Abstract

Chinese cities have experienced rapid expansion in recent years, resulting in the emergence of hybrid neighborhoods characterized by buildings of varying ages, functions, and resident demographics. The distinctive environmental features hold significant research value for understanding their impact on residents’ perceptions of safety. However, research on the security of such neighborhoods remains limited. Q-methodology combines quantitative and qualitative research methods and is suitable for the study of hybrid blocks with complex factors affecting residents’ safety assessment. Three typical hybrid blocks were selected for the experiment. The findings point to six key environmental characteristics affecting residents’ sense of security within the scope of the study. Additionally, different social groups and living environments shape distinct perceptions and standards of security. This work contributes to the study of residential safety under hybrid blocks in China, enriching the existing crime prevention theory and improving its applicability and effectiveness. It can also help urban planners and policymakers reduce the tendency to overemphasize complex external environmental factors and provide a valuable reference to residential safety awareness in hybrid blocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research background

In recent decades, China’s economic, political, and cultural development, driven by the deepening process of modernization (Wu and Niu, 2019; Hui et al., 2021), has attracted a large influx of migrants to urban areas (Yang et al., 2023b), resulting in rapid urban expansion(Wang et al., 2021). However, due to the lack of systematic planning, design, and management mechanisms(Yang et al., 2023a; Chen et al., 2016), many cities’ older urban districts have evolved into a patchwork of industrial plants, courtyards, old residential buildings, and newly developed residential areas(Fang et al., 2021). These neighborhoods, referred to as “hybrid blocks” (Pili et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2024; Yue et al., 2017), frequently encounter issues such as a lack of spatial order and inefficient land use (Salamagy et al., 2023; Mouratidis and Poortinga, 2020; Cai et al., 2022). Consequently, their transformation and development require renewal efforts in terms of material infrastructure, functionality, and environmental quality. Additionally, the social and structural challenges they face pose significant difficulties for their regeneration (Cai et al., 2022), which is different from the “urban renewal” faced by London, Paris and so on.

Despite these challenges, hybrid blocks are often overlooked, as they are typically not designated as historical or cultural preservation zones (Salamagy et al., 2023). As a result, they are frequently earmarked for demolition or neglect, with their architectural value underappreciated and their historical significance largely ignored. This disregard fails to recognize the site’s historical accumulation and internal logic. Furthermore, there is a common tendency to equate spatial complexity with disorder, which obscures the hybrid and dynamic urban spaces that have emerged over time through layers of change in population, use, and structure (Mouratidis and Poortinga, 2020; Cai et al., 2022). These evolving spaces document the gradual transformations of the urban fabric, providing a unique record of historical shifts in social, economic, and functional aspects, which is the unique value of hybrid blocks and the significance of their existence. At the same time, urban design or various kinds of transformation are often aimed at urban streets and surface interfaces, but the internal organization and connotation of blocks are often ignored(Cai et al., 2022).

Such constantly changing urban spaces are not only the foundation of urban vitality but also the intrinsic driving force behind urban renewal(Chen et al., 2016; Pazhuhan et al., 2020; Bianconi et al., 2018). Therefore, it is essential to recognize the specificality of the environmental characteristics of hybrid blocks, which is of great value for understanding the sense of security of urban residents (Gan et al., 2021; Mihinjac and Saville, 2019; Bal et al., 2018; Kark and Carmeli, 2009; Douvlou et al., 2008). Beijing, as a city that has formed the typical characteristics of hybrid blocks, is typically representative in exploring this issue.

Meanwhile, there is increasing discourse surrounding the geography of crime and crime prevention, yet objective criminal behavior does not always correlate with subjective perceptions of security (Choi et al., 2023; Di Marino et al., 2023; Wo et al., 2024). These understandings can contribute to enriching existing crime prevention theories, such as Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED)(Mihinjac and Saville, 2019), thereby enhancing its applicability and effectiveness in the Chinese context. It can also be an important reference for the future work of urban designers and researchers concerned about residential security.

Research scope: definition and scope of security

Residential security is the outcome of residents’ perceptions and evaluations of urban social order(Fuller and Moore, 2017; Fisher and Piracha, 2012; Sakip, 2019). The imperative nature of individuals’ demand for a sense of safety is underscored by Abraham Maslow’s Need-hierarchy theory (Fig. 1), wherein the significance of safety ranks second only to the physiological needs essential for survival, such as food, water, and air (Maslow, 1943). In 1992, Douglas posed the question of “how safety is safe enough” (Beilharz, 1998), suggesting that safety, to a certain extent, transitions from describing an objective societal condition to assessing a subjective “sense of safety.” Consequently, the study of perceived safety emerges as a novel focal point within safety research, incorporating an endogenous perspective(Hui et al., 2021; Bianconi et al., 2018; Abdullah et al., 2011).

Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs model (Li et al., 2021).

The sense of security among urban residents is an expansive and multifaceted topic, encompassing aspects such as disaster preparedness, social order, and the supply of safe food (Cai et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2016; Minnery and Lim, 2005). Consequently, it is imperative to delimit the research scope. In this context, the discussion within this paper specifically pertains to the sense of security corresponding to the social order within urban areas. In this study, social order is perceived both as a “condition” and a “problem.”

When understanding social order as a “condition,” the assessment of good or poor social order essentially refers to the state of social order and security, constituting the perceptual and cognitive objects of individuals, i.e., the subject of the “sense of security.” On the other hand, when social order is equated with a “security problem,” it becomes a matter that necessitates societal resolution or serves as an object of societal order management. Embracing both semantic nuances, this paper focuses on security in a broad sense, encompassing criminal activities in the sense of criminal cases as well as deviant behaviors in the context of security incidents(Tien et al., 2021).

In alignment with these perspectives, the examination of residents’ sense of security in this study unfolds along two dimensions: the fear of criminal activities and attitudes towards and evaluations of societal disorder. This study is grounded in residents’ perceptions of social order, specifically focusing on the sense of defensive security (including physical safety and perceived psychological security), to investigate the impact of the built environment in hybrid blocks on residents’ sense of residential security.

Research theory: crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED)

In 1961, Jane Jacobs’ work, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” argued that the diversity and vitality of American cities were being undermined. She introduced the concept of “eyes on the street” and posited that traditional city blocks possess a self-defense mechanism through the concept of “eyes on the street.” This mechanism is derived from familiarity among residents, mutual support among neighbors, and continuous real-time monitoring during different periods (Jacobs, 1961). Therefore, the function of “eyes on the street” constitutes a safety feature derived from the streets themselves (Kuster et al., 2017).

Ray Jeffery first proposed the Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) theory in his work “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design,” presenting a multidisciplinary approach to spatial security design that integrates psychology, social behavior, and architectural design(Jeffery, 1977). Newman’s “Defensible Space” theory, primarily expounded from an architectural perspective, constitutes a discourse on crime prevention measures. The core concept of Newman’s theory is “defensible space”(Newman, 1973). Since 2000, scholars in China and East Asia have gradually attached importance to linking residential crime prevention and control with “environmental design” and “environmental elements”. They investigated the impact of environmental design on crime prevention (Chen et al., 2016). At present, the theory of crime prevention has been relatively perfect, but there are few researches on the urban historical space from the special perspective of “hybrid blocks”(Di Marino et al., 2023, Wen et al., 2024). Moreover, because such neighborhoods are often accompanied by local characteristics and special historical period values, the existing crime prevention theory is difficult to use directly (Table 1, Table 2). This study aims to provide some instructive results for the above content(Chen et al., 2016).

Tables 1 and 2 show that: there are more and more studies on the geographical location and prevention of crimes, and people have begun to pay more attention to small-scale living spaces, such as alleys and communities (Di Marino et al., 2023; Wo et al., 2024; Wo and Kim, 2022). However, objective criminal behavior is not always related to people’s subjective perception of safety, and there are few studies on hybrid blocks. Meanwhile, China’s unique community models, such as informal surveillance mechanisms and gated communities(Choi et al., 2023), exhibit strong indigenous characteristics. This renders the crime prevention characteristics of urban governance as a “fusion of informal surveillance and technological monitoring,” potentially resulting in the phenomenon where gated communities enhance physical security while exacerbating residents’ anxiety regarding perceived safety (Wu and Tan, 2023). The targeted research is of great value.

Therefore, the main research questions that this study focuses on are: What are the environmental characteristics that affect residential security in hybrid blocks? As a special block type, what are the different factors affecting the environmental characteristics of its residential safety and the existing classical theories? What are the differences in ordering? The hypothesis is: the environmental characteristics affecting the safety of hybrid blocks are not much different from the existing characteristics of classical theories, but the dominant factors are different, which also reflects the particularity and value of hybrid blocks. This study needs to focus on exploring the similarities and differences among them.

Materials and methods

Research design

The Q-methodology is a systematic method that originated in the field of psychology (Zhuang and Ye, 2023) but has been widely used in different fields in recent years. The method is used to systematically investigate interviewees’ perspectives, opinions or preferences towards a given subject, and the result depicts a diversity of perspectives, opinions or preferences held by interviewees (Brown, 1996; Minnery and Lim, 2005). The Q-methodology focuses on identifying diverse views or preferences rather than generalizing findings from sample respondents to a larger population(Mouratidis and Poortinga, 2020; Rost, 2021). Other common quantitative research methods, such as R methodology or spatial modeling, seriously ignore subjects’ subjective awareness, and the sample average cannot represent the situation of most people. This research should pay more attention to “individual subjectivity”(Milcu et al., 2014). In addition, the Q-methodology can distinguish and interpret different opinions on a certain subject in a group of subjects, which is difficult to do with traditional questionnaire methods (Mouratidis and Poortinga, 2020; Milcu et al., 2014; Li et al., 2022). Although group interviews and focus groups can provide information on possible different perspectives, they lack quantitative means. Moreover, some methods only review the items by experts, and often ignore the real ideas and needs of the research objects, thus making the research objects and research content disconnected. Through the Q-methodology, the same subject can be classified in different instructions to examine the differences between the subjects from different angles and starting points (Brown, 1996; Chen, 2016).

For hybrid blocks, the sense of residential security is a rather subjective judgment. There are many factors that affect the inhabitants’ evaluation of the sense of security, resulting in obvious differences in the resident’s individual evaluation standards and evaluation results, which cannot be measured by quantitative means (Casteel and Peek-Asa, 2000). Therefore, both the objective conditions of the built environment and the social environment affect residents’ experience. Q interviews could be conducted with residents through Q-methodology to analyze the motivation of respondents’ subjective judgment on residential safety based on the environmental characteristics of hybrid blocks. Based on the advantages of Q-methodology and the purpose of this study, we adopt Q-methodology as our research method.

In an empirical setting, applying the method involves several key steps (Fig. 2). These involve: (a) the definition of a series of statements as prompts that represent the subject of the study (Q-set); (b) selection of interviewees (P-set); (c) administering the ranking of Q-sets by the different interviewees(Q-sorting); and (d) factor analysis of the Q-sorts(Brown, 1996; Milcu et al., 2014; Chen, 2016).

The Q sample

Firstly, the definition of the statements set is provided. Conceptually, the term “statements” refers to the collection of all opinions and issues related to our research topic. In practical terms, defining the set of opinions involves gathering relevant opinions and statements on the topic, typically through interviews or literature reviews to compile the opinions and statements forming the discourse. In the context of this study, it specifically denotes the academic discourse regarding factors influencing the sense of residential security. This research compiles and establishes its Q statements from the literature on residential security experience (Table 1, Table 2).

Following the definition of the opinions set, the next step is to select the most appropriate and representative statements to form the Q sample. This study constructs a factor design based on literature regarding the manifestation of residential security (Table 3).

Attempting to build an opinion set on the impact of hybrid blocks on the sense of security in residential areas across two dimensions – social elements and environmental design elements – the study proceeds to select the Q statements required for the Q-methodology research. The first dimension, social elements affecting residential security, includes two influencing factors: “interpersonal relationships” and “surrounding building functions”. The second dimension, environmental design elements as the second factor influencing residential security, comprises three influencing factors: “urban space,” “physical facilities,” and “landscape facilities.” “Urban space” includes two sub-factors: “public interaction space” and “road space.” “Physical facilities” consist of four sub-factors: “building,” “lighting facilities,” “public safety facilities,” and “access control.” Lastly, “landscape facilities” encompass two sub-factors: “surrounding environment” and “green spaces”.

Based on the above factor design, the study incorporates two dimensions of residential security and their five primary factors, resulting in a total of six combinations (A × B = 2 × 3 = 6). To balance the breadth of the Q sample and avoid an excessively large number of Q sample statements, the study follows the standard proposed by Van Exel (40–50 statements are advisable) (Dieteren et al., 2023). Considering the coverage of sub-factors, the study selects 4-16 statements from the discourse for each combination instead of distributing them evenly. This ensures that the total number of Q sample statements for this study is 46. In this way, 46 Q statements were selected (Table 7, Statement).

The P set

In Q-methodology, the P set refers to the individuals selected by the researcher for Q sorting, aimed at enhancing our understanding of “subjective opinions on the research topic.” Q-methodology does not employ random sampling to select participants. Instead, it purposefully selects a group of participants who are theoretically or experientially believed to be familiar with the research topic and possess insights or specific perspectives. In this study, participants are strategically selected based on two criteria. Firstly, they must reside in any of the three hybrid blocks under investigation and be familiar with the surrounding context. Secondly, they must be residents who prioritize the sense of residential security. All participants are informed in advance that their involvement in this study is entirely voluntary and anonymous. The data of all participants remain anonymous and are exclusively used for this research.

The Q sorting

In this study, Q-sorting analysis was conducted using the KADE (Ken-Q Analysis Desktop Edition) software. Ken-Q is a platform developed for online Q-sorting analysis. Prior to commencing the Q-sorting procedure, participants were acquainted with the study and its objectives. Subsequently, participants were instructed to perform a pre-sorting task. This pre-sorting involved categorizing the 46 statements into “extremely important,” “fundamentally unimportant,” and “neutral” categories related to the perceived significance of these statements to residential security. Although pre-sorting data was not recorded, this phase aimed to provide participants with an overview of all Q-sort statements before proceeding to the main sorting task. This is a common step in the Q-methodology designed to enhance the quality of Q-sorting outcomes.

Once the Q samples and P set have been confirmed, the subsequent step involves inviting respondents to conduct Q sorting. Firstly, it is imperative to establish the Q distribution. Generally, the “quasi-normal distribution” is commonly employed for this purpose. The determination of the Q distribution is subjective and lacks rigid rules to be adhered to; however, normal distribution and quasi-normal distribution offer statistical advantages.

Given that this study’s Q sample comprises 46 Q statements, the range for deciding the Q distribution is set from +4 to −4 (Fig. 3). The Q distribution is specified as 2-4-6-7-8-7-6-4-2, indicating that under +4, 2 statements are placed, under +3, 4 statements are placed, under +2, 6 statements are placed, and so forth.

Following informed consent, participants were provided with Q-statements printed on uniformly sized cards and a reference sheet depicting the initial sorting grid configuration (Fig. 3, Q-sort). Participants were instructed to arrange the statements spatially according to their subjective attitudes and perceived intensity of agreement/disagreement. To ensure procedural reliability, researchers accompanied participants throughout the task and provided immediate clarification when ambiguities in statement interpretation arose. Each Q-sorting session was strictly controlled within a 20–30 min timeframe. At the same time, in order to avoid mutual interference, the Q-sorting process was completed by all respondents individually.

Background information on respondents and the considerations they make while conducting Q sorting are typically addressed by posing questions on the recording sheet, especially when arranging statements based on the most agreement or disagreement. The questions commonly include: (1) Why did you place the statement that you most agree with under +5? (2) Why did you place the statement that you most disagree with under -5? (3) What was the primary consideration for you during the Q sorting process? The primary purpose of these questions is to elicit information about the considerations made by respondents during Q sorting. This information proves crucial in facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the thoughts underlying different opinion categories during the interpretation phase.

Research process

The choice of spatial scale in this study is a critical consideration in understanding the impact of the built environment on residents’ sense of security in hybrid blocks.

Hybrid blocks

Hybrid blocks refer to urban plots located within the block and not separated by urban roads, in which the activities of different groups of people, buildings of different ages, types and styles are concentrated in an urban plot and collide and influence each other to form the unique nature of the plot (Holl, 2014; Igualada, 2018). It is related to but not limited to “informal space” and “mixed residential area” (Igualada, 2018). This work selects three eligible hybrid blocks in Beijing, China as the research object, named Caoyuan Hutong, Xidan-Horizontal second road community and Temple of Heaven West community (Figs. 4–7) (Xu and Zhao, 2021). The research plots, which were the important development and construction area of Beijing from the late Qing Dynasty to the early period of New China, are located in the Second Ring Road of Beijing(Ruoshi et al., 2024). They have the typical characteristics of hybrid blocks, and respectively represent the three main modes of hybrid blocks in current China (Chen and Wu, 2021): (1) Hybrid blocks in the historical era of architecture; (2) Hybrid blocks with commercial, residential and other functions; (3) The highly complex hybrid layout of formal settlements and informal settlements.

Caoyuan Hutong

The Caoyuan Hutong exemplifies a hybrid block typical of the built environment era, featuring an architectural ensemble from various historical periods. Additionally, buildings of differing scales create a disjointed urban fabric, limiting efficient space use and failing to meet residents’ demand for quality public living environments. Historically constrained, the transportation network in Caoyuan Hutong mainly consists of narrow one-way alleys. While this limits road connectivity, it also hampers daily commuting efficiency. The chaotic functional layouts further complicate everyday life, reducing both neighborhood vitality and livability.

Xidan-Horizontal second road community

The Xidan-Horizontal second road community is a hybrid block that combines commercial and residential functions. It features vibrant commerce and high foot traffic, attracting diverse individuals and creating a complex social ecosystem. However, this diversity can lead to conflicts between transient visitors and local residents. The dense pedestrian activity complicates area management and requires advanced residential security strategies in this hybrid block. Additionally, the urban interface shows some discontinuity, detracting from the neighborhood’s esthetic coherence. Public spaces face issues related to limited variety and functionality, hindering their ability to meet residents’ diverse activity needs. This limitation further restricts development potential.

Temple of Heaven West community

The hybrid layout of formal residential areas and informal settlements within the Temple of Heaven West community creates a highly complex regional environment, significantly impacting the residential security. The transportation network in this block suffers from limited accessibility and a dense arrangement of dead-end roads, which severely restricts internal traffic circulation efficiency and hinders seamless connections with the surrounding environment. Moreover, the lack of comprehensive public space system and low community vitality fail to adequately meet the daily activity needs of its residents.

Since actual crime data in neighborhoods are not permitted to be disclosed in the study area, the researchers visited the management personnel of each community to identify the approximate locations prone to crime in recent years and created a security risk zone map (Fig. 7) of high, medium, and low crime probability based on descriptions from professionals. In this way, the basic information of the three hybrid blocks was obtained in detail.

Definition of respondent scope

Individuals residing in various age groups within the study area. People in general show the characteristics of diversity, their occupation, age, social status and so on have a large degree of difference (Marzbali et al., 2012a), as a research scope can better collect and analyze the impact of different groups on the security of urban built environment caused by various factors and judge (Brown, 1996; Rost, 2021; Marzbali et al., 2012a; Marzbali et al., 2012b).

Research ethics

There are human participants in this study, and the overall distribution characteristics of participants are consistent with the distribution characteristics of China’s Hybrid blocks(Zhuang and Ye, 2023; Zhang et al., 2020). The duration of this work spanned from September to November 2021, lasting for 3 months. Before participating in this research, each participant was informed of the purpose, basic research content, process, method and other basic information of this research, and also knew which of their information would be used in this paper. Meanwhile, we promise not to make specific correspondence between participants’ personal information and the research content. All subsequent data analyzes have been anonymized. The study does not involve any technological experiments with human or animal subjects, and there are no associated risks. It is classified as a project with a risk probability and level not exceeding the risk standards of ethical considerations in science and technology. Therefore, the ethics approval was granted by the relevant ethics committee (see “Ethics” statement part) and verbal consent was obtained from participants. At the same time, in order to ensure the accuracy and non-misunderstanding of the data needed for the research, all the questionnaires were written in Chinese (the first language of the place where the research was conducted), which was translated into English for easy understanding in the subsequent expressions of this research.

Analysis and interpretation

Through the above steps, a total of 22 valid data pieces were collected. Among them, there are 9 in Caoyuan Hutong, 7 in Xidan-Horizontal second road community and 6 in Temple of Heaven West community. Considering the common view of the Q method(Bertaux, 1981; Creswell and Poth, 2016; Watts and Stenner, 2012), the sample size of 22 participants in this study is in line with the standard and can reflect the population characteristics in this study area (Table 6).

After the necessary organization of the Q sorting data, it can be entered into KADE for factor analysis. Ken-Q offers two methods for factor analysis: Centroid factor analysis and Principal Components Analysis (PCA) (Li, 2015). This study has opted for the Principal Components Analysis method recommended, which is more effective for dimensionality reduction, as it focuses on maximizing variance explanation to efficiently extract a small number of principal components that capture multivariate variation patterns in participant-sorted data, while factor rotation enhances interpretability(Wold et al., 1987). In contrast, centroid factor analysis relies on factor model assumptions and exhibits lower efficiency in dimensionality reduction for complex subjective datasets(Wold et al., 1987; Lawley and Maxwell, 1962). This study employed factor analysis to cluster participants into distinct viewpoint groups (factors) based on similarities in their subjective rankings, followed by an analysis of intra-group differences in statement rankings to explain diversified subjective stances.

Initially, the software is employed to calculate the correlation matrix and eigenvalues of the matrix for the 22 samples. According to the Kaiser criterion, the decision on the number of factors to retain is based on eigenvalues greater than 1. The cumulative percentage of variance for the first six eigenvalues reached 60% (Fig. 8 and Table 4). It meets the basic requirements of Q analysis, indicating that these 6 factors have a certain representativeness of samples. Therefore, the first six factors should be retained and subjected to Varimax rotation to maximize variance.

The Critical Value formula: N is the number of statements in the Q sample, and 1.96 corresponds to the Z value at the 0.95 significance level. Given that this study utilizes 46 Q statements, the critical value is calculated as (1/√46) * 1.96 = 0.289. When the factor loading for a participant’s Q sorting under a particular factor exceeds or equals 0.289, that participant is classified under that specific factor category.

After the factor sequence behind the rotation axis is obtained, it is necessary to test the factor load of each interviewee, that is, whether the factor load of a certain interviewee ranked Q is significant, in order to classify them. A respondent is classified under a category factor when the number of factor loads in the Q ranking of a category factor is greater than or equal to the critical value (the critical value in this study is 0.289).

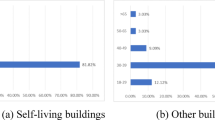

Through the above Q-methodology data analysis, this study extracts 6 factors affecting the security of residential security. Table 6 shows the background information of 22 respondents who participated in this study. Notably, residency registration in Beijing is important information that has not been paid attention to in previous related studies. Its significance lies in its rigid linkage to social welfare entitlements: non-local residents face systemic barriers to resource access due to policy restrictions, exacerbating material insecurity. Meanwhile, residency registration can lead to “institutional exclusion” at the psychological level, weakening the sense of belonging of migrant groups to urban security.

If an interviewee is classified into a certain factor type, “X” is added after the factor load. Twenty-two respondents fell into six categories. Among them, factor 1, factor 2 and factor 4 have 4 digits, factor 3 has 3 digits, factor 5 has 5 digits and factor 6 has 2 digits (Table 5).

We use different methods to explain and characterize these factors. We mainly consider the following points to explain, characterize and compare these factors. (1) We characterize each factor according to the nature of the factor load, i.e., the type of respondent with a significant load on a similar factor. Here, respondents loaded onto similar factors have similar preferences. (2) By looking at preference patterns involving residential security in the built environment as well as prioritized social factors and environmental design elements, we characterize each factor in terms of the overall configuration stated under each factor. (3) We take account of statement scores in characterizing each factor. Here, we use the weighted average of each statement to explain the highest and lowest priority of each factor. Thus, the statement with the highest ranking (i.e., +4, +3, +2) is considered the highest priority of the factors, while the statement with the lowest ranking (i.e., −2, −3, −4) is interpreted as the statement with the lowest priority of each factor.

Results

Results overview

Based on 46 q statements (Table 7), principal component analysis (PCA) (Li, 2015) produced six distinct sets of neighborhood security factors (F1-F6), which together explained 61% of the total ranking variance (Table 5) and captured the priorities of 22 stakeholders (N = 22). These six factors are respectively: Public Communication Space, movement of people near residential areas, relations between inhabitants, the closure of the interior, functionality and density of physical facilities, and outlying roads and surroundings. This indicates that the environmental characteristics influencing hybrid blocks are not significantly different from those of the existing classical theories, but the dominant factors are different. This also reflects the uniqueness and value of environmental characteristics in hybrid blocks. We will describe each of these six factors below and then compare the similarities and differences among these factors. Finally we will put forward the obstacles and opportunities to perceive the security of hybrid residential areas, so as to provide help and basis for the future planning and design of residential areas.

The influence of urban built environment on residential security

Factor 1: Public communication space

The first factor is defined as Public communication space, based on the statement with the highest weight and score among the stakeholders influencing the factor (hereinafter referred to as X, *) (X17, 19, 18, 5; p < 0.05; *20:+4, 42:+4, 8:−4, 3:−4; Table 5, Table 7, Fig. 8), there is a strong preference among stakeholders who load the factor. Statements under this factor are mostly under gating control. Therefore, for them, the public communication space in the hybrid blocks is the most important factor. For hybrid blocks, public communication spaces within sight provide a sense of security. Meanwhile, for closed hybrid blocks, better internal management and external control are key issues for them to enhance their sense of security.

Factor 2: Movement of people near residential areas

The second factor is defined as the Movement of people near residential areas, based on the more significant statements (#2, 10, 12, 6; p < 0.05, 34:+4, 21:+3, 36:−3, 33:−3; Table 5, Table 7, Fig. 8), there is a strong preference among residents to load the factor. Residents strongly value the social elements of the place where they live, especially the interpersonal relationships in the social elements. Familiar residents around and fixed food, police stations, etc. are the main part of their source of security. The floating population such as the tenants in the residential area is an important factor affecting their sense of security. The regular flow of people on working days makes them feel safe. An abnormal flow of people (increase or decrease) at other times will reduce residents’ sense of security. At the same time, the external monitoring effect brought by electronic devices also has an important help to enhance the sense of security. It can be seen that they have a great sense of security in the scope of visual monitoring (electronic eye, human eye).On the contrary, the increase and full coverage of lighting facilities did not contribute to a sense of security. Because this can cause discomfort to residents, they may find it too bright outside their windows at night.

Factor 3: Relations between inhabitants

The third factor is defined as Relations between inhabitants, and among the stakeholders influencing the factor, it is based on statements of high significance (#1, 4, 7; p < 0.05, 24, 33:+4, 12:−3, 8:−4; Table 5, Table 7, Fig. 8) shows that the stakeholders with this factor have a positive correlation to their sense of residential security as surrounding building functions and interpersonal relationships in the social factors, but there is no high agreement on the contents. For external means such as electronic surveillance, they believe that they do not bring enough security, because there are always unfocused surveillance blind spots that may breed crime. Compared with the influence of urban space on environmental factors, they pay more attention to the attributes of people in the surrounding activities. Familiar people bring security, but the diversity of people from different occupations and ages also makes respondents feel insecure because they believe that too different perspectives and opinions are more likely to lead to arguments, and even assaults and crimes. At this point, factors such as neighborhood trust and communication have a significant impact on a sense of safety. At the same time, some respondents believe that residents in old-built residential areas are mostly elderly, even if someone calls for help, it is difficult to help them, and the degree of support in the neighborhood also affects their sense of security in living. However, the landscape facilities in the living environment have little influence on the residential security in this view.

Factor 4: The closure of the interior

The fourth factor is defined as the closure of the interior, based on statements of high significance among the participants influencing the factor (#20, 8, 22, 11; p < 0.05, 40:+4, 37:+3, 28:−3, 17:−4; Table 5, Table 7, Fig. 8), the participants loading this factor did not reach a high degree of agreement on the positive correlation factors of their residential security. They focus on interpersonal relationships and peripheral functions in social elements, as well as road space in urban space. They focus on the necessity of road control elements in hybrid blocks and believe that unobstructed road is an important factor in effectively enhancing the security of residential areas. At the same time, whether the living space is connected to the outside is also their concern: architectural design choices (gated communities, or enclosed courtyards) contribute to enhancing residents’ sense of security. The crowding of semi-private spaces such as courtyards and front spaces, the loss of order in living spaces caused by unauthorized house expansion (too chaotic and crowded), and the congestion of traffic spaces caused by such incidents will reduce the safety of residential areas.

Factor 5: Functionality and density of physical facilities

The fifth factor is defined as Functionality and density of physical facilities, based on statements of high significance among the stakeholders influencing the factor (#15, 13, 3, 22, 9; p < 0.05, 27:+4, 31:+3, 43, 46:−3, 45:−4; Table 5, Table 7, Fig. 8), the stakeholders loading the factor have clear and consistent preferences. They all believe that physical facilities have a greater impact, especially the necessity of access control elements in the residence, which greatly affects the sense of personal security in the residence. The surrounding physical facilities will lead to the number of people and lead to different incidents. Positive ones such as school districts and shopping malls will bring security, while unimpeded alley distribution and bars and other facilities will increase the possibility of crime. At the same time, they are more consistent that the simple construction facilities will not affect their living safety, such as parking lots, parks, and communal areas. In addition, because of the spontaneous expansion of old residential areas, occupying roads, resulting in space congestion, and some dilapidated houses being idle and abandoned, it is likely to become a place for crime to breed.

Factor 6: Outlying roads and surroundings

The sixth factor is defined as Outlying roads and surroundings, and among the stakeholders that influence the factor, it is based on statements of high significance (#16, 14; p < 0.05, 12:+4, 24:−3; Table 5, Table 7, Fig. 8). The stakeholders who load this factor are mainly concerned with the road factor among the environmental design factors. Due to the lack of supporting infrastructure such as parking lots and parking buildings, vehicles are parked on the surrounding roads at will, which greatly affects the surrounding road space and causes security risks. The obstruction of road space and the blocking of vision make residents worry about the occurrence of criminal incidents and accidents. Therefore, this factor is related to accessibility to emergency services and areas prone to crime. At the same time, the diversity of nearby buildings and public facilities leads to the complexity of the identity sources of nearby people, reducing their sense of security. However, proximity is an important factor in improving the sense of security of such respondents. Therefore, the design of outlying roads and the functions of the surroundings around communities have an important impact on residential safety.

Consensus and distinguishing statements across the six factors

There is generally less consensus among the six factors (Table 8). Among them, people under Factor 1, Factor 2 and Factor 3 all pay attention to the part of interpersonal relationships (Table 7, Table 8). Both Factor 2 and Factor 4 pay attention to the mobility and diversity of people in the residential area, but the difference is that people under the influence of Factor 2 factor believe that mobile people and diverse occupational backgrounds will reduce the sense of security, while people under the influence of Factor 4 think that it will enhance the sense of security (Table 7, Table 8). This difference in sense of security may represent the attitude of hybrid blocks residents with or without household registration towards the movement of people. Both Factor 5 and Factor 6 focus on the impact of physical facilities, buildings and surrounding environmental factors, but Factor 5 focuses on the impact of these factors on the sense of security, while Factor 6 focuses on the road factors in the environment and the interference they cause to the road, thus affecting their perception and judgment of security(Table 7, Table 8 and Fig. 8).

Respondents under the influence of Factor 1 and Factor 6 also pay attention to the influence of roads (Table 8). However, the stakeholders under Factor 1 believe that open roads and open Spaces accessible to the line of sight are the main sources of security, while the respondents under Factor 6, on the basis of ensuring safety, emphasize that too open and extensive road or alley design may lead to criminal behavior because it facilitates the selection of crime locations and is relatively difficult to be caught (Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8). This difference may be caused by the difference in the average size of the living space, so an appropriate scale is necessary to ensure that most people feel safe.

Discussion

There are some problems in the process of adopting Q-methodology. In the investigation environment at that time, although we reasonably selected the streets with dense passenger flow, there were not quite a large number of people (more than 100) willing to accept the investigation and interview due to the influence of the surrounding environment. This may be because we choose to conduct research on the streets in order to experience the safety of the built environment for ourselves, or it may be influenced by other factors. Therefore, the number of survey data finally used in this paper is slightly small, which also leads to certain background inequalities in the composition of interviewees, such as gender, age, education level, etc., which will have some impact on the result. Nevertheless, the sample size available meets the basic sample size principle of the Q method (the sample size of no less than 15 (Bertaux, 1981, Xie and Chen, 2021) or between 20 and 30 (Creswell and Poth, 2016)) and is sufficient to provide a representative insight into the cognitive and emotional responses within the scope of this study.

Theories such as “Street Eye” and CPTED, which are proposed from foreign situations, are of great significance to understanding and studying the impact of the built environment on residential security in hybrid blocks in China, and also provide great help to the research thinking and research method design of this paper (Reppetto, 1976; Schneider, 2005). However, because it is based on the foreign environment at that time, it is also different from the current Chinese environment and the cognition of Chinese residents (Ewen et al., 2017), which is also reflected in the above analysis of the results in this paper. Specifically, the “eyes on the street” theory emphasizes familiarity among residents, mutual support among neighbors, and continuous real-time monitoring at different times (Jacobs, 1961). CPTED and Defensible Space Theory also emphasize the importance of public oversight (Newman, 1973; Johnson et al., 2014). This is consistent with Factor 2 and Factor 3 in our experiment, indicating that residents in hybrid blocks still care about these factors. But the Factor 1 (Public Communication Space) we mentioned is only mentioned in CPTED. At the same time, Factors 4–6 show a relatively special phenomenon of hybrid blocks, which also exist in other types of residential areas but do not have such distinctive characteristics, and it is the part that has not been paid attention to in previous theories. It is also the value of this study.

In recent years, the living environment in China has been closely related to the changes in social, economic and political systems. The planning and development of residential areas in China has gradually evolved from early neighborhood units and expanded neighborhoods into a complete development model of residential areas (Zhang et al., 2020). The market-oriented operation mechanism has endowed the planning of residential areas with new innovative vitality, and the environment and living quality of residential areas have been greatly improved. However, the planning and design of most residential areas in China are affected by the control of the market, and only pay attention to the appearance rather than the interior, and only talk about the garden rather than the interior performance. The involvement of different developers, real estate, and non-uniform development and urban renewal has resulted in specific requirements and special perspectives for residential security in hybrid blocks and old-built environments (Ewen et al., 2017).

In the previous analysis, in the built environment of hybrid blocks, most residents attach more importance to neighborhood relations. They have different perspectives on understanding and ranking reasons, but most of them agree that acquaintances and more fixed residents can bring greater security. At the same time, according to the analysis results, it can be seen that compared with the various parts of the environmental design elements, most of the residents in the real hybrid block pay attention to the social elements, especially the interpersonal elements. This is also the result of China’s unique national conditions and the long-term role of Chinese culture in people’s thinking. It may also be that residents who pay more attention to environmental design elements such as buildings, roads and physical facilities generally do not choose to live in the built environment of hybrid blocks for a long time. Although this has also influenced the result, it is also one of the significance of our study. The conclusions of this paper should also be taken into account in the design or research of residential area security.

Conclusions

Focusing on the environmental characteristics of hybrid blocks and examining their specific impact on security perception can enhance existing crime prevention theories, broaden their application contexts, and improve their effectiveness. In this context, the present study employs Q-methodology to explore the lived experiences and security perceptions of different respondents in hybrid neighborhoods. Based on this study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Consider the background diversity

First, individuals from diverse identity backgrounds exhibit varying levels of awareness regarding the environmental characteristics and security of hybrid neighborhoods. Therefore, future urban housing design, urban renewal, and the renovation of older residential areas should take this diversity into account to mitigate potential negative impacts stemming from conflicting factors. It’s important to consider diverse backgrounds in urban planning and policy-making. The variability in perceptions of security among different demographic groups suggests that policy measures should be tailored to meet the specific needs of these groups. One approach to addressing this challenge is to systematically plan and implement participatory reverse exchange activities, which can promote understanding of the diverse design and retrofitting needs of neighborhoods. These activities should foster opportunities for inclusive resident dialog, with particular attention to reconciling existing conflicts, such as prioritizing the use of smart spaces.

Focus on social factors

Second, in contemporary Chinese hybrid neighborhoods, the majority of residents place a strong emphasis on neighborly relations, recognizing that familiarity and long-term residents contribute to a heightened sense of security. Consequently, in future design and planning efforts, it is crucial not only to refine environmental design elements but also to focus on neighborly interactions, particularly interpersonal dynamics. Planners should consider the backgrounds and characteristics of current and potential future residents when devising targeted design strategies. For example, the use of targeted design for residential areas with similar backgrounds (employee residential areas, accommodation areas, etc.); For residential areas facing multiple groups, its elements should be enriched to meet a variety of needs and reserve space for micro-updating according to the actual relationship between residents in the later period. By doing so, the sense of security in these areas can be significantly improved, which represents a key contribution to this study. This point should also be taken into account when using the study’s conclusions for further residential safety research.

About mixed method

From a methodological perspective, this study converts respondents’ subjective experiences into objective data for analysis, which can help designers and planners reduce the tendency to overemphasize complex external environmental factors. However, participatory research interviews (Q methodology), while proportionately representative of respondents and indigenous people, may still be underrepresented due to the sample sizes. In the research problem of this study, because a typical residential area (hybrid blocks) has been limited, the population views in this context are valuable, and the conclusions can be extended to other urban areas with hybrid blocks characteristics. In the future, the Q methods of residential security research in hybrid blocks are likely to develop towards mixed-method approaches, such as GIS and crime data analysis. These methods will bring more sample data and analysis, which can solve the problem of the above Q method.

In conclusion, this study focuses on a kind of special neighborhoods that are often neglected in the past and reveals the characteristics of residents’ preference safety perception in hybrid blocks in China. This paper suggests that urban planners and policymakers should take into account the diversity of background characteristics of the population in future urban housing design, urban renewal and renovation of old residential areas in order to mitigate the possible negative impact of conflicts in safety perception. Relevant policies should be tailored to the specific needs of these groups. Meanwhile, attention should also be paid to the interaction among neighbors, especially the construction of interpersonal relationships. When formulating specific design strategies, planners should take into account the background and characteristics of current and potential future residents and conduct targeted designs. If possible, reserve space for future small-scale updates based on the actual relationships among residents. Furthermore, this study can also provide an effective reference for the block model, which is similar to the old cities that are undergoing urban renewal around the world. These conclusions are of greater value for regions like China that have undergone rapid urbanization.

Meanwhile, the data collected in this study have had a time interval, and new changes in environmental characteristics may have emerged, such as the intensified closure of hybrid blocks caused by the impact of COVID-19 in recent years. Such changes have gradually subsided over time, but they may cause new impacts in the future. Future research could incorporate objective crime data, explore cultural factors and variety, and use mixed methods (e.g., GIS, temporal analysis) to expand the scope and value of the conclusion.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to data being in use.

References

Abdullah A, Abd Razak N, Salleh MN, Sakip SR (2012) Validating crime prevention through environmental design using structural equation model. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 36:591–601

Bal W, Czalczynska-Podolska M (2018) The Role of Integration of Architecture and Landscape in Shaping Contemporary Urban Spaces. 3rd World Multidisciplinary Civil Engineering, Architecture, Urban Planning Symposium (WMCAUS), Prague, CZECH REPUBLIC

Beilharz P (1998) Reading Zygmunt Bauman: looking for clues. Thesis Eleven 54(1):25–36

Bertaux D (1981) Biography and society: the life history approach in the social sciences, vol 23. Sage London

Bianconi F, Clemente M, Filippucci M, Salvati L (2018) Re-sewing the urban periphery. A green strategy for Fontivegge district in Perugia. TeMA J Land Use Mobil Environ 11(1):107–118

Brown SR (1996) Q methodology and qualitative research. Qual Health Res 6(4):561–567

Cai Z, Guan C, Trinh A, Zhang B, Chen Z, Srinivasan S, Nielsen C (2022) Satisfactions on self-perceived health of urban residents in Chengdu, China: gender, age and the built environment. Sustainability 14(20):13389

Casteel C, Peek-Asa C (2000) Effectiveness of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) in reducing robberies. Am J Prev Med 18(4):99–115

Chen L (2016) Doing Q methodological research: theory, method and interpretation. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn 17(3):384–385

Chen MX, Liu WD, Lu DD (2016) Challenges and the way forward in China’s new-type urbanization. Land Use Policy 55:334–339

Chen Y, Wu M (2021) Hybridity, Isolation and Conflict in Urban Renewal: A Case Study of Chuanbanhutong in Beijing during Relocating Non-Capital Functions. UIA 2021 RIO: 27th World Congress of Architects. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Choi W, Na J, Lee S (2023) Evaluating Intelligent CPTED Systems to Support Crime Prevention Decision-Making in Municipal Control Centers. Appl Sci 14(15):6581. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156581

Creswell JW, Poth CN (2016) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage publications

Di Marino M, Tabrizi HA, Chavoshi SH, Sinitsyna A (2023) Hybrid cities and new working spaces—the case of Oslo. Prog Plan 170:100712

Dieteren CM, Patty NJ, Reckers-Droog VT, van Exel J (2023) Methodological choices in applications of Q methodology: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Humanit Open 7(1):100404

Douvlou E, Papathoma D, Turrell I (2008) (The Hidden City) Between the border and the vacuum: the impact of physical environment on aspects of social sustainability. 5th International Conference on Urban Regeneration and Sustainability (The Sustainable City), Skiathos Isl, GREECE

Ewen HH, Washington TR, Emerson KG, Carswell AT, Smith ML (2017) Variation in older adult characteristics by residence type and use of home- and community-based services. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(3):12

Fang CL, He SW, Wang L (2021) Spatial characterization of urban vitality and the association with various street network metrics from the multi-scalar perspective. Front Public Health 9:677910

Fisher D, Piracha A (2012) Crime prevention through environmental design: a case study of multi-agency collaboration in Sydney, Australia. Aust Plan 49(1):79–87

Fuller M, Moore R (2017) An analysis of Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Macat Library

Gan XY, Huang L, Wang HY, Mou YC, Wang D, Hu A (2021) Optimal block size for improving urban vitality: an exploratory analysis with multiple vitality indicators. J Urban Plan Dev 147(3):04021027

Holl S (2014) Hybrid buildings. Oz 36(1):12

Hui ECM, Chen TT, Lang W, Ou YB (2021) Urban community regeneration and community vitality revitalization through participatory planning in China. Cities, 110:103072

Igualada J (2018) The Hybrid Block as Urban Form. En 24th ISUF International Conference. Book of Papers. Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València. 147-156. https://doi.org/10.4995/ISUF2017.2017.4927

Jacobs J (1961) The death and life of great American cities: Vintage

Jeffery CR (1977) Crime prevention through environmental design, vol 524. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA

Johnson D, Gibson V, McCabe M (2014) Designing crime prevention, designing ambiguity: practice issues with the CPTED knowledge framework available to professionals in the field and its potentially ambiguous nature. Crime Prev Community Saf 16(3):147–168

Kark R, Carmeli A (2009) Alive and creating: the mediating role of vitality and aliveness in the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement. J Organ Behav 30(6):785–804

Kuster C, Rezgui Y, Mourshed M (2017) Electrical load forecasting models: a critical systematic review. Sustain Cities Soc 35:257–270

Lawley DN, Maxwell AE (1962) Factor analysis as a statistical method. J R Stat Soc Ser D (Stat) 12(3):209–229

Lee JS, Park S, Jung S (2016) Effect of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) measures on active living and fear of crime. Sustainability 8(9):872

Li RYM (2015) Generation X and Y’s demand for homeownership in Hong Kong. Pac Rim Prop Res J 21(1):15–36

Li RYM, Li YL, Crabbe MJC, Manta O, Shoaib M (2021) The impact of sustainability awareness and moral values on environmental laws. Sustainability 13(11):5882

Li RYM, Shi M, Abankwa DA, Xu Y, Richter A, Ng KTW et al (2022) Exploring the market requirements for smart and traditional ageing housing units: a mixed methods approach. Smart Cities 5(4):1752–1775

Marzbali MH, Abdullah A, Abd Razak N, Tilaki MJM (2012a) Validating crime prevention through environmental design construct through checklist using structural equation modelling. Int J Law Crime Justice 40(2):82–99

Marzbali MH, Abdullah A, Razak NA, Tilaki MJM (2012b) The influence of crime prevention through environmental design on victimisation and fear of crime. J Environ Psychol 32(2):79–88

Maslow A (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev Google Sch 2:21–28

Mihinjac M, Saville G (2019) Third-generation crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED). Soc Sci 8(6):182

Milcu AI, Sherren K, Hanspach J, Abson D, Fischer J (2014) Navigating conflicting landscape aspirations: application of a photo-based Q-method in Transylvania (Central Romania). Land Use Policy 41:408–422

Minnery JR, Lim B (2005) Measuring crime prevention through environmental design. J Archit Plan Res 22(4):330–341

Mouratidis K, Poortinga W (2020) Built environment, urban vitality and social cohesion: Do vibrant neighborhoods foster strong communities? Landsc Urban Plan 204:103951

Newman O (1973) Defensible space: crime prevention through urban design. Collier Books New York

Pazhuhan M, Shahraki SZ, Kaveerad N, Cividino S, Clemente M, Salvati L (2020) Factors underlying life quality in urban contexts: evidence from an industrial city (Arak, Iran). Sustainability 12(6):2274

Pili S, Grigoriadis E, Carlucci M, Clemente M, Salvati L (2017) Towards sustainable growth? A multi-criteria assessment of (changing) urban forms. Ecol Indic 76:71–80

Reppetto TA (1976) Crime-prevention through environmental-policy—comment. Am Behav Sci 20(2):275–288

Rost F (2021) Q-sort methodology: Bridging the divide between qualitative and quantitative. An introduction to an innovative method for psychotherapy research. Couns Psychother Res 21(1):98–106

Ruoshi Z, Yao G, Yinjing L (2024) Research on small-scale characteristics of urban vitality space driven by multi-source sentiment data: with “Xidan The New” and “Beijing Fun” in Beijing as examples. China City Plan Rev 33(4):44–54

Sakip SRM (2019) Discovering Distinctive Street Patterns of Snatch Theft through Crime Prevention through Environmental Design. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal, e-IPH Ltd. https://doi.org/10.21834/E-BPJ.V4I12.1891

Salamagy HB, Alve, FB, do Vale CP (2023) Urban design solutions for the environmental requalification of informal neighbourhoods: the George Dimitrov Neighbourhood, Maputo. Urban Sci 7(1):12

Schneider RH (2005) Introduction: crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): themes, theories, practice, and conflict. J Archit Plan Res 22(4):271–283

Sun YJ, Jiao LM, Guo YQ, Xu ZB (2024) Recognizing urban shrinkage and growth patterns from a global perspective. Appl Geogr 166:103247

Tien PW, Wei SY, Calautit J (2021) A computer vision-based occupancy and equipment usage detection approach for reducing building energy demand. Energies 14(1):156

Wang WD, Xu ZB, Sun DQ, Lan T (2021) Spatial optimization of mega-city fire stations based on multi-source geospatial data: a case study in Beijing. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf 10(5):282

Simon W, Stenner P (2012) Doing Q Methodological Research: Theory, Method and Interpretation. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, Sage Research Methods, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446251911

Wen Y, Qi H, Long T (2024) Quantitative analysis and design countermeasures of space crime prevention in old residential area quarters. J Asian Archit Build Eng 23(6):2071–2090

Wo JC, Kim Y-A (2022) Neighborhood effects on crime in San Francisco: an examination of residential, nonresidential, and “mixed” land uses. Deviant Behav 43(1):61–78

Wo JC, Kim Y-A, Berg MT (2024) Alleyways and crime in Denver, Colorado census blocks. Cities 151:105138

Wold S, Esbensen K, Geladi P (1987) Principal component analysis. Chemom Intell Lab Syst 2(1-3):37–52

Wu WS, Niu XY (2019) Influence of built environment on urban vitality: case study of Shanghai using mobile phone location data. J Urban Plan Dev 145(3):04019007

Wu X, Tan X (2023) Is the gated community really safe? An empirical analysis based on communities with varying degrees of closure. Int J Urban Sci 27(4):725–745

Xie A, Chen J (2021) Determining sample size in qualitative research: saturation, its conceptualization, operationalization and relevant debates. J East China Norm Univ (Educ Sci) 39(12):15

Xu H, Zhao G (2021) Assessing the value of urban green infrastructure ecosystem services for high-density urban management and development: case from the capital core area of Beijing, China. Sustainability 13(21):12115

Yang L, Iwami M, Chen Y, Wu M, van Dam KH (2023a) Computational decision-support tools for urban design to improve resilience against COVID-19 and other infectious diseases: a systematic review. Prog Plan 168:100657

Yang L, Wu M, Chen Y, Wu C (2023b) Examining the impact of the urban transportation system on tangible and intangible vitality at the city-block scale in Nanjing, China. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 51(8):1833–1853. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083231223867

Yue Y, Zhuang Y, Yeh AGO, Xie JY, Ma CL, Li QQ (2017) Measurements of POI-based mixed use and their relationships with neighbourhood vibrancy. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 31(4):658–675

Zhang Y, Jin H, Xiao Y, Gao Y (2020) What are the effects of demographic structures on housing consumption?: evidence from 31 provinces in China. Math Probl Eng 2020(1):6974276

Zhuang L, Ye C (2023) Spatial production in the process of rapid urbanisation and ageing: a case study of the new type of community in suburban Shanghai. Habitat Int 139:11

Acknowledgements

A special thank you goes to all local participants who gave us their valuable time, shared their opinions, and provided important data for the study. We are also grateful to our institution for providing us with a good platform and opportunity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuerong An conceived and designed the experiments, performed the data analysis, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Xiangguo Peng supervised the project and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. Yu Xia conducted the experiments, assisted with data analysis, and helped in drafting the manuscript. Junming Zhao and Jiaxin Liu contributed to the experimental design and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained by institutional review board of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (IRB of UCAS). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations applicable. The approval was obtained retrospectively. (As the Science and Technology Ethics Committee of UCAS was established in May 2023 and the “Measures for the Review of Science and Technology Ethics” came into effect in October 2023, an ethical review could not be conducted before the start of this study). During the publication process, the study supplemented the ethical review process as required, confirmed the study met the ethical requirements of UCAS and the content of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, and obtained ethical approval (No: UCASSTEC24-025, Date of approval: November 1, 2024). Scope of approval: including 1. Application Form for Ethical review of science and technology of University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. 2. Personal Information Anonymity Form (including Informed Consent). 3. Q Method Questionnaire. Approve the purpose, methods, data usage and publication of this study. This study does not involve scientific and technological experiments involving humans or animals, nor does it have related risks, and it belongs to a project whose risk occurrence probability and degree are not higher than the lowest risk in the Science and technology ethics of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained by oral from each participant on the spot during the experiment implementation period (Date: September 1st–November 30th, 2021). All consents were collected by the authors. Due to the consideration of time control in the experiment, the author provided a detailed description and obtained oral consent before participation. Participation in this study indicates that the participants are informed and agree. Scope of the consent: participation, the purpose of the study, process, methods of data use, any risks to them of participating and consent to publish. All participants have been fully informed that their anonymity is assured.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

An, Y., Peng, X., Xia, Y. et al. Q-methodological exploration of environmental characteristics affecting residential security in hybrid blocks: a focus on Beijing. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1998 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06293-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06293-7