Abstract

Time theft has been a major issue in organizations that can affect performance and workplace dynamics. However, most previous studies have attributed the creation of time theft to external stimuli, overlooking the individual’s subjective initiative. This study investigates the interplay between Machiavellianism, moral disengagement, laissez-faire leadership, time theft, and gender differences within these interactions in terms of individual subjective initiatives. Data were collected from 350 employees in Chinese enterprises through a two-stage cross-sectional design and analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling. The findings demonstrate that Machiavellianism is positively associated with time theft (falsifying working hours and manipulating the speed of work), with moral disengagement mediating this relationship. Laissez-faire leadership intensifies the relationship between Machiavellianism and moral disengagement, thereby exacerbating time theft. Gender differences emerged, males demonstrate a stronger association between Machiavellianism and falsifying work hours. By integrating self-presentation and moral disengagement theories into organizational ethics, this research underscores the proactive influence of individual traits on unethical behavior. It further highlights the pivotal role of leadership styles in ethical decision-making, advocating for balanced leadership strategies to mitigate workplace deviance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Time is a scarce and invaluable resource in organizational contexts, underpinning productivity, efficiency, and a business’s competitive edge. Despite its importance, time theft persists as a prevalent issue in the modern workplace (Harold et al., 2022; Sinclair, 2024). This behavior not only takes away critical time investments from organizations but also disrupts team climate and erodes trust (Hu et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2024). The ramifications of time theft are far-reaching, impacting organizational performance through increased costs, reduced morale, and the potential for unethical conduct to become normalized (Brock et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2023; Sinclair, 2024). This challenge becomes even more complex in AI-mediated workplaces, where algorithmic monitoring may reshape interpersonal dynamics and introduce new opportunities for deception (Ho and Vuong, 2024; Ho and Ho, 2025). Given these risks, curbing time theft is not merely an ethical imperative but also a strategic priority for organizations.

Previous scholars have mainly attributed the triggers of time theft to the stimulation of external factors (Fatima et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2023; Sinclair, 2024). These studies highlight the role of organizational policies, unfair treatment, and the physical work environment. However, they overlook an important fact that time theft may be a purposeful behavior, reflecting the employee’s subjective initiative (Liao et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2025). The psychological interior of an employee, encompassing their ethical reasoning, core values, and personality orientations (Önalan and Özer, 2021; Zhao and Ma, 2023; Liao et al., 2024), can serve as a potent motivator for time theft, even in the absence of external provocations. Among various internal factors, personality stands out as a stable and influential determinant that shapes how individuals interpret their environment and make behavioral choices (Brock et al., 2013; Önalan and Özer, 2021). In particular, one personality trait that has garnered increasing attention in the context of deviant workplace behavior is Machiavellianism. Rooted in a worldview of manipulation and strategic advantage, Machiavellianism reflects a tendency toward instrumental reasoning and interpersonal manipulation (Jonason and Webster, 2010; Jahangir et al., 2025). This personality orientation may be especially salient in the Chinese cultural context, where the philosophy of face-saving, strategic manipulation, and power tactics has long been embedded in traditional value systems (Leung et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2017). Moreover, empirical research has consistently linked Machiavellian traits to a wide range of unethical behaviors (Castille et al., 2018; Gurlek, 2021; Long et al., 2024). Therefore, in the context of Chinese culture, Machiavellianism may be a key internal predictor of time theft, even in the absence of external triggers.

According to self-presentation theory, individuals with Machiavellian traits are driven by the desire to craft a favorable image of themselves, often prioritizing personal gain over ethical considerations (Baumeister and Hutton, 1987; Geis and Moon, 1981; Hollebeek et al., 2022). This propensity for self-interest may lead such individuals to engage in time theft as a strategic move to enhance their perceived productivity or to secure unjustified rewards, thereby maintaining a positive self-image (Geis and Moon, 1981; Azizoglu and Akdag, 2024; White et al., 2024), such as by deliberately working longer hours to project an image of conscientiousness. Despite the plausibility of this link, current research has done little to explore the connection between Machiavellianism and time theft, and particularly the underlying psychological mechanisms that motivate such actions. Moral disengagement theory further posits that Machiavellian individuals may rationalize time theft by disengaging their behavior from moral self-sanctions (Bandura, 1999; Sijtsema et al., 2019; Sarwar and Song, 2025). By employing cognitive strategies such as moral justification or displacement of responsibility, these individuals can disassociate their actions from personal ethics (Sijtsema et al., 2019; Ogunfowora et al., 2022), thereby reducing any potential feelings of guilt or remorse. This process of moral disengagement may facilitate the perpetration of time theft by allowing Machiavellian individuals to perceive their actions as being outside the realm of unethical behavior (Fida et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025).

Furthermore, despite the growing volume of research on ethical leadership, bibliometric evidence suggests that limited attention has been paid to the interface between leadership styles and dark personality traits in shaping ethical decision-making (Ali et al., 2023). The approach taken by leaders in managing their teams can either foster a culture of accountability and integrity or one that inadvertently encourages unethical conduct (Kelly and Herald, 2020; Piwowar-Sulej and Iqbal, 2023; Hu et al., 2023). This gap provides a basis for examining laissez-faire leadership, which is often overlooked due to its passive nature. Laissez-faire leadership is understood differently across cultures. In the West, non-intervention is often seen as poor leadership. In China, it may be viewed as a culturally appropriate way to maintain harmony and respect hierarchical order (Mantello et al., 2023; Ali et al., 2023). This aligns with the Daoist concept of “Wu Wei,” which encourages non-interference to preserve internal stability and order. This non-interventionist logic becomes especially relevant in contemporary AI-mediated management systems, where human moral oversight is often diminished (Ho and Vuong, 2024; Mantello et al., 2023; Ho and Ho, 2025). In such low-supervision and ambiguous environments (Skogstad et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2023), individuals high in Machiavellianism may find more opportunities for strategic self-presentation, increasing the risk of time theft. Therefore, including laissez-faire leadership in this study helps address a gap in the literature on how non-interventionist leadership, shaped by cultural norms, modulates the relationship between Machiavellianism and time theft in the Chinese context.

Finally, we explore the differences in the influence of time theft behavior among Machiavellian individuals of across genders. The rationale for examining gender differences in the context of Machiavellianism and time theft is multifaceted. Firstly, it is essential for achieving a more equitable and comprehensive understanding of organizational behaviors, where the perspectives and potential disparities between genders are acknowledged and explored (Tricahyadinata et al., 2020). Secondly, investigating these differences can reveal whether there are gender-specific vulnerabilities to time theft, enabling the development of targeted preventative measures. Thirdly, understanding how gender may influence the relationship between Machiavellianism and time theft can inform the creation of more inclusive organizational policies and ethical frameworks (Tang and Sutarso, 2013; Syed and Tariq, 2017; White et al., 2024). In summary, this study seeks to address several pivotal questions:

-

(1)

How does Machiavellianism interact with self-presentation and moral disengagement to facilitate time theft?

-

(2)

What is the moderating influence of laissez-faire leadership on the relationship between Machiavellianism and time theft behaviors?

-

(3)

How do gender differences manifest in the context of these interactions, influencing the prevalence of time theft?

This study explores the role of Machiavellianism, moral disengagement mechanisms, and laissez-faire leadership in time theft behavior, focusing on the impact of individual internal motives. The contribution of this research lies in its integration of self-presentation theory and moral disengagement theory, demonstrating how Machiavellianism drives time theft through moral disengagement. Furthermore, the study highlights the amplifying role of laissez-faire leadership in this process. Finally, it examines gender differences in how Machiavellianism influences time theft, offering new theoretical perspectives that can guide organizations in developing ethical policies and leadership strategies.

Review and hypothesis

Time theft

Time theft is the act of intentionally misrepresenting the amount of time spent on work-related activities for personal gain (Brock et al., 2013). Time theft is characterized by its deceptive nature, as it involves the employee deceiving the employer about the actual time spent on work (Brock et al., 2013; Harold et al., 2022; Sinclair, 2024). It is often conducted in secret to avoid detection and can vary in frequency and magnitude. Time theft, a complex and multifaceted issue in organizational contexts, can be understood and measured through various dimensions. One of the most comprehensive classifications of time theft dimensions was proposed by Harold et al. (2022), who delineated time theft into five distinct yet interconnected categories: unauthorized breaks, excessive socialization, spending time on non-work tasks, falsifying working hours (FWH), and manipulating the speed of work (MSW).

The dimensions of FWH and MSW were chosen for this study due to their direct impact on organizational costs and their relevance to the theoretical framework involving Machiavellianism and moral disengagement. First, the cost impact of FWH and MSW in an organization is immediate and significant. Employees receive additional compensation by misrepresenting their working hours, which not only increases the financial burden on the organization but may also cause dissatisfaction and a lack of trust among other employees, which affects team morale and the overall work atmosphere. Second, Machiavellian personality traits include manipulativeness, deception, and the pursuit of personal gain (White et al., 2024; Jahangir et al., 2025), which are highly correlated with the behaviors of FWH and MSW. FWH pertains to the dishonest reporting of work hours, where employees may claim to have worked more hours than they did. MSW involves employees intentionally working at a slower pace than required to complete their tasks, to extend the duration of their workday or project. Machiavellians may use these dishonest means to advance their status or gain without considering the long-term impact on the organization.

Machiavellianism and time theft

Machiavellianism is derived from the works of the Italian political figure and philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli and refers to a set of personality traits characterized by cunning, tactical deception, and a pragmatic ethical stance (Jonason and Webster, 2010; Jahangir et al., 2025; White et al., 2024). Key characteristics of Machiavellianism include a cynical view of human nature, a tendency to manipulate others for personal benefit, and a detached attitude towards traditional morality (Jahangir et al., 2025). Moreover, these individuals are skilled at impression management, often flattering superiors or concealing their poor performance to maintain a positive image in the workplace (Jahangir et al., 2025).

According to self-presentation theory, individuals actively manage the impressions they convey in social interactions (Baumeister and Hutton, 1987). In China’s collectivist and face-saving conscious culture, Machiavellian individuals are more likely to exploit social networks and relational strategies to maintain a positive outward image (Zhang et al., 2011; Xie and Shi, 2022). For instance, they may falsify work hours, such as by altering time card records or concealing instances of leaving early, to avoid creating a negative impression on their superiors. Similarly, they may manipulate the speed of their work to reduce the amount of work they do or to extend their working hours, thereby creating the illusion of being a dedicated employee. These behaviors align with their self-serving nature and reflect their ability to morally disengage, allowing them to engage in time theft without concern for the organization’s well-being or ethical norms (Jonason and Webster, 2010; Jahangir et al., 2025). Existing research also supports the idea that individuals high in Machiavellianism are more likely to resort to deceitful and manipulative tactics to achieve their personal goals (Brewer and Abell, 2015; Maftei et al., 2022; Sarwar and Song, 2025). Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1a: Machiavellianism is positively associated with FWH.

H1b: Machiavellianism is positively associated with MSW.

The mediating role of moral disengagement. Moral disengagement refers to the cognitive mechanisms that allow individuals to distance themselves from the moral and self-sanctioning consequences of their actions, thus enabling them to engage in behaviors typically considered unethical without experiencing feelings of guilt or shame (Bandura, 1999; Moore, 2015; Ogunfowora et al., 2022). Individuals high in Machiavellianism, marked by manipulativeness, emotional detachment, and a pragmatic moral orientation, tend to prioritize personal goals over ethical considerations (Bereczkei, 2015; Maftei et al., 2022). According to moral disengagement theory, people may use cognitive mechanisms, such as moral justification, minimization of harm, and diffusion of responsibility, to rationalize unethical behavior and avoid self-condemnation (Bandura, 2017; Ogunfowora et al., 2022). These mechanisms align closely with Machiavellian tendencies, as such individuals are skilled at reframing morally questionable actions as necessary, strategic, or inconsequential. As a result, they can maintain a positive self-image while engaging in behaviors that violate normative ethical standards. Some empirical studies have shown that individuals high in Machiavellianism are more likely to exhibit moral disengagement (Maftei et al., 2022; Català and Caparrós, 2023; Kornienko et al., 2024). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2a: Machiavellianism is positively associated with moral disengagement.

Moreover, moral disengagement may facilitate the occurrence of time theft behaviors. According to moral disengagement theory, individuals can cognitively reconstruct their actions to make them appear morally neutral or acceptable, thereby reducing the internal conflict typically associated with unethical behaviors (Bandura, 2017; Ogunfowora et al., 2022). FWH involves deliberately misrepresenting the time spent on work-related tasks to receive compensation for unworked hours, while MSW refers to intentionally adjusting one’s work pace to either extend the workday or reduce the volume of work completed. Both behaviors can be rationalized through moral disengagement, with individuals justifying these actions as acceptable or necessary (Xu et al., 2023). Employees may resort to euphemistic labeling, describing FWH as merely “adjusting time records” or MSW as “working at a sustainable pace,” thereby softening the unethical connotation of these acts. Empirical evidence supports the notion that moral disengagement is closely linked to unethical behaviors. For instance, Xu et al. (2023) found that employees are more likely to reduce the psychological torture caused by their moral adjustment mechanisms through moral disengagement, thereby demonstrating time theft. Similarly, Sarwar and Song (2025) confirmed that employees with higher levels of moral disengagement are more likely to engage in unethical behaviors. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2b: Moral disengagement is positively associated with FWH.

H2c: Moral disengagement is positively associated with MSW.

In summary, individuals high in Machiavellianism are particularly adept at using moral disengagement mechanisms to justify unethical workplace behaviors, such as time theft. Their manipulative tendencies, coupled with a utilitarian moral outlook, lead them to cognitively reconstruct their actions in a way that minimizes ethical self-sanctions. This enables them to engage in behaviors like FWH and MSW without experiencing significant internal conflict. The moral disengagement functions as a psychological pathway that translates Machiavellian traits into concrete acts of time theft. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2d: Moral disengagement mediates the association between Machiavellianism and FWH; an individual with high Machiavellianism is likely to engage in FWH through moral disengagement.

H2e: Moral disengagement mediates the association between Machiavellianism and MSW; an individual with high Machiavellianism is likely to engage in MSW through moral disengagement.

The moderating role of laissez-faire leadership

Laissez-faire leadership is characterized by minimal intervention in the supervision and direction of subordinates, often resulting in an environment with sparse guidance and infrequent feedback (Skogstad et al., 2007; Desgourdes et al., 2024). In China, the high power distance culture encourages deference to hierarchical structures and discourages open criticism of leaders (Guzman and Fu, 2022; Song et al., 2024). As a result, employees may remain silent even when leadership is disengaged or unresponsive, making laissez-faire leadership more likely to be tolerated and left unaddressed.

However, this passive leadership climate can have important ethical consequences. According to moral disengagement theory (Bandura, 1999), individuals may cognitively distance themselves from their internal moral standards through mechanisms such as moral justification, displacement of responsibility, diffusion of responsibility, and distortion of consequences. In environments where leaders provide little ethical guidance or enforcement, these mechanisms become more accessible. For individuals high in Machiavellianism, who are already inclined to prioritize self-interest and manipulate social contexts (Jahangir et al., 2025), the absence of oversight reduces the psychological costs of unethical behavior. When there is no clear accountability, they may justify their actions as necessary for success, downplay potential harm, or shift responsibility onto others, all of which facilitate moral disengagement (Hu et al., 2023). Empirical research has consistently linked laissez-faire leadership with negative organizational outcomes, including decreased job satisfaction and increased unethical behaviors (Skogstad et al., 2007; Almeida et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2023). This correlation suggests that laissez-faire leadership may exacerbate the impact of Machiavellianism on moral disengagement. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3a: Laissez-faire leadership moderates the relationship between Machiavellianism and moral disengagement, such that higher levels of laissez-faire leadership are associated with a stronger positive relationship between Machiavellianism and moral disengagement.

Moreover, under conditions of laissez-faire leadership, the indirect effect of Machiavellianism on unethical behaviors via moral disengagement may be further amplified. According to moral disengagement theory (Bandura, 1999), individuals can cognitively distance themselves from their internal moral standards through mechanisms such as displacement of responsibility, distortion of consequences, or moral justification, thereby reducing feelings of guilt and loosening moral constraints. In environments lacking leadership oversight and normative regulation, these mechanisms are more easily triggered. As outlined in H3a and H3b, laissez-faire leadership strengthens the positive association between Machiavellianism and moral disengagement. This amplifying effect may, in turn, extend to actual unethical behaviors, such as FWH and MSW. Thus, moral disengagement serves as a key psychological process linking Machiavellian tendencies to both FWH and MSW, particularly under conditions of weak leadership. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3b: Laissez-faire leadership moderates the indirect relationship between Machiavellianism and FWH through moral disengagement, such that this relationship becomes stronger at higher levels of laissez-faire leadership.

H3c: Laissez-faire leadership moderates the indirect relationship between Machiavellianism and MSW through moral disengagement, such that this relationship becomes stronger when laissez-faire leadership is high.

Differences in employee time theft by gender

Gender has been identified as a factor that can influence various aspects of work behavior, including the likelihood of engaging in unethical actions (Nohe et al., 2022; Al-Shatti et al., 2022). While a consistent pattern of gender differences across all unethical behaviors has not emerged, research suggests that male and female might exhibit different susceptibilities to certain unethical acts (Szabó and Jones, 2019; Collison et al., 2021; Jonason et al., 2022). These differences are often attributed to socialization processes and gender role expectations. This implies that the way individuals, regardless of their Machiavellian tendencies, respond to their organizational environment could be gendered (Al-Shatti et al., 2022). Due to the influence of socialization, female may pay more attention to social relationships and norms, which could affect their propensity for unethical behavior. In particular, some studies provide evidence that female show stronger alignment with individualizing moral concerns such as care and fairness, potentially reducing their likelihood to morally disengage in workplace settings, including social media environments, although the specific effects in workplace contexts require further exploration (Hren et al., 2006; Al-Shatti et al., 2022; Mills and Wilner, 2023; Mantello et al., 2023; Culham et al., 2024). Additionally, the development of ethical decision-making rooted in virtue ethics and moral foundation theory may also play a role in enhancing ethical conduct among women (Mills and Wilner, 2023; Culham et al., 2024). Although some of these studies did not directly explore unethical behavior in the workplace, they suggest the impact of gender differences on moral decisions. As a result, even when levels of Machiavellianism are similar, male and female may exhibit different tendencies towards time theft behavior. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4a: There is a difference in the influence of Machiavellianism on FWH of different genders.

H4b: There is a difference in the influence of Machiavellianism on MSW of different genders.

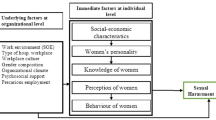

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework guiding this research, focusing on exploring the associations between Machiavellianism and instances of employee time theft, as well as the underlying processes related to these dynamics.

Research methodology

Participants and procedure

This study employs a questionnaire survey to collect data from corporate employees within the Pearl River Delta region. The selected sample encompasses a diverse range of industries, including internet services, education, tourism, and finance. To ensure the quality of the data, a two-stage, cross-sectional survey design was utilized. Each employee is assigned an ID to match responses from the same individual across the two stages. This approach involved the collection of data at two different time points using a matched survey method, which helps to reduce the potential for temporal contamination of variables. The offline investigation was conducted in two phases between August and October 2023: (1) Phase one: the initial phase focused on collecting data for the variables of Machiavellianism, moral disengagement, and laissez-faire leadership. (2) Phase two: 1 month later, a follow-up survey was administered to gather data on the variables of FWH, MSW, and demographic characteristics.

During the data gathering procedure, all respondents signed an informed consent form. The participants were thoroughly briefed on the study’s objectives and told that taking part was entirely at their discretion. No incentives were provided to prevent any potential bias in responses. For this research, a total of 432 questionnaires were recovered. After removing all straight-line responses, unmatched IDs, and questionnaires with fewer than five completed questions to control for careless answers, a total of 350 valid questionnaires were retained. The validity rate of the questionnaires was 81.018%. The demographic characteristics of the sample were as follows: 165 males (47.143%) and 185 females (52.857%); 105 with bachelor’s degrees (30.000%), 70 with master’s degrees (20.000%), 34 with doctoral degrees (9.714%), and 141 with other degrees (40.286%); and 144 persons between the ages of 18–25 (41.143%), 91 (26.000%) aged 26–35, 81 (23.143%) aged 36–45, 34 (9.714%) older than 45.

Measures

The survey instruments used in this study were based on validated scales that are widely adopted in international research. To ensure the accuracy of the measurements and to adapt them to the linguistic and cultural context of the study, a rigorous translation-back translation procedure was employed. Before the main study, a pilot test will be conducted with a small sample to assess the clarity, understandability, and potential biases of the survey instrument. All items in the survey instrument are measured using a 7-point Likert scale to capture the respondents’ attitudes and perceptions. Table 1 shows the measurement items for all constructs.

Machiavellianism was measured using a scale developed by Jonason and Webster (2010), which comprises a total of four items designed to assess the degree to which an individual is pragmatic, manipulative, and self-serving in their interactions. Moral disengagement was adapted from the items developed by Moore et al. (2012), consisting of a total of eight items. This scale primarily reflects the cognitive strategies that individuals employ to disassociate their actions from the moral implications. Laissez-faire leadership is developed by Avolio and Bass (2004), which includes a subset of four items specifically designed to assess this leadership style. Time theft utilizes the scale developed by Harold et al. (2022). This variable was divided into two dimensions, FWH and MSW. Each dimension has three separate questions.

Analytical strategies

This study adopts partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the proposed relationships. PLS-SEM is particularly suitable for exploratory research, as it accommodates small to medium sample sizes, allows for the analysis of complex models with multiple mediating and moderating variables, and facilitates multi-group comparisons (Hair et al., 2019).

Figure 2 presents the empirical analysis procedure adopted, comprising four sequential steps. The first step involves a data quality check, in which normality is assessed based on skewness and kurtosis, and common method bias is examined using Harman’s one-factor test. The second step focuses on evaluating the measurement model through reliability and validity analyses. The third step entails evaluating the structural model, which includes analyzing the hypothesized relationships among constructs and conducting a multi-group analysis to examine the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between Machiavellianism and time theft behavior. The final step involves robustness testing, including a nonlinearity test using the Quadratic effect (QE) method and an endogeneity test based on the Gaussian coupling (GC) method.

Results

Normality test

Although PLS-SEM does not require data to be normally distributed, conducting a normality test is essential to ensure the robustness of the estimation results (Vaithilingam et al., 2024). As shown in Table 1, the skewness values of all variables range from −0.141 to 0.245, while the kurtosis values range from −1.508 to −1.098. These values fall within the acceptable range of −2 to +2 (Vaithilingam et al., 2024). This indicates that the data does not exhibit significant skewness or kurtosis issues, meeting the requirements for analysis.

CMB test

Due to the use of a single data source, potential CMB may distort the measurement results. To mitigate this, we employ a dual approach consisting of procedural and statistical remedies. Procedurally, the study introduces temporal separation in data collection to strengthen the rigor of the research design. Statistically, the study employs Harman’s one-factor test to assess the extent of CMB. The examination revealed that the unrotated first factor accounted for 39.144% of the variance. This value falls short of the critical threshold of 50.00% (Podsakoff et al., 2003), suggesting that CMB is not pronounced and remains within acceptable limits.

Evaluating the measurement model

When applying PLS-SEM for hypothesis evaluation, examining both the measurement and structural models is critical (Hair et al., 2021). The evaluation of the measurement model requires rigorous testing of the reliability and validity of the latent variables. Reliability is ascertained through the evaluation of Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) scores. The benchmark for acceptable internal consistency is typically set above 0.7 for both Cronbach’s α and CR (Hair et al., 2021). As shown in Table 2, all constructs surpass this threshold, attesting to their solid reliability.

Validity is bifurcated into convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity, a critical aspect of validity assessment, is gauged through the average variance extracted (AVE) and factor loading coefficients. An AVE value exceeding 0.5 is indicative of good convergent validity, suggesting that the latent variable accounts for more than half of the variance in its indicators (Hair et al., 2019). Additionally, factor loadings, which represent the strength of the relationship between observed and latent variables, are considered substantial when exceeding 0.7, reinforcing convergent validity (Shevlin and Miles,1998). As shown in Table 2, all constructs not only meet but exceed these standards, with factor loadings above 0.7 and AVEs above 0.5, thereby substantiating their convergent validity.

Discriminant validity is designed to ensure that distinct latent variables are empirically unique and independent. The Fornell-Larcker criterion, a foundational approach in this domain, evaluates discriminant validity by comparing the square root of a latent variable’s AVE with its correlation coefficients against other latent variables. The findings illustrated in Table 3, all AVEs exceed the correlation coefficients with any other latent variable (Hair et al., 2019; Henseler et al., 2015). However, the Fornell-Larcker Criterion has its limitations. It primarily focuses on the correlation between latent variables and does not account for within-construct variance (heterogeneity). Thus, we performed additional analyses using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) method. As shown in Table 3, all HTMT values fall below the recommended threshold of 0.9 (Henseler et al., 2015), further substantiating the discriminant validity among the latent variables.

Evaluating the structural model

Evaluation of the structural model involves not only examining the magnitude and significance of the path coefficients but also assessing multicollinearity among endogenous constructs, the coefficient of determination (R²), and predictive relevance (Q²)(Hair et al., 2019; Legate et al., 2023). In this study, all constructs exhibited acceptable levels of multicollinearity (VIF < 3). Additionally, the R² values for all outcome variables reached the recommended threshold of 0.25 (Henseler et al., 2009), and the Q² values all exceeded 0 (Hair et al., 2019). These results indicate that the model not only explains a substantial proportion of variance in the outcome variables but also demonstrates good predictive relevance.

As shown in Table 4, the analysis conducted using SmartPLS 4.0 and bootstrap resampling (N = 5000) provides empirical support for all proposed hypotheses. Machiavellianism was found to be positively associated with FWH (β = 0.279, p < 0.001) and MSW (β = 0.212, p < 0.001), providing support for H1a and H1b. In addition, a significant positive relationship was observed between Machiavellianism and moral disengagement (β = 0.574, p < 0.001), lending support to H2a. Moral disengagement, in turn, was positively related to both FWH (β = 0.329, p < 0.001) and MSW(β = 0.349, p < 0.001), supporting H2b and H2c. Furthermore, the indirect influences of Machiavellianism on FWH (β = 0.189, p < 0.001) and on MSW (β = 0.200, p < 0.001) through moral disengagement were both statistically significant, thus supporting H2d and H2e. These findings suggest that individuals with higher Machiavellian tendencies may be more likely to exhibit time theft, and that this tendency may be partially accounted for by increased levels of moral disengagement.

The moderated effect analysis was further conducted using SmartPLS 4.0, and the results are presented in Table 5. Laissez-faire leadership significantly moderated the relationship between Machiavellianism and moral disengagement (β = 0.259, p < 0.001), such that the positive association between ML and moral disengagement was stronger under higher levels of laissez-faire leadership. This result supports H3a. Laissez-faire leadership also significantly moderated the indirect relationship between Machiavellianism and FWH through moral disengagement (β = 0.085, p < 0.01). Specifically, the indirect effect was stronger when laissez-faire leadership was higher, supporting H3b. Similarly, laissez-faire leadership significantly moderated the indirect relationship between Machiavellianism and MSW via moral disengagement (β = 0.090, p < 0.01), with the indirect effect being stronger under higher laissez-faire leadership. This finding supports H3c.

The results of the multi-group analysis nonparametric test are shown in Table 6. The analysis revealed a significant difference in the path from Machiavellianism to FWH between males and females (Difference = 0.268, p < 0.05). Males showed a stronger positive relationship between Machiavellianism and FWH compared to female, which supports H4a. This suggests that men who score higher on Machiavellianism are more likely to engage in the behavior of FWH than their female counterparts. In contrast, the path from Machiavellianism to MSW did not show a significant gender difference (Difference = −0.058, p > 0.05). The p value is well above the threshold for statistical significance, indicating no support for H4b.

Robustness checks

The final step in interpreting the results of PLS-SEM is to conduct robustness checks. Specifically, we tested for potential nonlinearity and endogeneity to avoid biased path estimates or incorrect inferences (Hair et al., 2019; Vaithilingam et al., 2024).

To examine nonlinearity, we employed the QE method, which introduces squared predictor terms to capture possible curvilinear relationships between latent constructs (Vaithilingam et al., 2024). This method is recommended for identifying linearity bias that may distort structural explanations. As shown in Table 7, the majority of the quadratic terms were statistically insignificant (p > 0.05), indicating that there are no substantial nonlinear relationships among the constructs (Sarstedt et al., 2020).

To address potential endogeneity, we applied the GC method, a nonparametric technique suitable for PLS-SEM analysis (Sarstedt et al., 2020). As presented in Table 8, although two paths exhibited significant GC estimates, most of the other paths did not yield statistically significant results. This suggests that endogeneity does not systematically affect the model. Therefore, in this study, the relationships among constructs are largely linear, and endogeneity does not pose a significant threat to the validity of the findings.

Discussion

This study investigates the phenomenon of time theft, with particular attention to how FWH and MSW appear within organizational settings. The results highlight the influence of Machiavellianism, moral disengagement, laissez-faire leadership, and gender differences in shaping these forms of unethical behavior.

This study found that Machiavellianism is positively correlated with two forms of time theft: FWH and MSW. Employees with high levels of Machiavellianism are more likely to engage in practices such as falsifying time records or deliberately slowing down their work pace to serve personal interests. This behavioral pattern aligns closely with their manipulative personality traits and is consistent with the core premise of self-presentation theory that individuals strategically manage the impressions they make on others in specific social contexts (Geis and Moon, 1981; Azizoglu and Akdag, 2024). Within the Chinese cultural context, such self-presentation is particularly adaptive. High-Machiavellian individuals may be motivated by the desire to “face-saving” or maintain interpersonal obligations (“renqing”) (Zhang et al., 2011; Xie and Shi, 2022), consciously engaging in time theft to construct an image of diligence and commitment. This strategic impression management enables them to meet the expectations of authority figures and colleagues within hierarchical and collectivist organizational settings, helping them avoid conflict, gain trust, and ultimately maximize their benefits (Liao et al., 2024).

Moreover, the analysis confirmed that moral disengagement plays a mediating role between Machiavellianism and both types of time theft. Rather than acting impulsively, individuals high in Machiavellianism appear to cognitively justify or reframe their actions before engaging in unethical behavior (Bereczkei, 2015; Maftei et al., 2022). By psychologically detaching their actions from moral self-sanctions, they reduce the emotional cost of unethical conduct and are thus more likely to falsify hours or manipulate work speed, particularly in digital systems where human oversight is reduced, and AI-driven monitoring may be subject to strategic exploitation (Ho and Vuong, 2024; Ho and Ho, 2025). This finding reinforces the concept of moral disengagement as a cognitive buffer. This finding is consistent with recent studies suggesting that moral disengagement promotes deviant behavior, particularly in contexts lacking external constraints (Ogunfowora et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023).

Moreover, the study indicates that in workplaces with laissez-faire leadership, individuals high in Machiavellianism tend to exhibit higher levels of moral disengagement, which may, in turn, increase the occurrence of time theft. These findings are consistent with earlier research emphasizing that passive leadership environments may weaken ethical norms and accountability (Skogstad et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2023). This may further reinforce the tendency of individuals to view time theft as a strategic means of shaping a favorable image and advancing their career objectives. This effect may be especially pronounced in the Chinese cultural context. In China, the strong emphasis on face-saving creates social pressure to appear competent (Zhang et al., 2011), loyal, and hardworking, even when actual performance may fall short. Respect for hierarchy discourages open criticism or direct supervision from subordinates (Guzman and Fu, 2022; Song et al., 2024), making it less likely that unethical behavior will be reported or challenged. Furthermore, collectivist values prioritize group harmony and conformity (Zhang et al., 2011), which can encourage individuals to manage impressions to align with perceived group expectations rather than actual outcomes. While traditional Eastern philosophies such as Daoism promote a “non-interventionist” approach to leadership (Bai and Roberts, 2011), this study suggests that in modern organizational settings, a lack of clear direction and oversight may inadvertently foster a permissive climate for ethical deviance.

Finally, multi-group analysis revealed a significant gender difference in the path from Machiavellianism to FWH, with the effect being stronger among male employees. This suggests that male with high-Machiavellian traits are more likely to engage in falsifying work hours compared to female, potentially reflecting gendered social expectations or greater tolerance for risk-seeking behaviors among men (Hogue et al., 2013; Szabó and Jones, 2019). However, no significant gender difference was found for MSW, implying that covert and subjective forms of time theft may be less influenced by gender roles. These results indicate that gender differences in time theft may be context-dependent, with variation tied to the nature and visibility of the unethical behavior rather than a generalized effect across all forms.

Theoretical implications

This research underscores Machiavellianism as a predictor of unethical behaviors in the Chinese workplace, particularly the FWH and MSW in time theft. By demonstrating a positive relationship between Machiavellianism and both FWH and MSW, which extends the applicability of self-presentation theory (Baumeister and Hutton, 1987). This finding emphasizes the tactical deception employed by individuals with Machiavellianism to enhance their perceived productivity, thereby potentially gaining unjustified rewards or recognition (Maftei et al., 2022; Jahangir et al., 2025; Sarwar and Song, 2025). The incorporation of personality traits into the study of time theft moves the focus beyond mere organizational factors to the intrinsic characteristics of individuals, challenging the traditional views of workplace ethics as solely dependent on external controls or organizational culture.

Moreover, this study elucidates the mediating role of moral disengagement in the relationship between Machiavellianism and time theft (FWH and MSW), offering a significant theoretical contribution to the understanding of unethical behavior in organizational settings. The result supports the notion that moral disengagement serves as a cognitive buffer, enabling individuals high in Machiavellianism to rationalize unethical behaviors, which aligns with Bandura’s (2017) conceptualization of moral disengagement as a psychological mechanism that distances individuals from the moral implications of their actions. The mediating role of moral disengagement suggests that the process of rationalization is not merely a post-hoc justification but an active cognitive process that actively facilitates unethical conduct (Ogunfowora et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023). This finding extends the moral disengagement theory by demonstrating its applicability in the context of time theft, thereby broadening the scope of behaviors that can be explained through this theoretical lens.

This study advances theoretical understanding by identifying laissez-faire leadership as a boundary condition that strengthens the link between Machiavellianism and time theft through moral disengagement. While previous research has emphasized the ethical benefits of active leadership styles (Ali et al., 2023), the role of passive leadership in enabling unethical behavior remains underexplored. In Chinese organizational settings, where face consciousness, hierarchical deference, and collectivist norms shape interpersonal dynamics, passive leadership may be culturally tolerated or even misinterpreted as a harmonious form of non-intervention (Leung et al., 2003; Bai and Roberts, 2011; Song et al., 2024). However, this leadership vacuum creates space for high-Machiavellian individuals to rationalize and execute deceptive behaviors (Skogstad et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2023), such as falsifying work hours or slowing down task progress. By incorporating cultural context into the analysis of leadership and unethical behavior, this study extends self-presentation and moral disengagement theories and highlights the culturally contingent nature of ethical climates.

Lastly, this study explored the moderating role of gender in the relationship between Machiavellianism and time theft. The observed gender differences in the propensity to falsify work hours among Machiavellian individuals offer preliminary evidence that societal norms and expectations may influence the expression of Machiavellian traits (Hren et al., 2006; Szabó and Jones, 2019; Al-Shatti et al., 2022). The finding suggests that gender is not merely a demographic characteristic but an influential factor in the manifestation of personality traits and subsequent behaviors within organizational contexts. This perspective aligns with the growing recognition of intersectionality theory, which posits that various aspects of social identity, such as gender, race, and class, interact to shape individuals’ experiences and behaviors (Mantello et al., 2023). By revealing gender differences in the context of Machiavellianism and time theft, this study extends intersectionality theory to the realm of organizational ethics, highlighting the need to consider the interplay of gender with other psychological and situational factors.

Practical implications

This study reveals that employees with high-Machiavellian traits are more inclined to engage in time theft behaviors. The findings suggest that organizations should strengthen personality assessments during recruitment and placement processes, particularly in contexts involving remote work or flexible schedules where superficial diligence can obscure actual performance. Incorporating concise personality screening tools, alongside scenario-based ethical judgment questions in interviews, may help identify individuals with high manipulative tendencies at an early stage. For employees already in the organization, managers should remain vigilant for patterns of behavior that appear productive on the surface but in reality signal avoidance of actual responsibilities. Performance evaluations should also be adjusted to avoid reinforcing deceptive efficiency strategies.

Moreover, the mediating role of moral disengagement highlights the importance of addressing employees’ cognitive justifications prior to unethical behavior. Rather than relying solely on formal rules and codes of conduct, organizations should focus on fostering internalized ethical awareness. Compared to conventional ethics messaging, interventions that center on workplace-based scenarios, such as ethical dilemma simulations, peer-group discussions, or personal reflection journals, are more likely to activate employees’ moral self-regulation and reduce their tendency to rationalize deviant behavior.

Finally, the finding suggest that laissez-faire leadership amplifies the effect of Machiavellianism on moral disengagement suggests that passive leadership styles may weaken managerial oversight and inadvertently foster unethical behaviors. Organizations are therefore encouraged to promote responsibility-oriented leadership, emphasizing proactive supervision and ethical accountability. As emotional AI systems increasingly replace human supervision, understanding employees’ cultural and gender-based trust in algorithmic authority becomes essential to ensure fairness and acceptance (Mantello et al., 2023). This can be achieved through feedback mechanisms that tie employee behavioral outcomes to managerial evaluations, encouraging leaders to remain engaged and responsive. Moreover, the ethical interventions should take group-specific characteristics into account, avoiding a one-size-fits-all training approach and instead promoting more targeted and differentiated strategies.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the valuable insights this study provides regarding the mechanisms through which Machiavellianism, moral disengagement, and laissez-faire leadership influence time theft, several limitations remain and warrant further exploration in future research.

First of all, the use of self-reported questionnaires introduces inherent limitations, particularly when assessing morally sensitive behaviors such as dishonesty. Although a two-wave design was adopted to mitigate common method bias, responses related to unethical conduct, like FWH or MSW, may still be subject to social desirability effects or self-censorship. Given that dishonest behavior is both normatively discouraged and reputationally risky, participants may downplay or rationalize their conduct, thereby compromising data accuracy. Future research could strengthen methodological rigor by incorporating behavioral measures, peer or supervisor ratings, and digital behavioral trace data to triangulate findings and enhance validity.

Moreover, although the study focused on the detrimental aspects of laissez-faire leadership, it adopted a predominantly negative lens. Some literature suggests that under certain conditions, non-interventionist leadership can foster creativity, autonomy, and a sense of ownership among employees. Future research should examine the boundary conditions under which laissez-faire leadership may yield constructive versus destructive outcomes, especially by integrating cultural perspectives and situational moderators.

Finally, this study was conducted in a traditional workplace context; however, the rapid integration of artificial intelligence into managerial and monitoring systems is fundamentally reshaping organizational ethics. AI-powered surveillance, performance analytics, and emotion recognition technologies may alter how individuals engage with time, accountability, and ethical boundaries. In such environments, the mechanisms of moral disengagement may evolve, becoming more digitally mediated or depersonalized. Future research can investigate how AI-driven work contexts influence the enactment and justification of deviant behaviors and whether traditional models of moral reasoning remain applicable.

Conclusion

This study explores the occurrence of time theft in organizational settings, specifically FWH and MSW. We identify that Machiavellianism is a key driver of these unethical behaviors, with moral disengagement serving as a cognitive mechanism that allows individuals to justify their actions. Additionally, laissez-faire leadership is shown to foster an environment conducive to time theft, while gender differences indicate that men are more likely to engage in FWH, though gender does not significantly affect MSW. The findings provide important theoretical and practical insights into the factors that influence unethical behavior in the workplace. By understanding the role of individual traits, leadership styles, and gender, organizations can develop targeted interventions to reduce time theft and promote a more ethical work environment. This research advances the literature on unethical behaviors and contributes to the growthing body of scholarship on time theft, leadership influence, and individual psychological mechanisms.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ali G, Ahmed S, Mubushar M, Gulzar A (2023) Global research on ethical leadership: a bibliometric investigation and knowledge mapping. J Chin Hum Resour Manag 14(2):51–65. https://doi.org/10.47297/wspchrmWSP2040-800504.20231402

Almeida JG, Hartog DND, De Hoogh AH, Franco VR, Porto JB (2022) Harmful leader behaviors: toward an increased understanding of how different forms of unethical leader behavior can harm subordinates. J Bus Ethics 180(1):215–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04864-7

Al-Shatti E, Ohana M, Odou P, Zaitouni M (2022) Impression management on Instagram and unethical behavior: the role of gender and social media fatigue. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(16):9808. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169808

Avolio BJ, Bass BM (2004) Multifactor leadership questionnaire (TM). Mind Garden, Inc., Menlo Park, CA. https://www.mindgarden.com/

Azizoglu O, Akdag LB (2024) Relationships between Machiavellianism and impression management tactics: the moderating role of emotional intelligence. Middle East J Manag 11(4):443–469. https://doi.org/10.1504/MEJM.2024.139588

Bai X, Roberts W (2011) Taoism and its model of traits of successful leaders. J Manag Dev 30(7/8):724–739. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711111150236

Bandura A (1999) Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 3(3):193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Bandura A (2017) Mechanisms of moral disengagement. In: Horn MML, Gabriel ADHS (eds) The Routledge handbook of moral responsibility. Taylor & Francis, pp 72–90. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351155564-4

Baumeister RF, Hutton DG (1987) Self-presentation theory: self-construction and audience pleasing. In: Theories of group behavior. Springer New York, New York, NY, pp 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4634-3_4

Bereczkei T (2015) The manipulative skill: cognitive devices and their neural correlates underlying Machiavellian’s decision making. Brain Cogn 99:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2015.06.007

Brewer G, Abell L (2015) Machiavellianism and sexual behavior: motivations, deception and infidelity. Personal Individ Differ 74:186–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.028

Brock ME, Martin LE, Buckley MR (2013) Time theft in organizations: the development of the Time Banditry Questionnaire. Int J Sel Assess 21(3):309–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12040

Castille CM, Buckner JE, Thoroughgood CN (2018) Prosocial citizens without a moral compass? Examining the relationship between Machiavellianism and unethical pro-organizational behavior. J Bus Ethics 149(4):919–930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3079-9

Català GB, Caparrós BC (2023) The dark constellation of personality, moral disengagement and emotional intelligence in incarcerated offenders. What’s behind the psychopathic personality? J Forensic Psychol Res Pract 23(4):345–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2022.2028395

Collison KL, South S, Vize CE, Miller JD, Lynam DR (2021) Exploring gender differences in Machiavellianism using a measurement invariance approach. J Personal Assess 103(2):258–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2020.1729773

Culham TE, Major RJ, Shivhare N (2024) Virtue ethics and moral foundation theory applied to business ethics education. Int J Ethics Educ 9(1):139–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-023-00181-x

Desgourdes C, Hasnaoui J, Umar M, Feliu JG (2024) Decoding laissez-faire leadership: an in-depth study on its influence over employee autonomy and well-being at work. Int Entrep Manag J 20(2):1047–1065. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00927-5

Fatima D, Abdul Ghaffar MB, Zakariya R, Muhammad L, Sarwar A (2021) Workplace bullying, knowledge hiding and time theft: evidence from the health care institutions in Pakistan. J Nurs Manag 29(4):813–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13222

Fida R, Skovgaard-Smith I, Barbaranelli C, Paciello M, Searle R, Marzocchi I, Ronchetti M (2025) The suspension of morality in organisations: Conceptualising organisational moral disengagement and testing its role in relation to unethical behaviours and silence. Hum Relat 78(8):959–994. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267241300866

Geis FL, Moon TH (1981) Machiavellianism and deception. J Personal Soc Psychol 41(4):766. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.41.4.766

Gürlek M (2021) Shedding light on the relationships between Machiavellianism, career ambition, and unethical behavior intention. Ethics Behav 31(1):38–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1764846

Guzman FA, Fu X (2022) Leader–subordinate congruence in power distance values and voice behaviour: a person–supervisor fit approach. Appl Psychol 71(1):271–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12320

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hair Jr JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S (2021) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: a workbook. Springer Nature, p 197. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/51463

Harold CM, Hu B, Koopman J (2022) Employee time theft: conceptualization, measure development, and validation. Pers Psychol 75(2):347–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12477

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43:115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In: New challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp 277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

Ho M-T, Ho M-T (2025) Three tragedies that shape human life in age of AI and their antidotes. AI Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-025-02316-8

Ho MT, Vuong QH (2024) Five premises to understand human–computer interactions as AI is changing the world. AI Soc 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-01913-3

Hogue M, Levashina J, Hang H (2013) Will I fake it? The interplay of gender, Machiavellianism, and self-monitoring on strategies for honesty in job interviews. J Bus Ethics 117:399–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1525-x

Hollebeek LD, Sprott DE, Urbonavicius S, Sigurdsson V, Clark MK, Riisalu R, Smith DL (2022) Beyond the Big Five: the effect of machiavellian, narcissistic, and psychopathic personality traits on stakeholder engagement. Psychol Mark 39(6):1230–1243. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21647

Hren D, Vujaklija A, Ivanišević R, Knežević J, Marušić M, Marušić A (2006) Students’ moral reasoning, Machiavellianism and socially desirable responding: implications for teaching ethics and research integrity. Med Educ 40(3):269–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02391.x

Hu B, Harold CM, Kim D (2023) Stealing time on the company’s dime: examining the indirect effect of laissez-faire leadership on employee time theft. J Bus Ethics 183(2):475–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05077-2

Hu B, Lu D, Meng L, Zhang Y (2025) When time theft promotes performance: measure development and validation of time theft motives. J Appl Psychol 110(2):256–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001229

Jahangir M, Shah SM, Zhou JS, Lang B, Wang XP (2025) Machiavellianism: psychological, clinical, and neural correlations. J Psychol 159(3):155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2024.2382243

Jonason PK, Webster GD (2010) The dirty dozen: a concise measure of the Dark Triad. Psychol Assess 22(2):420. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019265

Jonason PK, Czerwiński SK, Tobaldo F, Ramos-Diaz J, Adamovic M, Adams BG, Sedikides C (2022) Milieu effects on the Dark Triad traits and their sex differences in 49 countries. Personal Individ Differ 197:111796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111796

Kelly RJ, Hearld LR (2020) Burnout and leadership style in behavioral health care: a literature review. J Behav Health Serv Res 47(4):581–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-019-09679-z

Kornienko DS, Baleva V, Yachmenyova NP (2024) Utilitarian ethics: the impact of the dark tetrad traits and the mechanisms of moral disengagement. Psihol čes ž 45(3):64–75. https://doi.org/10.31857/S0205959224030069

Legate AE, Hair Jr JF, Chretien JL, Risher JJ (2023) PLS‐SEM: prediction‐oriented solutions for HRD researchers. Hum Resour Dev Q 34(1):91–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21466

Leung TK, Yee‐kwong Chan R (2003) Face, favour and positioning—a Chinese power game. Eur J Mark 37(11/12):1575–1598. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560310495366

Liao C, Li Z, Huang L, Todo Y (2024) Just seems to be working hard? Exploring how careerist orientation influences time theft behavior. Curr Psychol 43(31):26064–26079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06252-6

Liu X, Lee BY, Kim TY, Gong Y, Zheng X (2023) Double-edged effects of creative personality on moral disengagement and unethical behaviors: dual motivational mechanisms and a situational contingency. J Bus Ethics 185(2):449–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05135-9

Long X, Wang L, Cao Q, Feng H (2024) The impact of incongruent CSR on time theft: an integration of cognitive and affective mechanisms. Curr Psychol 43(9):7810–7825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04951-0

Maftei A, Holman AC, Elenescu AG (2022) The dark web of Machiavellianism and psychopathy: moral disengagement in IT organizations. Eur’s J Psychol 18(2):181. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.4011

Mantello P, Ho MT, Nguyen MH, Vuong QH (2023) Bosses without a heart: socio-demographic and cross-cultural determinants of attitude toward Emotional AI in the workplace. AI Soc 38(1):97–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01290-1

Mills B, Wilner A (2023) The science behind “values”: applying moral foundations theory to strategic foresight. Futures Foresight Sci 5(1):e145. https://doi.org/10.1002/ffo2.145

Moore C (2015) Moral disengagement. Curr Opin Psychol 6:199–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.018

Moore C, Detert JR, Klebe Treviño L, Baker VL, Mayer DM (2012) Why employees do bad things: moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Pers Psychol 65(1):1–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x

Nohe C, Hüffmeier J, Bürkner P, Mazei J, Sondern D, Runte A, Hertel G (2022) Unethical choice in negotiations: a meta-analysis on gender differences and their moderators. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 173:104189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2022.104189

Ogunfowora BT, Nguyen VQ, Steel P, Hwang CC (2022) A meta-analytic investigation of the antecedents, theoretical correlates, and consequences of moral disengagement at work. J Appl Psychol 107(5):746, https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2021-86667-001

Önalan AS, Özer S (2021) The relationship between personality traits and time theft: a study on hotel employees in TRA1 and TRB2 regions. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20210470005

Piwowar-Sulej K, Iqbal Q (2023) Leadership styles and sustainable performance: a systematic literature review. J Clean Prod 382:134600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134600

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Cheah JH, Ting H, Moisescu OI, Radomir L (2020) Structural model robustness checks in PLS-SEM. Tour Econ 26(4):531–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816618823921

Sarwar Z, Song Z (2025) Machiavellianism and affective commitment as predictors of unethical pro-organization behavior: exploring the moderating role of moral disengagement. Kybernetes 54(3):1601–1623. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-06-2023-0998

Shevlin M, Miles JN (1998) Effects of sample size, model specification and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Personal Individ Differ 25(1):85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00055-5

Sijtsema JJ, Garofalo C, Jansen K, Klimstra TA (2019) Disengaging from evil: longitudinal associations between the Dark Triad, moral disengagement, and antisocial behavior in adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 47:1351–1365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00519-4

Sinclair S (2024) Does it matter whether others are working hard or hardly working? Effects of descriptive norms on attitudes to time theft at work. Int J Sel Assess 32(1):12–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12445

Skogstad A, Einarsen S, Torsheim T, Aasland MS, Hetland H (2007) The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behavior. J Occup Health Psychol 12(1):80. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.1.80

Song LJ, Zhang D et al. (2024) Chinese leadership. In: Oxford research encyclopedia of business and management. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.376

Syed J, Tariq M (2017) Global diversity management. In: Oxford research encyclopedia of business and management. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.001.0001/acrefore-9780190224851-e-62

Szabó E, Jones DN (2019) Gender differences moderate Machiavellianism and impulsivity: implications for Dark Triad research. Personal Individ Differ 141:160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.01.008

Tang TLP, Sutarso T (2013) Falling or not falling into temptation? Multiple faces of temptation, monetary intelligence, and unethical intentions across gender. J Bus Ethics 116:529–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1475-3

Tricahyadinata I, Hendryadi, Suryani, Zainurossalamia ZAS, Riadi SS (2020) Workplace incivility, work engagement, and turnover intentions: multi-group analysis. Cogent Psychol 7(1):1743627. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1743627

Vaithilingam S, Ong CS, Moisescu OI, Nair MS (2024) Robustness checks in PLS-SEM: a review of recent practices and recommendations for future applications in business research. J Bus Res 173:114465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114465

White LK, Valos N, de la Piedad Garcia X, Willis ML (2024) Machiavellianism and intimate partner violence perpetration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 25(5):4159–4172. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380241270027

Xie S, Shi B (2022) The impact of financial deprivation on prosocial behaviour: comparing the roles of face‐saving consciousness versus status/success‐gaining intention. Asian J Soc Psychol 25(2):170–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12475

Xu C, Yao Z, Xiong Z (2023) The impact of work-related use of information and communication technologies after hours on time theft. J Bus Ethics 187(1):185–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05167-1

Zhang J, Wang Y, Gao F (2023) The dark and bright side of laissez-faire leadership: Does subordinates’ goal orientation make a difference? Front Psychol 14:1077357. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1077357

Zhang L, Zhang C, Shen YX, Liu H (2025) Why being labeled “creative” triggers employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior: the role of felt obligation for constructive change and Machiavellianism. J Bus Res 189:115185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2025.115185

Zhang XA, Cao Q, Grigoriou N (2011) Consciousness of social face: the development and validation of a scale measuring desire to gain face versus fear of losing face. J Soc Psychol 151(2):129–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903366669

Zhao S, Ma C (2023) Too smart to work hard? Investigating why overqualified employees engage in time theft behaviors. Hum Resour Manag 62(6):971–987. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22182

Zheng W, Wu YCJ, Chen X, Lin SJ (2017) Why do employees have counterproductive work behavior? The role of founder’s Machiavellianism and the corporate culture in China. Manag Decis 55(3):563–578. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2016-0696

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the High-level Talents Project of Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities (No. yy2024rcsk019), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation Project (No. 2025GXNSFHA069105), and Guangxi Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Project (No. 21CGL002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: CL, PZ, and ZZ; methodology: CL, ZZ, and LS; formal analysis: ZZ and LS; writing—original draft: XF, CL, ZZ, and LS; writing—review and editing: XF, CL, PZ, LS, and ZZ; supervision: PZ and LS; resources: PZ, YL, and LS; investigation: XF, LS, YL, ZZ, and LS; validation: CL, ZZ, YL, and LS; data curation: XF, PZ, and LS.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study involved human participants and their data. All study procedures adhered strictly to the ethical standards set by Chinese institutional and national research ethics committees, as well as the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical guidelines. Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities (Approval Number: 20230601301) on June 13, 2023. The approval is valid for 2 years. The approval covered all aspects of the study, including participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis. Throughout the study, participants’ rights, safety, privacy, and well-being were rigorously protected with the approved protocols and relevant Chinese regulations.

Informed consent

Before the study, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The data collection was conducted between August and October 2023 in the Pearl River Delta region of mainland China, involving full-time employees from various industries such as internet services, education, tourism, and finance. Before completing the survey, each participant received a detailed informed consent form that explained the purpose of the study, the procedures involved, the voluntary nature of participation, the scope of data usage, the measures to ensure anonymity, the potential risks, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Participants were included in the study only after reading and fully understanding this information and providing their signed consent. No material incentives were offered to avoid influencing participant decisions. All questionnaires were completed anonymously, and no personally identifiable information was collected. The data are used solely for academic research purposes and will be published only in anonymized form. All participants were adults aged 18 or above with full legal capacity to consent. The study did not involve minors, patients, refugees, or any other vulnerable populations. Throughout the study, ethical standards were strictly followed to ensure participants’ informed rights, privacy, and data security were fully protected.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, C., Zheng, Z., Feng, X. et al. Ethical decline at work: the role of Machiavellianism and laissez-faire leadership in facilitating time theft in Chinese organizational settings. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1807 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06082-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06082-2