Abstract

There are significant health disparities that exist in Washington, DC, especially when considering variables such as race, socioeconomic status, place of residence, and language. This study analyzes and compares the medical humanities literature to scientific literature to identify if the medical humanities can illuminate more of the root causes of health disparities. A systematic search was conducted, identifying a total of 119 articles for analysis. Of those articles, 51 were tagged as medical humanities papers, or studies exploring the ethical, historical, literary, philosophical, and religious dimensions of medicine and health. Data extracted from each article included age, gender, and race of the study population, the condition studied, and significant barriers to health. Analysis revealed that medical humanities papers were significantly more likely to identify systemic information gaps (78.4% vs 30.9%, p < 0.001) and stigma-related barriers (27.5% vs 5.9%, p = 0.002) compared to scientific papers. The results underscore that methods used within the medical humanities literature can uniquely identify social, cultural, economic, and political drivers of health that are often under addressed by traditional quantitative methods and therefore should be utilized in the education of future healthcare and public health professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

When Washington, DC health data are stratified by race and place of residence, some segments of the population have significantly poorer health profiles. These disparities are rooted in the social determinants of health—the conditions in which people are born, live, work, grow, and age—as well as structural determinants, which encompass the broader systems, policies, and institutions that control, distribute, allocate, and withhold health hazards and resources (Hahn, 2021). Social and structural determinants of health, including structural racism such as historical redlining practices, have created entrenched inequities in Washington, DC (Egede et al., 2023; King et al., 2022). For example, predominantly Black neighborhoods in DC experience higher rates of chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, and hypertension, and poorer maternal health outcomes when compared to their white counterparts (Chaturvedi et al., 2024; Chinn et al., 2020; Egede et al., 2023; Jones et al., 2019; Kerr et al., 2022; Tyris et al., 2022). Key social determinants affecting DC residents include inadequate or unstable housing, food insecurity, and exposure to environmental pollutants, all of which have a profound impact on human health (Adjei-Fremah et al., 2023; Essel et al., 2024; Jones et al., 2019; King et al., 2022; Tyris et al., 2022). Economic determinants prevent many individuals from accessing timely healthcare services, leading to delays in diagnosis and treatment, particularly for those in historically disenfranchised communities (LaVeist et al., 2023; Lukowsky et al., 2022). Collectively, these social and structural determinants of health have yielded stark citywide disparities in key health metrics—infant mortality and life expectancy (Lukowsky et al., 2022).

Despite existing documentation of these disparities, comprehensive research exploring the social and structural determinants that create barriers to healthcare is limited. Many studies rely on numerical data, focusing on barriers to care such as geographic distance and socioeconomic status to highlight differential outcomes (Buhumaid et al., 2015; Burnett et al., 1995; Yilmaz, 2013). These types of analyses are limited when exploring factors that are less quantifiable and subjective, such as the following: language barriers, cultural beliefs about health and illness, trust in the healthcare system, perceptions of bias and/or discrimination, and systemic racism as a barrier both to access and desire to seek both healthcare and social services. These aspects play a critical role in understanding the root causes of health disparities.

One field that specifically addresses these qualitative dimensions is medical humanities, which emerged in the 1960s as a response to concerns that healthcare, with its focus on scientific specialization, was losing touch with patients and the human dimensions of illness and suffering (Wailoo, 2022). The field has since evolved to encompass broader questions about health, illness, and the human condition and employs diverse methodological approaches—from narrative analysis to historical inquiry and qualitative methods—to understand how cultural, social, and political factors shape health experiences and healthcare delivery. While traditional medical humanities focused primarily on health professions education and practice, contemporary approaches emphasizes the importance of centering marginalized voices and challenging dominant narratives in healthcare (Yun et al., 2017). This critical strand of medical humanities provides frameworks for understanding how power dynamics, structural inequalities, and social determinants of health intersect to create differential health outcomes and experiences of care. As critical medical humanities has emerged as a distinct orientation within the field, scholars increasingly emphasize three key pillars (Viney et al., 2015):

-

1.

examines health, illness, and medical care through diverse lenses, including humanities, arts, social sciences, and activism - moving beyond just the clinical encounter to understand medicine’s broader social and cultural contexts.

-

2.

analyzes how medicine, health, and illness are shaped by multiple factors, including human experiences, cultural practices, social inequalities, and political/economic systems.

-

3.

integrates different methods and perspectives (from literature, philosophy, history, arts, etc.) to critically examine and enrich our understanding of health, disease, and medical practice beyond just the biomedical model.

Given medical humanities’ engagement of these qualitative dimensions of health, comparison with empirical scientific approaches may demonstrate whether these distinct methodological approaches reveal different causal pathways and barriers to care. However, few studies have systematically compared these approaches. This scoping review seeks to address this gap and better understand health and healthcare disparities by incorporating insights from both quantitative and qualitative research. In doing so, it aims to offer a more holistic understanding of the barriers to healthcare for Washington, DC residents. By comparing different methodological approaches through a medical humanities lens, we will explore not only what can be measured but also what is often overlooked in quantitative studies. This comparative approach reflects the growing recognition that medical humanities offers essential perspectives and tools for addressing health equity (Mathieu and Martin, 2023).

While the call to incorporate humanistic and liberal arts education into medical training has existed for well over a century (Bleakley, 2015; Rabinowitz, 2021), its importance has grown. Through interviews, narratives, behavioral analysis, and other qualitative methods, medical humanities offer a conduit for patient experiences, which can be missing from traditional medical education that focuses on the pathophysiology of disease (Anil et al., 2023; Rabinowitz, 2021). Amid rapid advancements in medical technologies and increasing systemic pressures to meet clinical benchmarks, concerns have emerged about whether the compassionate, humanistic aspects of medicine are receiving adequate emphasis (Pedersen, 2010; Rabinowitz, 2021; Wald et al., 2019). This led to the establishment of initiatives such as the Association of American Colleges’ (AAMC) Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education (FRAHME), which argues for integrative experiences, such as narrative medicine, reflective writing, and theater, with the arts and humanities to strengthen the education for future physicians. Additionally, this initiative argues that education should embrace mixed-methods research practices. These approaches have been adopted at institutions such as Johns Hopkins, Georgetown, Howard, Brigham and Woman’s Hospital, and University of Wisconsin-Madison (Georgetown-Howard Center for Medical Humanities and Health Justice; Johns Hopkins Center for Medical Humanities and Social Medicine; Katz and Khoshbin, 2014; Mi et al., 2022; Zelenski et al., 2020) By transforming medical education with these experiences, the FRAHME initiative supports development of key physician competencies such as medical knowledge, interpersonal skills, perspective taking, and social advocacy. These are essential as medical education and public health evolves.

Given this context, our scoping review addresses three key objectives:

-

1.

To systematically map the literature on health inequities in Washington, DC, with particular focus on how cultural, social, and political determinants contribute to these disparities (King and Cloonan, 2020).

-

2.

To analyze the research methods used to study health inequities, evaluating the effectiveness of various approaches in measuring disparities, capturing lived experiences, and accounting for contextual factors.

-

3.

To examine the strengths and limitations of different methodological investigations in providing comprehensive insights into health outcomes. Furthermore, we aim to highlight gaps in the existing research and propose innovative methodological frameworks for future studies.

Many of the health inequities in DC are the result of deeply embedded structural factors, such as racial segregation, which continues to impact policies affecting majority minority communities today requires an interdisciplinary approach that integrates social and cultural perspectives. Addressing structural barriers to care requires an interdisciplinary approach that integrates social and cultural perspectives alongside scientific inquiry. This review represents the first comprehensive analysis of its kind, by comparing quantitative and qualitative approaches to understanding health inequities in DC. By examining both scientific and medical humanities literature, we aim to provide a more complete picture of healthcare barriers and their impact on diverse populations.

Methods

Article selection

A systematic literature search was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, APA PsycInfo (all via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), Web of Science Core Collection, and Sociological Abstracts (via ProQuest). Search criteria were broad and included a combination of database-specific subject headings and key terms related to health inequities and disparities, with a geographical preference for the Washington, DC, Maryland, and Virginia (DMV) area. We purposefully chose to have a broad search criterion to maximize the research articles. There were no limitations set on the year published. Please see the supplemental material for full reproducible search strategies.

Inclusion criteria for the search detailed that the article must have come from a peer-reviewed journal. In addition, the article must address a specific disease condition as opposed to a more generalized paper. The study had to have taken place in only the DC area, with surrounding areas in Maryland and Virginia also considered. One reviewer independently carried out primary screening of the title and abstract to identify articles eligible for inclusion. A second reviewer was available to discuss any discrepancies and helped with final determinations on whether the article would be included in the final data set.

Data Extraction

Data from each article was carried out using a Google form. Relevant demographic data was collected from each article, such as location, age range, gender identity, and ethnicity. Age ranges were categorized as the following: children (0–10 years), adolescents (11–20 years), young adults (21–30 years), adults (31–60 years), and elderly (61+ years). Gender identities were categorized as follows: male, female, transgender male, and transgender female. Ethnicities were categorized as follows: black, white, Asian, and Hispanic. Then articles were classified as either scientific or as the medical humanities. Given our narrow geographic scope, we broadened the definition of medical humanities papers to include studies that employed a humanities, social sciences, or qualitative approach to collect data. We made this decision to ensure a sufficient sample size for meaningful analysis. This often-included interviews, focus groups, and narratives. We also looked at the disease condition being studied and identified significant barriers to care presented. After extracting all the barriers to care described in all the selected papers, they were further characterized into one of the following groups: geography, financial burden, language, stigma related to patient identity, systemic information gap, and lack of hospital resources. One author was involved in conducting coding the barriers to care, and then thematically analyzing the data into determined categories. Categories were determined based on results from the extracted data. Further explanations of papers included in these categories can be found in Table 1.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using RStudio (Version 2024.04.0). Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize categorical variables. Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test were used to compare interested variables between scientific and medical humanities articles. All tests were conducted with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

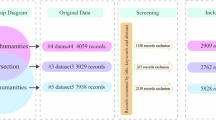

A total of 1211 articles were imported from the various databases. A final 119 articles were selected for analysis. Of these 119 articles, 68 were classified as scientific studies, while 51 were classified as medical humanities studies. This process is summarized in Fig. 1. A list of citations for the studies that were included in the final analysis is reported in the supplemental material.

Articles were selected from various databases based on key phrases targeting healthcare disparities and health inequities in the DC region. Articles were then screened initially based on title and abstract, then by the full contents in order to ensure they meet inclusion criteria before being classified as either a scientific article or medical humanities article (Haddaway et al., 2022).

Results of the demographics of the populations represented in the selected articles are as follows. In terms of age representation, 15.1% of the articles included children, 21% included adolescents, 41.2% included early adults, 74.5% included adults, and 37% included the elderly population. In terms of gender identity, 67.2% included males, 95.8% included females, 1% included transgender males, and 4% included transgender females. In terms of ethnicity, 89% of the articles represented a Black population, 55.5% represented a White population, 45.4% represented a Hispanic population, and 19.3% represented an Asian population. Figure 2 depicts this demographic information stratified for whether the article was identified as a medical humanities article. There were no significant differences for many of the demographic variables except for representation of the Hispanic ethnicity, with scientific articles having significantly more representation of this ethnic group (p = 0.036).

There were no significant differences amongst demographic variables except for the Hispanic ethnicity group.

In terms of barriers to care, 61.8% of the scientific articles and 33.3% of the medical humanities articles discussed barriers related to geography, and that rate was significantly different between scientific and medical humanities articles (p = 0.004). 42.6% of the scientific articles and 43.1% of the medical humanities articles discussed barriers related to financial burden. 2.9% of the scientific articles and 9.8% of the medical humanities articles discussed barriers related to language. 5.9% of the scientific articles and 27.5% of the medical humanities articles discussed barriers of stigma related to patient identity. The rate of barriers of stigma related to patient identity discussed was significantly different between scientific and medical humanities articles (p = 0.002). 30.9% of the scientific articles and 78.4% of the medical humanities articles discussed barriers of failure of the healthcare system to properly educate patients, which was significant different between the two groups (p < 0.001). 1.5% of the scientific articles and 3.9% of the medical humanities articles discussed barriers related to lack of hospital resources. A summary of these findings is represented in Fig. 3.

Significant differences were found when addressing geographical barriers to care (p = 0.004), stigma related to the patient’s identity (p = 0.002), and failure of healthcare system to properly educate patients (p = <0.001).

Discussion

Our scoping review highlights three key findings that align with the objectives outlined at the beginning of this review.

Objective 1

To systematically map the literature on health inequities in Washington, DC

Our review shows that significant healthcare inequities persist in Washington, DC, despite decades of research and intervention. Articles that were included in the final analysis ranged in year of publication from 1976 to 2023, demonstrating that these inequities have been studied for nearly fifty years. More importantly, they suggest that such disparities have been present for far longer. Over this period, medicine and healthcare technology continued to progress, but as evidenced by this scoping review, access to medical advancements and the resulting improvements in health outcomes has been limited to certain populations (Bhavnani et al., 2016). These persistent inequities over nearly five decades underscore the entrenched nature of structural barriers and underscore how different research approaches might expand our understanding of where they exist and how we might address them.

Objective 2

To analyze and evaluate the research methods used to study health inequities our comparative analysis of scientific and medical humanities literature revealed distinct but complementary insights. While there were no significant differences in the demographic data represented, we found marked differences in the barriers to care identified. Medical humanities studies were significantly more likely to identify:

-

1.

Patient mistrust of the healthcare system due to stigma and discrimination

-

2.

Systemic failures in patient education (78.4% vs 30.9%, p < 0.001)

-

3.

Cultural barriers and health beliefs that affect care-seeking behavior

Scientific studies were more likely to identify geographic barriers to care (61.8% vs 33.3%, p = 0.004), indicating their strength in documenting quantifiable, structural impediments. This difference demonstrates that research approach fundamentally guides which barriers become visible and therefore addressable.

Objective 3

To examine the strengths and limitations of different methodological investigations in understanding barriers to care

The results of the scoping review highlight how medical humanities approaches identify crucial barriers to care that often go undetected in quantitative studies. Specifically, studies using medical humanities methods captured lived experiences of discrimination, historical patterns affecting healthcare-seeking behavior, and communication failures that leave patients distrustful or uninformed about resources and services. Scientific studies, while less likely to document these experiences, were strong at quantifying the socioeconomic and geographic factors affecting healthcare access. Rather than viewing these approaches as competing, our findings underscore that they offer complementary insights for a more comprehensive understanding of healthcare disparities.

Overall, these findings suggest three key implications for practice, policy, and research

-

1.

Healthcare system reform: The need for institutional efforts to go beyond addressing geographic and socioeconomic barriers in order to dismantle systemic barriers. Our review suggests that addressing systemic mistrust and communication failures is also necessary to create a welcoming environment for patients in the healthcare system.

-

2.

Education (Patient, Provider, and System): The need for targeted efforts to educate communities about healthcare services and accessibility options, with particular attention to cultural competency. Institutional investment in social, cultural, and structural competency training and development of communication systems that ensure accessibility and transparency.

-

3.

Research methodology: The value of integrating diverse methodological approaches, as scientific articles show the impact of socioeconomic status and geography upon patient access to care, while medical humanities uncover barriers that resist quantification.

The findings from this study can directly impact medical and public health education, practice, and research. Our comparative analysis shows how empirical methods alone do not provide a complete picture of healthcare barriers in Washington, DC. Where scientific studies identified geographic and financial barriers, medical humanities approaches revealed stigma-related and communication barriers, and systemic information gaps that remain largely undetected by quantitative analysis. As historian of medicine, Keith Wailoo observed, the field of medical humanities emerged from crises in medicine and society. Our findings suggest that persistent health inequities in DC (and in other regions/cities) are an ongoing crisis, demanding new research approaches that capture both measurable obstacles and those that resist quantification. This methodological integration extends to education, supporting initiatives such as AAMC’s FRAHME that advocate for interdisciplinary approaches in training future healthcare professionals. Trainees preparing to work in diverse communities need to understand how different research perspectives demonstrate the many dimensions of health disparities—preparing them to understand and address the complicated barriers to care. As seen in our study of America’s capital, where health disparities have persisted across the nearly five decades we studied, the stakes are too high, and the inequities too entrenched to rely on a single lens for understanding or intervention.

Limitations

First, our requirement that articles demonstrate barriers in relation to a specific disease state may have limited the number of medical humanities articles, though only 5 such articles were excluded. Second, articles were excluded that extended beyond the DC or surrounding DMV areas. Surrounding areas in Maryland and Virginia were included, as many DC hospitals have branches and satellite hospitals that expand into these areas. While there are many nationwide studies that investigate large-scale health inequities, we felt that for the purpose of this scoping review, it was essential to focus on DC and the DMV areas, especially given their unique history and patient population. Third, the categorization of humanities, social science, and qualitative studies under the definition of medical humanities introduces some conflation between qualitative research and medical humanities studies. This decision was intentional to ensure a sufficient sample size for analysis, but we recognize that it may limit the specificity of our findings to medical humanities literature alone.

Conclusion

This is the first scoping review analyzing the current state of literature on healthcare disparities in Washington, DC, a city deeply affected by a longstanding history of social inequities. By engaging in a comparative analysis of distinct research methods, we highlight the necessity of looking beyond purely quantitative approaches, particularly those found in medical humanities articles, in providing unique perspectives on barriers to care. Our findings demonstrate the importance of medical humanities in informing future health equity initiatives and medical student education. This integrated approach provides a more holistic understanding of the complex factors influencing healthcare access and outcomes in the city of DC.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adjei-Fremah S, Lara N, Anwar A, Garcia DC, Hemaktiathar S, Ifebirinachi CB, Samuel R (2023) The effects of race/ethnicity, age, and Area Deprivation Index (ADI) on COVID-19 disease early dynamics: Washington, D.C. case study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 10(2):491–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01238-1

Anil J, Cunningham P, Dine CJ, Swain A, DeLisser HM (2023) The medical humanities at United States medical schools: a mixed method analysis of publicly assessable information on 31 schools. BMC Med Educ 23(1):620. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04564-y

Bhavnani SP, Narula J, Sengupta PP (2016) Mobile technology and the digitization of healthcare. Eur Heart J 37(18):1428–1438. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv770

Bleakley A (2015) When I say … the medical humanities in medical education. Med Educ 49(10):959–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12769

Buhumaid R, Riley J, Sattarian M, Bregman B, Blanchard J (2015) Characteristics of frequent users of the emergency department with psychiatric conditions. J Health Care Poor Underserv 26(3):941–950. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2015.0079

Burnett CB, Steakley CS, Tefft MC (1995) Barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening in underserved women of the District of Columbia. Oncol Nurs Forum 22(10):1551–1557

Chaturvedi A, Zhu A, Gadela NV, Prabhakaran D, Jafar TH (2024) Social determinants of health and disparities in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Hypertension 81(3):387–399. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.21354

Chinn JJ, Eisenberg E, Artis Dickerson S, King RB, Chakhtoura N, Lim IAL, Bianchi DW (2020) Maternal mortality in the United States: research gaps, opportunities, and priorities. Am J Obstet Gynecol 223(4):486–492.e486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.021

Egede LE, Walker RJ, Campbell JA, Linde S, Hawks LC, Burgess KM (2023) Modern day consequences of historic redlining: finding a path forward. J Gen Intern Med 38(6):1534–1537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08051-4

Essel K, Burke M, Fischer L, Weissman M, Dietz W (2024) Food insecurity screening and referral practices of pediatric clinicians in metropolitan Washington, DC. Children 11(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091147

Georgetown-Howard Center for Medical Humanities and Health Justice. https://www.mhhj.org/

Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, McGuinness LA (2022) An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev 18(2):e1230. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1230

Hahn RA (2021) What is a social determinant of health? Back to basics. J Public Health Res 10(4). https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2021.2324

Johns Hopkins Center for Medical Humanities and Social Medicine. https://hopkinsmedicalhumanities.org/

Jones KK, Anderko L, Davies-Cole J (2019) Neighborhood environment and asthma exacerbation in Washington, DC. Annu Rev Nurs Res 38(1):53–72. https://doi.org/10.1891/0739-6686.38.53

Katz JT, Khoshbin S (2014) Can visual arts training improve physician performance? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 125:331–341. discussion 341-332

Kerr D, Aram M, Crosby KM, Glantz N (2022) A persisting parallel universe in diabetes care within America’s capital. EClinicalMedicine 43:101244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101244

King CJ, Buckley BO, Maheshwari R, Griffith DM (2022) Race, place, and structural racism: a review of health and history in Washington, D.C. Health Aff 41(2):273–280. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01805

King CJ, Cloonan P (2020) Health disparities in the black community: an imperative for racial equity in the District of Columbia

LaVeist TA, Pérez-Stable EJ, Richard P, Anderson A, Isaac LA, Santiago R, Gaskin DJ (2023) The economic burden of racial, ethnic, and educational health inequities in the US. JAMA 329(19):1682–1692. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.5965

Lukowsky LR, Der-Martirosian C, Dobalian A (2022) Disparities in excess, all-cause mortality among black, Hispanic, and white veterans at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042368

Mathieu IP, Martin BJ (2023) The art of equity: critical health humanities in practice. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 18(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13010-023-00149-1

Mi M, Wu L, Zhang Y, Wu W (2022) Integration of arts and humanities in medicine to develop well-rounded physicians: the roles of health sciences librarians. J Med Libr Assoc 110(2):247–252. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2022.1368

Pedersen R (2010) Empathy development in medical education–a critical review. Med Teach 32(7):593–600. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903544702

Rabinowitz DG (2021) On the arts and humanities in medical education. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13010-021-00102-0

Tyris J, Gourishankar A, Ward MC, Kachroo N, Teach SJ, Parikh K (2022) Social determinants of health and at-risk rates for pediatric asthma morbidity. Pediatrics 150(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-055570

Viney W, Callard F, Woods A (2015) Critical medical humanities: embracing entanglement, taking risks. Med Humanit 41(1):2–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2015-010692

Wailoo K (2022) Patients are humans too: the emergence of medical humanities. Daedalus 151(3):194–205

Wald HS, McFarland J, Markovina I (2019) Medical humanities in medical education and practice. Med Teach 41(5):492–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497151

Yilmaz K (2013) Comparison of quantitative and qualitative research traditions: epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. Eur J Educ Res Dev Policy 48(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12014

Yun X, Guo J, Qian H (2017) Preliminary thoughts on research in medical humanities. Biosci Trends 11(2):148–151. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2017.01085

Zelenski AB, Saldivar N, Park LS, Schoenleber V, Osman F, Kraemer S (2020) Interprofessional Improv: using theater techniques to teach health professions students empathy in teams. Acad Med 95(8):1210–1214. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003420

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SG Conceptualization, methodology, initial literature search, data collection, statistical analysis, drafting and critical revision, visualization. SD Methodology, Initial literature search strategy, revision. XG Statistical analysis, revision. CK Analysis, draft review and critical revision. LK Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, drafting and critical revision, project supervision and administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This scoping review article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not obtained as this scoping review article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the first author used ChatGPT in order to lightly edit transitions between paragraphs in an early draft. This was then edited by the first author, and subsequent drafts were reviewed and edited by the entire authorship team. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghatti, S., Dorris, S., Geng, X. et al. Mapping DC health inequities: a scoping review comparing scientific and medical humanities approaches. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06157-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06157-0