Abstract

The Report on the Work of the Government, an official speech delivered by the Premier of the State Council every year at the second session of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, which reviews the government work in the past year and lays out the overall requirements and policy orientation for economic and social development and the major tasks to be undertaken in the current year, serves as an important resource for understanding the current conditions in China for the rest of the world. Together with its translated versions, the Report plays a key role in the construction of China’s foreign discourse system. The integration of critical and conceptual blending perspectives into translation studies has proven to be a promising academic pursuit for hypothesizing the potential ideological effects on recipients as a result of a series of online blending operations prompted by the (translated) text in their mind, at least as far as metaphorical expressions are concerned. Taking simple words such as the pronoun WE and the proper noun CHINA as examples, this paper aims to demonstrate that such a tripartite disciplinary integration—i.e., translation studies, critical discourse analysis, and conceptual blending theory—can be extended to the analysis of discursive phenomena that are less eye-catching or exotic compared with metaphor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Creative metaphorical expressions often strike people as attractive or exotic compared with more entrenched metaphorical expressions or other conventional but plainer uses of language, such as referencing, framing, and analogical or counterfactual reasoning. When more than one language is at stake, e.g., when a systematic comparison is being made between equivalent corpora of text from different (typically two) languages, with an eye on the mental imageries evoked in the mind of the recipients, i.e., a field of an academic pursuit established and known as translation studies (TS), the continuum of attractiveness may take on a new dimension. Namely, what is generally more interesting is not (only) an expression of a particular type and length in a text per se, whether exotic or not, but formal discrepancies between (patterns of) counterpart expressions and, in light of the blending theory, conceptual discrepancies prompted by those expressions captured in the form of blending networks.

Such is an approach to TS pioneered by Mandelblit (1997), who compared the blending networks prompted by constructional structures of counterpart clauses from an original English text and its Hebrew translated version. The examples selected are all ‘isolated sentences’ whose ‘textual context or predefined communication setting’ has been stripped off (Mandelblit, 1997, p 177; original emphasis) so that, as hypothesized by the analyst, any formal choice made by the translator is most likely due to parameters intrinsic to the languages per se, i.e., the vocabulary and/or grammatical constructions available, maximally immune to rhetorical or pragmatic factors such as argumentation, coherence, implicature, presupposition, etc.

In contrast, for a critical discourse analyst who may have reservations about the validity of the blending theory or the general theses on which this and other cognitive linguistic models are based (e.g., Wodak 2006), the decontextualized sentences discussed in Mandelblit (1997) are of little interest. Instead, the focus would be on revealing the strategic purposes that a text or discourse is believed to have the potential to fulfill (see Fairclough (1993) for a convenient technical differentiation between ‘text’ and ‘discourse’) by examining the different layers or ‘levels of context’ (see, e.g., Reisigl and Wodak, 2016, pp 30–31) in which the text/discourse is embedded.

One of the pioneers who conducted TS taking into account macro-level contextual factors, such as the ideologies underlying the translation process, is Tian (2017a, 2017b). On the basis of Fairclough’s (1992) model of a three-dimensional discourse analytical framework, Tian (2017b) proposed a similar tripartite model in which translation is seen as a doubly nested network of ‘social practice’, of which ‘translation practice’ constitutes a part, of which, in turn, the ‘translated text’, as its end product, constitutes a part. Accordingly, a formal choice made within the perimeter of the affordances of the target language is seen as motivated by the purposes it is intended to serve on the part of the subjects that support, finance, authorize, initiate, implement, etc., the practice of translation.

There are also researchers committed to a cognitive linguistic approach to critical discourse studies, contending that some of the theoretical models developed in Cognitive Linguistics (CL) are especially suited for the interpretation stage of critical analysis (e.g., Hart 2010), a stage that has borne the brunt of the criticisms regarding validity (see for an overview Breeze 2013; Hart 2014b; see also O’Halloran 2003; Widdowson 2004). One of the models designed to formalize the conceptualization processes that linguistic signs are hypothesized to activate and which thus ‘sit quite comfortably in CDA’ (Hart, 2008: 24) is conceptual blending theory (CBT) (Fauconnier and Turner 1996, 2002). Hart (2008) discussed the advantages of CBT over conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) (Lakoff and Johnson 1980), which is a theory of ‘conceptual organization’ (Hart 2010, p 25) when being applied to critical analysis, and concluded that CBT ‘fit[s] within the socio-cognitive approach to CDA in particular’ (Hart 2008, p 103; see also Hart (2014a)).

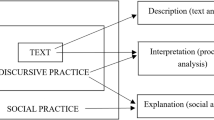

Wang (2023) went a step further and initiated an approach to metaphor translation studies (MTS)Footnote 1 in a generally ‘transdisciplinary’ spirit (Chiapello and Fairclough 2002; Fairclough 2005; see also ‘integrationist model’ in van Leeuwen (2005)) by integrating perspectives from both CDA and CBT, an approach that could be designated CBT-CDA-MTS. His rationale is that CDA, CBT, and TS have been shown at the theoretical level to be highly compatible academic theories/practices and that each two of the trio—i.e., CDA-TS, CBT-TS, and CBT-CDA—have independently proven to be effective and fruitful disciplinary integration in explicating certain types of discursive-conceptual phenomena, especially metaphorical ones (see Fig. 1).

Transdisciplinarity: CDS-TS, CDS-CBT, CBT-TS (adapted from Wang 2023, p 137).

However, since on the one hand, none of these theories/practices is particular about metaphor—indeed, notably, what Fauconnier and Turner aspire for is a model that borders on as it were, omnipotence, one that is applicable to not only metaphors but a wider array of conceptual phenomena such as counterfactuals, puns, mathematical calculations, etc.—and on the other hand, language as we see and use, although pervasive, is by no means uniformly metaphorical in nature, extending this tripartite model beyond metaphors, dropping the ‘M’ in the nomenclature to derive CBT-CDA-TS, is at least theoretically enticing and probable. However, labeling it as such does not necessarily make the thing labeled conceptually coherent, and as is the case with categorical expansion in general, even ‘mapping a coherent space [e.g., CBT-CDA-MTS] onto a conceptually incoherent one [e.g., CBT-CDA-TS] is not enough to give the incoherent space new conceptual structure’ (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p 272).

Thus, one of the aims of this paper is gap bridging—i.e., to explore how the TS of discursive phenomena other than metaphor can be approached from the dual and integrated perspectives of CDA and CBT. The data used in this study are fully contextualized linguistic expressions selected from the political discourse of the Report on the Work of the Government (hereinafter referred to as the Report), delivered on March 5th, 2024, by Li Qiang, Premier of the State Council, and its English-translated version. Another aim, which is less ambitious, is to show how important context is for a more in-depth understanding of discursive phenomena as common as referencing via deictics and proper nouns. A third one, which is more practical, is to unveil the local conceptual mechanisms subserving the production (and consumption) of some of the counterpart expressions in the English version of the Report and to arrive at a global understanding of their joint ideological effects.

TS on the Report: a brief review

TS on the Report has gained strong momentum in the past 15 years, perhaps partially in response to the call of ‘Tell China’s Story Well’ by President Xi Jinping since 2013. Most of these studies are comparative in nature, as is the case with TS in general. Usually, the comparison is between an original Report and one of its translated versions (typically English) in relation to their stylistic features at a certain level (e.g., lexical, clausal, and textual). In addition to case studies of the Report of a certain year, a distinction can be made between studies in which a comparison is made between Reports from different years (during a particular time period) and studies in which a comparison is made between a Report and a more or less equivalent official political text (e.g., Report to the National Congress of the Communist Party of China or State of the Union Address, hereinafter referred to as SUA) from the same year—i.e., a distinction between diachronic and synchronic studies. A further distinction can be made with respect to methodology, e.g., between studies that are corpus-based and whose results are statistically verifiable and studies that do not resort to corpus techniques (proper), although admittedly, studies in which statistics are collected manually (and scientifically but painstakingly) can still be labeled quantitative. TS on the Report can also be experimental. For example, Wu and Zhao (2013) reported the results of a readership survey on the acceptability of the English-translated version of the 2011 Report from native speakers. A paradigmatic distinction can be made between studies that focus primarily on the ‘norms’ of translation (Toury 1995) that translators (have to) abide by and the strategies that they adopt as a result, embodied by the linguistic choices that they make, i.e., studies that are carried out top-down, and studies that focus on the linguistic/stylistic choices per se, i.e., studies that are carried out bottom-up. With respect to norm/strategy-oriented studies, one further dimension of comparison is also possible, i.e., between the two distinct but comparable types of intellectual activity of translation and interpreting. In Hu and Tao (2012) and Pan and Sheng (2021), Reports are employed as a reference corpus to shed light on the different norms that interpreters conform to when interpreting at the press conferences during the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) period.

Employing corpus tools, Wu (2014) closely examined the textual features of the translated text of the 2011 Report by contrasting it against the 2011 SUA. At the lexical level, the Report has a lower (standardized) type-token ratio, is richer in content words, uses more nouns and adjectives and fewer verbs, and is more complicated and demanding in general. At the clausal level, its sentences are generally longer, and there are more coordinations and fewer subordinations. On the whole, he concluded (ibid: 121), the English version of the 2011 Report is less reader-friendly than the 2011 SUA is, which is also the case between their 2010 counterparts. Invoking BNC and SUAs, Li and Hu (2017) conducted a keyword analysis of the English version of the Reports from 2000 to 2014. Referenced against BNC, the connective and ranks 2nd on the keyword list for the Report corpus, but does not appear in the list for the counterpart SUA corpus (where only the first ten key words are shown). Another function word that ranks high (i.e., 4th) on the Reports list is will, which is a ‘median value’ modal verb (Halliday 2000). Similar results are obtained by Tian (2022), who found that the average value of modality in the source corpus (Reports from 2000 to 2020) is markedly greater than that in the target corpus and that a large number of the high-value modal verbs in the source are translated into lower-value ones in the target. Zhu (2011b) investigated the ‘translation universals’ (Baker et al. 1993) from a corpus composed of English-translated versions of Chinese political documents, which includes the Reports from 2000 to 2009, and reported that explicitation, normalization, leveling out, and complication—not simplification—are evident in the translated text.

Several researchers have noted that repetition is a prominent feature of Chinese political text and are interested in, inter alia, the strategies that translators (have to) adopt to avoid redundancy in translation (e.g., Wu 2010). In addition, as noted, English versions of Chinese political texts are generally less coherent or structured than equivalent texts originally written in English, such as SUAs. Hu et al. (2012) suggested that to facilitate understanding, more connectives should be used in English translations to clarify sentential relationships. Some researchers have also investigated the strategies deployed to translate ‘cultural-specific items’ (Aixelá 1996) in the Reports, such as words with Chinese characteristics (e.g., Li, 2010; Wang 2020). Si and Gao (2019) compared the distribution of ‘graduation resources’ (Martin and White 2005) in the 2019 Report and its English translated version and discovered that many of the ‘infusing’ resources in the source are translated into ‘isolating’ resources in the target and that rhetorical devices such as metaphor, parallelism and inversion are commonly exploited in the translation of graduation resources. As concluded in, e.g., Lu and Wang (2016), flexible wording is commonplace in the translation of Reports, and there is latitude on the part of the translators in choosing an expression that is both ‘adequate’ and ‘acceptable’ (Toury 1995).

Finally, the reviewed literature could be further divided between studies whose goals are ‘descriptive’ and those whose goals are ‘critical’ (Fairclough 1985, 1992). The majority of the TS on the Report fall into the former category. On the other hand, Zhu’s (2011a) and Wang’s (2023) approaches are manifestly critical, as are Wang’s (2020) and Song and Wang’s (2023), albeit less explicitly so. In these latter studies, the translation of the Report is seen as an endeavor to not only tell a story of China but also build an image for China.

However, although the Reports abound with metaphors, they are not and could not be entirely metaphorical, as is the case with discourses in general. In addition, there are other types of discursive phenomena that, although less eye-catching, are at least as prevalent and perhaps as ideology-laden as metaphors and that deserve systematic critical examination. One such type is deixis, whose usage in certain discourses is sometimes taken for granted. Within the CDA (but not the CDA-TS) scholarship, referencing through deixis has aroused much discussion (e.g., Fowler and Kress 1979; Fairclough and Wodak 1997; Hart 2011; see also Hart 2010, Chap. 3). The case study reported below, which is also critical in nature, is an attempt to explicate how ideological meanings may be encoded through referencing in the translation process, taking the 2024 Report and its English-translated version as an example and focusing on the patterned uses of the personal pronoun WE and its substitute, the proper noun CHINA, which are virtually everywhere to be seen.

Research design

Theoretical preliminaries

CBT sees as a key aspect of communication the building of networked ‘mental spaces’, which ‘are small conceptual packets constructed as we think and talk, for purposes of local understanding and action’ (Fauconnier and Turner 1996, Chap. 113). In a blending network, minimally four mental spaces are involved: two (or more) input spaces to be blended, which are distinct but connected in at least one communicatively relevant way; a generic space, which captures, usually at a more abstract level, the generic structure that the input spaces have in common; and a blended space, into which relevant elements together with their associated features and structures are projected. The blended space is also where ‘emergent structure’ comes into being as a result of conceptual blending operations such as composition, completion, and elaboration. Inner- or outer-space connections between elements that ‘show up again and again in compression under blending’ are labeled ‘vital relations’ (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p 92), of which a dozen or so types have been identified, e.g., identity, cause-effect, role, category, part-whole, uniqueness, time, space, etc. As has already been mentioned, CBT is a theory of online meaning construction and ‘is entirely resonant with the dialectical relation perceived by CDA between discourse and social structure’ (Hart 2008, p 98; emphasis here), i.e., that discourse is both shaped by and shapes, social structure (Fairclough and Wodak 1997, p 258).

Data

The Report is an official speech that is delivered by the Premier of the State Council every year at the second session of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Its main body can be roughly divided into two parts: (a) reviewing the government work in the past year and (b) laying out the overall requirements and policy orientation for economic and social development and the major tasks to be undertaken in the current year. Its translated versions, together with the original Report itself, serve as a window through which the rest of the world can obtain a better understanding of China and play an important role in the construction of China’s foreign discourse system. To illustrate, the 2024 ReportFootnote 2 is chosen not only because it was the latest one when the case study reported below was being conceived but also because 2023 was the first year in which Li Qiang, the incumbent Premier of the State Council, presided over the work of the agency and it is not unlikely that differences worthy of note might be spotted between the 2024 Report (i.e., the document in which government work of the year 2023 is reported) and the Reports that precede itFootnote 3.

Key concepts

The case study reported below is qualitative in nature, although statistics concerning the relevant pronouns and proper nouns are also manually calculated. Among these referential terms, as will be seen, a general division can be made between those that prompt an inside perspective and those that prompt an outside perspective. A working definition of the former in this study would be perspectives that issue from within the community picked out by a referential term and which serve inter alia to directly strengthen the bonds between individual members of this community. A working definition of the latter would be perspectives that issue from without the community picked out by a referential term and which serve inter alia to consolidate inner-group unity through (potential, not necessarily vicious) antagonism against alien entities or communities. An inside or outside perspective does not inhere in a referential item but is codetermined by the context or, from the perspective of CBT, is the product of blending operations. Within the former category, a further distinction can be made in terms of the scope of the collectivity identified, which may be either at a more local level, e.g., the collectivity of the government, or at a more global level, e.g., the collectivity of the whole country, but it is only a matter of relativity and degree. A similar continuum can be identified for the latter category, but as far as their ideological implications are concerned, it is of little relevance and will not be focused on here. The way a referential item is (sub)categorized and the ideological meanings implied can be modeled through the conceptual network activated.

The 2024 Report: a case study

One of the commonest and perhaps trickiest issues facing a translator and a topic widely discussed in the literature is the absence of subjects in Chinese political documents, including highly official ones such as the Reports, where the number of subject-less clauses is fairly high. In Mandarin Chinese, this is not only quite a commonplace in everyday speech but also perfectly legitimate as long as it does not hinder comprehension, whereas in Modern English, this is far less tolerable, at least on formal occasions, if the mood is indicative. One of the solutions, as mentioned incidentally in Li (2010, p 87), is maximizing conceptual parallelism by transforming the subject-less actives in the source into agentless passives in the target and leaving the same kind of imaginative work of identifying the subject to the target readers as is left to the source readers.

Another solution involves maximizing formal parallelism by preserving the voice and structure of the source, figuring out the missing concept, and manifesting it in the target, ideally at the subject position. In the original 2024 Report, an elliptical subject that is always traceable from the context by default is the Chinese first-person plural pronoun wǒ men, a word that ranks 9th on the key word list for the corpus of Reports from 1978 to 2010, referenced against LCMC (see Table 1 in Di and Yang (2010)). In the target text, the default choice would be, in principle, the addition of the English pronoun we if a subject has to be recovered and restored.

This is indeed the case, as usual. In Li and Hu’s (2017) study, the word that tops the keyword list for the Report corpus is none other than we (which ranks 2nd on the list for the SUA corpus). Taking a critical stance, Zhu (2011a) hypothesized about the factors having a bearing on the addition of this first-person plural pronoun as the subject (including also forms in the objective or genitive case), but unfortunately, he did not hint at any contextual clues that may (systematically) lend support to his hypotheses. According to him, both the exclusive and the inclusive senses seem probable here: generally, the former has a perlocutionary force of alienating the uninitiates, whereas the latter has a perlocutionary force of buttressing in-group ties. However, citing Fowler and Kress (1979, pp 202–203), he remarked that the inclusive usage is also potentially face-threatening: the people included by the pronoun are somewhat forced upon what is predicated of it (Zhu, 2011a, p 76). Moreover, citing Lakoff (1990, p 190), he noted that there is a third possibility, i.e., a ‘royal we’, which in this case refers to the Chinese Government alone and indicates an overtone of authority (ibid: 77).

Inside perspective

Global collectivity: WE and CHINA

Such referential ambiguity brings us to the core of the problem and hopefully, its solution: scrutinizing the context and ascertaining in a way as accurate as possible the scope of referents, rather than merely describing formal discrepancies with or worse, without statistics, or interpreting and explaining structural transformation or addition of an equivalent subject as if it happens in a vacuum, which amounts to nothing but an unfounded guess. This is necessary, since there are a comparable number of cases in which a subject is supplemented in the target clause that is not we but China (or its possessive form plus a head noun). This proper noun and the pronoun we are by no means contradictory. In fact, when what we refer to is the whole people of the country, the Government included, it has the same referential scope as the other word. There are even situations where, corresponding to subject-less clauses constituting a parallel structure within the same paragraph, different words are supplied for subjecthood in the target clauses:

-

(1)

a. 深入推進美麗中國建設。持續打好藍天、碧水、淨土保衛戰

shēnrù tuījìn měilì zhōngguó jiànshè. chíxù dǎhǎo lántiān, bìshuǐ, jìngtǔ bǎowèizhàn.

We advanced the Beautiful China Initiative and continued efforts to keep the skies blue, waters clear, and lands clean.

b. 加快實施重要生態系統保護和修復重大工程。

jiākuaì shíshī zhòngyào shēngtài xìtǒng bǎohù hé xiūfù zhòngdà gōngchéng.

We accelerated the implementation of major projects for protecting and restoring key ecosystems.

c. 積極參與和推動全球氣候治理。

jījí cānyǔ hé tuīdòng quánqiú qìhòu zhìlǐ.

China actively participated in and promoted global climate governance.

Of course, there are cases in which no transformation or addition is needed, and the target matches the source almost perfectly at both the conceptual and the formal level. In such cases, wǒ men is always translated directly as we in its proper form, but the source for China varies. Often, it is part of the English translation of either the name of international fairs or meetings held in the country (e.g., China International Import Expo, China Import and Export Fair, China International Fair for Trade in Services, China International Consumer Products Expo, etc.) or initiatives proposed and advocated by the Government (e.g., Beautiful/Healthy/Peaceful China).

Otherwise, its usage is less fixed, and the translator seems to have more discretion as to the choice of expressions that best fit the communicative purposes. In such cases, its source can be guó (jia) (country), zǔ guó (motherland) or zhōng huá rén mín gòng hé guó (the People’s Republic of China), which is usually abbreviated as zhōng guó (China) in the Reports. It can also be wǒ guó (our country), which is a blending of wǒ men and zhōng guó/guó jiā. This blend is interesting in itself since it is never translated in the 2024 Report as we—seven out of eight cases are translated as China(s), the other one being Chinese—which indicates that the semantics of this Chinese word is not a mere combination of that of its constituents, which are equal in weight but rather the result of a complex process of conceptual blending where (a) the frames activated by the two elements and the context make a difference; (b) one element is profiled and outweighs the other; and (c) most notably, there is emergent meaning that is nowhere to be found in the semantics of either of them (but see Ruiz de Mendoza (1998), Ruiz de Mendoza and Díez Velasco (2003) for a modified account).

However, as emphasized by Fauconnier and Turner (2002: 178), ‘[formal infinity] is a lesser infinity than the infinity of situations offered by the very rich physical mental world that we live in’. To make matters more complicated, it has to be added in relation to the present study, each of the clauses (selected from a potentially infinitive set) headed by a subject such as wǒ men or we can be used to mean more than one thing, since at the very least, the elements that comprise it can be used to mean more than one thing, i.e., they are themselves polysemous or ambiguous. As mentioned above, the English word we has at least three different personal usages, i.e., inclusive, exclusive, and royal, a fortiori, the impersonal usages explored in Kitagawa and Lehrer (1990). In fact, there is no definite boundary line between these usages, especially between the inclusive and the exclusive.

Xiaohua Tong (2014), a senior translator at the Compilation and Translation Bureau of the CPC Central Committee who participated in the translation work of the 2014 Report, discussed the issue of subject consciousness in the translation of the Report. According to him, translators of the Reports are not (only) who they are themselves as autonomous conscious beings but also the incarnation of the (individual or institutional) subjects at issue, which include first and foremost the author of the original Report (i.e., the Premier of the State Council), the Government that the Premier stands for, the CPC, the country and the Chinese people (Tong 2014, p 92). They have to bear all these subjects in mind throughout the translation process, and the translated text, like the original text, should be a truthful reflection of the volition of these ‘ghost’ subjects.

Thus, varying scopes of referents are (sometimes simultaneously) implied but can still be differentiated when wǒ men (and its equivalent we) is selected as the subject. However, what about situations in which China is chosen as the subject of the target clause for which we seem also (or more) eligible, i.e., where the subject is left implicit in the source clause but can be understood to be the whole country and its people? There must be reasons for the translator to choose one but not the other as the counterpart of the understood subject of the source clause. From the blending perspective, WE and CHINA prompt different mental spaces, and the context and the frames activated can provide a glimpse of the way mental spaces and blending networks are built online and, more importantly, to a critical study, of the ideological meanings that may emerge as a result. There is even a case in which the original subject is wǒ men whose intended referent is arguably the whole country with its people but which is then translated as China (square brackets indicating the place where omission is involved):

-

(2)

a. 我們這樣一個人口大國,

wǒmén zhèyàng yígè rénkǒu dàguó,

As China has a large population,

b. [我們]必須踐行好大農業觀、大食物觀,

[wǒmén] bìxū jiànxínghǎo dànóngyèguān, dàshíwùguān,

we must adopt an all-encompassing approach to agriculture and food

c. 始終把[我們的]飯碗牢牢端在[我們]自己手上。

shǐzhōng bǎ [wǒménde] fànwǎn láoláo duānzài [wǒmén] zìjǐ shǒushàng.

and ensure that China’s food supply remains firmly in our own hands.

In the target clause of (2a), China is selected as the subject, which can be seen as a blend of wǒ men and guó, the subject and part of the predicate of its source clause, respectively (a more literal translation of (2a) would be we are such a country as have a large population). This is echoed by the fact that wǒ guó is always translated in the English version of the Report as China(’s) rather than we, as aforementioned. The subject of the source clause of (2b) (and (2c)), which is the same as the subject of (2a) and is left elliptical, is, however, translated as we in the target. That China takes wǒ men as one of its inputs is further reflected in the addition in the target of (2c) of China’s and our.

This use of China(’s) in the target involves several rounds of integration. The first is a double-scope network: a bordered land is blended with the people who are born to have or have somehow legally acquired the right to live thereon and to govern their own lives collectively and independently from people living on other bordered lands. This metonymic blend of land/people is then given a name so that it can be differentiated from other similar blends of land/people, just as an individual is given a name so that it can be differentiated from other individuals. This gives rise to the notion of a country and its citizenry. The next is a simplex network: this categorical template is then blended with a specific case of it, which is the area that China covers and the people living there. This gives us the country of China with its citizenry. This blend is further integrated with the personal deixis we, which, depending on the context, can be used to signify varying scopes of inclusion and unity and defines a perspective that issues from inside the included community as opposed to one that issues from outside (see below). The result is a blend that consolidates the community that has the citizenship to live within this bordered area of China and alienates communities that live outside.

Local collectivity: WE

In addition to China(’s), we can also use it to signify a unity at the national level:

-

(3)

a. 深化兩岸融合發展,

shēnhuà liǎng’àn rónghé fāzhǎn,

By advancing integrated cross-Strait development,

b. [我們]增進兩岸同胞福祉,

[wǒmén] zēngjìn liǎng’àn tóngbāo fúzhǐ,

we will improve the well-being of Chinese people on both sides

c. [我們]同心共創民族復興偉業。

[wǒmén] tóngxīn gòngchuàng mínzú fùxīng wěiyè.

so that together, we can realize the glorious cause of national rejuvenation.

This sentence appears toward the end of this Report, where the subject of its component clauses is left implicit, as is always the case. In the target of (3c), a pronoun we is added, which—cued by together—is anaphoric and refers to the embedded nominal group of Chinese people on both sides in the preceding target clause. However, as is shown in the same target clause (i.e., (3b)), the overwhelming majority of the we used in the 2024 Report (423 out of 425 cases), either added or not, indicates a collectivity of a far lesser scope, a subset of the whole people of the country and which serves as a raison d’être of the speech, i.e., the Government. The fact that this we refers to the officials and workers of the Government and that the we that follows refers to the whole people of the country provides a reason why in the target of (3c), a finite adverbial clause is used in place of an equivalent infinitive clause (i.e., so as to …), the subject of which is conventionally elided if it is the same as the subject of the matrix clause that it is subordinate to (see, e.g., the target clause of (9) below).

This smaller collectivity is made explicit at the very beginning of the original Report and is understood as the default, a subject/agent locally invisible but whose existence is ambiently perceivable in other ways, which then gets surfaced in the translated text as we. In the source text, wǒ men appears 18 times, out of which 16 are translated as we (the other two being China and (let) us), which means that of all its appearances in the target text, 409 are added (i.e., 425–16 = 409). Moreover, extra information from the immediate context of this omnipresent ‘ghost’ subject guarantees that vagueness or ambiguity can be maximally and conveniently avoided. Such information can be accessed directly either from a preceding clause, which provides an antecedent for the we in the next clause to refer back to:

-

(4)

a. 廣大幹部要……

guǎngdà gànbù yào …

All our officials must act …

b. [我們]提振幹事創業的精氣神……

[wǒmén] tízhèn gànshì chuàngyè de jīngqìshén …

We must be dedicated and enterprising …

or from the same clause:

-

(5)

[我們]各級政府要大力支持……

[wǒmén] gèjí zhèngfǔ yào dàlì zhīchí …

We in governments at all levels will provide …

More frequently, the identity of the smaller collectivity can be deduced using the method of exclusion, i.e., the set of referents picked out by the nominal groups in the predicate should be exclusive of, or at least should not be exactly the same as, i.e., the set picked out by we. This other set of referents is always (translated as) the public or people:

-

(6)

[我們][向群眾]精准做好政策宣傳解讀……

[wǒmén][xiàng qúnzhòng] jīngzhǔn zuòhǎo zhèngcè xuānchuán jiědú …

We should communicate policies to the public in a well-targeted way to …

-

(7)

[我們]豐富人民群眾精神文化生活。

[wǒmén] fēngfù rénmín qúnzhòng jīngshén wénhuà shēnghuó.

We will enrich people’s intellectual and cultural lives.

or more specifically, our people:

-

(8)

我代表國務院, 向全國各族人民……表示衷心感謝!

wǒ dàibiǎo guówùyùan, xiàng quánguó gèzú rénmín … biǎoshì zhōngxīn gǎnxiè!

On behalf of the State Council, I express sincere gratitude to all our people, and …

-

(9)

我們要……厚植人民幸福之本……

wǒmén yào … hòuzhí rénmín xìngfú zhī běn …

We will … so as to lay a solid foundation for enhancing the well-being of our people …

-

(10)

[我們]不斷增強人民群眾的獲得感、幸福感、安全感。

[wǒmén] búduàn zēngqiáng rénmín de huòdégǎn, xìngfúgǎn, ānquángǎn.

By doing so, we will give our people a growing sense of fulfillment, happiness, and security.

-

(11)

[我們]深化全民閱讀活動

[wǒmén] shēnhuà quánmín yuèdú huódòng.

We will … do more to foster a love of reading among our people

From the blending perspective, this nominal group is derived by integrating a head noun (i.e., people) with a deictic (i.e., our). In one input space is a community identified by the deictic, and in the other, another community is referred to by the head. There is some kind of vital relation between these two communities. A deictic like our prototypically signifies a possessive relationship between two entities, i.e., the possessor and the possessed. However, this would mean that in this case, one group of people (i.e., Chinese people) is ‘possessed’ by another, smaller group of people (i.e., collectively known as the Chinese Government), which is a hallmark of slavery or feudal society and which self-evidently runs counter to the political system of modern China. Such an interpretation would also fail to capture the fact that the smaller community shares a defining characteristic with the other community, i.e., nationality: officials and workers in the Government are themselves Chinese.

Therefore, the vital relation between these two elements is first and foremost one of part-whole. The way in which the smaller group of people is selected as a noteworthy part of the whole is left unsaid, and this relation is compressed into a property (i.e., our) of the larger group. Arguably, there is also a causal link between them, although in a fairly general sense. The smaller group of people is rigorously selected in accordance with the spirit of the Constitution of China, and the Government that they constitute is intended as one of the people and for the people. These are people deemed morally decent, intellectually competent, and faithfully persistent enough to implement the decisions and plans of the Party Central Committee and improve people’s wellbeing across the board. As a result, these vital relations prompt an inside perspective that aligns the government with the people, as opposed to an outside perspective prompted by a vital relation of possession, which indicates a breach or inequality between the two parties. This alignment of viewpoints also introduces an emotional element since spatial distance is always indicative of social relationships (Hall 1966).

Notably, as shown in the cases above, the use of our in the target clauses is intentional (although not necessarily conscious) on the part of the translator, since there is no (explicit) counterpart in the sources. The additional meanings that may emerge from the blending of our and people are for the most part available to the majority of the source readers and can thus be left safely unexpressed, which is perhaps one of the reasons why there is no e.g., wǒ men de (adjectival form of wǒ men) in the original text. However, since the translated versions of the Report play such a key role in keeping the rest of the world abreast of the status quo of China and building an image for both the Government and the country, it can be argued that ideologically speaking, addition of our would probabilistically prompt the target readers to consciously unpack the blended space to retrace the way the cross-space vital relations are compressed. Admittedly, the use of a deictic like our alone would hardly be sufficient to help the target readers reconstruct in the intended way the kinds of relations that the Government bears to the other Chinese people. However, it provides at least an opportunity or motivation for them to search for more information from the rest of the Report and/or from other similar documents issued by the Government.

A more specific strategic objective of the translated (and to a lesser extent, the original) version of the Report seems then to highlight the execution and/or achievements of the Government and, by extension, of the country of which it is a part, which is perhaps hardly surprising. However, the way in which this is accomplished is manifold and sometimes even elusive.

At the lexical level, this can be seen directly from the bundles of words regularly modified by our in the English version of the Report (see Table 1). In this version, this deictic appears 52 times, all intentionally added. In contrast, for each and every one of the head nouns, it modifies a counterpart that can be found in the original text. These words can be roughly divided into five semantic groups. In one word, that together with the full active clauses headed by we elsewhere in the Report, tells a grand story of which the Government is the protagonist, who undertakes methodically and persistently a series of demanding tasks. There is also a group that highlights the end results of such undertakings, i.e., the feats that the Government has achieved. These instantiate what Fauconnier and Turner (2002, p 114) labeled ‘syncopation’, where the preceding points along the time (and causal) line at which a minor task is performed are conceptually backgrounded or suppressed, although the point to which a (minor) task is indexical is itself usually also a radical compression over a complicated chain of actions or events.

At the clausal level, the Government, with its officials and workers, is always granted a metafunctionally conspicuous status by being made simultaneously the Theme, Subject, and Actor of a clause (Halliday and Matthiesen 2014). Thematically, it is the point from which the grand story starts to unfold; interpersonally, it is the party on which the truthfulness of the story is based; ideationally, it is the agent by which the story is actually carried forward. It should be noted that restoring the elided subject in the source to its usual place in the target is neither mechanical nor for structure’s sake only. Although in the majority of the cases, little choice is left to the translator, to fill the subject position of the target clause with a word closest in meaning to the elliptical subject in the source, sometimes what is actually going on is more than a mere compulsory addition. There are cases in which a source clause whose voice is ‘middle’ is translated into a clause whose voice is ‘effective’ (ibid), where either the main verb, which is ergative, is recycled:

-

(12)

一年來, 中國特色大國外交全面推進。

yīniánlái, zhōngguó tèsè dàguó wàijiāo quánmiàn tuījìn.

In 2023, we advanced major-country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics on all fronts.

-

(13)

社會大局保持穩定

shèhuì dàjú bǎochí wěndìng

(we) maintained overall social stability

or a more complex construction with a non-ergative main verb is used:

-

(14)

新冠疫情防控實現平穩轉段

xīnguān yìqíng fángkòng shíxiàn píngwěn zhuǎnduàn

We secured a smooth transition in epidemic response following a major, decisive victory in the fight against COVID-19.

-

(15)

高品質發展紮實推進

gāopǐnzhì fāzhǎn zhāshí tuījìn

we made steady progress in pursuing high-quality development

These are different from the cases analyzed in Mandelblit (1997). Here, the translator has more than one grammatical construction at their disposal. For (12) and (13), a more faithful translation would be one in which not only the ergative verb but also the voice is retained (e.g., major-country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics on all fronts advanced). Formally, voice change requires supplementation of an Agent/Subject. Conceptually, meanwhile, there is a change in event type from happening to doing. In (14) and (15), the change is even more radical and less cost-efficient, where the ergative verb in the source (i.e., tuījìn) is turned into a noun that is homonymous with its verb form (i.e., transition and progress) and substituted by a ‘dummy’ verb (i.e., made) in the target. Here, such voice change-induced addition of subjects is hardly done (purely) in the interest of information packaging since the Theme of the clauses in their vicinity varies. It prompts the target readers to map an additional nominal group onto the Agent role of the target event, which is nowhere to be found in the source. This has the ideological effect of crediting the ‘transition’ or ‘progress’ achieved to an extrinsic participant, which is the Government identified by us, rather than to the original Medium itself (which becomes embedded in the nominal group headed by progress in the target clause, i.e., high-quality development).

It can be seen that the subject wǒ men in the source can be translated as both WE and CHINA in the target, and both can be used to pick out the same set of referents, i.e., the whole country (with its people). A natural question to ask then is the following: if the subject is left unsaid in the source clause and there exists no evidence to the contrary of a ‘country’ interpretation—as a matter of fact, there is often compelling evidence of such an interpretation—why does the translator choose one but not the other? Worse still, there is even a third possibility: our country(’s), a blend that takes WE and CHINA as its inputs (see Table 1).

Outside perspective: CHINA

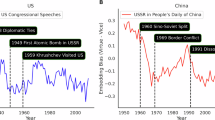

In the English version, China and China’s appear 39 and 23 times each, respectively, and the number of cases in which they are optionally added is 12 and 13, respectively. As shown in (2a), China can be used to signify an inside perspective that integrates all Chinese citizens, including Government officials and workers, into an inseparable whole. However, there are cases suggesting that another perspective is also possible:

-

(16)

[我國]國內生產總值超過126萬億元, 增長5.2%, [我國]增速居世界主要經濟體前列。

[wǒguó] guónèi shēngchǎn zǒngzhí chāoguò 126 wànyì yuán, zēngzhǎng 5.2%, [wǒguó] zēngsù jū shìjiè zhǔyào jīngjìtǐ qiánliè.

China’s gross domestic product (GDP) surpassed 126 trillion yuan, an increase of 5.2 percent, ranking China among the fastest-growing major economies in the world.

-

(17)

[我國]新能源汽車產銷量占全球比重超過60%。

[wǒguó] xīnnéngyuán qìchē chǎnxiāoliàng zhàn quánqiú bǐzhòng chāoguò 60%.

China accounted for over 60 percent of global electric vehicle output and sales.

-

(18)

[我國]全年新增裝機超過全球一半

[wǒguó] quánnián xīnzēng zhuāngjī chāoguò quánqiú yíbàn.

China accounted for over half of the newly installed renewable energy capacity worldwide.

-

(19)

[我國]成功舉辦中國一中亞峰會、第三屆“一帶一路”國際合作高峰論壇等重大主場外交活動。

[wǒguó] chénggōng jǔbàn zhōngguó-zhōngyà fēnghuì, dìsānjiè “yīdàiyīlù” guójì hézuò gāofēng lùntán děng zhòngdà zhǔchǎng wàijiāo huódòng

China hosted a number of major diplomatic events, including the China-Central Asia Summit and the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation.

It is not difficult to see from these cases that China(’s) is here imbued with a semantic prosody of international competition (see (16), (17) and (18)) or cooperation (see (19)). This prompts an integration network different from the one with a resultant inside perspective. Here, in one input space is the country of China together with its citizenry, and in the other is the frame COMPETITION or COOPERATION (between China and other countries or regions), with a cross-space mapping of identity (i.e., China). The frame COMPETITION activates the concept of ranking (see (16)) or market share (see (17) and (18)), whereas the frame COOPERATION activates the concepts of diplomacy and meetings (see (19)). Whichever the case, in the blend, there emerges a perspective that issues from outside the community identified by China(’s). This has a similar ideological effect of further strengthening the ties among the community members while at the same time urging the target readers to develop more intuitive knowledge of China via comparison with either their own countries or countries with which they are more familiar. Such an outside perspective is also evident in cases where China(’s) is a straightforward translation of zhōng guó or wǒ guó.

-

(20)

the global market share of China’s exports remained stable

-

(21)

the external environment exerted a more adverse impact on China’s development

-

(22)

China’s external environment has become more complex, severe, and uncertain.

-

(23)

A comprehensive analysis and assessment shows that China’s development environment this year will continue to feature both strategic opportunities and challenges, with favorable conditions outweighing unfavorable ones.

These cases prompt a slightly different network. In one space is still China, while in the other is the frame DEVELOPMENT, which contains, inter alia, an entity that develops and the external environmental conditions of such development, where there are both competitions and collaborations. From (21) to (23), it can be seen that the external environment that China finds itself in seems to have a more pejorative semantic prosody. In both the original and the translated text, this has the ideological effect of not only personifying China (i.e., the STATE IS PERSON metaphor (Lakoff 1991)) but also building traits such as benevolence and perseverance into the national image of China, which is not only ready to help and share but also has the courage to face up to any challenges.

This contrasts with the inside perspective argued above, but they have the common ideological goal of aligning the Government with the whole country and its people. After all, the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation cannot be truly realized with anyone left behind. The Report makes it clear that China has been making steady progress toward modernization. From an outside perspective, it acknowledges the indispensable role played by every Chinese citizen, not only those who work in the central or local government, and from an inside perspective, it calls on everyone to carry on their work since the great cause has yet to be completed.

Conclusion

As noted by Tian (2017b, p 64), when we see translation as a component of social practice, what we normally focus on is not (only) whether the translated text is expressive or elegant (enough) in itself or faithful in relation to the original text but also in what ways and to what extent the whole translation process (i.e., production, distribution and consumption of the translated text) is constitutive to social reality. A corollary of integrating such a critical perspective into TS is that no natural priority is given to formal discrepancy between the original and the translated text, and somewhat counterintuitively, however, attention is given to (patterns of) cases where core ideological meanings can be traced regardless of whether formal equivalence is achieved. In addition, the cognitive linguistic theory of conceptual blending provides powerful theoretical machinery for us to simulate the way a translated text is produced and/or consumed ‘on the fly’. This lays a firm foundation for critical TS to be carried out.

The Report serves as a gateway through which the rest of the world can catch a glimpse of and get in touch with, China. The fact that each year, NPCs and CPPCCs are globally reported in newspapers and broadcast on television and the fact that the Report is openly accessible from the internet, make the potential ideological effects discussed in this paper all the more influential, which can be traced from the blending networks repetitively activated by patterns of language use in both the original Report and its translated versions. It is illustrated in this paper that such simple words as the pronoun we and the proper noun China in the English version of the 2024 Report are expressions that seem no less ideology-laden (than, e.g., metaphorical ones, discussed elsewhere) from a critical conceptual blending perspective. It is also shown that being critical requires that not only words (either function or content) and syntactic structures, but also context be taken into close consideration in (critical) TS.

It has been found that in the target text, WE identifies varying scopes of referents. It can refer to either the Government or the whole country, with the people whom the Government is believed to stand for in one way or another. Arguably, the former has an ideological effect of highlighting the essential role played by the Government in pursuing the lofty goal of national rejuvenation, while the latter has one of cementing the connections between the Government and the citizenry. On the other hand, CHINA, as a candidate substitute for WE, whether intentionally added by the translator or not, can similarly prompt varying blending networks. It can trigger either an inside or outside perspective while aligning the Government with the people. In the former case, the way they are aligned is by highlighting the role played by the citizenry in pursuing the goal, while in the latter case, it is done by calling on the citizenry to continue to follow suit and carry on their work to realize the goal, better earlier.

Through such systematic modeling of the ideological meanings of these referential items, this study further demonstrates the fertility of the union of CBT and CDA in TS. More specifically, it contributes to a more refined way of understanding and analyzing referential items in context, i.e., in relation to their scope and their (inside vs outside) perspective. This also has implications for a fuller interpretation of the (ideological) meanings of official political documents such as the Report and its translated versions. Within such a type of discourse, further studies may take a closer look at discursive phenomena other than metaphor and referencing, either in isolation or in interaction, such as metonymy and ‘metaphtonymy’ (Goossens 1990). Alternatively, as has already been noted, comparative studies may be carried out between Reports and their translated versions from different years. A more multimodality-oriented and perhaps more ambitious program may choose to examine how semiotic modes other than the verbal mode may contribute to our understanding of the Reports, e.g., accompaniment gestures made during the speech (see, e.g., Hart and Winter 2022; Casasanto and Jasmin 2010).

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Notes

MTS, in light of Wang (2023), can be defined as research that focuses on how metaphors in the source text are translated.

The 2024 Report and its English translated version are publicly and freely available at the official website of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China:

https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/2024/issue_11246/202403/content_6941846.html.

https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202403/13/content_WS65f0dfccc6d0868f4e8e5079.html.

Systematic comparison with regard to either metaphorization or referencing or else is, unfortunately, due to space limitations beyond the scope of this paper, for which it serves only as a first step.

References

Aixelá JF (1996) Culture-specific items in translation. Multilingual Matters, Clevedon

Baker M, Francis G, Tognini-Bonelli E (1993) Text and technology: in honor of John Sinclair. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Breeze R (2013) Critical discourse analysis and its critics. Pragmatics 21(4):493–525

Casasanto D, Jasmin K (2010) Good and bad in the hands of politicians: spontaneous gestures during positive and negative speech. PLoS ONE 5(7):e11805

Chiapello E, Fairclough N (2002) Understanding the new management ideology: a transdisciplinary contribution from critical discourse analysis and new sociology of Capitalism. Discourse Soc 13(2):185–208

Di Y, Yang Z (2010) A corpus-based analysis of central key words in Chinese Government Work Reports. Foreign Lang Res 6:69–72

Fairclough N (1985) Critical and descriptive goals in discourse analysis. J Pragmat 9(6):739–762

Fairclough N (1992) Discourse and social change. Polity Press, Cambridge and Oxford

Fairclough N (1993) Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: the universities. Discourse Soc 4(2):133–168

Fairclough N (2005) Critical discourse analysis in transdisciplinary research. In: Wodak R, Chilton P (eds) A new agenda in (critical) discourse analysis: theory, methodology and interdisciplinarity. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 53–70

Fairclough N, Wodak R (1997) Critical discourse analysis. In: van Dijk TA (ed) Discourse as social interaction. Sage, London, pp 258–284

Fauconnier G, Turner M (1996) Blending as a central process of grammar. In: Goldberg AE (ed) Conceptual structure, discourse and language. Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI) Publications, Stanford, pp 113–130

Fauconnier G, Turner M (2002) The way we think: conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities. Basic Books, New York

Fowler R, Kress G (1979) Critical linguistics. In: Fowler R et al. (eds) Language and control. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, pp 185–213

Goossens L (1990) Metaphtonymy: the interaction of metaphor and metonymy in expressions for linguistic action. Cogn Linguist 1(3):323–340

Hall ET (1966) The Hidden Dimension. Doubleday, Garden City

Halliday MAK (2000) An introduction to functional grammar. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, Beijing

Halliday MAK, Matthiesen CMIM (2014) Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. Routledge, London

Hart C (2008) Critical discourse analysis and metaphor: toward a theoretical framework. Crit Discourse Stud 5(2):91–106

Hart C (2014b) Discourse, grammar and ideology: functional and cognitive perspectives. Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Hart C, Winter B (2022) Gesture and legitimation in the anti-immigration discourse of Nigel Farage. Discourse Soc 33(1):34–55

Hart C (2010) Critical discourse analysis and cognitive science: new perspectives on immigration discourse. Springer, Berlin

Hart C (2011) Moving beyond metaphor in the cognitive linguistic approach to CDA. In: Hart C (ed) Critical discourse studies in context and cognition. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 171–192

Hart C (2014a) Constructing contexts through grammar: cognitive models and conceptualization in British newspaper reports of political protests. In: Flowerdew J (ed) Discourse in context: contemporary applied linguistics, vol 3. Continuum, London, pp 159–184

Hu K, Tao Q (2012) Syntactic operational norms of press conference interpreting (Chinese–English). Foreign Lang Teach Res 44(5):738–750+801

Hu F, Jing B, Li X (2012) Application of cohesion theory in the translation of political literature: a case study of the 2010 Government Work Report. Foreign Lang Res 2:89–91

Kitagawa C, Lehrer A (1990) Impersonal usages of personal pronouns. J Pragmat 14:739–759

Lakoff G (1991) Metaphor and war: the metaphor system used to justify war in the Gulf. Peace Res 23(2/3):25–32

Lakoff G, Johnson M (1980) Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lakoff R (1990) Talking power: the politics of language. Basic Books, New York

Li H (2010) The English translating strategies of political essays: a case study of Report on the Work of the Government in 2010. Foreign Lang Lit 26(5):85–88

Li X, Hu K (2017) Keywords and their collocations in the English translations of Chinese Government Work Reports. Foreign Lang China 14(6):81–89

Lu Z, Wang D (2016) Flexible wording in the translation of the 2016 Report on the Work of the Government. Shanghai J Transl 4: 21–27+93

Mandelblit N (1997) Grammatical blending: creative and schematic aspects in sentence processing and translation. University of California, San Diego, California

Martin R, White P (2005) The language of evaluation: appraisal in English. Continuum, London

O’Halloran K (2003) Critical discourse analysis and language cognition. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Pan F, Sheng D (2021) Norms and norm-taking in interpreting for Chinese government press conferences: a case study of hedges. Foreign language learning theory and practice. Springer, pp 115–125

Reisigl M, Wodak R (2016) The discourse-historical approach. In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods of critical discourse studies. Sage, London, pp 23–61

Ruiz de Mendoza FJ (1998) On the nature of blending as a cognitive phenomenon. J Pragmat 30:259–274

Ruiz de Mendoza FJ, Díez Velasco OI (2003) Patterns of conceptual interaction. In: Dirven R, Pörings R (eds) Metaphor and metonymy in comparison and contrast. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, pp 489–532

Si B, Gao S (2019) Distribution of the graduation resources in Chinese publicity texts and their English translation: taking the original text of the 2019 Report on the Work of the Government and its translated version as an example. Shanghai J Transl 5:14–20

Song C, Wang K (2023) A diachronic study on the de-foreignization trend in the translation of political documents. Foreign Lang Educ 44(6):63–70

Tian H (2017a) Discourse-studies’ paradigm for the English translation of CPC central committee literature: a transdisciplinary perspective. J Tianjin Foreign Stud Univ 24(5):1–7+80

Tian H (2017b) Translation as social practice: CDA-based theoretical reflections and methodological exploration. Foreign Lang Res 34(3):60–64+71+112

Tian X (2022) A corpus-based study on the operational norms in the English translation of modal verbs in Report on the Work of the Government. Shanghai J Transl 5:20–25

Tong X (2014) Subject consciousness in translation: insights gained from translating the 2014 Work of the Government. Chin Transl J 35(4):92–97

Toury G (1995) Descriptive translation studies and beyond. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

van Leeuwen T (2005) Three models of interdisciplinarity. In: Wodak R, Chilton P (eds) A new agenda in (critical) discourse analysis: theory, methodology and interdisciplinarity. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 3–18

Wang D (2020) A Study on the cultural correspondence and strategies adopted in the English translation of words with Chinese characteristics in the Report on the Work of the Government. Acad Res 12: 34–40

Wang Q (2023) Exploring a transdisciplinary approach to metaphor translation studies from the perspective of critical metaphor analysis. Discourse Stud forum 2:131–147

Widdowson HG (2004) Text, context, and pretext: critical issues in discourse analysis. Blackwell, West Sussex

Wodak R (2006) Mediation between discourse and society: assessing cognitive approaches in CDA. Discourse Stud 8(1):179–190

Wu G (2010) Redundancies in the English translated version of the 2010 Report on the Work of the Government: analysis and suggestions. Chin Transl J 31(6):64–68

Wu G (2014) A corpus-based analysis of the textual features of the English translated version of Report on the Work of the Government. J Xi’ Int Stud Univ 22(4):118–121

Wu G, Zhao W (2013) Readership survey on the acceptability of English translated versions of Chinese political documents: taking the 2011 Report on the Work of the Government as an example. Foreign Lang Res 2:84–88

Zhu X (2011b) A corpus-based study on translation universals in the translation of Chinese political texts. J PLA Univ Foreign Lang 34(3):73–77

Zhu X (2011a) A corpus-based critical discourse analysis of the English translation of report on the work of the government (1): first person plural pronouns. Foreign Lang Res 2:73–78

Acknowledgements

There was no funding received for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This paper is a single-author contribution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q. Extending the integrated perspective of CDA and CBT beyond metaphors in translation studies: taking the English translation of the 2024 Report on the Work of the Government as an example. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1836 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06119-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06119-6