to give smartphones to their children (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2024), leaving policymakers and families with few tools to address early exposure. But parents aren’t solely responsible for children’s digital behaviours: as Shin (2024) highlights, smartphone use is intentionally conditioned through recommendation algorithms, social media notifications, and autoplay functions that reward habitual engagement rather than promoting well-being. Due to immature impulse control, young users—especially early adopters—are more vulnerable to these mechanisms.

Meanwhile, social movements advocating smartphone restrictions for children have emerged worldwide (Bhaimiya, 2024), responding to concerns about what Jonathan Haidt (2024) calls a “phone-based childhood.” These movements seek either a ban (Knop & Hefner, 2018) or improved digital relationships (Livingstone et al., 2020). Despite these efforts, the appropriate age for smartphone introduction remains in debate. Some advocate delaying ownership until 16 due to cognitive and emotional immaturity and smartphones’ addictive design (Bae, 2015; Hwang & Jeong, 2015), while others see this as a moral panic, emphasising digital literacy instead (Terras & Ramsay, 2016). A balanced approach may involve both safeguarding against harm and ensuring digital opportunities for children.

In this context, there is a growing societal demand for better regulation of digital technologies. People are asking an important yet unanswered question: At what age can a child safely own a smartphone without significant risks? Applying the precautionary principle (Quintana et al., 2023), if observed harms outweigh benefits, delaying access may be necessary. However, recent scientific literature has focused primarily on exploring the consequences of SU/PSU/SA, with little attention paid to the factors driving early smartphone adoption (Blair & Fletcher, 2011; Cerimoniale et al., 2023). Why have smartphones become universally adopted, regardless of age? Why do parents provide them so early? If negative outcomes such as SA or PSU are observed, should we not also consider the factors that led to smartphone adoption in the first place? Our study will show that few studies approach the phenomenon from this perspective. That’s why we propose to focus our analysis on Early Smartphone Ownership (ESO), referring to the premature acquisition of smartphones by children and adolescents, a condition that may contribute to the development of PSU or SA.

Although the concept of ESO has not yet been theorised explicitly, some of its core dimensions—such as parental decision-making, peer dynamics, and developmental readiness—can be tentatively situated within broader psychological and social theories. For example, Social Learning Theory (Bandura & Walters, 1977) offers a general framework to understand how behaviours are acquired through observation and imitation within close social environments. Similarly, the Self-Regulation Theory (Baumeister & Heatherton, 1996) emphasises the role of executive functioning in behavioural control—an ability that is still developing during childhood and early adolescence. Digital Habit Formation Models (Lally et al., 2010) also provide insight into how repeated, reinforced digital interactions can gradually establish automatic usage patterns (Shin, 2024). Finally, Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) emphasises how individual behaviours are embedded in and shaped by broader familial, educational, and sociocultural contexts.

This paper presents a systematic review aimed at identifying what portion of the existing research on children and adolescents’ interaction with smartphones addresses the phenomenon of ESO, and, within that subset, analysing the available evidence on its determinants. In the section “Material and methods”, the methodology used in our literature review is described. In the section “Results”, the results of a bibliometric analysis of the corpus are presented, identifying studies that examine ESO and then targeting those that explore its determinants. In the section “Discussion”, the characteristics of these publications and the most relevant factors associated with ESO are evaluated. Finally, in the section “Conclusions”, key elements are outlined for advancing scientific research on how digital technology can both promote and hinder children’s well-being.

Material and methods

The systematic review was performed following the PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews (Page et al., 2021). This review aims to assess the extent of research on ESO determinants and to analyse the findings of the publications that ultimately address these determinants.

Search strategy

A systematic review of scientific publications indexed in Web of Science and Scopus has been carried out. Only publications in English or Spanish were included, focusing on articles, books, and book chapters, while excluding other types of documents such as proceedings, meeting abstracts, editorial material, or book reviews. Publications from 2013 onwards were considered to reflect the rapid expansion of SU among youth over the last decade.

The query string was: [Article Title + Abstract + Keywords] (“mobile access” OR “smartphone access” OR “cell phone access” OR “mobile ownership” OR “smartphone ownership” OR “cell phone ownership” OR “mobile adoption” OR “smartphone adoption” OR “cell phone adoption” OR “mobile use” OR “smartphone use” OR “cell phone use” OR “smartphone usage” OR “mobile usage” OR “cellular phone usage” OR “mobile exposure” OR “smartphone exposure” OR “excessive mobile use” OR “excessive smartphone use” OR “mobile addiction” OR “smartphone addiction” OR “problematic mobile use” OR “problematic smartphone use” OR “digital addiction” OR “screen addiction”) AND (“children” OR “young children” OR “infants” OR “minors” OR “childhood” OR “youth” OR “preteens” OR “tweens” OR “adolescents” OR “teenagers” OR “young people”) AND (“factor*” OR “determinant*” OR “influenc*” OR “driver*” OR “predictor*” OR “cause*” OR “motivation*” OR “reason*” OR “pattern*”).

This search strategy was designed to prioritise studies investigating the determinants of ESO. The inclusion of terms related to access, ownership, and adoption ensures a focus on the critical phase of this study: when and why children and adolescents acquire their first smartphones. Additionally, broader terms such as SU, PSU, or SA were incorporated to capture studies that, while centred on smartphone use, may provide insights into the factors influencing ESO. The final set of search terms (factor, determinant, driver, predictor, etc.) was included to refine the search towards research that examines the underlying mechanisms shaping ESO, a key element in understanding children’s and adolescents’ smartphone use trajectories.

In addition to the studies retrieved through database searches, additional studies were identified via other methods, sourced from references cited in the few studies included in our review that explicitly examined the factors determining ESO. Given their relevance, these studies were incorporated as they provided further insights into the determinants of ESO, complementing the findings from the systematic search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they: (1) focused on determinants of ESO; (2) focused on children (6 to 12 years old) and/or adolescents (up to 16 years old); (3) were published from 2013 onwards; (4) were published in English or Spanish and submitted to peer review; and (5) provided clear results and conclusions.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) focused on ESO prevalence or consequences rather than its determinants; (2) focused on SU/PSU/SA without connection to ESO; (3) focused on related but distinct topics (video game addiction or cyberbullying); or (4) focused on populations outside the study scope, such as preschoolers, adults, elderly individuals, or clinical subgroups (e.g., ADHD, degenerative diseases).

Thus, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were designed to identify recent academic publications that specifically examine the factors determining ESO in children and adolescents. Some flexibility was applied in terms of age, allowing the inclusion of studies involving late adolescents (18–19 years old), university students, or adults (e.g., parents) when they retrospectively explored factors associated with ESO. Accordingly, studies that focused exclusively on ESO without addressing its determinants, as well as those addressing SU/PSU/SA without any connection to ESO, were excluded.

Data screening

All search results were imported into Rayyan for a systematic and collaborative screening process. Duplicate entries were identified and removed to ensure a clean and manageable dataset. The screening was carried out independently by two reviewers working in blind mode to minimise bias and enhance the reliability of the selection process. Publications were assessed based on their titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Reviewer 1 identified seven publications as “included” and one as “maybe” (a classification option in Rayyan), while Reviewer 2 marked eight publications as “included.” The publication in conflict was ultimately included after discussion. Discrepancies in the reviewers’ initial evaluations were resolved through consensus discussions to maintain consistency and alignment with the study objectives.

Data extraction

For the studies that met the inclusion criteria, relevant information was systematically extracted to facilitate categorisation and synthesis. The extracted data focused on the following key dimensions:

-

Population and sample: The target population (children or adolescents), sample size, and geographic context of the study.

-

Instruments: The specific measurement tools used in each study, such as interviews, questionnaires, surveys, or scales.

-

Factors ESO: The determinants identified in each study.

-

Results: The observed relationships between the identified factors and the age at which children receive their first smartphone.

-

Conclusions: Relevant ideas and reflections from the authors related to the focus of this study.

Results

Database and other methods searches

The database search yielded a total of 1577 publications from Web of Science and Scopus. After removing 529 publications that were entirely unrelated to the research objectives, 1048 studies remained for systematic screening. During the screening process, 1039 publications from the data search were excluded because they did not focus on ESO, leaving 9 articles to be examined. Ultimately, from these 9 studies, only 3 studies retrieved from the database search met the inclusion criteria and were considered relevant for examining the determinants of ESO in children and adolescents; the other 6 were about ownership but didn’t explore its determinants.

In addition, 5 further studies on the determinants of ESO were identified from references cited in these included papers, bringing the final number of included studies to 8. The final included studies cover a combined population of 12,912 participants, employ both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, and were conducted in diverse national and cultural contexts.

Figure 1 summarises the screening process, detailing each step from the initial database search to the final selection of studies included in this systematic review.

Description of excluded publications

The screening process led to the exclusion of a significant number of studies that, while addressing topics related to SU/PSU/SA did not align with the specific focus of this research on the determinants of ESO. In total, 852 publications were excluded for analysing SU/PSU/SA among children and adolescents focusing on consequences, prevalence, usage patterns, or measurement instruments. Among these, 195 were specifically excluded for addressing risk factors of SU/PSU/SA. A general overview and categorisation of these 195 studies is provided in Appendix 1.

Additionally, 343 publications were excluded for examining populations outside the scope of this study, and 51 for addressing related but distinct topics such as video game addiction or cyberbullying.

Furthermore, 6 studies were excluded despite examining ESO, as they did not investigate its determinants. However, we consider that they are important because they give us information about the consequences of ESO and the possible link between ESO and PSU/SA. A detailed description of these studies is provided in the following section.

Insights from excluded ESO publications

These six studies focus on the phenomenon of ESO but do not examine its determining factors. Nonetheless, we find it interesting to examine them not only to justify their exclusion—i.e., to clarify why they do not address the determinants—but also because they contribute to a better definition of the ESO category and a broader understanding of the phenomenon. Instead of exploring its determinants, these studies focus on other aspects, such as the prevalence of smartphone ownership among children and adolescents and the age at which they obtained their first smartphone (Oktay & Ozturk, 2024; Tejada-Garitano et al., 2024); correlational evidence linking ESO with future PSU (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2024), SA (Chou & Chou, 2019), problematic Internet use (Sebre et al., 2024), digital addiction (Oktay & Ozturk, 2024), and excessive screen time (Yamada et al., 2024); as well as its effects on well-being (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2024).

Despite not examining the determinants of ESO, these studies provide relevant insights into the broader implications of ESO. Tejada-Garitano et al. (2024) highlight the widespread adoption of smartphones at an early age, with two-thirds of 11- and 12-year-old students already owning a device. Notably, one-third of students received their first smartphone before starting their final year of primary education, and the majority (63.5%) had their first autonomous Internet experience by age eight. Similarly, Oktay and Ozturk (2024) report that 72.63% of children in their sample owned a mobile phone, with those spending more than three hours per day on their device scoring highest on digital addiction scales. These data suggest a potential link between ESO and excessive screen time, a finding further supported by Yamada et al. (2024), who identify ESO at the individual household level as a contributing factor to excessive screen exposure among children and adolescents.

Beyond screen time, ESO has been linked to a range of psychological and behavioural outcomes. Martín-Cárdaba et al. (2024) establish a positive association between ESO and PSU, finding that smartphone ownership is associated with increased psychological discomfort, engagement with influencer-generated content, and the development of parasocial relationships, which, in turn, correlate with higher PSU and a greater likelihood of imitating risky behaviours. Notably, they find that the negative psychological impact of ESO is more pronounced among younger children. These concerns align with Chou and Chou (2019), who report that smartphone ownership, rather than the timing of first Internet access, is significantly associated with SA, reinforcing the idea that ESO is a key factor in the development of compulsive smartphone behaviours. Similarly, Sebre et al. (2024) identify a correlation between ESO and problematic Internet use, with smartphone ownership emerging as a predictive variable in longitudinal analyses. In light of these findings, debates persist regarding the most effective parental mediation strategies. Martín-Cárdaba et al. (2024) suggest that active mediation, while often considered protective, is significantly less effective among children who already own a smartphone, indicating that ESO may weaken the impact of parental control measures.

Description of included publications

The included studies identified a range of factors influencing ESO, employing diverse methodologies and focusing on varied populations across different geographical contexts. Table 1 presents key information extracted from each paper, including population, sample size, geographical context, instruments used, and the determinants of ESO identified.

The included studies focused on diverse populations, including children (n = 1), adolescents (n = 3), late adolescents (n = 1), young adults and university students (n = 2), and parents or caregivers (n = 3). In terms of participants, the total sample comprised 13,291 individuals: children (n = 2,091), adolescents (n = 517), late adolescents (n = 8), young adults and university students (n = 1031), and parents or caregivers (n = 6,397). Geographically, the studies were conducted in the USA (n = 5), Italy (n = 2), and the UK (n = 1). Methodological approaches varied across studies: 4 employed quantitative instruments such as surveys or questionnaires, while another 4 relied on qualitative methods, including interviews, focus groups, and open-ended surveys.

Main findings about determinants of ESO

Among the eight included studies—previously described individually—our analysis identifies four main factors that directly influence ESO: (1) peer pressure combined with fear of social exclusion; (2) household characteristics; (3) parental perceived child/adolescent maturity and independence; and (4) parental concerns about safety and location. This categorisation is based on the frequency with which these factors appear across the studies, indicating their relative prominence. While some variables within the household category (e.g., being an only child or parental separation) were also mentioned only once, their conceptual coherence supports the relevance of household context as a determinant. At a secondary level, additional factors—such as child/adolescent gender, parental perception of smartphones as inevitable, and parental trust in usage control tools—were each identified in a single study.

This categorisation also reflects the diverse nature of the identified factors. Variables like gender or household composition are relatively easy to measure, while others—such as peer pressure, fear of social exclusion, perceived maturity, or parental concerns—are more subjective and complex to operationalise. Overall, the findings highlight the need for further research to better assess the role of these determinants—especially those reported in only one study—in parents’ decisions to give their children a smartphone at an early age. Despite current limitations, the analysis provides valuable insight into the key factors associated with ESO.

Peer pressure, whether experienced directly or through the fear of social exclusion, is consistently identified as a central factor influencing early smartphone ownership (ESO) (Perowne & Gutman, 2024; Vaterlaus & Tarabochia, 2021; Vaterlaus et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2014; Nielsen, 2017). Across several studies, both adolescents and parents describe a growing social norm around smartphone access, which exerts a strong influence over decision-making. Parents frequently report feeling compelled to provide smartphones due to the increasing number of peers who already have one, resulting in a “domino effect” of adoption (Perowne & Gutman, 2024). These authors identified up to eight enablers of ESO, four of which were directly linked to peer dynamics and social belonging: the influence of the child’s peers acquiring smartphones; concerns about social exclusion; the desire to support their child’s social connections; and the influence of other parents’ views and experiences. Peer pressure, therefore, not only stems from adolescents’ social groups but also circulates among parents themselves (Perowne & Gutman, 2024; Vaterlaus & Tarabochia, 2021).

Adolescents, for their part, highlight the centrality of smartphones in peer integration. Restricted access is perceived as a barrier to social participation and a potential trigger for exclusion (Vaterlaus et al., 2021). Smartphones are described as normative during adolescence, enabling frequent and seamless communication through social networking, and serving as a gateway to broader digital connectivity with friends, peers, and extended family. Similarly, studies with late adolescents show that individuals are more likely to acquire a smartphone when someone in their immediate social environment already owns one or intends to do so (Kim et al., 2014). Consistently, both Kim et al. (2014) and Nielsen (2017) found that ESO often occurs as a way to align with prevailing peer norms and avoid standing out.

Household characteristics seem to play a significant role in ESO, as highlighted by several variables: being an only child, having separated parents, and younger parental age were associated with ESO (Cerimoniale et al., 2023). Parental education level was also found to be inversely related to ESO, with lower educational attainment associated with earlier smartphone ownership (Cerimoniale et al., 2023; Gerosa et al., 2024). Additionally, environmental factors such as unrestricted internet access at home and the use of electronic devices during meals correlated with higher ESO prevalence (Cerimoniale et al., 2023).

Perceived child or adolescent maturity and independence also emerged as key determinants of early smartphone ownership, particularly about milestone transitions such as entering middle school or gaining autonomy in daily routines (Moreno et al., 2019; Perowne & Gutman, 2024; Vaterlaus & Tarabochia, 2021). In several studies, both adolescents and parents recognised smartphone acquisition as a symbolic threshold associated with developmental progress and growing responsibility (Moreno et al., 2019; Perowne & Gutman, 2024). For many parents, the transition from primary to middle school, or the beginning of independent travel, represented a critical turning point—one that justified the provision of a smartphone not only as a practical tool but also as a marker of maturity (Perowne & Gutman, 2024). Similarly, Vaterlaus and Tarabochia (2021) found that while some parents adhered to the idea of a “right age” for smartphone ownership, others made the decision based on situational factors such as school transitions. In those cases, older adolescents were seen as ready for a smartphone, whereas younger teens were sometimes provided with basic mobile phones instead. Across studies, readiness was often framed in terms of accountability, autonomy, and perceived maturity. Notably, adolescents themselves generally defer to parental authority when evaluating their preparedness (Moreno et al., 2019; Vaterlaus & Tarabochia, 2021).

Parental concerns about safety and location were also identified as relevant determinants, particularly in contexts where smartphones are perceived as tools for maintaining contact or monitoring children’s whereabouts (Nielsen, 2017; Perowne & Gutman, 2024). Many parents justified ESO primarily on safety grounds, emphasising the importance of being able to communicate with their child at any time and monitor their movements when outside the home (Nielsen, 2017). Perowne and Gutman (2024) similarly found that safety concerns—especially the desire to track location and ensure constant communication—were key motivators for smartphone provision. Parents often highlighted the need to be reachable when children were travelling to school or spending time with friends, framing the smartphone as a practical means of preserving a sense of security and parental oversight.

Lastly, some studies noted other possible determinants that require further exploration. For instance, girls appear more likely than boys to receive smartphones earlier, particularly in families with lower levels of education (Gerosa et al., 2024). Additionally, some parents viewed smartphones as an inevitable part of contemporary childhood and expressed confidence in digital control tools as a way to manage use (Perowne & Gutman, 2024)—factors that may influence parents’ decisions to give their child a first smartphone at an early age.

Some expected associations with ESO did not receive empirical support in the survey-based studies. Cerimoniale et al. (2023) found no significant relationship between parental smartphone use and children’s smartphone ownership. Likewise, Gerosa et al. (2024) reported no significant differences in the age of smartphone ownership between native and immigrant students.

An overview of the identified ESO determinants is presented in Fig. 2. The figure also provides a visualisation of the main consequences of ESO, both (1) the increased likelihood of developing PSU/SA or related issues in the future and (2) some of the documented negative effects of problematic and addictive smartphone use on children and adolescents.

ESO Early Smartphone Ownership, PSU Problematic Smartphone Use, SA Smartphone Addiction, DA Digital Addiction, PIU Problematic Internet Use, EST Excessive Screen Time, FoMO Fear of Missing Out. Dashed arrows: may lead to. Numbers in parentheses (n = x): number of publications identifying each determinant.

Discussion

Our review aimed to search the current scientific literature for answers to the following questions: When should children and adolescents be safely introduced to smartphones? What factors influence the acquisition of smartphones by children and adolescents that may ultimately lead to problematic use? As evident from our findings, the current scientific literature provides little insight into these questions. Most reviewed studies assume the universal use of smartphones among children and adolescents, focusing on prevalence, measurement tools, and consequences rather than the reasons behind this use. Only 195 out of 1053 studies analysed (18.5%) explored the reasons and causes for smartphone use. When narrowing the focus to smartphone ownership, only 14 studies (1.3%) were relevant to our question about the ESO phenomenon, and among them, only 8 publications (0.8%) examined the factors influencing it.

Why does ESO matter? An emerging category of study

The general assumption of a universal presence of smartphones in the early stages of life does not allow us to better understand the factors related to the first acquisition and use of the smartphone—sometimes related to parental provision, sometimes to school activities or peer recommendations (Bozzato & Longobardi, 2024)—, which may be crucial to address further problematic use. The first result of our analysis indicates a gap in the extant scientific literature concerning the factors involved in supplying smartphones to children and adolescents, as well as the reasons behind this practice.

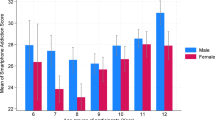

But why does owning a smartphone in an early stage matter? In our review, we have noticed that age, per se, emerges as a determinant in the development of PSU/SA. Some studies suggest that the problems associated with SU decrease with age, noting a downward trend by late adolescence (Lai et al., 2022). Conversely, other studies that focus on age as a determinant propose that there’s more risk of harm in adulthood, so age matters. Besides, the adolescent group (around 14 years old) shows the highest percentage of problematic use relative to young adults (Jo et al., 2018). Moreover, early digital exposure has been linked to cognitive alterations, particularly in attention regulation and impulse control, which may increase susceptibility to PSU (Firth et al., 2019). If we focus on the age of initial use, females and students from lower cultural status families are more likely to receive smartphones earlier, a factor directly associated with adolescents’ well-being challenges (Gerosa et al., 2024). The gender factor appears in only one of the studies reviewed, but according to recent scholarship (Haidt, 2024), girls are experiencing an increase in mental health problems, which is a clear call to delve deeper into understanding this determinant.

Finally, other publications suggest that weekly use of an Internet device before the age of 5 in boys is associated with a higher risk of problematic use compared to those who started after age 12 (Nakayama et al., 2020). On the other hand, some other researchers express the difficulties in finding a relationship between the age of acquisition of their first smartphone and well-being without doing a longitudinal analysis (Vaterlaus et al., 2021). Additionally, the risk of addiction is increased due to the distractive nature of smartphones (Vaterlaus et al., 2021). AI-driven platforms reinforce compulsive digital behaviours through algorithmic recommendation systems, social validation mechanisms, and engagement-maximisation techniques, further intensifying PSU risks after smartphone acquisition (Shin, 2024). In summary, we can conclude that the younger the age of exposure, the higher the risk of problematic or addictive use of smartphones.

For these reasons, we propose a different perspective on the issue. Perhaps the distinction between SU and PSU/SA is blurred when very young children are involved or when parental control and mediation are inadequate. Could it be that at too young an age, the simple fact of owning a smartphone turns most use into problematic use? That’s why some authors have already noted the importance of focusing the study on the ownership phenomena of the device (Gerosa et al., 2024; Perowne & Gutman, 2024), and that’s why we propose to promote Early Smartphone Ownership as a separate and emerging category of analysis. The need for a category that encompasses not only general use but also the timing of ownership is evident in addressing the problem (Gerosa et al., 2024). This distinction is illustrated by extreme cases like those of maternal SA, which have been directly linked to children’s early exposure to smartphones (Kim et al., 2021).

ESO within existing theoretical frameworks

Although the studies included in this review are largely empirical and not explicitly grounded in theory, several of the identified determinants of ESO—particularly peer influence, parental decision-making, and family context—can be tentatively framed within broader developmental and psychosocial models. Social Learning Theory (Bandura, Walters, 1977) provides a useful foundation for understanding how digital norms and behaviours are transmitted through observation, imitation, and reinforcement within family and peer environments. Our findings suggest that both parental modelling and peer group dynamics play a central role in shaping the perceived necessity and social acceptability of smartphone ownership during middle childhood and early adolescence, especially around key transitions such as starting secondary school.

In parallel, Self-Regulation Theory (Baumeister & Heatherton, 1996) helps explain why younger children may struggle to manage smartphone use, given their limited executive functioning and developing impulse control. These vulnerabilities must be understood within the broader context of Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), which emphasises the interaction between individual and environmental factors. Recent studies applying this framework to children’s digital behaviour (Yoo, 2024; Sebre et al., 2024) highlight how familial structures, parenting practices, school dynamics, and sociocultural norms shape both media access and usage patterns. While our review does not directly address Problematic Internet Use, more recent models—such as I-PACE (Brand et al., 2016) and IT-CPU (Domoff et al., 2020)—further illustrate how personal, affective, cognitive, and environmental variables may interact in digital contexts.

Lessons from the results on ESO in parental mediation

Our results focus on at least four main factors that have a direct impact on ESO: peer pressure combined with fear of social exclusion; parental concerns about safety and location; parental perceived child/adolescent maturity/independence; and household characteristics. The first three have a direct relationship with parental mediation and the way parents try to ensure a good childhood.

Parental mediation plays a crucial role in shaping the timing and manner of children’s smartphone adoption. According to the Digital Parenting Framework (Mascheroni et al., 2018), mediation strategies range from restrictive to enabling and laissez-faire approaches. Stricter parental mediation often delays smartphone adoption, while enabling strategies may lead to earlier adoption but with more controlled usage. However, inconsistent parenting or lack of parental control (Yoo, 2024) can contribute to earlier smartphone ownership, sometimes resulting in problematic use. Studies indicate that parental control can serve as a protective factor against SA in young children but may lose effectiveness or even have negative consequences in adolescence (Lee et al., 2024). This highlights the complexity of parental mediation, which must balance supervision with the child’s growing need for autonomy.

A key motivation behind parental mediation is concern for children’s safety and supervision. Many parents provide smartphones to maintain contact and track their child’s location, particularly during transitions such as the move from primary to secondary school (Perowne & Gutman, 2024). Research indicates that 90% of parents cite ease of communication as a major reason for allowing smartphone ownership, while 80% highlight location tracking as an essential feature (Nielsen, 2017). This aligns with the idea that parental mediation is not solely about restricting digital engagement but also about adapting to modern parenting challenges.

Moreover, studies suggest that once a child owns a smartphone, the effectiveness of parental mediation in preventing problematic use decreases significantly (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2024). While parents may start with rules and restrictions, enforcing them becomes increasingly difficult as children gain independence and digital literacy. In some cases, PSU has been linked to underlying social deficits and even compensatory behaviours due to neglectful parenting (Olivella-Cirici et al., 2022). This suggests that while smartphones can be a means of protection and connection, they can also serve as a substitute for active parental engagement, with further consequences.

However, these concerns can sometimes lead to unintended consequences, as smartphones—initially given for safety—may evolve into tools for social validation and increased screen dependence among children and adolescents. As one of the studies suggests, students who received smartphones from their families for communication and safety purposes ultimately use them basically as a means of social interaction and recreational use (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2024).

Parents must face a trade-off: as we have seen their children may benefit from delaying smartphone acquisition—especially if it can be postponed until, at least, 14 years old, as noted by some authors (Gerosa et al., 2024), but parents will need to accept greater autonomy and less control in their children’s interactions and movements in the physical world.

Difficulties measuring ESO determinants

In our study, we have gained some clarity regarding the role of certain determinants in ESO. However, measuring some of these factors—like peer pressure or perceived adolescent maturity—and their precise influence on ESO remains a methodological challenge. The studies examined primarily rely on qualitative assessments, such as self-reported perceptions of social pressure and interview testimonies, rather than objective or quantifiable metrics. This reliance on subjective accounts makes it difficult to establish a standardised measure of peer influence in ESO.

We should think about looking for a measure approximation in some social models. Theoretical frameworks suggest that when a committed minority—approximately 25% of a given population—adopts a particular norm, it can trigger a broader social shift, making the new behaviour appear normative and entrenched (Centola, 2018). Applied to smartphone ownership, this implies that once a critical mass of adolescents possess smartphones, the perceived necessity for others to follow suit increases. This can help us to make some kind of quantifiable construction of peer pressure.

One limitation of this study, which also suggests direction for future research, is the need for a reliable metric to assess factors. A standardised measure would help better understand and mitigate its influence, ensuring that parents do not feel compelled to give their children smartphones prematurely. Family surveys, such as those conducted by the Adolescència Lliure de Mòbils (2024) movement in Spain, highlight the impact of peer pressure: 82.1% of children receive a smartphone from their parents before the age of 12, even though 61.7% of parents believe that 16 is the ideal age. Furthermore, 33% of families cite peer pressure as the primary reason for providing a smartphone.

Our results in the context of the current international debate

A lively international debate is currently underway regarding the need for regulations on children’s and adolescents’ SU. As noted in the introduction, social movements advocating for smartphone restrictions among minors have emerged worldwide, responding to concerns about a “phone-based childhood” (Haidt, 2024).

The social and scientific debate appears to be polarised between two main perspectives. On one side, researchers argue that increased smartphone and social media use is directly linked to rising mental health issues among adolescents, particularly girls (Desmurget, 2022; Haidt, 2024). On the other side, some scholars acknowledge the growing prevalence of psychological distress among young people but attribute it to multifactorial causes, suggesting that the correlation between SU/PSU/SA and mental health problems is not necessarily causal (Odgers, 2024).

While this academic discussion continues, family-led movements are voicing concerns about raising children in an increasingly digital society. Many of these groups advocate for delaying smartphone ownership, invoking the precautionary principle. Initiatives such as Adolescència Lliure de Mòbils in Spain, Wait Until 8th in the USA, and Smartphone-Free Childhood in the UK promote collective agreements among families to postpone giving smartphones to their children until at least age 14 or 16, depending on the movement. The primary aim of these agreements is to reduce social pressure and allow children to reach a sufficient level of maturity before introducing them to smartphone use.

Our study highlights exactly these last two elements: social pressure and developmental readiness as two of the most influential factors in the ESO phenomenon. Recognising their importance underscores the relevance of these family-led initiatives in shifting societal norms. Moreover, the growing media impact and political influence of these movements—evidenced by policy changes in countries such as Spain, Italy, Australia, and New Zealand—demonstrate the effectiveness of their approach and a good intuition before evidence is shown. Addressing social pressure and ensuring that children reach the appropriate level of maturity before smartphone use may be key to determining the ideal age for smartphone adoption, as our paper suggests.

Conclusions

Our study highlights a significant yet underexplored area: the appropriate age at which children first receive smartphones and the subsequent developmental impacts of this parental decision. While most existing research has focused on mobile-related consequences in adolescents, very few studies have analysed the family and social determinants influencing ESO. Our systematic review of 1053 scientific publications identified a significant gap, with only 14 studies (1.3%) specifically addressing smartphone ownership and its age of introduction, and merely 8 publications (0.8%) explicitly exploring underlying determinants.

Among the determinants identified, four stand out as central: peer pressure associated with fear of social exclusion; household characteristics such as single-child households, separated parents, parental education level, parental age, internet access, and device usage patterns during meals; perceptions of adolescent maturity and independence; and parental concerns regarding safety and location. Additional factors requiring further research include gender differences and parental trust in digital control tools.

Future research should focus on developing measurement instruments (e.g., surveys, structured interviews, or observational frameworks) to systematically assess the factors influencing parental decision-making regarding ESO. The development of such instruments could be informed by existing validated tools, such as the Peer Pressure Inventory (Clasen & Brown, 1985), which measures adolescents’ susceptibility to peer influence, or the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), which assesses parental trust and communication. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the long-term impact of ESO on digital behaviours, particularly its correlation with SU, PSU, and SA in adolescence (Vaterlaus & Tarabochia, 2021). Further investigations should explore cross-cultural variations, assessing how national policies, digital literacy programs, and age-based regulations shape ESO trends. Additionally, research should compare adolescent outcomes (e.g., mental health, school performance, and well-being) based on the age of smartphone acquisition, and whether receiving a basic phone first differs from acquiring a smartphone as a first device. A systematic review could evaluate whether research trends are shifting towards a balanced focus on ESO determinants, addressing the current gap in pre-ownership studies. Findings from these studies could inform policy recommendations and parental strategies, ensuring that ESO decisions are based on scientific insights rather than market-driven trends (Kim et al., 2014; Vaterlaus & Tarabochia, 2021).

This review positions Early Smartphone Ownership as a relevant and underexplored factor in the trajectory of children’s digital engagement. By identifying its key determinants and conceptualising ESO as a distinct object of study, we hope our findings may help shift the focus from reactive responses to problematic use toward a more preventive and structurally informed understanding of how digital habits begin in children and adolescents.

Data availability

All data for this literature review (e.g., bibliographic records, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and coding materials) are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Publicly accessible databases (Web of Science and Scopus) served as the primary sources for the collected references.

References

Adelhardt Z, Markus S, Eberle T (2018) Six months of “digital death”: Teenagers’ reaction on separation from social media. In: Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Social Media (ECSM 2018). pp. 459–461. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-85064683259&partnerID=MN8TOARS

Adolescència Lliure de Mòbils (2024) Survey of 23,000 families in Catalonia about smartphone use. https://adolescencialliuredemobils.cat/

Ahmed S, Al Fidah MF, Efa SS, Naher SS, Amin MK (2023) Cell phone use and self-reported wellbeing among teenage students of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull 49(3):150–156. https://doi.org/10.3329/bmrcb.v49i3.67912

Amran MS, Roslan MZ, Sommer W (2024) Compulsive digital use: the risk and link of loneliness among adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health 36(4):419–423. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2024-0047

Anderson M, Jiang J (2018) Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

Armsden GC, Greenberg MT (1987) The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 16(5):427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939

Azizi A, Emamian MH, Hashemi H, Fotouhi A (2024) Smartphone addiction in Iranian schoolchildren: a population-based study. Sci Rep 14(1):22304. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73816-8

Bae SM (2015) The relationships between perceived parenting style, learning motivation, friendship satisfaction, and the addictive use of smartphones with elementary school students of South Korea: using multivariate latent growth modeling. Sch Psychol Int 36(5):513–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315604017

Ban J, Kim D (2024) Structural relationship among aggression, depression, smartphone dependency, and cyberbullying perpetration. Child Youth Serv Rev. 166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107976

Bandura A, Walters RH (1977) Social learning theory. Prentice hall

Baumeister RF, Heatherton TF (1996) Self-regulation failure: an overview. Psychol Inq 7(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0701_1

Bhaimiya S (2024, July 17) A growing number of parents are refusing to give their children smartphones—and the movement is going global. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2024/07/17/a-smartphone-free-childhood-a-global-movement-is-growing.html

Blair BL, Fletcher AC (2011) The only 13-year-old on planet earth without a cell phone”: meanings of cell phones in early adolescents’ everyday lives. J Adolesc Res 26(2):155–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558410371127

Bozzato P, Longobardi C (2024) School climate and connectedness predict problematic smartphone and social media use in Italian adolescents. Int J Sch Educ Psychol 12(2):83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2024.2328833

Brand M, Young KS, Laiera C, Wölfling K, Potenza MN (2016) Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: an interaction of person-affect- cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 71:252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Brodersen K, Hammami N, Katapally TR (2022) Smartphone use and mental health among youth: it is time to develop smartphone-specific screen time guidelines. Youth 2(1):23–38. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010003

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press

Centola D (2018) Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention. Science 360(2018):1116–1119. 10.1126/science.aas8827

Cerimoniale G, Dalpiaz I, Becherucci P, Malorgio E, Ceschin F, Vitali Rosati G, Ragni G, Minardo G, Brambilla P, Gambotto S, Bottaro G, Tucci PL, Chiappini E (2023) The digital child: a cross-sectional survey study on the access to electronic devices in paediatrics. Acta Paediatrica 112(8):1792–1803. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.16817

Chou H-L, Chou C (2019) A quantitative analysis of factors related to Taiwan teenagers’ smartphone addiction tendency using a random sample of parent-child dyads. Comput Hum Behav 99:335–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.032

Clasen DR, Brown BB (1985) The multidimensionality of peer pressure in adolescence. J Youth Adolesce 14(6):451–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02139520

Desmurget M (2022) Screen Damage: the dangers of digital media for children. Polity Press

Domoff SE, Borgen AL, Radesky JS (2020) Interactional theory of childhood problematic media use. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 2(4):343–353. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.217

Firth J, Torous J, Stubbs B, Firth JA, Steiner GZ, Smith L, Sarris J (2019) The “online brain”: how the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry 18(2):119–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20617

Fischer-Grote L, Kothgassner OD, Felnhofer A (2019) Risk factors for problematic smartphone use in children and adolescents: a review of existing literature. Neuropsychiatrie 33(4):179–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40211-019-00319-8

Ganesamoorthy K, Rangassamy I, Dhasaram P, Santhaseelan A (2024) Assessment of screen time and its correlates among adolescents in selected rural areas of Puducherry. Int J Adolesc Med Health 36(5):467–472. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2024-0093

Gerosa T, Losi L, Gui M (2024) The age of the smartphone: an analysis of social predictors of children’s age of access and potential consequences over time. Youth Soc 56(6):1117–1143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X231223218

Haidt J (2024) The anxious generation: how the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. Penguin Press

Harvey DL, Milton K, Jones AP, Atkin AJ (2022) International trends in screen-based behaviours from 2012 to 2019. Prevent Med 154:106909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106909

Haug S, Paz Castro R, Kwon M, Filler A, Kowatsch T, Schaub MP (2015) Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. J Behav Addict 4(4):299–307. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.037

Hwang Y, Jeong S-H (2015) Predictors of parental mediation regarding children’s smartphone use. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 18(12):737–743. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0286

INE (2023) Encuesta sobre equipamiento y uso de tecnologías de información y comunicación en los hogares 2023. https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?tpx=60814

Jeong A, Ryu S, Kim S, Park H-K, Hwang H-S, Park K-Y (2023) Association between problematic smartphone use and physical activity among adolescents: a path analysis based on the 2020 Korea Youth Risk Behaviour Web-Based Survey. Korean J Fam Med 44(5):268–273. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.22.0154

Jo H, Na E, Kim D-J (2018) The relationship between smartphone addiction predisposition and impulsivity among Korean smartphone users. Addict Res Theory 26(1):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1312356

Karakose T, Tülübaş T, Papadakis S (2022) Revealing the intellectual structure and evolution of digital addiction research: an integrated bibliometric and science mapping approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214883

Khalaf AM, Alubied AA, Khalaf AM, Rifaey AA (2023) The impact of social media on the mental health of adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Cureus 15(8):e42990. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.42990

Kim D, Chun H, Lee H (2014) Determining the factors that influence college students’ adoption of smartphones J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 65:578–588

Kim B, Han SR, Park EJ, Yoo H, Suh S, Shin Y (2021) The relationship between mother’s smartphone addiction and children’s smartphone usage. Psychiatry Investig 18(2):126–131. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2020.0338

Knop K, Hefner D (2018) Friend or foe in the pocket?–The role of the individual, peergroup and parents for (dys)functional mobile phone use. Prax Kinderpsychologie Kinderpsychiatrie 67(2):204–216. https://doi.org/10.13109/prkk.2018.67.2.204

Kumcagiz H (2019) Quality of life as a predictor of smartphone addiction risk among adolescents. Technol Knowl Learn 24(1):117–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-017-9348-6

Lai X, Huang S, Nie C, Yan JJ, Li Y, Wang Y, Luo Y (2022) Trajectory of problematic smartphone use among adolescents aged 10-18 years: the roles of childhood family environment and concurrent parent-child relationships. J Behav Addict 11(2):577–587. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00047

Lally P, Van Jaarsveld CH, Potts HW, Wardle J (2010) How are habits formed: modelling habit formation in the real world. Eur J Soc Psychol 40(6):998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Lee J, Lee S, Shin Y (2024) Lack of parental control is longitudinally associated with higher smartphone addiction tendency in young children: a population-based cohort study. J Korean Med Sci 39(34):1–6. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e254

Lenhart A (2009) Teens and mobile phones over the past five years: Pew Internet looks back. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2009/08/19/teens-and-mobile-phones-over-the-past-five-years-pew-internet-looks-back/

Li Y, Mu W, Sun C, Kwok SYCL (2023) Surrounded by smartphones: relationship between peer phubbing, psychological distress, problematic smartphone use, daytime sleepiness, and subjective sleep quality. Appl Res Qual Life 18(2):1099–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-022-10136-x

Livingstone S, Haddon L, Görzig A, Ólafsson K (2011) Risks and safety on the internet: The perspective of European children: full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids Online survey of 9–16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries. EU Kids Online Network. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/33731/

Livingstone S, Kardefelt-Winther D, Stoilova M (2020) Parenting for a digital future: How hopes and fears about technology shape children’s lives. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190874698.001.0001

Lu X, An X, Chen S (2024) Trends and influencing factors in problematic smartphone use prevalence (2012–2022): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 27(9):616–634. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2023.0548

Madden M, Lenhart A, Cortesi S, Gasser U, Duggan M, Smith A, Beaton M (2013) Teens, social media, and privacy. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/05/21/teens-social-media-and-privacy/

Martín-Cárdaba MA, Díaz MVM, Pérez PL, Castro JG (2024) Smartphone ownership, minors’ well-being, and parental mediation strategies. an analysis in the context of social media influencers. J Youth Adolesc 53(10):2202–2218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-024-02013-7

Martínez-Estévez NS, Zamora-Reyes CG, Robayo-González CX, Restrepo CG, Rey-Atehortúa MM, Solano-Aragón DC (2024) Characterization of electronic device use among children and adolescents aged 6 to 14. Paediatr Croatica 68(1):13–21. https://doi.org/10.13112/PC.2024.2

Mascheroni G, Ponte C, Jorge A (2018) Digital parenting : the challenges for families in the digital age. Nordicom

Meng S-Q, Cheng J-L, Li Y-Y, Yang X-Q, Zheng J-W, Chang X-W, Shi Y, Chen Y, Lu L, Sun Y, Bao Y-P, Shi J (2022) Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 92:102128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102128

Moreno MA, Kerr B, Jenkins M, Lam E, Malik FS (2019) Perspectives on smartphone ownership and use by early adolescents. J Adolesc Health 64(4):437–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.017

Nakayama H, Ueno F, Mihara S, Kitayuguchi T, Higuchi S (2020) Relationship between problematic Internet use and age at initial weekly Internet use. J Behav Addict 9(1):129–139. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00009

Nielsen (2017) Mobile kids: The parent, the child and the smartphone. https://www.nielsen.com/insights/2017/mobile-kids-the-parent-the-child-and-the-smartphone/

Odgers CL (2024) The great rewiring: is social media really behind an epidemic of teenage mental illness? Nature 628:29–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00902-2

Olivella-Cirici M, Sánchez-Ledesma E, Continente X, Clotas C, Pérez G (2022) Perceptions of the uses of cell phones and their impact on the health of early adolescents in Barcelona: a qualitative study. J Technol Behav Sci 7(2):130–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-021-00228-0

Oktay D, Ozturk C (2024) Digital addiction in children and affecting factors. Children 11(4):417. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040417

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, … Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Papadakis S, Alexandraki F, Zaranis N (2022) Mobile device use among preschool-aged children in Greece. Educ Inf Technol 27(2):2717–2750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10718-6

Perowne R, Gutman LM (2024) Parents’ perspectives on smartphone acquisition amongst 9-to 12-year-old children in the UK—a behaviour change approach. J Fam Stud 30(1):63–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2023.2207563

Quintana O, Menacho J, Casanovas X, Puig L (2023) Four questions for techno-ethics. Ramon Llull J Appl Ethics 14(14):181–201. https://doi.org/10.34810/rljaev1n14Id413970

Safaria T, Abdul Wahab MN, Suyono H, Hartanto D (2024) Smartphone use as a mediator of self-control and emotional dysregulation in nomophobia: a cross-national study of Indonesia and Malaysia. Psikohumaniora J Penelit Psikol 9(1):37–58. https://doi.org/10.21580/pjpp.v9i1.20740

Sebre SB, Pakalniškienė V, Jusienė R, Wu JC-L, Miltuze A, Martinsone B, Lazdiņa E (2024) Children’s problematic use of the internet in biological and social context: a one-year longitudinal study. J Child Fam Stud 33(3):746–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02527-3

Setiadi R, Tini, Sukamto E, Kalsum U (2019) The risk of smartphone addiction to emotional mental disorders among junior high school students. Belitung Nurs J 5(5):197–203. https://doi.org/10.33546/bnj.841

Shin D (2024) Artificial misinformation. Exploring human-algorithm interaction online. Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-52569-8

Smahel D, Machackova H, Mascheroni G, Dedkova L, Staksrud E, Ólafsson K, Livingstone S, Hasebrink U (2020) EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo

Sohn S, Rees P, Wildridge B, Kalk NJ, Carter B (2019) Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: a systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 19:356. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2350-x

Tejada-Garitano E, Ruiz UG, Berasaluce JP, Alonso AA (2024) 12-year-old students of Spain and their digital ecosystem: the cyberculture of the Frontier Collective. J New Approach Educ Res 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44322-024-00017-6

Terras MM, Ramsay J (2016) Family digital literacy practices and children’s mobile phone use. Front Psychol 7(1957). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01957

Tomczyk Ł, Lizde ES, Mascia ML, Bonfiglio NS, Renati R, Guillén-Gámez FD, Penna MP (2024) Problematic smartphone use among young people and the use of additional social networking software—an example from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Child Indic Res 17(3):1239–1271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-024-10120-x

Vaterlaus JM, Aylward A, Tarabochia D, Martin JD (2021) A smartphone made my life easier”: an exploratory study on age of adolescent smartphone acquisition and well-being. Comput Hum Behav 114:106563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106563

Vaterlaus JM, Tarabochia D (2021) Adolescent smartphone acquisition: an exploratory qualitative case study with late adolescents and their parents. Marriage Fam Rev 57(2):143–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2020.1791302

Yamada M, Sekine M, Tatsuse T (2024) Association between excessive screen time and school-level proportion of no family rules among elementary school children in Japan: a multilevel analysis. Environ Health Prevent Med 29:16. https://doi.org/10.1265/ehpm.23-00268

Yoo C (2024) What makes children aged 10 to 13 engage in problematic smartphone use? A longitudinal study of changing patterns considering individual, parental, and school factors. J Behav Addict 13(1):76–87. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2024.00002

Yue Y, Aibao Z, TingHao T (2022) The interconnections among the intensity of social network use, anxiety, smartphone addiction and the parent-child relationship of adolescents: a moderated mediation effect. Acta Psychol 231:103796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103796

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the MobilePressure project (grant 24S05912-001), funded by the Barcelona City Council under the “Recerca Jove i Emergents” call (2024–2026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. JA, XC, and CM jointly conceptualised the study and participated in the analysis and interpretation of the results. JA and XC conducted the screening process, while CM focused on the statistical analysis of the results concerning included and excluded publications. All authors were involved in drafting, revising, and approving the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study involved only a systematic review and analysis of previously published literature and did not include human participants, primary data collection, or use of personal data. Therefore, it did not require ethics approval. This exemption has been confirmed by the Research Ethics Committee of IQS—Ramon Llull University with code 2025_003 on 6 May 2025. All procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Code of Research Integrity of Ramon Llull University.

Informed consent

As no new data were collected from human participants and no personally identifiable information was used, informed consent was not applicable to this study. All data analysed were from publicly available published sources.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Albacete-Maza, J., Casanovas Combalia, X. & Montañola-Sales, C. Determinants of early smartphone ownership: a research gap in the study of problematic smartphone use in children and adolescents. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1179 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05557-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05557-6