Abstract

The Asian tropopause aerosol layer (ATAL) causes significant regional radiative forcing which may influence the tropospheric weather and climate. Our analysis reveals that the intensified ATAL weakens the South Asian High (SAH) and the South Asian Monsoon. The ATAL leads to increases in diabatic heating in the upper troposphere in the SAH region, induces an anomalous upward flow which decreases the adiabatic heating and causes cooling anomalies in the upper troposphere in the SAH region, and ultimately weakens the SAH (diabatic heating mechanism). However, responses of the SAH to the ATAL are nonlinear. Model results indicate that when the ATAL intensity is doubled, a temperature inversion occurs in the upper troposphere which tends to stabilize the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere (UTLS) and prevent the upward moisture transport (static stability mechanism). The reduced latent heat release induces middle and upper tropospheric cooling in the SAH region, thereby weakens the SAH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Asian summer monsoon (ASM) region is densely populated with rapid economic development in recent decades. Affected by increased biomass burning, fossil fuel combustion, and industrial production processes, this area has emitted a large amount of pollutants, making it one of the most significant pollution source regions globally, and thus attracts widespread attention1,2,3. During the ASM season, surface pollutants over South and East Asia can be rapidly transported upward and trapped within the UTLS region due to the influence of the Asian summer monsoon anticyclone (ASMA) and the frequent deep convection4,5,6,7, which induces a high concentration of aerosols in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere (UTLS) region8,9,10. Vernier et al.11 discovered this high aerosol layer at the altitude of 13–18 km and named it as Asian tropopause aerosol layer (ATAL), which spans vast regions from the eastern Mediterranean to western China during the summer from 2006 to 2009 based on the CALIPSO satellite data. Yu et al.12 confirmed the satellite observations by using balloon data in Kunming and reproduced the existence of the ATAL in the numeric simulations. ATAL causes a significant regional radiative forcing and is important for the aerosol loading of the global stratosphere, which may significantly influence the stratospheric chemistry and tropospheric weather and climate12,13,14,15,16,17,18.

The formation, composition, and impact factors of the ATAL have been widely investigated. Frequent deep convection during the ASM season could take surface pollutants such as black carbon and organic carbon to the upper troposphere, which could be trapped within the ASMA19,20,21,22. Wu et al.23 revealed that the deep convection over the ASM region dominates the variability of the ATAL with a contribution of 62.7%. Bossolasco et al.24 reported that dust is a major contributor to the aerosol burden in the ATAL, followed by sulfate aerosols, which account for 40% of the aerosol burden in the ATAL excluding dust. Fairlie et al.25 suggested that anthropogenic emissions from the regions of China and the Indian subcontinent play a dominant role in influencing sulfate aerosol concentrations in the ATAL. The South Asian High (SAH), an important semi-permanent anticyclonic circulation system in the UTLS region during the Northern Hemisphere summer26, is also regarded as a critical impact factor of the ATAL variations. Studies have suggested that the intensity of the SAH and its quasi-biweekly oscillations can influence the concentration and distribution of aerosols in the ATAL27. Yang et al.22 analyzed the variation of tropospheric constituents within the anticyclone under the Tibetan Plateau (TP) and the Iranian Plateau (IP) modes of the SAH, and found that the concentration of tropospheric constituents (such as CO, H2O) is higher under the TP mode. Though numerous studies focused on variations of the ATAL, the climate impact of the ATAL is still not well understood.

The variation of the SAH affects the atmospheric circulation pattern of the entire Northern Hemisphere, and influences the weather and climate of the ASM region through interactions with mid- and low-level systems such as the Western Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH)28,29,30. Previous studies have shown that the SAH is closely related to the onset and rainfall of the ASM31,32. When the SAH strengthens and extends eastward, the WPSH strengthens and extends westward, leading to the weakened East Asian monsoon and an anomalous increase in precipitation, including extreme precipitation, in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River33,34,35. Hence, understanding the variations of the SAH is essential for the prediction of the weather and climate over East Asia. In the past few decades, the ATAL has undergone significant changes36, and effects of the ATAL on the atmospheric radiation budget are well investigated37. The intensified ATAL could exert a regional radiative forcing of −0.1 W/m2 at the top of the atmosphere from 1996 to 201338. Meanwhile, the changes in the stratospheric aerosol could lead to changes in the lower stratosphere. Peng et al.39 found that the significantly increased lower stratospheric aerosols in the tropics could accelerate the Brewer-Dobson circulation. Currently, it remains unclear what the impact of the ATAL is on the SAH and its underlying mechanism is worthy of investigation.

In this study, we focus on the impacts of the ATAL on the SAH in boreal summer. Using composite analysis and CESM model simulations, we found that an increase in the ATAL leads to a weakening of the SAH. Furthermore, CESM model simulations reveal that the response of the SAH to the enhancement of the ATAL is nonlinear.

Results

Impact of the ATAL on the SAH

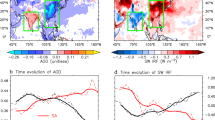

Figure 1a displays the horizontal distribution of geopotential height differences from the MERRA-2 dataset (hereafter, referred as anomalies) at 150 hPa in the ATAL region (15°N-45°N, 15°E-120°E) between the high and low ATAL years during the summer. Note that there is a significant decrease in geopotential height in the south of 30°N of the ATAL region, with negative anomalies reaching up to 15 gpm. The spatial coverage of the SAH represented by the red and blue solid lines in Fig. 1a indicates that the spatial coverage of the SAH is shrunken in the anomalously high ATAL years. Figure 1c–e respectively show the probability density functions (PDFs) of the ATAL intensity index, area index, and eastward extension index in the high and low ATAL years. In the high ATAL years (red lines), the PDFs of three indices of the SAH shift to smaller values compared to those in the low ATAL years (blue lines). The mean values of these three indices are smaller in the high ATAL years. Previous studies have indicated that anthropogenic aerosols have a significant impact on the SAH40,41. Note that the difference in aerosol loading averaged within the ATAL between the high and low ATAL years is 0.54 ppbm. The background mean aerosol loading of the ATAL in the low ATAL years is 1.37 ppbm. The proportion of the ATAL intensity increase is calculated as the aerosol loading difference between the high ATAL years and low ATAL years, divided by the mean aerosol loading in the low ATAL years, which is approximately 0.5 times. This implies that an enhancement of 0.54 ppbm in the aerosol loading of the ATAL could result in a 17% weakening in the intensity of the SAH, a 9% decrease in the area of the SAH, and an eastward shift of the SAH by about 5°. The proportion of intensity reduction (area decrease) is calculated based on the difference between the intensity (area) index of the SAH in low ATAL years and high ATAL years, divided by the intensity (area) index of the SAH in the low ATAL years. Differences in three indices of the SAH are shown in Fig. 1b, with all these indices being negative (statistically significant at the 95% confidence level), further confirming that the SAH is weakened and contracted in the high ATAL years as shown in Fig. 1a.

a Geopotential height differences at 150 hPa in JJA (June–August) between the high and low ATAL years (high ATAL years - low ATAL years) from the MERRA-2 dataset. The red and blue lines represent the SAH boundary line in the high and low ATAL years, respectively. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 99% confidence level by the Student’s t test. Arrows represent the differences in the horizontal wind field (vectors with scale of 5 m/s) at 150 hPa. b Differences in SAH indices. The yellow, orange, and green bars respectively denote the intensity (10−3 gpm), area (10−1 grid points), and eastward extension index (degree) of the SAH, with error bars denoting 95% confidence intervals calculated by the Student’s t test. c–e The probability density functions of the area, intensity, and eastward extension index of the SAH. The solid red and blue lines depict the probability density curves of SAH indices in the high and low ATAL years, and the dashed red and blue lines represent the mean values of SAH indices with the filling area indicating the range from the 5th percentile to the 95th percentile.

The results above suggest that the ATAL may have an impact on the SAH. To further verify that the ATAL could influence the SAH during boreal summer, two time-slice experiments are performed with the WACCM4 (hereafter referred as ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment). In CTRL experiment, aerosols are fixed to the MERRA-2 aerosols field in the year 2000. In ATAL experiment, we increased the aerosol concentration in the ATAL region by 1.5 times during JJA relative to that in CTRL experiment (more model setup details can be found in Methods). Fig. 2a shows geopotential height differences at 150 hPa in JJA between ATAL and CTRL experiments. There exist negative geopotential height anomalies in most areas over the ASM region, with a magnitude of around −5 gpm. Figure 2c–e show the PDFs of the SAH intensity index, area index, and eastward extension index in ATAL and CTRL experiments. Similar to those in the reanalysis data, the PDFs of these three indices shift towards lower values in ATAL experiment relative to those in CTRL experiment. The difference of aerosol loading averaged within the ATAL between ATAL and CTRL experiments is 0.62 ppbm, suggesting that a 0.62 ppbm enhancement of the ATAL aerosol loading in the model leads to a weakening of SAH intensity by 10%, a decrease in the SAH area by 6%, and a westward shift of the SAH by approximately 3°. The proportion of intensity reduction (area decrease) is calculated based on the difference between the intensity (area) index of the SAH in CTRL experiment and ATAL experiment, divided by the intensity (area) index of the SAH in CTRL experiment. Noted that the differences in the response of the SAH’s intensity and area indices between the model results and the reanalysis data in Figs. 1c–e and 2c–e may be mainly caused by differences in data horizontal resolutions between the MERRA-2 reanalysis and the CESM outputs. On the other hand, the CESM is unable to well resolve some important physical processes, e.g., aerosol-cloud micro-physical processes, which may be another reason. Differences in the SAH area, intensity, and eastward extension are shown in Fig. 2b, which indicate the weakening and contraction of the modeled SAH in ATAL experiment (statistically significant at the 95% confidence level). It should be noted that magnitudes of anomalies of the three SAH indices in the numeric simulations are smaller than those derived from reanalysis data. One possible reason is that the aerosol loading in reanalysis data is slightly different from that in the model simulations. It should also be pointed out that efforts have been made to remove the signals of other external forcings (volcanic eruptions, ENSO, etc.) in Fig. 1. However, there may still exist other feedbacks, which may lead to differences between results derived from simulations and reanalysis data.

a Modeled geopotential height differences at 150 hPa in JJA between ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment (ATAL experiment - CTRL experiment). The red and blue lines represent the SAH boundaries in ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment, Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 95% confidence level by the Student’s t test. Arrows represent the differences in the modeled horizontal wind field (vectors with scale of 2.5 m/s) at 150 hPa. b Differences in modeled SAH indices. The yellow, orange, and green bars respectively denote the intensity (10−2 gpm), area (grid points), and eastward extension index (degree) of the SAH, with error bars denoting 95% confidence intervals calculated by the Student’s t test. c–e The probability density functions of the modeled SAH area, intensity, and eastward extension indices. The solid red and blue lines depict the probability density curves of SAH indices in ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment, dashed red and blue lines represent the mean values of SAH indices, with the filling area indicating the range from the 5th percentile to the 95th percentile.

The mechanisms of the SAH response to the ATAL

The above analysis suggests that the ATAL indeed has an impact on the SAH. In this section, we try to clarify potential processes and mechanisms responsible for this impact. The SAH is a warm high-pressure system, with its variations closely linked to atmospheric temperature changes26,42. When air contracts due to cooling, isobaric surfaces will sink, resulting in anomalous low pressure relative to surrounding areas. Therefore, we first link the impact of the ATAL on the SAH with anomalous temperature changes in the upper troposphere in the ATAL region.

Figure 3a, b illustrate temperature differences at 150 hPa derived from the reanalysis data and model simulations. It is evident from both the reanalysis data and model simulations that there exist cooling anomalies in the ATAL region, with a maximum value of −0.5 K, which corresponds to the weakening of the SAH when ATAL intensifies, as depicted in Figs. 1a and 2a. Figure 3c, d further show altitude-latitude cross sections of temperature differences over 40°E-110°E. There are significant cooling anomalies south of 30°N in the whole troposphere. Previous studies argued that dust aerosols account for a large proportion of the ATAL aerosols in MERRA-2 reanalysis data, which are supposed to heat the atmosphere due to their absorption of solar radiation43,44,45. In our model simulations, the aerosol field is adopted from the MERRA-2 reanalysis data, in which dust aerosols also account for a significant portion of the ATAL. Thus, a question raises here as to how the intensification of the ATAL leads to temperature decreases in the upper troposphere over the ASM region.

a Temperature differences at 150 hPa in JJA between the high and low ATAL years, b as in (a), but for modeled temperature differences between ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment, c Altitude-latitude cross sections of temperature differences in the longitude band 40°E-110°E in JJA between the high and low ATAL years, d as in (c), but for differences between ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 95% confidence level by the Student’s t test.

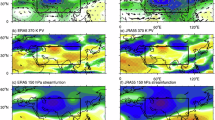

To further understand the temperature response to the ATAL, we decompose the temperature change into diagnostic components according to the local temperature change equation, including temperature changes due to advection, adiabatic heating caused by vertical motion, and diabatic heating. Fig. 4 shows altitude-latitude cross sections of temperature heating differences in the longitude band 40°E-110°E diagnosed from the reanalysis data and model simulations. Figure 4a, b show that adiabatic heating differences associated with the ATAL lead to an overall cooling effect in the ATAL region. Results from both model simulations and reanalysis data show that the adiabatic heating decreases significantly in the latitude band 20°N-35°N in the upper troposphere, consistent with upper tropospheric cooling anomalies. Figs. 4c, e show that the temperature change associated with advection is a warming effect in the upper troposphere of the ATAL region. The diabatic heating effect tends to increase the temperature in the middle and lower troposphere south of 30°N, with a relatively weak effect in the upper troposphere. Comparing temperature differences in Fig. 3 with heating rate differences in Fig. 4, we can see that the anomalous temperature advection (Fig. 4c, d) and direct radiative effect associated with the ATAL (Fig. 4e, f) tend to heat the air in the ATAL region. The strong temperature advection may be caused by the westward contraction of the eastern boundary of the SAH (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, the net effect of the ATAL is to cool the upper troposphere via anomalous adiabatic cooling. Although differences exist between modeled temperature changes (Figs. 4b, d, f) and corresponding composite results from the reanalysis data (Figs. 4a, c, e), it is apparent that the anomalous cooling in the upper troposphere in the ATAL region is mainly caused by the adiabatic dynamic cooling effect.

a, c, e Altitude-latitude cross sections of differences in the heating rate associated with vertical motion, temperature advection and diabatic heating in the longitude band 40°E-110°E in JJA between the high and low ATAL years, respectively. b, d, f as in (a, c, e), but for differences between ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test. Note that size ranges in MERRA-2 are −1.8–1.8 × 10−6 K/s and in model simulations are −0.9–0.9 × 10−6 K/s.

Adiabatic cooling rate differences in Fig. 4a, b are caused by anomalous upward motion in the upper troposphere. Figure 5a, b show altitude-latitude cross sections of vertical velocity differences in the reanalysis data and model simulations. In response to the ATAL, the pressure velocity in the vertical exhibits a significant decrease from the lower troposphere to the upper troposphere within the latitude band 20°N–30°N, indicating significant anomalous ascending motion in this region. Negative anomalies in modeled vertical velocity (Fig. 5b) are relatively smaller than those derived from the reanalysis data (Fig. 5a), possibly due to some other processes in the composite results that are not well captured by the model simulations. Overall, both the reanalysis data and model results confirm the presence of significant anomalous ascending motion in the ATAL region, which leads to adiabatic ascent cooling in the upper troposphere.

a Altitude-latitude cross sections of vertical velocity differences in the longitude band 40°E–110°E in JJA between the high and low ATAL years, b as in (a), but for vertical velocity differences between ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test.

According to the diagnostic equation for the pressure velocity in the vertical, when the diabatic heating rate is positive in a specific region, it implies ascending motion in this area. It is evident from Fig. 4e, f that positive anomalies in the diabatic heating rate exist in the ATAL region when the ATAL is intensified. Diabatic heating rate differences in Fig. 4 are mainly related to three processes, i.e., latent heat release, longwave and shortwave heating. Figure 6a–f illustrate altitude-latitude cross sections of diabatic heating differences associated with three different processes in the ATAL region. It can be noted that anomalous increases of the diabatic heating in south of 30°N are primarily caused by enhanced latent release (Fig. 6a, b) and longwave heating (Fig. 6c, d). Note that positive shortwave heating rate anomalies caused by the intensification of the ATAL can extend into the middle and lower troposphere, although the magnitude is relatively smaller compared to the anomalous latent heat rate and longwave heating rate anomalies.

a, c, e Altitude-latitude cross sections of differences in the latent heating (10−7 K/s), longwave heating (10−6 K/s) and solar heating (10−7 K/s) in the longitude band 40°E-110°E in JJA between the high and low ATAL years. b, d, f as in (a, c, e), but for differences between ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test. Note that size ranges of latent heating in MERRA-2 and modeled latent heating are −4.5–4.5 × 10−7 K/s, longwave heating in MERRA-2 and modeled longwave heating are −0.9–0.9 × 10−6 K/s, solar heating in MERRA-2 and modeled solar heating are −2.7–2.7 × 10−7 K/s.

Previous studies have reported that the heating effect of aerosols in the upper troposphere can enhance the moisture convergence from below46, while the enhanced moisture convergence from below tends to increase latent heat release and cloud fraction47,48. Fig. 7 shows altitude-latitude cross sections of moisture flux divergence and cloud fraction differences in the ATAL region in response to the ATAL. It can be observed from Fig. 7a, b that there is an anomalous convergence of moisture flux south of 35°N, indicating that moisture is accumulating in this region. The differences in the specific humidity also show that the water vapor increases anomalously in this region (Supplementary Fig. S2). Accompanied by significant anomalous upward flow, there is an abnormal increase in cloud fraction in the upper and middle troposphere in the ATAL region which leads to the blocking of longwave radiation emitted from the surface, resulting in an anomalous longwave heating effect beneath the clouds (Fig. 6c, d). The longwave heating effect can further enhance moisture convergence in the south of the plateau, favoring positive feedback for the increase in latent heat release from moisture condensation.

a, c Altitude-latitude cross sections of differences in the moisture flux divergence and cloud fraction in the longitude band 40°E–110°E in JJA between the high and low ATAL years. b, d as in (a, c), but for differences between ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test.

The SAH, as a component of the SASM and EASM systems, has a close connection with these two monsoon systems49. Therefore, we wonder if the weakening of the SAH caused by the ATAL has any impact on the Asian monsoon circulation. Fig. 8 illustrates the variations in the SASM index and EASM index during the peak monsoon periods in the high and low ATAL years. It can be seen that the model simulations are generally consistent with the synthetic results from the reanalysis data. When the ATAL strengthens, the SASM in the peak monsoon period weakens while the EASM in the peak monsoon period strengthens significantly. The relationship that a weakened SAH corresponds to a weakened SASM and a strengthened EASM is in accordance with previous studies33,50.

The red bars represent the monsoon indices in the high ATAL years and in ATAL experiment, and the blue bars represent the monsoon indices in the low ATAL years and in CTRL experiment. Error bars indicate the standard error. The standard error in the reanalysis results is calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the square root of the number of samples in the high and low ATAL years. The standard error in the model results is calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the square root of the number of samples in ATAL and CTRL experiments. Asterisks indicate that the differences in the monsoon index between the high and low ATAL years and between ATAL and CTRL experiments are significant. One asterisk, two and three asterisks represent the values that are significant at the 90%, 95% and 99% confidence level by the Student’s t test, respectively.

Nonlinear response of the SAH to the ATAL

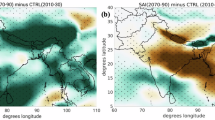

The results discussed in the preceding section indicate that the ATAL can lead to a significant temperature decrease in the upper troposphere via affecting the vertical velocity in the ATAL region, ultimately resulting in a weakened and contracted SAH. In this section, we attempt to clarify whether the impact of the ATAL on the SAH will become more significant with increased aerosol loading in the ATAL. One numerical experiment (hereafter referred as 2-ATAL experiment) is performed in which the aerosol mixing ratio in the ATAL is doubled with respect to that in CTRL experiment. Figure 9a shows the horizontal distribution of modeled geopotential height differences at the 150 hPa in JJA between 2-ATAL and CTRL experiments (2-ATAL experiment - CTRL experiment). It is apparent that the SAH is still weakened and reduced in spatial coverage in 2-ATAL experiment relative to that in CTRL experiment. However, it is interesting that the extent of its weakening and contracting is not as notable as that between ATAL and CTRL experiments.

a Modeled geopotential height differences at the 150 hPa in JJA between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment (2-ATAL experiment - CTRL experiment). The red and blue lines represent the SAH boundaries in 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Arrows represent the differences in the modeled horizontal wind field (vectors with scale of 2.5 m/s) at 150 hPa. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test. b Differences in SAH indices between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. The yellow, orange and green bars respectively denote intensity (10−2 gpm), area (grid points), and eastward extension index (degree) of the SAH, with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals calculated by the Student’s t test.

To clarify why the impact of the ATAL on the SAH is nonlinear, Fig. 10a–c show differences in the air temperature and static stability within the longitude band 40°E–110°E between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Note that there is an anomalous cooling of up to 0.4 K at 500–100 hPa in the troposphere, which corresponds to the weakening of the SAH at 150 hPa. In contrast to that in ATAL experiment, a significant warming of around 0.2 K is observed above 100 hPa, consequently forming an “upper-warm and lower-cold” temperature structure which leads to an increase in static stability, as shown in Fig. 10b. The increase in static stability in the upper troposphere will be less favorable for the occurrence of deep convective activities. Also note that there are significant cooling anomalies at the surface over most parts of South Asia and East Asia (Fig. 10c), which tend to inhibit the upward motion and reduce adiabatic cooling. These results suggest that the changes in adiabatic heating as suggested in ATAL experiment are not the main cause of cooling anomalies in the SAH in response to the doubled aerosol loading in the ATAL.

a Altitude-latitude cross sections of modeled temperature differences within the longitude band 40°E–110°E in JJA between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 95% confidence level by the Student’s t test. b as in (a), but for modeled static stability differences. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 95% confidence level by the Student’s t test. c Surface temperature differences in JJA between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test.

Figure 11 further shows altitude-latitude cross sections of heating rate differences associated with the diabatic heating, temperature advection and adiabatic heating within the longitude band 40°E-110°E between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. It is evident from Fig. 11a that positive anomalies in the adiabatic heating exist in the SAH region. In contrast, the diabatic heating and temperature advection decrease significantly in this region (Fig. 11b, c). Comparing temperature differences in Fig. 10 with heating rate differences in Fig. 11, we can see that the anomalous cooling between 500–100 hPa is mainly caused by the diabatic cooling effect. Unlike the anomalous cooling in the ATAL region discussed in ATAL experiment, where the anomalous cooling in the upper troposphere in the ATAL region is mainly caused by the adiabatic dynamic cooling effect (Fig. 4), the diabatic cooling has a substantial influence on the anomalous cooling in the middle to upper troposphere in the ATAL region in response to the doubled aerosol loading.

a–c Altitude-latitude cross sections of differences in heating rate differences associated with adiabatic heating, temperature advection and diabatic heating, respectively within longitude band 40°E–110°E in JJA between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test.

Figure 12 shows altitude-latitude cross sections of heating rate differences associated with latent heating, solar heating and longwave heating within the longitude band 40°E-110°E in JJA between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. It can be seen that when the aerosol mixing ratio in the ATAL is doubled, both shortwave and longwave heating rates in the upper troposphere increase significantly which tend to heat the air in the ATAL region. The solar heating effect associated with doubled ATAL loading is stronger than the solar heating rate shown in Fig. 6e, f. While the latent heating rate in the middle to upper troposphere decreases significantly. Compared with relatively smaller positive anomalies in the longwave heating rate and solar heating rate in the upper troposphere in Fig. 12b, c, the significant decrease in the diabatic heating suggests that cooling anomalies in the middle to upper troposphere are mainly caused by reduced latent heat release, as shown in Fig. 12a. Additionally, here we mainly focus on the dominant factors of the anomalous cooling in the upper and middle troposphere. The anomalous heating in the upper troposphere due to diabatic processes is more intuitively illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S3. Through the decomposition of the temperature increase region above 100 hPa, we find that the positive temperature anomalies above 100 hPa are mainly caused by the solar heating associated with the enhanced ATAL. (Supplementary Fig. S4).

a–c Altitude-latitude cross sections of differences in the modeled latent heating rate, longwave heating rate and shortwave heating rate within the longitude band 40°E–110°E in JJA between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment, respectively. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test. Note that size ranges of the modeled DTCOND and longwave heating are −7.2–7.2 × 10−7 K/s, the size range of the modeled solar heating is −2.7–2.7 × 10−7 K/s.

To understand why the latent heat release is significantly decreased in 2-ATAL experiment, Fig. 13a shows altitude-latitude cross sections of differences in moisture flux divergence within the longitude band 40°E–110°E between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. Note that the moisture flux divergence is anomalously large in the lower troposphere south of 35°N in response to the doubled aerosol loading in the model suggesting weakened convective activities. Fig. 13b shows altitude-latitude cross sections of differences in modeled vertical velocity within the longitude band 40°E–110°E. In accordance with Fig. 13a, anomalous descending flow can be observed at 500–100 hPa which reduces upward transport of moisture and thus reduces the release of latent heat from condensation. The anomalous descending flow in the middle and upper troposphere in the ATAL region is closely related to the increasing static stability in the upper troposphere shown in Fig. 10b. Figure 13c shows altitude-latitude cross sections of cloud fraction differences within the longitude band 40°E–110°E between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. It is apparent that the cloud fraction significantly decreases over regions with anomalous descending airflow and moisture flux divergence anomalies, in agreement with weakened convective activities and upward transport of water vapor from below in response to doubled aerosol loading in the ATAL.

a Altitude-latitude cross sections of differences in the modeled moisture flux divergence within longitude band 40°E–110°E in JJA between 2-ATAL experiment and CTRL experiment. b, c as in (a), but for the modeled vertical velocity and cloud fraction differences. Slashed regions are for values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level by the Student’s t test.

The weakened response of the SAH to doubled ATAL concentrations suggests a nonlinear sensitivity of the SAH to the ATAL aerosol loading. To further elucidate this nonlinear response, we perform another numerical experiment in which the aerosol loading of the ATAL is reduced to half of its magnitude in CTRL experiment. The SAH indices in 0.5 ATAL experiment exhibit no significant changes compared to those in CTRL experiment (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Discussion

This study analyzes the impact of the ATAL on the SAH as well as SAM using reanalysis data and the CESM-WACCM4 model. It is revealed that the ATAL tends to weaken the SAH and the South Asian Monsoon (SAM). The weakening of the SAH in response to the ATAL is accompanied by a significant westward contraction of its eastern boundary. The weakening of the SAH and its reduced spatial coverage are closely associated with anomalous cooling in the ATAL region induced by the dynamic-radiative feedbacks associated with aerosols in the ATAL. The aerosols within the ATAL first heat the ATAL region via radiative effect and then, cause an accumulation of water vapor in the lower troposphere over the ATAL region. The aerosol’s radiative effect further leads to an increase in latent heat release from water vapor condensation, accompanied by an increase in cloud fraction. The increased latent heating release in the upper troposphere over the ATAL region is conducive to triggering anomalous upward motion, while the anomalous ascending motion tends to cool the upper troposphere via adiabatic cooling. The cooling of the upper troposphere ultimately results in a weakening of the SAH and the SAM.

However, the CESM model simulations reveal that the response of the SAH to the ATAL is nonlinear. The nonlinear responses of the SAH and temperature in the SAH region are visually presented in Supplementary Fig. S6. The ATAL with an aerosol loading of about 0.5 ppbm could result in a 17% weakening in the intensity of the SAH. When the aerosol loading of the ATAL layer is doubled in the model (~1 ppbm), the SAH still exhibits a weakening and contraction, but the extent of its weakening and contraction is not as notable as that resulted from the ATAL with an aerosol loading of about 0.5 ppbm. This nonlinear response is due to nonlinear feedbacks of the atmosphere associated with the aerosols’ radiative effect. When the aerosol loading of the ATAL is lower, the ATAL induces an anomalous upward motion which cools the upper troposphere and hence a weakening of the SAH. When the aerosol loading in the ATAL is further increased, the aerosol-induced heating stabilizes the upper troposphere, and deep convective activities are weakened. Therefore, the dominant process by which the ATAL weakens the SAH varies with increased aerosol loading in the ATAL. However, the overall effect is that the existence of the ATAL tends to weaken the SAH, and the net SAH response to the ATAL can essentially be attributable to the diabatic heating mechanism.

This study highlights the role of aerosol changes in the ATAL in modulating the SAH in summer. However, there are differences between the results derived from reanalysis data and model simulations. Due to the considerable uncertainty in the sub-grid processes of aerosol-cloud microphysical interactions in model simulations, our study focuses more on the radiative effects of aerosols and does not account for the aerosol-cloud microphysical processes. Moreover, in the composite analysis, although we have removed the signals of other external forcings (such as volcanic eruptions, ENSO, etc.), there may still be other feedbacks that could lead to differences between the results derived from simulations and reanalysis data.

Previous studies40 have also revealed that the anthropogenic aerosol plays an important role in the weakening of the SAH. However, our findings emphasize the role of the ATAL in weakening the SAH and the nonlinear response with the enhanced ATAL. Additionally, our study shows that the increase in aerosol concentrations in the ATAL leads to an enhancement of the Indian summer monsoon and a weakening of the East Asian summer monsoon, which is consistent with previous studies on the impact of aerosols on monsoons51,52,53,54. Furthermore, with the emissions from East Asia and South Asia exhibiting different trends in recent years, changes in the ATAL and its climate effects are still worthy of further analysis. Considering the significant role of the SAH in modulating precipitation in the Asian monsoon region, further work is needed to identify and better understand the impact of the ATAL on precipitation in the Asian monsoon region.

Methods

Reanalysis data sets

Our study utilizes aerosol mixing ratio data from NASA’s Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2), which includes various types of aerosols such as dust aerosols, black carbon aerosols, sulfate aerosols, organic carbon aerosols, and sea salt aerosols. The aerosol mixing ratio data covers 72 pressure levels vertically from 985 hPa to 0.01 hPa, with a horizontal resolution of 0.5° × 0.625° (latitude × longitude) and a temporal resolution of 3 h55.

Daily geopotential height, zonal and meridional winds, vertical velocity, diabatic heating rate (including solar heating rate, longwave heating rate and latent heating rate), cloud fraction, specific humidity and temperature data are extracted from the MERRA-2 3-hourly data on pressure levels. The data selected for analysis is from the JJA of 1980–2023, with a horizontal resolution of 1.25° × 1.25° (latitude × longitude) and 42 pressure levels in the vertical direction extending from 1000 to 0.1 hPa56. It is important to note that all anomalies obtained from reanalysis data are calculated as differences between the high and low ATAL years.

Model simulations

The Community Earth System Model (CESM) is a fully coupled global climate model developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in the United States, which includes modules for the atmosphere, ocean, land surface, and sea ice. In this study, the F_2000_WACCM_SC (FWSC) component in the CESM is used to verify the impact of the ATAL on the SAH in summer. The FWSC component is the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model, version 4 (WACCM4)57, with specified chemistry forcing fields (such as ozone, greenhouse gases, aerosols, and so on). The dynamical module in the WACCM4 is based on the Community Atmospheric Model version 4 (CAM4) with a finite-volume dynamical core and interactive tropospheric and stratospheric chemistry. WACCM4 consists of 66 layers extending from the surface to 145 km height (5.1 × 10−6 hPa). The vertical resolution in the tropical tropopause layer and the lower stratosphere (located below the height of 30 km) is 1.1–1.4 km. The horizontal resolution in the simulations conducted in this paper is 1.9° × 2.5° (latitude × longitude).

Several WACCM4 experiments are conducted to investigate the impact of changes in the ATAL on the SAH in boreal summer. Considering that there is still considerable uncertainty regarding the sub-grid processes of aerosol-cloud microphysical interactions in model simulations58,59, we focus more on the changes in the atmospheric circulation system caused by aerosol radiative effects. In CTRL experiment, aerosols are fixed to the MERRA-2 aerosol distribution from the year 2000. In ATAL experiment, we select the region 15°-45°N, 15°E-120°E between 70 hPa and 170 hPa as the ATAL region and increase the aerosol concentration in each grid point in the ATAL region by 1.5 times relative to that in CTRL experiment from June to August, the temporal and spatial variations of aerosols in the ATAL in summer still exist. Aerosol concentrations in other regions remain consistent with those in CTRL experiment and are not affected by the enhancement of the ATAL. The increase of aerosols in ATAL experiment is consistent with the difference in aerosols between the high and low ATAL years in the reanalysis data. 2-ATAL experiment is similar to ATAL experiment, but with doubled aerosol concentrations in the ATAL region, which represents a more extreme scenario in the future under continuously increasing aerosol emissions. 0.5 ATAL experiment replicates ATAL experiment, but with a 50% reduction in aerosol concentrations within the ATAL region, which represents a moderate reduction scenario compared to CTRL experiment. All experiments are run for 25 years with the first 10 years taken as the model “spin up” time. Results of the remaining 15 years of model output are analyzed. It is important to note that all anomalies obtained from model results are calculated as differences between experiments with the varied ATAL and CTRL experiment.

Definitions

To investigate the impact of the ATAL on the SAH in summer, we analyze the ATAL aerosol mixing ratio from 1980 to 2023 and selected years with high and low ATAL aerosol concentrations. Based on previous research11,37 and the aerosol field from MERRA-2 reanalysis data (Supplementary Fig. S7), the ATAL region is defined as 15°N-45°N, 15°E-120°E between 70 hPa and 170 hPa. An index of the ATAL intensity is defined as the aerosol mixing ratio averaged in the ATAL region in JJA. Years of anomalously high and low ATAL are identified if the detrended and normalized ATAL intensity index is greater than 0.5 and less than −0.5 standard deviation, respectively. To eliminate the influence of volcanic eruptions on the ATAL, we remove years which aerosols in MERRA-2 abruptly increased due to volcanic eruptions over the ASM region (1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 2009, 2010)11,60. More information on the aerosol distribution in these years can be found in Supplementary Fig. S8. It is worth noting that the sea surface temperatures (SSTs) of the Indian and North Atlantic oceans have an important role in modulating the intensity of the SAH61,62,63. To eliminate the potential impact of SSTs variations on the SAH during the high and low ATAL years, the linear regression of the SSTs in these regions related to the ATAL is removed and the linear trend of the ATAL is also detrended. Based on the above criteria, six years of anomalously high ATAL and eleven years of anomalously low ATAL are identified.

Three indices are adopted to reflect the meridional range, area and intensity of the SAH based on previous research64,65,66. Specifically, the eastward extension index is defined as the longitude of the eastern grid point of the SAH boundary line at 150 hPa. The area index is defined as the sum of the number of grid points with geopotential height greater than or equal to the value of the SAH boundary line within the region 10°N-50°N, 30°E-120°E at 150 hPa. The intensity index is defined as the sum of the differences between the geopotential height values of grid points with geopotential height greater than or equal to the value of the SAH boundary line within the region 10°N-50°N, 30°E-120°E at 150 hPa and the value of the SAH boundary line. Additionally, according to previous studies67,68, we choose 14340 gpm as the SAH boundary line in MERRA-2 dataset and to maintain consistency with the range of the SAH in MERRA-2, we choose 14380 gpm as the modeled SAH boundary line.

When analyzing the thermal structure of the Asian monsoon region, we used the local temperature change equation, which is specifically represented as:

where T, t, γd, γ, ω, p, Cp, and \(\mathop{{V}_{h}}\limits^{\rightharpoonup }\) represent temperature, time, adiabatic lapse rate, temperature lapse rate, vertical velocity, pressure, specific heat at constant pressure, horizontal component of wind, respectively.\(\nabla\) denotes the two-dimensional gradient operator. The gas constant R = 287.4 J/(kg・K), the gravitational acceleration g = 9.8 m/s². And \(\frac{dQ}{dt}\) is the diabatic heating rate. This equation describes the temporal and spatial changes in temperature, where the first term represents the temperature advection effect, the second term represents the adiabatic heating due to vertical motion, and the third term represents the impact of diabatic heating on temperature. The diabatic heating term mainly includes the shortwave radiation heating rate (QRS), longwave radiation heating rate (QRL), and latent heating rate (DTCOND), which are output variables in CESM.

Two monsoon indices are adopted to quantitatively measure the change of the South Asia summer monsoon (SASM) and East Asia summer monsoon (EASM) circulation. Following Webster & Yang69 and Chen et al. 70, we defined the SASM index as the zonal wind shear between 850 hPa and the average of the 150 and 100 hPa, averaged over 40°E–110°E and 0–20°N. Following He & Zhou71, we defined the EASM index as the regional averaged meridional wind at 850 hPa over 25°N–50°N, 110°E–120°E.

The static stability is a parameter used to represent the stability of the atmosphere. When the static stability is less than 0, the atmospheric stratification is unstable, and vice versa. The formula for static stability can be written as72:

where T represents temperature, \(\theta\) represents potential temperature, and p represents pressure.

Data availability

MERRA-2 datasets are available from https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets. The SST data are from https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html. The data from WACCM experiments that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Code availability

All codes are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

References

Lawrence, M. G. Air Pollution (ed Stohl, A.) 131-172 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004).

Nakata, M., Mukai, S. & Yasumoto, M. Seasonal and regional characteristics of aerosol pollution in East and Southeast Asia. Front. Environ. Sci. 6, 29 (2018).

Abdul, J. S. et al. Air quality, pollution and sustainability trends in South Asia: a population-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 7534 (2022).

Park, M. et al. Chemical isolation in the Asian monsoon anticyclone observed in Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE-FTS) data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 757–764 (2008).

Lau, W. K. M., Yuan, C. & Li, Z. Origin, maintenance and variability of the Asian Tropopause Aerosol Layer (ATAL): the roles of monsoon dynamics. Sci. Rep. 8, 3960 (2018).

Yuan, C., Lau, W. K. M., Li, Z. Q. & Cribb, M. Relationship between Asian monsoon strength and transport of surface aerosols to the Asian Tropopause Aerosol Layer (ATAL): interannual variability and decadal changes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 1901–1913 (2019).

Bian, J. et al. Transport of Asian surface pollutants to the global stratosphere from the Tibetan Plateau region during the Asian summer monsoon. Natl Sci. Rev. 7, 516–533 (2020).

Babu, S. S. et al. Free tropospheric black carbon aerosol measurements using high altitude balloon: Do BC layers build “their own homes” up in the atmosphere? Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L08803 (2011).

Martinsson, B. G. et al. Formation and composition of the UTLS aerosol. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2, 40 (2019).

Ma, J. et al. Modeling the aerosol chemical composition of the tropopause over the Tibetan Plateau during the Asian summer monsoon. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 11587–11612 (2019).

Vernier, J. P., Thomason, L. W. & Kar, J. CALIPSO detection of an Asian tropopause aerosol layer. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010gl046614 (2011).

Yu, P. et al. Efficient transport of tropospheric aerosol into the stratosphere via the Asian summer monsoon anticyclone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6972–6977 (2017).

Fadnavis, S. et al. Transport of aerosols into the UTLS and their impact on the Asian monsoon region as seen in a global model simulation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8771–8786 (2013).

Solomon, S. et al. Monsoon circulations and tropical heterogeneous chlorine chemistry in the stratosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 12624–12633 (2016).

Rosenlof, K. H. Changes in water vapor and aerosols and their relation to stratospheric ozone. C. R. Geosci. 350, 376–383 (2018).

Fadnavis, S. et al. Elevated aerosol layer over South Asia worsens the Indian droughts. Sci. Rep. 9, 10268 (2019).

Vernier, H. et al. Exploring the inorganic composition of the Asian Tropopause Aerosol Layer using medium-duration balloon flights. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2021, 1–30 (2021).

Peng, Y., Tian, W., Li, C., Xue, H. & Yu, P. Distinct radiative and chemical impacts between the equatorial and northern extratropical volcanic injections. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2024JD041690 (2024).

Park, M., Randel, W. J., Gettelman, A., Massie, S. T. & Jiang, J. H. Transport above the Asian summer monsoon anticyclone inferred from Aura Microwave Limb Sounder tracers. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jd008294 (2007).

Randel, W. J. et al. Asian monsoon transport of pollution to the stratosphere. Science 328, 611–613 (2010).

Niu, H., Kang, S., Gao, W., Wang, Y. & Paudyal, R. Vertical distribution of the Asian tropopause aerosols detected by CALIPSO. Environ. Pollut. 253, 207–220 (2019).

Yang, S., Wei, Z., Chen, B. & Xu, X. Influences of atmospheric ventilation on the composition of the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere during the two primary modes of the South Asia high. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 132, 559–570 (2020).

Wu, D. et al. Seasonal to sub-seasonal variations of the Asian Tropopause Aerosols Layer affected by the deep convection, surface pollutants and precipitation. J. Environ. Sci. 114, 53–65 (2022).

Bossolasco, A. et al. Global modeling studies of composition and decadal trends of the Asian Tropopause Aerosol Layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 2745–2764 (2021).

Fairlie, T. D. et al. Estimates of regional source contributions to the asian tropopause aerosol layer using a chemical transport model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD031506 (2020).

Qian, Y., Zhang, Q., Yao, Y. & Zhang, X. Seasonal variation and heat preference of the South Asia high. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 19, 821–836 (2002).

Hanumanthu, S. et al. Strong day-to-day variability of the Asian Tropopause Aerosol Layer (ATAL) in August 2016 at the Himalayan foothills. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 14273–14302 (2020).

Xue, X., Chen, W., Chen, S., Sun, S. & Hou, S. Distinct impacts of two types of South Asian highs on East Asian summer rainfall. Int. J. Climatol. 41, E2718–E2740 (2021).

Zhang, D., Huang, Y., Zhou, B. & Wang, H. Is there interdecadal variation in the South Asian High? J. Clim. 34, 8089–8103 (2021).

Lu, M., Yang, S., Fan, H. & Wang, J. Interdecadal instability of the interannual connection between southern Tibetan Plateau precipitation and Southeast Asian summer monsoon. Atmos. Res. 291, 106825 (2023).

Liu, B., Wu, G., Mao, J. & He, J. Genesis of the South Asian High and Its Impact on the Asian Summer Monsoon Onset. J. Clim. 26, 2976–2991 (2013).

Wei, W., Wu, Y., Yang, S. & Zhou, W. Role of the South Asian high in the onset process of the asian summer monsoon during spring-to-summer transition. Atmosphere 10, 239 (2019).

Jiang, X., Li, Y., Yang, S. & Wu, R. Interannual and interdecadal variations of the South Asian and western Pacific subtropical highs and their relationships with Asian-Pacific summer climate. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 113, 171–180 (2011).

Wei, W., Zhang, R., Wen, M., Rong, X. & Li, T. Impact of Indian summer monsoon on the South Asian High and its influence on summer rainfall over China. Clim. Dyn. 43, 1257–1269 (2014).

Yin, Y. et al. Changes in the summer extreme precipitation in the Jianghuai plum rain area and their relationship with the intensity anomalies of the South Asian high. Atmos. Res. 236, 104793 (2020).

Liu, H., Li, R. & Ma, J. Spatiotemporal and vertical distribution of asian tropopause aerosol layer using long-term multi-source data. Remote Sens. 15, 1315 (2023).

Gao, J., Huang, Y., Peng, Y. & Wright, J. S. Aerosol effects on clear‐sky shortwave heating in the Asian monsoon tropopause layer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2022JD036956 (2023).

Vernier, J. P. et al. Increase in upper tropospheric and lower stratospheric aerosol levels and its potential connection with Asian pollution. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 1608–1619 (2015).

Peng, Y. et al. Perturbation of tropical stratospheric ozone through homogeneous and heterogeneous chemistry due to Pinatubo. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103773 (2023).

Zhang, D., Huang, Y., Zhou, B. & Wang, H. Contributions of external forcing to the decadal decline of the South Asian High. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099384 (2022).

Qie, K., Tian, W., Bian, J., Xie, F. & Li, D. Weakened Asian summer monsoon anticyclone related to increased anthropogenic aerosol emissions in recent decades. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 140 (2025).

Randel, W. J. & Park, M. Deep convective influence on the Asian summer monsoon anticyclone and associated tracer variability observed with Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 111, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jd006490 (2006).

Lau, K. M., Kim, M. K. & Kim, K. M. Asian summer monsoon anomalies induced by aerosol direct forcing: the role of the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 26, 855–864 (2006).

Kim, M. K. et al. Amplification of ENSO effects on Indian summer monsoon by absorbing aerosols. Clim. Dyn. 46, 2657–2671 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Scattering and absorbing aerosols in the climate system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 363–379 (2022).

Lau, W. K. & Kim, K. M. Recent trends in transport of surface carbonaceous aerosols to the upper‐troposphere‐lower‐stratosphere linked to expansion of the Asian summer monsoon anticyclone. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2022JD036460 (2022).

Perlwitz, J. & Miller, R. L. Cloud cover increase with increasing aerosol absorptivity: A counterexample to the conventional semidirect aerosol effect. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009jd012637 (2010).

Li, Z. Q. et al. Long-term impacts of aerosols on the vertical development of clouds and precipitation. Nat. Geosci. 4, 888–894 (2011).

Krishnamurty, T. & Bhalme, H. Oscillations of a monsoon system Pt. I Observational aspects. J. Atmos. Sci. 33, 1937–1954 (1976).

Ashfaq, M. et al. Suppression of South Asian summer monsoon precipitation in the 21st century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008gl036500 (2009).

Asutosh, A., Tilmes, S., Bednarz, E. M. & Fadnavis, S. South Asian Summer Monsoon under stratospheric aerosol intervention. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 3 (2025).

Bollasina, M. A., Ming, Y. & Ramaswamy, V. Anthropogenic aerosols and the weakening of the South Asian summer monsoon. Science 334, 502–505 (2011).

Xie, X. et al. Distinct responses of Asian summer monsoon to black carbon aerosols and greenhouse gases. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 11823–11839 (2020).

Zhuang, B. et al. Interaction between different mixing aerosol direct effects and East Asian summer monsoon. Clim. Dyn. 61, 1157–1176 (2023).

Molod, A., Takacs, L., Suarez, M. & Bacmeister, J. Development of the GEOS-5 atmospheric general circulation model: evolution from MERRA to MERRA2. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 1339–1356 (2015).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Marsh, D. R. et al. Climate change from 1850 to 2005 Simulated in CESM1(WACCM). J. Clim. 26, 7372–7391 (2013).

He, J. et al. Decadal simulation and comprehensive evaluation of CESM/CAM 5.1 with advanced chemistry, aerosol microphysics, and aerosol‐cloud interactions. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 7, 110–141 (2015).

Liu, X. et al. Toward a minimal representation of aerosols in climate models: description and evaluation in the Community Atmosphere Model CAM5. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 709–739 (2012).

Kloss, C. et al. Reconsidering the Existence of a Trend in the Asian Tropopause Aerosol Layer (ATAL) From 1979 to 2017. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD039784 (2024).

Huang, G., Qu, X. & Hu, K. The impact of the Tropical Indian Ocean on South Asian High in Boreal Summer. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 28, 421–432 (2011).

Qu, X. & Huang, G. The decadal variability of the tropical Indian Ocean SST–the South Asian High relation: CMIP5 model study. Clim. Dyn. 45, 273–289 (2015).

Ge, J. et al. Impact of the springtime tropical North Atlantic SST on the South Asian High. Clim. Dyn. 61, 4159–4172 (2023).

Peng, L., Sun, Z., Ni, D., Chen, H. & Tan, G. Interannual variation of summer South Asia high and its association with ENSO. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 33, 783–795 (2009).

Qu, X. & Huang, G. An enhanced influence of tropical Indian Ocean on the South Asia High after the Late 1970s. J. Clim. 25, 6930–6941 (2012).

Ning, L., Liu, J. & Wang, B. How does the South Asian High influence extreme precipitation over eastern China? J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 4281–4298 (2017).

Zhang, P., Yang, S. & Kousky, V. E. South Asian high and Asian-Pacific-American climate teleconnection. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 22, 915–923 (2005).

Wu, H., Luo, J., Ji, H., Wang, L. & Tian, H. Horizontal and vertical structure of the South Asia High and their variation characteristics. J. Arid. Meteorol. 37, 736 (2019).

Webster, P. J. & Yang, S. Monsoon and Enso - Selectively Interactive Systems. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 118, 877–926 (1992).

Chen, H., Ding, Y. & He, J. Reappraisal of Asian summer monsoon indices and the long-term variation of monsoon. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 21, 168–178 (2007).

He, C. & Zhou, W. Different Enhancement of the East Asian Summer Monsoon under Global Warming and Interglacial Epochs Simulated by CMIP6 Models: Role of the Subtropical High. J. Clim. 33, 9721–9733 (2020).

Bluestein, H. Principles of kinematics and dynamics. 448 (Oxford University Press, 1992).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42394120, 42394124 and 42405072), Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M743433), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (Grade B) of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (GZB20230728). We thank the scientific teams for providing MERRA-2 data and the WACCM4. We also appreciate the computing support provided by the Supercomputing Center of Lanzhou University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. and W.T. conceptualized and designed the project. Y.S. conducted the model experiments and carried out the data analysis. W.T. and K.Q. contributed to the interpretation of the results, offered valuable suggestions, and revised the manuscript. Y.P. contributed to the experiment parts and helped interpret the results. S.M. checked the paper and proposed amendments. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Y., Tian, W., Qie, K. et al. Nonlinear responses of the South Asian High to the Asian tropopause aerosol layer in summer. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 196 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01085-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01085-x