Abstract

Forecasting super El Niño remains challenging, partly due to poor representation of westerly wind bursts (WWBs). We developed an artificial intelligence-based denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) to skillfully parameterize WWBs, capturing their joint modulation by oceanic and atmospheric processes. The DDPM-based scheme effectively captures observed WWBs’ characteristics (e.g., frequency, intensity, and spatial center). When implemented in the Community Earth System Model, it outperforms both the control (CTRL, without WWBs parameterization) and conventional warm pool eastern edge (WPEE)-dependent parameterization in predicting intensity and seasonal phase-locking for super El Niños (1982/83, 1997/98, 2015/16). This improvement stems from DDPM’s realistic WWBs representation, correcting CTRL and WPEE’s biases of overly weak and westward-shifted winds during El Niño growth. Consequently, DDPM produces more realistic eastern Pacific sea surface temperature anomaly warming patterns. These findings underscore WWB's accuracy as key to super El Niño prediction and demonstrate machine learning’s potential for WWB's parameterization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

El Niño is the strongest interannual climate signal on Earth1, driving significant global impacts on weather, ecosystems, and economies2,3. Among these, super (or extreme) El Niño events have attracted significant attention due to their broader spatial extent and stronger amplitude of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies, which lead to more severe meteorological and climatic disasters4,5. However, considerable uncertainty remains in forecasting the amplitude of super El Niño events6,7. The uncertainties in forecasting super El Niño events stem from multiple sources, including (but not limited to) complex inter-basin interactions among the Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, and Pacific Ocean8, the nonlinear response of the atmosphere to oceanic processes9, and high-frequency atmospheric stochastic forcing10. Notably, a key manifestation of this stochastic forcing is westerly wind bursts (WWBs). Extensive research from observational, modeling, and theoretical perspectives has consistently demonstrated that WWBs play a pivotal role in shaping super El Niño evolution by injecting wind energy into the western and central Pacific11,12,13. This process enhances eastward zonal current anomalies and generates eastward-propagating downwelling equatorial Kelvin waves, which deepen the thermocline and facilitate the eastward migration of the warm pool14,15,16. Collectively, these dynamical mechanisms contribute to surface warming in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, leading to the development of El Niño. For instance, Lian and Chen (2021) demonstrated that the strong and persistent WWBs observed in March 1997 were a necessary condition for the onset of the super 1997 El Niño event. Similarly, numerous studies have highlighted that the contrasting intensities of the 2014/15 and 2015/16 El Niño events were largely driven by the frequency and intensity of WWBs17,18,19. Thus, the ability to realistically simulate WWBs during super El Niño development is vital for predicting the spatiotemporal evolution of super El Niño20,21.

However, many numerical models exhibit significant biases in simulating WWBs22,23,24. This underscores the necessity for the widespread application of WWB's parameterization schemes to thoroughly investigate their impacts on the diversity and predictability of El Niño13,25,26,27. For example, studies indicated that the occurrence of WWBs is modulated by oceanic conditions, manifesting as a type of semi-stochastic (or multiplicative) noise of El Niño14,28,29. This motivated Gebbie et al.30 to develop a now widely used semi-stochastic parameterization scheme for WWBs where WWB occurrence is influenced by SST (see “Methods” section). Beyond this success, subsequent studies also highlighted the importance of atmospheric internal variability in influencing the formation of WWBs31,32,33. For instance, the convective phase of the Madden-Julian Oscillation34 (MJO) is frequently associated with an increased likelihood of WWBs33,35, and Lian et al.31 highlighted that nearly 70% of WWBs are closely linked to tropical cyclone (TC). Thus, it is essential to consider oceanic and atmospheric variabilities simultaneously to capture the complexity of WWBs comprehensively.

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has been widely used in atmospheric science and achieved remarkable advancements36,37,38. It offers innovative approaches for parameterizing WWBs. For example, building on the foundational work of Gebbie et al.30, You et al.39 developed a neural WWBs parameterization scheme leveraging AI techniques, incorporating oceanic and atmospheric variables as predictors. However, these parameterization schemes enforce fixed spatiotemporal structures on WWBs and are limited to deterministic representations of only a few physical parameters. Additionally, since WWBs are only one component of high-frequency zonal wind (HFZW) anomalies, the WWB models may not objectively reproduce the uncertainty of the spatial-temporal evolution of WWBs comprehensively without including the realistically full spectral components of HFZW anomalies.

Moreover, given the impact of WWBs on El Niño forecasts, as well as the unpredictable nature of WWBs on the seasonal forecasting timescale, it is more crucial to estimate their occurrence likelihood throughout the season than to predict their exact timing40. As an attempt, Ji et al.27 developed an El Niño ensemble forecasting framework based on WWBs ensemble forecasting, which improves the forecasting skills of El Niño since it better accounts for interactions across different timescales than the widely used initial condition-based framework. However, the WWB's parameterization scheme used by Ji et al.27 considers only the role of the ocean. Developing a probability parameterization scheme for WWBs that simultaneously accounts for both oceanic and atmospheric processes is essential for capturing their associated uncertainties in the super El Niño forecast. In this paper, we aim to develop a more skillful parameterization for WWBs based on the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM, see “Methods” section), a state-of-the-art generative framework in AI. The DDPM-based parameterization is then integrated online into the Community Earth System Model (CESM) to systematically investigate the influence of WWBs on the prediction of super El Niño events.

Results

Evaluation of the new DDPM-based WWBs parameterization

First, we evaluated the simulation performance of WWBs across four DDPM-based parameterization schemes with different conditional physical variable combinations (i.e., SST anomalies (SSTA), outgoing longwave radiation anomalies (OLRA), and sea level pressure anomalies (SLPA)) designed to capture the spatiotemporal characteristics and stochastic nature of WWBs (see “Methods” section). As shown in Fig. 1a, e, the [SSTA] generates almost no WWBs. This discrepancy may arise because SSTA evolves relatively slowly, making it challenging for AI models to establish a robust mapping between slow-varying SSTA and rapidly varying HFZW anomalies. This limitation is corroborated by the power spectrum of HFZW anomalies (Fig. S1), which reveals that the HFZW anomalies generated by [SSTA] are predominantly characterized by low-frequency variability. As a result, these models fail to accurately capture the high-frequency, episodic nature of WWBs. With the OLRA included in [SSTA, OLRA], both the WWB intensity (NCWI below, see “Methods” section) and numbers increase substantially (Fig. 1a, b). However, their longitudinal center (LonCen, see “Methods” section) is too concentrated in the western Pacific to capture the widespread character in the observation (Fig. 1c, f), which was argued to be important in inducing the El Niño diversity41. On this basis, including SLPA as another input parameter in [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] further refines the simulation details of the WWBs numbers and NCWI (Fig. 1a, b), supporting the finding of Lian et al.23 that WWBs are closely associated with TCs. Besides, the [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] significantly improves the simulation of WWBs occurrence probability in each month (Fig. 1d), which is crucial for WWBs and El Niño ensemble forecasting27.

Observed and simulated WWB a total numbers, b annual accumulated NCWI, and c probability distribution of the LonCen, d ROC curve, the closer the curve is to the upper left corner, the better the simulation performance of the accuracy of WWBs monthly occurrence for all months during 2011–2022 (for details, see “Methods” section), and e–h scatter plots of the LonCen and NCWI of each WWB, comparing the observed and simulated. Shading and error bars indicate a one standard deviation interval among the 20 members. Blue, yellow, orange, purple, and green represent observations, [SSTA], [SSTA, OLRA], [OLRA, SLPA], and [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA], respectively.

Moreover, given the extensive research emphasizing the regulatory effects of SSTA on WWBs28,42, we trained [OLRA, SLPA] using OLRA and SLPA as constraints to further investigate the respective roles of oceanic and atmospheric processes in WWBs. The results indicate that compared to the [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA], the [OLRA, SLPA] simulates fewer and weaker WWBs (Fig. 1a, b), with a slight bias in the simulated monthly occurrence probability of WWBs (Fig. 1d). Additionally, the LonCen of WWBs in the [OLRA, SLPA] are more concentrated in the western Pacific (Fig. 1c, g), showing an obvious bias compared to observations. These results suggest that in the AI model, SSTA may provide a conducive environment for WWBs occurrence and regulate their central location, while the frequency and intensity of WWBs are primarily dominated by atmospheric internal variability. In other words, the regulatory effect of SSTA on WWBs requires the cooperation of atmospheric internal variability to better characterize the various physical attributes of WWBs, which is consistent with the findings of Liang et al.43 in numerical models. We also compared the [OLRA, SLPA] and [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] regarding WWBs’ maximum amplitude, latitudinal center, zonal range, duration, monthly frequency, and numbers of each year between 2011 and 2022. The [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] demonstrated superior simulation capability in all these aspects (Figs. S2–S3).

Furthermore, we compared the performance of the [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] with the traditional warm pool eastern edge (WPEE, see “Methods” section)-dependent WWBs parameterization30 in capturing key characteristics of WWBs, including their LonCen, monthly occurrence accuracy, numbers, and NCWI. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] significantly outperforms the WPEE-based approach in representing the physical features of WWBs. This result underscores the importance of incorporating atmospheric variability into the parameterization of WWBs35,39 and the high efficiency of the diffusion-based AI scheme in doing this. By better capturing the state-dependent nature of WWBs and their interactions with large-scale air-sea processes, the [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] is believed to provide a more robust framework for understanding and predicting the role of WWBs in super El Niño events.

The [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] (green) and WPEE-dependent (magenta) parameterizations are compared in their representation of WWBs for a LonCen, b monthly occurrence accuracy, c numbers, and d NCWI. The shaded regions indicate one standard deviation across the 20 ensemble members. The blue lines in (a), (c), and (d) represent the observed.

Embedding DDPM-based WWBs parameterization into CESM and forecasting of super El Niño

The evaluation above demonstrates that the [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] achieves the best performance in simulating WWBs among the diffusion-based frameworks. Therefore, in the subsequent forecast experiments focusing on super El Niño events, we exclusively coupled the [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA] with the CESM, which is compared with the one that adopts the traditional WPEE-dependent WWBs parameterization. For convenience, the super El Niño forecast experiments incorporating the two parameterizations are termed as “DDPM” and “WPEE” in the following text, respectively (see “Methods” section).

Figure 3 presents the observed, control (CTRL, CESM without WWBs parameterization), WPEE, and DDPM forecast experiments for the Niño3.4 index over a 12-month lead time, initialized in February and May (i.e., before and end of the boreal spring season) of 1982, 1997, and 2015, respectively. As shown, the CTRL consistently underestimates the intensity of super El Niño events, aligning with findings from previous studies44,45. In the WPEE experiment, the inclusion of WWBs partially improves the predicted El Niño intensity, but the overall underestimation persists. In contrast, the DDPM experiment demonstrated significant improvements in predicting the intensity of super El Niño events. Notably, the spread of ensemble members (the green shade in Fig. 3) effectively encompassed observations, indicating the reliability of the DDPM approach. This improvement stems from the DDPM’s more accurate representation of WWBs (Fig. 2), which better captures their critical role in establishing the super El Niño events46,47. Additionally, while observations indicate that all three El Niño events peak in December (i.e., seasonal phase-locking), the CTRL and WPEE exhibit significant biases in capturing this character. When initialized in February, CTRL and WPEE experiments exhibit a distinctive double-peak evolution: an initial Niño3.4 peak at 6-month lead time (summer) followed by weakening and subsequent re-intensification to a second peak (winter) at lead 12 months, contrasting with the observed steady intensification toward a single December peak (Fig. 3a–c). Notably, we emphasize that in the 1997 case, all three experimental configurations reproduce the observed December peak in El Niño development (Fig. 3b). For May initializations (post-spring when air-sea coupling is better established), while the double-peak feature weakens, the predicted peaks still lag observations by approximately one month (Fig. 3d–f). These errors reflect common seasonal phase-locking prediction biases prevalent in many complex climate models48,49,50. Notably, the DDPM experiment efficiently overcomes all these shortcomings and accurately predicts the evolution of all these super El Niño events. This hints that improved representation of high-frequency atmospheric processes like WWBs in climate models may help to mitigate the seasonal phase-locking bias of El Niño. Moreover, forecast experiments for the 1994/1995 and 2009/2010 moderate El Niño events showed DDPM’s improvement was slightly smaller than for super El Niño, but still yielded the best overall forecast results (Fig. S4).

Observed (blue), CTRL (orange), WPEE (magenta), and DDPM (green) forecast experiments for the Niño3.4 index (unit: °C) over a 12-month lead time, initialized in February and May a, d 1982, b, e 1997, and c, f 2015. The shaded areas represent one standard deviation across the 10 ensemble forecasting members, while the WPEE and DDPM experiments display the ensemble mean across these 10 members. The x-axis indicates the forecast end month, where (0) denotes months in the El Niño development year and (1) represents months in the subsequent year. For instance, in (d), May (0) corresponds to May 1982 while Jan (1) indicates January 1983.

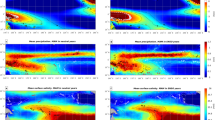

To better illustrate the spatiotemporal evolution, Fig. 4 presents the SSTA along the equatorial (5°S–5°N mean) Pacific from observations and the three forecast experiments (taking the 1997/98 event as an example, the results for the other two events are similar, as illustrated in Figs. S5–S8). The observed SSTA exhibits a broad spatial distribution spanning the central and eastern Pacific (Fig. 4a, e). In contrast, the major warming in the CTRL experiment is primarily confined to the far eastern Pacific, with only limited westward extension (Fig. 4b, f). Consequently, the SSTAs in the Niño3.4 region (black dashed boxes) are significantly underestimated compared to observations. Additionally, although manifesting weak warming within the Niño3.4 region, the CTRL exhibits a distinct seasonal double-peak structure (i.e., summer and winter), markedly diverging from observations (Fig. 4a, b, e, f). These findings align with the phase-locking biases identified in Fig. 3. The WPEE experiment produces a more westward-extended warming pattern compared to CTRL (Fig. 4c, g), exhibiting broader spatial coverage across the eastern Pacific. While this configuration partially mitigates the characteristic double-peak bias in the Niño3.4 index evolution (Fig. 3), its impact remains substantially limited—the simulated SSTA in the Niño3.4 region still exhibits pronounced underestimation compared to observations. Furthermore, the slower westward propagation of SSTA, combined with the unrealistic weakening of anomalies in the far eastern Pacific, causes a delayed peak in the Niño3.4 region relative to observations, leading to seasonal phase-locking biases in forecasts (Fig. 4f, g). In contrast, the DDPM experiment demonstrates notable improvements over CTRL and WPEE in terms of both the spatial distribution and intensity of SSTA (Fig. 4d, h).

a, e Observed, b, f CTRL, c, g WPEE, and d, h DDPM forecast experiments for the monthly mean SSTA (unit: °C) averaged between 5°S and 5°N over a 12-month lead time, initialized in February and May 1997. Contours indicate SSTA exceeding 2 °C. The black dashed boxes denote the zonal extent of the Niño3.4 region (190°W–240°W). The WPEE and DDPM experiments display the ensemble mean across these 10 members. Where 0 represents the year of El Niño development (1997) and 1 represents the following year (1998).

Mechanisms of DDPM in improving super El Niño prediction

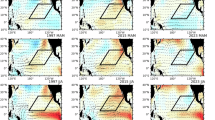

The results above demonstrate the significant advantages of the DDPM experiment in improving the prediction of super El Niño events. To understand the underlying physical mechanisms, Fig. 5 illustrates the spatiotemporal evolution of observed and predicted monthly mean westerly wind stress and sea surface height anomalies (SSHA). It is evident that, compared to observations, the westerly wind stress anomalies in the CTRL and WPEE experiments are weaker and more confined to the western Pacific. This results in a reduced propagation time for the upwelling Rossby waves (excited by westerly wind stress) to reflect at the western boundary as Kelvin waves, thereby more rapidly counteracting the eastward-propagating downwelling Kelvin waves51. Consequently, the SSHA and SSTA in the eastern Pacific are significantly weakened, as the positive feedback has less time to amplify them41. Although the westerly wind stress anomalies in CTRL and WPEE gradually strengthen and shift eastward with the development of SSTA, the anomalies show a systematic westward displacement compared to observations. This systematic bias fundamentally impairs the models’ capacity to sustain the Bjerknes feedback, leading to biases in the prediction of El Niño’s seasonal phase-locking and intensity. In contrast, the DDPM experiment, with its stronger and more eastward-shifted westerly wind stress anomalies that closely align with observations, facilitates the accumulation of downwelling Kelvin waves in the eastern Pacific, manifesting as an enhancement of positive SSHA in this region. This process intensifies positive SSHA in the region, thereby strengthening the Bjerknes feedback52 and accelerating the amplification of SSTA. Simultaneously, the continuous growth of SSTA further increases the probability of WWBs occurrence, creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies the SSTA. The improved representation of these dynamical interactions in the DDPM framework highlights its superior ability to capture the key mechanisms driving super El Niño events, leading to more accurate predictions of their seasonal phase-locking and intensity. These results demonstrate that improved representation of WWBs’ characteristics contributes to reducing model systematic biases, thereby improving the forecast skill for super El Niño events.

a, e Observed, b, f CTRL, c, g WPEE, and d, h DDPM forecast experiments for the monthly mean SSHA averaged between 5°S and 5°N over a 12-month lead time, initialized in February and May 1997. Black vector arrows in (a–h) represent monthly mean westerly wind stress anomalies (units: N/m2, shown only for values exceeding 0.02 N/m2).

Discussion

This study first developed a skillful parameterization scheme for WWBs using an AI-based diffusion model, which effectively reproduces multiple observed physical attributes of WWBs. Based on this scheme, we further revealed that WWBs, as a form of multiplicative noise on the interannual timescale, originate from oceanic states that provide the background conditions for WWBs formation and regulate their central location. Meanwhile, internal atmospheric processes (e.g., MJO, TC) influence the intensity and frequency of WWBs. Therefore, WWBs cannot be solely attributed to SSTA regulation in the AI model as in previous parameterization schemes26,30. This is because SSTA regulation of WWBs requires coordination with internal atmospheric variability.

We then incorporate DDPM-based parameterization, along with a conventional WWBs parameterization dependent on the WPEE, into the CESM to conduct ensemble forecasting experiments for three historical super El Niño events. The results indicate that the DDPM scheme significantly improves the prediction of El Niño intensity and mitigates the seasonal phase-locking bias in comparison to the CTRL and WPEE experiments. This improvement primarily stems from the ability of the DDPM scheme to better characterize WWB occurrences, thereby mitigating the systematic biases in the CTRL and WPEE experiments, which tend to produce weaker and more westward-displaced westerly wind stress anomalies. As a result, SSTAs in the eastern Pacific are better maintained and progressively develop westward, exhibiting spatiotemporal evolution and intensity that closely align with observations.

Our results highlight the critical role of accurately representing WWBs in improving super El Niño predictions, while demonstrating the efficacy of AI-based approaches in addressing this longstanding challenge. Furthermore, as emphasized in the introduction, the predictability limit of WWBs on interannual timescales implies that any deterministic forecast of WWBs inherently carries considerable uncertainty, which inevitably propagates into super El Niño predictions. Our findings suggest that ensemble forecasting may serve as an effective strategy for addressing the interactions between phenomena across different timescales, such as WWBs and El Niño, thereby improving the reliability of climate predictions.

Methods

Data

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST53) and daily OLR spanning 1981–2022 were used54. Daily 10-m zonal wind and SLP data were obtained from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction–National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCEP-NCAR) Reanalysis 2 Project55, spanning 1979–2022. Additionally, daily SST, OLR, SLP, and 10-m zonal wind data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis v5 (ERA556) were also used, covering the same period (1979–2022). Daily anomalies within our analysis were defined as deviations from the 30-year climatological mean (1981–2010). Then, a 60-day high-pass filter was applied to the 10-m zonal wind anomalies to further isolate the high-frequency components. The observational data for monthly SST, SSH, and wind stresses were sourced from the Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS57).

Mathematical formulation of DDPM

DDPMs are a class of generative models designed to model the gradual transformation of data from a simple, known distribution, such as Gaussian noise, into more complex distributions, like those found in real-world atmospheric states58. DDPM has been successfully applied in various domains, including image synthesis59, and natural language processing60. More recently, their application in atmospheric science has gained attention, particularly in ensemble forecasting, due to their probabilistic framework for forecasting61,62.

The fundamental concept underlying DDPM is to simulate a forward diffusion process in which data is incrementally corrupted by noise, which is then followed by a reverse denoising process where the model iteratively learns to remove the noise to eventually reconstruct the original data. This reverse denoising process can subsequently be employed to generate new data, beginning with pure noise and denoising it through iterative refinement.

-

1.

Forward Diffusion Process

The forward diffusion process gradually adds noise to the data over a series of discrete time steps, effectively converting the data distribution \({x}_{0}\) into a simple Gaussian distribution \({x}_{T}(T\to +\infty )\). This process is often modeled as a Markov chain, where the data at each time step \(t\) is conditioned only on the data at the previous time step \(t-1\):

$$q({x}_{t}|{x}_{t-1})={\mathcal{N}}\left({x}_{t};\sqrt{1-{\beta }_{t}}{x}_{t-1},{\beta }_{t}{\boldsymbol{I}}\right)$$(1)where \({x}_{t}\) represents the data at time step \(t\); \({\beta }_{t}\) is a small positive scalar (linear interpolation from 0.0001 to 0.02) that controls the variance of the noise added at each step. \({\mathcal{N}}{\mathscr{(}}\cdot ;\mu ,\sum )\) denotes a Gaussian distribution with mean \(\mu\) and covariance \(\sum\); \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) is the identity matrix.

The cumulative effect of this forward process over \(T\) steps can be described by:

$$q({x}_{t}|{x}_{0})={\mathcal{N}}{\mathscr{(}}{x}_{t};{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha }}}_{t}{x}_{0},{(1-\bar{\alpha }}_{t}){\boldsymbol{I}})$$(2)where \({\alpha }_{t}=1-{\beta }_{t}\) and \({\bar{\alpha }}_{t}={\prod }_{s=1}^{t}{\alpha }_{s}\)

This formulation indicates that \({x}_{t}\) is a noisy version of the original data \({x}_{0}\), with noise increasing as \(t\) approaches \(T\):

$${x}_{t}={\sqrt{\bar{\alpha }}}_{t}{x}_{0}+\sqrt{{1-\bar{\alpha }}_{t}}{\xi }_{t}$$(3)Where \({\xi }_{t} \sim {\mathcal{N}}{\mathscr{(}}0,{\bf{I}})\).

-

2.

Reverse Diffusion Process

The reverse diffusion process aims to recover the original data from the noisy data \({x}_{t}\) by learning a model that approximates the reverse Markov chain. When \({\beta }_{t}\) is small enough, the inverse process is also a Gaussian distribution:

$${p}_{\theta }({x}_{t-1}|{x}_{t})={\mathcal{N}}\left({x}_{t-1};{\mu }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t\right),\sum _{\theta }({x}_{t},t)\right)$$(4)where \({\mu }_{\theta }({x}_{t},t),{\sum }_{\theta }({x}_{t},t)\) are functions (often parameterized by neural networks) that predict the mean and variance of \({x}_{t-1}\) given \({x}_{t}\) and the time step \(t\). \(\theta\) represents the parameters of the model. The goal of training is to learn the parameters \(\theta\) such that the reverse process accurately inverts the forward process, ultimately leading to the reconstruction of the original data \({x}_{0}\).

-

3.

Training Objective

It is not practical to directly calculate the distribution of the inverse operation of adding noise for all data \({p}_{\theta }({x}_{t-1}|{x}_{t})\). However, if a training set is used as input \({x}_{0}\), it allows us to approximate \({p}_{\theta }({x}_{t-1}|{x}_{t})\) effectively:

where \(q({x}_{t-1}|{x}_{t},{x}_{0})\) shows the inverse operation of adding noise and its mean and variance need to be determined. \(q({x}_{t}|{x}_{t-1},{x}_{0})={\mathcal{N}}\left({x}_{t};\sqrt{1-{\beta }_{t}}{x}_{t-1},{\beta }_{t}{\boldsymbol{I}}\right)\) denotes the distribution of the added noise. Since \({x}_{0}\) is known, we have:

Substituting Eqs. (6) and (7) into Eq. (5), we can get:

where \({\widetilde{\mu }}_{t}\) and \({\widetilde{\beta }}_{t}\) represent the mean and variance of \(q({x}_{t-1}|{x}_{t},{x}_{0})\), respectively.

Here, \({\alpha }_{t}\), \({\beta }_{t}\), \({\bar{\alpha }}_{t}\), and \({\bar{\alpha }}_{t-1}\) are all known parameters, while only \({\xi }_{t}\) is unknown. Thus, in training the reverse process of the neural network, the core objective is to predict the noise added in the forward process at each step.

So, this objective can be expressed as:

where \({\xi }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t\right)\) is the neural network’s estimate of the added noise \({\xi }_{t}\), and \(t\) is a random time step chosen during training. \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{q({x}_{0})}\) is the mathematical expectation of \(q({x}_{0})\).

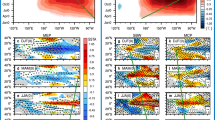

DDPM-based parameterization of WWBs

We adopted the DDPM to construct a new WWBs parameterization with high spatiotemporal complexity. Its framework is illustrated in Fig. 6. The forward chain indicated by black arrows in Fig. 6a is typically designed to map a complex data distribution into a standard Gaussian distribution by gradually adding noise, which is also the distribution shift learning process from practical data to Gaussian. The reverse chain, as red arrows in Fig. 6a, gradually turns Gaussian distributions into practical data distributions, which is regarded as the generation process. During the implementation, the reverse chain reconstructs the data by predicting the noise added during the forward chain and progressively denoising it step by step, as illustrated in the two boxes in Fig. 6a. Figure 6b displays the network structure we used in DDPM with detailed data flow and tensor operators, which contains two kinds of inputs for noised data and conditions, outputting the noise present in the data. Conditions represent a constraint, ensuring that the generated data maintains physical consistency. This network is designed with state-of-the-art neural blocks, including ConvNeXt block63 and Swin-Transformer block64, as well as our designed Down-/Up-Sampling block; the detailed architectures of internal modules are exhibited in Fig. 7.

a The black (red) arrows indicate the forward (reverse) diffusion process, and t indicates the time step of adding noise, with a total of T = 1600 steps. \(q({x}_{t}|{x}_{t-1})={\mathcal{N}}\left({x}_{t};\sqrt{1-{\beta }_{t}}{x}_{t-1},{\beta }_{t}{\boldsymbol{I}}\right)\) indicates that the noise added at each step follows a Gaussian distribution. \({\beta }_{t}\) is a small positive scalar (linear interpolation from 0.0001 to 0.02) that controls the variance of the noise added at each step. \({p}_{\theta }({x}_{t-1}|{x}_{t})={\mathcal{N}}\left({x}_{t-1};{\mu }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t\right),{\sum }_{\theta }({x}_{t},t)\right)\) represents the Gaussian distribution of the denoising process, with mean \({\mu }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t\right)\) and variance \({\sum }_{\theta }({x}_{t},t)\), where \(\theta\) is the distribution parameter. \({\xi }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t\right)\) is the neural network’s estimate of the added noise \({\xi }_{t}\). \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{q\left({x}_{0}\right),{\xi }_{t}{\mathscr{ \sim }}{\mathscr{N}}\left(0,{\bf{I}}\right)}\) is the mathematical expectation of \(q\left({x}_{0}\right)\), and \({\mathcal{L}}={{\mathbb{E}}}_{q\left({x}_{0}\right),{\xi }_{t}{\mathscr{ \sim }}{\mathscr{N}}\left(0,{\bf{I}}\right)}\left[{||}{\xi }_{t}-{\xi }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t\right)|{|}^{2}\right]\) represents the loss function, b is the network structure we used in DDPM with detailed data flow and tensor operators. Given the initial random noise and conditions (SSTA, OLRA, and SLPA), the neural network is trained to predict the added noise and gradually remove it.

a, b, and c, respectively, exhibit the detailed modules of Down-/Up-Sampling block, ConvNeXt block, and Swin-Transformer block used in DDPM-based WWBs parameterization, where \(k,s,p\) and \(c=64\) represent the kernel size, stride, padding, and channel. Pachify represents an operation that cuts the gridded data into small patches. Inverse Pachify is the restoration process. \({MLP}\) represents a multi-layer perceptron. \({Window}-{MSA}\) represents the multi-head sliding-window self-attention layer.

As highlighted in the introduction, El Niño, MJO, and TC events play significant roles in modulating the occurrence of WWBs. We selected various combinations of SSTA, OLRA, and SLPA as conditions for the DDPM, as they effectively capture the activity states of El Niño, MJO, and TC, analogous to You et al.39. We trained four distinct model configurations utilizing varying conditions: (1) SSTA, (2) SSTA and OLRA, (3) SSTA, OLRA, and SLPA, and (4) OLRA and SLPA, denoted as [SSTA], [SSTA, OLRA], [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA], [OLRA, SLPA], respectively. For example, SSTA serves as a constraint for the [SSTA], guiding the initial random noise to transform into daily HFZW anomalies at the corresponding time via the reverse process. The output variable for all model configurations was the daily HFZW anomalies. The spatial domain of the predictors and output was the tropical Pacific region (120°E–80°W, 30°S–30°N), with a spatial resolution of 2.5° × 2.5°. The remaining model configurations adopt a comparable methodology. We use NCEP and ERA5 data from 1979 to 2010 for training, and ERA5 data from 2011 to 2022 as test sets. For these four models, we generate 20 ensemble members to assess their simulation performance in simulating WWBs.

Traditional WPEE-dependent WWBs parameterization scheme

The traditional WWBs parameterization scheme, initially developed by Gebbie et al.30, captures the multiplicative noise characteristics of WWBs by linking their occurrence probability (\({p}_{{wwb}}\)) to the position of the WPEE. This approach has been widely adopted in studies investigating the dynamical impacts of WWBs on El Niño27,65,66,67,68. In this parameterization scheme, \({p}_{{wwb}}\) and the spatiotemporal distribution of their associated wind stress anomalies (\({\tau }_{{wwb}}\left(x,y,t\right)\)) are defined as follows:

where \({{wp}}_{{edge}}\) is the WPEE, defined as the longitude of the 28.5 °C isotherm; \(t\) is the considered time. A WWB event was initiated only when \({p}_{{wwb}}\) was greater than a random number. The meanings and specific values of the parameters in Eqs. (12) and (13) are summarized in Table 1 below, consistent with those used in Chen et al.66. While the parameters in Eq. (13) are presently treated as deterministic, future work could explore integrating stochastic processes to better capture WWB variability. Such refinements might improve the parameterization’s skill and its utility for El Niño forecasting, though this extension lies beyond the scope of the present study.

Definitions of WWBs and Niño index

The definition of a WWB event follows Ji et al.27, where the threshold for WWB detection is defined as three times the mean standard deviation of HFZW anomalies over the 5°S–5°N, 120°E–80°W region, consistent with Seiki et al.24. The WWBs thresholds for observations and the four model configurations, i.e., [SSTA], [SSTA, OLRA], [SSTA, OLRA, SLPA], and [OLRA, SLPA], are 5 m/s, 4.6 m/s, 4.2 m/s, 4.9 m/s, and 4.8 m/s, respectively. Additionally, previous studies have demonstrated that the cumulative WWBs intensity (CWI) and WWBs’ longitudinal center (LonCen) are the key physical attributes affecting El Niño dynamics. For example, Chen et al.69 noted that the strong CWI was a crucial factor in the occurrence of the super El Niño in 2015. Moreover, the central position of WWBs significantly affects the annual cycle and diversity of El Niño41,70. Therefore, we primarily evaluate the DDPM’s ability to characterize these two features. The CWI, LonCen, of WWBs are defined as follows35,69:

where the integral covers the whole spatiotemporal domain of a WWB event. The term \({lon}\left(x\right),{lat}\left(y\right)\) represent the spatial position of the longitude and latitude of \({u}_{10}\), with \(x\), \(y\), and \(t\) representing longitude, latitude, and WWB durations, respectively. We normalized the CWI by dividing it by the standard deviation, hereafter termed NCWI. Besides, the maximum WWB amplitude is defined as the maximum value within the WWB spatiotemporal region, and the zonal range is defined as the range between the farthest and nearest points within this region. The duration is defined as the interval between the first and last day that meets the WWB definition. The latitude center (LatCen) of WWBs is defined as Eq. (14). The Niño3.4 index is defined as the area-averaged SSTA over the region 5°N–5°S, 120°–170°W.

Relative Operating Characteristic curve

The Relative Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is commonly utilized to evaluate the performance of probabilistic forecast models. When assessing the occurrence of an event, the model’s predictions are verified against actual outcomes, resulting in one of the following categories71: true positive (TP), false negative (FN), false positive (FP), or true negative (TN). Based on these results, a binary contingency table (Table 2) can be obtained:

The hit rate (HR) and false-alarm rate (FR) are defined as:

Here, the ROC curve is used to evaluate the simulation accuracy of monthly occurrences of WWBs. In the observational data (2011–2022), each month was assigned a binary WWBs occurrence probability (1 if WWBs occurred, 0 otherwise). For each WWB parameterization, the predicted probability was defined as the proportion of ensemble members that predict WWB occurrence in a given month. Given a specific probability threshold (e.g., 0.5)—if the forecasted probability exceeds this threshold, a WWB event is predicted to occur; otherwise, it is predicted not to occur. Using varying probability thresholds, we calculated corresponding HR and FR pairs. The ROC curve was then generated by plotting HR against FR across all thresholds. The closer the ROC curve approaches the top-left corner of the coordinate plane, the higher the predictive accuracy of the simulation.

CESM

CESM version 1.2.2 is employed in this study for our forecast experiments. CESM is one of the most widely used fully coupled climate models, encompassing comprehensive components for the atmosphere, ocean, land, land ice, and sea ice72. Its ability to realistically simulate key features of El Niño variability and complexity has made it a cornerstone in El Niño-related research46,73,74. In this study, the atmospheric component was represented by the Community Atmosphere Model 4, configured with a horizontal resolution of approximately 0.9° × 1.25° (f09) and a 26-layer hybrid sigma-pressure vertical coordinate system. The oceanic processes were simulated using the Parallel Ocean Program 2 model, which features a horizontal resolution of roughly 1.1°× (0.54°–1°) (gx1v6) and 60 vertical layers. Additionally, the modeling framework incorporated several other critical components: the Community Land Model, the Los Alamos National Laboratory Sea Ice Model, the Community Ice Sheet Model, and the River Transport Model.

Design of super El Niño forecast experiments

Using the analysis fields derived from Song et al.74, we conducted three forecast experiments (Table 3) for three historical super El Niño events (1982/83, 1997/98, and 2015/16). The experiments were initialized in February and May of the El Niño development year, with each forecast lead time of 12 months.

We conducted a control forecast (CTRL) using the default configuration of the CESM as a baseline. Moreover, as highlighted in the introduction, the inherent predictability limit of WWBs on interannual timescales implies that deterministic forecasts of WWBs are subject to significant uncertainties, which inevitably affect predictions of super El Niño events. To address this, utilizing the stochastic nature of WWB's parameterization, we generated a 10-member ensemble forecast for both the DDPM and WPEE forecast experiments. This ensemble approach highlights the effectiveness of capturing multi-timescale interactions, such as those between WWBs and El Niño27, while emphasizing the importance of accurately representing WWB physical characteristics to enhance super El Niño forecast skills. Notably, given that the CESM inherently captures high-frequency atmospheric variability, we employed the online low-pass filtering method developed by Lian and Chen (2021) to remove high-frequency zonal wind stress components from the model before incorporating WWBs. This approach ensures numerical integration stability and mitigates potential impacts on model climate drift67.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available online. OISST and OLR are accessed at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.oisst.v2.highres.html53 and https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.olrcdr.interp.html54, respectively. NCEP data are freely available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis2.html55. ERA5 data are freely available at https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/browse-reanalysis-datasets56. The GODAS data are obtained from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.godas.html. Information and the source code for data analysis are available from the Matrix Laboratory (MATLAB 2023). *Version R2023a* [Software]. Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc. (https://www.mathworks.com).

Code availability

The CESM source codes are publicly available at https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/releases. The source code of the DDPM is available at https://zenodo.org/records/15655250.

References

Neelin, J. D. et al. ENSO theory. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103, 14261–14290 (1998).

Alexander, M. A. et al. The atmospheric bridge: the influence of ENSO teleconnections on air–sea interaction over the global oceans. J. Clim. 15, 2205–2231 (2002).

McPhaden, M. J., Zebiak, S. E. & Glantz, M. H. ENSO as an Integrating Concept in Earth. Sci. Sci. 314, 1740–1745 (2006).

Glantz, M. H. Currents of Change: Impacts of El Niño and La Niña on Climate and Society (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

L’Heureux, M. L. et al. Observing and predicting the 2015/16 El Niño. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 1363–1382 (2017).

Fang, X. & Chen, N. Quantifying the predictability of ENSO complexity using a statistically accurate multiscale stochastic model and information theory. J. Clim. 36, 2681–2702 (2023).

Mu, M. & Ren, H.-L. Enlightenments from researches and predictions of 2014–2016 super El Niño event. Sci. China Earth Sci. 60, 1569–1571 (2017).

Fan, H., Wang, C., Yang, S. & Zhang, G. Coupling is key for the tropical Indian and atlantic oceans to boost super El Niño. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp2281 (2024).

Srinivas, G. et al. Dominant contribution of atmospheric nonlinearities to ENSO asymmetry and extreme El Niño events. Sci. Rep. 14, 8122 (2024).

Shi, L., Alves, O., Hendon, H. H., Wang, G. & Anderson, D. The role of stochastic forcing in ensemble forecasts of the 1997/98 El Niño. J. Clim. 22, 2526–2540 (2009).

Hu, S. & Fedorov, A. V. The extreme El Niño of 2015–2016: the role of westerly and easterly wind bursts, and preconditioning by the failed 2014 event. Clim. Dyn. 52, 7339–7357 (2019).

Fedorov, A. V., Hu, S., Lengaigne, M. & Guilyardi, E. The impact of westerly wind bursts and ocean initial state on the development, and diversity of El Niño events. Clim. Dyn. 44, 1381–1401 (2015).

Chen, N., Fang, X. & Yu, J.-Y. A multiscale model for El Niño complexity. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 1–13 (2022).

Fedorov, A. V. The response of the coupled tropical ocean–atmosphere to westerly wind bursts. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 128, 1–23 (2002).

Lopez, H. & Kirtman, B. P. WWBs, ENSO predictability, the spring barrier and extreme events. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 114–10,138 (2014).

Yu, S. & Fedorov, A. V. The role of westerly wind bursts during different seasons versus ocean heat recharge in the development of extreme El Niño in climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088381 (2020).

Levine, A., Jin, F. F. & McPhaden, M. J. Extreme noise–extreme El Niño: how state-dependent noise forcing creates El Niño–La Niña asymmetry. J. Clim. 29, 5483–5499 (2016).

Chiodi, A. M. & Harrison, D. E. Observed El Niño SSTA development and the effects of easterly and westerly wind events in 2014/15. J. Clim. 30, 1505–1519 (2017).

Puy, M. et al. Influence of westerly wind events stochasticity on El Niño amplitude: the case of 2014 vs. 2015. Clim. Dyn. 52, 7435–7454 (2019).

Hu, R. et al. Predicting the 2023/24 El Niño from a multi-scale and global perspective. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–8 (2024).

Lian, T., Wang, J., Chen, D., Liu, T. & Wang, D. A strong 2023/24 El Niño is staged by tropical Pacific Ocean heat content buildup. Ocean-Land-Atmos. Res. 2, 0011 (2023).

Dellaripa, E. M. R., DeMott, C., Cui, J. & Maloney, E. D. Evaluation of equatorial westerly wind events in the Pacific Ocean in CMIP6 models. J. Clim. 37, 5953–5971 (2024).

Lian, T. et al. Westerly wind bursts simulated in CAM4 and CCSM4. Clim. Dyn. 50, 1353–1371 (2018).

Seiki, A. Westerly wind bursts and their relationship with ENSO in CMIP3 models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D03303 (2011).

Chen, N. & Fang, X. A simple multiscale intermediate coupled stochastic model for El Niño diversity and complexity. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 15, e2022MS003469 (2023).

Hayashi, M. & Watanabe, M. ENSO complexity induced by state dependence of westerly wind events. J. Clim. 30, 3401–3420 (2017).

Ji, C., Mu, M., Fang, X. & Tao, L. Improving the forecasting of El Niño amplitude based on an ensemble forecast strategy for westerly wind bursts. J. Clim. 36, 8675–8694 (2023).

Eisenman, I., Yu, L. & Tziperman, E. Westerly wind bursts: ENSO’s tail rather than the dog?. J. Clim. 18, 5224–5238 (2005).

Seiki, A. & Takayabu, Y. N. Westerly wind bursts and their relationship with intraseasonal variations and ENSO. Part I: statistics. Mon. Weather Rev. 135, 3325–3345 (2007).

Gebbie, G., Eisenman, I., Wittenberg, A. & Tziperman, E. Modulation of westerly wind bursts by sea surface temperature: a semistochastic feedback for ENSO. J. Atmos. Sci. 64, 3281–3295 (2007).

Lian, T. et al. Linkage between westerly wind bursts and tropical cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 431–11,438 (2018).

Liang, Y. & Fedorov, A. V. Linking the Madden–Julian oscillation, tropical cyclones and westerly wind bursts as part of El Niño development. Clim. Dyn. 57, 1039–1060 (2021).

Puy, M., Vialard, J., Lengaigne, M. & Guilyardi, E. Modulation of equatorial Pacific westerly/easterly wind events by the Madden–Julian oscillation and convectively-coupled Rossby waves. Clim. Dyn. 46, 2155–2178 (2016).

Madden, R. A. & Julian, P. R. Description of global-scale circulation cells in the tropics with a 40–50 day period. J. Atmos. Sci. 29, 1109–1123 (1972).

Feng, J. & Lian, T. Assessing the relationship between MJO and equatorial Pacific WWBs in observations and CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 31, 6393–6410 (2018).

Mu, M., Qin, B. & Dai, G. A commentary of “Artificial intelligence models bring new breakthroughs in global accurate weather forecasting”: top 10 scientific advances of 2023, China. Fundam. Res. 4, 690–692 (2024).

Mu, M., Qin, B. & Dai, G. The predictability study of weather and climate events related to artificial intelligence models. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 1005–1025 (2024).

Qin, B. et al. The first kind of predictability problem of El Niño predictions in a multivariate coupled data-driven model. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 5452–5471 (2024).

You, L., Tan, X. & Tang, Y. Construction of deep-learning based WWBs parameterization for ENSO prediction. Atmos. Res. 289, 106770 (2023).

L’Heureux, M. L. et al. ENSO prediction. In El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate 227–246 (American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2020).

Fang, X., Dijkstra, H., Wieners, C. & Guardamagna, F. An overlooked aspect concerning the effect of the spatial pattern of zonal wind stress anomalies on El Niño evolution and diversity. Clim. Dyn. 62, 7037–7047 (2024).

Gebbie, G. & Tziperman, E. Predictability of SST-modulated westerly wind bursts. J. Clim. 22, 3894–3909 (2009).

Liang, Y., Fedorov, A. V. & Haertel, P. Intensification of westerly wind bursts caused by the coupling of the Madden-Julian oscillation to SST During El Niño Onset and Development. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL089395 (2021).

Landsea, C. W. & Knaff, J. A. How much skill was there in forecasting the very strong 1997–98 El Niño?. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 81, 2107–2120 (2000).

Ineson, S. et al. Predicting El Niño in 2014 and 2015. Sci. Rep. 8, 10733 (2018).

Lian, T. & Chen, D. The essential role of early-spring westerly wind burst in generating the centennial extreme 1997/98 El Niño. J. Clim. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0010.1 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Suppressive MJO in April 2014 downgraded the 2014/15 El Niño. J. Clim. 37, 3377–3391 (2024).

Chen, H.-C. & Jin, F.-F. Simulations of ENSO phase-locking in CMIP5 and CMIP6. J. Clim. 34, 5135–5149 (2021).

Chen, H.-C. & Jin, F.-F. Fundamental behavior of ENSO phase locking. J. Clim. 33, 1953–1968 (2020).

Liao, H., Wang, C. & Song, Z. ENSO phase-locking biases from the CMIP5 to CMIP6 models and a possible explanation. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 189–190, 104943 (2021).

Rydbeck, A. V., Jensen, T. G. & Flatau, M. Characterization of intraseasonal Kelvin waves in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 2028–2053 (2019).

Bjerknes, J. Atmospheric teleconnections from the equatorial Pacific. Mon. Weather Rev. 97, 163–172 (1969).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the daily optimum interpolation sea surface temperature (DOISST) version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Liebmann, B. & Smith, C. A. Description of a complete (interpolated) outgoing longwave radiation dataset. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 1275–1277 (1996).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 437–472 (1996).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Behringer, D. W., Ji, M. & Leetmaa, A. An improved coupled model for ENSO prediction and implications for ocean initialization. Part I: The ocean data assimilation system. Mon. Weather Rev. 126, 1013–1021 (1998).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds. Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M. F. & Lin, H.) 33, 6840–6851 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2020).

Bhunia, A. K. et al. Person Image Synthesis via Denoising Diffusion Model. In 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Visionand Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 5968–5976 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00578 (IEEE, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023).

Lovelace, J., Kishore, V., Wan, C., Shekhtman, E. & Weinberger, K. Q. Latent diffusion for language generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 56998–57025 (2023).

Li, L., Carver, R., Lopez-Gomez, I., Sha, F. & Anderson, J. Generative emulation of weather forecast ensembles with diffusion models. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk4489 (2024).

Nai, C. et al. Reliable precipitation nowcasting using probabilistic diffusion models. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 034039 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. A ConvNet for the 2020 s. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11966–11976 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01167 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin Transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 9992–10002 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00986 (2021).

Lian, T., Chen, D., Tang, Y. & Wu, Q. Effects of westerly wind bursts on El Niño: a new perspective. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3522–3527 (2014).

Chen, D. et al. Strong influence of westerly wind bursts on El Niño diversity. Nat. Geosci. 8, 339–345 (2015).

Tan, X. et al. A study of the effects of westerly wind bursts on ENSO based on CESM. Clim. Dyn. 54, 885–899 (2020).

Tan, X. et al. Effects of semistochastic westerly wind bursts on ENSO predictability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086828 (2020).

Chen, L., Li, T., Wang, B. & Wang, L. Formation mechanism for 2015/16 super El Niño. Sci. Rep. 7, 2975 (2017).

Li, A., Ji, C. & Fang, X. A new insight on El Niño diversity: decadal variability in westerly wind bursts. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 26, e1301 (2025).

Forecast verification. In Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences 4th edn (ed. Wilks, D. S.) xv https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815823-4.09991-0 (Elsevier, 2019).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Liu, T., Song, X., Tang, Y., Shen, Z. & Tan, X. ENSO predictability over the past 137 years based on a CESM ensemble prediction system. J. Clim. 35, 763–777 (2022).

Song, X. et al. A new nudging scheme for the current operational climate prediction system of the National Marine Environmental Forecasting Center of China. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 41, 51–64 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The research of C.J., Bo Qin, M.M., S.Y., X.F., Y.W., G.D., and J.W. are supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42288101, 42405147, 42192564, and U2142211), the China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (BX20230071), the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (Grant No. 2020YFA0608802), the National Key Scientific and Technological Infrastructure project “Earth System Science Numerical Simulator Facility” (EarthLab) and the Academician Workstation of AP-TCRC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J., B.Q. and X.F. designed the project. C.J., B.Q., and J.F. contributed the model codes. C.J. and B.Q. conducted model experiments. C.J., B.Q. and X.F. wrote the manuscript. C.J., B.Q., M.M., T.L., S.Y., J.F., X.S., Y.W., G.D. and J.W. discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, C., Mu, M., Qin, B. et al. Toward skillful forecasting of super El Niño events using a diffusion-based westerly wind burst parameterization. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 273 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01158-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01158-x

This article is cited by

-

AI-Enabled conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation enhances ensemble prediction of extreme El Niño events

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)