Abstract

With the rapid development of education for older adults in China, the link between education participation and mental health/subjective well-being (SWB) among older adults has received increasing attention. Rather than merely considering whether older adults participate in late-life learning or attend educational institutions, the extent of their engagement in educational activities may be more influential in determining SWB. The current study aims to examine the association between the degree of educational participation (DEP) for older adults and SWB and related mechanisms in China. Using a nationally representative sample of the University of the Third Age (U3A), this study explored the association between DEP and SWB indicated by life satisfaction, positive affect, negative affect, and depression; and further examined the mediating roles of attitudes to aging and moderating roles of family intimacy. Results indicated that DEP in the U3A predicted students’ SWB, indicated by all four indicators; attitudes to aging, including psychosocial loss (PL), physical change (PC), and psychological growth (PG), mediated the association between DEP and SWB; and family relationships moderated the direct and indirect associations, to some extent. These findings offer a novel perspective for exploring the mechanisms through which lifelong education affects mental health and provide insights for policymakers and governments to actively address issues of aging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population aging presents both challenges and opportunities for human development. The seventh census reported 264 million people aged 60 or above, accounting for 18.7% of the population, and a life expectancy had increased to 78.2 years, with some regions exceeding 80 years (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2021). Many retirees still possess good physical condition, cognitive function, and knowledge experience and can continue to play a role in social life. As China transitions into a moderately aged society, actively coping with population aging has become a national strategic priority for China (State Council of China, 2022).

According to the World Health Organization (2002), “participation” is one of the core pillars of the active aging framework, alongside “health” and “security.” Education for older adults is a critical form of social participation and plays an increasingly significant role in ensuring the right to lifelong learning and enhancing overall quality of life for older adults (World Health Organization, 2015). Learning ability is identified as one of five functional domains for healthy aging (World Health Organization, 2020). The Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030) further highlights “Quality education” as one of 17 initiatives aimed at empowering older individuals to maintain decision-making abilities and preserve a sense of purpose, identity, and independence (World Health Organization, 2020).

In East Asian countries influenced by Confucianism, such as China, individuals tend to exhibit a more positive attitude toward education and are more inclined to dedicate their free time to learning (Chui, 2012). Deeply rooted cultural and educational traditions encourage older adults to pursue learning not merely for utilitarian purposes but out of genuine interest and curiosity, a practice that contributes to enhanced well-being in later life (Chui, 2012). Furthermore, the evolution of elderly education in China has been closely linked to decades of economic progress and social transformation (Zhao & Chui, 2019). On one hand, rapid economic development has enabled governments to allocate increased resources toward expanding educational opportunities for older adults; on the other hand, improved economic conditions and stable pension systems have led older individuals to invest more in social and cultural services that enrich their leisure activities, including educational pursuits. Additionally, the trend toward smaller family units has resulted in fewer familial responsibilities and more leisure time for many older adults, thereby making participation in initiatives such as U3A a popular lifestyle choice among retired populations.

The Chinese government considers the development of education for older adults to be a crucial strategy for addressing the challenges of an aging population, fostering a learning society, and enhancing the quality of life among the elderly (State Council of China, 2016). Since the establishment of the first University of the Third Age (U3A) in 1983, the number of U3As in China has surged to nearly 80,000 by 2020, with over 13 million registered students (Editorial Committee of the Blue Book of Education for Older Adults, 2021). A comprehensive educational system for older adults has gradually emerged nationwide, marked by the development of U3As, community education programs, and distance learning initiatives. As a well-organized educational institution, the U3A offers older adults the opportunity for more in-depth and systematic learning. Nonetheless, despite being the country with both the highest number of U3As and the largest aging population, research examining the influence and mechanisms of educational participation on quality of life and SWB remains limited and needs further investigation.

Education for older adults and SWB

The rapid development of U3A worldwide has increased attention on the link between participation in educational activities and the quality of life among older adults. Existing research has preliminarily revealed that participation in education for older adults positively influences e quality of life and mental health (Chen, Song, & Zhang, 2023; Cybulski et al., 2020; Schoultz, Öhman, & Quennerstedt, 2020), including improvements in emotional function (Narushima, Liu, & Diestelkamp, 2013; Waller et al., 2018), cognitive function (Wang et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2010), physical function (Formosa, 2014), and even prosocial behaviors (Sung et al., 2023). Notably, it has been shown to have a positively impact on SWB, including increased positive affect, life satisfaction, and lower negative affect and depression (Chen et al., 2021; Chua & de Guzman., 2014). Some studies revealed multiple benefits of education on SWB (Bužgová et al., 2024; Narushima et al., 2013; 2018) and growth of these benefits increases with age (Mirowsky, & Ross, 2008). An intervention study further revealed that learning programs for older adults improved SWB in multiple aspects, as indicated by higher life satisfaction, self-esteem, and lower depressive symptoms (Chua & de Guzman, 2014). More recently, an organized educational program at U3A was found to bolster enhanced older adults’ functional abilities, intrinsic capacities for active living, and personal well-being (Bužgová et al., 2024).

Degree of participating in education for older adults and SWB

Compared to merely attending educational institutions, the degree of educational participation (DEP) is arguably more critical to the subjective well-being (SWB) of older adults. Here, the DEP refers to the extent of engagement in learning and activities at institutes like U3A, which often encompasses organizational identification and integration, emotional attachment, and level of learning motivation and involvement (Chen et al., 2021). U3A’s core mission is to foster individual development, align with personal interests, and enhance the social integration of older adults through systematic courses and organized activities. Accordingly, the extent to which U3A students perceive learning participation as a vital component of their lives may significantly influence their SWB (Editorial Committee of the Blue Book of Education for Older Adults, 2021). Unlike compulsory education agencies, education organizations for older adults, such as U3As, feature a more flexible and non-mandatory structure. Attendance to U3As is not primarily aimed at achieving good grades or credentials; instead, the intensity and degree of involvement more accurately reflect genuine willingness and interest in learning, which in turn is more likely to affect SWB. The level of engagement in educational activities can determine the overall effectiveness of learning, further influencing improvements in SWB. Empirical research indicates that students who engage in longer learning periods exhibit higher levels of SWB regardless of the subject matter (Narushima et al., 2013) and that these benefits extend to other aspects of life (Narushima, Liu, & Diestelkamp, 2018). Moreover, Leung and Liu (2011) observed an inverse relationship between participation in lifelong education and psychosomatic complaints, noting that increased course enrollment correlated with fewer somatic symptoms. Complementing these findings, a nationwide cohort study in China found that each additional year of adult education was associated with a 13.1% reduction in the odds of depression (Guo, Yang (2025)). A systematic literature review further supports that long-term participation in organized, formal education enhances well-being, quality of life, cognitive function, self-dependence, and a sense of belonging among older adults (Noble et al., 2021).

Educational organizations for older adults possess characteristics similar to those of general social organizations, particularly sociality and functionality (Fei, 2020; Park et al., 2013). Accordingly, researchers can assess the degree of educational participation through two primary dimensions: organizational integration (sociality) and learning involvement (functionality). Organizational integration pertains to the relationships among students and their identification with and attachment to the educational community, which has been shown to alleviate depressive symptoms and enhance mental health (Chen et al., 2021). In contrast, learning involvement encompasses motivation, purpose, and the effectiveness of learning, as demonstrated by the acquisition of knowledge and skills. Achieving learning objectives has positive ramifications for the self-worth and mental health of elderly learners (Lewis, 2014). Furthermore, experimental research indicates that both goal-based cognitive training and socially engaging learning interventions can improve cognitive plasticity in older adults (Stine-Morrow et al., 2014). Consequently, organizational integration and learning involvement may represent the core dimensions of educational participation that influence students’ SWB. Based on these insights, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: DEP, including both learning involvement and organizational integration, is positively associated with SWB.

Potential mediating role: Based on attitudes to self-aging perspective

Learning in later life may influence SWB both directly and indirectly through diverse socio-psychological mechanisms; however, few empirical studies have explored these mechanisms (Field, 2009; Gierszewski & Kluzowicz, 2021). Some researchers explain the positive effects of educational participation in later life on SWB from multiple perspectives, including the acquisition of coping skills (Field, 2009), the development of psychosocial resources (Hammond, 2004; Ristl et al., 2025), and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Zhang et al., 2024). One relatively underexplored mechanism is attitudes toward aging. Attitudes toward aging refers to the way people think and feel about the aging process and growing old, including general aging attitudes and self-aging attitudes (Cheng, Fung, & Chan, 2009). A positive self-aging attitude has been associated with improved SWB, such as less depression (Brother et al., 2021; Liu, Wei, Peng & Guo, 2021), lower anxiety (Bryant et al., 2012), and higher hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (Park et al., 2024).

Participation in educational activities may positively influences older adults’ self-perception of aging, thereby enhancing their SWB. Such engagement fosters motivation, facilitates knowledge acquisition, and contributes to skill development, which in turn improves self-efficacy and attitudes toward self-aging. By integrating socioemotional selectivity theory, the selective optimization with compensation model, and the psychological resources perspective (Dumitrache, Rubio, & Cordon-Pozo, 2019), the attitudes-to-aging perspective posits that later-life education serves as a compensatory activity that counteracts the decline in resource acquisition resulting from aging and functional deterioration. It promotes the maintenance and accumulation of psychological, social, and informational resources, thereby adjusting older adults’ attitudes toward self-aging, expectations for their later life, as well as associated life planning. Thus, education in later life may improve aging attitudes and future expectations by reinforcing psychosocial resources, ultimately promoting overall well-being and mental health.

Researchers have demonstrated the beneficial impact of social participation, including participation in educational activities, on promoting positive attitudes toward self-aging (Isla & Andrew, 2018; Liu, Duan, & Xu, 2020; Zielińska-Więczkowska & Sas, 2020). U3A members exhibit more favorable perceptions of self-aging than their peers (Camargo et al., 2018) and report experiencing less age discrimination alongside more optimistic future expectations (Zielińska-Więczkowska, Muszalik, & Kędziora-Kornatowska, 2012). Gierszewski and Kluzowicz (2021) summarized that changing stereotypical thinking about age is one of the key benefits of attending U3A, alongside satisfying needs related to knowledge and skills. Receiving education has fostered a positive social image of older adults, broken the stereotype portraying them as “inactive” and “socially alienated,” and facilitated the development of age-friendly environments (Hardy, Oprescu, & Millear et al., 2017; Maulod & Lu, 2020). Education organizations provide a protective environment free from age stereotypes for older adults, who often avoid negative thoughts about age when discussing aging topics and emphasize the positive value of growing older (Roberts, 2021). Lifelong learning and U3A attendance help the elderly reduce implicit or explicit ageism, allowing them to maintain a certain middle-aged identity and avoid being labeled “old people” (Formosa, 2021; Romaioli & Contarello, 2021). A recent study revealed that U3A participants can acquire diverse gains, with potential to shape attitudes toward aging (Gao et al. (2024)). It can be inferred that education for older adults improves stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes held by other age groups, which in turn enhances older adults’ positive perception of self-aging (Camargo et al., 2018).

Several theories help elucidate the potential mediating role of aging attitudes. The resources accumulation perspective posits that education increases one’s competence capital (e.g., knowledge and skills) and social capital (e.g., social network and trust), thereby motivating future expectations and plans and fostering conscious/explicit aging attitude expressions (Diehl et al., 2014; Ristl et al., 2025). Social network perspective suggests that larger and more diverse networks are associated with more positive self-perception of aging (MeyerWyk, Wurm (2024); Cohn-Schwartz et al., 2023), whereas smaller networks or social isolation tend to correlate with more negative self-perceptions (Jung et al., 2021). Additionally, regularly attending educational organizations allows older adults to engage with diverse environments, indirectly increasing social support and access to information, which in turn enhances their self-perceptions of aging. Drawing on the reserve capacity hypothesis, learning activities also serve as compensatory strategies to buffer declines in functional capacity, empowering older adults by increasing their independence, confidence, and knowledge while promoting a more positive attitude toward aging (Gallo & Matthews, 2003; Withnall, 2010). Based on these theoretical foundations, we propose the following hypothesis regarding the mediating mechanism.

Hypothesis 2: Attitudes to self-aging mediates the association between DEP and SWB.

Potential moderating role of family relationships

Family relationships are critical in supporting SWB, as they provide both material and emotional support. With age, life goals related to social emotion are prioritized due to the perception of limited remaining time (Lang & Carstensen, 2002). Thus, older people are more likely to seek support from family and close relations for maintaining SWB. Studies on education for older adults and its impact on SWB need to consider the role of family environment, especially family relationships. Family relationships can influence both the opportunities and motivations for older adults’ participation in education, as well as the extent of benefit derived from it (Bronfenbrenner, 1999; Zielińska-Wieczkowska et al., 2012). Significant others, especially family members, typically provide essential support for educational participation (Ko, 2020). Furthermore, family intimacy buffered the negative effects of low organizational integration on SWB (Chen et al., 2021). From another perspective, when intimate relationships are poor and insufficient, the external social capital and non-intimate relationships obtained by participating in educational activities for older adults may mitigate these adverse effects (Holtfreter, Reisig, & Turanovic, 2017). Family relationships represent intimate connections, whereas educational participation can cultivate non-intimate networks among older adults. Examining the independent and interactive roles of these relationships is crucial for understanding the significance of multi-level social environments in the lives of older adults. As a security base that provides emotional and social support, the family may enhance the positive effects of educational participation on attitudes toward self-aging, thereby contributing to the maintenance and improvement of SWB. Based on these considerations, we propose the following hypothesis regarding moderating effects.

Hypothesis 3: Family relationships moderate the direct and indirect associations between DEP and SWB. Specifically, the moderating role is reflected in the following two aspects.

Hypothesis 3a: Family relationships moderate the association between DEP and attitudes to self-aging.

Hypothesis 3b: Family relationships moderate the association between DEP and SWB.

Current study

Existing research on the mental health effects of educational engagement among older adults is predominantly based on small-sample surveys or qualitative interviews. Additionally, there is a notable gap in studies that comprehensively elucidate the mechanisms by which DEP influence on SWB. More importantly, compared to the flourishing development of education for older adults, empirical research on this topic lags significantly in both quantity and quality. Some fundamental and critical issues remain insufficiently studied, such as the impact of later-life education on quality of life, physical and mental health, and its underlying mechanisms and conditions. Due to the singularity of methods and data sources, exploration of these mechanisms has been lacking, resulting in prolonged low-level and repetitive investigations that weaken the validity and reliability of findings, making it challenging to provide effective guidance for national elderly education policies. The current study aims to address this by utilizing a nationally representative sample to explore the association between degree of U3A involvement and SWB, and the potential mediating roles of attitudes toward aging and moderating roles of family relationships. As a mediating mechanism, attitudes to self-aging can explain why educational participation of older adults affects SWB. As a moderating variable, family relationship helps to answer under what conditions the direct and indirect effects of education participation on SWB will be different (See Fig. 1 for the research framework).

Methods

Participants

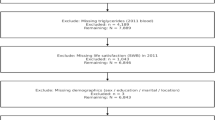

Data for the present study were derived from a research program funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Ethical approval for the program was secured from the Institutional Review Board of the authors’ affiliated institution prior to the formal study. The informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the formal survey. The investigation was conducted anonymously from October 2021 to January 2022. Participants consisted of formally registered U3A students aged 50 or older, who were enrolled for at least one semester and were retirees. Approximately 25,000 questionnaires were distributed, with 23,124 returned. After excluding questionnaires with a loss rate exceeding 20%, 21,482 valid questionnaires (a valid response rate of 92.9%) were analyzed.

Procedures

Several sampling strategies were employed to ensure national representativeness and U3A coverage. Specifically, the survey was conducted in 30 U3As across 25 provincial-level regions (provinces, autonomous regions, and provincial-level cities) in mainland China, with one U3A selected per city. The original plan was to select at least one U3A in each provincial administrative region, but during the survey period, the COVID-19 pandemic worsened in some areas, rendering effective surveying impossible. As a result, the sample covered 25 provincial-level regions in six administrative regions in China. Moreover, the sample size of each U3A was roughly based on the number of registered students in each U3A. The majority of the U3As had a sample size between 500 and 1000 people. In addition, the sample covered major specialties or course programs. The survey revealed a significantly higher proportion of female students (81.1%) than male students (18.9%), reflecting the real gender structure of U3As in China (Zhao & Chui, 2019). Investigators consisted of psychologists and well-trained cadres and workers in the U3A. Prior to the start of the formal survey, the surveyors were trained to familiarize themselves with the entire questionnaire and procedure. Surveys were usually conducted during breaks of classes or after classes had ended. Table 1 and Table S1 in Supplementary Materials provide detailed information on sample distribution.

Instruments

Degree of education participation scale (DEPs)

The Degree of Educational Participation scale (DEPs) assesses the extent of involvement in the learning activities offered by U3A. This instrument comprises two dimensions: organizational integration (OI) and learning involvement (LI). Organizational integration, a central construct of the social dimension, captures students’ sense of identity and belonging within U3A, reflecting peer relationships and community sense within class groups (Chen et al., 2021). In contrast, learning involvement, the key indicator of the educational function, denotes the intensity of an individual’s motivation and commitment to acquiring knowledge and skills through U3A. Both subscales are measured using six items each.

The reliability and validity of the OI subscale has been preliminarily confirmed (Chen et al., 2021). This subscale comprises six items: Students in my class get along well with one other; I am proud to be a member of my class; I can be accepted and respected by most students in the class; I like the atmosphere of my class, and if I leave, I will miss my class and classmates; even after departing from U3A, I hope to maintain contact with some teachers and students; in general, my relationship with the whole class is harmonious and friendly.

The LI subscale, as referred to in some questionnaires or scales, is designed to assess individuals’ positive attitudes toward later-life learning, involvement level in lifelong learning, and motivation toward learning (Coskun & Demirel, 2010; Gunuc, Odabasi, & Kuzu, 2014). The subscale comprises six items: I always want to do better than others in learning; I always try my best to overcome difficulties in study; I always pay high attention in study; I will ask questions in time every time I encounter questions in class; I always try my best to improve my study after class; I consciously apply these knowledge and skills in my daily life.

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the 12-item DEPs identified two eigenvalues >1.0 (6.51 and 1.59, respectively), with the resulting two factors corresponding precisely to the original subscales. These factors together accounted for 67.48% of the total variance, and all items exhibited factor loadings exceeding 0.50. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) further supported the two-factor model, which demonstrated a superior goodness of fit (χ2 = 3374.21, df = 53, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.03) compared to a single-factor solution (χ2 = 24365.40, df = 54, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.76, TLI = 0.70, RMSEA = 0.15, SRMR = 0.10). Given the relatively high correlation between the two factors (r = 0.60), an aggregate score of all 12 items was used as an indicator of the degree of educational participation. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for DEPs, OI, and LI were 0.92, 0.89, and 0.89, respectively.

To date, there is a lack of widely recognized and authoritative assessment tools or indicators for evaluating the extent of educational participation among older adults and its impact on well-being of older adults in China. The DEPs and its two dimensions capture the primary aspects of educational participation level.

Subjective well-being (SWB)

Subjective well-being (SWB) is a comprehensive psychological construct employed to evaluate individuals’ overall quality of life and mental health. As delineated by Diener et al. (1999), SWB comprises three key components: life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect. Furthermore, prior research has incorporated depressive symptoms as an additional indicator of SWB. Consequently, the present study assesses SWB using four indicators: high life satisfaction, elevated positive affect, reduced negative affect, and minimal depressive symptoms.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) assesses overall life satisfaction using five items (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”). The Chinese version of the SWLS demonstrated robust internal consistency, construct validity, and gender invariance (Bai et al., 2011). In the present study, items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.87.

The Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) assesses emotional aspects of SWB and comprises two subdimensions (Watson et al., 1988). Participants rated the extent to which they experienced positive affect (e.g., excitement) and negative affect (e.g., distress) over the past month using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). In the current study, a short version of the PANAS with 12 items was used, with each subscale consisting of six items. The Chinese version of PANAS has demonstrated robust psychometric properties (Liang & Zhu, 2015). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.88 and 0.85 for PA and 0.85 for NA.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression scale (CES-D) assesses depressive symptoms experienced over the past month (Radloff, 1977). Items are rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (fewer than 1 day) to 3 (5–7 days), with higher average scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. This instrument has demonstrated robust reliability and internal validity among middle-aged and older Chinese adults (Cheng & Chan, 2005). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

Attitudes to ageing questionnaire (AAQ)

The AAQ is a multidimensional instrument designed to assess individual attitudes toward self-aging. It comprises three subscales: psychosocial loss (PL), physical change (PC), and psychological growth (PG) (Laidlaw et al., 2007). A brief 12-item version, which maintains a three-factor structure, has demonstrated robust psychometric properties among older Chinese individuals (Gao, Laidlaw, & Wang, 2024). Each subscale is evaluated using four items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes toward aging (noting that the PL subscale is reverse scored). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the AAQ was 0.77, with subscale alphas of 0.72, 0.76, and 0.70 for PL, PC, and PG, respectively.

Family relationships

The study employed the Family Cohesion (FC) subscale of the Family Environment Scale (FES) to evaluate family relationships (Fei et al., 1991). This subscale comprises nine items rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) (e.g., “My family members will do their best to support and help one another”), with higher scores reflecting greater family cohesion. The Chinese version of the FES has been demonstrated to be both reliable and valid (Fei et al., 1991). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the subscale was 0.81.

Demographic and socioeconomic variables

Demographic and socioeconomic variables included age, gender, marital status, and educational attainment. Participants reported their individual monthly income as an indicator of economic status, and self-rated their physical health using a single-item measure with five response options. In addition, participants assessed the general frequency of their social participation in daily life on a five-point scale, excluding involvement with U3A or similar organizations. These variables were treated as continuous measures in subsequent analyses, which controlled for factors moderately related to the main variables, such as attitudes toward aging and SWB (Bryant et al., 2012; Dai et al., 2013; Zielińska–Więczkowska, Kedziora-Kornatowska, & Ciemnoczoɫowski, 2011). Furthermore, the length of admission to U3As, which may confound the effect of educational participation, was also controlled for in later analyses (see Table 1).

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows version 22, including descriptive statistics, correlations, and regressions. Mediation and moderated mediation analyses were conducted using Models 4 and 8 in Hayes (2013) INDIRECT procedure. In these analyses, the evaluation of DEP in U3A served as the independent variable, the three dimensions of AAQ functioned as parallel mediators, and four indicators of SWB were treated as outcome variables. Family relationships were incorporated as a moderator, and eight covariates were controlled during the moderated mediation analyses. Owing to the large dataset drawn from 30 U3As across 25 provincial-level administrative regions, SPSS was also employed to assess data suitability for multilevel analysis. The multilevel models yielded intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of 0.014 for life satisfaction, 0.016 for positive affect, 0.016 for negative affect, and 0.020 for depression. Additionally, the ICCs for AAQ and its sub-dimensions—PG, PL, and PC—were 0.021, 0.017, 0.07, and 0.026, respectively. Given that all ICC values for the primary variables were below 0.059, multilevel analyses were deemed unnecessary (Cohen, 1977).

Results

Common method bias test

The major variables of the study were derived from self-reported surveys, hence necessitating a check for potential common methodological biases prior to analysis. The Harman single-factor method (Hair et al., 1998) was employed, revealing a largest eigenvalue of 13.80 and a single factor explaining 23% of the total variance. This result suggests no severe common method bias.

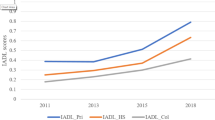

Descriptive and correlational analyses

Table 2 presents the descriptive characteristics of primary variables. The mean scores for DEP (4.16), OI (4.29) and LI (4.04) were higher values compared to median values. Generally, students in U3A exhibited a partially positive self-perception of aging, as indicated by higher PG and PC scores and lower PL scores. Table 2 displays the results of pairwise correlation analysis among main variables. The observed correlations aligned with expected directions. Specifically, DEP and its sub-dimensions, OL and LI, were positively correlated with life satisfaction and positive affect, and negatively correlated with negative affect and depression. Moreover, DEP and its two sub-dimensions were associated with attitudes to self-aging, while attitudes to self-aging were associated with all four indicators of SWB. Additionally, significant small to moderate pairwise correlations were observed between family relationships and the measures of SWB, attitudes to aging, and DEP.

Degree of educational participation and SWB

Correlational analyses indicated associations between DEP and sub-dimensions OI and LI with SWB indicators. The results suggest that a higher learning dedication correlates with higher SWB. Multiple regression analyses revealed that DEP predicted SWB, even after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, and attitudes to aging variables (see Table 3). The predictive effect remained significant when family relationships and its interactive effect with DEP are controlled (see Table 4). Students in U3As with higher scores in OI and LI reported greater life satisfaction and positive affect, as well as lower levels of negative affect and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, DEP exerted a more pronounced impact on enhancing positive SWB than on diminishing negative SWB. Overall, these findings confirm hypothesis 1

Mediating roles of attitudes to self-aging

Using Model 4 in Hayes (2013) INDIRECT procedure, we conducted a series of mediating model analyses with PG, PL, and PC as parallel mediators. Generally, the mediating effects of all three subdimensions of attitudes to aging were significant. Specifically, DEP contributes to perceived age-related attitudes change, including a more positive change growth (βPG = 0.47, p < 0.001; βPC = 0.46, p < 0.001) and a less negative change (βPL = −0.16, p < 0.001) (see Tables 3 and S2 in the Supplementary Materials). Furthermore, PG, PL, and PC mediated the associations between DEP and four indicators of SWB, largely confirming Hypothesis 2. Regression analyses revealed that the predictive effects of DEP on the three dimensions of attitudes to aging were significant. For instance, when both the predictor and the three parallel mediators (PG, PL and PC) were entered into the mediation model, the effect of DEP on life satisfaction decreased from β = 0.45 (t = 50.63, p < 0.001) to β = 0.25, with a significant reduction (ΔR² = 0.09, Cohen’s f² = 0.13), indicating a medium practical effect size for the mediation (Cohen, 1977). Similar reduction were observed for positive affect (ΔR² = 0.10, Cohen’s f² = 0.16), negative affect (ΔR² = 0.08, Cohen’s f² = 0.10), and depression (ΔR² = 0.07, Cohen’s f² = 0.08). These effect sizes, which are within the small-to-medium range, underscore the substantive relevance of the mediation pathways (see Table 3). Table S2 provides bootstrapping results with 95% confidence intervals, further corroborating the stability and robustness of the findings regarding the mediating effects.

Moderated mediating roles of family relationship

Using Model 8 in INDIRECT procedure (Hayes, 2013), a series of moderated mediation model analyses were conducted. First, the main effects of family relationships on three dimensions of attitudes to aging and four indicators of SWB were significant. Specifically, students in U3As with better family relationships exhibited more favorable attitudes towards aging (βPG = 0.19; βPL = 0.12; βPC = 0.18) and higher SWB (βLS = 0.31; βPA = 0.18; βNA = −0.07; βDepression = −0.04). Second, the interaction effect of DEP and family relationships significantly predicted both PG (β = 0.08) and PL (β = 0.09), but not PC (β = 0.03). Additionally, this interaction negatively predicted positive affect (β = −0.04), and positively predicted negative affect (β = 0.03) and depression (β = 0.06), although no significant effect was found for life satisfaction (β = −0.02). These results partly confirm Hypotheses 3a and 3b (see Table 4).

Conditional effects at three levels of family relationships (M ± 1 SD) further supported above finding, showing the effects of DEP on PG (βM-1SD = 0.40; βM = 0.43; βM+1SD = 0.47; all p < 0.001) and PL (βM-1SD = −0.23; βM = −0.19; βM+1SD = −0.14; all p < 0.001) were significant across all levels. Compared to individuals with lower level of family relationships, the enhancing effect of DEP on PG was more pronounced among those with higher level (slope difference Δβ = 0.07), whereas the mitigating effect of DEP on PL was weaker for those with higher level (slope difference: Δβ = 0.09) (see Tables 4 and S3 in Supplementary Materials). In addition, the moderating roles of family relationships on direct effects of DEP on PA, NA, and depression were significant. Compared to individuals with level of higher family relationships, the positive effect of DEP on PA was more pronounced among those with lower level (βM-1SD = 0.23 vs. βM+1SD = 0.19). Similarly, the mitigating effect of DEP on NA (βM-1SD = −0.07 vs. βM+1SD = −0.04;) and depression (βM-1SD = −0.07 vs. βM+1SD = −0.02) was more pronounced among individuals with lower level of family relationships (see Tables 4 and S4 in the Supplementary Materials).

Social-demographical variables, attitudes to self-aging, and SWB

The current study highlights the roles of demographic and socioeconomic factors as potential controlling confounders. Generally, regression analyses indicated independent and significant predictive effects of physical health and social participation on three dimensions of attitudes to aging and various indicators of SWB. Consistent with previous studies (Dai et al., 2013; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2000), physical and social functioning served as foundational for attitudes to aging and SWB.

Discussions

This study utilized a large representative sample of U3As’ students in China to examine the association between DEP and SWB, and the parallel mediating roles of three dimensions of attitudes to self-aging, and moderating roles of family relationships. Hypotheses were largely confirmed. The findings supplement evidences for positive roles of education participation and relevant mechanisms, and provide an insight and scientific basis for policymakers and managers to make measures for actively coping with issues of aging.

DEP and SWB

The DEP and its sub-dimensions were positively associated with SWB. Higher degree of participation in educational activities correlates with higher life satisfaction, fewer depressive symptoms and negative emotions, and more positive emotions. The DEP reflects older students’ enthusiasm and motivation for learning activities and organizations. They viewed participation in U3As as more than just an adornment for later life or merely better than nothing. Their high level of investment fully stimulated the social (e.g., peer interaction) and functional (e.g., cognitive stimulation) dimensions of late-life education. These findings resonate with activity theory (Lemon, Bengtson, & Peterson, 1972), which posits that sustained social and intellectual engagement in later life serves as a protective factor against age-related psychological decline. Researchers found that participation in elderly education affected SWB, and the longer the elderly invested energy and time in the same course or subject, the better their self-reported mental health and SWB (Leung & Liu, 2011; Narushima et al., 2018). Furthermore, a notable observation is that DEP exerted a stronger influence on positive dimensions of SWB (e.g., life satisfaction) than on negative ones (e.g., depressive mood), suggesting that U3As primarily function as a vehicle for well-being enhancement rather than solely as a buffer against distress. A higher level of involvement often means that its members derive a stronger sense of gain and achievement through systematic learning.

Mediating effect of attitudes to self-aging

Attitudes towards aging mediated the association between educational participation and SWB. Greater involvement in educational activities was associated with better perceived psychological growth, physical health, and fewer psychosocial losses–all related to diverse aspects of SWB. In general, positive aging attitude changes (e.g., psychological growth, physical change) were more significantly associated with positive sides of SWB (life satisfaction and positive affect) than negative ones (e.g., psychosocial loss); while negative aging attitude changes were more significantly associated with negative sides of SWB (negative affect and depression) than positive ones. Role theory posits that many older adults experience role loss after retirement, which may undermine social identity, diminish self-esteem, and heighten the risk of psychological imbalance (Hooyman & Kiyak, 1988). By participating in U3As, older adults can reclaim the constructive role of “student” or “learner”, thereby countering stereotypes of weakness and dependency while embracing new responsibilities that sustain meaning and well-being. The greater the involvement in organized educational activities, the more pronounced the impact of this renewed role becomes. The innovation theory of successful aging describes innovation as the process of self-preservation and the transformation of one’s past self in novel ways (Nimrod & Kleiber, 2007). Education for older adults serves to mitigate negative self-identities and counteract stereotypes associated with declines in physical and cognitive functioning. Through active learning—such as acquiring computer and Internet skills—older adults can transform a “conservative” and “incompetent” self-concept. These findings are consistent with prior research on psychosocial resources, which suggests that the benefits of lifelong learning contribute to the accumulation of resources that help older adults navigate life’s challenges. The greater these benefits, the more significant the positive shifts in perceptions of aging, which in turn influence mental health and SWB. Empirical studies grounded in self-determination theory indicate that participation in lifelong learning enhances fundamental needs (e.g., autonomy), thereby promoting mental health and SWB (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Zhang et al., 2024). Overall, the current findings extend existing theoretical frameworks by demonstrating how educational participation can reshape perceptions of aging, thereby exerting a multifaceted influence on subjective well-being.

Moderating effects of family relationships

Family relationships moderated both the direct and indirect associations between DEP and SWB. Specifically, the interaction between DEP and family relationships negatively predicted positive affect while positively predicting negative affect and depression; however, no significant association was found for life satisfaction. Overall, for students with poorer family relationships, educational participation played a more significant role in enhancing SWB. From another perspective, active educational engagement appears to compensate for the negative psychological effects of deficient family relationships. According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecosystem theory (1999), personal growth and development occur within a multilayered environment comprising micro-, meso-, exo-, and macro-systems. Ecosystems at these various levels—interacting both independently and jointly—affect the physical and mental health of elderly residents. Notably, both the family, as a core microsystem, and educational organizations, as external systems, collaboratively influence attitudes toward aging and SWB. The findings suggest that family support is not only a critical precondition for DEP but also moderates its impact on mental health outcomes. Consistent with ecosystem theory, which posits a functional ceiling for the benefits of an optimal environment (e.g., close family relationships), individuals with less supportive ecosystems, may experience greater benefits from educational participation (Stine-Morrow & Manavbasi, 2022). Thus, late-life learning activities can substantially offset the deficiencies associated with an inadequate living environment and limited resources.

The current study further emphasizes the roles of specific demographic and socioeconomic factors as covariates. Previous research has demonstrated that poor physical functioning and limited social participation frequently constrain attitudes toward aging and reduce educational engagement in later life (Dai et al., 2013; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2000; Steverink et al., 2001). According to resource theory, sufficient individual and social resources can enable individuals to compensate for losses associated with aging, thereby fostering more positive attitudes and perceptions of the aging process and ultimately influencing subjective well-being. Moreover, good health status—arguably the most critical prerequisite for meaningful engagement in educational activities and the effective assimilation of knowledge in U3As—constitutes an essential resource.

Theoretical and practical significances

This study offers several methodological and practical advantages. First, it employs a nationally representative sample of U3A students, thereby enhancing the generalizability of its findings. The sampling procedures carefully accounted for distributions by region, sex, age, and subject specialty, ensuring both national representativeness and comprehensive coverage. Second, whereas most research has primarily focused on the relationship between participation in educational activities and subjective well-being (SWB), the present study further investigates the association between the degree of participation among older adults and SWB by examining two dimensions of U3A engagement—sociality and functionality. This approach suggests that the quality of participation may be more influential than mere participation. Third, and most notably, by integrating mainstream theories in geriatric psychology—such as socioemotional selectivity theory, the selective optimization with compensation model, and ecosystem theory—this study examines the mental health effects of educational participation from the perspective of attitudes toward aging. This theoretical integration provides a deeper understanding of the positive impact of education on older adults. Notably, few studies have explored the mediating mechanisms underlying the positive effects of educational participation in later life on SWB, such as the acquisition of coping abilities (Field, 2009), the development of psychosocial resources (Hammond, 2004), and the fulfillment of basic psychological needs (Zhang et al., 2024). Preliminary investigations into these mechanisms also suggest that the family environment moderates the mental health benefits of educational participation in later life; for example, family relationships have been found to buffer the negative effects of low participation levels on SWB among older adults (Chen et al., 2021). Generally speaking, education in later life may enhance aging attitudes and future expectations by strengthening psychosocial resources, thereby promoting overall well-being and mental health.

In China, addressing population aging has become a national strategic priority, with older adult education recognized as a key measure. The current study offers several practical insights. First, developing educational programs for retirees and the elderly enables them to enjoy a high quality of life in later years, as illustrated by the slogan, “Establishing a U3A is tantamount to eliminating one elderly hospital” (Editorial Committee of the Blue Book of Education for Older Adults, 2021). Second, the findings indicate that the quality of participation in Universities of the Third Age (U3As) may be more important than mere participation regarding mental health and SWB. These insights imply that a high-quality educational institution should stimulate enthusiasm for learning, enhance a sense of belonging, and promote positive attitudes toward aging and SWB—critical indicators for evaluating U3A quality. Accordingly, administrators should endeavor to improve educational quality through various strategies and increase the appeal of U3As to older adults to maximize their positive effects on empowerment, capacity building, and well-being. Third, the exploration of moderating mechanisms revealed that enhancing the benefits of U3As requires coordinated efforts from grassroots governments, educational organizations, and families. While family support may reinforce the mental health benefits of education for older adults, organizational involvement can help offset the negative effects of poor interpersonal relationships on mental health. Consequently, U3A education is particularly recommended for socially isolated older adults to promote healthy aging.

Limitations

This study presents several limitations in its design and methodology. First, it relies primarily on cross-sectional design and observational data, rendering it impossible to infer causality or fully mitigate endogeneity bias. Consequently, selection effects and influence effects are confounded; while participation in educational programs may enhance mental health and SWB, older adults with superior physical and mental functioning are also more likely to engage with educational organizations. Future research could address this limitation by employing methods such as cross-lagged panel analysis with longitudinal data, causal inference via propensity score matching, and randomized experiments. Second, despite a large overall sample size, the majority of U3A participants were drawn from large and medium-sized cities. Organized educational institutions such as U3As are underdeveloped or absent in smaller cities and rural areas of China, which may account for the absence of observed cross-level differences in the primary variables. Moreover, attendance at U3As represents only one facet of older adults’ educational engagement; thus, examining the effects of informal and non-formal learning on SWB, alongside organized education, is warranted. Third, the DEP scale developed in this study is not yet internationally recognized or widely used, underscoring the need for more universally applicable instruments to evaluate U3A involvement across diverse cultural contexts. Finally, this study exclusively examined the moderating role of family relationships at the micro-ecosystem level, whereas other contextual levels—such as community, workplace, and urban environments—may also differentially influence the relationship between DEP and SWB.

Conclusions

This study employs a nationally representative sample of U3As to investigate the association between U3A involvement SWB, examining the mediating role of attitudes toward aging and the moderating effect of family relationships. First, the findings reaffirm the positive impact of later-life educational participation on SWB; specifically, greater educational engagement among older adults is associated with higher life satisfaction and positive affect, as well as lower negative affect and depressive symptoms. Second, attitudes toward aging—encompassing psychosocial loss, physical change, and psychological growth—mediate the relationship between U3A involvement and SWB. Increased participation in U3A programs tends to foster more positive self-perceptions regarding aging, thereby enhancing overall well-being. Third, family relationships moderate these associations, such that the beneficial effect of U3A involvement on SWB is more pronounced among individuals with less supportive family ties. These results provide robust empirical evidence and offer valuable insights for strategies aimed at actively addressing aging issues and improving the quality of later life.

Data availability

The data presented in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Bai X, Wu C, Zheng R, Ren X (2011) The psychometric evaluation of the satisfaction with life scale using a nationally representative sample of China. J Happiness Stud 12:183–197

Bronfenbrenner U (1999) Environments in developmental perspective: theoretical and operational models. In Friedman SL & Wachs TD (Eds.) Measuring environment across the life span. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999

Brother A, Kornadt E, Nehrkorn-Bailey A, Wahl W, Diehl M (2021) The effects of age stereotypes on physical and mental health are mediated by self-perceptions of aging. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 76:845–857

Bryant C, Bei B, Gilson K, Komiti A, Jackson H, Judd F (2012) The relationship between attitudes to aging and physical and mental health in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 24:1674–1683

Bužgová R, Kozáková R, Bobčíková K, Kubešová HM (2024) The importance of the university of the third age to improved mental health and healthy aging of community-dwelling older adults. Educ Gerontol 50:175–186

Camargo C, Lima-Silva B, Ordonez N et al. (2018) Beliefs, perceptions, and concepts of old age among participants of a university of the third age. PsyNeuro 11:417–425

Chen L, Song H, Dong J, Zhao H, Zhang Z (2021) The association and mechanism between organizational integration and depressive symptoms among students of the University of the Third Age. Stud Psychol Behav 19:706–713

Chen L, Song L, Zhang Z (2023) Senior education and mental health: empirical evidence, theory and mechanism. Chin J Clin Psychol 31:1257–1262

Cheng S, Fung H, Chan A (2009) Self-perception and psychological well-being: the benefits of foreseeing a worse future. Psychol Aging 24:623–633

Cheng S, Chan A (2005) The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in older Chinese: thresholds for long and short forms. Int J Geriatr Psych 20:465–470

Chua RL, de Guzman AB (2014) Effects of third age learning programs on the life satisfaction, self-esteem, and depression level among a select group of community dwelling Filipina elderly. Educ Gerontol 40:77–90

Chui E (2012) Elderly learning in Chinese communities: China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore. In G. Boulton-Lewis & M. Tam (Eds.) Active ageing, active learning: issues and challenges, Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. pp.141–161

Cohen J (1977) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Hillsdale, NJ

Cohn-Schwartz E, de Paula C, Fung H et al. (2023) Contact with older adults is related to positive age stereotypes and self-views of aging: The older you are the more you profit. J Gerontol B 78:1330–1340

Coskun Y, Demirel M (2010) Lifelong learning tendency scale: the study of validity and reliability. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 5:2343–2350

Cybulski M, Cybulski Ł, Cwalina U et al. (2020) Mental health of the participants of the third age university program: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry 11:656

Dai B, Zhang B, Li J (2013) Protective factors for subjective well-being in Chinese older adults: the roles of resources and activity. J Happiness Stud 13:1225–1239

Diehl M, Wahl H, Barrett E et al. (2014) Awareness of aging: theoretical considerations on an emerging concept. Dev Rev 34:93–113

Diener E, Suh M, Lucas E, Smith L (1999) Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull 125:276–302

Dumitrache C, Rubio L, Cordon-Pozo E (2019) Successful aging in Spanish older adults: the role of psychosocial resources. Int Psychogeriatr 31:181–191

Editorial Committee of the Blue Book of Education for older adults (2021) Research report on the development of education for the elderly in China. Contemporary China Press, Beijing

Fei G (2020) A philosophical answer to the question “what is the name of education for the elderly?” See Lu J & Zhang B (Ed.) The center for epidemiologic studies depression scaley, Nanjing: Jiangsu People’s Publishing House, pp. 43−56

Fei L, Shen Q, Zheng Y, Zhao J, Jiang S, Wang L, Wang D (1991) Preliminary evaluation of Chinese version of FACES and FES: Comparison of normal families and families of schizophrenic patients. Chin Ment Health J 5:198–202

Formosa M (2014) Four decades of universities of the third age: past, present, future. Ageing Soc 34:42–66

Formosa M (2021) Manifestations of internalized ageism in older adult learning. Univ Tor Q 90:169–182

Field J (2009) Good for your soul? adult learning and mental well-being. Int J Lifelong Educ 28:175–191

Gierszewski D, Kluzowicz J (2021) The role of the University of the third age in meeting the needs of older adult learners in Poland. Gerontol Geriart Edu 42:437–451

Gallo C, Matthews A (2003) Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: do negative emotions play a role? Psychol Bull 129:10–51

Gao L, Cheng C, Wang D, Liu C (2024) The pattern of gains derived from the University of the third age and its relationship with attitudes toward aging: the success of selective engagers. J Adult Dev https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-024-09498-3

Gao L, Laidlaw K, Wang D (2024) A brief version of the attitudes to ageing questionnaire for older Chinese adults: development and psychometric evaluation. BMC Psychol 12:181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01691-z

Guo J, Yang F (2025). Adult education and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study in China. J Gerontol B 80:gbaf060. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaf060

Gunuc S, Odabasi F, Kuzu A (2014) Developing an effective lifelong learning scale (ELLS): study of validity & reliability. Educ Sci 39:244–258. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262105268

Hair F, Anderson E, Tatham L, Black C (1998) Multivariate data analysis, 5th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, pp 730

Holtfreter K, Reisig D, Turanovic J (2017) Depression and infrequent participation in social activities among older adults: the moderating role of high-quality familial ties. Aging Ment Health (4):379–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1099036

Hammond C (2004) Impacts of lifelong learning upon emotional resilience, psychological and mental health: fieldwork evidence. Oxf Rev Educ 30:551–568

Hardy M, Oprescu F, Millear P et al. (2017) Baby boomers engagement as traditional university students: benefits and costs. Int J Lifelong Educ 36:730–744

Hayes F (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 1st edn. The Guilford Press, pp 507

Hooyman NR, Kiyak HA (1988) Social gerontology: a multidisciplinary perspective. Allyn and Bacan, Inc

Isla R, Andrew S (2018) Is the relationship between subjective age, depressive symptoms and activities of daily living bidirectional? Soc Sci Med 214:41–48

Jung S, Cham H, Siedlecki L, Jopp S (2021) Measurement invariance and developmental trajectories of multidimensional self-perceptions of aging in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol B 76:483–495

Ko P (2020) Investigating social networks of older Singaporean learners: a mixed methods approach. Educ Gerontol 46:207–222

Laidlaw K, Power J, Schmidt S, WHOQOL-OLD Group (2007) The attitudes to ageing questionnaire (AAQ): development and psychometric properties. Int J Geriatr Psych 22:367–379

Lang R, Carstensen L (2002) Time counts: future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychol Aging 17:125–139

Lemon W, Bengtson L, Peterson A (1972) An exploration of the activity theory of aging: activity types and life satisfaction among in-movers to a retirement community. J Gerontol 27:511–523

Leung D, Liu B (2011) Lifelong education, quality of life and self-efficacy of Chinese older adults. Educ Gerontol 37:967–981

Lewis L (2014) Responding to the mental health and well-being agenda in adult community learning. Res Post Compuls Educ 19:357–377

Liang Y, Zhu D (2015) Subjective well-being of Chinese landless peasants in relatively developed regions: measurement using PANAS and SWLS. Soc Indic Res 123:817–835

Liu J, Wei W, Peng Q, Guo Y (2021) Does perceived health status affect depression in older adults? roles of attitude toward aging and social support. Clin Gerontol 44:169–180

Liu Y, Duan Y, Xu L (2020) Volunteer service and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults: the mediating role of health. Soc Sci Med 265:113535

Maulod A, Lu S (2020) I’m slowly ageing but I still have my value”: Challenging ageism and empowering older persons through lifelong learning in Singapore. Educ Gerontol 46:628–641

Meyer-Wyk F, Wurm S (2024) The role of social network diversity in self-perceptions of aging in later life. Eur J Ageing 21:20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-024-00815-z

Mirowsky J, Ross E (2008) Education and self-rated health: cumulative advantage and its rising importance. Res Aging 30:93–122

Narushima M, Liu J, Diestelkamp N (2013) The association between lifelong learning and psychological well-being among older adults: implications for interdisciplinary health promotion in an aging society. Act Adapt Aging 37:239–250

Narushima M, Liu J, Diestelkamp N (2018) Lifelong learning in active ageing discourse: its conserving effect on wellbeing, health and vulnerability. Ageing Soc 38:651–672

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021) Major figures on 2020 population census of China. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/ Accessed 11 May 2021

Nimrod G, Kleiber D (2007) Reconsidering change and continuity in later life: towards an innovation theory of successful aging. Int J Aging Hum Dev 65:1–22

Noble C, Medin D, Quail Z et al. (2021) How does participation in formal education or learning for older people affect wellbeing and cognition? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Gerontol Geriatr Med 7:1–15

Park S, Badham S, Vizcano-Vickers S, Fino E. (2024) Exploring older adults’ subjective views on ageing positively: Development and validation of the Positive Aging Scale. Gerontologist 64:gnae088 https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnae088

Park S, Jang Y, Lee S, Haley E, Chiriboga A (2013) The mediating role of loneliness in the relation between social engagement and depressive symptoms among older Korean Americans: do men and women differ? J Gerontol B Psychol 68:193–201

Pinquart M, Sörensen S (2000) Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective wellbeing in later life: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging 15:187–224

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depressive symptom scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas 1:385–401

Ristl C, Korlat S, Rupprecht FS, Burgstaller A, Nilitin J (2025) Self-perceptions of aging and social goals. Psychol Aging 40:413–420

Roberts SC (2021) ‘Our members are growing up!’ contradictions in ageing talk within a lifelong learning institute. Ageing Soc 41:836–853

Romaioli D, Contarello A (2021) Resisting ageism through lifelong learning. Mature students’ counter-narratives to the construction of aging as decline. J Aging Stud 57:100934

Ryan M, Deci L (2017) Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press, New York

Schoultz M, Öhman J, Quennerstedt M (2020) A review of research on the relationship between learning and health for older adults. Int J Lifelong Educ 39:528–544

State Council of China (2016) Plan for the development of education for the elderly (2016-2020). http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-10/19/content_5121399.htm Accessed 5 May 2016

State Council of China. (2022). The 14th five-year plan for the development of the national cause for aging and the service system for the elderly. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-02/21/content_5674877.htm Accessed 21 Feb 2022

Steverink N, Westerhof J, Bode C, Dittmann-Kohli F (2001) The personal experience of aging, individual resources, and subjective well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol 56:364–373

Stine-Morrow L, Payne R, Robert W et al. (2014) Training versus engagement as paths to cognitive enrichment with aging. Psychol Aging 29:891–906

Stine-Morrow L, Manavbasi IE (2022) Beyond “use it or lose it”: the impact of engagement on cognitive aging. Annu Rev Del Psychol 4:319–352

Sung P, Chia A, Chan A, Malhotra R (2023) Reciprocal relationship between lifelong learning and volunteering among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol 78:902–912

Waller R, Hodge S, Holford J, Milana M, Webb S (2018) Adult education, mental health and mental wellbeing. Int J Lifelong Educ 37:397–400

Wang N, Xu H, Dhingra R et al. (2025) The impact of later-life learning on trajectories of cognitive function among U.S. older adults. Innov Aging 9:igaf023

Watson D, Clark A, Tellegen A (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1063–1070

Withnall A (2010) Improving learning in later life. Routledge, London

World Health Organization (2015) World report on ageing and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2015(online). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186463 Accessed 29 Sept 2025

World Health Organization (2002) Active ageing: a policy framework. Adv Gerontol 11:7-18

World Health Organization (2020) Proposal for Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021-2030). https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/decade-of-healthy-ageing-plan-of-action Accessed 20 Dec 2020

Xu W, Wu Y, Lin Y et al. (2010) The effect of participating in learning of University of Third Age on cognitive function in the elderly. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci 19:1120–1122

Zhao X, Chui E (2019) Chapter 13: The development and characteristics of Universities of the third age in mainland China. In: Formosa, M ed. The university of the third age and active ageing: European and Asian-Pacific perspectives. Springer. pp. 157−168

Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Du H, Adelijiang M, Zhang J (2024) Educational quality of the University of the third age and subjective well-being: based on a perspective of self-determination. Appl Res Qual Life 19:2103–2123

Zielińska-Więczkowska H, Muszalik M, Kędziora-Kornatowska K (2012) The analysis of aging and elderly age quality in empirical research: data based on university of the third age (U3A) students. Arch Gerontol Geriat 55:195–199

Zielińska–Więczkowska H, Kedziora-Kornatowska K, Ciemnoczoɫowski W (2011) Evaluation of quality of life (QoL) of students of the University of third age (U3A) on the basis of socio-demographic factors and health status. Arch Gerontol Geriat 53:e198–e202

Zielińska-Więczkowska H, Sas K (2020) The sense of coherence, self-perception of aging and the occurrence of depression among the participants of the university of the third age depending on socio-demographic factors. Clin Inter Aging 15:1481–1491

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grants of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 71774157); Fund of CAS Engineering Laboratory for Psychological Service (grant number KFJ-PTXM-29); and Open Research Fund of the CAS Key Laboratory of Behavioral Science, Institute of Psychology (grant number Y5CX052003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. designed the project and main conceptual ideas. Z.Z., Z.Y., D.H., and M.A. undertook the data collection and statistical analysis. Z.Z. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained on Marth 12, 2017 (No. H17030) from the Institutional Review Board of Institute of Psychology of Chinese Academy of Sciences. The validity period of the ethical approval spans from March 2017 to December 2022, which aligned with the funding program’s implementation timeline. All procedures strictly adhered to ethical guidelines and regulations governing research involving human participants, including the principles outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Special emphasis was placed on safeguarding participants’ rights, safety, and well-being, while ensuring scientific rigor throughout the study.

Informed consent

Informed consents were obtained from all participants on October 10, 2021, prior to data collection. Participants were fully informed about the research objectives, their voluntary participation (including the right to withdraw at any time without penalty), the anonymization of data, and the exclusive use of collected information for academic purposes. No personally identifiable information was collected or disclosed during the research process.

AI disclosure statement

During the process of drafting, revising, and polishing the manuscript, we did not employ any AI technology as an assistive tool.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Zhao, Y., Du, H. et al. The degree of educational participation in later life and subjective well-being in China: Based on attitudes to self-aging perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1793 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06023-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06023-z