Abstract

Neonicotinoid insecticides (NNs), widely deployed in agriculture, are now recognized as pervasive environmental contaminants. This study reveals that the photochemical degradation of nitenpyram (NPM), a prominent NN, in the aqueous phase generates substantial fluxes of gaseous reactive nitrogen species, including nitrous acid (HONO) and nitrogen oxides (NOx = NO + NO2). Reaction pathways, elucidated through aqueous and gas-phase product analysis and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, demonstrate that HONO, NO2, and NO arise directly from the excited triplet state of NPM. Global modeling, parameterized by laboratory-derived kinetics, estimates annual emissions of 71.2 Gg N yr−1 (NOx) and 40.7 Gg N yr−1 (HONO) from NPM photodegradation. These emissions elevate boundary-layer concentrations of HONO, ozone (O3), and OH by 0.54%, 0.11%, and 0.20%, respectively, globally. Our findings uncover a significant, yet overlooked, source of reactive nitrogen that perturbs global nitrogen cycling, amplifies atmospheric oxidative capacity, and influences climate dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The escalating global deployment of neonicotinoid insecticides (NNs), which dominate >25% of the worldwide pesticide market, has intensified concerns over their ecological persistence and toxicity to non-target organisms1,2,3. Widespread environmental dissemination of NNs detected across aquatic systems, soils, vegetation, and atmospheric particulates4,5,6,7,8 underscores their potential for bioaccumulation and ecosystem disruption9. Nitenpyram (NPM), a nitroalkene-structured neonicotinoid [(R₁N)(R₂N)C = CHNO₂], exemplifies this class, sharing structural patterns with emerging contaminants like nizatidine and ranitidine10. Characterized by low volatility (<0.002 mPa at 25 °C) and extended environmental half-lives6,11, NNs accumulate in aquatic matrices at alarming concentrations, surpassing legacy organophosphate insecticides in some regions (e.g., 44.1 µg L-1 in Texas lake water12). Global surface waters contain NPM at mean levels of 88.1 ± 27.1 ng L-1, peaking at 672.9 ng L-113. While prior research has focused on NN photodegradation kinetics14,15,16 and human health risks17, critical gaps persist in understanding their atmospheric chemical evolution, particularly the generation of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) that drive atmospheric oxidation.

Photolytic degradation of NNs, mediated by sunlight or oxidants like ozone (O₃), alters their environmental fate and toxicity profiles14,15,16,17,18. Recent work revealed that gas-phase O₃ reactions with NPM yield nitrous acid (HONO)10, a pivotal precursor to hydroxyl radicals (•OH) that govern secondary pollutant formation19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. However, quantitative assessments of gaseous RNS emissions from NN photochemistry, especially under environmentally relevant aqueous-phase conditions remain absent, hindering accurate modeling of atmospheric nitrogen cycling and oxidative capacity.

While recent work has demonstrated that the presence of soluble iron ions (Fe3+) can significantly enhance the photochemical production of HONO and NOx from NPM through catalytic redox cycling27, the inherent capacity of NPM itself to generate these reactive nitrogen species via direct photolysis remains unquantified (Table S1). Furthermore, the potential impact of this direct photochemical source on the global atmospheric nitrogen cycle and oxidative capacity has not been evaluated.

Here, we present the first direct experimental evidence of gaseous HONO and NOx (NO + NO₂) production during aqueous phase photodegradation of NPM, a representative NN. By integrating laboratory kinetics, pH-dependent photolysis studies, and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, we elucidate the mechanistic pathways driving RNS formation, including energy barriers associated with NPM’s excited triplet state. A global 3-D chemical transport model (GEOS-Chem), parameterized with derived photoformation rates (JNPM→HONO and JNPM→NOx), quantifies the atmospheric impact of NPM-derived HONO (40.7 Gg N yr-1) and NOx (71.2 Gg N yr-1). These fluxes elevate boundary-layer HONO, O₃, and OH concentrations by 0.54%, 0.11%, and 0.20%, respectively, with cascading effects on methane oxidation (lifetime reduced by 0.1%). Our findings unveil NN photochemistry as a previously unrecognized source of atmospheric RNS, challenging current nitrogen cycle paradigms and necessitating integration into Earth system models to refine projections of air quality and climate feedbacks.

Results and Discussion

Production of HONO and NOx

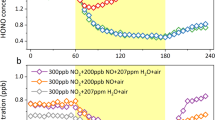

Time-resolved measurements of HONO, NO, and NO₂ production during aqueous-phase photochemical degradation of NPM are presented in Fig. 1A and Figure S1. Under dark conditions, HONO and NOx remained undetectable (<0.4 ppb, detection limit of the NOx analyzer; Figure S2). Upon irradiation, NO surged to 33 ppb within 90 min before stabilizing and gradually declining to 15 ppb over 6 h (Fig. 1A). In contrast, NO2 exhibited a monotonic rise, reaching 130.0 ± 0.8 ppb after 6 h, with no evidence of plateauing. HONO concentrations, quantified via differential denuder measurements (Methods), increased from 8.9 ± 1.7 ppb at 20 min to 61.8 ± 0.6 ppb after 190 min of irradiation, underscoring light-driven kinetics.

A Temporal profiles of NO (black), NO₂ (purple), and HONO (yellow) during NPM photolysis. HONO concentrations derive from denuder-based differential measurements. B Photolysis frequencies (JNPM→HONO, JNPM→NO₂) as functions of irradiation time. Experimental conditions: irradiance = 169.4 W m⁻² (300–400 nm), T = 298 K.

Photoformation rates (JNPM→HONO and JNPM→NOx), calculated using Eq. 3 and Eq. 4 (Methods), reveal dynamic production pathways (Fig. 1B). JNPM→HONO increased tenfold, from (5.36 ± 1.05) × 10⁻⁸ s⁻¹ at 20 min to (5.55 ± 0.07) × 10⁻⁷ s⁻¹ at 190 min, indicative of accelerating HONO generation under prolonged light exposure. Conversely, JNPM→NO₂ showed a more modest rise, from (7.72 ± 0.50) × 10-8 s-1 to (2.05 ± 0.40) × 10-7 s-1, while JNPM→NO [(1.56 ± 0.15) × 10-7 s-1 to (2.33 ± 0.04) × 10-7 s-1] remained stable in comparison to JNPM→HONO and JNPM→NO2. These results demonstrate that aqueous-phase NPM photolysis is a potent source of HONO and NOx, with HONO formation dominating at extended irradiation times.

The pronounced HONO yields observed here coupled with sustained NOx production suggest that neonicotinoid photochemistry may represent a previously unquantified source of reactive nitrogen in sunlit aqueous environments. This mechanism could reconcile discrepancies in atmospheric HONO and NOx budgets, particularly in regions with high agricultural pesticide use.

Effect of pH on NPM photochemical degradation

The photochemical fate of organic pollutants in aquatic systems is critically modulated by pH, which governs speciation and reactivity28,29. For NPM, photodegradation efficiency remained largely pH-insensitive, with 50% degradation at pH 4 declining marginally to 43% at pH 10 (Fig. 2). Strikingly, photoformation rates (JNPM→HONO and JNPM→NOx) exhibited a pronounced inverse relationship with pH, increasing by factors of 3–5 under acidic conditions (pH 4–7) compared to alkaline environments (pH 9–10) (Fig. 2). This trend aligns with the pH-dependent speciation of HONO: at pH > pKa(HONO) = 3.2, deprotonation favors aqueous NO2- retention (R1), whereas acidic conditions promote volatile HONO partitioning into the gas phase30,31,32. Subsequent HONO-to-NOx conversion via heterogeneous reaction (R2) further amplifies NO₂ and NO emissions at lower pH (pH≤7)32,33.

The investigation of the pH change during the photoreaction of NPM was also performed. The results obtained showed that the initial pH 7.5 of the NPM solution decreased to pH 5 after 120 min light irradiation. Figure S3 shows the in situ production of acidic byproducts (e.g., HNO3) during photolysis, creating a feedback loop that sustains HONO and NOx yields. Kinetic analyses revealed pH-independent first-order degradation of NPM (Table S2, Figure S4), with rate constants (k) ranging narrowly from (9.02 ± 0.05) × 10-5 s-1 (pH 9) to (9.77 ± 0.12) × 10-5 s-1 (pH 5) and consistent half-lives (~119–128 min; R² = 0.98–0.99). These results underscore that pH primarily regulates nitrogen speciation and volatilization, not degradation kinetics, driving HONO and NOx fluxes (Figures S5-S6). In short, pH has small effect on the photodegradation kinetics and UV/vis spectrum of NPM (Figure S7), but it affects HONO and NOx formation by influencing the interconversion between nitrogen species through R1 and R2. The inverse pH dependence of HONO yields (Fig. 2) creates a self-sustaining loop in acidified waters (pH <7) as follows: NN photolysis → HNO3 byproducts → further acidification → enhanced HONO volatilization (R1–R2).

This pH-mediated control over reactive nitrogen partitioning highlights a critical mechanism by which neonicotinoids influence atmospheric chemistry. Acidic aqueous environments which are common in agricultural runoff or urban aerosols enhance HONO and NOx emissions, thereby amplifying regional oxidative capacity and secondary pollutant formation. Our findings resolve a key uncertainty in atmospheric models, demonstrating that NN photochemistry contributes disproportionally to reactive nitrogen budgets in pH-sensitive environments.

Elucidating Reactive Nitrogen Formation Pathways via Aqueous-Phase Photoproduct Analysis

To unravel the mechanistic origins of HONO and NOx generation during NPM photolysis, we identified aqueous-phase degradation products using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Four major intermediates (m/z 212, 224, 240, and 242; Table S3) were resolved (Figures S8–S10), enabling reconstruction of the photochemical cascade (Fig. 3).

Pathway 1 is related to NO-driven cascade. UV excitation induces isomerization of NPM’s nitro (-NO2) group to an excited nitrite (-O-NO), forming the triplet-state intermediate IM134,35. Homolytic cleavage of IM1 releases gaseous NO, leaving a resonance-stabilized alkoxy radical (IM2). Gas-phase NO accumulation (Figure S1) aligns with its dual role as a product and reactant, attacking IM2 to yield nitroso aldehyde (IM3). Subsequent decomposition of IM3 produces imine aldehyde (Compound B) via HNO loss or oxime (IM4) through CO elimination. IM4 further degrades to HNO (precursor to N2O36,37,38,39) and imine A (Compound A), corroborating prior observations of NN-derived nitrosation pathways34.

Pathway 2 describes the NO2 generation. C–O bond cleavage in IM1 generates NO₂ and alkyl radical IM5, consistent with NN photochemistry40 and alkyl nitrate photolysis41. IM5 reacts with dissolved O₂, forming aldehyde B and alcohol C (Compounds B and C)42,43, detected here as stable end products.

Pathways 3–4 explain HONO production. The anomalously high HONO fluxes arise from two synergistic routes, (1) water molecules quench the excited triplet state of NPM (IM1), yielding HONO and Compound C44, (2) IM1 undergoes nitro-to-nitrito isomerization, producing imine D (Compound D) and releasing HONO35.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations (detailed below) confirm energetically feasible pathways for HONO and NOx formation, with reaction barriers consistent with experimental kinetics.

This multi-pathway framework resolves the dual role of NPM photolysis as a source of both gas-phase reactive nitrogen species (HONO, NOx) and stable aqueous metabolites. The coexistence of NO-driven radical propagation and pH-modulated HONO partitioning (discussed earlier) underscores the complexity of NN photochemistry in mediating atmospheric oxidant budgets.

DFT Theoretical Calculations

Density functional theory calculations elucidate the photochemical pathways governing HONO and NOx formation during aqueous NPM degradation. Figure 4A delineates the excitation cascade: under UV-A irradiation (300<λ < 400 nm), NPM transitions from the ground state (S0) to the first excited singlet state (S1), followed by intersystem crossing to the triplet state (T1). In T1, the nitro (-NO2) group isomerizes to a nitrito (-ONO) configuration (IM1), releasing 38.05 kcal/mol.

HONO generation proceeds via two endothermic pathways: reaction of IM1 with water yields ketone C (ΔH = 7.37 kcal/mol; ΔG = 17.06 kcal/mol), while nitro-to-nitrito rearrangement forms imine D (ΔH = 3.45 kcal/mol; ΔG = 13.14 kcal/mol) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, NO production is favored kinetically, with a lower energy barrier (3.69 kcal/molvs. 7.37-17.06 kcal/mol for HONO) and exothermicity (−6.00 kcal/mol). This aligns with experimental NO accumulation (Figure S1) and its subsequent depletion via IM2 → IM3 conversion (barrier: 12.45 kcal/mol). IM3 degradation further generates imine aldehyde B (ΔG = 3.23 kcal/mol) and imine A (ΔG = 11.07 kcal/mol), accompanied by transient HNO (precursor to N2O36,37,38,39) and CO release.

C–O bond cleavage in IM1 drives NO₂ formation (Fig. 4B), with a prohibitive energy barrier of 66.41 kcal/mol, identifying this step as rate-limiting. The resultant alkyl radical (IM5) reacts with dissolved O2 and H2O, producing peroxyl (•OOH) and •OH radicals detected via electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR; Figure S11). These radicals propagate NPM degradation via C–H bond abstraction, consistent with the •OH role in secondary oxidation42,43.

While aqueous NO3⁻/NO2⁻ photolysis generates trace HONO and NO2 (quantum yields: ≤0.01540,45), their contributions under NPM photolysis conditions are negligible (Figures S12, S13). This confirms that it is not nitrate byproducts but NPM itself that drives the observed RNS fluxes (Fig. 5).

Molecular configurations of intermediates are detailed in Figure S14.

Collectively, DFT and experimental data resolve NPM photolysis as a direct source of atmospheric HONO and NOx, mediated by triplet-state reactivity and pH-modulated speciation. These pathways amplify oxidative capacity in sunlit aqueous environments, with implications for regional air quality and global nitrogen cycling.

Estimation of Global HONO and NOx Fluxes and their Impacts on Air Quality

The pervasive environmental presence of NPM and its photochemical generation of HONO and NOx identify it as a previously unrecognized source of reactive nitrogen (Nr) with implications for atmospheric oxidation and climate. To quantify these effects, we integrate laboratory-derived kinetics into a global modeling framework, addressing a critical gap in current chemical transport models that omit NN-derived Nr.

Here, we start by examining the relationship between HONO and NOx formation and light intensity at different NPM concentrations, using experimental kinetic data with stepwise linear regression fitting (Figure S15 and S16). The experiments show that, at a fixed NPM concentration level, HONO and NOx (mainly NO2) fluxes increase linearly with light density (Figure S17 and S18), (R2 > 0.98) Such robust linear relationships between productions and light density hold for a broad range of NPM concentrations, 0.005–0.5 mg ml-1.

Then we estimated the global distributions of the NOx and HONO fluxes produced by NPM photochemistry, based on the abovementioned observation-constrained dependence of NOx and HONO fluxes on light density. A key while challenging step for this process is to define environmental NNs concentrations. In a base scenario, we assume an average NPMs concentration of 100 µg L-1 over agricultural areas46, 10 µg L-1 over other continental land, and 1 µg L-1 over oceans, which are 2-4 orders of magnitude lower than the lowest experimental concentrations (0.05 mg ml-1). Global surface waters contain NPM at mean levels of 88.1 ± 27.1 ng L-1, peaking at 672.9 ng L-113. Large-scale use of NNs started in 2004, and the reported concentrations of NNs ranged from several ng L-1 to hundreds of µg L-112, with the highest concentration of imidacloprid (320 µg L-1) measured in 2005 near Noordwijkerhout47. The assumed values of environmental NPM concentrations used in the base scenario are consistent with the reported NPM concentrations in literature. To assess uncertainties in the assumed environmental NPMs concentrations affecting flux estimation, we also considered four additional scenarios based on the upper and lower bounds of values documented in the literature (Table S4). Next, we consider the dependence of NOx and HONO fluxes produced by NPM photochemistry on the spatiotemporal distributions of light density. This is done by using the downward solar radiation data as a metric for light density from the gridded and hourly downward solar radiation from the Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Application version 2 (MERRA-2) assimilated meteorological fields at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.625. In this way, we can derive the hourly gridded NOx and HONO fluxes produced by NPM photochemistry across the globe. More details are provided in the Text S6.

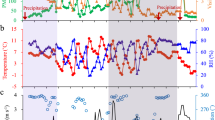

Figure 6A, B shows the spatial distributions of HONO and NOx fluxes produced from NPM photochemistry in the base scenario for the year 2017. We found that globally produced HONO and NOx fluxes from NPM photochemistry are 71.2 and 40.7 Gg N year-1, respectively. These productions only account for 0.3% of the anthropogenic fossil fuel emissions of NOx in the year 2017 (36.2 Tg N, from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS) inventory), and about 1.3% of the soil emissions (8.6 Tg N year-148) (Figure S20). More than half of the emissions are released over agricultural areas with hot spots concentrated in China, India, Central Africa, and South America. In terms of the relative emissions contributions, the HONO and NOx fluxes produced from NPM photochemistry contributed the largest over the oceans, because of the sparsity of other direct Nr sources except for shipping emissions. Assuming different environmental NPMs concentrations yields a wide range of global HONO and NOx fluxes of 6.7–120.8 and 3.8–68.8 Gg N year-1, respectively (Table S4).

A, B shows the emissions for HONO and NOx, respectively. Emissions are estimated based on equation S1 and reanalysis data of downward solar radiation. Global total emissions are shown inset. C, D shows the relative change of tropospheric HONO and ozone due to NPM emissions, estimated by GEOS-Chem global chemical transport model in two scenarios with and without NPM emissions. Figure S19 shows the change of HONO and ozone in absolute values.

As a next step, we estimated the impacts of HONO and NOx production by NPM photochemistry on global tropospheric chemistry, by applying the GEOS-Chem three-dimensional chemical transport model with and without accounting for the Nr fluxes from the NPM chemistry. The results show that in the base scenario, the NPM photochemistry increases tropospheric HONO burden by 0.4% and mean concentrations in the boundary layer by 0.54%, with larger relative enhancement over source regions (such as the North America, South America, and Central Africa) and the Southern Oceans where Nr emissions from other sources (e.g. fossil fuel and soil) are sparse (Fig. 6c). The contributions are larger in austral summer due to higher solar radiation (Figure S21). These additional Nr sources elevate global tropospheric ozone burden and OH column-weighed concentrations by 0.05% and 0.07% (Fig. 6d), respectively. These effects intensify twofold within the boundary layer, with ozone and •OH concentrations increasing by 0.11% and 0.20%, respectively, and the peak gridded enhancement of 104.3% and 13.8%. The increase in global OH concentration further reduces the chemical lifetime of methane against •OH oxidation by 0.1%, representing an extra small sink of this potent greenhouse gas. Sensitivity simulations show that these chemical impacts are mostly linear with changes in environmental NPM concentrations. The contributions of HONO and NOx production by NPM photochemistry to HONO, ozone, and •OH concentrations in the boundary layer can be up to 0.92%, 0.15%, and 0.27% in the scenario with the maximal assumed values for environmental NPM concentrations, higher than the impacts estimated in the base scenario (0.54%, 0.11%, 0.20%).

Our findings identify neonicotinoid photochemistry as a ubiquitous Nr source, particularly in the aqueous phase where NN concentrations are elevated. For example, in regions with intensive NN use (e.g., >100 µg L-1 in water)13, NN-derived HONO can contribute more than 5% of total daytime sources (Fig. 6c), rivaling soil nitrite emissions30. This is critical because HONO photolysis contributes up to 60% of morning OH in croplands24, accelerating oxidation of VOCs and methane. Moreover, NN-derived NOx elevates boundary-layer O3 by 0.11% globally but 0.5–1.2% in farming hotspots (e.g., North China Plain), exacerbating crop damage. The 0.1% reduction in CH4 lifetime (via NN-driven OH increases) translates to 0.02 W m-2 radiative forcing which is equivalent to ca. 10% of N2O’s annual growth impact49. Given shared nitroalkene moieties among NNs (e.g., imidacloprid), their collective photolysis could triple global fluxes40. NN-laden household dust may photolyze on sunlit windows, elevating indoor HONO21a risk factor for respiratory disease.

This mechanism, absent in current climate models, reconciles discrepancies in atmospheric HONO and NOx budgets and amplifies oxidative capacity in both polluted and remote regions. Indoor NN applications may further exacerbate HONO exposure, warranting urgent integration of NN-derived chemistry into Earth system models.

By bridging laboratory kinetics, quantum mechanical insights, and global modeling, this work highlights the necessity of regulating NNs usage to mitigate secondary pollution and climate feedbacks.

Methods

Sample

The NPM solution was prepared before each experiment by dissolving 25 mg of solid NPM (Aladdin, China) into 50 mL of ultrapure water implying that the corresponded concentration was 0.5 mg mL-1. The physical-chemical parameters of NPM can be seen in the Table S5.

Experimental Setup

The circular reactor consists of a double layer of quartz glass (3.4 cm height, 7.5 cm inner diameter) (Figure S22) connected to a thermostated bath (XOSC-20, China), which allows operation at a constant temperature of 298 K. The previously prepared NPM solution was placed in the circular reactor and exposed to a Xenon lamp (Perfect Light, PLS-SXE 300, China) perpendicularly above the reactor. The output of the Xenon lamp was 14 cm away from the water surface. The spectral intensity of the Xenon lamp was measured by a calibrated spectro-radiometer (HP 350 UVP, China) (Figure S23).

Dry air collected from an air generator (HY-3, China) and a standard gas bottle of NO2 (10 parts per million (ppm) in N2, Messer Gases Co., Ltd.) in high purity nitrogen (99.99%, Messer Gases Co., Ltd.) were used for experiment. The photolysis of NO2 in an empty reactor was negligible under the experimental conditions. During the whole experiment, a constant flow of 800 mL min-1 of dry air controlled by the electronic soap film flowmeter was drifting through the reactor (SCal Plus, China) (Figure S22). The pH of NPM solution adjusted by preparing 1 mol L-1 NaOH and 1 mol L-1 HCl was set to 4-10 to assess its effect on the NPM photochemistry. Experiment list about experimental conditions as shown in Table S6.

Product measurements

NO, NO2, and HONO were detected using a chemiluminescence NOx analyzer (42i, THERMO) with a molybdenum converter. NO is measured by reacting NO with O3 to produce characteristic luminescence, and the intensity of luminescence is proportional to the concentration of NO. In the detection of NO2, molybdenum catalyst is used to convert NO2 to NO. A quartz tube (25 cm length, 2.9 cm inner diameter) filled with a certain amount of crystalline Na2CO3 was introduced to capture HONO between the circular reactor outlet and the NOx analyzer50. It is well known that almost all HONO molecules are in contact with Na2CO3, achieving high capture efficiency of HONO51,52,53,54,55. Therefore, HONO can be indirectly quantified by the difference between the NO2 signal with and without the Na2CO3 tube. The plausible photolysis of NO2 was also investigated under simulated sunlight irradiation by the xenon lamp. As shown in Figure S24, NO2 and NO concentrations under irradiation almost remained unchanged within the detection limit (0.4 ppb) of the NOx analyzer. We also performed additional test experiment to confirm the indirectly determined HONO values by using Water-Based Long-Path Absorption Photometer (WLPAP, Beijing Zhichen Technology Co., Ltd, China) on-line connected with the reactor for real-time measurements of HONO. Although there is a certain difference between HONO analyzer and Na2CO3 tube, the indirect method of HONO detection by Na2CO3 tube remains reliable (Figure S25). Photoproductions of O2-•, 1O2, and OH were quantified by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) using 5,5-Dimethyl-1-Pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO), 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine (TEMP) and 5,5-Dimethyl-1-Pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) as chemical probe molecules, respectively.

The aqueous phase products were identified by ultra high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Ultrapure water (A) and acetonitrile (ACN) (B), both containing 0.1% of formic acid, were used as mobile phases at a flow rate of 0.4 mL min-135(Table S7). The injection volume was set at 2.0 μL. MS analyses were done in selected Full Scan mode.

Quantification of NPM

The concentration of NPM before and after the reaction was quantified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). A mixture of water and ACN was used as the mobile phase with a ratio of 80:20 (v/v) and a flow rate of 0.5 mL min-1. The column temperature was kept at 30 °C, the injection volume was 20 μL, and the detection wavelength was set to 270 nm. The external standard method was used for the quantitative determination of NPM. For more details, see supporting information (Figure S26 and S27).

Kinetic analysis

The NPM photolysis kinetics was described using a first-order reaction (Eq. 1), and the half-life (t1/2) was calculated using Eq. 2.

where C0 (mg ml-1) and Ct (mg ml-1) are the initial concentration of NPM and the NPM concentration at time t, respectively; k is the rate coefficient.

Photoformation rates

The photoformation rates of NPM to produce HONO and NOx were calculated by Eq. 3 and Eq. 4, respectively.

where Q (mL min−1) and MNPM (g mol−1) are the total flow rate of gas in the reactor and the molar mass of NPM, respectively; t (min) is the illumination time; CtNOx (molecules cm−3) is the concentration of gaseous nitrogen-containing substances (HONO or NOx) formed by photolysis of NPM during the light irradiation period; NA is the Avogadro number; M0 (mg) and Mt (mg) are the masses of NPM at the beginning and end of the NPM photolysis experiment.

DFT calculations

All geometric optimizations have been carried out by density functional theory using the B3LYP hybrid functional56 with Grimme’s dispersion correction of D3 version (Becke-Johnson damping)57 implemented in Gaussian 16 suite of programs58. The 6-31 + G(d,p) basis set59,60,61 for all atoms was used. The S1 structure is optimized using TD-DFT method. Frequency calculations at the same level of theory have also been performed to identify all stationary points as minima (zero imaginary frequencies). Approximate solvent effects were taken into consideration based on the integral equation formalism variant of polarizable continuum model (IEFPCM)62 in the above calculations.The Cartesian coordination of optimized structures as shown in Table S8.

Global simulation of NOx and HONO fluxes and their chemical impacts

We estimated the global inventory of the NOx and HONO fluxes produced by NPM photochemistry using the observation-constrained parametrization scheme and hourly solar radiation data. Gridded and hourly downward solar radiation data are obtained from the Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Application version 2 (MERRA-2) assimilated meteorological fields. We calculated the flux of NOx and HONO for each model grid at a horizontal resolution of 0.5° × 0.625° (consistent with MERRA2 radiation dataset) following equation S1, but assuming different environmental NPM concentrations over agricultural areas, other continental land, and oceans, with the concentrations 2-4 orders of magnitude lower than the experimental concentration of 0.05 mg ml-1. We reset the parameterization of HONO and NOx productions from NPM photochemistry used in our estimation (Text S6). We also assume four additional scenarios for environmental NPM concentrations to assess the uncertainty of the estimated HONO and NOx productions (Table S4).

We applied the GEOS-Chem global chemical transport model version 13.3.163 to quantify the impact of NPM photochemistry on NOx and HONO levels in the atmosphere. The model is driven by MERRA-2 assimilated meteorological fields. GEOS-Chem describes a state-of-art ozone–NOx–VOCs–aerosol–halogen chemistry scheme and includes online calculation of dry and wet depositions of gases and aerosols on multiple land use type. It considers multiple chemical sources of HONO, including HONO formed by gas-phase reaction of NO with OH and HONO produced during the NO2 heterogeneous chemistry, but does not consider direct HONO emissions from soil and traffic which are negligible over the oceans. The GEOS-Chem physical schemes and emissions used in this study mostly follow the study by Wang et al.64, except that here we conducted the model at a global 2° × 2.5° resolution. Methane lifetime is calculated based on the GEOS-Chem output OH fields65. We performed two simulations with the NPM sources included/excluded in the model simulation and use the difference in the atmospheric constituents between the two simulations to estimate the impact of NPM photochemistry on NOx and HONO levels in the atmosphere.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Goulson, D. et al. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347, 1255957 (2015).

Sadaria, A. M. et al. Mass balance assessment for six neonicotinoid insecticides during conventional wastewater and wetland treatment: nationwide reconnaissance in United States wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 6199–6206 (2016).

Rundlöf, M. et al. Seed coating with a neonicotinoid insecticide negatively affects wild bees. Nature 521, 77–80 (2015).

Short, S. et al. Off-target stoichiometric binding identified from toxicogenomics explains why some species are more sensitive than others to a widely used neonicotinoid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 3059–3069 (2021).

Morrissey, C. A. et al. Neonicotinoid contamination of global surface waters and associated risk to aquatic invertebrates: a review. Environ. Int. 74, 291–303 (2015).

Bonmatin, J. M. et al. Environmental fate and exposure; neonicotinoids and fipronil. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 35–67 (2014).

Botías, C. et al. Neonicotinoid residues in wildflowers, a potential route of chronic exposure for bees. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 12731–12740 (2015).

Botías, C. et al. Response to Comment on ″Neonicotinoid Residues in Wildflowers, A Potential Route of Chronic Exposure for Bees. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 1630–1631 (2016).

Van der Sluijs, J. P. et al. Conclusions of the Worldwide Integrated Assessment on the risks of neonicotinoids and fipronil to biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 148–154 (2015).

Wang, W. et al. Unexpected formation of oxygen-free products and nitrous acid from the ozonolysis of the neonicotinoid nitenpyram. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 11321–11327 (2020).

Hladik, M. L. et al. Widespread occurence of neonicotinoid insecticides in streams in a high corn and soybean producing region, USA. Environ. Pollut. 193, 189–196 (2014).

Anderson, T. A. et al. Effects of landuse and precipitation on pesticides and water quality in playa lakes of the Southern high plains. Chemosphere 92, 84–90 (2013).

Wang, J. Q. et al. Meta-analysis of neonicotinoid insecticides in global surface waters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 1039–1047 (2023).

Lu, Z. et al. Quantum yields for direct photolysis of neonicotinoid insecticides in water: implications for exposure to nontarget aquatic organisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2, 188–192 (2015).

Aregahegn, K. Z. et al. Photochemistry of thin solid films of the neonicotinoid imidacloprid on surfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 2660–2668 (2017).

Ezell, M. J. et al. Experimental and theoretical studies of the environmental sensitivity of the absorption spectra and photochemistry of nitenpyram and analogs. ACS Earth Space Chem. 3, 2063–2075 (2019).

Xu, L. et al. Potential environmental health risk analysis of neonicotinoids and a synergist. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 7541–7550 (2021).

Gong, Y. et al. Separation and identification of photolysis products of clothianidin by ultra-performance liquid tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Lett. 45, 2483–2492 (2012).

Gligorovski, S. et al. Environmental implications of hydroxyl radicals (•OH). Chem. Rev. 115, 13051–13092 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Photoenhanced uptake of NO2 and HONO formation on real urban grime. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 6, 413–417 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Unexpectedly high indoor HONO concentrations associated with photochemical NO2 transformation on glass windows. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 15680–15688 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Light-enhanced heterogeneous conversion of NO2 to HONO on solid films consisting of fluorene and fluorene/Na2SO4: an impact on urban and indoor atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 11079–11086 (2020).

Sörgel, M. et al. Quantification of the unknown HONO daytime source and its relation to NO2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 10433–10447 (2011).

Elshorbany, Y. F. et al. Oxidation capacity of the city air of Santiago, Chile. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 2257–2273 (2009).

Gómez Alvarez, E. et al. Unexpectedly high indoor hydroxyl radical concentrations associated with nitrous acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 110, 13294–13299 (2013).

Stemmler, K. et al. Photosensitized reduction of nitrogen dioxide on humic acid as a source of nitrous acid. Nature 440, 195–198 (2006).

Ran, Z. et al. Formation of reactive nitrogen species promoted by iron ions through the photochemistry of a neonicotinoid insecticide. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 11943–11954 (2024).

Hinrichs, R. Z. et al. Solar absorption by aerosol-bound nitrophenols compared to aqueous and gaseous nitrophenols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 5661–5667 (2016).

Cai, J. et al. Spectral changes induced by pH variation of aqueous extracts derived from biomass burning aerosols: Under dark and in presence of simulated sunlight irradiation. Atmos. Environ. 185, 1–6 (2018).

Su, H. et al. Soil nitrite as a source of atmospheric HONO and OH radicals. Science 333, 1616–1618 (2011).

Scharko, N. K. et al. Release of nitrous acid and nitrogen dioxide from nitrate photolysis in acidic aqueous solutions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 11991–12001 (2014).

Mora Garcia, S. L. et al. Nitrous acid (HONO) formation from the irradiation of aqueous nitrate solutions in the presence of marine chromophoric dissolved organic matter: Comparison to other Organic photosensitizers. ACS Earth Space Chem. 5, 3056–3064 (2021).

Han, C. et al. Key role of pH in the photochemical conversion of NO2 to HONO on humic acid. Atmos. Environ. 142, 296–302 (2016).

Aregahegn, K. Z. et al. Photochemistry of solid films of the neonicotinoid nitenpyram. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2760–2767 (2018).

González-Mariño, I. et al. Photodegradation of nitenpyram under UV and solar radiation: Kinetics, transformation products identification and toxicity prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 644, 995–1005 (2018).

Bryukov, M. G. et al. Kinetics of HNO reactions with O2 and HNO. Chem. Phys. Lett. 208, 392–398 (1993).

Callear, A. B. et al. Thermal-decomposition of HNO. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2. 71, 1603–1609 (1975).

Lin, M. C. et al. Theoretical interpretation of the kinetics and mechanisms of the HNO+HNO and HNO+2NO reactions with a unified model. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 24, 489–516 (1992).

Luttke, W. et al. On the dimerization process of nitroso-compounds-a theoretical-study of the reaction 2HNO-(HNO)2. Theor. Chim. Acta 87, 321–333 (1994).

Palma, D. et al. New route to toxic nitro and nitroso products upon irradiation of micropollutant mixtures containing imidacloprid: role of NOx and effect of natural organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 3325–3333 (2020).

Carbajo, P. G. et al. NO2 quantum yields from ultraviolet photodissociation of methyl and isopropyl nitrate. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 6084–6091 (2010).

Orlando, J. J. et al. The atmospheric chemistry of alkoxy radicals. Chem. Rev. 103, 4657–4690 (2003).

Christie, M. I. et al. Association reactions of alkyl radicals with oxygen and with nitric oxide. Trans. Faraday Soc. 61, 468–473 (1965).

Barsotti, F. et al. Photochemical formation of nitrite and nitrous acid (HONO) upon irradiation of nitrophenols in aqueous solution and in viscous secondary organic aerosol proxy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 7486–7495 (2017).

Herrmann, H. et al. On the photolysis of simple anions and neutral molecules as sources of O−/OH, SOx− and Cl in aqueous solution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 3935–3964 (2007).

Tang, F. H. M. et al. CROPGRIDS: a global geo-referenced dataset of 173 crops. Sci. Data. 11, 413 (2024).

Van Dijk, T. C. et al. Macro-invertebrate decline in surface water polluted with imidacloprid. PloS one 8, e62374 (2013).

Lu, X. et al. The underappreciated role of agricultural soil nitrogen oxide emissions in ozone pollution regulation in North China. Nat. Commun. 12, 5021 (2021).

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Hu, T. et al. Enhanced formation of reactive nitrogen species by photochemical degradation of nitenpyram pesticides in the presence of halide ions. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 472, 116782 (2025).

Yang, W. et al. Photochemical emissions of HONO, NO2 and NO from the soil surface under simulated sunlight. Atmos. Environ. 234, 117596 (2020).

Cazoir, D. et al. Heterogeneous photochemistry of gaseous NO2 on solid fluoranthene films: A source of gaseous nitrous acid (HONO) in the urban environment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 273, 23–28 (2014).

Brigante, M. et al. Photoenhanced uptake of NO2 by pyrene solid films. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 9503–9508 (2008).

Monge, M. E. et al. Light changes the atmospheric reactivity of soot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 107, 6605–6609 (2010).

Zhou, S. et al. Time-resolved measurements of nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and nitrous acid in an occupied New York home. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 8355–8364 (2018).

Stephens, P. J. et al. Ab initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11623–11627 (1994).

Grimme, S. et al. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comp. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16, Revision A. 03, Gaussian. Inc., Wallingford CT.3. (2016).

Hehre, W. J. et al. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XII. Further extensions of Gaussian-type basis sets for use in molecular orbital studies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 56, 2257–2261 (1972).

Francl, M. M. et al. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarization-type basis set for second-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 77, 3654–3665 (1982).

Clark, T. et al. Efficient diffuse function-augmented basis sets for anion calculations. III. The 3-21+ G basis set for first-row elements, Li–F. Comp. Chem. 4, 294–301 (1983).

Tomasi, J. et al. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3094 (2005).

Bey, I. et al. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: Model description and evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 23073–23095 (2001).

John, J. G. et al. Climate versus emission drivers of methane lifetime against loss by tropospheric OH from 1860–2100. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 12021–12036 (2012).

Wang, H. et al. Global tropospheric ozone trends, attributions, and radiative impacts in 1995–2017: an integrated analysis using aircraft (IAGOS) observations, ozonesonde, and multi-decadal chemical model simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 13753–13782 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42477110, 42207127, 42030712, 42177087, and 42375092) and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Yunnan Province (Grant Nos. 202501AW070006, 202301AT070424). This study was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, Research Fund for International Scientists (4221101064). We are grateful to the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of National Natural Science Foundation of China (42321003), and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2022YFC3701103).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and Z.R. contributed equally to this work. J.L. and S.G. designed the research. Z.R. and Y.H. performed the laboratory experiments. X.L., S.L., J.Z. and Z.H. performed the model studies and discussions. J.L., C.Y., X.L and S.G. analyzed and interpreted the data from laboratory experiments. Y.H., D.H., K.L., H.W., X.W., Y.L. W.H and Z.J contributed to the relevant discussion in the Supporting Information. J.L. and S.G. wrote the paper. J.L., X.L., Y.L. and S.G. reviewed and edited the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Ran, Z., Hu, Y. et al. Aqueous photochemistry of neonicotinoids unveils a major source of atmospheric reactive nitrogen impacting global climate. npj Clim Atmos Sci 9, 16 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01286-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01286-4