Abstract

Improving energy efficiency is not only the key to achieving energy conservation, carbon reduction and green development, but also the way to promote the high-quality development of China’s economy. This article measures the total factor energy efficiency (TFEE) of Chinese cities and uses the Energy Rights Trading Pilot Policy (ERTP) as a quasi-natural experiment to evaluate the impact of this market-based environmental regulation policy on TFEE using a difference in differences (DID) model. The results show that ERTP can significantly promote the improvement of TFEE in Chinese cities. This effect is more obvious in coastal cities, high-grade cities and resource-based cities. ERTP can promote the upgrading of industrial structure and enhance the ability of green technology innovation, thereby promoting the improvement of TFEE. ERTP has a negative spatial spillover effect on the TFEE of neighboring regions. This article not only provides empirical support for revealing the complex effects of market incentive based environmental regulation in developing economies, but also provides important theoretical references and practical inspirations for the nationwide promotion and differentiated policy design of ERTP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy is not only the material basis for human survival and development, but also the lifeblood of the economic and social development of a country or region (Nasreen and Anwar, 2014; Shahbaz et al., 2022). However, China has a series of problems such as large energy consumption, continuous growth of energy demand, and low energy efficiency, which not only leads to the increasingly prominent contradiction between resources, environment and climate, but also seriously hinders the high-quality development of China’s economy (Su and Liang, 2021). In 2022, China’s total annual energy consumption reached 5.41 billion tons of standard coal, making it the world’s largest energy consumer (Wang et al., 2022). According to the China Energy Big Data Report 2023, China’s coal consumption accounted for 56.2% of total energy consumption in 2022, and the energy consumption elasticity coefficient also climbed to 0.97, indicating that China’s economic growth is highly dependent on high polluting and energy-intensive energy consumption patterns. In the face of increasing energy supply and demand conflicts and serious environmental pollution problems, China should adopt practical policies to improve energy efficiency (Chen et al., 2021). There is no doubt that improving energy efficiency and creating maximum economic, social and environmental benefits with minimal energy consumption are essential for high-quality economic development (Borozan, 2018; Li and Lin, 2017; Wang et al., 2013). As a core indicator to measure energy economics, TFEE can accurately reflect changes in energy efficiency and technology, and identify the state of energy consumption (Guo and Yuan, 2020).

In recent years, with China’s rapid economic development and increasing energy demand, China has become the world’s largest energy importer and carbon emitter (Cui and Cao, 2023; Li and Wang, 2022; Pan and Dong, 2022). Excessive energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions have caused serious energy shortages and environmental degradation problems in China (Song et al., 2023). In order to solve the increasingly serious energy and environmental problems, the Chinese government has issued a series of energy industry policies (Zhao et al., 2021), covering energy factor inputs, technical support, renewable energy subsidies and regulatory policies. Strict regulatory measures limit energy development and production efficiency improvement (Kong et al., 2020). In September 2016, the National Development and Reform Commission proposed to carry out pilot work on the paid use and trading of energy-consuming rights in Zhejiang, Fujian, Henan and Sichuan Provinces in 2017 (Wang et al., 2023). ERTP is based on Coase’s property rights theory. It emphasizes the reduction of energy consumption intensity through source control and market orientation (Che and Wang, 2022), which is conducive to promoting energy conservation and consumption reduction at a lower cost, and promoting high-quality economic and social development (Wang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022).

As a significant institutional innovation in the practice of green development concept, ERTP is a significant measure to promote the reform of ecological civilization system. The implementation of ERTP is of great significance for improving TFEE and achieving the dual control goals of total energy consumption and intensity. ERTP has been shown to help reduce carbon emissions and promote energy conservation. However, the impact of ERTP on TFEE remains unclear. “Can ERTP improve TFEE?” “Through what channels does ERTP affect TFEE?” “Does ERTP have a spatial spillover effect on TFEE?”

This paper uses the panel data of 280 prefecture-level cities in China from 2010 to 2020 to explore the impact and mechanism of ERTP on TFEE. The contribution of this paper is as follows. Firstly, theoretically, this study explores the impact of ERTP on TFEE from the perspective of market-based incentive-based environmental regulation. This not only provides a new theoretical framework for understanding the complex effects of market-based incentive-based environmental regulation, but also expands the application of Coasean property rights theory in the energy sector. Second, methodologically, this study develops a method for measuring urban energy consumption based on satellite nighttime light data and incorporates a non-radial super slacks-based measurement (Super-SBM) model to accurately measure city-level TFEE, effectively addressing the data acquisition difficulties and measurement biases inherent in traditional methods. Third, in terms of policy practice, this study finds that ERTP can significantly improve TFEE in pilot cities, with the policy effect being more pronounced in coastal, high-tier, and resource-rich cities. This provides a scientific basis for policymakers to implement differentiated regional energy policies. Fourth, the negative spatial spillover effects identified in this study reveal the uneven allocation of resources across regions under market-based incentive-based environmental regulation, providing important theoretical guidance and empirical evidence for policymakers in designing regional coordination mechanisms.

Literature review

TFEE

As a core issue in the field of energy economy, TFEE has broken through the limitations of traditional single factor efficiency in its measurement framework. TFEE is based on Solow’s concept of total factor productivity and introduces the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method (Färe et al., 1994; Honma and Hu, 2014; Zhang et al., 2011). Based on a comprehensive consideration of various input factors such as energy, labor, and capital, the energy efficiency under multiple input and output conditions is systematically characterized by incorporating expected and unexpected outputs for evaluation. Especially in the context of increasing energy and environmental constraints, improving TFEE is seen as the core path to achieving green growth and high-quality development.

From the perspective of influencing factors, factors such as technological innovation, industrial structure, economic openness, and financial development will all have an impact on TFEE. Among them, technological innovation is the core driving force for improving TFEE. Xu et al. (2024) found that digital technology innovation has a more significant effect on improving TFEE in eastern provinces. Lu and Li (2024) found that digital technology innovation mainly enhances TFEE by improving environmental responsibility fulfillment and internal control quality, and has a stronger promoting effect on TFEE of large enterprises and state-owned enterprises. The optimization of industrial structure is an important support for the evolution of TFEE. With the shift of economic focus from high energy consuming and high polluting heavy industries to service industries and strategic emerging industries with higher added value and lower energy intensity, the overall energy efficiency of the economy has significantly improved (Mulder and de Groot, 2012). At the institutional level, there are significant spatial differences in the impact of economic openness and regional market integration on TFEE. Su and Liang (2021) found that due to the high level of economic openness, the improvement of energy productivity in China’s coastal areas relies more on market integration to achieve efficient flow and allocation of factor resources, thus matching the high level of openness. Green finance also plays an important role in the improvement of TFEE. Guo et al. (2023) demonstrated that green finance has a spatial spillover effect, which can improve the energy efficiency of local and surrounding areas, and Internet development and environmental regulation are important channels for green finance to further promote energy efficiency.

Environmental policies on TFEE

With the increasingly serious environmental problems, whether environmental regulation can improve TFEE has become a research hotspot in the field of environmental economics.Based on neoclassical economics, scholars believe that environmental regulation increases the cost of corporate pollution control, which has a “countervailing effect” on productive inputs and innovative activities, and thus inhibits the improvement of TFEE (Hancevic, 2016). Some scholars have put forward the opposite view from a dynamic point, arguing that appropriate environmental regulation can not only promote technological innovation, but also produce an “innovation compensation effect”, which partially or completely offsets the negative impact of cost-effectiveness, and then promotes the improvement of TFEE. It is known as the “Porter hypothesis” (Porter and Linde, 1995). Many scholars have verified the validity of the “Porter hypothesis” from the perspective of different types of environmental regulation (Song et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2019; Wu and Lin, 2022). In addition, scholars have found a nonlinear relationship between the two [33].

The mechanisms by which different types of environmental regulatory policies affect the goals of “reducing pollution” and “increasing efficiency” also vary (Xie et al., 2017). Command and control environmental regulation policies and market incentive environmental regulation policies are the two mainstream perspectives in current research. Command and control environmental regulation policies mainly refer to the government’s mandatory measures such as setting emission standards, technical specifications, and deadline management to directly constrain the environmental behavior of enterprises. Li et al. (2023) pointed out that under restrictive pollution control policies, enterprises often allocate resources to environmental protection facilities at the production front and emission control at the production end to directly reduce pollutant emissions. These pollution control measures not only reduce pollutant emissions, but also bring “compliance costs” to enterprises. However, the ‘innovation compensation effect’ has failed to compensate for the ‘compliance costs’ brought about by pollution control, making it difficult for command and control environmental regulation policies to achieve the dual goals of’ pollution reduction ‘and’ efficiency improvement ‘simultaneously. Hong et al. (2024) believe that command and control environmental regulation policies can also balance efficiency improvement while ensuring emission reduction effects, and that “pollution reduction” and “efficiency improvement” are not necessarily in conflict. Market incentive based environmental regulation policies rely more on price mechanisms, property rights systems, and other means to guide enterprises to achieve environmental goals through independent technological innovation and energy conservation and emission reduction. Due to their higher flexibility and adaptability, such policies are considered to have more potential in long-term incentives for enterprises to achieve “pollution reduction” and “efficiency improvement” (Wang et al., 2022).

In summary, existing literature has indirectly explored the relationship between environmental policies and TFEE from different theoretical perspectives and regulatory types, but no unified conclusion has been reached yet. Meanwhile, there is relatively little research in academia on ERTP. The existing literatures mainly focus on the indicators allocation of ERTP (Pan and Dong, 2022), energy-saving effects (Che and Wang, 2022), economic effects (Wang et al., 2023), and the connection with policy systems such as carbon emissions trading (Yizhong Wang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). However, few scholars have studied the impact on TFEE from the perspective of ERTP. Therefore, this article starts from the perspective of ERTP and directly explores the actual impact of ERTP on TFEE, providing theoretical and empirical basis for evaluating its policy performance.

ERTP on TFEE

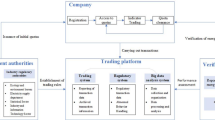

Green technology innovation effect

The impact mechanism of ERTP on TFEE is shown in Fig. 1. According to Schumpeter’s innovation theory, green technology innovation is a “creative destruction” process of economic development. It breaks the traditional high pollution and high energy consumption production mode by introducing new color processes, green products, and green services, forming new competitive advantages and growth momentum (Tzeng, 2014). However, the distortion of energy factor prices formed with the help of administrative pricing or subsidies has led to an underestimation of energy usage costs, and the lack of intrinsic motivation for enterprises to invest in energy conservation, consumption reduction, and green technology, which has suppressed the enthusiasm for green technology innovation. At the same time, green technology innovation also has a “dual externality” characteristic, where the positive externality of innovative knowledge spillover and the negative externality of pollution emissions often inhibit its development. But the Coase theorem states that as long as property rights are clear and transaction costs are low, market mechanisms can effectively solve externalities and achieve Pareto optimal allocation of resources. Based on this, ERTP establishes tradable property rights for energy use rights, returning the originally distorted energy prices to the market price level that reflects marginal social costs. On the one hand, it corrects the distortion of factor prices, and on the other hand, it enables enterprises to bear the real energy consumption costs and green innovation benefits in market transactions, effectively resolving the “dual externality” dilemma of green technology innovation and promoting enterprises to engage in green technology innovation.

The compliance pressure of ERTP and the additional income obtained through the sale of energy-consuming indicators can encourage enterprises to carry out green technology innovation (GTI), thereby improving the overall technological efficiency of the industry, reducing energy consumption, and thus promoting the improvement of TFEE. According to Porter’s hypothesis, moderate environmental regulation can stimulate enterprises to carry out green technology innovation, offset compliance costs through the “innovation compensation effect”, and achieve a win-win situation of environmental benefits and efficiency improvement (Porter and Linde, 1995). When the energy consumption of enterprises exceeds the free quota allocated by the government, enterprises can purchase limited energy consumption indicators in the energy-consuming right trading market, which will increase the production cost of enterprises and bring severe energy-saving pressure to enterprises. However, the energy-consuming right trading market can promote the formation of a balanced energy-consuming right trading price, which also provides regulated enterprises with incentives to reduce costs, forcing enterprises to increase technology investment (Porter and Linde, 1995), and promote enterprises to reduce energy consumption through green technology innovation. Enterprises obtain the “innovation compensation effect” and make up for the cost of purchasing energy-consuming indicators and establish cost advantages (G. Du et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2020; Porter and Linde, 1995). With the improvement of green innovation capabilities, TFEE will also be greatly improved (Sun et al., 2019; Wurlod and Noailly, 2018). Enterprises can reduce energy consumption and improve energy efficiency by optimizing production equipment, production processes, and improving resource recycling rates, thereby improving TFEE (Chen et al., 2019). The application of green technology innovation can enable enterprises to provide better green products for the society and guide consumers to green consumption through marketing activities. Consumer demand for green products will in turn promote enterprises to carry out green production, thereby forcing enterprises to transform to clean and green production, and then promote the improvement of TFEE. Thus, this paper proposes the following hypothesis.

H1: ERTP can effectively promote the improvement of green technology innovation capabilities, thereby improving TFEE.

Industrial structure upgrading effect

According to the Pareto Clark theorem, as the level of economic development continues to improve, labor will gradually shift from the primary industry to the secondary industry, and then to the tertiary industry. This process is accompanied by the reconfiguration of production factors such as capital and technology, forming the core connotation of industrial structure upgrading. As a market-based environmental regulatory tool, ERTP drives the transformation and upgrading of industrial structure towards green and low-carbon direction (Du et al., 2021).

ERTP mainly works together through the “forcing mechanism” and “guiding mechanism” to upgrade the industrial structure, thereby inducing a “structural dividend” and promoting the concentration of social resources towards low pollution, low-energy consumption, and high value-added industries, thereby achieving sustained improvement in TFEE. ERTP establishes energy use rights as scarce tradable property rights, makes energy use costs explicit, and incorporates them into the marginal cost consideration system of enterprises, promoting high energy consuming enterprises to face real environmental cost pressures. Based on the assumption of rational economic agents, in the face of this endogenous market punishment mechanism of externalities, enterprises will take corresponding measures to reduce energy costs and maintain their competitive position (Chen and Ma, 2021). In highly competitive industries, companies have thin profit margins and are highly sensitive to cost changes. The compliance costs brought by ERTP will directly translate into survival pressure, forcing high energy consuming enterprises to undergo technological transformation or directly exit the market, accelerating the survival of the fittest and the elimination of outdated production capacity. At the same time, low-energy enterprises can gain stronger market competitiveness by leveraging their cost advantages and the benefits brought by energy use rights transactions, thereby amplifying the “incentive guidance” effect of policies. Even in industries with high market concentration, with the increasing improvement of the energy trading market mechanism and the continuous improvement of regulatory systems, policy pressure will gradually be internalized in the business behavior of enterprises. Through mechanism design, it can stimulate the willingness of enterprises to undergo green transformation and promote the industrial structure to continuously move towards a green, intensive, and efficient direction. With the upgrading of the industrial structure, the production factors in the market will be more effectively allocated. With the continuous release of the “industrial structure dividend” (Li and Lin, 2019), social resources such as energy will be reallocated among industrial sectors, promoting the development of low-pollution, low-energy-consumption, high-value-added industries, and improving the ecological efficiency of society (Han et al., 2021), thereby effectively promoting the improvement of TFEE. Thus, this paper proposes hypothesis H2.

H2: ERTP can improve TFEE by promoting industrial structure upgrading.

Spatial spillover effect

The spatial spillover effect refers to the non-local impact of a region’s behavioral activities and their consequences on other regions in the spatial dimension, usually manifested as the “siphon effect” or “trickle down effect” (Chen and Wang, 2022). From the perspective of spatial economics, regional environmental regulatory policies can induce resource reallocation and industrial redistribution between regions, which not only affects local TFEE, but may also have significant spatial externalities on TFEE in surrounding areas through factor flow, industrial transfer, and policy imitation (Liu et al., 2020).

The implementation of ERTP not only affects the energy usage decisions of local enterprises, but may also trigger changes in the industrial structure between regions, thereby affecting the TFEE of neighboring areas. On the one hand, according to the “pollution paradise hypothesis”, when high-energy consuming enterprises face stricter environmental constraints and higher compliance costs, they may shift some of their high-energy consumption production activities to neighboring non-pilot areas with relaxed policies and lower factor costs for the purpose of maximizing profits. The new economic geography theory points out that enterprises will comprehensively consider factors such as production costs, market access, and institutional environment in the process of site selection. The intensity changes of environmental regulations will affect the spatial distribution balance, leading to the relocation of polluting industries. In the “tournament style competition” pattern of local governments in China, in order to attract investment and maintain fiscal and employment growth, some regions will relax environmental constraints, lower factor prices, and form “regulatory depressions”, thereby attracting high-energy consuming enterprises to move in (Chen et al., 2018), ultimately leading to an increase in energy consumption in these regions, forming negative spatial spillover effects, and suppressing the improvement of TFEE in surrounding areas. On the other hand, according to the theory of “pollution halo effect”, high polluting enterprises may be forced to introduce cleaner production processes, adopt more efficient equipment and technologies in order to adapt to higher environmental standards and regulatory systems in the host region during their outward migration, especially to cities or regions with higher regulatory levels. This may result in positive spillover effects of green technology spillover and environmental performance improvement in the host region. However, considering the current differences in regional environmental governance capabilities in China, financial pressure among local governments, and fierce competition for investment, the “pollution paradise hypothesis” is more common in reality, and its negative externalities have a more significant inhibitory effect on TFEE in neighboring regions. Hypothesis 3 is proposed.

H3: ERTP will not only promote the improvement of TFEE in the region, but also have a negative spatial spillover effect on neighboring regions through the transfer of high-energy-consuming industries.

Models and data

Models

The differences-in-differences (DID) model, as a policy effect evaluation method, can largely avoid the problem of endogeneity. Therefore, the net effect of the pilot policy is evaluated by constructing a DID model to measure the difference between the experimental group and the control group before and after the implementation of ERTP. The model is constructed as follows (Yang et al., 2021).

i and t represent city and time, respectively. TFEEit indicates the total factor energy efficiency of city i in year t. Postt is a time dummy variable, which is set as 1 when t ≥ 2017, otherwise 0. Treati is the city dummy variable. Treati is set as 1 if the city is the pilot city with energy-consuming rights trading, otherwise it is 0. The coefficient α explains the impact of ERTP on TFEE. Xit represents the control variables that affect TFEE. γi and δt are dummy variables that control for urban fixed effects (FEs) and temporal fixed effects, respectively. μit is the residual term.

Indicators

Variable to be explained

TFEE is the variable to be explained. In this paper, the Super-SBM model is used to measure TFEE. To eliminate dimensional differences between different variables and make them comparable, this paper also standardizes the dependent variable. The Super-SBM model can take into account the relationship between multiple input and output indicators, and comprehensively evaluate decision-making units (DMUs) with efficiency values greater than 1, making the results more accurate. This model assumes that the production system has n DMUs. Each DMU has m inputs, s1 desirable outputs, and s2 undesirable outputs. The formula is as follows.

ρ represents the efficiency value. \({x}_{io}^{t}\), \({{\rm{y}}}_{ro}^{t}\), and \({{\rm{y}}}_{ko}^{t}\) are the inputs, desirable outputs, and undesirable outputs of the DMU, respectively. \({s}_{i}^{-}\) and \({s}_{r}^{+}\) indicates the slacks of inputs and outputs. λ is a column vector.

Labor force and capital are selected as input indicators, which are expressed as year-end employment and capital stock in each city, respectively. Due to the lack of energy data in prefecture level cities, this article adopts a non-intercept linear model to allocate provincial total energy consumption to prefecture level cities as energy input based on nighttime light values (Wu et al., 2014). Nighttime lighting data can objectively reflect the production and living conditions of human society, and is therefore widely used in fields such as socio-economic research and ecological environment assessment. However, due to issues such as high geographic spatial resolution and low saturation values in nighttime light data, there are errors in brightness measurement in some areas. Therefore, when using nighttime light data, it is necessary to calibrate the relevant data to eliminate noise interference (Bennett and Smith, 2017). This article uses stable nighttime light data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the United States, which includes lights emitted from cities, towns, and other places with persistent light sources, and removes background noise and interference. Research has shown that there is a significant positive relationship between lighting and energy consumption. The brighter the nighttime lighting, the more intensive the economic activity, and the corresponding energy consumption is also higher (Amaral et al., 2005; Elvidge et al., 2010). Therefore, using nighttime light data and provincial total energy consumption to measure the energy consumption of prefecture level cities is relatively reliable. Real GDP of each city is chosen as the desirable output indicator. Industrial sulfur dioxide emissions and industrial soot emissions by city are selected as the undesirable outputs.

Core explanatory variable

ERTP (Treat×Post) is the core explanatory variable. The value of Treat×Post in the pilot cities in 2017 and later is set as 1. Otherwise, the value is set as 0.

Control variables

The factors affecting TFEE are very complex. In order to obtain objective estimates of policy effects, this article controls for variables that may affect TFEE over time (Guo and Yuan, 2020; Hong et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022). This paper selects control variables such as the degree of openness, economic development level, population density, industrialization level, and financial development level. Among them, the degree of openness (Open) is measured by the proportion of import and export volume to GDP. The level of economic development (Economy) is expressed as the logarithm of real GDP per capita. Population density (Density) is measured by the logarithm of the proportion of the population of a prefecture-level city to the area of an administrative region. Foreign direct investment (Foreign) is expressed as the logarithm of the amount of foreign capital actually utilized. The level of industrialization (Industry) is measured as a percentage of GDP in terms of industrial value added. The level of financial development (Finance) is measured using the balance of loans of financial institutions as a percentage of GDP at the end of the year.

Data sources

In order to maximize the balance panel data, this paper excludes four municipalities and cities with serious data deficiencies. Finally, this paper analyzes 280 prefecture-level cities (excluding Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan) from 2010 to 2020. City-level data are mainly derived from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook. The missing values of individual samples are completed by combining local statistical yearbooks, statistical bulletins or linear interpolation. The total correlation data on energy consumption at the city level is derived from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook.

Empirical results analysis

Benchmark regression results

Table 1 shows the results of the benchmark regression of ERTP and TFEE. Individual and temporal bidirectional fixed effects are introduced in regression model and standard errors are clustered to the individual level. Columns (1) and (2) represent the regression results of ERTP to TFEE without and with adding control variables, respectively. The results show that the coefficients of the interaction terms are significantly positive, indicating that ERTP has a significant promotion effect on TFEE.

Robustness test

Parallel trend hypothesis test and dynamic effect

In order to avoid the problem of collinearity, this paper takes the current period of policy implementation as the reference period to test the parallel trend and dynamic effect test (Wang et al., 2020). The results are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2. The interaction coefficients of TFEE before the pilot of ERTP are not significant, indicating that there is no significant difference between the pilot cities and non-pilot cities before 2017, and the assumption of parallel trend is satisfied. In terms of the dynamic effect of the policy, in the first year after policy implementation, the effect of ERTP on improving TFEE was not significant, mainly due to the time lag of policy transmission and the slow adjustment of enterprises. Policies often need to go through a multi-level transmission process from formulation to implementation, and the impact effects are gradually released Enterprises need to invest in new equipment or improve processes to reduce energy consumption, which often requires cross year cycles from decision-making, technology selection, funding to installation and commissioning, making it difficult to achieve large-scale results in the short term. The interaction coefficients in the second and third years after the implementation of the policy are significantly positive, indicating that ERTP has a significant promotion effect on TFEE, which proves the robustness of the results. However, there is a one-year lag in this promotion effect, which may be because it needs time to improve TFEE.

Add control variables

To further verify the robustness of the benchmark regression results, this paper introduces control variables such as green finance index, government intervention level, and marketization level on the basis of the original model, in order to eliminate other interfering factors that may affect TFEE and enhance the credibility of policy effect identification. Among them, the Green Finance Index (GreenFI) integrates multiple indicators such as green credit, green investment, and green insurance through the entropy method, comprehensively reflecting the regional ability to allocate green financial resources and the degree of support for green development The degree of government intervention is characterized by the proportion of local government general public budget expenditure to regional GDP, reflecting the direct intervention intensity of the government in resource allocation and macroeconomic regulation Marketization level is measured by the ratio of total retail sales of consumer goods to regional GDP, reflecting the vitality and completeness of market mechanisms. The regression results are shown in Table 3. After adding the above control variables, the coefficient of the interaction term is still significantly positive, which verifies the robustness of the results in this paper.

PSM-DID test

This paper uses propensity score matching (PSM) method for calibration. This method can solve the problem of sample selection bias by matching each experimental group sample to a specific control group sample, and then use the DID method according to the matched results. In this paper, the nearest neighbor matching (1:2) in the caliper is used to score the propensity of the data. Seen from Fig. 3, the absolute value of the standardization bias of each variable is significantly reduced after matching, indicating that PSM solves the problem of sample selection bias better, and the data have a better matching effect. Seen from Fig. 4, most of the observations are within the common value range. In addition, the kernel density map before and after matching is also plotted, as shown in Figs. 5 and 6 respectively. After PSM treatment, the gap between the experimental group and the control group is narrowed, and the probability density distribution trend is roughly the same, which also shows the rationality of PSM. The regression results after PSM processing are shown in Table 4. The coefficient of interaction terms is significantly positive regardless of whether the control variable is added or not, and ERTP still significantly improves the TFEE of the pilot cities, indicating that the conclusions are still robust.

Eliminate policy interference

In order to better ensure the robustness of the regression results, this paper discusses other competitive policies that may affect TFEE to exclude other potential influencing factors. The low-carbon provincial pilot and carbon emission trading pilots carried out in 2010 and 2011 have similarities in the nature, purpose and implementation of energy trading rights, which may have a potential impact on the benchmark results. Therefore, this paper excludes provinces and cities in these regions in the sample. The regression results are shown in columns (1) and (2) in Table 5. After the National Development and Reform Commission issued the National Adjustment and Transformation Plan for Old Industrial Bases (2013–2022), old industrial bases faced drastic industrial structure transformation and upgrading and many environmental regulatory measures. Therefore, 95 prefecture-level old industrial cities in our sample are excluded, and the regression results are shown in columns (3) and (4). The innovation pilot cities policy in 2018 may improve the level of urban energy-saving technological innovation by optimizing the urban industrial structure, promoting financial development, and attracting talent agglomeration. This policy is similar to the implementation of ERTP, which may interfere with the identification of causal relationships. Therefore, this part of the sample is excluded from the sample, and the regression results are shown in columns (5) and (6). After excluding the interference of relevant policies, the results obtained in this paper are significantly positive, indicating that competitive policy has no effect on the significance of the benchmark regression results. It also verifies the robustness of our results.

Counterfactual analysis

The use of the DID method presupposes that the experimental and control groups are comparable. In order to better exclude the interference of other random factors, this paper conducts counterfactual analysis from region and time dimensions. In the regional dimension, this paper randomly selects half of the cities from the experimental group and the control group as the “pseudo” experimental group and the “pseudo” control group, respectively, and uses 2017 as the policy implementation year to test the consistency with the benchmark regression. The results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 6. In the time dimension, this paper takes 2015 and 2016 as the hypothetical policy implementation year, and constructs the interaction terms of dummy variables and experimental group dummy variables in one year and two years before the policy occurs. The results are shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 6. The coefficients of the new interaction terms are all positive but not significant, indicating that ERTP have no significant effect on the TFEE of the experimental group and the control group, whether changing the city of policy implementation or advancing the policy implementation time. The actual pilot cities and implementation years can indeed significantly improve the TFEE, supporting the reliability of the regression results.

Endogenous test

The DID method overcomes the problem of endogeneity by comparing the experimental group and the control group. However, this presupposes that the pilot cities of ERTP are randomly selected among all prefecture-level cities, which is not the case in fact. The selection of pilot cities using ERTP may be influenced by other potential factors, which interfere with the DID estimation results and affect the accuracy of the results. Therefore, this paper utilizes instrumental variable (IV) to address endogeneity issues (Angrist and Krueger, 2001). In this paper, 104 major rivers in China are used to calculate the density of rivers flowing through each prefecture-level city and is used as an IV. In terms of correlation, cities adjacent to rivers have lower transportation costs, higher industrial agglomeration, and relatively high energy consumption, so they are more likely to be selected as pilot cities for ERTP, which is also in line with the correlation assumption of instrumental variables. In terms of exogeneity, the density of rivers, as an objective natural geographical factor, originates from historical geological and hydrological conditions and is not subject to reverse intervention from recent energy policies or economic behaviors. After controlling for variables such as Open, Economy, Industry, and Marketization that may affect TFEE, river density does not directly or indirectly affect TFEE through other channels, so it conforms to the exogenous assumption of instrumental variables. Considering that river density is a constant that does not change with time, this paper uses the product of river density and dummy variables in each year to construct an IV with temporal variation effect, and uses the two stage least square (2SLS) method for test (Nunn and Qian, 2014). The results are shown in Table 7. The coefficients of the first stage core variables are significantly positive at the 1% level, with or without the control variables, and pass the Lagrange multiplier (LM) test and the Cragg-Donald Donald Ward test, indicating that the instrumental variables are valid. The coefficients for the core variables in the second stage are also significantly positive, consistent with the benchmark regression. ERTP has a significant role in improving TFEE, which also proves the robustness of our results.

Heterogeneity analysis

Heterogeneity of urban location features

Compared with coastal cities, the capacity of industrial clusters in inland cities is relatively weak, and this location disadvantage is likely to limit the improvement of TFEE. Therefore, this paper divides the cities into coastal cities and inland cities for heterogeneity testing, constructs the location feature dummy variable (Coast), assigns the coastal city as 1 and the inland city as 0. This paper introduces the interaction between the location feature dummy variable and the policy dummy variable into the benchmark regression model. The results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 8. Regardless of whether individual fixed effects are added or not, the coefficients of the new interaction terms are significantly positive, indicating that ERTP has a greater impact on the improvement of TFEE in coastal cities. The possible reason is that coastal cities have convenient transportation, rely on imports and exports to drive economic development, and have a large degree of industrial agglomeration, resulting in strong government supervision. Coastal cities are significantly superior to inland cities in terms of economic, human capital, and material capital.

Heterogeneity of city level

There are great differences in the scale, development degree and external influence of different levels of Chinese cities. This article categorizes cities based on the changes in sales prices of commercial residential properties released by the National Bureau of Statistics in 2021. In order to explore the influence of city level heterogeneity on TFEE, this paper divides all cities into first-class cities and second-class cities for heterogeneity testing, constructs a city-level dummy variable (Grade), and assigns the first-class city as 1 and the second-class city as 0. Based on the benchmark model, this paper adds the interaction between the city-level dummy variable and the policy dummy variable. The results are shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 8. The coefficient of the new interaction term is significantly positive at the level of 5%, regardless of whether the control variable was added, indicating that ERTP could significantly promote the improvement of TFEE in the first-class city. The possible reason is that first-class cities have high levels of economic development, strong R&D and innovation capabilities, and are more able to attract foreign investment and talent inflow.

Heterogeneity of resource-based cities

The efficiency of energy will be affected by a series of factors such as resource endowment and energy price. In order to investigate the heterogeneity of ERTP on the TFEE of resource-based cities, this paper constructs a resource-based city feather dummy variable (Resource), and sets the resource-based city to 1 and the non-resource city to 0. The interaction between resource-based city feature dummy variables and policy dummy variables is introduced into the benchmark regression model. The results are shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 8. Regardless of whether the control variable is added, the coefficient of the new interaction term is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that ERTP has a significant improvement effect on the TFEE of resource-based cities. The possible reason is that resource-based cities are dominated by high energy consuming and high emission resource-based industries. The policy of energy rights trading increases the cost of traditional energy use, forcing local enterprises to break through the path dependence of the “resource curse”, accelerate the elimination of high energy consuming and low value-added industries or carry out green technology innovation, thereby promoting the improvement of TFEE.

Mechanism analysis

Green technology innovation

In order to test the role of ERTP on TFEE, this paper examines whether enterprises will be forced to strengthen their green innovation capabilities under the implementation of ERTP and improve TFEE to make up for the energy costs caused by exceeding the energy consumption quota. This article uses the proportion of green invention patent applications and the proportion of green invention patent authorizations as indicators to measure green innovation capability, and the results are shown in Table 9. Regardless of whether control variables are added, ERTP has a significant positive impact on green innovation ability. In ERTP areas, companies will actively adopt green innovation strategies in order to seek long-term development, and improve TFEE by improving related technologies and equipment, thereby reducing energy costs.

Industrial structure upgrading

In order to test whether ERTP leads to industrial structure upgrading (ISU), this paper uses the proportion of tertiary industry added value to GDP to measure urban industrial structure upgrading, and tests the mechanism by observing the influence relationship between core explanatory variables and intermediary variables. The results are shown in Table 10. The coefficients of the core explanatory variables are significantly positive at the 1% level, regardless of whether control variables are added. This is consistent with previous research results and also confirms H2. The implementation of ERTP can significantly promote the development of the tertiary industry, promote ISU, and then promote the improvement of TFEE.

Extended analysis

Spatial correlation test

Before performing a spatial econometric analysis, a spatial autocorrelation test is needed. In this paper, the global Moran index (Moran’I) based on the inverse distance spatial weight matrix is selected to test the spatial autocorrelation of ERTP and TFEE. The results are shown in Table 11. The Moran’I index of TFEE is positive at a significant level of 1%, indicating that TFEE has significant spatial autocorrelation, that is, agglomeration occurs in spatial distribution.

Spatial econometric models

This paper further performs the LM test, and the results are shown in Table 12. LM Lag, LM Lag (Robust) and LM Error (Robust) of the spatial lag model (SLM) and LM Error (Robust) of the spatial error model (SEM) are significant, indicating that there are spatial effects and SLM, SEM and spatial Durbin model (SDM) can be applied. Since the SDM model combines the advantages of SLM and SEM models, it can explore the spatial correlation relationship between the explanatory variables and the explanatory variables of neighboring cities. Therefore, this paper gives priority to the SDM model.

In this paper, Hausman test, fixed-effect selection, LR test are carried out sequentially, and SDM with double fixed effect is determined as the optimal choice. In this paper, the following SDM is constructed.

i and t represent city and time, respectively. ρ represents the spatial autoregressive coefficient. W are respectively the inverse distance spatial weight matrix and the asymmetric spatial economic distance matrix. φ1 and φc are the elastic coefficients of the core explanatory variables and the spatial interaction terms of the control variables. The remaining variables have the same meaning as Eq. 1. Table 13 reports the spatial effect of ERTP on TFEE. Seen from column (1) and (5), whether under the inverse distance spatial weight matrix or the asymmetric spatial economic distance matrix, the spatial autoregressive coefficient ρ of TFEE is significantly positive, indicating that TFEE has significant spatial utility. The spatial spillover effect is decomposed into direct effects, indirect effects, and total effects. Seen from column (3) and (7), both under the inverse distance spatial weight matrix and the asymmetric spatial economic distance matrix, the indirect effect is significantly negative, indicating that ERTP has a negative inhibitory effect on improving the TFEE of neighboring cities. This proves H3 and also validates the validity of the ‘Pollution Paradise Hypothesis’. Due to the implementation of ERTP, enterprises with large energy consumption and low TFEE bear higher energy costs, which in turn moves these enterprises to neighboring areas, so that the resource factors are reconfigured.

Discussions

Empirical findings

This study found that ERTP can significantly improve urban TFEE, which is consistent with existing conclusions about the positive performance of environmental regulation (Gu et al., 2022), but also presents new expansion points Firstly, compared with traditional research methods, this paper introduces satellite night light data and non-radial Super SBM model when measuring TFEE, which improves the robustness and accuracy of the measurement. Secondly, this article found that ERTP has a more significant promoting effect on TFEE in coastal cities, high-level cities, and resource-based cities, indicating significant differences in policy effects in spatial location, economic structure, and other dimensions. This finding enriches the discussion of policy regional adaptability in existing research. Thirdly, this article confirms the negative spatial spillover effect of ERTP through spatial econometric models, emphasizing the practical basis of the “pollution paradise hypothesis” in the implementation of environmental policies in China. However, the “pollution halo effect” has not yet formed a widely dominant position, providing new empirical evidence for understanding the cross regional externalities of environmental regulation.

Management insights

This article provides a scientific and effective basis for governments to promote ERTP in the future. Firstly, ERTP can significantly enhance TFEE in policy implementation areas, thus having significant economic and environmental benefits. Therefore, the government should gradually promote ERTP nationwide and implement regional and phased promotion strategies based on regional energy infrastructure, industrial structure, and governance capabilities. Secondly, green technology innovation and industrial structure upgrading are the key paths for ERTP to enhance TFEE. Therefore, the government can increase incentives and subsidies for green technology research and development, guide factor capital to invest in low-energy consumption and high value-added industries, in order to fully unleash technological and structural dividends. Thirdly, ERTP inhibited the increase of TFEE in neighboring areas. Therefore, the government should attach great importance to the spatial spillover effects of policies, coordinate environmental governance mechanisms between regions, and avoid the formation of new “regulatory depressions”.

Limitations

This article has several limitations. Due to the short implementation time of ERTP in China and the limited number of pilot cities, the data in this study is limited, so we are unable to test the long-term effectiveness of ERTP. Due to the lack of data, this study only examines the role of ERTP on TFEE from industrial structure and green technology innovation. Due to the limitations of indicators, this article only verifies the role of ERTP in promoting the GTI capabilities from the perspective of green invention applications.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

Based on the panel data of 280 prefecture-level cities in China from 2010 to 2020, this paper empirically tests the impact of ERTP on TFEE. The results show that ERTP can effectively improve TFEE in the implementation areas. After endogenous treatment and robustness tests, this conclusion is still valid. ERTP has a stronger effect on the TFEE of cities with better location advantages, higher urban levels and resource-based cities. Industrial structure upgrading and the improvement of green innovation capabilities are important transmission channels for ERTP to improve TFEE. ERTP has a significant industrial transfer effect, and there is a negative spatial spillover effect on the TFEE of neighboring non-pilot areas. These conclusions provide important empirical value for the promotion of ERTP and the improvement of TFEE.

The central government should implement differentiated management tailored to local conditions to enhance the adaptability of ERTP. The central government should grant local autonomy and allow them to make differentiated adjustments in initial quota allocation, trading mechanism details, and performance methods based on their own resource endowments, industrial structure, fiscal capacity, and environmental carrying capacity. At the same time, a policy evaluation and feedback system should be established to regularly scientifically evaluate and calibrate the effectiveness of policies, ensuring that differentiated management continues to be accurately adapted to local realities. We need to establish a long-term mechanism for green incentives. A special fund for green technology innovation can be established to guide social capital to focus on key areas such as energy conservation and emission reduction, clean energy substitution, and industrial green transformation. The government should make full use of tax and financial tools, expand the scope of green credit and green bonds, and provide preferential policies such as income tax deduction and accelerated depreciation for enterprises that purchase and apply green technologies and carry out green transformation, in order to stimulate the endogenous driving force of enterprise green transformation. Enterprises need to accelerate industrial upgrading and unleash the ‘structural dividend’. By raising the entry threshold and energy efficiency standards for high energy consuming industries, increasing efforts to eliminate outdated production capacity, and optimizing the industrial structure from the source. At the same time, it is necessary to establish an inter regional green industry undertaking mechanism, guide the green gradient transfer of industries, and avoid the disorderly relocation of polluting industries. We should combine the comparative advantages of various regions, vigorously develop green high value-added industries such as new energy and intelligent manufacturing, cultivate green emerging industry clusters, and inject sustainable “green new momentum” into economic development. A regional collaborative governance mechanism should be established to effectively address the negative spatial spillover of ERTP. By establishing a cross regional ecological environment collaborative governance information platform, we will promote information sharing, policy coordination, and joint supervision between pilot and non-pilot cities in areas such as environmental monitoring data, enterprise pollution discharge information, and regulatory enforcement standards. This will form a rigid constraint for cross regional joint prevention and control, and curb the occurrence of “pollution transfer” from the source.

Data availability

Data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Amaral S, Câmara G, Monteiro AMV, Quintanilha JA, Elvidge CD (2005) Estimating population and energy consumption in Brazilian Amazonia using DMSP night-time satellite data. Comput Environ Urban Syst 29(2):179–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2003.09.004

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (2001) Instrumental variables and the search for identification: from supply and demand to natural experiments. J Econ Perspect 15(4):69–85. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.4.69

Bennett MM, Smith LC (2017) Advances in using multitemporal night-time lights satellite imagery to detect, estimate, and monitor socioeconomic dynamics. Remote Sens Environ 192:176–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.01.005

Borozan D (2018) Technical and total factor energy efficiency of European regions: a two-stage approach. Energy 152:521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.03.159

Che S, Wang J (2022) Policy effectiveness of market-oriented energy reform: experience from China energy-consumption permit trading scheme. Energy 261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.125354

Chen C, Huang J, Chang H, Lei H (2019) The effects of indigenous R&D activities on China’s energy intensity: a regional perspective. Sci Total Environ 689:1066–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.369

Chen L, Wang K (2022) The spatial spillover effect of low-carbon city pilot scheme on green efficiency in China’s cities: evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Energy Econ 110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106018

Chen Y, Ma Y (2021) Does green investment improve energy firm performance? Energy Policy 153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112252

Chen Z, Kahn ME, Liu Y, Wang Z (2018) The consequences of spatially differentiated water pollution regulation in China. J Environ Econ Manag 88:468–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2018.01.010

Chen Z, Song P, Wang B (2021) Carbon emissions trading scheme, energy efficiency and rebound effect – evidence from China’s provincial data. Energy Policy 157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112507

Cui H, Cao Y (2023) How can market-oriented environmental regulation improve urban energy efficiency? Evidence from quasi-experiment in China’s SO2 trading emissions system. Energy 278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127660

Du G, Yu M, Sun C, Han Z (2021) Green innovation effect of emission trading policy on pilot areas and neighboring areas: an analysis based on the spatial econometric model. Energy Policy 156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112431

Du K, Cheng Y, Yao X (2021) Environmental regulation, green technology innovation, and industrial structure upgrading: the road to the green transformation of Chinese cities. Energy Econ 98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105247

Elvidge CD, Baugh KE, Kihn EA, Kroehl HW, Davis ER, Davis CW (2010) Relation between satellite observed visible-near infrared emissions, population, economic activity and electric power consumption. Int J Remote Sens 18(6):1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/014311697218485

Färe R, Grosskopf S, Norris M, Zhang Z (1994) Productivity growth, technical progress, and efficiency change in industrialized Countries. Am Econ Rev 84(1):66–83

Gu G, Zheng H, Tong L, Dai Y (2022) Does carbon financial market as an environmental regulation policy tool promote regional energy conservation and emission reduction? Empirical evidence from China. Energy Policy 163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112826

Guo Q.-t., Dong Y, Feng B, Zhang H (2023) Can green finance development promote total-factor energy efficiency? Empirical evidence from China based on a spatial Durbin model. Energy Policy 177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113523

Guo R, Yuan Y (2020) Different types of environmental regulations and heterogeneous influence on energy efficiency in the industrial sector: evidence from Chinese provincial data. Energy Policy 145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111747

Han Y, Zhang F, Huang L, Peng K, Wang X (2021) Does industrial upgrading promote eco-efficiency? ─A panel space estimation based on Chinese evidence. Energy Policy 154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112286

Hancevic PI (2016) Environmental regulation and productivity: the case of electricity generation under the CAAA-1990. Energy Econ 60:131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2016.09.022

Hong Q, Cui L, Hong P (2022) The impact of carbon emissions trading on energy efficiency: evidence from quasi-experiment in China’s carbon emissions trading pilot. Energy Econ 110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106025

Hong X, Ning M, Chen Q, Shi C, Wang N (2024) How does command-and-control environmental regulation impact firm value? A study based on ESG perspective. Environ Dev Sustain 27(5):11477–11508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-04366-8

Honma S, Hu J-L (2014) A panel data parametric frontier technique for measuring total-factor energy efficiency: an application to Japanese regions. Energy 78:732–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.10.066

Hu J, Pan X, Huang Q (2020) Quantity or quality? The impacts of environmental regulation on firms’ innovation–Quasi-natural experiment based on China’s carbon emissions trading pilot. Technol Forecasting Soc Change 158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120122

Kong Y, Feng C, Yang J (2020) How does China manage its energy market? A perspective of policy evolution. Energy Policy 147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111898

Li J, Huang J, Li B (2023) Do command‐and‐control environmental regulations realize the win‐win of “pollution reduction” and “efficiency improvement” for enterprises? Evidence from China. Sustain Dev 32(4):3271–3292. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2842

Li J, Lin B (2017) Ecological total-factor energy efficiency of China’s heavy and light industries: which performs better? Renew Sustain Energy Rev 72:83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.044

Li J, Lin B (2019) The sustainability of remarkable growth in emerging economies. Resour Conserv Recycling 145:349–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.01.036

Li Z, Wang J (2022) Spatial spillover effect of carbon emission trading on carbon emission reduction: empirical data from pilot regions in China. Energy 251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.123906

Liu X, Sun T, Feng Q (2020) Dynamic spatial spillover effect of urbanization on environmental pollution in China considering the inertia characteristics of environmental pollution. Sustain Cities Soc 53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101903

Lu J, Li H (2024) Can digital technology innovation promote total factor energy efficiency? Firm-level evidence from China. Energy 293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.130682

Mulder P, de Groot HLF (2012) Structural change and convergence of energy intensity across OECD countries, 1970–2005. Energy Econ 34:1910–1921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2012.07.023

Nasreen S, Anwar S (2014) Causal relationship between trade openness, economic growth and energy consumption: a panel data analysis of Asian countries. Energy Policy 69:82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.02.009

Nunn N, Qian N (2014) US Food Aid and Civil Conflict. Am Econ Rev 104:1630–1666. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.6.1630

Pan Y, Dong F (2022) Design of energy use rights trading policy from the perspective of energy vulnerability. Energy Policy 160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112668

Porter ME, Linde CVD (1995) Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J Econ Perspect 9:97–118. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Shahbaz M, Song M, Ahmad S, Vo XV (2022) Does economic growth stimulate energy consumption? The role of human capital and R&D expenditures in China. Energy Econ 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105662

Song M, Zheng H, Shen Z (2023) Whether the carbon emissions trading system improves energy efficiency – Empirical testing based on China’s provincial panel data. Energy 275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127465

Su H, Liang B (2021) The impact of regional market integration and economic opening up on environmental total factor energy productivity in Chinese provinces. Energy Policy 148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111943

Sun H, Edziah BK, Sun C, Kporsu AK (2019) Institutional quality, green innovation and energy efficiency. Energy Policy 135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111002

Tzeng C-H (2014) A review of contemporary innovation literature: a Schumpeterian perspective. Innovation 11:373–394. https://doi.org/10.5172/impp.11.3.373

Wang H, Chen Z, Wu X, Nie X (2019) Can a carbon trading system promote the transformation of a low-carbon economy under the framework of the porter hypothesis? —Empirical analysis based on the PSM-DID method. Energy Policy 129:930–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.03.007

Wang H, Zhou P, Zhou DQ (2013) Scenario-based energy efficiency and productivity in China: a non-radial directional distance function analysis. Energy Econ 40:795–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2013.09.030

Wang K, Su X, Wang S (2023) How does the energy-consuming rights trading policy affect China’s carbon emission intensity? Energy 276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127579

Wang L, Wu Q, Luo D (2020) Market barriers, administrative approval and firms’ markup. China Ind Econ 6:100–117

Wang Y, Deng X, Zhang H, Liu Y, Yue T, Liu G (2022) Energy endowment, environmental regulation, and energy efficiency: evidence from China. Techno Forecast Soc Change, 177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121528

Wang Y, Hang Y, Wang Q (2022) Joint or separate? An economic-environmental comparison of energy-consuming and carbon emissions permits trading in China. Energy Econ 109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105949

Wu J, Niu Y, Peng J, Wang Z, Huang X (2014) Research on energy consumption dynamic among prefecture-level cities in China based on DMSP/OLS Nighttime Light. Geogr Res 33(4):625–634

Wu R, Lin B (2022) Environmental regulation and its influence on energy-environmental performance: evidence on the Porter Hypothesis from China’s iron and steel industry. Resour Conserv Recycl 176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105954

Wurlod J-D, Noailly J (2018) The impact of green innovation on energy intensity: an empirical analysis for 14 industrial sectors in OECD countries. Energy Econ 71:47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2017.12.012

Xie R-H, Yuan Y-J, Huang J-J (2017) Different types of environmental regulations and heterogeneous influence on “green” productivity: evidence from China. Ecol Econ 132:104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.10.019

Xu M, Tan R, He X (2022) How does economic agglomeration affect energy efficiency in China? Evidence from endogenous stochastic frontier approach. Energy Econ 108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105901

Xu R-Y, Wang K-L, Miao Z (2024) The impact of digital technology innovation on green total-factor energy efficiency in China: Does economic development matter? Energy Policy 194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114342

Yang L, Li Y, Liu H (2021) Did carbon trade improve green production performance? Evidence from China. Energy Econ 96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105185

Zhang X-P, Cheng X-M, Yuan J-H, Gao X-J (2011) Total-factor energy efficiency in developing countries. Energy Policy 39(2):644–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.10.037

Zhang Y, Wei J, Gao Q, Shi X, Zhou D (2022) Coordination between the energy-consumption permit trading scheme and carbon emissions trading: evidence from China. Energy Econ 116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106433

Zhao W, Zhang J, Li R, Zha R (2021) A transaction case analysis of the development of generation rights trading and existing shortages in China. Energy Policy 149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.112045

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Research Project (25NDJC106YBMS), as well as by the National Social Science Foundation of China (2025CJY085) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42271295).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xilu Qiu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Visualization. Xinyi Jin: Methodology, Formal analysis. Shuiling Huang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Henglang Xie: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Wei Zhao: Formal analysis, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The authors declare consent for publication.

Ethical approval

This research is based exclusively on publicly available, anonymized secondary data and does not involve any direct interaction with human participants. Consequently, the study is exempt from ethical review approval, and no informed consent was required.

Informed consent

This study does not contain studies with human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, X., Jin, X., Huang, S. et al. Market-incentive environmental regulation and total factor energy efficiency: evidence from China’s energy-consuming right trading pilot. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1926 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06199-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06199-4