Abstract

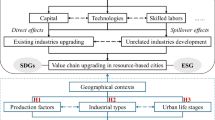

Achieving sustainable development in mining cities is a pressing global challenge, particularly in resource-dependent economies such as China. By applying an improved Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI) and a geographical detector model, this paper examines the spatial and temporal evolution of sustainable development capacity across the life cycles of China’s metal resource-based cities (MRBCs). Our findings reveal a notable spatial heterogeneity among MRBCs, across 17 studied cities in 2021, with averages of 38.4%, 34.1%, and 27.6% for natural, human, and produced capital, respectively. From 2011 to 2021, the sustainability of MRBCs has increased by 31.8%, driven by increased produced capital and a rising emphasis on human capital. Renewable natural capital was identified as the most critical factor influencing the sustainability of MRBCs. Furthermore, as MRBCs progress through their life cycles, they experience a gradual decrease in natural capital, coupled with gradual increases in produced and human capital, with recessionary cities exhibiting the lowest levels of overall sustainability. This paper contributes by demonstration how the IWI framework can guide resource optimization, strengthen urban resilience, and inform sustainability strategies in mining cities globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal resources are foundation to stable supply chains, essential for ensuring resource availability and fostering emerging industries (Lèbre et al., 2020). Metals such as copper and aluminum are particularly vital to sectors like electrical, construction, and transportation due to their high conductivity, strength, and recyclability, qualities that make them indispensable for renewable energy systems and clean energy technologies (Akcil et al., 2020). As the world transitions toward a low-carbon economy, these key metals have become central to clean energy development, playing a critical role in shaping renewable energy markets (Sovacool et al., 2020). They support energy storage and transmission systems vital for integrating renewable energy sources. However, their critical role in low-carbon technologies confers both strategic and economic importance, while also exposing them to heightened risks of supply shortages and price volatility due to limited availability (Akcil et al., 2020). Against a backdrop of growing global demand, whether metal resources can adequately support the low-carbon transition in energy systems has become a key concern for global sustainability.

Metal resource-based cities (MRBCs) represent a unique urban category where the extraction and processing of metal minerals have driven the primary economy (Sovacool et al., 2020). These cities hold strategic significance and have greatly contributed to China’s industrial foundation (Sun et al., 2023). After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, annual production of non-ferrous metals was only 13,300 tons. By 2002, production exceeded 10 million tons, marking a growth of roughly 760% (China Non-Ferrous Metals Industry Association, 2009). In recent years, this trend has continued, with output rising from 60 to 70 million tons in just four years (Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, 2024). However, the high-intensity resource exploitation has triggered severe sustainability challenges in MRBCs, with over half of these cities now in recession (Qing et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2021). Compared to other cities, MRBCs suffer more severe environmental degradation, declining fiscal revenues, and large-scale population migration, complicating efforts for ecological restoration and economic transformation. These challenges are further exacerbated by China’s declining domestic metal reserves and growing dependence on external supplies, underscoring the urgent need to promote sustainable development in MRBCs. As the world’s largest metal producer, consumer, and trader, China accounts for over 50% of global metal consumption. Given China’s key position in the global metal industry chain, the spatial and temporal evolution of sustainability in China’s MRBCs provides a lens perspective for understanding the complex mechanisms of resource-based cities (RBCs) through the interaction among population, capital and environment. Thus, evaluating the sustainability of MRBCs in China has implications for the similar cities worldwide.

The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a global blueprint for addressing critical areas affecting humanity and the planet. Resource-intensive cities like MRBCs are essential for driving the sustainable development agenda, yet they face social risks and environmental degradation driven by urbanization, population growth, and supply volatility, threatening current and future generations (Wan et al., 2015; Wiedmann and Allen, 2021). Despite these challenges, MRBCs have the potential to balance economic growth, social inclusiveness, and environmental well-being, positioning them as pivotal players in the global sustainable development transition (Xiao et al., 2022). To achieve successful transformation, MRBCs require effective monitoring, evaluation, and target-setting, guided by quantitative and qualitative metrics to inform policy and ensure long-term resilience. However, implementing the SDGs at the city level is complex (Sharifi et al., 2024), particularly given the varied stages of transformation among MRBCs. China has committed to international responsibilities for sustainable governance and has prioritized the transformation RBCs through targeted initiatives (The State Council, 2013; NDRC, MOF, MNR, 2021).

Emerging literature on RBCs covers topics, such as land use efficiency (Li et al., 2024; Song et al., 2022), ecological sustainability (Wu and Bai, 2022; Wang, 2024), and urban resilience (Sun et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023), all aiming to foster sustainable prosperity. Researchers have also explored policy impacts on transformation outcomes, including civilized city policy (Fan and Zhang, 2021; Li et al., 2022) and unintended social and environmental benefits of sustainability policies (Wang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022a; Chen, 2023). Special attention has been given to MRBCs, whose ability to sustain resource supply is crucial. If transformation efforts stall, these cities risk dual economic and social crises, stemming not only from unbalanced ecological development caused by resource depletion and industrial homogeneity (Yang et al., 2023a; Wang et al., 2021), but also from social instability exacerbated by institutional inadequacies and governance dilemmas (Yang et al., 2023b; Svobodova et al., 2022). However, there remains a significant gap in assessing the sustainability and transformation drivers of MRBCs. Given their heavy reliance on metal resources and the recessionary state of many, a focused examination of their sustainability is crucial to identifying viable pathways for accelerated transformation in China.

The urgency of this study is heightened by rapid shifts in the global energy landscape and China’s sustainability commitments, as reflected in China’s alignment with the Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015) and its subsequent commitment to the SDGs. These milestones mark China’s effort to balance industrialization with sustainability, especially under its “dual carbon” goals. Consequently, a comprehensive framework capable of measuring long-term sustainability at the city level is urgently needed (Engelbrecht, 2016). The Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI), a multi-dimensional indicator of sustainable development, offers a promising approach by integrating ecosystem services and localizing metrics to cities. The IWI provides a holistic assessment of sustainable development (UNEP, 2023; Dasgupta et al., 2022) and insights into economic well-being (Arrow et al., 2004; Dasgupta et al., 2015). Previous studies have widely applied the IWI at national and regional levels, including analyses of long-term wealth change in Japan (Ikeda et al., 2017), natural capital management (Islam and Managi, 2022), provincial-level sustainability performance in China (Fan et al., 2022), and transformation monitoring of capital in national innovation demonstration zones (Xue et al., 2022). The IWI’s capacity to quantify capital across economic, social, and environmental dimensions makes it suitable for assessing the wealth accumulation and depletion in MRBCs at various stages. Localizing the theoretical and empirical approaches of the IWI provides valuable insights into human well-being and targeted sustainability measures for MRBCs.

MRBCs differ in their resource endowments and development pathways, leading to varied capital accumulation and life cycle stages. Sustainable MRBCs emphasize social inclusiveness and equity, supporting regional resource allocation and enhancing long-term competitiveness and resilience. Analyzing the spatial distribution of inclusive wealth and capital structure in these cities helps reveal sustainable development potential and facilitates high-quality urban transformation. Prior studies indicate that while human and produced capital drive sustainable economic growth, natural capital is often constrained (Zafar et al., 2019). Assessing the evolution of inclusive wealth in MRBCs allows us to evaluate sustainability and explore transformation drivers, and guide strategies for achieving balanced economic development and social well-being. According to the National Sustainable Development Plan for RBCs (2013–2020), MRBCs are categorized by the life cycle stage: growing, mature, recessionary, and regenerative. Analyzing their sustainable evolution pathways across these stages can identify common characteristics and challenges, enabling targeted policies to avoid the “resource curse”.

The contributions of this research are multifaceted: (1) First, this study assesses the sustainability capacity of MRBCs by examining variations in capital structure and the heterogeneity of spatial distribution. (2) Second, it analyzes the spatial and temporal evolution of inclusive wealth, identifying the impact of different capital types on sustainability and discussing the mechanisms by which these capitals promote inclusive wealth development. (3) Third, it investigates the spatial differentiation and correlation characteristics of MRBCs, using the geographical detector model to uncover sustainability drives and inform targeted interventions. (4) Finally, it provides based on identified evolutionary pathways, provides policy recommendations tailored to promote sustainability across the different life cycle stages of MRBCs.

Methods and data

Inclusive wealth index

The inclusive well-being accounting method calculates the marginal contribution of each asset type to social welfare, represented by the shadow price of evaluated assets. Capital assets in the IWI are categorized into human capital (HC), produced capital (PC), and natural capital (NC). Unless otherwise specified, all values are expressed in Chinese currency (CNY) at constant year 2000 prices.

In Eq. (1), the variables PHCit, PPCit, and PNCit represent the stock of HC, PC and NC in city i in year t. The shadow prices are denoted as Hit, Pit, Nit respectively. Due to the finite carrying capacity of resources and population growth, wealth dilution can occur (Hamilton and Clemens, 1999). Therefore, assessing regional sustainability requires a combination of IWI and IWI per capita, which is calculated as the ratio of IWI to the resident population. This study adopts key parameter values and capital indicators adjusted according to localized capital accounting practices in China, aiming to improve the applicability of the IWI framework within the context of China’s social and economic environment. To assess the robustness and validity of the IWI results, we conduct a sensitivity analysis to examine how variations in these key parameters may affect the outcomes and conclusions (see supplementary material 1).

(1) Human capital accounting

HC is calculated from the stock (H) and the shadow price per unit of HC (PHC) (UNU-IHDP, 2012).

In Eq. (2), the term eEdu·ρ depends on the region’s educational level, where Edu represents educational attainment, ρ represents the rate of return on education of 6.8% (according to Li, 2023), and P represent the working age population. Here, Edu is proxied by the average number of schooling years per person in each city. Equation (3) reflects the present value of lifetime income for PHC, calculated using the average employee salary on duty (\(\bar{r}\)) from 2000 to t, expected working years (T), and the discount rate set at 8% (Cheng et al., 2022).

In Eq. (4), CDRit represents the crude death rate in city i at year t, with k as the age groups, and the population ratio (proa) reflecting the proportion of different age groups within the total population aged 15–64. The distance to the retirement age, avdk, is the absolute difference between the midpoint of each age group and the retirement age (set at 57.5, the average for Chinese men and women). The labor force aged 15-59 is divided into age groups.

(2) Produced capital accounting

The perpetual inventory method is used to calculate the PC stock.

For produced capital, Eq. (5) defines K0i, as the initial capital stock of city i, with the base year set at 1978. The constant depreciation rate (δ) is assumed at 6%. Investment in city i at year t is denoted by \({I}_{{li}}\). In Eq. (6), \({I}_{0i}\) denotes the investment level of city I in 1978, and γ represents steady growth rate, derived as the geometric annual GDP growth rate from 1978 to t.

Gross fixed capital formation serves as primary indicator for investment (Zhang et al, 2004), with investment data (Iit) calculated using city-level fixed capital investment (FCIit) adjusted by a provincial correction factor (CF).

The investment price index, based on the provincial fixed asset investment price index (IPI) is used as the investment price index. The investment implied deflator (IID) serves as a proxy for missing IPI data prior to 1990. It is calculated using gross fixed capital formation (FCF) and the gross fixed capital formation index (FCFI) (Ye, 2010; Zhang et al., 2004).

(3) Natural capital accounting

The NC consists renewable capital (NCR) and non-renewable natural capital (NCN).

Equation (10) details the wealth of coal (WFOit) and metal resourced (WMit), including iron, copper, lead, manganese, zinc, gold and silver. In Eqs. (11) and (12), f, SWfit (SMfit), PFft (PMft), and RFft (RMft) refer to resource type, reserves, shadow price, and rental rate of fossil or metal resource. The shadow prices of coal, iron, and manganese are calculated as the ratio of industrial output value by mineral yield from 2000 to year t, while the prices of other resources are based on international market data, adjusted to 2000 constant prices using the US GDP deflator from World Bank data source. Rental rates are determined from the net profit of listed companies in respective industries.

NCR is accounted for by improving the UNEP framework through the incorporation of ecosystem service value equivalence factors per unit area, following the method of Xie et al. (2003, 2015).

In Eq. (13), Ajk denotes the area of ecosystem j, and Vjk represents the per-unit value coefficient of ecosystem service type k within that ecosystem. Equation (14) introduces Di the standard equivalence coefficient for city i at year t, with D representing the national standard equivalence coefficient. The correction factor e is computed as the ratio of city-level grain yield per unit area in 2010 to the national grain yield per unit area in the same year.

Geographical detector model

Geodetector is employed to detect spatial heterogeneity in geospatial data and to reveal the driving forces behind spatial and temporal evolution (Goodchild and Haining, 2004; Wang et al., 2010). The factor and interaction detection modules are used to analyze the sustainability driver, with the spatial correlation between X and Y represented by q.

In Eq. (15), L is the number of levels of each IWI impact factor, Nh is the number of IWI samples associated with the factor at level h, N is the total sample size, σh is the variance for factor level h, and σ is the total variance across the study area.

Data sources

For human capital (HC) indicators, data on educational attainment (Edu) and working age population (P) are sourced from the Sixth and Seventh National Population Censuses. Data on mortality, salary, and permanent resident are obtained from each city’s statistical yearbook. For produced capital (PC), fixed capital investment (FCI) data are obtained from city or provincial Statistical Yearbook. Data of IPI is from the China Price Statistical Yearbook, and the FCFI is from the Gross Domestic Product of China (1952–1995). For natural capital (NC) data on mineral reserves are collected from the Mineral Resources Plan, city Statistical Yearbooks, and official government websites. For missing values, provincial data are allocated to cities based on industrial output. Resource market prices of coal, iron, and manganese are from the China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook. The grain yield per unit area is from the Statistical Yearbook of City and the China Statistical Yearbook. Ecosystem services encompass farmland, forests, grasslands, wetlands, and land designated for water resources and water conservancy facilities. Data on these areas are sourced from the Statistical Yearbook of City, the Second and Third National Land Survey, and official government websites.

According to the Macroeconomic Research Group of National Planning Commission (2002), 12 cities were initially classified as non-ferrous metal cities and 8 as ferrous metal cities. Subsequently, the State Council identified typical depleted RBCs in three phases, comprising 14 non-ferrous metal and 6 ferrous metal cities. This paper integrates the list of RBCs outlined in the National Sustainable Development Plan for RBCs (2013–2020), selecting county-level cities and above as the unit of analysis. Based on the dominant type of metal mineral resource, a total of 17 MRBCs are identified as the final study sample (Table 1).

To explore the temporal evolution of the IWI, this study selects 2011 and 2021 as key reference year for China’s MRBCs. The year 2011 represents a critical baseline, making a decade after the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), while also reflecting preconditions prior to the release of the national sustainable development plan. The year 2021 is a key year for the implementation of the SDGs five years after their adoption and represents the latest available data. This option allows a more comprehensive assessment of the evolution of long-term IWI.

A set of potential drivers influencing IWI changes in MRBCs was identified, based on a comprehensive framework encompassing HC, PC, and NC. Specifically, demographic factors such as education attainment (Edu) and working age population (P) were selected to reflect key attributes of human capital. To represent industrial development, the proportion of primary and secondary industries was used as a proxy indicator of traditional capital (TC), while the proportion of tertiary industries reflects intangible capital (IC). Renewable natural capital wealth (NCR) and non-renewable natural capital wealth (NCN) were chosen to represent NC conditions.

Results

Spatial heterogeneity in inclusive wealth performance among China’s MRBCs

In 2021, the IWI among MRBCs varied nearly twenty-fold, ranging from 250.5 billion yuan to 5152.9 billion yuan (see Fig. 1a). This significant gap highlighted substantial inequality in inclusive wealth distribution. To further examine regional inequality by capital structure, three urban clusters were identified based on their capital composition, with sample cities illustrated in the pie charts in Fig. 1a.

a The map shows color gradients indicating total IWI (unit: billion yuan), from light (low IWI) to dark (high IWI). MRBCs are categorized into three groups by capital share, and pie chats illustrate the capital composition within each cluster. b Comparison of IWI per capita and IWI by four capital types.

Natural capital (NC)-dominated cities constituted majority of the sample, with an average NC share of 54.6% in 2021. The high proportion largely depended on initial endowments, placing these cities primarily in China’s south-central and north-western regions. The result was a wide variation in wealth within these clusters, including the highest IWI in Altay prefecture and the lowest in Dexing. Notably, Dexing ranked first in the proportion of non-renewable natural capital (NCN), which raise serious sustainability concerns. To assess MRBCs sustainability, both IWI and IWI per capita in 2021 were analyzed (see Fig. 1b). Cities dominated by NC generally demonstrated greater sustainability capacity, as shown by their above-average IWI (2029.3 billion yuan) and IWI per capita (1883.3 thousand yuan). This strength was attributed to a high share of renewable natural capital (NCR) averaging 52.9%, which will remain stable with sustainable management. For example, Altay Prefecture and Shaoguan ranked first and third, respectively, in IWI and IWI per capita among MRBCs. However, smaller populations could yield lower IWI but higher IWI per capita, as seen in Jinchang and Dexing, ranked 14 and 17th in IWI but second and fifth in IWI per capita. These cities urgently need capital restructuring to support long-term sustainability. Research indicates that HC and PC levels have been increasing over time (UNEP, 2019), suggesting that this cluster should manager its NC wisely while adjusting capital composition to meet future needs.

Human capital (HC) and produced capital (PC) dominated cities both faced sustainability challenges, especially those dominated by PC. Due to regional advantage, HC-dominated cities were primarily located in China’s eastern and central-southern regions, with the average HC share of 43.9% in 2021. Among these cities like Huludao and Changning, despite having similar HC shares (50.3% and 44.8%, respectively), their total capital differed significantly, with Huludao’s 119.6 billion yuan nearly three times Changning’s 36.8 billion yuan. The relatively low IWI and IWI per capita in HC dominated cities reflected weaker sustainability and inclusiveness. For instance, Changning and Panzhihua ranked 16th and 11th in IWI and 16th and 12th in IWI per capita, respectively, indicating that HC alone could not compensate for deficiencies in NC and PC, particularly in cities with limited high-quality HC and insufficient investment under growing population pressure. Cities dominated by PC were the smallest in number, with an average PC share of 41.6%, yet an average PC of 359.6 billion yuan slightly above the overall average of 316.1 billion yuan in 2021. Low investment in PC among MRBCs resulted in lower productivity, as these cities were primarily recessionary, further hampering productivity and sustainability. With an average IWI and IWI per capita of 880.1 billion yuan and 737.3 thousand yuan of PC dominated cities, both significantly below the overall averages of 1393.4 billion yuan and 1167.3 thousand yuan, the over-exploitation of resources had left HC and PC insufficient to offset the rapidly depletion of NC. Thus, strategic interventions are essential to foster socio-economic growth in these cities.

Spatial-temporal evolution of inclusive wealth in China’s MRBCs

Between 2011 and 2021, the IWI and IWI per capita improved in most MRBCs, except for Huludao, albeit growth patterns varied significantly (Figs. 2 and 3). On average, the total IWI increased from 1057.4 billion yuan in 2011 to 1393.5 billion yuan in 2021, representing an average annual growth rate of 2.8%. IWI per capita also rose from 949.9 thousand yuan to 1167.3 thousand yuan, growing 2.1% annually, suggesting that the current and past consumption of MRBCs is not compromising the consumption potential of future generations. Tongling experienced the highest overall IWI growth rate of 166.7%, while Ma’anshan led in IWI per capita growth rate of 105.0%. Conversely, Huludao’s IWI and IWI per capita decreased by 21.0% and 18.2%, respectively.

Produced capital (PC) emerged as the primary driver of IWI and IWI per capita growth in MRBCs from 2011 to 2021. On average, PC contributed to increase of 27.5% in IWI and 26.0% in IWI per capita, respectively. This trend underscores the role of PC investment as a critical component of inclusive wealth, particularly in helping poorer areas achieve economic lift-off. Among MRBCs, 13 cities recorded PC growth rates exceeding 14%, with Tongling leading at 74.1%. Although PC growth rate generally exceeded those of human capital (HC), the total amount of PC remained modest in many cities. For instance, Tongling, Ma’anshan, and Xinyu, which had the highest PC pull rates, reported PC levels of 342.6 billion yuan, 699.9 billion yuan, and 374.6 billion yuan in 2021, only slightly above the average of 316.1 billion yuan. This is likely due to major investments in the secondary sector while underfunded persists in the tertiary sector.

In recessionary cities such as Changning and Baiyin, human capital (HC) played a vital role in enhancing inclusive wealth. Specifically, HC increased by 43.6% in Changning (from 114.8 billion yuan to 164.8 billion yuan) and 23.3% in Baiyin (from 372.0 billion yuan to 458.6 billion yuan), contributing 18.5% and 10.0% to IWI growth, and 20.4% and 18.3% to IWI per capita growth, respectively. This demonstrates that HC investment, fostering skills and innovation, are crucial for sustainable development. In contrast, although HC also contributed positively to IWI and IWI per capita in Huludao (9.7% and 11.2%, respectively), the city’s overall IWI and IWI per capita declined by 21.0% and 18.2%. This decline is largely attributed to the depletion of non-renewable capital suggesting that gains in HC and PC may come at the expense of natural capital in resource-dependent cities. More broadly, HC’s impact remains limited across many MRBCs. For instance, Benxi experienced a negative HC contribution to IWI (-4.8%), indicating a pronounced “brain drain” that may severely hinder long term development.

Natural capital (NC) has had a significant yet heterogeneous impact on the IWI and IWI per capita in resource-dependent cities over the past decade. From 2011 to 2021, extensive resource extraction in Huludao led to a dramatic 61.7% decline in NC, causing a loss of 319.0 billion yuan in IWI and 97.9 thousand yuan in IWI per capita. However, strategic reinvestment in PC and HC can offset wealth erosion from NC depletion, supporting a transition to sustainable development. For example, in Huangshi, despite a 36.2% decline in NC, HC, and PC grew by 26.0% and 71.7%, respectively, leading to overall IWI and IWI per capita increase of 26.1% and 25.6%. In cities with newly discovered or exploited mineral resources, NC was a major driver of IWI and IWI per capita growth from 2011 to 2021. For example, in Jinchang and Shaoguan, NC contributed to IWI growth rates of 38.5% and 19.2% and IWI per capita growth rates of 44.7% and 18.8%, surpassing the contributions of HC and PC. In contrast, restricted resources extraction in Altay Prefecture resulted in a slight negative impact on IWI per capita (-1.3%). Moreover, in certain cities, the contribution of NC to IWI and IWI per capita can vary widely; for example, in Benxi and Zhongxiang, the NC pull rate on IWI per capita was nearly 12 times and four times that of IWI, respectively. Both cities experienced substantial population losses of 45,810 and 15,840 over the past decade. The high NC per capita pull rate merely reflects this substantial population decrease.

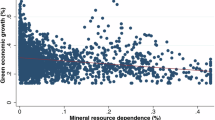

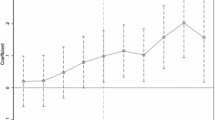

Drivers of spatial-temporal evolutionary differentiation

Renewable natural capital (NCR) emerged as the primary driver of changes in the IWI for MRBCs in both 2011 and 2021, with q values of 0.770 and 0.751, respectively (Fig. 4a). However, its relative influences declined slightly, with a 2.4% reduction in q value over the period. Meanwhile, the weakest driver of the IWI shifted from non-renewable capital (NCN) in 2011 (q value of 0.178) to traditional capital (TC) in 2021 (q value of 0.119), making TC the least explanatory factor for IWI variation among in MRBCs. With the discovery and large-scale exploitation of resources, the explanatory power of NCN surged by 81.4% in q value since 2011. In contrast, reduced investment in TC led to a 62.8% drop in its q value, while intangible capital (IC) increased modestly by 6.0%. From a human capital perspective, MRBCs have undergone notable demographic shifts: education attainment (Edu) increased by (10.7%) due to enhanced attention and investment, while the working age population (P) declined by 5.3%.

a Power of determinant (q value) for each driving factor in MRBCs in 2011 and 2021. b Power of determinant (q value) for each driving factor in grown-up and recessionary cities in 2011 and 2021. c Interaction detection results for drivers in MRBCs in 2011. d Interaction detection results for drivers in MRBCs in 2021.

Understanding the explanatory power of key drivers in IWI changes for both grown-up and recessionary cities is essential for interpreting urban dynamics, especially given the dominance of such city types in MRBCs. NCR and P remained core drivers of IWI in both city types (Fig. 4b); However, both q values declined from 2011 to 2021, particularly in recessionary cities, where the reductions reached 22.0% and 18.3%, respectively. IC, in contract, had a weak impact in both city type in 2011, with q values of 0.016, 0.123, respectively. The influence of various drivers strengthened in grown-up cities from 2011 to 2021, including Edu, TC, IC, and NCN, with IC showing the most substantial increase from a q value of 0.016 to 0.430. Recessionary cities, however, followed a contrasting trend: TC became more influential, with its q value rising from 0.176 to 0.286, while the contribution of NCN declined by 38.8%.

The interaction detection results (Fig. 4c, d) reveal that the combined effect of any two driver interactions on IWI is stronger than that of individual drivers. By 2021, there was a more nonlinear interactions accounted for 52.4% of all interactions, while in 2011, two-factor enhancement interactions were more prevalent. Notably, the overall interaction effect was more pronounced in 2021, particularly the strongest interaction between P and TC. In 2011, the synergy between Edu and other drivers was especially beneficial for sustainability improvement, as NCN moved from a minor to a major influence when interacting with Edu. The interaction of NCN with P and Edu, despite the relatively low independent influence, also proved significant. This highlights the catalytic potential of driver interactions in advancing sustainable development, demonstrating that these synergies can have a substantial, often unexpected impact.

Comparative analysis of sustainability evolution paths and wealth across different city life cycles

The upward trend in inclusive wealth of MRBCs from 2011 to 2021 (Fig. 5a) highlights their steady progress toward achieving the SDGs. The trajectory and the wealth of MRBCs are largely influenced by urban metal resources and associated industries, but each type of city exhibits varying characteristics across life cycle stages. As shown in Fig. 5b, growing cities, rich in bulk metals like iron and copper, have the lowest productivity in NC but the highest in NCN. However, income and capital productivity in growing cities lag behind that of other city types. This lag is primarily due to limited mineral exploration efforts, technological capacity for foundation development, low product value-add in metal-intensive industries, and regional development constraints in the northwest. For instance, in the Altay prefecture, over 70% of copper ore supports primary processing industries such as wire, cable and machinery manufacturing, with only a minimal share of high-value-added products. Additionally, NC continues to degrade in these cities from 2011 to 2021, indicating that long-term sustainability will be jeopardized without increased investment in other forms of capital. Thus, enhancing capital structure, improving capital quality, optimizing resource usage, and converting resource advantages into economic ones are essential priorities.

a Dynamic patterns of capital structure and IWI growth in cities dominated by various capital types from 2011 to 2021. b Bar chart illustrating individual welfare (in Chinese yuan), capital productivity, and resource endowment (in billion yuan) across different life cycle stages dominated by distinct types of capital. Error bars indicate the minimum and maximum values.

Evolutionary processes of grown-up cities over 2011–2021 show progressively reducing their dependence on natural resources, shifting instead towards human capital (HC) driven economies. These cities typically exhibit a favorable capital structure characterized by high individual welfare and capital productivity, especially in cities where HC is dominant. Their transition often involves moving away from traditional steel industries and developing advanced, high-value industries through digitalization and technological innovation. For example, Panzhihua has developed vanadium and titanium industries, with the social workforce in the tertiary sector accounting for 48.2% in 2021, slightly above the national average of 48.0%. Conversely, grown-up cities with a predominant NC focus (e.g., coal and copper-zinc mining cities) tend to rely more heavily on the secondary sector, with an average share of 47.4% in 2021, significantly higher than the national level of 39.4%. These cities often leverage their primary resources to integrate the upstream, midstream, and downstream industry chains, such as materials, chemicals, and energy. Although their IWI and IWI per capita are generally higher than HC dominated cities, they face challenges in capital productivity due to industry entrenchment, which crowds out high-quality human capital and stifles innovative technology. Notably, despite relatively high NC productivity, both HC dominated and NC dependent grown-up cities face risks to sustainability, as high mineral reserves productivity may pose a threat to future development by depleting essential mineral reserves crucial for both ecosystems and human well-being.

Recessionary cities exhibit relatively poor overall sustainability, particularly cities dominated by PC. In these cities, lower capital productivity is often a result of weak endogenous growth dynamics, with average HC and PC productivity rates of 23.3% and 19.4% in 2021, respectively. This low productivity is mainly driven by the income inequality inherent in these cities’ development history, which further hampers the growth of both PC and HC. Recessionary cities also tend to have lower income per capita relative to GDP per capita, reflecting homogeneous economic structure, incomplete industrial chains, and lagging transformation efforts. Converting GDP growth into inclusive wealth growth is crucial for these cities (Almulhim et al., 2024). Historically, recessionary cities focused on increasing PC, albeit at a modest and constrained rate. Although investment in production does foster economic growth, it does not necessarily enhance inclusivity (SDG8), and sustainable consumption and production patterns (SDG12) require significant improvement. Regenerative cities, which have successfully transitioned from recessionary status, have reduced dependence on natural resources, but GDP per capita remains relatively low at 50,804.7 Chinese yuan in 2021. Even among HC dominant regenerative cities, average HC productivity remains relatively low, mainly due to continued investment in resource-intensive industries. Consequently, these cities have the highest NC productivity.

Discussion

Mechanisms driving the development of inclusive wealth

This study employs the IWI to explore the spatial and temporal dynamics of various capital assets and their roles in promoting the high-quality and resilient development of MRBCs. The findings reveal that produced capital (PC) significantly contributes to sustainable development, aligning with existing studies (Zhang et al., 2025; Wu and Xu, 2025). PC refers to the improvement of the infrastructure and manufacturing capacity that increase the capital asset of the economy, further divided into traditional tangible and intangible capital. While traditional capital spurred early growth in MRBCs, intangible capital has emerged as a more influential driver of sustainable development. By improving labor efficiency and innovation capabilities, intangible capital supports the continued growth of these industries, thus reinforcing the city’s sustainable development path (Xue et al., 2022). Furthermore, the expansion of PC can spur investment in human capital (HC), enhancing education and reinforcing the driving force behind innovation growth (Managi et al., 2024). The interaction of PC and HC is more significant in enhancing IWI in MRBCs, indicating that synergies between talent attraction and productivity investment enhance urban inclusiveness (Huo et al., 2024).

The impact of natural capital (NC) on the sustainable development of MRBCs is complex. Resource endowment promoted urban development and accumulated PC and HC in their early stages of development (Dasgupta et al., 2022). However, the undervaluation and over-exploitation of natural resources have led MRBCs into the resource curse mechanism (Yang and Li, 2024). Although human labor and production activities can partially offset the decline in well-being caused by NC depletion, ongoing ecosystem degradation triggers conflicts in health, food security, and biodiversity, resulting in population decline and the gradual obsolescence of technology and capital in MRBCs (Dai et al., 2024). Despite the development of policies aiming to eliminate the chain effects of natural capital destruction through technological progress, achieving this goal remains challenging (Huo et al., 2024). Notably, increased investment in renewable capital can significantly reduce dependence on fossil fuels and lower greenhouse gas emissions, bringing multiple benefits to the sustainable development of MRBCs (Qing et al., 2022), which is consistent with our findings. The growing influence of renewable capital in driving IWI growth in MRBCs lays the foundation for the sustainable transformation of these cities.

The sustained and stable policies and governance mechanisms under the strong leadership of the central government are key to promoting the sustainable development of MRBCs (Feng et al., 2024). The State Council issued the “Sustainable Development Plan for Resource based Cities (2013–2020)” in 2013 (The State Council, 2013), which defined the strategic goals and policy directions for urban transformation, marked a strong political commitment and provided a systematic roadmap, and successively issued a series of policies to support sustainable transformation (Supplementary materials 2). Green, low-carbon, and SDGs are the shared vision for RBCs worldwide, especially the proposal of the global low-carbon economy. It is worth noting that while the “dual carbon goals” pose challenges to MRBCs in terms of metal industry production and processing, they also present greater opportunities. Stimulating low-carbon technological advancement, along with integrating innovative technologies into the industrial system of MRBCs, can attract high-quality human capital. In turn, the knowledge spillover from HC accumulation provides sustained momentum for technological innovation (Yang et al., 2023b).

Discussion on policy implications

Global demand for metal resource is expected to remain high, given their role in modern industries (Owen et al., 2023). Ensuring stable resource supply of mineral resources necessitates enhancing MRBCs’ sustainable suitability. Additionally, global carbon reduction goals present new challenges to energy-intensive industries in MRBCs, especially in the context of the continuous increase in dependence on key metals for new energy technologies, requiring policymakers to bolster support through industrial, technological, and talent development, along with greater investment in innovation (Zhang et al., 2022b). By objectively measuring the welfare and evolution of MRBCs, it can not only support adaptive development decisions at the current stage, but also provide policy guidance for sustainable transition practices in different life cycles in the future.

As the growth model of growing cities continues to be based on resource investments (Lu et al., 2025), policies should focus on improving efficiency and productivity through industrial chain extension and technology upgrades, especially for metals critical to the clean energy transition, such as aluminum and copper. This approach would allow strategic balancing in the international metal resource market and support high-quality development in the global context, avoiding the dilemma of “value chain lock-in effect” (Mao et al., 2021). Specifically, it is recommended that growing cities learn from the successful experiences of cities at different stages and plan ahead. For example, the full industrial chain layout and advanced recycling technologies in the metal circular economy models of Nordic countries have enabled them to become frontrunners in the efficient utilization of metal resources (Petelin, 2025). Furthermore, enhanced research and development investment in MRBCs is critical for translating technological progress into sustainable growth. On one hand, dedicated research funding should be allocated across the industrial chain of metal smelting, deep processing, and remanufacturing. On the other hand, R&D strategies should focus on green metallurgy and energy-saving technologies. For instance, the innovation-driven city of Taiyuan has achieved a remarkably high growth rate in both the IWI and IWI per capita (Cheng et al., 2022).

Notably, R&D investment in grown-up cities not only boosts resource extraction technology but also drives innovation in downstream industries, promoting economic diversification and long-term growth. Most of the grown-up MRBCs in this study have gradually shifted towards a tertiary driven economic model, which differs significantly from grown-up cities in coal RBCs (Hou et al., 2020) and RBCs (Wang et al., 2022). In fact, other studies indirectly support our conclusion. For example, MRBCs exhibit better dynamic adaptability in industrial factor allocation and green transformation performance, especially highlighting the key role of labor mobility in upgrading the national value chain (Lu et al., 2025). The injection of new industries and clean energy can significantly improve the spatial resilience of grown-up resource-dependent MRBCs (Zhang et al., 2025).

For resource-scarce or recessionary regions, cities face the most significant transformation challenges. Comprehensive actions are needed to improve labor skills and production capacity while protecting natural resources. As demonstrated in the United Nations Environment Program (2023), natural capital losses can be partially compensated through the accumulation of other capital types. This emphasizes the importance of human and produced capital for the growth of well-being (Managi et al., 2024). Sensitivity analysis further confirms that the accumulation of human capital through education investment is more sensitive to the IWI changes in such cities. Simultaneously, the governments should actively promote the circular economy model, focusing on the reuse and recycling of high-recyclability metals like steel and aluminum to foster “urban minerals”. Such actions would help stabilize local economies and secure employment. For example, active metal recycling models have been implemented worldwide in the construction industry and power systems (Halkos et al., 2024; van Oorschot et al., 2022). Such actions not only help stabilize metal supply and local economy, but also create new green employment opportunities. Based on the abundance and recyclability of waste metal resources in such cities, the government should take a leading role and promote industrial collaboration to build an urban circular economy on the foundation of the tradition of the mineral industry chain, with the aim of fostering “urban minerals”.

Regenerative cities are often at the crossroads of decline and revival, and policy and financial support are essential for the growth of alternative industries and urban services. Particularly for resource-dependent cities, such initiatives can help buffer social unrest and create institutional space for urban transformation (Chen, 2023). Furthermore, technological innovation and fostering innovation hubs are vital for sustainability, as digitization can improve energy efficiency and provide sustainable alternative pathways (Maria et al., 2021). The integration of the digital economy with metallurgy, using AI and big data for predictive maintenance and resource optimization, will enhance MRBCs resilience globally. Digital technology can drive “digital green transformation” and “intelligent low-carbon transition” in mining cities (Luo et al., 2024). The regeneration practice of coal RBCs shows that the effectiveness of transformation often depends on the introduction of emerging technologies and the reconstruction of industrial structure (Yang et al., 2023b). Learning from the economic innovation models of non-RBCs helps mitigate the volatility associated with cyclical energy price fluctuations and promotes comprehensive and sustainable transformation.

Limitations and future work

This study employs an innovative and improved IWI accounting framework to assess the sustainability performance, capital composition evolution, and spatial drivers of China’s MRBCs, providing a multi-dimensional framework for policymakers to assess and address the unique sustainability challenges facing MRBCs. However, there are valid limitations in exploring stable patterns or laws at different stages of the urban development lifecycle due to the limited sample size of MRBCs in China. Despite the sample size limitations, our findings represent initial exploratory insights rather than definitive conclusions, positioning this study as the foundation for future research. Moreover, the classification of the lifecycle stages of RBCs is highly endogenous, and their dynamic evolution mechanisms are complex and variable (Wu and Bai, 2022). The current life cycle stages and future trajectories can be explored in future research, especially for grown-up and recessionary RBCs. Furthermore, to conduct a comprehensive assessment of economies, future research could consider the synergies and physical thresholds between different capitals, and incorporate the effects of carbon emissions and the feedback mechanisms of climate change.

Conclusions

Achieving sustainable development in mining cities is a critical global goal, requiring shifts in human settlement, socio-economic structures, and ecological governance. This study examines the sustainable development performance, capital composition changes of China’s MRBCs using an enhanced IWI framework. Using the GeoDetector tool, we identify the key drivers and mechanisms that impact sustainability, aiming to provide policymakers with actionable insights to support balanced development across economic, environmental, and social dimensions. Key findings are as follows:

(1) MRBCs exhibit spatial heterogeneity in inclusive wealth and capital composition. Most MRBCs are dominated by natural capital, driven by regional differences in resource endowments driving wealth disparities. The east and south-central regions have human capital dominated cities, though IWI per capita remains low due to rapid population growth. Low production capital investment also limits MRBCs’ productive capacity, reflecting broader structural challenges related to regional inequality and labor dynamics.

(2) Variations in the spatial-temporal evolution of inclusive wealth in MRBCs. Over the past decade, both IWI and IWI per capita of MRBCs have generally increased. However, the accumulation remains uneven. Produced capital is the primary driver of inclusive wealth growth but remains limited in most cities. MRBCs driven by human capital face challenges such as low attraction and retention rates due to brain drain, while natural capital plays a complex role, influencing sustainability both positively and negatively in resource-dependent cities.

(3) The inclusive wealth growth is influenced by a complex interplay of multiple factors. Renewable natural capital, intangible capital, non-renewable natural capital, and the working age population significantly impact IWI. However, traditional capital and education attainment have weaker effects. The interplay of multiple factors often has nonlinear or dual-factor enhancement effects on IWI, highlighting the need for coordinated strategies in sustainable development planning.

(4) The evolution of MRBCs at different life cycles reveals distinct patterns. Growing cities continue to experience declines in natural capital, while regenerative cities experience gradual increases in human capital. Recessionary cities show slow growth in produced capital, posing sustainability concerns. The predominance of recessionary cities underscores the urgency for transformative measures. These different trajectories reflect the necessity of differentiated governance strategies based on lifecycle and social inclusion.

In conclusion, this study reveals the key roles of human, social production and institutional factors in supporting sustainable MRBCs development by understanding the spatial and temporal dynamics of capital assets and their interactions. Our findings deepen the understanding of the development mechanisms and transformation paths of MRBCs at different stages of their lifecycle. Policymakers can create targeted interventions to drive high-quality, resilient development in RBCs.

Data availability

All data used in this study is reported in the supplemental information section or obtained from the sources cited in the study. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this article is available from the lead contact on request.

References

Akcil A, Sun Z, Panda S (2020) COVID-19 disruptions to tech-metals supply are a wake-up call. Nature 587:365–367

Almulhim AI, Sharifi A, Aina YA et al. (2024) Charting sustainable urban development through a systematic review of SDG11 research. Nat. Cities 1:677–685

Arrow K, Dasgupta P, Goulder L et al. (2004) Are we consuming too much? J. Econ. Perspect. 18:147–172

Chen P (2023) Curse or blessing? The relationship between sustainable development plans for resource cities and corporate sustainability-evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 341:117988

Cheng D, Xue Q, Hubacek K et al. (2022) Inclusive wealth index measuring sustainable development potentials for Chinese cities. Glob. Environ. Change 72:102417

China Non-Ferrous Metals Industry Association (2009) 60 years of nonferrous metals industry in new China. Central south university press, Changsha

Dai Y, Ding Y, Fu S et al. (2024) Analyzing the impact of natural capital on socio-economic objectives under the framework of sustainable development goals. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 104:107322

Dasgupta P, Duraiappah A, Managi S et al. (2015) How to measure sustainable progress. Science 350:748–748

Dasgupta P, Managi S, Kumar P (2022) The inclusive wealth index and sustainable development goals. Sustain Sci. 17:899–903

Engelbrecht HJ (2016) Comprehensive versus inclusive wealth accounting and the assessment of sustainable development: an empirical comparison. Ecol. Econ. 129:12–20

Fan F, Zhang X (2021) Transformation effect of resource-based cities based on PSM-DID model: an empirical analysis from China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 91:106648

Fan JL, Li K, Zhang X et al. (2022) Measuring sustainability: development and application of the inclusive wealth index in China. Ecol. Econ. 195:107357

Feng Y, Gao Y, Pan Y (2024) Identifying the antecedents for the green transformation of resource-exhausted cities in China. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:1387

Goodchild MF, Haining RP (2004) GIS and spatial data analysis: converging perspectives. Pap. Reg. Sci. 83:363–385

Halkos GE, de Alba JM, Aslanidis PSC (2024) An eco-efficient European metal industry transition towards circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 479:144063

Hamilton K, Clemens M (1999) Genuine savings rates in developing countries. World Bank Econ. Rev. 13:333–356

Hou YL, Long RY, Zhang LL et al. (2020) Dynamic analysis of the sustainable development capability of coal cities. Resour. Policy 66:101607

Huo D, Lv X, Bukhari AAA et al. (2024) Transformative pathways to sustainable wealth: do natural and human capital really matter? J. Clean. Prod. 469:143199

Ikeda S, Tamaki T, Nakamura H et al. (2017) Inclusive wealth of regions: the case of Japan. Sustain. Sci. 12:991–1006

Islam M, Managi S (2022) Valuation of nature’s contribution in Ladakh, India: an inclusive wealth method. Sustain. Sci. 17:905–918

Jiang H, Sun Z, Guo H et al. (2021) An assessment of urbanization sustainability in China between 1990 and 2015 using land use efficiency indicators. npj Urban Sustain. 1:1–13

Lèbre É, Stringer M, Svobodova K et al. (2020) The social and environmental complexities of extracting energy transition metals. Nat. Commun. 11:4823

Li B, Han Y, Wang C et al. (2022) Did civilized city policy improve energy efficiency of resource-based cities? Prefecture-level evidence from China. Energy Policy 167:113081

Li H (2023) China human capital report 2023. Central University of Finance and Economics. https://humancapital.cufe.edu.cn/info/1103/1529.htm. Accessed 17 Nov 2024

Li W, Cai Z, Jin L (2024) Urban green land use efficiency of resource-based cities in China: multidimensional measurements, spatial-temporal changes, and driving factors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 104:105299

Lu S, Li J, Zhang W et al. (2025) How can the “resource curse” be broken? Transition factor flows, the urban life cycle and value chain upgrades in resource-based cities. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 12:218

Luo H, Yang B, Liu Z et al. (2024) The bright and dark sides: unpacking the effect of digital economy on resource curse. J. Clean. Prod. 485:144351

Macroeconomic Research Group of National Planning Commission (2002) The definition and classification of resource-based cities in China. Macroeconomics 11:37–39

Managi S, Chen S, Kumar P et al. (2024) Sustainable matrix beyond GDP: Investment for inclusive growth. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:185

Mao WX, Wang WP, Sun HF et al. (2021) Urban industrial transformation patterns under natural resource dependence: a rule mining technique. Energy Policy 156:112383

Maria EM, Ram A, Heyker L et al. (2021) Digitalization to achieve sustainable development goals: steps towards a smart green planet. Sci. Total Environ. 794:148539

Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (2024) Operation of nonferrous metals industry in 2023. https://wap.miit.gov.cn/jgsj/ycls/gzdt/art/2024/art_a1c0cbd9426f40a9b786fa7829816b75.html. Accessed 17 Nov 2024

National Development and Reform Commission (NRDC), Ministry of Finance (MOF), Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) (2021) Implementation plan for the 14th five-year plan for promoting high-quality development of resource-based regions. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-11/14/content_5650830.htm. Accessed 17 Nov 2024

Owen JR, Kemp D, Lechner AM et al. (2023) Energy transition minerals and their intersection with land-connected peoples. Nat. Sustain. 6:203–211

Petelin E (2025) Effects of resource security concerns on Nordic countries’ approach to the circular economy of metals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 55:420–433

Qing Y, Guo W, Cao G et al. (2022) Environmental dilemma and sustainable development of resource-based cities: a case study from northeast China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:998754

Sharifi A, Allam Z, Bibri SE et al. (2024) Smart cities and sustainable development goals (SDGs): a systematic literature review of co-benefits and trade-offs. Cities 146:104659

Song Y, Yeung G, Zhu D et al. (2022) Efficiency of urban land use in China’s resource-based cities, 2000-2018. Land Use Policy 115:106009

Sovacool BK, Ali SH, Bazilian M et al. (2020) Sustainable minerals and metals for a low-carbon future. Science 367(6473):30–33

Sun Y, Wang Y, Zhou X et al. (2023) Are shrinking populations stifling urban resilience? Evidence from 111 resource-based cities in China. Cities 141:104458

Svobodova K, Owen JR, Kemp D et al. (2022) Decarbonization, population disruption and resource inventories in the global energy transition. Nat. Commun. 13:7674

The State Council (2013) The plan for the sustainable development of resource-based cities in China (2013-2020). http://www.gov.cn/zfwj/2013-12/03/content_2540070.htm. Accessed 17 Nov 2024

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2019) Inclusive wealth report 2018: Measuring sustainability and well-being. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/27597. Accessed 17 Nov 2024

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2023) Inclusive wealth report 2023: Measuring sustainability and equity. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/43131. Accessed 17 Nov 2024

United Nations University International Human Dimensions Programme (UNU-IHDP) (2012) Inclusive wealth report 2012: Measuring progress toward sustainability. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/32228. Accessed 17 Nov 2024

van Oorschot J, Sprecher B, Roelofs B et al. (2022) Towards a low-carbon and circular economy: scenarios for metal stocks and flows in the Dutch electricity system. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 178:106105

Wan L, Ye X, Lee J et al. (2015) Effects of urbanization on ecosystem service values in a mineral resource-based city. Habitat Int. 46:54–63

Wang D, Huang Z, Wang Y et al. (2021) Ecological security of mineral resource-based cities in China: multidimensional measurements, spatiotemporal evolution, and comparisons of classifications. Ecol. Indic. 132:108269

Wang JF, Li XH, Christakos G et al. (2010) Geographical detectors‐based health risk assessment and its application in the neural tube defects study of the Heshun region, China. Int J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 24:107–127

Wang Y (2024) Assessment of sustainable development capacity of resource-based cities based on ecological carrying capacity-taking Zigong city, Sichuan province, China as an example. Heliyon 10:e33773

Wang Y, Chen H, Long R et al. (2022) Has the sustainable development planning policy promoted the green transformation in China’s resource-based cities? Resour. Conserv. Recy. 180:106181

Wang Z, Fu H, Zhou L (2023) Multiple urban resilience evaluation of resource-based cities’ sustainable transformation effect. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 191:106912

Wiedmann T, Allen C (2021) City footprints and SDGs provide untapped potential for assessing city sustainability. Nat. Commun. 12:3758

Wu B, Xu Y (2025) Towards sustainable development: can industrial collaborative agglomeration become an accelerator for green and low-carbon transformation of resource-based cities in China? J. Environ. Manag. 381:125199

Wu J, Bai Z (2022) Spatial and temporal changes of the ecological footprint of China’s resource-based cities in the process of urbanization. Resour. Policy 75:102491

Xiao H, Xu Z, Ren J et al. (2022) Navigating Chinese cities to achieve sustainable development goals by 2030. Innovation 3:100288

Xie G, Lu C, Leng Y et al. (2003) Ecological assets valuation of the Tibetan Plateau. J. Nat. Resour. 18(02):189–196

Xie G, Zhang C, Zhang L et al. (2015) Improvement of the evaluation method for ecosystem service value based on per unit area. J. Nat. Resour. 30(08):1243–1254

Xue Q, Cheng D, Li Y et al. (2022) Sustainable development pathways for Chinese cities: an assessment of the advanced inclusive wealth index. Earth’s Future 10:e2022EF002695

Yang J, Chen F, Wang Y et al. (2023a) Performance evaluation of ecological transformation of mineral resource-based cities: from the perspective of stage division. Ecol. Indic. 154:110540

Yang Y, Cheng D, Zhang B et al. (2023b) Coal resource-based cities at the crossroads: towards a sustainable urban future. Cities 140:104424

Yang Z, Li M (2024) Escaping the resource curse: does resource dependence reduction mitigate income inequality? Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:1697

Ye Z (2010) The estimation of China’s provincial capital stock. Stat. Res. 12:65–71

Zafar MW, Zaidi SAH, Khan NR et al. (2019) The impact of natural resources, human capital, and foreign direct investment on the ecological footprint: the case of the United States. Resour. Policy 63:101428

Zhang H, Sun X, Bi C et al. (2022a) Can sustainable development policy reduce carbon emissions? Empirical evidence from resource-based cities in China. Sci. Total Environ. 838:156341

Zhang J, Wu G, Zhang J (2004) Estimates of China’s inter-provincial physical capital stock: 1952-2000. Econ. Res. 10:35–44

Zhang Y, Alharthi M, Ali SA et al. (2022b) The eco-innovative technologies, human capital, and energy pricing: evidence of sustainable energy transition in developed economies. Appl. Energy 325:119729

Zhang Y, Zhang J, Randal E et al. (2025) Multi-scale quantification and optimization of spatial resilience under industrial activities: a case study of resource-based cities in China. Sust. Cities Soc. 128:106487

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 72088101 and 72394405), the Environmental Defense Fund, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant no. 20720231063).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SX: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Investigation, Writing-original draft. KY: Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Validation. BZ: Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing, Supervision. CG: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xi, S., Yan, K., Zhang, B. et al. Revealing the sustainability transitions in China’s metal resource-based cities. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1717 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05980-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05980-9