Abstract

Understanding the interannual variability of summer precipitation across the Central-Eastern Himalayas (CEH) is essential for guiding efficient water management and supporting socio-economic development in South Asia. However, the mechanisms through which climate variability shapes CEH summer precipitation variability remain insufficiently understood. Summer precipitation in the CEH is modulated by multiple climate factors, with the El Niño–Southern Oscillation as a sustained weak force and the summer North Atlantic Oscillation (SNAO) exerting non-stationary effects. The SNAO can trigger an anomalous anticyclone over South Asia, directing low-level winds toward the Himalayas’ southern slopes, inducing precipitation anomalies through topographic mechanical forcing. The position shift of the SNAO-driven anomalous anticyclone to the south of the CEH modulates the coupled and decoupled relationship between SNAO and CEH summer precipitation variability. Therefore, understanding the dynamic links between the SNAO and CEH summer precipitation is key to enhancing precipitation prediction accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Himalayas influence regional climate, harbor rich biodiversity, and serve as a crucial water source for more than one-third of the global population1,2,3. In the Central-Eastern Himalayas (CEH), the majority of glaciers receive their main mass input during the summer monsoon season, a pattern that differs markedly from that in the northwestern Himalayas, where accumulation is dominated by winter snowfall4. This dichotomy in accumulation patterns underscores the need for region-specific studies. Additionally, global warming has notably reshaped water resource distribution, leaving the CEH as one of the most climate-sensitive regions5,6,7. During the last fifty years, precipitation in the CEH has generally increased8,9,10,11. Precipitation in the CEH also exhibits pronounced interannual variability superimposed on the long-term trend, exerting a significant influence on regional water resources12,13. Understanding this variability is crucial for predicting and modeling future freshwater availability in South Asia14.

Precipitation from June to August has contributed close to four-fifths of the yearly precipitation in the CEH2,15,16. Year-to-year fluctuations in summer precipitation across the southern Tibetan Plateau (STP), which encompasses the CEH, arise from interactions between tropical forcing and mid-to-high-latitude climate anomalies17,18. Tropical climate drivers, particularly the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), exert a notable and sustained influence on the year-to-year fluctuations of summer precipitation over the STP, mainly through their modulation of both interannual and intraseasonal variability within the South Asian summer monsoon system19,20,21,22,23. Additionally, mid-to-high-latitude climate signals can influence atmospheric circulation patterns over the STP via stationary Rossby wave propagation24,25,26. Among these factors, the Summer North Atlantic Oscillation (SNAO) is increasingly acknowledged as a key climate driver of the interannual precipitation anomalies in the interior of eastern and southern parts of the Tibetan Plateau (TP)24,26,27,28. The CEH lies along the southern margin of the TP, forming a transitional zone between the high-altitude TP interior and the Indian subcontinent. However, existing studies lack investigation into the impacts of climate variability on the CEH summer precipitation. The unique topography of the CEH acts as a natural barrier (Fig. 1a), profoundly influencing the precipitation patterns. Globally and regionally, topography is recognized as a crucial determinant of precipitation spatial patterns29. Our study primarily examines the complex interactions among climate variability, atmospheric circulation, and topography shape year-to-year changes in summer precipitation across the CEH.

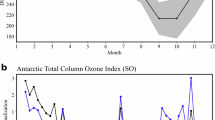

a Location and DEM of the Central-Eastern Himalayas (CEH). The region outlined by the solid black line marks the CEH boundary as defined by Liu, et al.68. The solid blue line represents the major rivers. Pink dots mark the positions of of observation stations. b Comparison of summer (JJA-mean) precipitation (Preci.) abnormal for the CEH from different products, including their root mean square error (RMSE) and correlation coefficient (Corr) against observations. c 9-, 11-, and 13-year sliding correlation sequences between summer CEH precipitation (GPCC) and selected climate indexes. d Correlation field between GPCC summer CEH precipitation and SNAO index from 1994 to 2010. The hatching indicates areas with statistical significance above the 95% confidence level.

To address this gap, this study pursues three objectives: (1) investigating the critical influencing factors and mechanisms in the interannual variability of summer precipitation in the CEH; (2) revealing the difficulties in developing reliable models for predicting summer precipitation; (3) suggesting potential strategies for the climate community to enhance prediction accuracy. The organization of the following sections is outlined as follows: Section 2 discusses the main factors governing fluctuations in CEH summer precipitation and explains the related atmospheric processes; Section 3 highlights the main results and discusses future perspectives regarding the challenges and strategies for accurately predicting CEH summer precipitation; finally, Sections 4 and 5 elaborate on the analytical methods and observational datasets used.

Results

Validation of precipitation datasets

Figure 1b illustrates the interannual fluctuations of summer precipitation anomalies across the CEH, based on records from 59 rain gauges during 1985–2019. The anomalies in gridded precipitation products, e.g. the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC; 1985–2019, 0.5°), the Asian Precipitation-Highly Resolved Observational Data Integration Towards Evaluation (APHRO; 1985–2015, 0.25°), the Climatic Research Unit (CRU; 1985–2019, 0.5°), and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts reanalysis version 5 (ERA5; 1985–2019, 0.25°), were also compared in this figure. Among these, GPCC demonstrates the best agreement with observations, yielding a correlation coefficient (Corr) of 0.96 (p < 0.01) and the lowest root mean square error (RMSE: 12.49 mm/month), with ERA5 ranking second. Supplementary Fig. 1 presents the spatial correlation between the summer precipitation time series from 59 rain gauges in the CEH and four gridded precipitation datasets (GPCC, APHRO, CRU, and ERA5). GPCC shows the highest consistency with rain gauges, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.6 at 39 (52.2%) of the 59 rain gauges for the period 1985–2019. In contrast, the corresponding proportions are 8.0% for ERA5 (1985–2019), and 0% for both CRU (1985–2019) and APHRO (1985–2015). Supplementary Table 1 further confirms that GPCC also achieves the lowest RMSE at most rain gauges, indicating its superior performance among the four datasets.

Notably, the gauge-based GPCC dataset is derived from over 67,000 quality-controlled stations worldwide, each with at least 10 years of data30. In the CEH, GPCC includes more quality-controlled rain gauge stations in the CEH than the 59 gauges used in this study for summer seasons from 1985 to 2019 (not shown). This extensive station coverage enhances the reliability of GPCC in representing precipitation across the entire CEH. Furthermore, previous studies have consistently validated the accuracy of gauge-based GPCC in capturing precipitation variability over the Himalayas31,32,33. Consequently, GPCC was selected as the foundation for further analysis in this study. After bilinearly interpolating GPCC and CRU data to the 0.25° resolution of APHRODITE and ERA5, the differences between interpolated and native-resolution precipitation were minor (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Three-phase division of SNAO influence on summer precipitation in the CEH

Figure 1c shows the 9-, 11-, and 13-year sliding correlations between the CEH summer precipitation (GPCC) and SNAO index during 1985–2019. Based on the abrupt shifts in the 9-year sliding correlation between adjacent years, two key years—1994 (when the 9-year sliding correlation increased from 0.16 the previous year to 0.68) and 2010 (when it dropped from 0.30 to –0.07)—were selected as dividing points to partition the 35-year period into three distinct phases. Phase 2 (1994–2010) has a high Corr of 0.75, whereas Phase 1 (1985–1993; Corr = 0.15) and Phase 3 (2011–2019; Corr = –0.31) have weaker correlations compared to Phase 2. The sliding correlation results for APHRO, CRU, and ERA5 summer precipitation in the CEH and the SNAO index are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Supplementary Fig. 3a, 3c, and 3e exhibit a distinct unimodal pattern in their sliding correlation coefficients with the SNAO, indicating a prominent non-stationary period of high correlation. However, the duration of this high-correlation phase differs across the datasets. For the 9-year sliding correlation, notable shifts in correlation occur in 1994 and 2013 for APHRO, 1994 and 2004 for CRU, and 1994 and 2011 for ERA5.

Figure 1d illustrates the Corr between GPCC summer precipitation and the SNAO index at each grid point across the CEH. The summer precipitation in more than 20% of the grid points in the CEH shows a Corr greater than 0.5 with the SNAO index in Phase 2. Furthermore, Supplementary Fig. 4b shows a sustained negative association between CEH summer precipitation and the contemporaneous ENSO signal (represented by the Niño 3.4 index, source: NOAA Climate Prediction Center) across all three phases. The corresponding correlation coefficients are –0.49 in Phase 1, –0.57 in Phase 2, and –0.63 in Phase 3, each significant at the 95% confidence level. These findings indicate that the interannual variability of CEH summer precipitation is jointly governed by multiple climate modes, with ENSO exerting a relatively sustained influence and SNAO introducing stronger variability that can substantially alter the precipitation distribution under specific phases. A deeper understanding of the coupled and decoupled dynamical mechanisms through which the SNAO influences CEH summer precipitation is crucial. Such understanding is key to interpreting changes in local precipitation regimes and improving prediction accuracy.

Physical mechanism of SNAO-dominated CEH summer precipitation in Phase 2

Supplementary Fig. 5b shows that the SNAO has induced a positive anomaly distribution of summer precipitation in Phase 2 across most of the CEH. To explore the mechanisms through which the SNAO regulates CEH summer precipitation variability, we conducted an analysis of the atmospheric moisture budget. The aggregated terms on the right side of Eq. 1, derived from ERA5 reanalysis, show strong consistency with precipitation anomalies obtained from GPCC observations (Fig. 2a). This means that the moisture budget analysis from ERA5 is reliable. Figure 2b illustrates how different components of the atmospheric moisture budget, associated with the SNAO, contribute to enhanced rainfall anomalies in the CEH. The positive precipitation anomaly (0.88 mm/day) is primarily caused by vertical moisture advection (–<wdq>'; 0.97 mm/day). Among the vertical moisture advection processes, the dynamic term \({(\!-\!\!\!<\!\!\!w\mbox{'}d\bar{\text{q}}\!\!\!>\!)}\) makes the largest contribution to the positive precipitation anomaly, reaching 0.91 mm/day.

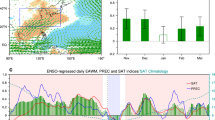

a The total atmospheric moisture budget associated with summer precipitation (preci.) anomalies over the CEH (black dashed line in (c)), together with the observed precipitation anomalies during Phase 2. b Atmospheric moisture budget terms regressed onto the SNAO index, expressed in mm/day. c Regression patterns of the 500 hPa horizontal wind field (Vh) and vertical velocity (ω) onto the SNAO index. d Meridional mean (20–35°N, 76.5–97.0°E, as marked in (c)) zonal-height section showing regressions of meridional wind (vh), ω, and the topographic-induced vertical velocity (ωc) onto the SNAO index. The vector represents the composite wind of vh (m/s) and ω (-1×10⁻¹ Pa/s); shading indicates ω (10⁻³ Pa/s), and contour lines represent ωc (0.001 and 0.003; 10⁻¹ m/s). Orography is indicated by the black shading, and hatched areas highlight regions exceeding the 95% confidence threshold.

Figure 2c shows that the SNAO triggered a 500 hPa anomalous anticyclone to the south of the CEH. The circulation anomalies triggered by the SNAO alone cannot explain the mechanistic diagnosis of the positive CEH precipitation anomalies based on Eq. 1. Further analysis of Fig. 2c reveals a key dynamical link: the anomalous anticyclone steered winds toward the southern slope of the CEH, subsequently leading to the formation of significant upward airflow over most of the CEH. Given the steep northward ascent of the CEH’s topography, we hypothesize that the observed precipitation anomalies arose from an interplay between the SNAO-driven circulation anomalies and topographic mechanical forcing. To verify this hypothesis, we plotted the zonal cross-sectional profiles to quantitatively describe the topographic-induced vertical velocity (ωc). The results indicate that the anticyclonic circulation induced by the SNAO caused subsidence south of the CEH (20–25°N). As this subsiding airflow approached the steep southern slope of the CEH, it was mechanically lifted, generating a pronounced region of upward motion. This region of upward motion precisely overlaps with the region of topographic-induced upward vertical velocity (represented by the red contours in Fig. 2d).

The climatological distributions of near-surface and 650 hPa ωc in the CEH in Phase 2 are shown in Fig. 3a, b. Notably, the 650 hPa pressure level approximately coincides with the mean elevation of the CEH topography. The climatological ωc at both near-surface and 650 hPa levels indicates a significant region of upward motion (positive values, shaded in green). Equation 10 shows that ωc, is solely related to the climbing flow components (\({V}_{c}\)) of the horizontal wind. The proportion (α in Eq. 11) of \({V}_{c}\) relative to the horizontal wind \({V}_{h}\) at near-surface and 650 hPa height is 66.1% and 53.8%, respectively. This implies that the topography exerts a substantial influence on the horizontal winds in the CEH, with most of the horizontal wind being converted into vertical motion along the terrain gradient. The SNAO-related ωc (from regression analysis) at near-surface and 650 hPa pressure levels (Fig. 3c, d) generally agree with the characteristics of the climatological ωc (Fig. 3a, b). Notably, the proportion of the SNAO-related climbing flow relative to the SNAO-related horizontal wind was even higher than that of climatological mean. This indicates that SNAO-induced circulation is more efficient in converting horizontal wind into the climbing wind in the CEH in Phase 2. This efficiency is related to the stable southwesterly winds spanning 850 hPa to 500 hPa levels above the region to the south of the CEH (not shown).

Climatological fields of topographic-induced vertical velocity (ωc) over the CEH in summer for Phase 2: (a) near-surface (10 m) and (b) 650 hPa. Panels (c) and (d) display the regressions of 10 m and 650 hPa ωc, respectively, onto the SNAO index. Here, α represents the ratio of the climbing flow component relative to the horizontal wind speed.

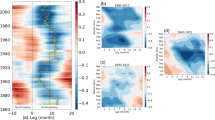

To further validate our findings, we used a topography-removal simulation from the Global Monsoons Model Intercomparison Project (GMMIP) of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). As shown in Fig. 4a, the Tier-1 experiments, referred to as the control (Ctrl) experiments and following the standard AMIP configuration (see Methods), effectively captured the SNAO-induced increase in precipitation anomalies over the CEH in Phase 2. Additionally, the Ctrl experiments in Fig. 4b captured the 500 hPa anticyclone to the south of CEH as well as the associated upward motion within the CEH. Figure 4c further demonstrated that the Ctrl experiments reproduced both the meridional circulation and ωc patterns in Phase 2. These results demonstrate that the model in the Ctrl experiments is a reliable tool for investigating the complex interactions among climate variability, atmospheric circulation, and topography in shaping the year-to-year variations in CEH summer precipitation.

a Precipitation distribution output from Ctrl experiments. b Regression of the 500 hPa horizontal wind (Vh; m/s) and vertical velocity (ω; shaded; Pa/s) against the SNAO index in the Ctrl experiments. c Meridionally averaged (20–35°N, 76.5–97.0°E, as indicated in (b)) zonal-height cross section showing regressions of meridional wind, vertical velocity (ω), and topographically induced vertical motion (ωc). Vectors show the combined fields of meridional wind (m/s) and ω (-1×10⁻² Pa/s), shading represents ω (10⁻¹ Pa/s), and contours indicate ωc (0.001, 0.005, 0.009, and 0.01; 10⁻¹ m/s). d–f Same as (a–c) but for the NoT experiments. In (e), yellow arrows mark the circulation linked to the cyclone west of the CEH, green arrows highlight the anticyclonic flow south of the CEH, and purple arrows indicate the northerly cold and dry flow. “C” and “A” denote cyclone and anticyclone centers, respectively. In (f), vectors combine meridional wind (m/s) and ω (–1×10⁻³ Pa/s), shading shows ω (10⁻² Pa/s), and meridional averaging is taken over 20–35°N, 84.0-97.0°E (as shown in panel e). With the removal of the topographic gradient, ωc vanishes in this experiment. Topography is displayed in black shading, and hatched regions exceed the 95% significance level.

Within the Tier-3 setup, referred to as the no-topography (NoT) experiments, was derived from the Ctrl configuration by reducing all CEH elevations above 500 m to 500 m (see Methods). Unlike the Ctrl experiments, the NoT experiments exhibited a dipole-like precipitation distribution in Phase 2 (Fig. 4d), with increased precipitation anomalies in the western CEH (76.5–84.0°E) and reduced anomalies in the central-eastern CEH (84.0–97.0°E). This indicates that removing the topography alters the SNAO-related summer precipitation distribution in the CEH in Phase 2.

The NoT experiments demonstrate that the 500 hPa anticyclone center over northern India shifts northwestward compared to the Ctrl experiments (Figs. 4b, e). Meanwhile, a 500 hPa cyclonic circulation emerges to the west of the CEH (Fig. 4e). The westernmost edge of this cyclonic circulation extends to approximately 40°E (Supplementary Figure 6), while its easternmost edge overlaps with the region of strong upward motion in western CEH, as depicted in Fig. 4e. The cyclone in the west of CEH and the anticyclonic circulations over northwestern India facilitate moisture convergence into the western CEH. The moisture convergence caused by the cyclone and the anticyclone were illustrated by the yellow and green arrows in Fig. 4e. These two circulations give rise to positive specific humidity (Supplementary Fig. 6) and upward motion in the western CEH (Fig. 4e), ultimately leading to increased precipitation over the western CEH.

The northern branch of the 500 hPa anticyclonic circulation over northwestern India in the NoT experiments reached approximately 33°N (indicated by the green arrow in Fig. 4e). This resulted in a shift in the wind pattern over the central CEH (84–87°E). The dominant southwesterly wind field in the central CEH observed by the Ctrl experiments was replaced by northwesterly wind field in the NoT experiments. The southwesterly airflow blowing to the southern slope of the CEH can result in vertical upward motion and moisture convergence, whereas the northwesterly wind plays the opposite role. This change in the wind direction hindered vertical upward motion and moisture convergence in the central CEH. This explains why negative specific humidity and subsidence happened in the central CEH (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 7).

A cyclone occurred northeast of the TP in the NoT experiments. This cyclone did not emerge in the Ctrl experiments. The cyclone caused a strong cold and dry airflow blowing to the eastern CEH (87–97°E) in the NoT experiments (indicated by the purple arrow in Fig. 4e). This flow caused negative specific humidity and subsidence in the eastern CEH. In addition, Fig. 4f shows that the NoT experiments did not reproduce the vertical ascent and the ωc on the windward slopes of central-eastern CEH observed in the Ctrl experiments (Fig. 4c). Instead, it exhibits a predominantly downward airflow, which aligns with the widespread negative precipitation over the CEH.

Accordingly, topographic removal experiments confirmed that, without this topographic mechanical forcing, the observed positive precipitation anomalies disappeared. The findings highlight that the spatial interplay between the circulation anomalies triggered by the SNAO and the Himalayan topography governs the precipitation anomalies observed in Phase 2.

Discussion

This study analyzes the linkage between CEH summer precipitation variability (1985–2019) and large-scale climate signals. ENSO shows a sustained negative association with CEH summer precipitation, whereas the SNAO–CEH precipitation linkage is non-stationary: the 9-year running correlation between the SNAO index and GPCC-based CEH precipitation shows break years in 1994 and 2010, yielding a “weak–strong–weak” evolution.

In Phase 2 (1994–2010), the SNAO–CEH precipitation correlation is strong (Corr = 0.75, p < 0.05) and exceeds the ENSO–CEH correlation (Corr = −0.57, p < 0.05). The SNAO induces an anticyclone in the region to the south of the CEH that channels low-level flow toward the Himalayan foothills; topographic uplift converts the low-level flow into vertical motion and causes precipitation anomalies. A standard AMIP control simulation reproduces these processes, whereas a topography-removal experiment suppresses precipitation in the CEH. This study analyzes AMIP simulations from a single model. The conclusions should therefore be interpreted with this limitation in mind; multi-model confirmation is left for future work.

In Phases 1 (1985–1993) and 3 (2011–2019), the SNAO–CEH precipitation relationship weakens (Corr = 0.15 and −0.31; both p > 0.05). Nevertheless, Supplementary Fig. 5 shows that 500-hPa anticyclones also form in the region to the south of the CEH in Phases 1 and 3. The anticyclone centers in Phases 1 and 3 are displaced southwestward relative to Phase 2. Similarly, Liu, et al.25 showed that Rossby-wave propagation along Eurasia is interdecadally unstable and asymmetric, which modifies SNAO-related teleconnection pathways and their strength. These circulation adjustments likely render the SNAO–TP precipitation linkage non-stationary. Accordingly, with orography held fixed, we speculate that quasi-decadal meridional shifts of the anomalous anticyclone to the south of the CEH may contribute to the non-stationary SNAO–CEH precipitation linkage.

To quantify boundary uncertainty, we applied a ± 3-yr boundary-jitter around each breakpoint—early (1991, 2007), baseline (1994, 2010), and late (1997, 2013)—and recomputed SNAO-related precipitation and 500-hPa circulation diagnostics. The two alternative schemes preserve the meridional displacement of the SNAO-induced anticyclone south of the CEH, and the spatial pattern correlations of precipitation anomalies with the baseline segmentation are high and significant (p < 0.01): baseline vs late = 0.64/0.99/0.97; baseline vs early = 0.74/0.98/0.82 (three phases). Hence, the inferred inter-phase differences are insensitive to ±3-yr perturbations of the boundaries.

The Silk Road Pattern (SRP) is an eastward-propagating wave mode along the Asian westerly jet34,35. In summer, it emerges as the leading mode of upper-tropospheric meridional wind anomalies over midlatitude Eurasia36,37. Previous studies suggest that the SNAO influences downstream regions, including South Asia38 and the Tibetan Plateau (TP)39, mainly through the SRP39,40,41,42. Without this “SRP conveyor belt,” the downstream influence of the NAO tends to dissipate near Europe, making it difficult to further trigger strong mid– to high–latitude circulation anomalies that could modulate precipitation in downstream regions42,43. This leads to a testable hypothesis: the more closely the SNAO-related circulation resembles the SRP typical pattern, the stronger its downstream impacts. Figure 5b, d support this idea. In Phase 2, the SNAO-related 200-hPa meridional wind anomalies (V200) closely match the SRP typical pattern. The SRP typical pattern is defined as the V200 composite difference between SRP-positive-strong and SRP-negative-strong years ( | SRP index | ≥ 1 standard deviation). Within 15°–85°N, 60°W–120°E, the spatial correlation between the Phase-2 SNAO-related wave train (Fig. 5b) and the SRP typical pattern (Fig. 5d) is 0.93 (p < 0.01). By contrast, correlations are only 0.39 and 0.25 in Phases 1 and 3.

Regression of 200-hPa meridional wind (shading; units: m s⁻¹) onto the SNAO index for (a) Phase 1, (b) Phase 2, and (c) Phase 3. d The SRP typical wave train. Black dots denote grid points significant at the 95% confidence level. The yellow solid line denotes the climatological jet axis. Panel d is defined as the V200 composite difference between SRP-positive-strong and SRP-negative-strong years ( | SRP index | ≥ 1 standard deviation).

From 1985–2019, the correlation between the SNAO and SRP indices is 0.64 (p < 0.01). Despite this significant temporal correlation, the SRP teleconnection forced by the SNAO shows clear interdecadal differences: only Phase 2 projects strongly onto the SRP typical pattern. Midlatitude wave trains are strongly constrained by the basic flow44. The SRP has two key features: (1) confinement within the Asian upper-tropospheric westerly jet44, and (2) geographic anchoring44. As shown in Fig. 6a, the 500-hPa anomalous anticyclone to the south of CEH is part of the SRP typical wave train. Its position and extent nearly replicate the Phase-2 feature (Fig. 6b). In contrast, the anticyclones in Phases 1 and 3 are meridionally displaced relative to the SRP typical pattern.

Thus, when the SNAO teleconnection closely matches the SRP typical pattern, the downstream anticyclone over southern CEH couples strongly with local topography, creating a tight SNAO–CEH precipitation linkage. In Phases 1 and 3, weaker projection onto the SRP pattern reduces terrain–circulation coupling, weakening the SNAO–CEH linkage.

Why does the SNAO more effectively excite the SRP typical pattern in Phase 2? Previous work indicates that anomalies near the Asian jet entrance (Mediterranean–Caspian sector) are crucial for SNAO-driven SRP excitation42,45,46,47. The western end of the SRP sits at this jet entrance, serving as a pacemaker for the disturbance. Moreover, Hong, et al.48 showed that when the subtropical jet strengthens over this region, the Rossby wave source anomaly intensifies due to planetary-vorticity stretching, favoring a stronger SRP wave train.

To test this, we computed the 9-year running mean of 200-hPa zonal wind (U200) over the jet entrance (30–45°N, 0–30°E) and compared it with the 9-year running correlation between the SNAO and CEH summer precipitation. The two series are strongly correlated (Corr = 0.95, p < 0.01; Fig. 7). Notably, the U200 running mean shows clear regime shifts in 1994 and 2010 (from −0.36 to 0.02 and from −0.51 to −1.35), which align with the phase divisions. Accordingly, in Phase 2, the U200 running mean is predominantly positive, indicating a stronger jet entrance. In Phase 2, the strengthened and favorably positioned jet provides a more efficient waveguide and enhances barotropic energy conversion, allowing SNAO-generated anomalies to project onto—and amplify—the SRP typical pattern. Accordingly, years with strong anomalies exceeding ±1 standard deviation in either the SNAO or SRP indices account for 41.1% (7/17) of Phase 2, with four years showing concurrent same-sign anomalies. In Phases 1 and 3, the fractions are lower and no concurrent same-sign anomalies appear.

In summary, interdecadal variability of U200 at the Asian jet entrance may be a key background factor that modulates how the SNAO triggers different SRP patterns across phases. This linkage requires further testing with longer records and independent datasets.

Jet variability likely reflects multiple—still debated—drivers. The primary control is the tropics–to–pole meridional temperature gradient (MTG): by thermal-wind balance, a stronger (weaker) MTG favors a stronger (weaker) jet49. Arctic amplification (via sea-ice loss) weakens the MTG50, partly offset by tropical warming through a reduced moist-adiabatic lapse rate51. Weakened tropical Pacific convection can further lower the MTG and enhance jet waviness via embedded Rossby wave trains52, while anthropogenic aerosols (declining over Europe, increasing over South/South-East Asia) modify meridional heating and tend to weaken the Eurasian jet53,54. Recent work shows that the Scandinavian pattern (SCA) in February exerts a lagged influence on the summer jet through a cross-seasonal ocean–atmosphere bridge55. In Fig. 7, February SCA index (source: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/teledoc/scand.shtml) is strongly anti-correlated with subsequent jet-entrance 200-hPa zonal-wind strength on interdecadal timescales (Corr = −0.76, p < 0.01). Mechanistically, a plausible pathway proposed by Lin, et al.55 is that a positive SCA establishes a high-pressure anomaly over northern Europe; the accompanying southeasterlies on its southwestern flank may reduce surface evaporation and promote high-latitude North Atlantic SST warming. Through this sustained oceanic memory, spring–summer air–sea coupling could energize a Rossby wave train emanating from the North Atlantic and arching toward East Asia, which in turn may reorganize the meridional pressure gradient and modulate the strength and path of the Eurasian jet.

Because the SNAO–CEH precipitation linkage is strongest in Phase 2, we present only a Phase-2 schematic of the key mechanism (Fig. 8). In Phases 1 and 3, the linkage is weaker and the mechanism is only speculative, so no schematics are provided. The Rossby-wave propagation in Fig. 8 follows the four anomaly centers that form the Phase-2 wave train in Fig. 5b—originating from the 200-hPa cyclonic anomaly over 30°W–30°E and extending toward the anticyclone to the south of the CEH along a northwest–to–northeast pathway—with SNAO-related wind anomalies and flow features referenced from Fig. 2c, d. Prior idealized schematics of SNAO teleconnections affecting summer precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau or East China are broadly consistent with our results24,26.

The orange ringed arrows labeled C denote the SNAO-induced anomalous cyclone in the upper troposphere. The blue ringed arrows labeled A denote the SNAO-induced anomalous anticyclone in the upper troposphere. The solid purple arrow denotes the Rossby wave propagation. The thick yellow arrows denote the anomalous anticyclone south of the CEH induced by SNAO. This figure is an idealized representation; the SNAO teleconnection in reality is more complex and non-stationary across periods (see Fig. 5a–c).

Supplementary Fig. 8 shows climatological winds and geopotential height at 850 and 500 hPa, together with fields regressed onto the SNAO in Phase 2. A monsoon trough at 850 hPa south of the CEH and a cyclonic system at 500 hPa (Supplementary Fig. 8a) are reorganized in the regressions into anticyclonic circulation (Supplementary Fig. 8b), strengthening southerly/southwesterly transport toward the southern slopes of the CEH and producing positive precipitation anomalies. On this basis, we infer that when the SNAO-related reorganized anticyclone in the region to the south of the CEH shifts farther from the orography, the SNAO–CEH precipitation linkage weakens accordingly.

Supplementary Fig. 4b indicates a sustained negative relationship between the summer Niño-3.4 index and interannual CEH precipitation across the three phases (Corr = −0.49, −0.57, and −0.63; p < 0.05 for Phases 1–3). In Phases 1 and 3, SNAO- and ENSO-related 500-hPa anomalies in the region to the south of the CEH differ (Supplementary Figs. 5a, 5c, 5d, 5f), leading to different precipitation anomalies over the CEH; in Phase 2, the 500-hPa anticyclones induced by SNAO and ENSO are similar, consistent with comparable positive precipitation anomalies (Supplementary Figs. 5b, 5e). Although earlier studies often examined ENSO and the SNAO as separate drivers, more recent work suggests a possible AMO-mediated linkage between them56,57. The impact of this potential connection on CEH summer-precipitation variability remains unclear and complicates prediction.

GPCC includes more quality-controlled rain gauges over the CEH than the 59 gauges used in this study, and—based on station-level point-to-point comparisons against those 59 gauges—GPCC exhibits the smallest errors relative to APHRO, CRU, and ERA5 (see Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). However, the observational records we use are not publicly accessible, which hinders broader integration of precipitation observations and a comprehensive evaluation of gridded precipitation products. Moreover, while APHRO, CRU, and ERA5 all capture a non-stationary SNAO–CEH precipitation linkage, they disagree on the precise onset years of the three phases within 1985–2019. These uncertainties call for denser in situ precipitation measurements in the CEH and a systematic multi-dataset evaluation to better constrain the non-stationary SNAO–CEH linkage.

Methods

Definitions of the climate indices

The NAO index was derived by applying principal component analysis to the leading empirical orthogonal function (EOF) mode of summer 500 hPa geopotential height, based on ERA5 data over the region 25–70°N and 70°W–50°E24,58,59,60. The summer NAO (SNAO) index was then computed as the seasonal mean of this NAO index for June through August24. We define the SRP index as the leading empirical orthogonal function mode of the 200-hPa meridional wind (V200) anomalies over the region 20°–60° N, 0°–150° E42.

Atmospheric moisture budget

Precipitation changes are attributed to variations in evaporation and moisture advection54,61 :

Here, E and P denote evaporation and precipitation, respectively; ω indicates vertical velocity and \({V}_{h}\) denotes horizontal wind; q stands for specific humidity; \({\nabla }_{h}q\) and \({\partial }_{p}q\) indicate the horizontal and vertical moisture gradients, respectively, while δ represents the residual term. Vertical integration is performed from the surface to the tropopause, denoted by angle brackets, and monthly anomalies relative to climatology are indicated by the prime symbol. In Eq. 1, the 2nd and 3rd terms on the right-hand side denote the contributions of horizontal and vertical moisture advection, respectively.

The horizontal and vertical moisture advection components can be further subdivided as follows:

Here, the first term on the right-hand side reflects the thermodynamic contribution associated with specific variations, the second represents the dynamic effect linked to circulation changes, and the final term denotes nonlinear interactions.

Simulations

To systematically elucidate how regional topography interacts with circulation anomalies induced by climate variability and thereby influences summer precipitation over the CEH, this study used topographic sensitivity simulation experiments. The topographic sensitivity simulations were completed by Tier-1 and Tier-3 experiments, using the First Institute of Oceanography Earth System version 2 model (FGOALS-f3-L; variant_id: r1i1p1f1) within the GMMIP. As part of CMIP6, the GMMIP aims to investigate the mechanisms driving monsoon variability and assess its potential future changes. In the experimental setup, the distinction between Tier-1 and Tier-3 lies solely in the treatment of topography. Tier-1, referred to as the control (Ctrl) experiment, follows the standard AMIP configuration, while Tier-3, referred to as the no-topography (NoT) experiment, is derived from the Ctrl run by lowering all elevations above 500 m to 500 m, thereby flattening the Tibetan-Iranian Plateau62. This topography removal in the model avoids the steep topographic gradients caused by artificial mountain cutting. A detailed description of the GMMIP framework, Ctrl and NoT experiments, as well as the perturbation domain, are provided in Song, et al.62 and Zhou, et al.63. Previous model evaluation studies demonstrated that the Ctrl experiments effectively capture the primary features of atmospheric circulation and precipitation over Asia64,65,66. For both Ctrl and NoT experiments, the SNAO index was computed from their respective sea-level pressure outputs.

Diagnosis of encircling and climbing flow

To scientifically diagnose the dynamic lifting effect of terrain on airflow, this study adopts the scheme used by Zhang & Qian67 in numerical experiments on TP dynamics, which divides the lowest-layer horizontal wind (\({V}_{h}\)) in the model into encircling flow (\({V}_{e}\)) and climbing flow (\({V}_{c}\)) components:

\({V}_{e}\) and \({V}_{c}\) are orthogonal to each other, with \({V}_{e}\) being perpendicular to the terrain gradient and \({V}_{c}\) being parallel to the terrain gradient:

where \({z}_{{\rm{s}}}\) represents the topography height, and \(\nabla {z}_{{\rm{s}}}\) denotes the gradient of the topography height (\(\nabla {z}_{s}=\partial {z}_{{\rm{s}}}/\partial {xi}+\partial {z}_{{\rm{s}}}/\partial {yj}\)).

This study mainly focuses on \({V}_{c}\). By combining the above equations, the following can be obtained:

where \({u}_{{\rm{c}}}\) and \({v}_{{\rm{c}}}\) represent the zonal and meridional components of the climbing wind vector \({V}_{c}\) respectively, while \({u}_{h}\) and \({v}_{{\rm{h}}}\) represent the zonal and meridional components of the horizontal wind vector \({V}_{h}\).

The terrain has a certain impact on vertical motion, and \({V}_{{\rm{e}}}\) is perpendicular to the topography height gradient (\({V}_{e}\cdot \nabla {z}_{s}=0\)). Therefore, equations exist for rigid boundary conditions:

where \({\omega }_{{\rm{c}}}\) (m/s) is the vertical velocity induced by topographic mechanical forcing.

\({\omega }_{{\rm{c}}}\) is only related to \({V}_{c}\). To quantitatively describes the extent to which horizontal wind is converted into vertical motion due to topographic mechanical forcing, we define an α index:

Data availability

Monthly precipitation records from 59 rain gauges in the CEH were provided by the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, Government of Nepal (DHM; http://www.dhm.gov.np/). As shown in Supplementary Table 1, stations 1-58 cover the period 1985–2019, while station 59 spans 1994–2019. It is noteworthy that, in this study, all comparisons between gridded precipitation products and the 59 rain gauges were conducted according to the actual observation periods of each rain gauge. Details of the elevation, latitude, and longitude of the 59 rain gauge observation stations are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Eight of these stations are located at altitudes above 2000 m above sea level (asl), including the Pyramid station (station 59 in Supplementary Table 1), which is situated at 5050 m asl. To assess the reliability of gridded products, the rain-gauge data were compared with four widely used precipitation datasets: GPCC (0.5° × 0.5°, 1985–2019; https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.gpcc.html) and CRU (0.5° × 0.5°, 1985–2019; https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/), APHRO (0.25° × 0.25°, 1985–2015; http://aphrodite.st.hirosaki-u.ac.jp/products.html), and ERA5 reanalysis (0.25° × 0.25°, 1985–2019; https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/). In addition, ERA5 atmospheric circulation and vertical velocity fields were employed to investigate the mechanisms driving interannual variations in CEH summer precipitation.

Code availability

All analyses in this study were performed using the NCAR Command Language (NCL). The scripts developed for this work can be obtained from the first author (zhangq@itpcas.ac.cn) upon reasonable request. Rain-gauge observations, owned and distributed by the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, Government of Nepal (DHM), are available upon request from DHM (http://www.dhm.gov.np/).

References

Immerzeel, W. W., Van Beek, L. P. & Bierkens, M. F. Climate change will affect the Asian water towers. Science 328, 1382–1385 (2010).

Palazzi, E., Von Hardenberg, J. & Provenzale, A. Precipitation in the Hindu‐Kush Karakoram Himalaya: observations and future scenarios. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 118, 85–100 (2013).

Qazi, N. Q., Jain, S. K., Thayyen, R. J., Patil, P. R. & Singh, M. K. Hydrology of the Himalayas. In: Himalayan Weather and Climate and their Impact on the Environment. 419–450 (Springer, 2020).

Bolch, T. et al. The state and fate of Himalayan glaciers. Science 336, 310–314 (2012).

Barnett, T. P., Adam, J. C. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions. Nature 438, 303–309 (2005).

Wester, P., Mishra, A., Mukherji, A. & Shrestha, A. B. The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People (Springer Nature, 2019).

Scherler, D., Bookhagen, B. & Strecker, M. R. Spatially variable response of Himalayan glaciers to climate change affected by debris cover. Nat. Geosci. 4, 156–159 (2011).

Kuang, X. & Jiao, J. J. Review on climate change on the Tibetan Plateau during the last half century. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 121, 3979–4007 (2016).

You, Q. et al. Observed climatology and trend in relative humidity in the central and eastern Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 120, 3610–3621 (2015).

Yadav, M., Dimri, A., Mal, S. & Maharana, P. Elevation-dependent precipitation in the Indian Himalayan Region. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 155, 815–828 (2024).

Zhang, W., Zhou, T. & Zhang, L. Wetting and greening Tibetan Plateau in early summer in recent decades. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 122, 5808–5822 (2017).

Dong, W. et al. Summer rainfall over the southwestern Tibetan Plateau controlled by deep convection over the Indian subcontinent. Nat. Commun. 7, 10925 (2016).

Turner, A. G. & Annamalai, H. Climate change and the South Asian summer monsoon. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 587–595 (2012).

Mall, R. K., Gupta, A., Singh, R., Singh, R. S. & Rathore, L. Water resources and climate change: An Indian perspective. Curr. Sci., 90, 1610–1626 (2006).

Sharma, S., Hamal, K., Khadka, N. & Joshi, B. B. Dominant pattern of year-to-year variability of summer precipitation in Nepal during 1987–2015. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 142, 1071–1084 (2020).

Bookhagen, B. Appearance of extreme monsoonal rainfall events and their impact on erosion in the Himalaya. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 1, 37–50 (2010).

Jiang, X. et al. Impacts of ENSO and IOD on snow depth over the Tibetan Plateau: Roles of convections over the western North Pacific and Indian Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 124, 11961–11975 (2019).

Zhou, C., Zhao, P. & Chen, J. The interdecadal change of summer water vapor over the Tibetan Plateau and associated mechanisms. J. Clim. 32, 4103–4119 (2019).

Hu, S., Zhou, T. & Wu, B. Impact of developing ENSO on Tibetan Plateau summer rainfall. J. Clim. 34, 3385–3400 (2021).

Saini, R. & Attada, R. Analysis of Himalayan summer monsoon rainfall characteristics using Indian High‐Resolution Regional Reanalysis. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 4286–4307 (2023).

Lei, Y. et al. Extreme lake level changes on the Tibetan Plateau associated with the 2015/2016 El Niño. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5889–5898 (2019).

Zhang, T., Jiang, X., Yang, S., Chen, J. & Li, Z. A predictable prospect of the South Asian summer monsoon. Nat. Commun. 13, 7080 (2022).

Rajeevan, M. & Pai, D. On the El Niño‐Indian monsoon predictive relationships. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, (2007).

Hu, S., Zhou, T. & Wu, B. The physical processes dominating the impact of the summer North Atlantic Oscillation on the eastern Tibetan Plateau summer rainfall. J. Clim. 35, 7677–7690 (2022).

Liu, Y., Chen, H. & Hu, X. The unstable relationship between the precipitation dipole pattern in the Tibetan Plateau and summer NAO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091941 (2021).

Wang, Z., Yang, S., Lau, N.-C. & Duan, A. Teleconnection between summer NAO and East China rainfall variations: A bridge effect of the Tibetan Plateau. J. Clim. 31, 6433–6444 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Impact of the North Atlantic Oscillation on the Dipole Oscillation of summer precipitation over the central and eastern Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Climatol. 35, (2015).

Liu, X. & Yin, Z.-Y. Spatial and temporal variation of summer precipitation over the eastern Tibetan Plateau and the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Clim. 14, 2896–2909 (2001).

Smith, R. B. Advances in geophysics Vol. 21 87–230 (Elsevier, 1979).

Schneider, U. et al. GPCC’s new land surface precipitation climatology based on quality-controlled in situ data and its role in quantifying the global water cycle. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 115, 15–40 (2014).

Mishra, B. et al. Gridded precipitation products on the Hindu Kush-Himalaya: Performance and accuracy of seven precipitation products. PLoS Water 2, e0000145 (2023).

Kanda, N., Negi, H., Rishi, M. S. & Kumar, A. Performance of various gridded temperature and precipitation datasets over Northwest Himalayan Region. Environ. Res. Commun. 2, 085002 (2020).

Dahri, Z. H. et al. Spatio‐temporal evaluation of gridded precipitation products for the high‐altitude Indus basin. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 4283–4306 (2021).

Lu, R.-Y., Oh, J.-H. & Kim, B.-J. A teleconnection pattern in upper-level meridional wind over the North African and Eurasian continent in summer. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 54, 44–55 (2002).

Hong, X. & Lu, R. The meridional displacement of the summer Asian jet, Silk Road pattern, and tropical SST anomalies. J. Clim. 29, 3753–3766 (2016).

Sato, N. & Takahashi, M. Dynamical processes related to the appearance of quasi-stationary waves on the subtropical jet in the midsummer Northern Hemisphere. J. Clim. 19, 1531–1544 (2006).

Wang, L., Xu, P., Chen, W. & Liu, Y. Interdecadal variations of the Silk Road pattern. J. Clim. 30, 9915–9932 (2017).

Goswami, B. N., Madhusoodanan, M., Neema, C. & Sengupta, D. A physical mechanism for North Atlantic SST influence on the Indian summer monsoon. Geophysi. Res. Lett. 33, (2006).

Shang, W., Duan, K., Li, S., Ren, X. & Huang, B. Simulation of the dipole pattern of summer precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau by CMIP6 models. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 014047 (2021).

Bollasina, M. A. & Messori, G. On the link between the subseasonal evolution of the North Atlantic Oscillation and East Asian climate. Clim. Dyn. 51, 3537–3557 (2018).

Du, Y., Zhang, J., Zhao, S. & Chen, H. Impact of the eastward shift in the negative‐phase NAO on extreme drought over northern China in summer. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 125, e2019JD032019 (2020).

Hong, X., Lu, R., Chen, S. & Li, S. The relationship between the North Atlantic Oscillation and the Silk Road pattern in summer. J. Clim. 35, 6691–6702 (2022).

Li, X., Lu, R., Greatbatch, R. J., Li, G. & Hong, X. Maintenance mechanism for the teleconnection pattern over the high latitudes of the Eurasian continent in summer. J. Clim. 33, 1017–1030 (2020).

Hoskins, B. J. & Ambrizzi, T. Rossby wave propagation on a realistic longitudinally varying flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 50, 1661–1671 (1993).

Hong, X., Lu, R. & Li, S. Differences in the Silk Road pattern and its relationship to the North Atlantic Oscillation between early and late summers. J. Clim. 31, 9283–9292 (2018).

Enomoto, T., Hoskins, B. J. & Matsuda, Y. The formation mechanism of the Bonin high in August. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc.: A J. Atmos. Sci., Appl. Meteorol. Phys. Oceanogr. 129, 157–178 (2003).

Chen, G. & Huang, R. Excitation mechanisms of the teleconnection patterns affecting the July precipitation in Northwest China. J. Clim. 25, 7834–7851 (2012).

Hong, X., Lu, R. & Li, S. Asymmetric relationship between the meridional displacement of the Asian westerly jet and the Silk Road pattern. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 35, 389–396 (2018).

Barnes, E. A. & Screen, J. A. The impact of Arctic warming on the midlatitude jet‐stream: Can it? Has it? Will it? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Change 6, 277–286 (2015).

Coumou, D., Di Capua, G., Vavrus, S., Wang, L. & Wang, S. The influence of Arctic amplification on mid-latitude summer circulation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2959 (2018).

Blackport, R. & Screen, J. A. Insignificant effect of Arctic amplification on the amplitude of midlatitude atmospheric waves. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2880 (2020).

Sun, X. et al. Enhanced jet stream waviness induced by suppressed tropical Pacific convection during boreal summer. Nat. Commun. 13, 1288 (2022).

Dong, B., Sutton, R. T., Shaffrey, L. & Harvey, B. Recent decadal weakening of the summer Eurasian westerly jet attributable to anthropogenic aerosol emissions. Nat. Commun. 13, 1148 (2022).

Jiang, J. et al. Precipitation regime changes in High Mountain Asia driven by cleaner air. Nature 623, 544–549 (2023).

Lin, L. et al. Atlantic origin of the increasing Asian westerly jet interannual variability. Nat. Commun. 15, 2155 (2024).

Zhang, W., Mei, X., Geng, X., Turner, A. G. & Jin, F.-F. A nonstationary ENSO–NAO relationship due to AMO modulation. J. Clim. 32, 33–43 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. Impact of ENSO longitudinal position on teleconnections to the NAO. Clim. Dyn. 52, 257–274 (2019).

Folland, C. K. et al. The summer North Atlantic Oscillation: past, present, and future. J. Clim. 22, 1082–1103 (2009).

Jia, X. J., Derome, J. & Lin, H. Comparison of the life cycles of the NAO using different definitions. J. Clim. 20, 5992–6011 (2007).

Liu, Q., Bader, J., Jungclaus, J. H. & Matei, D. More extreme summertime North Atlantic Oscillation under climate change. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 474 (2025).

Seager, R., Naik, N. & Vecchi, G. A. Thermodynamic and dynamic mechanisms for large-scale changes in the hydrological cycle in response to global warming. J. Clim. 23, 4651–4668 (2010).

Song, Y. et al. FIO-ESM v2. 0 outputs for the CMIP6 global monsoons model intercomparison project experiments. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 37, 1045–1056 (2020).

Zhou, T. et al. GMMIP (v1. 0) contribution to CMIP6: global monsoons model inter-comparison project. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3589–3604 (2016).

Sun, H. & Liu, X. Impacts of dynamic and thermal forcing by the Tibetan Plateau on the precipitation distribution in the Asian arid and monsoon regions. Clim. Dyn. 56, 2339–2358 (2021).

Luo, H., Wang, Z., Yang, S. & Hua, W. Revisiting the impact of Asian large-scale orography on the summer precipitation in Northwest China and surrounding arid and semi-arid regions. Clim. Dyn. 60, 33–46 (2023).

Bao, Y., Song, Z. & Qiao, F. FIO‐ESM version 2.0: Model description and evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. -Oceans 125, e2019JC016036 (2020).

Zhang, Y. & Qian, Y. Numerical studies on the effects of the critical height of Qinghai-Xizang Plateau uplift on the atmosphere. Acta Meteorologica Sin. 57, 157–167 (1999).

Liu, J. et al. Name and scale matter: Clarifying the geography of Tibetan Plateau and adjacent mountain regions. Glob. Planet. Change 215, 103893 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U2442213) and the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) Program (Grant No. 2019QZKK0105). Q.Z. gratefully acknowledges additional funding from the China Scholarship Council (Grant No. 202504910249). We also appreciate the constructive feedback provided by the editor and two anonymous reviewers, which greatly improved the quality of this paper. We are grateful to Professor Peiqiang Xu for suggesting potential mechanisms for the nonstationary SNAO–CEH precipitation linkage.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C. and Y.Ma. conceptualized and supervised the study. Q.Z. and X.C. organized materials, assembled datasets, and carried out the analyses. S.S. contributed rain gauge observations. The first draft was prepared by Q.Z. and subsequently revised with contributions from X.C., Y.Ma., D.C., and S.H. All authors discussed the results, contributed to the writing, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Chen, X., Ma, Y. et al. Non-stationary influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation on summer precipitation in the Central-Eastern Himalayas. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 392 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01268-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01268-6