Abstract

Current climate models suggested that Antarctic sea ice cover would decrease substantially under cumulative CO2 emission, but little is known whether large decrease in Antarctic sea ice can influence the occurrence of strong El Niño. Using time slice coupled and uncoupled model experiments, we show that in response to half reduction of Antarctic sea ice projected near the end of the 21st century, the frequency of strong El Niño would be increased by ~40%. It is contributed by enhanced thermocline, Ekman, and zonal advective positive feedbacks that are partly offset by enhanced thermodynamic damping. The strong warming and weakened westerly winds in the southeastern Pacific generate an anomalous Rossby wave propagating into the eastern subtropical and tropical Pacific, favoring stronger El Nino, and air-sea coupling and ocean feedbacks play a critical role in the teleconnection. Unexpectedly, compare to halved Antarctic sea ice, the ice-free Antarctic leads to a decrease in the frequency of strong El Niño, which is largely due to a substantial increase in thermodynamic damping. We also show that a large portion of the increase of strong El Niño events under greenhouse warming might be connected with Antarctic sea-ice loss, though increased greenhouse gas plays an important role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sea ice in the Southern Ocean plays a critical role in determining Antarctic and global climate through a multitude of dynamic and thermodynamic processes. Large anomaly in Antarctic sea ice cover strongly influences air-sea exchanges of heat, moisture, salt, and gas fluxes, which have profound effects on atmospheric circulation in southern high and mid-latitudes, i.e., the polarity of the Southern Annular Mode and the scale of Polar and Ferrel circulations can be altered by increased Antarctic sea ice cover and the strengthen and position of the mid-latitude tropospheric jet stream can be influenced by decreased Antarctic sea ice cover1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Antarctic sea ice change also strongly influences stratification and overturning circulation in the Southern Ocean, rearranging glacial and interglacial stages9,10,11.

Unusual variability of Antarctic sea ice extent has been observed since the satellite era, a long-term significant increase since the late 1970s, reaching a record high in late September, 2014 (the first time above 20 million km2), an unprecedented plunge of the ice extent from 2014 to 201712, and 2022–2024 are the three lowest in the satellite record (the first 3-year below 2 million km2)13,14. Almost all climate models from the most recent phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) showed that Antarctic sea ice extent would decrease substantially during the 21st century for all emission scenarios15. A recent synthesis of proxy studies indicated that the coverage of Antarctic sea ice during the warmer Last Interglacial was about 50% of that of present day16.

Two recent coupled model studies suggested that large reduction of Antarctic sea ice coverage could have effects reaching the tropics, resulting in a warming of the tropical Pacific17,18. However, little is known whether the projected substantial decrease in Antarctic sea ice by CMIP6 can alter the frequency of strong El Niño events (an important tropical climate mode with that affects weather and climate worldwide), and whether it is sensitive to the magnitude of the reduction of Antarctic sea ice. The two coupled model studies17,18 examined the effects of reduced Antarctic sea ice on the mean tropical climate with ocean and atmosphere coupling, but the annual cycle of Antarctic sea ice cover is changed indirectly by modulating Antarctic energy balance. One study is to add an artificially seasonally varying downward longwave radiation17 and the other study is to reduce snow/sea ice albedo18. The artificial radiative flux indirect approach assumes that change in sea ice cover has a linear relationship with change in downwelling longwave radiation, but such relationship does not hold in summer19. The albedo indirect approach is not effective in adjusting year-round sea ice change because of little sunlight during polar night. Thus it is hard to precisely separate and identify the role of Antarctic sea-ice loss in the coupled climate model through these two approaches.

In this study, firstly, three time slice coupled model experiments based on the Climate Earth System Model version 1.2 (CESM1.2)20 are performed by directly changing Antarctic sea ice cover (see “Methods”), which allow direct assessment whether different amounts of the reduction of Antarctic sea ice have detectable and different impacts on the frequency of strong El Niño events. Comparisons of these experiments tell us the response only induced directly by the projected reduction of Antarctic sea ice, instead of other influences. Secondly, two atmosphere-only model experiments are conducted based on the Community Atmosphere Model version 5 (CAM5)21, which allow us to understand the role of air-sea coupling and ocean feedbacks in the atmospheric response and Antarctic-tropical Pacific teleconnection induced by the reduction of Antarctic sea ice. Thirdly, we compare the frequency changes in strong El Niño events found from the above time slice coupled model experiments with those from historical and projection simulations of the CESM large ensemble experiments22,23, providing a rough estimation to what extent the changes can be attributed to Antarctic sea-ice loss. Finally, an additional numerical experiment using CESM1.2 is performed to further understand the separate role of greenhouse gas forcing in changing the frequency of strong El Niño.

Results

Change in the frequency of strong El Niño and teleconnection mechanisms

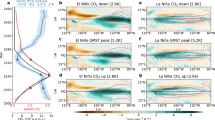

To examine whether the frequency of the simulated strong El Niño events measured by exceeding 1.5 standard deviation can be reshaped by large Antarctic sea-ice loss, we use the classic El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) indices, including Nino3.4 and Nino3 rainfall, with the background warming removed. Here our analyses focus on December-January-February, when ENSO is typically the strongest. We employ a non-parametric bootstrap test24 (see details in “Methods”) to determine if the identified frequency change in strong El Niño events is statistically significant. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1, compared to ANTSIhist, nearly half reduction of Antarctic sea ice cover in ANTSIlate21 (see its annual cycle of sea ice extent in Supplementary Fig. 1) yields ~41% and 39% increase of the occurrence of strong El Niño events based on the Nino3.4 and Nino3 rainfall indices, respectively, which is reflected by the increase of strongest runaround for the sea surface temperature (SST) gradients.

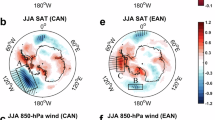

How would large Antarctic sea-ice loss cause increased strong El Niño events in the tropical Pacific? Here we focus on the responses during the developing to mature phase of El Nino (from June to November) to nearly half reduction of Antarctic sea ice (ANTSIlate21). We calculate changes in surface energy budget between ANTSIlate21 and ANTSIhist. In the South Pacific, compared to ANTSIhist, ANTSIlate21 produces a huge increase in the net surface heat flux (NSHF, positive is upward) over the area where sea ice cover is reduced (Supplementary Fig. 2), which is accompanied with a decrease in NSHF to the north—a south-north out of phase pattern. The increased NSHF arises from increased net longwave radiative flux and sensible and latent heat fluxes, which is due to increased absorption of solar radiation there (Supplementary Fig. 2). This leads to strong warming in the lower troposphere in the high-latitude of the South Pacific (largest near the surface and extends to ~250-hPa, Fig. 2A), which greatly reduces meridional temperature gradient around 60°S. The circumpolar westerly is greatly decreased (centered at ~60°S, Fig. 2B), which is responsible for the large decrease in sensible and latent heat fluxes there that leads to the aforementioned decreased NSHF. As a consequence, there are strong positive sea level pressure (SLP) anomalies over the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas (Fig. 2B). This weakens the climatological Amundsen Sea Low, which is a persistent low pressure system located in the southeastern Pacific sector25. The concurring anomalous subsidence centered ~60°S (Fig. 2C) generates an anomalous Rossby wave propagating equatorward into the eastern subtropical and tropical Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 3). The aforementioned decelerated westerly winds in the Southern Pacific also facilitate the equatorward propagation of the anomalous Rossby wave. Contemporaneously, there is a broad anomalous anticyclonic circulation over the subtropical and tropical eastern Pacific (Fig. 2B). On one hand, the anomalous northly/northwesterly winds reduce the coastal upwelling along the west coast of South America, producing warmer SST there. On the other hand, the anomalous westly winds in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific weaken the prevailing trade winds and reduce the equatorial upwelling, reducing the strength of the upper layer meridional ocean circulation (Supplementary Fig. 4A). This flattens west-east gradient of thermocline depth as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 4B, producing warmer SST in the central and eastern Pacific through the wind-evaporation-SST feedback26,27.

(A–C) are coupled model experiments (ANTSIlate21 minus ANTSIhist). (A) 992-hPa air temperature (the lowest model level, °C), (B) near surface winds (m/s) and sea level pressure (hPa), and (C) vertical motion (Pa/s, positive is downward) in the atmosphere averaged over 140W-70W. (D) same as (A), except for atmosphere-only model experiments (ANTSIhist_CAM5 minus ANTSIlate21_CAM5). Gray dots represent statistically significant changes (>95% confidence level).

The air-sea coupling and ocean feedbacks also play an important role in the aforementioned teleconnection mechanisms. Consistent with the coupled model experiments (ANTSIhist and ANTSIlate21), the stand-alone atmospheric model experiments are forced with the same ensemble average of Antarctic sea ice cover from historical and projection simulations (hereafter ANTSIhist_CAM5 and ANTSIlate21_CAM5, see “Methods”). The coupled model configuration (CESM1.2, Fig. 2B) produces the development of a distinct westerly wind anomalies extending from the central to the eastern equatorial Pacific in response to nearly half reduction of Antarctic sea ice. By contrast, it is completely absent in the stand-alone atmospheric model configuration (CAM5, Fig. 2D). The atmosphere-only model configuration produces much weaker and insignificant positive SLP anomalies in the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas. As a result, the weak negative SLP anomaly and associated anomalous anticyclonic circulation are confined to the mid-latitude of the southeastern Pacific, having little influence in the tropical Pacific. This highlights the key role of air-sea coupling and ocean feedbacks in the response of tropical Pacific circulation to Antarctic sea-ice loss.

We know that oceanic heat transport plays an important role in ENSO dynamics28,29, influencing El Niño activity. However, little is known about the impact of large decrease of Antarctic sea ice on the oceanic heat transport in the Pacific. Associated with about half reduction of Antarctic sea ice in ANTSIlate21, there is a large decrease in annual mean poleward heat transport in the entire South Pacific, with the largest decrease at ~10°S (Fig. 3), though it is partly offset by an increase in poleward heat transport in the North Pacific. Overall, less heat is moved away from the tropic Pacific, which converts to an increase in SST in the tropical Pacific. Thus less heat is moved away from the tropic Pacific, which converts to an increase in SST in the tropical Pacific. Such change in the meridional ocean heat transport is also manifested by a large increase in the frequency of largest warm water volumes above the thermocline in the equatorial Pacific (an important ENSO precursor) as compared to ANTSIhist (Supplementary Fig. 5), which is in favor of stronger El Niño.

To clearly determine the contribution of the aforementioned changes in the mean states and feedbacks in the increased strong El Nino induced by nearly half reduction of Antarctic sea ice, we calculate the Bjerknes coupled stability index30, which is based on the recharge-discharge oscillator theory and widely used to assess the ENSO growth rate under different states31,32 (see “Methods”). Here we also focus on the developing to mature phase of El Nino. Figure 4 shows differences in the ENSO growth rate and its five contributing terms. We find that overall, the ENSO growth rate in ANTSIlate21 is enhanced by 0.047 1/year (~7% increase) relative to ANTSIhist, suggesting that sea ice-air and air-sea interactions and ocean feedbacks associated with large Antarctic sea-ice loss encourage stronger El Nino. For the five contributing factors (Fig. 4), a large increase in the thermocline feedback (0.104 1/year) makes the dominant positive contribution, followed by an increase in the Ekman feedback and zonal advective feedbacks, and a minor decrease in mean currents damping (0.015, 0.012, and 0.0001 1/year, respectively), though their positive contributions are partly offset by the enhanced thermodynamic damping (–0.085 1/year).

MA, TD, ZA, TH, and EK (1/year) represent mean currents damping, thermodynamic damping, zonal advective feedback, thermocline feedback, Ekman (upwelling) feedback, respectively. BJ (1/year) is the sum of these five terms. Red bars are ANTSIlate21 minus ANTSIhist, and blue bars are ANTSI4CO2 minus ANTSIhist.

Antarctic sea-ice loss vs. global warming

The El Niño events may be enhanced associated with climate change33,34,35. Using a model democracy approach, a recent study showed that anthropogenic forcings have produced more frequent occurrences of strong El Niño in the post-1960 period36. Under increased greenhouse gases, the upper layer of the tropical Pacific warms faster than the deeper ocean. This increases rainfall and stratification of the upper ocean, making the tropical Pacific more sensitive to wind changes. Increased greenhouse gases also make faster SST warming in the eastern equatorial Pacific relative to the surrounding oceans, which has been linked to a weakening of the walker circulation and an eastward intensification of extratropical teleconnections37. These make ENSO’s self-reinforcing feedback become stronger in a warming climate. Given that Antarctic sea ice extent is projected to decrease dramatically by 2100 by the CMIP6 models, it is important to understand to what extent the identified increase in strong El Niño events can be attributed to Antarctic sea-ice loss. Thus the occurrence of strong El Niño for the period 1980-1999 (hereafter HIST) and 2080–2099 (hereafter RCP85late21) is calculated using the historical simulation and RCP85 projection of the CESM large ensemble experiments22,23. The model employed in the CESM large ensemble experiments is the same as used in the time slice model experiments and the above two time periods are the same as the two time slices defined based on Antarctic sea-ice loss. Thus they can be used to compare the result of the aforementioned time slice experiments. Compared to HIST, RCP85late21 leads to a significant increase in the frequency of strong El Niño events based on the Nino3.4 and Nino3 rainfall indices (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Thus halved Antarctic sea ice in ANTSIlate21 might account for a change in the frequency of strong El Niño that is ~78 and 40% of the size of the change in RCP85late21 of the CESM large ensemble. Such comparisons are derived from changes relative to the baseline of each model experiment. It should be noted that the RCP85 projection simulation is the transient response, whereas Antarctic sea-ice loss experiments are the equilibrium response, the same 20-year used here can only be considered as an approximate steady response based on the large ensemble. From this sense, the contribution of Antarctic sea-ice loss estimated here might be overestimated.

Discussion

In this study, we find that the future Antarctic sea ice change near the end of this century projected by current state-of-art global climate models (nearly half reduction) can induce significantly more frequent strong El Niño events by changing the mean states and feedbacks, which would exert profound effects on global weather and climate. A recent study indicated that Antarctic sea-ice loss can influence Arctic climate. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, nearly half reduction of Antarctic sea ice cover in ANTSIlate 21 produces a significantly intensified the Aleutian Low in the Northern Pacific, which is related to Rossby waves originated from the tropical Pacific and a weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. The enhanced Aleutian Low can lead to positive Pacific Meridional Mode pattern (PMM, an important precursor of ENSO) and strengthened wind-evaporation-sea surface temperature feedback, in favor of increased occurrence of the central Pacific El Nino38,39. A recent study also indicated that warming of tropical Indian Ocean might lead to more frequent central Pacific El Nino events and meridional widening of wind anomalies40. Thus changes in the tropical oceans induced by Antarctic sea-ice loss can initiate tropical and Arctic teleconnections and alter zonal atmospheric circulation over the tropics, further influencing the El Nino response. Here we further examine the differences in the ENSO strength and Antarctic sea ice extent between 2050–2099 (from projection simulation) and between 1950–1999 (from historical simulation) for each ensemble member inside the latest CESM2 large ensemble. Indeed, there is a relationship, that is El Niño becomes stronger as Antarctic sea ice extent decreases (Fig. 6). This provides another support for our finding.

Our analyses also suggest that the ice-free Antarctic of ANTSI4CO2 yields atmospheric and oceanic responses that resemble those of ANTSIlate21 with larger anomalies. Unexpectedly, the ice-free Antarctic of ANTSI4CO2 does not result in a further increase in the occurrence of strong El Niño relative to that of ANTSIlate21 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Instead, compared to ANTSIlate21, it leads to a reduced occurrence of strong El Niño events. To investigate what causes this, we further compare the change of the ENSO growth rate and its five contributing terms using the Bjerknes coupled stability index (Fig. 4). Compared to nearly half reduction of Antarctic sea ice (ANTSIlate21), we find that overall, the ice-free Antarctic (ANTSI4CO2) leads to a decrease in the ENSO growth rate by 0.024 1/year. Such reduction is caused by a substantial increase in the negative contribution from the thermodynamic damping (−0.092 1/year) and a decrease in the positive contribution from the Ekman feedback (-0.01 1/year), which exceed the increase in the positive contribution from the thermocline and zonal advective feedback, and the minor decrease in mean currents damping (0.057, 0.022, and 0.0003 1/year). This indicates that the change in the frequency of strong El Niño events may depend on the magnitude and pattern of Antarctic sea-ice loss, which requires further investigation.

We know that both Antarctic sea-ice loss and increased greenhouse gas contribute to the change of the ENSO frequency, and the global warming experiment (RCP85late21) include both forcings. In order to separate the role of Antarctic sea-ice loss and greenhouse gas forcing, an additional numerical experiment using CESM1.2 is performed, which reflects the equilibrium response of El Niño to fixed atmospheric CO2 at the level of near the end of 21st century without Antarctic sea ice change (named ANTSICO2). Compared to ANTSIhist, ANTSICO2 results in a significant increase in the occurrence of strong El Niño based on the Nino3.4 and Nino3 rainfall indices (Fig. 7 and Table 1). Thus both Antarctic sea-ice loss and increased greenhouse gas forcing play an important role in modulating strong El Niño events.

Although the findings in this work are supported by CESM1.2 (the most widely used coupled model for simulating Earth’s climate), more coordinated experiments (i.e., different coupled climate models, different sea ice constraints), such as the Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project41 for the Antarctic, are needed to further quantify the change of strong El Niño events to the extent of Antarctic sea-ice loss and associated other aspects of climate change. Additionally, this study suggests that we need to determine to what extent changes in climate extremes could be linked to changes in ENSO that might be partially driven by the reduction of Antarctic sea ice cover, which has large implications for the populous mid-latitudes.

Methods

Coupled and uncoupled model experiments and CESM large ensemble

We perform simulations with the CESM1.2 coupled model20. For the atmospheric component, CESM1.2 uses CAM521, which includes improvements for almost all aspects of atmospheric physics compared to CAM4 used to study the influence of Antarctic sea ice change17. For the ocean and sea ice components, CESM1.2 uses the Parallel Ocean Program version 2 (POP2) and the Sea Ice Model version 5 (CICE5), which also include a range of improved physical parameterizations as well as numerical methods compared to the previous POP and CICE used to study the influence of Antarctic sea ice change17. Some studies showed that the CESM1.2 can simulate Antarctic sea ice and ENSO reasonably well42. We also perform atmosphere-only model simulations with CAM521. Here, we run CESM1.2 with a horizontal grid spacing about 1.9° × 2.5° for atmosphere/land models and 1° for ocean/sea ice models and CAM5 with a horizontal resolution of 1.9° × 2.5°.

For easy reference, Table 2 describes all model experiments conducted in this study. First, we conduct three major coupled model experiments. The seasonal cycle of Antarctic sea ice concentration is fixed in the sea ice component of CESM1.2, which is calculated using the ensemble mean of historical and projection CESM simulations from the most recent CMIP6. For the control simulation (ANTSIhist), the climatological Antarctic sea ice cover is specified using the ensemble average of historical simulations during 1980–1999, which approximates the observed sea ice condition during the late 20th century43 (Supplementary Fig. 1). In the two sensitivity simulations, Antarctic sea ice cover is specified using (1) the ensemble average of the projection simulation based on the high end of the shared socio-economic pathway (SSP585) during 2080–2099 (ANTSIlate21) and (2) the average of the last 20 years of the 4 × CO2 simulation that is branched from the 1% per year increase in CO2 run at year 140 and run with CO2 fixed at four times pre-industrial concentration (ANTSI4CO2)23 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Compared to ANTSIhist, both ANTSIlate21 and ANTSI4CO2 lead to a perennial reduction in sea ice extent in the Southern Ocean, with the largest decrease in spring (Supplementary Fig. 7). Spatially, relative to ANTSIhist, ANTSIlate21 shows that sea ice edge is retreated southward dramatically and the total sea ice extent is reduced by about half during the freeze-up period, and the Southern Ocean is nearly ice-free in February and March (Supplementary Fig. 7). For ANTSI4CO2, the entire Antarctic reaches ice-free state for almost all months. The radiative forcings in all experiments are kept fixed at the level of the year 2000. Each experiment is run for 500 years. Ocean dynamics shows clear adjustment to the fixed Antarctic sea-ice loss during the first 220-year integration, i.e., the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation reaches an approximate equilibrium response after 220-year integration (Supplementary Fig. 8). This indicates that longer integration is needed to reach the equilibrium response for the recent coupled model experiment. The simulated Antarctic sea ice cover by the sea ice model component of CESM1.2 resembles the fixed ice cover after ocean dynamics reach the approximate equilibrium, which is also true for Antarctic sea ice thickness. In this study, the simulation for the last 280 years is analyzed to avoid the initial adjustment due to the sudden change of Antarctic sea ice states.

Second, two stand-alone atmospheric model experiments are conducted using CAM5 (named ANTSIhist_CAM5 and ANTSIlate21_CAM5). Same as ANTSIhist and ANTSIlate21, they are forced with the prescribed Antarctic sea ice cover using the ensemble mean of the historical simulation during 1980–1999 (named ANTSIhist_CAM5) and RCP8.5 projection during 2080–2099 (named ANTSIlate21_CAM5), respectively. Each experiment is run for 150 years.

Third, we conduct an additional coupled model experiment using CESM1.2. We fix Antarctic sea ice cover using the ensemble average of historical simulations during 1980–1999, but allowed a 1% per-year increase in atmospheric CO2 for 100 years starting from the level of the year 2000. Then we use the end of this simulation as the initial condition and fix atmospheric CO2 at ~920 ppmv (close to the RCP85 emission scenario near the end of the 21st century) as well as fixed Antarctic sea ice cover based on the historical simulations for the period 1980–1999 (ANTSICO2). Thus the ENSO variability is only influenced by increased greenhouse gas forcing in this experiment. This experiment is run for 100 years.

Last, the CESM large ensemble simulation for the RCP8.5 emission scenario22,23 is also employed to roughly estimate to what extent the projected increase in strong El Niño due to greenhouse warming can be attributed to the large decrease in Antarctic sea ice by comparing the change of the occurrence of strong El Niño events between our time slice simulations and the CESM large ensemble simulations.

Significant test

A non-parametric bootstrap statistical test24 is utilized for significance testing. Firstly, random samples are obtained from the ENSO index (i.e., the zonal SST gradient) of ANTSIhist to generate two new time series. Each has 280 samples, which have different numbers of strong El Niño events. Secondly, the difference in the number of strong El Niño events between the two new time series is calculated. Thirdly, the above bootstrap resampling is repeated 10 thousand times, obtaining 10 thousand differences in the number of strong El Niño events. Finally, the probability density function of 10 thousand differences is generated and the value of the 95th percentile is used as the criteria. If the number of strong El Niño events based on the ENSO index between the sensitivity experiment (i.e., ANTSIlate21) and ANTSIhist exceeds this criteria, it means that the change in strong El Niño events is statistically significant.

ENSO activity index

We use the Bjerknes coupled stability index to measure the ENSO growth rate and its contributing factors30, which is formulated as:

The first two terms on the right-hand side of the equation are mean zonal and meridional currents and thermodynamic dampings, having negative contributions, and the thermodynamic damping is the dominant negative damping effect. The last three terms on the right-hand side of the equation are positive feedbacks, having positive contributions. They are zonal advective, thermocline, Ekman (upwelling) feedbacks, respectively. Here 〈 〉 is a volume average for the Nino3 region and from the surface to the mixed layer. The overbar is the climatology. u, v, w are zonal, meridional, and vertical velocity, respectively, and T is SST. Lx and Ly are zonal and meridional extent of the area. αs, μa, βu, βw, and βh are parameters derived from the recharge oscillator theory (see detailed descriptions in ref. 30).

Data availability

The CESM large ensemble data are available at https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/projects/community-projects/LENS/data-sets.html. The satellite derived Antarctic sea ice data is available at https://noaadata.apps.nsidc.org/NOAA/G02135/.

Code availability

The code of the CESM1.2 and CAM5 models used in this study is available at http://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/cesm1.2. Other codes used here are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Raphael, M., Hobbs, W. & Wainer, I. The effect of Antarctic sea ice on the Southern Hemisphere atmosphere during the southern summer. Clim. Dyn. 36, 1403–1417 (2011).

Smith, D. et al. Atmospheric response to Arctic and Antarctic sea ice: the importance of ocean–atmosphere coupling and the background state. J. Clim. 30, 4547–4565 (2017).

Zhu, Z., Liu, J., Song, M., Wang, S. & Hu, Y. Impacts of Antarctic sea ice, AMV and IPO on extratropical southern hemisphere climate: a modeling study.Front. Earth Sci. 9, 757475 (2021).

Menendez, C., Serafini, V. & LeTreut, H. The effect of sea ice on the transient atmospheric eddies of the Southern Hemisphere. Clim. Dyn. 15, 659–671 (1999).

Kidston, J., Taschetto, A., Thompson, D. & England, M. The influence of Southern Hemisphere sea ice extent on the latitude of the mid-latitude jet stream. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L15804 (2011).

Bader, J., Flugge, M., Kyamsto, N., Mesquita, M. & Voigt, A. Atmospheric winter response to a projected future Antarctic sea ice reduction: a dynamical analysis. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2707–2718 (2013).

England, M., Polvani, L. & Sun, L. Contrasting the Antarctic and Arctic atmospheric responses to projected sea ice loss in the late twenty-first century. J. Clim. 31, 6353–6370 (2018).

Ayres, H. & Screen, A. Multimodel Analysis of the atmospheric response to Antarctic sea ice loss at quadrupled CO2. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9861–9869 (2019).

Abernathey, R. et al. Water-mass transformation by sea ice in the upper branch of the Southern Ocean overturning. Nat. Geosci. 9, 596–601 (2016).

Ferrari, R. et al. Antarctic sea ice control on ocean circulation in present and glacial climates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 8753–8758 (2014).

Marzocchi, A. & Jansen, M. Connecting Antarctic sea ice to deep-ocean circulation in modern and glacial climate simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 6286–6295 (2017).

Parkinson, C. A 40-y record reveals gradual Antarctic sea ice increases followed by decreases at rates far exceeding the rates seen in the Arctic. PNAS 116, 14414–14423 (2019).

Raphael, M. & Handcock, M. A new record minimum for Antarctic sea ice. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 215–216 (2022).

Liu, J., Zhu, Z. & Chen, D. Lowest Antarctic sea ice record broken for the second year in row. Ocean Land Atmos. Res. 2, 0007 (2023).

Roach, L. et al. Antarctic sea ice area in CMIP6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086729 (2020).

Crosta, X. et al. Antarctic sea ice over the past 130000 years—part 1: a review of what proxy records tell us. Clim. Past 18, 1729–1756 (2022).

England, M., Polvani, L., Sun, L. & Deser, C. Tropical climate responses to projected Arctic and Antarctic sea ice loss. Nat. Geosci. 13, 275–281 (2020).

Ayres, H., Screen, J., Blockley, E. & Bracegirdle, T. The coupled atmosphere–ocean response to Antarctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 35, 4665–4685 (2022).

Sun, L., Deser, C., Tomas, R. & Alexander, M. Global coupled climate response to polar sea ice loss: evaluating the effectiveness of different ice‐constraining approaches.Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085788 (2020).

Meehl, G. et al. Climate change projection in CESM1(CAM5) compared to CCSM4. J. Clim. 26, 6287–6308 (2013).

Neale, R. et al. Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 5.0) (No. NCAR/TN-486 + STR), https://doi.org/10.5065/wgtk-4g06 (2012).

Kay, J. et al. The Community Earth System Model (CESM) large ensemble project: a community resource for studying climate change in the presence of internal climate variability. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 1333–1349 (2015).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Austin, P. Bootstrap methods for developing predictive models. Am. Stat. 58, 131–137 (2004).

Raphael, M. The Amundsen sea low: variability, change, and impact on Antarctic climate. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 111–121 (2016).

Xie, S.-P. & Philander, S. A coupled ocean-atmosphere model of relevance to the ITCZ in the eastern Pacific. Tellus 46, 340–350 (1994).

Mahajan, S., Saravanan, R. & Chang, P. The role of the wind–evaporation–sea surface temperature (WES) feedback as a thermodynamic pathway for the equatorward propagation of high-latitude sea Ice–induced cold anomalies. J. Clim. 24, 1350–1361 (2011).

Jin, F. An equatorial ocean recharge paradigm for ENSO. Part I: Conceptual model. J. Atmos. Sci. 54, 811–829 (1997).

Wang, C. & Picaut, J. Understanding ENSO Physics—a Review, in Earth’s Climate: the Ocean-Atmosphere Interaction, Geophysical Monograph Series, Vol. 147 (eds Wang, C., Xie, S.-P., & Carton, J.) 21–48 (AGU, 2004).

Jin, F., Kim, S. & Bejarano, L. A coupled-stability index for ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L23708 (2006).

Lubbecke, J. & McPhaen, M. Assessing the twenty-first-century shift in ENSO variability in terms of the Bjerknes stability index. J. Clim. 27, 2577–2587 (2014).

An, S. & Bong, H. Inter-decadal change in El Nino-Southern Oscillation examined with Bjerknes stability index. Clim. Dyn. 47, 967–979 (2016).

Cai, W. et al. Increasing frequency of extreme El Niño events due to greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 111–116 (2014).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño-Southern oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Cai, W. et al. Anthropogenic impacts on twentieth-century ENSO variability changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 407–418 (2023).

Bayr, T., Dommenget, D., Martin, T. & Power, S. The eastward shift of the Walker Circulation in response to global warming and its relationship to ENSO variability. Clim. Dyn. 43, 2747–2763 (2014).

Amaya, D. The Pacific meridional mode and ENSO: a review. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 5, 296–307 (2019).

Zheng, Y. et al. The role of the Aleutian Low in the relationship between spring Pacific Meridional Mode and following ENSO. J. Clim. 37, 3249–3268 (2024).

Ferster, B., Fedorov, A., Guilyardi, E. & Mignot, J. The effect of Indian Ocean temperature on the Pacific trade winds and ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103230 (2023).

Smith, D. et al. The Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) contribution to CMIP6: investigating the causes and consequences of polar amplification. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1139–1164 (2019).

Planton, Y. et al. Evaluating climate models with the CLIVAR 2020 ENSO metrics package. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 102, E193–E217 (2021).

Fetterer, F. et al. Sea Ice Index, Version 3. Boulder, Colorado USA. National Snow and Ice Data Center, https://doi.org/10.7265/N5K072F8 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0106300) and the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (SML2023SP219).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. Liu conceived the study and wrote the manuscript, Z. Zhu and J. Liu performed and analyzed the model experiments and prepared figures, all authors participated in constructive discussions and helped improve the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Zhu, Z. Projected Antarctic sea ice change contributes to increased occurrence of strong El Niño. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 233 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00789-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00789-w

This article is cited by

-

Attributing climate and weather extremes to Northern Hemisphere sea ice and terrestrial snow: progress, challenges and ways forward

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Changes and impacts of the vulnerable cryosphere

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Drivers of summer Antarctic sea-ice extent at interannual time scale in CMIP6 large ensembles based on information flow

Climate Dynamics (2025)