Abstract

While remaining at and returning to work are clearly complex issues in multiple sclerosis (MS), in which many aspects (physical, psychological and relational, as well as personal resources such as coping strategies) can play a key role, there is still room for potential interventions. This study aimed to identify and describe profiles of workers with MS (wwMS), considering specific work-related domains, namely, work-related difficulties, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and coping strategies. A cross-sectional online survey of wwMS was conducted in Italy. Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using the Ward method followed by k-means cluster analysis. In total, 209 workers with MS were included in the analysis. We identified four profiles: profile 1 had low work difficulties, low depressive symptoms and mild anxiety, with a moderate tendency to use ‘problem focus’ and ‘positive attitude’ and a mild tendency to use ‘social support’ as coping strategies (n = 82, 39.2%); profile 2 had low-to-mild work difficulties, mild anxiety and low depressive symptoms, with a high tendency to use ‘positive attitude’ and ‘religion’, moderate use of ‘problem focus’ and ‘social support’, and mild use of ‘denial’ (n = 38, 18.7%); profile 3 had low-to-mild work difficulties, moderate anxiety and depressive symptoms, with a mild tendency to use ‘problem focus’, ‘positive attitude’, ‘religion’, ‘social support’ and ‘denial’ as coping strategies (n = 50, 23.9%); profile 4 had mild-to-moderate work difficulties, moderate anxiety and depressive symptoms, with a moderate tendency to use ‘problem focus’ and ‘positive attitude’, and a mild tendency to use ‘social support’ and ‘denial’ as coping strategies (n = 39, 18.7%). Identifying profiles of workers with a chronic and progressive disability such as MS may lead to the development of personalised interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Work is central to the identity, confidence and self-esteem of people with multiple sclerosis (pwMS) as it gives them dignity, a sense of purpose and a chance to fully participate in society (Miller and Dishon 2006). PwMS are less likely to be employed than the general population. In 2022, the unemployment rate among pwMS was 35.6%, versus global rates ranging from 4.80 to 6.47% (according to World Bank Data) (Vitturi et al. 2022).

Multiple sclerosis (MS) can cause a wide range of neurological symptoms affecting several functional systems and resulting in different levels of disability (Johansson et al. 2007; Wong et al. 2021). Despite this, in the context of research on MS and employment, MS-related disability is often explored in relation to a single domain (e.g., physical or cognitive). MS symptoms often occur concurrently, and multiple concurrent symptoms, as opposed to a single symptom, have been shown to have a greater impact on certain consequences of the disease (Shahrbanian et al. 2015). People with multiple coexisting symptoms may require significantly different services, accommodations or interventions to help them continue or resume working. For this reason, identifying the main work-related difficulties encountered by pwMS is a crucial step in the development of tailored interventions designed to maximise their ability to handle the duties and demands associated with their work. Some studies seem to suggest that physical disability is more impactful than psychological variables on work issues. However, increased emotional distress has been shown, in pwMS, to contribute to the decision to leave the workforce (Beier et al. 2019). As reported in a recent study, symptoms of depression and anxiety are important contributors to occupational difficulties (Ponzio et al. 2024). These results confirm that, in general, depression is associated with reduced work participation, in the same way as common mental disorders lead to impaired work performance (Ivandic et al. 2017).

Although physical and cognitive symptoms and the unpredictability of relapses may all play a role, job loss in pwMS is more likely to be attributable to a complex interaction between disease-related and contextual factors, the latter including the working environment and employer attitudes. This interaction is linked to the concept of work instability, a term referring to a mismatch between the demands of a job and the individual’s capacity to meet them. Workers with MS (wwMS) can have difficulty communicating their needs effectively, dealing with discomfort, overcoming stigma and discrimination, and meeting expectations in terms of productivity. They can also encounter obstacles when seeking to make adjustments to their working style and adapt their workstation (Vitturi et al. 2022; Vitturi et al. 2023).

Personal resources play an important role in increasing the ability to continue working, as shown by research into coping styles and employment status in pwMS. Avoidant coping styles, such as behavioural disengagement and denial, were found to be associated with unemployed status or a shorter time to unemployment. Instead, employed pwMS tended to adopt more problem-focused coping strategies (Dorstyn et al. 2019).

Research in healthy workers suggests that active coping improves the ability to work, while avoidant coping does the opposite (van de Vijfeijke et al. 2013). van Egmond and co-workers reported that the use of emotion-oriented and avoidance-oriented coping strategies was related to greater difficulties at work in pwMS (van Egmond et al. 2022). Similarly, van der Hiele et al. found emotion- and task-oriented coping strategies to be associated with negative work events (van der Hiele et al. 2016).

Another aspect of interest, relatively poorly studied in wwMS, is well-being at work in terms of work engagement. Work engagement has been defined as a positive and fulfilling cognitive-affective state of mind at work characterised by vigour, dedication and absorption (Schaufeli et al. 2002). Previous studies have shown that work engagement is negatively related to the intention to leave work (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004) and positively related to career success and job performance (Salanova et al. 2005), and to reduced recourse to early retirement due to disabilities (Hakanen et al. 2006) .

While remaining at and returning to work are clearly complex issues in MS, in which many aspects (physical, psychological, relational, and also personal resources such as coping strategies) can play a key role, there is still room for potential interventions.

Tailoring job demands to an individual’s capacity has been found to improve work and health outcomes for people with long-term neurological conditions (BSRM British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine 2010). Therefore, it is crucial, in worker assessment, to analyse multiple aspects and consider the profiles they may give rise to.

The conceptualisation and definition of specific profiles of wwMS may be a useful means of characterising occupational status, in turn useful for guiding vocational rehabilitation interventions.

With the aim of addressing these knowledge gaps, this explorative study set out to identify distinct profiles of wwMS by considering specific work-related domains, namely work-related difficulties, mood disorders and personal resources (coping strategies). The profiles identified were then examined to establish whether they differed from each other in terms of sociodemographic, clinical and work-related characteristics. This is one of the first attempts to apply clustering methods in this context, to advance personalized support and interventions to sustain employment and well-being in this population.

Methods

Design and sample

A cross-sectional study (online survey) was carried out in Italy during 2021–2022 in order to collect information about respondents’ work-related difficulties, coping strategies and mood disorders. Respondents were recruited among pwMS in contact with the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Society (AISM) through its social media channels. We disseminated the survey through the Survey Monkey® platform, a secure web application for building and managing online databases. The survey took on average 15–20 min to complete. To be eligible, participants had to be: 1) aged ≥18 years; 2) diagnosed with MS; 3) currently employed.

After reading information about the study and what participation would entail, individuals consented to participate by clicking on the option ‘proceed with the questionnaire’. The study was approved by the Liguria Regional Ethics Committee, Italy (P.R. 221/2021-DB id 11297; 19/07/2021).

Variables used in clustering

The variables included in the cluster-building process were based on available literature regarding psychological aspects related to work-related difficulties in individuals with multiple sclerosis.

They covered different work-related domains, namely difficulties (physical, mental, company-related) linked to mood disorders (anxiety and depression), and internal resources (coping strategies). Variables not directly linked to psychological functioning in the workplace were intentionally excluded to maintain coherence with our theoretical framework and research aims. In this way, it was possible to address and analyse the complex issue of job maintenance/resumption of work as a multifactorial problem (see Fig. 1): MS impacts on work-related difficulties and mood disorders (depression and anxiety); work-related difficulties and mood disorders are potentially correlated with each other; coping strategies potentially play a facilitator role.

Measures

Sociodemographic, clinical and work-related data were collected from participants by means of various validated scales, as described below.

Work-related difficulties were measured using the Multiple Sclerosis Questionnaire for Job Difficulties (MSQ-Job) (Raggi et al. 2015). The MSQ-Job is made up of 42 items forming six subscales and an overall scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate more severe problems with work-related activities. The questionnaire is intended to capture the individual’s perceived difficulties with work-related tasks and includes both MS-related (physical and mental) and company-related difficulties. Two subscales of the MSQ-Job, namely ‘Tactile perception and fine movement’ and ‘Movement and fatigue-related body functions’, address areas of physical health that can affect work-related activities. A further two subscales address issues related to mental health and relational aspects, respectively ‘Fatigue-related mental functions and symptoms’ and ‘Psychological and relational aspects’. The last two subscales, ‘Time and organisational flexibility in the workplace’ and ‘Company’s attitudes and policies’, address difficulties due to features of the workplace as perceived by the person with MS. A score higher than 15.8 is indicative of the presence of severe work-related difficulties (Schiavolin et al. 2016).

Mood disorders were tested using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a well-established instrument for identifying anxiety and depressive symptoms (Zigmond and Snaith 1983). The HADS has been validated in Italian and for use in MS (Costantini et al. 1999; Honarmand and Feinstein 2009). It has seven questions dealing with anxiety and seven focusing on depression. For each question, subjects choose one response from the four provided and each answer corresponds to a score of between 0 and 3. Possible total scores range from 0 to 21 for both anxiety and depression.

Coping strategies were tested using Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced - Nuova Versione Italiana (COPE-NVI). The overall score on this instrument can be considered a useful and psychometrically valid tool for measuring coping styles in the Italian context (Sica et al. 2008). This 25-item scale is a reduced version of the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) developed by Carver et al. (Carver et al. 1989). The selected subscales measure five dimensions: social support, avoidance strategies, positive attitude, problem solving and turning to religion. Subjects reply to each statement by indicating the frequency with which they use the various coping strategies, choosing from four options: 1- I don’t usually do this, 2- I sometimes do this, 3- I frequently do this, 4- I almost always do this. For each dimension, a total score is calculated as the sum of the values given by the subject.

Among the covariates analysed in this study, work engagement was explored by collecting information using the nine‐item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9), a self‐report questionnaire. Work engagement was defined as a positive and fulfilling work-related psychological state characterised by the following dimensions: vigour (e.g., ‘At work, I feel bursting with energy’), dedication (‘I am enthusiastic about my job’) and absorption (‘I feel happy when I am working intensely’) (Schaufeli et al. 2006). Each of the corresponding subscales consists of three items which are rated on a 7‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘never’) to 6 (‘always’). The UWES‐9 total score was the sum of these three subscales. The Italian version of the UWES‐9 has confirmed validity and reliability (Balducci et al. 2010).

Statistical analysis

Uniform cluster analysis methodology was applied using a two-step approach. In the first step, hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using Ward’s method. The Duda and Hart index was used to determine the number of groups into which the participants should be divided (Duda and Hart 1973). This estimate was pre-specified through a k-means cluster analysis that was used as the principal clustering technique (Ball and Hall 1967). To run the analysis, we excluded records with missing values, adopting a conservative approach made possible by the large sample size of our dataset. Avoiding interpolation methods eliminates the possibility of bias introduction and maintains the original data’s integrity. All measurements were standardised using min-max rescaling for continuous variables. We assessed the importance of each variable in the clustering process by using an ensemble of 300 classification trees. We applied k-fold cross-validation (k = 10) and extracted the average importance of each feature over the course of these ten iterations. During the description of the cluster, to facilitate interpretation of the values, we classified them according to the percentile distribution of the rescaled scores, as follows: ≤25th percentile = low; 26th–50th percentile = mild; 51st–75th percentile = moderate; ≥76th percentile = high. The differences between profiles based on sociodemographic, clinical and work-related information were analysed using the χ2-test for categorical variables or the Kruskal–Wallis test for numerical ones. Significance was set at α = 0.05 and Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons were applied after statistically significant Kruskal–Wallis tests. The analyses were conducted with Stata Version 17 (Stata-Corp, College Station, TX) and MATLAB (version 9.14.0 (R2023a) Update 4).

Results

A total of 244 participants, all currently employed, filled out the questionnaire. Of these, 35 (14.3%) were excluded because they returned incomplete questionnaires. The analysis thus concerned 209 wwMS. The characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1.

Figure 2 shows the hierarchy of features according to their respective weight during clustering. The results suggest that subgroup identification was most strongly correlated with the ‘turning to religion’ variable.

The cluster solution distinguished between four specific and predominant subgroups corresponding to meaningfully interpretable clusters of wwMS that differed from each other in terms of characteristics that included work-related difficulties, mood disorders and personal resources (Fig. 3 and Table 2).

Each plot shows the mean values for work-related domains in the profile in question. The range of each coordinate is rescaled to the interval [0 1]. The values were classified according to the percentile distribution of the rescaled scores as follows: ≤25th percentile = low; 26th–50th percentile = mild; 51th–75th percentile = moderate; ≥76th percentile = high.

Profile 1 included 39.2% of the sample; n = 82. This cluster consisted of wwMS with low work difficulties, low depressive symptoms and mild anxiety. They showed a moderate tendency to use ‘problem focus’ and ‘positive attitude’ and a mild tendency to use ‘social support’ as coping strategies.

Profile 2 included 18.2% of the participants; n = 38. This cluster was composed of wwMS with low-to-mild work difficulties, low depressive symptoms and mild anxiety. They showed a high tendency to use ‘turning to religion’ and ‘positive attitude’ as coping strategies, moderate use of ‘problem focus’ and ‘social support’, and mild use of ‘denial’.

Profile 3 included 23.9% of the sample; n = 50. Individuals with phenotype 3 had low-to-mild work difficulties, and moderate anxiety and depressive symptoms. They showed a mild tendency to use ‘problem focus’, ‘positive attitude’, ‘religion’, ‘social support’ and ‘denial’ as coping strategies.

Profile 4 included 18.7% of the participants; n = 39. This cluster comprised wwMS with mild-to-moderate work difficulties, moderate anxiety and depressive symptoms. They showed a moderate tendency to use ‘problem focus’ and ‘positive attitude’ and a mild tendency to use ‘social support’ and ‘denial’ as coping strategies.

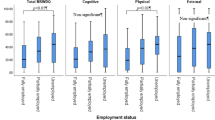

Further analysis of the sociodemographic, clinical and work-related characteristics of the four profiles revealed that they were similar to each other in terms of sociodemographic and work-related features. Profile 1 showed the lowest disease duration (11.4 years) and level of disability, as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) (EDSS = 2.3), and a high level of work engagement; Profile 2 showed a relatively low EDSS score (3.0) and the highest level of work engagement; Profile 3 had the highest disease duration (14.4 years), quite a high EDSS score (3.5), and quite low work engagement; finally, Profile 4 had the highest level of disability (EDSS = 3.9) and the lowest level of work engagement. Table 3 shows the complete results.

Discussion

In the present study cluster analysis was used to identify predominant profiles of wwMS with a view to the development of targeted vocational rehabilitation interventions designed to help them continue working and work better. Clinical phenotyping has significantly contributed to the understanding of MS and to the development of personalized treatments. Symptom clusters, such as the co-occurrence of cognitive, motor, and emotional difficulties, are frequent in PwMS and can profoundly impact quality of life. Previous studies have successfully identified cognitive phenotypes in MS using clustering methods, thus demonstrating the relevance of person-centred approaches (Leavitt et al. 2018; De Meo et al. 2021; Podda et al. 2021, 2024). The relationship between MS and employment has often been examined by considering MS-related obstacles as a single domain, an approach that results in heterogeneous groups of individuals with different profiles of difficulties. Since the various symptoms of MS often occur concurrently, applying a different approach, considering different work-related domains, could help in identifying a taxonomy that recognises distinct and predominant profiles of wwMS, given the complexity of work-related challenges in MS, where physical symptoms, emotional well-being, interpersonal dynamics, and personal coping resources are strongly interrelated. To our knowledge, this is the first study aimed to define distinct profiles of pwMS in a working-age population based on various work-related domains, namely, work-related difficulties, coping strategies and psychological aspects. The identification of distinct profiles among workers with MS offers valuable implications for practice. While individual assessments of anxiety, depression, coping strategies, and work-related difficulties are informative, cluster analysis provides a more integrative and person-centred perspective. By highlighting how these variables co-occur in real-world patterns, the resulting profiles allow practitioners to recognize common constellations of functioning and distress, thereby supporting more efficient and targeted interventions.

The approach adopted was motivated by a systematic review suggesting that co-occurrence of physical, cognitive, behavioural and sensory impairment is related to job retention (Wong et al. 2021). The present study has important strengths, including the nationally representative sample, and the fact that the latter represents the full range of clinical characteristics (i.e., different disability levels) shown by pwMS.

The participants reported difficulties in carrying out work activities, with 69.4% of the sample experiencing ‘critical situations’ with regard to work performance. This percentage increases across the profiles from 41.5% for phenotype 1–100% for phenotype 4.

Overall, we observed a linear trend across the four profiles, consisting of progressively increasing levels of work-related difficulties, anxiety and depression. This observation corroborates the findings of previous studies that showed a positive association between work-related difficulties and depressive and anxiety symptoms (van Egmond et al. 2021; van Egmond et al. 2022). With regard to coping strategies, different coping patterns were observed across the clusters.

The first profile was found to be comprised of subjects who were less impaired by their condition than the other wwMS. In this subtype, albeit accounting for ~40% of the sample reporting a critical situation (based on the MSQ-Job cut-off value) requiring the attention of and possible intervention by the employer, work-related difficulties were low overall. The highest level of work-related difficulties reported by these individuals (nevertheless within the 25th percentile and therefore low) concerned ‘Movement and fatigue-related body functions’. These findings agree with those of another study in which physical problems related to impaired upper and lower limb function, or less visible difficulties such as sensory disorders or fatigue-related body functions, were prominent even in less impaired subjects. Fatigue is likely to affect somatosensory perception and involve perturbation of the body schema. Pardini and colleagues (2013) found an unexpected significant positive correlation between persistent subjective fatigue and task-related temporal accuracy, which they called a ‘fatigue-motor performance paradox’ (Pardini et al. 2013). It is possible that while there may indeed be some compensation for the neural dysfunction present, that compensation might itself lead to perceived fatigue. Equally, the presence of fatigue might necessitate the recruitment of additional brain areas to compensate for the extra ‘effort’ required for continued task performance (Podda et al. 2020). Indeed, these subjects reported a mild level of anxiety, suggesting that stress was frequently present. This cluster was composed of workers with a tendency to use the strategies ‘positive attitude’ and ‘problem-focus’, both considered active types, effective for dealing with stressful events. Research in healthy workers shows that active coping is associated with a higher work ability (van de Vijfeijke et al. 2013). This cluster also seemed to show a mild tendency to seek understanding, support and information from others (social support). The lower illness duration, lower disability level and higher work engagement observed in the subjects within this cluster are consistent with a more favourable overall profile. The second profile included individuals with a slightly higher level of work-related difficulties, with two-thirds of the subjects showing critical situations based on the MSQ-Job cut-off value. It is interesting to note that they tended to use ‘turning to religion’ and ‘positive attitude’ as their main coping strategies; a moderate tendency to use social support was also observed. Interestingly, despite greater work-related challenges, mood disorders were infrequent, and participants showed the highest levels of work engagement. The prominent use of religious coping may reflect its protective function in managing stress, as suggested by previous research indicating that religious individuals often report better adaptation to adverse events, even when stress levels are comparable to those of non-religious individuals (Worthington et al. 1996; Cardile et al. 2023). This aligns with findings from Prazeres et al. (2020), who observed lower anxiety levels among highly religious healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. These results suggest that turning to religion, while not universally adopted, may be a relevant psychosocial resource in sustaining engagement and emotional stability in the face of work-related strain.

Profile 3 was found to comprise wwMS with low-to-mild work-related difficulties, moderate mood disorders, and a mild tendency to use all the investigated coping strategies. In line with this, the most frequent work-related difficulties concerned the mental health-related MSQ-Job domains (‘Fatigue-related mental functions and symptoms’ and ‘Psychological and relational aspects’). Previous studies reported a positive association between work difficulties and depressive and anxiety symptoms (van der Hiele et al. 2021; van Egmond et al. 2021). This cluster was found to include subjects with a higher disease duration, higher disability, and lower work engagement, confirming previous reports of a relationship between increased work-related difficulties and higher disability levels (Ponzio et al. 2024), and a positive correlation between work engagement and work performance (Salanova et al. 2005). This group showed moderate mood disorders and no specific coping strategy (mild use of all types), although ‘denial’ was used more than the others. This finding agrees with a reported relationship between avoidance (i.e., ‘denial’) and the presence of mood disorders in MS (Keramat Kar et al. 2019). However, ‘denial’ as a strategy can be a maladaptive coping mechanism if it increases the level of psychological distress, discourages the individual from applying active coping mechanisms, and is connected with behavioural disengagement. On the other hand, ‘denial’ in the short term can be positive, i.e., a kind of stop-gap measure that gives the individual time to adjust to and manage the stressor (Vijayasingham and Mairami 2018).

Finally, the wwMS making up profile 4 experienced greater difficulties at work. These subjects had a high level of disability and a low level of work engagement, a pattern in line with previous reports of high disability associated with work-related difficulties (Ponzio et al. 2024) and work-related difficulties associated with lower work engagement (Salanova et al. 2005). In particular, they showed mild-to-moderate work difficulties—difficulties were reported across all domains, and all the subjects (100%) showed critical situations based on the MSQ-Job cut-off value—, moderate mood disorders, and a moderate tendency to use ‘problem focus’ and ‘positive attitude’ as coping strategies. It is interesting to note that active coping strategies were moderately preserved in these more severely affected subjects, and it is probably this that allowed them, despite their considerable work-related difficulties, to continue working (Vijayasingham and Mairami 2018). However, it is also important to note that active coping strategies can have positive or negative consequences, depending on the context (Mikula et al. 2014). The effectiveness of a coping strategy depends on the subject’s appraisal of their disease course at any given time. Hence, positive coping is not synonymous with the absence of distress, and paying too much attention to positive coping can lead to the creation of unrealistic expectations of consistent strength and perpetual positive or successful coping (Vijayasingham and Mairami 2018).

Limitation

The present study has several limitations that need to be taken into account. First, since the data came from self-reports collected online, we cannot exclude a response bias. Online questionnaires are preferred by users, but they have a higher non-response rate than face-to-face surveys (Heerwegh and Loosveldt 2008). The online recruitment of the participants limits the generalisability of the results since the use of technology may pose a barrier to elderly, socially/economically disadvantaged, technically inexperienced, or cognitively impaired people (Good et al. 2007). For these reasons, our internet-using participants may not be entirely representative of the MS population. Furthermore, we acknowledge that self-report measures are subject to bias (e.g., social desirability, recall bias), and that our convenience sampling approach may have introduced selection bias, possibly favouring individuals who are more engaged or better functioning. However, in MS, patient-reported outcomes are valuable tools for capturing individual experience and perception that should not be measured otherwise. Second, due to the cross-sectional design of the present study, causal relationships between variables could not be confirmed. Future longitudinal studies are needed to examine possible such relationships. Third, the psychological or pharmacological treatments were not taken into account. For example, the use of antidepressants or engagement in psychological support (e.g., psychotherapy or cognitive-behaviour therapy) could affect the self-reported mood and coping strategies, potentially masking or mitigating symptoms such as anxiety, depression, or dysfunctional coping styles.

Moreover, we did not collect detailed data on participants’ employment history, such as number and types of previous jobs, duration of work interruptions, or reasons for job changes. These factors could play a relevant role in shaping both current occupational status and psychological well-being.

Finally, the results of the cluster analysis are dependent on choices made by the researchers, given that there are no clear and objective criteria on the basis of which to decide the clustering method and the number of clusters to use (Dilts et al. 1995).

Conclusion

By defining specific profiles using a comprehensive approach that considers multiple contextual factors, it may be possible to design specific interventions to help pwMS continue working.

The findings of this study have several policy and practice implications. Understanding the profiles of workers with disabilities is important for designing functional, effective and coordinated vocational rehabilitation interventions. Better tailored interventions could help them to continue working and thus reduce the costs, both to the individual and to society, associated with loss of productivity. Perceived stress has been associated with a number of adverse physical and mental health outcomes (Beier et al. 2019), and exploration of this aspect as a possible target for interventions geared at favouring employment may be warranted. Adequate stress management in pwMS may benefit both physical and psychological well-being. Various stress reducers (adequate sleep, physical activity such as yoga and tai chi, more positive thought patterns, relaxation and deep breathing) reportedly have a positive impact on the physical and mental health of patients with MS (Kołtuniuk et al. 2021). Cognitive behavioural therapy may help individuals to cope with the unpredictability of the disease, and also help to modify the dysfunctional beliefs about MS that may be a further source of anxiety (Podda et al. 2020).

Occupational psychologists and vocational counsellors can use these profiles to screen for individuals at risk of work-related challenges and to design appropriate psychological support. Profiles characterized by moderate emotional symptoms and less effective coping may benefit from interventions aimed at reducing anxiety and depression and reinforcing adaptive strategies such as problem-solving and seeking social support. Conversely, those showing psychological resilience and low work-related difficulties, may require minimal intervention but could be engaged in workplace wellness initiatives or peer support roles.

Moreover, insurance professionals and case managers may find these profiles useful for informing decisions about work accommodations, rehabilitation planning, and return-to-work strategies. Rather than treating each psychological factor in isolation, these profiles offer practical, ready-to-use frameworks that facilitate early identification, stratification of support needs, and the implementation of more personalized and effective intervention pathways.

Knowledge of the different worker profiles may make it possible to predict their specific needs, build effective and multi-professional teams, and design early interventions and preventive measures aimed at improving the quality of life, at work, of people with disabilities.

The different profiles identified in the present study may provide a reliable framework for planning precision vocational rehabilitation interventions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Balducci C, Fraccaroli F, Schaufeli WB (2010) Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9). Eur J Psychol Assess 26(2):143–149. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000020

Ball GH, Hall DJ (1967) A clustering technique for summarising multivariate data. Behav Sci 12:153–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830120210

Beier M, Hartoonian N, D’Orio VL, Terrill AL, Bhattarai J, Paisner ND, Alschuler KN (2019) Relationship of perceived stress and employment status in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Work 62(2):243–249. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-192859

BSRM British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine (2010) Vocational assessment and rehabilitation for people with long-term neurological conditions: recommendations for best practice. https://abil.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Reference-3.pdf (accessed 08/07/2025)

Cardile D, Corallo F, Ielo A, Cappadona I, Pagano M, Bramanti P, D’Aleo G, Ciurleo R, De Cola MC (2023) Coping and quality of life differences between emergency and rehabilitation healthcare workers. Healthcare 9 11(16):2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11162235

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK (1989) Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc 56:267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

Costantini M, Musso M, Viterbori P, Bonci F, Del Mastro L, Garrone O, Venturini M, Morasso G (1999) Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Support Care Cancer 7(3):121–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005200050241

Dilts D, Khamalah J, Plotkin A (1995) Using cluster analysis for medical resource decision making. Med Decis Mak 15:333–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X9501500404

De Meo E, Portaccio E, Giorgio A, Ruano L, Goretti B, Niccolai C, Patti F, Chisari CG, Gallo P, Grossi P, Ghezzi A, Roscio M, Mattioli F, Stampatori C, Simone M, Viterbo RG, Bonacchi R, Rocca MA, De Stefano N, Filippi M, Amato MP (2021) Identifying the distinct cognitive phenotypes in multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 78(4):414–425. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4920

Dorstyn DS, Roberts RM, Murphy G, Haub R (2019) Employment and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analytic review of psychological correlates. J Health Psychol 24:38–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317691587

Duda RO, Hart PE (1973) Pattern classification and scene analysis. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA

Good A, Stokes S, Jerrams-Smith J (2007) Elderly, novice users and health information websites: issues of accessibility and usability. J Health Inf Manag 21(3):72–79

Hakanen JJ, Bakker A, Schaufeli W (2006) Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J Sch Psychol 43:495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Heerwegh D, Loosveldt G (2008) Face-to-face versus web surveying in a high-internet coverage population: Differences in response quality. Public Opin Q 72(5):836–846. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn045

Honarmand K, Feinstein A (2009) Validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale for use with multiple sclerosis patients. MSJ 15(12):1518–1524. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458509347150

Ivandic I, Kamenov K, Rojas D, Cerón G, Nowak D, Sabariego C (2017) Determinants of work performance in workers with depression and anxiety: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(5):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14050466

Johansson S, Ytterberg C, Claesson IM, Lindberg J, Hillert J, Andersson M, Widén Holmqvist L, von Koch L (2007) High concurrent presence of disability in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 254(6):767–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-006-0431-5

Keramat Kar M, Whitehead L, Smith CM (2019) Characteristics and correlates of coping with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 41(3):250–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1387295

Kołtuniuk A, Kazimierska-Zając M, Cisek K, Chojdak-Łukasiewicz J (2021) The role of stress perception and coping with stress and the quality of life among multiple sclerosis patients. Psychol Res Behav Manag 14:805–815. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S310664

Leavitt VM, Tosto G, Riley CS (2018) Cognitive phenotypes in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 265(3):562–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-8747-5

Mikula P, Nagyova I, Krokavcova M, Vitkova M, Rosenberger J, Szilasiova J, Gdovinova Z, Groothoff JW, van Dijk JP (2014) Coping and its importance for quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 36(9):732–736. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.808274

Miller A, Dishon S (2006) Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the impact of disability, gender and employment status. Qual Life Res 15(2):259–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-005-0891-6

Pardini M, Bonzano L, Roccatagliata L, Mancardi GL, Bove M (2013) The fatigue-motor performance paradox in multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep 3:2001. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02001

Podda J, Pedullà L, Monti Bragadin M, Piccardo E, Battaglia MA, Brichetto G, Bove M, Tacchino A (2020) Spatial constraints and cognitive fatigue affect motor imagery of walking in people with multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep 14 10(1):21938. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79095-3

Podda J, Ponzio M, Messmer Uccelli M, Pedullà L, Bozzoli F, Molinari F, Monti Bragadin M, Battaglia MA, Zaratin P, Brichetto G, Tacchino A (2020) Predictors of clinically significant anxiety in people with multiple sclerosis: a one-year follow-up study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 45:102417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2020.102417

Podda J, Ponzio M, Pedullà L, Monti Bragadin M, Battaglia MA, Zaratin P, Brichetto G, Tacchino A (2021) Predominant cognitive phenotypes in multiple sclerosis: Insights from patient-centered outcomes. Mult Scler Relat Disord 51:102919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2021.102919

Podda J, Di Antonio F, Tacchino A, Pedullà L, Grange E, Battaglia MA, Brichetto G, Ponzio M (2024) A taxonomy of cognitive phenotypes in Multiple Sclerosis: a 1-year longitudinal study. Sci Rep. 2 14(1):20362. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71374-7

Ponzio M, Podda J, Pignattelli E, Verri A, Persechino B, Vitturi BK, Bandiera P, Manacorda T, Inglese M, Durando P, Battaglia MA (2024) Work difficulties in people with multiple sclerosis. J Occup Rehabil 34(3):606–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-023-10149-9

Prazeres F, Passos L, Simões JA, Simões P, Martins C, Teixeira A (2020) COVID-19-related fear and anxiety: spiritual-religious coping in healthcare workers in Portugal. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010220

Raggi A, Giovannetti AM, Schiavolin S, Confalonieri P, Brambilla L, Brenna G, Cortese F, Covelli V, Frangiamore R, Moscatelli M, Ponzio M, Torri Clerici V, Zaratin P, Mantegazza R, Leonardi M (2015) Development and validation of the multiple sclerosis questionnaire for the evaluation of job difficulties (MSQ-Job). Acta Neurol Scand 132:226–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane12387

Salanova M, Agut S, Peiró JM (2005) Linking organizational facilitators and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: the mediation of service climate. J Appl Psychol 90:1217–1227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1217

Schaufeli W, Salanova M, González-Roma V, Bakker AB (2002) The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud 3:71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015630930326

Schaufeli W, Bakker AB (2004) Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement. J Organ Behav 25:293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M (2006) The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire. Educ Psychol Meas 66(4):701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Schiavolin S, Giovannetti AM, Leonardi M, Brenna G, Brambilla L, Confalonieri P, Frangiamore R, Mantegazza R, Moscatelli M, Clerici VT, Cortese F, Covelli V, Ponzio M, Zaratin P, Raggi A (2016) Multiple sclerosis questionnaire for job difficulties (MSQ-Job): definition of the cut-off score. Neurol Sci 37:777–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2495-z

Shahrbanian S, Duquette P, Kuspinar A, Mayo NE (2015) Contribution of symptom clusters to multiple sclerosis consequences. Qual Life Res 24:617–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0804-7

Sica C, Magni C, Ghisi M, Altoè G, Sighinolfi C, Chiri LR, Franceschini S (2008) Coping Orientation to Problems Exerpeinced- Nuova Versione Ialiana (COPE-NVI): uno strumento per la misura degli stili di coping. Psicoterapia Cognit Comport 14(1):27–53

van de Vijfeijke H, Leijten FRM, Ybema JF, van den Heuvel SG, Robroek SJW, van der Beek AJ, Burdorf A, Taris TW (2013) Differential effects of mental and physical health and coping style on work ability: a 1-year follow-up study among aging workers. J Occup Environ Med 55:1238–1243. https://doi.org/10.1097/jom0b013e3182a2a5e1

van der Hiele K, van Gorp D, Benedict R, Jongen PJ, Arnoldus E, Beenakker E, Bos HM, van Eijk J, Fermont J, Frequin S, van Geel BM, Hengstman G, Hoitsma E, Hupperts R, Mostert JP, Pop P, Verhagen W, Zemel D, Frndak SE, Heerings M, Middelkoop H, Visser LH (2016) Coping strategies in relation to negative work events and accommodations in employed multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 2:2055217316680638. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055217316680638

van der Hiele K, van Gorp DAM, van Egmond EEA, Jongen PJ, Reneman MF, van der Klink JJL, Arnoldus EPJ, Beenakker EAC, van Eijk JJJ, Frequin STFM, de Gans K, Hengstman GJD, Hoitsma E, Gerlach OHH, Verhagen WIM, Heerings MAP, Middelkoop HAM, Visser LH (2021) Self-reported occupational functioning in persons with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: does personality matter? J Neurol Sci 427:117561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2021.117561

van Egmond E, van der Hiele K, van Gorp D, Jongen PJ, van der Klink J, Reneman MF, Beenakker E, van Eijk J, Frequin S, de Gans K, van Geel BM, Gerlach O, Hengstman G, Mostert JP, Verhagen W, Middelkoop H, Visser LH (2022) Work difficulties in people with multiple sclerosis: the role of anxiety depression and coping. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 8(3):20552173221116282. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552173221116282

van Egmond E, van Gorp D, Honan C, Heerings M, Jongen P, van der Klink J, Reneman M, Beenakker E, Frequin S, de Gans K, Hengstman G, Hoitsma E, Mostert J, Verhagen W, Zemel D, Middelkoop H, Visser L, van der Hiele K (2021) A Dutch validation study of the multiple sclerosis work difficulties questionnaire in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 43:1924–1933. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1686072

Vijayasingham L, Mairami FF (2018) Employment of patients with multiple sclerosis: the influence of psychosocial-structural coping and context. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis 26(8):15–24. https://doi.org/10.2147/dnnd.s131729

Vitturi BK, Rahmani A, Dini G, Montecucco A, Debarbieri N, Bandiera P, Battaglia MA, Manacorda T, Persechino B, Buresti G, Ponzio M, Inglese M, Durando P (2022) Spatial and temporal distribution of the prevalence of unemployment and early retirement in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One 17(7):e0272156. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272156

Vitturi BK, Rahmani A, Dini G, Montecucco A, Debarbieri N, Bandiera P, Ponzio M, Battaglia MA, Persechino B, Inglese M, Durando P (2022) Stigma discrimination and disclosure of the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in the workplace: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(15):9452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159452

Vitturi BK, Rahmani A, Dini G, Montecucco A, Debarbieri N, Bandiera P, Ponzio M, Battaglia MA, Brichetto G, Inglese M, Persechino B, Durando P (2023) Work barriers and job adjustments of people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 33(3):450–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10084-1

Wong J, Kallish N, Crown D, Capraro P, Trierweiler R, Wafford QE, Tiema-Benson L, Hassan S, Engel E, Tamayo C, Heinemann AW (2021) Job accommodations return to work and job retention of people with physical disabilities: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 31(3):474–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09954-3

Worthington EL, Kurusu TA, McCullough ME, Sandage SJ (1996) Empirical research on religion and psychotherapeutic processes and outcomes: a 10-year review and research prospectus. Psychol Bull 119:448–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.448

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the people with MS who participated in this study and Catherine Wrenn for her valuable support in revising the use of the English language. This work was funded by the Italian National Institute for Insurance against Accidents at Work (INAIL) in the framework of the BRIC-2019 ‘PRISMA’ project (Bando BRIC 2019_ID 24).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP was responsible for study concept and design. MP, JP and EG designed the study and developed the protocol. MP and TM participated in the data acquisition. MP, JP, EG and FDA conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TM, GB and BP participated in the data interpretation and provided comments on the paper. All the authors participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work and all read and approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study aimed at examining worker profiles in individuals with multiple sclerosis was approved by the Liguria Regional Ethics Committee (Italy) on July 19, 2021 (Approval No. PR 221/2021). All procedures followed in this study comply with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Each participant provided informed consent to take part in the study after reading an information sheet that outlined the study’s purpose and the nature of their participation. Consent was obtained between September 2021 and February 2022. The information sheet was displayed at the beginning of the online survey, and participants gave their consent by selecting the option “Proceed with the questionnaire.” A privacy notice was also attached and clearly visible at the start of the survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ponzio, M., Grange, E., Di Antonio, F. et al. Disability worker profiles: examining work-related difficulties, mood, and coping strategies in workers with multiple sclerosis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1721 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05997-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05997-0