Abstract

The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) is the principal mode of atmospheric variability over the North Atlantic, modulating the weather and climate of neighboring regions in both winter and summer. While Earth System Models generally project a more positive NAO under 21st century high-emission scenarios, uncertainties persist as to the precise response of the NAO to increased CO2 levels, owing to large internal variability. In this study we investigate the response of the NAO to a wide range of CO2 forcings, from two to eight times the preindustrial values. Analyzing a large sample of present-generation climate models, we find that the NAO likely becomes more positive with increasing CO2 concentrations. Moreover, we find a reduction in NAO variability. This leads to a smaller increase in the likelihood of extremely positive NAO events than would be expected based solely on the shift in the mean. On the other hand, we also find a reduction in extremely negative NAO events, which is attributable to both the shift toward more positive values and the decrease in variance. Finally, our analysis reveals that the distribution of the NAO response at high CO2 forcing is negatively skewed. This fact partially offsets the decrease in extremely positive NAO events associated with reduced variability. Ultimately, our results suggest a greater increase in positive NAO events compared to the decrease in extremely negative NAO events at higher CO2 forcing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) represents the variability in the meridional atmospheric pressure gradient over the North Atlantic1,2, and is tightly coupled to the variability in the latitude of the North Atlantic eddy-driven jet stream3. It is typically thought of as a dipole, with nodes near Iceland and the Azores, although their exact locations change with the seasonal cycle4. Fluctuations in the NAO are linked to changes in average surface wind speed, direction, and moisture transport across the North Atlantic to surrounding regions, including Europe and eastern North America2. In turn, this significantly affects surface temperature and precipitation patterns. On a hemispheric scale, the NAO is closely related to the Northern Annular Mode/Arctic Oscillation, and therefore dominates Northern Hemisphere atmospheric variability5,6.

In winter, the southern node of the NAO is located over the Azores, while the northern node is over Iceland2. During the positive phase of the NAO (NAO+), the Azores high strengthens, and the Icelandic low deepens, increasing the meridional pressure gradient across the North Atlantic. This is associated with a poleward shift in the eddy-driven jet3,7,8, directing the storm track toward northern Europe where it leads to wetter and warmer-than-average conditions with accompanying drier and colder-than-average conditions in southern Europe. Conversely, in the negative phase of the NAO (NAO-), the pressure difference between the Azores high and Icelandic low decreases, which is associated with an equatorward shift of the eddy-driven jet. This phase on average leads to wetter and warmer conditions in southern Europe and drier and colder conditions in northern Europe.

In summer, the NAO has a smaller spatial extent and is shifted poleward with a northwest–southeast tilt2,4,9. Compared with the winter NAO, the southern node of the summer NAO is located further northeast over Britain and Ireland, while the northern node is located further west over Greenland. Similar to the winter NAO, the summer NAO accounts for about one-third of the variance in sea level pressure over the North Atlantic sector10 and is associated with the position and strength of the North Atlantic jet stream and storm tracks11.

Over the historical period the NAO has exhibited pronounced multidecadal variability. From observations alone, one cannot determine whether the increase in greenhouse gas concentration during that period affected the NAO. Significant decadal variability has been observed in both winter and summer NAO during this time12,13: the winter NAO trended positive from the 1950s to the 1990s, but the trend has reversed in recent decades due to the dominance of negative NAO in the late 2000s/early 2010s. The summer NAO has exhibited a negative trend over recent years owing to increased summertime Greenland blocking14, yet most climate models cannot simulate such a trend15. Overall, the low-frequency variability of the NAO complicates the identification of any forced signal in response to increased greenhouse gas concentrations over the historical period.

Another challenge in detecting a forced signal during the historical period is the signal-to-noise problem (or “paradox”) in the North Atlantic: studies have suggested that the NAO response to changes in external forcing, sea surface temperatures, and sea ice in models may be too weak compared to observations13,16. As a result, models simulate significantly weaker NAO multidecadal variability than in reanalysis data for the historical period17,18,19,20,21,22. This weaker NAO variability in models, compared to observations, has been linked to a range of model deficiencies, including in stratosphere-troposphere coupling23 and regime persistence24,25.

Owing to these challenges, there remains considerable model spread regarding the response of the NAO in 21st-century projections. While some models project a more positive NAO in winter26,27,28,29,30,31 and in summer4,31,32, in many cases the projected response lies within the bounds of internal variability27. Only a few models show a more positive future NAO with a signal exceeding their internal variability27.

Furthermore, 21st-century projections under Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) and Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) incorporate not only CO2 increases, but also other anthropogenic forcings (notably aerosols) which confound the signal from CO2. Hence, the precise response of the NAO to increased CO2 forcing in present-generation climate models remains unclear. In addition, the extant studies that have focused on CO2 alone have analyzed historical runs with greenhouse gases only ("hist-GHG”) or abrupt 2 × and 4 × CO2 concentrations. However, due to the signal-to-noise paradox, it may be necessary to apply a larger CO2 forcing to detect a statistically significant response in the NAO.

The goal of this paper, therefore, is to quantify how the winter and summer NAO respond to a wider range of CO2 forcings – 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2 – and to examine that response across many models. We do this by analyzing all available CMIP5 and CMIP6 models at these CO2 forcing levels, supplemented with our own additional experiments using three state-of-the-art models. While the shift in the mean NAO has been linked to changes in extreme events, the changes in higher moments of the distribution (i.e., standard deviation and skewness) have received less attention. Thus, we here report how these higher NAO moments change at high CO2 forcing, and we quantify the accompanying impact on the likelihood of extreme NAO events.

Results

More positive NAO

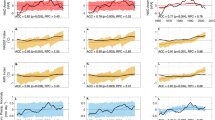

We begin by assessing the preindustrial (PI) climatology of the NAO across all the models, defined as the mean difference between the monthly-mean SLP in the two nodes (see Methods). We find a very large inter-model spread, ranging from around 7 to 31 hPa in winter (95% range 18.5 to 21.1 hPa) and 1 to 11 hPa in summer (95% range 4.7 to 5.8 hPa). Nevertheless, the multi-model-mean NAO at PI lies close to that seen in ERA5, the fifth generation reanalysis from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts33, over 1979–2023. While comparing PI against 1979–2023 is not like-for-like, changes in the NAO during the historical period are minimal17,34, and so a comparison with either the historical period or PI would yield similar results. We choose the 1979–2023 period since the reanalysis is more strongly constrained by observations. For DJF, the multi-model mean is 19.8 hPa, while in ERA5 it is 20.8 hPa (Fig. 1a). For JJA, the PI control mean is 5.3 hPa, and in ERA5 it is 5.7 hPa (Fig. 1b). Hence, despite the very large inter-model spread, the multi-model mean NAO in both seasons closely resembles reanalysis.

Results with preindustrial control runs from models and ERA5 (years 1979–2023) are shown for (a) winter (DJF) and (b) summer (JJA). The response from the model preindustrial values is show in (c) for DJF and (d) for JJA. The empty circles denote individual models (13 models for 2 × CO2, 55 models for 4 × CO2, and 6 models for 8 × CO2). All individual models are listed in Table S1. The error bars show the 95% confidence interval on the mean, obtained by bootstrapping.

Next, we quantify the response of the NAO to increased CO2 as the difference from the PI value. The NAO becomes more positive with increasing CO2 concentrations in most models, both in winter (Fig. 1c) and summer (Fig. 1d). In DJF, the 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2 experiments show a more positive NAO in more than 83% of the models, with multi-model mean increases of 2 hPa, 2.4 hPa, and 3.1 hPa, respectively, corresponding to a 10 to 15% increase from the PI values. Similarly, in JJA, the NAO becomes more positive in more than 79% of the models, with multi-model mean increases of around 1 hPa at 2 × and 4 × CO2, and 1.7 hPa at 8 × CO2. Although the absolute NAO response in JJA is weaker compared to DJF, the percent change from the PI control at JJA is higher: 19% for 2 × and 4 × CO2, and 32% for 8 × CO2. The response is significantly different from zero at the 5% level for all but 8 × CO2 during winter (noting the much smaller number of models for this forcing).

In both winter and summer, the NAO response to CO2 forcing (from 2 × to 8 × CO2) appears to increase monotonically. However, we have fewer models for 2 × CO2 and 8 × CO2 than for 4 × CO2 (see Fig. 1 caption), which prevents us from identifying any statistical significance in the mean behavior of the NAO across the different CO2 forcings from 2 × to 8 × CO2. Although we use a different number of models across the 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2 runs, we emphasize that the results in Fig. 1 (NAO becoming more positive at higher CO2) and the conclusions of the paper remain unchanged when considering only the six models for which all CO2 forcings are available.

Less variable NAO

We now examine the variability of the NAO, defined as the standard deviation of its monthly index (Fig. 2). First, we note that the multi-model spread in NAO standard deviation at PI (Fig. 2a, b) is smaller than the spread in the NAO mean (Fig. 1a, b). Similar to the NAO mean, the multi-model-mean NAO standard deviation lies very close to that obtained from ERA5 (second set of bars in Fig. 2a, b). In DJF, the PI multi-model mean value is 11.2 hPa, while the ERA5 value is 12.4 hPa. In JJA, the PI multi-model mean value is 4.8 hPa, compared to 4.3 hPa in ERA5.

Results with preindustrial control runs from models and ERA5 (years 1979–2023) are shown for (a) DJF and (b) JJA. The response from the model preindustrial values is shown in (c) for DJF and (d) for JJA. The empty circles denote individual models (see Table S1 for a list) and the error bars show the 95% confidence interval on the mean, obtained by bootstrapping.

The NAO multi-model standard deviation under 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2 forcing decreases in both winter and summer (Fig. 2c, d). In DJF, the NAO standard deviation decreases in at least 81% of the models across 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2, with multi-model decreases of 0.3 hPa, 0.9 hPa, and 2.3 hPa, respectively. Similarly, in JJA, the standard deviation decreases in at least 89% of the models, with multi-model decreases of 0.2 hPa, 0.5 hPa, and 0.8 hPa, respectively. The response is significantly different from zero at the 5% level for all forcings in both seasons, although there is a non-significant monotonic response from 2 × to 8 × CO2 due to the small number of models in the 2 × CO2 and 8 × CO2 experiments. This multi-model reduction in the NAO standard deviation contrasts with the increase in the NAO multi-model mean under higher CO2 forcing, and has not (to the best of our knowledge) previously been reported from the NAO perspective, but it has been shown by the reduced variability of the jet35.

Despite the large spread in the NAO mean and standard deviation at PI across the models, we found no relationship between the mean and/or standard deviation of the NAO at PI and its response at 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2, nor between the standard deviation response and the mean response for each forcing (not shown). We also found no relationship between the minority of the models that show a decrease in NAO mean and the models that show an increase in variability (not shown). In addition, showing the standardized NAO index or the change at 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2 as a percent change from the PI value produces the same results as in Fig. 1c, d.

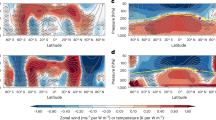

More positive NAO due to both strengthening high and low

Since we compute the NAO index by simply taking the SLP difference between the two nodes (see Methods), we can decompose their respective contributions to the NAO mean response. The southern node (a high-pressure region in the positive phase) is located over the Azores in winter and Britain and Ireland in summer, while the northern node (a low-pressure region in the positive phase) is over Iceland in both seasons in our analysis (see Methods for detailed explanation). When we perform this decomposition, we find that the multi-model mean NAO strengthening in DJF (gray bars in Fig. 3a) is driven roughly equally by increased SLP in the southern node (i.e., a strengthening of the Azores high; red bars) and decreased SLP in the northern node (i.e., a deepening of the Icelandic low; blue bars). This pattern is also evident in the SLP response maps in Fig. 3c–e, where the regions comprising the two nodes of the NAO are delineated in black. The SLP in the southern node increases monotonically across the 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2 forcing levels. However, while the SLP in the northern node decreases at 2 × CO2, at 8 × CO2 the pattern is mixed, with half of the box showing lower pressure (blue) and half higher pressure (red), indicating that the decrease in SLP in the Icelandic region is not as pronounced as the increase in the Azores region. This is also reflected in the decomposition shown in Fig. 3a, where the blue bar at 8 × CO2 illustrates the weaker response in the northern node.

The mean NAO index (gray) is decomposed to contributions from the southern ("high''; red) and northern ("low''; blue) nodes for (a) DJF and (b) JJA. The bars show the multi model means, and error bars are 95% range from bootstrapping the model mean. The maps show the multi-model mean SLP response for DJF and JJA.

In JJA, the NAO mean becomes more positive primarily due to the contribution from increased SLP in the southern node at 2 × and 4 × CO2, and decreased SLP in the northern node at 8 × CO2 levels. The sea-level pressure maps corroborate this: at 2 × CO2, there is a predominantly positive response over Britain and Ireland (Fig. 3f), but by 8 × CO2 (Fig. 3h), the Icelandic low shows a strong negative response, while the SLP in the southern node over Britain and Ireland displays a mixed pattern of increases and decreases. This is due to a strongly negative SLP response over Europe during summer, which is likely a thermodynamic response to the extremely high temperatures at this forcing.

Less variable NAO

Similarly to the NAO mean, we decompose the contributions to the change in the NAO standard deviation from each node (Fig. 4a, b). In DJF, the decrease in the NAO standard deviation (gray bars, Fig. 4a) is roughly evenly split between reductions in the southern and northern nodes. Maps of the difference in SLP standard deviation from PI support this finding, showing that variability decreases in the vicinity of both the Azores high and the Icelandic low as CO2 increases (Fig. 4c–e). Although the covariance response (green) can also play a role in DJF, its impact is unclear because the response of the covariance is not independent of changes in the variance of the two nodes.

The response in the standard deviation of the NAO index (gray) is decomposed to contributions from the southern ("high''; red) and northern ("low''; blue) nodes for (a) DJF and (b) JJA, and green bars show the covariance term. The bars show the multi-model means, and error bars are 95% range from bootstrapping the model mean. The maps show the multi-model mean response for DJF and JJA.

In JJA, the decrease in NAO standard deviation is primarily driven by decreased variability in the vicinity of Britain and Ireland, coincident with the southern node (Fig. 4b, f–h). At 8 × CO2, the response in the northern node is negligible, due to the influence of increased variability north of Iceland over the Greenland Sea (Fig. 4h).

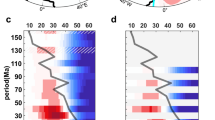

More extreme NAO+ and less extreme NAO- events

Since our findings indicate that the NAO will become more positive and less variable under higher CO2 forcing, we next investigate how this will affect extreme NAO events. We define extreme NAO events as those occurring with a frequency of one month per decade and calculate how these events will change at 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2. Additionally, we decompose the changes in extreme events into contributions from (1) the shift in the NAO mean, (2) changes in the NAO standard deviation, and (3) higher-order statistical moments (e.g., skewness), as the NAO distribution is non-Gaussian (see Methods).

Starting with extremely negative NAO events (NAO-), we find a reduction in these events in both winter and summer (gray bars, Fig. 5a). The baseline number of extreme NAO- events at PI control is 1 per decade, so the simulated changes indicate a reduction of 39% in winter and 42% in summer. Both the increase in the NAO mean (red) and the decrease in the NAO standard deviation (blue) contribute to this reduction. The increase in the NAO mean shifts the NAO distribution to the “right,” (i.e., in the positive direction) thereby reducing the frequency of NAO- events (see multi-model probability density function in Fig. 6). Additionally, the decrease in standard deviation “shrinks” the width of the distribution (Fig. 6), further reducing the number of extreme NAO- events. The residual (green), which accounts for changes in higher-order moments such as skewness, has a negligible impact on extreme NAO-event changes in DJF and acts to decrease NAO- events in JJA.

Extreme (a) NAO- and (b) NAO+ events for DJF (first set of bars) and JJA (second set of bars). The total change (gray) is decomposed into contributions from changes in the NAO mean (red), standard deviation (blue) and the non-normality of the distribution (green). Extreme events are defined as those occurring once per decade.

Consistent with the results presented thus far, we find that the number of extremely positive NAO events (NAO+) increases at 4 × CO2 (gray bars, Fig. 5b). Relative to PI, we find a 56% increase in winter and a 49% increase in summer. The more positive NAO mean state shifts the distribution to the right, thereby increasing the number of extreme NAO+ events (red bars). Concurrently, the decrease in standard deviation reduces the “spread” of the NAO distribution, which would (in the absence of other changes) decrease the number of extreme NAO+ events (blue bars). However, contributions from third-order moments (skewness) and higher-order moments also play a role in increasing the number of NAO+ events (green bars). In fact, after accounting for the opposing contributions of the NAO mean and standard deviation, a considerable amount of the increase in NAO+ events can be attributed to changes in the third and higher-order moments of the distribution. The residual is particularly significant in explaining the increase in extreme NAO+ events, largely due to the negative skewness (a “tilt to the right”) of the NAO distribution at 4 × CO2.

Based on the projected changes in the NAO mean and standard deviation alone, we would expect a larger magnitude decrease in extreme NAO- events compared to the increase in extreme NAO+ events at 4 × CO2. However, we find a similar magnitude increase in the frequency of extreme NAO+ events as the decrease in NAO- events. This seemingly counterintuitive result arises from the non-normality nature of the NAO distribution (shown in Fig. 6) and the influence of changes in higher-order moments. While the shift in the NAO mean (Fig. 1) and the decrease in standard deviation (Fig. 2) contribute to the overall changes in extreme events, it is the changes in skewness and higher-order moments that ultimately lead to a similar increase in extreme NAO+ events as the decrease in extreme NAO- events. This highlights the importance of considering the entire NAO distribution, including its higher-order moments, when evaluating changes in the frequency of extreme NAO events under increased CO2. Lastly, our results also point to the limitation of relying on a single NAO index to capture diverse jet variability, which may be better represented by a broader range of indices or metrics.

Discussion and Conclusion

We have examined the response of the winter and summer North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) using earth system model experiments with abrupt 2 × , 4 × , and 8 × CO2 forcings. While studies with large ensembles have previously reported a more positive NAO in 21st-century projections, our study unambiguously isolates the response to CO2 forcing, confirming that it causes a shift toward a more positive NAO in most models. Additionally, we find that the NAO becomes less variable under increased CO2 forcing. The implications of a more positive but less variable NAO on extreme NAO+ events are nuanced: while a more positive NAO increases the frequency of extreme NAO+ events, the reduced variability tends to decrease these events. At the same time, both the changes in mean state and variability contribute to a decrease in extreme NAO- events. Notably, changes in skewness further increase the number of extreme NAO+ events, leading to a greater rise in NAO+ events compared to the decrease in NAO- events in both summer and winter.

The mechanisms driving the mean NAO response to increased CO2 levels, and the associated response of the North Atlantic jets and storm tracks, are determined by the competing effects of the lower and upper tropospheric meridional temperature gradients in the North Atlantic36,37,38,39,40. As greenhouse gas concentrations rise, Arctic amplification weakens the lower tropospheric meridional temperature gradient, causing the jets to shift equatorward, which leads to a more negative NAO39,40,41. At the same time, enhanced warming in the tropical upper troposphere (in addition to the increased horizontal temperature gradient arising from stratospheric cooling) strengthens the upper tropospheric meridional temperature gradient, pushing midlatitude jets poleward, resulting in a more positive NAO42. Previous studies43 have linked the NAO response to these mechanisms, showing that stronger Arctic amplification shifts the mid-latitude jets and the storm tracks equatorward, resulting in a more negative NAO39,44. Another potential mechanism affecting the NAO in a warmer world is the role of cloud radiative effects45,46, which influence meridional temperature gradients, thereby altering mid-latitude circulation and the NAO. However, considerable disagreement remains as to whether the cloud radiative effects act primarily in the shortwave or longwave range, and only a few models have been used to study the role of clouds in the midlatitude jet47.

Since the NAO index describes the variability of the Atlantic jet35, the response of the mean NAO index to CO2 can be interpreted as a mean shift of the Atlantic jet, while the response in the standard deviation of the NAO index reflects changes in its variability. Multi-model CMIP studies project that by the end of the 21st century, the mean position of the North Atlantic jet will shift poleward35,48. These studies also indicate a decrease in the variability of the North Atlantic jet in 21st-century projections, suggesting a reduction in the standard deviation of the NAO index, which is in agreement with our findings. Specifically, the decreased variability in both nodes of the winter NAO (as illustrated in Fig. 4c–h) is broadly consistent with an increase in the frequency of the “central” jet regime under SSP5-8.549. Therefore, part or possibly most of the decrease in standard deviation in the high and low-pressure nodes can be interpreted as reduced variability of the North Atlantic jet7,8.

We find an increase in extreme NAO+ events and a decrease in NAO- events under increased CO2 forcing. However, attributing these responses solely to changes in the NAO mean and standard deviation is insufficient, as the distribution of NAO events is non-Gaussian. Changes in the higher-order moments, particularly skewness, play a crucial role. The skewness in the underlying NAO has been hypothesized to be related to eddy feedback asymmetries and/or the presence of distinct circulation regimes50,51,52. Thus, changes in skewness under CO2 forcing could reflect changes to such feedbacks/regimes, though a detailed investigation of this is beyond the scope of our work here. Furthermore, the identified changes in extreme NAO events are sensitive to how “extreme” is defined. When defined based on fixed frequency (1 month per decade), we find a larger increase in NAO+ events compared to the decrease in extreme NAO- events (Fig. 5). On the other hand, when defined using a fixed threshold of 1.5 σ, the decrease in extreme NAO- events is larger (Fig. S5).

One caveat to studying the response of the NAO to increased CO2 concentrations is the signal-to-noise paradox13,16. To address this, we applied higher CO2 forcing (8 × CO2) to obtain a better signal-to-noise ratio in the NAO response. We found a similar response in the NAO mean (Fig. 1b, c), variability (Fig. 2b, c), and the North Atlantic sea-level pressure mean (Fig. 3) and variability (Fig. 4) across the 4 × CO2 and 8 × CO2 experiments. However, whether models simulate the correct NAO response to this high CO2 forcing – given the signal-to-noise issue – remains an open question. In addition, due to the limited number of models available for the 2 × CO2 and 8 × CO2 simulations, we were unable to establish statistically significant evidence of a linear response in the NAO mean and variability to CO2 forcing, as suggested by previous studies53,54. We hope future research will help address these issues. Furthermore, while we have solely analyzed monthly-mean data, analyzing daily data from similar high-forcing experiments would enable a quantification of changes to circulation regimes (including jet latitude regimes) and their persistence. Lastly, although most models agree on the NAO response to increased CO2 concentrations, the actual physical climate system may exhibit different behavior to a given CO2 forcing than suggested by our conclusions.

Overall, our findings underscore the need to consider the full distribution of the NAO, not just the mean value, and the sensitivity to the definition of extreme events when assessing the potential impacts of NAO on regional climate and extreme weather events. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the dynamical mechanisms underlying the projected changes in NAO variability, including the inter-model differences, and to explore the potential consequences for regional climates and societies.

Methods

Various methods exist for defining the NAO. In this study, we define the NAO using simple two-box indices. In models, these are easier to interpret than EOFs, which can confound statistical and physical differences6. For the winter NAO, we take the monthly-mean SLP during December-January-February and compute the difference between the southern box over the Azores (35∘N-40∘N and 30∘W-20∘W), and the northern box over Iceland (60∘-70∘N and 25∘-10∘W). This is the traditional definition of the wintertime NAO1,2,30. For the summer NAO, we take the SLP difference in June-July-August from a southern box over Britain and Ireland (45∘N-55∘N and 25∘W-10∘E,10) and a northern box over Iceland, the same as in winter (60∘-70∘N and 25∘-10∘W). Note that we are using a slightly different definition of the northern node than Dunstone et al.10 to avoid issues with the high terrain of Greenland (and Greenland ice melt) influencing model SLP output. Nonetheless, we obtain similar results if we use the same northern node as in Dunstone et al.10. In 1979–2023 ERA5 data, the temporal correlation between these two summer NAO definitions is 0.91, further evidencing their close correspondence.

The NAO as a two-box index is consistent with the leading empirical orthogonal function (EOF1) of SLP obtained from the models. To show that the two box index is consistent with EOF1, we regress the SLP with the NAO 2-box index (Fig. S1a, c) and find that it closely resembles the EOF1 (Fig. S1b, d) with a pattern correlation of 0.99 for DJF and 0.98 for JJA, indicating that the NAO 2-box index correlates well with the leading pattern of SLP variability. Furthermore, we show the SLP regression onto the NAO 2-box index between models and reanalysis (Fig. S2), and for each model at PI control for DJF (Fig. S3) and JJA (Fig. S4).

To quantify the response of the NAO to CO2 forcings, we utilize our own model runs with CESM1-LE and GISS-E2.1-G which have been previously documented55,56,57, and the GFDL-FLOR model58. In addition, we use 46 CMIP6 models, and 12 models from the LongRunMIP archive59. In total, we use 61 models, listed in Table S1.

We utilize abrupt 2 × CO2, 4 × CO2, and 8 × CO2 from a PI control runs. These abrupt-CO2 runs are usually run for 150 years (except the LongRunMIP models). To allow time for the system to adjust, we analyze years 51 to 150, and compare that to 150 years of the preindustrial control run. Note that not all experiments are available for all models; this is also shown in Table S1.

We define extreme events at PI control as events occurring once per decade and calculate the change at 4 × CO2 in Fig. 5. In the multi-model means at PI control, the NAO- events that occur once a decade appear at 1.99σ and 1.95σ in DJF and JJA, respectively. Similarly for the NAO+, the extreme events events are at 1.68σ and 1.62σ in DJF and JJA, respectively. We do the same for the 4 × CO2 run, using μ and σ from the PI control run, and then take the difference between both to find the total response at 4 × CO2 (gray in Fig. 5). To attribute the total response at 4 × CO2 to changes in μ (red in Fig. 5), we compute the extreme NAO+ and NAO- events with using μ from piControl and μ from 4 × CO2 and take the difference, which approximates how much of the change in NAO+ and NAO- events is due to the change in the mean NAO state. Then, to attribute the total response due to σ (blue in Fig. 5), we compute the extreme NAO+ and NAO- events with using σ from piControl and σ from 4 × CO2 and take the difference, which again approximates how much of the total change of NAO extreme events is due to the change in NAO standard deviation. If the distribution of NAO events was Gaussian (with the third moment – skewness – and higher moments equal zero), then the change in μ and σ (red and blue in Fig. 5) would have summed to the total change (gray in Fig. 5). However, the distribution is not perfectly Gaussian, so we have a residual (green in Fig. 5) which is computed as difference between total Δ and the sum of due to Δμ and Δσ. This residual represents the contribution from the third (skewness) and higher order moments of the distribution to the change in extreme events.

In Fig. S5, we repeat the calculations for extreme NAO events shown in Fig. 5 but instead define extreme events as those exceeding 1.5σ.

Open Research Section

The CESM1-LE model data can be obtained at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5725084 and GISS-E2.1-G model data at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3901624. ERA5 reanalysis data are available from https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7.

Data availability

The experiments from CESM1-LE and GISS-E2.1-G were previously analyzed55,56,57,60 and can be obtained at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5725084 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3901624, respectively.

References

Hurrell, J. W. Decadal trends in the north atlantic oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 269, 676–679 (1995).

Hurrell, J. W., Kushnir, Y., Ottersen, G. & Visbeck, M.An Overview of the North Atlantic Oscillation, 1–35 (American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2003).

Woollings, T., Hannachi, A. & Hoskins, B. Variability of the north atlantic eddy-driven jet stream. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 136, 856–868 (2010).

Folland, C. K. et al. The summer north atlantic oscillation: past, present, and future. J. Clim. 22, 1082–1103 (2009).

Feldstein, S. B. & Franzke, C. Are the north atlantic oscillation and the northern annular mode distinguishable? J. Atmos. Sci. 63, 2915–2930 (2006).

Lee, S. H. & Polvani, L. M. Large model biases in the pacific centre of the northern annular mode due to exaggerated variability of the aleutian low. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society (2024).

Oudar, T., Cattiaux, J. & Douville, H. Drivers of the northern extratropical eddy-driven jet change in cmip5 and cmip6 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086695 (2020).

Peings, Y., Cattiaux, J., Vavrus, S. J. & Magnusdottir, G. Projected squeezing of the wintertime north-atlantic jet. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 074016 (2018).

Linderholm, H. W. & Folland, C. K. Summer north atlantic oscillation (snao) variability on decadal to palaeoclimate time scales. Glob. Chang. Mag. 25, 57–60 (2017).

Dunstone, N. et al. Skilful predictions of the summer north atlantic oscillation. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 409 (2023).

Dong, B., Sutton, R. T., Woollings, T. & Hodges, K. Variability of the north atlantic summer storm track: mechanisms and impacts on european climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 034037 (2013).

Gulev, S. et al. Changing state of the climate system. In Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, book section 2, 287–422 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2021). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Chapter02.pdf.

Eyring, V. et al. Human influence on the climate system. In Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, book section 3, 423–551 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2021). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Chapter03.pdf.

Preece, J. R. et al. Summer atmospheric circulation over greenland in response to arctic amplification and diminished spring snow cover. Nat. Commun. 14, 3759 (2023).

Maddison, J. W., Catto, J. L., Hanna, E., Luu, L. N. & Screen, J. A. Missing increase in summer greenland blocking in climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108505 (2024).

Scaife, A. A. & Smith, D. A signal-to-noise paradox in climate science. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 28 (2018).

Blackport, R. & Fyfe, J. C. Climate models fail to capture strengthening wintertime north atlantic jet and impacts on europe. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn3112 (2022).

Bonnet, R., McKenna, C. M. & Maycock, A. C. Model spread in multidecadal north atlantic oscillation variability connected to stratosphere–troposphere coupling. Weather Clim. Dyn. 5, 913–926 (2024).

Bracegirdle, T. J. Early-to-late winter 20th century north atlantic multidecadal atmospheric variability in observations, cmip5 and cmip6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098212 (2022).

Kravtsov, S. Pronounced differences between observed and cmip5-simulated multidecadal climate variability in the twentieth century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 5749–5757 (2017).

Wang, X., Li, J., Sun, C. & Liu, T. Nao and its relationship with the northern hemisphere mean surface temperature in cmip5 simulations. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 122, 4202–4227 (2017).

Eade, R., Stephenson, D. B., Scaife, A. A. & Smith, D. M. Quantifying the rarity of extreme multi-decadal trends: how unusual was the late twentieth century trend in the north atlantic oscillation? Clim. Dyn. 58, 1555–1568 (2022).

O’Reilly, C. H., Weisheimer, A., Woollings, T., Gray, L. J. & MacLeod, D. The importance of stratospheric initial conditions for winter north atlantic oscillation predictability and implications for the signal-to-noise paradox. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 145, 131–146 (2019).

Strommen, K. & Palmer, T. N. Signal and noise in regime systems: A hypothesis on the predictability of the north atlantic oscillation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 145, 147–163 (2019).

Zhang, W. & Kirtman, B. Understanding the signal-to-noise paradox with a simple markov model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 13308–13317 (2019).

Fabiano, F., Meccia, V. L., Davini, P., Ghinassi, P. & Corti, S. A regime view of future atmospheric circulation changes in northern mid-latitudes. Weather Clim. Dyn. 2, 163–180 (2021).

McKenna, C. M. & Maycock, A. C. Sources of uncertainty in multimodel large ensemble projections of the winter north atlantic oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093258 (2021).

McKenna, C. M. & Maycock, A. C. The role of the north atlantic oscillation for projections of winter mean precipitation in europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099083 (2022).

Bacer, S., Christoudias, T. & Pozzer, A. Projection of north atlantic oscillation and its effect on tracer transport. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 15581–15592 (2016).

Stephenson, D. et al. North atlantic oscillation response to transient greenhouse gas forcing and the impact on european winter climate: a cmip2 multi-model assessment. Clim. Dyn. 27, 401–420 (2006).

Gillett, N. P. & Fyfe, J. C. Annular mode changes in the cmip5 simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1189–1193 (2013).

Barcikowska, M. J. et al. Changes in the future summer mediterranean climate: contribution of teleconnections and local factors. Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 161–181 (2020).

Hersbach, H. et al. The era5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Outten, S. & Davy, R. Changes in the north atlantic oscillation over the 20th century. Weather Clim. Dyn. 5, 753–762 (2024).

Barnes, E. A. & Polvani, L. Response of the midlatitude jets, and of their variability, to increased greenhouse gases in the cmip5 models. J. Clim. 26, 7117 – 7135 (2013).

Lee, S. H., Williams, P. D. & Frame, T. H. A. Increased shear in the north atlantic upper-level jet stream over the past four decades. Nature 572, 639–642 (2019).

Shaw, T. et al. Storm track processes and the opposing influences of climate change. Nat. Geosci. 9, 656–664 (2016).

Harvey, B. J., Shaffrey, L. C. & Woollings, T. J. Equator-to-pole temperature differences and the extra-tropical storm track responses of the cmip5 climate models. Clim. Dyn. 43, 1171–1182 (2014).

Screen, J. A. et al. Consistency and discrepancy in the atmospheric response toarctic sea-ice loss across climate models. Nat. Geosci. 11, 155–163 (2018).

Lee, J.-Y. et al. Future global climate: Scenario-based projections and near-term information. In Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, book section 4, 553–672 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2021). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Chapter04.pdf.

Forster, P. et al. The earth’s energy budget, climate feedbacks, and climate sensitivity. In Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, book section 7, 923–1054 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2021). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Chapter07.pdf.

Shaw, T. A. Mechanisms of future predicted changes in the zonal mean mid-latitude circulation. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 5, 345–357 (2019).

Oudar, T. et al. Respective roles of direct ghg radiative forcing and induced arctic sea ice loss on the northern hemisphere atmospheric circulation. Clim. Dyn. 49, 3693–3713 (2017).

McKenna, C. M., Bracegirdle, T. J., Shuckburgh, E. F., Haynes, P. H. & Joshi, M. M. Arctic sea ice loss in different regions leads to contrasting northern hemisphere impacts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 945–954 (2018).

Voigt, A., Albern, N. & Papavasileiou, G. The atmospheric pathway of the cloud-radiative impact on the circulation response to global warming: Important and uncertain. J. Clim. 32, 3051 – 3067 (2019).

Ceppi, P. & Hartmann, D. L. Clouds and the atmospheric circulation response to warming. J. Clim. 29, 783 – 799 (2016).

Voigt, A. et al. Clouds, radiation, and atmospheric circulation in the present-day climate and under climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 12, e694 (2021).

Iqbal, W., Leung, W.-N. & Hannachi, A. Analysis of the variability of the north atlantic eddy-driven jet stream in cmip5. Clim. Dyn. 51, 235–247 (2018).

Dorrington, J., Strommen, K., Fabiano, F. & Molteni, F. Cmip6 models trend toward less persistent european blocking regimes in a warming climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100811 (2022).

Barnes, E. A. & Hartmann, D. L. Dynamical feedbacks and the persistence of the nao. J. Atmos. Sci. 67, 851 – 865 (2010).

Woollings, T., Hannachi, A., Hoskins, B. & Turner, A. A regime view of the north atlantic oscillation and its response to anthropogenic forcing. J. Clim. 23, 1291 – 1307 (2010).

Zhao, S., Ren, H.-L., Zhou, F., Scaife, A. A. & Nie, Y. Phase asymmetry in synoptic eddy feedbacks on the negatively-skewed winter nao. Atmos. Res. 288, 106725 (2023).

Gillett, N. P. et al. How linear is the arctic oscillation response to greenhouse gases? J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 107, ACL–1 (2002).

Gillett, N. P., Graf, H. F. & Osborn, T. J. Climate Change and the North Atlantic Oscillation, 193–209 (American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2003). https://doi.org/10.1029/134GM09 (2003).

Mitevski, I., Orbe, C., Chemke, R., Nazarenko, L. & Polvani, L. M. Non-monotonic response of the climate system to abrupt co2 forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090861 (2021).

Mitevski, I., Polvani, L. M. & Orbe, C. Asymmetric warming/cooling response to co2 increase/decrease mainly due to non-logarithmic forcing, not feedbacks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097133 (2022).

Mitevski, I., Dong, Y., Polvani, L. M., Rugenstein, M. & Orbe, C. Non-monotonic feedback dependence under abrupt co2 forcing due to a north atlantic pattern effect. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103617 (2023).

Vecchi, G. A. et al. On the seasonal forecasting of regional tropical cyclone activity. J. Clim. 27, 7994 – 8016 (2014).

Rugenstein, M. et al. Longrunmip: Motivation and design for a large collection of millennial-length aogcm simulations. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 2551 – 2570 (2019).

Mitevski, I., Chemke, R., Orbe, C. & Polvani, L. M. Southern hemisphere winter storm tracks respond differently to low and high co2 forcings. J. Clim. 37, 5355 – 5372 (2024).

Acknowledgements

IM is supported by a Harry Hess postdoctoral fellowship from Princeton Geosciences. The work of LMP is supported, in part, by a grant from the US National Science Foundation to Columbia University. We thank the high-performance computing resources provided by NASA’s Advanced Supercomputing (NAS) Division and the NASA Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS). Part of the computing and data storage resources, including the Cheyenne supercomputer (https://doi.org/10.5065/D6RX99HX), were provided by the Computational and Information Systems Laboratory at National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.M. conducted the analyses and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. S.H.L. created the ERA5 figures, participated in all stages of the analysis, and provided essential revisions to the manuscript draft. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript, interpreted the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitevski, I., Lee, S.H., Vecchi, G. et al. More positive and less variable North Atlantic Oscillation at high CO2 forcing. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 171 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01051-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01051-7

This article is cited by

-

Anthropogenic climate change leads to a pronounced reorganisation of wintertime North Atlantic atmospheric circulation regimes

Communications Earth & Environment (2026)

-

Mediterranean precipitation variability is driven by complex atmospheric mechanisms beyond the North Atlantic Oscillation

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Increasing central and northern European summer heatwave intensity due to forced changes in internal variability

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Atmospheric circulation conditions regulating long- and short-range impacts of PM2.5 associated with North American wildfires

Science China Earth Sciences (2025)