Abstract

Warming and extreme precipitation events frequently occur in the Asian summer monsoon during autumn, and their causes are still unclear. In this study, we investigate variations in the monsoon and autumn precipitation over the Indochina Peninsula (ICP) using reanalysis data, observational datasets, and ensemble simulations from the CMIP6 Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP). The results show that from 2005 to 2023, a delayed retreat of the ICP monsoon led to increased autumn precipitation. Arctic sea ice loss associated with Arctic amplification is identified as one of the primary forcing factors. Reduced Arctic sea ice influences the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and the tripole sea surface temperature (SST) pattern, which in turn excite Rossby wave sources in the mid-latitude North Atlantic. The resulting wave train propagates from Western Europe to Asia, inducing an anomalous anticyclone extending from Asia to the Western Pacific and promoting a northward displacement of the South Asian High (SAH). This shift drives a northward movement of the East Asian Subtropical Jet (EASJ) and the Western Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH). The SAH “pumping” enhances mid-tropospheric latent heat release and surface warming, strengthening the land–sea thermal contrast, thereby intensifying the monsoon circulation and delaying its retreat. These circulation changes enhance moisture convergence, increasing autumn precipitation over the ICP, highlighting the critical role of Arctic sea ice loss in modulating regional monsoon dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Asian monsoon region accounts for approximately 20% of the global monsoon domain. This region is characterized by high population density, complex geographical features, and rich biodiversity. Monsoon-driven precipitation plays a crucial role in ensuring food and energy security, and the timing of monsoon onset and retreat significantly affects agricultural production1. The tropical monsoon systems in the southern part of the Asian monsoon region primarily include the South Asian summer monsoon, the Bay of Bengal summer monsoon, and the South China Sea summer monsoon. And the Bay of Bengal monsoon predominantly influences precipitation over the eastern Bay of Bengal and the ICP. Situated in the central tropical monsoon region, the ICP is a key factor in modulating the seasonal evolution of the Asian monsoon2,3,4. The ICP is characterized by complex topography, and the orientation of its mountain ranges regulates the path and intensity of monsoonal flows, thereby affecting the spatial and temporal distribution of precipitation5,6. During autumn, the ICP is relatively humid, with the highest precipitation occurring along the central coast of Vietnam. Orographic effects also enhance precipitation, as moist air advected toward the windward slopes is lifted and cooled, promoting further rainfall7.

The monsoon can be viewed as the atmospheric circulation’s response to the annual cycle of solar radiation. Driven by land–sea thermal contrasts, the onset or retreat of the monsoon marks the transition from the dry to the wet season or from the wet to the dry season, respectively8. Key seasonal milestones in monsoon evolution—such as onset, peak, and retreat—have attracted considerable attention in recent studies9,10,11. In recent years, with the intensification of global warming, both the timing and intensity of monsoon retreat have been significantly affected, leading to substantial changes in regional precipitation patterns and profound impacts on the livelihoods of billions of people12,13. The monsoon typically retreats first from the eastern Arabian Sea, southern East Asia, and northern China. This is followed by a gradual north-to-south withdrawal over the Indian subcontinent and the ICP, and a west-to-east retreat over the northwestern Pacific region14,15,16,17.

The retreat of the monsoon over the ICP typically occurs between September and October, during which the 850-hPa zonal wind shifts from westerly to easterly18. Following previous studies, the 850-hPa zonal wind is commonly used to derive the monsoon withdrawal index (MDI)19,20,21. Monsoon retreat marks a transitional phase between the end of one monsoon system and the onset of another, resulting in substantial changes to atmospheric circulation and rainfall patterns12,21. Therefore, understanding the circulation anomalies and external forcing factors that influence monsoon retreat is of critical importance. On interannual timescales, an early or delayed withdrawal of the Bay of Bengal summer monsoon is associated with positive or negative phases of the Indian Ocean Dipole, respectively21. Warming over Asian drylands tends to delay the withdrawal of the East Asian monsoon12. Additionally, the phase of the Madden–Julian Oscillation has been linked to the timing of South Asian monsoon retreat22. In terms of long-term trends, enhanced surface warming and intensified land–sea thermal contrast under global warming are also conducive to delayed monsoon retreat over the ICP region18.

In recent decades, under global warming, the Arctic sea ice loss and Arctic amplification have drawn attention for their effects on monsoon region precipitation. Thus, Arctic sea ice may be a potential predictor of monsoon precipitation23,24. Presently, studies mainly focus on sea ice’s impact on East and South Asian summer monsoon rainfall25,26,27. In reality, recent research shows that Arctic sea ice impacts South Asian summer monsoon precipitation on interannual and decadal scales. This occurs via the NAO, atmospheric wave trains, and the Walker circulation modulated by ENSO28,29. Also, Barents–Kara Sea ice can trigger atmospheric wave trains through ocean-atmosphere or ocean-land-atmosphere coupling, influencing Asian tropical monsoon region rainfall, including in the ICP30,31,32. Under future high-emission scenarios with intensified Arctic amplification, the Asian monsoon region’s annual precipitation will rise significantly33.

However, the link between Arctic sea ice and autumn precipitation in the Asian tropical monsoon region, as well as the underlying physical mechanisms, remains uncertain. This study aims to analyze the pathways and mechanisms by which sea ice affects autumn precipitation in the ICP and to explore the connections between sea ice and the Asian monsoon circulation system and monsoon retreat. To achieve this, the study first analyzes the relationship between sea ice and autumn ICP precipitation using observational and reanalysis data. It then analyses the responses of the autumn monsoon circulation system and ICP precipitation under future scenarios of reduced Arctic sea ice and intensified Arctic amplification by utilizing the ensemble member data from the PAMIP.

Results

The relationship between autumn precipitation characteristics and monsoon retreat in ICP

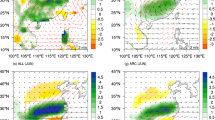

The study first evaluates the reliability of precipitation data and analyzes the characteristics of autumn precipitation in the ICP region and its relationship with monsoon retreat, using multiple-source precipitation reanalysis datasets. As shown in Fig. 1a, the ICP has a topographic elevation distribution with higher elevations in the north and lower ones in the south, and most areas are below 1500 m. The ICP also experiences significant monsoon influences34,35. The autumn precipitation distribution (Fig. 1b) indicates that the ICP’s average autumn precipitation, at over 110 mm per month, is higher than that of surrounding regions, with the highest precipitation occurring in areas like Vietnam on the ICP’s eastern side. Considering the topography and precipitation distribution, the red-boxed area in Fig. 1a, b (90–110°E, 10–28°N) is chosen as the key region for ICP autumn precipitation, and the region’s average precipitation is defined as the precipitation index (PI)36.

a Topography (shading, m). b Climatological autumn precipitation during 1980–2023 (shading, mm month−1). c Time series of the ICP precipitation index (PI; solid line, mm month−1) and its trend (dashed line) from different datasets. d Time series of the monsoon withdrawal index (MDI; cyan line, day), its trend (dashed line), and mean values (red and blue lines). The red box denotes the ICP region (90–110°E, 10–28°N).

Box-plot distributions of four precipitation datasets (Supplementary Fig. 1) show that ICP autumn precipitation is second-highest after summer, so the monsoon’s role in autumn precipitation during the monsoon retreat period remains significant15. ERA5, JRA55, and CRU precipitation data are more consistent and stable, which is also supported by Fig. 1c. Since the Asian tropical monsoon retreat experienced an inter-decadal delay of about 10 days before 2005, and monsoon precipitation over regions like India showed an increasing trend, a link between delayed monsoon retreat and more precipitation is suggested37,38. Thus, the study analyzed ICP precipitation and monsoon retreat relationships for the periods before and after 2005 (Fig. 1c, d). The Monsoon withdrawal index (MDI) was calculated from zonal wind differences between southern ICP (90–100°E, 10–15°N) and northern ICP (95–100°E, 25–30°N)20. The correlation coefficient between them is 0.42 (p < 0.01), with precipitation and monsoon retreat trends corresponding in the pre- and post-2005 periods, and the inter-decadal monsoon retreat delay being nearly 10 days38. Their significant relationship suggests that the mechanism by which monsoon retreat influences ICP autumn precipitation is crucial and warrants further investigation.

The relationship between Arctic sea ice and monsoon retreat and autumn precipitation in ICP

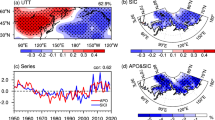

This section uses correlation and regression analysis to identify the temporal and spatial ranges of Arctic sea ice significantly related to ICP autumn precipitation and monsoon retreat, so as to determine the connections among these three factors. To exclude the influence of global warming, detrending of data and standardization of all indexes are conducted in the subsequent regression and correlation analysis39. It can be seen from the correlation coefficient distribution between PI and August sea ice concentration (SIC) (Fig. 2a) that SIC in the Arctic Ocean (85–90°N, 180–60°E) is significantly and negatively correlated with ICP autumn precipitation. Hence, the regional average of August SIC in the key area is used as the sea ice index (SICI). From the sliding correlation between SICI and PI calculated from multiple data sources (Fig. 2b), August Arctic sea ice is significantly and negatively correlated with autumn precipitation during 2005–2023 (Supplementary Fig. 2). In this period, the correlation coefficients between August SICI and autumn PI calculated from CPC, CRU, JRA55, and ERA5 data are −0.53, −0.72, −0.62, and −0.67, respectively, all exceeding the 95% confidence level of significance. As the ERA5 precipitation data is relatively accurate and the reanalysis data for subsequent circulation analysis is also from ERA5, the ERA5 precipitation data is used in the following.

a Regressions of August sea ice concentration anomalies against autumn PI during 2005–2023. b 11-year sliding correlation coefficients between SICI and PI, and between SICI and MDI. Regression of autumn precipitation anomalies (mm day−1) against c SICI (−1) and d MDI. The red and light blue boxes in a, c, d denote the key sea ice region and the ICP precipitation key region, respectively. Dotted areas (a, c, d) and circles (b) indicate values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level.

In addition to the significant correlation between SIC and precipitation during this period, a notable negative correlation also exists between SICI and MDI (Fig. 2b). Based on the regression of precipitation anomalies against SICI (−1) and MDI (Fig. 2c, d), reduced sea ice corresponds to significantly increased precipitation in the northwest and central-eastern ICP. A delayed monsoon retreat corresponds to significantly increased precipitation in the central-eastern ICP. Thus, Arctic sea ice in August is closely related to monsoon retreat and autumn precipitation. As prior studies indicate, monsoon retreat can directly impact monsoon-region precipitation16,40, and Arctic sea ice can influence such precipitation by exciting wave trains41,42,43,44. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate whether sea ice can modulate ICP precipitation by causing a delayed monsoon retreat. Although August SICI is strongly correlated with autumn PI, the correlation between autumn SICI and PI is not significant (see Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the sea ice influence on ICP precipitation is primarily linked to the state of the Arctic in August rather than in later autumn (Supplementary Fig. 3). Further research is also needed to clarify the relevant pathways and physical mechanisms.

Possible path of Arctic sea ice affecting autumn precipitation over ICP

In August, anomalously low temperatures are observed north of 80°N, while anomalously high temperatures prevail to the south, thereby enhancing the meridional temperature gradient near 80°N. This strengthened gradient favors the acceleration of the polar-front jet stream, leading to an intensified polar vortex and a circulation pattern resembling the positive phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) over the North Atlantic region (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Meanwhile, the reduction of Arctic sea ice in August decreases surface albedo, resulting in enhanced absorption of both shortwave and longwave radiation at the surface. According to the albedo feedback mechanism, this process is further amplified in autumn: reduced SIC enhances solar radiation absorption, which warms the troposphere and accelerates the subsequent SIC decline45,46. As a result, an unstable “cold-over-warm” stratification develops in the troposphere near 80°N, favoring enhanced upward motion (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d). In addition, correlation analysis shows that the direct relationship between autumn SICI and ICP precipitation is not significant, suggesting that it is primarily the August sea-ice melting, accompanied by the albedo feedback, that exerts a delayed influence on ICP autumn precipitation. The associated compensating subsidence intensifies over the mid-latitudes of the North Atlantic, thereby reinforcing the anomalous high-pressure system in that region (Supplementary Fig. 4f).

Entering autumn, the anomalous Arctic warming contributes to the filling of the polar low, weakening and displacing the polar vortex, and strengthening meridional circulation anomalies in the mid- to high latitudes47,48,49,50. Consequently, the initially NAO-like positive phase circulation weakens, manifesting as anomalous weak low pressure at high latitudes and pronounced anomalous high pressure over the mid-latitudes (Supplementary Fig. 5e, f).

The NAO-like phase also contributes to the concurrent formation of the North Atlantic tripole (NAT) in sea surface temperature (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The NAT, in turn, feeds back onto the atmosphere by enhancing anomalous subsidence over the mid-latitude North Atlantic51,52. Meanwhile, influenced by anomalous net surface heat fluxes, both the meridional temperature gradient and baroclinicity are strengthened in this region, favoring the excitation of Rossby wave sources (Supplementary Fig. 6b, c). According to the thermal wind relationship, the westerly jet to the south of the wave source is thereby intensified, steering the wave train southeastward (Supplementary Fig. 6d)53.

The wave train propagates southeastward from the North Atlantic, dispersing energy downstream (Fig. 3a). This creates a “+, −, +” anomalous geopotential height pattern over the North Atlantic–Western Europe–Asia region. The anomalous anticyclone over Asia shifts the South Asian High northward. This anticyclonic circulation induces strong upper-level divergence and intense low-level upward motion (Supplementary Fig. 7), favoring moisture condensation, latent heat release, and warming of the Asian troposphere54, thus strengthening the land–sea thermal contrast over Asia and the Indian Ocean (Fig. 3b).

a Regressions of 200 hPa wave activity flux (vectors, m2 s−2) and geopotential height (shading, gpm), and b 500–200 hPa temperature anomalies (°C) against SICI (−1). c Heatmap of correlation coefficients between SICI and NAT, u200pc1, SLC, SH_N, SH_wy, MDI, and PI. Regressions of d 200 hPa zonal wind anomalies (shading, m s−1), e 500 hPa, and f 850 hPa wind vectors (m s−1) and geopotential height (shading), and g vertically integrated water vapor flux (vectors, kg m−1 s−1) and its divergence (shading, kg m−1 s−1) against SICI (−1). The red solid lines in a and e denote the climatological SAH and WPSH, respectively. The dark blue box in a marks the Rossby wave source region, while the light blue box indicates the ICP precipitation key region. The dashed line in b shows the climatological temperature, and the two dark blue boxes in b indicate the regions used for SLC calculation. The symbols “***”, “**”, and “*” in c denote significance at the 99%, 95%, and 90% confidence levels (t-test), respectively. The black solid line in d indicates the climatological 200 hPa jet core (>20 m s−1). Black arrows in a, e, f, g denote vectors passing the 90% significance test. Dotted areas indicate values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level.

As the land–sea thermal contrast is closely tied to the monsoon circulation system55,56, this study defines several indices (see Methods): the WPSH ridge line latitude index and northern boundary latitude index to characterize the meridional position and northward expansion of the WPSH; the EASJ meridional position index for the jet stream’s meridional displacement; and the land–sea thermal contrast intensity index to measure the thermal difference between Asian land and the Indian Ocean. These indices help analyze their impact on the monsoon circulation system. In addition, the NAT index is the time coefficient of the second mode of the North Atlantic (80°W–0°, 20–70°N) SST Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF)57.

Both thermodynamic and dynamic processes contribute to the monsoon’s delayed retreat: the tropospheric warming enhances the land–sea thermal contrast, favoring a northward shift of the East Asian subtropical jet, while anomalous westerlies (north) and easterlies (south) around the anticyclone further displace the jet poleward14. Consequently, the WPSH and EASJ migrate northward, as confirmed by regression patterns of 200 hPa winds and 500 hPa circulation (Fig. 3c–e).

The correlation analysis (Fig. 3c) supports this linkage: sea ice reduction corresponds to enhanced land–sea contrast, northward displacement of WPSH/EASJ, delayed monsoon retreat, and increased ICP rainfall58,59,60. At low levels (850 hPa), strengthened westerlies over the Indian Ocean and South China Sea turn northeastward and form easterlies over the ICP, creating a cyclonic anomaly and local ascent (Fig. 3f). This circulation transports moisture from the Indian Ocean, South China Sea, and western Pacific into the ICP (Fig. 3g), intensifying precipitation.

To further validate these linkages, we compare the results with the MDI regression field (Supplementary Fig. 8). A delayed monsoon retreat corresponds to a northward shift of the westerly jet stream, an enhanced land–sea thermal contrast, and anomalous westerlies over the Indian Ocean–South China Sea, accompanied by anomalous cyclonic circulation over the ICP. These features promote moisture convergence and upward motion in the ICP. Consequently, reduced Arctic sea ice modulates the stretching of the polar vortex and excites Rossby waves through anomalous meridional circulation. This process strengthens the downstream Asian–Indian Ocean land–sea thermal contrast, thereby shifting the monsoon circulation system northward, intensifying the monsoon, delaying its retreat, and ultimately increasing ICP autumn precipitation.

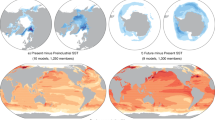

Arctic sea ice loss effects on autumn ICP precipitation under varying climates

In the preceding sections, we analyzed the pathways and physical processes through which Arctic sea ice influences autumn precipitation over the ICP on interannual timescales. Here, we further employ the PAMIP experiments to examine the mechanisms by which Arctic sea ice reduction affects ICP autumn precipitation. Specifically, three SST and SIC forcing experiments (Nos. 1–3 in Table 1), together with the derived ARC1 and ARC2 experiments (Table 1), are used to investigate whether the pathways and mechanisms through which Arctic sea ice loss enhances ICP autumn precipitation are consistent with those inferred from reanalysis, under different climatic backgrounds (modern relative to preindustrial, and future relative to modern)61. To reduce model biases and better characterize this mechanism, we adopt an observation-constrained approach (see Methods).

A comparison between ARC1 and ARC2 (Supplementary Figs. 9 and Fig. 4) shows that under reduced sea ice conditions, significant Arctic warming occurs in autumn. At 200 hPa, an anomalous high-pressure belt emerges to the north of the ICP, leading to a northward displacement of the SAH. Associated with this anomaly, the mid-northern sector of the EASJ is strengthened, resulting in an overall northward shift of the jet. Correspondingly, anomalous upper-level divergence sustains upward motion, which promotes water vapor condensation and latent heat release. This process warms the Asian upper troposphere, enhances the mid–upper tropospheric land–sea thermal contrast between Asia and the Indian Ocean, and thereby strengthens the monsoon forcing. At 500 hPa, an anomalous anticyclone over East Asia favors the westward extension and northward displacement of the WPSH. Meanwhile, under the influence of upper-level steering flow, anomalous westerlies over the Indian Ocean–South China Sea exhibit cyclonic turning over the ICP, which facilitates moisture convergence and ascent in the region, thereby enhancing precipitation.

a A 2-m temperature over the Arctic (shading, °C), b 200 hPa wind vectors (m s−1) and geopotential height (shading, gpm), c 200 hPa zonal wind (shading, m s−1), d 500–200 hPa mean temperature (shading, °C), e 500 hPa wind vectors (m s−1) and geopotential height (shading), and f precipitation (shading, mm day−1) and 850 hPa wind vectors (m s⁻¹) in response to Arctic sea ice loss (ARC2). The red solid lines in b, c, e denote the climatological SAH, EASJ, and WPSH, respectively. Black dots denote values statistically significant at the 90% confidence level.

The primary differences between ARC1 and ARC2 lie in the intensity of these anomalies: ARC2 exhibits stronger Arctic warming as well as more pronounced circulation and precipitation anomalies. This may be attributed to the pdSST-futArcSIC experiment in ARC2, which employs Arctic sea ice forcing derived from the RCP8.5 scenario, thus reflecting a more pronounced Arctic amplification under future conditions62. Overall, the PAMIP results corroborate the reanalysis findings. Furthermore, comparison of the wave train patterns reveals that both ARC1 and ARC2 exhibit a “+, −, +” teleconnection extending from the North Atlantic to Western Europe and Asia, consistent with reanalysis (Supplementary Fig. 10)63.

Discussion

Based on observations, diagnostic analyses, and the PAMIP multi-model ensemble simulations, this study investigates how Arctic sea ice forcing contributes to the delayed monsoon retreat over the ICP and the associated increase in autumn precipitation, with a focus on the underlying pathways and mechanisms. The results also suggest that future reductions in Arctic sea ice and intensified Arctic amplification may further enhance ICP autumn rainfall.

Since the early 21st century, the delayed monsoon retreat has contributed to increased local precipitation over the ICP. This delay is associated with an anomalous Asian anticyclone linked to the northward extension of the WPSH, which enhances moisture transport into the ICP.

To clarify the pathways through which sea ice forcing influences this process, we summarize the mechanism in Fig. 5. Through the albedo feedback mechanism, the decline in Arctic sea ice leads to a weakening of the polar vortex in autumn, accompanied by an enhancement of anomalous meridional circulation over the mid- to high-latitudes of the North Atlantic. The weakened polar vortex further suppresses a NAO-like positive phase pattern, thereby modulating the North Atlantic tripole sea surface temperature anomalies. Under the influence of air–sea interactions, a Rossby wave train is excited over the midlatitude North Atlantic and propagates southeastward, inducing an upper-tropospheric anticyclone around 200 hPa over Asia and the western Pacific.

This circulation change favors a northward displacement of the South Asian High (SAH) and the East Asian Subtropical Jet (EASJ), accompanied by anomalous low-level ascent. The resulting moisture convergence and latent heat release warm the Asian atmosphere, thereby strengthening the land–sea thermal contrast between Asia and the Indian Ocean, which intensifies the monsoon circulation and delays its retreat. Over the ICP and its southern regions, the combined effects of anomalous westerlies and anticyclonic flow guided by the subtropical high-pressure system trigger an anomalous cyclonic circulation, enhancing moisture transport and convergence, which ultimately amplifies precipitation in this region.

Recent studies suggest that Arctic sea ice affects monsoon precipitation both through land–atmosphere coupling over Asia and via remote teleconnections, such as the Atlantic–Pacific linkage27,29. This suggests that additional pathways may contribute to its impact on the Indian–Chinese monsoon (ICP) precipitation, but these mechanisms remain insufficiently understood. In particular, the interdecadal shift in their relationship around 2005 requires further investigation. Previous studies have indicated that Asian precipitation is not only modulated by oceanic interdecadal modes, such as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)64,65,66,67, but may also be affected by the intrinsic variability of sea ice68. Therefore, this will constitute a key direction for our future research.

Methods

Observational and reanalysis datasets

Precipitation data from JRA5569 and ERA570 reanalysis, as well as CPC71 and CRU72 observational datasets, are used in this study. Observations of SST and SIC are from the Hadley Center Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature data set (HadISST)73. ERA5 reanalysis is used for other circulation data. Autumn in this study refers to the three-month average of September, October, and November. The significance tests for correlation and regression used in this paper are based on t-tests.

Definitions of indices

In this study, the PI is defined as the area-averaged precipitation obtained by applying an ocean mask over the ICP region. The East Asian subtropical westerly jet meridional position index (u200pc1) in Fig. 4c is the principal component of the first EOF mode of the 200-hPa zonal wind over East Asia (Supplementary Figs. 11). Given the significance of upper-tropospheric land-sea thermal contrasts for monsoon circulation systems74,75, we define SLC as the difference in average temperature between 500 and 200 hPa over the Tibetan Plateau and its surroundings (55–85°E, 25–38°N) and the tropical Indian Ocean (55–85°E, 6°S–7°N)55. Following the National Climate Center (NCC) index definition: Western Pacific Subtropical High ridge line latitude (SH_wy) is the average latitude of the subtropical high center (where u = 0 and ∂u/∂y > 0 at 500 hPa) across longitudes 110°–150°E and latitudes 10°–60°N; Western Pacific Subtropical High northern boundary index (SH_N) is the average latitude of the 5880 gpm contour north of the subtropical high at 500 hPa across the same region.

PAMIP experiment in CMIP6

The PAMIP experiments employed in this study are atmosphere-only time-slice simulations, each spanning 14 months with 600 ensemble members, and prescribing the seasonal cycle of monthly mean SST and SIC. The first two months of each simulation are discarded as spin-up, and the remaining 12 months are used for analysis. All three experiments are forced with present-day SST, while SIC is prescribed according to preindustrial (pi), present-day (pd), and future (fut) Arctic sea ice distributions (Nos. 1–3 in Table 1). Specifically, piArcSIC is derived from the multi-model mean of 31 CMIP5 historical simulations, with the 1979–2008 global warming signal removed; pdSIC is based on the climatology of Hadley observational data for 1979–2008; and futArcSIC is derived from the multi-model mean of 31 CMIP5 RCP8.5 simulations, constrained by a +2 °C global-mean temperature increase relative to preindustrial levels61.

ARC1 and ARC2 are designed to investigate the climate responses to Arctic sea ice loss from preindustrial to present, and from present to future, respectively. After applying observational constraints to ARC1 and ARC2, ensemble means are calculated. Statistical significance is assessed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To further investigate the mechanism by which Arctic sea ice reduction influences ICP autumn precipitation, we first evaluated the performance of all 600 ensemble members in simulating the ICP precipitation response to SIC anomalies. Reanalysis results indicate that Arctic sea ice loss substantially enhances ICP autumn precipitation. Based on this, we selected the top 100 members from ARC1 and ARC2 that are capable of reproducing positive ICP precipitation anomalies, and used their ensemble mean to assess whether the modulation mechanisms of ICP precipitation increase under different sea ice reduction backgrounds are consistent with those derived from reanalysis. The incorporation of observational constraints effectively improves the robustness of the analysis and provides valuable insights into the pathways and physical mechanisms through which Arctic sea ice affects ICP autumn precipitation76.

Rossby wave source

According to the study of Sardeshmukh and Hoskins53, the vorticity source generated by the steady divergence site in the upper troposphere can be expressed as

Here, \(\bar{\zeta }\) and \({\zeta }^{{\prime} }\) denote the autumn climatological mean and anomalous relative vorticity, \({\bar{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}_{\chi }\) and \({{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\chi }^{{\prime} }\) represent the autumn climatological mean and anomalous divergent wind, f is the geostrophic vorticity, and \({\nabla }_{H}\) is the two-dimensional divergence. We focus solely on the quasi-steady divergent field’s forcing of stationary waves. Given that large-scale divergent wind fields in the atmosphere are primarily linked to nonuniform diabatic heating and major topography, S can signify the quasi-steady external forcing influencing atmospheric stationary planetary waves. Thus, analyzing the distribution of S aids in comprehending the source and mechanism of atmospheric stationary planetary wave generation.

Wave activity flux

The WAF derived by Takaya and Nakamura is used to measure the wave propagation77. Its horizontal components in pressure coordinates are obtained as follows:

The quantity \({|U|}\) denotes the autumn climatological mean magnitude of the wind. U and V represent the zonal and meridional wind, respectively. \(\psi\) is the stream function, and p is the normalized pressure (pressure/1000 hPa). a, λ, and φ represent the radius of the Earth, longitude, and latitude, respectively. A superscript with a prime characterizes the variable’s anomaly.

Data availability

The ERA5 data are downloaded from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels-monthly-means?tab=overview. The CRU data are available at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/. The CPC data are available at https://www.psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globalprecip.html. The JRA55 data are available at https://jra.kishou.go.jp/JRA-55/index_en.html. The PAMIP data are available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search.

References

Mathison, C. et al. Estimating sowing and harvest dates based on the Asian summer monsoon. Earth Syst. Dyn. 9, 563–592 (2018).

Wang, Z. & Chang, C. P. A numerical study of the interaction between the large-scale monsoon circulation and orographic precipitation over south and southeast Asia. J. Clim. 25, 2440–2455 (2012).

Qi, L. & Wang, Y. Q. The effect of mesoscale mountain over the East Indochina Peninsula on downstream summer rainfall over East Asia. J. Clim. 25, 4495–4510 (2012).

Shi, Z., Sha, Y. & Liu, X. Effect of Yunnan–Guizhou topography at the southeastern Tibetan Plateau on the Indian monsoon. J. Clim. 30, 1259–1272 (2017).

Wu, C. H., Hsu, H. H. & Chou, M. D. Effect of the Arakan Mountains in the northwestern Indochina Peninsula on the late May Asian monsoon transition. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 10769–10779 (2014).

Wu, C. H. & Hsu, H. H. Role of the Indochina Peninsula narrow mountains in modulating the East Asian–western North Pacific summer monsoon. J. Clim. 29, 4445–4459 (2016).

Nguyen-Le, D., Ngo-Duc, T. & Matsumoto, J. The teleconnection of the two types of ENSO and Indian Ocean Dipole on Southeast Asian autumn rainfall anomalies. Clim. Dyn. 62, 1–23 (2024).

Webster, P. J. et al. Monsoons: processes, predictability, and the prospects for prediction. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103, 14451–14510 (1998).

Bombardi, R. J., Kinter, J. L. & Frauenfeld, O. W. A global gridded dataset of the characteristics of the rainy and dry seasons. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 1315–1328 (2019).

Wang, B. & Ho, L. Rainy season of the Asian–pacific summer monsoon. J. Clim. 15, 386–398 (2002).

Zeng, X. & Lu, E. Globally unified monsoon onset and retreat indexes. J. Clim. 17, 2241–2248 (2004).

Zhang, J. et al. Warming Asian drylands inducing the delayed retreat of East Asian summer monsoon and intensifying autumn precipitation in northern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2024JD041811 (2024).

Green, A. C. et al. Precipitation extremes in 2024. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 6, 243–245 (2025).

Chen, L., Chen, W., Hu, P., Chen, S. & An, X. Climatological characteristics of the East Asian summer monsoon retreat based on observational analysis. Clim. Dyn. 60, 3023–3037 (2023).

Hu, P., Chen, W., Huang, R. & Nath, D. Climatological characteristics of the synoptic changes accompanying South China Sea summer monsoon withdrawal. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 596–612 (2019).

Li, Q. et al. The relationship between the Bay of Bengal summer monsoon retreat and early summer rainfall in East Asia. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1355536 (2024).

Luo, M. & Lin, L. Objective determination of the onset and withdrawal of the South China Sea summer monsoon: objective determination of monsoon onset and withdrawal. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 18, 276–282 (2017).

Liu, Y., Cook, K. H. & Vizy, E. K. Delayed retreat of the summer monsoon over the Indochina Peninsula linked to surface warming trends. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 1927–1938 (2021).

Wang, B., Wu, R. & Lau, K. M. Interannual variability of the Asian summer monsoon: contrasts between the Indian and the western North Pacific–East Asian monsoons. J. Clim. 14, 4073–4090 (2001).

Oo, K. T. Climatology definition of the Myanmar southwest monsoon (MSwM): change point index (CPI). Adv. Meteorol. 2023, 2346975 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Retreat of the Bay of Bengal summer monsoon. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD039890 (2024).

Singh, M. & Bhatla, R. Role of Madden–Julian Oscillation in modulating monsoon retreat. Pure Appl. Geophys. 175, 2341–2350 (2018).

Coumou, D., Di Capua, G., Vavrus, S., Wang, L. & Wang, S. The influence of Arctic amplification on mid-latitude summer circulation. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–12 (2018).

Streffing, J., Semmler, T., Zampieri, L. & Jung, T. Response of Northern Hemisphere weather and climate to Arctic sea ice decline: resolution independence in Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) simulations. J. Clim. 34, 8445–8457 (2021).

Zhao, P., Zhang, X., Zhou, X., Ikeda, M. & Yin, Y. The sea ice extent anomaly in the North Pacific and its impact on the East Asian summer monsoon rainfall. J. Clim. 17, 3434–3447 (2004).

Zhang, P., Wu, Z. & Jin, R. How can the winter North Atlantic Oscillation influence the early summer precipitation in Northeast Asia: effect of the Arctic sea ice. Clim. Dyn. 56, 1989–2005 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Role of autumn Arctic Sea ice in the subsequent summer precipitation variability over East Asia. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 706–722 (2020).

Kulkarni, S. & Agarwal, A. Quantifying the association between Arctic Sea ice extent and Indian precipitation. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 470–484 (2024).

Kulkarni, S. & Agarwal, A. Arctic sea ice variability and its multiscale association with Indian summer monsoon rainfall at different time scales. J. Hydrol 653, 132729 (2025).

Prabhu, A., Mahajan, P. N. & Khaladkar, R. M. Association of the Indian summer monsoon rainfall variability with the geophysical parameters over the Arctic region. Int. J. Climatol. 32, 2042–2050 (2012).

Chatterjee, S. et al. A possible relation between Arctic sea ice and late season Indian summer monsoon rainfall extremes. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 1–7 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Connection between Barents Sea Ice in May and Early Summer Monsoon Rainfall in the South China Sea and its possible mechanism. Atmosphere 15, 433 (2024).

England, M. R. et al. Tropical climate responses to projected Arctic and Antarctic sea-ice loss. Nat. Geosci. 13, 275–281 (2020).

Takahashi, H. G. & Yasunari, T. A climatological monsoon break in rainfall over Indochina—a singularity in the seasonal march of the Asian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 19, 1545–1556 (2006).

Ge, F. et al. Interannual variability of summer monsoon precipitation over the Indochina Peninsula in association with ENSO. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 128, 523–531 (2017).

Li, G. et al. Inter-annual variability of spring precipitation over the Indo-China Peninsula and its asymmetric relationship with El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 56, 2651–2665 (2021).

Jin, Q. & Wang, C. A revival of Indian summer monsoon rainfall since 2002. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 587–594 (2017).

Wang, X. & Zhou, W. Interdecadal variation of the monsoon trough and its relationship with tropical cyclone genesis over the South China Sea and Philippine Sea around the mid-2000s. Clim. Dyn. 62, 3743–3762 (2024).

Chen, P. et al. Possible impacts of December Laptev sea ice on Indian Ocean Dipole conditions during spring. J. Clim. 34, 6927–6943 (2021).

Qin, L., Huang, F. & Xu, S. Precipitation distribution of the extended global spring—autumn monsoon and its possible formation mechanism. J. Ocean. Univ. China 02, 1027–1036 (2021).

Wu, B. et al. Has Arctic sea ice loss affected summer precipitation in North China?. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 4835–4848 (2023).

Gao, Y. et al. Arctic sea ice and Eurasian climate: a review. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 32, 92–114 (2015).

Yuan, D. & Lu, E. Influence of early spring Arctic sea ice on midsummer precipitation in Northeast China: the intermediate links and temporal-spatial channels. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD040640 (2024).

Narayanasetti, S. et al. Arctic sea-ice decline causes intense summer monsoon precipitation events over South Asia under greenhouse warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 054073 (2025).

Park, S., Bretherton, C. S. & Rasch, P. J. Integrating cloud processes in the community atmosphere model, version 5. J. Clim. 27, 6821–6856 (2014).

Chen, C., Zeng, G. & Datti, A. D. Impact of sea ice over the Greenland Sea on the Indian Ocean dipole mode during boreal autumn. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL114000 (2025).

Nakamura, T. et al. A negative phase shift of the winter AO/NAO due to the recent Arctic sea-ice reduction in late autumn. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 3209–3227 (2015).

Zou, C. et al. Contrasting physical mechanisms linking stratospheric polar vortex stretching events to cold Eurasia between autumn and late winter. Clim. Dyn. 62, 2399–2417 (2024).

Zou, C. & Zhang, R. Arctic sea ice loss modulates the surface impact of autumn stratospheric polar vortex stretching events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107221 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Connecting Tibetan Plateau snow change with Arctic sea-ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2025GL116351 (2025).

Watanabe, M. & Kimoto, M. Atmosphere-ocean thermal coupling in the North Atlantic: a positive feedback. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 126, 3343–3369 (2000).

Zheng, F., Li, J. P., Li, Y. J., Zhao, S. & Deng, D. F. Influence of the summer NAO on the spring-NAO-based predictability of the East asian summer monsoon. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 55, 1459–1476 (2016).

Sardeshmukh, P. D. & Hoskins, B. J. The generation of global rotational flow by steady idealized tropical divergence. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 1228–1251 (1988).

Wang, L. et al. Establishment of the South Asian high over the Indo-China Peninsula during late spring to summer. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 34, 169–180 (2017).

Li, Z. Q. & Xiao, Z. N. Thermal contrast between the Tibetan Plateau and tropical Indian Ocean and its relationship to the South Asian summer monsoon. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 14, 100002 (2021).

Luo, X. Q. et al. Relationship between the Tibetan Plateau-tropical Indian Ocean thermal contrast and the South Asian summer monsoon. Front. Earth Sci. 15, 151–166 (2021).

Czaja, A. & Frankignoul, C. Influence of the North Atlantic SST on the atmospheric circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 2969–2972 (1999).

Liang, S., Ding, Y., Duan, L., Hao, L. & Li, M. A study on the phenomenon of midsummer precipitation until delays early autumn and associated reasons in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei during 1970–2015. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 43, 655–675 (2019).

Yu, W. et al. Impact of North Atlantic SST and Tibetan Plateau forcing on seasonal transition of springtime South Asian monsoon circulation. Clim. Dyn. 56, 559–579 (2021).

Hu, D., Duan, A. M. & Zhang, P. Association between regional summer monsoon onset in South Asia and Tibetan Plateau thermal forcing. Clim. Dyn. 59, 1115–1132 (2022).

Smith, D. M. et al. The Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) contribution to CMIP6: investigating the causes and consequences of polar amplification. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1139–1164 (2019).

Koenigk, T. et al. Arctic climate change in 21st-century CMIP5 simulations with EC-Earth. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2719–2743 (2013).

Li, Q. Q. et al. Winter extreme precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau influenced by Arctic sea ice on interdecadal timescale. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 15, 42–51 (2024).

Wen, D., Yang, Y. & Cao, J. Interdecadal variation of early-spring rainfall over the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD033058 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Sun, X. & Yang, X. Q. Understanding the interdecadal variability of East Asian summer monsoon precipitation: joint influence of three oceanic signals. J. Clim. 31, 5485–5506 (2018).

Deng, M. et al. Profound interdecadal variability of summer precipitation over the upper Yangtze River Basin. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 25, e1258 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Distinct modulations of northwest Pacific tropical-cyclone precipitation by the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107749 (2024).

Fan, K. et al. Frequency of spring dust weather in North China linked to sea ice variability in the Barents Sea. Clim. Dyn. 51, 4439–4450 (2018).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 reanalysis: general specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 93, 5–48 (2015).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Xie, P. et al. A gauge-based analysis of daily precipitation over East Asia. J. Hydrometeorol. 8, 607–626 (2007).

Harris, I. et al. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 7, 109 (2020).

Rayner, N. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Sun, Y., Ding, Y. H. & Dai, A. G. Changing links between South Asian summer monsoon circulation and tropospheric land-sea thermal contrasts under a warming scenario. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 195–205 (2010).

Dai, A. G. et al. The relative roles of upper and lower tropospheric thermal contrasts and tropical influences in driving Asian summer monsoons. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 7024–7045 (2013).

Zhang, X. et al. The role of Arctic sea ice loss in the interdecadal trends of the East Asian summer monsoon in a warming climate. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 174 (2024).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFF0801704), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42475028), and the Supercomputing Center of Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology for providing computational resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D. conceived and wrote the study, with help from J.Z., who contributed to designing it and interpreting the physical process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duo, Y., Zhang, J. Arctic ice loss is delaying monsoon retreat over the Indochina Peninsula. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 364 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01241-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01241-3