Abstract

Global warming is expected to substantially weaken the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). However, climate models disagree greatly on the magnitude of AMOC weakening. This adds uncertainties in climate change projections, across the globe, through influencing poleward ocean and atmospheric energy transports. Here, we show through multi-model analysis of future climate change projections that AMOC weakening during this century will strongly influence precipitation and its extremes over Brazil. Such weakening dominates over the direct global warming impacts, causing drying in the Amazon, while completely mitigating them in northeast Brazil. We trace this to a tropical Atlantic warming, consistent with weakened heat transport along the southern branch of the South Equatorial Current. This induces a cross-equatorial sea surface temperature gradient and changes in latent heat flux, shifting the intertropical convergence zone southward. Our findings highlight the need to reduce uncertainties in the AMOC response to global warming and its oceanic mediated influences on Brazilian climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a key part of the climate system, transporting ocean heat poleward1, influencing ocean heat sequestration2,3 the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)4 and regional extreme weather events5. Some studies show that AMOC has weakened over the last century6,7,8,9 while others find no discernible change10,11 Long-term in-situ AMOC observations from the RAPID array at 26° N and the AMOC arrays at 22.5° S and 34.5° S provide critical benchmarks for evaluating recent changes, with the North Atlantic record already indicating a significant decline, while no robust trend has yet emerged in the South Atlantic12,13 An abrupt decline of AMOC will have global climate consequences14,15,16 with considerable changes in precipitation across the tropics17 A collapse of the AMOC could even counteract the drying impacts of global warming in regions of northern South America18 In fact, an AMOC collapse could cause drier conditions in northern South America, while increased rainfall in eastern Amazon and northeastern Brazil18. The impacts of drier conditions can be further exacerbated by deforestation and wildfires19.

The influence of AMOC on tropical precipitation has been mostly discussed via compensating poleward atmospheric heat transport, with the position of the ITCZ reflecting a coupled ocean–atmosphere adjustment to interhemispheric disturbances in energy20. Moreover, the northward heat transport by the AMOC establishes a persistent cross-equatorial thermal asymmetry, which directly influences low-level atmospheric boundary layer and conditions necessary for atmospheric convection21. Although both interhemispheric energy transport by the atmosphere and ocean contribute to ITCZ displacement, it is the oceanic transport that initiates the imbalance through the Atlantic Ocean, underscoring the primary role of AMOC-driven ocean dynamics in shaping tropical precipitation distribution.

The AMOC is a particularly important regulator of tropical Atlantic climate and may influence climate extremes over eastern Brazil. Consisting mainly of water from the Drake Passage and the Agulhas Current22,23, the upper branch of the AMOC forms the southern part of the South Equatorial Current (SEC)24. This southeast-northwest flow transports heat to the southwestern Atlantic warm pool (SAWP), a region with SST higher than 28.5 °C and enhanced low-level water vapor convergence, both conducive to heavy precipitation in the Eastern Northeast Brazil (ENEB) region. Furthermore, latent heat flux variations over the southwest Atlantic25 can increase atmospheric moisture content during the ENEB rainy season, which extends from austral autumn to the end of winter26. In addition, when Easterly Waves interact with local circulations, they can cause increased moisture convergence and heavy precipitation over the ENEB27,28,29,30, and this can result in flash floods and landslides29,31 The ENEB’s vulnerability to extreme climate events arises from densely populated, high-risk areas, where structural inequality, poverty, and the lack of effective public policy responses amplify the impacts32,33.

Here, we investigate the impact of future projected changes in AMOC on the tropical Atlantic SST and on mean and extreme precipitation over Brazil, including the ENEB, which is a vulnerable area to global warming. We use data from a multi-model ensemble (MME) of 29 models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6)34 under the historical and Shared Socio-economic Pathway 5–8.5 (SSP5–8.5) simulations. We define future changes as the average of the period 2050–2100 relative to 1950–2000. The MME projects a wide range of changes in the AMOC, tropical Atlantic climate, and ENEB precipitation extremes. Taking advantage of these models spread, we perform an intermodel analysis and identify a robust relation between weakening AMOC and precipitation (mean and extremes) over Brazil (see “Methods”).

Results

AMOC changes in the Southern and Northern Hemisphere

The MME projects a weakening of the AMOC at 20°S by 2050–2100 under SSP5-8.5 with an average decrease of 4 Sv, with some models indicating as much as a ~8 Sv decrease or 41% weakening (Table. S2). The AMOC weakens even more strongly in the North Atlantic, decreasing at 30°N by 7 Sv on average and up to 12 Sv in some models, the latter corresponding to a ~60% weakening (Table. S2), corroborating other studies35. The weakening is strongest in models with stronger mean AMOC. There is, however, little relation between AMOC weakening and the magnitude of global warming. This is unexpected because global warming influences the AMOC through changes in the upper ocean stratification, but also conversely, AMOC may influence global mean surface temperature (GMST) through regulating North Atlantic surface temperature, and heat and carbon fluxes36,37,38. The weak inter-model correlation between GMST and AMOC weakening may reflect errors in representing these two mechanisms and is partly influenced by outlier models, which exhibit little to no AMOC weakening under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. This analysis is consistent with earlier model intercomparison studies that have shown that AMOC will weaken with global warming and emphasised large model uncertainty39,40,41,42.

Linear regression analysis shows a tight relation between AMOC weakening in the South and North Atlantic, explaining 92% of the variance, with stronger weakening in the north (Fig. S1). AMOC weakening is more pronounced in the North Atlantic because it is closer to deep water formation regions that are highly sensitive to freshwater input and surface warming, which reduce surface water density and disrupt the sinking process. To reduce the influence of different climate model sensitivity, we normalize the AMOC changes by dividing them by the global mean temperature of each model; nevertheless, the regression remains equally strong (R2 = 0.92) without normalising (Fig. S1b). The greater AMOC weakening in the North Atlantic (~20% greater than the South Atlantic) suggests a buildup of mass and implies accumulation of ocean heat content in the tropical Atlantic. In the following analysis, we use the AMOC index at 20°S, as it is closer to our region of interest, while being highly correlated with AMOC changes in the north.

Response of tropical Atlantic SST and ENEB precipitation to AMOC weakening

We now assess the response of tropical Atlantic SST and precipitation to a weakened AMOC through regression analysis of the CMIP6 MME. As for the ΔAMOC index, ΔSST, and ΔPR are normalized by each model’s global warming (ΔGSAT) to minimize confounding influences (See Methods).

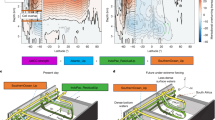

The map of regression coefficients with ΔAMOC at 20°S as the predictor and ΔSST as a response variable shows statistically significant negative values (p value < 0.05) over the equatorial and South Atlantic (Fig. 1a). These negative values indicate that the projected slow-down of the AMOC at 20°S can induce an increase in SST. A warming of the tropical Atlantic is consistent with heat convergence from the weakening of the northward heat transport in the Atlantic, as implied by the stronger AMOC weakening at 30°N compared to 20°S (Fig. S1). The correlation between the ΔAMOC and ΔSST among the models in the tropical Atlantic is large and statistically significant (p < 0.05), with R2 of 0.4 over all the SAWP (0° to 15°S and 34°W to 20°W). This indicates that around 40% of the uncertainties in projected warming of the tropical Atlantic (40–5°W and 20°S –5°N) is related to weakening of the AMOC (Fig. 1a).

Linear regression map between changes (2050–2100 minus 1950–2000) in ΔAMOC* (Sv °C⁻¹) at 20°S and a ΔSST* (°C °C⁻¹); and b ΔPR* (mm day⁻¹ °C⁻¹). The contours denote the explained variance (or R2). Grey dots indicate areas where the linear regression is statistically significant (p < 0.05). Scatter plots between c ΔAMOC* at 20°S and ΔTA*; d ΔTA* versus ΔENEB*(mm day⁻¹ °C⁻¹); and e ΔAMOC* versus ΔENEB*. The orange lines represent the linear regressions: b (Y = −0.07x +0.5) with R2: 0.45, d (Y = 1.03x -0.7) with R2:0.60, and e (Y = −0.9x −0.19) with R2:0.42. Asterisks (*) indicate that all the variables are divided by ΔGSAT (°C) for each respective CMIP6 model. SST in the tropical Atlantic (ΔTA) is represented by the yellow box in (a), whereas PR in the ENEB region is represented in the magenta box.

Similar regression analysis for precipitation, ΔPR, indicates that a weakening of AMOC can lead to a southward shift of the Atlantic ITCZ (Fig. 1b), consistent with previous findings21. This can eventually lead to increased precipitation in the western equatorial Atlantic and eastern part of Brazil, and decreased precipitation in the north equatorial Atlantic, western Brazil, and equatorial Africa. ΔAMOC explains up to 40% of the uncertainties in projected precipitation in southern ENEB, while it explains 20% or less of the projected uncertainty in the northern region (Fig. 1b).

For a better understanding, we examine these relations using indices. We calculate the SST change over the tropical south Atlantic area (ΔTA) (40°W –5°E and 20°S –5°N), where ΔAMOC explains most of the variance (Fig. 1a). A strong and statistically significant (p value < 0.05) negative correlation of almost −0.7 (Fig. 1c) indicates that the SST over the tropical Atlantic increases as AMOC at 20°S declines. The warming is consistent with accumulating heat content caused by a weaker AMOC and reduced northward heat transport in the Atlantic. In some models, the AMOC at 20°S weakens by up to 3 Sv per degree of global warming. According to the regression relation, this weakening contributes an additional ~0.2 °C warming per degree of global warming in this region (Fig. 1c). This is equivalent to a local amplification of global warming by ~30%.

Previous investigations have established a substantial correlation between SST in the SAWP located in eastern tropical South Atlantic, and precipitation in the ENEB (ΔENEB)26,29,31. This is because, as Atlantic SST increases in this region, sea level pressure drops, increasing atmospheric moisture, eventually promoting convection29,43. The CMIP6 MME shows that projected changes in precipitation in the ENEB region are similarly related to future SST warming in the tropical Atlantic (Fig. 1d). The ΔENEB has a statistically significant positive correlation to ΔSST of approximately 0.80 (p-value < 0.05). Although the MME indicates a decrease in precipitation in the ENEB of –0.07 ± 0.04 mm day⁻¹ °C⁻¹ (95% confidence interval, N = 29 models), inter-model spread remains large (σ = 0.10 mm day⁻¹ °C⁻¹; Fig. 1e). Figure 1d indicates that whether a model predicts a precipitation increase or decrease in this region depends on the level of SST warming in the tropical Atlantic.

Given the high correlation between ΔENEB and ΔTA (Fig. 1d) and between ΔAMOC and ΔTA (Fig. 1c), we further examine the relationship between precipitation and AMOC changes. The scatter plot between ΔENEB and ΔAMOC illustrates a negative linear relation, with increases in precipitation in ENEB correlated to decreases in AMOC (R2 ~ 0.6; Fig. 1e). The negative slope indicates that the AMOC slowdown compensates for decreasing precipitation in the ENEB by accumulating ocean heat and warming the SAWP. As discussed below, the additional ocean heat content is associated with increased evaporation from the ocean, which could enhance moisture convergence and eddy moisture transport and thereby increase precipitation26.

Latent Heat Flux changes on AMOC weakening

We examine the linear relation between latent upward heat flux changes (ΔLHF) and ΔAMOC in the MME to better understand the influence on ENEB precipitation, which is related to moisture convergence over the western South Tropical Atlantic. AMOC decline in the SSP585 scenario leads to an increase in the LHF (as the regression is negative) in the southern branch of the South Equatorial Current (sSEC), which is considered a zonal pathway of the AMOC upper branch and the northern limit of the South Atlantic Subtropical Gyre (Fig. 2). The statistically significant (p value < 0.05) increase in LHF in the western south tropical Atlantic is consistent with a weakening-AMOC driven increase in SST in this region (Fig. 1a). Likewise, in the central south Atlantic Subtropical Gyre, LHF decreases in response to the cooling associated with the weakening AMOC (Fig. 1a).

Linear regression map between ΔAMOC* at 20°S (Sv °C⁻¹), and surface upward latent heat flux changes (ΔLHF* – positive upward) (W m⁻2 °C⁻¹), the contours denote the explained variance (or R2). Asterisks (*) indicate that the variables are divided by ΔGSAT for each respective CMIP6 model. Grey dots indicate areas where the linear regression is statistically significant (p value < 0.05).

In response to these ocean driven SST changes the ITCZ migrates southward in the Atlantic, consistent with the AMOC-forced ITCZ southward shift in past warmer climates44. As the ITCZ shifts further south, LHF decreases in the equatorial region and to the north; in this region, it appears that a decrease in LHF is associated with weaker winds that tend to warm the ocean25. Simultaneously, the positive ΔLHF to the south will also result in more water vapour convergence over the western South Tropical Atlantic. Thus, the increase in heat content of the upper ocean driven by AMOC weakening increases heat flux and moisture content of the lower troposphere and shifts the ITCZ south. This leads to a statistically significant (p value < 0.05) negative LHF-AMOC relation over the northeast of Brazil (Fig. 2). In addition, when the wind is easterly, evaporation in the western south Tropical Atlantic is expected to feed diabatic energy to easterly wave disturbances, which induce extreme precipitation in the ENEB29,30,45. The increase in precipitation over the land seems to drive the increase of LHF in the ENEB (Figs. 1b and 2). Although the AMOC does not exert a direct influence on continental latent heat flux, it modulates large-scale atmospheric circulation, which shapes the latent heat exchange. Consequently, the relationship is indirect yet physically coherent within the framework of coupled ocean–atmosphere interactions.

Estimating the influence of AMOC decline on tropical precipitation and SST

Motivated by the robust impacts of AMOC on precipitation and SST over tropical Atlantic and surrounding regions, we now quantify the contribution of AMOC decline to the total projected MME mean changes in tropical Atlantic precipitation and SST. These are compared to the more direct effects of global warming, which cause robust changes in the hydrological cycle46. We separate the changes conceptually into three parts: one related to the AMOC at 20°S, based on the regressions shown above (Fig. 1a, b); the second is related to GSAT; and the third includes all changes unrelated to either AMOC or GSAT and is assumed to average to zero across the models. After normalising the variables by the ΔGSAT to reduce the impact of different rates of global warming in the different models, we estimate the spatial changes in precipitation and SST using regression analysis. This analysis framework is outlined in the Methods section.

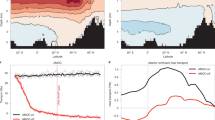

The MME mean projects a uniform and positive ΔSST of up to 0.8 °C per degree of global warming (Fig. 3a). Of this, global warming (ΔGSAT) contributes directly to an increase of up to 0.7 °C in the equatorial region and to the north (Fig. 3c), while the AMOC weakening contributes to a warming around 0.1 °C in the equatorial region and to the south (Fig. 3e). Note the AMOC at 20°S is projected to decrease by 1.14 Sv °C⁻¹. We estimate changes by the end of the century under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, for which the MME mean indicates 3.5 °C global warming and 4 Sv reduction in AMOC at 20 °S. For this level of warming and AMOC weakening, our analysis indicates a direct global warming contribution of 2.5 °C in the tropical Atlantic and an indirect contribution from AMOC weakening of 0.35 °C.

MME mean of a ΔSST and b ΔPR associated with 1 °C of ΔGSAT (°C); and contribution of ΔGSAT to c ΔSST and d ΔPR; contribution of ΔAMOC to e ΔSST and f ΔPR. The contours denote the explained variance (or R2). Asterisks (*) indicate that the variables are divided by ΔGSAT for each respective CMIP6 model. Gray stippling indicates areas where changes are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level, based on a bootstrap resampling of the 1950–2000 climatology to estimate internal variability.

Regarding precipitation, the MME mean projects a decrease of 0.1 mm day⁻¹ per degree of global warming in the north and northeast of Brazil and over the western equatorial Atlantic, while the decrease is much less in the ENEB (Fig. 3b). The direct global warming contribution shows a greater decrease in precipitation that exceeds 0.2 mm day⁻¹ °C⁻¹ in the western equatorial Atlantic and 0.1 mm day⁻¹ °C⁻¹ and in the ENEB (Fig. 3d). This is equivalent to a reduction of ~125 mm y⁻¹ per degree Celsius over the ENEB in a 3.5 °C warmer world, as projected by the MME mean under the SSP5-8.5. These changes follow the expected dry-get-drier paradigm21,39. Consistently, a larger decrease in northeast of Brazil precipitation is found in the high emission-low adaptation scenario (SSP5-8.5) compared to low emission-high adaptation scenarios47. The reduction in precipitation is particularly significant (p value < 0.05) for the northeast region, the driest area in Brazil, which faces substantial climate risks; for example, the Pernambuco State, with 89% of its area affected by drought and low precipitation, is highly vulnerable to climate change48,49,50.

AMOC-weakening compensates for the direct global warming impact on precipitation over the ENEB and the equatorial Atlantic, while over the north-west region (~10°N–10°S and ~70°W–65°W) it enhances the global warming impact (Fig. 3f). Over the ENEB region, the MME mean AMOC-weakening of 1.1 Sv °C⁻¹ increases precipitation by ~0.1 mm day⁻¹ °C⁻¹, almost exactly balancing the direct global warming contribution (Fig. 3d, f). For ΔAMOC of −4 Sv in the MME mean under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the precipitation is expected to increase by approximately 131 mm per year (Fig. 1e). This represents an ~11% increase in precipitation, compared with the annual average precipitation in the ENEB, which is ~1500 mm y⁻¹, according to the National Institute of Meteorology (INMET) (https://portal.inmet.gov.br). Over the Amazon region, the AMOC weakening and global warming reduce precipitation almost equally, with the AMOC signal predominant in the west (~60°W). These results are consistent with studies investigating AMOC shutdown experiments26.

The AMOC weakening drives precipitation changes in the tropical Atlantic and in the ENEB through the SST changes. The AMOC-weakening warms the equatorial and south Atlantic, inducing a cross-equatorial SST gradient (Fig. 3e). This causes the Atlantic ITCZ to shift south (Fig. 3f), as its location is closely related to the cross-equatorial SST gradient51,52,53. This mechanism is found in model experiments with strong AMOC weakening54,55. The increased precipitation in the ENEB is connected to the ITCZ southward shift (Fig. 3f). Next, we examine AMOC-weakening impacts on extreme precipitation events in the ENEB, which is vulnerable to such extremes.

Extreme precipitation changes

In the ENEB, 60% of precipitation comes from mesoscale meteorological systems like Easterly Waves56. We identify changes of the extreme indices related to the AMOC at 20°S and global mean surface temperature (GSAT), and we normalize the variables by the ΔGSAT (see Methods). Here we investigate the impact of AMOC decline on extreme precipitation, considering the maximum amount of ΔPR accumulated over one day (ΔRx1day, mm °C⁻¹) and over five days (ΔRx5day, mm °C⁻¹), and daily precipitation >99th percentile (ΔR99p, mm °C⁻¹).

The extreme precipitation indices are similarly correlated to ΔAMOC (Fig. S3), although with varying degrees of intensity (Fig. 4). A weakening AMOC leads to substantial increase in the precipitation extremes (Fig. 4g–i) over the Amazon, northeast, and southeast of Brazil, as well as the center of SEC path and close to the Agulhas Current system. The changes in the ΔRx5day are more considerable over the Amazon. Therefore, we now estimate how much the AMOC reduction contribute to precipitation-extreme indices over Brazil and contrast them to the direct consequences of global warming, under the SSP5-8.5 scenario (Fig. 4).

MME mean of a ΔRx1day, b ΔRx5day and c ΔR99p associated with 1 °C of ΔGSAT (°C); contribution of ΔGSAT to d ΔRx1day, e ΔRx5day and f ΔR99p; and contribution of ΔAMOC to g ΔRx1day, h ΔRx5day and i ΔR99p. The contours denote the explained variance (or R2). Asterisks (*) indicate that the variables are divided by ΔGSAT for each respective CMIP6 model. Gray stippling indicates areas where changes are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level, based on a bootstrap resampling of the 1950–2000 climatology to estimate internal variability.

The MME mean projects a similar pattern of change for all three extremes precipitation indices (Fig. 4a–c) per degree of global warming, but with different magnitude. There is an increase of ~3 mm °C⁻¹ in ΔRx1day (Fig. 4a) and ~5 mm °C⁻¹ in ΔRx5day (Fig. 4b), and ~20 mm °C⁻¹ in ΔR99p (Fig. 4c) over the north part and northeast of Brazil, and north equatorial Atlantic.

Considering the direct global warming contribution, there is an increase in extremes precipitation over most of Brazil, except for a small region in the north (Fig. 4d–f). The ΔRx1day (Fig. 4d) and ΔRx5day (Fig. 4e) show a decrease of over ~−3 mm °C⁻¹ in the north of Brazil. On the other hand, there are increases of up 3 to 5 mm °C⁻¹ over the southeast of the country (Fig. 4d, e), and of ~10 mm °C⁻¹ for the ΔR99p (Fig. 4f) over the northeast of Brazil with high agreement among the models. This is equivalent to an increase of ~18 mm in ΔRx5day (Fig. 4e) over the northern part of the ENEB and southeast of Brazil in a 3.5 °C warmer world, as projected by the MME mean under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. We observe an even stronger increase in the northwest of Africa with precipitation extremes expected to double. These changes are consistent with the wet-get-wetter paradigm under climate change57.

AMOC-weakening drives a substantial increase in accumulated extreme precipitation in the north and northeast of Brazil, while the intensity increases in the north and decreases in the southwest part of Amazon. The increase of ~1 mm °C⁻¹ in ΔRx1day (Fig. 4g), ~5 mm °C⁻¹ in ΔRx5day (Fig. 4h), and ~10 mm °C⁻¹ in ΔR99p (Fig. 4i) over north of Brazil compensates the decrease in extreme precipitation caused from the direct global warming part. For ΔAMOC of −4 Sv in the MME mean under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the ΔRx5day increases up to 14 mm (Fig. 4h) over the ENEB and 70 mm in north of Brazil. AMOC-weakening contributes to drier extreme conditions (~5 mm °C⁻¹) over the southwest and wetter extreme conditions in the north of the Amazon (~20 mm °C⁻¹) and in the northeast (~10 mm °C⁻¹), as well as in the ENEB where there is an increase ~5 mm °C⁻¹ for ΔR99p (Fig. 4i). Like the mean precipitation changes, a weakened AMOC influence on extreme precipitation is of similar magnitude to the global warming impact and can even dominate the response over North Brazil.

Our results indicate that the AMOC signal on extreme precipitation is scale-dependent, being weaker for the high-frequency (Rx1day) and more pronounced for lower-frequency (Rx5day) metrics. This pattern likely arises because lower-frequency precipitation indices integrate moisture anomalies over several days, making them more sensitive to large-scale circulation changes and SST anomalies linked to AMOC variability. Conversely, high-frequency precipitation reflects a wider range of processes, including local convection and synoptic variability, which may dilute the AMOC influence. The statistical significance analysis further confirms that the AMOC-related signal is more robust for lower-frequency extremes, highlighting the importance of considering the temporal scale when assessing AMOC impacts on precipitation.

Discussion

We investigated how a possible future AMOC decline (defined as CMIP6 historical minus SSP5-8.5 simulations) modulates the tropical Atlantic SST, LHF, mean precipitation, and precipitation extremes, by analyzing MME of CMIP6 models. As previous studies have shown, global warming is projected to bring warmer and drier conditions in north and northeast Brazil47,58. The main effect of an AMOC weakening is to warm tropical Atlantic SST (Figs. 1a, c and 3e) and increase LHF, leading to wetter conditions in the ENEB and drier conditions in the north of Brazil (Figs. 1b, e and 3f). Thus, a weakened AMOC partially offsets the drier conditions expected from global warming in northeast Brazil and amplifies the drier and warmer scenario over northern Brazil, especially in the Amazon. We emphasize the role of the ocean in driving precipitation changes, in contrast to previous studies that focused on changes in the atmospheric poleward heat transport59.

Our new findings on rainfall extremes are another novel aspect, which has revealed the intricate influences of AMOC decline on hydrometeorological climate in Brazil. Global warming is expected to increase extreme precipitation over most of Brazil. The AMOC weakening in some regions and for some extreme indices amplifies the global warming signal, while in others it offsets them: In the northwest of Brazil, especially in the northern part of the Amazon, the AMOC weakening intensifies extreme precipitation (R99p, Rx1day, and Rx5day), while global warming reduces extremes in this region. In the ENEB, AMOC weakening intensifies the R99p. Interestingly, in some regions the response of the precipitation extremes to the weakening AMOC is like that found for mean precipitation (e.g., ENEB for the R99p), while in other regions it is the opposite. The similar response of mean and extreme precipitation in the ENEB to the AMOC weakening is associated with the southward-shifted ITCZ and local ocean warming that leads to the wetter conditions, favoring the instability of meteorological systems29, and the intensification of the easterly waves29,30. The opposite response of AMOC weakening on the mean and extreme precipitation in the northwest is like the impact global warming, which can lead to increased surface temperatures and altered precipitation patterns.

The impact of the AMOC weakening on the extreme and mean precipitation in the north of Brazil and on mean precipitation in the ENEB is robust, while the impact on extreme precipitation in the ENEB is less substantial. The robust impacts are associated with large-scale features, such as the southward ITCZ shift. The uncertainty for the ENEB could be linked to small-scale processes that are poorly resolved in climate models, such as easterly wave disturbances. This is also reflected in the inaccurate simulation of the seasonal rainfall cycle by the models, which typically show the maximum precipitation in February–March rather than the observed peak between May and July (Fig. S2). Despite these errors and uncertainties, an increase in precipitation extremes over the ENEB is expected due to regional SST warming in the western equatorial Atlantic, associated with AMOC weakening. These results suggest that the potential impact of global warming on severe precipitation events may be underestimated in the ENEB. This is a concern for the already vulnerable ENEB region where the extreme events are projected to increase. Further tools for investigation, such as CORDEX-South America (https://cordex.org/domains/cordex-region-south-america-cordex/), could help understand model uncertainty60.

While global warming exerts drastic regional effects over Brazil, where the ENEB and the Amazon are at increasing risk of dryness, the AMOC change can substantially modulate these impacts. Our results show that the AMOC weakening can partially offset the projected drying in the ENEB while intensifying it in northern Brazil, especially in the Amazon region. Regarding extreme precipitation, the AMOC acts as a compensating mechanism for climate change, adding complexity and uncertainty to future projections. In the ENEB region, this modulation may result in more frequent events. These findings underscore the importance of reducing uncertainties related to the AMOC’s response to global warming to better constrain regional climate projections and inform effective adaptation strategies in vulnerable areas. Recent emergent constraint analysis has suggested a potential to reduce such uncertainties37,61 but ultimately models that better represent processes driving AMOC weakening and its climate impacts are required17,36,38.

Methods

CMIP6 data

We use MME of CMIP6 simulations32 following the historical and SSP5-8.5 scenarios62, which is a high-end forcing scenario with a global mean radiative forcing of 8.5 W m−2 by 2100 and low climate change adaptation strategies. We use the AMOC, SST, precipitation, global surface air temperature, and surface upward latent heat flux data from 29 CMIP6 models (Table S1 in Supporting Information S1). The data is at monthly temporal resolution. The datasets, except for AMOC, are interpolated to a common 1° × 1° grid before analysis. Only one ensemble member for each model is used. For most models, we selected member r1i1p1f1, but for 11 models, the r1i1p1f1 was not available when we accessed the database; hence, we used other ensemble members (Table S1 in Supporting Information S1). For the analysis of precipitation extremes indices based on daily precipitation rates, we had access to data from 22 of the 29 models (Table S2 in Supporting Information S1).

Framework for assessing changes in climate indices

Our analysis focuses on the projected changes from 2050 to 2100 (SSP5-8.5) relative to 1950–2000 (for historical). We compute the change in a variable, V, for a particular model, m, as follows:

Where the overbar represents an average over the different 50-year periods, and the ΔV represents the change of the variable.

We analyze the following variables: the AMOC_20°S and AMOC_30°N indices, computed as the maximum of the ocean meridional overturning stream function at 20°S (the closest to 34°S found for most models) and at 30°N in the Atlantic for each year; The SST mean index (ΔTA) for the tropical Atlantic (40°W–5°E and 20°S–5°N), as well as the precipitation mean index (ΔPR) for the ENEB region (40–35°W and 15–4°S) and the latent upward heat flux changes (ΔLHF). We examine the relationship between AMOC indices and each variable.

We also analyze annual mean precipitation and Climpact indices (https://climpact-sci.org/indices/) of annual total precipitation from very wet days (R99p), monthly maximum 1-day (Rx1day), and 5-day precipitation amount (Rx5day)63. R99p is defined as the annual sum of days when the precipitation exceeds the 99th percentile of wet-day precipitation amounts, with the percentile calculated over the baseline period 1981–2010 (Text S1 in Supporting Information S1).

Isolating AMOC influences from other global warming impacts

We use output from the MME to estimate the influences of AMOC (denoted ΔAm) decline and other global warming (ΔGm) influences on SST, mean and extremes precipitation, assuming the following decomposition:

Where ΔVV represents the decomposition variable (PR, SST, Rx1day, Rx5day, and R99p), subscript m denotes a specific model, and ΔZm changes independent of ΔGm and ΔAm. In the following, we neglect ΔZm, assuming that there are no other systematic influences on ΔPR, ΔSST, ΔRx1day, and ΔRx5day and ΔR99p. While this assumption is questionable, the overall high explained variances of our results suggest it is reasonable. PA and GA are the spatial patterns associated with a unit change in AMOC and global warming.

ΔGm is defined as the change in global mean surface air temperature. The CMIP models simulate a wide range of global warming, as they have diverse climate sensitivity. The large spread makes it difficult to isolate the direct impact of AMOC on SST, mean, and extreme precipitation, as they are strongly influenced by global warming. To reduce this confounding influence, we divide each term in Eq. (2) by ΔGm (*); the rescaled variables are denoted with a *21.

Here, we redefined separately the variables:

We estimate the spatial patterns using regression analysis across the ensemble of different models.

Where \(< \ldots > m\) is the covariance computed across the models.

From this equation, we estimate the change in SST, mean, and extremes precipitation due to the mean AMOC change:

Where \(\frac{1}{M}{\sum }_{i=1}^{M}V\) is the term of the variable model mean change and \(\frac{{\boldsymbol{1}}}{{\boldsymbol{M}}}{\sum }_{{\boldsymbol{i}}={\boldsymbol{1}}}^{{\boldsymbol{M}}}\left({\Delta {{\boldsymbol{A}}}_{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}^{{\boldsymbol{* }}}\right)\) is the model mean change in AMOC (Sv) for 1 °C change in global mean temperature.

Then we can estimate the change in SST, mean, and extremes precipitation for 1 °C change in global mean temperature:

The first term on the right is the multimodel mean.

Statistical tests

We compute the regression coefficients (slopes), Spearman rank correlation64, and statistical metrics (R² and p values) to understand consistency and divergence across simulations. In estimating statistical significance, we assume independence of each model. Therefore, we evaluated CMIP6 (Text S1 in Supporting Information S1) model agreement using ensemble spread analysis.

Statistical significance was assessed using a bootstrap resampling approach applied to the historical period (1950–2000) to represent present-day internal variability. For each model and grid point, 100 bootstrap climatologies were generated by resampling years with replacement. Then, 1000 multi-model combinations were created by randomly selecting one bootstrap climatology per model and computing the MME mean for the historical. This provides a distribution representing statistical uncertainty in each model’s climatology based on sampling of its internal climate variability. The differences between the anomalies and the bootstrapped historical climatologies were calculated, and the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of these differences were computed. If zero falls outside this range, the difference is defined as statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Statistically significant locations are indicated by stippling in Figs. 3–4.

Data availability

The CMIP6 data used in this study are available from ESGF (https://esgf-ui.ceda.ac.uk) with references listed in Supporting Information S1 (Table S1).

Code availability

Available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Buckley, M. W. & Marshall, J. Observations, inferences, and mechanisms of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation: a review. Rev. Geophys. 54, 5–63 (2016).

Häkkinen, S., Rhines, P. B. & Worthen, D. L. Heat content variability in the North Atlantic Ocean in ocean reanalyses. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 2901–2909 (2015).

Kostov, Y., Armour, K. C. & Marshall, J. Impact of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation on ocean heat storage and transient climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2108–2116 (2014).

Marshall, J., Donohoe, A., Ferreira, D. & McGee, D. The ocean’s role in setting the mean position of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone. Clim. Dyn. 42, 1967–1979 (2014).

Qiyun, M. et al. Revisiting climate impacts of an AMOC slowdown: dependence on freshwater locations in the North Atlantic. Sci. Adv. 10, eadr3243 (2024).

Rahmstorf, S. et al. Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 475–480 (2015).

Caesar, L. et al. Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nature 556, 191–196 (2018).

Weijer, W., Cheng, W., Garuba, O. A., Hu, A. & Nadiga, B. T. CMIP6 models predict significant 21st century decline of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086075 (2020).

Van Westen, R. M., Kliphuis, M. & Dijkstra, H. A. Physics-based early warning signal shows that AMOC is on tipping course. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk1189 (2024).

Latif, M., Sun, J. et al. Natural variability has dominated Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation since 1900. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 455–460 (2022).

Le Bras, I. A.-A., Willis, J. & Fenty, I. The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation at 35°N from deep moorings, floats, and satellite altimeter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101931 (2023).

Pita, I. et al. An ARGO and XBT observing system for the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation and Meridional Heat Transport (AXMOC) at 22.5°S. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 129, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JC020010 (2024).

Pita, I., Goes, M., Volkov, D. L., Dong, S. & Schmid, C. South Atlantic meridional overturning circulation and its respective heat and freshwater transports from sustained observations near 34.5° S. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1474133 (2024).

Zhang, R. et al. A review of the role of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation in Atlantic multidecadal variability and associated climate impacts. Rev. Geophy. 57, 316–375 (2019).

Liu, W., Fedorov, A. V., Xie, S. P. & Hu, S. Climate impacts of a weakened Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation in a warming climate. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz4876 (2020).

Pontes, G. M. & Menviel, L. Weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation driven by subarctic freshening since the mid-twentieth century. Nat. Geosci., 17, 1291–1298 (2024).

Bellomo, K. et al. Future climate change shaped by inter-model differences in Atlantic meridional overturning circulation response. Nat. Commun. 12, 3659 (2021).

Nian, D. et al. A potential collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation may stabilise eastern Amazonian rainforests. Commun. Earth Environ., 4, 470 (2023).

Akabane, T. K. et al. Weaker Atlantic overturning circulation increases the vulnerability of northern Amazon forests. Nat. Geosci. 17, 1284–1290 (2024).

Schneider, T., Bischoff, T. & Haug, G. Migrations and dynamics of the intertropical convergence zone. Nature 513, 45–53 (2014).

Back, L. E. & Bretherton, C. S. On the relationship between SST gradients, boundary layer winds, and convergence over the tropical oceans. J. Clim. 22, 4182–4196 (2009).

Gordon, A. L. Interocean exchange of thermocline water. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 5037–5046 (1986).

Speich, S., Blanke, B. & Madec, G. Warm and cold water routes of an OGCM thermohaline conveyor belt. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 311–314 (2001).

Dickson, R., Lazier, J., Meincke, J., Rhines, P. & Swift, J. Long-term coordinated changes in the convective activity of the North Atlantic. Prog. Oceanogr. 38, 241–295 (1996).

Foltz, G. R. & McPhaden, M. J. The role of oceanic heat advection in the evolution of tropical north and south Atlantic SST anomalies. J. Clim. 19, 6122–6138 (2006).

Hounsou-gbo, G. A., Araujo, M., Bourlès, B., Veleda, D. & Servain, J. Tropical Atlantic contributions to strong rainfall variability along the northeast Brazilian coast. Adv. Meteorol. 2015, 902084 (2015).

Ferreira, N. J., Chou, S. C., & Prakki, S. Analysis of Easterly wave disturbances over South Equatorial Atlantic Ocean. In Proc. XIth Brazilian Congress of Meteorology (AMS, 1990).

Torres, R. R. & Ferreira, N. J. Case studies of Easterly wave disturbances over Northeast Brazil using the Eta Model. Wea. Forecast. 26, 225–235 (2011).

Silva, T. L., do, V., Veleda, D., Araujo, M. & Tyaquiçã, P. Ocean–atmosphere feedback during extreme rainfall events in Eastern Northeast Brazil. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol. 57, 1211–1229 (2018).

Koseki, S., Vilela, I. & Veleda, D. A dynamical perspective of the extreme rainfall event over Eastern Northeast Brazil in May 2022. Meteorol. Appl. 32, e70046 (2025).

Cavalcanti, E. P., Gandu, A. W. & Azevedo, P. V. D. Transporte e balanço de vapor d'água atmosférico sobre o Nordeste do Brasil. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 17, 207–217 (2002).

Junior, F. D. C. V. et al. An attribution study of very intense rainfall events in Eastern Northeast Brazil. Weather Clim. Extremes 45, 100699 (2024).

Marengo, J. A. et al. Flash floods and landslides in the city of Recife, Northeast Brazil after heavy rain on May 25–28, 2022: Causes, impacts, and disaster preparedness. Weather Clim. Extremes 39, 100545 (2023).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geo Sci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Baker, J. A. et al. Overturning pathways control AMOC weakening in CMIP6 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103381 (2023).

Bonnet, R., Swingedouw, D., Gastineau, G. et al. Increased risk of near term global warming due to a recent AMOC weakening. Nat. Commun. 12, 6108 (2021).

Park, I. H. et al. Present-day North Atlantic salinity constrains future warming of the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 816–822 (2023).

Park, I.-H. et al. North Atlantic warming hole modulates interhemispheric asymmetry of future temperature and precipitation. Earth’s Future 12, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023EF004146 (2024).

Gregory, J. M. et al. A model intercomparison of changes in the Atlantic thermohaline circulation in response to increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, 112703 (2005).

Weaver, A. J. et al. Stability of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation: a model intercomparison. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L20709 (2012).

Winton, M. W. G. et al. Has coarse ocean resolution biased simulations of transient climate sensitivity?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 8522–8529 (2014).

Reintges, A., Martin, T., Latif, M. & Keenlyside, N. S. Uncertainty in twenty-first century projections of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation in CMIP3 and CMIP5 models. Clim. Dyn. 49, 1495–1511 (2017).

Wang, C. & Lee, S.-K. Atlantic warm pool, Caribbean low-level jet, and their potential impact on Atlantic hurricanes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L02703 (2007).

Kraft, L. et al. AMOC-forced southward migration of the ITCZ under a warm climate background. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 661, 112705 (2025).

Kouadio, Y. K., Servain, J., Machado, L. A. & Lentini, C. A. Heavy rainfall episodes in the eastern Northeast Brazil linked to large-scale ocean-atmosphere conditions in the tropical Atlantic. Adv. Meteorol. 2012, 369567 (2012).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Dantas, L. G., dos Santos, C. A., Santos, C. A., Martins, E. S. & Alves, L. M. Future changes in temperature and precipitation over northeastern Brazil by CMIP6 model. Water 14, 4118 (2022).

CEPED – CENTRO DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EM ENGENHARIA E DEFESA CIVIL. 2020. Relatório de danos materiais e prejuízos decorrentes de desastres naturais no Brasil: 1995-2019/Banco Mundial. Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery. Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Extensão Universitária. Centro de Estudos e Pesquisas em Engenharia e Defesa Civil. (Organized by Rafael Schadeck). 2. ed. Florianópolis: FAPEU.

Marengo, J. A., Torres, R. R. & Alves, L. M. Drought in Northeast Brazil—past, present, and future. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 129, 1189–1200 (2017).

de Oliveira, V. H. Natural disasters and economic growth in Northeast Brazil: evidence from municipal economies of the Ceará State. Environ. Dev. Econ. 24, 271–293 (2019).

Waliser, D. E. & Gautier, C. A satellite-derived climatology of the ITCZ. J. Clim. 6, 2162–2174 (1993).

Nobre, P. & Shukla, J. Variations of sea surface temperature, wind stress, and rainfall over the Tropical Atlantic and South America. J. Clim. 9, 2464–2479 (1996).

Chiang, J. C. H., Kushnir, Y. & Giannini, A. Deconstructing Atlantic Intertropical convergence zone variability: influence of the local cross-equatorial sea surface temperature gradient and remote forcing from the eastern equatorial Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. 107, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JD000307 (2002).

Ciemer, C., Winkelmann, R., Kurths, J. et al. Impact of an AMOC weakening on the stability of the southern Amazon rainforest. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 230, 3065–3073 (2021).

Zhang, R. & Delworth, T. L. Simulated tropical response to a substantial weakening of the Atlantic thermohaline circulation. J. Clim. 18, 1853–1860 (2005).

Gomes, H. B. et al. Climatology of easterly wave disturbances over the tropical South Atlantic. Clim. Dyn. 53, 1393–1411 (2019).

Xiong, J., Guo, S., Abhishek, Chen, J. & Yin, J. Global evaluation of the “dry gets drier, and wet gets wetter” paradigm from a terrestrial water storage change perspective. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 6457–6476 (2022).

Espinoza, J. C., Jimenez, J. C., Marengo, J. A. et al. The new record of drought and warmth in the Amazon in 2023 related to regional and global climatic features. Sci. Rep., 14, 8107 (2024).

Bellomo, K. et al. Impacts of a weakened AMOC on precipitation over the Euro-Atlantic region in the EC-Earth3 climate model. Clim. Dyn. 61, 3397–3416 (2023).

Akinsanola, A. A. et al. Amplification of synoptic to annual variability of West African summer monsoon rainfall under global warming. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 21 (2020).

Bonan, D. B. et al. Observational constraints imply limited future Atlantic meridional overturning circulation weakening. Nat. Geosci. 18, 479–487 (2025).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The scenario model intercomparison project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Indices for monitoring changes in extremes based on daily temperature and precipitation data. WIREs Clim. Change 2, 851–870 (2011).

Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 100, 441–71 (1987).

Acknowledgements

I. Vilela would like to thank the Fundação de Amparo à Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Pernambuco (FACEPE) (Grant IBPG-1210-1.08/18) and CAPES-PRINT (Grant 88887.717529/2022-00). This work was supported by the Partnership for Observation of the Global Ocean (POGO) and the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR) through the POGO–SCOR Visiting Fellowship awarded in 2022. I.V., D.V., S.K. and N.K. are grateful to the TRIATLAS Project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement Number 817578. I.V., T.S. and D.V. thank the SIMOPEC Project, funded by the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq), Grant Number 406707/2022-7, and the Project Climate analysis and coupled ocean-atmosphere modeling of extreme events in response to warming in the Brazil-Malvinas Confluence Region—CNPq Grant 421049/2023-5. N.K. and S.K. acknowledge funding from Research Council of Norway (Grant Numbers 309562; 328935).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.V. prepared the AMOC, global surface air temperature, sea surface temperature, mean precipitation, latent heat flux datasets, conceived the methods, performed the analyses, created the figures, and wrote the first paper draft. N.K. contributed to the methods, verified the figures and conclusions. P.D.L. prepared the mean and extreme precipitation datasets. S.K. contributed to the analyses. I.V., S.K., T.S., P.D.L. and D.V. contributed to the discussed results and verified the figures. I.V., N.K. and D.V. contributed to the writing. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vilela, I., De Luca, P., Koseki, S. et al. AMOC weakening modulates global warming impacts on precipitation over Brazil. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01248-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01248-w