Abstract

Despite substantial scientific developments, companies and professionals are unaware of or do not appreciate the negative repercussions linked to AI-enabled interviews. From the standpoint of job seekers, this raises questions regarding the reasons why certain candidates decline job chances that incorporate AI-enabled interviews. By integrating the capacity-personality framework, fairness heuristic theory, and signaling theory, we investigate the interactive effect between interview format (traditional video interviews vs. AI-enabled interviews) and industry type (high-tech industries vs. low-tech industries) on candidates’ intention to apply for a job. The results from an online scenario-based experiment suggested that interview format and industry type interactively influence candidates’ job application intention, with candidates being more inclined to attend AI-enabled interviews in high-tech industries. We also found that both perceived procedural justice and organizational attractiveness mediate the relationship between interview format and candidates’ intention to apply for jobs, but they do not mediate the interactive effects between interview format and industry type on candidates’ job application intention. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our findings, which contribute to the sustainable use of AI-enabled tools in the job application process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of information technology has had a profound impact on human resource management (HRM), causing significant changes in how organizations attract, select, motivate, and retain employees (Stone et al. 2015). The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) has further accelerated this transformation, influencing people’s productivity, lifestyle, and the overall workplace environment. This shift presents both opportunities and challenges for traditional HRM practices (Pereira et al. 2023; Zhao et al. 2019). The widespread application of AI has fundamentally changed the dynamics between companies and employees, intensifying the automation of administrative HRM tasks (Vrontis et al. 2021). Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of AI in HRM, as companies seek ways to simulate real work conditions for evaluation and recruitment purposes (Vrontis et al. 2021). Advanced technologies like resume screening and AI-enabled interviews enable companies to efficiently process large volumes of applications, leading to a faster and ideally less biased candidate selection process (Alsever, 2017; Miller et al. 2018; Reilly, 2018). An illustrative example is Unilever, which saved 100,000 h of interviewing time and approximately 1 million USD in recruitment costs in 2018 by utilizing AI to analyze video interviews (Booth, 2019).

However, previous studies have produced conflicting results regarding the effectiveness of AI-enabled interviews. Some studies have supported the use of AI-enabled interviews, as many participants believed that AI evaluation would be fairer and less biased compared to evaluations conducted by humans (Mirowska and Mesnet, 2022). Additionally, the introduction of AI in the recruitment process could potentially increase the likelihood of positive job applications and foster sustainable pre-employment relationships (Huang and Liao, 2015; Van Esch et al. 2019). Furthermore, an enjoyable and engaging interview experience with AI-powered technology could enhance an organization’s image, generate interest, and attract candidates (Brahmana and Brahmana, 2012; Howardson and Behrend, 2014). On the contrary, critics have raised concerns about the effects of AI-enabled interviews, questioning their favorability among applicants and their ability to accurately identify suitable employees (Suen et al. 2019; Vrontis et al. 2021). Some preliminary evidence has indicated that automated algorithmic interviews are perceived less favorably compared to traditional human-conducted interviews (Acikgoz et al. 2020; Gonzalez et al. 2019; Lee, 2018; Mirowska and Mesnet, 2022). Moreover, the use of artificial intelligence evaluation may discourage applications since some level of human interaction is preferred (Mirowska and Mesnet, 2022). In certain cases, algorithmic decision-making in HRM can even be unethical and lead to discriminatory outcomes (Köchling and Wehner, 2020). For example, Amazon’s biased recruiting tool was abandoned after the algorithm learned to favor male candidates, highlighting the flaws in the automated hiring processes (De Cremer, 2021).

Recruitment and selection involve a complex decision-making process where both job-seekers and hiring organizations gather information about each other, evaluate, and determine whether to proceed with the employment process (Li and Song, 2017; Uggerslev et al. 2012; Wesche and Sonderegger, 2021). The initial stage of this process is the interview, which helps assess the attractiveness of the organization and the candidate. If a job seeker finds the job appealing, they are more likely to stay in the applicant pool and potentially accept a job offer (Chapman et al. 2005). However, the incorporation of new technologies like AI in interviews is an area that lacks sufficient research. The perception of job seekers towards AI-enabled interviews and their preferences regarding such interviews are not well-studied. This raises questions about the effective utilization of AI-enabled interviews. To gain a better understanding of this emerging topic from the job applicants’ perspective, we aim to investigate the impact of AI-enabled interviews on applicants’ attitudes and their subsequent behavioral intentions by using a scenario-based experimental design.

To start with, Pan et al. (2022) suggest that the effectiveness of AI-enabled interviews depends on various contextual factors, such as industry. Every interview is conducted in a certain industry, which affects job candidates’ attitudes toward the interview. However, there has been limited discussion on how the effectiveness of AI-enabled interviews varies across different industries. Our study aims to address this gap by considering the interaction between interview format (traditional video interviews vs. AI-enabled interviews) and industry type (high-tech industries vs. low-tech industries). Companies in the IT and telecom industries, for instance, have strong technical capabilities to facilitate the integration of AI technologies into their business processes (Yu et al. 2023). Consequently, candidates perceive the use of cutting-edge AI technology as a positive signal and are more likely to complete the application process in these high-tech industries (Holm, 2014; Van Esch et al. 2019).

Furthermore, the use of AI technology in job interviews yields information about the employer that elicits job seekers’ perceptions and reactions. According to McCarthy et al. (2017), job seekers’ perceived procedural justice, which refers to their trust in the fairness of the job interview’s procedures, significantly influences their attitude towards the company. However, there is inconsistent evidence regarding whether candidates perceive AI-enabled selection as fair (Acikgoz et al. 2020; Van Esch et al. 2019). Simultaneously, the attractiveness of the organization, which pertains to how job candidates perceive the interview process or organization as appealing, also determines their preference for the company (Highhouse et al. 2003). Studies have indicated that the novelty associated with interacting with AI-enabled recruiting tools can be a highly influential source of attraction and motivation (Mirowska and Mesnet, 2022). Consequently, job candidates are less likely to have an intention to apply for jobs when they are less attracted to the company. Although the effects of interview format on job seekers’ perceptions of fairness and organizational attractiveness have been extensively documented (e.g., Hunkenschroer and Lütge, 2021; Langer et al. 2020; Roulin and Bourdage, 2023; Oostrom et al. 2024), we extend this line of research by proposing that perceived procedural justice and organizational attractiveness function as two parallel mechanisms mediating not only the direct effect of interview format, but also the interactive effect between interview format and industry type on candidates’ intentions to apply for jobs.

To accomplish these objectives, we conducted an online scenario-based experiment for full-time employees. It utilized a factorial design involving two different industries and two interview formats, with each participant randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. By doing so, this research aims to make several contributions. First, it enhances our understanding of contextual factors that impact the effectiveness of AI interviews by identifying industry as a vital boundary condition. Second, it contributes to illustrating how interview type affects candidates’ intention to apply for jobs by revealing perceived procedural justice and organizational attractiveness as two important psychological processes. On the one hand, job seekers tend to perceive AI interviews as less fair because algorithms fail to consider interviewees’ personalized expressions. On the other hand, interview type, as an important HRM practice, signals the values of organizations, which in turn affects candidates’ perceived organizational attractiveness. Lastly, the study intends to improve practitioners’ understanding of AI-enabled interviews, enabling them to leverage this technology to widen the pool of applicants and mitigate any negative consequences associated with this novel selection method.

Theory and hypotheses development

AI-enabled interviews and job application intention

In the majority of AI-enabled interviews, a chatbot poses a set of predetermined questions to the interviewee, allowing them a brief timeframe to respond (Jaser and Petrakaki, 2023). During this process, the bot collects data pertaining to the candidate’s visual, verbal, and vocal cues, subsequently generating an automated prediction about their suitability for the job (Jaser and Petrakaki, 2023). In our study, we define such interviews as AI-enabled interviews. In contrast, traditional video interviews refer to online interviews conducted on a screen, involving participants who are physically separated yet present together virtually. While tele-communication technology is employed in these interviews, it does not encompass AI decision-making tools. To compare the impact of different interview formats, we categorized them into two scenarios: traditional video interviews and AI-enabled interviews. In this context, AI-enabled interviews denote virtual interviews conducted by AI-humanoid interviewers and analyzed by algorithms, capable of generating automatic decisions about candidates. Advanced technologies like AI-enabled interviews offer advantages to companies in terms of efficiency and cost (Wesche and Sonderegger, 2021). However, candidates have expressed concerns about the effects of AI-enabled interviews in terms of their ability to accurately assess applicants, potential algorithmic discrimination, and favorability among candidates (Suen et al. 2019; Vrontis et al. 2021).

First, there is skepticism regarding AI’s capability to identify truly suitable employees. AI-enabled hiring tools employ facial and body language recognition to generate insights into candidates’ personality traits, such as “conscientiousness” or “altruism” (Drage and Mackereth, 2022). However, Tippins et al. (2021) argue that AI-enabled interview systems are akin to digital snake oil, lacking a scientific foundation and relying on shallow measurements and arbitrary number crunching. This approach may penalize non-native speakers, visibly nervous interviewees, or anyone who deviates from a predetermined model of appearance and speech, rather than identifying the best fit for the job based on deeper qualities like proactivity and values. Since algorithms in AI-enabled interviews rely on large amounts of statistical data, the presence of manipulated or biased information could result in partial generalization, leading to missed opportunities for qualified candidates (Wang et al. 2020). If AI-enabled interviews fail to accurately and comprehensively analyze candidates’ competencies and personality traits, it becomes challenging for candidates to trust the assessment system. Moreover, a lack of trust in data accuracy and insufficient control over algorithmic candidate matching can breed reluctance to embrace AI-enabled interviews, potentially causing candidates to withdraw from the hiring process (Li et al. 2021).

Second, the presence of algorithmic bias and discrimination in AI-enabled interviews could undermine the job seekers’ trust in them. Concerns about trust remain prevalent in the use of AI technology. Research on judgmental systems, such as forecasting systems, indicates that humans are generally trusted more than computers (Dietvorst et al. 2015; Önkal et al. 2009). Particularly, Dietvorst et al. (2015) suggests that in tasks requiring social intelligence, trust in humans surpasses trust in AI. It is widely recognized that algorithmic decision-making in HRM can sometimes act unethically and even result in discriminatory outcomes (Köchling and Wehner, 2020). An example is Amazon’s biased recruiting tool mentioned above (De Cremer, 2021). Other studies have indicated that low reliability significantly diminishes trust, and rebuilding trust is challenging and time-consuming (Dietvorst et al. 2015; Dzindolet et al. 2003; Manzey et al. 2012). Therefore, errors in algorithms during AI-enabled interviews may lead to distrust and psychological resistance among job applicants.

Third, job seekers generally have a less positive view of AI-enabled interviews compared to traditional video interviews. Several studies have found that this perception is partly due to the limited human interaction in AI-enabled interviews (Acikgoz et al. 2020; Gonzalez et al. 2019; Lee, 2018; Mirowska and Mesnet, 2022). Job candidates expect respectful treatment and a positive experience from recruiters throughout the job-seeking process. It is important to note that the adoption of AI is not a simple “plug and play” model; it raises ethical concerns and emphasizes the human aspect of an organization (Sanders and Wood, 2019). Notably, current AI-enabled interviews primarily automate processes during the early stages, which eliminates human judgment and overlooks candidates’ desire for interpersonal interaction. Consequently, job candidates may prefer traditional video interviews that provide more personal contact and may feel less motivated to apply for positions that involve AI-enabled interview methods.

Moreover, the perception of AI plays a significant role in determining its acceptance and utilization (Del Giudice et al. 2023). The inherent apprehension towards uncertainty compels individuals to reject AI. The resistance to adopting AI arises due to a distorted and reduced understanding of its usability and benefits (Polites and Karahanna, 2012). Consequently, when it comes to AI recruitment, individual inertia explains why job seekers prefer to stick to the current practices, resulting in their reluctance to prioritize AI-assisted assessments over traditional human-dominated interviews. Particularly regarding the perceived ease of use, individuals with limited computer skills may experience AI anxiety and technophobia due to a lack of accessible learning resources for new AI products. This leads to a group of individuals who lag in adopting AI technology and are less inclined to utilize AI-enabled interviews during the job application process. We thus anticipate that job applicants will display a greater inclination towards traditional video interviews in comparison to AI-enabled interviews. We propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Applicants are more likely to express a greater intention to apply for positions that utilize traditional video interviews compared to AI-enabled interviews.

The interactive effect of interview format and industry type on job application intention

According to Pan et al. (2022), the success of AI-enabled interviews relies on various contextual elements. These factors include the broader environmental context (e.g., industry and regulations), the organizational context (e.g., company size and technology competence), and the technical context (e.g., relative advantage and complexity of AI systems). The particular focus of this study is on the influence of industry. The type of industry in which a company operates has a substantial impact on its innovation practices (Oliveira and Martins, 2010) and human resource strategies (Malik et al. 2021). To explore the interaction between industry and interview format, we draw on the capability-personalization framework (Qin et al. 2024, 2025). The framework posits that individuals’ reactions to AI systems hinge on two psychological appraisals: their perception of AI’s evaluative capability and their perceived need for personalized human-like interaction (Qin et al. 2024, 2025). Applying this framework to the job-application context, we argue that applicants’ perceptions in different industries vary systematically on both dimensions, yielding an interactive effect of industry type and interview format on job application intention.

In terms of capability, on the one hand, high-tech sectors (e.g., information technology) possess extensive experience with information technologies (Bughin et al. 2017; Ransbotham et al. 2017) and substantial technical resources for AI adoption (Yu et al. 2023). High-tech industries thus demonstrate established norms of AI integration (Alsheibani et al. 2018) and greater readiness for emerging technologies (Richey et al. 2007). On the other hand, applicants from these industries tend to be technically literate (e.g., understand AI assessment logic and metrics), believe that AI can more objectively evaluate the role-specific skills (e.g., coding ability and analytical thinking), and feel confident in performing well in a structured, logic-driven assessment environment, which AI interviews tend to provide. Collectively, these organizational and personal factors contribute to high-tech applicants’ perceptions of AI’s capability.

In terms of the necessity of personalization, first, high-tech industry applicants are likely to expect less interpersonal warmth or relational depth in evaluative settings. Second, they place lower importance on rapport-building, social chemistry, or personalized feedback, which are disadvantages of an AI interview. Third, they are more comfortable with depersonalized or automated interactions, given the norms and culture of tech-driven environments in the high-tech industry. Together with their stronger perceptions of AI’s capability, these lower personalization needs translate into greater AI appreciation—not merely tolerance, but a belief that AI may be more reliable or even advantageous compared to subjective human judgment in hiring processes.

In contrast, low-tech industries generally display lower technological maturity, and their applicants may doubt both their employers’ ability to implement AI effectively and their own capacity to “play by AI’s rules” due to limited familiarity with such systems (i.e., low capability perception). Moreover, these applicants place a high value on human‐to‐human interaction, particularly for roles requiring interpersonal skills, emotional labor, or relational fit (i.e., high personalization needs). Together, these factors explain why high‐tech industry applicants view AI interviews as more procedurally acceptable and better aligned with organizational practices—experiencing lower AI aversion—whereas low-tech‐industry applicants may feel discomfort, perceive AI systems as unfair or misaligned, and demonstrate lower application intentions under AI‐enabled interview formats. We thus propose the following:

H2: Interview format and industry type interactively influence applicants’ intention to apply for jobs. Specifically, candidates are more inclined to apply for jobs with AI-enabled interviews in high-tech industries than in low-tech industries.

The mediating role of perceived procedural justice

The connection between different aspects of selection practices and how applicants react is influenced by their perceptions of fairness (Gilliland, 1993; Hausknecht et al. 2004; Ryan and Ployhart, 2000). According to McCarthy et al. (2017), the perceived procedural justice of job seekers significantly impacts their attitude towards the company. Combining fairness heuristic theory (Lind, 2001) and the capacity-personality framework (Qin et al. 2024, 2025), candidates may perceive AI-enabled selection as unfair due to the technological limitations of AI hiring products and their lack of cognitive and psychological readiness to interact with AI.

To begin with, AI-enabled interviewing products with flaws may lead to the continued underrepresentation of minority groups due to a reliance on technological solutions. This can result in increased unfair treatment. Despite marketing themselves as promoting fairness, AI-enabled hiring tools are facing growing scrutiny regarding their algorithmic bias, operational processes, and potential to diminish workforce diversity. Machine learning used in AI-enabled interviews can perpetuate human biases due to inadequate data or flawed algorithms (Caliskan et al. 2017), which participants report to be even more unfair than human interviews (Acikgoz et al. 2020). AI-enabled interviews can inaccurately categorize and evaluate applicants based on image recognition. While AI recruitment tool companies propose debiasing solutions such as an anonymous mode, which lets hiring managers easily activate or deactivate filters to remove gender or racial identifiers, job candidates are skeptical of these tools. This skepticism arises because AI-enabled interviews fail to address recruiters’ individual biases or the deeply entrenched structural injustices within the companies they represent, potentially leading to further underrepresentation in the workforce (Drage and Mackereth, 2022). As previously mentioned, the operational methods of AI-enabled interviews have sparked controversy, highlighting concerns that AI is not equipped to eliminate bias or avoid perpetuating injustice.

In addition to the technical limitations of AI interview systems, applicants’ lack of cognitive and psychological readiness to interact with AI significantly contributes to their reduced perceptions of procedural justice. The capability–personalization framework (Qin et al. 2024, 2025), which posits that applicants’ acceptance of AI-based processes is shaped by their perceived capability of AI and their perceived need for personalization, offers an appropriate lens to explain why AI interviews are often perceived as less fair. In interview contexts where personalization is expected, applicants may view AI interviews as unfair not solely because of concerns about algorithmic limitations, but because they feel ill-equipped to present themselves effectively or unable to access the same opportunities for self-expression that human-led interviews afford (Kaibel et al. 2019; Lee, 2018). Self-expression—also conceptualized as impression management (Bolino et al. 2016)—is the primary means through which applicants convey their qualifications during interviews. In traditional human-led interviews, applicants engage in various impression management strategies, both honest (e.g., highlighting relevant skills or enthusiasm) and deceptive (e.g., exaggerating experience), to demonstrate their suitability for the role. From this perspective, interviews are not merely assessments of fixed traits, but performative interactions in which applicants actively construct their image through strategic behavior.

As AI-enabled interviewing technologies advance—and as media coverage and emerging research highlight their capabilities—many applicants have come to believe that AI interviewers are more adept than human interviewers at detecting human behaviors. For instance, AI systems are often designed to analyze nonverbal micro-expressions, head movements, vocal tone, and eye movements—cues that are both extremely subtle and difficult for applicants to consciously regulate (Suen et al. 2024). Although applicants may acknowledge the higher detection accuracy of AI systems, they often lack understanding of the algorithms’ inner workings or the specific criteria used to evaluate their responses (Johnson and Verdicchio, 2017). This creates a perceived asymmetry of control: applicants feel scrutinized at a granular level but lack the knowledge to effectively respond or optimize their performance (Kaibel et al. 2019; Lee, 2018). Unlike human interviewers—whose evaluations may be influenced by interpersonal rapport, conversational flow, or expressions of confidence—AI systems “see” more but “signal” less, making applicants harder to anticipate or influence through traditional impression management tactics (e.g., strategic self-promotion, feigned enthusiasm, or social mirroring). This perceived inability to control the interaction may contribute to feelings of procedural injustice—not necessarily because the AI is biased, but because applicants lack the expressive means and feedback loops needed to perform effectively. Relatedly, Suen and Hung (2024) found that when AI interview systems become more transparent—such that applicants understand which behaviors are rewarded or penalized—they tend to adopt more deceptive impression management strategies, tailoring their responses to align with known evaluation criteria. This insight from impression management reinforces the capability–personalization framework (Qin et al. 2024, 2025), suggesting that AI interviews may inadvertently constrain the behavioral space through which applicants signal their value, thereby eliciting perceptions of unfairness—even when the system is technically consistent or unbiased. In other words, when applicants feel that AI systems do not provide them with sufficient means to perform or express their capabilities (i.e., to manage impressions), they are more likely to experience the process as procedurally unfair. In short, applicants perceive AI-enabled interviews as less fair due to a mismatch between their needs for personalized interaction and the standardized, impersonal nature of AI systems, as well as a capability gap, wherein applicants lack the confidence, experience, or skills to perform effectively in unfamiliar, AI-enabled interviews.

Furthermore, Gilliland (1993) suggested that the relationship between human resource policies, adherence to procedural justice rules, and the perceived fairness of selection systems has an impact on various outcomes such as job choice. Empirical evidence supports the idea that the perceived fairness of selection procedures is closely linked to job application intentions during the selection process (Crant and Bateman, 1990; Ployhart and Ryan, 1998; Smither et al. 1993). Applicants who perceive the selection process as unfair are more likely to have lower intentions to accept the job offer (Uggerslev et al. 2012). In contrast to traditional video interviews, AI-enabled interviews may reduce candidates’ perception of procedural justice. Since the perceived fairness of the process is directly associated with outcomes like candidates’ intentions to apply for a job, we propose the following:

H3: Perceived procedural justice mediates the relationship between interview format and job application intention. That is, candidates perceive AI-enabled interviews as less fair, which has a negative impact on their intention to apply for jobs.

During the initial stages of the selection process, the perception of job-relatedness plays a significant role in determining fairness perceptions and subsequently influencing job application intentions (Zibarras and Patterson, 2015). This perception of job-relatedness is a context-specific aspect of the selection process that is influenced not only by the nature of the selection tool itself but also by the specific context in which it is used (Elkins and Phillips, 2000). In the case of AI-enabled interviews, the perceived fairness is tied to industry types. Applicants may view AI-enabled interviews as less job-related because they may find it challenging to assess certain “soft skills” like interpersonal abilities, which can strongly influence interviewer evaluations (Huffcutt et al. 2001). Particularly in cases where technology is not central to the job opening, applicants who are less technologically inclined may perceive technologically proficient individuals as having an unfair advantage with AI-enabled interviews. This mismatch between the industry type and the interview format could potentially discourage job seekers from applying for such jobs. Additionally, according to Gilliland (1993), the job-relatedness of a selection technique (such as interviews or paper-and-pencil tests) significantly influences perceptions of procedural justice, which has been supported by various studies across different occupations and assessment methods (Bauer et al. 2001; Macan et al. 1994; Schmitt et al. 2004; Truxillo et al. 2001; Patterson et al. 2009). In low-tech industries, applicants perceive AI-enabled technology as potentially undermining the validity of the interview (i.e., less job-related) and impeding their ability to perform well during the interview (i.e., less chance to perform, less selection information). Consequently, we argue that job applicants perceive it as fairer for high-tech industries to use AI-enabled interviews as a screening method compared to low-tech industries, leading to a more positive intention to apply for jobs. Based on this understanding, we propose the following:

H4: The interactive influence of interview format and industry type on candidates’ job application intention is mediated by their perceived procedural justice.

The mediating role of organizational attractiveness

The initial attraction of candidates to companies is often influenced by factors that are not part of the conventional recruitment process and occur prior to formal recruitment (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003). Candidates perceive various recruitment-related activities and information (Collins and Stevens, 2002), as well as the characteristics and behavior of recruiters (Rynes et al. 1991; Turban et al. 1998), as indicators of organizational qualities, which may explain the appeal of the organization. In our study, we utilize signaling theory (Rynes et al. 1991) to elucidate how candidate attraction to a recruiting organization can be influenced by signals that emerge during AI-enabled interview processes.

From a strategic signaling perspective, applicants may view AI interviews not merely as a selection tool but as a symbol of the organization’s broader HR philosophy and managerial logic (Acikgoz et al., 2020; Rynes et al. 1991). Specifically, candidates may infer that the use of AI interviews signals a data-centric, standardization-oriented approach prevailing in organizations—potentially at the expense of flexibility and human judgment. They may also assume that AI will be employed beyond hiring—for example, in performance appraisals, career development, and promotion decisions—raising concerns about the recognition of unique strengths or context-specific contributions. Furthermore, applicants might anticipate a work culture that offers limited mentorship, discretion, or opportunities for individualized growth, thereby undermining perceived person–organization fit. In this light, organizational attractiveness is diminished because candidates foresee a future in which they may struggle to thrive or differentiate themselves under an AI-driven management regime. This interpretation also complements Qin et al.’s (2024, 2025) capability–personalization framework: if applicants believe that their unique capabilities cannot be adequately showcased, valued, or fostered within an employer’s AI-enabled systems, their attraction to that employer will decline.

An applicant’s positive and pleasant attitude towards the organization significantly influences their intention to apply. This influence stems from the impact it has on the organizational attractiveness (Gomes and Neves, 2011; Highhouse et al. 2003; Reeve and Schultz, 2004). Job seekers’ perceptions of organizational attractiveness play a crucial role in predicting their intentions to pursue a particular job (Saks et al. 1995). When applicants perceive organizations as attractive during the recruitment process, they are more likely to actively participate and complete the application process (Holm, 2014). However, the increasing use of highly automated AI-enabled interviews may lead to a decrease in organizational attractiveness for applicants, compared to traditional video interviews. Given the strong connection between applicants’ perceptions of organizational attractiveness and their job choice decisions, we propose the following:

H5: Organizational attractiveness mediates the relationship between interview format and job application intention. That is, candidates perceive AI-enabled interviews as less attractive to the organization, which has a negative impact on their intention to apply for jobs.

Viewing the job interview as a signal of how attractive the organization is, job applicants will judge organizational images from selection tools, and make trait inferences about organizations (Slaughter et al. 2004). One critical dimension of individuals’ perceptions of organizations’ personality traits is innovativeness, and companies higher on the innovativeness dimension are perceived to be more interesting, exciting, unique, creative, and original (Slaughter et al. 2004). The level of innovativeness varies depending on the industry, so we aim to investigate the impact of AI-enabled interviews on applicant reactions in both high-tech and low-tech industries. Certain individuals, such as those who are open to new experiences and thrive in dynamic environments, are more drawn to innovative high-tech companies because the company’s traits align with their self-concept and enhance their self-esteem (Dutton et al. 1994; Shamir, 1991; Slaughter and Greguras, 2009). They may also believe that innovative selection methods reflect what the future job at that organization will be like (Langer et al. 2020). However, there are cases where applicants’ perceptions of an organization’s image and the applied selection procedures differ (Gatewood et al. 1993). In contrast to high-tech industries, low-tech organizations are often seen as stable and well-established (Slaughter and Greguras, 2009). Applicants seeking a stable environment may be unsettled by an innovative selection process, which goes against their expectations and negatively affects the organizational attractiveness (Langer et al. 2020). Therefore, we propose that AI-enabled interviews may be more readily accepted in the selection processes of high-tech industries. As job seekers’ inferences about an organization’s traits are linked to organizational attractiveness (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003; Tom, 1971) and job pursuit intentions (Slaughter and Greguras, 2009), they are attracted to organizations where they perceive a good fit with their own characteristics (Chapman et al. 2005). Based on that, we propose:

H6: The interactive influence of interview format and industry type on candidates’ intention to apply for jobs is mediated by organizational attractiveness.

Our conceptual model is presented in Fig. 1.

Method

Experimental design and procedure

We conducted an online scenario-based experiment using a between-subjects factorial design with a 2 × 2 matrix, where we varied the type of industry (high-tech and publishing company) and the type of interview method (traditional video interviews and AI-enabled interviews). In particular, we provided two distinct sets of paragraphs to tailor the content for different industries. For the high-tech sector, for example, we crafted the following passage: “You are interested in pursuing a position at Company A, an esteemed leader in the high-tech industry. This company specializes in delivering cutting-edge, self-assessment-driven, automated, and smart products and solutions to its customers. You believe that your skills, experience, and job expectations align perfectly with this company. The interview process will adhere to online interview guidelines.” In addition, we presented two distinct visuals to represent different types of interviews. To illustrate the traditional video interviews, for example, we depicted a real-life scenario where a human interviewer appears on the screen, resembling an in-person interview, accompanied by descriptive text: “the picture shows the interviewer after testing the camera and microphone, creating a similar experience to offline interviews.”

We utilized an online survey platform called Credamo (https://www.credamo.com/), which is a professional platform widely used by academic studies in China (e.g., Ren et al. 2023), to enlist full-time employees as participants. We applied a criterion of “on the job” to screen the participants, excluding students and retirees. Subsequently, we randomly assigned 203 participants to one of four scenarios and instructed them to envision themselves participating in a job interview. They were provided with information about the company and the interview process, with two factors being deliberately manipulated. Following the reading of the description for a minimum of 25 s, participants were asked to rate a series of questions assessing manipulation check, along with individual measurement items. These questions encompassed factors such as their perceived procedural justice, organizational attractiveness, and intention to apply for the job. The completion of the survey typically took around 5–8 min (with an average time of 308 s and a minimum time of 120 s). As a token of appreciation, each participant received an incentive of 2 RMB upon finishing the entire survey.

Participants

The survey was distributed randomly to participants through the Credamo database. A total of 248 questionnaires were collected, and participants who either failed the screening question or spent an unusually short time were excluded. The final sample consisted of 203 valid participants. Among them, 57.1% were female, and 89.1% had obtained at least a bachelor’s degree. The age range of the participants was between 23 and 58 years old, with an average age of 32 and a standard deviation of 6.40. Of the participants, 57.10% worked in private enterprises (n = 116), while 32% worked in state-owned businesses (n = 65).

Measures

We employed established scales comprising multiple items that had been utilized in prior studies, adapting them as needed to suit our specific circumstances. The initial survey was conducted in English. To translate it into Chinese, we employed the translation and back-translation technique (Brislin, 1970). Throughout the pilot tests, HR professionals offered valuable feedback to refine and finalize the survey. Participants assessed each statement on a seven-point Likert scale, indicating their level of agreement ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

Intention to Apply was measured by five items developed by Highhouse et al. (2003). One sample item was “I would accept a job offer from Company A”, and the Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.895.

Perceived Procedural Justice was measured by six items adopted from Colquitt’s (2001) and Sylva and Mol’s (2009) scales. One example of it is that “I have been able to express my views and feelings during those procedures”, and the Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.776.

Organizational Attractiveness was measured by five items developed by Highhouse et al. (2003). For instance, “For me, this company would be a good place to work”, and the Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.886.

Results

Manipulation check

We utilized two and three items, correspondingly to examine the manipulation of industry type and interview format, respectively. An instance of an industry type question was, “How closely do you perceive the connection between company A and AI?”. Regarding the interview format, we inquired, “To what degree do you believe the interview is influenced by AI?”. Results revealed that the group of high-tech companies showed a significantly higher average score than the group of traditional publishing companies when asked about the type of industry (MHT = 4.88, SDHT = 0.58, MTD = 4.48, SDTD = 1.06, F = 10.75, p < 0.01). Additionally, the groups that utilized AI-enabled interviews also demonstrated a significantly higher average score than the groups that utilized traditional video interviews for the type of interview question (MTV = 4.13, SDTV = 2.15, MAI = 5.88, SDAI = 1.03, F = 55.31, p < 0.01). Utilizing ANOVA analysis to examine the effects of manipulation, it was found that both the industry type and interview format were effectively manipulated.

Hypotheses testing

Table 1 provides an overview of the data by presenting descriptive statistics and correlations. Table 2 displays the outcomes of ANOVAs. According to the information presented in Table 1, AI-enabled interviews displayed significant negative relationships with candidates’ perceived procedural justice, organizational attractiveness, and job application intention.

Testing direct effect

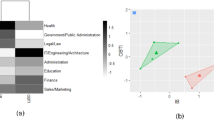

The first hypothesis anticipated that AI-enabled interviews would have a negative impact on job application intention. Through the utilization of a 2 × 2 ANOVA analysis, it showed that the interview format has significant effects on job application intention, as presented in Table 2. The outcomes revealed that AI-enabled interviews decreased job application intention compared to traditional video interviews (MTV = 6.13, SDTV = 0.52, MAI = 5.72, SDAI = 1.21; F(1,199) = 11.08, p < 0.01, η² = 0.05). This supported Hypothesis 1.

Testing direct interactive effect

Simultaneously, according to the data presented in Table 2, the results of a 2 × 2 ANOVA demonstrated that the interview format and industry type interactively impact applicants’ job application intention (F(1,199) = 4.97, p < 0.05, η² = 0.02). This supports Hypothesis 2. As anticipated (Fig. 2), in the context of the publishing industry, interview format has a significant effect on job application intention, and applicants were less likely to apply for jobs when using AI-enabled interviews (MPU-TV = 6.14, SDPU-TV = 0.47, MPU-AI = 5.42, SDPU-AI = 1.59, t = 3.00, p < 0.01). However, there was no significant effect observed in the case of high-tech industry (MHT-TV = 6.13, SDHT-TV = 0.57, MHT-AI = 5.99, SDHT-AI = 0.63, t = 1.20, p = 0.23), so the negative influence of AI-enabled interviews on job application intention was more pronounced for candidates in the publishing industry than in the high-tech industry.

Testing mediating effects

We employed PROCESS macro (Preacher and Hayes, 2008) in SPSS to investigate the mediating role of perceived procedural justice and organizational attractiveness in the relationship between interview format and job application intention. This method involves the use of bootstrap confidence intervals, which are preferred over other conventional methods for assessing the indirect effects of the mediator variable. To account for potential biases in the distribution of the indirect effect, we employed the default setting of 5000 bootstrap samples. The results obtained from this analysis are presented below.

Hypothesis 3 suggested that perceived procedural justice of the interview process mediates the relationship between interview format and intention to apply for a job. As shown in Table 3, our results revealed that perceived procedural justice had an indirect effect of −0.08 (95% CI = [−0.13, −0.04]). Since the confidence interval does not include zero, Hypothesis 3 was supported. Hypothesis 5 proposed that the organizational attractiveness mediates the relationship between the interview format and intention to apply for a job. Supporting Hypothesis 5, the study found a significant indirect effect of interview format on intention to apply for jobs via organizational attractiveness (indirect effect = −0.17, 95% CI = [−0.28, −0.07], excluding 0). In summary, these results revealed that the interview format had significant negative indirect effects on applicants’ intentions to apply for a job via both perceived procedural justice and organizational attractiveness.

Testing mediated moderating effect

We further utilized PROCESS macro in SPSS to test Hypotheses 4 and 6. These hypotheses explored the interaction effect between two variables: type of industry (high-tech industry = 0, publishing industry = 1) and format of interview (traditional video interviews = 0, AI-enabled interviews = 1), on job application intention via perceived procedural justice and organizational attractiveness. Hypothesis 4 and Hypothesis 6 proposed that perceived procedural justice and organizational attractiveness play a mediating role in the interactive effects of interview format and industry type on candidates’ intention to apply for a job. However, according to Table 4, the index of mediated moderation (IMM) of perceived procedural justice (IMM = −0.03, 95% CI = [−0.10, 0.04], including zero) and organizational attractiveness (IMM = −0.15, 95% CI = [−0.36, 0.02], including zero) were not significant. Therefore, both Hypothesis 4 and 6 were not supported. In summary, the indirect effects of interview format on applicants’ intentions to apply for a job—via perceived procedural justice and organizational attractiveness—did not differ significantly between the high‑tech and publishing industries; both industries exhibited significant negative indirect effects.

Discussion

Theoretical implications

Our research provides three contributions.

First, our research contributes to the existing literature on AI-enabled interviews by examining how applicants’ responses differ across high-tech and low-tech industries. As noted by Pan et al. (2022), the effectiveness of AI-enabled interviews is shaped by various contingent factors, including the industry context. In response to this argument, we draw on the capability–personalization framework (Qin et al. 2024, 2025) to explain why applicants’ aversion to AI interviews is mitigated in high-tech industries, and we provide experimental evidence to support this claim. In doing so, our study not only validates the capability-personalization framework but also extends it by introducing industry-specific contextual and psychological mechanisms that influence applicants’ reactions to AI. Furthermore, our research encourages future research to examine how users’ responses to other AI-enabled practices vary across industries, in order to better delineate the boundaries of AI aversion and AI appreciation.

Second, this research deepens our understanding of candidates’ perceptions of procedural justice in AI-enabled interviews by integrating fairness heuristic theory with the capability-personalization framework, impression management, and identity-relevant evaluations. By drawing on the broader body of knowledge, our research offers novel insights into the psychological mechanisms underlying applicants’ perceptions of AI interviews as unfair. Specifically, applicants perceive AI interviews as procedurally unjust not only due to concerns about algorithmic flaws, but also because they feel unable to engage in effective self-presentation. In other words, perceptions of unfairness stem from both a misalignment of capabilities (e.g., lack of preparation for AI interviews) and unmet expectations for personalization (e.g., the absence of human empathy or interaction). Furthermore, the interview process is inherently identity-relevant. Applicants’ discomfort arises not only from a lack of perceived fairness, but also from their perceived inability to demonstrate who they are. This can result in a failure to achieve self-verification and a sense of person-environment misfit, further reinforcing their negative experience. By highlighting these interrelated psychological dynamics, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of fairness perceptions in AI-enabled selection processes.

Third, this research advances our understanding of how AI-enabled interviews diminish candidates’ perceptions of organizational attractiveness by applying signaling theory—specifically, a strategic signaling perspective. Viewed through this lens, AI interviews function not only as evaluative tools but also as cultural and managerial signals, with direct implications for employer branding and applicants’ self-selection decisions. This perspective aligns with the capability-personalization framework (Qin et al. 2024, 2025) and extends its AI-aversion constructs beyond procedural justice in interviews to broader organizational attractiveness among applicants. Finally, we encourage future research to examine how other AI-enabled practices may deter applicants who value mentorship, discretionary judgment, or human connection from engaging with such organizations.

Practical implications

The findings of this research have significant implications for organizations and practitioners. First, the study sheds light on the potential drawbacks of using AI-enabled interviews, highlighting their dual nature. While AI technology has the potential to enhance the selection process, employers and recruiters should be cautious about its disadvantages to prevent misuse. This study suggests that incorporating AI into the interview process may not always yield positive outcomes, as it can lead to applicants withdrawing their interest in the job before even being employed.

Second, organizations and managers should implement strategies to mitigate the negative impact of AI-enabled interviews on applicants’ willingness to apply. Although AI-enabled interviews provide efficiency and standardization, many candidates still value human intuition and contextual judgment in the evaluation process. Applicants may question AI’s evaluative competence in assessing personalized qualities, which can lead to perceptions of reduced fairness and diminished organizational attractiveness. To address this, organizations should consider adopting a hybrid interview model that integrates AI-based assessments with human judgment, thereby enhancing both efficiency and the candidate experience. Additionally, managers should actively communicate and demonstrate the organization’s commitment to human-centered values, even when deploying AI-enabled practices. Doing so can help prevent the perception that the organization prioritizes data-driven standardization at the expense of empathy, discretion, and individual consideration.

Third, it is important for organizations to consider the compatibility between the industry and the interview characteristics. Our research offers novel insights that can assist professionals in comprehending how different industries influence candidates’ reactions to AI-powered interviews. Since AI signifies innovation to a certain degree, companies should assess their technological capabilities to ensure the effective implementation of AI-enabled interviews and reduce applicants’ mistrust. Specifically, low-tech industries encounter greater challenges in dispelling candidates’ preconceived notions about limited technological resources when utilizing AI technology. Therefore, they should utilize this innovative recruitment approach with a higher level of seriousness.

Finally, we recommend that organizations give careful thought to providing user training for both individuals being interviewed and those conducting the interviews in this new situation. From the standpoint of job applicants, the intricacies of AI could pose challenges to the seamless implementation of AI-based interviews during the pre-employment phase. Therefore, it becomes the responsibility of top management to eliminate barriers among non-technical parties, such as applicants and recruiters, to expand the pool of potential candidates. One possible approach is for companies to offer user-friendly training and detailed guidelines to applicants, enabling them to gain a better understanding of AI technology.

Limitations and future directions

Below, we discuss the limitations of our research—including experimental design, sample generalizability, ecological validity, sensitivity to national context, unexplored psychological mechanisms, AI interview format, social desirability bias, and potential boundary conditions—and propose corresponding directions for future research.

First, we employed an online, scenario-based experimental design, which may compromise external validity. Future research should consider conducting field studies to test our model in real-world settings. Second, our participants consisted of registered platform users, limiting the generalizability of our sample. Subsequent studies could recruit participants from alternative populations. Third, we used hypothetical interview scenarios that may not fully capture the emotional and behavioral dynamics of high-stakes, real-world job applications. Future research could employ field experiments or analyze actual applicant data to enhance ecological validity. Fourth, candidates’ reactions to AI interviews may vary depending on a country’s cultural values, AI maturity and regulations. For example, employees’ preference for face-to-face interaction varies across cultures (Randstad, 2012); the EU’s AI Act has led to more cautious adoption, whereas China, Taiwan, and Japan tend to be more open to AI-based interviews (e.g., Suen and Hung, 2024). Since our research is limited to Chinese employees, we encourage cross-country comparisons in future work. Fifth, our model focuses on procedural justice and organizational attractiveness as key mediators of interview format effects, but other mechanisms—such as perceived control, self-efficacy, or trust in AI—may also influence applicant responses. Future studies should examine these alternative or additional mediators. Sixth, we treat AI interviews as a single, uniform condition, yet real AI systems vary in transparency, interactivity, and interface design. Future research could manipulate these configurations to identify which features matter most. Seventh, because our study relies on self-reported measures, responses related to fairness and impression management may be influenced by social desirability bias. We recommend that future research incorporate behavioral metrics or AI-coded data to mitigate this issue. Eighth, although our study focuses on the moderating role of industry, we acknowledge that technology-related individual characteristics—such as AI literacy, technological self-efficacy, or technophobia—may shape how candidates react to AI-enabled practices. We therefore suggest that future research could explicitly measure these individual differences and consider them as moderators in the relationship between AI-enabled practices and applicants’ responses, particularly their fairness perceptions and intentions to apply.

Conclusion

To summarize, the results of this study revealed that AI-enabled interviews have a negative impact on job seekers’ perceptions of procedural justice and organizational attractiveness, as well as their intention to apply for a job. Potential applicants view highly automated AI-enabled interviews in a negative light, so organizations should carefully consider how they implement automation in their hiring processes. In addition to evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of AI-enabled interviews, organizations should also take into account applicants’ perceptions and reactions. Furthermore, the study suggests that the compatibility between industry type and interview format plays a vital role in maximizing the benefits of AI-enabled tools in the application process. Applicants are more likely to apply for jobs in the high-tech industry when participating in AI-enabled interviews compared to low-tech industries.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and are also provided as a supplementary file.

References

Acikgoz Y, Davison KH, Compagnone M, Laske M (2020) Justice perceptions of artificial intelligence in selection. Int J Sel Assess 28(4):399–416

Alsever J (2017) Where does the algorithm see you in 10 years? Fortune 175(7):74–79

Alsheibani S, Cheung Y, Messom C (2018) Artificial intelligence adoption: AI-readiness at Firm-Level. PACIS 4:231–245

Bauer TN, Truxillo DM, Sanchez RJ, Craig JM, Ferrara P, Campion MA (2001) Applicant reactions to selection: development of the selection procedural justice scale (SPJS). Pers Psychol 54:387–419

Bolino M, Long D, Turnley W (2016) Impression management in organizations: critical questions, answers, and areas for future research. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 3(1):377–406

Booth R (2019) Unilever saves on recruiters by using AI to assess job interviews. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/oct/25/unilever-saves-on-recruiters-by-using-ai-to-assess-job-interviews

Brahmana RKMR, Brahmana RK (2012) What factors drive job seekers attitude in using E-recruitment? South East Asian J Manag 7(2):123–134

Brislin RW (1970) Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-cult Psychol 1(3):185–216

Bughin J, Hazan E, Ramaswamy S, Chui M, Allas T, Dahlström P, Henke N, Trench M (2017) Artificial intelligence: the next digital frontier? https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Advanced%20Electronics/Our%20Insights/How%20artificial%20intelligence%20can%20deliver%20real%20value%20to%20companies/MGI-Artificial-Intelligence-Discussion-paper.ashx

Caliskan A, Bryson JJ, Narayanan A (2017) Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science 356(6334):183–186

Chapman D, Uggerslev K, Carroll SA, Piasentin KA, Jones DA (2005) Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: a meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. J Appl Psychol 90(5):928–944

Collins CJ, Stevens CK (2002) The relationship between early recruitment-related activities and the application decisions of new labor-market entrants: a brand equity approach to recruitment. J Appl Psychol 87(6):1121–1133

Colquitt JA (2001) On the dimensionality of organizational justice: a construct validation of a measure. J Appl Psychol 86(3):386–400

Crant JM, Bateman TS (1990) An experimental test of the impact of drug–testing programs on potential applicants’ attitudes and intentions. J Appl Psychol 75:127–131

Cremer DD (2021) Leadership by algorithm. Harriman House

Dietvorst BJ, Simmons JP, Massey C (2015) Algorithm aversion: people erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. J Exp Psychol: Gen 144(1):114–126

Drage E, Mackereth K (2022) Does AI Debias recruitment? Race, gender, and AI’s “eradication of difference”. Philos Technol 35:89

Dutton JE, Dukerich JM, Harquail CV (1994) Organizational images and member identification. Adm Sci Q 39:239–263

Dzindolet MT, Peterson SA, Pomranky RA, Pierce LG, Beck HP (2003) The role of trust in automation reliance. Int J Hum–Comput Study 58:697–718

Elkins TJ, Phillips JS (2000) Job context, selection decision outcome, and the perceived fairness of selection tests: biodata as an illustrative case. J Appl Psychol 85:479–484

Van Esch P, Black JS, Ferolie J (2019) Marketing AI recruitment: the next phase in job application and selection. Comput Hum Behav 90:215–222

Gatewood RD, Gowan MA, Lautenschlager GJ (1993) Corporate image, recruitment, and initial job choice decisions. Acad Manag J 36(2):414–427

Gilliland SW (1993) The perceived fairness of selection systems: an organizational justice perspective. Acad Manag Rev 18(4):694–734

Del Giudice M, Scuotto V, Orlando B, Mustilli M (2023) Toward the human-centered approach. A revised model of individual acceptance of AI. Hum Resour Manag Rev 33(1):100856

Gomes DR, Neves JG (2011) Organizational attractiveness and prospective applicants’ intentions to apply. Pers Rev 40:684–689

Gonzalez MF, Capman JF, Oswald FL, Theys ER, Tomczak DL (2019) Where’s the I–O? Artificial intelligence and machine learning in talent management systems. Pers Assess Decis 5(3):5

Hausknecht JP, Day DV, Thomas SC (2004) Applicant reactions to selection procedures: an updated model and meta-analysis. Pers Psychol 57(3):639–683

Highhouse S, Lievens F, Sinar EF (2003) Measuring attraction to organizations. Educ Psychol Meas 63(6):986–1001

Holm A (2014) Institutional context and e-recruitment practices of Danish organizations. Empl Relat 36(4):432–455

Howardson GN, Behrend TS (2014) Using the Internet to recruit employees: comparing the effects of usability expectations and objective technological characteristics on Internet recruitment outcomes. Comput Hum Behav 31:334–342

Huang T, Liao S (2015) A model of acceptance of augmented–reality interactive technology: the moderating role of cognitive innovativeness. Electron Commer Res 15(2):269–295

Huffcutt A, Conway JM, Roth PL, Stone NS (2001) Identification and meta-analytic assessment of psychological constructs measured in employment interview. J Appl Psychol 86:897–913

Hunkenschroer AL, Lütge C (2021) How to improve fairness perceptions of AI in hiring: the crucial role of positioning and sensitization. AI Ethics J 2(2) https://doi.org/10.47289/AIEJ20210716-3

Jaser Z, Petrakaki D (2023) Are you prepared to be interviewed by an AI? Harvard Bus Rev https://hbr.org/2023/02/are-you-prepared-to-be-interviewed-by-an-ai

Johnson DG, Verdicchio M (2017) AI anxiety. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 68(9):2267–2270

Kaibel C, Koch-Bayram I, Biemann T, Mühlenbock M (2019) Applicant perceptions of hiring algorithms-uniqueness and discrimination experiences as moderators. In: Taneja S (ed). Academy of Management Proceedings

Köchling A, Wehner MC (2020) Discriminated by an algorithm: a systematic review of discrimination and fairness by algorithmic decision-making in the context of HR recruitment and HR development. Bus Res 13:795–848

Langer M, König CJ, Sanchez DR, Samadi S (2020) Highly automated interviews: applicant reactions and the organizational context. J Manag Psychol 35(4):301–314

Lee MK (2018) Understanding perception of algorithmic decisions: Fairness, trust, and emotion in response to algorithmic management. Big Data Soc 5(1):1–16

Li L, Lassiter T, Oh J, Lee MK (2021) Algorithmic hiring in practice: recruiter and HR professional’s perspectives on AI use in hiring. In: Fourcade M, Kuipers B, Lazar S, Mulligan D (eds) Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM conference on AI, ethics, and society. Association for Computing Machinery, respectively, pp 166–176

Li X, Song Z (2017) Recruitment, job search and job choice: an integrated literature review. In: Ones DS, Anderson N, Viswesvaran C, Sinangil HK (eds) The SAGE handbook of industrial, work & organizational psychology. Sage Publications, pp 489–507

Lievens F, Highhouse S (2003) The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company’s attractiveness as an employer. Pers Psychol 56:75–102

Lind EA (2001) Fairness heuristic theory: Justice judgments as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations. In: Greenberg J, Cropanzano R (eds) Advances in organizational justice. Stanford University Press, pp 56–99

Macan TH, Avedon MJ, Paese M, Smith DE (1994) The effects of applicants’ reactions to cognitive ability tests and an assessment center. Pers Psychol 47:715–738

Malik A, Pereira V, Budhwar P (2021) HRM in the global information technology (IT) industry: towards multivergent configurations in strategic business partnerships. Hum Resour Manag Rev 31(3):100743

Manzey D, Reichenbach J, Onnasch L (2012) Human performance consequences of automated decision aids: the impact of degree of automation and system experience. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak 6(1):57–87

McCarthy JM, Bauer TN, Truxillo DM, Anderson NR, Costa AC, Ahmed SM (2017) Applicant perspectives during selection: a review addressing “So what?,” “What’s new?,” and “Where to next? J Manag 43(6):1693–1725

Miller FA, Katz JH, Gans R (2018) The OD imperative to add inclusion to the algorithms of artificial intelligence. OD Pract 50(1):8

Mirowska A, Mesnet L (2022) Preferring the devil you know: potential applicant reactions to artificial intelligence evaluation of interviews. Hum Resour Manag J 32(2):364–383

Oliveira T, Martins MF (2010) Understanding e-business adoption across industries in European countries. Ind Manag Data Syst 110(9):1337–1354

Önkal D, Goodwin P, Thomson ME, Gönül S, Pollock AC (2009) The relative influence of advice from human experts and statistical methods on forecast adjustments. J Behav Decis Mak 22:390–409

Oostrom JK, Holtrop D, Koutsoumpis A, van Breda W, Ghassemi S, de Vries RE (2024) Applicant reactions to algorithm‐versus recruiter‐based evaluations of an asynchronous video interview and a personality inventory. J Occup Organ Psychol 97(1):160–189

Pan Y, Froese F, Liu N, Hu Y, Ye M (2022) The adoption of artificial intelligence in employee recruitment: the influence of contextual factors. Int J Hum Resour Manag 33:1125–1147

Patterson F, Baron H, Carr V, Plint S, Lane P (2009) Evaluation of three short-listing methodologies for selection into postgraduate training in general practice. Med Educ 43:50–57

Pereira V, Hadjielias E, Christofi M, Vrontis D (2023) A systematic literature review on the impact of artificial intelligence on workplace outcomes: a multi-process perspective. Hum Resour Manag Rev 33(1):100857

Ployhart RE, Ryan AM (1998) Applicants’ reactions to the fairness of selection procedures: the effects of positive rule violation and time of measurement. J Appl Psychol 83:3–16

Polites GL, Karahanna E (2012) Shackled to the status quo: the inhibiting effects of incumbent system habit, switching costs, and inertia on new system acceptance. Manag Inf Syst Q 36:21–42

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891

Qin X, Zhou X, Chen C, Wu D, Zhou H, Dong X, Cao L, Lu JG (2025) AI aversion or appreciation? A capability-personalization framework and a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 151(5):580–599

Qin X, Zhou X, Chen C, Wu D, Zhou H, Dong X, Cao L, Lu JG (2024) AI aversion or appreciation? Meta-analytic evidence for a capability-personalization framework. In: Taneja S (ed). Academy of management proceedings

Randstad (2012) Randstad Workmonitor results wave 1: information overload at work? Employees prefer face-to-face contact https://www.randstad.com/press/2012/randstad-workmonitor-results-wave-1-information-overload-work-employees-prefer-face/

Ransbotham S, Kiron D, Gerbert P, Reeves M (2017) Reshaping business with artificial intelligence: Closing the gap between ambition and action. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 59(1):1–17

Reeve CL, Schultz L (2004) Job–seeker reactions to selection process information in job ads. Int J Sel Assess 12:343–355

Reilly P (2018) The impact of artificial intelligence on the HR function. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/516-IES-Perspectives-on-HR-2018.pdf#page=45

Ren S, Sun H, Tang Y (2023) CEO’s hometown identity and corporate social responsibility. J Manag 49(7):2455–2489

Roulin N, Bourdage JS (2023) Ready? Camera rolling… action! Examining interviewee training and practice opportunities in asynchronous video interviews. J Vocat Behav 145:103912

Ryan AM, Ployhart RE (2000) Applicants’ perceptions of selection procedures and decisions: A critical review and agenda for the future. J Manag 26(3):565–606

Rynes SL, Bretz RD, Gerhart B (1991) The importance of recruitment in job choice: a different way of looking. Pers Psychol 44(3):487–521

Saks AM, Leck JD, Saunders DM (1995) Effects of application blanks and employment equity on applicant reactions and job pursuit intentions. J Organ Behav 16:415–430

Sanders NR, Wood JD (2019) The humachine: humankind, machines, and the future of enterprise, 1st edn. Routledge, New York

Schmitt N, Oswald FL, Kim BH, Gillespie MA, Ramsay LJ (2004) The impact of justice and self-serving bias explanations of the perceived fairness of different types of selection tests. Int J Sel Assess 12:160–171

Shamir B (1991) Meaning, self, and motivation in organizations. Organ Stud 12:405–424

Slaughter JE, Greguras GJ (2009) Initial attraction to organizations: the influence of trait inferences. Int J Sel Assess 17(1):1–18

Slaughter JE, Zickar MJ, Highhouse S, Mohr DC (2004) Personality trait inferences about organizations: development of a measure and assessment of construct validity. J Appl Psychol 89(1):85–103

Smither JW, Reilly RR, Millsap RE, Pearlman K, Stoffey RW (1993) Applicant reactions to selection procedures. Pers Psychol 46:49–76

Stone DL, Deadrick DL, Lukaszewski KM, Johnson R (2015) The influence of technology on the future of human resource management. Hum Resour Manag Rev 25(2):216–231

Suen HY, Hung KE (2024) Revealing the influence of AI and its interfaces on job candidates’ honest and deceptive impression management in asynchronous video interviews. Technol Forecast Soc Change 198:123011

Suen HY, Chen MYC, Lu SH (2019) Does the use of synchrony and artificial intelligence in video interviews affect interview ratings and applicant attitudes? Comput Hum Behav 98:93–101

Suen HY, Hung KE, Liu C, Su YS, Fan HC (2024) Artificial intelligence can recognize whether a job applicant is selling and/or lying according to facial expressions and head movements much more correctly than human interviewers. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst 11(5):5949–5960

Sylva H, Mol ST (2009) E‐recruitment: a study into applicant perceptions of an online application system. Int J Sel Assess 17(3):311–323

Tippins NT, Oswald FL, McPhail SM (2021) Scientific, legal, and ethical concerns about AI-based personnel selection tools: a call to action. Pers Assess Decis 7(2):1

Tom VR (1971) The role of personality and organizational images in the recruiting process. Organ Behav Hum Perform 6:573–592

Truxillo DM, Bauer TN, Sanchez RJ (2001) Multiple dimensions of procedural justice: longitudinal effects of selection system fairness and test-taking self-efficacy. Int J Sel Assess 9:336–349

Turban DB, Forret ML, Hendrickson CL (1998) Applicant attraction to firms: Influences of organization reputation, job and organizational attributes, and recruiter behaviors. J Vocat Behav 52(1):24–44

Uggerslev K, Fassina NE, Kraichy D (2012) Recruiting through the stages: a meta-analytic test of predictors of applicant attraction at different stages of the recruiting process. Pers Psychol 65:597–660

Vrontis D, Christofi M, Pereira VE, Tarba SY, Makrides A, Trichina E (2021) Artificial intelligence, robotics, advanced technologies and human resource management: a systematic review. Int J Hum Resour Manag 33:1237–1266

Wang B, Liu Y, Parker SK (2020) How does the use of information communication technology affect individuals? A work design perspective. Acad Manag Ann 14(2):695–725

Wesche JS, Sonderegger A (2021) Repelled at first sight? Expectations and intentions of job-seekers reading about AI selection in job advertisements. Comput Hum Behav 125:106931

Yu X, Xu S, Ashton M (2023) Antecedents and outcomes of artificial intelligence adoption and application in the workplace: the socio-technical system theory perspective. Inf Technol People 36(1):454–474

Zhao S, Zhang M, Zhao Y (2019) A review on the past 100 years of human resource management: evolution and development. Foreign Econ Manag 41(12):50–73

Zibarras LD, Patterson F (2015) The role of job relatedness and self‐efficacy in applicant perceptions of fairness in a high‐stakes selection setting. Int J Sel Assess 23(4):332–344

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 72272002) and the Project of Cultivation for Young Top-Notch Talents of Beijing Municipal Institutions (grant number: BPHR202203037) to Prof. Luo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design, material preparation and data collection were performed by Wenhao Luo and Yuelin Zhang. The manuscript was written by all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of North China University of Technology (approval number: 20220420SEM06) on April 20, 2022. The procedures used in this study adhere to the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Informed consent

Prior to the study (conducted May 12–28, 2022), all participants received detailed information about the study’s purpose and procedures via a consent form. They were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained online from all participants before commencement. This consent covered participation and the use of collected data for academic and research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, W., Zhang, Y. & Mu, M. Why might AI-enabled interviews reduce candidates’ job application intention? The role of procedural justice and organizational attractiveness. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1278 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05607-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05607-z