Abstract

Effect sizes quantify the outcome of empirical studies and thus provide the crucial answer to the research question. Unstandardized effect sizes do so in absolute terms, i.e., in terms of the values of the scales used, and are therefore generally easy to interpret. Standardized effect sizes, on the other hand, are a relative piece of information with the advantage that they are free from arbitrary units. However, since many commonly used effect sizes take the variance into account, they carry the risk of being misinterpreted or overinterpreted. In Study 1, the typical use of effect sizes in psychological research was analyzed. Results indicate that although effect sizes are almost always reported, they are most often reported primarily in standardized form, and conventions are most often used to interpret them, most commonly those of Cohen (1988). In Study 2, potential challenges in interpreting standardized effect sizes were analyzed using the example of a mean difference and typical research scenarios for which Cohen’s d was reported. The results suggest that the majority of researchers in psychology attribute more meaning to the standardized effect size than it actually conveys. Therefore, in line with the existing literature, it is recommended that more emphasis be placed on non-standardized effects when interpreting empirical results. In addition, existing conventions for standardized effect sizes should be revised and adapted to psychological subdisciplines or specific research topics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Empirical research in psychology aims to produce reliable evidence that not only enhances our understanding of human behavior but also supports the development of effective interventions. The notion of reliability in this context generally refers to the ability of empirical findings to yield unbiased estimates of true population parameters—what we would observe if it were possible to study an entire population with perfectly accurate instruments. These parameters often reflect either differences between groups or conditions, or the strength of associations between variables. Thus, in practical terms, they represent the central outcome of a study and are commonly referred to as effects.

In the methodology of psychology, two main approaches exist for establishing such effects: confirmatory and exploratory research. In confirmatory research, hypotheses or expectations about population effects are derived from theoretical frameworks or prior empirical evidence. The empirical study is then designed to test these predictions under controlled conditions. Exploratory research, by contrast, begins with the data and seeks to infer potential effects, which can then inspire new hypotheses or theories. Regardless of approach, the focus of empirical analysis is on identifying, estimating, and interpreting these effects (e.g., Abelson, 2012; Baguley, 2009; Cumming, 2014; Ellis, 2010; Funder & Ozer, 2019; Kelley & Preacher, 2012; Kirk, 2007; Pek & Flora, 2018; Rosnow & Rosenthal, 2009; for criticism of this general approach to the use of effect sizes, however, see also Broers, 2021).

The utility of effect sizes in scientific reasoning depends on how they are conceptualized and interpreted. Kelley and Preacher (2012) distinguish three facets of effect sizes: dimension, measure, and value. The dimension is the underlying psychological construct being studied (e.g., anxiety). The measure is the formal statistical representation used to quantify this dimension (e.g., the difference between group means), while the value is the numerical outcome of that measure. Among these, the measure is the most critical for methodological concerns, as it determines how well the construct is operationalized and what kinds of inferences can be drawn from the numerical value.

Understanding the role of effect sizes in psychological research requires closer examination of the different types of effect size measures and the specific interpretive challenges they entail. The following sections outline key distinctions between standardized and unstandardized effect sizes, along with their respective advantages and limitations in empirical practice. To further investigate how effect sizes are currently used and understood within psychological research, two empirical studies are presented: one examining how researchers report and interpret effect sizes in practice, and another exploring potential misinterpretations of standardized effect sizes when used for inferential purposes.

Unstandardized effects and standardized effect sizes

The terminology surrounding effects and effect sizes is not always consistent in the literature. Some researchers use the term “effect size” broadly to refer to any numeric summary of study outcomes, including raw differences between groups or conditions (Cumming & Calin-Jageman, 2017; Kelley & Preacher, 2012). Others—most notably Cohen (1988)—have emphasized that effect sizes should be standardized, meaning they are unitless and can be interpreted independently of the measurement scale used. This narrower definition supports the use of standardized effect sizes as a common metric for comparing results across studies that may use different instruments or scales.

In this paper, the terms unstandardized effects and standardized effect sizes are used deliberately to differentiate between these two forms. Unstandardized effects are expressed in the original units of the measurement instrument (e.g., 10 points on an anxiety scale), while standardized effect sizes are calculated by adjusting for the variability in the data, thus removing dependence on scale units. Both forms have important roles in psychological research, but they serve different interpretive functions. For detailed taxonomies and formulas, readers can consult comprehensive overviews such as those by Ellis (2010), Fritz et al. (2012), Kirk (1996, 2007), and Pek and Flora (2018).

Challenges in the interpretation of effects and effect sizes

In practice, unstandardized effects are often the most direct answers to research questions. They are absolute measures indicating the actual size of a change, difference, or relationship using the original scale of the measurement tool. For example, an intervention might reduce depressive symptoms by five points on a given depression inventory. This type of result provides a clear, interpretable indication of how much change has occurred, in terms that are specific to the context and the instruments used.

However, interpreting these unstandardized effects can be challenging, especially when the scales are arbitrary or lack an established unit of measurement. Many psychological constructs—such as self-esteem, anxiety, or motivation—are measured using rating scales that have no inherent zero point and no agreed-upon units. Such scales are constructed according to various conventions, and their numerical values often reflect ordinal rankings or approximate intervals rather than meaningful quantities. As Abelson (2012), Baguley (2009), Cohen et al. (1999), and Witte and Zenker (2021) have observed, this lack of standard units complicates the task of interpreting raw score differences and drawing generalizable conclusions.

The flexibility that comes with creating new measurement instruments can be a double-edged sword. Researchers are free to tailor instruments to specific study goals, but this also increases the interpretive burden. If a study reports a three-point improvement on a self-report anxiety measure, for instance, the significance of that change cannot be assessed without a deep understanding of what the scale measures, how it was constructed, and how those three points relate to the real-world phenomenon of anxiety. Unfortunately, there are few standardized methods for establishing the practical significance of such effects. Each case often requires a detailed, context-sensitive interpretation, which is both time-consuming and potentially contentious. As Callahan and Reio (2006) note, without a common metric, judgments about the meaningfulness of effects might become subjective and open to criticism.

To deal with these issues, researchers have pursued several strategies. One is to develop scales that more closely approximate interval or ratio levels of measurement. Another is to rescale existing instruments using methods like the percent of maximum possible score (POMP; Cohen et al., 1999), which maps values onto a 0–100 scale. A third—and by far the most common—strategy is to standardize effects, yielding unitless indices such as Cohen’s d, Pearson’s r, or Eta-squared. These standardized effect sizes facilitate comparisons across studies by expressing effects in terms of variability, rather than raw scale units.

Standardized effect sizes are particularly useful when researchers wish to aggregate findings across multiple studies, such as in meta-analyses. Because they adjust for differences in measurement scales, they provide a common language for summarizing effects from diverse sources. However, it is crucial to recognize that standardization introduces a shift in interpretation: the effect is no longer understood in absolute terms, but relative to the variance observed in the data. As Cohen emphasized (1962, 1969, 1988), standardized effect sizes should be interpreted by comparing them to similar effects in the same research domain, or, if no such benchmarks exist, by cautiously using commonly accepted conventions for small, medium, and large effects.

Yet, relying solely on standardized effect sizes can lead to important misinterpretations. For instance, imagine reporting that the average price of goods in supermarket B is 0.1 standard deviations higher than in supermarket A. While technically accurate, this statement conveys little to no practical information—especially if we don’t know what a standard deviation represents in this context. It would be far more informative to say that the average price difference is 50 cents. In this example, price has a natural unit (money), and standardization actually obscures understanding rather than clarifying it.

In psychology, the situation is further complicated by the absence of such natural units. Without them, researchers must rely on labor-intensive explanations of the scale used, the range of scores, and the practical significance of differences. There are several ways to justify the smallest effect size of interest (SESOI; see, e.g., Lakens et al., 2018). A SESOI can be defined objectively, for example when theoretical models make quantitative predictions, when perceptual thresholds such as just-noticeable differences are relevant, or when minimal clinically important differences have been empirically established. More often, however, the SESOI must be determined subjectively. Possible strategies include relying on benchmarks (though this is considered the weakest justification), deriving the SESOI from previous studies (e.g., using meta-analytic estimates), or defining it based on practical resource constraints such as the feasibility of an intervention. There is ample evidence from research on minimal important differences and just noticeable differences showing that respondents can perceive even relatively small changes on rating scales. For example, Brühlmann (2023) examined judgments of website aesthetics using a 7-point Likert scale and found that a mean difference of only about 0.46 points already constituted a perceptible and meaningful change for participants. Similarly, work on minimal clinically important differences in health outcomes demonstrates that the smallest subjectively noticeable improvement is often a small fraction of the total scale range (e.g., Norman et al., 2003; Vanier et al., 2021). A non-clinical example is demonstrated, for instance, in Schäfer (2023), where changes in unstandardized effects on variables such as stress, wellbeing, self-efficacy, and social relatedness were evaluated following a four-week online choir intervention. In that study, the interpretation began with a substantive consideration of what magnitude of change—expressed in the original scale units—would be practically notable or meaningful for each construct, providing a grounded basis for interpreting the observed effects.

However, the complexity of interpretation may tempt researchers to bypass unstandardized effects altogether and rely solely on standardized effect sizes. While this may appear to offer objectivity and simplicity, it can result in a superficial understanding of the data. The convenience of using conventions may come at the cost of failing to engage deeply with what the data actually reveal. The reliance on standardized metrics echoes a broader tendency in psychological research to prioritize formal statistical procedures—such as significance testing—over substantive interpretation, a concern that has been raised in various critiques of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST). Kirk (1996, p. 755) encapsulates this concern well: “It is a curious anomaly that researchers are trusted to make a variety of complex decisions in the design and execution of an experiment, but in the name of objectivity, they are not expected or even encouraged to decide whether data are practically significant.” Standardized effect sizes offer a solution to the problem of arbitrary scales and are essential for many forms of quantitative synthesis. However, there is a real danger that they will be misinterpreted as conveying absolute information about the magnitude or importance of an effect (Abelson, 2012; Baguley, 2009; Gelman et al., 2020; McElreath, 2018; Meehl, 1967, 1978).

Standardized effect sizes play a critical role in assessing the detectability of effects—that is, how large an effect needs to be to be reliably detected given typical levels of measurement error and sampling variability in psychological researchFootnote 1. This perspective, emphasized in Cohen’s original work, is fundamental to statistical power analysis and informs key decisions in study design, such as determining appropriate sample sizes. Standardized effect sizes help researchers understand how hard or easy it is to detect an effect, which is unrelated to practical or theoretical importance but still highly relevant for planning empirical research. From this vantage point, conventional benchmarks—though arbitrary—serve as heuristics for assessing feasibility rather than substantive meaning. While this functional interpretation of effect sizes is widely accepted and practically useful, especially for evaluating study sensitivity, it is not the focus of the present article. Our emphasis lies on the conceptual interpretation of study outcomes and the distinction between standardized and unstandardized effects, rather than their application in study planning or power estimation. The same applies to null hypothesis significance testing of effect sizes, which has often been used to analyze whether a found effect can be clearly distinguished from a random finding. Understanding how large an effect is, and what that means in theoretical or practical terms, is equally crucial for cumulative science, theory evaluation, and real-world application. The focus in this article is therefore not on inference testing, but on the interpretation and implications of the magnitude of observed effects. The transition from traditional significance testing to emphasizing effect size estimation in psychological research reflects a broader reevaluation of statistical analysis practices. The American Psychological Association’s recommendations have encouraged psychologists to adopt an estimation framework, focusing on effect sizes and confidence intervals for a more informative analysis (Cumming et al., 2012). Literature reviews highlight that while statistical significance testing remains prevalent, the recognition of effect sizes is growing, with most recent textbooks covering both topics (Capraro and Capraro, 2002).

In addition to the distinction between standardized and unstandardized effect sizes, another key consideration in interpreting study results is the degree of uncertainty associated with these estimates. Confidence intervals (CIs) for effect sizes are an essential extension to the point estimation of effects, as they provide information about the precision and plausible range of the estimated population parameter (e.g., Fritz et al., 2012; Thompson, 2007). Rather than relying solely on a single effect size value, confidence intervals allow researchers to evaluate the degree of uncertainty associated with the estimate, taking into account sample variability and study design. This is especially important in psychological research, where small samples and noisy measurements are common, and where overinterpretation of point estimates can lead to misleading conclusions. Confidence intervals also support cumulative science, as they facilitate the comparison and synthesis of findings across studies, particularly in meta-analytic frameworks. Moreover, CIs encourage a shift away from dichotomous decision-making based solely on significance testing, promoting a more nuanced interpretation of empirical results. Despite their central relevance to effect size interpretation, the theoretical and practical implications of confidence intervals are not the focus of the present article and will therefore not be addressed in detail here.

Potential misinterpretations of standardized effect sizes

Neglect of unstandardized effects

A common error is to treat standardized effect sizes as fully self-contained interpretations of results. This is problematic because standardized values depend on the variability in the data, which can vary greatly across studies. Person-related variance in psychological studies can differ substantially across contexts due to factors such as research design, sample characteristics, cultural background, and methodological paradigm (e.g., Anusic & Schimmack, 2016; Kuppens et al., 2008; Podsakoff et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2021). For instance, research has shown that psychological measures often display reduced variance in some cultural groups, such as East Asian populations, due to reference-group effects and culturally influenced response styles like modesty or acquiescence, which can constrain the range of responses and compromise cross-cultural comparability (Heine et al., 2002; van de Vijver & Leung, 2021). Thus, the same unstandardized raw effect can yield very different standardized values if the sample variability differs. Assuming that an effect size of d = 0.2 always represents a “small” effect is therefore misleading unless the comparison is confined to a very narrow research context with consistent parameters.

Effects in different subject areas

Another concern is the improper comparison of standardized effect sizes across different domains or paradigms. An effect size of d = 0.2 might emerge in both a cognitive task and a social intervention, but this does not mean the effects are equivalent in magnitude or significance. Such comparisons ignore the substantive and methodological differences that define each research area. As Schäfer and Schwarz (2019) have demonstrated, average effect sizes vary substantially across psychological subdisciplines, suggesting that domain-general conventions are inappropriate. Cohen (1988) himself cautioned: “The terms ‘small,’ ‘medium,’ and ‘large’ are relative, not only to each other, but to the area of behavioral science or even more particularly to the specific content and research method.” Nevertheless, reference to conventions—especially those following Cohen (1988)—remains common practice in many areas of psychological research, despite substantial and well-founded criticism from methodological experts (e.g., Baguley, 2009; Funder & Ozer, 2019; Lakens, 2013; Lenth, 2001; McGrath & Meyer, 2006; Schäfer & Schwarz, 2019). These critiques have emphasized that such benchmarks lack contextual sensitivity, may distort interpretation, and are often misused outside the scope Cohen originally intended.

In contrast, unstandardized effects preserve the context of measurement and are less likely to be misinterpreted when used properly. They tell us directly what changed, by how much, and in what units. While they may lack generalizability across studies, they avoid the illusion of comparability that can arise from standardized metrics.

Effects for testing theories

Theory testing offers another example of the limitations of standardized effect sizes. Ideally, theories would yield precise predictions (point hypotheses), as in the physical sciences. In psychology, however, predictions are often approximate or directional due to measurement limitations and human variability (Serlin & Lapsley, 1985; Trafimow, 2023; Yarkoni & Westfall, 2017). Nonetheless, theory-based expectations often concern absolute quantities. If a theory predicts that an intervention will extend life expectancy by 10 years, the relevant evidence is a 10-year difference—not the standardized value of that difference. Inter-individual variance, while important for sampling and generalization, is not the central issue when evaluating whether the effect occurred as predicted.

As psychological theories typically do not include explicit expectations about person-related variance in between-subject designs, standardized effect sizes—which depend on this variance—often go beyond the scope of what the theory predicts. However, we acknowledge that in some domains, theories do incorporate variance predictions or address detectability directly, and in such cases, standardized effect sizes may be more directly aligned with theoretical expectations (e.g., Molenaar, 2004). In within-subjects designs, where each participant serves as their own control, this issue is less pronounced. But even in such cases, overreliance on standardized metrics can distort conclusions.

Objectives of the current studies

In summary, a recommended procedure for interpreting study results in psychology would be to always interpret the unstandardized effect first and then, optionally, a standardized effect size for the relative comparison of one’s own study result with those of similar studies. Although the unstandardized effects are reported in most articles (usually in tables showing the descriptive results), they are often not explicitly discussed and interpreted in the text. Instead, the focus is usually directly on the standardized effect sizes. Study 1 aims to empirically examine this impression and to analyze the specific strategies used by researchers to interpret effects. While several methodological guidelines encourage reporting both standardized and unstandardized effect sizes, little is known about how researchers actually reason about and apply these recommendations in practice. Rather than analyzing published literature, the present study investigates how researchers themselves report using and interpreting effect sizes in their own work. Study 2 uses vignettes on specific research questions to examine in more detail how sensitive researchers are to the distinction between unstandardized effects and standardized effect sizes.

There is a long tradition of acknowledging problems in the use and interpretation of effects and effect sizes as well as alternative ways of analyzing and interpreting empirical data (e.g., Baguley, 2009; Cohen et al., 1999; Cumming, 2014; Ellis, 2010; Funder & Ozer, 2019; Kelley & Preacher, 2012; Kirk, 2007; Pek & Flora, 2018; Rosnow & Rosenthal, 2009), yet little change has occurred. The two studies presented in this article aim to provide empirical support for the salience and scope of these problem areas to lend greater force to calls for change.

Study 1—current practice of calculating and reporting unstandardized effects and standardized effect sizes in psychological research

Study 1 examined the predominant strategies used by researchers and lecturers in psychology to report and interpret effects and effect sizes. Based on the expectations outlined above, the most prevalent strategy is one that largely avoids reporting and interpreting unstandardized effects and instead considers only standardized effect sizes. It was also expected that researchers would primarily rely on conventional benchmarks when interpreting the meaningfulness of effect sizes.

Method

Sample

In Germany, all universities with an institute or department of psychology were identified. In other countries (UK, Italy, Spain, France, USA, Canada, Australia, Japan, China), some universities were randomly selected. This broader inclusion did not follow a structured cross-national design but rather intended to capture potentially diverse views on methodological practices from researchers working in similar academic systems. Individuals who were listed as academic staff were identified on their websites. In total, ~2900 researchers based in Germany and 1920 international researchers were contacted via email invitations. They were invited to participate in a survey on the use and interpretation of effects and effect sizes in psychology and they were provided with a link to the online questionnaire. A total of 337 completed questionnaires were analyzed (response rate ≈ 7.2%; 51% female, 47% male, 0.6% diverse [non-binary or other gender identities]; mean age = 36 years, SD = 10.4). Most of the respondents were research associates (N = 143, 42.4%) or postdocs (N = 97, 28.7%), followed by professors (N = 83, 24.6%). Eighty-eight respondents (26.1%) indicated that they were involved in teaching research methods/statistics. Since most of the questionnaires were sent out in Germany, most of the responses came from Germany (84.0%). As with many voluntary online surveys, the modest response rate introduces the possibility of non-response bias. It is plausible that individuals with a particular interest in research methodology were more likely to participate, which may limit the generalizability of the findings.

Material and implementation

The current practices of reporting and interpreting effects and effect sizes were assessed with six questions. All questions were presented in a single-choice (forced-choice) format. They were developed specifically for this study through thorough consideration of the methodological and theoretical issues discussed in the introduction. Although the items were not pretested or adapted from existing instruments, they were carefully designed to capture key aspects of current debates regarding the interpretation of effect sizes in psychological research. Q1: How do you typically report effects/effect sizes and/or inferential statistics in your own publications? This question asked whether researchers report effect sizes at all, and how these relate to inferential statistics. Q2: In which form do you typically report effects/effect sizes? This question asked whether primarily unstandardized effects, standardized effect sizes, or both are reported, or whether the respondents vary this depending on the context of the research question. Q3: On what basis do you typically interpret the size of an effect in your publications? This question asked whether an explicit interpretation is made at all (or whether the effects/effect sizes should speak for themselves), whether the strategy of relative comparison is used (results from similar studies in the literature), whether the interpretation is based on a theoretically or practically justified minimum effect, or whether common conventions are used for the interpretation. Q4: If you refer to established conventions, which do you typically use? This question asked about the predominant conventions used for interpretation. In recent years, a number of empirically-based current conventions have been proposed, some of which are overarching (Funder & Ozer, 2019; Hemphill, 2003), and some of which are field- or topic-specific, such as for personality psychology (Gignac & Szodorai, 2016), social psychology (Richard et al., 2003), or memory psychology (Morris & Fritz, 2013). These were given as response alternatives alongside the established conventions of Cohen (1988). Q5: On what basis shall your students interpret the size of empirical effects? The purpose of this question was to determine whether teaching differs from the pattern observed when respondents report on their own research and publishing. It was also intended to determine whether there might be a discrepancy between the ideal (as taught in class) and reality (own publications). Q6: Due to the replication crisis, how strongly do you feel that established conventions should be revised and adjusted? Respondents could answer on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 11 (very strongly). This question was designed to assess researchers’ sensitivity to issues of publication bias, the strong manifestation of which has highlighted the replication crisis in psychology, and which leads to major problems in the use of the strategy of relative comparison (see above).

After being informed about the content and aims of the study and about data protection, the respondents gave informed consent (including anonymous and voluntary participation, data collection, data processing and publication of results). They were then first asked about their age, gender, and academic position before being presented with the specific questions.

Results and discussion

Reporting of effects/effect sizes and inferential statistics

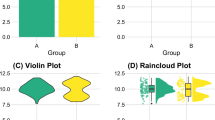

Fortunately, the strategy of exclusively reporting inferential statistics without reference to effects/effect sizes hardly exists anymore, while the strategy of reporting both is predominant (Fig. 1A).

Note. A Question 1: How do you typically report effects/effect sizes and/or inferential statistics in your own publications? B Question 2: In which form do you typically report effects/effect sizes? C Question 3: On what basis do you typically interpret the size of an effect in your publications? D Question 5: On what basis shall your students interpret the size of empirical effects?

Reporting of unstandardized effects and/or standardized effect sizes

It was suspected that unstandardized effects were rarely adequately accounted for and that standardized effect sizes were reported instead. This assumption was supported (Fig. 1B). The majority of respondents focus on standardized effect sizes. Nevertheless, a quarter of respondents reported both, and about one fifth stated that their reporting depended on the research context.

Interpreting the size of effects

The second central assumption was that effects/effect sizes are predominantly interpreted by comparing them with established conventions. This assumption was also supported (Fig. 1C). Half of the respondents make such a relative comparison and evaluate the effects/effect sizes according to the conventions as small, medium, or large. One fifth of the respondents do not rely on conventions for this relative comparison but refer to previously published effects/effect sizes within the same topic area. The elaborate and appropriate strategy of an absolute interpretation—that is, interpreting effects in the light of theoretical or practically defined minimum expectations—was reported as their typical approach by fewer than 10% of respondents. This result most clearly shows the methodological imbalance in interpreting unstandardized effects versus standardized effect sizes in psychological research outlined above.

Use of conventions

When researchers make relative comparisons of standardized effect sizes based on established conventions, 84.9% of the time they rely on Cohen’s (1988) benchmarks. In 8.0% of cases, alternative conventions are used, such as those proposed by Funder and Ozer (2019), Gignac and Szodorai (2016), Hemphill (2003), Morris and Fritz (2013), and Richard et al. (2003). An additional 4.7% refer to other authors, while 16.6% of respondents reported that their choice of conventions varies depending on the context. It remains unclear whether this pattern reflects a lack of awareness of the limitations of general conventions or unfamiliarity with more domain-specific alternatives. Nonetheless, these findings suggest a widespread reliance on a potentially problematic strategy—one that may hinder scientific progress in psychology by neglecting a nuanced evaluation of empirical results in terms of their theoretical or practical significance.

Recommendation to students

Interestingly, the previously observed pattern shifts markedly when considering what respondents communicate to their students. Here, a majority advocates alternative strategies, with far fewer endorsing the use of conventions (Fig. 1D). However, the results also show that only about one-tenth of the respondents recommend making an absolute comparison and thus assessing the theoretical or practical meaning of an empirical effect.

Perceived need to revise conventions in light of the replication crisis

This item assessed how strongly respondents felt that current reporting standards and conventions should be updated in response to concerns raised by the replication crisis. Respondents appear highly sensitive to the impact of the replication crisis on the usefulness of established conventions. On a scale from 0 (not at all) to 11 (very strongly), most respondents gave high to very high values (Mdn = 8, IQR = 3) to the question of whether the replication crisis necessitated a revision of existing conventions. This suggests an awareness that conventions for interpreting effects/effect sizes do not exist in a vacuum, but are contingent on a robust empirical foundation. This makes the rather low awareness of the problems of using general conventions (see above) all the more surprising. This suggests a discrepancy in awareness: respondents recognize the general limitations of the published empirical basis but overlook the subject-specific variability in effect size distributions.

Study 2—potential problems in interpreting standardized effect sizes

The widespread use of standardized effect sizes (Study 1) provided the basis for Study 2, which examined in more detail how Cohen’s d, as a typical example of a standardized effect size measure, is interpreted. As noted above, the meaningfulness of standardized effect sizes—compared to unstandardized effects— is often limited, particularly regarding practical significance or relevance for testing theoretical predictions. The widespread use of standardized effect sizes could therefore be a source of potential misinterpretation. The study presented four typical scenarios commonly encountered in psychological research. For each scenario, possible answers regarding the meaningfulness of a standardized effect size were formulated and respondents were asked to choose among them. Specifically, the meaningfulness of standardized effect sizes was examined with respect to (1) the efficacy of a practical intervention, (2) the expectation of efficacy of an intervention for a single individual, (3) testing a theoretical prediction, and (4) comparing effects from different studies. In all four scenarios, the informative value of standardized effect sizes was limited. Specifically, in these cases, standardized effect sizes alone, without adding further information such as means, variances, or study context, are not sufficient to answer the research question satisfactorily.

Method

Sample

All academic staff engaged in research and/or teaching at a psychological institute or department in Germany were individually contacted by e-mail and invited to participate in a survey on the interpretation of effects and effect sizes in psychological research. If interested, the contacted individuals could click on a link to the online survey. After being informed about the content and aims of the study and about data protection, respondents gave informed consent (including anonymous and voluntary participation, data collection, data processing and publication of results). They were then asked about their age, gender, and academic position, and then presented with the specific questions. Unlike in Study 1, students were also invited to participate via random distribution through mailing lists in order to detect possible discrepancies in responses between lecturers in research methods/statistics and researchers on the one hand and students on the other. Because the total number of mailing list recipients was unknown and may include overlapping contacts, an exact response rate cannot be calculated. A total of 468 respondents completed the survey. The distribution of age and gender is shown in Table 1. Data collection for Study 1 and Study 2 was approximately one year apart.

Material and implementation

All respondents were presented with research questions about four scenarios and were given the opportunity to select an answer from a predetermined list of answers (primary response options). This design was inspired by the classic studies of Oakes (1986) and Haller and Krauss (2002), in which the correct interpretation and meaningfulness of p-values were investigated by means of a predefined list of response alternatives from which one or more could be selected. All four scenarios referred to the case of a given standardized mean difference, which is typical in psychological research, and which was presented as Cohen’s d. The single-choice questions included answers suspected to reflect the most common but suboptimal or insufficient strategies for interpreting standardized effect sizes. Of the response options, only one was the optimum, namely that the research question formulated could not be answered without further information. Only if respondents selected this option were they asked on the next page what information they thought would be necessary to answer the research question adequately. The secondary response options following each scenario were presented in a multiple-choice format, allowing participants to select multiple options. The list of available response options was developed based on a careful consideration of the types of statistical information typically available to researchers after conducting data analyses in psychological research. The intent was to simulate a realistic decision-making context in which researchers must judge the interpretability of results based on commonly reported statistical outputs. Each scenario had only one optimal answer, except for the fourth scenario, which had two. Figure 2 shows the four scenarios presented and the primary and secondary response options.

Scenario 1: effectiveness of an intervention

This is a standard scenario in psychological research in which the effect of an intervention or manipulation is analyzed. The research question concerns the interpretation of the meaningfulness of the effect. An applied context (intervention) was deliberately chosen to make the question of the study result’s practical relevance particularly salient. Study 1 showed that standardized effect sizes and their conventional interpretation are predominantly used. Thus, if respondents followed this strategy, they were expected to choose option A (“Yes; because the effect is medium-sized according to Cohen’s conventions”) or option D (if they relied on conventions that differ from Cohen’s). However, as discussed in the introduction, this is not an optimal strategy for addressing the research question, as standardized effect sizes have limited validity in evaluating practical meaningfulness. A more adequate assessment requires knowledge of the scale (i.e., the measurement instrument used) and the unstandardized effect (i.e., the mean difference). Relative comparisons based solely on standardized effect sizes are hardly informative. The optimal solution for this scenario would therefore be option C for the primary question and option A for the secondary question.

Scenario 2: expectation of an individual effect

This scenario focuses even more strongly on the practical meaningfulness of the study result. Specifically, it asks how much an outcome is expected to change when an individual undergoes an intervention previously tested in the described study. Because this scenario refers to a single individual, person-related variance is not relevant—thus, the standardized effect size is not meaningful. Only the unstandardized mean difference is suitable to answer the question. The optimal solution here is option C for the primary question and option A for the secondary question.

Scenario 3: testing a theoretical prediction

This scenario describes testing a theoretically predicted effect using an observed effect. Since theories typically do not include assumptions about person-related variance in between-subject designs, a theoretical prediction can only be compared to an unstandardized effect—again, the mean difference. The optimal solution for this scenario would be option D for the primary question and option A for the secondary question.

Scenario 4: comparison of the meaningfulness of two effects

As in Scenario 1, this scenario concerns the practical meaningfulness of an observed effect. The reference to a replication in a different cultural setting was intended to draw attention to the fact that comparisons of intervention effectiveness must take into account inter-individual variance. This scenario assumes that the same constructs are measured using the same instruments in a comparable setting, allowing for basic comparability. However, what cannot be inferred from the scenario—and should not be assumed—is that the variances in both populations are also comparable. Cultural (or other contextual) differences can increase or decrease measurement variance. Since variance is part of the calculation of standardized effect sizes, they are only comparable if the underlying variances are similar. Otherwise, the same effect (mean difference) could result in a small or large effect size depending on the variance. Conversely, effects of different sizes could appear similar when standardized with different variances. Thus, the optimal solution for this scenario would be option D for the primary question and option A or F (or both) for the secondary question.

Results and discussion

Since the primary questions allowed only one answer and only one option was optimal, the proportion of optimum answers is presented below. The secondary questions are a bit more nuanced. Here, the respondents were allowed to select many options, as it can generally be advantageous to obtain as much information as possible about a study result. Therefore, as described above, only one or two optimum responses were included but the selection of many options was also recorded as correct, provided, of course, that the optimum response was included.

Scenario 1: effectiveness of an intervention

About half of the respondents considered the use of Cohen’s (Option A) or other conventions (Option D) to be sufficient to assess the meaningfulness of the reported effect (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, 50.9% requested further information. However, most of these respondents then stated that they would need the sample size to be able to answer the research question. The reasoning behind this could be that an effect found can only be reliably interpreted in terms of its meaningfulness if the underlying sample is not too small. This is, of course, a perfectly valid consideration, but it is not yet the optimum answer to the secondary question, at least not in isolation. After all, the optimum response A was chosen by only 48.6% of the respondents. It is noteworthy at this point that a remarkable proportion of respondents requested inferential statistics (p-value, standard error, power) to assess the meaningfulness of the effect. Respondents who selected the “other” option were able to enter an individual answer in a free-text field. These responses were individually assessed to determine whether they corresponded to the optimum solution and coded as adequate or inadequate accordingly. For example, some respondents indicated that the confidence interval for the reported effect size was necessary for assessing the meaningfulness, which is a reasonable but not sufficient consideration (because confidence intervals indicate the precision of an estimate but do not by themselves determine whether an effect is substantively meaningful). However, some respondents paraphrased the information we were looking for in their answers, for example, by describing that precise knowledge of the scaling of the outcome variable would be needed to assess the meaningfulness of the study result or that expert judgment could provide a good basis. Such responses were coded as adequate. For 13 respondents (6.1%), this resulted in an optimum response to the secondary question, even though they did not directly select Option A. Overall, therefore, 54.7% (48.6% + 6.1%) of respondents selected the optimum response to the secondary question. The 50.9% optimum responses to the primary question and the 54.7% optimum responses to the secondary question result in a total of only 24.8% of all respondents dealing optimally with the problem in Scenario 1.

Scenario 2: expectation of an individual effect

For Scenario 2, 58.1% of the respondents recognized that the question cannot be answered without further information (Fig. 3). Of these respondents, the majority (54.4%) then also selected that they would need the mean difference. The fact that here, too, a large number of respondents asked for the sample size may be due to the same reasoning as in Scenario 1. Again, there was a large proportion of respondents who requested results of inferential statistics in order to answer the question about the expectation of an individual change. For 21 respondents (8.7%), the answer to the secondary question could be considered adequate even though they did not directly select Option A. Thus, 63.1% (54.4% + 8.7%) optimally responded to the secondary question. The 58.1% optimum responses to the primary question and the 63.1% optimum responses to the secondary question result in a total of only 32.5% of all respondents who optimally handled the problem in Scenario 2.

Scenario 3: testing a theoretical prediction

A large proportion of respondents (68.6%) recognized that testing a theoretical prediction requires more information than just the standardized effect size (Fig. 3). The inadequate or insufficient responses show an equal distribution, so no trend can be seen here. Although most respondents (58.3%) to the secondary question indicated that they needed the mean difference, again a large proportion asked for inferential statistics, which might be based on the consideration that frequentist inferential statistics allow for “hypothesis testing” and therefore would provide information about the precision of a theoretical prediction. For 16 respondents (5.5%), the answer to the secondary question could be evaluated as adequate, although they did not directly select Option A. Thus, 63.8% (58.3% + 5.5%) answered the secondary question optimally. The 68.6% optimum responses to the primary question and the 63.8% optimum responses to the secondary question result in a total of 39.5% of all respondents who optimally handled the problem in Scenario 3.

Scenario 4: comparison of the meaningfulness of two effects

This scenario was certainly the most difficult, as reflected in the responses. The majority of respondents (56%) concluded that the effect in the follow-up study was somewhat smaller, but in principle comparable to the original effect, overlooking the fact that comparability is only possible with simultaneously comparable variances (Fig. 3). Only 27.8% asked for further information. In the secondary question, 63.3% of the respondents requested information either on the comparability of the variances (Option A) or on the unstandardized effect (Option F). For 3 respondents (2.8%), the answer to the secondary question could be considered adequate even though they did not directly select Option A or F. Thus, 66.1% (63.3% + 2.8%) optimally responded to the secondary question. The 27.8% optimum responses to the primary question and the 66.1% optimum responses to the secondary question result in a total of only 15.4% of all respondents who optimally handled the problem in Scenario 4.

Comparison of the subgroups

The results presented above are for the total sample. In addition, the differences in the rate of optimum responses between the different subgroups were exploratively analyzed. Figure 4 shows the percentages of optimum responses to the primary questions and secondary questions separately for lecturers, researchers, and students. For Scenarios 1 and 4, a slight trend can be seen, which is not surprising: the lecturers solved the tasks slightly better than the researchers and the researchers slightly better than the students. In Scenarios 2 and 3, however, the researchers fall out of this trend and showed the best understanding of the problems in each case. This difference is especially evident in Scenario 3. One reason for this could be that researchers, through their daily scientific work, are the group that is closest to the topic of theory development and theory testing, so that they might be particularly sensitive to this issue.

Number of additional answers

To assess whether selecting a large number of response options was systematically associated with selecting the correct answer, we conducted an exploratory analysis. For each scenario, we computed the number of additional response options selected by participants (excluding the correct answer) and calculated the point-biserial correlation between this number and response correctness (coded 0 = incorrect, 1 = correct). As shown in Table 2, the correlations were weak across all scenarios (ranging from r = –0.12 to r = 0.30), indicating that the number of additional answers selected was not strongly related to whether a participant chose the correct option. These results suggest that participants who responded correctly were not merely selecting many options indiscriminately.

General discussion

The most common goal of empirical studies in psychology is to analyze and quantify a difference (between groups or conditions) or a relationship (between two or more variables). Data analysis is usually divided into two steps. In a descriptive-analytical step, parameters are calculated to provide an answer to the research question or to allow an assessment of the research hypothesis. Because these parameters are based on sample data, an inferential-analytic step follows to assess the reliability of the estimate of the true population parameters based on the sample parameters. These two steps are fundamentally different: descriptive analysis identifies and interprets the effect that answers the research question (Is there an effect in the expected direction and how large is it?); inferential analysis assesses the parameters that affect the reliability of generalizing this effect to the population, namely the dispersion of the data and the sample size. Confusing or mixing these two analytical strategies can lead to problematic interpretations of empirical results. This includes, for example, the assumption that one can only interpret the meaning of an effect if it has been shown to be significant in inferential statistics. But it also includes the assumption that standardized effect sizes can provide a sufficient answer to a research question—an assumption that is not justified in many cases, as highlighted in the introduction. To answer a research question—that is, in the course of descriptive data analysis—it is usually the unstandardized effect that is needed, and the standardized effect size is often not only unnecessary but can even obscure the true message that is in the data.

Standardized effect sizes are a hybrid of descriptive and inferential data analysis

The reason why the interpretation of standardized effect sizes is so complicated is probably that these are neither purely descriptive nor purely inferential parameters. They are, so to speak, a hybrid of both. On the one hand, they contain the unstandardized effect, for instance, a mean difference between two groups. Descriptively, this is the crucial empirical result that provides an absolute answer to the research question (e.g., Abelson, 2012; Baguley, 2009). On the other hand, they also contain the dispersion of the data, such as the pooled standard deviation of the two groups (as in the case of Cohen’s d). Standardization transforms the effect into a relative measure, dependent on the variance in the data. Incorporating the dispersion turns an effect size into a statistic that can be viewed as a precursor to an inferential statistical parameter. For a mean difference, for example, researchers ask whether it is clearly detectable as an effect (small dispersion) or difficult to detect in the noise of the data (large dispersion). In other words, it is a question of assessing the reliability of the two means and thus of the mean difference itself. Large dispersion means that the means and thus the mean difference can be estimated less accurately because it would lead to a large sampling error if the data collection was repeated. (For this reason, in addition to sample size, the dispersion of the data is included in the calculation of the standard error, which is the basis of inferential statistical measures and tests). The same unstandardized effect may therefore be associated with very different magnitudes of a standardized effect size, depending on how large the variance is. Thus, a large standardized effect size suggests that the effect is statistically detectable relative to the variability in the data, but it does not necessarily imply that the effect is substantively large or meaningful. Without knowing the scale and variance of the original measurements, it is difficult to judge the absolute size or practical importance of the effect.

Problems with the interpretation of standardized effect sizes

The initially encouraging result in Study 1 was that effects/effect sizes are almost always reported and interpreted, and that the strategy of reporting only inferential statistics virtually no longer exists. This is a clear improvement compared to the situation ten (A. Fritz et al., 2012) or twenty (Kirk, 1996) years ago (see Schäfer, 2018). However, when asked whether unstandardized effects, or rather standardized effect sizes, are interpreted, it was found that most respondents come directly to the interpretation of the standardized effect sizes and pay less attention to the unstandardized effects. This is problematic for at least any research question involving differences between groups or conditions, since it effectively eliminates the answer to the research question (how large is the difference?). It would be less problematic for research questions that are essentially about the association of two variables, that is, the strength of their correlation. In this case, the variance must be included, since the research question is precisely how well the variance of one variable can be explained by the variance of the other. It is important to remember, however, that behind such a superficial question there is always the question of the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals. If, for example, the correlation between the number of likes on social media and life satisfaction is quantified as r = −0.15 (Shakya & Christakis, 2017), then this does not comprehensively answer the question of the actual effect behind this result. When it comes to the meaning of this result for individuals, the question becomes “how much” does life satisfaction change with “what specific” change in the number of likes? Whether this change is a meaningful one, whether it is important for people’s lives, whether it is worth intervening by taking action, etc.—these are questions that can only be answered by the unstandardized effect (which, in the case of association between variables, can be expressed by the unstandardized regression coefficient b). The neglect of the unstandardized effects when assessing the meaningfulness of study results may be an indication that the handling of data and data analyses in psychological research has sometimes taken on a life of its own, and that the connection to the psychological research questions (what influences the mental and behavioral characteristics and to what extent?) sometimes seems to be lost.

On average, about half of the respondents in Study 2 recognized that the standardized effect size alone was not sufficient to comprehensively answer the respective question and that more information was needed. When asked what information would be needed, an average of half of those respondents optimally indicated that the unstandardized effect (i.e., the difference in means or, alternatively, in Scenario 4, information on dispersion) would be needed. Taken together, this results in an average proportion of about a quarter of respondents who would have responded optimally to the exemplar questions. As a possible reason for this result, the peculiarity of standardized effect sizes as a hybrid between descriptive and inferential information has been discussed, which makes them rather difficult parameters. Another reason could be the peculiarity of psychology, as discussed in the introduction: most constructs are measured on arbitrary scales that have neither a natural zero point nor standard units. This leads not only to a certain degree of arbitrariness in the construction of measurement instruments, but also, consequently, to uncertainty in the handling of these constructs. While a physical quantity such as length can be measured unambiguously and it is clear to both the scientist and the layperson what a difference of ten centimeters means, psychological constructs are less tangible. Without a natural zero point and standard units, there is no unambiguous interpretation of a difference of, say, three scale points on an arbitrarily designed scale. It requires a precise explanation of how the scale was developed and what exactly—expressed in terms of the empirical phenomenon being measured—the difference between two scale points corresponds to.

To avoid this effort, standardization of measurements seems to be an appropriate means to make the measurement scale-independent, thus eliminating both the missing zero point and the arbitrary units. Because standardization leads to comparability of different scales, “small” and “large” effects can now be compared relatively to each other. Yet, for many research questions that are not answered by a precise explanation and interpretation of the scale and the scale points, but only by interpreting the standardized effect size, standardization takes the form of a statistical trick. When we fall for this trick, one could provocatively say that we in psychology simply do not know what we are actually talking about (see, e.g., Yarkoni & Westfall, 2017, arguing that psychological explanations are often circular and lack substance). We indulge in measurements and analyses without knowing what is actually being measured and what the analyzed effects mean. It is not surprising, of course, that such a trick is especially effective with students. They find it more difficult to deal with the interpretation of arbitrary scales and to make an informed judgment about the size or meaningfulness of an effect. For them, a strategy that allows for a categorization as “large” or “small”—and thus falsely implies an “important” or “less important”—seems very tempting.

Problems with conventions

Study 1 revealed another problem with evaluating standardized effect sizes. The majority of respondents reported using established conventions when interpreting effect sizes. Cohen (1988) saw the strategy of using conventions as a last resort in the case that a research area is completely new and there is no prior empirical knowledge—a case that is probably a very rare exception in psychological research. That this strategy is nevertheless so widespread may be for the same reasons discussed above: Relying on conventions that one does not have to justify oneself seems more objective and is easier for everyone involved, including students, researchers, reviewers, and journal editors. Far more problematic than the use of conventions per se, however, is the finding that over 80% of the respondents relied on the same conventions, those of Cohen (1988). Cohen did not intend for researchers to rely on conventions to interpret standardized effect sizes at all, nor that they should always use the same conventions. He merely used his conventions for large, medium, and small effects as examples to demonstrate power calculations, using examples such as the height difference between 14- and 18-year-old girls for a medium effect. These examples were not intended to be universal, nor were they drawn from a systematic analysis of average effects in psychological research. As Cohen himself put it: the conventions are “no more reliable a basis than my own intuition” (Cohen, 1988, p. 532). If conventions are used at all, they should be field- and topic-specific (see also Funder & Ozer, 2019). More specifically, conventions that divide effect sizes into categories such as small or large are only valid in the context of studies with comparable constructs, comparable questions, and comparable person-related variance. In all other cases, using always the same conventions would be comparing apples and oranges. Average effect sizes vary so widely across psychological subdisciplines that comparability is impossible (e.g., Cristea et al., 2022; Funder & Ozer, 2019; Gignac & Szodorai, 2016; Ioannidis, 2008; Lovakov & Agadullina, 2021; Nordahl-Hansen et al., 2024; Richard et al., 2003; Schäfer & Schwarz, 2019; Szucs & Ioannidis, 2017; Weinerová et al., 2022). Therefore, one should, if at all, use field- or topic-specific conventions. However, as was shown in Study 1, these are rarely used.

Problems due to the publication bias

Only about 20% of respondents reported judging standardized effect sizes not by convention, but in light of the published effects of comparable studies. If standardized effect sizes are used at all, this comparative approach would be a useful strategy for interpreting them (Cohen, 1988). In the light of comparable studies, a standardized effect size can be used to assess whether one’s own found effect is more likely to be above or below average relative to them. However, this strategy assumes that published effects provide an unbiased representation of empirical research on a particular research question. That this is not the case has been shown by comparing effects from traditional publication formats (with the potential risk of bias due to publication bias) and publications with preregistration (with less risk of bias): On average, effect sizes in publications with preregistration turned out to be only about half as large (Klein et al., 2018; Open Science Collaboration, 2015; Schäfer & Schwarz, 2019; Stanley et al., 2018). This is a significant bias that makes it very difficult to meaningfully classify empirical effects within the published research landscape. An interesting finding from Study 1 was that many respondents, in light of the replication crisis, perceived the conventional benchmarks for standardized effect sizes as overly optimistic and not reflective of the effect sizes typically observed in published or replicable research. Consequently, they expressed a necessity to revise these conventions to better align with the empirical realities revealed by replication efforts. This finding is interesting because it reveals a certain sensitivity to the dependence of conventions on a background of comparable empirical effects, while at the same time using the same Cohen conventions in most cases and thus ignoring cross-disciplinary differences.

Recommendations for the interpretation of study results

In psychological research and teaching, there is a great need for improvement in the use and interpretation of quantitative results. Interpreting the size and significance of a study result should usually be done using the unstandardized effect in a first, descriptive analytic step, as in most cases this alone can provide a meaningful answer to the research question (e.g., Abelson, 2012; Baguley, 2009; Pek & Flora, 2018). In addition, calculating and interpreting a standardized effect size can be useful when comparing a result to other comparable studies or when pooling results from comparable studies in a meta-analysis. Care must be taken to ensure that the basis for comparison is as free of bias as possible. In meta-analyses, this is usually achieved by searching for gray literature and unpublished findings. In recent years, studies with preregistration or registered reports have provided results on psychological research questions that are as free of bias as possible. Relying solely on conventions should be the exception. Using conventions is possible when they are bias-free and highly field- or topic-specific.

What can an appropriate interpretation of unstandardized effects look like? It should be guided by the research object, the existing previous studies, and the measurement instruments. The research object is undoubtedly the most important criterion. For a research question that involves life or death (such as the effects and side effects of a drug), a numerically very small effect may be of great practical importance, especially if the target group or population is particularly large. An example often cited is the preventive effect of giving aspirin for myocardial infarction, which is numerically very small, but translates into a large number of individuals who would benefit from treatment relative to the large target population of potentially hundreds of thousands of individuals at risk for myocardial infarction. To express such effects, metrics like the Binomial Effect Size Display or Number Needed to Treat have been developed and are now common, especially in clinical research (see Funder & Ozer, 2019; Rosenthal & Rubin, 1982). In contrast, when researching a construct such as wellbeing, larger effects may be required to speak of a meaningful or practically useful outcome.

A central recommendation is for researchers to define, prior to data collection, what magnitude of effect would be considered meaningful on the specific measurement scale they are using. This strategy encourages clarity about theoretical expectations and fosters transparency in how results are interpreted. For unambiguous measurements, this is usually quite straightforward. If a body weight reduction method has shown an effect of, say, 2.5 kg weight loss in four weeks, each person can immediately judge whether this would be a lot or a little for him or her (also in light of the “cost” of the intervention). With psychological measures, this is usually more difficult. For example, if a scale measuring mindfulness ranges from 1 to 7, what degree of mean difference or correlation would reflect a practically or theoretically relevant effect? By articulating this in advance—ideally through pre-registration or in the study rationale—researchers establish a standard against which the obtained results can be meaningfully evaluated. This approach shifts the emphasis away from relying solely on conventional benchmarks (e.g., Cohen’s guidelines) and toward more context-sensitive interpretations. An example of this strategy can be found in the study discussed in the introduction (Schäfer, 2023), where the researchers specified an expected and meaningful effect size based on the structure of their rating scale and the goals of the study. Comparing pre-defined expectations with observed results supports a more cumulative and theory-driven research process and provides readers with clearer grounds for evaluating the implications of the findings. A similar strategy for assessing the meaningfulness of an effect size is the concept of the Minimal Important Difference (MID), which refers to the smallest change in an outcome that patients perceive as beneficial and that would justify a change in treatment. As Hengartner and Plöderl (2022) emphasize, the MID provides a patient-centered benchmark for clinical significance, which can help avoid the overinterpretation of statistically significant but trivial effects. Applying this approach requires researchers to first consider what magnitude of change would be meaningful before interpreting standardized metrics such as Cohen’s d.

Effect size interpretation is closely intertwined with the goals of open science, particularly those related to transparency, reproducibility, and cumulative knowledge building (e.g., Munafò et al., 2017). One relevant finding from Study 1 was that several respondents explicitly linked their dissatisfaction with existing effect size conventions—such as Cohen’s benchmarks—to concerns raised by the replication crisis. These respondents noted that the traditional benchmarks often overstate the practical significance of effects, particularly in fields where effects are inherently small. This sentiment aligns with broader calls in the open science community to re-evaluate interpretive norms in light of empirical realities and the need for more calibrated expectations (e.g., Funder & Ozer, 2019). Effect size interpretation, when done thoughtfully, offers an opportunity to promote transparency by encouraging researchers to clearly state what constitutes a meaningful effect size before data collection—either in pre-registrations or registered reports. This helps reduce researcher degrees of freedom in interpretation, strengthens the evidential value of findings, and supports reproducibility by allowing others to evaluate results relative to predefined thresholds. In this way, revising how we approach effect sizes is not just a statistical concern but a core part of advancing open and credible psychological science.

Limitations

The two studies presented were rather heuristically designed, meaning that there was no template from a theory, a model, or comparable past studies. Thus, the selection and formulation of scenarios and questions were based on subjective considerations and personal experience in the field of quantitative psychological research methods. Certainly, questions could have been more extensive or posed differently. Some of these alternatives could also be derived from the responses in the free text fields. Some respondents may have read the scenarios and questions less carefully, overlooking the fact that the purpose was not to make an inferential statistical assessment of the study result presented. Thus, there may be a small proportion of respondents who would have answered differently had they been asked more carefully. In this case, the rate of optimal solutions would have been somewhat better. On the other hand, the scenarios and questions might have been demanding or suggestive to some degree, so that the respondents were more reflective than usual about the meaning of the response options given. In particular, the response option “It is impossible to say without more information” may be particularly suggestive to choose when a survey is explicitly about interpreting effect sizes. Although choosing this option was objectively the correct response in the given scenarios, it cannot be ruled out that some participants arrived at this answer through test-taking caution or contextual guessing rather than conceptual understanding. Without this prompting character (e.g., through completely open-ended questions), the solution rate might then have been lower. This limits the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn about their reasoning and highlights the need for follow-up studies with alternative formats (e.g., requiring justifications or using open-ended questions) to better capture interpretive depth.

Another important limitation concerns the survey sample. The response rate was relatively low, which is not unusual when surveying busy academics without incentives, but it nonetheless restricts the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, because the survey focused on methodological practices—specifically effect size interpretation and reporting—it is likely that researchers with a particular interest or expertise in these issues were more motivated to participate. As a result, the sample may overrepresent individuals who are more methodologically engaged or critical, and the views captured here may not reflect the broader population of psychological researchers. At the same time, the perspectives of such self-selected respondents may be particularly relevant, as these are the individuals most likely to influence discussions and practices in their field. Caution is therefore warranted when interpreting and generalizing the results.

A further limitation of the current study is that participants were allowed to select multiple response options when answering the secondary question in each scenario in Study 2. This introduces uncertainty about the decision-making strategies underlying correct responses. For instance, some participants may have selected the correct option alongside several irrelevant ones, making it unclear whether their correctness reflects genuine understanding or a broad-selection strategy. Although an exploratory analysis showed that the number of additional answers selected was only weakly correlated with answer correctness, and thus mass selection does not appear to systematically account for correct responses, this ambiguity nevertheless limits the strength of inferences that can be drawn about participants’ reasoning. Future studies should consider constraining the number of options participants may select, or request justifications for their choices, to obtain more interpretable data on how individuals identify meaningful information for effect size interpretation.

Conclusion

Taken together, our findings show that while effect sizes are almost always reported, their interpretation often relies too heavily on standardized indices and conventional benchmarks. This practice risks obscuring the actual meaning of study results and encourages overinterpretation. By contrast, unstandardized effect sizes provide a more direct link to the underlying measures and are therefore essential for a meaningful interpretation. Therefore, placing greater emphasis on unstandardized effects and developing discipline-specific guidelines for standardized measures is recommended, so that effect size reporting can more fully contribute to the cumulative knowledge base of psychological science.

Data availability

All data have been made publicly available at OSF: https://osf.io/dvu6t/?view_only=59a03cad87bf4edc86f5b90781407fac.

Notes

Acknowledgment is due to Daniel Lakens for drawing attention to the fact that standardized effect sizes can be informative about the detectability of effects.

References

Abelson RP (2012) Statistics as principled argument. Psychology Press

Anusic I, Schimmack U (2016) Stability and change of personality traits, self-esteem, and well-being: Introducing the meta-analytic stability and change model of retest correlations. J Personal Soc Psychol 110:766–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000066

Baguley T (2009) Standardized or simple effect size: What should be reported?. Br J Psychol 100:603–617. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712608X377117

Broers NJ (2021) When the numbers do not add up: the practical limits of stochastologicals for soft psychology. Perspect Psychol Sci 16:698–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620970557

Brühlmann F (2023) Is a mean difference of 0.46 relevant? Towards determining the smallest effect size of interest for visual aesthetics of websites. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2305.08945

Callahan JL, Reio JrTG (2006) Making subjective judgments in quantitative studies: The importance of using effect sizes and confidence intervals. Hum Resour Dev Q 17:159–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1167

Capraro RM, Capraro MM (2002) Treatments of effect sizes and statistical significance tests in textbooks. Educ Psychol Meas 62:771–782. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316402236877

Cohen J (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Academic Press

Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken LS, West SG (1999) The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivar Behav Res 34:315–346. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3403_2

Cumming G (2014) The new statistics: Why and how. Psychol Sci 25:7–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613504966

Cumming G, Fidler F, Kalinowski P, Lai J (2012) The statistical recommendations of the American Psychological Association Publication Manual: Effect sizes, confidence intervals, and meta-analysis. Aust J Psychol 64:138–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9536.2011.00037.x

Cumming G, Calin-Jageman R (2017) Introduction to the new statistics: Estimation, open science, and beyond. Routledge

Cristea IA, Georgescu R, Ioannidis JP (2022) Effect sizes reported in highly cited emotion research compared with larger studies and meta-analyses addressing the same questions. Clin Psychol Sci 10:786–800

Ellis PD (2010) The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. Cambridge University Press

Fritz A, Scherndl T, Kühberger A (2012) A comprehensive review of reporting practices in psychological journals: Are effect sizes really enough?. Theory Psychol 23:98–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354312436870

Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ (2012) Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen 141:2–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024338

Funder DC, Ozer DJ (2019) Evaluating effect size in psychological research: sense and nonsense. Adv Methods Pract Psychol Sci 2:156–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202

Gelman A, Hill J, Vehtari A (2020) Regression and other stories. Cambridge University Press

Gignac GE, Szodorai ET (2016) Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personal Individ Differences 102:74–78

Haller H, Krauss S (2002) Misinterpretations of significance: a problem students share with their teachers. Methods Psychol Res 7:1–20

Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Peng K, Greenholtz J (2002) What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales?: The reference-group effect. J Personal Soc Psychol 82:903

Hemphill, JF (2003) Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. Am Psychol 58:78–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.78

Hengartner MP, Plöderl M (2022) Estimates of the minimal important difference to evaluate the clinical significance of antidepressants in the acute treatment of moderate-to-severe depression. BMJ Evid-based Med 27:69–73

Ioannidis JP (2008) Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology 19:640–648