Abstract

In recent decades, the northeast Pacific (NEP) has experienced multiple long-lasting and intense marine heatwaves (MHWs), which have significantly impacted both local ecosystems and climate in nearby regions. This study investigates the remote effects of NEP MHWs during early winter on downstream regions, particularly the North Atlantic and western Europe. First, we identify 14 MHWs in the NEP from 1981 to 2023, with peak day (i.e., the day when MHWs reach maximum intensity) occurring between November and December. Our results show that after the peak day, the ocean transfers heat to the atmosphere via surface heat fluxes, accompanied by positive diabatic heating anomalies in the lower troposphere. The diabatic heating anomalies induce a reversal in the low-level atmospheric circulation, transforming from high-pressure anomalies before the peak of the MHWs to large-scale low-pressure anomalies thereafter. Moreover, the low-pressure anomalies are also present in the upper troposphere after the peak. Accordingly, precipitation along the west coast of North America increases, which is associated with the intensification and northeastward extension of atmospheric rivers. Then, atmospheric Rossby waves are stimulated, due to increased precipitation and related circulation anomalies, and travel across the Atlantic to arrive in western Europe. The development of high-pressure anomalies in southern Europe and low-pressure anomalies in the central North Atlantic results in anomalous warm advection, which largely contributes to the warmer-than-normal temperatures in western Europe. Finally, we employ an atmospheric linear baroclinic model and the Community Atmosphere Model version 5.0 to evaluate the aforementioned teleconnection mechanisms. Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the linkage between NEP MHWs and temperatures in western Europe, providing an example of the remote climatic impacts that can be modulated by MHWs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The northeast Pacific (NEP) has experienced several intense and long-lasting marine heatwaves (MHWs) in recent years1,2, which have affected marine ecosystems3 and climate in nearby regions4,5. For example, from 2013 to 2015, a long-lasting and record-breaking MHW event in the NEP, also called “The Blob”1,6, resulted in decreased primary productivity7, alterations in marine species8, stranding of seabirds9, and harmful algal blooms10, with significant economic repercussions11. Another impactful MHW event in the NEP occurred from 2019 to 20202,12, which also had substantial consequences13. With the influence of global warming, there are increasing concerns that NEP MHW events will become more frequent and intense in the future14,15, necessitating more attention and in-depth investigation of their local and remote influences.

A combination of oceanic and atmospheric processes has been recently shown to synergistically stimulate MHWs in the NEP16,17,18. Previous studies reported that atmospheric circulation anomalies are primary factors that trigger wintertime MHWs in the NEP, particularly the high-pressure anomaly (i.e., anomalous ridge) over the Gulf of Alaska1,19. In winter, the high-pressure anomaly induces easterly wind anomalies to its south and counteracts the prevailing westerly winds. This reduces surface evaporation and weakens cold oceanic advection, leading to an increase in the ocean mixed-layer temperature which can facilitate the development of a MHW2,16. Regarding the formation of high-pressure anomalies in winter, numerous studies have been conducted from the tropical20,21,22,23, mid-latitude19, and polar perspectives24,25. For example, in mid-latitude regions, diabatic heating anomalies caused by precipitation anomalies in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean can excite atmospheric Rossby waves, leading to the formation of an anomalous high-pressure ridge over the NEP19.

Previous studies indicated that atmospheric circulation anomalies influencing NEP MHWs can also modulate the climate of downstream regions. For example, the intense high-pressure anomalies over the NEP during the 2013–2015 MHW event contributed to an unusually warmer-than-normal winter in Alaska5 and a notably colder winter in the Great Plains4. However, studies on how NEP MHWs influence downstream areas remain limited. Specifically, the remote climatic effects of NEP MHWs on the Eurasian continent and the causal mechanisms have yet to be explored.

Climate conditions across Eurasia play a crucial role in agricultural production, vegetation growth, commodity supply and demand, and human life and health26,27,28,29,30. Previous studies have shown that the North Atlantic Oscillation profoundly influences European winter temperatures31, with its positive phase associated with warmer and wetter winters in Europe32. Dynamically, the strengthening of the North Atlantic southwesterly winds associated with the North Atlantic Oscillation, along with the warm ocean currents, significantly influences winter temperatures in western Europe33. On the other hand, atmospheric blocking in the North Atlantic is also important in affecting winter temperatures in western Europe through horizontal temperature advection and outgoing longwave radiation34,35. Moreover, with the profound Arctic amplification, the connection between the warmer Arctic and colder Europe in boreal winter has gradually strengthened36. While some studies paid attention to the relationship between the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and winter European climate37, few have investigated the remote relationship between sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) in the NEP and temperatures in Europe during boreal winter.

Motivated by above, this study investigates the downstream influences of NEP MHWs on boreal winter temperature changes in Europe. The paper is organized as follows. The Results section presents our analysis findings on the evolutions of the atmospheric circulation, integrated water vapor transport, precipitation, Rossby wave excitation and propagation, and air temperature anomalies after the peak of NEP MHWs. We summarize our key findings and give relevant discussion in the Discussion section. Specific details of our data and methods are provided in the Methods section at the end.

Results

Evolution of SSTAs and atmospheric conditions related to the MHWs

Based on the 14 NEP MHW events peaking in early winter (see “Methods” for details), we first present their composite evolution of the SSTAs (Fig. 1). A widespread region with warmer-than-normal SSTAs is identified in the NEP, particularly within the study area (green box in Fig. 1). The increasing SSTAs up to the peak day maximum can be clearly seen (Fig. 1a–c). Although the SSTAs gradually decrease after the peak day, significant positive SSTAs persist (Fig. 1d–f). The composite evolution of surface heat flux anomalies highlights the potential interaction of MHWs with the local atmosphere aloft (Fig. 2). Before the peak day, the surface heat flux anomalies are positive, indicating that heat is being transferred from the atmosphere to the ocean. Thus, the warm SSTAs gradually develop. After the peak day, the surface heat flux anomalies become negative, indicating that the warm SSTAs feed back onto the atmosphere and heat is transferred from the ocean to the atmosphere. Decomposition of the surface heat flux anomalies shows that the transition of surface heat flux anomalies is primarily driven by the latent heat (LH), which exhibits distinct shifts after the peak day. The sensible heat flux anomalies also play a role in this transition. Although longwave radiation also shifts to negative anomalies after the peak, its contribution is much smaller compared to that of the LH flux anomalies. Similar results are presented in Fig. S1 using the NCEP/DOE dataset.

Further decomposition of the LH flux anomalies quantifies the contribution of wind speed, saturated specific humidity at the sea surface, specific humidity at 2 m above the sea surface, and the nonlinear effect (Supplementary Text S1 and Fig. S2). The contribution by saturated specific humidity anomalies is approximately constant over the composited 15-day period, serving as the primary contributor to the LH flux anomalies after the peak day, highlighting the direct role of MHWs in the LH flux anomalies. The variation of 2 m specific humidity anomaly is also crucial in shaping the LH flux anomalies. Prior to the peak day, the air mass is more humid, leading to positive LH flux anomalies. After the peak day, 2 m specific humidity anomalies become smaller, and the ocean experiences anomalous heat loss.

Composite surface heat flux anomalies (red line; positive downward; unit: W/m2) and their components, including LH anomalies (blue line), sensible heat anomalies (orange line), longwave radiation anomalies (green line), and shortwave radiation anomalies (purple line) based on ERA5 data, relative to the peak of NEP MHWs during early winter. Dots indicate statistically significant (p < 0.1) results based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Pink shading represents the period after the peak day.

As warm SSTAs are favorable for the anomalous heating of the atmosphere (Fig. 2)38,39, diabatic heating anomalies (“Methods”) become evident in the lower troposphere after the peak day. Based on the results derived from the JRA-55 data, positive diabatic heating anomalies at 925 hPa are observed near the MHW study area, which is located in the southern flank of the Aleutian low, with the maximum heating at a lag of 2 days relative to the peak day (Fig. 3). In addition, we also obtain the diabatic heating anomalies using NCEP/DOE and ERA5 datasets. The locations of positive anomalies over the study area are generally consistent among datasets, despite a more scattered distribution near the study area in ERA5 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4).

Composite diabatic heating (\({q}_{1}\); shading; unit: K/day) anomalies at 925 hPa based on JRA-55 dataset and sea level pressure (contour; unit: hPa) at a peak day, lags of b 1, c 2, d 3, e 4, f 5, g 6, and h 7 days. Stippling indicates statistically significant (p < 0.1) results based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. The green boxes indicate the MHW study area.

Diabatic heating can directly reverse lower-level circulation anomalies (Supplementary Fig. S5a–d; “Methods”), while transient eddy activity can also reverse upper-tropospheric anomalies (Supplementary Fig. S5i–l; “Methods”) due to enhanced atmospheric baroclinicity (Supplementary Fig. S5m–p; “Methods”)38,39. Thus, the high-pressure anomalies at 925 hPa before the peak day (Supplementary Fig. S6) begin to shift to low-pressure anomalies afterward (Fig. 4). The low-pressure anomalies gradually intensify from the 1 to 3 day-lag (Fig. 4b–d) and extend in spatial coverage over the following 4 to 7 days (Fig. 4e–h), with the center located over the Gulf of Alaska. In addition, the low-pressure system is present at both 300 hPa and 925 hPa, with a slight tilt of its central position with height, exhibiting a quasi-barotropic vertical structure. Due to the low-pressure anomalies to the north of the MHW area, westerly wind anomalies prevail in the study area at lags of 5–7 days, superimposed onto the climatological westerly winds. The increase in wind speed and humidity contrast enhances evaporation rates, weakening the SSTAs there (Supplementary Fig. S2)40.

a–h As in Fig. 3, but for geopotential height anomalies at 300 hPa (contour; unit: gpm) and at 925 hPa (shading; unit: gpm), respectively. Stippling indicates statistically significant (p < 0.1) geopotential height anomalies at 925 hPa based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Changes in water vapor transport and precipitation along the west coast of North America

As the pivotal media of atmospheric moisture, atmospheric rivers occur frequently in the NEP and make landfall along the west coast of North America (NA), especially during boreal winter41. We find that the integrated water vapor transport (IVT; blue contours in Fig. 5; “Methods”) after MHW peaks shows northeastward extension and enhanced intensity (Supplementary Fig. S7b–d), compared to the composite IVT of atmospheric rivers without the occurrence of MHWs (red contours in Fig. 5; “Methods”). Moreover, the specific humidity anomalies largely increase along the west coast of NA (Supplementary Fig. S8). Due to favorable moisture conditions and orographic uplift against the Pacific Coast Ranges42,43, enhanced precipitation anomalies emerge along the west coast of NA at 5 to 7-day lags (Fig. 5f–h and Supplementary Fig. S9f–h). Further exploration shows that in 11 out of 14 MHW events, atmospheric rivers appear and make landfall along the west coast of NA, accompanied by positive precipitation anomalies in this region (not shown).

a–h As in Fig. 3, but for composite precipitation anomalies (shading; unit: mm/day) and IVT (blue contour; unit: kg m–1s–1) after the MHW peaks, as well as IVT of atmospheric rivers without MHWs (red contour; unit: kg m–1s–1) derived from ERA5 data. Stippling indicates statistically significant (p < 0.1) precipitation anomalies based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Downstream influences on circulation and temperature anomalies over North Atlantic and Europe

Precipitation anomalies are closely linked to upper-tropospheric divergence and vorticity anomalies locally, which contribute to atmospheric Rossby wave formation44,45. Our results show that significant negative Rossby wave source (RWS; “Methods”) anomalies are identified over the west coast of NA at lags of 4–7 days (Fig. 6). Such negative RWS at 300 hPa can trigger atmospheric Rossby waves to propagate across the mountains and subsequently influence downstream regions (Fig. 7). Although there are other significant RWS regions, we do not explore them in detail considering their weaker intensity and smaller spatial coverage compared to those over coastal NA.

Composite meridional wind anomalies (shading; unit: m s–1), and WAF (vectors; unit: m2 s–2) at 300 hPa at lags of a 6, b 8, c 10, and d 12 days relative to the peak day. Stippling indicates statistically significant (p < 0.1) meridional wind anomalies based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. The magenta boxes indicate the MHW study area.

As one of the main mechanisms facilitating remote connection, the propagation of Rossby wave energy from the RWS region is well represented by the wave activity flux (WAF; “Methods”)45. As shown in Fig. 7, continuous Rossby wave energy, indicated by the WAF, can be transported across the NA continent and North Atlantic Ocean via westerly airflow, with a profound WAF reaching western Europe.

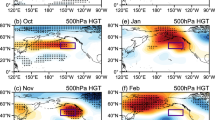

In order to reveal the downstream effects of the Rossby waves, associated with the NEP MHWs, we further show the composite evolutions of the 500 hPa circulation and 2 m temperature anomalies (Fig. 8). At the 10-day lag, a high-pressure anomaly develops in southern Europe (centered near 45°N, 5°E), resembling the ridge pattern identified by Sousa et al.46, while a low-pressure anomaly is present in the central North Atlantic (Fig. 8a). This dipole circulation pattern persists until a lag of 16 days, although the location and intensity of the two systems vary with time (Fig. 8d). During this period, the northern flank of the high-pressure anomaly experiences a significant increase in 2 m temperature, with the warming extending from western Europe to Russia (Fig. 8a–d). This increase may result from several factors: warm horizontal temperature advection brought by the anomalous southwesterly winds (Supplementary Fig. S10a–d), anomalous subsidence, and adiabatic compression associated with the high-pressure anomaly over southern Europe46. There may also be some damping effects caused by boundary layer turbulence. At a lag of 16 days, the low-pressure anomaly over the North Atlantic diminishes, while a low-pressure anomaly emerges over northern Europe (centered near 65°N, 40°E; Fig. 8d). Meanwhile, the high-pressure anomaly is maintained over southern Europe (centered near 45°N, 5°E). By lags of 18 days, the anomalous southwesterly winds over western Europe (centered near 50°N, 0°) shift to anomalous westerly winds, accompanied by weak warm advection (Supplementary Fig. S10e). The positive 2 m temperature anomaly persists but somewhat weakens (Fig. 8e). At a lag of 20 days, the high-pressure anomaly over southern Europe (centered near 40°N, 5°W) largely decays, accompanied by the weakening of the 2 m positive temperature anomaly (Fig. 8f).

Notably, significant temperature anomalies are also observed in North Africa, consistent with the relationship between upper-level ridge/trough patterns over southern Europe and near-surface temperature anomalies in North Africa in boreal winter47,48, which warrants further in-depth research.

Composite 2 m temperature anomalies (shading; unit: K) and geopotential height anomalies (contour; red for positive and blue for negative; unit: gpm) at 500 hPa at lags of a 10, b 12, c 14, d 16, e 18, and f 20 days relative to the peak day of NEP MHWs. Stippling indicates statistically significant (p < 0.1) 2 m temperature anomalies based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To further investigate the role of diabatic heating along the west coast of NA after the peak of MHWs in triggering the atmospheric Rossby waves and contributing to the downstream circulation and temperature anomalies, we employ a linear baroclinic model (LBM; “Methods”) to impose anomalous diabatic heating as determined from observations at a lag of 5 days when enhanced precipitation anomalies occur along the west coast of NA (Fig. 5f). The modeled response is consistent when the heat forcing at a lag of 6 days is imposed (not shown). The observed vertical profile exhibits prominent heating from 700 to 400 hPa at the 5-day lag (Fig. 9a), with the maximum heating anomaly of 1.16 K/day at 500 hPa. After reaching a quasi-equilibrium state, the model captures a high-pressure anomaly over western Europe and a low-pressure anomaly to its north (centered near 75°N, 0°; Fig. 9b). Since the LBM does not include nonlinear processes, there are certain discrepancies between the model results and the observations. There is a northeastward displacement of the high-pressure anomaly over Europe and a northwestward shift of the northern low-pressure anomaly compared to observations (Fig. 8d, e). In addition, the LBM does not capture the negative anomalies observed over eastern NA at lags of 16–18 days.

a Vertical profile of imposed anomalous diabatic heating (red line) in the LBM. b Geopotential height anomalies (contour; red for positive and blue for negative; values 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 21 plotted; unit: gpm) at 500 hPa averaged over days 16–18, as the quasi-equilibrium response to the heating. Shading indicates the imposed heating (shading; unit: K day–1) at 500 hPa.

Furthermore, we also use the same anomalous diabatic heating (Fig. 9a) to drive the Community Atmosphere Model 5.0 (CAM5; EXP_NEP_Q; “Methods”). Similar to the observational results (Fig. 8a–c), a zonal circulation pattern with positive-negative-positive anomalies appears over eastern NA, the North Atlantic, and western Europe in the 16-day mean modeled results, with a longer persistence for the high-pressure anomaly (Supplementary Fig. S11a–e). These anomalies shift eastward and exhibit larger magnitude compared to the observations (Fig. 10a vs Fig. 8a, b). Significant increases in 2 m temperature are also observed (Fig. 10b, Supplementary Fig. S11f–j), which exhibit a slight southward shift compared to the observations. Meanwhile, a negative temperature anomaly is found in western Europe near 50°N, 10°W, which is somewhat inconsistent with observations. To further evaluate the direct influences of early winter NEP MHWs on the downstream circulation and temperature, we also impose the observed SSTAs (Fig. 1c) over the NEP based on CAM5 (EXP_NEP_SST; “Methods”). Results of the EXP_NEP_SST show a high-pressure anomaly over the North Atlantic, a low-pressure anomaly to the north centered near 75°N, 10°W, and another high-pressure anomaly over Europe near 50°N, 30°E (Fig. 10c, Supplementary Fig. S12a–e). Compared to observations (Fig. 8d, e), the low-pressure anomaly is displaced northwestward, and the high-pressure anomaly over Europe shifts eastward. The positive 2 m temperature anomaly is primarily observed over Scandinavia and the Baltic region, with a northward shift and a smaller spatial extent relative to the observations (Fig. 10d vs Fig. 8). Such discrepancies in the 2 m temperature anomaly are likely caused by the eastward shift and weaker intensity of the modeled high-pressure anomaly over Europe. However, cold anomalies emerge over southwestern Europe and northern Africa, as opposed to the observations, which may be due to the limitations of the model and the complex drivers of the temperature anomalies in these regions. In addition, the modeled results appear to be more similar to observations when a higher model resolution is applied (not shown).

Ensemble-mean response of a geopotential height (shading; unit: gpm) at 500 hPa and b 2 m temperature (shading; unit: K) in EXP_NEP_Q relative to CTRL, averaged over days 5–20 after imposing the model forcing. c, d As in (a, b), but for EXP_NEP_SST averaged over days 12–27 (also see “Methods”). Stippling indicates statistically significant (p < 0.1) results based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Hence, both LBM and CAM5 have provided evidence of the impacts of NEP MHWs on circulation and temperature anomalies over Europe, although there are some differences among the modeled results. In addition, one potential explanation for the discrepancies simulated among the models is the coexistence of multiple downstream responses with distinct spatial patterns in the real world. Specifically, the meridional distribution of pressure systems over Europe (Fig. 8d, e) is primarily captured by the LBM and EXP_NEP_SST simulations, whereas the zonal distribution of pressure systems (Fig. 8b, c) is mainly reproduced by the EXP_NEP_Q simulation.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of northeast Pacific (NEP) marine heatwaves (MHWs) during early boreal winter on the downstream precipitation and temperature anomalies over North America (NA) and western Europe (Fig. 11). We found that a sign reversal of surface heat flux anomalies at the peak of MHWs corresponds to the oceanic feedback to the atmosphere during the MHW decay period, which is primarily attributed to the changes in latent heat flux. Then, the heat exchange due to MHWs influences the lower-level atmospheric circulation through diabatic heating (Supplementary Fig. S5a–d) and the upper-level atmospheric circulation through transient eddy forcing (Supplementary Fig. S5i–l)38,49. These processes lead to a circulation transition from high-pressure anomalies prior to the MHW peak to low-pressure anomalies after their peak. Vertically, the low-pressure systems to the north of the study area show a quasi-barotropic structure.

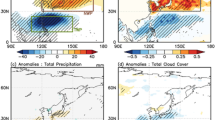

a, b Show composite geopotential height anomalies (shading; unit: gpm) and WAF (vectors; unit: m2 s–2) at 300 hPa at 5 and 14 days after the peak of MHWs, respectively. c Shows composite IVT (shading; unit: kg m-1s-1; blue shading) at a lag of 5 days and SSTAs (shading; unit: K; red shading) on the peak day of MHWs, while (d) illustrates the 2 m temperature anomalies (shading; unit: K) in western Europe at a lag of 14 days. Other symbols are indicated in the legend.

Based on composite evolutions associated with these MHWs, we found that the IVT after MHW peak day is stronger and located northeastward compared to composite IVT of atmospheric rivers without MHWs. Hence, increased precipitation is evident along the west coast of NA, especially at lags of 5–7 days, caused by moisture transport and orographic lifting against the Pacific Coast Ranges. Nevertheless, the causal link between NEP MHWs and NA coastal precipitation requires in-depth investigation through coupled models for more detailed diagnostics in the future.

The increased rainfall triggers atmospheric Rossby wave trains due to the related divergence and vorticity anomalies, which propagate eastward along the westerly jet, traverse the NA continent and North Atlantic Ocean, to eventually reach western Europe (Supplementary Fig. S13). At a 10-day lag relative to the MHW peak, a high-pressure anomaly emerges in southern Europe and the western Mediterranean, while a low-pressure anomaly with a northeast-southwest orientation develops in the central North Atlantic. These circulation anomalies jointly result in anomalous southwesterly winds into western Europe, leading to abnormal warm advection and the increase of the 2 m temperature there. Such anomalous circulation (particularly the high pressure anomaly) and temperature patterns persist for more than 10 days, which are in general captured by the LBM and CAM5 simulations despite some discrepancies with observations. Therefore, our study provides a potential pathway through which the NEP MHWs during early winter can presumably influence the air temperatures in Europe, which may be valuable for improving subseasonal-to-seasonal prediction models.

Although we emphasize the contribution of MHWs to the occurrence of the low-pressure anomaly over the NEP, which is crucial for the enhanced precipitation over the west coast of NA, other factors may also contribute. Moreover, we examine the top 5% of precipitation events along the NA west coast during early winter, which occur without the MHWs. Similar but stronger precipitation/RWS patterns are identified during the extreme precipitation events, but these events show weaker meridional winds and no clear wave train (Supplementary Fig. S14). Hence, their downstream circulation/temperature impacts (Supplementary Fig. S15) are substantially weaker than those during MHWs (Fig. 8). More detailed reasons to explain this discrepancy fall beyond the scope of this study, but will be investigated in future work. Nevertheless, these results suggest the important role of NEP MHWs in modulating downstream circulation and temperature anomalies over the North Atlantic and Europe.

This study focused on the role of early-winter teleconnections initially induced by NEP MHWs. However, due to the “mid-winter suppression” of the North Pacific storm track (i.e., weaker intensity in January-February)50, the impacts of mid-winter NEP MHWs on local and remote atmospheres remains unclear51,52. It would be worthwhile in the future to conduct more in-depth investigations on the downstream effects of NEP MHWs in mid-winter, and compare the similarities and differences of downstream effects between early winter and mid-winter MHWs.

In addition to the mid-latitude processes, tropical factors can also influence European climate. Previous studies have linked the Madden-Julian Oscillation to the Atlantic-European climate anomalies via Rossby wave trains originating from the extratropical North Pacific53,54,55,56, which have similar timescales and propagation pathways compared to our study. In addition, the signals in the North Atlantic-Europe region related to El Niño-Southern Oscillation differ between early winter and mid-winter57,58,59, suggesting the necessity of separating early winter and mid-winter characteristics as conducted in our study.

Methods

Data

For SST, we use the daily data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Optimum Interpolation (OI) SST v2.1 mapped onto a 0.25° × 0.25° grid60. For daily atmospheric variables, we use data from the fifth generation of European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecast (ERA5) reanalyses with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°61. We also use the National Centers for Environmental Prediction/Department of Energy (NCEP/DOE) Reanalysis II dataset62. Additionally, we use daily velocity potential, relative vorticity, convective heating rate, large scale condensation heating rate, longwave radiative heating rate, solar radiative heating rate, and vertical diffusion heating rate from the Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA-55) 6-hourly dataset with a 1.25° × 1.25° horizontal resolution63. This study analyzes data from 1981 to 2023. Daily anomalies from ERA5, NCEP/DOE, and JRA-55 are calculated as departures from the baseline climatology, where the baseline climatology is calculated as 30-year daily averages between 1981 and 2010. A three-day moving average has been applied to filter high-frequency fluctuations64,65.

Identification of NEP MHWs in early winter

MHWs in the NEP feature a large spatial scale. Previous studies used various regions to investigate NEP MHW events66,67. In this study, we select 160°W–135°W, 40°N–50°N as the study region for NEP MHWs, which can effectively capture the core location of anomalously warm SSTAs2,16. MHWs are identified when daily SST averaged in the study area (box in Fig. 1) exceeds the 90th percentile threshold of the seasonally varying baseline between 1983 and 2012, with a minimum duration of five consecutive days68. Note that the methods for screening MHWs may be different69,70, which does not affect our results robustly. The “peak day” is identified as the day when the maximum MHW intensity is detected, according to the Hobday et al.68 MHW definition—i.e., the maximum temperature departure from the baseline climatology during MHW detected conditions. Given the greater intensity of NEP MHWs occurring in early winter (November and December)2,16,19, and their significant ecological impacts71, this study primarily focuses on NEP MHWs peaking during the early winter period. Accordingly, 14 MHW events (Table 1) are selected for our composite analyses. The lead and lag analyses are all relative to the peak day of each MHW event.

Apparent heat source

To illustrate the anomalous diabatic heating patterns associated with the NEP MHWs, we calculate the atmospheric diabatic heating using JRA-55 data (Fig. 3). The diabatic heating rate is obtained by summing the large-scale condensation heating rate, convective heating rate, vertical diffusion heating rate, solar radiative heating rate, and longwave radiative heating rate72,73.

To verify the diabatic heating derived from JRA-55, we also compute the diabatic heating rate using the NCEP/DOE and ERA5 data (Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4). This calculation follows Eq. (1) 74:

where the static stability is expressed as \(\sigma =({RT}/{C}_{p}p)-(\partial T/\partial p)\), \(R\) is the specific gas constant, \(p\) is pressure, and \({C}_{p}\) is the specific heat capacity of air at constant pressure. T is the air temperature, and \(\omega\) is the vertical velocity in pressure coordinates. \(\vec{V}=\) (\(u,v\)) denotes the horizontal winds, and \({\nabla }_{H}\) is the horizontal gradient operator.

Geopotential tendency and Eady growth rate

To explain the transition from high-pressure to low-pressure anomalies after the peak day of MHWs, we calculated the geopotential tendency using the re-formulated quasi-geostrophic potential vorticity equation from Lau and Holopainen75:

where \({\sigma }_{1}\) is the atmospheric static stability parameter, \(\Delta\) denotes the anomaly, \(\varPhi\) is the geopotential, \(\alpha\) is the reciprocal of atmospheric density, \(T\) is air temperature, and \(f\) is the Coriolis parameter. \({Q}_{d}\), \({Q}_{{eddy}}\), and \({F}_{{eddy}}\) represent diabatic heating, transient eddy heating forcing, and transient eddy vorticity forcing, respectively. By applying the successive over-relaxation method to invert the three-dimensional operator \(\left(\frac{1}{f}{\nabla }^{2}+f\frac{\partial }{\partial p}\left(\frac{1}{{\sigma }_{1}}\frac{\partial }{\partial p}\right)\right)\)76, we can obtain the geopotential tendency induced by \({\Delta Q}_{d}\), \({\Delta Q}_{{eddy}}\), and \({\Delta F}_{{eddy}}\). \(\mathrm{Re}\) represents the residual including internal processes of the atmosphere. \({Q}_{d}\) can be calculated by Eq. (1), \({Q}_{{eddy}}\) and \({F}_{{eddy}}\) are calculated as follows:

where \(\vec{{V}_{h}}\) is the horizontal wind vector, \(\omega\) is vertical velocity in pressure coordinates, \(R\) is the dry gas constant, \({C}_{p}\) is atmospheric specific heat, \(\zeta\) is relative vorticity, and the prime symbol denotes the 2.5–8 days band-pass filtering.

The atmospheric baroclinicity is measured by the Eady growth rate, which can be calculated as follows77:

where \(g\) is gravitational acceleration, \(N\) denotes the Brunt-Väisälä frequency, and \(\theta\) is potential temperature.

Integrated water vapor transport

An atmospheric river is a long, narrow, and strong water vapor transport corridor78. Integrated water vapor transport (IVT) is often used to detect and track atmospheric rivers, although the specific methods may be diverse41,79. In this study, the vertical integral of the eastward and northward water vapor flux based on ERA5 is used to calculate the IVT (Eq. 6).

where \({{IVT}}_{u}\) and \({{IVT}}_{v}\) are the eastward and northward components, respectively. This is calculated as follows:

where \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration; q is the specific humidity; p and ps denote the top (1 hPa) and surface pressure levels, respectively; u and v represent zonal and meridional wind components, respectively. The hourly \({{IVT}}_{u}\) and \({{IVT}}_{v}\) data are obtained from ERA5 and averaged to get the daily results.

The edge of an atmospheric river is defined by a closed contour of IVT with a threshold of 250 kg m–1 s–1. The contour must have a length greater than 2000 km and a width narrower than 1000 km80,81. To analyze changes in IVT following the MHW peak day, we first identify all atmospheric river days over the region (30°N–50°N, 160°W–120°W) during early winter from 1982 to 2023. Then, we select the atmospheric river days associated with MHWs, which fall within the period from MHW peak day to 10-day lag. The remaining are considered as atmospheric river days without MHWs.

Wave activity flux

Atmospheric Rossby waves are typically stimulated by the release of condensation latent heat caused by strong convection or rainfall and divergence anomaly in the upper troposphere. The wave activity flux (WAF) is aligned with the direction of the local group velocity of the quasi-stationary Rossby wave in basic flows, acting as a useful tool for exploring the propagation pathways of Rossby waves82. Therefore, we employ the method from Takaya and Nakamura82 to calculate the horizontal WAF, aiming to illustrate the propagation of Rossby waves into downstream regions after the MHWs.

Here, W (unit: m2 s–2) denotes the horizontal WAF; P is pressure divided by 1000 hPa; U (= (U,V); unit: m s–1) is the climatological horizontal wind fields; \(\varphi\) and \(\lambda\) denote latitude and longitude, respectively; \(\psi\)(= \(\phi /f\)) is the stream function, where \(\phi\) is the geopotential and f \(=\) 2Ω sinφ is the Coriolis parameter; \({\psi }^{{\prime} }\) is the perturbation stream function relative to the 1981–2010 climatological baseline; \(a\) and \(\varOmega\) denote Earth’s radius and the rotation rate, respectively. We set \(a\) and \(\varOmega\) to 6.37 × 106 m and 7.292 × 10−5 rad/s, respectively.

Rossby wave source

To investigate the potential sources of Rossby waves, we calculate the Rossby wave source (RWS) using the following equation, which is based on the derivations by Sardeshmukh and Hoskins44 from the nonlinear vorticity equation:

where \({\nabla }_{H}\) is the horizontal gradient; \(V=\left(u,v\right)\) denotes the horizontal wind vector with u and v for zonal and meridional winds, respectively; subscript \(\chi\) indicates its divergent component; \(f\) represents the planetary vorticity (characterized by the Coriolis parameter), \(\zeta\) represents the relative vorticity, while \(f+\zeta\) represents the absolute vorticity. Primes indicate anomalies relative to the 1981–2010 climatological baseline.

Experimental setup of LBM

The linear baroclinic model (LBM) is a linear atmospheric model based on the hydrostatic primitive equations linearized about a basic state, with all nonlinear interactions between perturbations neglected. It is commonly employed to investigate linear atmospheric dynamics83. In this study, the dry version of the LBM is employed because it is suitable for assessing whether the imposed heating (as the forcing) drives the associated atmospheric circulation anomalies over the North Atlantic and Europe84. The imposed heating is based on the observed diabatic heating anomalies averaged over 42.5°N–60°N and 150°W–125°W at 5 days after the peak of the MHWs, covering the pressure levels from 1000 hPa to 10 hPa. The model configuration is T42L21, featuring a horizontal resolution of ~2.8° × 2.8° and 20 sigma layers vertically. This model is primarily constructed by linearizing the fundamental equations relative to the mean atmospheric state from November to December over the period 1981–2010 based on the NCEP/NCAR reanalysis data85. We use the default dissipation settings, as described by Watanabe and Jin86. The simulations obtain a quasi-equilibrium atmospheric state after 15 model days84. Output variables are averaged over days 16–18 of the simulations and represent the stable response to the specified heating.

Experimental setup of CAM5

The Community Atmospheric Model 5.0 (CAM5), developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), is used to evaluate the downstream effects of SSTAs or diabatic heating anomalies related to the NEP MHWs on circulation and 2 m air temperature. CAM5 has been widely employed previously to investigate atmospheric processes and mechanisms19,87. In this study, we conduct a control experiment (CTRL) and two sensitivity experiments (EXP_NEP_Q and EXP_NEP_SST). The simulations are undertaken with the f19_g16 configuration (i.e., ~2.5° ×1.9° atmospheric resolution). The model uses prescribed SST derived from version 2 of NOAA Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature60 and version 1 of Hadley Center Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature88. For reference, the model is forced by the atmospheric state in November 2002, with daily climatological SST in November averaged over 1981–2010 as the boundary condition. The reference simulation is initialized on November 1st and integrated for a period of 30 days. Each of the last 10 days is used as the atmospheric initial condition to generate the CTRL (same as the configuration of the reference simulation), EXP_NEP_Q, and EXP_NEP_SST members. Note that the atmospheric initial condition to generate ensemble members is not sensitive to specific model year, as the ensemble-mean results can exclude the atmospheric internal variability (not shown). In EXP_NEP_Q, we impose diabatic heating anomalies across all vertical levels, which are interpolated in the area (42.5°N–60°N, 150°W–125°W) based on those observed 5 days after the peak of MHWs. Within this area, the adiabatic heating intensity decreases linearly to zero from the center outward to the edge, with no transition zone outside this area. The SST boundary condition in EXP_NEP_Q is the same as that in the CTRL. For the EXP_NEP_SST experiment, we overlay the composite peak-day SSTAs of the NEP MHWs over (40°N–50°N, 160°W–135°W) onto the climatological SST without buffer zones, while the SSTs outside the NEP remain as climatological values. The CTRL and two sensitivity experiments are integrated for a period of 30 days. The initial 5 days are not used to eliminate the spin-up effects of the model81. Therefore, for the EXP_NEP_Q experiment, we averaged the results from days 5 to 20, while for the EXP_NEP_SST experiment, we averaged the results from days 12 to 27. Similar experimental set-ups have also been used to validate the atmospheric teleconnection relationships81,87,89,90. Future experiments may impose the observed time-varying diabatic heating anomalies to get more realistic results.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. The daily dataset of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) optimum interpolation sea surface temperature version 2.1 (OISST v2.1) is provided at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.oisst.v2.highres.html. The daily dataset of National Centers for Environmental Prediction/Department of Energy (NCEP/DOE) Reanalysis II is available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis2.html. The daily data of Japanese55-year Reanalysis are at https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/d628000/dataaccess/#. The daily data of the fifth generation of European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast (ERA5) are available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=download and https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=download. MHW statistics are computed using the Python module from https://github.com/ecjoliver/marineHeatWaves.

Code availability

The codes used to produce the results of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Bond, N. A., Cronin, M. F., Freeland, H. & Mantua, N. Causes and impacts of the 2014 warm anomaly in the NE Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 3414–3420 (2015).

Chen, Z., Shi, J. & Li, C. Two types of warm blobs in the Northeast Pacific and their potential effect on the El Niño. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 2810–2827 (2021a).

Cavole, L. M. et al. Biological impacts of the 2013–2015 warm-water anomaly in the Northeast Pacific: winners, losers, and the future. Oceanogr 29, 273–285 (2016).

Hartmann, D. L. Pacific sea surface temperature and the winter of 2014. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1894–1902 (2015).

Walsh, J. E. et al. The exceptionally warm winter of 2015/16 in Alaska. J. Clim. 30, 2069–2088 (2017).

Di Lorenzo, E. & Mantua, N. Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1042–1047 (2016).

Whitney, F. A. Anomalous winter winds decrease 2014 transition zone productivity in the NE Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 428–431 (2015).

Nielsen, J. M. et al. Responses of ichthyoplankton assemblages to the recent marine heatwave and previous climate fluctuations in several Northeast Pacific marine ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 506–520 (2021).

Piatt, J. F. et al. Extreme mortality and reproductive failure of common murres resulting from the northeast Pacific marine heatwave of 2014-2016. PLoS One 15, e0226087 (2020).

McCabe, R. M. et al. An unprecedented coastwide toxic algal bloom linked to anomalous ocean conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 10,366–10,376 (2016).

Free, C. M. et al. Impact of the 2014–2016 marine heatwave on US and Canada West Coast fisheries: Surprises and lessons from key case studies. Fish Fish 24, 652–674 (2023).

Amaya, D. J., Miller, A. J., Xie, S. P. & Kosaka, Y. Physical drivers of the summer 2019 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Commun. 11, 1903 (2020).

Kohlman, C. et al. The 2019 marine heatwave at Ocean Station Papa: A multi-disciplinary assessment of ocean conditions and impacts on marine ecosystems. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 129, e2023JC020167 (2024).

Holbrook, N. J. et al. Keeping pace with marine heatwaves. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 482–493 (2020).

Oliver, E. C. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–12 (2018).

Chen, Z., Shi, J., Liu, Q., Chen, H. & Li, C. A persistent and intense marine heatwave in the Northeast Pacific during 2019–2020. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093239 (2021b).

Chen, H. H. et al. Combined oceanic and atmospheric forcing of the 2013/14 marine heatwave in the northeast Pacific. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 3 (2023).

Holbrook, N. J. et al. A global assessment of marine heatwaves and their drivers. Nat. Commun. 10, 2624 (2019).

Shi, J. et al. Northeast Pacific warm blobs sustained via extratropical atmospheric teleconnections. Nat. Commun. 15, 2832 (2024).

Liang, Y. C. et al. Linking the tropical Northern Hemisphere pattern to the Pacific warm blob and Atlantic cold blob. J. Clim. 30, 9041–9057 (2017).

Hong, H. J. & Hsu, H. H. Remote tropical central Pacific influence on driving sea surface temperature variability in the Northeast Pacific. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 044005 (2023).

Zhao, Y. & Yu, J. Y. Two marine heatwave (MHW) variants under a basinwide MHW conditioning mode in the North Pacific and their Atlantic associations. J. Clim. 36, 8657–8674 (2023).

Wang, S. Y. et al. Probable causes of the abnormal ridge accompanying the 2013–2014 California drought: ENSO precursor and anthropogenic warming footprint. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3220–3226 (2014).

Song, S. Y. et al. Arctic warming contributes to increase in Northeast Pacific marine heatwave days over the past decades. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 25 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Different modulations of Arctic Oscillation on wintertime sea surface temperature anomalies in the Northeast Pacific. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 129, e2024JD041360 (2024).

Bonsall, C., Macklin, M. G., Anderson, D. E. & Payton, R. W. Climate change and the adoption of agriculture in north-west Europe. Eur. J. Archaeol. 5, 9–23 (2002).

Meerburg, B. G. & Kijlstra, A. Changing climate—changing pathogens: Toxoplasma gondii in North-Western Europe. Parasitol. Res. 105, 17–24 (2009).

Golombek, R., Kittelsen, S. A. & Haddeland, I. Climate change: impacts on electricity markets in Western Europe. Clim. Change 113, 357–370 (2012).

Charru, M., Seynave, I., Hervé, J. C., Bertrand, R. & Bontemps, J. D. Recent growth changes in Western European forests are driven by climate warming and structured across tree species climatic habitats. Ann. Sci. 74, 1–34 (2017).

Ljungqvist, F. C. et al. The significance of climate variability on early modern European grain prices. Cliometrica 16, 29–77 (2022).

Hurrell, J. W. Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Sci 269, 676–679 (1995).

Hanna, E., Hall, R. J. & Overland, J. E. Can Arctic warming influence UK extreme weather?. Weather 72, 346–352 (2017).

Otterman, J. et al. North-Atlantic surface winds examined as the source of winter warming in Europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 181–184 (2002).

Trigo, R. M., Trigo, I. F., DaCamara, C. C. & Osborn, T. J. Climate impact of the European winter blocking episodes from the NCEP/NCAR Reanalyses. Clim. Dyn. 23, 17–28 (2004).

Sillmann, J., Croci-Maspoli, M., Kallache, M. & Katz, R. W. Extreme cold winter temperatures in Europe under the influence of North Atlantic atmospheric blocking. J. Clim. 24, 5899–5913 (2011).

Vihma, T. et al. Effects of the tropospheric large-scale circulation on European winter temperatures during the period of amplified Arctic warming. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 509–523 (2020).

Trenberth, K. E. & Fasullo, J. T. An apparent hiatus in global warming?. Earth’s. Future 1, 19–32 (2013).

Tao, L., Fang, J., Yang, X. Q., Sun, X. & Cai, D. Midwinter reversal of the atmospheric anomalies caused by the North Pacific mode-related air-sea coupling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100307 (2022).

Tao, L. et al. Role of North Atlantic Tripole SST in Mid-Winter Reversal of NAO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103502 (2023).

Shinoda, T., Zamudio, L., Guo, Y., Metzger, E. J. & Fairall, C. W. Ocean variability and air-sea fluxes produced by atmospheric rivers. Sci. Rep. 9, 2152 (2019).

Guan, B. & Waliser, D. E. Detection of atmospheric rivers: Evaluation and application of an algorithm for global studies. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 12514–12535 (2015).

Houze, R. A. Jr Orographic effects on precipitating clouds. Rev. Geophys. 50, 1–47 (2012).

Rutz, J. J., Steenburgh, W. J. & Ralph, F. M. The inland penetration of atmospheric rivers over western North America: A Lagrangian analysis. Mon. Weather Rev. 143, 1924–1944 (2015).

Sardeshmukh, P. D. & Hoskins, B. J. The generation of global rotational flow by steady idealized tropical divergence. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 1228–1251 (1988).

Qin, J. & Robinson, W. A. On the Rossby wave source and the steady linear response to tropical forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 50, 1819–1823 (1993).

Sousa, P. M., Trigo, R. M., Barriopedro, D., Soares, P. M. & Santos, J. A. European temperature responses to blocking and ridge regional patterns. Clim. Dyn. 50, 457–477 (2018).

Ward, N. et al. Synoptic timescale linkage between midlatitude winter troughs Sahara temperature patterns and northern Congo rainfall: A building block of regional climate variability. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 3153–3173 (2021).

Ward, N., Fink, A. H., Keane, R. J. & Parker, D. J. Upper-level midlatitude troughs in boreal winter have an amplified low-latitude linkage over Africa. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 24, e1129 (2023).

Hu, X., Shi, J., Ma, X., Tang, Y. & Jing, Z. Oceanic feedback to the atmosphere for anomalous SST events peaking in early winter in the Northeast Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2025GL115562 (2025).

Nakamura, H. Midwinter suppression of baroclinic wave activity in the Pacific. J. Atmos. Sci. 49, 1629–1642 (1992).

Deng, Y. & Mak, M. An idealized model study relevant to the dynamics of the midwinter minimum of the Pacific storm track. J. Atmos. Sci. 62, 1209–1225 (2005).

Zhao, Y. & Liang, X. S. Causes and underlying dynamic processes of the mid-winter suppression in the North Pacific storm track. Sci. China. Earth Sci. 62, 872–890 (2019).

Renkl, C., Oliver, E. C. & Thompson, K. R. Downscaling the ocean response to the Madden–Julian Oscillation in the Northwest Atlantic and adjacent shelf seas. J. Clim. 62, 6719–6744 (2024).

Cassou, C. Intraseasonal interaction between the Madden–Julian Oscillation and the North Atlantic Oscillation. Nat 455, 523–527 (2008).

Lin, H., Brunet, G. & Derome, J. An observed connection between the North Atlantic Oscillation and the Madden–Julian Oscillation. J. Clim. 22, 364–380 (2009).

Wu, J. et al. MJO prediction skill, predictability, and teleconnection impacts in the Beijing Climate Center Atmospheric General Circulation Model. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 75, 78–90 (2016).

Brönnimann, S. Impact of El Niño–Southern Oscillation on European climate. Rev. Geophys. 45, RG3003 (2007).

Ayarzagüena, B., Ineson, S., Dunstone, N. J., Baldwin, M. P. & Scaife, A. A. Intraseasonal effects of El Niño–Southern Oscillation on North Atlantic climate. J. Clim. 31, 8861–8873 (2018).

King, M. P. et al. Importance of late fall ENSO teleconnection in the Euro-Atlantic sector. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 1337–1343 (2018).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the daily optimum interpolation sea surface temperature (DOISST) version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quart. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Kanamitsu, M. et al. NCEP–DOE AMIP-II reanalysis (R-2). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 83, 1631–1644 (2002).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 reanalysis: General specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 93, 5–48 (2015).

Mioduszewski, J. R., Rennermalm, A. K., Robinson, D. A. & Mote, T. L. Attribution of snowmelt onset in Northern Canada. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 9638–9653 (2014).

Kodera, K. Influence of stratospheric sudden warming on the equatorial troposphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L06704 (2006).

Oliver, E. C. et al. Marine heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 13, 313–342 (2021).

Shi, J. et al. Role of mixed layer depth in the location and development of the Northeast Pacific warm blobs. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098849 (2022).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Sun, D., Jing, Z., Li, F. & Wu, L. Characterizing global marine heatwaves under a spatio-temporal framework. Prog. Oceanogr. 211, 102947 (2023).

Zhang, X., Zheng, F., Zhu, J. & Chen, X. Observed frequent occurrences of marine heatwaves in most ocean regions during the last two decades. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 1579–1587 (2022).

Opar, A. Lost at sea: Starving birds in a warming world. Audubon Magazine March–April (2015).

Lachmy, O. & Kaspi, Y. The role of diabatic heating in Ferrel cell dynamics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090619 (2020).

Yang, Y., Yang, Y. & Cao, J. Seasonal variability of diabatic heating in the Southeast Asian low-latitude highlands. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 152, 1311–1323 (2023).

Yanai, M., Esbensen, S. & Chu, J. H. Determination of bulk properties of tropical cloud clusters from large-scale heat and moisture budgets. J. Atmos. Sci. 30, 611–627 (1973).

Lau, N. C. & Holopainen, E. O. Transient eddy forcing of the time-mean flow as identified by geopotential tendencies. J. Atmos. Sci. 41, 313–328 (1984).

Fang, J. & Yang, X. Q. Structure and dynamics of decadal anomalies in the wintertime midlatitude North Pacific ocean–atmosphere system. Clim. Dyn. 47, 1989–2007 (2016).

Zhang, L., Gan, B., Wu, L., Cai, W. & Ma, H. Seasonal dependence of coupling between storm tracks and sea surface temperature in the Southern Hemisphere midlatitudes: A statistical assessment. J. Clim. 31, 4055–4074 (2018).

Newell, R. E. et al. Tropospheric rivers?–A pilot study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 19, 2401–2404 (1992).

Ralph, F. M. et al. A scale to characterize the strength and impacts of atmospheric rivers. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 269–289 (2019).

Zhu, Y. & Newell, R. E. A proposed algorithm for moisture fluxes from atmospheric rivers. Mon. Weather Rev. 126, 725–735 (1998).

Ma, X., Jia, Y. & Han, Z. Impact of the Gulf Stream front on atmospheric rivers and Rossby wave train in the North Atlantic. Clim. Dyn. 62, 5827–5843 (2024).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Watanabe, M. & Kimoto, M. Atmosphere-ocean thermal coupling in the North Atlantic: A positive feedback. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 126, 3343–3369 (2000).

Lu, R. & Lin, Z. Role of subtropical precipitation anomalies in maintaining the summertime meridional teleconnection over the Western North Pacific and East Asia. J. Clim. 22, 2058–2072 (2009).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 437–472 (1996).

Watanabe, M. & Jin, F. F. A moist linear baroclinic model: Coupled dynamical–convective response to El Niño. J. Clim. 16, 1121–1139 (2003).

Song, Q., Wang, C., Yao, Y. & Fan, H. Unraveling the Indian monsoon’s role in fueling the unprecedented 2022 marine heatwave in the Western North Pacific. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 90 (2024).

Rayner, N. A. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, D14 (2003).

Deng, J., Xu, H., Shi, N., Zhang, L. & Ma, J. Impacts of northern Tibetan Plateau on East Asian summer rainfall via modulating midlatitude transient eddies. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 8667–8685 (2017).

Tang, S. et al. Linkages of unprecedented 2022 Yangtze River Valley heatwaves to Pakistan flood and triple-dip La Niña. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 44 (2023).

Acknowledgements

J.S. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42475058, 42230405, 42276006, and 42105040) and joint project of KLME and CIC-FEMD (KLME202403). N.J.H. is supported by the Australian Research Council Center of Excellence for the Weather of the 21st Century (CE230100012). We sincerely thank Teng Zhou, Tianqi Du, Xi Hu, Shanling Cheng, Qian Qiang, and Yichuan Lu for their valuable help in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. plotted the figures and wrote the manuscript. J.S. conceived the study and revised the manuscript. N.J.H. provided additional thoughts and helped revise the manuscript. J.C. and Z.L. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, J., Shi, J., Holbrook, N.J. et al. A pathway for Northeast Pacific marine heatwaves to influence temperatures in western Europe during early winter. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 363 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01240-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01240-4