Abstract

Research on the determinants of students’ success in specialised STEM schools has devoted considerable attention to psychological factors. Using a path analytic model, this study investigated whether a growth math mindset, referring to the theory that math ability can be improved incrementally, is indirectly associated with academically gifted students’ math achievement and intrinsic motivation to pursue learning goals. This study also examined the associations of career interests with intrinsic motivation and math achievement in the path model. Data were collected from 132 9th–12th graders attending a full-day STEM high school with a selective student admissions process. The findings suggest that the perception of ability as incremental contributes to adaptive achievement behaviours, such as accepting challenges. Moreover, intrinsic motivation, a critical factor in maintaining interest in STEM careers, is indirectly associated with a growth math mindset. These findings indicate that a growth mindset meaning system, an incremental theory of intelligence and learning goals, in mathematics and math-oriented intrinsic motivation are related to maintaining interest in STEM careers among academically gifted students within challenging academic situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Policymakers and educators in the United States have viewed developing professionals in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields as critical for economic growth and global competitiveness (National Science Board, 2014; 2024). Concerns about the lack of trained professionals in STEM disciplines (Holdren and Lander, 2012) have fueled the establishment of STEM high schools designed to support the development of future scientists and engineers (Thomas and Williams, 2010). Some specialised STEM schools serve academically gifted students who excel in mathematics and science and prepare them for pursuing careers in STEM (Subotnik et al., 2009). These gifted students gain challenging coursework experiences while advancing to high levels in their talent domains (Subotnik et al., 2012).

However, some academically gifted students do not benefit from the academic challenges; instead, they underachieve. This phenomenon has long been a concern in the study of education for gifted students (e.g., Moon et al., 2002; Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2020). Students in STEM schools face challenging course materials, competition from similarly gifted peers (e.g., Seaton et al., 2010), and pressure to achieve (Tofel-Grehl and Callahan, 2014). These factors may cause some students to lose interest in STEM fields and academic success. Indeed, survey responses from students at a specialised STEM school revealed that many perceived their school environment as ‘difficult or stressful’ and ‘challenging, rigorous and competitive’ (Challenge Success: Student Survey Executive Summary, 2019). Such stressful and competitive environments may discourage some students from choosing STEM career pathways.

Interest in STEM areas (Steenbergen-Hu and Olszewski-Kubilius, 2017) and mathematical ability (Lubinski and Benbow, 2006) are critical factors in determining whether gifted students will persevere and succeed. Accordingly, the present study explored psychological factors contributing to academically gifted students’ success. We focused on the factors associated with their sustained interest and academic success—particularly in mathematics—in pursuing STEM careers within specialised STEM schools.

Psychological factors affecting STEM career interest

Mindsets of intelligence

Intelligence mindsets refer to implicit theories of ability (Dweck and Yeager, 2019). Research on implicit theories of ability has introduced a key psychological variable that may mediate the challenging circumstance of specialised STEM schools for the academically gifted. Based on Dweck’s (Dweck and Leggett, 1988; Dweck and Yeager, 2019) social–cognitive theory of motivation, researchers have identified implicit theories of intellectual ability as significantly related to improved academic achievement and the development of student abilities when faced with challenges. Dweck’s motivation model (Dweck and Leggett, 1988) posited two implicit theories of intelligence: incremental and entity. Children holding an incremental theory of intelligence consider intelligence to be malleable and changeable through effort, strategies, help from others, practices, and perseverance over time (Dweck and Leggett, 1988; Blackwell et al., 2007), while those with an entity theory of intelligence view intelligence as a fixed entity. As research on implicit theories of intelligence progressed, the original terminology (i.e., incremental vs. entity theories) was revised to the more user-friendly terms of growth and fixed mindsets (Dweck, 2006). Moreover, Dweck and her colleagues found that the perceptions of intelligence unite goals, behaviours, and subsequent achievement in challenging academic situations (e.g., Dweck and Leggett, 1988; Molden and Dweck, 2006).

More specifically, early studies of implicit theories of intelligence revealed a mechanism through which the theories of intelligence are related to improved academic achievement and the effectiveness of an incremental theory intervention. For instance, Blackwell et al. (2007) demonstrated the positive relationship between a growth mindset and improved math achievement via mediators such as learning goals and positive strategies and the positive effect of teaching a growth mindset on grades. Aronson et al. (2002) also showed that an incremental theory intervention positively affected academic achievement. Based on early findings relating to mindsets, researchers (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2007) concluded that when students on either side of the mindsets continuum are equal in intellectual ability, they will adopt either learning goals or performance goals, based on their accepted mindset. Consequently, incremental theorists who pursue opportunities to learn something new are more likely to thrive in the face of academic challenges than entity theorists, who seek validation of their abilities, even when they are equal in intellectual ability (Blackwell et al., 2007). These findings were consistently supported by evidence of an association between mindset and performance in students facing academic challenges (e.g., Burnette et al., 2013; Kanopka et al., 2020).

Mindset effects

Several scholars have demonstrated the positive effects of mindset intervention online and to scale (Paunesku et al., 2015; Yeager et al., 2016), including in two preregistered replications (Yeager, Hanselman, et al., 2019; Yeager, et al., 2016). While the interventions’ effects on academic performance are modest, online and scalable interventions changed mindsets and academic outcomes under specific conditions for typically low-achieving students. For higher-achieving students, growth mindset interventions were useful in supporting positive outcomes, such as willingness to take on challenges (Yeager, et al., 2016) or to take advanced math courses (Yeager, Hanselman, et al., 2019).

With increasing interest in mindset among researchers and policymakers, questions about the replicability of growth mindset effects have also been raised (e.g., Burgoyne et al., 2020; Li and Bates, 2019; Sisk et al., 2018). Li and Bates (2019) reported no significant relationship between mindset and student grades or intellectual performance, and Burgoyne et al. (2020) observed only weak or no associations between mindset and several meaning-system variables (performance goals, learning goals, and attributions). Sisk et al. (2018) conducted two meta-analyses and concluded that the overall effects of mindset on academic achievement and the effectiveness of mindset interventions were weak.

The most recent meta-analyses (Burnette et al., 2023; Macnamara and Burgoyne, 2023) have reported contradictory findings on the effectiveness of growth mindset interventions. Macnamara and Burgoyne (2023) reported a small overall effect of a growth mindset intervention on academic outcomes. However, Burnette et al. (2023) reported positive effects of growth mindset interventions on academic outcomes, mental health, and social functioning by focusing on subsamples and the implementation fidelity of the interventions. In addition, Tipton et al. (2023) provided supporting evidence for a statistically significant effect of growth mindset in focal (at-risk) groups (Burnette et al., 2023) and concluded that a heterogeneity-attuned method (best practice in meta-analysis focusing on the extent to which effects vary across participant groups, contexts, etc.), such as the meta-analysis conducted by Burnette et al. (2023), is important for advancing theory.

In response to the issues on growth mindset effects, Yeager and Dweck (2020) elucidated the key points of mindset theory, highlighting the issue of cultural context in Li and Bates’ (2019) study and the achievement goal measures (normative-focused goals) used by Burgoyne et al. (2020) as opposed to the appearance/ability goals used in Dweck’s research (c.f., Grant and Dweck, 2003). Yeager and Dweck (2020) reported generalisable associations between mindset and achievement based on large-scale studies and emphasised the importance of educational context, such as challenging academic situations, and the critical role that achievement goals (appearance/ability goals) play in the mindset meaning system to replicate mindset effects. Furthermore, Yan and Schuetze (2023) recommended that researchers consider multiple outcomes affected by growth mindset theory and develop a better way of measuring mindsets by specifying the meaning of the term ‘intelligence’.

Mindset meaning systems

Overall, in Dweck’s mindset meaning systems (Yeager and Dweck, 2020), the growth mindset is the origin of adaptive achievement behaviours, such as accepting challenges, while the fixed mindset results in maladaptive achievement behaviours, such as the avoidance of challenges in demanding academic situations. Yeager and Dweck (2020) explained that different ‘meaning systems’ lead to different achievement behaviours by fostering different interpretations of effort. More specifically, in the face of academic challenges, an incremental meaning system teaches students to pursue learning goals, which guides them to learn something new from tasks and improve their performance by increasing their effort, using different strategies and trying to find help from others. By contrast, a fixed meaning system induces students to pursue performance goals. They may avoid any activity that could indicate a lowered level of ability by deciding not to exert effort, consequently missing out on opportunities to boost their academic achievement. In turn, effort-reductive strategies may lead to low achievement. Hence, in the next section, we discuss achievement goals as a psychological factor that affects STEM career interests under challenging circumstances.

Achievement goals

In Dweck and Leggett (1988); Yeager and Dweck (2020) motivation model, achievement goals are one of the core components used to explain the learning process. Dweck and Leggett (1988) clarified the dichotomous framework, distinguishing between learning and performance goals to explain how goal orientations mediate the relationship between implicit theories of intelligence and academic achievement. According to this dichotomous framework, individuals who pursue learning goals are focused on improving their skills, mastering materials, and learning through extensive effort. In addition, they tend to enjoy learning (Dweck and Leggett, 1988; Kover and Worrell, 2010). By contrast, those who pursue performance goals focus on maximising favourable evaluations and minimising negative evaluations of their competence. Consequently, they are less likely to enjoy learning and tend to prioritise avoiding failure or acquiring good grades (Dweck and Leggett, 1988; Kover and Worrell, 2010). Ultimately, they may eschew challenging tasks in the interest of positive competency evaluations.

These contrasting responses to challenging tasks and setbacks yield different outcomes. For example, those who pursue learning goals tend to be interested in their courses, whereas those pursuing performance goals do not (Harackiewicz et al., 2000). Learning goal pursuers engage in deeper, more self-regulated learning strategies, have higher intrinsic motivation, and perform better, particularly when facing challenges or setbacks (e.g., Harackiewicz et al., 2000; Lu et al., 2021; Taing et al., 2013). Performance goal pursuers are more likely to achieve good academic performance but lack interest (Harackiewicz et al., 2000; Harackiewicz et al., 2008).

Research findings pertaining to the association between performance goals and interest suggest that the characteristics of entity theorists are the opposite of the interest-and challenge-seeking characteristics of intrinsically motivated people (e.g., Hunt, 1965; Lepper et al., 2005). Indeed, studies have shown that entity views adversely affect intrinsic motivation (Cury et al., 2006, Study 2; Haimovitz et al., 2011). In other words, in challenging academic situations, students who hold fixed mindsets and pursue performance goals are unlikely to maintain interest or intrinsic motivation. As such, a growth mindset meaning system may play a significant role in helping them sustain their interest or intrinsic motivation.

Interest in STEM (Steenbergen-Hu and Olszewski-Kubilius, 2017) is a significant factor in gifted students’ decisions to pursue STEM career pathways. According to Hidi and Renninger (2006), interest may be regarded as developmental, with situational interest in the initial stage and individual interest in the latter stage, which is similar to intrinsic motivation. Thus, we investigated this factor more deeply to understand why some students maintain an interest in challenging academic situations while others do not. In the next section, we discuss interest and intrinsic motivation and why we chose to investigate intrinsic motivation rather than interest as a psychological factor affecting interest in STEM careers in the hypothesised model.

Interest and intrinsic motivation

Previous studies have used interest and intrinsic motivation as similar concepts. As a motivational variable, interest is the psychological state of engaging or the predisposition to re-engage with particular classes of objects, events, or ideas over time (Hidi and Renninger, 2006). According to Hidi and Renninger (2006), there are two types of interest: situational and individual. Situational interest is a temporary state triggered by a situation, task, or object, whereas individual interest is a relatively stable state of interest in particular subject areas or objects. Situational interest may disappear when the situations, tasks, objects, or others (e.g., teachers) that trigger it disappear. In contrast, individual interest is typically self-generated by ‘curiosity’ and maintained despite frustration and challenges. A learner with individual interest is more likely to persevere under adversity (Hidi and Renninger, 2006). Thus, students are likely to maintain interest in the face of challenges when their situational interest evolves into individual interest, which is similar to intrinsic motivation (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020).

Intrinsic motivation means engaging in an activity out of interest, sheer enjoyment, challenge, or pleasure (e.g., Lepper et al., 2005; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Intrinsically motivated individuals tend to enjoy learning and exhibit interest and challenge-seeking characteristics. Considering their characteristics, the findings on a positive association between intrinsic motivation and learning goals (e.g., Barron and Harackiewicz, 2001; Froiland and Worrell, 2016; Grant and Dweck, 2003) and an incremental theory of intelligence (Cury et al., 2006; Haimovitz et al., 2011; Liu, 2021) are not surprising. Moreover, the positive relationship between intrinsic motivation and academic achievement (e.g., Åge Diseth et al., 2020; Gottfried et al., 2007) is understandable.

As a possible antecedent of individual interest similar to intrinsic motivation, situational interest in a given activity plays a significant role in achievement-related choices (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020). For example, researchers have identified gifted individuals’ interest in STEM areas as an important factor that influences their decisions to pursue STEM careers (Lubinski and Benbow, 2006; Webb et al., 2002). Wang’s research (2013a) also revealed that interest in STEM has the strongest association with students’ actual choice to pursue STEM fields, which is a critical step toward building a career in STEM.

However, individual interest—developed beyond situational interest—may be an inevitable requirement for academically gifted students in specialised STEM high schools. Individual interest may help alleviate the frustration that some students experience in academic situations as a result of comparing their own academic abilities with those of their equally talented classmates. Moreover, in challenging and frustrating academic situations, individual interest may motivate students to independently re-engage in particular subject areas or content, sustain curiosity, seek further knowledge, engage in challenges, and overcome frustration to meet their goals (Hidi and Renninger, 2006). Christensen et al.’s (2015) findings support our assertions regarding individual interest (similar to intrinsic motivation), indicating that self-motivation is the most crucial factor influencing student interest in STEM careers.

From a developmental perspective (Hidi and Renninger, 2006), individual interest may be critical in allowing students to overcome the challenges and setbacks in specialised STEM school environments. Accordingly, we included intrinsic motivation rather than interest in STEM areas to clarify the concept of interest in the hypothesised model predicting STEM career interest among academically gifted students in a specialised STEM school. In the model, we investigated how a growth mindset and learning goals are associated with intrinsic motivation and, subsequently, STEM career interest.

Mathematics achievement

Researchers have identified high mathematics achievement as a predictor of intent to major in STEM and interest in STEM careers (Wang, 2013b; Sadler et al., 2012). Wang (2013b) found a direct correlation between 12th-grade math achievement and intent to major in a STEM field. Sadler et al. (2012) also found an association between high grades in middle school math courses and increased intentions to pursue STEM careers throughout high school. In addition, Lubinski and Benbow (2006) and Webb et al. (2002) reported that gifted students’ mathematical abilities are critical in their STEM career choices. In this study, we, therefore, investigated how a growth mindset and learning goals relate to academically gifted students’ mathematics achievements and, subsequently, their interest in STEM careers.

Relation of mindsets of intelligence to goals, intrinsic motivation, and gifted students’ academic achievements

Researchers have found that gifted students tend to hold an incremental theory of intelligence (e.g., Esparza et al., 2014; Park et al., 2016), and Ayoub and Aljughaiman (2016) found that gifted students’ implicit theories of intelligence significantly affect their academic performance. Research indicates that achieving gifted students tend to hold incremental theories of intelligence, while underachieving gifted students hold more fixed theories about intelligence (Mofield and Peters, 2019). One particularly interesting study of implicit theories of intelligence and giftedness reported that academically gifted adolescents viewed intelligence as malleable and giftedness as fixed (Makel et al., 2015).

Although gifted students tend to espouse incremental theories of intelligence, comparisons between younger and older students show that older students’ implicit theories of intelligence align more with a fixed theory of intelligence than those of younger students (Ablard and Mills, 1996; Park et al., 2016). For instance, Park et al. (2016) examined grade 5–11 gifted students’ beliefs about intelligence and performance goals and found that older gifted students (grades 8–11) are more likely to believe that their intelligence is fixed and to pursue performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals than their younger counterparts (grades 5–7). Similarly, researchers have observed a general decline in intrinsic academic motivation as gifted students age (Gottfried et al., 2001). In addition, Gottfried et al. (2007) investigated the longitudinal relationship between intrinsic math motivation and achievement among students aged 9–17 and found that math motivation and achievement decreased over time, on average.

Research has shown that gifted students’ incremental beliefs about their innate abilities significantly affect their academic achievement (Ayoub and Aljughaiman, 2016; Mofield and Peters, 2019). Moreover, implicit theories of intelligence are shown to predict academic achievement through learning goals in general education students (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2007; Romero et al., 2014). Studies have also shown that an incremental theory of intelligence predicts intrinsic motivation in general education students (Cury et al., 2006) and intrinsic motivation and mathematics achievement through a learning goal orientation in general education students (Liu, 2021).

Relation of mindsets of intelligence to STEM career interest

Beyond the relationship between implicit beliefs about ability and academic achievement, researchers have recently explored the impact of implicit theories of intelligence on STEM career interests or STEM choices (Huang et al., 2019; Lytle and Shin, 2020; Van Aalderen-Smeets et al., 2019). For example, Lytle and Shin (2020) used data from first-year undergraduate students to demonstrate that incremental beliefs of intelligence predicted higher STEM efficacy, which predicted greater STEM interest. In addition, Van Aalderen-Smeets et al. (2019) found that incremental STEM ability beliefs predicted positive self-efficacy beliefs and increased STEM intentions. Huang et al. (2019) examined the impact of math anxiety, math self-efficacy, and implicit theories of intelligence on middle school students’ math and science career interests. Their findings showed that, for boys, intelligence mindsets were associated with math and science career interests through the mediating variable of math self-efficacy and that, for girls, a growth mindset was not a significant predictor of math and science career interests.

Research on the career decisions or development of gifted students (Jung, 2017; Robertson et al., 2010; Steenbergen-Hu and Olszewski-Kubilius, 2017) has emphasised the importance of ability and interest, consistent with early literature on the career decisions of intellectually gifted adolescents (e.g., Lubinski and Benbow, 2006). Robertson et al. (2010) re-emphasised the importance of cognitive abilities and vocational interest for career choice, performance, and persistence among gifted and top math and science graduate students. Jung (2017) showed the importance of occupational interest and enjoyment as predictors of intentions to pursue particular careers by examining the career decision-making of adolescents with high intellectual ability. Steenbergen-Hu and Olszewski-Kubilius (2017) found that gifted students’ personal interest in STEM positively predicts their earning STEM college degrees.

Most research on the effects of mindset on STEM career interests or choices was conducted with general education students; meanwhile, research on how mindset meaning systems help gifted students succeed in STEM pathways under challenging academic situations is lacking. Moreover, previous studies focusing on general education students did not consider mindset meaning systems or educational context as important components to examine mindset effects.

Current study

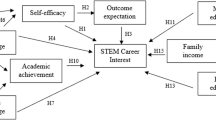

Within the challenging environment of STEM schools for academically gifted students, mindsets and achievement goals would be significant psychological factors to help these gifted students succeed academically and maintain intrinsic motivation (interest), particularly in mathematics, for pursuing STEM careers based on previous studies (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2007; Liu, 2021). Therefore, we investigated how a growth mindset and learning goals relate to math achievement and intrinsic motivation, which are associated with STEM career interest, in academically gifted students at a specialised STEM school. In particular, we focused on mathematics when examining the motivational constructs because mathematical ability is an important factor that influences whether gifted students pursue STEM careers, and adolescent students might have beliefs about their subject-specific abilities (Stipek and Gralinski, 1996), which is also a recommended way of measuring mindsets by Yan and Schuetze (2023). Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesised path analytic model (see Fig. 1).

Using the hypothesised model, we derived the following research questions:

First, what is the relationship between growth mindsets and learning goals, and how is this relationship associated with intrinsic motivation and math achievement among academically gifted students?

Second, how are psychological factors (GM, LG, and IM in Fig. 1) and math achievement associated with STEM career interest among academically gifted students? Is there an association between intrinsic motivation and math achievement among academically gifted students?

Method

Participants

The study sample comprised 144 students in grades 9–12 attending a full-day STEM high school (Academic-Year Governor’s Schools for gifted students) located in the state of Virginia; the school had a selective admission process. Students in this STEM high school were selected based on the following indicators: math and verbal scores from the school admission test; ratings of responses to essay prompts; grade point averages (GPA) in grades 7 and 8, including a core subject GPA and a math and science GPA; and teacher recommendations. We invited all students at the school to participate in the study via emails sent to their parents. Although all participants provided complete demographic information, some did not respond to actual survey items (n = 12). The final sample included 132 students with complete demographic and survey data (43.2% male; 37.1%, 23.5%, 22%, and 17.4% in grades 9, 10, 11, and 12, respectively). Most participants identified as Asian or Asian American (47.7%), followed by white (40.2%), African American (8%), Hispanic or Latino (2.3%), and other (9.1%).

Procedure

We obtained parental consent forms and student assent forms electronically. At the first distribution of the survey, we emphasised that student participation in the survey was voluntary and that students could withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Next, we used an online survey tool to distribute a motivational questionnaire to the parents of potential participants. The questionnaire assessed the implicit theory of math intelligence, math-oriented achievement goals, math-oriented intrinsic motivation, and STEM career interest. The questionnaire also asked for demographic information (e.g., gender) and mathematics grades. Parents who allowed their child to participate in the survey provided their electronic signature and allowed their child to complete the survey on their computer. The questionnaire required approximately 20 min to complete. Two weeks after the first distribution of the survey, we initiated the second distribution of the survey with a reminder about the survey sent to parents of potential participants. The reminder announced that some participants would receive a 10 USD e-gift card through prize drawings. This study was approved by the internal review board of the author’s university.

Variables in the study

We adapted a set of scales to assess motivational variables in the present study. For mathematics achievement, we asked participants to self-report their mathematics course grades. Finally, participants also self-reported race or ethnicity, gender, and grades. The questionnaire consisted of the following subscales:

Mindsets of Intelligence

Items used to measure the math mindsets (implicit theories of math intelligence) were adapted from the six-item implicit theories of intelligence scale (Dweck, 2000) for students older than 10. We adapted the scale to reflect adolescent students’ subject-specific ability beliefs (Stipek and Gralinski, 1996). On the adapted scale, we asked students to consider their abilities in mathematics rather than their general intellectual abilities, because research has demonstrated that mathematics performance critically influences STEM career interest. The six-item scale consists of three fixed mindset statements (e.g., You have a certain amount of mathematics intelligence, and you can’t really do much to change it) and three growth mindset statements (e.g., No matter who you are, you can significantly change your mathematics intelligence level). Respondents rated their agreement or disagreement for each item on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 6 (Strongly Disagree). To apply a path analysis to the hypothesised model shown in Fig. 1, we reverse-scored items: high (6) and low (1) scores on the mindsets of the math intelligence scale indicated strong agreement with growth and fixed mindsets, respectively, as in Blackwell et al. (2007). We calculated the composite score of the math mindset, a growth mindset in the hypothesised model, for the six items. The internal consistency estimate of scores from the present study was 0.933.

Learning goals

We selected and adapted items related to math-oriented learning goals from the Patterns of Adaptive Learning survey (Midgley et al., 1998) to reflect mathematics domain specificity and goals oriented toward success in mathematics. Students rated their agreement with each item on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 6 (Strongly Disagree). We reverse-scored all items: high scores (6) indicate high learning goals (e.g., I like schoolwork in mathematics that I’ll learn from, even if I make a lot of mistakes). The internal consistency estimate of scores was 0.926.

Intrinsic motivation

We selected and adapted items from Lepper et al. (2005) to measure intrinsic motivation toward success in mathematics. The present study used three of the scale’s sub-factors (challenge, curiosity, and independent mastery). Students rated their agreement with each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Very true for me) (e.g., I like hard work in mathematics because it’s a challenge; I like difficult work in mathematics because I find it more interesting). We calculated the composite intrinsic motivation score: high (5) scores indicated high intrinsic motivation. The internal consistency of the scores from the present study was 0.938 for intrinsic motivation.

Mathematics achievement

We collected the participants’ self-reported mathematics course grades to assess their mathematics performance. Students reported their grades for mathematics courses in the first, second, and third quarters of the most recent school year; we used the grades from the third quarter for data analysis. The students’ mathematics courses varied. Most 9th-graders reported enrollment in Algebra 2 or Pre-calculus, and 10th-graders enrolled in Pre-calculus or AP Calculus BC. The 11th-graders most frequently reported AP Calculus AB and BC, and the 12th-graders mainly reported AP Statistics, Linear Algebra, or AP Calculus AB/BC. Grades were measured on a four-point scale, with ‘4’ being the highest. Research indicates that high-achieving students are accurate self-reporters of grades and self-reported grades generally predict outcomes roughly as well as actual grades (Kuncel et al., 2005).

STEM career interest

We measured STEM career interest using the Career Interest Questionnaire (Tyler-Wood et al., 2010). Studies confirmed this instrument as a reliable measure of STEM attitudes for middle and high school students (e.g., Christensen et al., 2015; Peterman et al., 2016). The questionnaire consists of 12 items on three scales measuring these constructs: perception of a supportive environment for pursuing a career in science (e.g., My family is interested in the science courses I take), interest in pursuing educational opportunities that would lead to a career in science (e.g., I would like to have a career in science), and perceived importance of a career in science (e.g., I will have a successful professional career and make substantial scientific contributions). Students rated their agreement or disagreement for each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). We scored all items, with high (5) scores indicating a high interest in STEM careers. The internal consistency of the composite score of the scale was 0.907.

Data analysis

We applied descriptive statistics to summarise the variables used in the analysis to measure implicit theories of math intelligence, math-oriented learning goals, math-oriented intrinsic motivation, and STEM career interest, including correlations across all measures (Table 1). Next, we applied path analysis to the data to examine the factors affecting STEM career interest among respondents.

We checked multivariate normality with five variables used in the path analysis model for statistical validity. In univariate normality, no variable’s skewness and kurtosis are below −1 or above 1. However, based on Mahalanobis distances, six students showed extreme values (i.e., their \({\chi }^{2} > 11.07={\chi }_{5}^{2}\)). We carefully observed all six students’ data but found no coding errors; thus, we included the six cases in further analysis. Variance inflation factors for multicollinearity among five variables were less than 5, indicating no multicollinearity issues. After confirming these assumptions, we fit the path model (see Fig. 1) to our data. The hypothesised model (Fig. 1) was selected based on the literature as well as exploratory model comparison. Four models were compared: a full model with both direct effects of growth mindset to math achievement and intrinsic motivation, a model with one direct effect of growth mindset to math achievement, a model with one direct effect of growth mindset to intrinsic motivation, and a simple model without the two direct effects. Model comparisons were conducted with the likelihood ratio difference test (LRDT). No comparisons were statistically significant. For example, the comparison between the full model with both direct effects and the reduced model (our hypothesised model) indicated no significant difference between the two models, which suggested that the reduced model was the best-fitting model (LRDT statistic =0.934 ~ \({\chi }_{2}^{2}\) and p-value = 0.627).

As model evaluation criteria, we examined the approximate fit indices, including the comparative fit index (CFI), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The criteria for good model fit should be greater than 0.95 for CFI, less than 0.06 for RMSEA, and less than 0.08 for SRMR (Browne and Cudeck, 1993; Hu and Bentler, 1999). To examine the indirect effects within the hypothesised model, we used parametric bootstrap methods (Bollen and Stine, 1990) because Sobel test results are too conservative (MacKinnon et al., 1995). We summarised all indirect effects with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. The hypothesised model includes the variables of Growth Mindset (GM), learning goals (LG), intrinsic motivation (IM), mathematics achievement (Math), and STEM career interest (SCI). We used Mplus 8.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017) for all analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 shows the study’s descriptive statistics and pairwise correlations between variables. On average, participants’ scores indicated a growth mindset (mean = 3.914, SD = 1.071), learning goals (mean = 4.376, SD = 1.078), intrinsic motivation (mean = 3.261, SD = 0.877), math achievement (mean = 3.43, SD = 0.657), and STEM career interest (mean = 4.071, SD = 0.593). Pairwise correlations indicated that STEM career interest was positively correlated with a growth mindset (r = 0.08, p = 0.393), learning goals (r = 0.335, p < 0.001), intrinsic motivation (r = 0.348, p < 0.001), and mathematics achievement (r = 0.227, p < 0.05). Table 1 lists all other correlations.

Path analysis model with growth mindset, learning goals, intrinsic motivation, math achievement, and interest in STEM careers

Overall model fit

We fit the path analysis model in Fig. 1 to address the research questions. As shown in Table 2, with model fit indices and standardised and unstandardised parameter estimates of the final model (Fig. 2), the model explained the data well (\({\chi }_{4}^{2}\,=\,2.618\), df = 4, p = 0.624; CFI = 1.000; SRMR = 0.026 RMSEA = 0.000 with 90% CI between 0.000 and 0.108). The final model’s fit indices indicated good fit according to Hu and Bentler (1999). As endogenous variables, \({R}^{2}\) values of SCI, IM, Math, and LG were 0.137, 0.564, 0.153, and 0.037, respectively.

Significance of direct and indirect paths

All paths except the one from Math to SCI are significant, but the correlation between Math and IM is not significant (r = 0.023, p = 0.416). As sequential regressions, GM predicts LG (b = 0.192, p = 0.029), LG predicts IM (b = 0.604, p = 0.000) and Math (b = 0.243, p = 0.000), and IM predicts SCI (bIM = 0.216, pIM = 0.001). However, Math does not significantly predict SCI (bMath = 0.103, pMath = 0.163).

Using bootstrap methods, we examined two indirect effects of growth mindset on STEM career interest via math achievement and intrinsic motivation. While that via intrinsic motivation is significant (95% bootstrap CI = [0.005, 0.059]), that via math achievement is not (95% bootstrap CI = [−0.001, 0.018]).

Discussion

The present study examined whether the relationship between a growth math mindset (an incremental theory of math intelligence) and learning goals is directly and indirectly associated with intrinsic motivation, academic achievement, and interest in STEM careers among academically gifted high school students with talents in science and mathematics within a challenging academic environment. In response to the first research question, the findings regarding the relationships among growth mindset, learning goals, and math achievement were consistent with those presented in past studies (Blackwell et al., 2007; Chen and Pajares, 2010; Kanopka et al., 2020; Liu, 2021). We found a positive relationship between growth math mindset and learning goals, and learning goals were positively associated with math achievement. That is, among academically gifted students, the growth mindset was indirectly and positively related to academic performance through learning goals, consistent with other studies conducted among general education students (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2007; Liu, 2021). This finding indicates that academically gifted students with a growth math mindset were more likely to pursue learning goals and achieve higher grades in mathematics than those with a fixed mindset. This finding supports a recent study on mindsets, which demonstrated that gifted underachievers tend to have more fixed beliefs about intelligence than gifted achievers (Mofield and Peter, 2019).

Moreover, a growth math mindset was positively associated with learning goals, and learning goals were positively related to intrinsic motivation. This finding indicates that incremental theories are indirectly and positively associated with intrinsic motivation through learning goals—that is, academically gifted students who endorse an incremental theory of math intelligence are more likely to pursue learning goals and exhibit higher intrinsic motivation than those with an entity theory of math intelligence. This finding is consistent with Liu’s (2021) identification of statistically significant relationships among incremental theory of intelligence, learning goals, and intrinsic motivation in general education students. Overall, these findings suggest that mindset ‘meaning systems’ are associated with gifted students’ motivation and achievement in academically challenging and competitive environments with their equally talented peers.

We addressed the second research question by examining how the growth mindset meaning system relates to intrinsic motivation and math achievement, as well as its further association with interest in STEM careers. The results indicated that a growth math mindset is indirectly associated with interest in STEM careers through learning goals and intrinsic motivation. In other words, despite the low direct correlation between the growth mindset and intrinsic motivation and the meagre effect size (ES = 0.045), a growth mindset was indirectly associated with intrinsic motivation, which relates to high interest in STEM careers through learning goals. More specifically, students who hold growth math mindsets are driven to pursue learning goals related to high intrinsic motivation, which was associated with a high interest in STEM careers. The results reflect the importance of learning goals, a growth mindset meaning system. These findings are similar to results from other studies demonstrating the importance of interest in career intentions (Jung, 2017; Steenbergen-Hu and Olszewski-Kubilius, 2017) and the significant role of self-motivation in expressed interest in STEM careers (Christensen et al., 2015).

Unexpectedly, the present study’s findings did not support the relationship between math achievement and interest in STEM careers (ES = 0.009). This result was surprising given that researchers have consistently found math achievement to predict interest in STEM careers in both general and gifted students (Lubinski and Benbow, 2006; Sadler et al., 2012; Wang, 2013b). This result may be attributable to the participants’ characteristics. We collected data from only a single specialised STEM school with a selective admission process, where most of our participants are likely to be high-achieving students in mathematics. Thus, in the specialised environment of STEM schools, intrinsic motivation (interest) may be more important to maintain interest in STEM careers than math achievement. This possibility is partially supported by Webb et al.’s (2002) finding that students in the top 1% with respect to mathematical ability considered their interests to be the primary factor in determining their choices of undergraduate majors.

The second research question also addresses the relationship between math achievement and intrinsic motivation. Although previous studies found a statistically significant correlation between math achievement and intrinsic motivation (Åge Diseth et al., 2020; Gottfried et al., 2007; Haimovitz et al., 2011), the present study did not. Further research is necessary to determine whether intrinsic motivation is associated with academic achievement among academically gifted students within a homogeneous group in any path model.

The present findings emphasise the importance of a mediating variable—a learning goal orientation in the mindset ‘meaning system’ (Dweck and Yeager, 2019)—in maintaining intrinsic motivation and achieving success in mathematics within specialised STEM high schools for academically gifted students. Furthermore, the findings suggest that intrinsic motivation plays a significant role in maintaining STEM career interests within a challenging academic context.

Implications

The findings from this study indicate that a growth mindset is indirectly and positively related to intrinsic motivation and academic performance through learning goals. Although this study’s sample size was relatively small and composed of academically gifted students from a single specialised STEM school, the results suggest that parents and teachers of academically gifted students who are studying in challenging and competitive academic environments should encourage them to adopt a growth mindset. That is, parents and teachers should guide gifted children who are navigating challenging and stressful academic environments to foster an incremental meaning system (Molden and Dweck, 2006; Yeager and Dweck, 2020) by emphasising the process of learning, the importance of effort, the value of new strategies and help from others, and the need to maintain a positive attitude toward engaging in challenges.

Intrinsic motivation was significantly and directly associated with interest in STEM careers, despite math performance not being significantly associated with maintaining interest in STEM careers. In other words, the situational interests of academically gifted students within challenging academic environments must develop into individual interests to enable them to overcome frustrating academic situations in competition with equally talented peers. When students’ situational interests become individual interests (i.e., intrinsic motivation) (Eccles and Wigfield, 2020), they become increasingly motivated to independently re-engage in specific topic areas, maintain their curiosity, seek further information, and overcome frustrations to meet their goals (Hidi and Renninger, 2006). Accordingly, to foster success in STEM career pathways, parents and educators of academically gifted students in competition with their equally talented peers should encourage their children to develop intrinsic motivation by guiding them to continue exploring topics that they enjoy.

In conclusion, the above findings indicate that academically gifted students competing with equally talented peers would benefit from adopting a growth mindset meaning system for academic growth and intrinsic motivation in terms of maintaining their interest in STEM careers within challenging academic situations. In particular, academically gifted students in highly competitive school environments should be guided in overcoming failure and coping with competition from equally talented peers. An incremental meaning system may help them to reframe failures as opportunities for growth and maintain their interest in STEM careers.

Limitations

Despite the encouraging findings, this study has several limitations. Participants were from a single STEM school, and the number of participants was relatively small. Moreover, sampling was not random because the study population comprised academically gifted students attending a specialised STEM school with a highly selective admission process. Given the current sample size, constructing a latent variable model that fully accounts for measurement error was not feasible. Thus, the results should be interpreted cautiously, and the findings’ generalizability to other academically gifted students with talents in STEM areas may be limited. However, item-level distributions in our data were similar to those in previous studies. As such, the variables used in the current model may be meaningfully examined with more participants to corroborate the study findings. Another limitation was that math achievement was measured as a letter grade in the most recent math course. When a student took different math courses, the letter grade as a standardised achievement was what we could select as an alternative to the actual grade. As mentioned, researchers generally regard self-reported grades to predict outcomes approximately as well as actual grades (Kuncel et al., 2005). Finally, this study used path analysis rather than structural equation modelling owing to the small sample size. Although internal consistencies were high, we could have considered the growth math mindset, learning goals, and motivation as factors rather than linear composite scores.

Conclusions

The present study extends the literature on mindsets by demonstrating that a growth math mindset is indirectly associated with students’ interest in STEM careers through learning goals and intrinsic motivation. First, the present study emphasised the importance of a growth mindset meaning system (Dweck and Yeager, 2019) for academic growth and intrinsic motivation among academically gifted students in academically challenging environments. Given that a growth math mindset is indirectly linked to the academic achievement and intrinsic motivation of academically gifted students competing with their equally talented peers in challenging academic environments, the present study offers educators in these environments insights into factors that are important for encouraging gifted students to maintain an interest in their talent areas and develop their potential. Thus, future research should investigate how mindsets of academically gifted students affect multiple outcomes and how mindset interventions should be implemented to better support academically gifted students navigating the frustrating environments. In particular, such research would be meaningful for academically gifted students placed in highly selective school environments in competition with equally talented peers, in light of the fact that underachievement has been an issue among gifted students (e.g., Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2020).

Additionally, the present study investigated the direct and indirect effects of a growth mindset meaning system on intrinsic motivation, mathematics achievement, and, subsequently, interest in STEM careers among academically gifted students with talents in science and mathematics. Intrinsic motivation positively predicted interest in STEM careers, whereas mathematics achievement was not a significant predictor. Hence, the effects of psychological factors in the hypothesised model should be investigated with more academically gifted students from more specialised STEM schools. In addition, because the hypothesised model focused on math-oriented psychological variables, future research should include science-specific psychological variables in the hypothesised model to make it more comprehensive.

Lastly, we revealed the indirectly positive relationship between a growth mindset and intrinsic motivation through learning goals. Relatedly, several researchers exploring creativity regard intrinsic motivation as essential for reaching creative achievement (e.g., Amabile, 1983). Some characteristics exhibited by individuals espousing a growth mindset—for example, a preference for challenging tasks—echo the personality traits of creative individuals. In this light, extending research on mindset meaning systems into creativity would be beneficial.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available to avoid individual privacy being compromised, but they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ablard KE, Mills CJ (1996) Implicit theories of intelligence and self-perceptions of academically talented adolescents and children. J Youth Adolesc 25(2):137–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537340

Amabile TM (1983) The social psychology of creativity. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-5533-8

Aronson J, Fried CB, Good C (2002) Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. J Exp Soc Psychol 38(2):113–125. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2001.1491

Ayoub AEA, Aljughaiman AM (2016) A predictive structural model for gifted students’ performance: a study based on intelligence and its implicit theories. Learn Individ Differ 51:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.018

Barron KE, Harackiewicz JM (2001) Achievement goals and optimal motivation: testing multiple goal models. J Pers Soc Psychol 80(5):706–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.5.706

Blackwell LS, Trzesniewski KH, Dweck CS (2007) Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: a longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Dev 78(1):246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x

Bollen KA, Stine R (1990) Direct and indirect effects: classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Socio Methodol 20:115–140. https://doi.org/10.2307/271084

Browne MW, Cudeck R (1993) Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS (eds) Testing structural equation models. Sage Publications, p 136–162

Burgoyne AP, Hambrick DZ, Macnamara BN (2020) How firm are the foundations of mind-set theory? The claims appear stronger than the evidence. Psychol Sci 31(3):258–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619897588

Burnette JL et al. (2023) A systematic review and meta-analysis of growth mindset interventions: for whom, how, and why might such interventions work? Psychol Bull 149(3–4):174–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000368

Burnette JL, O’Boyle EH, VanEpps EM, Pollack JM, Finkel EJ (2013) Mind-sets matter: a meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychol Bull 139(3):655–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029531

Challenge Success: Student Survey Executive Summary (2019) Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology. https://tjhsst.fcps.edu/resources/challenge-success-student-survey-executive-summary

Chen JA, Pajares F (2010) Implicit theories of ability of grade 6 science students: relation to epistemological beliefs and academic motivation and achievement in science. Contemp Educ Psychol 35(1):75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2009.10.003

Christensen R, Knezek G, Tyler-Wood T (2015) A retrospective analysis of STEM career interest among mathematics and science academy. Int J Learn Teach Educ Res 10(1):45–58

Cury F, Elliot AJ, Da Fonseca DD, Moller AC (2006) The social-cognitive model of achievement motivation and the 2 x 2 achievement goal framework. J Pers Soc Psychol 90(4):666–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.666

Diseth Å, Mathisen FKS, Samdal O (2020) A comparison of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation among lower and upper secondary school students. Educ Psychol 40(8):961–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1778640

Dweck CS (2000) Self-theories: their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press

Dweck CS (2006) Mindset: the new psychology of success. Random House

Dweck CS, Leggett EL (1988) A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol Rev 95(2):256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Dweck CS, Yeager DS (2019) Mindsets: a view from two eras. Perspect Psychol Sci 14(3):481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166

Eccles JS, Wigfield A (2020) From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: a developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemp Educ Psychol 61:101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Esparza J, Schumow L, Schmidt JA (2014) Growth mindsets of gifted seventh-grade students in science. NCSSSMST J 19(1):6–13

Froiland JM, Worrell FC (2016) Intrinsic motivation, learning goals, engagement, and achievement in a diverse high school. Psychol Sch 53(3):321–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21901

Gottfried AE, Fleming JS, Gottfried AW (2001) Continuity of academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence: a longitudinal study. J Educ Psychol 93(1):3–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.3

Gottfried AE, Marcoulides GA, Gottfried AW, Oliver PH, Guerin DW (2007) Multivariate latent change modeling of developmental decline in academic intrinsic math motivation and achievement: childhood through adolescence. Int J Behav Dev 31(4):317–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025407077752

Grant H, Dweck CS (2003) Clarifying achievement goals and their impact. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(3):541–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.541

Haimovitz K, Wormington SV, Corpus JH (2011) Dangerous mindsets: how beliefs about intelligence predict motivational change. Learn Individ Differ 21(6):747–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.09.002

Harackiewicz JM, Barron KE, Tauer JM, Carter SM, Elliot AJ (2000) Short-term and long-term consequences of achievement goals: predicting interest and performance over time. J Educ Psychol 92(2):316–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.316

Harackiewicz JM, Durik AM, Barron KE, Linnenbrink-Garcia L, Tauer JM (2008) The role of achievement goals in the development of interest: reciprocal relations between achievement goals, interest, and performance. J Educ Psychol 100(1):105–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.105

Hidi S, Renninger KA (2006) The four-phase model of interest development. Educ Psychol 41(2):111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

Holdren JP, Lander ES (2012) Engage to excel: producing one million additional college graduates with degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Executive Report). President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Model 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang X, Zhang J, Hudson L (2019) Impact of math self-efficacy, math anxiety, and growth mindset on math and science career interest for middle school students: the gender moderating effect. Eur J Psychol Educ 34(3):621–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0403-z

Hunt JMV (1965) Intrinsic motivation and its role in psychological development. In: Levine D (ed) Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (Vol. 13, pp 189–282). University of Nebraska Press

Jung JY (2017) Occupational/career decision-making thought processes of adolescents of high intellectual ability. J Educ Gifted 40(1):50–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353217690040

Kanopka K, Claro S, Loeb S, West M, Fricke H (2020) Changes in social-emotional learning: examining student development over time [Working paper]. Policy Analysis for California Education. Stanford University. https://www.edpolicyinca.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/wp_kanopka_july2020.pdf

Kover DJ, Worrell FC (2010) The influence of instrumentality beliefs on intrinsic motivation: a study of high-achieving adolescents. J Adv Acad 21(3):470–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X1002100305

Kuncel NR, Credé M, Thomas LL (2005) The validity of self-reported grade point averages, class ranks, and test scores: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Rev Educ Res 75(1):63–82. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075001063

Lepper MR, Corpus JH, Iyengar SS (2005) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: age differences and academic correlates. J Educ Psychol 97(2):184–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.184

Li Y, Bates TC (2019) You can’t change your basic ability, but you work at things, and that’s how we get hard things done: testing the role of growth mindset on response to setbacks, educational attainment, and cognitive ability. J Exp Psychol Gen 148(9):1640–1655. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000669

Liu WC (2021) Implicit theories of intelligence and achievement goals: a look at students’ intrinsic motivation and achievement in mathematics. Front Psychol 12:593715. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.593715

Lu B, Deng Y, Yao X, Li Z (2021) Learning goal orientation and academic performance: a dynamic model. J Career Assess 30(2):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727211043437

Lubinski D, Benbow CP (2006) Study of mathematically precocious youth after 35 years: uncovering antecedents for the development of math-science expertise. Perspect Psychol Sci 1(4):316–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00019.x

Lytle A, Shin JE (2020) Incremental beliefs, STEM efficacy and STEM interest among first-year undergraduate students. J Sci Educ Technol 29(2):272–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-020-09813-z

MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH (1995) A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivar Behav Res 30(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3

Macnamara BN, Burgoyne AP (2023) Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychol Bull 149(3–4):133–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000352

Makel MC, Snyder KE, Thomas C, Malone PS, Putallaz M (2015) Gifted students’ implicit beliefs about intelligence and giftedness. Gifted Child Q 59(4):203–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986215599057

Midgley C, Kaplan A, Middleton M, Maehr ML (1998) The development and validation of scales assessing students’ achievement goal orientations. Contemp Educ Psychol 23(2):113–131. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1998.0965

Mofield EL, Peters MP (2019) Understanding underachievement: mindset, perfectionism, and achievement attitudes among gifted students. J Educ Gifted 42(2):107–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353219836737

Molden DC, Dweck CS (2006) Finding “meaning” in psychology: a lay theories approach to self-regulation, social perception, and social development. Am Psychol 61(3):192–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.192

Moon SM, Swift M, Shallenberger A (2002) Perceptions of a self-contained class for fourth and fifth-grade students with high to extreme levels of intellectual giftedness. Gifted Child Q 46(1):64–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620204600106

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2017) Mplus user’s guide: statistical analysis with latent variables (Vol. 8). Los Angeles, Muthén and Muthén

National Science Board (2014) Science and engineering indicators 2014 (NSB 14–01). Arlington, VA, National Science Foundation

National Science Board (2024) Science and engineering indicators 2024: the state of U.S. Science and engineering (NSB-2024-3). Alexandria, VA, National Science Foundation

Park S, Callahan CM, Ryoo JH (2016) Assessing gifted students’ beliefs about intelligence with a psychometrically defensible scale. J Educ Gifted 39(4):288–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353216671835

Paunesku D, Walton GM, Romero C, Smith EN, Yeager DS, Dweck CS (2015) Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychol Sci 26(6):784–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615571017

Peterman K, Kermish-Allen R, Knezek G, Christensen R, Tyler-Wood T (2016) Measuring student career interest within the context of technology-enhanced STEM projects: A cross-project comparison study based on the Career Interest Questionnaire. J Sci Educ Technol 25(6):833–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-016-9617-5

Robertson KF, Smeets S, Lubinski D, Benbow CP (2010) Beyond the threshold hypothesis: even among the gifted and top math/science graduate students, cognitive abilities, vocational interests, and lifestyle preferences matter for career choice, performance, and persistence. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 19(6):346–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410391442

Romero C, Master A, Paunesku D, Dweck CS, Gross JJ (2014) Academic and emotional functioning in middle school: the role of implicit theories. Emotion 14(2):227–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035490

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol 25(1):54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Sadler PM, Sonnert G, Hazari Z, Tai R (2012) Stability and volatility of STEM career interest in high school: a gender study. Sci Educ 96(3):411–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21007

Seaton M, Marsh HW, Craven RG (2010) Big-fish-little-pond effect: generalizability and moderation—two sides of the same coin. Am Educ Res J 47(2):390–433. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209350493

Sisk VF, Burgoyne AP, Sun J, Butler JL, Macnamara BN (2018) To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychol Sci 29(4):549–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617739704

Steenbergen-Hu S, Olszewski-Kubilius P (2017) Factors that contributed to gifted students’ success on STEM pathways: the role of race, personal interests, and aspects of high school experience. J Educ Gifted 40(2):99–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353217701022

Steenbergen-Hu S, Olszewski-Kubilius P, Calvert E (2020) The effectiveness of current interventions to reverse the underachievement of gifted students: findings of a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gifted Child Q 64(2):132–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986220908601

Stipek D, Gralinski JH (1996) Children’s beliefs about intelligence and school performance. J Educ Psychol 88(3):397–407. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.88.3.397

Subotnik RF, Olszewski-Kubilius P, Worrell FC (2012) A proposed direction forward for gifted education based on psychological science. Gifted Child Q 56(4):176–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986212456079

Subotnik RF, Tai RH, Rickoff R, Almarode J (2009) Specialized public high schools of science, mathematics, and technology and the STEM pipeline: what do we know now and what will we know in 5 years? Roeper Rev 32(1):7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190903386553

Taing MU, Smith T, Singla N, Johnson RE, Chang CH (2013) The relationship between learning goal orientation, goal setting, and performance: a longitudinal study. J Appl Soc Psychol 43(8):1668–1675. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12119

Thomas J, Williams C (2010) The history of specialized STEM schools and the foundation and role of the NCSSSMST. Roeper Rev 32(1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190903386561

Tipton E, Bryan C, Murray J, McDaniel MA, Schneider B, Yeager DS (2023) Why meta-analyses of growth mindset and other interventions should follow best practices for examining heterogeneity: commentary on Macnamara and Burgoyne (2023) and Burnette et al. (2023). Psychol Bull 149(3–4):229–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000384

Tofel-Grehl C, Callahan CM (2014) STEM high school communities: common and differing features. J Adv Acad 25(3):237–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X14539156

Tyler-Wood T, Knezek G, Christensen R (2010) Instruments for assessing interest in STEM content and careers. J Technol Teach Educ 18(2):345–368. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/32311/

Van Aalderen-Smeets SI, Walma van der Molen JH, Xenidou-Dervou I (2019) Implicit STEM ability beliefs predict secondary school students’ STEM self-efficacy beliefs and their intention to opt for a STEM field career. J Res Sci Teach 56(4):465–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21506

Wang X (2013a) Modeling entrance into STEM fields of study among students beginning at community colleges and four-year institutions. Res High Educ 54(6):664–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9291-x

Wang X (2013b) Why students choose STEM majors: motivation, high school learning, and postsecondary context of support. Am Educ Res J 50(5):1081–1121. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213488622

Webb RM, Lubinski D, Benbow CP (2002) Mathematically facile adolescents with math-science aspirations: new perspectives on their educational and vocational development. J Educ Psychol 94(4):785–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.785

Yan VX, Schuetze BA (2023) What is meant by “growth mindset”? Current theory, measurement practices, and empirical results leave much open to interpretation: commentary on Macnamara and Burgoyne (2023) and Burnette et al. (2023). Psychol Bull 149(3–4):206–219. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000370

Yeager DS, Dweck CS (2020) What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? Am Psychol 75(9):1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000794

Yeager DS, Hanselman P, Walton GM, Murray JS, Crosnoe R, Muller C, Tipton E, Schneider B, Hulleman CS, Hinojosa CP, Paunesku D, Romero C, Flint K, Roberts A, Trott J, Iachan R, Buontempo J, Yang SM, Carvalho CM, Dweck CS (2019) A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature 573(7774):364–369. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y

Yeager DS, Romero C, Paunesku D et al. (2016) Using design thinking to improve psychological interventions: the case of the growth mindset during the transition to high school. J Educ Psychol 108(3):374–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000098

Yeager DS, Walton GM, Brady ST, Akcinar EN, Paunesku D, Keane L, Kamentz D, Ritter G, Duckworth AL, Urstein R, Gomez EM, Markus HR, Cohen GL, Dweck CS (2016) Teaching a lay theory before college narrows achievement gaps at scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113(24):E3341–E3348. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1524360113

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Yonsei University Research Grant of 2022. This work was supported by the Curry School of Education Grant at the University of Virginia (Curry IDEAs 2015, Grant no: 136842-SP5CA-DR03164-31155).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SP contributed to the conception and design of the study, led data collection and interpretation, and wrote and revised the manuscript. JHR led data analysis and interpretation and revised the manuscript. CMC contributed to the design of the study and interpretation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Social and Behavioral Sciences (IRB-SBS) at the University of Virginia (Approval No: Project#2015-0506-00/ Initial Approval Date: January 13, 2016, Revised Approval Date: April 1, 2016, for a protocol amendment). All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards outlined in the Belmont Report.

Informed consent

All participants were fully informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, their right to withdraw from the study at any time, as well as the procedures for doing so. Information regarding anonymity, confidentiality, data use, potential risks and benefits was clearly informed. Data collection took place between May 1, 2016 and May 29, 2016. Written consent and assent were obtained electronically from both parents and students during this period. To obtain consent, the first author sent emails to the parents of students. Parents who agreed to their child’s participation provided an electronic signature and were then instructed to allow their child to participate in the survey on their computers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, S., Callahan, C.M. & Ryoo, J.H. Impact of growth math mindset, learning goals, intrinsic motivation, and math outcomes on STEM career interest among gifted students in STEM education. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1862 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06132-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06132-9