Abstract

Cumulative evidence has shown that Virtual Reality (VR) can effectively induce human well-being, including Subjective well-being and Psychological well-being. This scoping review aims to explicate and theorise how and why VR leads to human well-being through a scoping review of 18,008 articles and coded 187 articles in the final dataset. Three key components in this mechanism—VR illusion (Place Illusion, Plausibility Illusion, Virtual Body Ownership), stimulus effect on well-being, and well-being dimension—were coded, and the causation between nodes was analysed, among these experiments. Thirty-two effects were identified, such as empathy concern induction, and stress reduction. The results show that Place Illusion is primarily used to enhance subjective well-being by immersing individuals in restorative and awe environments. In contrast, Plausibility Illusion and Virtual Body Ownership are more commonly linked to psychological well-being, helping reduce the psychological distance to concerns and leveraging the Proteus Effect (i.e., effects of the embodied virtual body on self) and Embodied Experience. Illusion elicitation techniques associated with each illusion were categorised and theories that are commonly applied were organised. With consideration of individual differences, the Virtual reality-InducE Well-being (VIEW) model, a four-step flowchart, was developed. The model illustrates that through the design of VR elements such as the environment, interaction, and virtual body, it can effectively lead to three illusions, which in turn lead to various routes (i.e., affective, cognitive, and physiological), ultimately resulting in subjective and/or psychological well-being. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As human well-being has become a key issue from the global perspective (World Economic Forum, 2022), there is an imperative need for our understanding of various technology-related techniques for well-being induction. Specifically, researchers look at how immersive media, virtual reality, can effectively elicit well-being. Cumulative evidence across disciplines has shown that virtual reality (VR) can effectively induce well-being, including Positive Affect, Positive Relations with Others, and Personal Growth (Anderson et al., 2017; Cebolla et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2020). A comprehensive theoretical framework is needed to explain how the unique elements of immersive media induce well-being. Scholars have extensively theorised how people use 2D media to manage mood (Reinecke, 2016), fulfil intrinsic needs (Peng et al., 2012; Tamborini et al., 2010), and reflect on life’s purpose (Oliver & Bartsch, 2010). However, current theories (Oliver et al., 2021; Vorderer & Reinecke, 2015) mostly focus on 2D media (or are based on 2D media), and the unique affordances of immersive media require advanced theoretical development.

In Virtual Reality (VR), an immersive medium, three distinct illusions set it apart from 2D media: Place Illusion, Plausibility Illusion, and Virtual Body Ownership (Slater, 2009). Unlike 2D media, where users must identify with or mentally transport themselves into characters, events, and environments (Tal-Or & Cohen, 2010), VR allows users to become the characters, experience the events, and exist within the environments (Slater et al., 2022). Scholars leveraged these design traits to immerse users in virtual environments for relaxation (Li et al., 2021), express nonverbal cues through natural body and facial tracking (Lin et al., 2024; Maloney et al., 2020), and experience various identities for environmental mastery and personal growth (Sundar et al., 2017; Yee & Bailenson, 2007). These pieces of evidence indicate that virtual reality is effective in inducing well-being. However, how virtual reality induces well-being still requires theoretical advancement supported by the abundant evidence in these empirical studies, for scientists and designers to further leverage the mechanisms for the greater good.

We scope three decades of literature to review what VR illusions and effects on well-being the researchers employed to elicit well-being, and what dimensions of well-being are induced. We analyse the entire routes of our codes (VR Illusion → Stimulus’s Effect on Well-being → Well-Being Dimension) to contextualise the mechanisms of VR inducing well-being. We reviewed the construct of well-being in different fields, specifically focusing on Diener’s (1984) and Ryff’s (1989) subjective and psychological well-being framework, explicate Slater’s VR Illusion framework, outline guiding questions, present results, propose a four-step theoretical model, and develop the VR InducEs Well-Being model (VIEW).

Theoretical foundation

Well-being: diversely defined

The term well-being is prevalent in Psychology, Medicine, and Economics literature, but lacks a universal definition.

In Psychology, well-being comprises subjective well-being rooted in hedonia and psychological well-being rooted in eudaimonia (Diener, 1984; Ryff, 1989). Hedonia and eudaimonia are two perspectives of viewing human well-being. The hedonistic perspective is “generally defined as the presence of positive affect and the absence of negative affect”, while the eudaimonic perspective focuses on “living life in a full and deeply satisfying way” (Deci & Ryan, 2008). Through operationalisation (e.g., Ryff, 1989; Watson & Clark, 1994), Subjective well-being (SWB) includes Pleasant Affect, Unpleasant Affect, Life Satisfaction, and Domain Satisfaction (Diener et al., 1999), while Psychological well-being (PWB) adopts Self-acceptance, Positive Relations with Others, Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, Purpose in Life, and Personal Growth (Ryff, 1995; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Ryff, 2013).

In SWB’s dimensions, Pleasant Affect includes emotions such as joy and happiness, while Unpleasant Affect includes guilt, stress, and more. Life Satisfaction and Domain Satisfaction involve subjective evaluations of one’s status but operate oppositely (Tov, 2018). Life Satisfaction evaluates life as a whole (top-down), while Domain Satisfaction is achieved by meeting respective realms in life (bottom-up; e.g., health and safety).

In PWB’s dimensions, Self-acceptance reflects an individual’s authentic and accepting attitude toward one’s moment-to-moment experiences (Hayes et al., 2012), both positive and negative, independently of external judgements or pressures (Ellis, 2005); Positive Relations with Others involve cultivating trust, warmth, and openness in everyday relationships; Autonomy reflects the ability to resist social pressures and make decisions independently; Environmental Mastery depicts one’s ability to control opportunities to satisfy personal values; Purpose in Life describes having determinations and meanings in life; Personal Growth represents seeing oneself as having great potential and being a work in progress. Both SWB and PWB are well-established constructs with widely cited scales (Diener et al., 1985; Kjell et al., 2016; Su et al., 2014).

We here acknowledge Medicine and Economics’ Well-being definitions but apply Psychology’s framework due to the following reasons. Medicine focuses on (a) physician burnout and (b) patient health conditions (Dunn et al., 2008; Kaplan et al., 1997). Economics scholars focus on tangible factors related to material conditions (Oswald & Wu, 2010; Yeh et al., 2020). Although well-being’s definition varies across disciplines, most generally used VR applications (such as Wander VR, BRINK Travelers, Beat Saber, and VRChat) centre on influencing psychological aspects among ordinary users rather than focusing on medical purposes or evaluating material resources. Hence, we conduct this scoping review based on the established framework of SWB and PWB.

Unique VR illusions

Slater (2009) theorised that in immersive media such as virtual reality, users perceive three key illusions: Place Illusion (PI), Plausibility Illusion (PSI), and Virtual Body Ownership (VBO). First, PI refers to feeling physically present in virtual environments, despite knowing that one is not. This concept resembles the self-location construct in “presence” in Communication (Nakul et al., 2020; Hartmann et al., 2015). For instance, when users rise on a virtual elevator, they may forget that they are actually standing on solid ground and believe that they are at a high altitude (Lin, 2017). Second, PSI involves feeling that “what is apparently happening is really happening” (Slater, 2009), despite knowing they are not. For example, although players know they are fighting virtual zombies, they vividly sense zombies’ attacks and perceive these interactions as “really happening” (Lin et al., 2017). PSI is closely linked to “possible actions” in the presence literature in Communication (Nakul et al., 2020; Hartmann et al., 2015). PI and PSI construct the perception of presence, and merely visual manipulations can elicit presence. Third, VBO describes the experience of embodying an avatar as if the virtual body is one’s own (Slater, 2009). This allows users to see and control their virtual bodies with synchronous real-body movements, creating the illusion of body ownership. Multiple senses, adding smell, touch, and taste to visual, can further increase presence (Ferrise et al., 2024) and embodiment.

Although PI and PSI both contribute to spatial presence (Slater et al., 2022), from the design perspective, we believe it is essential to differentiate the two in this scoping review for the following reasons. Despite that Slater et al. (2022) implied that PI and PSI “make up” presence (p. 3), and together referred to how people respond to “immersion” (p. 10), they also illustrated that PI and PSI “are conceptually distinct and can be considered as orthogonal axes” (p. 3; see also p. 1 and p. 9), and are “logically separable concepts in that it is possible for PI to occur independently of PSI and vice versa” (p. 9). PI is part of what VR might occur by default, while PSI requires deliberate design (Slater et al., 2022), making it important to explicate the different mechanisms by which VR design/stimuli influence human well-being. Therefore, from the experiment/developer viewpoint, it is essential to discuss and analyse PI and PSI separately, even if they strongly influence each other and contribute together to participants’ spatial presence.

Although the VR illusions were theorised as passive phenomena (i.e., users experience PI passively as soon as they enter an immersive virtual environment), we adopt the VR illusion framework from a design perspective in which these three illusions can be actively and intentionally elicited through content design (environment, interactions, and events, and virtual bodies). PI is employed when designers aim to have users be virtually immersed in designed environments (e.g., Wander VR, BRINK Travelers), PSI is employed when they seek to create first-hand experience simulations (e.g., Beat Saber, FitXR) of processes and outcomes, and VBO is employed when they aim to have users embody another identity (e.g., VRChat, Horizon) from a first-person view. Similarly, scientists and designers design elements in VR to induce these illusions for desired outcomes. Respectively, designers manipulate the virtual environment in the 360-degree and immersive experience to induce PI (Chirico et al., 2018); interactions and events are designed to induce PSI (Lin et al., 2024), and virtual bodies are designed to induce VBO (Ahn et al., 2016). Hence, even though VR experiments lack users’ activeness in decisions of actions (actions in VR experiments are often scripted or pre-programmed), we theorise that through the design elements of the environment, interactions, and virtual body, these three illusions are essential for designers and developers to consider when designing content for specific outcomes.

Relevant reviews of VR

Very few reviews directly focus on unique VR traits on well-being, especially on SWB and PWB dimensions. Existing review articles on VR scholarship have illustrated VR’s positive impacts on society, attributed to its unique illusions. Existing VR review articles have focused on specific diseases (e.g., Farashi et al., 2024; Faria et al., 2023; Tokgöz et al., 2022), treatment evaluations (e.g., Caponnetto et al., 2021; Lebiecka et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021), or particular psychological phenomena (e.g., Praetorius & Görlich, 2020; Ratan et al., 2020). In recent years, there have been some VR reviews focusing on specific VR design (Frost et al., 2022) or mood management inductions through VR for well-being (Di Pompeo et al., 2023). For example, Frost et al. (2022) focus on how VR environments influence psychological well-being and found that VR nature exposure can decrease negative affect.

Among existing VR review articles, a notable contribution comes from Di Pompeo and his colleagues (2023), who conducted a related yet different systematic review. Their analysis spanned a wide array of pleasant affect-inducing methods, such as static images, music, and writing interventions, implying that techniques involving VR were more effective in promoting well-being and health. As human well-being has become a key issue from the global perspective (World Economic Forum, 2022), their review underscores the imperative need for our scoping review, delving into the evidence of how VR interventions can induce well-being for society.

Guiding research questions

Scholars have found VR more efficient than 2D media in eliciting well-being (Breves & Heber, 2020; Di Pompeo et al., 2023; Jo et al., 2021). However, the mechanisms and associations between VR exposure and induced well-being dimensions in existing experiments have not been explicated. To theorise the link, we propose the following guiding questions for our scoping review:

-

1.

How does current research design VR stimuli (including environment, interactions, and virtual body) to induce PI, PSI, and VBO?

-

2.

What are the effects of PI, PSI, and VBO, and how do they contribute to well-being?

-

3.

Which well-being dimensions does VR predominantly induce? Conversely, which dimensions are understudied?

-

4.

What theoretical approaches do PI, PSI, and VBO research employ?

Method

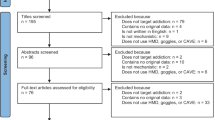

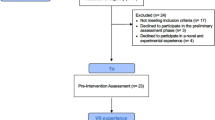

Our scoping review follows the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Peters et al., 2020; Tricco et al., 2018). We conducted a search on five databases for relevant publications and performed screening, coding, and coder cross-examinations to explore how VR can induce human well-being. The entire process was carried out by three trained coders (the latter first author, third, and fourth authors) between January 23rd and June 30th, 2024. The detailed procedure is outlined below.

Search strategy

We used Web of Science, MEDLINE, Academic Search Complete, Communication & Mass Media Complete, and Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts as our databases, initially collecting data on January 23rd, 2024, with a second round collection on June 4th, 2024, to include year-to-date publications. In line with Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) recommendations for scoping review search strategies, our goal was to achieve broad coverage of VR publications based on Slater’s VR illusion framework (2009, 2022). Hence, we expanded the key concepts of PI, PSI, and VBO with related keywords (listed below). We used the Topic field in Web of Science and Subject Terms in other databases as our search guide, collecting all publications that matched both “virtual reality” and “[keyword]” using the “AND” Boolean operator. The outputs for keywords within the same illusion category were then combined using the “OR” Boolean operator. We limited our search to peer-reviewed original studies (i.e., empirical studies with original data) in English, excluding review articles. For PI, we used keywords: place illusion, presence, place, space, spatial, immersive, immersion, environment, awe, and scene, yielding a total of 7771 publications. For PSI, the keywords included plausibility illusion, plausible, plausibility, implausible, simulation, interaction, credible, and event, resulting in 5126 publications. For VBO, our keywords included embodiment, embody, body, ownership, own, character, self, proteus, and avatar, resulting in 4659 publications. The second round of search resulted in adding 443 publications in 2024. To ensure thoroughness, our research process also involved the “snowball” technique by reviewing additional sources cited within the articles and existing studies on the impact of VR on well-being (Jaskiewicz & Tulenko, 2012; Pham et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2024). This strategy enabled the authors to gather comprehensive works, aiming to include relevant studies that might not have been captured in the initial database search (Rehman et al., 2025). In total, our database comprises 18,008 publications.

Screening procedure

Three reviewers received training to evaluate publications based on their titles and abstracts, following predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Articles were included if they met two conditions simultaneously: (1) they used at least one VR stimulus in their experiment, and (2) their dependent variables were related to at least one component of SWB or PWB. Conversely, articles were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) studies which did not use any VR stimulus in their experiment, which means that research had to employ VR headsets or immersive cave VR, (2) the VR stimulus did not evoke or measure at least one illusion of PI, PSI, or VBO (e.g., use VR headset for 2D display– Virtual Desktop), or (3) their dependent variables were unrelated to SWB or PWB. For instance, articles comparing users’ perceptions of realness in different immersive media (e.g., 3D versus 360° videos) or studies assessing patients’ physical mobility after VR-based medical treatments or rehabilitation were excluded. Additionally, (4) articles focused on niche topics rather than general use, such as spider phobia, specific diseases, or tourism and business promotion, were also excluded from the dataset. Our screening approach hopes to minimise potential topic-, group-, or location-related bias and contributes to understanding VR effects on well-being in a way that is more applicable to general VR usage.

In line with PRISMA-ScR’s recommendation for conducting an inter-reviewer reliability pilot test (Tricco et al., 2018), three reviewers carried out a nominal dichotomous pilot test to achieve the recommended 70–80% agreement threshold. A random sample of 50 article titles and abstracts was selected from the database, and the reviewers screened them according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inter-reviewer reliability was measured using Krippendorff’s alpha. Initially, Krippendorff’s alpha was low (α = 0.43), prompting the reviewers to thoroughly review the pilot results, discuss their assessments, and then conduct a second pilot test. In the second round, Krippendorff’s alpha improved, reaching 0.86, indicating strong and ideal inter-reviewer reliability (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007). The three reviewers then screened the entire database, with the former first author serving as the verifier throughout the screening process. Any uncertainties or questions were discussed in detail until a consensus was reached on article inclusion. Ultimately, 187 articles were included in our final dataset after the full procedure of screening, full-text retrievals, and coding (see Supplementary Table S1 online).

Article coding

Due to the absence of established frameworks for VR illusion elicitation techniques and effects on well-being (and our purpose of the current review is to develop one from existing empirical studies), we adopted an inductive coding approach (Pollock et al., 2023), mainly thematic analysis (Nowell et al., 2017). “An inductive approach may be useful where there is a dearth of evidence on the topic, or the goal is to develop or inform a conceptual framework or theory” (Pollock et al., 2023, p. 526). Thematic analysis (Nowell et al., 2017) focuses on discerning and interpreting the themes that emerge from data, offering flexibility and depth in understanding content. It follows a clear process from coding to theme development and is exemplified by countless studies that have illuminated participants’ experiences and meanings through well-crafted. Relational analysis (Robinson, 2011), by contrast, illuminates the relationships among concepts, mapping how ideas co-occur and interlink to form larger structures of meaning.

Following the above approaches, firstly, we reviewed the eligible articles to develop our initial codebook based on the thematic analysis, covering several key components: (1) SWB and PWB, (2) SWB and PWB well-being subdimensions, (3) stimulus dynamics Footnote 1 (self, interpersonal, intergroup, non-human, and environment), (4) illusion (PI, PSI, and VBO) elicitation techniques (how did researchers design to elicit these illusions), and (5) stimulus effects on well-being. Secondly, the coders retrieved the articles together and completed the coding together through discussion. Hence, each code is based on three coders’ consensus. During the process, the codebook structure was continually discussed and refined to ensure the nuance of VR effects was fully recorded but not overscattered (Thomas, 2006). After the codebook was determined (see Table 2), all coders reexamined all included articles together again to ensure no code was missed due to codebook refinement. Ultimately, we identified 32 distinct effects and categorised them into seven themes (Empathy Concern Induction, Prosocial Behaviour Induction, Problem-solving Enhancement, Self-efficacy Induction, Positive Affect Induction, Negative Affect Reduction, and Others). In addition, we identified three illusion elicitation techniques designed for PSI elicitation (Interaction and Activity, Bystander Observation, and Time Travel) and two illusion elicitation techniques for VBO (Embody Self and Embody Others). Since a detailed analysis of VR scenery styles was beyond the scope of our study, we labelled scenes descriptively (e.g., beach, forest, biophilic environment) and identified 20 different styles without further categorisation. Lastly, we also note the theoretical background of each included study if the authors mentioned in their main text (e.g., “Our experimental design is based on [theory].” Available upon request to authors). Figure 1 outlines the screening procedure and Supplementary Table S1 online provides the full coding result of 187 eligible articles.

Then, we coded the relationships between these categories based on the relational analysis (Robinson, 2011) to understand how different stimuli elicit VR illusions, through what effect, and to induce what well-being dimensions. The coloured lines indicated the relational linkages of these themed categories, and Figs. 2–5 illustrated our results of the relationships of these concepts.

The chart illustrates the proportion of various VR illusions that trigger 32 effects, along with the mechanisms that influence 10 subdimensions of well-being. Comparisons can be drawn based on the thickness of the nodes and lines between each stage, as well as the visibility of colours, which represent the extent of VR illusion usage in well-being research. The weighted count in the chart reflects the number of coded effects across 187 eligible publications, rather than the number of publications themselves. (PI: Place Illusion; PSI: Plausibility Illusion; VBO: Virtual Body Ownership).

The chart illustrates the proportion of Plausibility Illusion (PSI) that triggers 32 effects and its mechanism (coloured) for inducing 10 subdimensions of well-being. Scholars primarily use PSI to enhance empathy concern, reduce bias, and promote prosocial behaviour, all of which foster positive relationships with others and contribute to PWB.

The chart illustrates the proportion of Virtual Body Ownership (VBO) that triggers 32 effects and its mechanism (coloured) for inducing 10 subdimensions of well-being. Very similar to PSI’s route map (Fig. 4), scholars primarily use VBO to enhance empathy concern, reduce bias, and promote prosocial behaviour, all of which foster positive relationships with others and contribute to PWB.

Lastly, we stress that among all VR stimuli, there are many situations where multiple illusions (PI, PSI, and VBO) are elicited in the experiments. However, since (to some extent) one can argue that all experimental stimuli evoke certain levels of each illusion, we coded the illusions based on whether the experiment’s purpose is strongly related to that specific illusion. For example, in Seinfeld et al. (2018), although the illusion of “being in a house” is elicited by the stimulus, the environment/space design is not the main focus of the experiment. The main focus is on having participants experience being offended while embodying someone else’s identity. Therefore, we do not code PI for this publication, since PI is neither manipulated nor the main focus of the study. We code both PSI and VBO for this experiment, as the interaction with the defender and the experience of being in another’s body are critical aspects of the experimental design that impact the study’s dependent variables. Same as all other codes, all uncertainties or questions were discussed in detail until a consensus was reached.

Results

We structure this results section by addressing the guiding research questions in order and discussing PI, PSI, and VBO separately. First, we analyse how VR researchers applied PI, PSI, and VBO, and categorise their illusion elicitation techniques. Secondly, we report the coding results to explicate how different VR illusions were employed to stimulate various effects and induce specific well-being dimensions, addressing the second and third guiding research questions. In addition, we also organised what measurements and scales VR scholars tend to employ when measuring variables that relate to SWB and PWB (Table 3). Lastly, we organise the existing theories that scholars primarily base on to conduct VR experiments according to different VR illusions.

Among the 187 eligible articles, we identified 80 that applied PI, 113 that applied PSI, and 84 that applied VBO. Please note that one study may apply one or multiple illusions (see supplementary material for details). Of 10 well-being subdimensions, Positive Relations with Others (99) is the most frequently induced one, while Life Satisfaction (1) is the least explored (see Fig. 2).

PI: stimulus techniques, mechanisms, and theories

Two categories of PI stimuli emerged—one has participants exposed to the virtual environment without a narrative, while the other does.

PI stimuli without narratives

Most PI stimuli focus on natural environments, such as forests and oceans, and researchers compare these to urban, other nature, and the physical world. Natural settings are more effective than urban ones at reducing stress, fatigue, and tension while promoting calmness, self-efficacy, and future nature engagement (Leung et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Schebella et al., 2019; Theodorou et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2018). For example, Pennanen et al. (2020) investigated sunny and rainy natural environments and their impact on participants’ positive emotions and desire for healthy food. Weeth et al. (2017) experimented with hot and cold virtual environments, discovering that both interventions reduced pain intensity. Overall, studies underscore the benefits of PI in creating natural experiences.

In contrast to nature-related PI, although many urban environments are found less beneficial, scholars explore man-made sites’ positive influence. For example, Starr et al. (2019) had female participants visit their future offices with pSTEM professionality and lowered their stereotype threat. Scholars also experimented with biophilic architects and discovered that man-made environments with higher greenery improve emotional health and reduce stress (Fu et al., 2022; Xiaoxue & Huang, 2024; Yin et al., 2018), highlighting the great potential in enhancing well-being.

Scholars use PI to explore how awe in VR benefits humans. For instance, Chirico et al. (2018) designed awe-eliciting VR environments based on components of vastness and the need for accommodation. Kahn and Cargile (2021) utilised the overview effect in VR to replicate prosocial tendencies induced by awe (White, 1987). Lin et al. (2024) immersed participants in a supernatural experience in a gigantic Travis Scott VR concert and found that supernatural awe not only produced feelings of vastness (led to prosocial intentions similar to natural awe) but also led to self-improvement intentions, enjoyment, and arousal. These studies show that PI in VR effectively elicits awe.

Although there are far fewer studies, some scholars have begun to investigate how surreal environments influence human experience. Han et al. (2024) examined the spatial dimensions of VR environments featuring ultra-high ceilings and expansive spaces, finding that participants reported greater awe (i.e., positive affect under subjective well-being) and maintained higher levels of social attention. Horky et al. (2023) had participants play economic dictator games in a surreal cosmos, which led to fairer outcomes than the realistic office condition. Although surreal environments are less prevalent across our data, early studies show potential.

PI stimuli with narratives

Unlike sole PI, PI with narrative guides participants’ attention and examines the narratives’ impact on their well-being, such as building positive relationships with others regarding racial issues or changing their self-concept and leading to pro-environmental or pro-social behaviour. These narratives cover war, disaster, environmental issues, and health. For example, both Shin (2018) and Barreda-Ángeles et al. (2020) placed participants in wars to test how PI with narrative affects empathy. Ma (2020) presented the Nyarugusu Refugee Camp and discovered that enhanced psychological transportation reduces counterarguing and stimulates prosocial attitudes. The combination of PI with narrative we analysed in our scoping data reflects previous studies experimenting with the effect of narrative on presence in VR (Gorini et al., 2011; Riches et al., 2019), which also found that narrative can provide a more compelling experience in VR. Overall, PI with narrative tend to strengthen the overall messages’ persuasiveness through showing events in a designed VR environment.

The effects and mechanism inducing well-being through PI

We coded 188 effects across 80 PI articles, finding that 129 induce SWB and 59 induce PWB (20 for both SWB and PWB). In Fig. 3, we identified major effects: Positive Affect Induction (41), Negative Affect Reduction (24), Stress Reduction (22), Restorativeness Induction (13), and Relaxation Induction (11). Mattila et al. (2020) examined the restorative effects of VR forests and found them equivalent to physical forests. Jo et al. (2021) revealed the physiological benefits of VR forests and their EEG analysis demonstrated an increased Ratio of SMR-Mid Beta to Theta, aiding stress management in college environments. Collectively, VR researchers form positive affect induction techniques by utilising PI to induce Pleasant Affect and reduce Unpleasant Affect, improving SWB.

We identify that PI applications induce SWB primarily by promoting positive affects such as relaxation, restoration, and vitality, while also reducing negative affects like anxiety, stress, and fear. In contrast, PWB is less induced in PI and mostly focuses on building positive relations with others and personal growth through nature experiences. This might be because PI often involves static environments and requires participants’ effortless attention (Kaplan, 1984), leading to well-being enhancement passively (e.g., exposed or absorbed) (Chirico et al., 2018). In contrast, PWB demands directed attention (Kaplan, 1984; Kaplan & Berman, 2010), involving activities such as self-reflection, contemplation, and interaction (Herrera & Bailenson, 2021; Shadiev et al., 2024).

Although fewer articles apply PI for PWB induction, we identified 24 that induce Positive Relations with Others and 10 that induce Personal Growth. Breves and Heber (2020) found that nature VR promotes pro-environmental attitudes and behaviour compared to 2D videos. Fauville et al. (2024) explored underwater VR and found that high levels of presence and eliciting emotion improve participants’ ocean literacy, foster connectedness, and reduce their psychological distance to marine issues.

Lastly, we found fewer but notable PI publications focusing on Self-acceptance (3), Autonomy (4), Purpose in Life (5), and Environmental Mastery (7). Theodorou et al. (2023) had participants view forest, lacustrine, and arctic VR and found induced vitality (compared to urban photos). Meijers et al. (2023) increased participants’ donations to ENGOs by having them experience natural disasters in VR. Lee et al. (2023) had participants virtually shoot and kill the virus inside a human body, promoting the perceived efficacy of vaccination. Overall, despite PWB being less emphasised in PI, recent studies demonstrate potential.

Scholars’ theoretical foundation of applying PI

Our results showed that scholars adopted the lens of positive psychology theories when employing PI in their studies. Attention Restoration Theory suggests that contact with nature alleviates directed attention fatigue and restores attention through effortless engagement (Kaplan, 1995; Ratcliffe et al., 2013). Stress Reduction Theory posits that exposure to non-threatening natural environments leads to faster stress recovery. Awe theory explains individuals’ emotions when encountering vastness, prompting a need for accommodation (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). Since research found that awe induces prosocial behaviour (Piff et al., 2015; Li et al., 2024), scholars strive to reproduce awe-eliciting stimuli using PI and examine participants’ willingness to help, positive and negative affects, and nature-relatedness after experiencing awe (Chirico et al., 2018; Fauville et al., 2024).

Based on our scoping review results of PI studies, although seldom discussed, scholars explore the influences of positive affect-inducing stimuli through Broaden-and-Build Theory to determine whether participants expand perspectives and engage in prosocial behaviours (Fredrickson, 1998; Lin et al., 2024). This theory posits that experiencing self-transcendent and extremely positive emotions broadens one’s thought-action repertoire, enabling innovative and diverse explorations, and ultimately increasing fulfilment and well-being (Fredrickson, 2001). Collectively, our scoping data suggest that PI can be designed to elicit well-being through increasing users’ innovation and self-transcendence.

PSI: stimulus techniques, mechanisms, and theories

PSI stimuli categorisation by illusion elicitation techniques

We categorise PSI stimuli by illusion elicitation techniques into three groups based on emerging themes when conducting the scoping review: (1) Bystander Observation, (2) Interaction and Activity, and (3) Time Travel. All categories employ narratives to guide participants’ attention to an event. Bystander Observation has participants enter an immersive environment and passively view and observe the narrative, while Interaction and Activity makes participants engage with the narrative and often influence the story through editorial decisions. Time Travel is a technique to observe people’s behaviours when given a second chance (Pizarro et al., 2015). These categories are not independent, rather, they often overlap for stronger effects.

The effects and mechanism inducing well-being through PSI

Figure 4 illustrates PSI enhances PWB by promoting empathy, concern, prosocial and pro-environmental behaviours, and reducing bias. These bring participants closer to the topics and foster positive relationships with others, a key dimension of PWB. Additionally, since PSI is flexible to design and depends largely on scholars’ interests, we find a more even distribution of articles addressing other well-being dimensions.

We analysed 223 effects across 113 PSI articles, with 49 inducing SWB and 174 inducing PWB (19 for both SWB and PWB). We categorised PSI techniques into Interaction and Activity (90), Bystander Observation (34), and Time Travel (8). Figure 4 illustrates predominant PSI mechanisms, which mostly include fostering intergroup, interpersonal, and environmental relationships through Bias Reduction (25), Empathy Concern Induction (46), and Prosocial Behaviour Induction (30). Spangenberger et al. (2022) had participants experience the life and death of trees, promoting nature-relatedness. Oh et al. (2016) experimented with enhanced-smile avatars, which led to more positive language conversations. Research uses PSI to improve relationships with others.

Other dimensions of PWB are enhanced via PSI in VR. For instance, Starr et al. (2019) reduced females’ stereotype threats and enhanced their Autonomy by having them visit their future pSTEM office in VR. Lin et al. (2024) increased participants’ self-improvement intentions (Personal Growth) by immersing them in supernatural awe events. Barberia et al. (2018) had participants witness virtual companions and their own deaths, which enhanced their Purpose in Life and interest in global rather than materialistic issues.

SWB receives less but notable attention in PSI research (Pleasant Affect: 20; Unpleasant Affect: 24; Domain Satisfaction: 5). For example, Li et al. (2021) had participants engaged in restorative activities like watering plants and fishing, leading to emotional improvement. Neumann et al. (2023) applied pain stimuli to participants and found that avatars’ verbal support serves as a stress buffer. Shu et al. (2018) enhanced participants’ sense of safety (Domain Satisfaction) by guiding them through earthquake preparation in VR.

We conclude that PSI enables flexible, effective persuasion, specifically in inducing PWB through simulation and showing the consequences of actions.

Scholars’ theoretical foundation of applying PSI

Our results indicate that scholars predominantly leverage PSI to simulate the consequences of an action or event to affect users’ attitudes and behaviour. Hence, scholars applied social psychology theories that explore human perception, cognition, and judgement (e.g., Construal Level Theory and Social Cognitive Theory).

Liberman and Trope’s Construal Level Theory (CLT; 1998) explains the mechanism of PSI’s influence on participants. CLT suggests that the greater psychological distance someone feels toward a topic, the more abstract the topic becomes. By contextualising a distant concept in VR, such as calories (Ahn et al., 2018) and soul-leaving bodies (Bourdin et al., 2017), PSI in VR reduces psychological distance and leads to more concrete ideas and behavioural changes. Virtual interaction, immersive observation, and time travel are PSI techniques that reduce the psychological distance of abstract concepts.

Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT; 1989) is also often employed in PSI studies. SCT explains that behaviour is influenced by the changes to the environment, the consequences of behaviour, and the modelling of others, which reflects how scholars use storytelling and interactive environments to affect behaviour and attitudes (Richards et al., 2023). Scholars use observational learning and vicarious reinforcement in PSI to explore whether participants’ story-identification influences behaviour, despite knowing the simulation is virtual (Bandura & Walters, 1963; Fox & Bailenson, 2009; Slater, 2009). Furthermore, self-efficacy is often studied when experimenting with whether challenging VR activities (e.g., negotiation scenarios and job interviews) enhance one’s self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Ding et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2020; Qu et al., 2015). Overall, SCT guides scholars in developing stimuli that affect perception, cognition, and judgment.

Besides CLT and SCT, scholars applied social psychology theories for different purposes, including the Contact Hypothesis, Exemplification Theory, Solomon’s Paradox, Future Self Model, and Trolley Problem. Tassinari et al. (2024) had participants embody racial ingroup versus outgroup avatars and play a sandbag game, recreating intergroup contact to test the Contact Hypothesis in VR. Reflecting on Solomon’s Paradox, Slater et al. (2019) transformed participants into Freud to advise their own problems, resulting in counsel quality improvement. Overall, PSI is highly flexible for scholars to examine theories virtually.

VBO: stimulus techniques, mechanisms, and theories

VBO stimuli categorisation by illusion elicitation techniques

We categorise VBO elicitation techniques into two groups: (1) Embodying Self and (2) Embodying Others. In Embodying Self, participants are aware they are experiencing the stimuli as themselves. This technique involves participants designing avatars or customisations to foster bonds. In contrast, in Embodying Others, participants are aware that their embodied avatar represents someone else’s identity. This is often achieved through changes in ethnicity, age, social identity, or even species.

Scholars employ Embodying Self primarily to observe reactions when avatar body parts are altered or reactions in specific scenarios. For example, Lin and Wu (2021) had elderly people embody young avatars and observed that these elders demonstrated greater perceived exertion toward the exercise compared to those who embodied elder avatars. Macey et al. (2023) manipulated avatar heights and discovered that being virtually tall reduces public speaking anxiety. VBO allows scholars to predict how humans react or change in certain scenarios.

In contrast, scholars employ Embodying Others to observe how the merger of participants and embodied identity influences participants’ relationships with that identity. Major topics include racial, stereotypical, and environmental concerns. For example, Bedder et al. (2019) found that having light-skinned participants embody dark-skinned avatars decreases their outgroup implicit bias. Targeting non-human entities, Ahn et al. (2016) had participants embody cows and corals, which enhanced nature-relatedness and elicited environmental risk awareness by reducing the temporal distance toward the issues. Embodying Others focuses on the relationship between participants and embodied identity.

The effects and mechanism inducing well-being through VBO

We calculated 169 counts of effects in 84 VBO articles, where 29 induce SWB and 140 PWB (8 for both SWB and PWB). We coded 27 articles of Embodying Self, 31 articles of Embodying Others, and 26 employed both. In Embodying Self, VBO enhances PWB by increasing self-efficacy and self-concept and reducing the self-stereotype threat. VBO also improves SWB by alleviating negative affects and promoting positive affects (Fig. 5). Conversely, in Embodying Others, VBO is primarily used to enhance PWB by fostering positive relationships with specific identities and being in others’ shoes to develop a comprehensive awareness, empathy, and appreciation.

VBO’s mechanism chart (Fig. 5) shows similar patterns to PSI’s, having major contributions to relationship maintenance effects: Empathy Concern Induction (32), Bias Reduction (30), and Prosocial Behaviour Induction (23). Herrera et al. (2018) revealed that while both traditional perspective-taking and VR experiences elicited empathy toward the homeless, VR led to more positive, lasting attitudes and greater prosocial behaviour. Another article investigated how gender transfer in VR affects bias, finding that VBO experience in harassment scenarios modified implicit biases (Wu & Chen, 2022). Collectively, VBO mitigates negative relationships and fulfils PWB.

VBO is used to enhance other PWBs: Personal Growth (13), Self-Acceptance (12), and Environmental Mastery (10), attributed to the Proteus Effect (Yee & Bailenson, 2007). Rosenberg et al. (2013) empowered participants with superhero abilities and observed quicker reactions in prosocial behaviours. Banakou et al. (2018) improved cognitive task performances and reduced age bias by having participants embody Einstein, particularly benefiting those with low self-esteem. Overall, VBO studies enhance PWB through alterations of self-concept.

Although fewer scholars use VBO to promote SWB, our scoping data revealed some addressing Unpleasant Affect (18): Stress Reduction (7), Anxiety Reduction (6), and Pain Reduction (2). Matsangidou et al. (2019) had participants perform an isometric bicep curl task in VR and found that they experienced less pain and greater endurance. Romano et al. (2016) enlarged participants’ body perception in VR and discovered reduced physiological pain responses. While relatively less studied, scholars continually promote SWB with VBO.

Scholars’ theoretical foundation of applying VBO

VBO-related theories focus on the benefits of having participants embody avatars as themselves or others (humans and animals) to experience events. Well-established theories such as the Proteus Effect (Yee & Bailenson, 2007) describe how avatars’ appearance and characteristics influence users’ behaviours and attitudes. Embodied Experience (Ahn et al., 2013) emphasises “being in others’ shoes,” advancing traditional perspective-taking exercises to foster understanding. Slater et al. (2010) expanded on Botvinick and Cohen’s Rubber Hand Illusion (1998) by introducing the Body Transfer Illusion, demonstrating that visuomotor correlation triggers a bottom-up perceptual mechanism that makes users feel as if they are bonded with avatars. Collectively, scholars applied these theories and explored how VBO enhances one’s attitudes, behaviours, and well-being.

Overall stimuli categorisation by topics

Although outside the original scope of our guiding research questions, we observed that most VR stimuli in our scoping data aim to address three types of topics: (1) Environmental Concerns, (2) Societal Concerns, and (3) Self Concerns. This categorisation is not limited to a specific VR illusion; rather, these different types of topics can be observed across PI, PSI, and VBO stimuli.

Scholars present environmental concerns by having participants witness natural disasters (PI), embody animals for first-hand experiences (VBO), or see how human behaviours deteriorate environments (PSI). Mado et al. (2021) transported participants to the end of the century to witness the state of reefs if carbon pollution continues. Bailey et al. (2014) had participants virtually shower while watching coal burn, then measured the temperature and amount of water used during hand washing. Combining VBO and PSI, Ahn et al. (2016) had participants embody coral and experience branch breaks due to fishing net impacts. Contextualising environmental issues, scholars enhance participants’ pro-environmental behaviour, nature-relatedness, and environmental responsibility.

Societal concerns include ethnic intergroup conflict, crime prevention, disadvantaged minorities, and emergency reactions. Patané et al. (2020) found that participants decreased their outgroup bias after a collaborative task with virtual African Americans. Seinfeld et al. (2018) recruited male domestic violence offenders and had them virtually experience violence from a female victim’s perspective, enhancing their recognition of females’ fearful expressions. Rovira et al. (2021) and Bouchard et al. (2013) studied participants’ emergency reactions by measuring their behaviour when witnessing others being abused or cramped. Using VR to simulate virtual events that happen on or around them allows scholars to observe perceptual and behavioural changes regarding societal issues.

Lastly, scholars explore Self Concerns by placing participants in various scenarios leveraging each VR illusion. Friedman et al. (2014) put participants in the trolley problem and let them travel back in time to remake choices, which reduces their own life’s regretfulness. Guterstam et al. (2015) made participants virtually invisible, which reduced their social anxiety. Collectively, scholars employ different illusion elicitation techniques to contextualise abstract concepts and help participants address Self Concerns.

Despite categorising the VR stimuli by topic was beyond our research questions, we report this observation to provide information on how VR scholars address Environmental, Societal, and Self Concerns by taking full advantage of PI, PSI, and VBO.

Discussion

We conducted a scoping review based on the past 30 years of empirical evidence in VR to organise the existing evidence, and we propose a theoretical framework for VR InducE Well-being (VIEW, Fig. 6) to theorise the mechanisms of how VR induces well-being. In VIEW, through VR exposure, each element primarily causes distinct illusions: PI (environment), PSI (interaction), and VBO (virtual embodiment). Our scoping data then bridges the illusions to 32 identified effects on well-being and maps how they contribute to 10 subdimensions in SWB and PWB. The mechanisms of VR inducing well-being are synthesised below.

First, our scoping data on PI explores how researchers expose participants to nature, manmade, and surreal VR environments, successfully eliciting feelings of relaxation, restorativeness, and vitality while reducing stress and anxiety (Anderson et al., 2017). Overall, our data showcase PI’s strength in inducing SWB and its potential in fostering PWB by outlining linear mechanisms. Second, our scoping data reveals how scholars utilise PSI to induce PWB, with a secondary effect on SWB (Ahn, 2014; Kang et al., 2020). While the evidence for SWB induction is less prominent, the findings demonstrate PSI’s predominant role in enhancing PWB. Third, our scoping data implied that scholars applied VBO to predominantly induce PWB. Overall, VBO demonstrates its strength in promoting PWB through inductions in empathy concern, personal growth, and some support for SWB enhancement through the reduction of negative affects.

Lastly, we found that Life Satisfaction, a key dimension of SWB, is rarely measured in Media Psychology VR research. This may be due to the one-directional (researchers → participants) norm with pre-designed messages and simulations in VR experiments, where most focus on short-term, specific effects rather than the broader, long-term perspective of Life Satisfaction. However, it is important to note that numerous VR studies in medical and nursing fields have examined Life Satisfaction and Quality of Life. In these areas, Life Satisfaction often centres on health, mobility, physical functioning (e.g., Kaplan et al., 1997), and job satisfaction among specific groups like doctors, nurses, and patients, rather than general users (Linzer et al., 2016). Overall, Life Satisfaction remains underexplored in Media Psychology VR research, yet deserves studies to reveal the long-term, macro effects of VR on well-being.

In addition, the Purpose in Life dimension of Psychological Well-Being (PWB) is also less explored. Similar to Life Satisfaction, this may be because most experiments focus on short-term effects using pre-designed messages and simulations in VR experiments. In contrast, Purpose in Life refers to having determination and meaning in life (Ryff & Keyes, 1995), which may require much greater personalization in VR stimuli—not just avatar customization, but full autonomy in how users decide to engage with VR technology to fulfil their own goals and make life more meaningful. For example, forming habits such as using VR to exercise (Hooker & Masters, 2016), socialize with others in VR social networks (Rook & Charles, 2017), or even participate in political movements (Boulianne, 2015). To observe how VR can foster one’s Purpose in Life, we anticipate that long-term user observational research would be more appropriate. However, such research is often more difficult and resource-intensive compared to typical VR lab experiments. As the number of VR users continues to grow (Statista, 2024), we believe this area warrants further investigation in future research.

Since VIEW is a technology-centred theory, we hypothesise that individual differences—such as state, trait, and media skill—will moderate the linear mechanisms within VIEW. Trait factors like empathy, dispositional awe, religious views, and spirituality may influence how PI, PSI, and VBO induce well-being. For example, individuals with higher trait empathy or greater dispositional awe may experience stronger well-being responses (Jiao & Luo, 2022; Shiota et al., 2014). Biological sex may also serve as a moderator, with male participants reporting lower levels of VBO illusions and their subsequent effects compared to females (Lin & Wu, 2021; Lin et al., 2021). Furthermore, spirituality and religious beliefs may shape users’ experiences in VR, particularly related to PWB (Maxwell, 2002; Raj et al., 2023). We therefore encourage future research to empirically explore how these individual differences influence the effects of VIEW.

What does VIEW Offer: VR can effectively induce well-being

VIEW specifically focuses on VR and contributes to the literature by illustrating the key mechanisms for effective stimulus design and predictable outcomes. Through scoping 18,008 publications across 30 years, this model offers predictable insights into mechanisms to use VR to induce well-being.

We believe that VIEW is the first theoretical framework that maps the nuances between VR studies and well-being. Before VIEW, the academic understanding of VR effects was less organised. While specific VR effects were recognised, without contextualising and organising the 32 effects identified by scholars, we have limited evidence regarding which dimensions of well-being have garnered attention, and more importantly, which require investment. Utilising the scoping review methodology, we illustrate the mechanisms of applied theories, effects, well-being outcomes, and research ratio in a four-step flowchart.

Additionally, by mapping how theories explain induced effects, VIEW provides empirical guidelines for VR scholars and designers, especially when dealing with PI, PSI, and VBO simultaneously. By linking the evidence of affective effects to SWB and eudaimonic effects to PWB, VIEW serves as a theoretical guideline for the design and prediction of VR-induced well-being.

Lastly, although VIEW categorises VR illusion elicitation techniques for each illusion, we emphasise that it remains flexible to accommodate new mechanisms as they are discovered. For instance, before Head-mounted Displays became accessible, most VBO techniques were not feasible due to technical limitations. In contrast, experimental designs like time travel and the “invisible man” emerged much later, despite the technology has long been accessible. As Extended Reality evolves, we welcome the inclusion and discussion of new methods to fulfil VIEW. We also suggest that this scoping review and the VIEW model are only the beginning for us to understand how VR can induce well-being, not the magic-bullet type of VR will induce well-being. We humbly propose the model for robust theoretical development, and acknowledge that individual differences are key to influencing such mechanisms. From this scoping review, researchers can further explicate how individual differences would moderate or influence such mechanisms.

Future research directions

We propose several hypotheses to test VIEW’s robustness. First, PI is expected to enhance SWB through affective-route mechanisms. Second, PSI and VBO are likely to improve PWB via cognitive-route mechanisms. Third, VR content that incorporates all three illusions—PI, PSI, and VBO—will produce the most significant effects on well-being and persuasion, compared to scenarios with fewer illusions. Lastly, individual differences will moderate the relationships between VR illusions and well-being outcomes.

During our scoping process, three empirical gaps in VR scholarship became evident: (1) autonomy in VR, (2) multi-user experiences, and (3) perceptual factor enhancement. First, likely due to the limitations of experimental methods, we found that very few studies provide participants with sufficient autonomy to explore VR. Most research offers pre-programmed, one-directional experiences in one software, limiting participants’ freedom to engage with the features and illusions of VR. This lack of autonomy leads researchers to focus on how VR affects users, but overlooks how users engage with VR’s illusions and discover personalised ways to benefit from it. Drawing on self-determination theory and social cognitive theory, offering users the freedom to explore simulated events, time, and interactions can enhance need satisfaction and cognitive appraisal, potentially improving well-being outcomes. Without addressing this gap, the relationship between well-being and the long-term effects of VR remains underexplored.

Second, we found that VR research is largely focused on solo experiences. Although multi-user experience research is gaining attention (e.g., DeVeaux et al., 2024; Han & Bailenson, 2024), there has been limited exploration of how these illusions affect interpersonal and group communication in real-time settings, such as social VR. Additionally, important technical aspects, like the presence of nonverbal cues and the use of symmetrical or asymmetrical interaction methods, remain underexplored and require further investigation.

Third, as perceptual factors like content realism, immersion, and mixed-reality technology rapidly evolve, it is crucial to examine the extent to which VIEW can predict outcomes and when it might break down. For example, the high-quality virtual environments offered by devices like the Apple Vision Pro could lead to more effective VIEW processes compared to lower-quality 360-degree videos on entry-level models. In terms of mixed reality, future innovations such as real-time texture changes could transform a user’s physical body into a virtual simulation through mixed-reality glasses, enabling them to remain in the real world while viewing their body with virtual elements. In contrast, similar to other media, it is important to explore when VR might become overwhelming and start to diminish well-being, or if the various well-being dimensions might begin to conflict (e.g., addiction). As technology advances, its impact on society’s well-being must be continuously assessed.

In addition, although beyond this study’s scope, we are also aware that the complexity of the environment (Bratman et al., 2015; Chirico et al., 2017; Goller et al., 2019) and the number of senses (Ahn et al., 2019; Fauville et al., 2024; Ferrise et al., 2024) involved can also affect VR’s effect on people’s well-being. In our scoping data, we include VR stimuli ranging from low-graphic (Oh et al., 2016) to high-resolution experiences (Fu et al., 2022). We also include those that evoke from only visual and audio senses to touch and feel (Fauville et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2021). However, the complexity and number of senses were not coded in our scoping data and thus were not analysed in our study. For future direction, we believe these are important variables for VR designers and developers to consider regarding their influence on well-being induction.

As VIEW is based on a scoping review of over 30 years of evidence, new publications, VR applications, and illusions will continue to expand its scope. We anticipate that these empirical gaps will be explored in future research, further strengthening our understanding and examination of VIEW.

Limitations

Although our dataset exceeds 18,000 articles, we acknowledge that our scoping data is comprehensive but not exhaustive. Firstly, our focused framework on Media Psychology left VR applications in medicine undiscussed. Secondly, as we limited our inclusion criteria to English peer-reviewed original articles, publications written in other languages or published in other forms are not shown in our analysis. Thirdly, the scoping review was conducted during 2024, which is a critical time when technology giants develop AI models and integrate them into VR headsets. We expect related publications to emerge in 2025 and will influence VR’s impact on human well-being. Hence, we encourage future reviews to address the aforementioned limitations with broader inclusion criteria and observe how AI would affect the relationship between VR and human well-being. Lastly, we would like to stress that the VIEW model is not a magic-bullet-type of approach, but rather, we acknowledge the audience’s differences and reactions in this process. We simply and humbly propose this design approach through this scoping review of these abundant pieces of evidence to illustrate the stimulus design, illusions, mechanisms, and well-being outcomes.

Conclusion

Drawing on 30 years of evidence, VIEW organises how scholars leverage VR’s unique illusions through stimulus design to induce SWB and PWB via various mechanisms. VIEW serves as a guiding model for VR developers to strategically achieve specific well-being outcomes through specific mechanisms. Additionally, our data highlights the imbalance in academic attention across 10 well-being dimensions, with Pleasant Affect and Positive Relations with Others receiving the most attention, while Life Satisfaction and Purpose in Life remain underexplored. Although beyond our scoping objective, we note that designers must consider individual differences when using VIEW to predict well-being. Finally, we identify three key empirical gaps in current VR scholarship: autonomy in VR, multi-user experiences, and perceptual factor enhancement. We encourage future research to explore these areas to deepen our understanding of VR’s impact on human well-being.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available in this article’s supplementary information file.

Notes

Stimulus dynamics refers to the kind of dynamic that the stimulus aims to influence in the participant. For example, if a stimulus has participants witness a natural disaster, we code the publication’s stimulus dynamics as “environment,” since the stimulus is intended to affect participants’ thoughts about the environment; If the stimulus has one racial group embody another race’s body to examine whether racial bias decreases, we code “intergroup.” Same as other codes, any uncertainties or questions were discussed in detail until a consensus was reached.

References

Ahn SJ (2014) Incorporating immersive virtual environments in health promotion Campaigns: A Construal level Theory approach. Health Commun 30(6):545–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.869650

Ahn SJ, Bostick J, Ogle E et al. (2016) Experiencing nature: Embodying animals in immersive virtual environments increases inclusion of nature in self and involvement with nature. J Comput Mediat Commun 21(6):399–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12173

Ahn SJ, Hahm JM, Johnsen K (2018) Feeling the weight of calories: using haptic feedback as virtual exemplars to promote risk perception among young females on unhealthy snack choices. Media Psychol 22(4):626–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1492939

Ahn SJ, Le AMT, Bailenson J (2013) The effect of embodied experiences on Self-Other merging, attitude, and helping behavior. Media Psychol 16(1):7–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2012.755877

Anderson AP, Mayer MD, Fellows AM et al. (2017) Relaxation with immersive natural scenes presented using virtual reality. Aerosp Med Hum Perform 88(6):520–526. https://doi.org/10.3357/amhp.4747.2017

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Aron A, Aron E, Smollan D (1992) Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J Pers Soc Psychol 63(4):596. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

Bachen C, Hernández-Ramos P, Raphael C et al. (2016) How do presence, flow, and character identification affect players’ empathy and interest in learning from a serious computer game? Comput Hum Behav 64:77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.043

Bailey JO, Bailenson JN, Flora J et al. (2014) The impact of vivid messages on reducing energy consumption related to hot water use. Environ Behav 47(5):570–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916514551604

Banakou D, Hanumanthu P, Slater M (2016) Virtual embodiment of white people in a black virtual body leads to a sustained reduction in their implicit racial bias. Front Hum Neurosci 10:601. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00601

Banakou D, Kishore S, Slater M (2018) Virtually being Einstein results in an improvement in cognitive task performance and a decrease in age bias. Front Psychol 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00917

Bandura A (1989) Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 44(9):1175. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Bandura A (1997) Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York

Bandura A, Walters RH (1963) Social learning and personality development. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

Barberia I, Oliva R, Bourdin P et al. (2018) Virtual mortality and near-death experience after a prolonged exposure in a shared virtual reality may lead to positive life-attitude changes. PLoS One 13(11):e0203358. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203358

Barreda-Ángeles M, Aleix-Guillaume S, Pereda-Baños A (2020) An “empathy machine” or a “just-for-the-fun-of-it” machine? Effects of immersion in nonfiction 360-Video stories on empathy and enjoyment. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 23(10):683–688. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0665

Bedder RL, Bush D, Banakou D et al. (2019) A mechanistic account of bodily resonance and implicit bias. Cognition 184:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.11.010

Boulianne S (2015) Social media use and participation: A meta-analysis of current research. Inf Commun Soc 18(5):524–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1008542

Botvinick M, Cohen J (1998) Rubber hands ’feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature 391(6669):756. https://doi.org/10.1038/35784

Bouchard S, Bernier F, Boivin É et al. (2013) Empathy toward virtual humans depicting a known or unknown person expressing pain. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16(1):61–71. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.1571

Bourdin P, Barberia I, Oliva R et al. (2017) A virtual out-of-body experience reduces fear of death. PloS One 12(1):e0169343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169343

Breines J, Chen S (2012) Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Pers Soc Psychol B 38(9):1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212445599

Bradley M, Lang P (1994) Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J Behav Ther Exp Psy 25(1):49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9

Bratman G, Daily G, Levy B et al. (2015) The benefits of nature experience: improved affect and cognition. Landsc Urban Plan 138:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.005

Breves P, Heber V (2020) Into the Wild: The effects of 360° immersive nature videos on feelings of commitment to the environment. Environ Commun 14(3):332–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2019.1665566

Caponnetto P, Triscari S, Maglia M et al. (2021) The simulation game—Virtual reality therapy for the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(24):13209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413209

Carstensen L, Lang F (1996) Future time perspective scale. Available via Life-span Development Lab. https://lifespan.stanford.edu/ftp. Accessed 7 June 2025

Cebolla A, Herrero R, Ventura S et al. (2019) Putting oneself in the body of others: a pilot study on the efficacy of an embodied virtual reality system to generate self-compassion. Front Psychol 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01521

Chandran S, Menon G (2004) When a day means more than a year: Effects of temporal framing on judgments of health risk. J Consum Res 31(2):375–389. https://doi.org/10.1086/422116

Chirico A, Cipresso P, Yaden D et al. (2017) Effectiveness of immersive videos in inducing awe: an experimental study. Sci Rep. 7(1):1218. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01242-0

Chirico A, Ferrise F, Cordella L et al. (2018) Designing awe in Virtual Reality: an Experimental study. Front Psychol 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02351

Cooper P, Taylor M, Cooper Z et al. (1987) The Development and Validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord 6(4):485–494. 10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485::AID-EAT2260060405>3.0.CO;2-O

Creswell J (2018) Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 6th edn, Pearson

Cropley D, Cropley A (2008) Elements of a universal aesthetic of creativity. Psychol Aesthet Creativity Arts 2(3):155–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3896.2.3.155

Davis M (1983) Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 44(1):113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Davis D, Hook J, Worthington JrE et al. (2011) Relational humility: Conceptualizing and measuring humility as a personality judgment. J Pers Assess 93(3):225–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.558871

Deci E, Ryan R (2008) Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. J Happiness Stud 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1

DeVeaux C, Markowitz DM, Han E et al. (2024) Presence and Pronouns: An Exploratory Investigation into the Language of Social VR. J Lang Soc Psychol 43(4):405–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x241248646

Di Pompeo I, D’Aurizio G, Burattini C et al. (2023) Positive mood induction to promote well-being and health: A systematic review from real settings to virtual reality. J Environ Psychol 91:102095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102095

Diener E (1984) Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull 95(3):542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ et al. (1985) The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 49(1):71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE et al. (1999) Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol Bull 125(2):276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Ding D, Brinkman W, Neerincx MA (2020) Simulated thoughts in virtual reality for negotiation training enhance self-efficacy and knowledge. Int J Hum Comput Stud 139:102400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102400

Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C (2008) A Conceptual Model of Medical Student Well-Being: Promoting Resilience and Preventing Burnout. Acad Psychiatry 32(1):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.32.1.44

Eccles J, Wigfield A (1995) In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Pers Soc Psychol B 21(3):215–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295213003

Ellis A (2005) The myth of self-esteem: How rational emotive behavior therapy can change your life forever. Prometheus Books, Amherst NY

Farashi S, Bashirian S, Jenabi E et al. (2024) Effectiveness of virtual reality and computerized training programs for enhancing emotion recognition in people with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dev Disabil70(1):110–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2022.2063656

Faria AL, Latorre J, Silva Cameirão M et al. (2023) Ecologically valid virtual reality-based technologies for assessment and rehabilitation of acquired brain injury: A systematic review. Front Psychol 14:1233346. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1233346

Fauville G, Voşki A, Mado M et al. (2024) Underwater virtual reality for marine education and ocean literacy: technological and psychological potentials. Environ Educ Res 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2024.2326446

Ferrise F, Bordegoni M, Gallace A et al. (2024) Multisensory experiences in extended reality. IEEE Comput Graph 44(4):11–13. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCG.2024.3428110

Fox J, Bailenson JN (2009) Virtual Self-Modeling: The effects of vicarious reinforcement and identification. Media Psychol 12(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260802669474

Fredrickson BL (1998) What good are positive emotions? Rev Gen Psychol 2(3):300–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300

Fredrickson BL (2001) The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol 56(3):218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.218

Friedman D, Pizarro R, Or-Berkers K et al. (2014) A method for generating an illusion of backwards time travel using immersive virtual reality: an exploratory study. Front Psychol 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00943

Frost S, Kannis-Dymand L, Scaffer V et al. (2022) Virtual immersion in nature and psychological well-being: A systematic literature review. J Environ Psychol 80:101765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101765

Fu E, Zhou J, Ren Y et al. (2022) Exploring the influence of residential courtyard space landscape elements on people’s emotional health in an immersive virtual environment. Front Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1017993

Goller J, Mitrovic A, Leder H (2019) Effects of liking on visual attention in faces and paintings. Acta Psychol 197:115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2019.05.008

Gorini A, Capideville C, De Leo G et al. (2011) The role of immersion and narrative in mediated presence: the virtual hospital experience. Cyberpsych Beh Soc N. 14(3):99–105. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0100

Greenwald A, McGhee D, Schwartz J (1998) Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol 74(6):1464. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

Greyson B, Ring K (2004) The Life Changes Inventory—Revised. J -Death Stud 23(1):41–54

Guilford J (1967) Creativity: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. J Creative Behav 1(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.1967.tb00002.x

Guterstam A, Abdulkarim Z, Ehrsson HH (2015) Illusory ownership of an invisible body reduces autonomic and subjective social anxiety responses. Sci Rep 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09831

Han E, DeVeaux C, Hancock JT et al. (2024) The influence of spatial dimensions of virtual environments on attitudes and nonverbal behaviors during social interactions. J Environ Psychol 95:102269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102269

Hartmann T, Wirth W, Schramm H et al. (2015) The Spatial Presence Experience Scale (SPES). J Media Psychol 28(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000137

Hayes AF, Krippendorff K (2007) Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun Methods Meas 1(1):77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450709336664

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG (2012) Acceptance and commitment therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, 2nd edn. Guilford Press, New York

Herrera F, Bailenson J (2021) Virtual reality perspective-taking at scale: Effect of avatar representation, choice, and head movement on prosocial behaviors. N. Media Soc 23(8):2189–2209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444821993121

Herrera F, Bailenson J, Weisz E et al. (2018) Building long-term empathy: A large-scale comparison of traditional and virtual reality perspective-taking. PLoS One 13(10):e0204494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204494

Hershfield H, Goldstein D, Sharpe W et al. (2011) Increasing saving behavior through age-progressed renderings of the future self. J Mark Res 48(SPL):23–37

Hooker S, Masters K (2016) Purpose in life is associated with physical activity measured by accelerometer. J Health Psychol 21(6):962–971. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314542822

Horky F, Krell F, Fidrmuc J (2023) Setting the stage: Fairness behavior in virtual reality dictator games. J Behav Exp Econ 107:102114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2023.102114

Hooker SA, Masters KS (2016) Purpose in life is associated with physical activity measured by accelerometer. J Health Psychol 21(6):962–971

Hunter E, Röös E (2016) Fear of climate change consequences and predictors of intentions to alter meat consumption. Food Policy 62:151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.06.004

Jaskiewicz W, Tulenko K (2012) Increasing community health worker productivity and effectiveness: a review of the influence of the work environment. Hum Resour Health 10:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-10-38

Jiao L, Luo L (2022) Dispositional awe positively predicts prosocial tendencies: the multiple mediation effects of connectedness and empathy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(24):16605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416605

Jo S, Park J, Yeon P (2021) The effect of forest video using virtual reality on the stress reduction of university students focused on C University in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(23):12805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312805

Kahn AS, Cargile AC (2021) Immersive and interactive Awe: evoking awe via presence in virtual reality and online videos to prompt prosocial behavior. Hum Commun Res 47(4):387–417. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab007

Kang N, Ding D, Van Riemsdijk MB et al. (2020) Self-identification with a Virtual Experience and Its Moderating Effect on Self-efficacy and Presence. Int J Hum Comput Interact 37(2):181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1812909

Kaplan R (1984) Impact of urban nature: A theoretical analysis. Urban Ecol 8(3):189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4009(84)90034-2

Kaplan RM, Sieber WJ, Ganiats TG (1997) The quality of well-being scale: Comparison of the interviewer-administered version with a self-administered questionnaire. Psychol Health 12(6):783–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449708406739

Kaplan S (1995) The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol 15(3):169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Kaplan S, Berman M (2010) Directed attention as a common resource for executive functioning and self-regulation. Perspect Psychol Sci 5(1):43–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691609356784

Keltner D, Haidt J (2003) Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn Emot 17(2):297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297