Abstract

Many people enjoy listening to live music. But what exactly does a live context contribute to people’s experience, and do different types of concerts influence the musical experience in different ways? In this study, we focus on the Western classical concert, which has been claimed to be in an existential crisis. One way in which practitioners are seeking to counter this crisis is by adapting the concert format. Our study was inspired by such artistic endeavors and conducted live concert experiments in an ecologically valid setting to explore the effects of the concert format on the audience’s aesthetic experience. Eleven chamber music concerts were organized, all of which presented the same three string quintets but differed regarding several format components. To represent the aesthetic experience of the audience (N = 802) in an exhaustive way, self-report data, physiological responses, as well as camera recordings of facial expressions were collected. The analyses revealed that each concert format variant had a unique effect on the audience. Variants that differed the most from the standard format had the strongest influence on the audience’s experience, while also one concert that represented an ideal realization of the standard format, led to particularly positive experiences. Aesthetic emotions and heart rate were particularly susceptible to format changes, whereas appreciation of the music and the musical performance were not affected by the concert format. We found that (1) a high-quality concert venue can afford a more immersed experience and a higher appreciation of the concert as a whole; (2) explanations of the meaning of the pieces in a relatable, personal way during the concert help people connect emotionally with the pieces and increase tolerance towards contemporary pieces; (3) an intense musical experience and a satisfying social experience may compete with each other. Our results do not only broaden our scientific understanding of how contexts contribute to aesthetic experiences, but can also be of use for concert practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Live performances likely go back all the way to the origins of music. If anyone wanted to listen to music, they either had to play it themselves or go to a place where others were performing. Based on the co-presence of performers and listeners, the music cultures across the globe have developed a large variety of participatory and presentational performance types (Turino, 2008). In the West, presentational live performances of music whose main purpose it is to allow for a focused and undisturbed musical experience are called concerts. Concerts started to emerge in Europe in the 18th century and developed along with a repertoire of musical works from Joseph Haydn to Gustav Mahler usually praised as the pinnacle of Western art music (Schwab, 1971; Weber, 1975; Johnson, 1995; Schleuning, 2000; Weber, 2008; Thorau and Ziemer, 2019). In the 20th century, further concert types emerged together with the novel forms of Afroamerican and other popular music genres. However, the necessity for co-presence and live performances had already ended with the invention of music recording, broadcasting and playback technologies around 1900 (Burgess, 2014). More and more, people could listen to any music they wanted, anytime and anywhere which led some observers to predict the concert’s imminent doom (Besseler, 1926).

Today, the concert is still very much alive, although its future is the topic of an ongoing debate (Mazierska, Gillon and Rogg, 2020). But while popular concerts are thriving, the classical concert has been the subject of a discourse of crisis and decline since the 1990s (Bugiel, 2015)–a crisis of potentially great cultural, institutional and economic impact, since classical music is tied to a dense system of public institutions from music conservatories to orchestras and concert halls. Typical symptoms of this crisis are seen in the shrinking and ageing of audiences which is interpreted as the failure of the classical concert to attract younger and more diverse listeners and thus secure its own future (Kolb, 2001; Kramer, 2007; Pitts, 2016). Several reasons have been discussed for this crisis in demand, one of them being the concert format and its etiquette which younger people and concert novices might neither understand nor feel comfortable with (North, Hargreaves and O’Neill, 2000; Noltze, 2010). While some institutions change their marketing strategies and music educators turn to potential future audiences to help them connect with classical music and its concert formats (Brown, 2004; Wimmer, 2010; Petri-Preiss and Voit, 2023), concert managers and musicians have long since begun to address this problem by artistically experimenting with unusual concert venues, programs, visual augmentation, participatory and co-creational elements, or a loosening of behavioral regimes (Brüstle, 2013; Uhde, 2021; Smith, Peters and Molina, 2024). This way, they seek to adapt the traditional concert format to the demands of contemporary listeners while preserving the particularly intense, rewarding, and meaningful musical and social experiences theoreticians ascribe to it (Heister, 1983; Small, 1998; Auslander, 1999; Simon, 2018) and audiences look for (Pitts, 2005; Packer and Ballantyne, 2011; Burland and Pitts, 2014; Baym, 2018).

From a scientific perspective, the idea that the concert format may positively or negatively influence how people experience music can be related to theories from the social sciences and (empirical) aesthetics. Specifically, sociologist Erving Goffman’s concept of the “frame” that affects how people interpret a culturally and socially determined situation and how they behave in it (Goffman, 1974) can be easily adapted to conceptualize the role of the concert for music listeners (Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2021). And although (empirical) aesthetics has for a long time focussed almost exclusively on properties of an aesthetic stimulus and characteristics of the recipient to explain aesthetic judgments and experiences, more recently, philosophers of art (most notably, Danto, 1964; Becker, 1982 with their concept of “art worlds”) as well as empirical researchers such as Helmut Leder et al. (2004; Leder and Nadal, 2014), David Hargreaves (2012, “reciprocal feedback model”) or Scherer and Zentner (2001) have included the context in which an aesthetic episode takes places into their theoretical models.

In addition to theoretical conceptualizations, researchers have also started to study music listening in (classical) concerts empirically and experimentally (Tröndle, 2018; Tröndle, 2021). Groundbreaking work was done using qualitative methods such as interviews and participant observation that identified why people go to (classical) concerts and what they usually experience there (Pitts, 2005; Burland and Pitts, 2014). Quantitative methods such as questionnaires and physiological measurements have been used to assess appreciation, expectation, emotion, feelings of connectedness, and physiological arousal (Thompson, 2006; Egermann et al., 2013; Merrill et al., 2023; O’Neill and Egermann, 2022) and have found physiological synchronization of concert audiences (Tschacher et al., 2023a; Tschacher et al., 2023b), in particular in response to specific musical characteristics (Czepiel et al., 2021). Still rare, however, are studies that seek to compare the effects of different concert components and formats in a controlled experimental approach. The earliest strand of this still relied on audiovisual recordings and is composed of studies that explore the respective contributions of the visual and the audio component (Vines et al., 2006; Chapados and Levitin, 2008; Vines et al., 2011 (all three articles were based on the same data); Behne and Wöllner, 2011; Tsay, 2012; Coutinho and Scherer, 2017; Griffiths et al., 2018; Lange et al., 2022). Overall, being able to see and not only hear the musicians had significant positive effects, e.g., on audience’s emotional responses (Vines et al., 2006; Vines et al., 2011; Coutinho and Scherer, 2017), electrodermal activity as a measure of engagement (Chapados and Levitin, 2008), perception of musical structure (Vines et al., 2006), ratings of performance quality (Tsay, 2013; Griffiths et al., 2018), and perceived expressivity (Vines et al., 2011; Lange et al., 2022). In a meta-study, Platz and Kopiez (2012) calculated an average medium effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.051 for the visual component in music listening. A second strand of research addresses the specifics of liveness by comparing live performances with recordings (Shoda et al., 2016; Coutinho and Scherer, 2017; Swarbrick et al., 2019, Swarbrick et al., 2021; Swarbrick and Vuoskoski, 2023; Trost et al., 2024). Findings indicate an influence of a live experience on physiological arousal (Shoda et al., 2016), brain activity (Trost et al., 2024), as well as on felt emotions (Coutinho and Scherer, 2017), engagement (Swarbrick et al., 2019: faster head movements), and social connection (Swarbrick et al., 2021; Swarbrick and Vuoskoski, 2023). A third strand of research is characterized by the experimental manipulation of individual format features of audiovisual recordings or streams of live performances such as presence or absence of an audience (Shoda and Adachi, 2015), stereo vs. 3D sound (Shin et al., 2019), VR environments (Yakura and Goto, 2020; Onderdijk et al., 2021), pre-concert talk (Egermann and Reuben, 2020), or audience participation (Onderdijk et al., 2021; Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2023).

Overall, the existing body of experimental research provides neither comprehensive nor systematic understanding of which defining features of live concerts influence which experience dimensions, nor of the underlying mechanisms involved. The samples are typically very small (Ns from 20 to 83, only four studies are based on samples of more than 100 participants: Shoda and Adachi, 2015 (N = 153); Swarbrick et al., 2021 (N = 317), Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2023 (N = 525), Swarbrick and Vuoskoski, 2023 (N = 107)) and the vast majority of manipulations target recordings, not the live concert itself. To measure experience, mostly self-reports are collected, and only very rarely also physiological responses (e.g., Egermann and Reuben, 2020; Trost et al., 2024), facial expressions (Kayser et al., 2022) or body movement (e.g., Swarbrick and Vuoskoski, 2023).

In line with the increasing interest in ecologically valid studies also in the field of music psychology (Tervaniemi, 2023), our team developed a conceptual framework for concert studies that takes the concert as the stimulus of interest that needs to be systematically varied in order to establish how its various features interact with each other, with the music, and with characteristics of the audience members in creating musical experiences (Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2021). Based on this framework, we started “Experimental Concert Research”, an extensive research project that developed around several series of experimental live and streamed concerts and in which the same three string quintets by L. van Beethoven, B. Dean, and J. Brahms were played. The main concert series is the topic of this paper and comprised of eleven live concerts in Berlin, Germany, that were visited by an audience of N = 802 in the spring of 2022. The experimental manipulations related to the main defining elements of the concert frame as identified in the theoretical literature (Heister, 1983; Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2021) and were designed by Folkert Uhde, who has been active as a concert designer for many years: spatial-architectural environment, ensemble characteristics, musical programming, social relationship between performers and audiences, visual component, acoustic component and additional information on the musical pieces (more details are given below in the section “Stimuli”). For an overview of all concerts, see Table 1, for a schematic depiction of the study design, see Fig. 1.

Data that were collected during the three phases of each of the elven concert experiments (before the concert: self-reports via questionnaire, during the concert: physiological responses and facial actions, after the concert: self-reports via questionnaire). This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Copyright © Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, all rights reserved.

In this paper, we investigate the influence of these different concert components and formats on the audience’s experience (see also Tröndle et al., 2025). To measure the experience of the audience in a comprehensive way, we have based our approach on the component process model of emotion (Scherer, 2005) as was already done in an earlier study in music listening in concerts (Egermann and Reuben, 2020). Here, affective experiences are characterized as (1) cognitive appraisals of stimuli that lead to changes in (2) subjective experience, (3) physiological arousal, (4) expressive behavior, and (5) action tendencies. In our study we measured the first four emotion components with questionnaires that audience members had to complete after the concert (component 1 and 2), physiological responses recorded during the performance (component 3), as well as camera recordings of facial expressions (component 4). The latter type of data had previously only been used capturing audience reactions on simple dichotomous stimuli and had not yet been applied to the realistic listening context of a classical concert (Kayser et al., 2022). We did not focus on action tendencies, as the etiquette in classical concerts does not allow typical approach and avoidance behaviors.

The rudimentary and inconsistent state of research on the influence of situational and contextual factors on the experience of (live) music to date hardly allows a hypothesis-based approach. The following analyses are therefore rather explorative and oriented on the artistic experience and intentions that have guided the design of the individual concert formats.

Materials and methods

Stimuli

The concert was designed as a chamber music event and adhered to current programming conventions for such performances: three pieces in total consisting of two works from the classical and romantic periods and one contemporary piece, following a trajectory from shorter, introductory work to the main piece at the end. The contemporary piece was positioned between the two others. Specifically, the program comprised string quintets by Ludwig van Beethoven (op. 104 in C minor, first movement only), Brett Dean (“Epitaphs”), and Johannes Brahms (op. 111 in G major).

When creating the various concert formats that served as experimental stimuli, we drew upon the practical expertise of the project’s artistic director (Uhde, 2021), typical formatting variations found in contemporary classical concerts (Tröndle, 2021), as well as established theories of concert performance and liveness (e.g., Heister, 1983; Auslander, 1999; Simon, 2018; Sloboda and Ford, 2019; Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2021).

Several factors constrained artistic freedom due to practical, technical, and experimental requirements. Audiences had to be seated in fixed positions to accommodate the network installation, ensure consistent camera conditions, and minimize movement artifacts in physiological measurements. Each concert differed from previous ones in only one format component to isolate the effects of individual elements while maintaining ecological validity by approximating real concert experiences as closely as possible.

These considerations led to the selection of the following format components for experimental manipulation:

Concert Hall

The construction of dedicated concert halls dates back to the late 18th century (Forsyth, 1985; Beranek, 2003). Their primary function is to provide a space large enough to enable the spatio-temporal co-presence of musicians and audience that defines live performance, while offering optimal acoustics for musical expression. Contemporary communities continue to invest substantially in concert hall construction, addressing issues of acoustics, attractiveness, and inclusivity. Being frames in a quite litteral sense, from a psychological perspective, concert halls function as priming factors through their architectural aesthetics, semiotics, and the spatial relationship they establish between stage and auditorium (Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2021). But they also co-constitute the musical realization of the programmed works via their acoustics.

Our concerts took place in two venues with markedly different architectural, acoustic, and aesthetic characteristics. The Pierre Boulez Saal (opened in 2017, architect: Frank Gehry) features an elliptical design characterized by light wood tones and bold, contrasting colors in the upholstered seating. It is designed to facilitate focused, undistracted listening and foster intimate musical encounters. The Radialsystem, by contrast, is a late 19th-century industrial building that served as a pumping station until 1999. Following renovation that integrated modern glass, steel, and concrete elements with the original brick architecture, it has hosted diverse cultural events and transdisciplinary performances since its opening in 2006. The former machinery hall where our concerts took place features black-painted walls and floors with flexible, unupholstered seating.

Pierre Boulez Saal embodies traditional concert hall aesthetics emphasizing comfort, acoustic excellence, and a focussed listening experience, while Radialsystem represents a modern “industrial chic” aesthetic not primarily associated with classical music and potentially more appealing to younger audiences. This manipulation addressed questions of how aesthetic, acoustic, and comfort aspects of concert venues influence musical experience.

Musicians

Musician prestige and skill play crucial roles in the classical concert business and, alongside repertoire selection, significantly determine ticket sales. Audiences value exceptional technical abilities, individual interpretation, as well as stage presence and appearance. In chamber music, distinguished as an intricate ensemble art form, an important distinction exists between musicians who form an established, well-rehearsed ensemble versus those who collaborate only occasionally—what might be termed their ensemble formation.

Our concerts featured two different professional ensembles addressing aspects of prestige and collaborative cohesion. Ensemble 1 (Yubal) consisted of young musicians not yet internationally recognized but who had performed together as a chamber music ensemble for several years (low prestige, established formation). Ensemble 2 (Epitaph) comprised senior musicians and internationally acclaimed soloists, only some of whom had previously collaborated in chamber music settings (high prestige, ad hoc formation). We investigated potential prestige effects against the possibly more polished interpretation achievable by a dedicated chamber music ensemble.

Moderation

In traditional classical concerts, all musician-audience communication typically occurs through musical performance itself. Other concert genres, particularly popular music, incorporate more direct communication forms such as artist speeches or vocal interaction—elements that effectively realize the co-presence aspect central to live performance. Within classical music, performers have increasingly experimented with verbal elements as more personal means of music delivery, helping audiences understand programming and interpretation choices (addressing the impersonal versus personal dimension identified by Sloboda and Ford, 2019).

Building on this development, one concert featured a moderator who briefly introduced the topic of musical experience shared by audiences and musicians, then interviewed the musicians before the second and third works about their relationship to the pieces and their connection with the contemporary composer, who had previously performed his work with these musicians. This intervention targeted multiple experiential levels: (1) facilitating piece comprehension and programming understanding to increase emotional engagement, (2) making the contemporary work more accessible, (3) breaking the “fourth wall” between stage and auditorium characteristic of many performing arts, and (4) revealing musicians as personalities to foster personal audience-performer connections; effects that have been shown by previous research (Fischinger, Kaufmann, and Schlotz, 2020; Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2023). Overall, this approach emphasized concerts’ inherent nature as social events, particularly the dimension of musician-audience co-presence.

Visual dimension

Unlike recorded music, concerts constitute multisensory experiences with particular visual significance. Audiences observe musicians performing, experience specific lighting of stage and auditorium, and engage with the concert hall’s visual appeal. Media exposure has conditioned audiences to perceive audio-visual correspondences that enhance their experience.

We addressed this component through two approaches. From the seventh concert onward, constant stage lighting was replaced with scenarios matched to respective movement characters in color, brightness, and intensity. The intensification of the visual component primarily aimed to create more immersive, movement-specific experiences based on cross-domain mapping theories. In one concert, a large portrait-format screen positioned next to the ensemble displayed either close-ups of individual musicians filmed in real-time or, during movements of the contemporary piece, photographs and biographical information of the deceased individuals to whom movements were dedicated. This intervention sought to strengthen felt audience-musician co-presence, enhance immersion, and make the contemporary piece more approachable.

Programming

Concerts differ from many other music listening forms by presenting multiple pieces in specific sequences that may create reciprocal effects between works (Weber, 2001; Marín, 2018). Within relatively strict conventions, concert organizers invest considerable thought in sensitive, meaningful programming, sometimes reflected in concert titles. Our concert series adhered to programming conventions, while also including a novel work and elements of surprise (dimensions established versus new work and predictable versus unpredictable per Sloboda and Ford, 2019). The pieces shared the common theme of life’s end, death, and remembrance. However, this theme was made explicit only in selected concerts (through moderation, screen elements, and participation) to see whether affective priming might enhance emotional engagement and help tolerate the contemporary piece. A further format variation targeted the common program order by interlocking movements from the contemporary and romantic pieces in three concerts (see Table 2). This created an expanded musical context with continuous stylistic contrasts, intended to increase immersion, suggest alternative, less challenging ways of perceiving the contemporary piece, and adding a component of surprise and unpredictability.

Audience participation

While classical concerts have been considered epitomes of presentational performance in contrast to participatory formats (Turino, 2008), recent analyses suggest they also incorporate co-creation and participation aspects (passive versus active dimension per Sloboda and Ford, 2019; see also Clarke, 2005; Pitts, 2005). Accordingly, composers and programmers have experimented with explicitly participatory elements to enhance audiences’ sense of agency, contribution, and community (Toelle and Sloboda, 2021).

One concert in our series investigated participation effects on musical experience. Before the performance, audiences learned that the programmed compositions addressed farewell and death, with the contemporary piece specifically dedicated to deceased friends and colleagues. Audience members could write names of important deceased individuals on paper, which was then placed on stage-present boards. This inclusion of audience-chosen commemorated individuals in the musical remembrance aimed to increase personal and emotional engagement, improve contemporary piece accessibility, and strengthen intra-audience bonds.

Acoustic component

Finally, one concert also targeted the acoustic dimension. It was sought to enhance the sound’s enveloping and immersive qualities by distributing live audio through a loudspeaker array surrounding the audience.

To summarize, the concert formats comprised both conventional and artistic-experimental elements whose forms can be subsumed under the four key dimensions of concerts proposed by Sloboda and Ford (2019). Our concert formats and their varied elements thus address central aspects of theoretical debates and empirical findings on concert experience, as synthesized by Wald-Fuhrmann et al. (2021). They target the most important constitutive components of concerts (venue and staging, program, musicians, musician-audience relationship). They engage the central characteristics emerging from these components (framing and priming through the dedicated environment, co-presence and social experience, multisensory nature, meaningful relationships between pieces, liveness components of immediacy, unpredictability, social interaction, and shared experience). Finally, they aim at various experiential dimensions that research has identified as crucial for musical experience in general and concert experience in particular: aesthetic appreciation, emotional involvement, attention and immersion, musical understanding and intellectual stimulation, as well as feelings of connection with musicians and/or other audience members (Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2023).

Participants

The concert experiments were advertised via the concert listings of the two venues, but also via newsletters, media reports, and social media. People who were interested in visiting a concert had to book a ticket either as a concert visitor or as a research participant for a day that was convenient for them. They were informed about the starting time, the venue and which of the two ensembles would be performing, but did not receive any information regarding the concert format. In total, N = 802 people took part as research participants, that is, between 37 and 96 per concert. Their mean age was 43.9 years (SD = 17.5). Of these, 54.4% identified as female and 40.9% as male. For 77.9%, German was their first language. The sample had a very high education level, with almost 80% having a university degree (23.9% had a degree in natural sciences or engineering, 18.8% in music, arts, or cultural studies, and 36.2% in other humanities or social sciences). This was also reflected in their professional status and employment: 25.4% of the participants worked as medium or high-ranking employees or civil servants, 14.3% were university students, 13.5% pensioners, 11.7% workers or basic employees / civil servants, and 10.3% worked as freelancers or self-employed.

Participants had gone to 8.0 classical concerts on average in the previous year and reached an average score of 4.3 (SD = 1.0) on the GoldMSI (Müllensiefen et al., 2014) subscale of active engagement and 3.3 (SD = 1.5) on musical training. 146 participants came alone, while the others visited the concert with someone else.

In sum, the sample represents the typical classical concert audience in a German metropole relatively well, only the average age is somewhat lower than expected (Chen and Cabrera, 2023), which might be related to both the research context and the somewhat “younger”, more alternative and urban character of one of the two venues (venue 2) where the majority of concerts took place.

Procedure and technical setup

Participants arrived one hour before the concert started, gave their informed consent and filled out an entry questionnaire that asked about sociodemographic information, musical background, motivations and prior concert experiences. Trained assistants then fitted the physiological measurement apparatus to the participants at their seat in the hall. For each concert, 88 seats were equipped with a customized glove that held a hub from Biosignals Plux with sensors to measure blood volume pulse – HR – from the index finger, skin conductance – SC – from the middle and ring finger of the non-dominant hand, and a belt to measure respiration–RESP–from the belly. The pluxes were connected to a Raspberry Pi single-bord computer at the back of each seat that transmitted the data through a network to a central server controlled by a customized software. More details on the technical set-up that was custom developed for this research project are described in Tröndle et al. (accepted). Table 1 presents the music pieces, their order, and mean familiarity. Also during the concert, four (Pierre Boulez Saal) or eight (Radialsystem) Geutebrück infrared cameras that were placed on the ceiling above the stage filmed individual sections of the audience at 25 or 29.97 frames per second to document their behavior and facial expressions. After the concert, participants completed an exit questionnaire on their appreciation and experiences. The questionnaires were administered via a LimeSurvey mask on iPads. Questionnaires and physiological measurement were pretested in three concerts in 2020 (Tschacher et al., 2023b).

Measures and pre-processing

To assess participants’ appraisal and subjective experience, the exit questionnaire included items on the evaluation (15 items) and experience (18 items) of various aspects of the concert, as well as items from validated scales to measure piece-related aesthetic emotions (three individual items from the AESTHEMOS scale, see Schindler et al., 2017) and social experiences (SECS scale with five dimensions, see O’Neill and Egermann, 2022). Most of the ratings were based on 5-point Likert scales. In order to calculate response scores that summarize the items on evaluation and experience of concert aspects, participants’ agreement ratings of those items where initially subjected to exploratory factor analyses with oblimim promax rotation. Here, we identified five underlying factors that were subsequently represented by choosing the highest loading two to three items. We then ran a well-fitting confirmatory factor analysis on the subset of these items (χ2 = 240.259, df = 67, P < 0.001, cfi = 0.944, rmse = 0.057), that was used to calculate scores for each factor which we named (1) immersion, (2) intellectual stimulation, (3) evaluation of the performance, (4) venue experience, (5) evaluation of the concert design (Table 3 lists the items that belong to each dimension). A linear regression model showed that ratings of the item “liking of the concert overall” were mainly associated with the experience factor “evaluation of the performance” (β = 0.449*), and also weakly with “intellectual stimulation” (β = 0.149) and “venue experience” (β = 0.105), but not with “immersion” and “evaluation of the concert design”. Valid questionnaire data were collected from 764 (SECS) to 787 (Concert experience dimensions) audience members.

Physiological responses represented the physiological arousal component of emotion and experience (Scherer, 2005). In a procedure similar to the one used in Egermann and Reuben (2020), we calculated three types of physiological response scores per participant and musical movement. Skin conductance measurements were averaged per musical movement and participant. Subsequently, we z-standardized the resulting response variable across all observations. The HR signal was first low-pass filtered (with a cut-off frequency of 2 Hz). We subsequently calculated the mean inter-heartbeat interval of each participant for each musical movement. The resulting mean values where again z-standardized and subsequently inverted by multiplying them with −1 in order to achieve a more intuitive score that increases with heart rate (as opposed to one that decreases with increasing heart rate). The RESP signal was also low-pass filtered (0.35 Hz) and respiration rate was calculated with a peak-to-peak detection algorithm. We then calculated each participant’s mean respiration rate per musical movement and z-standardized the corresponding outcome values.

Before z-standardization of all SC, HR, and RESP response scores, we plotted all participants’ raw data separated by musical movement across time in order to identify any visible measurement errors and artifacts (that might have been caused by participant movement or sensor misplacement). Subsequently, we removed all erroneous response scores per movement and participant. This resulted in the removal of 1066 of SC response scores leaving 6324, of 686 HR response scores leaving 6704, and 606 RESP response scores leaving 6784.

To capture the audience’s expressive behavior, facial expressions were extracted from the camera recordings made in the venue 2 (concerts 3–11). We did not use data from the venue 1, because here, participants had to wear face masks as a protective measure against COVID-19. After synchronizing the film tracks from the various cameras (ensuring identical starting and ending points within each concert and across all concerts, using Adobe Premiere Pro CC 2023), we used a UnixTime timestamp displayed on a tablet held up in front of the audience just before the start of each concert to align the camera recordings with the physiological data. Then, we assessed the quality of each filmed face (up to 80 faces per concert). More than 50% of the given seats in the audience were captured by more than one of the eight cameras, which allowed us to select the video material offering the best perspective on each face. Certain factors hindered the analysis of facial expressions in all concertgoers (e.g., facemasks, individuals’ gaze direction, broad-rimmed glasses, full beards, etc.). In total, 391 individual faces were captured, of which 303 were of sufficient quality to be included in the analysis. Following the cropping of individual videos for each face, Affectiva Media Analytics, an automated facial expression analysis software (reliability comparable to EMG findings, Kulke et al., 2020), was used. Based on the emotional facial action coding system (Ekman, Friesen and Hager, 2002), the software captures muscle movements in 23 facial “action units”, which correspond to various emotional expressions either individually or in specific combinations. In addition to identifying basic emotions (anger, sadness, disgust, fear, joy, surprise, contempt) and more complex facial expressions (sentimentality, confusion, neutrality, and attention), the software also provides aggregated indicators of emotional expression (emotional engagement and valence). In this analysis, we focus on the facial expression aggregates of emotional engagement (general measure of overall engagement or expressiveness) and valence (degree of how positive or negative the facial expression is) because we aimed to reduce the number of dependent variables and therefore chose those two signals that can be seen as a summary of all other facial expressions identified. Similarly to physiological response data, we calculated the mean for valence and engagement per participant and musical movement, leading to a dataset of 3.030 observations. We then z-standardized the resulting two variables.

In the end, dependent variables were z-scored and included:

from the questionnaires:

-

(1)

Three relevant single-item ratings (evaluation of the concert as a whole, experience of being moved, evaluation of the interaction between the musicians and the audience),

-

(2)

Five dimensions of concert experience (musical immersion, intellectual stimulation, evaluation of performance, venue experience, evaluation of the concert design; see Table 3 for individual items belonging to these dimensions),

-

(3)

Five dimensions of social experience (SECS, O’Neill and Egermann, 2022),

-

(4)

Piece-specific ratings of aesthetic emotions that were selected from the AESTHEMOS scale (Schindler et al., 2017), i.e., (this piece made me) happy, annoyed, melancholic;

from the physiological recordings:

-

(5)

Skin conductance level,

-

(6)

Heart rate,

-

(7)

Respiration rate;

from automatic analyses of audience members’ facial expressions:

-

(8)

Emotional valence (from negative to positive),

-

(9)

Overall emotional engagement.

Analyses

It was our main aim to establish the type and size of effects of concert formats on various measures of audience experience. Since our data were gathered in real-life contexts where many of the parameters were beyond our experimental control, we used a rigorous statistical approach for our analyses fitting models that included not only predictors of interest, but also potentially confounding factors. Depending on the data structure, we fitted either GLMs (for questionnaire data on concert experience and social experience) or HLMs (for piece-related questionnaire data on aesthetic emotions, as well as for continuous data, i.e., physiological responses and facial expression). Accordingly, we either used the GLM procedure (GLMs) or the MIXED procedure (HLM) in SPSS. Fixed effects were concert format dummy variables (see Table 2), as well as person-related variables, that included age, gender, number of classical concert visits in the previous year, time of listening to classical music, GoldMSI Active Engagement, GoldMSI Musical Training, BIG-5 personality traits, while piece was defined as a repeated effect (only HLMs). Person-related variables were included in the models in order to control for differences in audience composition between the concerts but will not be reported in the results section. We followed a forward model fitting approach. In a first run of model fitting, we included all person-related characteristics as predictor variables. In the second run we added the concert format variables and the person-related variables with a F-test (GLMs) or a t-test (HLMs) value larger than 1 in the initial run. This way, we only included relevant person characteristics while also keeping linear models as parsimonious as possible. For HLMs, we fitted an additional first run in which we choose the best fitting residual covariance (R) matrix (diagonal, compound symmetry or compound symmetry heterogeneous) based on the AIC value. After this, the same steps as in the GLMs followed. This was done to account for the repeated measurement structure of the data.

Results

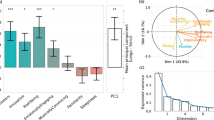

Overall, we found that heart rate and aesthetic emotions (in particular, being annoyed) were most susceptible to format changes, while intellectual stimulation, evaluation of the performances, SECS satisfaction, SECS depth of processing, and emotional engagement did not respond to our concert variations. Further, those concerts that differed very clearly from the standard format led to more and stronger responses than those with only relatively subtle modifications. For an overview of all effects see Table 4.

Effects of the concert hall

As expected, the two venues were evaluated very differently by the audiences: People enjoyed the classical venue (Pierre Boulez Saal) more than the modern Radialsystem (effect on “evaluation of venue”, β = 0.696, t = 6.247, P < 0.001), which was also associated with higher ratings of the concert as a whole (β = 0.270, t = 2.249, P = 0.025), deeper degrees of “musical immersion” (β = 0.233, t = 1.986, P = 0.047) and a more positive “evaluation of concert design” (β = 0.321, t = 2.667, P = 0.008), despite the absence of any “experimental” formatting in Pierre Boulez Saal. We also found that skin conductance responses tended to be stronger in the Pierre Boulez Saal (β = 0.247, t(595.218) = 1.94, P = 0.053). Further, Radialsystem was indeed preferred by younger audience members (mage = 40.2 years (SD = 16.0) compared to mage = 56.1 years (SD = 16.6) in venue 2).

Effects of the ensembles’ prestige and formation

The concerts performed by the Yubal Ensemble attracted fewer listeners (mean n = 56.3) than those by the Ensemble Epitaph (mean n = 79.5) which might reflect the higher prestige of the musicians playing in the latter. Further anticipated effects on appreciation and experience were not found. A significant effect of ensemble was only found for one social experience dimension: Concerts played by the Ensemble Epitaph were related to higher self-definition of the participants with the audience (i.e., individual’s recognition of similarities among group members or between themselves and the group; β = 0.285, t = 2.304, P = 0.021).

Effects of moderation and interviews with musicians

The presence of a moderator who interviewed the musicians during the concert successfully facilitated piece comprehension and programming understanding, as evidenced by enhanced emotional engagement: AESTHEMOS ratings showed that expressed and felt emotions became more congruent, with “made me happy” ratings decreasing for pieces by the classical (β = −0.336, t(1081.695) = −2.296, P = 0.022) and contemporary composers (β = −0.552, t(1135.970) = −3.492, P < 0.001), while “made me melancholic” ratings increased for these same pieces (classical piece: β = 0.339, t(1090.718) = 2.273, P = 0.023; contemporary piece: β = 0.674, t(1160.914) = 4.280, P < 0.001). This emotional alignment was also reflected in facial expressions, which showed more negative emotional valence during these two pieces (classical piece: β = −0.385, t(439.155) = −2.281, P = 0.023; contemporary piece: β = −0.199, t(2014.783) = −2.347, P = 0.019). The moderation also succeeded in making the contemporary work more accessible, as AESTHEMOS ratings of “annoyed me” for the contemporary piece were significantly lower in this condition (β = −0.337, t(1006.758) = −2.027, P = 0.043). Furthermore, the intervention effectively broke the “fourth wall” and fostered personal audience-performer connections, as evidenced by significantly higher ratings on the single item “interaction between the musicians and the audience” (β = 0.716, t = 4.451, P < 0.001). Finally, we found a non-significant trend for respiration to be faster in this concert (β = 0.321, t(685.371) = 1.928, P = 0.054).

Effects of a movement-specific lighting

Although we did not find the expected effects on immersion, lighting influenced some other dimensions: It reduced the ratings of the “interaction between the musicians and the audience” (β = −0.381, t = 2.530, P = 0.012), as well as the experience of the venue (β = −0.272, t = −1.971, P = 0.049), and was also associated with a slower heart rate (β = −0.326, t(647.269) = −1.984, P = 0.048).

Effects of visual augmentation (video screen)

The additional visual information presented on a large screen on the stage had only some of the anticipated effects, in particular, it led to an alignment of expressed and felt emotions (lower ratings of “made me happy” (β = −0.331, t(762.023) = −3.133, P = 0.002)) and made the contemporary piece more accessible (lower ratings of “annoyed me” (β = −0.389, t(791.802) = −3.669, P < 0.001)). But we found no significant effect on audience-musicians relationship. Instead, it led to a decrease of the social experience dimension attention towards other audience members (β = −0.404, t = −2.491, P = 0.013), while the change in solidarity just missed significance (β = −0.319, t = −1.958, P = 0.051). Further, we found positive effects on skin conductance (β = 0.427, t(594.708) = 2.720, P = 0.007) and heart rate (β = 0.478, t(646.702) = 2.938, P = 0.003).

Effects of a modified program structure

The interlocking of the movements by the contemporary and the romantic piece in three of the concerts led to mixed effects: While it was able to increase the audience’s musical immersion (β = 0.312, t = 2049, P = 0.041), it was also associated with increased feelings of being annoyed (β = 0.341, t(793.684) = 3.218, P = 0.001).

Effects of audience participation

The audience participation concert showed mixed results regarding its intended effects. Contrary to expectations for increased personal and emotional engagement, this concert led to lower ratings in two social experience dimensions: attention to other audience members (β = −0.450, t = −2.751, P = 0.006) and self-definition as part of the audience (β = −0.333, t = −2.052, P = 0.041), suggesting weakened rather than strengthened intra-audience bonds. However, the intervention did improve contemporary piece accessibility, as evidenced by decreased ratings of being annoyed (β = -0.226, t(792.580) = -2.121, P = 0.034). Additionally, we found that heart rate was on average faster in this concert (β = 0.398, t(647.146) = 2.536, P = 0.011), which may indicate increased physiological engagement despite the contrary social bonding effects.

Effects of immersive sound

Using a loudspeaker array to envelop the audience in the sound was not related to self-reports of higher immersion, but only associated with an increased heart rate (β = 0.574, t(647.156) = 3.578, P < 0.001).

Relative contribution of concert formats on aesthetic experience

In the context of our underlying framework, it would be important to quantify the strength of the relative influence of the concert frame on the aesthetic experience in comparison to the two other main factors, i.e., the music and the person. There is, however, no straightforward way to do this. But we may at least propose the following approximation: Our models allow to directly compare the effects of person-related and concert format variables, in the case of the Hierarchical Linear Models (HLMs) also effects of musical pieces, with the help of parameter estimates (β values). The strength of the influence of the music can only very indirectly be estimated from the delta between R2 = 1.00 and the R2 values of our models. However, while the list of frame components relevant in our experimental concerts is complete, the same cannot be said of the person-related variables. Although we captured a large variety of such variables in accordance with the existing literature, it is still likely that other influential factors exist that were not accounted for in our study.

In the case of the five dimensions of concert experience and appreciation, the following picture can be seen: The General Linear Models (GLMs) including frame and person-related variables explain between 10 and 23% of the total variance per dimension (adjusted R2 values). Parameter estimates for person-related variables range from 0.071 to 0.209 and for frame components from 0.233 to 0.696.

A similar pattern emerges for the five dimensions of social experience, although the explained variance is much smaller (adj. R2 values range from 0.016 to 0.067). Parameter estimates for person-related variables range from 0.084 to 0.198 and for frame components from 0.285 to 0.450.

Physiological responses were more often associated with frame and music (pieces) predictors than with person-related variables. Parameter estimates for person-related variables range from 0.081 to 0.436, for frame components from 0.326 to 0.574 and for musical pieces from 0.031 to 0.242.

Overall emotional engagement as measured from facial expressions was only associated with two person-related factors (β values of 0.099 and 0.109) and one frame component (β = 0.050), while emotional valence was associated with two interaction effects of frame component and musical piece (β values of 0.199 and 0.385).

Discussion

Our results show that in a live context, people’s aesthetic experience is not exclusively dependent on the music and how it is performed by the musicians, but co-constituted by frame components such as the space, the visual and acoustic design of the performance, as well as verbal primings and modifications of the typical roles associated with classical musicians and audiences. Thus, we could experimentally corroborate the theoretical framework we presented in an earlier article (Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2021) and add quantitative findings from an ecologically valid setup to the existing literature on the relevance of the context for aesthetic experiences (Hargreaves, 2012; Leder and Nadal, 2014).

Effects on the four levels of measurement

Overall, we found effects on all four levels of measurement (appraisal, subjective experience, physiological response, expressive behavior), but in contrast to controlled laboratory experiments on emotions (e.g., Bradley et al., 2001; Grewe et al., 2009; Fuentes-Sánchez et al., 2021) the effects did almost never appear on all levels at the same time. This confirms the benefit of our multilevel approach, but also poses some questions. At this stage of research, we cannot fully interpret this observation. But it seems likely that the naturalistic context and the data collection design we had chosen were at least in part responsible for this. While controlled studies on emotion focus on short, individual episodes and their direct measurement, our concerts unfolded over a much longer timespan of c. 70 min. Appraisal and experience ratings were collected post hoc from memory and our continuous ad hoc data (physiological responses, facial expressions) was averaged across musical movements. However, in the light of the disadvantages of the design–which we had knowingly accepted in order to allow as much ecological validity as possible–we believe that the effects we did find are robust. Further studies could try to find ways to improve multimodal measurement setups and refine analyses, e.g., by zooming in on individual sections and events. Some other studies, e.g., have collected self-reports after each musical unit such as a piece or movement of a piece, which resulted in a stronger correlation between subjective experiences and physiology (Egermann et al., 2013; Egermann and Reuben, 2020; Merrill et al., 2023).

Despite the post hoc design, the majority of effects were found on the levels of subjective appraisal and experience. Of these, three of the concert-specific appreciation and experience dimensions, i.e., music immersion, evaluation of the venue, evaluation of concert design, as well as two of our three relevant AESTHEMOS ratings were particularly susceptible to the concert frame, but not the overall appreciation of the concert or music-immanent dimensions such as intellectual stimulation and evaluation of the musicians. As in earlier studies by Swarbrick et al. (2021) as well as Swarbrick and Vuoskoski (2023), concert format did not influence how moved the audience felt. Also, the five dimensions of social audience experience did only rarely respond to the format changes, and if so, felt connection with the other audience members decreased. We see this as an indication for a specific and selective rather than global effect of the concert frame on the aesthetic experience of a live audience. In particular, the appreciation of the music itself and its performance, as well as of the concert as a whole seem to be difficult to affect by the concert frame. This is in line with results from our study on concert streams (Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2023) and an analysis of social experience dimensions in live classical concerts that were found to be related to overall enjoyment, but not to emotional responses to the music (O’Neill and Egermann, 2022). A dissociation between aesthetic judgment on the one hand and enjoyment of and affective responses to a live music performance on the other had already been found by Thompson (2006). It also confirms our approach to understand musical experiences in live concerts as multi-dimensional and to measure them in a nuanced and differentiated manner. We would not want to generalize our findings on the social experience dimensions, however. That almost none of our format variations succeeded in increasing social experience might rather be the obvious result of the fact that all concerts kept the typical setup of an audience seated in tiers and facing towards the stage without any encouragement to interact. While this was mainly done for technical and practical reasons, it can be expected that other audience constellations might positively influence the social experience of an audience as was already shown in studies that compared various types of concert streams or used an VR environment (Shin et al., 2019; Onderdijk et al., 2021; Swarbrick et al., 2021; Wald-Fuhrmann et al., 2023; Swarbrick and Vuoskoski, 2023).

Of the physiological responses we collected, heart rate responded most often to format changes and was affected by both visual (lighting, screen) and acoustic stimuli (immersive sound), but also by an externally triggered change of listening mode (participation). When compared to the related questionnaire results, increases in heart rate seem to be associated with a more positive or engaged listening experience, while a decrease seems to signal a less positive experience. This interpretation is also supported by earlier studies that have shown that heart rate is not just an index of arousal, but also of positive aesthetic experiences (of music) (Blood and Zatorre, 2001; Salimpoor et al., 2009). In particular, Czepiel et al. (2021) reported heart rate in live concerts with the same musical programm as ours to be predicted by self-reported positive emotions, while Tschacher et al. (2023b) found increased heart-rate synchrony of a concert audience to be related to being moved, immersed and feeling inspired by a piece.

An effect of concert formats on expressive facial behavior was found in only one case which, however, was congruent with the questionnaire data. In principle, expressive behavior of the audience is not part of the classical concert etiquette. Due to the typical seating arrangement of tiers it cannot easily fulfill a communicative function as it does in many real-live social situations or concerts of other music genres. It is therefore plausible to expect only limited and unsystematic facial expressions in classical concert audiences. In addition, the captured facial expressions seem to occur more as a direct response to the music and its expressiveness (as in Kayser et al., 2022) and are not strongly influenced by concert formats. Last but not least, automated facial expression analysis in ecologically valid concert situations with many visitors still faces limitations due to poor lighting conditions and the resolution at which individual faces can be captured, which might also explain the small observed effects.

Concert format effects

When creating the various concert formats that served as experimental stimuli, we drew upon four key sources: the practical expertise and theoretical reflection of the project’s artistic director, systematic observation of current experimental practices in the concert field, established theories of concert performance and liveness, and empirical research on audience experience. These format variations were designed to target specific experiential dimensions, and our results reveal distinct patterns of which interventions successfully influenced particular aspects of concert experience.

Emotional alignment and congruence

Three format components successfully enhanced the congruence between expressed and felt emotions, suggesting that certain interventions can facilitate more authentic emotional engagement with musical content. Moderation and musicians’ interviews produced the strongest effects in this domain, with audiences showing decreased “made me happy” ratings and increased “made me melancholic” ratings for both classical and contemporary pieces, accompanied by corresponding changes in facial expressions. Visual augmentation and information via a screen display achieved similar but more limited emotional alignment, reducing “made me happy” ratings without the complementary increase in melancholic responses. This emotional alignment reflects successful facilitation of piece comprehension and programming understanding, as these interventions helped audiences connect with the inherently melancholic themes of farewell and death that characterized our program.

The differences that emerged between the verbal and the visual priming route can be explained by drawing from general research on priming. Both modalities likely activated semantic and affective priming mechanisms, but with different strengths and processing pathways (Klauer and Musch, 2003; Storbeck and Robinson, 2004). The verbal moderation condition combined semantic priming—through explicit activation of death-related conceptual networks via musicians’ personal accounts—with direct affective priming through the emotional valence of the spoken testimonials. This dual-mechanism approach created stronger spreading activation across both semantic and emotional memory networks (Storbeck and Robinson, 2004). In contrast, the visual presentation primarily relied on semantic priming, as the photographs with names and dates activated death-related associations but provided less direct affective content.

The concert involving personal memorial contributions from audience members (audience participation), in contrast, failed to produce emotional deepening effects. This null finding can be explained by several priming mechanisms: the temporal distance between writing personal names before the concert and the musical experience likely exceeded effective priming durations, the lack of specific contingency between personal names and particular musical pieces weakened the prime-target relationship, and the highly personal nature of the stimulus may have triggered emotional regulation mechanisms that reduced rather than enhanced engagement (Klauer and Musch, 2003). This finding underscores that effective contextual priming requires appropriate temporal contiguity and optimal emotional intensity, not merely thematic relevance.

Contemporary music accessibility

Reducing negative responses to contemporary music emerged as one of the most consistent effects across our format variations. Moderation and musicians’ interviews significantly reduced annoyance ratings for the contemporary piece, likely through the personal contextualization provided by the composer’s presence and the musicians’ relationship narratives. Visual augmentation achieved even stronger effects in this domain, with the largest reduction in annoyance ratings observed across all interventions. The biographical information and photographs of deceased individuals provided concrete, relatable context for the abstract contemporary composition. Audience participation also contributed to contemporary music accessibility through reduced annoyance, as the personal connection to themes of remembrance created emotional investment in the musical content. Notably, these three successful interventions all involved personalizing or contextualizing the contemporary work through additional verbal or visual information or emotional connection, suggesting that accessibility barriers to contemporary music may be overcome through enhanced understanding and personal relevance rather than purely musical strategies, in line with a study on the different effects of emotional vs. music-analytical program notes (Fischinger et al., 2020).

Overall, our interventions effectively addressed typical barriers towards contemporary classical music by providing contextual scaffolding that reduced cognitive load and uncertainty while creating personal relevance (Schäfer and Sedlmeier, 2009). This supports theories of music accessibility emphasizing that engagement with contemporary works may depend more on enhanced understanding and emotional connection than purely musical factors (Fischinger et al., 2020), transforming the listening experience from effortful processing of unfamiliar stimuli to meaningful engagement with personally relevant content.

Physiological arousal and engagement

Heart rate increases emerged as a consistent physiological response across multiple format interventions, suggesting that departure from traditional concert conventions inherently activates audiences at a biological level. Immersive sound produced the strongest heart rate elevation, followed by visual augmentation, audience participation, and moderation (trend level). This pattern suggests that multisensory enhancement and active engagement components most effectively increase physiological activation.

Social experience and connection

Format effects on social dimensions revealed complex, often competitive relationships between different types of connection and attention. Musicians-audience interaction was most strongly enhanced by moderation and interviews, confirming the intervention’s success in breaking the “fourth wall” and fostering personal connections. However, this came with subtle costs elsewhere, as both visual augmentation and audience participation reduced attention to other audience members, while participation also decreased self-definition as part of the audience.

This pattern suggests an “attention economy” within concert experience, where enhanced focus on specific relational aspects (musician personalities, visual content, personal memories) competes with broader social awareness and collective identity formation.

Venue effects and environmental priming

Concert venue emerged as a foundational environmental priming factor influencing multiple experiential dimensions simultaneously. In particular, perceived venue quality was directly related to core measures of concert experience including overall concert liking, musical immersion, and concert design appreciation.The traditional venue (Pierre Boulez Saal) produced consistently higher ratings across these dimensions while also trending toward stronger skin conductance responses. These effects demonstrate the venue’s dual role as environmental prime and facilitator of optimal listening conditions, aligning with research on contextual priming where physical environments automatically activate associated cognitive schemas and behavioral expectations (Smith and Vela, 2001). The traditional concert hall likely primed classical music listening schemas, enhancing receptivity to the musical content through environmental congruence.

Although younger audiences seemed to be attracted by the more modern and unconventional industrial environment, this attraction did not transform into a more positive concert experience. This counter-intuitive finding suggests that venue effects may be mediated by cultural associations and aesthetic expectations that operate below conscious preference levels, with traditional concert hall features resonating more strongly with audiences already committed to classical music conventions. This supports theories of schema-congruent priming, where environmental cues activate culturally learned expectations that facilitate or hinder processing of subsequent stimuli (Herring et al., 2013). The industrial venue may have created incongruent priming for traditional classical music, requiring additional cognitive resources to reconcile the environmental-musical mismatch, potentially explaining the reduced immersion and evaluation scores despite initial aesthetic appeal.

Musical immersion and deep engagement

Only two format components successfully increased musical immersion: the traditional venue and modified programming through interlocking movements. The venue effect aligns with our theoretical predictions about environmental optimization for musical focus, while the programming effect suggests that stylistic contrasts and an unexpected series of events may increase immersion by sustaining attention, in line with general research on attention focus and working memory (Lavie, 2010).

Implications for concert design

Re-inventing the classical concert has been a high priority for concert managers and musicians in light of the often discussed crisis of the classical concert. The concert venue and the concert format have been in the center of these artistic deliberations and experiments. Our results confirm from an experimental-psychological perspective that these efforts are worthwhile (but see Tröndle et al., 2025). They also suggest that concert format effects may operate through distinct mechanisms rather than uniformly enhancing all aspects of experience, though these findings should be interpreted with appropriate caution given that each format variant represents only one of countless possible implementations.

The most consistent effects emerged from interventions that provided additional context, meaning, or personal connection to a highly demanding musical content—moderation, visual content on a screen, and audience participation—suggesting that format innovations may be most effective when they address cognitive and emotional barriers to engagement rather than simply intensifying sensory experience. However, it is important to note that alternative approaches to these interventions (different types of visual content, varied moderation styles, or other forms of participation) might yield substantially different results.

The venue effects revealed a fundamentally different mechanism of influence, operating through purely musical and concert-inherent components—architectural acoustics, environmental comfort, and aesthetic appropriateness—rather than through added content or interaction elements. This venue influence on musical immersion and overall appreciation represents a more direct path to enhanced musical experience, suggesting that optimizing fundamental concert conditions may provide a foundation upon which other format innovations can build. The robustness of these venue effects across multiple experiential dimensions indicates that environmental factors may indeed set boundary conditions within which other format innovations operate.

The consistent pattern of attention trade-offs across multiple interventions—where enhancing one type of connection or engagement came at the cost of others—suggests an important principle for format design, though the specific manifestation of these trade-offs would likely vary considerably with different implementation approaches. This indicates that format designers should carefully consider their primary experiential goals and accept that comprehensive enhancement across all dimensions may not be achievable simultaneously.

Finally, the dissociation between behavioral effects (attendance) and experiential effects (appreciation, engagement) observed for ensemble prestige highlights the importance of distinguishing between factors that attract audiences and those that enhance their actual concert experience. However, the specific balance between prestige and collaborative excellence observed in our study represents just one possible configuration of these factors.

Given the preliminary nature of systematic experimental research on concert formats, these implications should be viewed as initial insights rather than definitive principles, requiring further investigation across varied implementations and contexts to establish their generalizability and their usefulness for concert practitioners.

Limitations and future perspectives

Most limitations of our study need to be considered in light of the unavoidable trade-off between an ecologically valid study design (with high external validity) and precise control over manipulations and measurements (with high internal validity) (see also Danielsen et al., 2023). For instance, some concert variants attracted fewer participants than others, leading to potentially smaller statistical test power for some concert format effects tests.

This trade-off also applied to the recording of audience faces for facial expression analysis. A more technically optimized setup—with brighter lighting, a greater number of cameras positioned closer to the audience, and instructions asking participants to keep their faces uncovered and oriented toward the stage—would likely have increased the number of analyzable faces and allowed for the detection of more subtle facial expressions. However, such adjustments would have compromised the naturalness of the concert experience. Future studies could improve data quality while preserving ecological validity by using higher-resolution infrared cameras and strategically positioned devices with optimized placement.

Musical experiences in a concert are dynamic and may intensify, weaken, or change their character in response to musical developments and the varying character of individual pieces and movements. These dynamics were not fully captured by our post-concert questionnaires, which may have resulted in less differentiated findings regarding the subjective experience. To partially account for this, we used continuous measurement of physiological responses and facial expressions. However, future studies should increasingly substitute retrospective questionnaires with continuous measurement methods that follow audience experiences and listening behavior with higher temporal resolution.

This approach would require researchers to identify valid objective indices of various relevant subjective experience dimensions—a goal that has only been partially accomplished and may not be possible in all cases. Promising new avenues include recordings of audience bodily actions and movements, analyzed for their synchronization (e.g., Seibert et al., 2019; Tschacher et al., 2024) or for moments of collective and music-related “stilling” (Upham et al., 2024; Martin and Nielsen, 2024). From a completely different angle, also qualitative data can meaningfully complement quantitative data types. Böndel et al. (2025) present results of post-concert interviews conducted within our research project, providing additional nuanced insights on how the different concerts were experienced.

The non-representative nature of our individual concert format variants raises questions about generalizability to other potential artistic interventions. However, we believe the study’s main contribution is not to prove that specific interventions tested will always produce the reported effects, but rather to demonstrate that changes to the concert frame can systematically alter audience musical experiences, even when the musical content remains constant. This establishes the principle of format-dependent experience modulation and provides a theoretical framework for understanding how different priming mechanisms operate in concert settings.

Furthermore, our findings should be understood within their specific cultural context. It remains to be explored how different audiences within non-European or non-Western-art-music contexts would respond to similar concert format manipulations, and whether the priming mechanisms we identified operate on a more general or a culturally specific level.

Several avenues for future investigation emerge from our findings:

-

Systematic variation of format elements: Testing different implementations of verbal, visual, and environmental priming as well as sensory intensification to establish optimal parameters for various musical genres and audiences

-

Cross-cultural validation: Examining whether semantic, affective, and environmental priming mechanisms operate similarly across different cultural contexts and musical traditions

-

Long-term effects: Investigating whether format-enhanced concert experiences influence subsequent music listening behavior, concert attendance patterns, or musical preferences

-

Individual differences: Exploring how personality traits, musical training, and demographic factors moderate responses to different priming interventions

-

Real-time measurement integration: Developing more sophisticated continuous monitoring techniques that can capture moment-to-moment changes in attention, engagement, and emotional response

Overall, this study provides important methodological and topical contributions to current research on the constituents and experiential dimensions of liveness, the influence of contextual factors on aesthetic experiences, and large-scale quantitative research in naturalistic environments. By identifying specific psychological mechanisms underlying format effects—particularly various forms of priming—our results offer practitioners in live music concrete theoretical frameworks for developing promising new approaches to the classical concert to further realize its specific potential for affording intense, rewarding, and social experiences with music while adapting to contemporary audience needs and expectations.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Auslander P (1999) Liveness: performance in a mediatized culture. Routledge, London

Baym NK (2018) Playing to the crowd: Musicians, audiences, and the intimate work of connection. New York University Press, New York

Becker HS (1982) Art worlds. Univ. of California Press, Berkeley

Behne K-E, Wöllner C (2011) Seeing or hearing the pianists? A synopsis of an early audiovisual perception experiment and a replication. Musi Sci 15:324–342

Beranek LL (2003) Concert halls and opera houses: music, acoustics, and architecture. Springer, New York

Besseler H (1926) Grundfragen des musikalischen Hörens. In: Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters Band 32. CF Peters, Leipzig, pp 35–52

Blood AJ, Zatorre RJ (2001) Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:11818–11823

Böndel H, Weining C, Tröndle M (2025) Immediate and lasting experiences of a classical concert. J Cult Manag Cult Policy 11:16–39

Bradley MM, Codispoti M, Cuthbert BN et al. (2001) Emotion and motivation I: defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion 1:276–298

Brown A (2004) Smart concerts: orchestras in the age of edutainment. In: Knight Foundation Issues Brief Series No. 5. The Knight Foundation, Miami, FL, pp 1–16

Brüstle C (2013) Konzert-Szenen–Bewegung, Performance, Medien: Musik zwischen performativer Expansion und medialer Integration 1950–2000. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart

Bugiel L (2015) Wenn man von der Krise spricht… Diskursanalytische Untersuchung zur Krise des Konzerts in Musik- und musikpädagogischen Zeitschriften. In: Cvetko AJ, Rora C (eds) Konzertpädagogik. Shaker-Verlag, Aachen, pp 61–81

Burgess RC (2014) The history of music production. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Burland K, Pitts S (eds) (2014) Coughing and clapping: Investigating audience experience. Routledge, London

Chapados C, Levitin DJ (2008) Cross-modal interactions in the experience of musical performances: physiological correlates. Cognition 108:639–651

Chen Y, Cabrera D (2023) Environmental factors affecting classical music concert experience. Psychol Music 51:782–803

Clarke E (2005) Ways of listening: an ecological approach to the perception of musical meaning. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Coutinho E, Scherer KR (2017) The effect of context and audio-visual modality on emotions elicited by a musical performance. Psychol Music 45:550–569

Czepiel A et al. (2021) Synchrony in the periphery: inter-subject correlation of physiological responses during live music concerts. Sci Rep 11:22457

Danielsen A, Paulsrud TS, Hansen NC (2023) “MusicLab Copenhagen”: the gains and challenges of radically intedisciplinary concert research. Music Sci 6:1–14

Danto AC (1964) The art world. J Philos 61:571–584

Egermann H, Pearce MT, Wiggins GA et al. (2013) Probabilistic models of expectation violation predict psychophysiological emotional responses to live concert music. Cognit Affect Behav Neuroci 13:533–553

Egermann H, Reuben F (2020) “Beauty is how you feel inside”: aesthetic judgments are related to emotional responses to contemporary music. Front Psychol. 11:510029

Ekman P, Friesen WV, Hager JC (2002) Facial action coding system: manual and investigator’s guide. UT Research Nexus, Salt Lake City

Fischinger T, Kaufmann M, Schlotz W (2020) If it’s Mozart, it must be good? The influence of textual information and age on musical appreciation. Psychol Music 48:579–597

Forsyth M (1985) Buildings for music: the architect, the musician, and the listener from the seventeenth century to the present day. MIT Press, Cambridge

Fuentes-Sánchez N, Pastor R, Escrig MA et al. (2021) Emotion elicitation during music listening: subjective seld-reports, facial expression, and autonomic reactivity. Psychophysiology 58:e13884

Goffman E (1974) Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Harper & Row, New York

Grewe O, Kopiez R, Altenmüller E (2009) The chill parameter: goose bumps and shivers as promising measures in emotion research. Music Percept 27:61–74

Griffiths NK, Reay JL (2018) The relative importance of aural and visual information in the evaluation of Western canon music performance by musicians and nonmusicians. Music Percept 35:364–375

Hargreaves DJ (2012) Musical imagination: perception and production, beauty and creativity. Psychol Music 40:539–557

Heister H-W (1983) Das Konzert: Theorie einer Kulturform. Heinrichshofen, Wilhelmshaven

Herring DR et al. (2013) On the automatic activation of attitudes: a quarter century of evaluative priming research. Psychol Bull 139:1062–1089

Johnson JH (1995) Listening in Paris: a cultural history. University of California Press, Berkeley

Kayser D, Egermann H, Barraclough NE (2022) Audience facial expressions detected by automated face analysis software reflect emotions in music. Behav Res 54:1493–1507

Klauer KC, Musch J (2003) Affective priming: findings and theories. In: Musch J, Klauer KC (eds) The psychology of evaluation: Affective processes in cognition and emotion. Routledge, New York, pp 7–51

Kolb BM (2001) The effect of generational change on classical music concert attendance and orchestras’ responses in the UK and US. Cult Trends 11:1–35

Kramer L (2007) Why classical music still matters. University of California Press, Berkeley

Kulke L, Feyerabend D, Schacht A (2020) A comparison of the affectiva iMotions facial expression analysis software with EMG for identifying facial expressions of emotion. Front Psychol 11:329

Lange E, Fünderich J, Grimm H (2022) Multisensory integration of musical emotion perception in singing. Psychol Res 86:2099–2114

Lavie N (2010) Attention, distraction, and cognitive control under load. Curr Direct Psychol Sci 19:143–148

Leder H, Belke B, Oeberst A, Augustin D (2004) A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. Br J Psychol 95:489–508