Abstract

Trends in atmospheric circulation have begun to emerge in recent decades. Summertime mean circulation trends aloft have been attributed to human influence. For low-level extreme winds, the extent of human influence and climate model fidelity remains unclear. Here, we compare satellite-era trends in extratropical low-level mean and extreme (>90th percentile) winds defined using daily distribution in reanalyses and climate model simulations. In summer, Southern Hemisphere midlatitude winds have strengthened, driven by greenhouse gas and stratospheric ozone forcings. The summertime European wind stilling trend is dominated by aerosol and greenhouse gas forcings. In winter, models cannot capture the strengthening over the Southern Hemisphere and the weakening over Europe and the subtropical North Pacific. These discrepancies, particularly in the Pacific, are reduced but persist when observed sea surface temperatures are prescribed and affect the low-level baroclinicity. Our results highlight human influence on summertime low-level extreme wind trends and reveal regional wintertime discrepancies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change signals have begun to emerge in the satellite era for atmospheric circulation1. To date, most detected circulation changes focus on longitudinal or seasonal averages in the upper troposphere. For example, the summertime Eurasian upper-level jet stream has weakened significantly2 as has the Northern Hemisphere (NH) storm track measured by the eddy kinetic energy, which peaks in the upper troposphere3,4,5. These summertime mean circulation signals have been attributed to both aerosol and greenhouse gas forcings. In the Southern Hemisphere (SH) summer, the SH eddy-driven mean jet has shifted poleward. This poleward shift has been attributed to ozone forcing6,7. During the austral winter, the storm track, as measured by eddy kinetic energy, has strengthened significantly8,9; however, models struggle to capture the magnitude of this strengthening10.

Trends in low-level extreme winds have also emerged. In recent decades, observations and reanalyses suggest low-level extreme wind speed has increased over the ocean but decreased over the land11,12,13. The decreasing wind speed over the land is known as “terrestrial wind stilling”, which was first identified in the in-situ observations for both mean and extreme winds14,15. Some studies have further linked recent low-level wind trends to circulation changes in the lower free troposphere13,16. It remains unclear whether climate models can capture these trends in low-level extreme winds and whether there is human influence.

If climate models successfully capture trends in reanalyses, they can potentially be used to attribute human influence and understand the underlying processes. In contrast, discrepancies between reanalysis and modelled trends may reveal model deficiencies in representing key processes, leading to errors in simulated forced responses or natural variability17,18,19. For example, the discrepancy between observed and modelled sea surface temperature (SST) pattern trend in the tropical Pacific20 leads to a discrepancy in the wintertime storm track strengthening over the South Pacific10. Ultimately, comparing trends in reanalyses and climate model predictions is essential for having confidence in future projections, which include an end-of-century increase in the frequency and poleward shift of low-level extreme winds associated with extratropical cyclones21,22.

Here, we complement recent work that has attributed upper-level circulation trends to human influence by quantifying low-level extreme wind trends using the most up-to-date reanalysis datasets and comparing them to climate model predictions. We address the following questions: (1) Are low-level extreme wind trends in climate model simulations consistent with the reanalysis trends? (2) If yes, can the trends be attributed to human influence? (3) If no, what is the source of the reanalysis-model discrepancy?

Results

We quantify satellite-era reanalysis trends (1980–2019) in low-level mean and extreme winds using daily mean 850 hPa wind speeds from the three most up-to-date reanalysis datasets, which are ERA523, JRA-3Q24, and MERRA-225. We compare the reanalysis trends with coupled climate model simulations from historical (1980–2014) and SSP5-8.5 or SSP2-4.5 (2015–2019) scenarios. Motivated by hemispheric and seasonal differences in recent extratropical circulation trends1, we conduct our analysis separately for each hemisphere and the extended summer and winter seasons. To ensure a like-for-like comparison with climate models, all datasets are interpolated to 1. 5° × 1. 5° grids, consistent with previous studies10,19. The horizontally interpolated daily data are then used to determine the trends in low-level seasonal mean and extreme (>90th percentile) wind speed (see Methods). Using daily mean wind speed further focuses our analysis on low-level wind speed trends associated with extratropical cyclones (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 1).

Strengthening low-level mean and extreme wind speeds in the Southern Hemisphere

During the extended Southern Hemisphere summer season (October to March), low-level wind speed exhibits a positive trend, which is larger for mean than extreme winds (Fig. 1a). These summertime positive trends occur on the poleward flank of the climatological eddy-driven jet, particularly for the mean wind. The strengthening on the poleward side of the jet is consistent with the poleward shift of the eddy-driven mean jet identified in previous studies6,26.

a Multi-reanalyses mean trends (1980-2019) in 850 hPa mean and extreme (>90th percentile) wind speed in the SH midlatitudes in extended summer (October to March). Statistically significant linear trends (p-value < 0.05) are indicated by thick lines. The light grey curve depicts the climatological zonal mean wind speed. b, c Violin plot of 45°S-60°S area-weighted average trends (1980-2019) in the (b) mean and (c) extreme wind in the reanalysis, CMIP6 models, and CESM2-LE. Coloured circles are the trends of individual reanalyses or model ensembles. Statistically significant (p-value < 0.05) trends are filled. Large black circles are the multi-model mean trends. Numbers above model distributions represent the percentiles of individual reanalyses in CMIP6 and CESM2-LE ensemble distributions. The horizontal black dotted lines indicate the 5--95% range of the CMIP6 model trend distribution.

We compare the latitudinally averaged trends in the reanalysis with the trends calculated from climate models participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 [CMIP6,27]. We focus on the latitudes from 45°S to 60°S where the reanalysis trends peak and the fully coupled climate models (hereafter, CMIP6) simulate robust trends (Supplementary Figure 2b and d). During austral summer, the positive trends in both mean and extreme winds in reanalysis data are within the 5–95% range of the CMIP6 model trend distribution (Fig. 1b and c). To quantify the role of internal variability, we also compare the reanalysis trends with the trends in the fully-coupled Community Earth System Model version 2 Large Ensemble simulations (hereafter, CESM2-LE,28,29, see Methods). Although the reanalysis trends are at the upper edge of the CESM2-LE distribution, at least two out of three reanalyses still fall within the CESM2-LE distribution (Fig. 1b and c). These findings from CMIP6 and CESM2-LE indicate that fully coupled climate models can capture the summertime strengthening of low-level wind speeds in the SH.

We quantify human influence on low-level wind speed trends using single forcing experiments from the Detection and Attribution MIP [DAMIP, see also Methods30]. The summertime trends on the poleward flank of the jet are primarily attributed to greenhouse gas and stratospheric ozone forcings (Fig. 2). Greenhouse gases account for approximately 49.0% and 47.7% of the CMIP6 multi-model mean trends in mean and extreme winds, respectively. Stratospheric ozone contributes approximately 22.7% and 33.3% of the mean and extreme wind trends. Both greenhouse gas and stratospheric ozone forcings lead to increasing equator-to-pole temperature gradients in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere in austral summer (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). The increased lower-stratospheric meridional temperature gradient aligns with the poleward shift of the jet through thermal wind balance. Although the detailed mechanisms driving the low-level wind response are under debate1, the attribution to stratospheric ozone and greenhouse gas forcings is consistent with previous studies that show the impact of stratospheric ozone depletion and greenhouse gas on the poleward shift of the jet6.

Violin plots of linear trends (1980–2019) in the 850 hPa a mean and b extreme wind speed in reanalyses and DAMIP single forcing experiments averaged over 45°S-60°S in the extended austral summer (ONDJFM). Coloured circles are the trends of individual reanalyses or model ensembles. Statistically significant (p-value < 0.05) trends are filled. Large black circles are the multi-model mean trends. Coloured numbers represent the percentiles of individual reanalyses among the CMIP6 model trend distribution. The horizontal grey dashed lines are the summation of the ensemble mean trends in GHG, AER, and O3 experiments, quantifying human influence.

The Southern Hemisphere wintertime (April to September) trends have a different latitudinal structure compared to those in summer. During wintertime, low-level extreme winds strengthen in reanalysis data and occur at higher latitudes than the trends in mean winds (Fig. 3a). The latitudinal structure of the trends differs between reanalyses and CMIP6 models for both mean and extreme winds (Supplementary Fig. 2a and c). For the trends from 45°S-60°S, where the reanalysis trends are most robust, two reanalysis trends (MERRA-2 and ERA5) fall outside the 5–95% range of the CMIP6 model distribution of mean wind trends (Fig. 3b), and one reanalysis trend (MERRA-2) falls outside the 5–95% range of the CMIP6 model distribution of extreme wind trends (Fig. 3c). Similar disagreement also exists between trends in reanalyses and CESM2-LE (Fig. 3b and c). Thus, a discrepancy exists between reanalyses and climate models in winter for both mean and extreme winds.

a–c Similar to Fig. 1 but for the extended winter, from April to September. d, e Similar to b, c, but for latitudinal average trends in the historical period (1980–2013) in reanalysis, CMIP6, and AMIP6 models.

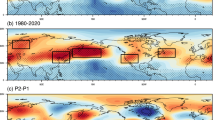

A discrepancy exists between observed SSTs and coupled model predictions over the Southern Ocean20. Thus, we investigate whether land-atmosphere models with the SST prescribed to observations (hereafter, AMIP6) can better simulate low-level wind trends. With the SST prescribed to observation, AMIP6 models can better capture the positive trend in the reanalysis compared to CMIP6 models during the historical period (1980–2013; Fig. 3d and e). The AMIP6 trend distribution is statistically significantly different than the CMIP6 trend distribution (Mann-Whitney p-value < 0.01). Over the South Pacific sector, where reanalysis trends are largest, AMIP6 models also simulate positive trends while CMIP6 models show near-zero multi-model mean trends (Fig. 4c and e). The low-level extreme wind trend differences between AMIP6 and CMIP6 models are consistent with the differences in the trend patterns of seasonal mean low-level air temperatures. The low-level meridional temperature gradient increases in reanalyses and AMIP6 models in the midlatitudes, but this temperature trend pattern is absent in CMIP6 models (Fig. 4d and f). This highlights an important connection between SST, low-level baroclinicity, and low-level wind trends.

Previous work suggested that the tropical Pacific SST trends can have a remote impact on the South Pacific circulation10,20. The recent La Niña-like tropical SST trend induces a teleconnection trend that impacts midlatitude low-level temperature gradients and thus strengthens the South Pacific wintertime storm track. Here, we quantify the impact of tropical Pacific SST trend discrepancy using CESM2-LE and CESM2 pacemaker experiments (hereafter, PacPACE; see Methods). The low-level extreme wind trends in fully coupled CESM2-LE are near-zero, consistent with the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Fig. 5 for 1980–2013). In contrast, the extreme wind trends in simulations with the observed tropical Pacific SST evolution (PacPACE) are larger and significantly different (Mann-Whitney test p-value < 0.01) from the trends in CESM2-LE. The overall trend pattern is consistent between PacPACE and reanalyses, although the magnitude of the trends remains underestimated by PacPACE (Fig. 5a and c). PacPACE also simulates a stronger low-level subtropical warming compared to CESM2-LE, therefore increased midlatitude temperature gradient in PacPACE (Supplementary Fig. 6b and c). The pacemaker simulation shows that the tropical Eastern Pacific SST has significantly influenced low-level baroclinicity and extreme wind trends in the South Pacific. However, since AMIP6 has even larger trends (comparing blue and cyan circles in Supplementary Fig. 5), SST outside the tropics (e.g., Southern Ocean) likely also plays a role in the wintertime low-level wind trend discrepancy.

a–c Map of a multi-reanalyses mean, b CESM2-LE ensemble mean, and c PacPACE ensemble mean trends (1980–2019) in low-level (850 hPa) extreme winds. Statistically significant trends (p-value < 0.05) are stippled. (d) Similar to Fig. 3c, but for South Pacific regional averaged trends in reanalyses, CMIP6, CESM2-LE, and PacPACE. The region is depicted by the green boxes in a-c. The cyan horizontal dotted lines denote the 5--95% range of the PacPACE ensemble distribution. Coloured numbers beneath model distributions represent the percentiles of individual reanalyses among the model distribution.

Weakening low-level mean and extreme wind speed in the Northern Hemisphere

During the extended NH summer season (April to September), a robust stilling of low-level mean winds occurs over Europe and part of western Asia (hereafter, Eurasia; green box in Fig. 6a), with a similar pattern but larger magnitude seen in low-level extreme winds (Fig. 6c). Less robust strengthening trends are seen over parts of East and South Asia, the Southeastern coast of the U.S., and a part of the subtropical North Atlantic (Supplementary Fig. 7). This structure of strong midlatitude stilling and weak subtropical strengthening in the NH is also evident when we aggregate data at a given latitude (Supplementary Fig. 8a). However, the midlatitude wind stilling trend is stronger and more robust than the subtropical strengthening. Given the strength and spatial coherence of the trends, we therefore focus on the detected stilling in low-level winds over Eurasia in what follows.

a, c Multi-reanalyses mean trends (1980–2019) map of 850 hPa a mean and c extreme winds over Eurasia in AMJJAS. Statistically significant trends (p-value < 0.05) are stippled. b, d Similar to Fig. 1b and c, but for regional averaged b mean and d extreme wind trends over Eurasia. The Eurasian region is depicted by the green boxes in (a) and (c).

For the summertime stilling over Eurasia, trends in mean winds from all three reanalyses fall within the 5–95% range of CMIP6 model spread (Fig. 6b), and trends in extreme winds from two out of three reanalyses fall within the 5–95% range of CMIP6 model spread (Fig. 6d). Similar agreement also exists between reanalyses and CESM2-LE (Fig. 6b and d).

We further use DAMIP single forcing experiments to attribute human influence on the recent stilling of low-level winds over Eurasia during NH summer. The single forcing experiments suggest that the negative trend in mean winds in CMIP6 models is driven by both aerosol and greenhouse gas forcings (Fig. 7a). Approximately 51.6% and 47.9% of the CMIP6 multi-model mean trend can be attributed to aerosol and greenhouse gas forcings, respectively. For extreme winds, the stilling in CMIP6 models is more dominated by aerosol forcing, which accounts for approximately 65% of the CMIP6 multi-model mean trend (Fig. 7b). Aerosol, together with the greenhouse gas forcings, in recent decades led to low-level warming in the mid- to high-latitudes in the NH (Supplementary Fig. 9c and d). This warming reduced the meridional temperature gradient near 45°N and hence weakened the summertime circulation in the NH midlatitudes. The attribution to aerosol forcings is consistent with previous findings of human influences on boreal summertime circulation weakening2,4,5. Note that the magnitude of the stilling in CMIP6 models underestimates the magnitude in reanalyses, especially in extreme winds. However, since the CMIP6 model spread is likely to capture reanalysis trends, the wind stilling in low-level mean and extreme winds in reanalyses can still be attributed to aerosol forcing.

Similar to Fig. 2, but for regional averaged trends over Eurasia.

During the extended NH winter season (October to March), low-level mean and extreme winds weaken over Europe and the subtropical North Pacific in reanalyses (Fig. 8a and b). A spatially more confined strengthening occurs around 50°N, consisting of a dipolar structure over the North Pacific. In the following discussion, we focus on the more robust and widespread weakening of extreme winds over Europe and the subtropical North Pacific.

Similar to Fig. 6, but focusing on regions of robust trends in ONDJFM.

Over Europe, none of the wintertime reanalysis trends fall within the 5–95% range of CMIP6 model spread (black circles in Fig. 8c), which is in contrast to summertime. The discrepancy exists between reanalyses and CESM2-LE as well (purple circles in Fig. 8c). The trend discrepancy between reanalyses and climate models during NH wintertime remains even when observed SSTs are prescribed in AMIP6 models (blue circles in Supplementary Fig. 10c). Regional trends in both CMIP6 and AMIP6 models are near zero and are not statistically different (Mann-Whitney test p-value ≈ 0.89). Thus, SST trends do not significantly influence the discrepancy in wintertime low-level extreme wind trends over Europe. The minor role of recent Arctic amplified surface warming in recent regional circulation trends is consistent with previous studies31. The sources of the reanalysis-model trend discrepancy over wintertime Europe remain unclear.

Over the subtropical North Pacific, CMIP6 models fail to capture the reanalysis trends in low-level extreme winds (black circles in Fig. 8d). During 1980-2013, the reanalysis trends also fall outside the 5–95% range of the AMIP6 model trend distribution (Supplementary Fig. 10d). The AMIP6 trend distribution is statistically significantly different than the CMIP6 trend distribution (Mann-Whitney test p-value ≈ 0.01). This highlights an important connection between low-level baroclinicity and low-level wind trends that can be seen when comparing trends in low-level temperature and low-level wind speed (Fig. 9). A consistent improvement from CMIP6 to AMIP6 models can also be seen for the positive trends of extreme winds around 50°N (Supplementary Fig. 11d). The dipole trend in low-level wind speed is also consistent with that seen at upper levels noted in previous work (Fig. 9,32). The improvement by considering historical SST evolution is similar to the wintertime trend in the SH midlatitudes (Fig. 3b and c), further supporting the role of SSTs in shaping regional low-level wind trend discrepancies.

1980–2013 trend maps of (left) 850 hPa extreme wind speed, (middle) 250 hPa seasonal mean zonal wind, and (right) 850 hPa seasonal mean air temperature in (a–c) reanalyses, d–f CMIP6, and g–i AMIP6 models in boreal winter, ONDJFM. Significant (p-value < 0.05) trends are stippled. The green boxes in the left column are identical to the North Pacific box in Fig. 8.

Discussion

Trends in atmospheric circulation have begun to emerge in the satellite era, and some upper-level trends have been attributed to human activities. Here, we compare satellite-era trends in extratropical low-level mean and extreme winds in reanalysis data with those in climate models. In the SH midlatitudes, low-level winds strengthen throughout the year in reanalyses. CMIP6 models successfully capture the summertime trends. The signals are due to human influence, specifically, they are attributed to greenhouse gas and stratospheric ozone forcings. In contrast, coupled climate models exhibit discrepancies in regional low-level wind trends during wintertime. The wintertime discrepancies between reanalyses and CMIP6 models are mainly due to the well-known SST trend discrepancy in coupled climate models. When the observed SST is prescribed, as in AMIP6 simulations, low-level wind speed trends in reanalyses and models are less discrepant. Our results indicate an important link between SST, low-level baroclinicity, and extreme near-surface wind trends. Tropical Pacific pacemaker simulations further suggest that the wintertime wind trend discrepancies, particularly over the Pacific sector, partly arise from the tropical Pacific SST trends by their remote impact on trends in the midlatitude low-level baroclinicity.

In the NH, low-level mean and extreme wind trends in reanalyses involve wind stilling over Europe in both summer and winter, as well as weakening during winter in the subtropical North Pacific. The summertime stilling trends over Europe are captured by CMIP6 models and attributed to aerosol forcing. In contrast, the wintertime trends in coupled climate models exhibit discrepancies with reanalysis trends. When SSTs are prescribed from observations, climate models still underestimate the wintertime trends. However, this reanalysis-model trend discrepancy in low-level extreme wind is reduced over the subtropical North Pacific in AMIP6 models, where the low-level baroclinicity trends are also less discrepant. This underscores the importance of SST trends in shaping regional low-level baroclinicity and wind speed trends during wintertime, consistent with the extreme wind trend discrepancies in the wintertime South Pacific.

The weakening low-level wind speed over Europe is consistent with the observed “terrestrial wind stilling” of the near-surface wind in recent decades14,15,33. Some previous studies suggested that terrestrial stilling is influenced by large-scale circulation changes in the lower troposphere13,16. A recent study focusing on hemispheric-averaged changes in annual mean winds over land suggested that the NH terrestrial stilling is triggered by greenhouse gas forcing34. However, focusing on the wind stilling over Europe in summertime, especially for extreme winds, our analysis suggests aerosol forcing is the dominant human influence consistent with the weakening circulation aloft2. Our results are also consistent with previous work that noted aerosol forcing has significantly weakened extratropical cyclone activity4. Combining our results with previous studies, we underscore the importance of aerosol forcing in regional low-level extreme wind trends.

The human influence on low-level wind speed in the Southern versus Northern Hemisphere is different. In the Southern Hemisphere, ozone and greenhouse gas forcings have increased the upper-level meridional temperature gradient consistent with the strengthening of the winds (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the Northern Hemisphere, aerosols and greenhouse gas forcings have led to higher latitude warming that decreases the low-level meridional temperature gradient (Supplementary Fig. 9). The aerosol forcing is concentrated over Europe due to decreased emissions locally35, leading to a particularly large impact on wind stilling. The differences in the forcing lead to the hemispheric asymmetric trends in low-level extreme winds.

To further enhance confidence in the detected trends and future projections of the low-level winds, it is essential to understand the underlying mechanism and examine representative variables from independent datasets. Future work will focus on unravelling the physical mechanisms driving the changes in low-level extreme winds.

Methods

Reanalysis datasets

The three state-of-the-art reanalysis datasets are used to quantify recent trends in low-level mean and extreme winds. The three reanalyses are ERA523, JRA-3Q24, and MERRA-225. Since JRA-3Q is a relatively new reanalysis, we test the sensitivity to dataset choice by comparing it with JRA-5536, which is widely used in previous studies [e.g., refs. 13,34]. In the regions of interest, differences in recent extratropical low-level extreme wind trends between JRA-55 and JRA-3Q are small (Supplementary Fig. 12). As the successor to JRA-55, JRA-3Q also shows improved consistency with newer-generation reanalyses in Southern Hemisphere storm track trends10 and better performance for small extratropical cyclones37. We therefore use JRA-3Q in our multi-reanalysis datasets.

We focus on the 40 years from 1980 to 2019 to accommodate the time covered by all datasets. The 850 hPa wind speed is calculated by the six-hourly zonal and meridional winds. The daily mean of the six-hourly wind speeds is then used for the percentile binning and trend analysis.

CMIP6 and AMIP6 model simulations

We use daily mean 850 hPa zonal and meridional winds in 25 CMIP6 models to calculate the daily mean low-level wind speed in fully-coupled climate model simulations. To be consistent with the trend period in reanalyses, we focus on the historical (1980 to 2014) and SSP5-8.5 (2015 to 2019) scenarios following previous works on the upper-level extreme winds38,39. To quantify the impact of discrepancies in SST trends in CMIP6 models, we also calculate daily mean 850 hPa wind speeds in 29 AMIP6 model historical simulations (1980–2014) with prescribed observed SST. The number of models used in each model ensemble is determined by the availability of daily mean 850 hPa zonal and meridional winds. We use the ’r1i1p1f1’ realization for all models to equally weigh each model. The CMIP6 and AMIP6 models used in our analyses are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

CMIP6 DAMIP simulations

For the reanalysis trends captured by CMIP6 fully-coupled simulations, we also examine daily mean 850 hPa wind speeds in single-forcing experiments from CMIP6 DAMIP simulations30 to quantify the contribution from individual climate forcings. We use single forcing experiments for anthropogenic aerosol (hist-aer, AER), greenhouse gas (hist-GHG, GHG), stratospheric ozone (hist-stratO3, O3), and natural forcing (hist-nat, NAT) from 1980 to 2019. For the AER, GHG, and NAT experiments, there are 35 simulations from eight models; for the O3 experiment, there are 22 simulations from four models. The number of models is determined by data availability. To better capture the model ensemble spread, we use all available realizations from each model for DAMIP simulations. The models and ensemble numbers of each model used in our analyses are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

CESM2 large ensemble and tropical pacemaker simulations

We use the Community Earth System Model version 2 [CESM2,28] fully-coupled large ensemble [CESM2-LE,29] and tropical Pacific pacemaker experiment (PacPACE, see https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/working-groups/climate/simulations/cesm2-pacific-pacemaker) to quantify the impact of the tropical Pacific SST trend discrepancies in the fully-coupled model simulations. The CESM2-LE simulations are a fully coupled single-model initial-condition ensemble. We use the first 50 ensemble members to represent the internal variability of a fully-coupled climate model. The ensemble is driven by the CMIP6 historical (1980 to 2014) and SSP3-7.0 (2015 to 2019) forcings.

The PacPACE simulations comprise 10 ensemble members spanning the period from 1980 to 2019. The external forcings are the same as those used in CESM2-LE. The model is fully coupled except in a wedge-shaped region from the American coast to the western Pacific within 20°S-20°N, where SST anomalies (relative to the 1880-2019 climatology) are nudged toward ERSSTv540 observations. We use the daily mean zonal and meridional wind at 850 hPa to calculate the daily mean low-level wind speed. The differences between PacPACE and CESM2-LE can be interpreted as influenced by discrepancies in the tropical Pacific SST trend.

Percentile binning and trend analysis

To ensure a like-for-like comparison across datasets, we calculate daily mean wind speeds on the data’s original grids and interpolate them onto a 1. 5° × 1. 5° grid using bilinear interpolation. The interpolated daily mean wind speeds are then used to determine seasonal mean and extreme winds. Since the circulation is mostly zonally symmetric for the Southern Hemisphere, we consider extreme winds as a function of latitude, following previous works investigating upper-level extreme winds38,39. By aggregating data across all longitudes and all days at a given latitude and within a given season each year, we then define wind speeds exceeding the 90th percentile as extreme winds. For the Northern Hemisphere, we consider extreme winds as a function of latitude and longitude due to the substantial zonal asymmetry. The extremes are defined locally by aggregating data across all days in a given season. The results are similar if we separate the Northern Hemisphere into four oceanic and continental sectors and aggregate the data across all days and longitudes within the given sector.

We use the percentile-binned data each year to calculate the trend in the satellite observational era. The multi-reanalyses and multi-model mean trends are calculated using the least-squares linear regression. We assess the statistical significance of the linear trends at the 95% confidence level according to a two-tailed t-test.

Data availability

The reanalysis data are available online (ERA5: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=download, JRA-3Q: https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/d640001/, and MERRA-2: https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets?project=MERRA-2). The CMIP6, AMIP6, and DAMIP model data are downloaded from the CMIP6 data search interface: https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. The CESM2-LE simulations are accessible via https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/community-projects/lens2. The PacPACE simulations are accessible via https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/working-groups/climate/simulations/.

Code availability

The codes to reproduce the main results of the manuscript are accessible via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17695484.

References

Shaw, T. A. et al. Emerging climate change signals in atmospheric circulation. AGU Adv. 5, e2024AV001297 (2024).

Dong, B., Sutton, R. T., Shaffrey, L. & Harvey, B. Recent decadal weakening of the summer Eurasian westerly jet attributable to anthropogenic aerosol emissions. Nat. Commun. 13, 1148 (2022).

Coumou, D., Lehmann, J. & Beckmann, J. The weakening summer circulation in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes. Science 348, 324–327 (2015).

Kang, J. M., Shaw, T. A. & Sun, L. Anthropogenic aerosols have significantly weakened the regional summertime circulation in the northern hemisphere during the satellite era. AGU Adv. 5, e2024AV001318 (2024).

Chemke, R. & Coumou, D. Human influence on the recent weakening of storm tracks in boreal summer. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 86 (2024).

Lee, S. & Feldstein, S. B. Detecting Ozone- and Greenhouse Gas–Driven Wind Trends with Observational Data. Science 339, 563–567 (2013).

Mindlin, J., Shepherd, T. G., Osman, M., Vera, C. S. & Kretschmer, M. Explaining and predicting the Southern Hemisphere Eddy Driven Jet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2025).

Shaw, T. A., Miyawaki, O. & Donohoe, A. Stormier Southern Hemisphere induced by topography and ocean circulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2123512119 (2022).

Chemke, R., Ming, Y. & Yuval, J. The intensification of winter mid-latitude storm tracks in the Southern Hemisphere. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 553–557 (2022).

Kang, J. M., Shaw, T. A., Kang, S. M., Simpson, I. R. & Yu, Y. Revisiting the reanalysis-model discrepancy in Southern Hemisphere winter storm track trends. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 252 (2024).

Young, I. R. & Ribal, A. Multiplatform evaluation of global trends in wind speed and wave height. Science 364, 548–552 (2019).

Wang, G., Wu, L., Mei, W. & Xie, S.-P. Ocean currents show global intensification of weak tropical cyclones. Nature 611, 496–500 (2022).

Torralba, V., Doblas-Reyes, F. J. & Gonzalez-Reviriego, N. Uncertainty in recent near-surface wind speed trends: A global reanalysis intercomparison. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 114019 (2017).

Vautard, R., Cattiaux, J., Yiou, P., Thépaut, J.-N. & Ciais, P. Northern Hemisphere atmospheric stilling partly attributed to an increase in surface roughness. Nat. Geosci. 3, 756–761 (2010).

McVicar, T. R. et al. Global review and synthesis of trends in observed terrestrial near-surface wind speeds: Implications for evaporation. J. Hydrol. 416–417, 182–205 (2012).

Zeng, Z. et al. A reversal in global terrestrial stilling and its implications for wind energy production. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 979–985 (2019).

Schmidt, G. On mismatches between models and observations — realclimate.org. https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2013/09/on-mismatches-between-models-and-observations/ (2013). [Accessed 19-02-2025].

Shaw, T. A. et al. Regional climate change: Consensus, discrepancies, and ways forward. Front. Clim. 6 (2024).

Simpson, I. R. et al. Confronting earth system model trends with observations. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt8035 (2025).

Wills, R. C. J., Dong, Y., Proistosecu, C., Armour, K. C. & Battisti, D. S. Systematic climate model biases in the large-scale patterns of recent sea-surface temperature and sea-level pressure change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100011 (2022).

Gastineau, G. & Soden, B. J. Model projected changes of extreme wind events in response to global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (2009).

Gentile, E. S., Zhao, M. & Hodges, K. Poleward intensification of midlatitude extreme winds under warmer climate. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 219 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Kosaka, Y. et al. The JRA-3Q Reanalysis. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 102, 49–109 (2024).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Woollings, T., Drouard, M., O’Reilly, C. H., Sexton, D. M. H. & McSweeney, C. Trends in the atmospheric jet streams are emerging in observations and could be linked to tropical warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 125 (2023).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the coupled model intercomparison project phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001916 (2020).

Rodgers, K. B. et al. Ubiquity of human-induced changes in climate variability. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 1393–1411 (2021).

Gillett, N. P. et al. The detection and attribution model intercomparison project (DAMIP v1.0) contribution to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3685–3697 (2016).

Blackport, R. & Screen, J. A. Insignificant effect of Arctic amplification on the amplitude of midlatitude atmospheric waves. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2880 (2020).

Patterson, M. & O’Reilly, C. H. Climate models struggle to simulate observed North Pacific jet trends, even accounting for tropical Pacific sea surface temperature trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL113561 (2025).

Wu, J., Zha, J., Zhao, D. & Yang, Q. Changes in terrestrial near-surface wind speed and their possible causes: an overview. Clim. Dyn. 51, 2039–2078 (2018).

Deng, K., Azorin-Molina, C., Minola, L., Zhang, G. & Chen, D. Global near-surface wind speed changes over the last decades revealed by reanalyses and cmip6 model simulations. J. Clim. 34, 2219–2234 (2021).

Quaas, J. et al. Robust evidence for reversal of the trend in aerosol effective climate forcing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 12221–12239 (2022).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: General Specifications and Basic Characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 93, 5–48 (2015).

Lee, J., Yang, X., Chang, E. K. M., Murakami, H. & Cooke, W. F. Sensitivity of northern hemisphere extratropical cyclone properties to atmospheric resolution in the GFDL SPEAR model. J. Clim.(2025).

Shaw, T. A. & Miyawaki, O. Fast upper-level jet stream winds get faster under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 61–67 (2024).

Shaw, T. A., Miyawaki, O., Chou, H.-H. & Blackport, R. Fast-get-faster explains wavier upper-level jet stream under climate change. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 653 (2024).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, version 5 (ersstv5): Upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Acknowledgements

H.H.C. and T.A.S. are supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration award NA23OAR4310597 and the National Science Foundation (NSF) award AGS2300037. G.Z. is supported by the U.S. NSF awards AGS-2327959 and RISE-2530555. We acknowledge the Climate Variability and Change Working Group and the CESM2 Large Ensemble Community Project at the NSF National Center of Atmospheric Research for running the Pacific pacemaker simulations and CESM2 large ensemble and making them available. We acknowledge the University of Chicago’s Research Computing Center for providing resources to accomplish the analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H.C. performed analysis and wrote the manuscript together with T.A.S. and G.Z.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chou, HH., Shaw, T.A. & Zhang, G. Human influence on recent trends in extratropical low-level wind speed. npj Clim Atmos Sci 9, 20 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01292-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01292-6