Abstract

This study presents a systematic review to explore teachers’ digital competencies framed by the DIGCOMPEDU model through gamification experiences mediated by technology in higher education. The methodology was based on the PRISMA protocol for systematic literature reviews, and it also includes a directed content analysis of 51 articles as a final sample. Findings present gamified digital teaching practices focused mainly on creating and modifying digital resources. However, these experiences do not consider collaborative actions or using Open Educational Resources. As for the evaluative scope, digitalised gamification teaching has been shown as an educational approach that implements strategies for assessment but does not store learning evidence to check students’ progress and teachers’ teaching adequacy. Finally, the analysed articles’ participants showed a low level of digital competence related to accessibility, meeting student diversity and personalisation of learning pathways during the gamified experiences. The study proposes recommendations to encourage teachers to use DIGCOMPEDU and gamification as guiding approaches to address international priorities on inclusive education. It is suggested that future research lines explore different influential factors on developing teachers’ digital competence when using gamification in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Educational benefits of the technologies’ arrival

The arrival of technology in education brought about a revolution in pedagogical practices. A digital world offers several possibilities in the teaching–learning processes from an organisational perspective and during the teaching action. This transformation favours educational processes by increasing student motivation, personalising learning, allowing ubiquity, and systematising specific actions. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) support including technological and communication resources in developing more equitable and adaptive educational systems (Giannini, 2023). Indeed, including those elements in higher education has been a frequent field of research throughout the last decades, especially since COVID-19. We find increased learning motivation, permanent communication between educational agents and teaching innovation when using technologies (Cevallos et al. 2020). All these changes support the fourth SDG, which focuses on providing a more accessible and relevant learning experience no matter the context or age of the learning situation (UNESCO, 2017).

This educational line’s construction encourages students’ independent and autonomous learning and shared responsibility to improve their cognitive, procedural and attitudinal development (Díaz et al. 2020). It is also possible to generate virtual spaces that endow pedagogical processes through ubiquity (Báez and Clunie, 2019). However, some research shows negative consequences of digitalising the teaching–learning process, such as considering virtual spaces as simple content repositories (Pérez-Berenguer and García-Molina, 2016). The lack of teacher training in digital media also aligns with this previous consequence, showing shortcomings in the design, implementation and evaluation of digitised methodologies (Díaz et al. 2020).

Therefore, it was essential to establish a series of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that would set a digital competence to guide teachers’ training and ensure a positive impact on the educational processes when using digital resources and tools.

Teacher digital competence

The digitisation of the teaching–learning process has become a priority for those involved in higher education (Cabero-Almenara et al. 2020). Achieving meaningful learning through technology means being flexible and critical in using appropriate media. The Council of the European Union (2018) defines teacher digital competence as using technologies to participate in life’s working, social and communicative areas. Thus, digital competence is considered a tool for teachers’ lives so that it can be developed and improved in higher education (De Pablos-Pons et al. 2019).

It is necessary to understand the use and management of digital tools and environments in which students interact to teach them about digital competence nowadays. Thus, teachers need specific skills and knowledge to link their teaching to students’ everyday lives (Sánchez-Caballé et al. 2021). Likewise, developing digital competence involves teachers’ improvement as communicative and technological professionals facing the rising education demands in the classroom related to special education needs, learning styles, and the student–teacher gap (Fernández-Batanero et al. 2022a).

Antonietti et al. (2022) argue that further research is needed on teachers’ perceived level of competence in using technology as part of their teaching, as those professionals who perceive themselves as more capable tend to use a more significant variety of technological resources according to different needs and learning situations. Thus, the European Union proposes a model for assessing the technological competencies of teachers: the European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (DIGCOMPEDU).

DIGCOMPEDU

Given the importance of teachers acquiring digital competence, the European Union developed the DIGCOMPEDU framework (Redecker and Punie, 2017). This model provides an understanding of skills and attitudes that professionals must display in three areas: two address the development of professional and pedagogical skills involved in digital competence (Area 1: Educators’ professional competencies with one dimension; Area 2: Educators’ pedagogic competencies with four dimensions), and a third focuses on promoting and assisting in the students’ digital competence development (Area 3: Learners’ competencies with one dimension).

Figure 1 shows these areas and their numbered dimensions.

The DIGCOMPEDU framework (Redecker and Punie, 2017, p. 8).

For the present study, the authors will focus on area 2, where we find four dimensions: digital resources (dimension 2), teaching and learning (dimension 3), assessment (dimension 4), and empowering learners (dimension 5). The dimensions also present subdimensions that specify how to work more concretely with the topic.

Focusing on the second dimension, teachers must experiment and test by creating and reusing resources and tools that allow them to teach while generating student motivation. The third dimension leads the educator to plan and design to promote collaborative learning. The fourth dimension focuses on teachers obtaining and analysing evidence from their teaching and providing student feedback. Finally, the fifth dimension leads teachers to address students’ personalisation, accessibility and inclusion.

Regarding teachers’ digital competence from the pedagogical perspective, DIGCOMPEDU dimensions involve diversified learning that responds to a combined face-to-face and virtual teaching-learning process, linking it with constant reflection according to students’ needs and interests (Daouk et al. 2016). Therefore, DIGCOMPEDU allows teachers to know to what extent each of the dimensions is considered in their professional action and helps them to connect teaching planning (i.e., resources, variability, connectivity, accessibility) with the development of their digital competence (i.e., different levels of concreteness in the achievement of the DIGCOMPEDU dimensions) (Redecker and Punie, 2017; Zhao et al. 2021). In this way, addressing multiple elements complexifies the teacher’s preparation and the implementation of the teaching action.

Learning digital competence through teacher professional development

The preparation of higher education teachers to perform their functions within the teaching–learning process is broader than their initial training. On the contrary, it is possible throughout their lives, thanks to professional development, by searching for continuous improvement and updates to optimise their teaching practice. Regarding teacher professional development in the field of technologies, Mishra and Koehler (2006) developed the TPACK model, which proposes that teachers develop their technological skills by interweaving content and pedagogical knowledge for effective integration in the teaching process. Although research supports this model for the development of teachers’ digital competence (Drajati et al. 2023), some studies show weaknesses in terms of teacher professional development, especially in the use of information technologies, as it is more focused on technical use than on pedagogical implementation, which results in lower student learning (Fernández-Batanero et al. 2022a). They also show the need to deepen digital pedagogical knowledge to teach resources or identify students’ needs (Pérez-López and Alzás, 2023).

These training deficiencies are reflected in the teachers’ perception since many consider that they have low or medium-low digital competence, particularly in evaluation skills (Basilotta-Gómez-Pablos et al. 2022). At the same time, developing skills for the inclusion of disabled students seems to be underdeveloped by teachers (Fernández-Batanero et al. 2022b; Fernández-Cecero and Montenegro-Rueda, 2023). Thus, although the level of technical skills (access and management of information) and communication skills has an acceptable level in teacher professional development (Pérez-López and Alzás, 2023), it is essential to delve deeper into the digital pedagogical skills to know how these resources are being used to meet diversity in the class.

Experiences associated with DIGCOMPEDU and its connection to digital competence

Research addressing these two elements, DIGCOMPEDU and digital competence of higher education teachers (García-Ruiz et al. 2023; Cabero-Almenara et al. 2020), insists on generating professional training for senior, in-service and preservice teachers to help them adjust to the current society’s needs.

According to DIGCOMPEDU, among the strategies favouring teachers’ digital competence, we observe online courses, such as MOOCs, and peer-to-peer training, which places teachers in a collaborative learning environment (Betancur-Chicué and García-Varcárcel, 2022). Augmented reality, robotics, blogs and the initiation of gamified elements in class sessions seem to be considered in higher education. Likewise, creating and generating digital activities and resources motivates teachers to improve their digital competence (Cabero-Almenara et al. 2021).

However, reflection on practice and student empowerment associated with their digital competence are areas for improvement in teaching in higher education (Bilbao-Aiastui et al. 2021). Therefore, training is the backbone of this process, as teachers are encouraged to progress through area 2 of DIGCOMPEDU. Some active methodologies, such as gamification, are novel means for favouring its development (Cabero-Almenara et al. 2021). Therefore, it is crucial to delve into how gamification is a digital competence vehicle, specifically within the European reference DIGCOMPEDU framework.

Gamification in digital environments and its relationship with DIGCOMPEDU

Gamification is an active methodology defined as ‘the use of game design elements in non-game contexts’ (Deterding et al. 2011, p. 2). Different authors have categorised these game elements, showing diverse interpretations for the gamification approach (Klock et al. 2016; Werbach and Hunter, 2012). Toda et al. (2019) succeeded in developing a consensual taxonomy for education purposes among the scientific community (Denden et al. 2023; Wibisono et al. 2023). The benefits of technologies allow gamified pedagogical processes through diverse applications, access to large amounts of information, immediacy of users’ actions, visualisation of audiovisual material, and interweaving all these elements in a single interface (Koivisto and Hamari, 2019). Thus, gamification becomes a robust framework for systematically observing which digital skills teachers put into practice when designing their ICT-mediated teaching actions to analyse their strengths and weaknesses (Martín-Párraga et al. 2022; Zhernovnykova et al. 2020).

Developing gamified processes in digital environments can show teachers’ ability to develop DIGCOMPEDU’s categories. Concerning the second and third dimensions of this framework (digital resources and teaching and learning), the study by Argueta-Velázquez and Ramírez-Montoya (2017) integrated a gamified system with the presentation of short videos, infographics, and open educational resources (OER) in a MOOC that raised the course completion rate. Aligned with MOOCs, Aparicio et al. (2018) conducted a comparative study between non-gamified and gamified environments, demonstrating that the latter increased student satisfaction, establishing gamification as the most decisive factor for the success of the MOOC by fostering the students’ playful engagement with the course content. On the other hand, regarding the second (digital resources), third (teaching and learning), and fifth (student empowerment) DIFCOMPEDU’s dimensions, Domínguez et al. (2013) created a gamified platform in which they sought student autonomy in their learning by offering a detailed description of activities in an individual competitive environment to achieve badges. However, the assessment was complex as it was set through screenshots, which made the immediate feedback challenging to develop. Finally, more focused on the fifth dimension (learner empowerment), Hassan et al. (2021) created a virtual learning environment that personalised student learning paths, resulting in increased motivation and reduced course dropout rates.

Considering the previous background, we conducted a systematic review based on the PRISMA protocol to analyse which dimensions of the DIGCOMPEDU framework teachers develop through their ICT-mediated gamified teaching and its implications for the teaching–learning processes.

Methods

The study describes the aspects of teachers’ digital competence achieved in gamified classroom experiences in higher education, specifically when information and communication technologiesFootnote 1 (ICT) are implemented in gamified experiences using digital pedagogical resources, and, on the other hand, aim to deepen and reflect on the pedagogical implications of our findings.

Based on the above, this paper poses the following research questions:

RQ1: Which dimensions of the pedagogical competencies of the DIGCOMPEDU framework are put into practice by educators when ICT-based gamified classroom actions are performed?

RQ2: Are the dimensions and subdimensions included in each dimension of the DIGCOMPEDU framework educators’ pedagogical competencies proportionally represented when ICT-mediated gamified classroom actions are developed?

RQ3: Does a possible imbalance in the representation of the DIGCOMPEDU framework elements present educational implications when ICT-mediated gamified classroom actions are developed?

Procedure, materials, and data analysis

The methodology was followed in two stages. In the first phase, the PRISMA protocol was applied to the systematic review of the literature. Subsequently, the documents were analysed qualitatively to identify the digital competence dimensions implemented when ICT-mediated gamified classroom experiences occur. In the second phase, we followed Hsieh and Shannon’s (2005) guidance to analyse teachers’ digital competence. We developed a directed content analysis using the DIGCOMPEDU as a category system (Redecker and Punie, 2017). This model was chosen because it is one of the most recognised frameworks by the scientific community to discuss teachers’ digital competence (Alarcón et al. 2020; Bilbao-Aiastui et al. 2021; Cabero-Almenara et al. 2023; Caena and Redecker, 2019).

PRISMA protocol: initial search

The DIGCOMPEDU framework was officially published in 2017 by the European Commission. However, the authors considered it important to include previous years in the review to cover more possible publications related to ICT, digital competence and gamification. Although the initial search began in January 2021 and was set for 10 years for the review (2011–2021), the authors ended the search in March 2024 for professional and personal reasons. Therefore, the review included data from 2011 to 2024, making a final time frame of 13 instead of 10 years. This decision was successful since we could find relevant contributions between 2021 and 2024, as Fig. 3 shows.

The initial search combined the terms ‘gamification’ and ‘higher education’ through Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and ERIC databases. In the next phase, the search was expanded by applying Boolean operators (AND, OR), adding other descriptors such as ‘ICT’, ‘digital competence’, ‘e-learning’, or ‘online education’. These initial search combinations yielded heterogeneous results in terms of both the number and the specificity of publications. For instance, the combination ‘gamification AND ICT’ produced many articles, yet many were not directly relevant to higher education. Conversely, the string ‘gamification AND online education’ returned a disproportionately small number of results, which lacked the depth required to address the scope of the research questions.

To optimise the search, several alternative search strings were tested to set an appropriate balance between comprehensiveness and specificity levels. These included combinations as follows:

-

‘gamification AND ICT AND higher education’

-

‘gamification AND digital competence AND higher education’

-

‘gamification AND e-learning AND higher education’

-

‘gamification AND online education AND higher education’

However, these strings generated an excessive volume of less relevant studies, resulting in few studies adequately addressing the research topic. After refining the search terms systematically, the most effective and precise combination emerged as ‘(gamification) AND (higher education)’, which resulted in a reasonable number of studies in terms of sample size, aligned with the inclusion criteria and the primary research objectives. The final accepted results in SCOPUS and WoS databases were the same articles.

To ensure the level of consensus in the screening phase, the reviewers (the authors of this paper) were trained to ensure that the level of consensus was adequate (Cohen’s Kappa > 0.8) (Cohen’s Kappa > 0.8), when training was stopped. Finally, the reviewers categorised the articles independently, and the final categorisation included articles on which both reviewers agreed.

PRISMA protocol: systematic search

The final systematic search was conducted between February 2023 and March 2024 using the Scopus database over a search interval of 13 years (from 2011 to 2024), inclusive.

Finally, the best combination of terms used was (Gamification) and ((Higher) AND (Education))) for WoS and ERIC databases, and (gamification) AND (higher PRE/0 education) for SCOPUS database (since this database uses a different boolean system). In the end, 1099 results were obtained. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for filtering results following the PICOS format are shown in Table 1.

The screening phase was conducted after identifying the 1099 results in Scopus and WoS (886) and ERIC (213). According to the criteria, n = 663 results were discarded for the following reasons: n = 407 for not belonging to the area of Social Sciences, n = 241 for not being articles, and n = 15 for not being in the final publication stage, resulting in 436 articles. Subsequently, and after reading the title and abstract, n = 212 articles were eliminated for not being relevant to our study: n = 152 for not dealing with gamification and n = 60 for not dealing specifically with Higher Education, leaving n = 224 records selected to evaluate their eligibility. Finally, after reading the full text of the selected articles, n = 173 were not considered because they were not framed within the concept of gamification mediated by ICTs or did not meet some of the above criteria, which were not detected in the previous filtering phases. Thus, n = 51 records were included in the systematic review. Figure 2 shows a summary of the process.

Analysis of documentary information

The information is analysed using the directed content analysis approach (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). This analysis lets us know how teaching digital competence is implemented during ICT-mediated gamified classroom experiences. For this purpose, we have used the taxonomy proposed by the DIGCOMPEDU that categorises digital competence into three significant areas (Professional competencies, Pedagogical competencies, and Student-related competencies), which are divided into six dimensions of action. For this article, we have focused on the Pedagogical competencies area since, being classroom teaching–learning experiences, this dimension allows us to map the most highlighted aspects of digital competence in this type of experience.

Results

Scientific production on gamified classroom experiences mediated by ICT in Higher Education (2011–2024)

Table 3 shows the summary of the articles analysed. Additionally, the code assigned to each article is presented, which will serve as a reference throughout this study.

As shown in Fig. 3, scientific production on ICT-mediated gamification in higher education has increased recently, whereas in previous years, it was almost nil. Significant scientific interest arises towards this emerging relationship, as 39 of the 51 selected articles have been produced in the last 6 years. Since 2018, publications have experienced significant growth; this may be due to the publication of DIGCOMPEDU, which established a framework on digital skills and encouraged the development of educational interventions through ICT.

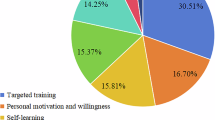

Regarding the nature of the type of study (Fig. 4), the majority are quantitative (58.82%), mixed (23.53%) and qualitative studies (15.69%).

Digital competence of teachers linked to ICT-mediated gamified classroom experiences in Higher Education

The qualitative analysis provides a map of the studies’ main elements of digital competence (DIGCOMPEDU).

One of the most remarkable results is the depth of the model used (DIGCOMPEDU). Based on performance dimensions and subdimensions, the model generated a detailed description of teachers’ digital competence based on empirical evidence. This description allowed us to concretely categorise the teachers’ digital competence by a scientifically validated framework that can serve as a methodological reference in further studies.

Table 2 presents percentages showing the relationship between DIGCOMPEDU’s dimensions and the reviewed articles. The column titled F. appearance indicates the number of articles that address a particular dimension, representing the frequency with which each dimension is discussed within the reviewed studies.

In percentage format, the column % Action shows the articles that engage with a specific dimension related to the final 51 reviewed articles. The % Dimension column represents the proportion of each dimension related to the total number of occurrences across all dimensions.

As shown in Table 2, considering the dimension results, the percentages show a prevalence of Dimension 3, with an occurrence of 42.44%. It is the most recurrent dimension in the reviewed gamified experiences, found in 4 out of 10 studies and standing around twice as high as the other dimensions. Dimension 4 (23.25%) and Dimension 2 (21.40%) are in the next place, leaving Dimension 5 in the last position, with an occurrence of 12.92%.

Regarding the results by specific subdimensions (Tables 3 and 4, see Appendix) and focusing on Dimension 2 (Digital Resources), we observe a prevalence of subdimension ‘Creating and modifying digital resources’ with a percentage of appearance of 74.5%, while very unbalanced results have been observed in the rest of subdimensions: ‘Selecting digital resources’ and ‘Managing, protecting and sharing digital resources’ with a percentage of appearance of 25.5% and 13.7% respectively.

Regarding the results in Dimension 3, focusing on its subdimensions (see Table 2), 96.1% percentage of appearance was obtained in ‘Teaching’, 52% in the ‘Self-regulated learning’ section, 37.3% in ‘Collaborative learning’ and 35.3% in ‘Guidance’.

Focusing on Dimension 4 sections, the results point out a medium-low frequency of occurrence, related explicitly to the subdimensions of ‘Assessment strategies’ and ‘Feedback and planning’, being the most frequently found in the studies with a percentage of occurrence of 49.0% and 47.1% respectively. Behind these results, the subdimension ‘Analysing evidence’ is found, whose low percentage is remarkable (27.5%).

Finally, the results observed in actions linked to Dimension 5 show a medium-low appearance percentage, as in Dimension 4. The most present subdimensions were ‘Actively engaging learners’ (41.2%) and ‘Differentiation and personalisation’ (19.6%). The ‘Accessibility and Inclusion’ subdimension presents a very low percentage of occurrence (7.8%).

The focus on accessibility and inclusion through gamified strategies was found in Grivokostopoulou et al. (2019), Poce (2020), Rincón-Flores et al. (2020) and Tsabary et al. (2019) studies. Points in common related to making the experience accessible, personal and affordable were (a) providing an immersive digital environment, avoiding structural and physical barriers when the gamification was developed, (b) generating personalised feedback regarding the student’s progress, which was related to having collected individualised exercises, (c) adapting the students’ work schedule for a flexible plan facing deadlines and interaction into the gamified environment and (d) using open access materials and environments, such as MOOCs, regarding the transference and dissemination of the experience.

Discussion

RQ1: Which dimensions of the pedagogical competencies of the DIGCOMPEDU framework are put into practice by educators when ICT-based gamified classroom actions are performed?

Regarding RQ1, to explore whether it is possible to identify common elements in teachers’ digital competence (DIGCOMPEDU) when digitalised and gamified classroom actions are developed, in our first approximation, teachers focus on their digital competence, especially for those strategies connected to teaching–learning. At a lower level, we find their digital competence related to evaluation or feedback experiences, applying digital tools, or personalising and individualising the learning process. It is striking that key aspects historically related to digital competence, such as using technologies to facilitate communication and offer personalised itineraries (Arancibia et al. 2020; Cevallos et al. 2020), happen in such a small proportion of the studies.

The analysis shows that teachers reduced the technological component to include a digitalised space to host gamified processes, such as point systems and rewards. These findings are aligned with Pérez-Berenguer and García-Molina’s study (2016), which showed that virtual spaces are mainly used as repositories rather than pedagogical environments. Likewise, a focus is presented on dimension 2 of the DIGCOMPEDU, understood as the knowledge to use and transfer information to digital platforms (i.e., Moodle, Kahoot).

RQ2: Are the dimensions and subdimensions included in each dimension of the DIGCOMPEDU framework educators’ pedagogical competencies proportionally represented when ICT-mediated gamified classroom actions are developed?

RQ2 sought to determine the proportionality in representing DIGCOMPEDU frameworks’ elements in gamified classroom actions mediated by ICTs. According to the results in dimension 2 (Digital Resources), when gamified experiences are developed, teachers prioritise putting into practice their digital competence linked to using these technologies to create and modify their content rather than searching for similar external content made by other teachers. Although not negative, this fact points out the possible failure of governments and educational institutions to create a digital green culture by creating open educational resource banks (OER) and the commitment to educational digital sustainability.

Concerning the results in dimension 3 (Teaching and Learning), teachers can use their digital competence to design and implement gamified experiences using ICT, demonstrating a high level of mastery. However, the low percentage observed in subdimension 3.3 (‘Collaborative Learning’) indicates gaps in effective student collaboration in gamified digital environments. This result may be due to a lack of awareness about the benefits of collaborative learning, inadequate time to foster peer relationships, or a lack of digital competence training for students (Appavoo et al. 2019; Meng et al. 2024). On the other hand, gamified experiences present a low level of guidance and support in learning (35.3%), which suggests, aligned with dimension 5 (‘Empowering Learners’), that teachers do not personalise the teaching regarding their students’ characteristics during the gamification. Thus, they do not consider using digital tools to monitor students and enable the adaptation of the educational process to their student groups.

The results focused on dimension 4 (Evaluation and feedback) show a medium-low frequency of occurrence, with ‘Feedback and Decision Making’ and ‘Evaluation Strategies’ being the most frequently found subdimensions. The percentage of the subdimension ‘Analytical and Evidence of Learning’ differs from other sections due to its significantly lower values. These results are aligned with the Basilotta-Gómez-Pablos et al. (2022) study, which showed that teachers perceive themselves as having a low level of competence when using digital tools for assessment processes.

Regarding the care and treatment of data protection, our study shows that teachers do not prioritise this element during gamified and ICT-mediated experiences, which García-Peñalvo (2021) explains would guarantee ethically designed teaching practices. If we focus on the collection of analytics as evidence of learning, this point is not sufficiently addressed in our study’s sample. This lack of evidence generates uncertainty about how to improve student engagement. Some authors point out the need to significantly analyse their teaching practice, similar to self-evaluation, by collecting data since learning analytics are tools for improving teachers’ digital competence and professional actions when teachers revise, check and re-think what they had planned and what finally happened (Tzimas and Demetriadis, 2021).

Lastly, the results observed for specific actions linked to dimension 5, ‘Empowering Students’, converge with those found in dimension 3 and question some initial expectations. The studies show poor personalisation or individual training itineraries for students’ needs. Similarly, the low results associated with subdimension 5.1, the least present category, show that attention to diversity (i.e., accessibility and inclusion) continues to be an objective instead of a reality in the classroom. This finding is aligned with the teachers’ perception of the difficulty of working with diversity and technologies in the classroom (Fernández-Batanero et al. 2020; Fernández-Batanero et al. 2022b; Fernández-Cecero and Montenegro-Rueda, 2023). Our results show a repetition of common design flaws: the standardisation and homogenisation of teaching.

There is an apparent lack of attention to the accessibility of the content, not only in higher education, but it is a premise for teaching practice at other education levels (CAST, 2024). Therefore, addressing the inclusive nature of technological tools is relevant for future research. Despite the amplifying power of coding and designing adaptive activities or classroom experiences to favour students’ inclusion, regardless of their characteristics, it seems not to be considered a priority in teaching planning. Creating diverse learning itineraries that include a heterogeneous process, addressing disabilities, personal characteristics, or learning difficulties, would be the beginning of the expected improvement in this area of DIGCOMPEDU.

Exploring why this dimension of the DIGCOMPEDU shows such low percentages by university faculties, research suggests that there continues to be a lack of teacher training and, therefore, less awareness of this issue (Baldiris-Navarro et al. 2016; Bartolomé et al. 2018). As several authors propose (Collins et al. 2019; Nieminen, 2024), betting on more robust training in the planning, design, and evaluation of gamified and ICT-mediated experiences would improve the level of teachers’ digital competence, helping them to feel more confident to ensure an inclusive environment for their students.

RQ3: Does a possible imbalance in the representation of the DIGCOMPEDU framework elements present educational implications when ICT-mediated gamified classroom actions are developed?

Finally, concerning RQ 3, the implications of an imbalance in the representation of DIGCOMPEDU elements during gamified actions through ICTs, we can highlight some issues.

Concerning dimension 3, and especially about the low results in subdimensions 3.2 (Guidance) and 3.3 (Collaborative learning), key implications for student learning are identified. Guidance from the teacher during the educational process is essential for addressing doubts and supporting the learning process, contributing to the expansion of students’ knowledge (An et al. 2022). Furthermore, digital collaboration has proven to be an effective method for increasing student satisfaction and improving academic performance (Acosta-Corporán et al., 2022). Collaborative work among students enhances their motivation, allowing them to learn cooperatively, resolve doubts together, and improve relationships in the classroom.

A direct consequence of dimension 4 is the negative impact on student performance when the evaluation process is not transparent and complete. Analysing evidence related to subdimension 4.1 allows the teacher to assess students’ academic performance and create a dynamic plan that adjusts to the needs identified during the teaching process to improve student learning. On the other hand, the lack of feedback limits the evaluation to a simple grade. Teacher feedback is essential in the educational process, as it enables students to identify their strengths and areas for improvement during the learning process. Qualitative assessment provides students with information about the competencies they must focus on to improve (Morris et al. 2021).

Regarding dimension 5, there is a tendency to standardise the learning pathway, which excludes many students who require diverse approaches to achieve the expected curricular competencies on equal terms. The lack of personalisation in the learning process creates knowledge gaps and disengagement, as it fails to connect with the diversity in the classroom, leading to dropout (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, 2023). This situation aligns with the fourth SDG promoted by UNESCO (2017), which advocates for equitable and quality education for all individuals throughout their lives.

Recommendations and future lines of research

Considering the previous discussion, several implications could be addressed regarding teachers’ use of technologies by combining them with a gamified learning experience. We propose some recommendations to work on the identified weaknesses and possible directions to reinforce teachers’ professional development on the issue.

-

Providing feedback is a personalised formative assessment technique that presents empirical evidence on keeping the students engaged in their learning process. Additionally, gamified evaluation techniques help teachers plan long-term evaluations to avoid numerical grades and immediate feedback, which creates an excessive workload for them nowadays (Çekiç and Bakla, 2021; Cigdem et al. 2024).

-

The personalised feedback links to the challenging personalisation of the ICT-mediated process in gamified class situations. Some inclusive pedagogical frameworks, such as the universal design for learning (UDL), could assist teachers in their planning. The UDL (CAST, 2024) presents a scientific proposal regarding different ways to engage students from the emotional and motivational sides to present content by combining different formats, and to allow students to express themselves in diverse ways. Therefore, the UDL is a professional development resource considering its role in training teachers, schools and higher education institutions. Using the UDL, the gamified experience becomes more accessible and could increase the development of teachers’ pedagogical strategies.

-

It seems that a ‘digital green culture’ still needs to work efficiently. Institutional and policy initiatives could promote a more sustainable approach to using gamified tools and ICT resources to help teachers be digitally competent (Lai and Peng, 2019). However, overloading teachers and practitioners to improve their digital competence by themselves presents a huge responsibility if we consider many professional tasks developed in their routine, such as coping with bureaucracy. A national or regional policy regarding any initiative in this line (i.e., creating teachers’ networks, having spaces to share and exchange ideas, training workshops, and OERs) would enhance teachers’ digital competence by discovering new resources and re-using and transforming their creations.

-

An important implication derived from privileging individual learning over collective learning is that educators still work non-connected with their students (and future citizens who will need to work and think with others) (Slamet and Meng, 2025). Discussions and debates mediated by ICT tools, joint decision-making processes when participating in rankings and scorings, or case studies that challenge students’ critical thinking, could be alternatives when using ICT and gamification as teaching approaches (Baena-Morales et al, 2020).

-

Regarding data protection and learning analytics, we point out gamification as a helpful methodological approach to improve teachers’ digital competence by considering students’ performance rates and mapping the progression of students’ answers to the teacher’s strategies. Institutional repositories and ethical committees enhance this side of the teachers’ digital competence.

Looking at the future of this study, a potential direction for the research would be to explore the DIGCOMPEDU dimensions’ interactions in gamified contexts. Analysing the cross-dimensional relationships could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how teachers’ digital competencies are developed and reinforced within gamified educational settings. Additionally, it would be particularly significant to investigate the impact of contextual factors, i.e., institutional, cultural, and regional ones, in developing digital competencies. These factors could significantly shape the effectiveness of gamified teaching practices.

Addressing the interplay of dimensions and the role of contextual influences is a second action line for the authors to offer context-specific insights. We also encourage examining what tools and platforms can effectively support DIGCOMPEDU’s dimensions. Since this study does not cover a comparative analysis within its research objectives, it is proposed to investigate possible patterns in the development of digital competence by using gamification in the academic field where the study was conducted.

Conclusions

This study has revealed that, framed by the DIGCOMPEDU framework, teachers prioritise digital competencies related to teaching and learning in gamified ICT-mediated actions. In contrast, those competencies related to assessment, feedback, and personalised learning are significantly less developed. These results suggest strategies to standardise learning pathways, overlooking the potential of ICT to address individual needs and foster inclusive educational environments. Aligned with it, teachers prefer creating their digital content rather than using open educational resources, reflecting the absence of a sustainable digital culture promoted by higher education institutions.

The study presents some imbalances when combining gamification with the teaching process and improving teachers’ digital competence, which is connected to significant implications for future research. It is highlighted that the lack of adequate planning and personalisation in gamified experiences can affect student engagement, create learning gaps, and even contribute to school dropout, jeopardising the international sustainable development goals to make education equitable and inclusive in higher education. Moreover, while systematic reviews of existing literature provide valuable insights, it is possible that relying solely on published studies may not fully cover all classroom practices. Future research could explore other publications to complete this study’s results.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Many definitions exist for ICTs due to the breadth of the concept and its dependence on the field in which it is applied. One example for this study is given by Cabero (2015), who, when adapting them to the educational context, differentiates them into information and communication technologies (ICT), learn and communication technologies (LCT), and empowerment and participative technologies (EPT). We base our analysis on Cabero’s conceptualisation, which understands the first category as focusing on being “facilitators of information and educational resources for students,” the second as implying “their use as tools that facilitate learning and the dissemination of knowledge,” and the third as viewing them “not merely as educational resources, but also as instruments for participation and collaboration between teachers and students, who do not have to be located in the same space and time” (2015, p. 23). For this study, we will understand ICTs based on the three categories established, as their use depends on how teaching planning integrates technology.

References

Acosta-Corporán R, Martín-García AV, Hernández-Martín A (2022) Nivel de satisfacción en estudiantes de secundaria con el uso de aprendizaje colaborativo mediado por las TIC en el aula. Rev Electrón Educ 26(2):23–41. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.26-2.2

Alarcón R, Del Pilar Jiménez E, de Vicente‐Yagüe MI (2020) Development and validation of the DIGIGLO, a tool for assessing the digital competence of educators Br J Educ Technol 51:2407–2421

Álvarez-Alonso P, Echevarria-Bonet C (2023) Gamificación en tiempos de pandemia: rediseño de una experiencia en educación superior. Rev Eureka Enseñ Divulg Cienc 20(2):220401–220420. https://doi.org/10.25267/Rev_Eureka_ensen_divulg_cienc.2023.v20.i2.2204

An F, Yu J, Xi L (2022) Relationship between perceived teacher support and learning engagement among adolescents: mediation role of technology acceptance and learning motivation. Front Psychol 13:992464. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992464

Antonietti C, Cattaneo A, Amenduni F (2022) Can teachers’ digital competence influence technology acceptance in vocational education? Comput Hum Behav 132:107266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107266

Aparicio M, Oliveira T, Bacao F, Painho M (2018) Gamification: a key determinant of Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) success. Inf Manag 56(1):39–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2018.06.003

Appavoo P, Sukon KS, Gokhool AC, Gooria V (2019) Why does collaborative learning not always work even when the appropriate tools are available? Turk Online J Distance Educ 20(4):11–30. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.640500

Arancibia M L, Cabero J, Marín V (2020) Creencias sobre la enseñanza y uso de las tecnologías de la información y lacomunicación (TIC) en docentes de educación superior Formación universitaria. 13(3):89–100. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062020000300089

Argueta Velázquez MG, Ramírez Montoya MS (2017) Innovación en el diseño instruccional de cursos masivos abiertos con gamificación y REA para formar en sustentabilidad energética. Educ Knowl Soc 18(4):75–96. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks20171847596

Asiksoy G, Canbolat S (2021) The effects of the gamified flipped classroom method on petroleum engineering students’ pre-class online behavioural engagement and achievement. Int J Eng Pedagog 11(5):19–36. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v11i5.21957

Baena-Morales S, Jerez-Mayorga D, Fernández-González FT, López-Morales J (2020) The Use of a Cooperative-Learning Activitywith University Students: A Gender Experience. Sustainability 12(21):9292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219292

Báez CIP, Clunie BCE (2019) Una mirada a la Educación Ubicua. Ried Rev Iberoam Educ Distancia 22(1):325–344. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.22.1.22422

Baldiris-Navarro SMB, Zervas P, Fabregat-Gesa RF, Sampson DG (2016) Developing teachers’ competences for designing inclusive learning experiences. Educ Technol Soc 19(1):17–27. http://www.ifets.info/journals/19_1/3.pdf

Bartolomé A, Castañeda L, Adell J (2018) Personalisation in educational technology: the absence of underlying pedagogies. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 15:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0095-0

Basilotta‑Gómez‑Pablos V, Matarranz M, Casado‑Aranda LA, Otto A (2022) Teachers’ digital competencies in higher education: a systematic literature review. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 19:8–22. 8

Bencsik A, Mezeiova A, Oszene-Samu B (2021) Gamification in higher education (case study on a management subject). Int J Learn Teach Educ Res 20(5):211–231. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.20.5.12

Betancur-Chicué VB, García-Varcárcel A (2022) Necesidades de formación y referentes de evaluación en torno a la competencia digital docente: revisión sistemática. Fonseca 25:133–147. https://doi.org/10.14201/fjc.29603

Bilbao-Aiastui E, Arruti A, Carballedo R (2021) Una revisión sistemática de la literatura sobre el nivel de competencias digitales definidas por DigCompEdu en la educación superior. Aula Abierta 50(4):841–850. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.50.4.2021.841-850

Cabero J (2015) Reflexiones educativas sobre las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC). Rev Tecnol Cienc Educ 1:19–27. https://doi.org/10.51302/tce.2015.27

Cabero-Almenara J, Gutiérrez-Castillo JJ, Barroso-Osuna J, Rodríguez-Palacios A (2023) Digital teaching competence according to the DigCompEdu Framework. Comparative study in different Latin American universities. J N. Approaches Educ Res 12(2):276–291. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2023.7.1452

Cabero‐Almenara J, Osuna JB, Gallego MRR, Palacios-Rodríguez A (2020) La Competencia Digital Docente. El caso de las universidades andaluzas Aula Abierta 49(4):363–372. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie

Cabero‐Almenara J, Guillén‐Gámez FD, Palmero JR, Palacios-Rodríguez A (2021) Classification models in the digital competence of higher education teachers based on the DIGCOMPEDU Framework: logistic regression and segment tree. J e-Learn Knowl Soc 17:1. https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1135472

Caena F, Redecker C (2019) Aligning teacher competence frameworks to 21st century challenges: the case for the European Digital Competence Framework for Educators (Digcompedu). Eur J Educ 54:356–369. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.49.4.2020.363-372

Campillo-Ferrer JM, Miralles-Martínez P, Sánchez-Ibáñez R (2020) Gamification in higher education: impact on student motivation and the acquisition of social and civic key competencies. Sustainability 12:4822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124822

Carrión Candel E, Colmenero Roblizo MJ (2022) Gamification and mobile learning: Innovative experiences to motivate and optimise music content within university contexts. Music Educ Res 24(3):377–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2022.2069524

CAST (2024) Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 3.0. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Çekiç A, Bakla A (2021) A review of digital formative assessment tools: features and future directions. Int Online J Educ Teach 8(3):1459–1485. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1308016

Cevallos Salazar J, Lucas Chabla X, Paredes Santos J, Tomalá Bazán J (2020) Uso de herramientas tecnológicas en el aula para generar motivación en estudiantes del noveno de básica de las unidades educativas Walt Whitman, Salinas y Simón Bolívar, Ecuador. Rev Cienc Pedagóg Innov 7(2):86–93. https://doi.org/10.26423/rcpi.v7i2.304

Chapman JR, Rich PJ (2018) Does educational gamification improve students’ motivation? If so, which games elements work best? J Educ Bus 93:314–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2018.1490687

Cigdem H, Ozturk M, Karabacak Y et al. (2024) Unlocking student engagement and achievement: the impact of leaderboard gamification in online formative assessment for engineering education. Educ Inf Technol 29:24835–24860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12845-2

Collins A, Azmat F, Rentschler R (2019) Bringing everyone on the same journey’: revisiting inclusion in higher education. Stud High Educ 44(8):1475–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1450852

Consejo de la Unión Europea (2018) Recomendación del Consejo, de 22 de mayo de 2018, relativa a las competencias clave para el aprendizaje permanente. Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea

Daouk Z, Bahous R, Bacha NN (2016) Perceptions on the effectiveness of active learning strategies. J Appl Res High Educ 8(3):360–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/jarhe-05-2015-0037

de-Marcos L, García-Cabot A, García E (2017) Towards the social gamification of e-learning: a practical experiment. Int J Eng Educ 33:66–73

Denden M, Tlili A, Salha S, Abed M (2023) Opening up the gamification black box: effects of students’ personality traits and perception of game elements on their engaged behaviors in a gamified course. Technol Knowl Learn 29(2):921–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-023-09701-6

Deterding S, Dixon D, Khaled R, Nack L (2011) From game design elements to gamefulness: defining gamification. In: Lugmayr A, Franssila H, Safran C, Hammounda I (eds) Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: envisioning future media environments. ACM, New York, NY, pp 9–15

Díaz Rosabal EM, Díaz Vidal JM, Gorgoso Vázquez AE, Sánchez Martínez Y, Riverón Rodríguez G, Santiesteban Reyes DC (2020) La dimensión didáctica de las tecnologías de la información y las comunicaciones. Rev Investig Tecnol Inf 8(15):8–15. https://doi.org/10.36825/RITI.08.15.002

Díez-Pascual AM, García Díaz MP (2020) Audience response software as a learning tool in university courses. Educ Sci 10(12):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120350

Domínguez A, Saenz-de-Navarrete J, de-Marcos L, Fernández-Sanz L, Pagés C, Martínez-Herráiz JJ (2013) Gamifying learning experiences: practical implications and outcomes. Comput Educ 63:380–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.020

Drajati NA, So HJ, Rakerda H, Ilmi M, Sulistyawati H (2023) Exploring the Impact of TPACK-based Teacher Professional Development (TPD) program on EFL teachers’ TPACK confidence and beliefs. J Asia TEFL 20(2):300–315

Fernández P, Ceacero-Moreno M (2021) Study of the training of environmentalists through gamification as a university course. Sustainability 13:2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042323

Fernández-Batanero JM, Román-Graván P, Siles-Rojas C (2020) Are primary education teachers from Catalonia (Spain) trained on ICT and disability? Digit Educ Rev 37:288–303. https://doi.org/10.1344/der.2020.37.288-303

Fernández-Batanero JM, Montenegro-Rueda M, Fernández-Cerero J, García-Martínez I (2022a) Digital competences for teacher professional development. Systematic review. Eur J Teach Educ 45(4):513–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1827389

Fernández‑Batanero JM, Cabero‑Almenara J, Román‑Graván P, Palacios‑Rodríguez A (2022b) Knowledge of university teachers on the use of digital resources to assist people with disabilities. The case of Spain. Educ Inf Technol 27(7):9015–9029. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10965-1

Fernández-Cecero J, Montenegro-Rueda M (2023) Digital competence and disability: a qualitative approach from the perspective of university teachers in Andalusia (Spain). J Contin High Educ 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2023.2265107

Fonseca CSC, Zacarias M, Figueiredo M (2021) MILAGE LEARN+: a mobile learning app to aid the students in the study of organic chemistry. J Chem Educ 98(3):1017–1023. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c01231

Fotaris P, Mastoras T, Leinfellner R, Rosunally Y (2016) Climbing up the leaderboard: an empirical study of applying gamification techniques to a computer programming class. Electron J e-Learn 14(2):94–110

García-López IM, Acosta-Gonzaga E, Ruiz-Ledesma EF (2023) Investigating the impact of gamification on student motivation, engagement, and performance. Educ Sci 13(8):8–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080813

García-Peñalvo FJ (2021) Avoiding the dark side of digital transformation in teaching. An institutional reference framework for e-learning in higher education. Sustainability 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042023

García-Ruiz R, Buenestado-Fernández M, Ramírez-Montoya MS (2023) Assessment of Digital Teaching Competence: instruments, results and proposals. Systematic literature review. Educación XX1 26(1):273–301. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.33520

Giannini S (2023) Generative AI and the future of education. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), pp 1–8

Grey S, Gordon NA (2023) Motivating students to learn how to write code using a gamified programming tutor. Educ Sci 13:230. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030230

Grivokostopoulou F, Kovas K, Perikos I (2019) Examining the impact of a gamified entrepreneurship education framework in higher education. Sustainability 11:5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205623

Guardia JJ, Del Olmo JL, Roa I, Berlanga V (2019) Innovation in the teaching–learning process: the case of Kahoot! Horizon 27(1):35–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-11-2018-0035

Hassan MA, Habiba U, Majeed F, Shoaib M (2021) Adaptive gamification in e-learning based on students’ learning styles. Interact Learn Environ 29(4):545–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1588745

Hernández-Fernández A, Olmedo-Torre, Peña M (2020) Is classroom gamification opposed to performance. Sustainability 12:9958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239958

Hinojo-Lucena FJ, García GG, Marín JAM, Rodríguez JMR (2021) Gamificación por insignias para la igualdad y equidad de género en Educación Superior. Prism Soc: Rev Investig Soc 35:184–198. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/3745

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288

Klock ACT, Gasparini I, Pimenta MS (2016) 5W2H Framework: a guide to design, develop and evaluate the user-centered gamification. In: Proceedings of the 15th Brazilian symposium on human factors in computer systems—IHC’16. Association for Computing Machinery (Eds.), ACM Press, pp. 1–10

Koivisto J, Hamari J (2019) The rise of motivational information systems: a review of gamification research. Int J Inf Manag 45:191–210

Krishnan S, Blebil AQ, Dujaili JA, Chuang S, Lim A (2023) Implementation of a hepatitis-themed virtual escape room in pharmacy education: a pilot study. Educ Inf Technol 28:14347–14359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11745-1

Kyewski E, Krämer NC (2018) To gamify or not to gamify? An experimental field study of the influence of badges on motivation, activity, and performance in an online learning course. Comput Educ 118:25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.11.006

Lai YC, Peng LH (2019) Effective teaching and activities of excellent teachers for the sustainable development of higher design education. Sustainability 12(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010028

Lara-Cabrera R, Ortega F, Talavera E, López-Fernández D (2023) Using 3-D printed badges to improve student performance and reduce dropout rates in STEM higher education. IEEE Trans Educ 66(6):612–621. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2023.3281767

Lin TA, Ganapathy M, Kaur M (2018) Kahoot! it: gamification in higher education. Pertanika J Soc Sci Humanit 26(1):565–582

Macías-Guillén A, Díez RM, Serrano-Luján L, Borrás-Gené O (2021) Educational hall escape: increasing motivation and raising emotions in higher education students. Educ Sci 11:527. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090527

Mahmud SND, Husnin H, Tuan Soh TM (2020) Teaching presence in online gamified education for sustainability learning. Sustainability 12:3801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093801

Martínez-Jiménez R, Pedrosa-Ortega C, Licerán-Gutiérrez A, Ruiz-Jiménez MC, García-Martí E (2021) Kahoot! As a tool to improve student academic performance in business management subjects. Sustainability 13:2969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052969

Martín-Párraga L, Palacios-Rodríguez A, Gallego-Pérez OM (2022) Do we play or gamify? Evaluation of gamification training experience to improve the digital competence of university teaching staff. Alteridad—Rev Educ 17(1):36–49. https://doi.org/10.17163/alt.v17n1.2022.03

McIntosh D, Al-Nuaimy W, Al Ataby A, Sandall I, Selis V, Allen S (2023) Gamification approaches for improving engagement and learning in small and large engineering classes. Int J Inf Educ Technol 13(9):1328–1337. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2023.13.9.1935

Meng C., Zhao M., Pan Z et al. (2024) Investigating the impact of gamification components on online learners’ engagement. Smart Learn. Environ 11(47):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00336-3

Mishra P, Koehler MJ (2006) Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for teacher knowledge. Teach Coll Rec: Voice Scholarsh Educ 108(6):1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Morris R, Perry T, Wardle L (2021) Formative assessment and feedback for learning in higher education: a systematic review. Rev Educ 9(3):e3292. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3292

Murillo-Zamorano LR, López-Sánchez JA, López-Rey MJ, Bueno-Muñoz C (2023) Gamification in higher education: the ECOn+ star battles. Comput Educ 194:104699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104699

Nieminen JH (2024) Assessment for Inclusion: rethinking inclusive assessment in higher education. Teach High Educ 29(4):841–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.2021395

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2023) Digital equity and inclusion in education. EDU/WKP(2023),14. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Pérez-Berenguer D, García Molina J (2016) Un enfoque para la creación de contenido online interactivo Rev Educ Distancia 51:1–24

De Pablos JM, Colás MP, López Gracia A, García-Lázaro I (2019) Los usos de las plataformas digitales en la enseñanza universitaria. Perspectivas desde la investigación educativa. Redu Rev Docencia Univ 17(1):10–59. https://doi.org/10.4995/redu.2019.11177

Paľová D, Vejačka M (2022) Implementation of gamification principles into higher education Eur J Educ Res 11(2):763–779. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.11.2.763

De la Peña-Esteban FD, Lara-Torralbo JA, Lizcano-Casas D, Burgos-García MC (2020) Web gamification with problem simulators for teaching engineering J Comput High Educ 32(1):135–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-019-09221-2

Pereira A, Wahi M (2021) Development and testing of a role-playing gamification module to enhance deeper learning of case studies in an accelerated online management theory course. Online Learn 25(3):101–127. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v25i3.2273

Pérez-López E, Alzás García T (2023) La competencia digital y el uso de herramientas Tecnológicas en el profesorado universitario Rev Estilos Aprendiz 16(31):69–81. https://doi.org/10.55777/rea.v16i31.5364

Pérez-López IJ, Navarro-Mateos C, Mora-González J (2023) El impacto de un doble breakout digital en un proyecto de gamificación. Retos 50:761–768. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v50.99960

Pertegal-Felices ML, Jimeno-Morenilla A, Sánchez-Romero JL, Mora-Mora H (2020) Comparison of the effects of the Kahoot tool on teacher training and computer engineering students for sustainable education. Sustainability 12(11):4778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114778

Poce A (2020) A massive open online course designed to support the development of virtual mobility transversal skills: preliminary evaluation results from European participants. Educ Cult Psychol Stud 21:255–272. https://doi.org/10.7358/ecps-2020-021-poce

Rahman R, Ahmad S, Hashim UR (2018) The effectiveness of gamification technique for higher education students engagement in polytechnic Muadzam Shah Pahang, Malaysia Int J Educ Technol High Educ 15(41):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0123-0

Redecker C, Punie Y (2017) European framework for the digital competence of educators: DIGCOMPEDU. Publications Office of the European Commission, Joint Research Centre

Reyes-de-Cózar S, Pérez-Escolar M, Navazo-Ostúa P (2022) Digital Competencies for New Journalistic Work in Media Outlets: A Systematic Review. Media and Communication 10(1):27–42. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4439

Rincón-Flores EG, Mena J, Ramírez-Montoya MS, Ramirez-Velarde R (2020) The use of gamification in xMOOCs about energy: effects and predictive models for participants’ learning Australas J Educ Technol 36(2):43–59. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4818

Rosa-Castillo A, García-Pañella O, Roselló-Novella A, Maestre-Gonzalez E, Pulpón-Segura A, Icart-Isern T, Solà-Pola M (2023) The effectiveness of an Instagram-based educational game in a Bachelor of Nursing course: an experimental study. Nurse Educ Today 70:103656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103656

Sailer M, Sailer M (2021) Gamification of in-class activities in flipped classroom lectures. Br J Educ Technol 52:75–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12948

Sánchez-Caballé A, Gisbert-Cervera M, Esteve-Món F (2021) Integrating digital competence in higher education curricula: an institutional analysis. Educar 57(1):241–258. https://doi.org/10.5565/REV/EDUCAR.1174

Santos-Guevara BN, Acuña López A (2020) Gamification and Remind App: an applied experience in a professional competencies development workshop Int J Eng Pedagog 10(2):32–44. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v10i2.11632

Seidlein AH, Bettin H, Franikowski P, Salloch S (2020) Gamified E-learning in medical terminology: the TERMInator tool. BMC Med Educ 20:284. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02204-3. 1-10

Slamet TI, Meng C (2025) Gamification in collaborative learning: synthesizing evidence through meta-analysis. J Comput Educ 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-024-00349-4

Suárez-López MJ, Blanco-Marigorta AM, Gutiérrez-Trashorras AJ (2023) Gamification in thermal engineering: does it encourage motivation and learning? Educ Chem Eng 45:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2023.07.006

Suartama IK, Simamora AH, Susiani K, Suranata K, Yunus M, Tisna MS GD (2023) Designing gamification for case and project-based online learning: a study in higher education. J Educ E-Learn Res 10(2):86–98. https://doi.org/10.20448/jeelr.v10i2.4432

Temel T, Çesur K (2024) The effect of gamification with Web 2.0 tools on EFL learners’ motivation and academic achievement in online learning environments. SAGE Open 14(2):215824402311997. https://doi.org/10.1177/215824402311997

Toda AM, Klock ACT, Oliveira W, Palomino PT, Rodrigues L, Shi L, Bittencourt I, Gasparini I, Isotani S, Cristea AI (2019) Analysing gamification elements in educational environments using an existing gamification taxonomy. Smart Learn Environ 6(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-019-0106-1

Torrado Cespón M, Díaz Lage JM (2022) Gamification, online learning and motivation: a quantitative and qualitative analysis in higher education. Contemp Educ Technol 14(4):ep381. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/11374

Truskowska E, Emmett Y, Guerandel A (2023) Digital badges: an evaluation of their use in a psychiatry module. Asia Pac Scholar 8(2):47–56. https://doi.org/10.29060/taps.2023-8-2/oa2869

Tsabary E, Savage D, Ogborn D, Beckett C, Szigetvári A, Beverley J, Del Angel LN, Leblond-Chartrand J, Park S (2019) Inner Ear: a tool for individualizing sound-focused aural skill acquisition. J Music Technol Educ 12(3):261–278. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte_00010_1

Tsai C-Y, Chen Y-A, Hsieh F-P, Chuang M-H, Lin C-L (2024) Effects of a programming course using the GAME model on undergraduates’ self-efficacy and basic programming concepts. J Educ Comput Res 62(3):702–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/073563312311997

Tsay CH, Kofinas A, Luo J (2018) Enhancing student learning experience with technology-mediated gamification: an empirical study. Comput Educ 121:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.01.009

Tzimas D, Demetriadis S (2021) Ethical issues in learning analytics: a review of the field. Educ Tech Res Dev 69:1101–1133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09977-4

UNESCO (2017) UNESCO moving forward the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: 1–22. Document code: BSP-2017/WS/1. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247785

Waluyo B, Phanrangsee S, Whanchit W (2023) Implementing gamified vocabulary learning in asynchronous mode Online J Commun Media Technol 13(4):e202354. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v34i1/136-156

Werbach K, Hunter D (2012) For the win: how game thinking can revolutionize your business. Wharton Digital Press

Wibisono G, Setiawan Y, Aprianda B, Cendana W (2023) Understanding the effects of gamification on work engagement: the role of basic need satisfaction and enjoyment among millennials. Cogent Bus Manag 10(3):2287586. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2287586

Yang QF, Lian LW, Zhao JH (2023) Developing a gamified artificial intelligence educational robot to promote learning effectiveness and behavior in laboratory safety courses for undergraduate students. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 20:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00391-9

Zainuddin Z, Alba A, Gunawan T, Armanda D, Zahara A (2023) Implementation of gamification and bloom’s digital taxonomy-based assessment: a scale development study with mixed-methods sequential exploratory design. Interact Technol Smart Educ 20(4):512–533. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-02-2022-0029

Zamora-Polo F, Corrales-Serrano M, Sánchez-Martín J, Espejo-Antúnez L (2019) Nonscientific university students training in general science using an active-learning merged pedagogy: gamification in a flipped classroom. Educ Sci 9:297. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040297

Zhao Y, Pinto-Llorente AM, Sánchez Gómez MC (2021) Digital competence in higher education research: a systematic literature review. Comput Educ 168:104212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104212

Zhernovnykova OA, Peretiaha LY, Kovtun AV, Korduban MV, Nalyvaiko OO, Nalyvaiko NA (2020) The technology of prospective teachers’ digital competence formation by means of gamification. Inf Technol Learn Tools 75(1):170–185. https://doi.org/10.33407/itlt.v75i1.3036

Zorrilla-Pantaleón MEZ, García‐Saiz D, De la Vega A (2021) Fostering study time outside class using gamification strategies: an experimental study at tertiary‐level database courses. Comput Appl Eng Educ 29(5):1340–1357. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22389

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMB-T: conceptualisation, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, supervision, and editing. SRC: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and writing—original draft. IG-L: conceptualisation, investigation, and writing—original draft, supervision, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study does not involve human participants; their personal or biological data and the ethical approval to use them were unnecessary since the authors developed a systematic review by working with empirical studies.

Informed consent

This study does not involve human participants, so their consent was not required. The nature of this study (a systematic review) did not require to inform any human participant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barroso-Tristán, J.M., García-Lázaro, I. & Reyes-de-Cózar, S. Gamification in digital environments and the development of teachers’ digital competence: a systematic review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1834 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06115-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06115-w