Abstract

While the potential intensity (PI) theory provides a foundation for projecting future tropical cyclone (TC) intensity, uncertainties remain regarding how future TC maximum intensity will change due to potential offsets from interaction between TCs and their ambient environment. Using high-resolution downscaling simulations based on future scenarios from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) Phases 5 and 6, this study examines the relative influence of local environment along TC tracks and large-scale atmospheric conditions on TC lifetime maximum intensity (LMI) in future projections. Analyzing TC intensity distributions for the final two decades of the 21st century in the western North Pacific (WNP) basin shows that the LMI increases in all future scenarios in this basin, despite less favorable local conditions along TC tracks. This increase in LMI is driven by a rise in the occurrence of long-lived TCs and a decline in short-lived TCs, enabling more TCs to reach higher intensities during their lifetime even as local environments become more hostile to TC development in warmer climates. The mechanism behind this LMI increase is linked to a northeastward shift in the Western Pacific Subtropical High, which alters TC track patterns in the WNP basin. These findings highlight the critical role of large-scale environment in TC intensity projections, underscoring the need to move beyond basin-wide PI analyses when assessing future TC activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Future changes in tropical cyclone (TC) intensity are among the most extensively studied topics in TC research. While significant uncertainty remains regarding projections of TC frequency, there is strong consensus that TC intensity will likely increase in a warming climate1,2,3,4,5,6.

Projections of TC intensity are often based on key metrics such as potential intensity (PI), lifetime maximum intensity (LMI), the power dissipation index, or accumulated cyclone energy7,8,9,10,11. Previous studies using these metrics have shown an upward trend in TC intensity under warming conditions, particularly in the western North Pacific (WNP) basin, even under low-emission scenarios12,13,14,15. The consistency of TC intensity projections across multiple metrics and scenarios is noteworthy, as it suggests that TC intensity and associated impacts are expected to increase as the climate warms. Ultimately, this increase in TC intensity is driven by rising sea surface temperatures (SST), which enhance surface fluxes that fuel TC development.

From the climate perspective, the response of TC intensity to SST is rooted in the PI theory16,17, which serves as the foundation for the link between TC intensity and climate. Within this PI framework, a common approach to analyze changes in TC intensity is to compute PI from a given reanalysis dataset or climate model output5,13,18. Using an ensemble of CMIP5 models, Sobel et al. (2019)19 computed PI for multiple simulations and showed that mean PI in the tropics increases in all future scenarios and that the PI is more sensitive to aerosols than greenhouse forcing. This PI-based approach offers a key advantage by leveraging a large number of global climate models and future scenarios, allowing a comprehensive assessment of both the uncertainty and robustness of future TC intensity projections.

A limitation of relying solely on changes in mean PI across a basin or region is that it overlooks potential feedback between TCs and their local environment. Typical PI calculations for future projections are based on monthly mean environmental conditions, which do not account for how an individual TC interacts with its surroundings or whether it would actually intensify under those conditions. In reality, the presence of a TC actively modifies its environment rather than merely responding to large-scale conditions. Local environmental changes, such as the development of a cold wake, enhanced stratification, or localized subsidence warming, can all influence TC intensity in complex, nonlinear ways6,20,21,22,23,24. How these local changes can enhance or offset TC intensification cannot be directly answered by using the monthly or seasonal PI values. In fact, Kossin & Camargo20 examined the trends of PI along Atlantic TC tracks compared with mean Atlantic PI trends and noticed the important role of TC tracks in the along-track PI trends. More recently, Lin et al.15 found that LMI poleward shift can partially cancel global warming’s impact on future TC intensity projections in the WNP basin. Furthermore, Lin et al.25 showed that the observed trend in the latitude at which TCs reach their LMI in the WNP is very unlikely to be caused by internal variability, but that the magnitude of this poleward trend can be significantly modulated by the spatial pattern of ocean warming.

Given the potential interactions between TCs and their environment, this study aims to address two key questions: (i) how TC-environment interactions modify the local environment along TC tracks, and (ii) the consequences of these interactions on future projections of TC maximum intensity. A direct approach to these questions is to simulate TCs along their actual tracks and assess changes in TC maximum intensity under different climate scenarios. In this study, we present a high-resolution dynamical downscaling approach to evaluate environmental changes along storm tracks, focusing on TC actual maximum intensity derived from model simulations rather than relying on basin average PI as in previous studies. By examining how the local environment evolves along TC tracks, this study provides new insights into the relative importance of local versus large-scale environmental factors in controlling TC intensity and its future projections.

Results

Along-track changes

The WNP basin typically experiences the highest annual number of TCs. Of note, WNP TCs tend to exhibit stronger intensity, higher frequency of rapid intensification, and the most significant changes in intensity across both historical and future climates9,13,14,18,26,27,28. As a result, projections of future TC intensity in this basin are generally robust, regardless of the intensity metric used. Given these characteristics, this study focuses on the WNP TC intensity to maximally explore the relative influence of local versus large-scale environment on TC intensity projections. Our primary analyses will be based on LMI as a proxy for TC intensity, as it best captures variations in the local environment along TC tracks and their impacts on storm intensity.

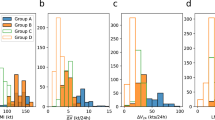

Figure 1 illustrates the LMI and associated environmental conditions along TC tracks from historical CMIP5/6 simulations (1979–2005, hereafter referred to as historical simulations) and four corresponding future periods at the end of the 21st century (2080–2100). One notices that LMI increases across all CMIP5/6 future scenarios, showing a consistent upward trend across experiments (Fig. 1a). However, most key environmental factors for TC development such as the ventilation index, convective available potential energy (CAPE), or tropospheric stability become less favorable along TC tracks, with the exception of warmer SST (Fig. 1d). In particular, two critical factors for TC development including the ventilation index and tropospheric stability increase in all future scenarios along the TC tracks, indicating more adverse conditions for TC intensification in future climates (Fig. 1e, f). Such a contradictory behavior between the increasing LMI and the worsening along-track environment is intriguing, which highlights the complexity of TC-environment interaction in a warming climate in our downscaled simulations.

a the TC lifetime maximum intensity (LMI, unit m s−1, b TC lifetime (unit: day), c genesis latitude (degree), d seas surface temperature (SST, unit: K), e tropospheric static stability (N2 ≡ Γd −Γ, unit K m−1), and f ventilation index (non-dimensional) using the formulation in ref. 29. All averages are computed within an area of 1000 km × 1000 km centered on the WRF model-simulated TC locations along TC tracks. Shaded boxes in a–c are the corresponding averages obtained from the best track during the historical period 1979–2003, and the asterisks denote significant changes in future periods relative to the historical simulations.

We note that the ventilation index encapsulates several key environmental factors, including vertical wind shear, mid-level entropy deficit, and PI. As such, it serves as a comprehensive metric for assessing the favorability of environmental conditions for TC formation and intensification29,30,31. The projected increase in the ventilation index along TC tracks across future periods, as shown in Fig. 1 aligns with the findings of Tang and Camargo32, who reported similar ventilation changes using CMIP5 outputs. In our downscaling simulations, this increase is driven mostly by enhanced vertical wind shear along TC tracks, which differs from the changes of local shear in CMIP5/CMIP6 models or from aquaplanet simulations9,12,14,31,33,34. Nevertheless, the agreement between our findings and previous PI-based assessments reinforces the increasing trend in the ventilation index, which is less favorable for TC development.

Likewise, the tropospheric stratification has also been known to increase in a warmer climate due to faster warming at the upper levels of the troposphere21,22,35,36, consistent with an upward trend of tropopause temperature. Such a more stable troposphere can limit the TC maximum intensity, especially in the absence of absolute moist neutrality, which is in line with the PI framework6,24.

Given the confounding effects of those multiple environmental factors, changes in LMI under future climate conditions represent a complex process that extends beyond the theoretical foundation based on the PI framework. Thus, warmer SST does not necessarily lead to higher LMI values, as its influence may be offset by other unfavorable environmental conditions. In this regard, the observed increase in LMI shown in Fig. 1a is very noteworthy, as it reflects an actual intensity of TCs in future simulations rather than merely an increase in the theoretical upper bound represented by PI. The fact that LMI increases despite a more adverse local environment, as shown in Fig. 1a implies that additional factors must be contributing to TC intensification in a warmer climate, beyond SST warming alone.

Among the factors influencing LMI, the role of TC lifetime remains one of the least understood due to its uncertainties and indirect influence on future projections37. In fact, TC lifetime also plays a significant role in other intensity metrics such as the power dissipation index or accumulated cyclone energy, given the strong dependence of TC intensity on TC track characteristics15,26,38,39,40,41. Consequently, any changes in TC lifetime could affect LMI, even if PI remains unchanged. For instance, an extended TC lifetime over warm tropical regions, where TCs spend more time over the open ocean, would likely result in higher LMI. Similarly, TCs forming in certain latitude zone may have a greater chance of encountering favorable conditions for intensification, thereby increasing LMI without necessary changes in PI. These effects of TC lifetime on LMI can be further amplified during El Niño events, where TC formation shifts southeastward, altering track characteristics and resulting in more long-lived and intense TCs1833,42.

As shown in Fig. 1b, the mean TC lifetime shows however, no significant changes in any future scenarios when compared to the historical simulations, while the genesis latitudes of future TCs are shifted slightly northward across CMIP5/6 scenarios. This behavior of TC lifetime further highlights the intriguing question of how LMI could increase in future climates while all key atmospheric environments for TC development become less favorable. One possibility is the expansion of the area favorable to TC intensification poleward, but this is not straightforward in our downscaled simulations herein as it depends on the presence of simultaneous changes in genesis and tracks as discussed in, e.g., ref. 15.

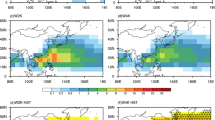

To further investigate this question, Fig. 2 presents the distribution of TC lifetimes during historical and future scenarios. While the 20-year average TC lifetime does not exhibit statistically significant changes in the mean, noticeable shifts appear in the tails of the TC lifetime distributions. Specifically, in most future scenarios (except for SSP245), there is a 5–10% reduction in short-lived TCs (defined as those with a lifetime of fewer than five days) and a 10–17% increase in long-lived TCs (greater than five days) under warmer climate conditions.

a TC lifetime distribution as obtained from the WRF downscaling experiments for the CMIP5/CMIP6 historical period (solid and dashed black), RCP45/RCP85 (blue/orange), SSP245/SSP285 (cyan/red), and corresponding best track distribution during the 1979–2003 period (thick gray); b Averaged number of short-lived TCs (lifetime ≤ 5 days) for best track (black column), downscaled CMIP5 (blue columns) and CMIP6 (grey columns), and c Similar to b but for the long-lived TCs (lifetime > 5).

Although these changes at the tail of the TC lifetime distribution have negligible effects on the mean or median of the TC lifetime due to their small contribution to the overall statistics (see Fig. 2b, c, they could lead to a more notable change in LMI, given the strong dependence of LMI on the duration of a TC over open water. Specifically, the increase in the occurrence of long-lived TCs in the future allows TCs to remain over the ocean for a longer time, thereby increasing their likelihood of reaching higher intensities, particularly when they persist over warmer SST regions favorable for intensification (Fig. 1d).

Similarly, a reduction in short-lived TCs implies that storms with lower LMI values will contribute less to the climatological average in the future climate. Such a relationship between LMI and TC lifetime is indeed illustrated in Fig. 3, which presents the scatter plot of these two variables. Although their exact relationship cannot be determined from the scatter plot alone, the Spearman rank correlation between LMI and TC lifetime is consistently above 0.5 across all historical and future periods, supporting the hypothesis that TC lifetime can strongly influence LMI. Together, the net effects of fewer short-lived TCs and more long-lived TCs may drive the overall increase in LMI, as shown in Fig. 1b.

While a higher LMI value generally means that a sufficiently longer lifetime is needed for a TC to reach its high maximum intensity, caution should be taken here. Specifically, a very long-lived TC will not necessarily have a higher LMI value, as TCs often weaken as they move into a colder SST, reaching their PI limit during their lifetime, or make landfall. This can be seen in Fig. 3, which shows the plateau of LMI for TC lifetimes > 10 days in both historical and future periods. Therefore, it is the reduction in the occurrence of short-lived TCs in the range of 3-5 days that is more influential to LMI than the increase of very long-lived TCs.

Large-scale controls

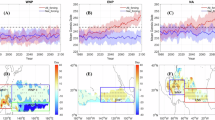

If changes in the tail of the TC lifetime distribution could lead to an increase in LMI despite unfavorable along-track conditions for TC development, as observed in Fig. 1, a natural question arises: what is driving these changes in the TC lifetime distribution? To address this, Fig. 4 compares three TC track clusters in the WNP basins across downscaled CMIP5/6 future scenarios and historical simulations. The most notable change in these track patterns is a shift in the two main TC track clusters in the East Philippine Sea, which recur more frequently toward the open ocean in warmer climates compared to the historical period (see also Fig. S3, Supporting Information). Additionally, the location of these clusters shifts eastward in the future climate, particularly for the downscaled CMIP6 tracks.

In fact, one can quantify these changes by looking at the difference in the track density between the downscaled future and historical periods (Fig. 5). As can be seen in this figure, there are more (fewer) TC tracks in the northern (southern) part of the WNP basin in all future scenarios, with some localized small areas displaying a statistical significance at 95% level. These shifts in TC track patterns and density offer some explanation for the change in TC lifetime, as TCs forming in the East Philippine Sea can now stay over the ocean for a longer time instead of crossing the Philippines and being dissipated. This change in TC track clusters is robust in our sensitivity analysis (see Figure S5–S7 in SI), thus supporting the higher averaged LMI even though the conditions along TC tracks are less favorable as seen in Fig 1.

Such a systematic change in TC track patterns suggests that the large-scale circulation that governs TC tracks in the WNP basin must change accordingly as well. One of the key large-scale systems controlling TC tracks in this basin is the western North Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH)39,41,43,44,45,46. As shown in previous studies, the steering flow on the southern flank of the WPSH is well aligned with the dominant tracks in the WNP basin. Any shift in the magnitude or location of the WPSH in response to future climate change will therefore accompany corresponding changes in TC tracks and related climatological TC characteristics.

To examine these changes in WPSH, Fig. 6 compares the mean location and magnitude of the WPSH between the historical period and four future scenarios, defined as 500-hPa geopotential height anomalies averaged between July and October. It can be seen that there is a noticeable northward shift in the WPSH location as well as a retreat to the east during the Northern Hemisphere TC season in warmer climates, as previously reported12,34,39, consistent with the northward shift in the TC genesis latitude in Fig. 1c. These changes lead to a weakening of the easterly flow at the WPSH’s southern flank. As a result, TCs forming in the far east of the Philippine Sea tend to recurve to the north instead of being steered west-northwesterly, leading to more long-lived TCs in future scenarios.

(a) RCP45, (b) RCP85, (c) SSP245, and (d) SSP585. Here, the WPSH anomalies are defined to be the deviation of the mean 500–hPa geopotential height relative to the domain average. Superimposed is the corresponding horizontal wind difference between each future scenario and the historical period at the same 500 hPa level.

We note that these changes in WPSH are very persistent during the entire July-October season and can be further related to the Hadley circulation37,47,48,49,50. From the perspective of TC climatology, an ultimate consequence of these changes in large-scale circulation is that TCs can now have more time over the open ocean to intensify. Along with a northeastward shift in the TC genesis location, the related changes in the tails of the TC lifetime distribution could therefore offer an explanation for an overall higher LMI in the future, even within more adverse environmental conditions as obtained here. Note that these environmental and TC lifetime changes in our downscaled simulations are very similar to those observed during El Niño- events and present in CMIP5/6 models' simulations51. However, several recent studies52,53,54 also pointed out that CMIP5/6 models struggle to reproduce the observed historical trends in the tropical Pacific mean state. As such, any link between these large-scale environmental changes to El Niño-type conditions in future projections of TC intensity would raise some concerns about their robustness55, which is outside the scope of this study.

Discussion

In this study, high-resolution dynamical downscaling of CMIP5/6 projections for the WNP basin was analyzed to examine changes in the lifetime maximum intensity of model-simulated TCs. Our analyses, which followed the simulated TC tracks, consistently showed an upward trend in LMI across all future scenarios, despite less favorable conditions for TC intensification along the projected tracks. This increase in LMI is linked to the shifts in the large-scale circulations associated with the WNP subtropical high, which cause systematic changes to TC track patterns and allow TCs to persist over the open ocean for long periods.

In addition to the changes in the subtropical high, an eastward shift in TC genesis regions was also captured in our downscaling simulations, thus resulting in fewer short-lived but more long-lived TCs, typical of El-Niño like projections present in CMIP5/6 models. As a result of these large-scale effects on TC tracks and duration, the average LMI could increase, even when the local environment along TC tracks becomes less conducive to intensification.

Unlike previous studies based on basin-averaged PI projections, we used LMI that is computed along each model-simulated TC track in our dynamic downscaling experiments. Such a focus on along-track LMI in this study is because we want to examine the actual maximum intensity that a TC can obtain in a given climate condition, instead of a theoretical upper bound obtained from a prescribed climate environment. As mentioned in the Introduction, PI projections are passively constrained by input climate conditions without taking into account feedbacks from TCs to their surrounding environment. This one-way nature of PI projections justifies the usefulness and applicability of projections and diagnostics within the PI framework for different climate scenarios. In contrast, LMI projections are explicitly dependent on TC tracks and specific downscaling experiments. Therefore, LMI projections are sensitive to TC-environment interactions as well as the variability of large-scale circulations controlling TC tracks for which PI-based projections cannot fully capture.

Although the results herein were derived from a single WRF downscaling configuration, which may raise concerns about model biases and representativeness, we wish to emphasize that our primary objective in this study was to explore possible realizations of future LMI based on CMIP5/6 emissions scenarios and how such LMI changes are connected to TC-following and the large-scale environment. In all downscaling experiments, the WRF model consistently captured less favorable environmental conditions along TC tracks across future periods. This suggests that the tropical atmosphere can develop a counteracting effect on TC maximum intensity at a larger scale, an aspect that cannot be fully understood by relying solely on warmer sea surface temperatures or local environmental conditions. This underscores the importance of considering broader atmospheric dynamics when assessing future TC changes, as recently discussed in refs. 15,34 as well as systematic model biases across the CMIP5/6 ensembles in ref. 52.

As a final note, we emphasize that the results presented in this study are specific for WRF-simulated environmental conditions, which potentially differ from those derived directly from the CMIP5/6 data due to biases inherent in the WRF model. Given the additional variability in downscaled TC tracks in any regional model simulations, our findings should therefore be interpreted as one possibility for changes in LMI that is conditional on these WRF model tracks and environmental fields. Since TC tracks vary across models and are sensitive to SST patterns56, the question of how LMI might additionally change under different SST patterns or modeling systems25,55,57 remains open.

Methods

Dynamical downscaling

In this study, we employed a homogeneous-resolution configuration of the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model (version 3.9)58 to dynamically downscale future scenarios from CMIP5/6, following the approach used in ref. 37. Specifically, the WRF model was run at a uniform horizontal resolution of 9 km for a domain covering a broad region of the North Pacific basin ([80oW–180oW] × [5oS-45oN]), suitable for downscaling TC climatology in the WNP basin as expected. Our choice of using a single-resolution domain, rather than a nested configuration as in previous studies, was to eliminate resolution gaps and discontinuities in TC-environment interaction that may arise between nested domains or during the movement of storm-following nests.

In general, the main drawback of using such a single homogeneous resolution for dynamical downscaling is that the model domain cannot be set too large due to the high computational cost and large output storage requirements. In addition, there is a possible jump in the model resolution when directly downscaling from the 1-degree global CMIP5/6 input to the 9-km resolution of the regional WRF model. These drawbacks can be overcome by adopting the continuous downscaling approach instead of re-initializing the model at a fixed interval59,60,61. Note that regularly re-initializing the model is a good approach to avoid a possible model drift during long integration. However, this re-initialization downscaling approach would lead to a frequent model spin-up issue when constantly interpolating the CMIP5/6 data for model initial conditions, and so it is not suitable for our TC intensity downscaling. This is especially an issue for TC simulations, as it prevents us from obtaining the proper LMI when TCs are sufficiently strong due to the WRF model’s initial adjustment. With the lateral boundary updated continuously every 6 hours, our continuous downscaling from May 1 to November 31 of each year is therefore a better choice, as it suffices to avoid the model drift issue via lateral boundary control.

Specific to the CMIP5 downscaling, our WRF model output was taken from the study37, which was initialized with the bias-corrected CESM global output62. For the CMIP6 downscaling, the multi-model bias-corrected average of 18 models provided by Xu et al.63 was used. Our main purpose in using these different CMIP5/6 datasets for downscaling experiments in this study is to provide as much diversity as possible for future climates, which helps increase the robustness of the results. Another reason for using such a different CMIP5/6 global input is that these global products are made available in the WRF intermediate format, which allows us to set up and carry out model simulations readily.

For the validation and optimization of the WRF downscaling, we conducted a historical period 1979-2003 for both the CMIP5/6 data which can serve as a reference for the present-day climate. Much of the CMIP5 validations are presented in37 and similarly for CMIP6 and so they will not be repeated here (see Figs S1-S2, Supporting Information). Note that CMIP5 and CMIP6 are designed differently for both the past and future periods. As such, a separate historical climate for CMIP5/6 must be conducted to examine future changes relative to their corresponding historical period. Regarding future scenarios, we conducted experiments for the end of the 21-century period (2080-2100) under RCP4.5/RCP8.5 with CMIP5, and SSP245/SSP585 with CMIP6. By default, a one-dimensional column ocean layer was used to capture the air-sea interaction and potential cold wake effects in all experiments as discussed in34.

Given the output from WRF simulations, the validation process for TC downscaling can be analyzed against the best track data based on several TC metrics such as frequency, LMI, spatial track distribution, genesis density, and lifetime, as shown in the Supporting Information. Note that any dynamical downscaling contains different types of model errors and biases. Thus, calibrating TC downscaled climatology based on one metric will generally cause biases in other metrics that one has to compromise37. For example, by varying the vortex tracking criteria or using other global input data, we can reduce the biases in the total number of TCs during the historical period, but this increases the bias in TC track density. Likewise, we can also tune the vortex tracking algorithm to get a better track density distribution at the expense of TC lifetime climatology. As such, the validation of downscaled products will depend on each specific aim that we have to compromise.

For the purpose of calibrating the model performance that focuses on LMI and TC lifetime as presented in this study, we optimized our model configuration and the vortex tracking such that the downscaled TC lifetime can best fit to the observed lifetime during the historical period as in ref. 37 instead of TC track density or occurrence. In this regard, the biases in the TC genesis or occurrence distribution are to some extent unavoidable and a trade-off that we have to make for our LMI and TC lifetime focus, regardless of what global input or regional model settings are used.

It is important to note that our dynamical downscaling approach in this study does have some limitations that are worth emphasizing. First, our approach uses a single CMIP5 member and a multi-model average from CMIP6 as input. As such, it may not fully capture the entire spectrum of possible future climate conditions. Nonetheless, these CMIP5/6 inputs could still allow us to generate sufficiently diverse realizations of the tropical atmosphere, which are needed to assess their influence on TC intensity under hypothetical climates that are dynamically and thermodynamically consistent. Thus, the consistent behavior of the LMI across our experiments, as demonstrated in this study, indicates that the projected changes in LMI could at least provide some robust outcomes, regardless of the specific CMIP5 member or CMIP6 models used for our downscaling.

Second, any WRF downscaling simulations will inherently drift away from global input after some integration period due to the regional model’s internal biases. While such a regional model drift is certainly critical for TC forecasting purposes64,65, it has less impact on our main aim in this study, which tracks individual TCs to assess the relative influence of along-track environment versus the large-scale environment on LMI. So long as our analysis remains focused on comparing these two environments within the downscaled simulations, such large-scale drifts in the WRF downscaling are expected to have minimal effects on the relative roles between the local and large-scale environments. In this regard, this drift should not compromise the validity of our results, provided that a sufficiently large sample of TCs is analyzed.

Along-track environments

For our purpose of computing local environments along a simulated TC track in this study, a domain size of 1000 × 1000 km around each detected TC center was used, which is sufficient to include the key effects of TC-environment interaction. Because of the presence of TCs in this domain, it is important to remove TC structures in the domain such that any direct interference of TC-related structures on the local environments can be minimized. This is important for several environmental metrics such as vertical wind shear, ventilation index, or tropospheric stratification, for which the existence of TC may mask out some local environmental properties that we wish to extract.

For this vortex removal procedure, we implemented a variant of the vortex removal technique that is based on the algorithm proposed by Kurihara et al.66. In our scheme, a meteorological variable x in the domain is first split into a mean xB and a perturbation \({x}^{{\prime} }\) using a filtering operator as follows:

Next, the vortex information xv is removed from the perturbation \({x}^{{\prime} }\) using the so-called Gaussian kernel that is centered at the TC center. Finally, the environmental field xE is reconstructed by combining the mean and the non-TC perturbation component as:

Note that the filtering operator in Eq. (1) is similar to that used in ref. 66. This operator is iterated first in the zonal direction with a prescribed number of iterations as follows:

where (i, j) denote the zonal and meridional indices, respectively, and the filtering coefficient Km is defined as:

where m ∈ [2, 3, 4, 2, 5, 6, 7, 2, 8, 9, 2] changes for each iteration. This same filtering operator is then applied one more time in the meridional direction to obtain the final basic field xB:

Note that unlike the original scheme that used the cylindrical filter66, we applied a simpler two-dimensional Gaussian kernel KG centered at the filtering domain to obtain the vortex field as follows:

where \({K}_{G}(i,j)=\exp \left(-\frac{{({i}^{2}+{j}^{2})}^{\lambda }}{2{\sigma }^{2}}\right)\), and ⊙ operator denotes element-wise multiplication. Here, the parameter σ specifies the horizontal scale of the vortex (set to 500 km), while λ defines the shape of the filter within the radius σ, with a default value of 4.

Practically, this Gaussian filter produces similar outcome within the radius of 1.5σ but with a slower cut-off outside as compared to the cylindrical filter E(r) in ref. 66. However, the effectiveness of our Gaussian filter is much easier to control by varying the parameters σ, λ, which suffice for our vortex filtering as demonstrated in Fig. S8-S9 of the Supporting Information. Note that the whole vortex removal procedure changes for each TC stage, because TC signals are progressively more distinct for higher intensities. The verification of our vortex removal scheme for several stages of TC development is provided in the Supporting Information, which confirms the effectiveness of this approach in removing TC vortex within a given domain for computing local environments.

Cluster analysis

To stratify TC tracks in the WNP basin into different clusters, we followed the approach of Camargo et al.18 and conducted cluster analyses using the finite mixtures of regression models67 with a polynomial regression model of order 2. Specifically, we first assumed that each TC track was generated by K different regression models, where K = 3 to avoid poor local maxima in the parameter space.

The cluster-selection procedure then proceeded with learning the parameters of these K models based on a given set of TC tracks. For each TC track, one can infer which of the K models is most likely to be used. The expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm was also used to find the local maxima of the likelihood, with the number of EM steps set to 10. Finally, the cluster is assigned the highest posterior probability, given a track associated with that TC. These cluster analyses were applied to two historical periods produced by CMIP5/6 scenarios for which four future periods from 2080-2100 towards the end of the 21st century under RCP45/RCP84 and SSP245/SSP585 scenarios are downscaled as described in the previous section. More details of this cluster analysis, as well as its related applications, can be found in refs. 18,67.

Vortex tracking algorithm

Given the output from the WRF downscaling, a necessary step for our analyses is to have an efficient vortex tracking algorithm. There exist many different versions of TC tracking algorithms, which are all built around key TC characteristics such as sea level pressure, vorticity, warm core magnitude, the maximum wind speed, or duration68,69,70,71,72,73.

A common characteristic of all TC-tracking schemes is their sensitivity to vortex detection thresholds and model resolution. For instance, Walsh et al.74 found that a 10-m maximum wind speed threshold of 17.5 ms−1 is suitable for high-resolution models with grid spacing below 10 km. In contrast, for coarser grids—such as 30 km or 125 km—a lower threshold of 17 ms−1 or approximately 14.5 ms−1, respectively, is more appropriate. These results underscore the need to empirically adjust detection thresholds, such as wind speed or other variables, according to model resolution in order to accurately identify TC vortices. Alternatively, some studies (e.g., refs. 75,76) propose simplifying the tracking procedure by focusing on key parameters like surface pressure and warm-core characteristics. This approach reduces the dependency on surface wind speeds, which are more susceptible to resolution-induced variability.

Because of such sensitivity of the TC tracking algorithm to specific models and configurations, we employed in this study the same vortex tracking algorithm as in refs. 34,37, which is specifically tailored to our 9-km WRF downscaling output and resolution as previously reported. Details of this tracking algorithm can be found in refs. 34,37, and so will not be repeated here. For this study, the specific thresholds for the vortex tracking are provided in Table 1. Validation as well as sensitivity analyses for our vortex tracking can be found in the Supporting Information.

Data availability

All data generated in this study can be reproduced using the WRF model (V3.9) and model configurations described in the Method section and Vu et al. (2024). The post-processed data, including TC track and other statistics used to produce all results in this work, is provided at https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17213.37606.

References

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change. Nat. Geosci. 3, 157–163 (2010).

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones in a warming world. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, 771–774 (2020).

Vecchi, G. et al. Tropical cyclone sensitivities to CO2 doubling: Roles of atmospheric resolution, synoptic variability and background climate changes. Clim. Dyn. 53, 5999–6033 (2019).

Sobel, A. H. et al. Tropical cyclone frequency. Earth’s Future 9, e2021EF002275 (2021). E2021EF002275 2021EF002275.

Camargo, S. J. et al. An update on the influence of natural climate variability and anthropogenic climate change on tropical cyclones. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 12, 216–239 (2023).

Kieu, C., Zhao, M., Tan, Z., Zhang, B. & Knutson, T. On the role of sea surface temperature in the clustering of global tropical cyclone formation. J. Clim. 36, 1–39 (2023).

Emanuel, K. A. Tropical cyclones. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 31, 75 (2003).

Emanuel, K. A. Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature 436, 686–688 (2005).

Kossin, J. P., Emanuel, K. A. & Camargo, S. J. Past and projected changes in western north pacific tropical cyclone exposure. J. Clim. 29, 5725 – 5739 (2016).

Vecchi, G. A., Swanson, K. L. & Soden, B. J. Whither hurricane activity? Science 322, 687–689 (2008).

Bell, G. D. et al. Climate assessment for 1999. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 81, S1–S50 (2000).

Murakami, H., Mizuta, R. & Shindo, E. Future changes in tropical cyclone activity projected by multi-physics and multi-SSS ensemble experiments using the 60-km-mesh MRI-AGCM. Clim. Dyn. 39, 2569–2584 (2012).

Bell, S. S. et al. Western north pacific tropical cyclone tracks in cmip5 models: Statistical assessment using a model-independent detection and tracking scheme. J. Clim. 32, 7191–7208 (2019).

Tang, Y., Huangfu, J., Huang, R. & Chen, W. Simulation and projection of tropical cyclone activities over the western north Pacific by CMIP6 HighResMIP. J. Clim. 35, 7771–7794 (2022).

Lin, I., Camargo, S. J., Lien, C.-C., Shi, C.-A. & Kossin, J. P. Poleward migration as global warming’s possible self-regulator to restrain future western north pacific tropical cyclone’s intensification. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 34 (2023).

Emanuel, K. A. An air-sea interaction theory for tropical cyclones. Part I: Steady-state maintenance. J. Atmos. Sci. 43, 585–605 (1986).

Emanuel, K. A. The maximum intensity of hurricanes. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 1143–1155 (1988).

Camargo, S. J., Robertson, A. W., Gaffney, S. J., Smyth, P. & Ghil, M. Cluster analysis of typhoon tracks. Part I: General properties. J. Clim. 20, 3635–3653 (2007).

Sobel, A. H., Camargo, S. J. & Previdi, M. Aerosol versus greenhouse gas effects on tropical cyclone potential intensity and the hydrologic cycle. J. Clim. 32, 5511–5527 (2019).

Kossin, J. P. & Camargo, S. J. Hurricane track variability and secular potential intensity trends. Clim. Change 97, 329–337 (2009).

Hill, K. A. & Lackmann, G. M. The impact of future climate change on TC intensity and structure: A downscaling approach. J. Clim. 24, 4644–4661 (2011).

Downs, A. & Kieu, C. A look at the relationship between the large-scale tropospheric static stability and the tropical cyclone maximum intensity. J. Clim. 33, 959–975 (2020).

Ferrara, M., Groff, F., Moon, Z., Robeson, S. & Kieu, C. Climatological connection of tropical cyclone intensity and the tropopause variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. (2016).

Kieu, C. Q. & Wang, Q. Stability of tropical cyclone equilibrium. J. Atmos. Sci. 74, 3591–3608 (2017).

Lin, J., Lee, C.-Y., Camargo, S. J. & Sobel, A. Poleward migration of the latitude of maximum tropical cyclone intensity-forced or natural? J. Clim. 37, 5453 – 5463 (2024).

Manganello, J. V. et al. Future changes in the western north pacific tropical cyclone activity projected by a multidecadal simulation with a 16-km global atmospheric GCM. J. Clim. 27, 7622 – 7646 (2014).

Thanh, N. T., Cuong, H. D., Hien, N. X. & Kieu, C. Relationship between sea surface temperature and the maximum intensity of tropical cyclones affecting Vietnam’s coastline. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 2527–2538 (2020).

Tran-Quang, D., Pham-Thanh, H., Vu, T.-A., Kieu, C. & Phan-Van, T. Climatic shift of the tropical cyclone activity affecting Vietnam’s coastal region. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 59, 1755 – 1768 (2020).

Tang, B. & Emanuel, K. Midlevel ventilation’s constraint on tropical cyclone intensity. J. Atmos. Sci. 67, 1817–1830 (2010).

Tang, B. & Emanuel, K. Sensitivity of tropical cyclone intensity to ventilation in an axisymmetric model. J. Atmos. Sci. 69, 2394–2413 (2012).

Chavas, D. R., Camargo, S. J. & Tippett, M. K. Tropical cyclone genesis potential using a ventilated potential intensity. J. Clim. 38, 1667–1689 (2025).

Tang, B. & Camargo, S. J. Environmental control of tropical cyclones in CMIP5: A ventilation perspective. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 6, 115–128 (2014).

Wang, B. & Chan, J. C. L. How strong enso events affect tropical storm activity over the western North Pacific. J. Clim. 15, 1643–1658 (2002).

Vu, T.-A., Kieu, C., Chavas, D. & Wang, Q. A numerical study of the global formation of tropical cyclones. Adv. Modeling Earth Syst. 13, e2020MS002207 (2021).

Ferrara, M. et al. Large-scale control of the lower stratosphere on variability of tropical cyclone intensity. Geophys. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2017GL073327 (2017).

Sohn, B.-J., Lee, S., Chung, E.-S. & Song, H.-J. The role of the dry static stability for the recent change in the Pacific Walker circulation. J. Clim. 29, 2765–2779 (2016).

Vu, T.-A., Kieu, C., Robeson, S. M., Staten, P. & Kravitz, B. Climate projection of tropical cyclone lifetime in the western north Pacific basin. J. Clim. 38, 181–201 (2025).

Chan, J. C. L. & Liu, K. S. Global warming and western north pacific typhoon activity from an observational perspective. J. Clim. 17, 4590–4602 (2004).

Murakami, H., Wang, B. & Kitoh, A. Future change of western north pacific typhoons: Projections by a 20-km-mesh global atmospheric model. J. Clim. 24, 1154–1169 (2011).

Lee, H. et al. Future change in tropical cyclone activity over the western north Pacific in CORDEX-East Asia multi-rcms forced by HadGEM2-ao. J. Clim. 32, 5053–5067 (2019).

Hong, C.-C. et al. Future changes in tropical cyclone intensity and frequency over the western North Pacific based on 20-km HIRAM and MRI models. J. Clim. 34, 2235–2251 (2021).

Camargo, S. J. & Sobel, A. H. Western North Pacific tropical cyclone intensity and ENSO. J. Clim. 18, 2996–3006 (2005).

Tao, S. Y. & Chen, L. X. A review of recent research on the east asian summer monsoon in China. Monsoon Meteorol. 60–92. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:127096617 (1987).

Yihui, D. & Chan, J. The east asian summer monsoon: An overview. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 89, 117–142 (2005).

Ho, C.-H., Baik, J.-J., Kim, J.-H., Gong, D.-Y. & Sui, C.-H. Interde–cadal changes in summertime typhoon tracks. J. Clim. 17, 1767–1776 (2004).

Wu, L., Wang, B. & Geng, S. Growing typhoon influence on East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L18703 (2005).

Lu, J., Vecchi, G. A. & Reichler, T. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34 (2007).

Vecchi, G. A. & Soden, B. J. Global warming and the weakening of the tropical circulation. J. Clim. 20, 4316–4340 (2007).

Gastineau, G., Li, L. & Treut, H. L. The Hadley and Walker circulation changes in global warming conditions described by idealized atmospheric simulations. J. Clim. 22, 3993–4013 (2009).

Chung, P.-H., Sui, C.-H. & Li, T. Interannual relationships between the tropical sea surface temperature and summertime subtropical anticyclone over the western north Pacific. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 116, D13111 (2011).

Cai, W. et al. Changing el niño-southern oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Seager, R., Henderson, N. & Cane, M. Persistent discrepancies between observed and modeled trends in the tropical Pacific Ocean. J. Clim. 35, 4571–4584 (2022).

Wills, R. C. J., Dong, Y., Proistosecu, C., Armour, K. C. & Battisti, D. S. Systematic climate model biases in the large-scale patterns of recent sea-surface temperature and sea-level pressure change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100011 (2022).

Lee, S. et al. On the future zonal contrasts of equatorial Pacific climate: Perspectives from observations, simulations, and theories. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 628–644 (2022).

Sobel, A. H. et al. Near-term tropical cyclone risk and coupled earth system model biases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2209631120 (2023).

Nakamura, J. et al. Western North Pacific tropical cyclone model tracks in present and future climates. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 122, 9721–9744 (2017).

Zhao, M. & Knutson, T. Crucial role of sea surface temperature warming patterns in near-term high-impact weather and climate projection. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 130 (2024).

C. Skamarock, W. et al. A description of the advanced research WRF version 2. NCAR Monogr. NCAR/TN-468+STR, 1–100 (2005).

Qian, J.-H., Seth, A. & Zebiak, S. Reinitialized versus continuous simulations for regional climate downscaling. Month. Weather Rev. 131, 2857–2874 (2003).

Kotlarski, S., Hagemann, S., Krahe, P., Podzun, R. & Jacob, D. The Elbe River flooding 2002 as seen by an extended regional climate model. J. Hydrol. 472-473, 169–183 (2012).

Lucas-Picher, P., Boberg, F., Christensen, J. H. & Berg, P. Dynamical downscaling with reinitializations: A method to generate finescale climate datasets suitable for impact studies. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 1159–1174 (2013).

Bruyere, C. L., Done, J. M., Holland, G. J. & Fredrick, S. Bias corrections of global models for regional climate simulations of high-impact weather. Clim. Dyn. 43, 1847–1856 (2014).

Xu, Z., Ying, H. & Zongliang, Y. Dynamical downscaling of regional climate: A review of methods and limitations. Sci. China Earth Sci. 62, 365–375 (2019).

Tallapragada, V. & Kieu, C. Real-time forecasts of typhoon rapid intensification in the North Western Pacific Basin with the NCEP Operational HWRF Model. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 3, 63–77 (2014).

Liu, H.-Y. et al. Predictability of the most long-lived tropical cyclone Freddy (2023) during its westward journey through the southern tropical indian ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105729 (2023).

Kurihara, Y., Bender, M. A. & Ross, R. J. An initialization scheme of hurricane models by vortex specification. Month. Weather Rev. 121, 2030–2045 (1993).

Gaffney, S., Robertson, A., Smyth, P., Camargo, S. & Ghil, M. Probabilistic clustering of extratropical cyclones using regression mixture models. Clim. Dyn. 29, 423–440 (2007).

Phan-Van, T., Trinh-Tuan, L., Bui-Hoang, H. & Kieu, C. Seasonal forecasting of tropical cyclone activity in the coastal region of Vietnam using regcm4. 2. Clim. Res. 62, 115–129 (2015).

Walsh, K. J. E. et al. Hurricanes and climate: The U.S. CLIVAR working group on hurricanes. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 997–1017 (2015).

Strachan, J., Vidale, P. L., Hodges, K., Roberts, M. & Demory, M.-E. Investigating global tropical cyclone activity with a hierarchy of agcms: The role of model resolution. J. Clim. 26, 133–152 (2013).

Camargo, S. J. & Zebiak, S. E. Improving the detection and tracking of tropical cyclones in atmospheric general circulation models. Weather Forecast. 17, 1152–1162 (2002).

Camargo, S. J. Global and regional aspects of tropical cyclone activity in the CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 26, 9880–9902 (2013).

Horn, M. et al. Tracking scheme dependence of simulated tropical cyclone response to idealized climate simulations. J. Clim. 27, 9197–9213 (2014).

Walsh, K. J. E., Fiorino, M., Landsea, C. W. & McInnes, K. L. Objectively determined resolution-dependent threshold criteria for the detection of tropical cyclones in climate models and reanalyses. J. Clim. 20, 2307–2314 (2007).

Chavas, D. R. & Reed, K. A. Dynamical aquaplanet experiments with uniform thermal forcing: system dynamics and implications for tropical cyclone genesis and size. J. Atmos. Sci. 76, 2257–2274 (2019).

Ullrich, P. & Zarzycki, C. Tempestextremes v1.0: A framework for scale-insensitive pointwise feature tracking on unstructured grids. Geosci. Model. Dev. 10, 1069–1090 (2017).

Acknowledgements

CK is partially supported by research grants from NSF (AGS-2309929) and ONR/TCRI (N000142012411).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K. conceived the ideas and drafted the manuscript, S.C. contributed to the track cluster techniques and L.M.I. downscaling/tracking analyses, and H.N. conducted the experiments and produced the related analyses and figures. All authors reviewed and contributed to editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kieu, C., Camargo, S.J. & Nguyen, H. Environmental controls on future projections of western North Pacific tropical cyclone maximum intensity. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 331 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01214-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01214-6