Abstract

This study explores the mechanism of the effect of algorithm literacy of Chinese academic library users on the attitude towards using library intelligent chatbots. The mixed research paradigm of convergent design is drawn upon by this study, a research model based on the Technology Acceptance Model and perceived risk theory is constructed, and questionnaire data and interview data are collected for analysis. There are three findings. First, the algorithm literacy of users themselves and the perception formed in the process of contact with library intelligent chatbots are important factors affecting their attitude towards use. Second, the effect of algorithm literacy on attitude is mediated by perceived efficiency and perceived risk. Lastly, People with higher algorithm literacy may hold more positive attitudes toward intelligent chatbots. This study reveals how algorithm literacy influences users’ interactions with AI technology, providing a novel perspective for the study of library intelligent chatbots usage. Practically, this study offers references and insights on effectively applying users’ algorithm literacy to enhance chatbots user acceptance and service quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) greatly changed people’s lifestyles and is widely applied in academic libraries. As a significant application of AI technology in the development of academic libraries, intelligent chatbots offer efficient and proactive interactive services to readers around the clock (Li and Coates, 2024; Panda and Chakravarty, 2022). They are changing the pattern of library and information services (Aboelmaged et al., 2024). Academic libraries can successfully develop and train AI chatbots, such as Engati (Panda and Chakravarty, 2022), Bcpylib (Thalaya and Puritat, 2022) and “Xiao Tu” of Tsinghua University. However, in stark contrast to the rapid advancement of AI technology, users’ attitudes towards these AI systems vary widely. The adoption rate of intelligent chatbots in libraries is relatively low (Guy et al., 2023; Twomey et al., 2024). A survey of 1035 Chinese librarians revealed that only 36.81% reported their libraries had adopted intelligent chatbots (Zhao et al., 2025). This lag in technology adoption requires deeper investigation. The success of technology implementation largely depends on whether end users are willing to accept and use it. Therefore, in the library context, understanding how users perceive and interact with intelligent chatbots is essential for improving adoption rates. There is considerable interest in the application of chatbots in libraries (Allison, 2012; Panda and Chakravarty, 2022). But the motivation for users to use such tools has only been explored within a limited scope.

Some studies have employed the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to explore the influencing factors of accepting intelligent chatbots (Awal and Haque, 2024; Bilquise et al., 2024; Pillai et al., 2024). For example, one study investigated users’ attitudes toward academic advising chatbots. All the respondents have indicated an average to a good experience with technology (Bilquise et al., 2024).

However, the library chatbots are designed to assist users with specific queries related to library resources and services. They aim to provide targeted and efficient support. Additionally, Ordinary users’ fear of technology, distrust stemming from the opacity of algorithm operations, and the potential learning burden. These factors may all influence their acceptance of intelligent chatbots (Bohle, 2018). Algorithm literacy may influence people’s views on artificial intelligent system (Shin et al., 2022), but it has not been integrated into the TAM. Algorithm have become commonplace in our life. Algorithmic literacy plays a crucial role in academic library education (Archambault et al., 2024). Therefore, adopting a new framework to explore the role of user algorithm literacy in shaping attitudes towards library intelligent chatbots is of great importance. This can effectively supplement the deficiencies in empirical research on chatbot user experience in the development of academic library. This study addressed the following two questions:

RQ1: How does algorithm literacy among academic library users shape their attitudes towards intelligent chatbots?

RQ2: What is the impact of demographic characteristics on various variables (such as algorithm literacy, user perception, and attitudes towards library intelligent chatbots usage)?

Literature review

Library intelligent chatbots

Currently, research on library chatbots is still in the early exploratory stage (Yan et al., 2023). Most studies primarily focused on the theoretical exploration of service functions (Adetayo, 2023; Sanji et al., 2022), system development and implementation (Ehrenpreis and DeLooper, 2022; Panda and Chakravarty, 2022; Rodriguez and Mune, 2022; Thalaya and Puritat, 2022) and application case analysis in intelligent service scenarios (McKie and Narayan, 2019; Vincze, 2017). Existing research primarily emphasizes technical implementation and functional design. These studies provide practical cases. However, exploration of user acceptance and usage behavior remains notably insufficient.

Research on the factors influencing the use of intelligent chatbots in libraries is relatively limited. Kaushal and Yadav (2022) have explored user experiences and usage motivations using qualitative methods. Their findings indicated that everyone was also concerned about the numerous risks this adoption would bring. Wang et al. (2023a) have empirically studied the influencing factors of user behavior based on the functions and social characteristics of robots. It was found that user trust significantly influences user adoption behaviors Safadel et al. (2023) found that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use influenced people’s intentions to use library virtual chatbots. The literature shows no scholars have yet studied attitudes towards the use of intelligent chatbots in libraries from the perspective of user literacy. To further enrich understanding of users’ motivations for adopting library AI chatbots, this study employs a mixed-methods approach for analysis.

Algorithm literacy

Algorithm literacy refers to an individual’s ability to understand, evaluate, and apply algorithms. It is a potential factor influencing users’ attitudes towards the use of intelligent systems (Deng et al., 2023). Algorithm literacy first requires individuals to be aware of the existence of algorithms, understand their significant influence (Swart, 2021), and be able to infer the functions of algorithms (Rieder, 2017; Dogruel et al., 2022). Secondly, there is a need for critical evaluation of algorithmic decisions and skills to address or even influence algorithmic operations (Koenig, 2020). Simultaneously, we must emphasize the importance of algorithmic social norms. This helps address and prevent negative impacts of algorithms. Accordingly, this study follows Deng (2023) research. It divides algorithm literacy into algorithm awareness (AA), algorithm knowledge (AK) and skills, critical thinking (CT) and algorithm social norms (ASN) for further study.

In the field of intelligent chatbots applications, algorithm literacy includes a fundamental understanding of technology. It also covers an awareness of how algorithms process personal data and deliver personalized services. This highlights the importance of AI literacy including algorithm literacy (Archambault et al., 2024; Kim, 2023). This positions algorithm literacy as a critical dimension in assessing and explaining users’ attitudes towards intelligent chatbots. Especially in the transition of library services from informatization and digitalization to intelligent and smart systems, the importance of algorithm literacy is self-evident (Archambault et al., 2024; Wu D., 2022).

Academia has paid attention to the role of user qualities in the adoption of digital technologies. Most studies focused on information literacy (Nikou et al., 2022), and health literacy (Yi-No Kang et al., 2023) and digital literacy (Cetindamar et al., 2021). It remains unclear how algorithm literacy influences users’ attitudes towards technology use. Existing research on algorithm literacy primarily focuses on its connotations of algorithm literacy (Archambault et al., 2024; Xia et al., 2023), scale design (Dogruel et al., 2022), and the development of evaluation systems (Deng et al., 2023). But there is a lack of systematic research on the mechanism between algorithm literacy and users’ attitudes towards using intelligent chatbots. So, it is necessary to study the factors influencing the use of intelligent chatbots by academic library users from the perspective of algorithm literacy.

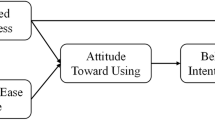

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

The TAM is a theory proposed by Davis (1989) to explain user technology usage behavior. TAM emphasizes that users’ perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of new technology directly influence their attitude towards using the new technology, and further affect their behavior. TAM has been validated through numerous empirical studies. It demonstrates good predictive power in various contexts, such as health information technology acceptance behavior (Yi-No Kang et al., 2023) and shared electric bicycle adoption intentions (Pan et al., 2022). However, technological environments continue to develop. User needs are also becoming more diverse. Relying solely on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use may not fully explain users’ technology acceptance behavior.

In terms of AI device adoption, Dahri et al. (2024) integrated factors such as perceived AI trust and perceived AI capability into the TAM to study ChatGPT usage behavioral intentions. Ezeudoka and Fan (2024) studied the influence of factors such as trust and performance expectancy on e-pharmacy usage behavior, extending the TAM. These new factors demonstrate strong explanatory power for users’ AI device usage behavior.

This study will take this model and incorporate perceived trust, perceived risk (PR), and perceived efficiency (PE) as mediating variables. It examines the relationship between users’ algorithmic literacy and their perception and usage attitudes towards academic library intelligent chatbots. This relationship has been largely overlooked in prior literature.

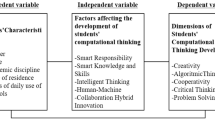

Theoretical foundation and hypotheses development

Existing literature supports the feasibility of adopting TAM. Safadel et al. (2023) applied TAM to study factors influencing intelligent library chatbots. So, TAM is employed as the theoretical framework for this study. The framework includes four cognitive variables. They are algorithm knowledge and skills (AK), AA, CT, ASN. The framework also contains three perceptual variables and one dependent variable. They are PR, perceived distrust (PD), PE and attitude towards usage (UA). Additionally, gender, age, education, and involvement in algorithm-related work are considered as control variables. Figure 1 explains the study’s proposed research model.

Perceived efficiency and perceived distrust

Within the TAM framework, users are more inclined to use technologies they believe will improve work efficiency and quality of life. Previous studies show that PE significantly predicts an individual’s behavior intention to AI of library (Yang et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2016).

Furthermore, trust is a key psychological factor driving user acceptance and use of technology. Empirical research results by Eren (2023) and Wang et al. (2023a) show that trust is the most important factor affecting the willingness to use robotic advisors.

Accordingly, this study proposing the following hypotheses:

H1: Users who perceive higher efficiency associated with library intelligent chatbots will exhibit a more positive attitude towards their use.

H2: Users who perceive higher levels of distrust associated with library intelligent chatbots will exhibit a more negative attitude towards their use.

Perceived risk theory (PRT)

The PRT describes consumers’ assessment of potential negative outcomes before purchasing products or services (Barach, 1969). Scholars in the field of information systems point out that PR significantly influences individual adoption of technology (Kesharwani and Singh Bisht, 2012; Im et al., 2008).

The AI technologies and algorithms employed by chatbots are like a “black box” to users. The potential risks faced by users may include privacy breaches, data security, and the risk of erroneous information (Featherman and Pavlou, 2003). Users of library intelligent chatbots may perceive high risks, such as concerns about mishandling sensitive information. They might also worry about receiving inaccurate information that could lead to incorrect decisions. These risk perceptions can negatively influence their attitude towards using the technology (Kaushal and Yadav, 2022).

PR also includes users’ concerns about the consequences of technology failure, such as service interruptions and poor user experience (Trivedi, 2019). If users prioritize these risks over the anticipated benefits of the technology, their attitudes may turn negative. This shift in attitude stems from worries about possible negative outcomes.

Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: Users who perceive higher risks associated with library intelligent chatbots will exhibit a more negative attitude towards their use.

Algorithm literacy

The cultivation of algorithm literacy can help people recognize the potential risks of algorithms and improve their ability to prevent and combat these risks. Xu and Cheng (2022) found that many users are ignorant about algorithms but hold negative evaluations. In contrast, digital natives with higher algorithm cognition perceive fewer algorithmic risks. Most users are unaware of how these platforms operate in daily life (Cheney-Lippold, 2011). If they knew, users would become increasingly concerned about the impact of these algorithmic platforms on our daily interactions (Just and Latzer, 2017). It can be hypothesized that when users have higher algorithm literacy, they will perceive lower risks from intelligent chatbots.

Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H4a: Users with higher levels of algorithm knowledge and skills will perceive lower risks associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H5a: Users with higher levels of algorithm awareness will perceive lower risks associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H6a: Users with higher levels of critical thinking will perceive lower risks associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H7a: Users with higher levels of algorithm social norms will perceive lower risks associated with library intelligent chatbots.

Trust is a construct that describes the perception or belief that people, organizations, or technologies are credible, trustworthy, and reliable (Winkler and Söllner, 2018). It is a crucial factor in establishing and maintaining effective interactions with robots. PD in this study refers to users’ lack of trust in intelligent chatbots. Swart (2021) argues that understanding and mastering algorithm-related knowledge can lead individuals from negative emotions and distrust to positive emotions and appreciation of technology. Research has shown that individual algorithm literacy affects their trust in robots (Montal and Reich, 2017).

Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H4b: Users with higher levels of algorithm knowledge and skills will perceive lower levels of distrust associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H5b: Users with higher levels of algorithm awareness will perceive lower levels of distrust associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H6b: Users with higher levels of critical thinking will perceive lower levels of distrust associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H7b: Users with higher algorithm social norms will perceive lower levels of distrust associated with library intelligent chatbots.

PE refers to an individual’s subjective assessment of the efficiency improvement brought by a certain technology, tool, or service (Moon and Lee, 2022). Petrič et al. (2017) found that mastery of modern information technology knowledge contributes to enhancing PE. Yi-No Kang et al. (2023) examined digital literacy and health promotion knowledge significantly influence the PE of AI. Algorithm literacy improves users’ comprehension of how intelligent chatbots operate, helping them assess the efficiency benefits, potentially influencing their motivation and usage frequency of this technology. Therefore, algorithm literacy directly influences users’ perception of the extent to which intelligent chatbots enhance information retrieval and service efficiency, potentially promoting their broader adoption.

Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H4c: Users with higher levels of algorithm knowledge and skills will perceive higher efficiency associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H5c: Users with higher levels of algorithm awareness will perceive higher efficiency associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H6c: Users with higher levels of critical thinking abilities will perceive higher efficiency associated with library intelligent chatbots;

H7c: Users with higher levels of algorithm social norms will perceive higher efficiency associated with library intelligent chatbots.

Research methodology and design

Mixed research methods enable both quantitative analyses to understand the effects between constructs and qualitative analysis to grasp the contextual conditions and details of variable interactions (Harrison and Reilly, 2011). This study conducts an exploratory investigation into how algorithm literacy influences attitudes toward using library intelligent chatbots. It employs a mixed research method, primarily using questionnaire surveys supplemented with semi-structured interviews. Convergent design is a type of mixed research method. This study draws on this paradigm to collect qualitative and quantitative results, continuously converging, interpreting, and refining the research findings from both group and individual perspectives. Specifically, Quantitative research validates the influence paths between variables using TAM. Qualitative research captures contextual details of users’ technology acceptance processes.

This study focuses on library intelligent chatbots. These chatbots are an important part of library digital transformation. They use AI technology to provide users with instant, personalized information services. They typically offer functions such as: resource retrieval and recommendation, frequently asked questions answering, and borrowing management assistance. Figure 2 shows the intelligent chatbot interface of Shaanxi Normal University Library. On the left side, there are two tabs: “Common Questions” and “Self-service”. Under “Common Questions”, several subcategories appear as clickable buttons, such as “Electronic Resource Classification”, “Circulation Reading Service”, and others. Below these buttons, a list of frequently asked questions is provided. The right side demonstrates the interactive solution. A user asks, “Where can I find the database of modern newspapers purchased by the school?” The intelligent robot responds with a detailed thinking process. It mentions checking the database introduction. Finally, it provides the user with the address of the needed database.

Questionnaire survey

To ensure the reliability and validity of variables, measurement items are developed using an adaptive approach. We selected validated scales from existing literature and made context adjustments for library intelligent chatbots (Table 1). The questionnaire comprises 39 items (See Table 3 for the study’s instrument). All variables are measured using a five-point Likert scale. During the scale development process, we invited two experts from the Library and Information Science field to review our initially adapted scales. These experts have over 8 years of experience in library information systems research and provided professional assessment of the content validity and applicability of the scales.

The survey was pre-tested with 30 library chatbots users from August 20th to 22nd, 2023. Based on the pre-test feedback, we made several adjustments to enhance the questionnaire’s comprehensibility. These included terminology optimization (e.g., changing “algorithms have opacity and low explainability” to “algorithms have opacity and explainability, which makes me feel anxious”) and structural adjustments to improve logical coherence. After these modifications, the experts reviewed the questionnaire again to ensure its scientific rigor and comprehensibility.

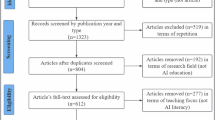

The questionnaire targeted active library service users including undergraduate/graduate students, faculty members, and personnel from research institutions with algorithm experience (Table 2). Most participants were between 18 and 32 years old. University students represented the highest proportion. The higher percentage of females in our sample is consistent with existing research findings. Several studies have shown that female users generally exhibit higher frequency in using library information services compared to male users (Applegate, 2008; Halder et al., 2010). This reflects the characteristics of academic library readership, which is dominated by young readers and student readers. These survey participants were recruited through social media platforms (campus platforms, professional communities, etc.). Before completing the survey, participants were shown an introduction to library intelligent chatbots. They also viewed the interaction process between users and these chatbots. Experience links were provided to ensure they had sufficient understanding of the technology. The final version of the questionnaire was distributed online through social media from September 5 to October 10, 2023. We received 281 responses. After removing incomplete and invalid responses, 239 valid submissions remained. This sample size exceeds six times the number of measured items (Zeng et al., 2009), meeting the requirements for PLS-SEM analysis.

Semi-structured interview

Unlike the random sampling used in the quantitative research, the semi-structured interviews employed purposive sampling, deliberately selecting representative interviewees. The interviewees mainly consist of users experienced with library intelligent chatbots usage, with a total of 8 participants, including 4 males and 4 females. The participants include university students and working professionals. The student group consists of 2 undergraduates and 4 graduate students. They come from computer science, library science, and communication majors. The professional group includes 2 individuals working in research institutions. Their ages range from 20 to 32 years. All participants have algorithm experience, varying from basic to advanced levels. Their usage frequency ranged from occasional consultation to regular interaction for research assistance. A semi-structured interview guide was developed based on research hypotheses and observed variables. The interviews were conducted online from August 26–29, 2023, and a total of 8 interview transcripts were collected and transcribed for research analysis (subsequently referred to as I1 to I8 representing the 8 interviewees).

Common method bias and multicollinearity test

Common method bias can lead to incorrect judgments about the adequacy of scale reliability and convergence effectiveness (Jordan and Troth, 2020). Therefore, this study used SPSS to conduct Harmon’s single-factor test on the scale. The results extracted 6 factors with characteristic roots greater than 1, and the variance contribution rate of the first common factor was 39.26%, which did not exceed 40%, indicating that this study does not suffer from severe common method bias issues. Additionally, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to test for multicollinearity. The results showing VIF values ranging from 1.000 to 3.23, below the threshold of 3.3, indicating no serious multicollinearity issues in the data.

Reliability and validity of the instrument

This study conducted validity and reliability tests on the model using SmartPLS (Table 3). The estimated SRMR value of the model is 0.064, which is less than the standard of 0.08, indicating good model fit and acceptable adequacy. Alpha values for each variable range from 0.771 to 0.932, all greater than 0.7, indicating good internal consistency of the variables and high questionnaire reliability.

In terms of convergent validity, the standardized factor loadings of all observed variables are greater than 0.7, the composite reliabilities (CR) of all latent variables are greater than 0.7, and the average variance extracted (AVE) is higher than 0.5, meeting the requirements for convergent validity. The Fornell-Larcker criterion is used to test discriminant validity (Table 4). The results show that the square roots of the AVE for all latent variables are greater than the correlations with other latent variables, indicating good discriminant validity of the measurement model.

Data analysis and research findings

Quantitative analysis results

The results of the direct path analysis reveal that users’ AK and skills reduce PR (β = −0.366, P < 0.01) and distrust (β = −0.302, P < 0.05). Thus, H4a and H4b are supported. Users’ AA enhances PE (β = 0.300, P < 0.01). Thus, H5c is supported. ASN significantly positively influence PE (β = 0.223, P < 0.01). Thus, H7c is supported. Additionally, PR decreases user attitudes towards using library chatbots (β = −0.262, P < 0.01), while PE enhances them (β = 0.550, P < 0.001). Thus, sH1 and H3 are supported. However, PD does not significantly negatively affect attitudes towards use. Thus, H2 is not supported.

Overall, the model explains 33.8% of PR variance, 26.1% of PD variance, 35.1% of PE variance, and 38.7% of library chatbots usage attitude variance (Fig. 3).

The findings reveal important mediation effects. Algorithm literacy in various domains has indirect impacts on library chatbot usage attitudes. These impacts occur through PR and efficiency. There was no significant indirect effect of algorithm literacy on library chatbots attitudes via PD towards the chatbots (Table 5).

The results indicate the influence of control variables on each variable (Table 6). Age correlates positively with AK and skills (β = 0.315, P < 0.001), AA (β = 0.199, P < 0.05), and CT (β = 0.271, P < 0.001), while negatively correlating with PR (β = −0.406, P < 0.001) and PD (β = −0.345, P < 0.001). However, gender did not significantly affect any of the variables.

Using non-algorithm-related workers as the reference group, those in algorithm-related occupations exhibited higher levels of algorithm literacy, including AK and skills (β = −0.331, P < 0.001), AA (β = −0.198, P < 0.001), CT (β = −0.221, P < 0.001), and ASN (β = −0.187, P < 0.001).

Qualitative analysis results

According to the requirements of convergent design paradigm, further qualitative analysis is needed to explore more detailed and in-depth findings. Therefore, this study starts from both cognitive and perceptual perspectives. It further understands the interaction between algorithm literacy and the usage attitude of library intelligent chatbots. This enriches the understanding of how algorithm literacy influences the usage attitude towards library intelligent chatbots.

Theme 1: Algorithmic Literacy Serves as the Key Cognitive Foundation for Users to Evaluate and Accept Library Intelligent Chatbots.

Algorithm Knowledge and Skills: Users focus on chatbot operational mechanics and programming. “I care about how the algorithm works behind it, which determines whether I trust it (I1).” “After understanding its basic working principles, my concerns decreased significantly (I3)”.

AlgorithmAwareness: Most users have a first impression of algorithms as quick and convenient. “When I first used it, I felt it was very convenient, no need to queue for human service (I4).” “It responds to my questions immediately. this instantaneity was what I noticed first (I7)”.

Critical Thinking: Users believe dialectical thinking encourages self-reflection and rational usage attitudes. “I consider whether its answers are reasonable rather than blindly accepting them (I2)”.

Algorithm Social Norms: Users’ awareness of algorithmic social norms affects their expectations and satisfaction. “Those unfamiliar with AI ethical norms often have unrealistic expectations of chatbots, leading to dissatisfaction when these expectations aren’t met (I5).”

Theme 2: Efficiency Advantages Outweigh Trust Deficits.

Perceived distrust: All interviewees expressed higher trust in human services, especially for handling complex issues. “For complex research questions, I still trust professional librarians more (I3).” However, despite this distrust, users still choose to use chatbots. “While I don’t fully trust its answers, it’s sufficient for basic queries (I2).” Social factors also influence this choice. “Sometimes I don’t want to interact with people. Asking questions through a chatbot feels more comfortable (I7).” Time efficiency is also an important consideration. “Waiting for librarian responses is sometimes too slow (I8)”.

Perceived efficiency: Time and space flexibility are highly valued. “It can search the entire database in seconds, a speed human can’t match (I1).” Users also appreciate the guidance function. “I like how it guides me to narrow down my search step by step, which is much more efficient than figuring it out myself (I4).” “Not having to worry about library closing times and getting help anytime is important for my research progress (I6)”.

Theme 3: User Risk Assessment is Based on Multiple Dimensions Rather Than Single Technical Characteristics.

Concerning PR, users consider multiple factors in their assessment. Interface design affects trust. “If the interface looks professional, I feel safer (I8).” Privacy issues are common concerns. “I worry it might record my search history, which raises privacy concerns (I2).” Functional performance also influences risk assessment. “When it accurately answers my specialized questions, my risk assessment decreases (I4).” Institutional endorsement increases credibility. “I check whether the school officially recommends using this system, which affects my judgment of its safety (I5)”.

Discussion and recommendations

This study investigated the influence mechanism of algorithm literacy on users’ attitudes towards using library intelligent chatbots. It finds that algorithmic literacy has a positive effect on library intelligent chatbots acceptance. Based on this, gender, age, educational level, and algorithm-related work are defined as control variables to explore their impact on various variables. The main conclusions are as follows:

In the process of users interacting with library intelligent chatbots, their cognitive level significantly impacts factors such as PR, PE, and PD. The quantitative analysis results show that users’ AK and skills significantly reduce the degree of PR and PD, while AA significantly improves PE. This means that users with higher cognitive levels and more knowledge and skills related to algorithms have relatively higher trust in intelligent chatbots and perceive lower risks. Additionally, ASN positively influence users’ PE of library intelligent chatbots. Interview data also show that users believe ASN affect their perceptions of the limitations, practicality, and functional limits of chatbots, thereby influencing efficiency perception. This result confirms the view of Xia et al. (2023) that the level of algorithm literacy affects individuals’ interactions with AI chatbots representing algorithms. Therefore, improving and enhancing algorithm literacy is important to improving the quality of user interactions with intelligent technology.

Users’ attitudes towards using library intelligent chatbots are closely related to their perceived levels of risk and efficiency. The survey results indicate that users have a high demand for chatbots efficiency, including expectations for convenient, “24/7” service, and PE has a significant path coefficient in the attitude influence model. Users’ PE of intelligent chatbots directly determines their acceptance (Yi-No Kang et al., 2023). Simultaneously, user experience uncertainties are also considered, including PRs regarding service performance and data security. These PRs negatively impact usage attitudes, consistent with PR influence studies in other fields like online healthcare (Wang et al., 2023b). Users’ core expectation of library intelligent chatbots is to quickly and accurately obtain answers to their questions. This reflecting a preference for chatbots services that provide precise, comprehensive, and rapid responses.

Trust plays a key role in adopting AI-driven educational technology for learning (Nazaretsky et al., 2025). However, our research reveals users’ PD does not significantly impact their usage attitudes. This finding contrasts with some existing literature. It suggests that in specific contexts, other factors may be more important than distrust. Qualitative research results reveal that users want to explore new technology. This curiosity-driven behavior may offset the negative effects of distrust. Secondly, chatbots offer a way to get library services without social pressure. This benefit may be more important to them than their distrust of the technology. Finally, the efficiency of chatbots is a key factor. Users value the quick and convenient service. When they see that chatbots can solve their problems quickly, this advantage may reduce the impact of distrust on their attitude toward using the technology.

The study shows that algorithm literacy affects user attitudes through the mediating variables of PE and PR Users with higher algorithm literacy tend to hold more positive attitudes toward intelligent chatbots. This finding aligns with the research of Shin et al. (2022), where users with higher algorithm literacy, due to their deeper understanding and recognition of algorithms. They recognize the potential and benefits of algorithms more clearly. As a result, they are more likely to actively choose algorithmic systems to solve problems and enhance efficiency Users engaged in algorithm work also find the chatbot’s data rich and concise, and prefer the chatbots (I8). These results indicate a significant association between algorithm literacy and technology acceptance/use. They provide a foundation for future research to further explore and validate the impact of algorithm literacy. Additionally, the mixed research results of this study indicate that the impact of perceived factors on user attitudes varies based on cognitive factors. This finding aligns with the core argument of the TAM. The attitude of individuals or organizations towards new technology is determined by their evaluation of different perceived factors (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Algorithm literacy is related to demographic characteristics such as individual age and experience in algorithm-related work. This conclusion aligns with the view of Trepte et al. (2015) that an individual’s literacy is closely related to their demographic attributes, cognitive factors, and even motivational factors. Quantitative research results reveal that age is positively correlated with algorithm literacy, which contrasts with the findings of Dogruel et al. (2022). The discrepancy may stem from differences in sample age structure. This study’s sample mainly focuses on the 18-32 age range, possibly reflecting that within this specific age range, algorithm literacy increases with age. Future research should consider expanding the sample range to further explore the relationship between algorithm literacy and age. Meanwhile, individuals engaged in algorithm-related work exhibit higher algorithm literacy and tend to have a more positive attitude towards library intelligent chatbots. Users with an algorithm background usually have a deeper understanding of algorithms and superior programming skills This enables them to more comprehensively recognize the advantages and limitations of intelligent chatbots. Therefore, individuals with an algorithm background are more likely to endorse the application of intelligent chatbots and use their services more effectively.

Additionally, the results of this study show that individual algorithm literacy does not have a significant correlation with gender and education level. This partially contradicts the findings of Dogruel et al. (2022), where AK and awareness dimensions were found to be significantly positively correlated with individual education level. The reason may lie in that the improvement of individual algorithm literacy is not solely influenced by education level. And practical experience accumulation also plays a crucial role. Simultaneously, even individuals with higher education levels may have limited algorithm literacy if their research or work fields are not directly related to algorithms. Therefore, in educational practices aimed at improving individual algorithm literacy, personal backgrounds and actual abilities should be fully considered. Personalized training methods should be employed to make the training more specific and effective.

Research implications

This study has several theoretical and practical implications for the digitalization of academic libraries. Theoretically, this study integrates algorithmic literacy with the traditional TAM. It expands TAM’s explanatory scope. Our research shows that in AI technology environments, users’ algorithmic literacy serves as a cognitive resource. It significantly influences their acceptance willingness. This finding echoes discussions about how user knowledge affects technology acceptance. It especially builds on research that positions algorithmic literacy as a predictor of user interaction with algorithmic systems (Gagrcin et al., 2024). This broadens its application in AI research. Our study also challenges the one-dimensional understanding of algorithmic literacy in previous literature. It enriches the knowledge foundation of algorithmic literacy in user information behavior research. Existing studies emphasize the protective role of algorithmic literacy. For example, Obreja (2024) noted that users can use algorithmic literacy to counter controversial content on short video platforms. Noguera-Vivo and Grandío-Pérez (2025) highlighted the importance of algorithmic literacy in responsible news consumption by citizens. In contrast, our research shows that algorithmic literacy is not just a defense mechanism. It is also an empowering factor that promotes user acceptance of beneficial technologies. This provides a more diverse perspective for understanding user relationships with algorithmic technologies.

Additionally, our study reveals specific pathways through which algorithmic literacy influences technology acceptance. Through empirical analysis, we find that algorithmic literacy affects user acceptance attitudes by reducing PR and increasing PE. This provides a more detailed explanatory framework for understanding how algorithmic literacy works.

In practice, it is recommended that libraries, robot system developers, and users jointly work to improve users’ algorithm literacy. This effort will enhance users’ acceptance of library chatbots. At the library level, libraries can collaborate with platform developers. They can organize educational activities and online courses. These initiatives aim to help users build an AK framework and deepen users’ understanding of the social norms of algorithm application. At the chatbots system designer level, focus on algorithm transparency and user guidance. These efforts are aimed at enhancing users’ trust and understanding of the technology and increase their willingness to use it. At the individual user level, users should actively learn about algorithm-related knowledge to improve their problem-solving abilities and efficiency in intelligent systems. In this process, users’ information literacy and digital skills are enhanced (Adetayo and Oyeniyi, 2023; Houston and Corrado, 2023).

Developers should prioritize the iterative upgrading of library intelligent chatbots system functions. This focus ensures the chatbots can respond to user queries more accurately and quickly, providing a personalized user experience. Additionally, service content should be regularly updated based on user feedback and interaction data to ensure services closely align with user needs. Finally, relevant stakeholders should focus on technical means and management strategies to protect user privacy data security effectively. For developers, clear user privacy protection policies and agreements should be established. This should manage the storage and retention period of user data in compliance. User personal information and conversation data should be anonymized and encrypted. For libraries, transparent information on data processing methods should be provided to users. They should actively address users’ privacy concerns to build trust in intelligent chatbots services.

Limitations

There are still shortcomings in this study. Firstly, this study treats the attitude towards using library AI chatbots as the dependent variable. However, individuals may not necessarily act according to their attitudes, known as the attitude-behavior gap (Stieglitz et al., 2023). Therefore, future research could expand the study variables from attitudes to intentions and continued usage behaviors. Secondly, demographic variables such as gender, age, education level, and experience in algorithm work are considered as control variables in this study. Future studies could treat these variables as independent variables to further explore their effects on user attitudes at different stages. Lastly, this study used a sample of university students. This may limit how our results apply to other reader groups. Future research should use more diverse samples.

Data availability

The data are available at (https://doi.org/10.17632/6x36m9cd7f.1) and can also be obtained from the corresponding author, HL, upon request.

References

Aboelmaged M, Bani-Melhem S, Ahmad Al-Hawari M, Ahmad I (2024) Conversational AI Chatbots in library research: an integrative review and future research agenda. J Librariansh Inf Sci 09610006231224440. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006231224440

Adetayo AJ (2023) Conversational assistants in academic libraries: enhancing reference services through Bing Chat. Library Hi Tech News, ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-08-2023-0142

Adetayo AJ, Oyeniyi WO (2023) Revitalizing reference services and fostering information literacy: Google Bard’s dynamic role in contemporary libraries. Library Hi Tech News, ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-08-2023-0137

Allison D (2012) Chatbots in the library: is it time? Libr Hi Tech 30(1):95–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378831211213238

Applegate R (2008) Gender differences in the use of a public library. Public Libr Q 27(1):19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616840802122468

Archambault SG, Ramachandran S, Acosta E, Fu S (2024) Ethical dimensions of algorithmic literacy for college students: Case studies and cross-disciplinary connections. J Acad Librariansh 50(3):102865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2024.102865

Awal MR, Haque ME (2024) Revisiting university students’ intention to accept AI-Powered chatbot with an integration between TAM and SCT: a South Asian perspective. J Appl Res Higher Educ. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-11-2023-0514

Barach JA (1969) Advertising effectiveness and risk in the consumer decision process. J Mark Res 6(3):314–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224376900600306

Bilquise G, Ibrahim S, Salhieh SEM (2024) Investigating student acceptance of an academic advising chatbot in higher education institutions. Educ Inf Technol 29(5):6357–6382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12076-x

Bohle S (2018) Plutchik”: Artificial intelligence chatbot for searching NCBI databases. J Med Libr Assoc 106(4):501–503. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2018.500

Cetindamar D, Abedin B, Shirahada K (2021) The role of employees in digital transformation: a preliminary study on how employees’ digital literacy impacts use of digital technologies. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2021.3087724

Cheney-Lippold J (2011) A new algorithmic identity: soft biopolitics and the modulation of control. Theory Cult Soc 28(6):164–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276411424420

Dahri NA, Yahaya N, Al-Rahmi WM, Aldraiweesh A, Alturki U, Almutairy S, Shutaleva A, Soomro RB (2024) Extended TAM based acceptance of AI-Powered ChatGPT for supporting metacognitive self-regulated learning in education: a mixed-methods study. Heliyon 10(8):e29317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29317

Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 13(3):319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

DeLone WH, McLean ER (2003) The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update. J Manag Inf Syst 19(4):9–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748

Deng S, Xu J, Xia S (2023) Evaluation system and empirical research on algorithm literacy of college students in digital environment. Libr Inf Serv 67(2):23–32. https://doi.org/10.13266/j.issn.0252-3116.2023.02.003

Dogruel L, Masur P, Joeckel S (2022) Development and validation of an algorithm literacy scale for internet users. Commun Methods Meas 16(2):115–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2021.1968361

Ehrenpreis M, DeLooper J (2022) Implementing a chatbot on a library website. J Web Librariansh 16(2):120–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2022.2060893

Eren BA (2023) Antecedents of robo-advisor use intention in private pension investments: an emerging market country example. J Financ Serv Mark. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-023-00229-5

Ezeudoka BC, Fan M (2024) Determinants of behavioral intentions to use an E-Pharmacy service: Insights from TAM theory and the moderating influence of technological literacy. Res Soc Adm Pharm. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2024.03.007

Featherman MS, Pavlou PA (2003) Predicting e-services adoption: a perceived risk facets perspective. Int J Hum Comput Stud 59(4):451–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00111-3

Gagrcin E, Naab TK, Grub MF (2024) Algorithmic media use and algorithm literacy: an integrative literature review. New Media Soc. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448241291137

Guy J, Pival PR, Lewis CJ, Groome K (2023) Reference Chatbots in Canadian Academic Libraries. Inf Technol Libr 42(4):16511. https://doi.org/10.5860/ital.v42i4.16511

Halder S, Ray A, Chakrabarty PK (2010) Gender differences in information seeking behavior in three universities in West Bengal, India. Int Inf Libr Rev 42(4):242–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iilr.2010.10.004

Harrison RL, Reilly TM (2011) Mixed methods designs in marketing research. Qual Mark Res Int J 14(1):7–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522751111099300

Houston AB, Corrado EM (2023) Embracing ChatGPT: implications of emergent language models for academia and libraries. Tech Serv Q 40(2):76–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2023.2187110

Im I, Kim Y, Han HJ (2008) The effects of perceived risk and technology type on users’ acceptance of technologies. Inf Manag 45(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2007.03.005

Jordan PJ, Troth AC (2020) Common method bias in applied settings: the dilemma of researching in organizations. Aust J Manag 45(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871976

Just N, Latzer M (2017) Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media Cult Soc 39(2):238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Kaushal V, Yadav R (2022) The role of chatbots in academic libraries: an experience-based perspective. J Aust Libr Inf Assoc 71:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2022.2106403

Kesharwani A, Singh Bisht S (2012) The impact of trust and perceived risk on internet banking adoption in India. Int J Bank Mark 30(4):303–322. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652321211236923

Kim TW (2023) Application of artificial intelligence chatbots, including ChatGPT, in education, scholarly work, programming, and content generation and its prospects: a narrative review. J Educ Eval Health Prof 20:38. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2023.20.38

Koenig A (2020) The algorithms know me and i know them: using student journals to uncover algorithmic literacy awareness. Comput Compos 58:102611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2020.102611

Li LL, Coates K (2024) Academic library online chat services under the impact of artificial intelligence. Inf Discov Deliv. https://doi.org/10.1108/IDD-11-2023-0143

Liu TR, Tsang WH, Huang FQ, Lau OY, Chen YH, Sheng J, Guo YW, Akinwunmi B, Zhang CJP, Ming WK (2021) Patients’ preferences for artificial intelligence applications versus clinicians in disease diagnosis during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in China: discrete choice experiment. J Med Internet Res 23(2):e22841. https://doi.org/10.2196/22841

McKie IAS, Narayan B (2019) Enhancing the academic library experience with chatbots: an exploration of research and implications for practice. J Aust Libr Inf Assoc 68(3):268–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2019.1611694

Meuter ML, Bitner MJ, Ostrom AL, Brown SW (2005) Choosing among alternative service delivery modes: an investigation of customer trial of self-service technologies. J Mark 69(2):61–83. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.2.61.60759

Montal T, Reich Z (2017) I, Robot. You, Journalist. Who is the Author? Digit Journal 5(7):829–849. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1209083

Moon HY, Lee BY (2022) Self-service technologies (SSTs) in airline services: multimediating effects of flow experience and SST evaluation. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 34(6):2176–2198. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2021-1151

Nazaretsky T, Mejia-Domenzain P, Swamy V, Frej J, Käser T (2025) The critical role of trust in adopting AI-powered educational technology for learning: An instrument for measuring student perceptions. Comput Educ Artif Intell 8: 100368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2025.100368

Nikou S, De Reuver M, Kanafi MM (2022) Workplace literacy skills-how information and digital literacy affect adoption of digital technology. J Doc 78(7):371–391. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-12-2021-0241

Noguera-Vivo JM, del Grandío-Pérez MM (2025) Enhancing algorithmic literacy: experimental study on communication students’ awareness of algorithm-driven news. Anàlisi 71:37–53. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3718

Obreja DM (2024) Bridging awareness and resistance: Using algorithmic knowledge against controversial content. Big Data Soc 2024(12). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517241296046

Ongena YP, Haan M, Yakar D, Kwee TC (2020) Patients’ views on the implementation of artificial intelligence in radiology: development and validation of a standardized questionnaire. Eur Radio 30(2):1033–1040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06486-0

Pan LJ, Xia YK, Xing LN, Song ZH, Xu YB (2022) Exploring use acceptance of electric bicycle-sharing systems: an empirical study based on PLS-SEM analysis. Sensors 22(18):7057. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22187057

Panda S, Chakravarty R (2022) Adapting intelligent information services in libraries: a case of smart AI chatbots. Libr Hi Tech N 39(1):12–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-11-2021-0081

Petrič G, Atanasova S, Kamin T (2017) Ill literates or illiterates? Investigating the eHealth literacy of users of online health communities. J Med Internet Res 19(10):e331. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7372

Pillai R, Sivathanu B, Metri B, Kaushik N (2024) Students’ adoption of AI-based teacher-bots (T-bots) for learning in higher education. Inf Technol People 37(1):328–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-02-2021-0152

Rieder B (2017) Scrutinizing an algorithmic technique: the Bayes classifier as interested reading of reality. Inf, Commun Soc 20(1):100–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1181195

Rodriguez S, Mune C (2022) Uncoding library chatbots: deploying a new virtual reference tool at the San Jose State University library. Ref Serv Rev 50(3/4):392–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-05-2022-0020

Safadel P, Hwang SN, Perrin JM (2023) User acceptance of a virtual librarian chatbot: an implementation method using IBM Watson natural language processing in virtual immersive environment. TechTrends 67(6):891–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00881-7

Sanji M, Behzadi H, Gomroki G (2022) Chatbot: an intelligent tool for libraries. Libr Hi Tech N 39(3):17–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-01-2021-0002

Shin D, Rasul A, Fotiadis A (2022) Why am I seeing this? Deconstructing algorithm literacy through the lens of users. Internet Res 32(4):1214–1234. https://doi.org/10.1108/intr-02-2021-0087

Stieglitz S, Mirbabaie M, Deubel A, Braun L-M, Kissmer T (2023) The potential of digital nudging to bridge the gap between environmental attitude and behavior in the usage of smart home applications. Int J Inf Manag 72: 102665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102665

Swart J (2021) Experiencing algorithms: how young people understand, feel about, and engage with algorithmic news selection on social media. Soc Media Soc 7(2):205630512110088. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008828

Thalaya N, Puritat K (2022) Bcnpylib Chat Bot: The artificial intelligence Chatbot for library services in college of nursing. 2022 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON), https://doi.org/10.1109/ECTIDAMTNCON53731.2022.9720367

Trepte S, Teutsch D, Masur PK, Eicher C, Fischer M, Hennhöfer A, Lind F (2015) Do People Know About Privacy and Data Protection Strategies? Towards the “Online Privacy Literacy Scale” (OPLIS). In: Gutwirth S, Leenes R, de Hert P (eds), Reforming European data protection law. Springer Netherlands, pp 333–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9385-8_14

Trivedi J (2019) Examining the customer experience of using banking chatbots and its impact on brand love: the moderating role of perceived risk. J Internet Commer 18(1):91–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2019.1567188

Twomey B, Johnson A, Estes C (2024) It takes a village: a distributed training model for AI-based chatbots. information technology and libraries. 43. https://doi.org/10.5860/ital.v43i3.17243

Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD (2003) User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. Mis Q 27(3):425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

Vincze J (2017) Virtual reference librarians (Chatbots). Libr Hi Tech N 34(4):5–8. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-03-2017-0016

Wang X, Luo R, Liu Y, Wu-Ji G (2023a) Influencing factors and empirical research on the usage behavior of smart library online chatbots. J China Soc Sci Tech Inf 42(2):217–230. https://qbxb.istic.ac.cn/EN/10.3772/j.issn.1000-0135.2023.02.008

Wang X, Luo R, Liu Y, Chen P, Tao Y, He Y (2023b) Revealing the complexity of users’ intention to adopt healthcare chatbots: a mixed-method analysis of antecedent condition configurations. Inf Process Manag 60(5):103444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2023.103444

Winkler R, Söllner M (2018) Unleashing the potential of chatbots in education: a state-of-the-art analysis. Acad Manag Proc 2018:15903. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2018.15903abstract

Wu D (2022) Algorithm literacy: the new trend of the library on the smart service outlet. Libr Dev (4):4–5. https://doi.org/10.19764/j.cnki.tsgjs.20221295

Yan R, Zhao X, Mazumdar S (2023) Chatbots in libraries: a systematic literature review. (1875–8649) https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-230045

Xia S, Deng S, Fu S, Zhao H (2023) Algorithm literacy in digital and intelligence era: connotation, category and prospect. Doc,Inf Knowl 40(1):23–34. https://doi.org/10.13366/j.dik.2023.01.023

Xu K, Cheng H (2022) Algorithmic paradoxes and institutional responses—an empirical study based on users’ perceptions of algorithmic applications. J Shandong Univ (Philos Soc Sci) (6):84–96. https://doi.org/10.19836/j.cnki.37-1100/c.2022.06.008

Yi-No Kang E, Chen D-R, Chen Y-Y (2023) Associations between literacy and attitudes toward artificial intelligence–assisted medical consultations: the mediating role of perceived distrust and efficiency of artificial intelligence. Comput Hum Behav 139: 107529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107529

Yang X, Ding J, Chen H, Ji H (2024) Factors affecting the use of artificial intelligence generated content by subject librarians: a qualitative study. Heliyon 10(8):e29584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29584

Zhang M, Shen X, Zhu M, Yang J (2016) Which platform should I choose? Factors influencing consumers’ channel transfer intention from web-based to mobile library service. Libr Hi Tech 34(1):2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-06-2015-0065

Zhao XS, Li XJ, Cheng CS, Cheng B, Liang J, Ma XX (2025) Cognition and practice: a survey and analysis of the current status of AI technology application in university libraries. Inf Manag Stud 10(01):6–19. https://www.calsp.cn/2025/01/21/bulletin-202501-01/

Zeng L, Salvendy G, Zhang M (2009) Factor structure of web site creativity. Comput Hum Behav 25(2):568–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.023

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Social Science Fund of China for young scholars, project approval number 24CTQ016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Heng Lu: Supervision, Writing—review and editing. Xin Li: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statements

The study was approved by the Experimental Ethics Committee of the School of Journalism and Communication, Shaanxi Normal University (Approval No.: 002). The Committee reviewed the project on 10 August 2023, and the approved period for data collection was 15–30 August 2023. The research was conducted in accordance with relevant institutional guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. A scanned copy of the original Chinese approval letter has been submitted with this manuscript. An English translation has also been provided.

Informed consent

For the questionnaire, an electronic informed consent form is attached on the homepage of the survey platform. The form clearly explains the purpose of the survey, guarantees the anonymity of personal information, clarifies that the data will only be used for academic research (not for commercial purposes), and confirms that there are no potential risks of participation. Participants must read the entire consent form and click the “I agree” electronic button to proceed to the questionnaire—this operation is regarded as a valid expression of informed consent. The collection of questionnaire-based informed consent was conducted in two phases: the first phase was August 20, 2023 to August 25, 2023, and the second phase was September 5, 2023 to October 10, 2023. The second phase of data collection was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Journalism and Communication, Shaanxi Normal University through a supplementary approval (date: September 1, 2023). For the interviews, all participants are adults, and no vulnerable groups (e.g., patients, refugees) are involved. Given that all interviews were conducted online, written signature for informed consent was not feasible, so verbal consent was adopted instead. Prior to each interview, the researcher first read the standardized informed consent script (a copy of the script is provided) to the participant, and answered any questions raised. After confirming that the participant fully understood the purpose of the research, the scope of data use (including academic publication), and the recording arrangement, the researcher asked the participant to verbally confirm “I agree to participate” (the verbal consent process was recorded alongside the interview content for verification). The verbal informed consent for each participant was obtained on the same day as the interview, with the overall interview and consent collection period being August 26, 2023 to August 29, 2023.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, H., Li, X. Factors influencing users’ attitudes towards intelligent chatbots in Chinese academic libraries: the role of algorithm literacy. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 85 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06392-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06392-5