Abstract

Anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are typically a mix of warmers/coolers and short-lived/long-lived species. This suite of emissions should be taken into account to drive better climate. We quantify 33 emitted species since 1750 from seven economic sectors and their impact on present-day warming. We then assess how today’s sectoral emissions impact future temperatures. Sectors that predominantly emit short-lived warmers drive half of today’s warming (~0.6 °C). However, their current-year emissions have a lesser impact on 100-year temperature projections due to proportionally lower longer-lived species. Sectoral emissions dominated by longer-lived warmers impact temperature for centuries – an impact which accumulates over time. However, shorter-lived climate coolers from these sectors mask ~50% of their present-day warming (~33% overall). This means actions necessary to reduce long-lived warming may temporarily increase near-term temperatures. Successfully limiting both near- and long-term warming requires considering this interplay and accelerating climate ambitions to offset any decline in coolers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anthropogenic emissions, and the climate forcing that many emitted substances ultimately generate, are the primary driver of climate change. The impacts of emissions vary along two fundamental axes—their timeline of impact from <1 to 1000+ years (either through their lifetime or through other climate forcers they influence) and their differential strengths, from strong cooling to strong warming effects1,2. As most emission sources produce a mix of gases and/or particles, and those species often interact in the atmosphere to generate multiple forcing pathways, the net impact of emissions mitigation strategies is the integration of changes to a suite of forcers. These forcers include both greenhouse gases (and their precursors) that predominantly absorb outgoing longwave radiation (i.e., Earth’s heat), and aerosols (and their precursors) that predominantly absorb or reflect incoming shortwave radiation (i.e., sunlight) and perturb cloud properties. Effective and optimal mitigation of climate change (limiting the warming rate, peak, and stabilization level3) and avoiding overshoot scenarios4 requires consideration of all climate forcers and their trends, magnitudes, signs, and timescales of impact. To date, there has been no detailed assessment as to how individual sectors are contributing to climate change today, given their accumulated emissions of a mix of warmers and coolers, and short-lived and long-lived species. This is essential to identifying the most effective mitigation strategies over different timescales.

While attention has primarily focused on reductions to carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, non-CO2 climate forcers, which are typically stronger warmers than CO2 on a kilogram-per-kilogram basis, account for more than half of current gross warming since preindustrial times (using either 1750 or 1850–1900 as a baseline2. The most prominent emitted warming species include methane (CH4), carbon monoxide (CO) and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs), nitrous oxide (N2O), halogenated compounds (HCs), and black carbon (BC) – all of which are greenhouse gases or greenhouse gas precursors except BC, which is an aerosol. However, human activities also emit climate forcers with net cooling effects, including sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), organic carbon (OC), and ammonia (NH3) – all of which are aerosol precursors, and NOx also affects greenhouse gas concentrations indirectly. It is important to note that while these are all the major emitted species driving anthropogenic climate change, there are additional climate forcers that are formed from these emissions but not directly emitted, including the greenhouse gas tropospheric ozone (from chemical reactions involving CH4, CO, NMVOCs, NOx) and the aerosols sulfate (SO4) and nitrate (NO3). The term ‘climate forcer’ is often used interchangeably to refer to both greenhouse gases/aerosols as well as their precursors, and therefore, to be consistent with previous and forthcoming literature, we adopt this terminology herein.

The climate effects from these emissions depend on their atmospheric lifetimes and that of the climate forcers they influence—all of which range widely. Their lifetime is determined by biological or chemical processes, or both, such as through photosynthesis, bacterial consumption, or reactions with sunlight or other gases. Some are long-lived climate forcers (LLCFs, e.g., CO2, N2O, some HCs), meaning that their contributions to today’s warming are largely from the accumulation of emissions over time. On the other hand, many forcers have average atmospheric lifetimes on the order of a week to a decade (short-lived climate forcers (SLCFs), e.g., CH4, CO, NMVOCs, BC, and all climate coolers; Table 1), and their contributions to today’s warming or cooling are predominantly from recent emissions. The rise in emissions since the Industrial Revolution has seeded the atmosphere with this mix, from century-old CO2 to recent emissions of CH4, all of which require consideration.

Understanding the overall net climate impacts of sectors currently and over time is critical to improving climate action decision-making, as it provides clarity as to the magnitude and types of emission reductions needed to accomplish our goals. For example, expectations regarding the magnitude of mitigation needed to achieve a given amount of temperature reductions may be underestimated if those emissions cuts also include reductions in cooling species.

While any particular climate action goal may be envisioned to target individual emissions (e.g., reducing CO2), they often impact multiple species from the sector being targeted5,6. For example, retiring coal-fired power plants may target CO2 reductions, but it also reduces emissions of the cooler SO2. However, the inverse is not necessarily true; air pollution controls targeted at SO2, for example, are effective at reducing human health burden and other environmental impacts but can accelerate climate warming if warming species emissions are not also reduced. Given that policy is often predicated for specific sectors, understanding emissions at the sectoral level is vital7.

While the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessed the impact of current sectoral emissions on temperature change in both the near- and long-term (Fig. 6.16 in ref. 2), the assessment of historical sectoral contributions only considers traditional greenhouse gases (i.e., not emissions that influence concentrations of greenhouse gases, such as CO and NMVOCs as indirect forcers, nor emissions of aerosols), and converts all non-CO2 forcers into their CO2 equivalence (CO2e) based on the long-term impact of a pulse of emissions (Fig. 2.16 in ref. 8). This yields a skewed perspective of the role of individual economic sectors in driving climate change because of the absence of coolers and indirect greenhouse gases from non-methane sources and collapses the relative strength of warming gasses into a single metric of duration9.

Here we build on the method employed by the latest IPCC assessment report to quantify how warming and cooling emissions since 1750 of 33 prominent species (23 of which are halogenated compounds; see Table 1 and Figs. S1–2) from agriculture (including energy-use from forestry and fisheries), buildings, fossil fuel production and distribution (i.e., emissions not from combustion but rather extracting and transporting fuels, such as natural gas leakage), industry, power generation, transportation, and waste contribute to current global surface air temperature change (in 2022, the year of latest relevant emissions data) relative to pre-industrial levels. These sectoral categories are selected given their distinct emissions sources and mitigation measures. We exclude biomass burning and land-use changes in our analysis, given data limitations, and the difficulties in partitioning into anthropogenic/natural emissions sources and sectoral attribution of activities. To highlight the temporal tradeoffs inherent in these sectoral emissions going forward, we also quantify how current emissions from these sectors will impact temperatures in 10, 20, and 100 years comparatively (also following methods from the latest IPCC report).

Results

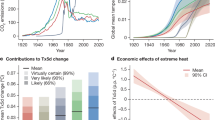

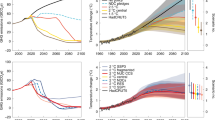

Contribution of historical emissions to today’s warming by emitted species

We estimate climate warmer emissions could have driven around 2.18 ± 0.14 °C warming since 1750 (Fig. 1, Tables S1–2). Around 1.25 °C/0.93 °C is from emissions of long-lived/short-lived warmers, respectively (Figs. 2, S3). For the LLCF warmers, CO2 accounts for 47% of current gross warming, with N2O and HCs each contributing 5%. For the SLCF warmers, CH4 contributes 29%, CO and NMVOCs combined contribute 11%, and BC contributes 3%. Despite gross warming already breaching the 2 °C international temperature target, emissions of short-lived climate coolers offset more than a third of this warming, approximately 0.83 ± 0.15 °C, mostly from SO2 (68%), with less from NOx (17%), OC (13%), and NH3 (2%). Overall, warming effects from anthropogenic emissions outweigh cooling effects by close to 3:1, leading to a 2022 net temperature rise of around 1.35 ± 0.21 °C since preindustrial times. These results are consistent with IPCC estimates2, as similar methods and databases are used.

Solid (hashed) bars represent warming (cooling) impact. Emissions and sectoral shares in parentheses are contributions to gross warming and cooling, respectively. CO2: Carbon Dioxide; N2O: Nitrous Oxide; HCs: Halogenated Compounds [LL-HCs: long-lived HCs] including Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs); CH4: Methane; O3: Tropospheric & Stratospheric Ozone; sH2O: Stratospheric Water Vapor; AER: Aerosol direct effects; Clouds: Aerosol-induced cloud effects; CO & NMVOCs: Carbon Monoxide & Non-Methane Volatile Organic Carbons; BC: Black Carbon; SO2: Sulfur Dioxide; NOx: Nitrogen Oxides; OC: Organic Carbon; NH3: Ammonia. Sector to emissions data taken from the analysis herein (including emissions contributions to net temperature change), emissions to forcings data taken from ref. 2. Biomass burning and land use changes not included. Agriculture includes energy-use emissions from forestry and fisheries. Power represents power generation.

Bars are ranked by net warming (black diamond). Darker (lighter) gray outlines highlight long-lived (short-lived) emitted species (note that not all HCs are long-lived). Climate warmer and cooler pies are proportional by radius. Further uncertainty details shown in Table S2. Biomass burning and land-use change emissions not included.

We note that 2023 and 2024 temperatures have increased further above this estimate. While attribution is still being studied, it appears partially due to decreases in emitted coolers for valuable air quality measures but without a concurrent decrease in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations10, which further emphasizes the importance of considering all climate-relevant emissions.

Contribution of historical emissions to today’s warming by sector

The majority of current day temperature changes relative to pre-industrial levels from historical emissions comes from agriculture (including energy-use related emissions from forestry, aquaculture, and fisheries, Figs. 1–2, S2); 23.0%, 0.31 °C, SD = 0.06), fossil fuel production and distribution (FFPD; 22%, 0.30 °C, SD = 0.06), and industry (16%, 0.22 °C, SD = 0.11).

However, industry and the power sector’s contribution to warming would be significantly higher without the co-emitted cooling emissions, whereas agriculture, for example, emits few cooling species (Fig. 2). While industry contributes most to current gross warming, accounting for +0.44 °C, primarily due to CO2 emissions from 1750 to present, half of this warming is offset by emissions of shorter-lived climate coolers, mostly SO2 (Fig. 1). The power sector has a more striking ratio, with more than 80% of its current gross warming impact offset by emissions of climate coolers. (Note that this is a global analysis, and regional emissions from, for example, the power sector may be different in their respective warmers and coolers.) The strong influence of cooling species from industry and power sectors contextualizes recent findings that decreases in industrial aerosol emissions can drive short-term warming by reducing cooling emissions11. Mostly a function of NOx and SO2, this cooling effect has been declining since ~2000 as significant air quality improvements have been achieved (Fig. S3).

Interestingly, the gross cooling from a given sector is inversely correlated with its CO2 emission-driven warming (p = 0.001, r2 = 0.91, F = 60.741,5), meaning as a sector’s warming fraction is increasingly dominated by CO2, it also emits more coolers (Fig. 3). This is largely from SO2 (Fig. S3). This is significant because CO2 is long-lived and coolers are short-lived, meaning that even as current warming from high-emitting CO2 sectors is largely offset by concurrent emissions of coolers, the CO2 emissions will continue to warm the climate for centuries, but the cooling effect is only temporary (unless emissions are sustained). Even if mitigation strategies reduced emissions of all species, past emissions of LLCFs would continue to affect the climate for decades, whereas previously emitted SLCFs would not. Further, if emissions of coolers are specifically targeted and abated, for example, through maritime shipping regulations intended to decrease air pollution, the result can be more rapid warming given that CO2 emissions are essentially unchanged10 (Fig. S3). The substantial improvement in air quality justifies the reductions in coolers regardless of climate impact, while the critical need to prevent further atmospheric build-up of LLCFs justifies immediate action to reduce emissions. This demonstrates that CO2, CH4, and other warming emission reduction ambitions need to be heightened to accommodate the accompanying loss of cooling species and “unmasking” of historically accumulated long-lived greenhouse gases.

These are aggregated global scale estimates; regionally, sectors may have different mixes of emissions. Dashed line is a linear regression through all points. For individual cooling species contributions, see Fig. S4. Error bars represent one standard deviation. Tick marks on graphs refer to points specifically.

On the other hand, sectors that are dominated by SLCF warmers are not major sources of SLCF coolers. These include agriculture (including livestock, manure management, and rice production), fossil fuel production and distribution, and waste. These sectors therefore represent a compelling target for near-term warming reductions and rapid actions (especially given cost-effective abatement potentials12) and can offset some of the unmasked warming from reducing SLCF coolers in other sectors. Note that for fossil fuel production and distribution, mitigation of SLCFs (most prominently CH4) does not alleviate emissions from downstream use of fuels (often in the form of CO2). Therefore, we also estimate the relative contribution of fossil fuel production and distribution emissions allocated to their end-use sectors (see Methods). With this reallocation, the power sector’s contribution to current warming more than triples from 4 to 14% (Tables S3–4).

Contribution of current sectoral emissions to future warming

The influence of today’s emissions on future warming further illustrates the interplay between warmers, coolers, and different lifetimes and warming intensities of various emission mixes. Emissions from sectors dominated by powerful short-lived warmers, critical for today’s experienced warming, become less influential on long-term temperatures as the effect of those warmers declines. For example, current emissions (2022) from agriculture will drive ~16% of experienced warming in 2032 (a decline from present due to the shorter lifespan of methane), and only 6% in 2122 (Fig. 4), mostly via accumulated and current long-lived N2O emissions13,14.

Conversely, less significant sectors in the near-term (because they also emit short-lived coolers) become much more important in the long-term. Current emissions from the power sector, for example, will drive ~12% of warming in 2032 due to primarily CO2-based emissions and concurrent emissions of cooling species. But as cooling species have a shorter lifespan, the power sector by 2122 will be responsible for 34% of warming (resulting from present-day emissions).

Allocating fossil fuels to their end-use sector further enhances this pattern, with current emissions from agriculture contributing to 25% of global temperature rise in 2032 but declining to 8% in 2122, whereas power increases from 25 to 37% over that timeframe (Fig. S5). This interplay means that different decarbonization pathways will have differential effects that change over time. Successful decarbonization in sectors that also emit substantial coolers may mean less temperature reduction in the short term but a substantial long-term benefit as those coolers disappear.

Discussion

Consistent sectoral emissions of powerful short-lived warmers and coolers are like rolling waves on top of the rising tide of long-term warming; both contribute to consistently increasing global temperatures, but reductions in one or the other have differential effects depending on the timeframe of reference.

Fundamentally, systemic strategies to achieve global climate ambitions require thinking across the spectra of emissions, considering co-emittance of warmers and coolers, and the various lifetimes and strengths of action15. Focused action targeting short-lived warming species can reduce the rate of warming (2–15% reduction) and net temperature increase (0.03–0.15 °C) in the next decades16, an important objective for limiting impacts and feedback processes driven by rapid temperature rise17. The concept of targeting SLCFs for a low-cost12, rapid acting near-term climate strategy (e.g.,18,) has been discussed, and recent modeling suggests a broad strategy that focuses on non-CO2 abatement in addition to a CO2 focus substantially increases the time before net-zero CO2 emissions needs to be achieved (21 years for the 1.5 °C goal, 30 years for the 2.0 °C goal19). Mitigation aimed at long timescales (e.g., 2100) targets reductions in long-lived warmers, which can result in tradeoffs with short-term warming (or less than anticipated cooling) as a result of the concurrent mitigation of shorter-lived but potent cooling species.

Overall, mitigating both LLCFs and SLCFs is necessary to achieve climate goals of long-term climate stabilization and limiting near-term rates of warming, and to address air quality concerns20,21. The fast turnover time of those SLCFs means rapid action on near-term warming is possible, but insufficient for future generations. Adding complexity, a reduction in co-emitted cooling species may offset near-term improvements from reductions in warmers but be necessary for long-term climate ambitions and other air quality goals (a likely contributor to the very recent spike in temperatures10).

Strategic planning for, and evaluation of, progress towards climate goals needs to take both warming/cooling effects and their differential lifespans into account – critical long-term gains may not be felt as strongly in the near term due to concurrent loss of coolers, and near-term gains may have less of a long-term impact. Innovations and warming emissions reductions in sectors with substantial cooling species will require increased ambitions to offset the unmasked warming as a result of cooling species reductions. This is a real challenge, but one that can be overcome with a complete consideration of emissions. Overall goals need to be ambitious and broad-based such that the overall arc of climate mitigation succeeds across all timescales.

Methods

Estimating global warming due to individual species and sectors

The majority of annual emission data are obtained from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS v_2021_04_21 and v_2024_04_0122,23). CEDS data was used in the IPCC Assessment Report 6 (AR6) CMIP6 global climate model experiments2,24. The CEDS emission inventory includes the following 10 species from 1750 to 2022: CO2, CH4, N2O, SO2, NOx, CO, VOC, BC, OC, and NH3 (Table 1). We partition the original CEDS emission sectors into the following seven sectors, comprised of distinct emissions sources that can have targeted mitigation measures: Power, Fossil Fuel Production and Distribution (FFPD), Agriculture, Industry, Buildings, Transportation, and Waste (Table 2). For example, 1A1a represents electricity and heat production, which was allocated to the power sector; 3D represents rice cultivation, which was allocated to the agricultural sector. In the CEDS version utilized here (v_2024_04_01), CH4 and N2O sectoral emissions are only available from 1970 to 2022. Thus, we use the previous version (v_2021_04_21) – with equivalent total annual emissions – to extend the CH4 and N2O time series back to 1750, where their 1970 sectoral fractions are applied retroactively to 1750-1969.

Note that the emission data compiled here from CEDS contain national estimates, but only globally aggregated (by sector) annual emissions were used in this study. Further, biomass burning and land-use change emissions are not included in our analysis (nor CEDS), given data limitations, difficulty partitioning between anthropogenic and natural sources, and potential allocations to multiple sectors. While biomass burning is a source of many of the emitted species considered in our study (such as CH4, N2O, CO, VOCs, BC, OC, NOx, NH3, and SO2), IPCC data suggests that the warming and cooling impacts from emitted species largely offset one another in both the near- and long-term2. As a result, this would not meaningfully impact the results either for the long-term contribution to current warming or in projected warming of current emissions.

The inclusion of Halogenated Compounds (HCs) (only a suite of the most impactful species) was obtained from the World Meteorological Organization 2022 Report for Ozone Assessment (1970–202025;), the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (1990-202126), and the United Nations Environment Programme Ozone Depleting Substance (ODS) consumption database (1986-202127;). The 23 selected HC species (Table 1) largely match those species whose concentrations were inputs in the IPCC AR6 Chapter 6 Figure 6.12 calculations, and include prominent chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). Therefore, we do not include other fluorinated gases such as sulfur hexafluoride, perfluorocarbons, and nitrogen trifluoride, which are sometimes included in climate assessments. We note that these gases, while still important, have relatively smaller roles in present-day warming than the HC species included in our analysis (e.g., ref. 28).

For CFC-11 and CFC-12, global emissions are allocated to the broader sectors by using the sectoral fractions from EDGAR and Alternative Fluorocarbons Environmental Acceptability Study data29. For the other HC species, emissions from ref. 25 were adopted, with sectoral allocations derived from the EDGAR-based fractions of corresponding species. Species that appear in the EDGAR data, but not in the WMO 2022 Report, are still retained with their respective sectoral allocations. A number (n = 13) of species in the WMO 2022 Report without available sectoral fractions are allocated based on our literature survey (e.g., refs. 30,31,32). The AFEAS database only covers industrial sales up to the year 2000; therefore, emissions of shared species in the WMO 2022 Report after the year 2000 were partitioned using the year 2000 fractions. CFC-11 and CFC-12 emissions due to non-hermetic refrigeration are allocated to the Buildings, Transportation, and Industry sectors based on the best available assumption of equal partitioning. Similarly, CFC-11 and CFC-12 emissions from open-cell foam are equally partitioned into the Industry and Building sectors.

To estimate the 2020–2022 HC emissions not included in the source databases, we extrapolate their emissions based on the linear trend of 2015–2019 so that all HC species are covered in the entire period (1970–2022) as in the other 10 species.

For each species, we also estimate the relative contribution with FFPD-related emissions re-allocated to their appropriate end-use sectors. To do so, we allocate the fractions of FFPD-related emissions (by fuel product type (i.e., coal, oil, and natural gas), to the following sectors: Power, Industry, Transportation, Buildings, Waste, and Agriculture, using the final consumption data for end-use sectors (in the energy units of PJ) from the International Energy Agency World Energy Balances33.

To best match the FFPD-related sectors in the CEDS to the IEA sectors, we combine the IEA fuels consumption data: “Oil Products”, “Natural Gas”, and “Crude, NGL, and Feedstocks” when calculating fractional contributions, while “Coal, Peat, and Oil Shale” products are kept independent of the others. Table 3 lists the IEA final consumption sectoral fractions used to re-allocate the CEDS FFPD-related emissions for each species into the other six major sectors.

Some consumption end-use sectors defined by the IEA do not match closely with the broad sectors utilized in this study. Specifically, the IEA does not have an individual “waste” sector but rather includes waste end-use in the sector of “commercial and public services.” Without the detailed knowledge underlying the IEA sectors, we allocate the “commercial and public services” final consumption to Waste. Similarly, the IEA has an “other final consumption” sector which is defined to include “agriculture/forestry, fishing, non-specific (other) and non-energy use”; we allocate this sector to Agriculture (which includes fisheries and forestry) while recognizing that there may be non-agriculture related consumption included. The IEA only provides final consumption data for 1971–2021, so we utilize the 1971 sectoral fractions for all years before 1971, and we linearly extrapolate the data to 2022 to cover the entire emissions time period.

Accumulated emissions impacts

Using the annual emissions for each species (Fig. S1), we calculate the emissions remaining in the atmosphere in any given year by accounting for the decay of previous emissions (termed herein ‘accumulated’ emissions; Fig. S2). For CH4, N2O, and individual HCs, the decay function is a simple exponential decay that considers their lifetimes, as shown by Equation: (1)

Where \({{AE}}_{x}\) is the accumulated emissions after decay of the climate forcer \(x\) at time \({t}\) (year), \({E}_{x}\) are emissions of the climate forcer \({x}\) at time \({t}\) (year), \({{tau}}_{x}\) is lifetime of \({x}\) and the summation formula represents the sum of emissions after decay from all prior years. The lifetime constants are obtained from IPCC AR6 (Table 1).

The decay function for CO2 is parametrized following34 such that:

Where the parameters \({a}_{n}\) and \({t}_{n}\) \(\left(n=\mathrm{1,2,3}\right)\) correspond to the fractions (unitless and adding up to 1) and time constants related to different CO2 sinks, respectively. The parameters used were a0 = 0.2366, a1 = 0.2673, a2 = 0.2712, a3 = 0.2249, t1 = 4.272, t2 = 33.10, t3 = 302.4.

If a species’ lifetime is less than 1 year (such as SO2, NOx, CO, VOCs, BC, OC, and NH3), we use only the latest annual emissions to represent the contribution to their atmospheric concentration without considering previous years’ emissions.

By calculating the time series (1750–2022) of accumulated emissions accounting for the decay of individual species, and subsequently allocating to individual sectors, we can then assess how each species/sector is contributing to warming or cooling in any given year. Note, however, that we do not include climate-chemistry feedbacks due to changes in natural sinks and sources.

Radiative forcing estimates

Given that the radiative forcing in any given year is generally proportional to excessive atmospheric abundance (relative to 1750), we use the accumulated emissions calculated in the previous section (1b) as a proxy for the atmospheric abundance increase.

The total emission-based effective radiative forcing (ERF) time series of 1750–2019 for each species is obtained directly from IPCC AR6 (Chapter 6 Figure 6.1224;) where the total emission-based ERF, as the sum of contributions via different component mechanisms (i.e., methane lifetime, aerosol-cloud interactions, stratospheric water vapor, etc.), is derived from AerChemMIP multi-model mean ERFs35. Our final ERF time series is not adjusted for potential non-linearities associated with aerosol-cloud interactions, which would otherwise entail a slight scale-down of the aerosol-cloud component-related ERF.

The IPCC provided ERF values of the halogenated compounds broadly classified as CFCs and HCFCs35. We note that minor CFCs and HCFCs included in the IPCC, which we do not consider in our study due to a lack of global sectoral inventories, are CFC-112a, CFC-113a, CFC-114a, HCFC-133a, HCFC-31, and HCFC-124. The IPCC also contains separate ERF values for 11 HFCs36. We note that we also include three HFCs that are not in the IPCC: HFC-134, HFC-143, and HFC-41. We do not account for the emissions of some other HC species (i.e., SF6, NF3, CCl4), that yield smaller contributions to the present-day radiative forcing as compared to CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs, and are not included in IPCC HC ERFs.

To extend the ERFs to the year 2022 to match the emissions time series, we use linear extrapolation of the final 5 years of the IPCC ERFs (2015–2019) to calculate the species ERFs for the period 2020–2022. We then use the sectoral breakdown (in %, rather than absolute values of accumulated emissions) to partition each species’ total emission-based ERF into individual sectors. Linear additivity is assumed here so that the aggregation of all species and all sectors amounts to the total ERF provided in IPCC AR62,24.

Estimating present-day temperature change due to individual species and sectors

In order to provide a first-order assessment of temperature changes over time as well as the relative contribution of each primary emission species and sector, we use an impulse response function (IRF) approach to convert the ERF time series into a global surface air temperature (GSAT) change time series (Eq. 3). IRF, as the core component of the metric Global Temperature-change Potential (\({GTP}\)), is formularized following Eq.(4) to mimic the behavior of other reduced complexity models. Note that the two major coefficients reflecting the shallow ocean and deep ocean thermal inertia are tuned to match the total warming (without sectoral breakdown) assessed by the IPCC also using an IRF approach (IPCC AR6 Chapter 6 Figure 6.12).

Where x is the unique climate forcer (species and sector), t is the end year in question, and t’ is the year between t and the baseline year (1750) when anthropogenic ERF are set to zero. The IRF is formulated as follows:

Where IRF constants \({q}_{1}\), \({q}_{2}\), \({d}_{1}\) and \({d}_{2}\) represent the thermal response parameters (Table 4). In an effort to match \(\triangle {T}\) in the final years estimated by the IPCC, the timescale parameters are tuned such that \({d}_{1}\) is 80% larger and \({d}_{2}\) is 50% larger than the original constants of the IPCC calculations, respectively, but maintaining a less-than-1\(\sigma\) departure from the median values37.

Estimating future temperature change due to present-day emissions of individual species and sectors

In quantifying the future impact of current emissions, we estimate the relative contribution from each sector and each species by using Global Temperature change Potential (GTP)-weighted CO2 equivalence estimates at 10, 20, and 100-year time horizons (Table S5). The GTP-based sectoral breakdown is presented in Fig. 4 for sectors including FFPD, and Fig. S5 for FFPD re-allocated to end-use sectors, showing the present-day (2022) emission’s future impacts at various time intervals, which is equivalent to the time integration of single-year emissions following the IRF approach. We note that the GTP values used for the future analysis (taken mostly from the IPCC reports; see Table S5) are consistent with our calibration for our historical analysis, given that we calibrated the two time constants in the GTP formula, which would affect the AGTP of all species, and thus GTPs (ratios of AGTPs) are not affected.

Uncertainty estimates via Monte Carlo process

Uncertainty in the GSAT changes is quantified using the IPCC species-level ERF standard deviations for the year of 2019 (Table 5) and the IRF parameters representing equilibrium climate sensitivity (q1 and q2, Table 4). To estimate uncertainty, we perform a Monte Carlo simulation (n = 1000) utilizing a normal distribution24,35 for individual species ERF and an inverse normal distribution (mean = 3 K, range of 2.5–4 for the ECS, reflected in the q parameters in IRF). Mean and standard deviation (SD) of the resulting GSAT distribution are used to quantify relative standard deviation (SD/Mean), which is then used to calculate the standard deviation of warming values derived for each species and each sector. Relative standard deviation values are invariant to sectors and years, as IPCC ERF uncertainty values are only available for 2019 and for the species total (Table 5).

Total temperature change has a standard deviation of 0.21 °C. As the various combinations of species (e.g., for all warmers or for all species under one sector) are not simulated in isolation, for their reported values (error bars in Fig. 1), the standard deviations of each species are added together in quadrature (square root of the sum of the variances).

Data availability

The compiled sectoral emission data is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10946133.

Code availability

The modeling code script is available at https://github.com/bwalkowiak/Anthropogenic-Climate-Forcers.

References

Fu, B. et al. Short-lived climate forcers have long-term climate impacts via the carbon–climate feedback. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 851–855 (2020).

Szopa, S. et al. Short-Lived Climate Forcers. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 817–922, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.008 (2021).

Sun, T., Ocko, I. B., Sturcken, E. & Hamburg, S. P. Path to net zero is critical to climate outcome. Sci. Rep. 11, 22173 (2021).

Schleussner, C. F. et al. Overconfidence in climate overshoot. Nature 634, 366–373 (2024).

Lamb, W. F. et al. A review of trends and drivers of greenhouse gas emissions by sector from 1990 to 2018. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 073005 (2021).

Lamb, W. F., Grubb, M., Diluiso, F. & Minx, J. C. Countries with sustained greenhouse gas emissions reductions: an analysis of trends and progress by sector. Clim. Policy 22, 1–17 (2022).

Vashold, L. & Crespo Cuaresma, J. A unified modelling framework for projecting sectoral greenhouse gas emissions. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 139 (2024).

Dhakal, S. et al. Emissions Trends and Drivers. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge University Press). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157926.004 (2022).

Cohen-Shields, N., Sun, T., Hamburg, S. P. & Ocko, I. B. Distortion of sectoral roles in climate change threatens climate goals. Front. Clim. 5, 1163557 (2023).

Goessling, H. F., Rackow, T. & Jung, T. Recent global temperature surge intensified by record-low planetary albedo. Science 387, 68–73 (2025).

Bauer, S. E. The turning point of the aerosol era. J. Adv. Modeling Earth Syst. 14, e2022MS003070 (2022).

Harmsen, J. H. M. et al. Long-term marginal abatement cost curves of non-CO2 greenhouse gases. Environ. Sci. Policy 99, 136–149 (2019).

Davidson, E. A. The contribution of manure and fertilizer nitrogen to atmospheric nitrous oxide since 1860. Nat. Geosci. 2, 659–662 (2009).

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Dreyfus, G. B., Xu, Y., Shindell, D. T., Zaelke, D. & Ramanathan, V. Mitigating climate disruption in time: a self-consistent approach for avoiding both near-term and long-term global warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2123536119 (2022).

Harmsen, M. et al. Taking some heat off the NDCs? The limited potential of additional short-lived climate forcers’ mitigation. Clim. Change 163, 1443–1461 (2020).

Ripple, W. J. et al. Many risky feedback loops amplify the need for climate action. One Earth 6, 86–91 (2023).

Bowerman, N. H. et al. The role of short-lived climate pollutants in meeting temperature goals. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 1021–1024 (2013).

Ou, Y. et al. Deep mitigation of CO2 and non-CO2 greenhouse gases toward 1.5 °C and 2 °C futures. Nat. Commun. 12, 6245 (2021).

Rogelj, J. et al. Disentangling the effects of CO2 and short-lived climate forcer mitigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16325–16330 (2014).

Shindell, D. et al. A climate policy pathway for near-and long-term benefits. Science 356, 493–494 (2017).

Hoesly, R. M. et al. Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geoscientific Model. Development 11, 369–408 (2018).

McDuffie, E. E. et al. A global anthropogenic emission inventory of atmospheric pollutants from sector- and fuel-specific sources (1970–2017): an application of the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS), Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3413–3442 (2020).

Blichner, S. M. IPCC AR6 WGI - Figures 6.12–6.22–6.24 (v1.0.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7006729 (2022).

World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Executive Summary. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022, GAW Report No. 278, 56 pp.; WMO: Geneva, (2022).

Crippa, M. et al. GHG emissions of all world countries, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2760/4002897 (2024).

UNEP, 2020, Country data: Data in tables — Consumption of controlled substances, United Nations Environment Programme Ozone Secretariat (https://ozone.unep.org/countries/data-table) accessed April 8, 2024.

Engel, A. et al. Update on Ozone-Depleting Substances (ODSs) and Other Gases of Interest to the Montreal Protocol, in: Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2018. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project – Report No. 58, 1.1–1.101, (2019).

AFEAS, 2001. Production, Sales and Atmospheric Release of Fluorocarbons through 2000. AFEAS, Arlington, VA (see www.afeas.org).

McCulloch, A., Midgley, P. M. & Ashford, P. Releases of refrigerant gases (CFC-12, HCFC-22 and HFC-134a) to the atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 37, 889–902 (2003).

Velders, G. J. M., Solomon, S. & Daniel, J. S. Growth of climate change commitments from HFC banks and emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 4563–4572 (2014).

Rigby, M. et al. Increase in CFC-11 emissions from eastern China based on atmospheric observations. Nature 569, 546–550 (2019).

IEA, World Energy Balances, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/world-energy-balances, Licence: Terms of Use for Non-CC Material.

Gasser, T. et al. Accounting for the climate–carbon feedback in emission metrics. Earth Syst. Dyn. 8, 235–253 (2017).

Thornhill, G. D. et al. Effective radiative forcing from emissions of reactive gases and aerosols – a multi-model comparison. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 853–874 (2021).

Hodnebrog, Ø. et al. Updated global warming potentials and radiative efficiencies of halocarbons and other weak atmospheric absorbers. Rev. Geophys. 58, e2019RG000691 (2020).

Leach, N. J. et al. FaIRv2.0.0: a generalized impulse response model for climate uncertainty and future scenario exploration. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 3007–3036. (2021).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to J.H.M. Harmsen for discussions regarding SLCF abatement costs, and Claire Henly, Erika Reinhardt, Gabrielle Dreyfus, and Ben Poulter for helpful feedback on the manuscript and figures. Partial support provided by a gift to EDF from Christina and Jeffrey Bird & Mary Anne Baker and G. Leonard Baker, Jr.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.B. and I.O. conceived of the study. B.W., Y.X., and I.O. led the climate model development. BW developed the coding. S.S., B.W., and S.D. conducted the temperature modeling. I.O. developed the figures. BB wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the final copy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buma, B., Ocko, I., Walkowiak, B. et al. Considering sectoral warming and cooling emissions and their lifetimes can improve climate change mitigation policies. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 287 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01131-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01131-8