Abstract

This study aims to investigate the relationship between coaches’ caring behaviors (including dedication, supportiveness, and inclusiveness) and the sports cognitive levels of adolescent athletes (encompassing sport imagery, attentional capacity, sport perception, and cognitive abilities), while also examining the indirect association of achievement goals (specifically ego-oriented goals). A total of 226 adolescent athletes (aged 12–18 years) participated in this study, representing a range of sports including handball, rowing, and rugby. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to analyze the path coefficients and indirect association. The findings revealed that coaches’ caring behaviors significantly and positively predicted adolescent athletes’ sports cognitive levels (β = 0.39–0.67). Specifically, ego-oriented goals exhibited a significant positive indirect association in the relationship between coaches’ caring behaviors and adolescent athletes’ sports cognitive levels (β = 0.19–0.31), while task-oriented goals maybe showed a negative indirect association (β = −0.05 to 0.14). In summary, there is a significant relationship between coaches’ caring behaviors and the sports cognitive levels of adolescent athletes. Positive coaches’ caring behaviors enhance sports cognitive levels of adolescent athletes. Notably, supportive and inclusive behaviors demonstrated more pronounced direct and indirect predict, particularly on athletes’ cognitive abilities and sports perceptions. Furthermore, ego-oriented goals within the achievement goals were found to have a significant positive predict, while task-oriented goals attenuated this effect. This suggests that coaches should prioritize supportive and inclusive practices in athletic training while also emphasizing the cultivation of ego-oriented goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coach caring behaviors Lei (2015) are defined as a set of actions demonstrated by coaches that reflect concern, support, and understanding for athletes during training and competition. This form of care encompasses not only an emphasis on athletes’ technical skills and competitive performance but also addresses their psychological well-being, emotional needs, and overall personal development. Lei (2015) posits that coaching care behaviors are conceptualized as encompassing three key dimensions: dedication, inclusiveness, and supportiveness, reflecting a multidimensional approach to athletes’ well-being. While extant research employs methods such as interviews and observations to measure coach caring behavior, questionnaire surveys remain the prevalent methodology, given their established utility in assessing psychological constructs. This study similarly utilizes a questionnaire-based approach to measure this construct. Athletes emphasize the critical role of coaches as facilitators of a positive atmosphere, highlighting their preference for an encouraging and caring environment. This underscores the significance of cultivating a supportive context for elite athletes (Pensgaard and Roberts, 2002). Furthermore, when athletes experience a greater degree of care within their teams, they exhibit enhanced motivation and a more positive attitude towards the team, ultimately benefiting their performance (Fry and Gano-Overway, 2010). Additionally, research has indicated that parental caring behaviors at home predict athletes’ perfectionistic tendencies, providing preliminary theoretical support for the influence of coaches’ caring behaviors on child athletes’ perfectionism (Appleton et al., 2011). All adolescent athletes participating in this experiment were separated from their parents, with their daily routines and training managed uniformly by coaches within the training team. Consequently, the coaches assumed the role of guardians. Through our review of previous literature, we found that Seanor stated in his paper that the closed Chinese training environment has also supported Olympic podium performances. These discrepancies highlight the importance of tailoring training environments for athletes holistically. (Seanor et al., 2019) At the same time, we note that Wang et al. (2021) paper introduction indicates athletes are in a relatively independent and closed environment for a long time in China. The training, learning, and living environment of athletes is relatively independent and closed for a long time, and the breadth, depth, and integration of real social interaction are subject to certain limitations. Zhang (2017b) research also indicates that the sports schools where athletes train are “single, closed and extensive” training mode is divorced from the track of social development, and does not understand the guideline of “people-oriented and comprehensive training” advocated by the state, which only focuses on the surface of the operation, without paying attention to the training process and the evaluation of social benefits. At the same time, through our review of the literature, we found that Chen et al. (2022) research mentioned the brilliance of Chinese women’s throwing benefits from the closed-loop personalized training system. Training starts from the construction of accurate personalized technology and physical fitness model. This confirms that most Chinese athletes undergo closed-door training, with coaches naturally assuming the role of guardians. Therefore, we believe that the coach’s care may play a role similar to that of parental care. Moreover, research indicates when coaches foster and emphasize a more positive atmosphere, athletes exhibit enhanced perceptual abilities (Weiss et al., 2009). Additionally, a positive coach-athlete relationship can enhance athletes’ cognitive functions (Davis et al., 2018). Past research indicates that coaches’ care for athletes enhances athletes’ perception and cognition. The sports cognitive level indicators cited in this paper include motor imagery, attentional capacity, sport perception (SPP), and cognitive abilities (Dong Delong, 2007). This represents more of an integration of the psychological dimension of athletes’ motor cognition. Therefore, we believe that the care by coaches in this study will still exert a certain influence on the athletes’ sport cognition levels referenced in this research.

Sports cognitive typically refers to an individual’s cognitive abilities, thought processes, and decision-making skills within the context of movement or sport. This encompassing construct includes aspects such as understanding of motor skills, tactical analysis, information processing speed, attention, memory, and learning capacity. In studies examining athletes’ motor cognition both domestically and internationally, methodologies such as experimentation and physiological measurement are commonly employed. In this research, motor cognition is operationalized through a questionnaire encompassing four components: motor imagery, attentional capacity, SPP, and cognitive abilities (Dong Delong, 2007). Adolescent athletes provide a comprehensive self-evaluation of their motor cognition levels based on these components included in the questionnaire. The extent of supportive behaviors exhibited by coaches serves as a significant predictor of athletes’ perceptual abilities, sense of relatedness, and autonomy, which, in turn, inversely predicts athletes’ motivation orientation (Amorose and Anderson-Butcher, 2007). Generally speaking, more positive, enriching, and inspiring coaching behaviors are positively associated with athletes’ self-perception, emotions, and overall motivation (Amorous and Anderson-Butcher, 2007). Analysis indicates that the feedback provided by coaches is closely linked to athletes’ perceptual abilities and satisfaction (Allen and Howe, 1998). Positive feedback provided by coaches (encouragement, praise) enhances athletes’ athletic abilities and satisfaction. Such positive feedback can be interpreted as a demonstration of the coach’s care. In the field of sports, the use of mediating effects is relatively common in research. For example, Arribas-Galarraga et al. (2020) primarily focuses on the purpose of this research is to examine the association of perceived fitness and self-efficacy with sport practices and to determine whether perceived fitness is a mediator of the association between self-efficacy and sport practice in Spanish adolescents. Domaradzki et al. (2021) investigated the main aim of this study was to examine the mediating effect of the change of direction speed on reactive agility (RA) in female players participating in different team sports (TS). Moreover, in the study by Csajbók et al. (2022) used large-scale longitudinal data from 51,191 adults 50 years of age or older (mean: 64.8 years, 54.7% women) from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Results of the longitudinal mediation analyses combined with autoregressive cross-lagged panel models showed that the model with physical activity as a mediator better fitted the data than the model with cognitive function as a mediator. This demonstrates that the use of mediating effects in research is quite common within the field of sports. In studies employing mediating effects, achievement goals are frequently examined as mediating variables to explore their relationships with other variables. X. Wang et al. (2024) investigated the relationship between team behaviors (i.e., perceptions of controlling coaching behavior and team cohesion) and competitive anxiety, and to examine the mediation effects of achievement goals (i.e., task-oriented and ego-oriented) on the relationship. Tomczak et al. (2024) study was to determine whether hope for success mediates the relationship between personality and goal orientation in high performance and recreational athletes. To assess hope for success, they used the Hope for Success Questionnaire. The Task and Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire (TEOSQ) was employed to examine goal orientation. Yang et al. (2024) study was based on the theories of motivational climate and achievement goal orientation, an experimental intervention was conducted on 82 junior high school students using the Motivational Climate Scale (MCSYS), TEOSQ, and Physical Activity Persistence Scale. The aim was to explore the influence of different motivational climates in physical education classes on the physical activity adherence among junior high school students and examine the mediating role of achievement goal orientation. Our current study also examines achievement goals as a mediating factor, exploring their relationship with coaches’ care and the sports cognition levels of adolescent athletes.

According to the Achievement Goal Theory (Dweck, 1986), this theoretical framework primarily aims to elucidate the various types of motivation and goals individuals pursue in the context of achievement. Athletes’ achievement goals consist of two components: task-oriented and ego-oriented.Task orientation refers to an individual’s tendency to focus on task completion and achievement. Ego-oriented achievement is characterized by a tendency to focus on social comparison and self-evaluation, prioritizing competition to outperform others, achieving superior performance, or avoiding underperformance or failure in the presence of others. Dweck’s early research predominantly relied on survey methodology; specifically, it involved the design and utilization of self-report questionnaires to evaluate individuals’ achievement goal orientations. This study similarly employs a questionnaire-based approach. Individuals with a task-oriented mindset prioritize the fulfillment of tasks and personal accomplishments, concentrating more on their growth and progress. They emphasize the enhancement and development of their own skills and abilities. Individuals with a task-oriented goal approach focus on learning and mastering new knowledge or skills, prioritizing personal progress and development rather than social comparison. Dweck (1986) theory posits that the pursuit of different achievement goal orientations leads to distinct psychological responses and learning strategies. Adie et al. (2008) studied 424 team athletes and found that mastery approach goals positively correlated with challenge appraisals (e.g., “competition is an opportunity to improve skills”), which in turn promoted positive emotions (such as excitement) and self-efficacy. For instance, soccer players adopting a task-oriented approach during matches tended to enjoy the competitive process more and proactively learn opponents’ tactical details. Wang et al. (2016) found in their study of Singaporean adolescents that task-oriented goals (TSK) positively correlate with persistence in physical activity participation. For instance, students primarily driven by TSK focus more on personal progress (such as improving times) during long-distance running training rather than comparing themselves to others, making them more likely to maintain exercise routines over the long term. In contrast, students guided by ego-oriented goals (EGO), due to excessive concern over social evaluation, exhibited a 30% higher dropout rate. Elliot and Church (1997) found in their judo study that athletes with performance avoidance goals (EGO) focused more on “avoiding mistakes” than “improving technique” during competition. For instance, they might choose conservative tactics (such as passive defense) rather than actively attempting new moves, leading to stagnation in skill development. This strategy aligns with Dweck (1986) descriptions of “challenge avoidance” and “low persistence”.

The perception of a mastery climate established by coaches is associated with the TSK of the athletic team, while the performance climate fostered by coaches relates to the EGO of the athletic team (Gjesdal et al., 2018). Furthermore, a study indicated that among students in grades 4 through 11, self-mastery behaviors demonstrate a positive correlation with perceived task climate, as well as both task-oriented and EGO (Xiang and Lee, 2002). The climate that coaches develop in the context of sports tasks can elucidate athletes’ TSK, and male athletes with elevated TSK typically display enhanced athletic capability (Atkins et al., 2014). Additionally, TSK directly impact athletes’ perceived competence, effort, and intrinsic motivation (Williams and Gill, 1995). Isoard-Gautheur et al. (2015) examined the impact of coach-athlete relationship quality on athlete burnout through the lens of achievement goal theory, testing the mediating role of achievement goals in this relationship. Based on achievement goal theory, this study proposes that the coach-athlete relationship comprising three dimensions of commitment, closeness, and complementarity may indirectly regulate burnout levels by influencing athletes’ achievement goals, such as mastery-approach goals and performance-avoidance goals. Jung, K. I. (2014) examined the structural relationships among adolescent athletes’ perceptions of coaching behaviors, achievement goal orientations, and sport persistence. Coaches’ autonomy-supportive behaviors (e.g., offering choices, encouraging autonomous decision-making) exerted a positive indirect effect on sport persistence by promoting mastery approach goals (skill-oriented) (β = 0.212, p < 0.05), while also directly enhancing athletes’ intrinsic motivation and positive affect. Mastery-oriented goals (task-oriented) within achievement goals fully mediated the relationship between autonomy support and sport persistence, highlighting that skill-improvement goals sustain long-term participation. Separately, a robust line of inquiry, grounded in achievement goal theory, has shown that an athlete’s goal orientation (e.g., task vs. ego) is a powerful predictor of cognitive engagement, learning strategies, and adaptive outcomes in sport (Duda, 2013). While previous research and practice suggest that achievement goals may mediate the relationship between coaching behaviors and young athletes’ sport cognitive skills, empirical evidence directly examining this mediating role remains scarce. Therefore, this study further aims to investigate the mediating role of achievement goals in the relationship between coaches’ care and the sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes.

In summary, past research has not explicitly established a positive correlation between coaches’ care and the sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes, nor has it provided clear evidence of a indirect pathway of achievement goals in the relationship between coaches’ care and the sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to investigate the relationship between coaches’ care and the sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes, while also exploring the indirect pathway of achievement goals in this relationship.

Methods

Participants

A total of 226 athletes (145 males and 81 females) from rowing, rugby, and handball participated in this study. Of the 226 adolescent athletes invited participating, all completed the questionnaire (100% response rate).In the research design,five adolescent athletes either failed to provide valid age information or did not provide any age information. Therefore, after excluding these five athletes, the total number of valid data entries is 221. We conducted a priori analysis using G*Power software (Test family: t tests; Statistical test: Means: Difference between two independent means (two groups); Type of power analysis: A priori: Compute required sample size - given α, power, and effect size), with the following input parameters: Tail(s): two; α err prob = 0.05; Effect size d = 0.5; Power (1-β err prob) = 0.8 yielded a total sample size of 128, which is less than 221. Thus, our sample size is acceptable. The age range for adolescent athletes is 12–18 years old, comprising 8 athletes aged 12, 24 athletes aged 13, 49 athletes aged 14, 56 athletes aged 15, 63 athletes aged 16, 16 athletes aged 17, and 5 athletes aged 18,this study obtained ethical approval from coaches and relevant sporting authorities for the survey administration to adolescent athletes,their legal guardians provided informed consent (Ethics approval number: LDU-IRB202311002). All questionnaires were completed anonymously and voluntarily, with parental consent obtained. Data collection occurred in July 2024. To ensure data accuracy, a non-distracting environment was provided for questionnaire completion. Training experience was distributed as follows: 53.1% of athletes had 1–2 years of training, 41.59% had 3–4 years, and 5.31% had ≥5 years. Athletes’ competitive levels ranged from Class III athletes to Master athletes. Detailed participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Measures

This study employed a questionnaire to collect data from adolescent athletes. The questionnaire encompassed demographic information (sex, age, sport, years of training, and competitive level), the Teachers’ Caring Behavior Scale (TCBS), a psychometric assessment of sport-cognitive levels, and the TEOSQ. The reliability and validity of the scales were assessed to ensure internal validity.

Coaches’ caring behavior

This study employed the Teacher Caring Behavior Scale developed by Lei (2015) to measure adolescent athletes’ perceptions of coaches’ caring behaviors. The scale comprises three dimensions (dedication, supportiveness, and inclusiveness) encompassing 18 items (7, 6, and 5 items, respectively). Responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “completely disagree” to 5 = “completely agree”). Higher scores indicated more pronounced coach caring behaviors. We acknowledge that directly transferring a scale from an educational to a sport context requires justification. We have now provided a strong theoretical argument for its applicability, given the parallel authoritative and developmental roles of coaches and teachers.

Crucially, we conducted a new CFA specifically for the TCBS within our athletic sample. The results confirmed the original three-factor structure (dedication, supportiveness, inclusiveness) with good fit indices (e.g., RMR = [0.02], IFI = [0.901], CFI = [0.901], NFI = [0.874]) and strong, significant factor loadings

Similarly, we established measurement invariance for the TCBS across gender and sport type, strengthening our confidence in using this instrument with diverse groups of athletes. (Tables 2, 3).

The results supported configural, metric, and scalar invariance, indicating that the scale is interpreted similarly across these groups.

Sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes

This study utilized the Sport Cognition Level Psychological Test developed by Dong Delong to assess the level of sport cognition in adolescent athletes. (Dong Delong, 2007) The scale comprises four dimensions (motor imagery, attentional capacity, sport perception, and cognitive ability), totaling 37 items (10, 10, 9, and 8 items, respectively). The questionnaire included three reverse-scored items: “I am easily distracted by certain factors” (attentional capacity), “I am easily influenced by the audience” (attentional capacity), and “I cannot concentrate my attention” (attentional capacity). Responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “completely disagree” to 5 = “completely agree”). After reverse scoring the three reverse-coded items, adolescent athletes’ sport cognition levels were represented by total scores. Higher scores indicated higher levels of sport cognition. For this study, the scale was slightly modified by removing the three reverse-scored items. We have performed a new Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) on the modified 34-item scale (with the 3 reverse-scored items removed) to formally establish its factor structure in our sample. The CFA results demonstrated excellent model fit (e.g., χ²/df = [2.071], CFI = [0.920], TLI = [0.913], RMSEA = [0.07]), and all factor loadings were significant and above the recommended threshold of 0.5, and analyze the structural reliability and effectiveness(Table 4). Composite reliability (CR) for each subscale was above 0.70, and average variance extracted (AVE) was above 0.50, indicating good convergent validity. We have also tested for measurement invariance across gender and sport type (e.g., handball; rugby and rowing). The results supported configural, metric, and scalar invariance, indicating that the scale is interpreted similarly across these groups. (Tables 5, 6).

The results reveal a borderline case: Compared to Metric Invariance, the change in fit indices for Scalar Invariance shows ΔCFI = 0.015, slightly exceeding the strict threshold of 0.01; however, ΔRMSEA = 0.002 indicates excellent performance. Moreover, the absolute fit indices of the constrained model remain within acceptable ranges (CFI > 0.8, RMSEA < 0.08). According to methodological scholars such as Putnick and Bornstein (2016), when ΔCFI slightly exceeds the threshold but ΔRMSEA performs well and the absolute fit of the constrained model is acceptable, measurement invariance should be considered established through comprehensive judgment. Therefore, we conclude that the scalar invariance hypothesis is generally supported, allowing for subsequent scale equivalence testing and cross-group comparisons. However, interpretation of the results should be approached with caution.

Achievement goals

The Task and Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire (TEOSQ; Duda and Nicholls, 1992) is a widely utilized instrument in the field of sports for assessing athletes’ achievement goals, specifically focusing on task orientation and self-referent orientation. These questionnaires typically comprise a series of statements, to which participants rate their agreement based on their thoughts and feelings. In this study, the TEOSQ was employed to evaluate the achievement motivation of adolescent athletes. The questionnaire comprises two dimensions with a total of 13 items: task orientation (7 items) and ego orientation (6 items). The internal consistency results of the TEOSQ indicate acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.900 to 0.917, and goodness-of-fit indices as follows: RMR = 0.024, GFI = 0.942, CFI = 0.979, NFI = 0.960.

Statistical analysis

This study employed the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27.0) for descriptive statistics and correlational analysis. Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted on coaching caring behaviors, achievement goals, and the sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes, encompassing the calculation of means, standard deviations, and percentages. CFA was conducted using Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS, version 24.0) to assess the model fit for each latent construct within the structural equation model (SEM). Model fit was evaluated using the following indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/df). Acceptable model fit was indicated by the following criteria: RMSEA ≤ 0.096, χ²/df ≤ 3.039, and CFI, TLI, and IFI > 0.7. Although the values for CFI, TLI, and IFI are slightly below the commonly accepted benchmark of 0.90 for excellent fit, we consider the overall model fit to be acceptable based on a comprehensive evaluation of multiple indicators and relevant literature. (Marsh et al., 2004; Barrett, 2007). We constructed a single-factor model, forcing all measurement items to load onto a common factor. The model’s fit indices fell significantly below acceptable standards (e.g., χ²/df = 4.733, CFI = 0.514, TLI = 0.496, RMSEA = 0.13). CFA results offer stronger evidence that common method bias does not pose a significant threat in this study.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 7 presents significant positive correlations (p < 0.05) among coach caring behaviors (dedication, supportiveness, inclusiveness), achievement goals (task-oriented and ego-oriented), and athletes’ sport-cognitive abilities (motor imagery, attentional capacity, sport perception, and cognitive ability). Specifically, inclusiveness (INC) within coach caring behaviors, and motor imagery (MIR), cognitive ability (COG), and SPP within sport-cognitive abilities showed stronger correlations with TSK. Furthermore, all dimensions of sports cognitive level exhibited stronger correlations with EGO.

Structural equation modeling results

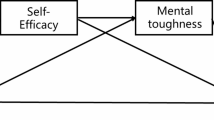

The results of the SEM are presented in Fig. 1. In this study’s SEM, coach caring behaviors exhibited significant positive predictive predict on both ego-oriented and TSK, and on adolescent athletes’ sport-cognitive level (except for the dedication dimension of coach caring behaviors on EGO, where β = 0.04; all other β ≥ 0.24). EGO served as aindirect pathway, positively predicting the relationship between coach caring behaviors and adolescent athletes’ sport-cognitive abilities (β = 0.52, 0.71, 0.31, 0.27). TSK may served as a ainirect pathway, negatively predicting the relationship between coach caring behaviors and adolescent athletes’ sport-cognitive level (β = −0.10, −0.13, −0.14).

Tables 8, 9, and 10 illustrate the indirect association of achievement goals (TSK and EGO) in the relationship between coaching caring behaviors and youth athletes’ sport cognitive level. Research findings indicate that achievement goals serve as an indirect pathway between coaching behaviors and adolescents’ sports cognitive levels. However, EGO exhibited a significant positive indirect association, while the negative indirect association of TSK was not statistically significant. Furthermore, the indirect association of EGO was strongest in the relationship between the supportiveness dimension of coaching caring behaviors and youth athletes’ sport cognitive level.

The study found that, from a direct effects’ perspective, coaches’ inclusiveness had a positive and significant predict on various dimensions of athletes’ sport cognitive performance. In terms of indirect predict, coaches’ supportiveness exerted a significant predict on MIR, attention capacity (ATT), COG, and SPP through EGO. However, the overall predict did not reach statistical significance, potentially due to the negative predict of TSK. Regarding the supportive dimension of coaching caring behavior, coaches’ supportiveness positively predict athletes’ cognitive level, exhibiting a notable indirect predict. This indirect predict was particularly pronounced on COG and SPP via EGO. Similarly, for the inclusiveness dimension of coaching caring behavior, direct predict were more prominent. Indirect predict also exerted a certain negative predict on ATT, COG, and SPP through TSK. These findings indicate that coaches’ care has a significant positive direct predict on enhancing athletes’ overall cognitive level. Additionally, supportiveness and inclusiveness may exert a noteworthy positive predict on athletes’ cognitive skills and SPP through ego-directed goals. In contrast, TSK may undermine this positive predict.

Discussion

The findings revealed that all three dimensions of coaches’ caring behaviors (dedication, supportiveness, and inclusiveness) positively predicted all four dimensions of adolescent athletes’ sport-cognitive level (motor imagery, attentional capacity, sport perception, and cognitive skills). The results indicated a significant positive correlation between coaches’ caring behaviors and adolescent athletes’ sport-cognitive level. This suggests that higher levels of coaches’ caring behaviors are associated with enhanced sport-cognitive level in adolescent athletes, a finding consistent with previous research. Jin et al. (2022) found that coaches’ selection of appropriate leadership styles in various situations can improve athlete satisfaction and performance. Converging evidence from Kim et al. (2019) and Friesen (2017) underscores the interrelationship among the coaching environment, athlete emotions, and performance outcomes. Kim and colleagues showed that a positive environment fosters a strong coach-athlete relationship and boosts perceived competence, while Friesen provided a complementary perspective by demonstrating that optimal performance is linked to emotions, which are, in turn, anticipated through coach interactions. The research conducted by Davis et al. (2013) also found that high-quality relationships between coaches and athletes can enhance athletes’ sport experience, health, and performance. Furthermore, Davis et al. (2018) corroborated that sport practitioners and coaches should consider fostering high-quality relationships between coaches and athletes as a means to facilitate optimal athlete performance.This also validates that the high-quality relationships formed by coaches caring for young athletes in this study enhance the athletes’ sports cognition.

A key and nuanced finding from our study was coaching care positively predicts both ego-oriented and TSK [as shown in our path model in Fig. 1], aligns with the empirical findings of Roberts and Ommundsen (1996). This suggests that a caring coach-athlete relationship does not uniformly steer athletes toward a single type of motivation. To understand this duality, the framework of Roberts and Ommundsen (1996) provides a compelling explanation: athletes with different predispositions may interpret the same caring climate through different lenses. This dual pathway can be interpreted in two ways, both of which are likely at play. For the less elite or younger athletes in our study, the positive link to EGO may reflect how a positive situational climate can temporarily heighten competitive perceptions as they navigate their personal achievement goals. However, the more robust explanation for our findings, particularly among the more competitive sub-group, aligns with the second mechanism proposed by Roberts and Ommundsen (1996): athletes with a pre-existing tendency toward ego-orientation likely selectively attended to the competitive cues within the caring environment (e.g., the coach’s high expectations), interpreting the climate as one that validates their personal need to demonstrate superiority. Conversely, those with a stronger task-orientation likely focused on the supportive and mastery-focused aspects of the coach’s care. Thus, our results extend the theory by demonstrating that a general climate of care can simultaneously sustain these parallel interpretive processes within a single team, leading to divergent motivational outcomes. Similarly, the research conducted by Gjesdal et al. (2018) confirmed that the positive motivational climate created by coaches positively predicts athletes’ achievement goals (task-oriented and ego-oriented). Furthermore, as perceptions of the climate among coaches and athletes increase, the team’s TSK also exhibit a rising trend.

However, the study by Weltevreden (2018) indicates that among adolescent athletes, the motivational climate initiated by parents is a predictor of athletes’ achievement goals, rather than the motivational climate initiated by coaches. This finding contrasts with the conclusions drawn in our current study. We posit that the discrepancy in results may stem from differences in the living environments of adolescent athletes being studied. Furthermore, our study demonstrates that EGO serve as a mediating factor with a positive predictive predict on the sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Nicholls (1989), which indicated that EGO can enhance performance among athletes with high normative capability. Similarly, the work of Dunn et al. (2000) revealed that EGO can exert a positive direct impact on perceptual abilities in certain competitive contexts. However, it is crucial to interpret this finding with nuance and against the robust theoretical backdrop that consistently champions the adaptive advantages of a task-oriented mindset for most athlete outcomes (Duda, 2013). A task-oriented focus on learning, effort, and self-improvement is unequivocally linked to greater intrinsic motivation, resilience in the face of failure, and long-term sport enjoyment. The positive role of ego-orientation observed in our study is likely specific to our unique sample. The adolescent athletes in our research were largely separated from their parents and immersed in a highly structured, competitive training environment. In such a setting, where social comparison is inherent and selection for advancement is constant, a strong ego-orientation might serve as an adaptive, short-term driver for cognitive engagement. These athletes may be highly attuned to competitive cues, pushing their cognitive skills to avoid negative evaluation and to stand out among their peers. Nevertheless, we posit that this pathway, while significant, may be less sustainable than one driven by task-orientation. Over-reliance on EGO can increase the risk of anxiety, burnout, and maladaptive coping strategies if an athlete’s perceived competence declines (Duda, 2013). Therefore, while our results reveal a functional aspect of ego-orientation in a high-performance boarding context, the ultimate aim for coaches should be to foster a balanced or predominantly task-oriented climate. This ensures that athletes’ cognitive development is coupled with the psychological well-being and motivational resilience that task-orientation provides, safeguarding their long-term development and success. Additionally, Tomczak et al. (2020) confirmed that high-level individual athletes often exhibit stronger EGO, while the research by Newton et al. (2004) highlighted that, among male samples in the experimental group, personal-oriented goals were the sole significant predictor of specific self-perceptions related to individual athletic ability, physical attractiveness, health status, and self-worth. Furthermore, EGO positively predicted adolescent athletes’ cognitive level, we tested for the potential mediating role of TSK, but the analysis did not yield significant mediating pathways. Overall, coaches’ caring behaviors positively predict adolescent athletes’ sport cognitive levels through the indirect association of EGO, while potentially negatively predicting these levels through the indirect association of TSK. (For details, please refer to Tables [4, 5, 6] and Fig. [1]). In direct predict, enhancing coaches’ inclusiveness significantly improve adolescent athletes’ sport cognition level. In indirect predict involving EGO, enhancing coaches’ supportiveness should significantly improve adolescent athletes’ sport cognition level. These differential findings highlight the distinct roles played by the sub-dimensions of caring coaching behaviors. The significant direct effect of inclusiveness aligns with research emphasizing that a perceived sense of belonging and acceptance within a team creates a secure psychological environment (Zheng and Wang, 2021). This security may allow athletes to focus cognitive resources on learning and strategy without the distraction of social threats, thereby directly enhancing their sport cognition. The coach’s support also significantly enhances the psychological environment for athlete safety. Within China’s unique competitive landscape, this may stimulate athletes’ EGO, thereby elevating their own athletic cognitive abilities. May be attributed to the competitive nature of the Chinese education system, which emphasizes high-level performance, as well as the interplay between individualism and collectivism (Xiang, 1997, 2001).

Moreover, the results of the current experiment indicate that TSK exert an negative predictive effect on the sports cognition of adolescent athletes, which diverges from previous experimental findings. Research by Williams and Gill (1995) suggested that TSK directly influence perceptual abilities, interest, and effort, rather than EGO. Similarly, Jakobsen (2021) identified that a task-oriented environment fosters a more positive atmosphere for athletes, whereas a ego-oriented environment may trigger negative emotions, adversely affecting athletes’ performance.We posit that the discrepancies in research findings may stem from variations in sociocultural contexts, leading to differing emphases on task-oriented versus EGO among the study participants. This is supported by the research of Gao et al. (2008), which compared American and Chinese students and found that Chinese students placed a greater emphasis on EGO, with these goals, alongside self-efficacy, serving as positive predictors of persistence. Research by Xiang (1997, 2001) indicates that the predominance of EGO among Chinese students may be attributed to the competitive nature of the Chinese education system, which emphasizes high-level performance, as well as the interplay between individualism and collectivism, which can further explain these differences. Within the context of high collectivism in China, each athlete’s focus is primarily on demonstrating the requisite abilities and garnering collective attention through their performance outcomes. Consequently, the differing educational cultures regarding the definition of success may contribute to discrepancies in the emphasis placed on achievement goals. While the sociocultural context provides a plausible explanation for the prominence and predictive power of EGO in our sample, the critical question remains: is a cultural emphasis on EGO ultimately beneficial for the athletes’ long-term development and well-being? The consensus in sport psychology, largely built upon research in Western contexts, strongly suggests that a predominant focus on TSK is more adaptive. It is linked to greater psychological well-being, sustained intrinsic motivation, and resilience in the face of setbacks (Duda, 2013). In contrast, an over-reliance on EGO can render an athlete’s self-worth and motivation contingent on outperforming others, which is an unstable foundation. This can lead to heightened anxiety, avoidance of challenging tasks for fear of failure, and an increased risk of burnout when normative standards are not met. Therefore, the positive predictive predict of EGO observed here should not be interpreted as an endorsement of this motivational climate. Instead, it may be seen as an adaptive, yet potentially costly, short-term response to a highly competitive and collectivist system where social comparison is inevitable and rewards are tied to outperforming peers. The athletes in our structured, boarding-style training environment are under immense pressure to succeed and justify the collective investment in them, making ego-oriented striving a functional, if not necessary, strategy for immediate survival and recognition. Vallerand et al. (2002) noted that social factors (including cultural context) shape individuals’ motivational types by influencing the fulfillment of their psychological needs (autonomy, competence, relatedness). This implies that in cultural environments emphasizing collective goals and external evaluation (such as East Asian cultures), individuals’ motivational styles are more likely to be systematically shaped toward external regulation rather than purely intrinsic motivation. This may explain why the adolescent athletes in this study exhibited a tendency toward EGO. Meanwhile, Sheldon et al. (2007) renowned longitudinal study offers a classic case of how environments reshape motivation. Tracking law students, it found that a law school environment emphasizing external rewards (such as grade rankings and high-paying jobs) systematically eroded students’ intrinsic motivation and autonomy. Over time, students’ well-being declined while their values became increasingly externalized (e.g., placing greater emphasis on money and status). This study perfectly parallels the competitive sports environment in China you described: when a system (whether law school or sports academies) strongly and persistently emphasizes normative comparison and external outcomes, it effectively shifts participants’ goal orientation from “mastery and interest” toward “performance and reward.” This explains why EGO emerge as a significant predictor in our research. This presents a significant practical implication. Coaches and sports administrators operating within such cultures face a dual challenge: they must prepare athletes to compete and succeed within the existing system, while also safeguarding their long-term psychological health. A crucial strategy would be to consciously foster a dual-focused or balanced motivational climate. Even within a system that inherently values outcomes, coaches can emphasize personal progress, effort, and learning from mistakes (task-oriented elements) alongside the competitive demands. This balanced approach may help harness the competitive drive fostered by the culture while buffering against its potential negative psychological consequences, ultimately cultivating more well-rounded and resilient athletes.

This study investigated the relationships among adolescent athletes’ sport-cognitive level, coaches’ caring behaviors, and achievement goals. Specifically, it tested the indirect association of achievement goals, encompassing ego-oriented. Although this study demonstrates a significant relationship among coaching caring behaviors, sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes, and achievement goals, we acknowledge certain limitations in our research. Given that a cross-sectional survey approach was employed, the findings are constrained regarding the temporal changes that may exist between the variables and causal relationships. Therefore, this study primarily validated the relationship among coaching care behaviors, sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes, and achievement goals over a specific timeframe. This limitation may impede a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic interplay between these three constructs. Future research should employ a longitudinal design to capture the temporal dynamics of the variables under investigation, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the results. Furthermore, the sampling method used in this study lacked generalizability, failing to encompass the entire target population, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Thirdly, given the limited sample size and the heterogeneity in athletic skill levels and age, caution should be exercised in interpreting the results, suggesting that the findings may be more applicable to adolescents. Finally, the data collected in this study relied on self-reported questionnaires completed by adolescent athletes, particularly concerning coaching care behaviors. Although anonymity was ensured, the potential for response bias cannot be entirely ruled out, potentially affecting the study’s results and leading to an incomplete representation of the adolescents’ true thoughts and experiences.

Conclusion

This enhanced the findings of this study support the notion that coaching care behaviors (dedication, support, and inclusiveness), along with achievement goals, predict the sport cognition of adolescent athletes. Specifically, we found that coaching support and inclusiveness had a significantly stronger direct predict on athletes’ cognitive skills and SPP. Furthermore, a significantly stronger positive indirect predict was observed through EGO, suggesting that higher levels of coaching care behaviors positively predict adolescent athletes’ sport cognition, with EGO link to this relationship. Conversely, TSK may attenuate this predict. Therefore, enhancing coaching care behaviors, particularly support and inclusiveness, while reducing an emphasis on TSK and promoting EGO, may be an effective strategy for improving sport cognition in adolescent athletes.

limitations

In this study, we did not directly measure the specific duration of training that adolescent athletes spent with their current coaches, which represents a limitation of our work. We acknowledge that this variable could provide a more nuanced understanding of our results. The duration of the relationship between adolescent athletes and their coaches is indeed a significant factor influencing perceived care, as longer relationships foster deeper emotional bonds and mutual understanding. Future research should incorporate this variable to distinguish the effects of relationship length from those of relationship quality. The fitted indices in this study are lower than generally accepted standards but remain within an acceptable range. Future research should place greater emphasis on optimizing the model to achieve higher fitted indices. The study sample was skewed toward handball athletes (54% of the total), and constrained by China’s competitive classification system. Future research should include athletes from different sports, countries, or competitive systems to enhance the generalizability of findings. The limitation of this study lies in the potential risk of common method bias. Although supplementary analyses supported the robustness of the core findings, the cross-sectional design and reliance on a single self-report questionnaire mean we cannot completely exclude the inflationary effect of methodological bias on the strength of correlations between variables. Therefore, the correlation coefficients and model path coefficients in this study should be interpreted as upper bounds for the associations between variables. Future research should employ longitudinal designs and multi-source data (e.g., integrating coach evaluations and objective behavioral metrics) to fully address this issue. It should be noted that the slight exceedance of ΔCFI in measurement invariance suggests that one or more items of the scale may exhibit subtle functional differences across different groups, providing direction for further optimization in future research.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study is available via the supplementary attachment.

References

Adie JW, Duda JL, Ntoumanis N (2008) Achievement goals, competition appraisals, and the psychological and emotional welfare of sport participants. J Sport Exerc Psychol 30(3):302–322. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.30.3.302

Allen JB, Howe BL (1998) Player ability, coach feedback, and female adolescent athletes’ perceived competence and satisfaction. J Sport Exerc Psychol 20(3):280–299. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.20.3.280

Amorose AJ, Anderson-Butcher D (2007) Autonomy-supportive coaching and self-determined motivation in high school and college athletes: a test of self-determination theory. Psychol sport Exerc 8(5):654–670

Appleton PR, Hall HK, Hill AP (2011) Examining the influence of the parent-initiated and coach-created motivational climates upon athletes’ perfectionistic cognitions. J Sports Sci 29(7):661–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.551541

Arribas-Galarraga S, Cos IL, Cos GL, Urrutia-Gutierrez S (2020) Mediation effect of perceived fitness on the relationship between self-efficacy and sport practice in Spanish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):8800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238800

Atkins MR, Johnson DM, Force EC, Petrie TA (2014) Peers, parents, and coaches, oh my! The relation of the motivational climate to boys’ intention to continue in sport. Psychol Sport Exerc 16:170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.10.008

Barrett P (2007) Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit Personality and Individual Differences 42(5):815–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018

Chen D, Ma X, Dong J (2022) Technical diagnosis on elite female discus athletes based on Grey relational analysis. Comput Intell Neurosci 2022:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8504369

Csajbók Z, Sieber S, Cullati S, Cermakova P, Cheval B (2022) Physical activity partly mediates the association between cognitive function and depressive symptoms. Transl Psychiatry 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02191-7

Davis L, Jowett S, Lafrenière MK (2013) An attachment theory perspective in the examination of relational processes associated with Coach-Athlete dyads. J Sport Exerc Psychol 35(2):156–167. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.35.2.156

Davis L, Appleby R, Davis P, Wetherell M, Gustafsson H (2018) The role of coach-athlete relationship quality in team sport athletes’ psychophysiological exhaustion: implications for physical and cognitive performance. J Sports Sci 36(17):1985–1992. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1429176

Domaradzki J, Popowczak M, Zwierko T (2021) The mediating effect of change of direction speed in the relationship between the type of sport and reactive agility in elite female team-sport athletes. J Sports Sci Med 699–705. https://doi.org/10.52082/jssm.2021.699

Dong DL (2007) The preliminary establishment and analysis on exercise cognitive level of psychological evaluation scale. J Sports Sci 27(11):25–29. https://doi.org/10.16469/j.css.2007.11.008

Duda JL (2013) The conceptual and empirical foundations of Empowering CoachingTM: setting the stage for the PAPA project. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol 11(4):311–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197x.2013.839414

Duda JL, Nicholls JG (1992) Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. J Educ Psychol 84(3):290–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.290

Dunn JC (2000) Goal orientations, perceptions of the motivational climate, and perceived competence of children with movement difficulties. Adapt Phys Act Q 17(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.17.1.1

Dweck CS (1986) Motivational processes affecting learning. Am Psychol 41:1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.41.10.1040

Elliot AJ, Church MA (1997) A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J Personal Soc Psychol 72(1):218–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.218

Friesen A, Lane A, Galloway S, Stanley D, Nevill A, Ruiz MC (2017) Coach–Athlete perceived congruence between actual and desired emotions in karate competition and training. J Appl Sport Psychol 30(3):288–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1388302

Fry MD, Gano-Overway LA (2010) Exploring the contribution of the caring climate to the youth sport experience. J Appl Sport Psychol 22(3):294–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413201003776352

Gao Z, Xiang P, Harrison L, Guan J, Rao Y (2008) A cross-cultural analysis of achievement goals and self-efficacy between American and Chinese College students in Physical Education. Int J Sport Psychol 39(4):312–328. https://experts.umn.edu/en/publications/a-cross-cultural-analysis-of-achievement-goals-and-self-efficacy

Gjesdal S, Stenling A, Solstad BE, Ommundsen Y (2018) A study of coach‐team perceptual distance concerning the coach‐created motivational climate in youth sport. Scand J Med Sci Sports 29(1):132–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13306

Isoard-Gautheur S, Trouilloud D, Gustafsson H, Guillet-Descas E (2015) Associations between the perceived quality of the coach–athlete relationship and athlete burnout: an examination of the mediating role of achievement goals. Psychol Sport Exerc 22:210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.08.003

Jakobsen AM (2021) The relationship between motivation, perceived motivational climate, task and ego orientation, and perceived coach autonomy in young ice hockey players. Balt J Health Phys Act 13(2):79–91. https://doi.org/10.29359/bjhpa.13.2.08

Jin H, Kim S, Love A, Jin Y, Zhao J (2022) Effects of leadership style on coach-athlete relationship, athletes’ motivations, and athlete satisfaction. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1012953

Jung KI (2014) The mediation effects of achievement goals on the relations between coaching behaviors and exercise adherence perceived by adolescent players. J Korean Acad Kinesiol 16(4):1–11. https://doi.org/10.15758/jkak.2014.16.4.1

Kim I, Lee K, Kang S (2019) The relationship between passion for coaching and the coaches’ interpersonal behaviors: the mediating role of coaches’ perception of the relationship quality with athletes. Int J Sports Sci Coach 14(4):463–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954119853104

Lei H, Xu GG, Shao ZY et al (2015) The relationship between teacher caring behaviors and students’ academic performance: the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Psychol Dev Educ 31(2):188–197

Marsh HW, Hau K-T, Wen Z (2004) In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-Testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff Values for Fit Indexes and Dangers in Overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's (1999) Findings Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 11(3):320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

Newton M, Detling N, Kilgore J, Bernhardt P (2004) Relationship between achievement goal constructs and physical self-perceptions in a physical activity setting. Percept Mot Skills 99(3):757–770. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.99.3.757-770

Nicholls JG (1989) The competitive ethos and democratic education. Choice Rev Online 27(02):27–1049. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.27-1049

Pensgaard AM, Roberts GC (2002) Elite athletes’ experiences of the motivational climate: the coach matters. Scand J Med Sci Sports 12(1):54–59. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0838.2002.120110.x

Putnick DL, Bornstein MH (2016) Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: the state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev Rev 41:71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004

Roberts GC, Ommundsen Y (1996) Effect of goal orientation on achievement beliefs, cognition and strategies in team sport. Scand J Med Sci Sports 6(1):46–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.1996.tb00070.x

Seanor M, Schinke RJ, Stambulova NB, Henriksen K, Ross D, Giffin C (2019) Catch the feeling of flying: guided walks through a trampoline Olympic development environment. Case Stud Sport Exerc Psychol 3(1):11–19. https://doi.org/10.1123/cssep.2019-0002

Sheldon KM, Krieger LS (2007) Understanding the Negative Effects of Legal Education on Law Students: A Longitudinal Test of Self-Determination Theory Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33(6):883–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207301014

Tomczak M, Kleka P, TomczakŁukaszewska E, Walczak M (2024) Hope for success as a mediator between big five personality traits and achievement goal orientation among high performance and recreational athletes. PLoS ONE 19(3):e0288859. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288859

Tomczak M, Walczak M, Kleka P, Walczak A, Bojkowski (2020) Psychometric properties of the Polish version of task and ego orientation in sport questionnaire (TEOSQ). Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(10):3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103593

Vallerand RJ, Ratelle CF (2002) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: A hierarchical model. In EL Deci & RM Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 37–63). University of Rochester Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2002-01702-002

Wang JCK, Morin AJS, Liu WC, Chian LK (2016) Predicting physical activity intention and behaviour using achievement goal theory: a person-centered analysis. Psychol Sport Exerc 23:13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.10.004

Wang X, Sun Z, Yuan L, Dong D, Dong D (2024) The association between team behaviors and competitive anxiety among team-handball players: the mediating role of achievement goals. Front Psychol 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1417562

Wang Y, Huang Q, Wang Q, Xun Y, Tan Y, Cui S, Ma L, Huang P, Cao M, Zhang B (2021) Analysis of the structural characteristics of the online social network of Chinese professional athletes. Complexity 2021(1). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6647664

Weiss MR, Amorose AJ, Wilko AM (2009) Coaching behaviors, motivational climate, and psychosocial outcomes among female adolescent athletes. Pediatr Exerc Sci 21(4):475–492. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.21.4.475

Weltevreden GM, Van Hooft EA, Van Vianen AE (2018) Parental behavior and adolescent’s achievement goals in sport. Psychol Sport Exerc 39:122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.004

Williams L, Gill DL (1995) The role of perceived competence in the motivation of physical activity. J Sport Exerc Psychol 17(4):363–378. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.4.363

Xiang P, Lee A (2002) Achievement goals, perceived motivational climate, and students’ self-reported mastery behaviors. Res Q Exerc Sport 73(1):58–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2002.10608992

Xiang P, Lee AM, Solmon MA (1997) Achievement goals and their correlates among American and Chinese students in physical education: a cross-cultural analysis. J Cross-Cult Psychol 28:645–660

Xiang P, Lee A, Shen J (2001) Conceptions of ability and achievement goals in physical education: comparisons of American and Chinese students. Contemp Educ Psychol 26(3):348–365. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2000.1061

Yang N, Quan H, Guo Z (2024) The influence of motivational climate on the physical activity adherence among junior high school students: the mediating effect of achievement goal orientation. PLoS ONE 19(12):e0315831. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0315831

Zhang F (2017b) Research on the cultivation of Chinese competitive sports reserve talents based on the theory of Multiple Intelligences. In: Advances in social science, education and humanities research (ASSEHR), vol 93. https://doi.org/10.2991/cetcu-17.2017.42

Zheng Q, Wang L (2021) Teammate conscientiousness diversity depletes team cohesion: the mediating effect of intra-team trust and the moderating effect of team coaching. Curr Psychol 42(8):6866–6876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01946-7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pengyu Lin: Conceptualization, methodology, software, writing-original draft preparation and formal analysis, software and methodology, methodology and editing, Investigation and data curation. Delong Dong: Conceptualization, validation, writing-original draft preparation and funding acquisition. Investigation, funding acquisition, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This work involved human subjects or animals in its research. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies involving humans were approved by Ludong University Ethics Committee. (Ethics approval number: LDU-IRB202311002; Approval Date: December 15, 2023). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Informed consent

July 2024 through the end of the month, informed consent was obtained from participants prior to their completion of questionnaires at any study time point. As participants were minors, all questionnaires were completed anonymously and voluntarily, following parental consent. Participants voluntarily agreed to participate in the study after being fully informed that their anonymity would be protected, that data would be used solely for research purposes, and that there were no risks associated with participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, P., Dong, D. The predict of coaches’ care on the sports cognitive level of adolescent athletes: the indirect association of achievement goals. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 104 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06325-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06325-2