Abstract

This article introduces the vignette study as a research method in foreign-language education that can be used to examine the effects and interaction of multiple variables. A vignette study presents hypothetical scenarios (i.e., vignettes) to its participants (i.e., L2 learners, L2 teachers) to investigate their self-reported attitudes, decisions, or reactions regarding these vignettes. A vignette set systematically varies attributes in its vignettes (e.g., L2 feedback type). The vignette study is thus able to identify the causal effect of these attributes on the participants’ attitudes, decisions, or reactions (e.g., learner motivation). The vignette study offers several benefits to L2 research, such as flexible research questions, analysis of multiple variables, compatibility with quantitative and qualitative assessments, and research economy. The vignette study is a valuable, but underused method to investigate complex causal interactions in foreign-language education. To illustrate the potential of the vignette study for L2 research, the article presents an exemplary vignette study with L1-German L2-English students (grade 5-9, secondary school). The vignette study examined the effect of online vs. onsite teaching (IV) on the students’ foreign-language enjoyment (DV) in the L2 English classroom and showed that their enjoyment was lowered by online teaching in the study sample (i.e., descriptive, but non-significant result).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

L2 teaching and learning can be regarded as a complex network of interconnected variables, such as learner attributes (e.g., language aptitude, motivation), teacher attributes (e.g., proficiency, enthusiasm), classroom teaching methods (e.g., Present-Practice-Produce), or learning outcomes (e.g., speaking, intercultural skills). Arguably, it is the objective of L2 research to propose and empirically assess theories that model this complex variable network, so that decisions about L2 education in classrooms can be based on increasingly evidence-based theories (Jordan, 2004, ch. 1; Lowie & Verspoor, 2019).

In this network, variables with a causal impact are of particular interest, as in the comparison of teaching methods (e.g., Present-Practice-Produce vs. Task-Based Language Teaching) and their effect on students’ L2 learning (cf. Harris & Leeming, 2022 for a PPP vs. TBLT study). At present, the key method to investigate causal effects in L2 research are quasi-experiments and experiments, in which an independent variable (e.g., teaching method) is manipulated to determine its effect on one or more dependent variables (e.g., speaking, motivation) (cf. Mackey & Gass, 2016, ch. 6 for quasi-/experiments in L2 research). While experiments, which randomly assign students to different study groups, have been called a ‘gold standard’ for research, these studies are in fact costly to conduct. Typically, carrying out an experiment involves preparing two (or three) teaching routines and pre- and posttests, teaching these routines over several lessons, and then administering pre- and posttests (often also a delayed posttest). Visibly, the preparation and conducting of experiments is thus resource- and time-intensive for L2 researchers. Presumably, this is the reason why most experiments in L2 education are done as part of PhD theses, which may take four to five years to complete.

As a result, while quasi-/experiments are the dominant study design to examine causal relationships in L2 education, they are time- and resource-heavy. At the same time, the field underutilizes another, lesser-known study design that also offers causal insights and comes with a greater cost-efficiency—the vignette study. However, the vignette study remains largely overlooked in earlier L2 research, with only a handful of vignette studies having been published to date (see Section 3).Footnote 1 To make the vignette study and its benefits for L2 research more visible—with the hope of advancing L2 education in general—, it is the purpose of this article to introduce and exemplify the vignette study for research in L2 teaching and learning.

In what follows, we first outline the vignette study in L2 research, that is, its key features and how to plan and conduct it (Section “The Vignette Study in Foreign-Language Research”). After that, we review earlier vignette studies in L2 education that have addressed diverse research topics, such as students’ pragmatic skills, motivation, or emotions (Section “Earlier Vignette Studies in Foreign-Language Research”). Thirdly, we discuss the benefits of the vignette study, including its economy, as well as its drawbacks, in particular regarding its external validity (Section “Benefits and Drawbacks for Foreign-Language Research”). Finally, we present an example vignette study that examined the effect of onsite vs. online teaching on students’ foreign-language enjoyment, with the aim of illustrating the utility of the vignette study (Section “Example vignette study: FL enjoyment in onsite vs. online teaching”).

The vignette study in foreign-language research

In a vignette study, a vignette is “a short description of a hypothetical incident, event or situation that is presented to informants in order to elicit their views, opinions and reactions” (Maguire et al., 2015, p. 244). The term vignette is thus synonymous to a short scenario, brief account, episode, or narrative. In L2 research, vignettes usually contain hypothetical scenarios from the foreign-language classroom or the context of foreign-language teacher education. The following three examples illustrate vignettes as they are typically used in L2 education:

Student: She kiss him.

Teacher: You need past tense here.

Student: She kissed him. Then they went home.

(Our vignette example)

The teacher assigns an essay writing task in class and allows 60 minutes for completion of the task. After a couple of minutes, you notice that your classmates have already started writing while you still work on the outline of your essay.

(Vignette from Bielak & Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2020, p. 6)

There is a student in your class. Just like you he is learning Spanish. You are sitting close to each other in a Spanish lesson and you are working with a text that you have been asked to read. Suddenly he sits up, sighs, and says: ‘This stuff we are doing now would have been so much easier in English. It is much more fun reading something in English.’

(Vignette from Henry, 2011, p. 243)

For a vignette study, a whole vignette set is required rather than a single vignette. This vignette set is deliberately constructed to contain one or more attributes (i.e., independent variables) which appear in the vignettes in their different variants (i.e., values of the independent variables). The whole vignette set contains the vignettes that represent all combinations of these attributes, so that each combination appears in one vignette (Atzmüller & Steiner, 2010, pp. 128–129).Footnote 2

Importantly, the meaning of vignette in a vignette study is different from a vignette as used in L2 teacher training at university. These training vignettes are short L2 lesson accounts that showcase a ‘problematic’ or ‘successful’ teaching situation. These accounts are then discussed in class to improve the trainees’ understanding of useful teacher actions, practices, or strategies (cf. Friesen et al., 2020). However, this valuable approach for teacher training is distinct from the technical use of a vignette in a vignette study. In a vignette study, a vignette should contain little extra information other than what is contained in its attributes. By doing so, the study participants will pay close attention to the attribute information, which will later inform their responses.

To illustrate a vignette study, consider the following vignette set, which consists of three vignettes. The vignette set contains only one attribute, i.e., ‘feedback type’, and its three variants ‘explicit feedback’, ‘recast feedback’, and ‘prompt feedback’ (cf. Lyster, 2018 for different types of L2 feedback). In the vignette set, the vignettes differ in how they ‘fill in’ the attribute of feedback, which should lead to different reactions from the participants. In the example, the different variants are in bold print. This would not be done in an actual study to avoid drawing attention to the study’s purpose.

Student: She kiss him.

Teacher: It’s ‘She kissed him.’

Student: She kissed him. Then they went home.

(explicit feedback)

Student: She kiss him.

Teacher: Ah, she kissed him. How intriguing.

Student: She kissed him. Then they went home.

(recast feedback)

Student: She kiss him.

Teacher: You need past tense here.

Student: She kissed him. Then they went home.

(prompt feedback)

The size of a vignette set depends on the number of attributes (i.e., independent variables) and variants (i.e., variable values) that are part of the study’s research question. Since there is one vignette for each combination, the vignette set size is calculated by multiplying the variants of each attribute. For instance, for a vignette study with two attributes (e.g., ‘feedback type’; ‘praise type’) with three and two variants respectively (e.g., ‘explicit’, ‘recast’, ‘prompt’; ‘praise’, ‘no praise’), the vignette set would consist of 3 × 2 = 6 vignettes. If an attribute was added, e.g., ‘teacher gender’, with ‘male’, ‘female’, and ‘not specified’, the vignette set would consist of 3 × 2 × 3 = 18 vignettes. The vignette set size is particularly important if all vignettes are to be presented in one study session. Consider the below example for a vignette with two attributes, i.e., ‘feedback type’ and ‘praise type’.

Student: She kiss him.

Teacher: It’s ‘She kissed him.’

Student: She kissed him. Then they went home.

Teacher: Okay, well done.

(explicit + praise)

In the study, participants (i.e., L2 learners, L2 teachers) are asked to respond by reporting their attitudes, decisions, or reactions (i.e., dependent variables) with regard to the vignette scenarios. This can be done through a quantitative assessment, e.g., Likert items, or qualitative assessment, e.g., open-ended interview questions. Since the variants were systematically varied, the vignette study is able to determine the causal effect of each variant on the participants’ self-reported attitudes, decisions, or reactions. In the example on feedback type, students could report if they would have learnt the correct form (“I would have remembered the correct form”), and if they would have liked to talk more in class (“I would have wanted to go on talking”) on a Likert scale (e.g., “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “agree”, “strongly agree”). Or else, students could give qualitative answers in an open-ended interview (“How do you assess your learning and motivation in this situation?”).

Earlier vignette studies in foreign-language research

In the past, very few investigations in L2 research have used a vignette design (for studies, cf. Shively & Cohen, 2008; Henry, 2011; Hernández, 2018; Bielak & Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2020; Chaudri et al., 2023). Henry (2011), for instance, examined motivation in high-school students who studied English as L2 and French, Spanish, or Russian as L3. He explored how their L2 English study affected their motivation to learn an L3. To do so, students were shown a vignette that described a frustrated classmate in the L3 classroom (cf. the example above; Henry, 2011, p. 243). Then, they were asked to comment on the vignette. The qualitative data showed that a comparison of L2 English to the L3 had a “negative impact on [their] L3 motivation” (p. 253). Since the study used a single vignette only and did not vary any attributes, it did not employ a fully-fledged vignette design. However, the collection of student responses based on a hypothetical classroom scenario is central to the design of the vignette study.

In another study, Hernández (2018) examined the development of apologies in L2 Spanish with L1-English college students during a four-week exchange in Madrid. Before and after their stay, participants were presented with five vignettes that described situations that required an apology (e.g., for being late). These scenarios contained the attributes ‘social status’ (low/mid/high), ‘social distance’ (low/high), and ‘seriousness of offense’ (low/high). The students’ written apologies were rated by two native speakers. The study showed that L2 learners made significant gains in their apology appropriacy, although they continued to rely on routine expressions. While Hernández (2018) did use attributes with different variants, these variants were not systematically varied. Instead, the five vignettes only contained a subset of the possible variations—a complete vignette set would have had 12 vignettes—, which prevented the study from establishing direct causal effects for each variant.

In a recent study, Bielak and Mystkowska-Wiertelak (2020) examined emotion regulation in adult L2 English learners. The participants were presented with 9 vignettes that described stressful classroom scenarios, such as coming to class unprepared, getting a low test score, or being behind on an essay (cf. the example above; Bielak & Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2020, p. 6). The students were asked to indicate the emotions they would experience and the emotion regulation strategies they would apply. Again, the study was not a fully-fledged vignette study, because the vignette set did not vary any attributes. However, the vignettes in themselves were variants of a larger theme, i.e., stressful L2 situations. The investigation thus illustrates the study logic of collecting student responses to varied hypothetical scenarios, which is crucial to the vignette design.

Henry (2011), Hernández (2018), and Bielak and Mystkowska-Wiertelak (2020) were described in greater detail because they illustrate the current use of the vignette study in L2 education well. In Table 1, earlier vignette studies in L2 research are summarized, that is, their main research question, vignette study design, and key findings. As Table 1 shows, none of the earlier studies used a fully-fledged vignette design, so that there were either no attribute variants (Henry, 2011; Bielak & Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2020; Chaudri et al., 2023), or attribute variants were used, but not varied systematically (Shively & Cohen, 2008; Hernández, 2018). Thus, none of the previous studies has used a complete vignette study design as described in “The vignette study in foreign language research”. This implies that earlier research has not always made use of the full potential of the vignette study.

Benefits and drawbacks for foreign-language research

Visibly, the vignette study has rarely been used in L2 research, and, if employed, has not been used with a fully-fledged study design. However, despite this paucity, the vignette study offers a number of benefits for research on L2 education (Auspurg & Hinz, 2015, pp. 9–13; Steiner et al., 2016, pp. 53–54). Firstly, the vignette study can flexibly be used with different research questions, since it can easily be adapted to different research topics in L2 teaching and learning. As researchers have full control over the vignette set, they can examine any set of variables (i.e., IV/IVs) and participants’ attitudes, decisions, or reactions (i.e., DV/DVs) to these variables. In principle, the vignette study is not restricted to any particular framework within SLA or L2 education (e.g., cognitive, affective, sociocultural, interactionist). Instead, like quasi-/experiments, the vignette study is a ‘theory-neutral’ research method that may investigate a wide range of research questions in different SLA or L2 frameworks.

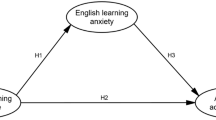

Moreover, the vignette study is able to analyse the effects of multiple independent variables on multiple dependent variables in a single study. It can thus contain several IVs (e.g., ‘feedback type’, ‘teacher praise’, ‘teacher gender’) and several DVs (e.g., ‘L2 uptake’, ‘motivation’) in a single study. The causal effect of each IV is identified by comparing all vignettes that contain a variant (e.g., ‘explicit’) to all vignettes that contain a different variant (e.g., ‘recast’ or ‘prompt’). If the vignette set is complete, the effect of the other IVs (e.g., ‘praise’, ‘gender’) on the DVs cancels out as they are equally distributed across all compared vignettes. To measure multiple DVs, the vignette study can include several Likert scales or open-ended questions that assess different learner attitudes or reactions.

Vignette studies are compatible with both quantitative and qualitative assessments and subsequent data analysis. If the DV is quantitative (e.g., Likert scales), the values for the IVs can be compared descriptively (i.e., study sample) or inferential analyses can be conducted to examine a generalization of the results (i.e., a population). Depending on the number of IVs and DVs, the inferential testing may involve either a simple analysis, such as a t-test, or more elaborate analyses, such as ANOVA or multiple regression, to examine the effects of several IVs on several DVs, including possible interactions (cf. Atzmüller & Steiner, 2010; Auspurg & Hinz, 2015 for the statistical analysis of multi-variate vignette studies). If the DV is measured qualitatively, thematic or content analysis can be used on the qualitative data to explore recurrent patterns in participants’ attitudes, decisions, and reactions. This qualitative data analysis should yield in-depth insights into the participants’ thoughts, beliefs, reasons, etc. as they closely engage with the vignette scenarios.

Moreover, vignette studies are suitable for exploring sensitive research topics, as participants respond to imagined scenarios that they are not actually experiencing. The vignette removes students from having to live through the described situations, which—when dealing with sensitive topics—reduces discomfort (e.g., foreign-language anxiety) or embarrassment (e.g., teacher bias, discrimination, intercultural misunderstandings). In particular, if a stand-in student is used in the vignette (e.g., “Maria is studying Spanish at university”), participants can project their responses onto the character (e.g., “How do you think Maria feels?”), which may additionally take away from their sense of exposure.

Lastly, the vignette study has a high cost-efficiency, since it is less time- and resource-heavy than conducting a classroom (quasi-)experiment on the same causal relationships. Also, if the earlier literature is already known, preparing a vignette study is straightforward, since the attributes, their variants, and the potential effects can be gleaned from the existing research. In practical terms, conducting a quantitative vignette study requires students to complete 2-3 sheets of paper, which can comfortably be done in a regular lesson.

At the same time, although the vignette study offers many benefits, it suffers from a major limitation frequently discussed in the method literature (Hughes, 1998, pp. 382–387; Auspurg & Hinz, 2015, pp. 113–118). Vignettes contain hypothetical scenarios to which participants respond with hypothetical attitudes, decisions, or reactions. Hence, participants are not situated in real-life situations and are “detached from the [vignette] situation” (Hughes, 1998, p. 83). As a result, they are missing cues that exist in real life (e.g., the teacher’s face) and their actions lack real-life consequences (e.g., the teacher will not grade them). The question thus arises if “responses to situations presented in the form of vignettes” truly correspond to “responses people have to [equivalent] real life situations” (Hughes, 1998, p. 83). This threat of a discrepancy between how students respond to vignettes and how they would behave in a real L2 classroom evidently limits the external validity of the vignette study. The same is true for the nature of the causal relationship between the IVs and DVs, which has also, in a manner of speaking, been imagined by the participants. It is therefore also not guaranteed that the same causal effects would occur in a real classroom in which the same IVs were present. As a result, L2 researchers need to be cautious about directly transferring vignette study results to real-world learners and classrooms.

An answer to this concern is to treat vignette study results as preliminary evidence and to subsequently conduct a follow-up experiment on the same relationships in an actual classroom. The experiment would then actually ‘teach’ or ‘stage’ the IVs and collect students’ real responses or skills as DVs, which would result in a higher external validity, since the study design is closer to the real classroom. However, a similar limitation is true for experiments as well. Here, students also know that their behaviour, effort, and results do not have real-life consequences, since the lesson is not ‘taught’ by their actual teacher, which raises a similar concern about external validity. Still, if the experiment yielded the same results as the vignette study, while being actual and not hypothetical, this outcome would strengthen, if not override, the earlier vignette study findings.

As another possibility, vignette study results could be triangulated with behavioural, non-experimental data from real life. Such behavioural data can be gathered from field studies that examine the same IVs and DVs in natural, authentic settings. As with an experiment, if the field data were to produce similar results, while being ‘live’ rather than hypothetical, this would provide support for the vignette study findings. In one such study, Hainmueller et al. (2015), for instance, compared participants’ responses in a vignette study to their actual voting behaviour on the naturalization of Swiss immigrants, and found a high degree of correspondence between their hypothetical and real-world decisions. However, for L2 education, it is harder to imagine equivalent real-world data, since behavioural variables in classroom recordings are difficult to quantify, while learners’ attitudes and decisions usually cannot be observed from the outside.

As a further limitation, the vignette study may suffer from a social desirability bias, with participants providing answers that they believe are socially acceptable, but which do not necessarily reflect their genuine views or likely behaviours. This risk is particularly present in research topics with strong normative expectations, such as intercultural learning, inclusivity, or the student-teacher hierarchy. For instance, in a vignette in which a teacher makes an insensitive remark about a classmate, students may overstate their willingness to challenge the teacher (which, due to the student-teacher hierarchy, they would not do in the actual classroom). As a result, students may report ‘ideal’ responses, which may not match their real attitude or classroom behaviour. To mitigate this issue, L2 researchers should stress the vignette study’s anonymity and encourage students to give answers that truly reflect how they would have felt or behaved.

After introducing the vignette study, its benefits and limitations, an exemplary vignette study will be presented in the article’s final section. The purpose of this vignette study is to exemplify the design, realization, and analysis of a vignette study, and to serve as model for researchers wishing to conduct their own studies. As a result, the example vignette study will be reported in a condensed format to keep the focus of the discussion on the design of the vignette study.

Example vignette study: FL enjoyment in onsite vs. online teaching

In L2 education, teachers and learners resort to online (or: remote) teaching as an alternative to the regular onsite (or: in-person) classroom due to a variety of reasons, such as flexibility, simpler reach of students, or, as evidenced most recently, health concerns. However, while there are obvious benefits of online classes, there are also various costs related to remote teaching (cf. Resnik & Dewaele 2023 for the benefits and drawbacks of online L2 teaching). Arguably, the students’ learning outcomes, e.g., their L2 development, as well as several affective factors, e.g., their enjoyment, motivation, or anxiety, may suffer from an online teaching setting. Among these affective factors, the example vignette study will focus on foreign-language enjoyment (FLE), which refers to the positive emotional experience that students have while studying a foreign language.

Up to now, little empirical research has been conducted on the effect of onsite vs. online teaching on the students’ foreign-language enjoyment. Also, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no earlier studies on students at the secondary school level (which arguably make up the majority of L2 learners). As a brief overview, the current research state can be summarized as follows: Wang, Zhan, and Liu (2022) examined student satisfaction with online teaching, which is comparable to FLE, in 118 US college students who studied L2 Chinese. The students stated that they would prefer in-person classes in the future, owing to their unsatisfying experience with online learning. This suggests that student enjoyment was lowered in the remote learning setting. Dewaele, Albakistani, and Ahmed (2024), using a web-based questionnaire, examined 168 Arab and Kurdish L2 English learners, out of which 152 were studying at university. Students rated their FLE for both earlier onsite (retrospective) and remote classes (current). The study showed that students experienced less FLE in online as opposed to onsite classes. Resnik and Dewaele (2023), again using a web-based questionnaire, asked 510 university-level L2 English students to rate their FLE for in-person (retrospective) and online (current) classes. Again, the study showed that student FLE was significantly lower in the online setting than in the onsite classes. Finally, Resnik, Dewaele, and Knechtelsdorfer (2023), in another web-based survey, examined FLE in 437 university L2 English students and asked about their previous onsite and current online classes. The study also showed a significant drop in learner FLE in remote as opposed to in-person teaching.

In summary, the current state of research, in a strikingly uniform fashion, attests that the effect of onsite vs. online teaching on the students’ FLE is negative, i.e., that FLE was lowered in all university-level student samples in remote teaching. However, none of the earlier studies investigated a sample of secondary-school students. Our example study intends to address this gap in the current research.

Research question

In our vignette study, the following research question was addressed: “How does onsite vs. online teaching in the L2 English classroom influence secondary-school students’ foreign-language enjoyment?” With regard to the current research state, we predicted that the students’ enjoyment would be lowered in the online vs. onsite setting.

Study sample

The study was conducted in October 2021, at the beginning of the 2021/22 school year, when schools in Germany had fully reopened after the Covid-19 pandemic. During Covid, Germany had employed nationwide school closures as part of its broader lockdown strategy. Throughout 2020 and 2021, schools alternated between onsite and online teaching depending on regional infection rates. Finally, schools fully returned to in-person learning in the 2021/22 school year, with safety measures such as masks and testing still in place. As a result, in October 2021, secondary-school students at all grade levels had gather comprehensive experience with both online and onsite teaching over an extended period of time.

The study sample consisted of five complete L2 English classes at a German secondary school in Göttingen, Germany, i.e., one class from grade 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, with a total of N = 126 students. The basic demographic information of the participants is shown in Table 2. The data used in this study was collected under the general waiver of individual student consent if the purpose of the study is quality development in schools, as stipulated by the German state of Lower Saxony (see Consent to Participate below).

Study instrument

The study instrument was a two-page questionnaire, which contained the vignette (onsite/online) and all remaining study measurements. At the top, the questionnaire had the demographic questions (i.e., age, gender, grade), which were followed by the study vignette in either the onsite (A) or online (B) variant. The vignette was framed by a black box, but did not have a title or any other information. Each questionnaire had only one version of the vignette, either the onsite or online version. To assign students randomly, we used a random number generator (https://www.random.org) to create a sequence of 0s and 1s (0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, etc.). We then matched the sequence to the students based on the alphabetical order of their last names in each class, assigning vignette A to students with a 0 and vignette B to students with a 1. A visual inspection of age, gender, and grade distributions in vignette A and B did not indicate any inadvertent bias, so that we did not conduct follow-up testing (vignette A: M age = 11.95; female = 30, male = 34; grade 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 = 13, 13, 13, 14, 10; vignette B: M age = 12.13; female = 29, male = 31, other = 2; grade 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 = 11, 15, 12, 12, 12). The vignettes were written in German, a language that all students were native speakers of or fully fluent in. (The vignettes are presented in English below). In the vignettes, the students were asked to put themselves into a hypothetical classroom setting (onsite/online), which they were familiar with from the alternating teaching scenarios during Covid.

Study Vignette: Onsite Teaching (A)

Please picture yourself in an ordinary English lesson at school before the summer break. Imagine that you are in the classroom right now. Look around you: What do your surroundings look like? How are you feeling right now? What mood are you in? With these ideas in mind, answer the following questions as if you were in an ordinary English lesson at school.

Study Vignette: Online Teaching (B)

Picture yourself in an online English lesson at home before the summer break. Imagine that you are in the online lesson right now. Look around you: What do your surroundings look like? How are you feeling right now? What mood are you in? With these ideas in mind, answer the following questions as if you were in an online English lesson at home.

After the vignette (onsite/online), the questionnaire showed a 10-item FLE scale, whose items had been taken from the foreign language enjoyment scale in Dewaele and MacIntyre (2016). The original FLE scale in Dewaele and MacIntyre (2016) contained 21 items, from which we selected 10 items that most closely matched the student experience in a German EFL class. To do so, we also changed the original wording “FL” (foreign language) to “English” in two items, to make these items fit into the EFL context. The students’ responses were collected using a 4-point Likert scale, which ranged from “strongly disagree” [1] to “strongly agree” [4]. With Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.77, the 10-item FLE scale exhibited a good reliability (Dörnyei, 2010). The items and Likert scale were presented in German. Table 3 shows the original items (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2016), in English, and our items, in German. We validated the translation by asking an uninvolved researcher, who was unfamiliar with the original scale, to back-translate the German items into English. A third uninvolved researcher, who was a native English speaker, then compared the back-translation with the original items and found no discrepancies (with the exception of changing “FL” to “English”).

Study procedure

In each class, the two-page questionnaire was handed out to the whole class at the beginning of a regular EFL lesson. In all classes, all students participated in the study, so there was no missing data on the student level. The randomization resulted in 64 onsite vignettes and 62 online vignettes, which added up to 126 participants. The students were told to read the instructions and vignette carefully and to tick the Likert options as they thought they applied to them. We also emphasized that the study was anonymous and that its results would not be shared with the teacher. Despite our instructions, some students put their ticks in between the Likert options for some items on their questionnaire. Since we were unable to assign a true value to these in-between-ticks, we counted them as missing values on the item level. The FLE scale for those students was therefore calculated from the remaining items. A time limit of 10 minutes was set for the questionnaire, but no student took the whole time to complete it.

Study results and discussion

To answer our research question, i.e., “How does onsite vs. online teaching in the L2 English classroom influence secondary-school students’ foreign-language enjoyment?”, we averaged the items to obtain the value for FLE as a construct. The descriptive results for FLE for the sample, the onsite, and online vignette are shown in Table 4.

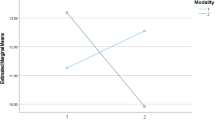

As each student had completed one questionnaire only, we conducted a t-test for independent samples, with the vignette (onsite/online) as IV and student FLE as DV. Since three earlier studies had found a significant difference between onsite and online teaching, with FLE being lower online (Resnik & Dewaele, 2023; Resnik et al., 2023; Dewaele et al., 2024), and a fourth study gave the same indication qualitatively (Wang et al., 2022), we also predicted online teaching to lower FLE in our study. Thus, we used a one-tailed (i.e., with directional hypothesis) rather than two-tailed (i.e., without directional hypothesis) t-test. The one-tailed t-test showed no significant difference [t(120) = 1.3673, p = 0.087; Cohen’s d = 0.25] between the onsite vignette (M = 3.15, SD = 0.39, n = 64) and online vignette (M = 3.05, SD = 0.46, n = 62). (For comparison, a two-tailed t-test, without a directional hypothesis, showed the following non-significant result: t(120) = 1.3673, p = 0.174; 95% CI [−0.05, 0.25]; Cohen’s d = 0.25). Hence, we could not reject the null hypothesis that onsite vs. online teaching had no effect on FLE in a population of secondary-school students. However, the descriptive results showed that remote teaching displayed a slightly lower FLE, with a small effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.25 (Oswald & Plonsky, 2010). Our study results are therefore not conclusive. While the descriptive results indicate that student FLE was lower in online vs. offline teaching, the inferential results do not allow for a generalization of this effect beyond the study sample. We can answer our research question (“How does onsite vs. online teaching in the L2 English classroom influence secondary-school students’ foreign-language enjoyment?”) by stating that the study did not yield conclusive evidence for an effect of onsite vs. online teaching on students’ FLE at secondary school. The descriptive findings, however, which refer to the study sample only, are potentially in line with earlier research, which rather uniformly showed that the effect of online vs. onsite teaching on student FLE was negative, and that FLE was lowered in all earlier university student samples (Wang et al., 2022; Resnik & Dewaele, 2023; Resnik et al., 2023; Dewaele et al., 2024).

Finally, as a limitation to our study, the students’ responses may have been influenced by social desirability. Students, after having returned to the desirable ‘normality’ of lessons at school, may have reported their enjoyment of onsite classes in line with what they perceived as the socially accepted view. Conversely, they may have downplayed the enjoyment they experienced in online lessons, even if, at the time, they had felt very comfortable with online teaching. Therefore, social desirability bias may have inflated the difference between onsite vs. online teaching in our study. At last, another limitation of the study was that it was conducted in a secondary school in Germany with students aged 9 to 14. Thus, even if the results had been statistically significant, the specific cultural context and developmental stage of the students would have limited their generalizability to a comparable population, i.e., a similar age group and school setting.

Conclusion: the vignette study as valuable study method for L2 research

Ideally, our example study was able to illustrate the various benefits of the vignette study for L2 research. To conclude, we will briefly link up the benefits discussed above and our vignette study. Firstly, as for flexible research questions, the example study as well as the vignette studies overview show that the vignette design can be adapted to a variety of research topics. In the example study, we examined a question that was previously examined in web surveys only, and it was not difficult to plan a vignette study with the same research question. Secondly, as for cost-efficiency, the design and conducting of our study was very economical, while it still used full randomization and was able to examine causal effects. (To be precise, while our study did not obtain significant results that showed a causal effect for our research question, the vignette study does allow for causal inference in principle). In fact, we only visited five classes, gave out and collected a two-page questionnaire, which was a great value for the obtained results. Thirdly, the example study would have been able to analyse the effects of several IVs on multiple DVs, although this was not pursued in our study. However, we could have had added more IVs, such as ‘learning activity’ or ‘social form’, and more DVs, such as ‘language outcome’ or ‘engagement’. Fourthly, while the example study used a quantitative assessment of the DV, we could have assessed the students’ FLE via qualitative questions (e.g., “How did you feel in the [onsite/online] classroom? Were there moments that felt particularly enjoyable or satisfying?”). This shows the possibility of using both quantitative and qualitative measurements in a vignette study. Fifthly, while our vignette study did not address a sensitive topic, an identical study design could be used to examine the more sensitive question of foreign-language anxiety (FLA). In this case, instead of an FLE scale, an FLA scale would be placed after the vignette (with items such as “I get nervous when I am speaking in class”).

It was the purpose of this article to introduce and illustrate the utility of the vignette study for research in L2 teaching and learning. Hopefully, the discussion and example study were able to make a case for the future use of this powerful, yet underused method to examine causal relationships in L2 education. For L2 researchers interested in conducting a vignette study, please refer to the guidelines in the Appendix, which are based on this article and example study.

Data availability

A dataset was used for the study in the article, which can be downloaded via the Supplementary Materials.

Notes

That is, at the time of publication and to be best of the author’s knowledge. We are unaware of the reasons for the underuse of vignette studies in L2 research, but assume that both disciplinary preferences for quasi-/experiments, which closely resemble actual teaching, and methodological unfamiliarity, with the vignette study being absent from all major research method handbooks, play a major role.

References

Atzmüller C, Steiner PM (2010) Experimental vignette studies in survey research. Methodology 6(3):128–138. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000014

Auspurg K, Hinz T (2015) Factorial survey experiments. Quantitative applications in the social sciences: Vol. 175. Sage

Bielak J, Mystkowska-Wiertelak A (2020) Investigating language learners’ emotion-regulation strategies with the help of the vignette methodology. System 90(3):102208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102208

Chaudri AI, Pervaiz A, Ali RA (2023) A descriptive analysis of emotion regulation in the ESL classroom of university students: a vignette study. Int J Linguist Cult 4(1):83–108

Dewael, J-M, MacIntyre P (2016) Foreign language enjoyment and foreign language classroom anxiety: The right and left feet of the language learner. In P MacIntyre, T Gregersen & S Mercer (Eds), Positive Psychology in SLA (pp 215–236) Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783095360-010

Dewaele J-M, Albakistani A, Ahmed IK (2024) Levels of foreign language enjoyment, anxiety and boredom in emergency remote teaching and in in-person classes. Lang Learn J 52(1):117–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2022.2110607

Dörnyei Z (2010) Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing (2nd ed.). Routledge

Friesen ME, Benz J, Billion-Kramer T, Heuer C, Lohse-Bossenz H, Resch M, Rutsch J (2020) Vignettenbasiertes Lernen in der Lehrerbildung: Fachdidaktische und pädagogische Perspektiven. Beltz

Hainmueller J, Hangartner D, Yamamoto T (2015) Validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. PNAS 112(8):2395–2400. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1416587112

Harris J, Leeming P (2022) The impact of teaching approach on growth in L2 proficiency and self-efficacy: A longitudinal classroom-based study of TBLT and PPP. J Second Lang Stud 5(1):114–143. https://doi.org/10.1075/jsls.20014.har

Henry A (2011) Examining the impact of L2 English on L3 selves: a case study. Int J Multiling 8(3):235–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2011.554983

Hernández T (2018) L2 Spanish apologies development during short-term study abroad. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach 8(3):599–620. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.3.4

Hughes R (1998) Considering the vignette technique and its application to a study of drug injecting and HIV risk and safer behaviour. Sociol Health Illn 20(3):381–400

Jordan G (2004) Theory construction in second language acquisition. Language learning and language teaching: Vol. 8. Benjamins

Lowie WM, Verspoor MH (2019) Individual differences and the ergodicity problem. Lang Learn 69(S1):184–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12324

Lyster R (2018) Roles for corrective feedback in second language instruction. In C.A. Chapelle (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (pp. 1–6). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal1028.pub2

Mackey A, Gass SM (2016) Second language research: Methodology and design (2nd ed.). Routledge

Maguire N, Beyens K, Boone M, Laurinavicius A, Persson A (2015) Using vignette methodology to research the process of breach comparatively. Eur J Probat 7(3):241–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/2066220315617271

Oswald FL, Plonsky L (2010) Meta-analysis in second language research: Choices and challenges. Annu Rev Appl Linguist 30:85–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190510000115

Resnik P, Dewaele J-M (2023) Learner emotions, autonomy and trait emotional intelligence in ‘in-person’ versus emergency remote English foreign language teaching in Europe. Appl Linguist Rev 14(3):473–501. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2020-0096

Resnik P, Dewaele JM, Knechtelsdorfer E (2023) How teaching modality affects foreign language enjoyment: A comparison of in-person and online English as a foreign language classes. Int Review of Appl Linguistics Language Teach. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2023-0076

Sauer C, Auspurg K, Hinz T, Liebig S, Schupp J (2014) Method effects in factorial surveys: An analysis of respondents’ comments, interviewers’ assessments, and response behavior. SSRN Electron J 629:1–29. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2399404

Shively RL, Cohen AD (2008) Development of Spanish requests and apologies during study abroad. Íkala, Rev De Leng Y Cult 13(2):57–118. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.2683

Steiner P, Atzmüller C, Su D (2016) Designing valid and reliable vignette experiments for survey research: a case study on the fair gender income gap. J Methods Meas Soc Sci 7(2):52–94. https://doi.org/10.2458/v7i2.20321

Wang Y, Zhan H, Liu S (2022) A comparative study of perceptions and experiences of online Chinese language learners in China and the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. J China Comput Assisted Language Learn, 2(1), 69–99. https://doi.org/10.1515/jccall-2022-0009

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for this study.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AW is the only author: He conducted and analyzed the study reported in the article, wrote and revised the entire manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Georg-August-Universität Göttingen (Approval No.: 22410). Approval was granted on 01.05.2021. All procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

The data used in this study was collected under the general waiver of individual student consent if the purpose of the study is quality development in schools (Qualitätsentwicklung in Schule), as stipulated by the German state of Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen). Source: Surveys and Data Collection in Schools (Umfragen und Erhebungen in Schulen), Abbreviation: SchUmfRdErl,NI, Legal Type: Administrative Regulation (Verwaltungsvorschrift), Issuing Authority: Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen), Classification Number: 22410, §4.d, Date: 01.01.2022.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wirag, A. The vignette study: examining the effects of multiple variables in foreign-language teaching and learning. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 139 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06444-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06444-w