Abstract

In China’s mental healthcare system, a critical shortage of professionals limits the implementation of guideline-recommended shared decision-making, leading to high rates of antidepressant non-adherence. This study tested whether a brief, theory-based psychological intervention could improve early medication adherence within existing resource constraints. We conducted a parallel-group, assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial at a tertiary hospital in Guangdong. Eighty outpatients with major depressive disorder were randomized to receive either a 12-week personalized intervention or treatment as usual. The personalized intervention, delivered in eight 30-min sessions, integrated a predictive risk algorithm with stage-matched behavioral techniques to target key adherence determinants. The primary outcomes were medication adherence (MMAS-8) and depressive symptoms (SDS). Among the 60 study completers, the intervention group achieved significantly higher medication adherence at 12 weeks than the control group (between-group difference: 1.09 points), representing an 18% relative improvement. Depressive symptoms decreased substantially in both groups, with no between-group difference. The intervention also led to a significant increase in patient autonomy. This theory-guided protocol effectively improved antidepressant adherence without accelerating short-term symptom reduction. This scalable approach shows promise for bridging the treatment gap in routine psychiatric care in China without requiring additional specialist resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression represents a paramount global public health challenge, ranking as the single largest contributor to disability worldwide and affecting over 260 million people annually (GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2018; Kazdin and Rabbitt, 2013). By 2021, it was already declared the leading cause of disability globally, imposing substantial personal suffering and immense economic costs on societies (World Health Organization, 2011; World Health Organization, 2025).

The China Mental Health Survey (CMHS) confirms a steadily increasing trend in depression rates, reporting a 12-month prevalence of 3.6% and a lifetime prevalence of 6.8% among adults (Huang et al., 2019). This solidifies depression’s status as a critical national public health priority.

The optimal treatment pathway, however, is increasingly contested within global discourse. International guidelines, such as those from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022), recommend prioritizing lower-risk interventions like psychotherapy as first-line treatment for mild-to-moderate depression. This is supported by emerging perspectives, such as the analytical rumination hypothesis (Hollon et al., 2021), which posits depression as an evolutionary adaptation and suggests cognitive-behavioral interventions targeting its proposed function may hold long-term advantages over symptom-targeting antidepressants.

China’s ambulatory mental health services, however, operate within a unique and complex socio-medical context characterized by a fundamental contradiction. On one hand, national guidelines adeptly reflect a nuanced, patient-centered approach. The Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Depressive Disorders (Li and Wang, 2025) advocates for a stepped-care model, recommending psychosocial interventions for mild cases and emphasizing shared decision-making for moderate cases, where treatment choice is based on availability and patient preference. For severe cases, it recommends active pharmacotherapy, often combined with psychotherapy. Crucially, its management principles stress open communication, psychoeducation to reduce stigma, and building a trusting therapeutic alliance—all hallmarks of respecting patient autonomy.

On the other hand, the system is strained by a severe scarcity of resources. China faces a massive mental health treatment gap, exacerbated by a critical shortage of specialized manpower. China faces a massive mental health treatment gap, exacerbated by a critical shortage of specialized manpower, with only 3.5 psychiatrists and ~60 psychiatric beds per 100,000 people (National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2023). The practical implementation of ideal, labor-intensive SDM and psychotherapy is profoundly challenged. This resource constraint makes pharmacological treatment a necessary and widespread option for many patients. Even so, guidelines still urge clinicians to collaboratively determine the treatment plan with patients.

It is within this tension—between ideal patient-centric guidelines and resource-limited reality—that the crisis of medication non-adherence becomes a critical focal point. The 2022 National Depression Bluebook identifies poor medication adherence as the foremost factor contributing to relapse. Studies reported non-adherence rates to antidepressants ranging from 30 to 97%, which is notably higher compared to other psychotropic medications such as antipsychotics and mood stabilizers (Mert et al., 2015). Poor adherence contributes to treatment failure, relapse, progression to chronic depression, higher healthcare utilization, and diminished health-related quality of life (Chong et al., 2011; Alekhya et al., 2015).

Multiple factors contribute to antidepressant non-adherence, including doubts about medication efficacy, fear of dependency, complex treatment regimens, side effects (e.g., sexual dysfunction), financial burden, inadequate patient–provider communication, and societal stigma surrounding mental illness (Jaffray et al., 2014; van Geffen et al., 2011; Milosavljevic et al., 2018). Studies have shown that treatment satisfaction is closely linked to medication adherence, particularly among individuals with chronic illnesses (Barbosa et al., 2012; Aljumah et al., 2014). Patients who perceive their treatment as effective and consistent with their expectations are more likely to adhere. Factors influencing treatment satisfaction include perceived effectiveness, side effect profile, convenience of dosage form, dosing frequency, and patients’ positive beliefs about the treatment, all of which ultimately affect adherence (Bharmal et al., 2009).

Therefore, while the international “efficacy-versus-risk” debate is relevant, it cannot be simply transplanted to China and does not negate the urgent need for adherence interventions. Here, improving adherence is not about paternalistically ‘forcing patients to take pills,’ but rather represents a pragmatic and ethical imperative to empower patients within a constrained system. The goal is to enable them to complete a co-determined treatment course through transparency and structured support, thereby navigating the interplay between global evidence, local constraints, and individual autonomy.

Our research group previously developed the Psychiatric Medication Adherence Prediction Scale, validated its reliability and validity among individuals with depression, established cutoff scores, and refined the predictive tool. Subsequently, we explored the relationship between early-stage depression characteristics and acute-phase medication adherence, using this foundation to construct a medication adherence prediction model for outpatient depression patients. This model predicts future medication adherence during acute treatment based on patients’ early-stage characteristics. Additionally, we investigated the developmental trajectories and influencing factors of acute-phase medication non-adherence among outpatient depression patients. Building upon the research team’s prior findings, this study further advanced personalized psychological interventions targeting medication adherence in depression patients.

Building upon our previous development of a Psychiatric Medication Adherence Prediction Scale and related foundational studies, this research aims to develop and evaluate a personalized psychological intervention to enhance medication adherence in outpatients with depression. The intervention integrates a predictive model to identify at-risk patients and applies a dynamic framework informed by the Health Belief Model (HBM) and Self-Determination Theory to provide tailored support. This approach not only addresses practical barriers but also targets the core psychological determinants of adherence.

Literature review

Conceptual definitions

Medication adherence

Medication adherence is defined as the extent to which a patient’s behavior corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider (World Health Organization, 2003). Operationally, this encompasses the degree to which patients take their medication as prescribed, including dosage, frequency, and duration. Non-adherent behaviors include outright refusal to take medication, premature discontinuation, and incorrect dosing (taking the wrong dose or taking it at the wrong time).

Acute phase

According to the Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Depressive Disorders, the full-course management of depression comprises four distinct phases: acute, consolidation, maintenance, and termination, spanning a total period from 7 months to 4 years. The acute phase constitutes the initial stage of treatment. Its primary objective is to achieve symptomatic control and restore the patient’s functional capacity to pre-illness levels, aiming for clinical remission (Li and Wang, 2025).

Theoretical foundations: from behavioral correction to patient empowerment

The conceptual understanding of medication adherence has evolved significantly, shifting from a paternalistic model of “compliance” toward a collaborative framework of “adherence” grounded in patient empowerment and shared decision-making. This theoretical progression provides the essential foundation for the present intervention.

Several theoretical models offer valuable insights into the determinants of health behavior. Among the most influential are the Health Belief Model (HBM; Rosenstock, 1974), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991), Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan, 2000), and the Transtheoretical Model (TTM; Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983). Each contributes to a multifaceted understanding of adherence.

The HBM posits that health behaviors are determined by an individual’s perceived threats and benefits. Key constructs include perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, self-efficacy, and cues to action. This means a patient is more likely to take their medication if they feel susceptible to depression, believe it is severe, and see the benefits of treatment as outweighing barriers like side effects or stigma. Thus, non-adherence can be reframed not as a failure to obey, but as a rational choice based on the patient’s personal calculus.

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM), or Stages of Change model, is particularly critical for designing personalized interventions. TTM conceptualizes behavior change as a dynamic, non-linear process through which individuals progress through distinct stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. The core implication is that an intervention effective for a patient in precontemplation (unaware or unwilling to change) will be fundamentally different from one tailored for a patient in preparation (intending to act). This “stage-matched” approach is the cornerstone of providing truly individualized support, moving beyond generic advice to “take your medication.”

Synthesis and Perspective: Therefore, the theoretical lens adopted in this study is that effective adherence intervention is not about coercing behavior but about facilitating informed choice and providing empowerment. It involves using HBM-based assessments to understand a patient’s unique perceptual barriers and benefits and then applying TTM to provide the stage-appropriate tools and support to empower them to successfully execute their treatment plan.

Current landscape of adherence interventions: limitations and insights

A wide array of interventions has been developed to improve medication adherence in depression, which can be broadly categorized as follows:

Educational interventions

Aim to improve knowledge about depression and medication. While necessary, they are often insufficient, as knowledge alone rarely changes deep-seated behaviors or beliefs.

Behavioral interventions

Employ reminders (e.g., SMS, pillboxes) to cue the correct behavior. These address the barrier of “forgetfulness” but fail to engage with the motivational and cognitive barriers underlying intentional non-adherence.

Psychosocial interventions

Include strategies like Motivational Interviewing (MI) and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT). These are among the most effective approaches, as they target underlying beliefs and motivations (Interian et al., 2010).

Technology-based interventions

Leverage mobile health applications (apps) and digital platforms to deliver reminders, education, and monitoring. Systematic reviews indicate that such mobile technologies can show positive effects on adherence rates.

Despite this variety, existing interventions are constrained by three critical limitations that hinder their effectiveness and scalability, particularly in the Chinese context:

Lack of a coherent theoretical foundation

Many interventions are pragmatic but atheoretical. Without being explicitly guided by models like TTM, they cannot achieve true stage-matched personalization, applying identical strategies to patients at vastly different stages of readiness.

Neglect of individual heterogeneity

The predominant “one-size-fits-all” model fails to account for differences in patients’ readiness to change, their specific beliefs (HBM dimensions), and their unique life contexts.

Resource inaccessibility

The most effective strategies (e.g., MI, CBT) are highly resource-intensive, requiring extensive, trained specialist time that is profoundly scarce in China’s mental healthcare system, thus creating a significant implementation gap (Emmelkamp, 2025).

This review underscores an urgent need for a novel intervention that is simultaneously theory-driven, personalized, and deliverable within the constraints of routine clinical care.

The conceptual framework and innovation of the present study

Directly responding to this triple mandate for theoretical coherence, individualization, and practicality, this study proposes a novel, two-phase personalized psychological intervention program, grounded in the integrated application of the HBM and the TTM.

Conceptual framework

The intervention begins with a Predictive Phase, utilizing a pre-developed adherence predictive scale to identify patients at high risk for non-adherence and to diagnose their specific perceptual barriers based on HBM dimensions (e.g., low perceived necessity, high perceived barriers from family, low self-efficacy). This diagnostic assessment directly informs a Process-Based Phase, where the patient’s identified stage on the TTM continuum dictates the specific, stage-matched interventional strategy delivered over the subsequent weeks (e.g., consciousness-raising for precontemplation, stimulus control for action).

Innovations of this study are multifold:

Theoretical integration innovation

By explicitly integrating HBM and TTM to first diagnose the root cause of non-adherence and then prescribe a tailored strategy, this study advances beyond descriptive theory toward an operationalized support mechanism.

Intervention model innovation

The “Predictive + Processual” two-stage model allows for early identification of at-risk patients before non-adherence occurs and provides a continuous support pathway that adapts to the patient’s evolving journey.

Practical value innovation

The protocol is designed for high feasibility and scalability within the Chinese healthcare system by being structured for delivery by physicians and nurses within standard workflows, thereby maximizing impact without requiring an expansion of specialist resources.

Method

Study design

We conducted a two-arm, parallel-group, assessor-blinded, randomized controlled trial (RCT). This trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy of a personalized, theory-based psychological intervention compared to treatment-as-usual (TAU) on medication adherence in outpatients with depression. The intervention was delivered over a 12-week period, comprising an initial predictive phase (Weeks 0–4) and a subsequent Process-Based Phase (Weeks 5–12). The trial was conducted at the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology of a tertiary general hospital in Guangdong Province, China.

Participants

Participants were recruited via convenience sampling from first-visit outpatients at the study site. All participants were receiving routine multidisciplinary psychiatric care. After randomization, participants were included in only one study arm (intervention or TAU). Researchers collecting outcome assessments were blinded to the participants’ group allocation.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University (Approval Nan Yi Lun Shen 2021 No.011). Prior to enrollment, all participants (and their parents or legal guardians, where applicable) received a comprehensive explanation of the study and provided written informed consent.

To ensure confidentiality, all participant data were de-identified and stored under a unique code, with access restricted to the principal investigators. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Outpatients with a clinician-confirmed diagnosis of a depressive episode according to DSM-5 criteria; (2) A score of ≥53 on the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS); (3) Minimum education level of primary school; (4) Access to a telephone for follow-up purposes.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) Presence of organic brain diseases; (2) Current psychotic symptoms; (3) Diagnosis of organic depressive disorders; (4) Severe comorbid somatic diseases that could interfere with participation; (5) Substance abuse or dependence; (6) A history of severe drug allergy.

Eligibility was confirmed by a study psychiatrist based on medical record review and clinical assessment.

Randomization and blinding

Eligible participants were randomly allocated (1:1) to the intervention or TAU control group after the completion of all baseline assessments (T1).

An independent statistician generated the randomization schedule (block sizes of 4 and 6), prepared by an independent statistician. Allocation was stratified by sex to ensure balance between groups. Allocation concealment was ensured using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. These envelopes were stored in a locked location and were opened sequentially by a research coordinator only after a participant’s baseline data had been collected.

Due to the nature of the psychological intervention, participants and the intervention providers could not be blinded to group assignment. However, outcome assessors, the data management team, and the trial statistician were blinded to group allocation for the duration of the study. Participants were instructed not to reveal their assignment to assessors.

Interventions

Experimental intervention (personalized, theory-based psychological intervention)

The experimental intervention was a 12-week, multi-component program grounded in behavioral change theories. It was delivered across eight individualized, 30-min sessions. The intervention was structured in two phases:

Predictive phase (weeks 0–4)

The baseline PSPMA assessment guided the application of tailored strategies across five key domains: Autonomy Enhancement, Perceived Necessity, Medication Beliefs, Family Support, and Self-Efficacy. This included psychoeducation, MI, and collaborative problem-solving.

Process-based phase (weeks 5–12)

Intervention strategies were dynamically adapted weekly based on the participant’s assessed Stage of Change (Precontemplation, Contemplation, Preparation, Action, Maintenance). Focus shifted from building motivation in early stages to reinforcing behavior and preventing relapse in later stages. The intervention was delivered by trained psychological research staff under the supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist.

Control intervention (treatment-as-usual—TAU)

Participants allocated to the TAU group received standard outpatient care, which included regular psychiatric consultations, medication management, and general advice. They did not receive the structured, theory-based psychological intervention provided to the experimental group.

Outcome measures

Assessments were conducted at baseline (T1), week 2 (T2), week 4 (T3), week 8 (T4), and week 12 (T5) as detailed in Table 1. Data were collected through on-site paper-based questionnaires, telephone follow-ups, and electronic medical record reviews.

Primary outcome

The primary outcomes of this study were assessed using two validated instruments to capture changes in depressive symptomatology and medication adherence behavior:

Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)

The SDS is a widely used 20-item self-report measure that assesses the affective, cognitive, and somatic dimensions of depression. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. This scale was selected as a primary endpoint to directly evaluate the intervention’s impact on the core clinical manifestation of depression.

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS)

The MMAS is an 8-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure adherence behaviors and attitudes toward psychotropic medications. The MMAS was chosen as a co-primary outcome because improving adherence is the central objective of the proposed intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were employed to explore the intervention’s effects on underlying mechanisms and predictive factors related to adherence:

Predictive scale for psychotropic medication adherence (PSPMA)

This scale was used to identify patients at high risk of non-adherence at baseline and to monitor changes in predictive risk factors (e.g., beliefs about medication, perceived self-efficacy) throughout the study period.

Self-efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS)

The SEAMS is a 13-item instrument that assesses a patient’s confidence in their ability to manage medication use under various challenging situations. Responses are scored on a 3-point scale, and higher total scores reflect greater medication self-efficacy. This measure was included to evaluate whether the intervention effectively enhanced this critical psychological mechanism, which is theorized to mediate long-term adherence behavior.

Sample size

The sample size was determined a priori for the marginal model (GEE) analysis of the primary continuous outcome. The sample size calculation was based on the Zhang–Ahn formula for marginal models. Key assumptions included a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.50) at 12 weeks, an exchangeable working correlation structure with an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of ρ = 0.20, and three repeated measurements (baseline, 6-week, and 12-week). With α = 0.05 (two-sided) and power = 0.80, a total of 66 participants (33 per group) were required. Accounting for an estimated 20% attrition over 12 weeks, we aimed to recruit 80 participants (40 per group).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS 28 (IBM Corp.). Two-tailed α was set at 0.05; Bonferroni–Holm correction was applied when multiple contrasts were tested.

Continuous repeated measures

Medication adherence (MMAS-8), depressive symptoms (SDS), self-efficacy (SEAMS), and PSPMA sub-scores were analyzed with generalized estimating equations (GEE, unstructured correlation, robust SEs). The model included the fixed effects of Group, Time (as a categorical factor), and their Group × Time interaction. Effect sizes are Cohen’s d from model-implied marginal means. Simple contrasts used the Bonferroni–Holm adjustment.

Ordinal outcomes

Stage of Change and Medication Effectiveness Rating were analyzed with ordinal GEE (logit link, unstructured correlation); proportional-odds assumptions were met (Brant test p ≥ 0.08).

Robustness

All models were re-estimated with AR(1) correlation, and after excluding two participants who switched to mania, significance and effect magnitudes were unchanged. VIF < 1.9 excluded multicollinearity.

Result

Participant flow and attrition analysis

A total of 80 eligible patients with acute-phase major depressive disorder were recruited from a tertiary hospital in Guangdong, China, and randomly allocated to the intervention (n = 40) or control (n = 40) group. Twenty participants (25%) dropped out before study completion and were excluded from the per-protocol analysis, yielding a final analysis sample of 60 participants. The attrition rate did not differ significantly between groups (χ² = 0.00, p = 1.00). Loss to follow-up was the most common reason for dropout (n = 14), followed by switching to psychotherapy (n = 4), self-discontinuation of medication (n = 3), transition to a manic episode (n = 2), and physician-advised discontinuation (n = 1).

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for the 60 participants who completed the study are presented in Table 2. The sample had a mean age of 21.88 years (±5.53) and was predominantly female (78.3%). The intervention and control groups were well-balanced at baseline, with no statistically significant differences in any demographic variables, including age, sex, ethnicity, residence, or education (all p > 0.05). Clinical characteristics, such as depression severity, family history of mood disorders, and treatment preferences, were also comparable between groups (all p > 0.05), confirming the success of the randomization process.

Primary outcomes

Medication adherence (MMAS-8)

Generalized estimating equations revealed a significant group × time interaction (Wald χ² = 17.30, p = 0.001) with substantial main effects for both time (Wald χ² = 95.94, p < 0.001) and group (Wald χ² = 23.19, p < 0.001). Detailed GEE results are provided in Table 3. Analysis of simple effects with Bonferroni-Holm correction demonstrated comparable baseline scores between groups (T2 difference = −0.63, p = 1.00). Full details of between-group comparisons at all time points are available in Table 4. The intervention group showed a characteristic pattern: an initial decline at T2 (β = −1.73, p < 0.001) followed by progressive improvement. By endpoint (T5), the intervention group achieved significantly higher adherence (mean = 7.02, SE = 0.64) compared to controls (mean = 5.93, SE = 1.06), with a between-group difference of 1.09 points (95% CI 0.38–1.80, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.38). This represents an 18.4% relative improvement in adherence.

Within-group analyses revealed sustained improvement exclusively in the intervention group (T5 vs T2: +2.83 points, p < 0.001), while control participants showed minimal change (+1.10 points, p = 0.076). Sensitivity analysis using an autoregressive correlation structure confirmed the robustness of these findings, yielding a nearly identical group × time interaction (Wald χ² = 17.30, p = 0.001).

Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)

Table 5 displays the marginal mean SDS scores across five waves. Both groups demonstrated substantial symptom improvement over time, as evidenced by a strong main effect of time (Wald χ² = 84.0, p < 0.001), with an average reduction of 7.17 points from T1 to T5 (95% CI: 4.53–9.81). However, neither the main effect of group (Wald χ² = 0.22, p = 0.64) nor the group × time interaction (Wald χ² = 0.06, p = 0.80) reached significance. The between-group difference at study endpoint was minimal (0.77 points, 95% CI: −3.29 to 4.82, p = 0.71) and substantially below the established minimal clinically important difference of 5 points. Multiple imputation analysis addressing potential missing data confirmed these null findings (group × time interaction: Wald χ² = 0.06, p = 0.80).

Secondary outcomes

Self-efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS)

Table 6 shows that a small but significant main effect of time was observed (Wald χ² = 8.40, p = 0.004), with self-efficacy scores increasing by an average of 2.23 points in both groups combined (95% CI: −4.21 to −0.26, p = 0.027). Neither the main effect of group nor the group × time interaction was significant (p = 0.65), indicating similar improvement in both groups.

Predictive Scale for Psychotropic Medication Adherence (PSPMA)

Analysis of the PSPMA dimensions revealed distinct patterns over time and between groups (Table 7). Significant improvements over time were observed in three of the five dimensions after Bonferroni-Holm correction: patient autonomy (mean increase = 0.32 points), perceived necessity (0.24 points), and drug acceptance (0.45 points). Medication self-efficacy and family support remained stable across the study period.

Regarding group differences, the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher patient autonomy than the control group (mean difference = 0.55 points, p = 0.001). Conversely, the control group reported higher levels of family support (mean difference = −0.40, p = 0.031). No significant group differences were found for the other three dimensions.

Finally, the Time × Group interaction for Medication Self-Efficacy showed a non-significant trend (Wald χ² = 3.54, p = 0.060), suggesting a potential differential change between groups. All other interaction terms were non-significant.

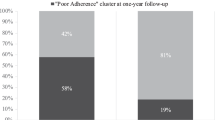

Ordinal outcomes

Behavioral stage of change

Analysis of the Behavioral Stage of Change, assessed at the end of the predictive (T3) and process-based (T5) phases, showed a significant main effect of time (Wald χ² = 4.339, p = 0.037). The negative coefficient at T3 (B = −1.573) indicates that participants progressed to more advanced stages of change by the end of the study (T5). There was no significant main effect of group (Wald χ² = 0.836, p = 0.361) and no significant time-by-group interaction (Wald χ² = 0.412, p = 0.521), indicating that this progression was comparable between the intervention and control groups (Table 8).

Medication effectiveness rating

Analysis of the Medication Effectiveness Rating across four time points (T1-T4) revealed a highly significant main effect of time (Wald χ² = 88.463, p < 0.001). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that ratings were significantly lower at both T1 (B = −2.78, p < 0.001) and T2 (B = −1.35, p = 0.001) compared to T4, but not at T3 (B = −0.35, p = 0.360). Neither the main effect of group nor the time-by-group interaction was significant (both p > 0.05), demonstrating a uniform positive trajectory in both groups (Table 9).

Figure 1 illustrates the trajectories of primary and secondary outcomes across the five measurement points. Panel A (MMAS-8) shows a divergent course between groups after T2, with the intervention group demonstrating a steady upward trajectory while the control group plateaued after T3. This visual separation corroborates the significant group × time interaction observed in the GEE model. In contrast, Panels B (SDS) and C (SEAMS) display nearly superimposable trajectories for both groups, with parallel declines in depressive symptoms and concurrent increases in self-efficacy, consistent with the non-significant group effects for these outcomes.

Discussion

Principal findings and interpretation

Our personalized, theory-based intervention significantly improved medication adherence, as measured by the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 (MMAS-8), demonstrating a moderate and sustained effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.38) over the 12-week trial. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of this finding. The intervention group achieved a mean score increase of 2.83 points from baseline to endpoint (T5), substantially surpassing the 1.10-point improvement in the TAU control group, underscoring the specific efficacy of our approach.

It is important to contextualize our study’s 25% attrition rate. Dropout during acute-phase depression treatment is a common challenge; reported rates typically range from 20 to 40% in clinical trials and can be even higher in observational studies (Demyttenaere, 2003). Our attrition rate, which did not differ significantly between groups, falls within this expected range and is consistent with the practical difficulties of maintaining engagement in this patient population.

The adherence trajectory within the intervention group offered further insight into the mechanism of change. We observed an initial decline at T2, a pattern congruent with the TTM’s postulate that individuals often experience ambivalence and temporary setbacks when progressing from contemplation to action. This was followed by a significant and steady rise in adherence through T5, indicating that the intervention’s components (e.g., skill-building, autonomy support) effectively facilitated progression through the stages of change to foster durable behavior.

The magnitude of our effect size places the intervention at the higher end of the spectrum reported in the adherence literature. For instance, the effect surpasses that of a technology-based strategy using a smartphone app (Krell et al., 2004) and appears more robust than the often modest effects highlighted in recent systematic reviews (Kengne et al., 2024). This enhanced efficacy is likely attributable to our theory-driven, multifaceted design. It integrates several evidence-based behavior change techniques—such as “action planning” and “instruction on how to perform the behavior,” which are associated with success (Teo et al., 2024)—within a structured, stage-matched framework. This synergy creates a tailored approach to overcoming individual barriers, proving more potent than single-component strategies.

Null effect on depressive symptoms

A key finding of this study is the clear dissociation between improved medication adherence and short-term depressive symptom reduction. Despite the intervention’s significant effect on adherence, it did not accelerate symptom improvement compared to the control group over 12 weeks. The between-group difference at endpoint was negligible (0.77 points on the SDS) and well below the minimal clinically important difference, a conclusion robust to sensitivity analysis.

This dissociation suggests that the psychological mechanisms driving medication-taking behavior are distinct from the neurobiological processes governing antidepressant response. The primary benefit of enhanced adherence may thus lie in long-term outcomes, such as relapse prevention and sustained recovery, rather than in accelerating initial symptom resolution.

Our null finding regarding symptoms contrasts with some literature. For instance, a systematic review by Marasine et al. (2025) reported that some integrated care models improved both adherence and depression severity. This contrast underscores that improving adherence, while achievable, is not invariably sufficient for symptom remission, highlighting the multifaceted nature of treatment response.

Several interrelated factors may explain the lack of symptomatic benefit. First, methodological considerations may have played a role; the self-rated SDS, assessed at a single endpoint, may lack the sensitivity to capture nuanced symptom dynamics. More substantially, clinical and pharmacological complexities are likely pivotal. Symptoms can follow non-linear trajectories influenced by unmanaged side effects, psychosocial stressors, or developing pharmacological tolerance. Furthermore, adherence alone cannot overcome inherent pharmacotherapeutic limitations, such as treatment-resistant profiles in a portion of the cohort. Finally, a conceptual limitation of our intervention is that it primarily targeted behavioral adherence, potentially without sufficiently addressing deeper perceptual barriers, such as persistent negative beliefs about medication, which can undermine its perceived efficacy and thus its symptomatic benefit.

Mechanisms of change: autonomy vs. self-efficacy

The intervention successfully enhanced patient autonomy, fostering a greater sense of personal control and self-determination in medication management. This empowerment, addressing a crucial psychological need in depression, appears to be a key mechanism through which the intervention improved adherence.

In contrast, the intervention did not yield a significant additional improvement in general medication self-efficacy compared to standard care. This clear dissociation confirms that autonomy and general self-efficacy are distinct constructs and indicates that our intervention specifically and effectively targeted the former. The non-significant finding for self-efficacy could be due to the SEAMS scale’s potential insensitivity to the context-specific self-efficacy our intervention cultivated, or a ceiling effect created by the general self-efficacy support inherent in standard care.

Therefore, the intervention’s success in improving adherence primarily through enhancing autonomy, rather than general self-efficacy, positions patient autonomy as a particularly critical mechanism of change for individuals with Major Depressive Disorder. This finding aligns with theories of intrinsic motivation, which emphasize that personal control over treatment decisions can be a more powerful driver of behavior than general confidence beliefs (Luo et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2018).

The unexpected role of social and family support

A counterintuitive finding was that the control group reported significantly higher levels of family support than the intervention group. While this could point to an unmeasured baseline imbalance, a more compelling interpretation relates to the intervention’s core mechanism.

We hypothesize that by actively fostering patient autonomy and self-management skills, the intervention may have reduced patients’ perceived need for external familial support. Patients in the intervention group, feeling empowered to manage their own treatment, might have become less reliant on family reminders. Conversely, the control group, lacking this targeted empowerment, may have remained more dependent on family members for practical and emotional support, leading to their higher reported levels of perceived support.

Theoretical and mechanistic insights

The intervention’s success in improving medication adherence, despite its null effect on depressive symptoms, underscores the critical role of its theoretical underpinnings, particularly the TTM, in guiding its mechanism of action.

The TTM provides a powerful lens through which to interpret the observed adherence trajectory. The characteristic early dip in adherence at T2 is not indicative of failure but rather exemplifies the early-stage resistance and ambivalence theorized by the TTM as individuals commit to behavior change. This initial setback likely represents a critical transition point as patients grappled with the cognitive and emotional demands of moving from contemplation to action.

Subsequently, the significant and steady rise in adherence from T3 to T5 demonstrates the intervention’s efficacy in facilitating progression through the stages of change. Through continued, stage-matched support—which may have ranged from resolving ambivalence in earlier stages to reinforcing new habits in later stages—the intervention helped patients consolidate medication-taking into a stable behavior. This pattern underscores that short-term fluctuations are an expected part of the change process, highlighting the importance of sustained, theory-driven support over a one-size-fits-all approach for achieving long-term adherence.

Conclusion

This RCT establishes that a structured, theory-based intervention can significantly improve medication adherence in outpatients with acute-phase major depressive disorder by successfully enhancing patient autonomy. The core finding—a clear dissociation between improved adherence and accelerated short-term symptom relief—challenges the assumption that modifying adherence behavior will directly and immediately translate into symptomatic benefit. It underscores that adherence is a valid, independent treatment target governed by distinct psychological mechanisms.

These insights carry significant clinical implications. They provide a robust evidence base for integrating theory-driven, personalized adherence support into standard depression care, moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach. The intervention demonstrates that empowering patients in their treatment journey is a viable and effective strategy, even within the constraints of routine clinical practice.

Study limitations, including the single-center design and 12-week follow-up, point to clear priorities for future research. Subsequent investigations should employ longer-term trials to determine if the achieved adherence gains translate into the ultimate goal of sustained recovery and relapse prevention. Further exploration is also warranted to bridge the identified gap between adherence and symptom change, and to refine the intervention’s components for different patient subpopulations. This work paves the way for a new generation of adherence strategies that are not only effective but also precisely targeted to the psychological needs of individuals with depression.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study involve sensitive personal information and are therefore not publicly accessible. Researchers who wish to access the data may submit a formal request, which will be considered following approval by the relevant ethics committee.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Alekhya P, Sriharsha M, Ramudu RV, Shivanandh B, Darsini TP, Siva K, Reddy YH (2015) Adherence to antidepressant therapy: Sociodemographic factor-wise distribution. Int J Pharm Clin Res 7(3):180–184

Aljumah K, Ahmad Hassali A, AlQhatani S (2014) Examining the relationship between adherence and satisfaction with antidepressant treatment. Neuropsych Dis Treat 10:1433–1438. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S67008

Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D (2012) A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adher 6:39–48. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S24752

Bharmal M, Payne K, Atkinson MJ, Desrosiers MP, Morisky DE, Gemmen E (2009) Validation of an abbreviated Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM-9) among patients on antihypertensive medications. Health Qual Life Out 7:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-36

Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF (2011) Effectiveness of interventions to improve antidepressant medication adherence: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pr 65(9):954–975. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02746.x

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2000) The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq 11(4):227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Demyttenaere K (2003) Risk factors and predictors of compliance in depression. Eur Neuropsychopharm 13(3):69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-977X(03)00095-6

Emmelkamp PMG (2025) Failures in cognitive behavior therapy: the state of the art. Curr Opin Psychol 66: 102122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2025.102122

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2018) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392(10159):1789–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

Hollon SD, Andrews PW, Singla DR, Maslej MM, Mulsant BH (2021) Evolutionary theory and the treatment of depression: it is all about the squids and the sea bass. Behav Res Ther 143: 103849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103849

Huang, Wang YU Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, Yu Y et al. (2019) Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a Cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiat 6(3):211–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X

Interian A, Ang A, Gara MA, Link BG, Rodriguez MA, Vega WA (2010) Adaptation of a motivational interviewing intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among Latinos. Cult Divers Ethn Min 16(2):215–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016072

Jaffray M, Cardy AH, Reid IC, Cameron IM (2014) Why do patients discontinue antidepressant therapy early? A qualitative study. Eur J Gen Pr 20(3):167–173. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814788.2013.838670

Kazdin AE, Rabbitt SM (2013) Novel models for delivering mental health services and reducing the burdens of mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci 1(2):170–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702612463566

Kengne AP, Brière JB, Gudiña IA, Jiang X, Kodjamanova P, Bennetts L, Khan ZM (2024) The impact of Non-pharmacological interventions on adherence to medication and persistence in dyslipidaemia and hypertension: a systematic review. Expert Rev Pharm Out 24(7):807–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2024.2319598

Krell HV, Leuchter AF, Morgan M, Cook IA, Abrams M (2004) Subject expectations of treatment effectiveness and outcome of treatment with an experimental antidepressant. J Clin Psychiat 65(9):1174–1179. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v65n0902

Li LJ, Wang G (2025) Chinese guidelines for the prevention and treatment of depressive disorders. People’s Medical Publishing House

Liu S, Na H, Li W, Yun Q, Jiang X, Liu J, Chang C (2018) Effectiveness of Self-management behavior intervention on type 2 diabetes based on self-determination theory. J Peking Univ (Health Sci) 50(3):474–480

Luo Y, Shi J, Zhang M, Ding Z, Liu S, Zan S, Du R, Tan Y, Yang P, Wang Z (2023) Intrinsic motivation in patients with depression. Chin Ment Health J 37(4):279–285

Marasine NR, Sankhi S, Paudel S, Chalise A, Lamichhane R (2025) Impact of pharmaceutical care interventions on antidepressants adherence and clinical outcomes in depressed patients: a systematic review. Explor Res Clin Soc 20: 100644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsop.2025.100644

Mert DG, Turgut NH, Kelleci M, Semiz M (2015) Perspectives on reasons of medication nonadherence in psychiatric patients. Patient Prefer Adher 9:87–93. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S75013

Milosavljevic A, Aspden T, Harrison J (2018) Community Pharmacist-led interventions and their impact on patients’ medication adherence and other health outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Pharm Pr 26(5):387–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpp.12462

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (2023) China health statistics yearbook. Peking Union Medical College Press

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2022) Depression in adults: treatment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222. Accessed 14 Oct 2024

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1983) Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psych 51(3):390–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390

Rosenstock IM (1974) The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr 2(4):354–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200405

Teo V, Weinman J, Yap KZ (2024) Systematic review examining the behavior change techniques in medication adherence intervention studies among people with type 2 diabetes. Ann Behav Med 58(4):229–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaae001

van Geffen ECG, Hermsen JH, Heerdink ER, Egberts AC, Verbeek-Heida PM, van Hulten R (2011) The decision to continue or discontinue treatment: Experiences and beliefs of users of selective Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in the initial Months-a qualitative study. Res Soc Admin Pharm 7(2):34–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.04.001

World Health Organization (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2024

World Health Organization (2011) global burden of mental disorders and the need for a comprehensive, coordinated response from health and social sectors at the country level. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/eb130/b130_9-en.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2024

World Health Organization (2025) Depression disorder. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression. Accessed 14 Oct 2024

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72174082 & 82373695), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2023A1515011825), and the Guangdong-Hong Kong Joint Laboratory for Psychiatric Disorders (2023B1212120004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wanying Cheng revised the paper and participated in the writing and editing process, and led the additional work required, which encompassed a comprehensive re-analysis of the entire dataset and a substantial rewrite of the “Results and Discussion” sections. Xiayida Maimaiti completed the design of the questionnaire, data collection, and thesis writing. Jiubo Zhao provided theoretical guidance and experimental design, reviewed a draft of the thesis, and provided valuable revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University (Approval Nan Yi Lun Shen 2021 No.011) on July 14, 2021. All research procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The approved protocol encompassed the recruitment of outpatients with depression, the delivery of the personalized psychological intervention and treatment-as-usual, and the collection and analysis of all outcome measures.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and, for participants under the age of 18, from their parents or legal guardians. The consent process was conducted by the principal investigator and trained research coordinators prior to any study procedures (between August 2023 and February 2024). Participants and their guardians were comprehensively informed about the study’s aims, procedures, potential risks and benefits, confidentiality safeguards, and their right to withdraw without penalty. The consent covered participation in the study, the use of their anonymized data for research purposes, and the publication of aggregated findings.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, W., Maimaiti, X. & Zhao, J. Individualized psychological intervention for medication adherence in outpatients with depression. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 110 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06416-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06416-0