Abstract

Against the backdrop of climate change, resource competition, and increasing socio-economic uncertainty, the resilience of the water-energy-food nexus (WEFN) has emerged as a critical issue for ensuring China’s transition toward steady development. As a representative region of China’s water-energy-food nexus (WEFN), the Yellow River Basin exhibits significant spatial disparities. Developing a theoretical framework that is better adapted to regional characteristics and examining the historical evolution and future trends of WEFN resilience (WEFNR) spatial linkages are crucial for enhancing overall coordination across the basin. The study finds that: (1) The WEFNR in the Yellow River Basin comprises four dimensions: Cross-Scale Resource Coordination, Systemic Adaptive Dynamics, Institutional Synergy and Governance Depth, Equitable and Functional Eco-Infrastructure. (2) From 2013 to 2022, the WEFNR in the Yellow River Basin exhibited increased volatility, with internal linkages and external interactions becoming more coordinated, and overall risk resistance improving; the spatial pattern featured an “upstream bulge–midstream depression–downstream uplift,” with high resilience values concentrated along the main river course and in core cities. (3) The spatial association network revealed a distinct “core-periphery” structure, with upstream and downstream cities occupying central network positions. Resource-intensive and economically developed cities demonstrated significant spillover effects, yet cross-cluster coordination remained weak and structural barriers persisted. Rising temperatures and industrial structure optimization inhibited network formation, while larger government size and greater innovation capacity promoted stronger inter-city linkages. (4) The basin-wide WEFNR exhibited both absolute and conditional β-convergence; however, innovation capacity suppressed convergence, and government scale also had a dampening effect under networked conditions. Sub-basin analysis revealed significant inhibitory effects of innovation capacity in the midstream and downstream regions, with weak divergence trends observed primarily in central and lower-middle cities, while central cities displayed a positive development trajectory. Based on these findings, this study proposes a coordinated optimization strategy for enhancing WEFNR in the Yellow River Basin, offering new theoretical and practical insights for resilience research in similar global basins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water, energy, and food are critical pillars for achieving sustainable development, directly linked to food security (SDG 2), water resource management (SDG 6), and accessible energy (SDG 7) (Mohtar, 2016), while also closely tied to promoting sustainable consumption and production patterns (SDG 12) and addressing climate change (SDG 13) (Niet et al., 2021). However, under the influence of climate change, population pressure, and accelerating urbanization, the supply-demand conflicts of WEF resources have intensified globally, making the security and sustainability of WEFNR a critical issue for China’s socioeconomic transition toward a new steady state (Leck et al., 2015). The YRB, as a significant economic belt in China, serves not only as a crucial agricultural and pastoral production base but also as an indispensable energy hub. The basin contributes one-quarter of China’s GDP, utilizing one-fifth of the nation’s water resources to support 63% of the China’s primary energy production while ensuring 35% of China’s grain and 32% of its meat production (Zhang et al., 2024). However, significant spatial imbalances in WEFNR arise due to differing ecological environments, economic foundations, resource endowments, and industrial compositions across the YRB, posing severe challenges to overall WEF coordination. Spatial linkages, as a prerequisite for spillovers and convergence, serve as a crucial mechanism for narrowing the WEFNR gaps within the YRB. In fact, since the Chinese government introduced the concept of high-quality development for the YRB, WEFNR, driven by the integrated coordination of WEF resources and supported by interactive and reciprocal WEF ecological infrastructure, has transcended simple geographical “proximity” to exhibit complex, multi-threaded, and cross-regional spatial linkage network characteristics. Therefore, evaluating the WEFN from a resilience perspective and conducting in-depth research on the theoretical structure, spatial association network characteristics, functional pathways, and spatial convergence of WEFNR in the Yellow River Basin can effectively capture the system’s comprehensive capacity for resistance, recovery, adaptation, and transformative upgrading, as well as its dynamic evolution. At the same time, it facilitates the identification of the linkage effects of WEFNR under varying influences such as climate, industry, and technology, which is of great significance for deepening the understanding of inter-city WEFNR interactions and long-term trends, establishing mechanisms for cross-regional coordinated enhancement, and fostering a synergistically integrated WEFNR system.

Research on WEFR has transitioned from a single-dimensional approach to a WEF system perspective, currently focusing on three main areas: conceptual definitions, structural characteristics, and specific perspective measurements, and the interactions and impact mechanisms between WEFNR and the socio-ecological environment. Regarding conceptual definitions, existing studies mainly start with the concept of resilience itself, integrating the resilience framework with WEFN characteristics to construct the WEFNR framework. Current understanding of the resilience concept can be divided into three stages: the first stage, engineering resilience, refers to the system’s ability to return to a stable or equilibrium state (Holling, 1973); the second stage, ecological resilience, denotes the maximum level of disturbance a system can absorb before transitioning to another equilibrium state (Holling, 1996); and the third stage, systemic resilience, emphasizes the system’s capacity for defense, adaptation, and transformation under multi-dimensional thinking when disturbances occur (Keck and Sakdapolrak, 2013). WEFNR is often defined as the water, energy, and food system’s capacities for defense, adaptation, and transformation in the face of disturbances. The theoretical construction of WEFNR is typically based on a literature review of individual WEF dimensions, guided by resilience theory to identify the connections between various concepts (Zhang et al., 2024). Concerning structural characteristics and specific perspective measurements, existing research generally considers WEFN as a nonlinear, open, complex system with composite evolutionary traits (Zhang et al., 2020). As various issues emerge within the WEFN system, current studies comprehensively evaluate WEFN from perspectives such as system stress (Bhave et al., 2022), efficiency (Wang et al., 2018), security (Ji et al., 2023), and coupling coordination characteristics (Wang et al., 2022), using the constructed WEFNR theory to establish evaluation index systems and discuss the complex relationships between these characteristics and WEFNR. Key methodologies include the TOPSIS model (Gu et al., 2022), the coupling coordination model (Qi et al., 2022), the data envelopment analysis (Huang et al., 2023), and input-output models (Tabatabaie and Murthy, 2021). The interdisciplinary integration of research methods is prominent, with study scales spanning macro, meso, and increasingly micro levels, while major regions have become key focal points of recent research. In terms of the interactions and impact mechanisms between WEFNR and the socio-ecological environment, interdisciplinary integration among fields such as ecology, geography, and management has enriched research content and perspectives. Topics include urban resilience from the perspective of WEF coordination (Zhu et al., 2022) and farmers’ livelihood issues (Karamian et al., 2021) as well as the coupling relationships between WEFN and ecosystem services (Bell et al., 2016). Multi-scale geographically weighted regression models and geographical detector models are widely applied to reveal the driving mechanisms of spatiotemporal differentiation.

However, existing WEFNR frameworks are mostly derived from top-down literature reviews, which often neglect the principle of contextual adaptation, resulting in limited practicality and adaptability. In contrast, constructivist grounded theory constructs theoretically robust and regionally adaptive frameworks and indicator systems through iterative coding and induction based on empirical data, making it more suitable for the localized construction of resilience frameworks in complex systems. Meanwhile, research on the spatial network characteristics and convergence of WEFNR remains unexplored. The structural features and causes of spatial association networks lack clear understanding, and spatial convergence studies consider only adjacency matrices, overlooking the interactive effects of the actual complex network forms between regions. Therefore, in constructing the WEFNR framework, it is essential to simultaneously focus on the internal dimensions and external linkages of WEFN, employing the dynamic entropy-weighted TOPSIS (DEW-TOPSIS) for WEFNR evaluation. In establishing relational connections, the modified gravity model (MGM) avoids the traditional gravity model’s neglect of economic linkages and the VAR model’s sensitivity to lag orders, providing better identification of spatial relationships (Fan et al., 2018). Social network analysis (SNA) overcome the limitations of “attribute data” analysis and effectively analyze the network characteristics of “relational data.” (Freeman, 2004) On this basis, introducing spatial convergence models (SCM) that incorporate spatial relationships (Cui et al., 2021) and the Hurst index (HI) (Funahashi and Kijima, 2017), which describes the trend changes of long-term variables, can comprehensively reveal the complex relationships of WEFNR between the YRB and its cities.

In summary, this study integrates these methods into a unified analytical framework, which can be divided into two aspects: historical characteristics and future changes. The WEFNR theory is constructed based on constructivist grounded theory, and the historical characteristics are evaluated using a dynamic entropy-weighted TOPSIS method for the Yellow River Basin during 2013–2022. A MGM is applied to identify spatial linkages of WEFNR among cities, which then serve as the basis for conducting SNA. Based on the historical network matrix, the spatial β-convergence model is introduced to estimate the convergence trends across the entire basin as well as for the upper, middle, and lower reaches. The HI is applied to demonstrate the future direction and magnitude of changes in cities. Optimization strategies for the coordination of WEFNR in the YRB are proposed based on historical characteristics and future changes. Figure 1 illustrates the research framework. The innovations of this study include: (1) Grounded in constructivist grounded theory and in comparison with the core concepts of evolutionary resilience, the development characteristics of resilience and the unique internal-external linkages of the WEF system are integrated into the theoretical construction of WEFNR, addressing the lack of attention to the complex and integrated nature of WEFNR in existing research and providing a new analytical perspective for the evaluation of WEFNR. (2) Introducing SNA into the study of spatial association characteristics, evolutionary processes, and driving mechanisms of WEFNR in the YRB. This facilitates the assessment of spatial effects, intrinsic association structures, and formation mechanisms of WEFNR among cities in the basin. Based on SNA, the study further discusses the convergence trends and future changes of WEFNR in the YRB. (3) Integrating “historical characteristics and future changes,” the study uncovers the black box of attribute, relational, and future characteristics of WEFNR in the YRB. This provides theoretical support for the overall coordination and optimization of WEFNR in the YRB, addressing gaps in existing research and a new avenues for further research.

Materials and methods

Research areas

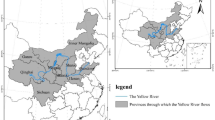

This study focuses on 60 prefecture-level cities, dividing the upper, middle, and lower reaches of the YRB based on the boundaries of Hekou Town in Inner Mongolia and Taohuayu in Zhengzhou, as shown in Fig. 2. Following official documents such as the Outline of Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the YRB issued by the Chinese government, the study considers the interconnectedness of basin development and the integrity of the ecosystem. Ideally, the study area would include 71 prefecture-level cities in the core areas of the mainstem and major tributaries of the YRB. However, due to incomplete data or unavailability of publicly accessible data, cities such as Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture, Haidong City, Haixi Mongolian and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Golog Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, and Sanmenxia City were excluded from the study. The retained 60 cities are representative, covering the main areas of the basin and ensuring data consistency, so the exclusion of regions with missing data does not significantly impact the study’s accuracy.

Data sources

-

(1)

Textual data

The textual data used in this study originate from two main sources: policy and planning documents, and transcriptions of recorded discussions from selected provinces. The former was used for initial coding, while the latter served as a supplementary investigation during theory construction, with portions utilized for theoretical saturation testing. The selected policy and planning documents include the Outline of the Comprehensive Plan for the Yellow River Basin (2012–2030), the Speech at the Symposium on Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the Yellow River Basin, and the Master Plan for Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the Yellow River Basin jointly issued by the Chinese central and nine provincial governments, totaling 319,556 Chinese characters. These documents are available on the official websites of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment’s Yellow River Basin Supervision Bureau and the provincial governments of the nine regions within the Yellow River Basin. To ensure representative coverage of the upper, middle, and lower reaches of the basin, four typical provinces—Gansu, Ningxia, Henan, and Shandong—were selected. The discussion participants included personnel from relevant administrative departments and domain experts, with a total interview duration of 12.4 h.

-

(2)

Statistical data

The statistical data used in this study are derived from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Rural Statistical Yearbook, China Water Resources Statistical Yearbook, China Environmental Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Urban Statistical Yearbook, Yellow River Yearbook (2014–2023), as well as relevant provincial and municipal statistical yearbooks, water resources bulletins, water development statistical reports, and bulletins on national economic and social development. Missing data were addressed using multiple imputation methods.

Methods

Constructivist grounded theory

Grounded theory is a classic qualitative research method that emphasizes the absence of preconceived hypotheses, relying on empirical data to construct theories within a specific substantive domain through systematic coding and inductive reasoning Glaser (1992). Constructivist grounded theory, proposed by Charmaz (2006), emphasizes that theoretical constructs are not objectively “discovered,” but are co-constructed by the researcher and the empirical data within specific social contexts. This approach challenges the traditional notion of the researcher as a neutral observer, instead recognizing the subjective involvement of the researcher in the interpretive process. Through contextualized understanding, comparative analysis, and interpretive coding of empirical materials, constructivist grounded theory gradually develops theoretically meaningful structures. Unlike traditional grounded theory, which seeks to extract categories from data as if they were inherent, the constructivist approach pays closer attention to the contextual embeddedness of concepts and the generative process of meaning, emphasizing the need to begin from specific problem settings and social situations.

Indicator processing and evaluation model

The evaluation indicators are derived from the constructed theoretical framework and are refined using the “Five deletions, one retention, and one addition” approach, which aims to simplify and optimize the indicator set of the evaluation model (An et al., 2024). This method improves model performance by eliminating redundant or irrelevant indicators, retaining core ones, and appropriately introducing new indicators where necessary. Specifically, the “Five deletions” refer to the removal of irrelevant indicators, multicollinear indicators, noisy indicators, redundant information indicators, and those that are difficult to quantify. The “One retention” involves preserving the most representative and explanatory core indicator. The “One addition” allows for the introduction of a new indicator that provides unique information and contributes to model optimization, should any gaps or shortcomings be identified during the integrative analysis.

A multi-criteria decision-making method combining dynamic entropy weight assignment and TOPSIS ranking is used to evaluate the WEFNR of prefecture-level cities in the YRB (Sun et al., 2022), with calculation formulas referencing Chen (2022). Dynamic entropy weights are employed to determine the weight of each indicator, and TOPSIS ranking is applied to analyze the proximity of solutions to the ideal solution, thereby identifying the optimal scheme.

The specific steps are as follows: (1) Apply the range method to perform dimensionless processing of indicator data. (2) Use the dynamic entropy method to calculate and determine the annual weights of each indicator. (3) Apply the TOPSIS method to calculate the comprehensive WEFNR scores of prefecture-level cities for different years.

MGM

A MGM is introduced to construct the spatial correlation matrix of the WEFNR network in the YRB, measuring the WEFNR connection intensity from 2013 to 2022, as represented by the following formula (Liu and Li, 2019):

where \(S\) represents the spatial correlation intensity of WEFNR between city \(i\) and city \(j\), \({E}_{i}\) and \({E}_{j}\) represent the WEFNR values of city \(i\) and city \(j\) respectively, Dij denotes the spherical distance between cities, \({g}_{i}\) and \({g}_{j}\) refer to the per capita GDP values of the two cities. To minimize the impact of price levels, per capita GDP data is deflated using 2004 as the base year. Furthermore, the average spatial correlation intensity of each row in the matrix is used as the threshold. If the WEFNR correlation intensity \(S\) between two cities exceeds the threshold, the value is set to 1, indicating a correlation; otherwise, the value is set to 0, indicating no correlation. This forms the binary matrix of WEFNR spatial correlation in the YRB.

SNA

SNA is an important method for studying the relationships among network members, effectively reflecting the association structure and attribute characteristics among members. This study uses UCINET software to measure the spatial network structural characteristics of WEFNR in the YRB, with specific calculation formulas based on Wang’s research (Wang et al., 2016).

-

(1)

Overall spatial network structure: Four indicators, namely network density, number of associations, network hierarchy, and network efficiency, are used to measure the overall network structure.

-

(2)

Individual spatial network structure: Three indicators—degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality—are used to measure individual network structure.

-

(3)

Block model: Interaction between roles is used to rearrange initial points in the matrix through cluster analysis. The spatial association network blocks are divided into four types: net spillover blocks, net beneficiary blocks, broker blocks, and bidirectional spillover blocks.

-

(4)

The Exponential Random Graph Model (ERGM): The ERGM is used to examine the endogenous structural effects, individual attribute effects, and external network effects in network formation, with the model as follows:

Where, \({P}_{1}={e}^{(-\beta {x}_{i}+\varepsilon )}/({1+e}^{(-\beta {x}_{i}+\varepsilon )})\) and \({P}_{0}=1/({1+e}^{(-\beta {x}_{i}+\varepsilon )})\) represent the probabilities of \({\boldsymbol{Y}}=1\) and \({\boldsymbol{Y}}=0\) under condition \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) respectively, \({\boldsymbol{Y}}\) represents the spatial correlation matrix of WEFNR, and \(P({\boldsymbol{Y}}|{\boldsymbol{X}})\) represents the probability of \({\boldsymbol{Y}}\) under condition \({\boldsymbol{X}}\). \(\beta\) is the coefficient to be estimated, and \({x}_{i}\) is the explanatory variable.

The explanatory variables include three categories: network configuration, node covariates, and edge covariates. The WEFNR spatial association network may form specific patterns through self-organizing effects. Therefore, considering the model’s degrees of freedom constraints, the number of edges (Edges) and mutuality (Mutual) of the network are included as endogenous structural variables. The number of edges is analogous to the intercept term in linear regression, while mutuality examines the tendency for bidirectional WEFNR spatial associations to form between cities. The individual attribute effect examines the impact of node attributes on the formation of associations within the network. Therefore, representative node covariates are selected from four dimensions: climate environment, socioeconomics, government governance, and technological innovation. Average temperature (AT) is directly related to water resource supply, agricultural production, and energy demand. Changes in temperature can affect river hydrological cycles, thereby influencing agricultural irrigation and water availability, with potential indirect impacts on electricity production (Romero-Lankao et al., 2018). Industrial structure (IS) is represented by the share of the tertiary sector’s value added in GDP, and IS directly affects resource consumption and the system’s capacity for resource allocation in the face of emergencies. Different IS layouts lead to variations in WEF demand, thus affecting the vulnerability and resilience of the WEFN’s resource supply chain (Hua et al., 2021). Government size (GFT) is represented by the ratio of fiscal expenditure to GDP, reflecting the administrative capacity of government and management factors in resource management, environmental protection, and regional coordination. Large-scale government support ensures adequate resource regulation capabilities and policy enforcement power, thereby enhancing regional flexibility and adaptability in disaster response and resource allocation (Ringler et al., 2013). Innovation capability (IC) is represented by the proportion of scientific and technological expenditures in the general fiscal budget; IC is not only a means to improve resource utilization efficiency but also a key capability in responding to climate change, natural resource pressures, and complex socio-economic demands. IC, through promoting technological advancements, management model transformations, and the development of renewable resources, enables the WEFNR to better adapt to shocks and self-repair. According to the First Law of Geography, WEFNR spatial associations that are geographically closer may be more tightly connected. Therefore, this study constructs a geographical adjacency matrix, where a value of 1 is assigned if cities are geographically adjacent, and 0 otherwise. By incorporating the inter-city geographical adjacency network (Geonet) into the model, the impact of geographical adjacency on the formation of the WEFNR spatial association network is examined.

Considering that the Markov Chain Monte Carlo maximum likelihood estimation provides more precise parameter estimates, this paper employs the Markov Chain Monte Carlo maximum likelihood estimation method to estimate the model’s parameters and uses pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation for robustness checks. Additionally, to avoid statistical inference errors caused by the complex dependency characteristics of the WEFNR spatial association network, this study includes the Geometrically Weighted Edge Shared Partner (GWESP) in the robustness checks.

β-SCM

Convergence models mainly include σ-convergence, β-convergence, and club convergence, among which β-convergence most effectively reflects the catching-up of lagging regions to leading regions (Young et al., 2008). Additionally, due to differences in factor endowments and spatial dependencies between regions, and since WEFNR convergence is a dynamic cumulative process with path dependence, a dynamic spatial econometric model should be constructed to test the spatial convergence of WEFNR. Moreover, the real interactive effects of the complex spatial network structure of WEFNR between cities are also considered. Common spatial econometric models include the Spatial Autoregressive Model (SAR), Spatial Error Model (SEM), and Spatial Durbin Model (SDM). The model construction follows Jiang’s research (Jiang et al., 2018), and the convergence speed ω (%) and half-life π (years) are calculated. For panel data selection, the LM test is generally used to check whether spatial autocorrelation exists in the data. If it does, at least one of the SAR or SEM models is valid. Then, the SDA model is established, and Wald and LR statistics are used to determine whether it can be simplified to SAR and SEM. The control variables include: AT, IS, GFT, and IC. Two forms of spatial weight matrices are constructed: one is a spatial binary matrix derived from the MGM as the network weight (Wn) to capture the network effect of WEFNR, and the other is an adjacency weight matrix (Wc) for comparison.

HI

The HI effectively describes the trend of a long-term time series variable, predicting whether the variable will follow a random walk or a biased random walk in the future. Its calculation is essentially based on the rescaled range analysis (R/S) method, and the Hurst indices for various cities are computed by referring to Wang’s study (Wang et al. (2023)). When 0 < H < 0.5, it indicates that the future trend is opposite to the current trend, meaning the development of urban resilience exhibits anti-persistence. When 0.5 < H < 1, it indicates that the future trend is consistent with the current trend, meaning the development of urban resilience exhibits persistence. The HI levels are further classified, as shown in Table 1.

Results

Analysis of the WEFNR framework and development of the indicator system

Based on the constructivist grounded theory process and guided by the principles of evolutionary resilience, this study conducts an in-depth analysis of the WEFNR framework and validates it through theoretical saturation testing. The resulting conceptualization of WEFNR is as follows: In response to external environmental changes and uncertain disturbances, the WEFN achieves disturbance absorption, supply stability, and functional recovery through cross-scale resource allocation and systemic coordination within the nexus. With the support of ecological infrastructure and governance systems, the WEFN enhances its capacity to restore damaged components and maintain overall system balance. Through continuous iteration and optimization, the WEFN develops a dynamic capability of self-adaptation, mutual integration, and resilience evolution. The relationships among the core categories of the WEFNR framework are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 shows that cross-scale resource coordination serves as the foundational dimension of the WEFN system, emphasizing the efficient flow and coordinated allocation of water, energy, and food resources across spatial scales—such as municipal, provincial, and basin levels. It enhances regional balance and systemic synergy, providing the material basis for coordinated adaptation and stable operation within the nexus. The realization of systemic adaptive dynamics is dependent on the degree of CSRC. This dimension focuses on the responsiveness, adjustment capacity, and recovery pathways of interconnected subsystems when confronted with shocks such as droughts, floods, or energy shortages. Institutional Synergy and Governance Depth provides institutional support for both CSRC and SAD. Through multi-level policy integration, intersectoral coordination, and adaptive governance feedback mechanisms, ISGD standardizes resource flow pathways while promoting public participation and information exchange within the institutional framework, thereby enhancing the system’s self-organizing capacity. The effective interaction of these three dimensions relies on the service foundation provided by Equitable and Functional Eco-Infrastructure. Ecological infrastructure not only constitutes the natural basis for resource circulation, but also plays a crucial role in mitigating systemic risks and regulating ecological processes. It ensures the sustainability of resource supply across units within the basin-scale WEFN system. Collectively, the four dimensions form an interactive framework of “foundational support–dynamic regulation–institutional backing–ecological carrying capacity,” constituting the core system for WEFNR.

The WEFN system is essentially nonlinear and open, characterized by complex structural evolution. Internally, subsystems coordinate and compete, balancing systemic performance while pursuing individual optimization. Externally, the WEFN interacts strongly with human activities and ecosystem services. These internal and external dynamics lead to the emergence of new order. To ensure both theoretical validity and data availability at the prefecture level, the evaluation indicators were refined using the “Five deletions, one retention, and one addition” method, resulting in the final comprehensive indicator system, as presented in Table 2 Internal linkages reflect the structural and dynamic relationships among water, energy, and food subsystems, encompassing interdependence, efficiency, and security. External interactions focus on the pressures, adaptability, and support provided by the broader social, ecological, and policy environment to the WEFN system.

Spatiotemporal differentiation characteristics of WEFNR in the YRB

As shown in Fig. 4a, the average WEFNR in the YRB fluctuated from 0.3303 in 2013 to 0.3330 in 2022, reflecting the continuous adaptation and optimization of WEFN in the basin under changing environmental conditions. The internal connections and external interactions have become more synergistic, enhancing the basin’s capacity to withstand internal and external potential threats. The WEFNR exhibits distinct phased characteristics over time: a gradual rise from 2013 to 2015 forming a peak, another peak emerging from a trough during 2016 to 2018, and a slow rise from a trough between 2019 and 2022. This trend may be related to the impacts of climate change and policy implementation. Regionally, the overall lower reaches (0.3511) > upper reaches (0.3388) > middle reaches (0.3084). The fluctuation pattern over time aligns with the overall trend, with the resilience of upper reaches gradually surpassing that of lower reaches, progressing towards a balanced steady-state, whereas the middle reaches show a significant gap compared to the upper reaches and lower reaches. This may result from the combined effects of unstable water flow, population pressure, soil erosion, and IS in the middle reaches. As shown in Fig. 4b, at the city level, the top six cities in terms of average WEFNR are: Yinchuan (0.4791) > Wuhai (0.4695) > Shizuishan (0.4627) > Ordos (0.4182) > Dongying (0.3926) > Wuwei (0.3883). Except for Dongying, which belongs to the lower reaches, all other cities are in the upper reaches. The bottom six cities are: Ulanqab (0.2232) < Xining (0.2499) < Tianshui (0.2557) < Shangluo (0.2627) < Longnan (0.2638) < Guyuan (0.2659). Except for Tianshui and Shangluo, which belong to the middle reaches, the others are in the upper reaches. Therefore, the upper reaches exhibit significant spatial heterogeneity, which may be attributed to the mismatch between industrial division and functional zoning, resulting in notable differences in economic development, technology, and efficiency.

The spatial distribution trend of the average WEFNR in the YRB was simulated and interpolated using ordinary Kriging, as shown in Fig. 5. In terms of spatial distribution, the WEFNR in the YRB from 2013 to 2022 exhibits a symmetrical pattern along the Hu Huanyong Line, with a spatial form of “upper reaches bulges, middle reaches depressions, and lower reaches tail-raising” In the east-west direction, the fitted curve shows a distribution trend of higher values in the east and west and lower values in the middle, with prominent peaks forming “high-high clusters” in the western and eastern regions. In the north-south direction, the fitted curve generally exhibits a pattern of higher values in the central region and lower values in the northern and southern regions. This indicates that regions with better WEFN are mainly concentrated along the central main stream of the YRB, where urban agglomerations have significantly higher WEFNR than other areas, with the Ningxia Yellow River Urban Agglomeration, the Central Plains Urban Agglomeration, and the Shandong Peninsula Urban Agglomeration being particularly prominent. This spatial trend also suggests that the construction of urban agglomerations in the YRB facilitates the free flow of resources between cities, enabling complementary advantages and coordinated resource allocation, thereby enhancing individual cities’ capacity to resist risks and recover from emergencies.

Structural characteristics of the WEFNR association network in the YRB

Based on the MGM, a spatial association network of WEFNR for 60 sample cities from 2013 to 2022 was constructed, identifying 717 inter-city WEFNR connections. The spatial association network diagram of WEFNR in the YRB was drawn, and its overall characteristics, individual characteristics, and clustering features were statistically analyzed, with the results shown in Fig. 6.

-

(1)

Overall characteristics

The maximum potential number of spatial relationships in the inter-city network is 3540, and this study identified 717 actual WEFNR spatial associations, yielding a network density of 0.2030, a network degree of 1, a network efficiency of 0.7633, and a network hierarchy of 0. In terms of network density, the network exhibits relatively low compactness, indicating substantial potential for improvement in inter-city spatial relationships. Regarding network connectivity, the overall network exhibits strong interconnectivity, demonstrating good accessibility with no isolated cities. Based on network efficiency, the network shows good overall transmission and connectivity performance, though some redundancy exists, indicating a certain level of robustness. The network hierarchy indicates that the inter-city associations are relatively egalitarian, with no strict hierarchical structure, and cities with varying WEFNR scales have symmetrical accessibility relationships.

-

(2)

Analysis of individual characteristics

To reveal the roles and positions of individual cities within the network, this study calculates three structural indicators: degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality.

Degree centrality determines whether a city occupies a central position in the network. There is a significant disparity in degree centrality between upper reaches and lower reaches cities, with the top five cities being Ordos (88.163) > Yulin (77.966) > Dongying (71.186) > Wuhai (54.237) > Zhengzhou (50.847). These cities are concentrated in the upper reaches and lower reaches, emphasizing WEFN coordination and enhancing their resilience to risks through rational resource allocation, positioning them as central nodes in the network. The bottom five cities in degree centrality are: Bayannur (6.78) = Weifang (6.78) < Tai’an (8.475) = Binzhou (8.475) < Dezhou (10.169). Except for Bayannur, which is located upper reaches, these cities are all in lower reaches regions and exhibit limited WEFNR connections with other cities, placing them at the network’s periphery. A comparison of the in-degree and out-degree of individual cities reveals that cities with higher degree centrality have significantly higher in-degree than out-degree, indicating a pronounced siphoning effect on resource factors from other cities. In contrast, cities with lower degree centrality exhibit out-degree significantly greater than in-degree, demonstrating a notable “spillover effect,” with critical factors influencing WEFNR development being in a state of net outflow.

Closeness centrality represents the extent to which a city’s WEFNR is independent of control from other regions. Ordos (88.06), Yulin (80.822), and Dongying (76.623) have significantly higher closeness centrality than other cities, positioning them as central actors capable of quickly establishing connections with other cities. Cities like Weifang (45.038), Binzhou (46.825), and Baiyin (48.361) have lower closeness centrality, positioning them as peripheral actors within the network. Therefore, YRB shows that core cities or resource-based cities form stable WEFN systems through efficient resource allocation and external interactions, enhancing their resilience to shocks. In contrast, peripheral cities struggle to establish flows and exchanges of factors with other cities, resulting in a distinct “core-periphery” structure.

Betweenness centrality reflects the control capacity of each city over resource factors in the construction of WEFNR. The betweenness centrality of Ordos and Yulin accounts for 32.97% of the total, with values of 22.934 and 13.663, respectively. They are followed by downstream cities Zhengzhou (7.927) and Dongying (7.316). This indicates that these cities play a significant intermediary role in the WEFNR network, influencing relationships between provinces. Additionally, these cities can leverage their intermediary roles within the network to influence the allocation of WEF resources in other cities. Other cities are in subordinate positions within the network.

-

(3)

Clustering characteristics

To explore the substructures and interrelationships within the network, a block model analysis was conducted, categorizing the network into four blocks based on the ratio of internal relationships and the differences in external incoming and outgoing connections. The spillover effects between blocks are shown in Table 3, and the density matrix and image matrix are presented in Table 4.

The block model results indicate that the network is primarily characterized by transmission and spillover effects between blocks. Specifically, Block I comprises energy and mineral resource-based cities such as Ordos, Baotou, and Yan’an, as well as regional economic centers like Zhengzhou, Jinan, and Lanzhou. The actual internal relationship ratio within this block is significantly lower than the expected ratio, and its outgoing spillover connections to external blocks greatly exceed its incoming connections, classifying it as a Net Spillover block. Block II includes core cities in the middle and upper reaches of the “Ji”-shaped Bend, such as Xi’an and Yinchuan, which have well-developed agriculture, a strong industrial base, and well-established water rights and water markets. The number of outgoing spillover connections is significantly lower than the incoming connections, resulting in an actual internal relationship ratio much higher than the expected value, classifying it as a Net Beneficiary block. Block III consists of cities primarily focused on resource-based industries such as coal, chemicals, and steel, with relatively homogeneous IS and challenges related to water, soil resources, and ecological restoration. These cities are adjacent to those with high WEFNR and exhibit both internal and external spillover connections, classifying them as a Bidirectional Spillover block. Block IV comprises more developed cities focused on manufacturing and services, as well as developing cities centered on resource-based industries. Some middle and upper-reach cities rely on external markets, while downstream cities possess significant industrial agglomeration and external connectivity advantages. This block has fewer internal spatial connections but plays an intermediary and hub role by facilitating external radiation and reception, classifying it as a Broker block. Regarding inter-block spillover relationships, the Net Spillover block spills over to the Net Beneficiary and Broker blocks. The Net Beneficiary block primarily spills over within its internal cities and, to a lesser extent, to the Net Spillover block. The Bidirectional Spillover block spills over to the Net Beneficiary and Broker blocks. The Broker block primarily spills over within its internal cities and to the Bidirectional Spillover block. This indicates mutual spillover relationships between the Net Spillover and Net Beneficiary, as well as between the Bidirectional Spillover and Broker blocks. There are no direct connections between the Net Spillover and Bidirectional Spillover, nor between the Net Beneficiary and Broker, making their relationships relatively independent within the network.

In summary, some middle and upper-reach resource-based cities and regional economic centers exhibit significant spillover effects within the WEFNR network. Core cities in the middle and upper reaches of the “Ji”-shaped Bend benefit from effective WEF coordination, receiving substantial spillovers of factors, resources, and technologies from other regions. Resource-based cities with homogeneous IS near high-WEFNR cities exhibit active bidirectional spillover and reception, presenting both opportunities and challenges. However, the inclusion of cities reliant on external markets enhances the blocks’ resource allocation and radiation functions. Cities with strong internal and external connectivity, leveraging their locational advantages, can serve as “transmission belts,” indicating significant future development potential. The spillover channels between blocks remain insufficiently smooth, particularly as the Net Beneficiary block has not generated spillover effects on other blocks. Path dependence within blocks has not been fundamentally resolved, and WEFNR barriers between cities remain prominent. A collaborative and interconnected network structure has yet to be established. Therefore, breaking down WEF factor barriers and promoting the free flow of resources between regions should be the primary task in enhancing the WEFNR of the YRB in the future.

Dynamic evolution of the WEFNR association network in the YRB

Based on the phased characteristics of WEFNR, this study divides the observation period into three stages: 2013–2015, 2016–2018, and 2019–2022, constructing spatial association networks for each stage to dynamically analyze the evolution of the structure. The overall and clustering characteristics of the network have not changed significantly. Since individual network structure indicators better reflect the spatial associations of each city, out-degree, in-degree, and three centrality indicators were selected to analyze the evolution of the YRB, as shown in Fig. 6.

As shown in Fig. 7a, the in-degree of the network was generally concentrated between 5 and 7 from 2013 to 2015, shifted to 5 to 12 during 2016–2018, and further concentrated between 7 and 13 from 2019 to 2022, showing a clustering trend. Out-degree was primarily concentrated between 9 and 16 during 2013–2015, with 11 cities having a WEFNR spillover count of 11. Additionally, the spillover levels of Ordos and Yan’an far exceeded those of other cities. During 2016–2018, the out-degree shifted to 9 to 15, with 10 cities reaching a spillover count of 12. Ordos and Yulin continued to show significantly higher spillover levels than other cities. Finally, in 2019–2022, the out-degree concentrated between 10 and 15, with Ordos and Yulin maintaining the highest spillover levels. In summary, the differentiation trend of WEFNR spillover relationships in the YRB is not significant, and the spatial spillover effect has a considerable impact on WEFNR. Therefore, facilitating the flow of WEF resources and factors, enhancing cities’ WEFNR spillover effects, and promoting the spillover benefits of WEFN will be crucial for the coordinated development of WEF in the YRB following climate risks and the COVID-19 pandemic during 2019–2022.

a Frequency distribution of in-degree and out-degree of the spatial WEFNR network in the Yellow River Basin across the three stages (2013–2015, 2016–2018, 2019–2022). b Kernel density estimation of degree centrality distribution of the spatial WEFNR network in the Yellow River Basin across the three stages (2013–2015, 2016–2018, 2019–2022). c Kernel density estimation of betweenness centrality distribution of the spatial WEFNR network in the Yellow River Basin across the three stages (2013–2015, 2016–2018, 2019–2022). d Kernel density estimation of closeness centrality distribution of the spatial WEFNR network in the Yellow River Basin across the three stages (2013–2015, 2016–2018, 2019–2022).

Figure 7b–d shows the dynamic changes in the centrality distribution of the network. Overall, the centrality distributions shifted slightly leftward during the observation period, exhibiting a predominantly unimodal shape with scattered peaks in the tail, indicating a noticeable tailing trend. This indicates a slight decline in the tightness of spatial WEFNR associations among cities in the YRB. Specifically, in terms of degree centrality, the importance of central nodes decreased slightly and then stabilized over the three stages. This suggests a slight reduction in the number and concentration of direct WEFNR associations among cities. The slight increase in advantageous cities led to a minor reduction in the concentration of WEF resources in the existing dominant cities. For betweenness centrality, the number of nodes gradually increased, but the density curve concentrated in the low-value region. The number of cities playing effective regulatory roles in the network increased, but their overall regulatory impact on WEFNR spillovers gradually weakened. In terms of closeness centrality, the number of central nodes increased, but their influence gradually diminished. The overall connectivity of the network structure improved, transitioning from centralization to decentralization. More nodes began to prioritize improving WEFNR. In summary, the number of WEFNR associations between cities increased, and the number of central cities grew. The intermediary regulatory roles of these cities weakened, and the trend toward decentralization intensified. This indicates that more cities are focusing on enhancing WEFNR by accumulating, managing, and regulating WEF resources and factors through technological and institutional innovations. However, barriers between cities still exist.

Formation mechanism of the WEFNR association network in the YRB

-

(1)

Estimation results

Table 5 presents the estimation results of the ERGM. Column (1) shows that the coefficient of Edges is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that the formation of the network is non-random. The coefficient of Mutual is significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the network exhibits numerous bidirectional relationships, reflecting mutual reciprocity between cities. The estimated coefficient of WEFNR is 1.5623, significant at the 1% level, indicating that for each unit increase in a city’s WEFNR, the likelihood of establishing a spatial relationship with other cities increases by 82.67%. Cities with higher WEFNR tend to exhibit a clustered development pattern, relying on connections with other cities’ WEF resources to support their growth. This process facilitates the flow and aggregation of WEF resources and factors across the YRB, accelerating the formation of spatial associations. The baseline model is further extended by incorporating city-specific attributes. Column (2) shows that the coefficient of WEFNR decreases to 1.216, reducing the likelihood of establishing spatial relationships between cities to 77.14%. This indicates that individual attributes influence the formation of spatial relationships. The coefficient of AT is −0.0326, implying that, all else being equal, an increase in average temperature reduces the likelihood of forming spatial relationships between cities by 50.81%. Higher temperatures intensify WEF resource constraints in cities, leading them to restrict resource spillovers and hinder the formation of spatial relationships. The coefficient of IS is −0.0193, indicating that, other factors held constant, optimizing the IS reduces the likelihood of establishing spatial relationships by 50.48%. The rise in the proportion of the tertiary sector increases the pressure of population and economic development on WEFN while facing relatively insufficient WEF resource supply. The coefficients of GFT and IC are 0.0040 and 0.0000, respectively, indicating that larger government size and stronger IC increase the probability of forming spatial relationships by more than 50%. A strong government and technological innovation can accelerate resource flow efficiency between cities and enhance emergency response and resource allocation capabilities. After incorporating the Geonet into the model, the estimation values and significance levels of network self-organization effects and individual attribute effects remain largely unchanged, except for a slight decrease in IS. This indicates that while geographic adjacency slightly increases the probability of forming spatial associations, spatial constraints on the network still persist. Strengthening the free flow of resources across cities and enhancing basin-wide WEF resource allocation remain key directions for improving WEFNR in the future.

Table 5 Regression results of the ERGM. -

(2)

Robustness checks

To ensure the robustness of the estimation results, alternative estimation methods and additional geometric weighting terms were employed for robustness checks. First, the coefficients of the ERGM were tested using the Pseudo-Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MPLE) method. Column (4) of Table 5 reports the MPLE results, showing that the significance of the estimated coefficients remains unchanged and is very close to those obtained using the MPLE method. To avoid statistical inference errors caused by the complex dependencies in digital economy spatial networks, GWESP were included for robustness checks. The results show that after incorporating GWESP, both AIC and BIC values significantly decrease. Column (5) indicates that the coefficient of GWESP is significantly positive, suggesting that geometric weighting of dyadic shared partners between two cities increases the likelihood of forming spatial associations. Cities with multiple WEF linkages are more inclined toward closed development patterns. This further confirms the trend of regional cooperation and interdependence in the evolving network. The signs and significance of other variables in the model remain unchanged, indicating the robustness of the estimation results.

Convergence and evolution trend of WEFNR in the YRB

Network analysis results indicate that the WEFNR among cities in the YRB exhibits a closely connected spatial network structure, with AT, IS, GFT, and IC playing significant roles in the formation of network relationships. To examine whether the regional differences in WEFNR can be narrowed through the externalities released by its spatial network, β-convergence tests are conducted for the entire basin and its upper, middle, and lower reaches. Additionally, the HI is employed to demonstrate the evolution trend of WEFNR in different cities.

Table 6 (1) presents the overall convergence regression results, showing that the β coefficients in all four models are significantly negative, indicating the presence of both absolute and conditional β spatial convergence in WEFNR. Furthermore, the speed of absolute convergence is significantly faster than that of conditional convergence. The convergence speed under network weights is slower than under adjacency weights, and the half-life is also longer. This suggests that the spatial diffusion effect of WEFNR within the network dependency structure is relatively weak, with complex and loose interactions between cities, thereby reducing the capacity for rapid WEF diffusion. Additionally, the longer half-life confirms that WEFNR under the network structure exhibits high stability and path dependency, with relatively slow responses to external shocks. Among the control variables, only IC is significantly negative under adjacency weights at the 5% level, with a coefficient of −0.0000. This indicates that under adjacency conditions, IC suppresses WEFNR convergence to a higher-level steady state. The possible reason is that innovation outcomes are difficult to effectively diffuse through geographic adjacency, and technological innovation often involves resource redistribution, which intensifies competition rather than cooperation among neighboring regions. Therefore, it suppresses the convergence of WEFNR. Under network weights, only GFT is significantly negative at the 1% level, with a coefficient of −0.0025. This suggests that under network conditions, government size inhibits WEFNR from converging to a higher-level steady state. The possible reason is that larger government size leads to resource competition and strategic fiscal expenditure among governments, resulting in inefficient resource utilization. Strategic fiscal spending often focuses excessively on economic public goods and short-term non-economic public goods. As a result, there is relatively insufficient investment in traditional non-economic public goods dependent on WEF resources. This leads to a more dispersed rather than convergent WEFNR.

Considering the heterogeneity across the upper, middle, and lower reaches of the YRB, Table 5 (2)–(4) reports the regional convergence regression results. For absolute β spatial convergence, the β coefficients of all models are significantly negative, indicating that WEFNR in all cities exhibits absolute β spatial convergence. The absolute convergence speed follows the pattern of “lower reaches > middle reaches > upper reaches.” Compared with absolute convergence, the conditional convergence speed of cities under network weights improves, and the convergence period shortens. The network’s acceleration effect on the convergence of the upper and middle reaches is relatively strong. The likely reason is that the initial WEFNR in middle-reach cities is relatively low, but they have a significant latecomer advantage. This is particularly evident with the promotion of soil erosion control and the rise of central regions in the YRB. The complementary advantages within central city clusters and the increasing multi-threaded network connections are becoming more apparent. The WEFNR in upper-reach cities is relatively high but exhibits significant disparities. Network-driven rapid resource sharing accelerates WEFNR convergence. Among the control variables, only the CI of the middle and lower reaches is significant under network weights. Compared to the entire basin, the insignificance of GFT in individual sub-basin samples can be attributed to the reduced cross-regional dependency between the upper, middle, and lower reaches, weakening or obscuring the influence of government size. Additionally, resource competition and strategic expenditure biases among local governments in the upper, middle, or lower reaches are less pronounced, leading to the insignificance of GFT in single-basin samples. Given the generally low CI in the YRB, the innovation gap is more pronounced in upper-reach cities due to their lower economic development, making CI insignificant in the upper reaches.

At the city level, the HI of individual cities, as shown in Fig. 8, reveal an average HI of 0.4785 for WEFNR in the YRB. This indicates a weak likelihood of a reverse change in the future development trend of urban WEFNR resilience compared to the current trend. Among the cities, 42% in the YRB show a future WEFNR development trend that aligns with the current trend, indicating a positive correlation. 25% of the cities exhibit a moderate negative trend, suggesting that over one-quarter of the cities may enter a fluctuating phase in their future WEFNR development. In terms of spatial distribution, the HI demonstrates significant heterogeneity across regions. Areas with weak divergence trends are primarily concentrated in the central and middle-lower reaches. Cities exhibiting positive trends are concentrated in the central cities of the the “Ji”-shaped Bend urban cluster. This further confirms the effectiveness of the the “Ji”-shaped Bend urban cluster in promoting the free allocation of resources and enhancing WEFNR.

Discussion

Further analysis of the WEFNR framework

The concept of the nexus was proposed to transcend the traditional “siloed” mindset and promote multi-sectoral and cross-sectoral resource management. The WEFN has been widely adopted as an integrative framework for analyzing resource system interactions, but its practical utility and effectiveness in implementation have drawn increasing critical attention. Allouche et al. (2014) pointed out that the WEF nexus is often constructed as a seemingly neutral tool of technocratic governance, while in fact masking power asymmetries and political tensions inherent in resource allocation. Such an efficiency-driven governance logic is prone to fall into the dichotomy of “nexus nirvana”—an overly idealistic pursuit of multi-objective synergy—or “nexus nullity”—a hollow concept lacking clear pathways for action. Mehta et al. (2019) argued that although the term “nexus” has gained popularity in policy and academic discourse as a novel concept for promoting sustainability through integration, it increasingly suffers from conceptual vagueness, unclear implementation pathways, and ineffective practice. Based on a review of water-centered nexus frameworks, Hussein and Ezbakhe (2023) argued that such “buzzword-like” concepts tend to become detached from reality in the absence of institutional support and practical instruments, and fail to be translated into actionable policy. Building on this, their study of the “Water–Employment–Migration” (WEM) nexus in the Middle East and North Africa revealed that although regional organizations frequently adopt WEM terminology at the policy level, the framework suffers from high uncertainty in terms of definitions, implementation mechanisms, and participation modalities—particularly with youth participation remaining largely symbolic rather than substantive. These critiques suggest that nexus frameworks should not remain confined to abstract models and discursive integration, but should emphasize local embeddedness, governance adaptability, and institutional enforceability. Against this backdrop, this study, guided by the concept of evolutionary resilience, adopts a bottom-up approach rooted in management and planning practices in the Yellow River Basin to construct a regionally adaptive WEFNR theoretical framework, which builds on core resilience principles while further emphasizing regional adaptability and system complexity. Thus, this study not only expands the theoretical boundaries of evolutionary resilience but also offers a new interpretive structure for existing findings, providing a potential pathway to bridge the gap between abstract theorization and governance practice.

The WEFN system exhibits three interrelated attributes: openness, self-organization, and trade-offs. Openness is demonstrated through interactions between the system and ecological infrastructure, climate change, and policy management. Self-organization refers to the dynamic coordination mechanisms among the water, energy, and food subsystems, while trade-offs emerge from competition over resource-use objectives among these subsystems. This dual structure—comprising internal linkages and external interactions—shapes the evolutionary trajectory of the WEFN system under disturbance and reflects its core resilience phases: resistance, adaptation, and recovery. Based on constructivist grounded theory analysis, the study aligns the four key WEFNR dimensions with these core resilience features, dividing them into two structural layers. Internal linkages emphasize security and efficiency within the resource system, whereas external interactions focus on adaptation to external pressures and system-level support. Specifically, Cross-Scale Resource Coordination underpins internal coordination and serves as the foundation for the functioning of other dimensions. Systemic Adaptive Dynamics captures the system’s dynamic response to external shocks, relying on internal coordination and feedback loops. Institutional Synergy and Governance Depth provides societal-level regulation and support, integrating policy, management, and public participation. Equitable and Functional Eco-Infrastructure links the WEF system to its environmental context by ensuring fundamental resource supply and the ability to absorb shocks. Previous studies offer important validation for this dimensional structuring and its underlying logic. For instance, Si et al. (2019), through a multi-objective optimization study of upstream reservoir systems in the Yellow River Basin, demonstrate the trade-off between allocation efficiency and system stability, supporting the “connectivity–allocation–efficiency” pathway outlined in this study. In terms of adaptive capacity, Liu and Zhao (2022) emphasize the importance of feedback mechanisms among subsystems in maintaining long-term system adjustability, reinforcing the inclusion of adaptability as a core resilience element. Furthermore, Nie et al. (2025) find that institutional support, governance capacity, and regional heterogeneity are closely linked in explaining coupling mechanisms across nine provinces, validating this study’s differentiation of institutional and social dimensions. In the ecological dimension, Wang et al. (2023) evaluate the impact of ecological resources on WEF coupling efficiency in Shandong Province, offering regionally grounded empirical support for ecological resilience. In sum, the WEFNR framework developed through constructivist grounded theory provides an integrated and context-sensitive lens to understand the interrelationships among the four key dimensions. It offers systematic theoretical support and practical relevance for enhancing WEFNR in the Yellow River Basin through regionally tailored strategies.

Evolution of WEFNR in the YRB and the role of urban agglomerations

From the perspective of the evolutionary process, the WEFNR in the YRB exhibits distinct phased characteristics, marked by periods of shocks and adjustments. The sustained growth of WEFNR from 2013 to 2015 was closely linked to policy planning and strategic guidance. As early as 2012, the Chinese government approved the Comprehensive Plan for the YRB, which emphasized strengthening ecological protection and integrated resource management, laying the foundation for the overall rise of WEFNR. The comprehensive reform of agricultural water pricing implemented in 2014 promoted water-saving irrigation and improved water resource utilization efficiency in the YRB, where water is a rigid constraint. This ensured stable grain production and provided a reliable water supply for industrial use, particularly for energy production. Additionally, after 2013, national policies on energy development in the YRB increasingly focused on the growth of clean and renewable energy sources. The rapid development of wind and solar energy projects in the YRB reduced the dependence of fossil energy production on water resources through substitution effects. However, WEFNR experienced a sudden decline in 2016, followed by another peak in 2018, a fluctuation closely related to extreme climate events. At the beginning of 2016, the YRB experienced severe cold wave conditions and significant temperature anomalies, which had a substantial impact on agricultural production and energy supply. Additionally, the region’s existing severe water scarcity was exacerbated by extreme weather, leading to decreased industrial water use efficiency, reduced energy supply, and diminished grain production capacity. After this climatic shock, the YRB improved its resource management and climate adaptability through the promotion of advanced irrigation technologies, the development of water rights markets, and adjustments in energy structure, leading to a gradual recovery of WEFNR between 2017 and 2018. From 2019 to 2022, the low-level fluctuations of WEFNR were closely linked to variations in precipitation, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and flood disasters. In 2019, the decline in precipitation led to an increase in water resource utilization efficiency, given the rigidity of water use in agriculture and industry. However, ecological restoration and regulatory measures following the symposium on ecological protection and high-quality development further affected energy supply. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted supply chains, significantly impacting production and daily life. In 2021, the YRB was affected by a once-in-a-century flood disaster, impacting WEFNR. Despite multiple shocks, the WEF system’s resilience improved in 2022, and WEFNR showed an upward trend.

From a spatial perspective, high WEFNR aligns significantly with the development of urban agglomerations along the Yellow River. The construction of urban agglomerations in the YRB enhances WEFN’s resilience to external shocks through resource optimization, infrastructure connectivity, industrial coordination, technological and institutional innovation, and ecological protection. According to the Outline of the YRB Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development Plan, urban agglomerations serve as growth poles for regional economic development and are the primary carriers of population and productivity distribution in the YRB (Al-Saidi and Hussein, 2021). As hubs for advanced production factors, drivers of new urbanization, and key areas for optimizing the economic development of the YRB, urban agglomerations play a critical role in facilitating the positive spillover of resources and supporting the sustainable development of the basin’s economy. In terms of IS, the urban agglomerations in the YRB have a high proportion of industrial and agricultural sectors, with key industries focusing on coal and oil extraction, metal smelting, and other heavy chemical industries. In agriculture, the region boasts extensive farmland and irrigation systems, with provinces like Shandong and Henan serving as important production bases for grain, cotton, and oilseeds in China (Deng et al., 2021). These cities possess strong endogenous dynamics and resource allocation capabilities within the WEFN system, and as economic growth poles, their advanced technology and institutional innovations provide a solid foundation for WEFNR. Therefore, enhancing resource spillovers and overall coordination among urban agglomerations is crucial for improving WEFNR in the YRB.

Characteristics and formation mechanism of the WEFNR `rk in the YRB

This study integrates the MGM with SNA to investigate the spatial association network characteristics of WEFNR in the YRB and explores the network formation mechanism using the ERGM, filling a theoretical gap in the research on WEFNR spatial association networks in the YRB and providing direct empirical evidence for their existence.

From the overall, individual, and clustering characteristics of spatial association, it can be observed that the spillover effects in the YRB are mainly concentrated in resource-based cities and regional economic hub cities. Additionally, from a basin-wide perspective, more upper and lower reaches cities occupy central positions, while each of the upper reaches, middle reaches, and lower reaches exhibits a distinct “core-periphery” structure. The spillover effects exhibited by resource-based cities are highly correlated with the National Sustainable Development Plan for Resource-Based Cities (2013–2020) issued by the Chinese government in 2013. In the YRB, over 50% of cities are resource-based, with abundant energy resources within the WEFN. The intelligent construction of irrigation zones and the active water market contribute to the formation of an efficient and resilient WEFN. Furthermore, these cities’ increased emphasis on ecological infrastructure provides stronger support for the WEFN, enhancing its resilience (Hua et al., 2023). Regional economic hub cities naturally exhibit stronger WEFNR spillovers due to their economic development and resource allocation capabilities. From a basin-wide perspective, the upstream regions, characterized by richer energy resources and higher ecological protection requirements, and the downstream regions, marked by concentrated population and economic activities, form a supply-demand complementary model that determines their central positions in the WEFNR spatial association network. Meanwhile, national policies on water resource allocation (Wang et al. (2022)), ecological compensation mechanisms (Hoff, 2011), and interregional cooperation (Liu et al., 2020) further enhance the synergy between upper reaches and lower reaches, with the middle reaches primarily serving as a corridor (Feng et al., 2023). The “core-periphery” characteristics within each sub-basin arise from the uneven distribution of regional resource endowments. Cities with core resources or higher levels of economic development tend to leverage their resource advantages and attractiveness to further consolidate their central positions. In contrast, cities with lower development levels and unclear positioning are more likely to become marginalized. This internal differentiation within the basin reflects the complexity and hierarchical nature of the spatial association network.

Although existing studies have validated the driving mechanisms of these factors in WEF and its individual characteristics, this study further enriches and supplements them from the perspective of resilience, as illustrated in Fig. 9. From the perspective of the endogenous structure of the network, the formation of the WEFNR spatial association network in the YRB demonstrates a clear structural preference, indicating that inter-city connections exhibit a certain degree of selectivity, with spatial correlations more easily established between cities with high resource flow efficiency and complementary WEFNR demands. Therefore, the tendency for reciprocal cooperation between cities is evident, where the correlation is not merely a unidirectional input or output but rather a mutual dependence and collaboration in WEF resources. The mutual dependence and collaboration of city nodes within the overall structure of the network also explain why cities like Ordos exhibit a significant siphon effect when analyzing individual network characteristics, yet act as “net spillover” nodes in cluster analysis. From the perspective of individual network attributes, rising average temperatures directly impact water supply, and as WEF operates as an integrated system, resource competition becomes more pronounced, prompting cities to prioritize the protection of local resources to reduce outflows. Although IS optimization promotes economic development, it increases reliance on population agglomeration and infrastructure, further intensifying the demand pressure on WEF resources. Given the relatively limited WEF resource supply capacity in the YRB, IS optimization has failed to balance resource demand and supply in the short term, thereby hindering the formation of inter-city resource linkages. A strong government, through policy coordination, resource allocation, and the establishment of regional cooperation mechanisms, enhances the efficiency of inter-city resource flows and reduces institutional barriers to regional resource mobility. The enhancement of innovation capacity drives technological progress, particularly in resource allocation and efficient utilization, significantly strengthening the spatial correlation of WEFNR between cities by improving emergency response capabilities and optimizing resource allocation pathways. From the perspective of external network effects, geographic proximity typically reduces the cost and risk of resource flows, thereby enhancing resource-sharing capabilities among neighboring cities. However, the impact of adjacency effects is constrained by regional infrastructure, policy coordination, and differences in resource endowments. Therefore, overcoming geographical constraints and enhancing cross-regional resource flow and cooperation capabilities will be a key focus for optimizing the WEFNR spatial association network in the future.

Trends in changes of the WEFNR in the yellow river basin and strategies for collaborative optimization

Considering network externalities and geographical proximity, a β-SCM is employed to examine the spatial convergence of WEFNR in the YRB and its upper, middle, and lower reaches. The results show that regional disparities in WEFNR can be continuously reduced and tend to converge through the externalities released by the spatial association network. At the city level, the HI results suggest a weak possibility of future trends diverging from existing ones. Regions with weak divergence trends are primarily located in the middle and lower-middle reaches, while cities with positive trends are concentrated in the core cities of the “Ji”-shaped Bend urban agglomeration, consistent with the conclusions drawn from the spatial association network, further validating the robustness of the findings.

In the spatial β-conditional convergence analysis, the overall innovation capacity of the basin is significant under conditions of geographical proximity, corroborating the conclusion that neighboring regions exhibit stronger technological spillover effects. Meanwhile, the overall government size is significant under network correlation but not within individual sub-basins, which is closely related to the presence of the Yellow River Conservancy Commission (YRCC). As water resources serve as a rigid constraint in the YRB, water holds a critical position in WEFN (Jin et al., 2021). The YRCC’s allocation and rational distribution of water resources are crucial for the overall WEFNR of the basin. However, such strict allocation inevitably leads to uneven distribution, making it difficult for local governments to respond swiftly under such regulatory conditions to enhance WEFNR during extreme events. Notably, GFT and CI are significant in both the ERGM and spatial β-convergence analyses, but their directional effects differ substantially: both are positively significant in the ERGM, while negatively significant in the spatial β-convergence analysis. The differences in GFT results indicate that in network correlations, government size serves as a crucial bridge that effectively promotes regional cooperation and strengthens linkages; however, in regional convergence, an excessively large government size may exacerbate resource imbalances, hindering the narrowing of development gaps. Therefore, it is necessary to further explore the marginal effects under different thresholds of government size and optimize government scale to achieve the synergistic goals of strengthening WEFNR network correlation and spatial convergence. The differences in CI results reflect the regional heterogeneity of technological progress. Under spatial adjacency, the technological diffusion and knowledge spillover effects of innovation capacity are stronger, thus enhancing the connectivity of the WEFNR network. However, the concentration effect in the network context may further exacerbate technological disparities between regions, leading to resource competition. Therefore, it is essential to further optimize the regional innovation diffusion mechanism, promote cross-regional technological sharing and collaborative innovation, and achieve the synergy between WEFNR network optimization and spatial convergence. The HI of individual cities corroborates with the regional convergence analysis, revealing significant regional heterogeneity in the future WEFNR of the YRB, with core nodes and peripheral areas diverging in resource utilization, technology diffusion, and policy support. Therefore, in the future, efforts should focus on strengthening regional coordination mechanisms, enhancing the driving role of core cities, and optimizing resource allocation and policy instruments to promote balanced and sustainable development of WEFNR across regions.