Abstract

The responses of the western North Pacific (WNP) tropical cyclone (TC) genesis and associated large-scale atmospheric environment to varying CO2 pathways are investigated using an idealized CO2 removal experiment. In the experiment, CO2 concentration is first increased at the rate of 1% year−1 until quadrupled and then decreased at the same rate until it reaches the initial level. Our results indicate asymmetric changes in WNP peak-season (July–September) TC genesis between CO2 ramp-up and ramp-down periods, showing a significant reduction of TC genesis over the Philippine Sea and landfalling TCs in East Asia when the CO2 concentration is reduced. Such TC activity changes are attributed to the development of WNP anticyclonic circulation in the ramp-down period, in association with an El Niño-like delayed response in sea surface temperature. This asymmetric response of WNP TC activities to symmetric CO2 pathway may provide a reference for regional TC disaster prevention and preparations under mitigation conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global warming due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions has brought complicated changes in the Earth’s climate and ecosystem, increasing the risk of climate hazards1. Reducing greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere is necessary to limit the ongoing climate changes2, through approaches such as carbon dioxide removal (CDR). The potential impact of CDR on the global climate has thus gained attention and has been investigated by numerous modeling studies with idealized CO2 pathways3. Studies have revealed a nonlinearity in the responses of various climate components to CDR, including global temperature and precipitation4,5,6, extreme summer rainfall in East Asia4, and South Asian monsoon precipitation6,7. While changes in precipitation intensity or distribution by CDR are widely covered in the literature, how CDR may impact synoptic weather systems responsible for precipitation, such as tropical cyclones (TCs) or extratropical cyclones, has only recently been addressed in a few studies8,9.

TC is one of the most destructive weather systems that can cause heavy rainfall, storm surges, and floods, threatening millions of people yearly, especially in coastal regions10. It is responsible for 15–40% of annual precipitation in coastal areas of Asia, the United States, and Australia11,12 and 30–50% of extreme precipitation in East Asia and North America13,14. Changes in TC activity under global warming have thus been extensively studied, with a general consensus that global warming will decrease TC frequency but increase TC intensity and precipitation15. Such changes have been related to large-scale environmental changes, such as weaker mid-level updraft16,17, lower relative humidity16, stronger stratification and wind shear18, or higher saturation deficit in a warmer climate17. However, uncertainties remain as TC projections can depend on model characteristics and TC detection schemes19,20.

Liu et al.9 investigated potential changes in TC activity by CDR. Under the net-zero and negative CO2 emission scenarios, they found that TC activity in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres can be suppressed and enhanced, respectively, in the CO2 ramp-down (RD) period relative to the CO2 ramp-up (RU) period, despite identical CO2 concentrations. Such hemispherically different TC responses were attributed to contrasting changes in updraft and wind shear in the two hemispheres, due to a southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone arising from the hysteresis of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation5. However, their study primarily focused on the global-scale TC changes, giving less emphasis to regional TC responses in the sub-basin scale, such as landfalling TCs that can cause critical damage in coastal areas.

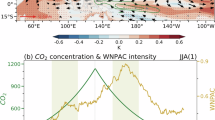

In this study, we extend the findings of Liu et al.9 by focusing on TC genesis in the western North Pacific (WNP) basin, where TCs most frequently occur and threaten densely populated regions of East Asia. A large-ensemble CDR experiment, where CO2 concentration is increased at the rate of 1% year−1 until quadrupled from the observed values in 1999/2000 (2001–2140) and then reduced at the same rate until it reaches the initial level (2141–2280), is conducted with CESM1.2 (Fig. 1; see Methods). This experiment shows an asymmetric change in WNP TCs to a symmetric CO2 pathway, characterized by suppressed TC genesis over the Philippine Sea during the RD period compared to the RU period, leading to fewer landfalling TCs in East Asia when CO2 concentration is reduced. This change is explained by changes in background flow in response to hysteresis in tropical sea surface temperature.

The periods of early RU (2001–2010), mid-RU (2056–2085), and mid-RD (2196–2225) are shaded in green, red, and blue, respectively. Horizontal dashed lines indicate the CO2 concentration of the present-day (PD) state (367 ppm, corresponding to the level observed in 1999/2000) and its doubled value (734 ppm).

Results

Validation of TC tracking algorithm and model

Figure 2a, c show the warm-season (July–September) TC genesis in the WNP region for observation and low-resolution reanalysis (1.5° × 1.5°), respectively, based on the Gibson2023 TC tracker (see Methods). TC genesis in reanalysis (Fig. 2c) shows a significant pattern correlation of 0.96 (p < 0.05) with observation within 5–30°N, indicating that TC genesis can be qualitatively reproduced with reanalysis. The seasonal cycle of WNP TC genesis is also well captured by the reanalysis (not shown), although its peak (4.8 TCs month−1 in August) and the annual number of TCs (24.1 TCs year−1) are slightly lower than the observation (5.6 TCs month−1 in August, and 26.9 TCs year−1, respectively). Track matching analysis gives a probability of detection (POD) of 75.35% and a false alarm rate (FAR) of 10.60% in the WNP basin (see Methods), a slightly inferior but comparable performance with popular TC trackers in the literature21. This suggests that the TC tracker used in this study successfully captures the majority of the observed TC tracks. Figure 2b, d compare the warm-season WNP TC track density in observation and reanalysis. Similar to the TC genesis, TC track density is qualitatively well reproduced by the reanalysis with a pattern correlation of 0.96 (p < 0.05) within 5–50°N.

Climatological distribution of WNP TC genesis (left) and track density (right) in (a, b) IBTrACS during 1980–2019, (c, d) ERA5 during 1980–2019, and (e, f) CESM1.2 during the early RU period (2001–2010). All variables have units of the number of TCs per month per 5° spherical cap (~106 km2). In (e, f), 28 ensemble members are used, generating 280 year (10 years × 28) data. Only the TC peak season from July to September is analyzed.

These results suggest that, although the Gibson2023 TC tracker utilizes only sea level pressure and two-level wind data, it can qualitatively capture the observed WNP TC genesis and track density from reanalysis data whose resolution is comparable to the model used in this study. Keeping the limitation in mind, the tracking scheme is applied to the CDR experiment. Figure 2e, f illustrate the genesis and track density of WNP TCs in CESM1.2 during the early RU period (2001–2010). Compared to the observation (Fig. 2a) and reanalysis (Fig. 2c), the model’s TC genesis (Fig. 2e) is significantly underestimated. However, the model qualitatively reproduces the spatial distribution of TC genesis, as indicated by a significant pattern correlation with the observation (0.90) and reanalysis (0.92) in 5–30°N. Similarly, the maximum TC track density in the model is only 0.85 TCs month−1, which is an underestimation of 49.90% compared to the observation (1.69 TCs month−1) and 53.98% compared to the reanalysis (1.84 TCs month−1); yet its spatial distribution exhibits a high pattern correlation of 0.91 with both the observation and reanalysis. The peak of the seasonal cycle of WNP TCs in the model (3.0 TCs month−1 in October) is also lower than and lags behind the observation (5.6 TCs month−1 in August) (not shown). As a result, the model generates fewer TCs yearly (15.6 TCs year−1) compared to the observation (26.9 TCs year−1). Nevertheless, the model qualitatively well reproduces the seasonal cycle of the WNP TCs (r = 0.84, p < 0.05).

The systematic underestimation of TCs may be attributable to the model’s low resolution; for instance, low-resolution CAM5.1 underestimates the number of global TCs by tenfold compared with its high-resolution counterpart22. It may also be caused by model configuration, as the high-resolution simulation also underestimates WNP TC activity during its peak season16. Despite its limitations, the model qualitatively captures the observed spatial distribution of WNP TCs, evidenced by a high spatial correlation with observation (≥0.90), which suggests that the response of WNP TCs to CO2 changes can be assessed using the CDR experiment at least in the qualitative sense.

It should be noted that WNP TC genesis and track density show a large spread among ensembles. The ensemble member with the highest WNP TC genesis maximum (0.63 TCs month−1; 12.69% lower than observation) better reproduces the TC genesis in the observation (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the ensemble member with the lowest value shows the WNP TC genesis maximum of only 0.33 TCs month−1 (54.48% lower than observation). Such a large spread (0.33–0.63 TCs month−1; 0.30 TCs month−1 difference) moderately reflects the decadal variability of WNP TCs in the observation (1.27–1.67 TCs month−1; 0.40 TCs month−1 difference) and reanalysis (1.20–1.80 TCs month−1; 0.60 TCs month−1 difference). The interquartile ranges of warm-season WNP TC genesis maximum and WNP TC count from the model ensembles (0.13 TCs month−1 and 1.13 TCs year−1) are also comparable to those obtained by bootstrapping from the observation (0.13 TCs month−1 and 1.30 TCs year−1) and reanalysis (0.17 TCs month−1 and 1.40 TCs year−1) (Supplementary Fig. 2). This suggests that the model ensembles reasonably reflect the internal variability of WNP TC genesis, and hence a robust climate change signal can be deduced from their ensemble mean.

Response of WNP TCs to CO2 changes

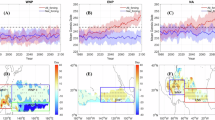

Figure 3a–d illustrate the warm-season WNP TC genesis and track density in the mid-RU (2056–2085) and mid-RD (2196–2225) periods. The WNP TC genesis maximum near the Philippine Sea becomes less pronounced in the mid-RU period (0.30 TCs month−1) than in the early RU period (0.36 TCs month−1) (compare Figs. 3a and 2e). A southeastward extension of TC genesis in the mid-RU period is also observed, as explicitly shown in Fig. 3e. Correspondingly, TC track density becomes enhanced over the eastern part of WNP (Fig. 3f), with increasing warm-season TCs from 6.3 TCs year−1 in the early RU period to 6.9 TCs year−1 in the mid-RU period. A qualitatively similar result has been reported in a global warming experiment with high-resolution CESM123. Such a southeastward shift and local enhancement of TC activity in the tropical WNP, however, deviate from previous studies that have reported a poleward migration and suppression of TC activity in a warmer climate15,20.

a–d Same as Fig. 2a, b but for (a, b) mid-RU and (c, d) mid-RD periods. Contours in (e–h) illustrate differences between (e–f) mid-RU and early RU periods and (g, h) mid-RD and mid-RU periods. Shadings in (e–h) denote statistically significant differences at the 95% confidence level, based on the two-tailed Student’s t-test. The blue box in (g) (15–27.5°N, 105–170°E) denotes the region with significant TC genesis decrease from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods. Only the TC peak season from July to September is analyzed.

The lower TC genesis maximum and track density are also observed in the mid-RD period (Fig. 3c, d). When comparing with the mid-RU period (Fig. 3a, b), it is noticeable that even though the two periods have identical CO2 concentrations, TC genesis and track density are not identical. In the mid-RD period, they are slightly lower near the Philippines and higher over the southeast part of WNP and in the vicinity of Japan. This difference is more clearly shown in Fig. 3g, h, where a statistically significant difference between the two periods is displayed. TC genesis becomes more vibrant near the central North Pacific (2.5–15°N, 150–180°E). In contrast, TC genesis over the Philippine Sea (PS) (15–27.5°N, 105–170°E; blue box in Fig. 3g) is suppressed in the mid-RD period, which leads to reduced TC track density along the east coast of East Asia, indicating fewer landfalling TCs. As a whole, the number of warm-season WNP TCs shows a statistically insignificant decrease from the mid-RU (6.9 TCs year−1) to mid-RD (6.8 TCs year−1) periods.

To confirm the robustness of these findings, the results of TRACK and TC downscaling methods are also examined (see Methods). The TRACK method yields nearly identical results to the Gibson2023 TC tracker (compare Figs. 3g and 4a). However, the TC downscaling method depicts a strong suppression of TC activity over the entire WNP domain (Fig. 4b). Liu et al.9 also suggested a basin-wide decrease in WNP TC genesis from the RU to RD periods; a slight increase in TC genesis over the central Pacific was found but confined to a small region near deep tropics and thus was not analyzed in their study. These results indicate that a decline in TC genesis over the PS from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods is robust to the model experiment and logistics, whereas TC response over the tropical WNP is sensitive to the choice of TC tracking methods and model experiments.

Same as Fig. 3g but when (a) TRACK and (b) TC downscaling methods are applied. Note that the color scale in (b) is three times larger than that in (a).

To investigate why TC genesis is less favorable in the mid-RD period than in the mid-RU period over the PS, we examine TC genesis changes and their relationship with large-scale environment changes using the dynamic genesis potential index (DGPI; Eq. 2 in Methods). As illustrated in Fig. 5, DGPI pattern closely follows the TC genesis pattern over the WNP both in the mid-RU (Fig. 5a) and mid-RD periods (Fig. 5c). This can also be manifested by statistically significant (p < 0.05) pattern correlations in 5–50°N (r = 0.86 for the mid-RU period and 0.90 for the mid-RD period). The hysteresis changes in DGPI and TC genesis between the two periods are also generally consistent, reaching a correlation of 0.91 and both decreasing over the PS region. This result indicates that DGPI is closely associated with TC genesis24,25 and can explain the asymmetric change in TC genesis in response to the symmetric CO2 pathway.

a, c, e Climatology of DGPI (shading) and TC genesis (# TC month−1 (5° spherical cap)−1, contour; same as Fig. 3a, c, g) in the WNP region during (a) mid-RU and (c) mid-RD, and (e) differences between the two periods. The spatial pattern correlation between DGPI and TC genesis is indicated in the upper right corner of each panel, with an asterisk denoting statistically significant value at the 95% confidence level according to the two-tailed Student’s t-test. g Linearly reconstructed DGPI change (Eq. 3; shading and contour) and contributions from (b) low-level absolute vorticity, (d) mid-level shear vorticity, (f) mid-level pressure velocity, and (h) vertical wind shear changes. Only statistically significant changes at the 95% confidence level, based on the two-tailed Student’s t-test, are illustrated. The blue box (15–27.5°N, 105–170°E) in (b) and (d–h), same to the one in Fig. 3g, denotes the region with a notable decrease in TC genesis. Dotted grid points mark statistically significant changes in TC genesis over the ocean within the boxed region. Only the TC peak season from July to September is analyzed.

The linearly approximated DGPI change (Eq. 3 in Methods; Fig. 5g) well captures the actual DGPI change (Fig. 5e). This indicates that linear approximation works reasonably well and can be used to diagnose the predominant contributor to the DGPI change. Figure 5b, d, f, h illustrate the changes in DGPI driven by each of its components. The DGPI decrease in the PS region is dominated by changes in mid-level ascent (Fig. 5f) and shear vorticity (Fig. 5d). Absolute vorticity displays a similar pattern to shear vorticity albeit with a smaller magnitude (Fig. 5b). Vertical wind shear tends to reduce DGPI offshore and enhance it in the open ocean but only contributes to a minor extent (Fig. 5h). Overall, it can be concluded that vertical velocity, shear vorticity, and absolute vorticity play key roles in changing DGPI and, consequently, TC genesis change over the PS.

Similar results are found for Emanuel-Nolan GPI (ENGPI; Eq. 4 in Methods), with a significant pattern correlation above 0.90 with TC genesis (Fig. 6a, c). The hysteresis changes in ENGPI and TC genesis from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods are also highly correlated, with a pattern correlation of 0.73 (Fig. 6e). This result indicates robust changes in the atmospheric environment over the PS that hinder TC genesis in the mid-RD period. The decrease in ENGPI over the PS primarily originates from a change in mid-level relative humidity (Fig. 6f), with low-level absolute vorticity playing a secondary role (Fig. 6b). The positive and negative changes in ENGPI by wind shear (Fig. 6h) are more pronounced than those in DGPI (Fig. 5h); however, the cancellation of the two results in a negligible net contribution to ENGPI decrease over the PS. Potential intensity contributes least to the ENGPI change (Fig. 6d). Figure 6 points out relative humidity change, followed by absolute vorticity change, as the main drivers of suppressing ENGPI over the PS from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods. These results are consistent with DGPI decomposition, since relative humidity is closely associated with vertical motion as shown later (Fig. 8e, g).

a, c, e Same as Fig. 5a, c, e but with ENGPI shown as shading. g Same as Fig. 5g but for linearly reconstructed ENGPI change (Eq. 6). b, d, f, h Same as Fig. 5b, d, f, h but for contributions from (b) low-level absolute vorticity, (d) potential intensity, (f) mid-level relative humidity, and (h) vertical wind shear changes.

The relative role of each component of DGPI and ENGPI over the PS is summarized in Fig. 7. To focus on significant TC genesis changes, only ocean grid points with significant TC genesis changes are considered in the analysis (blue dots in Figs. 5 and 6). As shown in Figs. 5e and 6e, changes in TC genesis, DGPI, and ENGPI are all consistent with each other (dark gray bars in Fig. 7). The linearly approximated DGPI and ENGPI changes are in good agreement with their actual changes (light gray bars in Fig. 7), leaving only a small residual (white bars in Fig. 7). Decomposition of DGPI change reveals that vertical velocity, shear vorticity, and absolute vorticity contribute 45.89%, 32.88%, and 20.15%, respectively, to the decrease in the linearly approximated DGPI in the PS region (blue, green, and red bars in Fig. 7a, respectively). The linearly approximated ENGPI change is dominated by the relative humidity term, which accounts for 78.12% of the change, with absolute vorticity contributing 26.10% (Fig. 7b).

DGPI (Fig. 5) is used for the top panel, while ENGPI (Fig. 6) is shown in the bottom panel. Ensemble mean differences of TC genesis (# TC month−1 (5° spherical cap)−1; left y-axis) and empirical GPI (right y-axis) between the mid-RD and mid-RU periods, averaged over the Philippine Sea (blue box in Figs. 5e and 6e), are shown as gray bars. Light gray bars represent linearly reconstructed GPI changes, and the residuals (or linearization errors) are indicated by white bars. The contribution of low-level absolute vorticity and vertical wind shear are displayed as red and magenta bars, respectively. Green bars show the contribution from (a) mid-level shear vorticity or (b) potential intensity, while blue bars indicate the contribution from (a) mid-level pressure velocity or (b) relative humidity. Error bars indicate the ensemble spread estimated as the standard deviation. Percentage values above or below each bar denote the relative contribution (%) to linearly reconstructed empirical GPI changes. Only the TC peak season from July to September is analyzed.

These results suggest that suppression of TC genesis over the PS in the mid-RD period compared to the mid-RU period is likely caused by large-scale environment changes, which are characterized by enhanced anticyclonic circulation over the PS (later referred to as the WNP anomalous anticyclone) and associated downward motion and reduced relative humidity over the PS in the mid-RD period.

WNP TC activities are typically influenced by large-scale circulations such as the monsoon trough (MT), WNP subtropical high (WNPSH), tropical upper-tropospheric trough (TUTT), and South Asian High. A significant portion of WNP TCs form in the MT, the region where monsoon westerlies meet the tropical easterlies, as it provides favorable conditions for TC genesis, such as cyclonic vorticity, high humidity, and weak easterly wind shear (e.g., refs. 26,27). In the subtropics, WNPSH influences WNP TC activity by modulating steering flow and providing unfavorable conditions for TC formation (e.g., ref. 28). TUTT, an upper-level trough that extends from ~35°N in the eastern North Pacific to ~15°N in the western North Pacific29, can limit eastward extension of WNP TC activity through strong wind shear on its southern flank as well as subsidence and low relative humidity to the east of the trough30. Its eastward shift is associated with more vigorous TC formation in the eastern part of the WNP basin30. WNP TC activity is also influenced by South Asian High, an upper-level anticyclonic circulation covering the South Asian continent during boreal summer, as it modulates vertical motion and low-level circulation in South Asia (e.g., ref. 31).

Figure 8 shows changes in the large-scale environment from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods. To be compared with Figs. 5 and 6, the PS domain is indicated with the blue box in each panel. The mid-RD period exhibits stronger cyclonic circulation over the tropical central-eastern Pacific (red shading in Fig. 8b) and anticyclonic circulation over the subtropical WNP (boxed in Fig. 8b) than the mid-RU period. The latter, which is responsible for reduced absolute vorticity, shear vorticity, upward motion, and humidity in Figs. 5 and 6, is referred to as the WNP anomalous anticyclone (WNPAC). The development of WNPAC indicates a westward extension of the WNPSH (red contour in the boxed region in Fig. 8d) and a westward shift of the MT (red contour in the boxed region in Fig. 8b). WNPAC is also evident in the mid-troposphere (Fig. 8f), with subsidence (Fig. 8e) and reduced humidity (Fig. 8g). TUTT also slightly shifts eastward (red contour in the boxed region in Fig. 8c), resulting in a stronger vertical wind shear on the southeastern part of WNP. The vertical wind shear change, however, plays a minor role in WNP TC suppression, as evidenced in the empirical GPI analyses (Fig. 7). Separate examination of large-scale environment changes in the mid-RU and mid-RD periods with respect to the early RU period also gives consistent results (Supplementary Text 1 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

Shadings denote differences in (a) SST (K), (b) 850 hPa relative vorticity (10−5 s−1), (c) vertical wind shear (m s−1), (d) sign-reversed 500 hPa geopotential height (m), (e) sign-reversed 500-hPa pressure velocity (10−2 Pa s−1), (f) sign-reversed shear vorticity (10−6 s−1), and (g) 600 hPa relative humidity (%). In (b), (d), and (f), red and blue shadings signify cyclonic and anticyclonic circulation differences, respectively, in the mid-RD period relative to the mid-RU period. In (e), red and blue colors indicate enhanced and suppressed convection, respectively, in the mid-RD period compared to the mid-RU period. Vectors show (b) 850 hPa and (c) 200 hPa wind differences between the two periods. Only statistically significant differences, according to a two-tailed Student’s t-test at the 95% confidence level, are shaded. Black contours in (a) and (e–g) indicate the mid-RU climatology of corresponding variables. Black and red contours are the zero isolines in the mid-RU and mid-RD periods, respectively, for (b) 850-hPa zonal wind (m s−1) which roughly represent MT, (c) 200 hPa zonal wind (m s−1) to indicate TUTT, and (d) 500-hPa eddy geopotential height (m), defined as deviation from the regional average of 0–40°N and 180°W–180°E58, to delineate the WNPSH boundary. The blue box in each panel defines the Philippine Sea (15–27.5°N, 105–170°E), where WNP TC genesis significantly decreased from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods. Values over land are masked for the purpose of visualization. Only the TC peak season from July to September is analyzed.

The WNPAC, corresponding to the westward withdrawal of the MT and westward extension and intensification of WNPSH, makes the local environmental conditions less conducive to TC genesis. This may explain the suppressed WNP TC genesis over the PS in the mid-RD period compared to the mid-RU period (Fig. 3g). Note that the blue box in Fig. 8 is identical to that in Figs. 3g, 5 and 6.

What drives the prominent WNPAC in Fig. 8b? It might be partly induced by SST change. Under the eastern Pacific El Niño-like SST condition (Fig. 8a), cyclonic circulation develops in the lower troposphere on the south of the WNPAC (south of the boxed region in Fig. 8b) as a Gill-type Rossby wave response32. The northeasterly on its northwestern flank can contribute to the development of WNPAC. WNPAC can also be organized by Rossby wave response to the apparent heat sink in the subtropical eastern North Pacific. As shown in Fig. 8e, enhanced upward motion in the equatorial eastern Pacific (red shading) is paired with enhanced downward motion in the subtropical eastern Pacific (blue shading in the tropical Pacific), possibly due to southward migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)5. The apparent heat sink associated with the latter (Supplementary Fig. 5) can contribute to the WNPAC through a Gill-type response.

The WNPAC is also likely influenced by atmospheric-ocean feedback in the tropical Indian Ocean and WNP28. In particular, a warm Indian Ocean (Fig. 8a) can induce a Gill-type Kelvin wave response32 that contributes to the maintenance of WNPAC. This Indian Ocean warming can be related to the Indo-western Pacific Ocean Capacitor (IPOC) effect in the El Niño decaying summer33,34. During the El Niño developing winter, the weakened Walker circulation induces anticyclonic circulation over the South Indian Ocean (Supplementary Fig. 7). This induces downwelling ocean Rossby waves, which deepen the thermocline and anchor warming in the South Indian Ocean until the following summer. The persistent warming weakens the monsoon southwesterly over the North Indian Ocean by inducing a northeasterly flow. This reduces evaporation and results in warming of the North Indian Ocean. The Kelvin wave emanating from this Indian Ocean warming induces northeasterly off the equator (Supplementary Fig. 7) and divergence in the subtropics, contributing to the maintenance of WNPAC during the El Niño decaying summer (e.g., refs. 35,36). Consistent results are found in Fig. 9. While the eastern Pacific SST difference peaks in autumn and winter (Fig. 9a, d), the South Indian Ocean SST difference develops in spring and summer (Fig. 9b), followed by the North Indian Ocean SST difference in summer when WNPAC is most clearly defined over the PS (Fig. 9c). This is suggestive of the IPOC effect of El Niño-like SST and circulation changes in the mid-RD summer.

SST (shading; unit: K) and 850 hPa relative vorticity (contour; unit: 10−5 s−1) for (a) January–March, (b) April–June, (c) July–September, and (d) October–December. Only statistically significant changes at the 95% confidence level according to a two-tailed Student’s t-test are visualized over the oceans.

The WNPAC can be reinforced by local feedback. For example, the WNPAC can promote evaporation cooling by strengthening trade winds37, which suppresses convection over the PS and further strengthens WNPAC. The strengthened trade winds on the southern flank of WNPAC also result in negative moist static energy advection and suppressed convection over the PS (Ham et al.38; Fig. 10a, b). A linear decomposition analysis (see Methods) suggests that the majority (51.57%) of negative moist static energy advection over the PS comes from the advection of climatological moist static energy in the mid-RU period by the wind difference between the mid-RD and mid-RU periods (Fig. 10c). This suggests that anomalous northeasterly on the southern flank of WNPAC significantly contributes to subsidence over the PS, which further reinforces WNPAC through positive feedback.

Differences in (a) sign-reversed 500-hPa pressure velocity (10−2 Pa s−1) (same as Fig. 8e but with different contour levels), and (b) column-integrated horizontal moist static energy advection (shading and contour; unit: W m−2) and column-integrated horizontal wind (vector; unit: ×104 kg m−1 s−1). c Changes in vertical motion (gray bar; left y-axis), moist static energy advection (red bar; right y-axis), and components of moist static energy advection changes (orange, yellow, green, and white bars; right y-axis) averaged over the Philippine Sea (blue boxes in Fig. 10a, b). Shown components are the advection of climatological moist static energy by wind difference (orange bar), advection of moist static energy difference by climatological wind (yellow bar), nonlinear term (green bar), and residual (white bar) (Eq. 9). Here, the “climatology” and “difference” refer to the mid-RU climatology and the difference between the mid-RD and mid-RU periods. “Column-integrated” indicates mass-weighted integration from 1000 to 100 hPa levels. The bar denotes the ensemble mean changes, while the error bars indicate the ensemble spread estimated as a standard deviation. The numbers below each bar represent the relative contribution of each term to the total moist static energy advection changes. Only the TC peak season from July to September is analyzed.

Based on these results, we hypothesize that the enhanced anticyclonic circulation over the PS (i.e., WNPAC) in the mid-RD period compared to the mid-RU period can be related to multiple atmospheric-oceanic systems (Fig. 11). The El Niño-like SST difference in the equatorial eastern Pacific can induce cyclonic circulation over the central Pacific and WNPAC as a Rossby wave response. The suppressed convection over the off-equatorial eastern North Pacific, presumably linked to the southward shift in ITCZ, may also contribute to the WNPAC through a Rossby wave response. The Indian Ocean warming, possibly related to the IPOC effect of El Niño-like SST difference, can also induce Kelvin wave response and result in WNPAC. Lastly, the anticyclonic anomaly can be maintained or reinforced by local feedbacks through evaporation and moist static energy advection (Fig. 11). However, our hypothesis lacks quantitative evidence. To determine atmospheric circulation response to SST changes and quantify its contributions to WNPAC and WNP TC suppression, a series of model experiments, where SST is systematically varied, are required.

Black arrows represent low-level atmospheric circulations. Red shadings indicate sea surface warming, while blue shadings indicate atmospheric cooling or suppressed convection. Acronyms include: eastern Pacific (EP), North Indian Ocean (NIO), anomalous cyclonic circulation (ACC), and western North Pacific anomalous anticyclonic circulation (WNPAC).

Summary and discussion

In this study, we investigated whether WNP TCs respond symmetrically to the symmetric CO2 change. When comparing the mid-RU and mid-RD periods with identical CO2 concentrations, a robust suppression in TC genesis and track density over the Philippine Sea (PS) region is found in the latter period. This result suggests that reducing the elevated CO2 concentration may not immediately recover the large-scale environments and TC activities in the WNP.

Empirical GPI analyses reveal that less TC genesis over the PS in the mid-RD period is closely associated with reduced absolute vorticity, shear vorticity, and mid-level ascending motion. The lower relative humidity, connected with the sinking motion, also hinders the TC genesis. These changes are due to the development of WNP anomalous anticyclone (WNPAC), corresponding to the westward expansion of the WNP subtropical high and the westward shift of the monsoon trough in the mid-RD period, likely driven by tropical SST and convection changes. Specifically, eastern Pacific El Niño-like warming, suppressed convection over the eastern North Pacific north of El Niño-like SST warming, and Indian Ocean SST warming are likely responsible for the formation of WNPAC in the mid-RD period compared to the mid-RU period.

Although we have mainly compared WNP TC activities and large-scale environments in the mid-RU and mid-RD periods, the overall results are not sensitive to the choice of analysis period. In Supplementary Fig. 6, WNP TCs are tracked during the RU and RD sub-periods centered around the time of 2.5 × CO2 and 3 × CO2. WNP TCs in the last 10 years of the RD stage (late RD period) are also compared with those in the early RU period. All sub-periods show a robust suppression of WNP TC genesis over the PS and its enhancement over the southeastern part of the WNP domain. Consistent results are also found when TRACK and TC downscaling algorithms are used. This result suggests that the suppression of WNP TC genesis over the PS from the RU to RD periods is a robust feature observed regardless of the choice of analysis periods and TC trackers.

The present study highlights the nonlinear response of WNP TCs to climate forcings and its relationship with large-scale environment changes in the large ensemble CDR experiment. However, the model used in this study underestimates warm-season WNP TC activities with a lagged peak in the seasonal cycle. These biases may originate not only from the low resolution but also from the internal structure or formulations of CESM1.2, as similar biases were found when a higher-resolution model was used16. They may undermine the credibility of the results. To exclude a model-dependent uncertainty and obtain a more reliable and robust conclusion, the analysis may need to be repeated with multi-model large-ensemble CDR experiments in high resolution.

Methods

Reanalysis and observation datasets

We used the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) version 5 Reanalysis dataset (ERA539) for 40 years (1980–2019). Horizontal winds and sea level pressure (SLP) at 6 hourly intervals at a 1.5° × 1.5° spatial resolution are used to verify the performance of the TC tracker.

The TCs in the reanalysis and model are compared with TCs from the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS40) version 4 data for 40 years (1980–2019). IBTrACS contains TC track records from global meteorological agencies. Due to potential inconsistencies in recorded variables (e.g., wind speed) across agencies, careful post-processing is necessary. Here, we used the version of the IBTrACS dataset post-processed by Bourdin et al.21 as the reference.

CDR experiment

We used the Community Earth System Model version 1.2 (CESM1.241) to investigate the response of WNP TC genesis to CO2 increase and decrease (e.g., ref. 42). CESM1.2 is a comprehensive Earth system model with fully coupled atmospheric (Community Atmospheric Model version 5, CAM5), oceanic (Parallel Ocean Program version 2, POP2), land (Community Land Model version 4, CLM4), and sea ice (Community Ice Core version 4, CICE4) components. The atmospheric model has 30 vertical levels with a horizontal resolution of ~1° × 1° 43. The ocean model has 60 vertical layers. Its zonal grid spacing is about 1°, while its latitudinal grid spacing increases from 0.3° at the equator to 0.5° at the pole44.

The experiment is divided into four periods depending on the CO2 pathway42, with two specific periods analyzed in this study depicted in Fig. 1. After being initialized with a fixed CO2 level (367 ppm, which is the observed value in 1999/2000) for 900 years (present-day reference period, PD), CO2 concentration is subsequently ramped up at a constant rate of 1% per year for 140 years (2001–2140; ramp-up period, RU) until quadrupled (1468 ppm). It is then decreased at the same rate for another 140 years (2141–2280; ramp-down period, RD) until returning to the initial level. For each phase, we used 28 ensemble members, each initialized with different phases of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation during the PD period. For further details, refer to An et al.42.

In this study, TCs are tracked over the WNP region (100–180°E, 0–60°N) across three periods using an automated tracking algorithm, introduced in the following section. To validate the model’s performance, the climatology of TC genesis and track density during the early RU period (2001–2010) is compared with those of the observation and reanalysis. We note that the TC tracker cannot be applied to the PD period since the 6 hourly zonal wind at 200 hPa for this period is not archived. Therefore, the early RU period is used for validation. TC genesis during the mid-RU (2056–2085) and mid-RD (2196–2225) periods are then compared to identify asymmetric responses to the symmetric CO2 pathway. These mid-RU and mid-RD periods are selected as 30 year subperiods within the RU and RD periods, centered around the time of CO2 doubling with respect to the PD period (Fig. 1).

TC tracking

The primary TC tracking algorithm used in this study is based on Gibson et al. (2023)’s45 method (hereafter referred to as the “Gibson2023” TC tracker), with an addition of wind speed criterion to filter out extratropical cyclones17,46. Using the TempestExtremes version 2.1 algorithm47, it detects cyclones as the local minima of sea level pressure (SLP), where SLP increases by at least 2.0 hPa over a 6.0° great circle distance from the cyclone center. Cyclones of adjacent 6 hourly timesteps are then stitched together to form tracks. During tracking, cyclones are required to satisfy stronger wind speeds at 850 hPa (WS850) than at 200 hPa (WS200) for at least one consecutive day over the ocean. Here, WS850 and WS200 are defined as the maximum wind speed within a 4.0° radius from the cyclone center. Finally, tracks originating from the tropical (5–30°N) ocean are considered as TC tracks. We note that the 4.0° radius for identifying maximum wind speed is subjectively chosen to give a reasonable number of global TCs (78.65 TCs year−1). A 6.0° radius similar to previous studies (e.g., ref. 48) results in a significant underestimation of TCs (57.75 TCs year−1), because the upper-level jet speed is sometimes misidentified as TC’s upper-level wind speed maximum even when TC is distant from it. Conversely, a 2.0° radius slightly overestimates the global TC count (94.62 TCs year−1) compared to the observation (87.75 TCs year−1).

To test the robustness of TC response, two additional algorithms are used: the modified TRACK algorithm48 and the TC downscaling algorithm49. TRACK algorithm48 uses filtered vorticity to detect and track TCs. In this study, we modified some of its thresholds and criteria due to a limited number of variables available in the CDR experiment. TRACK first detects the local maxima of 850-hPa relative vorticity (ζ), spectrally truncated at T63 resolution (~180 km), above 2.0 cyclonic vorticity unit (CVU; 10−5 s−1) as TC candidates. TC candidates are then stitched into tracks, and tracks lasting less than a day are discarded. Finally, TC candidates with a strong low-level vortex (ζ850 ≥ 3.5 CVU), warm core (ζ850 − ζ200 ≥ 3.5 CVU), barotropic vertical structure (distance between vorticity centers at 850- and 200 hPa levels ≤ 10°), low-level wind maximum (WS850 ≥ WS200) over the ocean at least one day consecutively and initiating from the tropical (5–30°N) ocean are identified as TC tracks. Here, WS850 and WS200 are defined as wind speed maxima within 6.0° from the vortex centers at 850 and 200 hPa, respectively, similar to the definition of TC wind speed in Hodges et al.48. Unlike previous studies using vorticities at 500 hPa and other mid-tropospheric levels48,50, vorticities of only two vertical levels (850 and 200 hPa) are used in the present study as those at other levels were not archived at 6-hourly intervals. To allow a similar level of vertical tilt of TCs, the maximum distance between low- and upper-level vortex centers is set to 10°, twice as large as in the aforementioned studies. Furthermore, the wind speed criterion is adopted to reduce the misidentification of extratropical cyclones as TCs21,48.

A Python version of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology TC downscaling model51 is also used49, again with adjustments considering variables provided in the CDR experiment. First, synthetic winds are generated based on monthly statistics of daily winds at 200 and 850 hPa. Seeds, or weak vortices with a surface wind speed of 5 m s−1, are randomly spread in space and time, which are then advected by the synthetic steering flow and beta drift. At each point, the FAST intensity model52 updates the seed’s wind speed and moisture variable using synthetic wind shear and monthly thermodynamic variables. Seeds whose wind speed does not reach 7 m s−1 within two days are discarded. If their wind speed successfully intensifies to 18 m s−1, they are regarded as TCs and tracked until dissipation. This process is repeated until a predefined number of TCs is obtained, which is set as 150 WNP TCs per year, around sixfold of observation (~27 WNP TCs per year). Although this number is smaller than that in previous downscaling studies (e.g., ~14,000 in Lin et al.49), hence compromising the reliability of our result, such weakness is partially resolved by applying the algorithm to a large number of ensembles.

For the downscaling method, TC statistics are adjusted as follows. Assuming that the number of seeds changes little in time, TC count, genesis, and track density in each period of the model experiment (early RU, mid-RU, and mid-RD) are rescaled by a ratio of the number of seeds in the early RU period to that in other periods. For instance, if the number of seeds required to generate 150 TCs in the early RU and mid-RU periods is 1,000 and 1,500, respectively, the number of TCs in the mid-RU period is rescaled by 10/15 (i.e., 100 TCs). Hence, in essence, we are comparing the seed survival rate in each period.

Validation of TC tracking

The TC trackers are validated by comparing TC climatological features, such as genesis and track density, derived from reanalysis with observation. At each grid point, TC genesis and track density are calculated as the number of TCs that form or exist within a 555 km radius, which is similar to the radius used in previous studies14,50. Counting the number of TCs within a boxed region (e.g., 5° × 5° as in Chu et al.16 and Kim et al.18) centered around each point gives qualitatively consistent results (not shown). Considering the resolutions of reanalysis (1.5° × 1.5°) and model (~1°), these properties are calculated at the 1.5° × 1.5° resolution.

A track-matching method21 is also utilized to quantify each TC tracker’s detection skill. Specifically, the TC track point detected in reanalysis at each time step is associated with that in observation if they are closer than 300 km. If a reanalysis TC track fails to match with any observational TC track throughout its lifetime, it is considered a “False Alarm” (FA). If a reanalysis TC track is matched with at least a subset of one or more observational TC tracks, the one with the longest match is chosen as its best pair. Finally, if the observed TC track is paired with multiple reanalysis TC tracks, these reanalysis tracks are merged into a single one. Using this track matching, the probability of detection (POD) and the false alarm rate (FAR) for each TC tracking algorithm are quantified as follows:

where H (Hits) and M (Misses) are the observed TC tracks that are matched or unmatched with reanalysis TC tracks, respectively. Note that this track-matching process is not applied to the downscaling method since it generates synthetic TC tracks using a synthetic wind field.

Empirical genesis potential index

To explain the differences in TC genesis between the mid-RD and mid-RU periods, the dynamic genesis potential index (DGPI) is analyzed24. DGPI is known to reliably reproduce variations in TC genesis across basins and time scales24,25. Its formulation is given below:

Here, ζa850 is the absolute vorticity at 850 hPa (s−1), ω500 is the 500 hPa pressure velocity (Pa s−1), du500/dy is the shear vorticity of 500 hPa zonal wind (hereafter, “shear vorticity”), and Vs is the vertical wind shear between 200- and 850 hPa levels (m s−1).

Following previous studies24,53, changes in DGPI are approximated as a linear sum of the terms related to each of its components to identify the driving factors behind DGPI and TC genesis changes:

where ∆ represents differences between the two periods (mid-RD minus mid-RU), and the overbar indicates the climatology in the mid-RU period.

To test the sensitivity of the results to the choice of empirical genesis potential index, we also evaluated the genesis potential index of Emanuel and Nolan54 (ENGPI):

ENGPI shares two dynamic variables (ζa850, Vs) with DGPI but has two thermodynamic variables, RH600 and PI, in place of ω500 and du500/dy. RH600 is the 600 hPa relative humidity (%), and PI represents the potential intensity (m s−1), the theoretical upper limit of the maximum surface wind speed of a TC55,56, which is calculated as below55:

where Ck is the surface enthalpy exchange coefficient, CD is the surface momentum exchange coefficient, Ts is sea surface temperature, and To is the TC outflow temperature. h0* and h* represent the saturation moist static energy at the sea surface and in the free atmosphere, respectively. A high PI indicates a significant release of sensible and latent heats at the sea surface and frictional heating in the boundary layer55, which is favorable for the initiation or growth of convection and thus TC. PI is calculated using the tcpyPI Python module57.

Changes in ENGPI from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods are also decomposed in a likewise manner to DGPI:

For analysis of large-scale background field (Eqs. 2–6), monthly temperature, horizontal winds, pressure velocity, and specific humidity interpolated to pressure levels from 1000 to 50 hPa at 50 hPa interval, as well as sea level pressure and sea surface temperature, are used at a 1.5° × 1.5° resolution.

Moist static energy

To understand changes in the large-scale circulation and convection over the PS from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods, changes in the moist static energy and its horizontal advection are analyzed. Moist static energy is defined as below:

where cp, T, L, q, and Φ are specific heat of air at constant pressure, air temperature, latent heat of evaporation, specific humidity, and geopotential, respectively. Using a simplified moist static energy budget equation and neglecting diabatic heating, vertical motion in the tropics can be approximated by the column-integrated horizontal advection of moist static energy38. Therefore, we compare the horizontal advection of moist static energy integrated from 1000 to 100 hPa (Eq. 8) in the mid-RU and mid-RD periods.

Here, v = (u, v) is the horizontal wind vector, g is gravitational acceleration, and m is moist static energy. Similar to the empirical GPI decomposition, changes in the column-integrated moist static energy advection from the mid-RU to mid-RD periods are decomposed into the following three terms:

In Eq. 9, the overbar indicates the mid-RU climatology (“climatology”), while the apostrophe indicates the difference between the mid-RD and mid-RU periods (“difference”). The first term on the right-hand side is the advection of climatological moist static energy by the horizontal wind change. The second term is the advection of moist static energy change by the climatological horizontal wind. The third term is the nonlinear term.

Statistical tests

Pearson’s correlation is used to indicate pattern consistency between two climatologies, such as spatial patterns of TC genesis or the seasonal cycle of TC counts. Its statistical significance is evaluated by a two-tailed Student’s t-test, assuming that each data point is independent and follows an identical normal distribution. When evaluating the statistical significance of differences between the mid-RD and mid-RU values at each point, we used a two-tailed Student’s t-test, considering each ensemble as an independent sample (n = 28) following an identical normal distribution.

Data availability

The post-processed IBTrACS dataset from 1980/81–2019 as well as codes for track matching by ref. 21 was downloaded from https://zenodo.org/records/6424432 (last access: 7 December 2024). The ERA5 reanalysis dataset is publicly accessible from the Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store (CDS, https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu, last access: 7 December 2024; ref. 39).

Code availability

The calculation of potential intensity was based on the tcpyPI Python module openly available at https://github.com/dgilford/tcpyPI (last access: 7 December 2024; ref. 57). Gibson2023 TC tracking was implemented using TempestExtremes which can be obtained from https://github.com/ClimateGlobalChange/tempestextremes (last access: 7 December 2024; ref. 47). Codes for the TC downscaling method were downloaded from https://github.com/linjonathan/tropical_cyclone_risk (last access: 7 December 2024; ref. 49). The key analysis codes and data are available upon reasonable request to the first author (yhs11088@snu.ac.kr).

References

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 3–32 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Global Warming Of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report On The Impacts Of Global Warming Of 1.5°C Above Pre-industrial Levels And Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, In The Context Of Strengthening The Global Response To The Threat Of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, And Efforts To Eradicate Poverty (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Keller, D. P. et al. The carbon dioxide removal model intercomparison project (CDRMIP): rationale and experimental protocol for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 1133–1160 (2018).

Jo, S.-Y. et al. Hysteresis behaviors in East Asian extreme precipitation frequency to CO2 pathway. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099814 (2022).

Kug, J.-S. et al. Hysteresis of the intertropical convergence zone to CO2 forcing. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 47–53 (2022).

Zhang, S., Qu, X., Huang, G. & Hu, P. Asymmetric response of South Asian summer monsoon rainfall in a carbon dioxide removal scenario. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 10 (2023).

Song, S.-Y. et al. Asymmetrical response of summer rainfall in East Asia to CO2 forcing. Sci. Bull. 67, 213–222 (2022).

Hwang, J. et al. Asymmetric hysteresis response of mid-latitude storm tracks to CO2 removal. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 496–503 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. Hemispheric asymmetric response of tropical cyclones to CO2 emission reduction. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 83 (2024).

Jing, R. et al. Global population profile of tropical cyclone exposure from 2002 to 2019. Nature 626, 549–554 (2024).

Jiang, H. & Zipser, E. J. Contribution of tropical cyclones to the global precipitation from eight seasons of TRMM data: Regional, seasonal, and interannual variations. J. Clim. 23, 1526–1543 (2010).

Kubota, H. & Wang, B. How much do tropical cyclones affect seasonal and interannual rainfall variability over the western North Pacific? J. Clim. 22, 5495–5510 (2009).

Chang, C.-P., Lei, Y., Sui, C.-H., Lin, X. & Ren, F. Tropical cyclone and extreme rainfall trends in East Asian summer monsoon since mid‐20th century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L18702 (2012).

Utsumi, N., Kim, H., Kanae, S. & Oki, T. Relative contributions of weather systems to mean and extreme global precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 152–167 (2017).

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: part II: projected response to anthropogenic warming. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E303–E322 (2020).

Chu, J.-E. et al. Reduced tropical cyclone densities and ocean effects due to anthropogenic greenhouse warming. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd5109 (2020).

Song, C., Park, S. & Shin, J. Tropical cyclone activities in warm climate with quadrupled CO2 concentration simulated by a new general circulation model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD032314 (2020).

Kim, H.-S. et al. Tropical cyclone simulation and response to CO2 doubling in the GFDL CM2. 5 high-resolution coupled climate model. J. Clim. 27, 8034–8054 (2014).

Horn, M. et al. Tracking scheme dependence of simulated tropical cyclone response to idealized climate simulations. J. Clim. 27, 9197–9213 (2014).

Tang, Y., Huangfu, J., Huang, R. & Chen, W. Simulation and projection of tropical cyclone activities over the western North Pacific by CMIP6 HighResMIP. J. Clim. 35, 7771–7794 (2022).

Bourdin, S., Fromang, S., Dulac, W., Cattiaux, J. & Chauvin, F. Intercomparison of four algorithms for detecting tropical cyclones using ERA5. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 6759–6786 (2022).

Wehner, M. F. et al. The effect of horizontal resolution on simulation quality in the community atmospheric model, CAM 5.1. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 6, 980–997 (2014).

van Westen, R. M., Dijkstra, H. A. & Bloemendaal, N. Mechanisms of tropical cyclone response under climate change in the community earth system model. Clim. Dyn. 61, 2269–2284 (2023).

Murakami, H. & Wang, B. Patterns and frequency of projected future tropical cyclone genesis are governed by dynamic effects. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 77 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Opposite skills of ENGPI and DGPI in depicting decadal variability of tropical cyclone genesis over the western North Pacific. J. Clim. 36, 8713–8721 (2023).

Wu, L., Wen, Z., Huang, R. & Wu, R. Possible linkage between the monsoon trough variability and the tropical cyclone activity over the western North Pacific. Mon. Weather Rev. 140, 140–150 (2012).

Zong, H. & Wu, L. Synoptic-scale influences on tropical cyclone formation within the western North Pacific monsoon trough. Mon. Weather Rev. 143, 3421–3433 (2015).

Wang, C. & Wang, B. Tropical cyclone predictability shaped by western Pacific subtropical high: Integration of trans-basin sea surface temperature effects. Clim. Dyn. 53, 2697–2714 (2019).

Sadler, J. C. A role of the tropical upper tropospheric trough in early season typhoon development. Mon. Weather Rev. 104, 1266–1278 (1976).

Wang, C. & Wu, L. Interannual shift of the tropical upper-tropospheric trough and its influence on tropical cyclone formation over the western North Pacific. J. Clim. 29, 4203–4211 (2016).

Zang, Y., Zhao, H., Klotzbach, P. J., Wang, C. & Cao, J. Relationship between the south Asian high and western north Pacific tropical cyclone genesis. Atmos. Res. 281, 106491 (2023).

Gill, A. E. Some simple solutions for heat‐induced tropical circulation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 106, 447–462 (1980).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Indo-western Pacific Ocean capacitor and coherent climate anomalies in post-ENSO summer: A review. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 33, 411–432 (2016).

Cai, W. et al. Pantropical climate interactions. Science 363, eaav4236 (2019).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Indian Ocean capacitor effect on Indo–western Pacific climate during the summer following El Niño. J. Clim. 22, 730–747 (2009).

Yang, J., Liu, Q., Xie, S.-P., Liu, Z. & Wu, L. Impact of the Indian Ocean SST basin mode on the Asian summer monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L02708 (2007).

Wang, B., Wu, R. & Fu, X. Pacific–East Asian teleconnection: how does ENSO affect East Asian climate? J. Clim. 13, 1517–1536 (2000).

Ham, Y.-G., Kug, J.-S. & Kang, I.-S. Role of moist energy advection in formulating anomalous Walker circulation associated with El Niño. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, D24105 (2007).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Knapp, K. R., Kruk, M. C., Levinson, D. H., Diamond, H. J. & Neumann, C. J. The international best track archive for climate stewardship (IBTrACS): unifying tropical cyclone data. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 91, 363–376 (2010).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

An, S.-I. et al. Global cooling hiatus driven by an AMOC overshoot in a carbon dioxide removal scenario. Earth’s Future 9, e2021EF002165 (2021).

Neale, R. B. et al. Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 5.0). NCAR Technical Note NCAR/TN-486+STR (National Center of Atmospheric Research, 2012).

Smith, R. et al. The parallel ocean program (POP) reference manual ocean component of the community climate system model (CCSM) and community earth system model (CESM). LAUR-01853 141, 1–140 (2010).

Gibson, P. B. et al. High‐resolution CCAM simulations over New Zealand and the South Pacific for the detection and attribution of weather extremes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2023JD038530 (2023).

Oouchi, K. et al. Tropical cyclone climatology in a global-warming climate as simulated in a 20 km-mesh global atmospheric model: frequency and wind intensity analyses. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 84, 259–276 (2006).

Ullrich, P. A. et al. TempestExtremes v2.1: a community framework for feature detection, tracking, and analysis in large datasets. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 5023–5048 (2021).

Hodges, K. I., Cobb, A. & Vidale, P. L. How well are tropical cyclones represented in reanalysis datasets? J. Clim. 30, 5243–5264 (2017).

Lin, J., Rousseau‐Rizzi, R., Lee, C.-Y. & Sobel, A. An open‐source, physics‐based, tropical cyclone downscaling model with intensity‐dependent steering. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 15, e2023MS003686 (2023).

Strachan, J., Vidale, P. L., Hodges, K., Roberts, M. & Demory, M.-E. Investigating global tropical cyclone activity with a hierarchy of AGCMs: the role of model resolution. J. Clim. 26, 133–152 (2013).

Emanuel, K., Sundararajan, R. & Williams, J. Hurricanes and global warming: results from downscaling IPCC AR4 simulations. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 89, 347–368 (2008).

Emanuel, K. A fast intensity simulator for tropical cyclone risk analysis. Natural Hazards 88, 779–796 (2017).

Li, Z., Yu, W., Li, T., Murty, V. S. N. & Tangang, F. Bimodal character of cyclone climatology in the Bay of Bengal modulated by monsoon seasonal cycle. J. Clim. 26, 1033–1046 (2013).

Emanuel, K. A. & Nolan, D. S. Tropical cyclone activity and the global climate system. In Proc. of 26th Conf. on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology, 240–241 (IEEE, 2004).

Bister, M. & Emanuel, K. A. Dissipative heating and hurricane intensity. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 65, 233–240 (1998).

Emanuel, K. A. Sensitivity of tropical cyclones to surface exchange coefficients and a revised steady-state model incorporating eye dynamics. J. Atmos. Sci. 52, 3969–3976 (1995).

Gilford, D. M. pyPI (v1.3): Tropical cyclone potential intensity calculations in Python. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 2351–2369 (2021).

Zhou, T. et al. Why the western Pacific subtropical high has extended westward since the late 1970s. J. Clim. 22, 2199–2215 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2023R1A2C3005607).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-W.S. conceived the study and guided the overall research. H.Y. conducted analysis, prepared figures, and wrote the first manuscript. J.L., H.-S.K., C.L., and J.-S.K. provided instructive suggestions for improving the methodologies. S.-W.S., J.L., H.-S.K., C.L., S.-I.A., J.-S.K., S.-.K.M., and S.-W.Y. gave constructive advice on the results and interpretation. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, H., Son, SW., Lee, J. et al. Asymmetric response of the Western North Pacific tropical cyclone genesis to symmetric CO2 pathway. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 208 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01087-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01087-9