Abstract

Global land use/cover change (LUCC) critically governs landslide risk through altered surface material dynamics. Despite increasing research focus on this issue, systematic mapping of LUCC-landslide interdependencies and their cascading impacts remains lacking. Our analysis of 102 studies (2002–2024) from Web of Science, Scopus, and Engineering Village outlines three developmental stages in this field: (1) empirical correlation studies (2002–2010), (2) process-based modeling (2011–2018), and (3) risk scenario projections (2019–2024). Key findings establish forest cover transitions and urban expansion as primary susceptibility drivers, whereas other LUCC impacts exhibit context-dependence on land conversion trajectories. Our synthesis highlights four critical research gaps. (1) Mechanistic cognitive gap: over 80% of studies are overly focused on model optimization and neglect physical process elucidation. (2) Geospatial bias: Approximately 80% of studies concentrated in Asia, and less than 5% in high-risk Oceania/South America. (3) Temporal ambiguity: Ambiguity in temporal effects of LUCC interventions (e.g., temporal fluctuations in landslide suppression post-afforestation). (4) Neglected synergistic mechanisms: Inadequate understanding of synergistic mechanisms between LUCC transition chains and natural factors (geological and climatic). This paper proposes a targeted solution to address these limitations and advance the field. Furthermore, a sustainable land management framework is developed, integrating resilience enhancement, risk governance, human-land relationship optimization, and dynamic risk response mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landslides are processes and phenomena involving the deformation and failure of slope rock and soil masses under the influence of gravity and external factors (Gariano and Guzzetti, 2016). Landslides occur due to the interaction between slope geometry, soil and rock characteristics, and surface and groundwater dynamics (Bogaard and Greco, 2016). In many regions, landslides pose a serious threat to populations (Kirschbaum et al., 2015). For instance, Froude and Petley (2018) found that between 2004 and 2016, 4862 landslides resulted in 55,997 fatalities. To reduce landslide risk, identifying and understanding the key factors influencing landslide occurrence is crucial (Pacheco Quevedo et al., 2023), with land use and cover change (LUCC) recognized as one of the most significant factors. International disaster reduction strategies have shifted from site-scale engineering “hard” measures to regional land-use planning restrictions and other “soft” measures, such as limiting land development through land-use planning, which is one of the most effective means of preventing geological disasters (Leroi et al., 2005). Therefore, understanding and measuring the relationship between LUCC and landslides is a prerequisite for reasonable land-use planning to prevent landslide disasters.

It is essential to clarify that land cover (LC) refers to the natural or anthropogenic physical characteristics of the earth’s surface (e.g., vegetation, water bodies, and built-up areas), while land use (LU) emphasizes the functional utilization of land by humans (e.g., agricultural cultivation, urban construction, and forestry development). LUCC integratively reflects the dynamic evolution processes of both concepts, embodying the disturbance of human activities in the natural environment (Ren et al., 2019). It has been identified as a primary driver of local, regional, and global environmental changes (Gill and Malamud, 2017; Verburg et al., 2015). In recent decades, LUCC has intensified globally, including deforestation, road construction, fire, steep slope cultivation, and urban expansion. These changes alter existing hydrogeological structures and geomorphological conditions, significantly affecting landslide susceptibility and spatial distribution (Nkonya et al., 2016; Ozturk et al., 2022; Sidle and Bogaard, 2016). For example, vegetation can protect soil from erosion and improve slope stability through mechanical anchoring and root system absorption (Löbmann et al., 2020; Parra et al., 2021). However, the impact of LUCC on landslides is complex and variable, with different types of land use changes potentially affecting landslide risk to varying degrees and in different directions.

In 2010, landslide disasters affected nearly 2.5 million people, leading to a rapid increase in the number of scientific papers involving landslides and land use (Fig. 1). Notably, the vast majority of these studies treated land use/cover as a static factor, ignoring the fact that land use/cover can change significantly in just a few years (van Westen et al., 2008). With the rapid development of remote sensing technology and machine learning, an increasing number of scholars advocate for considering the dynamic changes of land use/cover in landslide analysis (Gariano et al., 2018; Pisano et al., 2017). In recent years, more than 10 articles on LUCC-landslide research have been published annually (Fig. 1).

Although the impact of LUCC on landslides has become a hot topic in academia, there are relatively few comprehensive review studies on this subject. Glade (2003) reviewed case studies in New Zealand, primarily discussing how changes in forest cover affect landslide activity and highlighting the need for further empirical research. Pacheco Quevedo et al. (2023) conducted a bibliometric analysis of 536 articles from 2001 to 2020, exploring the role of land use/cover in landslide susceptibility studies, emphasizing the potential of future LUCC scenario analysis. However, these reviews mainly focus on specific regions or aspects, lacking a comprehensive and systematic overview of the impact of LUCC on landslides.

This review provides a comprehensive and systematic examination of the existing literature on the LUCC-landslide relationship, aiming to: (1) evaluate the development trends of LUCC-landslide research and identify similarities and differences among research clusters; (2) link the geographical distribution of LUCC-landslide studies with global landslide hotspots to identify regions that should be prioritized in future research; (3) organize and categorize existing analytical methods, discussing the strengths and weaknesses of each approach to clarify the most appropriate methods for future studies; and (4) summarize the impact of key LUCC types on landslide susceptibility and their temporal effects, while compiling future landslide susceptibility predictions. Based on these analyses, we highlight the causes of uncertainty in LUCC’s impact on landslide disasters and discuss the current research limitations and future challenges. Finally, we integrate existing research findings and international successful case studies to propose a comprehensive sustainable land management framework, aiming to provide scientific evidence for reducing landslide risks and promoting sustainable land management.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

This study follows the principles of The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2010). The Web of Science Core Collection, used in this study, is recognized as one of the most popular and authoritative platforms for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” were applied in various combinations to enhance search comprehensiveness. The search query used in this study was: (“land use change” OR “land cover change” OR “land use and cover change” OR “LUC” OR “LUCC” OR “LULCC”) AND (“landslide” OR “landslides”).

Data eligibility criteria

This review established several inclusion criteria, including (i) publication years between 2000 and 2023, (ii) original research articles exploring the relationship between LUCC and landslides (academic papers involving the design of research protocols, collection of original data, analysis of data, and presentation of novel findings or conclusions), and (iii) final or published versions in English. On the other hand, this review considered several exclusion criteria, including: (i) duplicate papers, (ii) publications that are not original research outputs, (iii) languages other than English, (iv) studies that only contain relevant keywords but focus on topics beyond the LUCC-landslide relationship, and (v) studies that treat LUCC as a static factor, such as those that consider land use type only as an indicator of landslide susceptibility. These inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to identify relevant records for this systematic review.

Literature search results

This review followed the PRISMA guidelines, which involve three main stages for literature inclusion: identification, screening, and inclusion (Fig. 2). In the first stage (identification), a total of 3392 records were retrieved from the Web of Science, Scopus, and Engineering Village. Subsequently, a duplicate check was performed, and 1390 records were removed. The second stage (screening) consisted of three main parts: screened records, reports sought for retrieval, and reports assessed for eligibility. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 1813 records were excluded. The primary reasons for exclusion included incorrect publication years, review articles, and studies that contained relevant keywords but were not aligned with the review objectives. The full reports or complete texts of the remaining records that met the screening criteria were obtained for further evaluation. For eligibility assessment, 189 papers remained in the third part of the second PRISMA stage and were selected for full-text review. Additionally, 21 relevant papers were identified and included from reference lists during the review process. After assessing 210 full texts, 108 papers were excluded as they did not consider the dynamic relationship between LUCC and landslides. Finally, in the inclusion stage, 102 papers were selected for the systematic review.

Literature analysis methods

The selected research papers were organized in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, containing details such as publication year, title, author names, study area, keywords, publisher, journal, control parameters used, model types applied, and research findings. Keyword analysis was conducted using VOSviewer 1.6.19 and CiteSpace 6.3.R1 to analyze the development trends in LUCC-landslide research. Methods and study areas used in each article were reviewed manually. The geographical distribution of the literature was mapped using ESRI ArcGIS PRO 3.0.0. This study analyzed the changes in research patterns, key LUCC impact factors, as well as the strengths and limitations of the methods employed. Research gaps were identified, future research directions proposed, and a land management framework to reduce landslide disaster risk was presented.

LUCC and landslide research overview

This section aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the land use and cover change (LUCC) and landslide relationship research landscape, offering an in-depth understanding of the development trends, research clusters, geographical distribution of literature, and methodological trends in this field.

Development trend

Figure 3 illustrates the development dynamics of LUCC and landslide research from 2002 to 2024. Overall, the methods for assessing the relationship between LUCC and landslides have become more accurate, intelligent, and integrated. Research on the relationship between LUCC and landslides has deepened, especially regarding the specific impacts of different LUCC types on landslides, such as urbanization (Myint Thein et al., 2023) and vegetation changes (Xiong et al., 2023) are significant areas of focus. Based on publication volume, research methods, and areas of focus, LUCC-landslide studies can be divided into three stages:

-

(1)

Early stage (2002–2011): This stage predominantly utilized qualitative analysis and satellite imagery to assess the impact of LUCC on slope stability and landslide frequency. Literature was limited during this period, and while multiple factors (such as rainfall conditions and topographic parameters) were considered in interaction with LUCC, the methods and technologies were underdeveloped, and the study areas were relatively small. Landslide susceptibility was mentioned but not quantitatively assessed during this stage.

-

(2)

Developmental stage (2012–2018): In this stage, more sophisticated statistical strategies were employed to model landslide susceptibility and predict future scenarios. Traditional statistical methods and simple machine learning models were frequently used. Most studies focused on using LUCC remote sensing data for landslide susceptibility mapping and began to incorporate landslide risk assessments.

-

(3)

Outburst stage (2019–2024): More accurate integrated models were developed to assess the susceptibility of landslides and the influence of LUCC. Deep learning techniques became widely used for landslide susceptibility mapping during this period. Researchers were increasingly focused on constructing more complex, integrated machine-learning models. Due to advancements in methodology and technology, the relationship between LUCC and landslides has been more deeply analyzed and quantified.

Research clusters

Through co-occurrence analysis of keywords, we present the distribution characteristics of research hotspots on the relationship between land use change and landslides (Fig. 4). Among the 102 papers, a total of 589 keywords were identified and inconsistencies were corrected. We focused on 27 keywords that appeared at least five times. The co-occurrence network and burst analysis of the keywords revealed three intersecting research clusters in Fig. 4a.

a Co-occurrence network map of keywords. Nodes represent keywords, and their size is proportional to the frequency of occurrence. The colors of the nodes denote different clusters, and the lines between nodes indicate co-occurrence relationships. b Top 20 keywords with the strongest citation bursts. The red segments on the timeline represent the period during which a keyword experienced a burst of citation activity.

Green cluster

This cluster focuses on landslide susceptibility modeling, with core high-frequency terms such as “land use change”, “susceptibility assessment”, “hazard assessment”, “modeling”, and “neural network”. This approach emphasizes methodological innovation and application, using advanced models like machine learning (e.g., neural networks) to quantitatively analyze how land use change affects landslide susceptibility. Research in this cluster typically employs large-scale geographic data and aims to improve prediction accuracy and model optimization, making it suitable for macro-level landslide risk identification and management.

Red cluster

This cluster revolves around the relationship between climate change and forest cover changes, with key terms including “climate change”, “land cover change”, “slope stability”, “deforestation”, and “future scenarios”. It focuses on long-term trends under global and regional climate change, exploring how deforestation and land cover changes may impact landslide frequency and severity. These studies are often found in scenario forecasting and policy recommendations, emphasizing the cumulative effects of environmental changes and offering valuable insights for climate policies and ecological protection strategies.

Blue cluster

The blue cluster focuses on local drivers of landslides, with frequently occurring terms such as “landslides”, “river”, “rainfall”, and “prediction”. These studies in this cluster have focused on exploring how small-scale factors such as river systems, topography, and soil types influence the occurrence of landslides. These studies typically involve field surveys or laboratory data and provide high-precision analysis of local terrain conditions, making them suitable for landslide risk assessment and engineering protection designs in specific areas.

All three clusters address landslide susceptibility and its driving factors, emphasizing the impact of land use and climate change on landslide risk while using modeling and prediction techniques to improve landslide risk management. The differences lie in the focus of each cluster: the blue cluster primarily centers on local factors such as geology and topography between 2002 and 2015 (Fig. 4b), suitable for studying local mechanisms on a small spatial scale. The green and red clusters have extended from around 2010 to the present. The green cluster focuses on improvements in modeling methods, with a strong technical orientation and an emphasis on large-scale data analysis, representing the mainstream approach in LUCC-landslide research today. The red cluster, on the other hand, focuses on the long-term effects of climate and ecological changes, with a macro-level perspective and policy-oriented approach. Given the growing intensity of climate change, accurate forecasting of future landslide risks is becoming a trend. These three clusters complement each other, from macro-level trends to micro-level mechanisms, contributing to a multi-level understanding of the relationship between land use/cover change and landslides.

Geographical distribution of literature

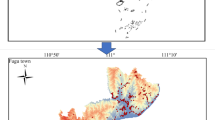

Figure 5 displays the research regions, methodologies, and publication years of the 102 papers. A total of 33 countries across five continents are involved, with China (25 papers, 2013–2024), India (16 papers, 2016–2024), and Italy (12 papers, 2007–2014) leading the number of studies in these regions.

Geographic distribution of landslide-LUCC studies and landslide points (The dataset is provided by the National Cryosphere Desert Data Center. http://www.ncdc.ac.cn).

Other countries have fewer than five articles, and 17 countries have only one article each. While this does not necessarily mean these regions lack landslide-related research, it indicates that articles focusing on landslides through the lens of LUCC are relatively few. This trend deviates from the international disaster reduction strategy that advocates for “regional land planning and restriction measures to prevent geological disasters” (Leroi et al., 2005).

Moreover, Fig. 5 illustrates the spatial distribution of landslide points from 1915 to 2021, which highlights the geographical bias in research areas. Landslide points are mainly concentrated along continental plate boundaries or seismic zones. Countries with a high number of landslide points include China, the United States, the United Kingdom, Nepal, the Philippines, India, and New Zealand. Interestingly, some countries with numerous landslide points, such as the United Kingdom, Peru, and Australia, have not been studied for LUCC and landslides. Other countries, while included in the research, have few studies, often from earlier years (e.g., Ecuador, Mexico, Korea, Uganda, etc.).

Analytical methods for evaluating the influence of LUCC on landslides

Due to the lack of sufficient information, there is some uncertainty in accurately categorizing the methods described in some papers. Among the 102 reviewed papers, a total of 36 different analytical methods (names provided by the authors) were used, with most studies employing two or more methods simultaneously. These methods are categorized into three groups (Data-driven methods, Physic-driven methods, and Mixed-driven methods), with significant differences in their usage frequency.

Data-driven methods (84 papers)

These methods primarily involve collecting and analyzing landslide-related data, such as historical landslide events, LUCC data, meteorological data, etc., and using statistical methods and machine learning models to analyze the relationship between LUCC and landslides. These methods are also used for landslide susceptibility assessment and risk prediction (e.g., logistic regression, random forest).

Physic-driven methods (14 papers)

These methods are based on an understanding of landslide formation mechanisms. They involve using physical laws and equations from fields such as geomechanics and fluid dynamics to build models that simulate the landslide process (e.g., Slope stability model, Dyna-CLUE model).

Mixed-driven methods (4 papers)

These are hybrid modeling strategies that combine the advantages of both data-driven methods and physic-driven methods. They include physically-informed data-driven methods and data-assisted physical models.

Table 1 presents the most frequently used methods during different stages of research. Traditional methods in the Data-driven methods group, such as GIS technology and Frequency ratio, are concentrated in the earlier stages. However, with the development of machine learning technologies, since 2019, machine learning models (e.g., random forest, neural networks) have been increasingly used. Physic-driven methods and Mixed-driven methods have a smaller share and appear across different stages.

Data sources and method transferability

Among the 102 studies reviewed, approximately 80% relied on public datasets to generate LUCC data—satellite remote sensing datasets such as Landsat, Sentinel, and MODIS were widely utilized. While these datasets offer cross-regional comparability, their accuracy may decrease in areas with complex topography (Dubovik et al., 2021). Approximately 20% of studies enhanced data reliability through region-specific customization methods (e.g., UAV imagery, airborne radar), effectively improving regional data accuracy.

The methodologies for compiling landslide inventories provide data support for cross-regional research. Approximately 70% of studies construct landslide inventories through multi-source data integration. For example, a study in the Indian Himalayas integrated field surveys, Google Earth, and the Bhukosh website to generate an inventory containing 850 landslides (Tyagi et al., 2023). In a Romanian study, landslide data were obtained from the ELSUS-Romania database, the General Inspectorate for Emergency Situations (IGSU) database, and archival records of the Technical University of Civil Engineering of Bucharest (Jurchescu et al., 2023). These inventory data typically cover multi-dimensional information such as landslide locations, scales, and triggering factors. Their standardized construction processes (e.g., visual interpretation based on high-resolution remote sensing, field validation) provide a referable methodological framework for risk assessment in other regions.

Notably, data used in most studies are obtained from authors upon request, while very few studies directly provide openly accessible tools or datasets. Despite this, existing research has established analytical frameworks for the LUCC-landslide relationship through models such as random forests and artificial neural networks, providing methodological insights for model replication in comparable regions.

Influence of LUCC on landslide hazards

Key factors of LUCC and temporal effects

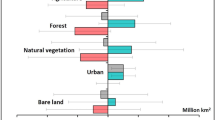

Figure 6 presents the trends and time scales of landslide susceptibility and changes in land use types, as well as the key factors influencing the variation in landslide susceptibility. For statistical convenience, Fig. 6 only shows the overall trend of susceptibility (for example, if the increase in the high susceptibility area is greater than the decrease in the low susceptibility area, the overall susceptibility is considered to have increased).

First, urban expansion is one of the significant factors contributing to the increase in landslide susceptibility. When urban areas expand, about 68% of the studies report an increase in landslide susceptibility, 12% report a decrease, and 20% report uncertainty. Urban expansion is typically accompanied by a reduction in vegetation cover and the construction of roads and other infrastructures, which weakens the surface stability and increases the risk of landslides (Bozzolan et al., 2023; Chuang and Shiu, 2018; Promper et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2022).

Second, the reduction in forest cover is another key factor driving the increase in landslide susceptibility. In areas where forest cover decreases, 90% of the studies report an increase in landslide susceptibility. Vegetation roots reinforce soil cohesion and play a positive role in maintaining soil hydrological balance and slope stability (Depicker et al., 2021b). Only a few studies found no significant relationship between forest cover loss and landslides (Hasnawir et al., 2017; Knevels et al., 2021).

Third, the relationship between the increase in agricultural land area and landslide susceptibility remains unclear. With an increase in agricultural land, about 78% of studies report an increase in landslide susceptibility. However, when agricultural land area decreases, approximately 60% of the studies also report an increase in susceptibility. The relationship may be influenced by factors such as agricultural practices and crop types (Knevels et al., 2021).

Finally, a few studies found that an increase in water bodies (about 7%) and an increase in bareland areas (about 11%) corresponded with an increase in landslide susceptibility. Some studies did not identify a clear trend in landslide susceptibility (about 19%), suggesting that susceptibility is more closely related to other factors such as rainfall, geology, and topography (Pham et al., 2022; Sur et al., 2021; Vuillez et al., 2018).

Further analysis of the relationship between LUCC and landslide susceptibility reveals key LUCC factors related to human activities (Fig. 6e). Deforestation, urban expansion, road network expansion, reservoir construction, and land abandonment are key factors that increase landslide susceptibility, while afforestation and the reduction of bare land area contribute to decreasing susceptibility.

We attempted to examine how the impact of LUCC on landslide susceptibility changes over time. However, the low proportion of cases where landslide susceptibility decreased during each time span made the results statistically insignificant. Nonetheless, LUCC is a dynamic process, with different land use types undergoing transitions. Climate and human activities can either accelerate or decelerate this transition process, and the hydrological and geological changes caused by these transitions affect landslide behavior across various time scales. For example, Rohan et al. (2023) emphasized that LUCC has a long-term impact on landslide susceptibility, which may lead to underestimation of the role of LUCC on shorter time scales. After deforestation, the role of root networks in soil and water conservation persists for some time, but heavy rainfall can shorten this process (Ehigiator and Anyata, 2011). Similarly, artificial plantations also require time to stabilize slopes. This may be one of the reasons Zhang et al. (2023a) observed that landslide risk increases with the expansion of forested areas.

Thus, LUCC’s impact on landslides involves both time lag and cumulative effects, but these effects are not yet fully understood. Due to the heterogeneity in geology, topography, and climate conditions across study regions, it is difficult to compare the effects of LUCC on landslides across different time scales while controlling for other variables. Quantifying the time effects of LUCC on landslides within the same study area provides more reliable results. However, there is currently a lack of systematic research on the temporal differences in LUCC’s impact on landslides at different time scales, which severely hampers landslide risk prediction.

Future prediction of landslide susceptibility based on LUCC

Urbanization and industrialization are accelerating due to population growth and increasing urban demands (Ul Din and Mak, 2021). Predicting the future impacts of LUCC on landslide susceptibility is crucial for risk assessment, early warning systems, and resource management. Future LUCC scenario predictions have become a focal point in research (Ren et al., 2019). However, relatively few studies focus on future LUCC impacts on landslides (Fig. 7). These studies use various models, scenarios, and prediction years, leading to diverse outcomes. For instance, Zeng et al. (2023) simulated LUCC in Zhejiang Province, China, from 2010 to 2060 using a patch-based land use simulation model. They combined Random Forest, Extreme Gradient Boosting, and Light Gradient Boosting models to calculate landslide susceptibility, finding increased potential due to future road networks and urban expansion. Jurchescu et al. (2023) simulated LUCC in Romania from 2013 to 2075, using qualitative and quantitative statistical assessments to evaluate LUCC impacts on landslide susceptibility, revealing varying susceptibility changes based on different LUCC types. Tyagi et al. (2023) used Artificial Neural Networks and Cellular Automata to simulate LUCC in Tehri, India, for 2050 under four socio-economic pathways, predicting increased landslide susceptibility. Aslam et al. (2023) simulated LUCC in parts of Pakistan for 2026 and 2030 using the MOLUSCE plugin, mapping debris flow susceptibility with a linear attack model, and foreseeing increased susceptibility in highly vulnerable areas. Conversely, Guo et al. (2023) used the Land Change Modeler (LCM) in IDRISI Selva software to simulate LUCC in Wanzhou County, China, from 2010 to 2100 across six scenarios, concluding an overall reduction in landslide susceptibility due to future LUCC changes.

It is noteworthy that these results hold significant implications for future land planning and landslide disaster prevention. However, several factors may affect the accuracy of future landslide susceptibility predictions. These include the assumption that key factors remain constant over time, the exclusion of certain static (e.g., land tenure) or dynamic drivers (e.g., socio-economic changes), potential misclassification in land use classification databases, and the relatively short time span for historical LUCC calculations. Additionally, the number of studies on future susceptibility predictions remains limited, and regions with high landslide risk (e.g., high-altitude mountains, earthquake zones) and areas with rapid LUCC changes (e.g., developing countries) have largely been under-researched.

Gariano and Guzzetti (2016) summarized the impact of climate change on landslides and made predictions about landslide activity in certain regions, including the Alps, the Himalayas, the Andes, and the East African Rift, finding that landslide activity will likely increase in most areas. They argue that climate change does not directly affect landslides but rather influences LUCC and the geological environment. Therefore, further exploration of the relationship between LUCC and landslide changes in these regions would be crucial for addressing landslide disaster risks under climate change.

Figure 7 suggests that future landslide susceptibility may not be optimistic, primarily due to changes in forests, agricultural land, and built-up areas. With the continued reduction in forest coverage, urban expansion, and mismanagement of agricultural land, landslide susceptibility in some regions is expected to increase. Implementing a sustainable land use framework is crucial for reducing landslide susceptibility and enhancing resilience to future landslide disasters.

Discussion

Advantages and drawbacks of existing methods

The different approaches used to assess the relationship between land use and cover change (LUCC) and landslides possess unique advantages and significant limitations that should be considered.

First, data-driven methods in the study of LUCC and landslide relationships have undergone significant evolution, from simple linear analysis to complex nonlinear models. This reflects a paradigm shift towards data-intensive and computationally intensive approaches. Before 2019, classical statistical methods dominated the field. For example, univariate analysis (Wasowski et al., 2010), spatial statistical analysis (Xin et al., 2023), and frequency ratio (Sangeeta and Singh, 2023) were commonly used to assign susceptibility weights based on the frequency distribution of landslide occurrences. However, these methods were not strictly based on probability distributions. Although methods like logistic regression and correlation analysis provided statistical explanations, they had limitations in handling non-linearity and data dependencies (Ciurleo et al., 2017; Merghadi et al., 2020).

With the popularization of machine learning, decision trees and neural networks have played a greater role in enhancing nonlinear fitting and geospatial pattern recognition (Ij, 2018). However, it is essential to note some limitations when using machine learning models. For example, in small-sample scenarios, random forests are prone to overfitting due to imbalanced feature space dimensions, while regularization parameter optimization in gradient boosting trees (e.g., XGBoost) relies on manual tuning experience (Merghadi et al., 2020). In terms of interpretability, the “black-box” nature of traditional neural networks makes it difficult to reveal the specific impact pathways of LUCC factors (e.g., vegetation fragmentation, construction land expansion) on landslide-prone environments. Emerging explainability tools in recent years have offered breakthroughs in this regard. For example, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) quantifies feature contributions through game theory principles, enabling visual representation of the marginal impacts of different LUCC types on landslide susceptibility (Pradhan et al., 2023). Regarding the scientific validity of model validation, studies need to strengthen stratified temporal cross-validation strategies. In small-sample regions, 5-fold stratified sampling (Stratified k-fold CV) should be employed to ensure that the proportion of landslide samples in training and test sets matches the actual geographic distribution (Roy and Saha, 2022). Combined with transfer learning techniques, these methods can effectively alleviate the data scarcity issue. For instance, pre-trained ResNet models can be employed to transfer remote sensing image features, while generative adversarial networks (GANs) can be used to augment simulated landslide samples (Al-Najjar and Pradhan, 2021).

In the context of cutting-edge technology integration, Transformer architecture and reinforcement learning (RL) are driving the field into an intelligent phase. The former captures complex dependency relationships in long-term temporal remote sensing data through self-attention mechanisms, having demonstrated exceptional spatio-temporal feature modeling capabilities in fields such as vegetation dynamics evolution and urban expansion simulation (Li et al., 2024). Its technical logic can be transferred to the analysis of lag effects in LUCC-induced landslides—for example, decoding the temporal correlation patterns between vegetation coverage decline and slope stability changes. RL optimizes remote sensing image classification strategies through a “state-action-reward” mechanism, enabling adaptive adjustment of spectral feature combinations in LUCC monitoring (Liu et al., 2024b). This provides a methodological reference for multi-source data fusion in LUCC and landslide research.

Secondly, physics-driven methods, based on the physical principles of landslides and mechanical models, assess landslide susceptibility by simulating geological processes. These methods can offer the highest prediction accuracy and are suitable for mapping and analysis in local or small-scale areas. Although physics-driven methods are theoretically reliable, only a small percentage of studies (approximately 14%) have employed them to investigate landslide susceptibility. The limited research scope, difficulty in data acquisition, and computational complexity are key factors hindering the widespread use of physics-based models for large-scale landslide susceptibility mapping (Guo et al., 2023; Yong et al., 2022).

The combination of both physics-driven and data-driven methods is a cutting-edge trend in Earth sciences. However, this hybrid approach is still rare in LUCC-landslide research (approximately 5%) and is typically limited to a simple overlay of physical models with data-driven approaches. For instance, Van Beek and Van Asch (2004) integrated a transient distributed hydrological model with a slope stability model using spatial statistical analysis to evaluate landslide susceptibility. Another approach involves a hierarchical relationship, where landslide susceptibility zones are initially determined using the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), and then a Scoops 3D model is used for finer-scale assessment (Rashid et al., 2020). In theory, hybrid approaches combine the theoretical foundation of physical models with the efficient processing capabilities of data-driven methods, offering more accurate and comprehensive landslide susceptibility assessments (Tehrani et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2024). For example, compared with traditional methods of randomly selecting negative samples, a negative sample extraction method based on physical models significantly improves the accuracy and reliability of the model (Liu et al., 2024a), demonstrating the potential of hybrid-driven methods in landslide susceptibility analysis. However, there is still a long way to go in applying these methods in LUCC-landslide studies. A critical challenge lies in how to incorporate LUCC parameters into physical models. LUCC parameterization faces difficulties related to the complexity of physical models, the dynamic nature of LUCC, differences in temporal and spatial scales, the sensitivity of physical model parameters, model adaptability, and a lack of effective coupling methods (Michetti and Zampieri, 2014). To address these challenges, it is necessary to develop multi-scale, multi-process coupled models, improve model flexibility and adaptability, and refine the acquisition of multi-source heterogeneous data.

The uncertain influence of LUCC on landslide susceptibility

As shown in Fig. 6, the impact of different LUCC types on landslide susceptibility varies. The main reasons for this variation include the following.

(1) Uncertainty in the impact of land use conversions on susceptibility. For example, the effects of converting “shrubland to grassland” and “shrubland to forest” on landslide susceptibility are quite different. Shrublands are typically more developed than those of herbaceous plants, allowing them to penetrate deep into the soil and form a complex network that enhances soil shear strength and erosion resistance (Lann et al., 2024; Löbmann et al., 2020). However, this effect is usually intermediate between grassland and forest. When shrubland is converted to grassland, the reduction in shallow roots can decrease the stability of surface soils (Caviezel et al., 2014). In contrast, the conversion of shrubland to forest is generally considered to enhance slope stability, but this process is gradual (Manchado et al., 2022). However, there is currently a lack of in-depth discussion on the relationship between land use transitions and landslide susceptibility. As humans rapidly transform the Earth’s surface, land use can change in a short period (Ren et al., 2019). In this context, it is crucial to conduct further research on the impact mechanisms of land use transitions on landslide behavior for accurate susceptibility assessment and prediction.

(2) LUCC’s impact on landslide susceptibility is not isolated but interacts with other factors such as topography, geology, climate, and soil (Pham et al., 2022; Sur et al., 2021; Vuillez et al., 2018). For example, wind force applied to tree canopies increases the shear stress on the slope. At the same time, slope steepness increases the downward shear stress on the trees, and when combined with rainfall, it leads to the erosion of the soil, ultimately resulting in landslides (Lann et al., 2024; Pawlik, 2013). As climate change intensifies, the synergistic effects of altered precipitation patterns, extreme weather events, and LUCC on landslide risk are gradually increasing. For example, in regions with alternating extreme drought and heavy rainfall (e.g., Brazil, China, Iran, etc), overgrazing or cropland expansion leads to grassland degradation, reducing the soil-stabilizing capacity of vegetation roots. The development of soil cracks during drought periods and infiltration erosion during subsequent heavy rains creates a “dry-wet cycle” stress, triggering abrupt changes in the mechanical properties of slope soil and initiating large-scale shallow landslides (Lian et al., 2022). In areas where the frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall are increasing, such as the Alps, the Himalayas, and other regions, shallow landslides, rockfalls, debris flows, and avalanches are also gradually increasing (Gariano and Guzzetti, 2016). In the tropical rainforest regions of Southeast Asia, large-scale deforestation has led to increased surface runoff and reduced soil shear strength. When combined with short-duration heavy rainfall brought by tropical cyclones, the landslide risk has significantly increased compared to the original forest areas (Lehmann et al., 2019). Therefore, in the assessment of landslide susceptibility, it is necessary to construct a differentiated analysis framework based on regional characteristics to reduce evaluation biases caused by differences in regional mechanisms.

In landslide susceptibility assessments, it is crucial to consider the interaction between LUCC and other factors—either through qualitative methods (e.g., sensitive factor models or qualitative reasoning) or quantitative approaches—because it helps reduce the bias caused by the actual variability of susceptibility patterns.

(3) The effect of LUCC on landslide susceptibility is mediated by human activities. For instance, the abandonment of agricultural land leads to intensified soil erosion and water loss, increasing landslide susceptibility (Dandridge et al., 2023). On the other hand, good agricultural practices can positively impact slope stability (Gariano et al., 2018; Knevels et al., 2021; Pisano et al., 2017). Soil conservation measures in farmlands and the construction of terraced slopes can effectively slow down surface runoff concentration and soil saturation. Furthermore, reasonable urban planning and slope protection technologies, such as vegetation-based slope protection or retaining walls, can significantly reduce the negative impacts of engineering disturbances.

These interwoven factors further complicate the relationship between LUCC and landslide susceptibility. This complexity not only increases the difficulty of modeling landslide susceptibility but also raises higher requirements for related decision support systems. Encouragingly, recent research has gradually advanced in this direction: the coupling of LUCC with other factors is becoming better understood (Pacheco Quevedo et al., 2023), and multi-factor landslide susceptibility prediction models based on machine learning are gradually maturing (Agboola et al., 2024).

Limitations and future challenges

Based on the analysis of the research field above, we summarize the following limitations and future challenges:

-

(1)

Through the analysis of research clusters and methods, it is evident that most studies focus excessively on model stacking, parameter optimization, and model comparisons while downplaying discussions on the nature, explanation, and dynamic characteristics of LUCC’s impact on landslide susceptibility. Currently, the integration of physical and data-driven methods is gaining popularity in earth science research (Youssef et al., 2023). We should optimize data models based on a better understanding of the physical mechanisms between LUCC and landslide disasters. Through experiments and field observations, it is essential to study how land use types alter key processes such as rainfall infiltration, soil saturation, and slope stress distribution (Zhang et al., 2023b). These physical mechanisms can then be parameterized and incorporated into data-driven models to form an innovative “physics and data” hybrid model (Liu et al., 2024a).

-

(2)

To address the disconnect between research and landslide-prone areas, it is crucial to strengthen comprehensive studies on global landslide risk zones, particularly in regions where LUCC and landslide disasters are frequent, such as the United Kingdom, Peru, and Australia. International collaboration is an excellent option, but compared to other research fields, international cooperation in Earth sciences is relatively weak (Ye et al., 2024), and thus, scholars need to work together. We advocate for the establishment of a global landslide database through international cooperation and data sharing, and the formulation of unified data standards and sharing mechanisms. We can leverage the big data integration capabilities of platforms such as Google Earth Engine and combine the topographic, climatic, and land use characteristics of risk-prone regions to carry out comprehensive studies on the impact of LUCC on landslide susceptibility.

-

(3)

When using LUCC for landslide susceptibility mapping, the temporal effects should be considered. For instance, forest cutting is often thought to increase the frequency of shallow landslides, but this impact is relative over time. The peak of landslide risk caused by deforestation typically occurs within 5 to 10 years (Sidle and Bogaard, 2016), after which it decreases due to weathering layer depletion and vegetation recovery. Its long-term effects may surpass the expected LUCC or climate scenarios (Depicker et al., 2021a; Parker et al., 2016). Márquez et al. (2019) suggest that a minimum period of 5 years should be used to define categories when detecting land use changes. Many studies have used longer intervals (Cerovski-Darriau and Roering, 2016; Mugagga et al., 2012; Pisano et al., 2017; Vuillez et al., 2018), which may reduce the accuracy of smaller LUCC categories. Therefore, we need to strengthen the monitoring of long-term dynamic LUCC changes and data integration (Digra et al., 2022; van Westen et al., 2008), particularly in the fusion of high temporal-spatial resolution remote sensing and ground observation data. Additionally, more attention should be given to feedback processes at different time scales, such as how land use planning can reduce long-term landslide risk by mitigating climate change effects.

-

(4)

Existing studies on landslide susceptibility generally overlook the interactions between different land use types and their coupling with natural factors such as topography, geology, and climate. This limitation may significantly reduce the accuracy of landslide susceptibility mapping at the local level. Therefore, we suggest correlating changes in susceptibility patterns over specific time scales on LUCC cells with land-use transition matrices to assess the specific impacts of different transition paths on landslide susceptibility. Meanwhile, through field surveys and laboratory simulation experiments, we aim to explore the interaction mechanisms between LUCC and natural factors (e.g., rainfall intensity, geological characteristics) under the background of climate change (e.g., the amplifying effect of increased extreme rainfall frequency and altered precipitation patterns on LUCC-induced disaster effects). By integrating analyses of typical IPCC climate scenarios and incorporating the coupled responses of LUCC and climatic factors into multi-factor coupling models, we seek to reveal the impact mechanisms of LUCC on the dynamic characteristics of landslide susceptibility under complex geomorphological and diverse climatic conditions (especially under climate change scenarios), and construct a cross-scale predictive framework for “climate change-LUCC-landslide risk”.

Land management strategies for landslide risk reduction

To effectively reduce landslide risk, it is essential to establish a sustainable land management framework (Fig. 8).

This diagram employs a color-coded system for four core strategies: purple for Conservation and Protection, orange for Improvement and Restoration, blue for Strengthening Management, and green for Monitoring and Early Warning; key influencing factors are highlighted in yellow boxes; the outermost ring integrates international disaster prevention strategies, land use planning metrics, and sustainable development initiatives.

Natural resilience enhancement: protection and compensation mechanisms for high-value ecosystems

Protecting lands with high ecological value, such as pristine forests, wetlands, and grasslands, is a key strategy for reducing landslide risk and enhancing ecosystem services (Wang et al., 2023). These areas play a crucial role in soil and water conservation, as well as slope stability. By restoring vegetation and stabilizing soil structure, their natural buffering capacity can be improved, thus reducing the risk of landslides and other natural disasters (Paudel et al., 2024). Based on this, governments should develop relevant policies and laws to promote ecological compensation mechanisms, encouraging local governments and communities to actively engage in the protection and restoration of vulnerable ecological zones (Liu et al., 2023). Ecological compensation funds can be raised through diversified financing channels such as green bonds and ecological protection funds, attracting investment from the private sector and international organizations. The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Goal 15, explicitly calls for the “protection, restoration, and sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems”, offering a strong policy framework and international support (UN, 2015). China’s projects, such as the Saihanba Desertification Control and North China Ecological Water Supplementation, provide practical experience for this strategy and have demonstrated the dual benefits of ecological protection and disaster risk reduction (Fu et al., 2023).

Risk source control: ecological restoration and engineering intervention of degraded land

For damaged land types such as mining areas, abandoned farmlands, and degraded grasslands, a series of improvement and restoration strategies should be implemented. First, soil and water conservation measures, such as terracing and vegetation restoration, should be applied in degraded farmlands to reduce soil erosion and enhance soil stability. For mining areas and post-landslide regions, specific land restoration plans should be formulated, including slope reshaping and surface vegetation recovery, to reduce landslide risks at the source (Chatterjee et al., 2024). Similar to the Program of Central America Dry Corridor, restoring ecosystems and integrating traditional farming practices to enhance the productivity of natural landscapes can provide biodiversity and soil and water conservation benefits for these regions (Gotlieb et al., 2019). To achieve these goals, restoration projects should be piloted in areas with frequent economic activities or dense populations, in line with national disaster risk reduction strategies, to ensure the effective implementation of restoration measures. Additionally, international funding support, such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and other international environmental protection funds, can provide the necessary financial backing for restoration projects, ensuring smooth execution and long-term results (GEF, 1990).

Optimization of human-land relationship: adaptive management of land use in sensitive areas

To effectively optimize land use and reduce the exacerbation of landslide risks due to human activities, it is necessary to focus on land types such as cultivated land, artificial forests, and agroforestry land, and adopt corresponding management strategies. First, precision agriculture technologies should be promoted in cultivated land to minimize soil disturbance and protect surface structure (Oliver et al., 2013). In artificial forest areas, mixed-species planting should be encouraged to avoid the vulnerability of monocultures under extreme climate conditions (Seddon et al., 2021). Furthermore, for low-density development areas, zoning planning should be implemented, with reasonable restrictions on construction density in steep slope regions to reduce the contribution of improper construction to landslide risks. Similar to land consolidation measures in Bavaria, Germany, land merging and rehabilitation can improve agricultural production conditions, enhance rural landscape layouts, reduce soil erosion risks, and strengthen soil stability (Jiang et al., 2022). This experience can be applied to other regions, especially in countries with well-developed agriculture and forestry. These strategies should be integrated with national disaster risk reduction policies to ensure the long-term sustainability of land management.

Dynamic response to risks: intelligent monitoring and early warning, and community co-governance system

To address the landslide threats in high-risk and rapidly developing areas, particularly in densely populated regions with high economic value, monitoring and early warning strategies should be implemented. A high-density real-time monitoring network should be established in high-risk areas, focusing on rainfall, soil moisture, and surface displacement, to promptly identify potential landslide risks (Pecoraro et al., 2019). For densely built-up areas and critical transportation corridors, a landslide risk early warning system should be developed and integrated with community response mechanisms to ensure a rapid emergency response in the event of a disaster (Fathani et al., 2016). Given that land management in many high-risk areas is difficult to improve in the short term, early warning systems become a critical tool. The United Nations has set a goal to ensure that everyone globally will have access to early warning protection by 2027, guiding countries to establish and enhance landslide early warning systems (UNDRR, 2022). Furthermore, these monitoring and early warning systems should be aligned with national disaster risk reduction technical standards, promoting technical cooperation and information sharing among countries in emergency management, particularly strengthening technical support for developing and high-risk countries to ensure timely prediction and response to landslide risks worldwide.

Conclusion

This comprehensive review of 102 research papers explores the research landscape of LUCC-landslide studies and the impacts of LUCC on landslide susceptibility. Although we focused on mainstream and influential databases rather than all available ones during the literature search, which may have overlooked some research contributions, the key insights herein are still expected to provide a theoretical basis for disaster management, social security, ecosystem conservation, and sustainable development.

Our analysis reveals that LUCC-landslide research has evolved through three stages: the early stage, the development stage, and the explosion stage. The studies are mainly grouped into three clusters: susceptibility modeling, landslide changes under climate change, and small-scale landslide triggering mechanisms. Data-driven methods dominate the field, while integrating physical mechanisms into data models to improve prediction accuracy and interpretability is a key focus for future research. The main factors contributing to increased landslide susceptibility are deforestation and urban expansion, while the impact of changes in cultivated land, shrubland, and grassland depends on specific circumstances.

However, several limitations in existing studies need to be addressed. First, there is an overemphasis on model optimization and comparison, with a lack of in-depth discussion on the nature, interpretation, and dynamic characteristics of the relationship between LUCC and landslide susceptibility. Second, there is insufficient coverage of global landslide risk areas, particularly in rapidly changing regions and areas with frequent landslides. Third, the time effects of LUCC on landslides have not been adequately studied, limiting our ability to comprehensively predict and mitigate risks. Finally, studies often overlook the interactions between different land use types and their coupling with natural factors, which affects the accuracy of landslide susceptibility assessments. To address these limitations, we offer several recommendations. Additionally, we propose a sustainable land management framework that considers the disaster effects of land use types and socioeconomic conditions. This framework aims to provide theoretical support for land use planning policies, helping managers mitigate landslide risks related to LUCC.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Agboola G, Beni LH, Elbayoumi T, Thompson G (2024) Optimizing landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning and geospatial techniques. Ecol Inform 81:102583

Al-Najjar HA, Pradhan B (2021) Spatial landslide susceptibility assessment using machine learning techniques assisted by additional data created with generative adversarial networks. Geosci Front 12:625–637

Aslam B, Maqsoom A, Saeed AM, Khalil U (2023) Impact of LULC on debris flow using linear aggression model from Gilgit to Khunjerab with emphasis on urban sprawl. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30:107068–107083

Bogaard TA, Greco R (2016) Landslide hydrology: from hydrology to pore pressure. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Water 3:439–459

Bozzolan E, Holcombe EA, Pianosi F, Marchesini I, Alvioli M, Wagener T (2023) A mechanistic approach to include climate change and unplanned urban sprawl in landslide susceptibility maps. Sci total Environ 858:159412

Caviezel C, Hunziker M, Schaffner M, Kuhn NJ (2014) Soil–vegetation interaction on slopes with bush encroachment in the central Alps–adapting slope stability measurements to shifting process domains. Earth Surf Process Landf 39:509–521

Cerovski-Darriau C, Roering JJ (2016) Influence of anthropogenic land-use change on hillslope erosion in the Waipaoa River Basin, New Zealand. Earth Surf Process Landf 41:2167–2176

Chatterjee A, Mitra I, De M (2024) From vulnerability to resilience: the role of community participation in landslide risk mitigation in the Himalayan region, Landslides in the Himalayan region: risk assessment and mitigation strategy for sustainable management. Springer, pp 465–497

Chuang YC, Shiu YS (2018) Relationship between landslides and mountain development-Integrating geospatial statistics and a new long-term database. Sci Total Environ 622:1265–1276

Ciurleo M, Cascini L, Calvello M (2017) A comparison of statistical and deterministic methods for shallow landslide susceptibility zoning in clayey soils. Eng Geol 223:71–81

Dandridge C, Stanley T, Kirschbaum D, Amatya P, Lakshmi V (2023) The influence of land use and land cover change on landslide susceptibility in the Lower Mekong River Basin. Nat Hazards 115:1499–1523

Depicker A, Govers G, Jacobs L, Campforts B, Uwihirwe J, Dewitte O (2021a) Interactions between deforestation, landscape rejuvenation, and shallow landslides in the North Tanganyika–Kivu rift region, Africa. Earth Surf Dyn 9:445–462

Depicker A, Jacobs L, Mboga N, Smets B, Van Rompaey A, Lennert M, Wolff E, Kervyn F, Michellier C, Dewitte O, Govers G (2021b) Historical dynamics of landslide risk from population and forest-cover changes in the Kivu Rift. Nat Sustain 4:965–974

Digra M, Dhir R, Sharma N (2022) Land use land cover classification of remote sensing images based on the deep learning approaches: a statistical analysis and review. Arab J Geosci 15:1003

Dubovik O, Schuster GL, Xu F, Hu Y, Bösch H, Landgraf J, Li Z (2021) Grand challenges in satellite remote sensing. Frontiers Media SA, pp. 619818

Ehigiator O, Anyata B (2011) Effects of land clearing techniques and tillage systems on runoff and soil erosion in a tropical rain forest in Nigeria. J Environ Manag 92:2875–2880

Fathani TF, Karnawati D, Wilopo W (2016) An integrated methodology to develop a standard for landslide early warning systems. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 16:2123–2135

Froude MJ, Petley DN (2018) Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 18:2161–2181

Fu B, Liu Y, Meadows ME (2023) Ecological restoration for sustainable development in China. Natl Sci Rev 10:nwad033

Gariano SL, Guzzetti F (2016) Landslides in a changing climate. Earth Sci Rev 162:227–252

Gariano SL, Petrucci O, Rianna G, Santini M, Guzzetti F (2018) Impacts of past and future land changes on landslides in southern Italy. Reg Environ change 18:437–449

GEF (1990) The Global Environment Facility. https://www.thegef.org/who-we-are

Gill JC, Malamud BD (2017) Anthropogenic processes, natural hazards, and interactions in a multi-hazard framework. Earth-Sci Rev 166:246–269

Glade T (2003) Landslide occurrence as a response to land use change: a review of evidence from New Zealand. Catena 51:297–314

Gotlieb Y, Pérez-Briceño PM, Hidalgo H, Alfaro E (2019) The Central American Dry Corridor: a consensus statement and its background. Rev Yu’am 3:42–51

Guo Z, Ferrer JV, Hürlimann M, Medina V, Puig-Polo C, Yin K, Huang D (2023) Shallow landslide susceptibility assessment under future climate and land cover changes: a case study from southwest China. Geosci Front 14:101542

Hasnawir, Kubota T, Sanchez-Castillo L, Soma AS (2017) The influence of land use and rainfall on shallow landslides in tanralili sub-watershed, Indonesia. J Fac Agric Kyushu Univ 62:171–176

Ij H (2018) Statistics versus machine learning. Nat Methods 15:233

Jiang Y, Tang Y-T, Long H, Deng W (2022) Land consolidation: a comparative research between Europe and China. Land Use Policy 112:105790

Jurchescu M, Kucsicsa G, Micu M, Bălteanu D, Sima M, Popovici E-A (2023) Implications of future land-use/cover pattern change on landslide susceptibility at a national level: a scenario-based analysis in Romania. Catena 231:107330

Kirschbaum D, Stanley T, Zhou Y (2015) Spatial and temporal analysis of a global landslide catalog. Geomorphology 249:4–15

Knevels R, Brenning A, Gingrich S, Heiss G, Lechner T, Leopold P, Plutzar C, Proske H, Petschko H (2021) Towards the use of land use legacies in landslide modeling: current challenges and future perspectives in an Austrian case study. Land 10(9):954

Lann T, Bao H, Lan H, Zheng H, Yan C (2024) Hydro-mechanical effects of vegetation on slope stability: a review. Science of the Total Environment, pp 171691

Lehmann P, von Ruette J, Or D (2019) Deforestation effects on rainfall‐induced shallow landslides: Remote sensing and physically‐based modelling. Water Resour Res 55:9962–9976

Leroi E, Bonnard C, Fell R, McInnes R (2005) Risk assessment and management, Landslide risk management. CRC Press, pp 169–208

Li H, Liu Z, Lin X, Qin M, Ye S, Gao P (2024) A novel spatiotemporal urban land change simulation model: Coupling transformer encoder, convolutional neural network, and cellular automata. J Geogr Sci 34:2263–2287

Lian B, Wang X, Zhan H, Wang J, Peng J, Gu T, Zhu R (2022) Creep mechanical and microstructural insights into the failure mechanism of loess landslides induced by dry-wet cycles in the Heifangtai platform, China. Eng Geol 300:106589

Liu S, Wang L, Zhang W, Sun W, Wang Y, Liu J (2024a) Physics-informed optimization for a data-driven approach in landslide susceptibility evaluation. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng 16:3192–3205

Liu T, Yu L, Chen X, Wu H, Lin H, Li C, Hou J (2023) Environmental laws and ecological restoration projects enhancing ecosystem services in China: a meta-analysis. J Environ Manag 327:116810

Liu Y, Zhong Y, Shi S, Zhang L (2024b) Scale-aware deep reinforcement learning for high resolution remote sensing imagery classification. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens 209:296–311

Löbmann MT, Geitner C, Wellstein C, Zerbe S (2020) The influence of herbaceous vegetation on slope stability–a review. Earth Sci Rev 209:103328

Manchado AM-T, Ballesteros-Cánovas JA, Allen S, Stoffel M (2022) Deforestation controls landslide susceptibility in Far-Western Nepal. Catena 219:106627

Márquez AM, Guevara E, Rey D (2019) Hybrid model for forecasting of changes in land use and land cover using satellite techniques. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Observ Remote Sens 12:252–273

Merghadi A, Yunus AP, Dou J, Whiteley J, ThaiPham B, Bui DT, Avtar R, Abderrahmane B (2020) Machine learning methods for landslide susceptibility studies: a comparative overview of algorithm performance. Earth Sci Rev 207:103225

Michetti M, Zampieri M (2014) Climate–human–land interactions: a review of major modelling approaches. Land 3:793–833

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8:336–341

Mugagga F, Kakembo V, Buyinza M (2012) Land use changes on the slopes of Mount Elgon and the implications for the occurrence of landslides. Catena 90:39–46

Myint Thein K, Nagai M, Nakamura T, Phienwej N, Pal I (2023) Assessment of the Impacts of Urbanization on Landslide Susceptibility in Hakha City, a Mountainous Region of Western Myanmar. Land 12:1036

Nkonya E, Mirzabaev A, Von Braun J (2016) Economics of land degradation and improvement–a global assessment for sustainable development. Springer Nature

Oliver MA, Bishop TF, Marchant BP (2013) Precision agriculture for sustainability and environmental protection. Routledge, Abingdon, UK

Ozturk U, Bozzolan E, Holcombe EA, Shukla R, Pianosi F, Wagener T (2022) How climate change and unplanned urban sprawl bring more landslides. Nature 608:262–265

Pacheco Quevedo R, Velastegui-Montoya A, Montalván-Burbano N, Morante-Carballo F, Korup O, Daleles Rennó C (2023) Land use and land cover as a conditioning factor in landslide susceptibility: a literature review. Landslides 20:967–982

Parker RN, Hales TC, Mudd SM, Grieve SW, Constantine JA (2016) Colluvium supply in humid regions limits the frequency of storm-triggered landslides. Sci Rep. 6:34438

Parra E, Mohr CH, Korup O (2021) Predicting Patagonian landslides: roles of forest cover and wind speed. Geophys Res Lett 48:e2021GL095224

Paudel PK, Dhakal S, Sharma S (2024) Pathways of ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction: a global review of empirical evidence. Science of the Total Environment, pp 172721

Pawlik Ł (2013) The role of trees in the geomorphic system of forested hillslopes—a review. Earth Sci Rev 126:250–265

Pecoraro G, Calvello M, Piciullo L (2019) Monitoring strategies for local landslide early warning systems. Landslides 16:213–231

Pham QB, Pal SC, Chakrabortty R, Saha A, Janizadeh S, Ahmadi K, Khedher KM, Anh DT, Tiefenbacher JP, Bannari A (2022) Predicting landslide susceptibility based on decision tree machine learning models under climate and land use changes. Geocarto Int 37:7881–7907

Pisano L, Zumpano V, Malek Ž, Rosskopf CM, Parise M (2017) Variations in the susceptibility to landslides, as a consequence of land cover changes: a look to the past, and another towards the future. Sci Total Environ 601:1147–1159

Pradhan B, Dikshit A, Lee S, Kim H (2023) An explainable AI (XAI) model for landslide susceptibility modeling. Appl Soft Comput 142:110324

Promper C, Gassner C, Glade T (2015) Spatiotemporal patterns of landslide exposure - a step within future landslide risk analysis on a regional scale applied in Waidhofen/Ybbs, Austria. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 12:25–33

Rashid B, Iqbal J, Su L-j (2020) Landslide susceptibility analysis of Karakoram highway using analytical hierarchy process and Scoops 3D. J Mt Sci 17:1596–1612

Ren Y, Lü Y, Comber A, Fu B, Harris P, Wu L (2019) Spatially explicit simulation of land use/land cover changes: Current coverage and future prospects. Earth Sci Rev 190:398–415

Rohan T, Shelef E, Mirus B, Coleman T (2023) Prolonged influence of urbanization on landslide susceptibility. Landslides 20:1433–1447

Roy J, Saha S (2022) Ensemble hybrid machine learning methods for gully erosion susceptibility mapping: K-fold cross validation approach. Artif Intell Geosci 3:28–45

Sangeeta, Singh S (2023) Influence of anthropogenic activities on landslide susceptibility: a case study in Solan district, Himachal Pradesh, India. J Mt Sci 20:429–447

Seddon N, Smith A, Smith P, Key I, Chausson A, Girardin C, House J, Srivastava S, Turner B (2021) Getting the message right on nature‐based solutions to climate change. Glob Change Biol 27:1518–1546

Sidle RC, Bogaard TA (2016) Dynamic earth system and ecological controls of rainfall-initiated landslides. Earth Sci Rev 159:275–291

Sur U, Singh P, Rai PK, Thakur JK (2021) Landslide probability mapping by considering fuzzy numerical risk factor (FNRF) and landscape change for road corridor of Uttarakhand, India. Environ Dev Sustain 23:13526–13554

Tehrani FS, Calvello M, Liu Z, Zhang L, Lacasse S (2022) Machine learning and landslide studies: recent advances and applications. Nat Hazards 114:1197–1245

Tyagi A, Tiwari RK, James N (2023) Prediction of the future landslide susceptibility scenario based on LULC and climate projections. Landslides 20:1837–1852

Ul Din S, Mak HWL (2021) Retrieval of land-use/land cover change (LUCC) maps and urban expansion dynamics of Hyderabad, Pakistan via Landsat datasets and support vector machine framework. Remote Sens 13:3337

UN (2015) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

UNDRR (2022) Early warnings for all. https://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework/sendai-framework-action/early-warnings-for-all

Van Beek L, Van Asch TW (2004) Regional assessment of the effects of land-use change on landslide hazard by means of physically based modelling. Nat Hazards 31:289–304

van Westen CJ, Castellanos E, Kuriakose SL (2008) Spatial data for landslide susceptibility, hazard, and vulnerability assessment: an overview. Eng Geol 102:112–131

Verburg PH, Crossman N, Ellis EC, Heinimann A, Hostert P, Mertz O, Nagendra H, Sikor T, Erb K-H, Golubiewski N (2015) Land system science and sustainable development of the earth system: a global land project perspective. Anthropocene 12:29–41

Vuillez C, Tonini M, Sudmeier-Rieux K, Devkota S, Derron M-H, Jaboyedoff M (2018) Land use changes, landslides and roads in the Phewa Watershed, Western Nepal from 1979 to 2016. Appl Geogr 94:30–40

Wang K, Zheng H, Zhao X, Sang Z, Yan W, Cai Z, Xu Y, Zhang F (2023) Landscape ecological risk assessment of the Hailar River basin based on ecosystem services in China. Ecol Indic 147:109795

Wasowski J, Lamanna C, Casarano D (2010) Influence of land-use change and precipitation patterns on landslide activity in the Daunia Apennines, Italy. Q J Eng Geol Hydrogeol 43:387–401

Xin Z, Xiaoyu Z, Chenyi Z, Zhile S, Lijun J, Zelin W, Zheng F, Jiayang Y, Xin Y, Wenwu Z (2023) The relationship between geological disasters with land use change, meteorological and hydrological factors: a case study of Neijiang City in Sichuan Province. Ecol Indic 154:110840

Xiong H, Ma C, Li M, Tan J, Wang Y (2023) Landslide susceptibility prediction considering land use change and human activity: a case study under rapid urban expansion and afforestation in China. Sci Total Environ 866:161430

Yang X, Jia C, Sun H, Yang T, Yao Y (2024) Integrating multi-source data to assess land subsidence sensitivity and management policies. Environ Impact Assess Rev 104:107315

Ye S, Wang J, Liu Q, Tarhan LG (2024) International collaboration in geoscience lags behind other scientific disciplines. Nat Geosci 17:1068–1071

Yong C, Jinlong D, Fei G, Bin T, Tao Z, Hao F, Li W, Qinghua Z (2022) Review of landslide susceptibility assessment based on knowledge mapping. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 36:2399–2417

Youssef K, Shao K, Moon S, Bouchard L-S (2023) Landslide susceptibility modeling by interpretable neural network. Commun Earth Environ 4:162

Zeng T, Guo Z, Wang L, Jin B, Wu F, Guo R (2023) Tempo-spatial landslide susceptibility assessment from the perspective of human engineering activity. Remote Sens 15:4111

Zhang X, Zeng XY, Luo H, Zhou CY, Shu ZL, Jiang LJ, Wang ZL, Fei Z, Yu JY, Yang X, Zhong WW (2023a) The relationship between geological disasters with land use change, meteorological and hydrological factors: a case study of Neijiang City in Sichuan Province. Ecol Indic 154:13

Zhang Z, Zeng R, Meng X, Zhao S, Wang S, Ma J, Wang H (2023b) Effects of changes in soil properties caused by progressive infiltration of rainwater on rainfall-induced landslides. Catena 233:107475

Zhao B, Yuan L, Geng XY, Su LJ, Qian JP, Wu HH, Liu M, Li J (2022) Deformation characteristics of a large landslide reactivated by human activity in Wanyuan city, Sichuan Province, China. Landslides 19:1131–1141

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 24&ZD164).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, HZ and XZ; methodology, HZ and XZ; software, HZ; validation, ML; resources, XZ; data curation, HZ; writing—original draft preparation, HZ and XZ; writing—review and editing, XZ, QX, XF, ML, and XJ; visualization, ZF; supervision, XZ; project administration, XZ All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, H., Zhu, X., Xu, Q. et al. From hazard mapping to risk governance: 20-year trajectory of land use/cover change impacts on landslide susceptibility via multi-modal scientometrics. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1609 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05831-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05831-7