Abstract

Recent studies have uncovered evidences for pro-tumorigenic activities attributed to IL-11, prompting a renewed focus on therapeutic strategies targeting IL-11 signaling for anti-tumor treatment. Here, we introduce 9MW3811, a monoclonal antibody designed to neutralize IL-11 effectively. By disrupting the IL-11/IL-11Rα/gp130 complex, 9MW3811 inhibits JAK/STAT3 signaling, significantly reducing tumor growth in diverse mouse models. More importantly, 9MW3811 synergizes with anti-PD-1 therapy, even in PD-1 non-responsive models like CT26. Single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals that 9MW3811 remodels the tumor microenvironment by enhancing CD8+ T cell infiltration and reversing T cell exhaustion via upregulated XCL1 and downregulated CCL7, boosting anti-tumor cytotoxicity. Furthermore, 9MW3811 counteracts PD-1-induced T cell exhaustion, with anti-PD-1 antibodies effectively mitigating PD-1 upregulation post-9MW3811 treatment. These compelling findings support ongoing clinical trials of 9MW3811, aiming to translate these preclinical insights into therapeutic benefits for cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interleukin-11 (IL-11) belongs the IL-6 family of cytokines, which play pivotal roles in both health and disease, exerting pro- and anti-inflammatory functions1,2. Theses cytokines share a common transducing receptor, glycoprotein 130 (gp130). IL-11 signaling occurs when IL-11 binds to its ligand-binding receptor subunit IL-11Rα and gp130, activating pathways such as JAK/STAT, RAS/ERK and PI3K. The evidence implicating IL-11 in several diseases, predominantly through aberrant STAT3 activation, is now widely accepted. Low levels of IL-11 mRNA are found throughout the body but are rarely detected in serum of healthy individuals. However, in many diseases state such as fibrosis, various cancers, and viral infection, IL-11 overexpression is observed3,4,5. Elevated levels of IL-11 are associated with several types of cancer, including gastric cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, skin cancer, and bone cancer. IL-11 was found to be associated with poor prognosis in patients with osteosarcoma6, or with increasing tumor grade in endometrial and gastric adenocarcinoma7,8, these findings imply the important role of IL-11 in various tumor progression.

IL-11 signaling contributes to multiple aspects of tumorigenesis, including proliferation, angiogenesis, survival, metastasis, and migration9,10,11. Recent studies also highlight IL-11’s role in promoting immune evasion within the tumor microenvironment (TME). Beyond cancer cells, IL-11 is also secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and myeloid cells, facilitating bidirectional communication within the TME12. IL-11 produced by tumor stromal cells suppresses the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from CD4+ T cells, reducing T cell infiltration and promoting immune evasion, thereby remodeling the TME13. Given its multifaceted role in cancer progression, targeting IL-11 signaling emerges as a promising therapeutic strategy. Inhibition of IL-11 signaling represents a novel approach to disrupt tumor-promoting pathways and enhance anti-tumor immune responses, underscoring its potential in cancer therapy.

In this study, we identified and characterized an IL-11-targeting mAb, 9MW3811, with high blocking activity by disrupting the formation of IL-11/IL-11Rα/gp130 complex and inhibiting downstream JAK/STAT3 signaling activation. When used as a monotherapy, 9MW3811 demonstrated significant anti-tumor effects across various CDX and PDX models. Importantly, 9MW3811 also displayed synergistic effects when combined with an anti-PD-1 antibody in four different syngeneic models. Mechanistic studies further revealed that treatment with 9MW3811 enhances CD8+ T cell proliferation and reduces exhaustion gene signatures within the tumor microenvironment by modulating a variety of cytokines or chemokines. These results collectively demonstrate the profound anti-tumor activity of 9MW3811 across diverse tumor models and its ability to synergize with existing immunotherapies like anti-PD-1 antibodies. Currently, 9MW3811 is advancing through phase I clinical trials in Australia and China.

Results

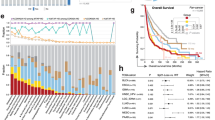

High IL-11 correlated with poor outcomes in patients with different tumors

Recent studies have highlighted elevated IL-11 expression in various cancers, including gastric, colorectal carcinoma, and colorectal adenoma14,15. To better understand the potential role of IL-11 in tumor progression, we leveraged data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to investigate its expression across different cancer types. Our analysis revealed significantly high IL-11 expression levels in patients with cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) (Fig. 1A). Next, we evaluated whether IL-11 expression impacts patients outcomes using Kaplan-Meier analysis, which demonstrated that higher IL-11 levels correlate with lower survival rates (Fig. 1B). This underscores IL-11’s potential as a prognostic marker in these cancers. Further insights into IL-11’s contribution to tumor biology were gained through prediction analysis using AIBERT, an AI-driven platform for Big Data analytics designed to assess the effectiveness of cancer therapies. AIBERT’s scoring system provides valuable indications for predicting therapeutic responses. The results showed that IL-11 plays a substantial role in cancers such as liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), and LUAD, with scores exceeding 0.2 (Fig. 1C).

A IL-11 is more overexpressed in CHOL, ESCA, HNSC, LUSC, LUAD, COAD, CESC, and BRCA (data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) than normal tissues (data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx). B Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of IL-11 mRNA levels for BRCA, CESC, CHOL, ACC, LUAD, PAAD, UCS, and COAD with datasets from TCGA and GTEx. C Relative contributions of IL-11 in different cancer types. The scores were evaluated by AIBERT®. D The impact of genetic loss of IL-11Rα on tumor growth was evaluated using MC38 cell line-derived tumor models with IL-11Rα knockout (IL-11RαKO-MC38). MC38 or IL-11RαKO-MC38 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into separate groups of C57BL/6J mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 8. E The effects of genetic loss of IL-11Rα on tumor growth were assessed in Hepa1-6 tumor models using C57BL/6J wild-type mice and IL-11Rα knockout mice (IL-11RαKO-mice). Hepa1-6 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into separate groups of C57BL/6 J wild-type or IL-11Rα KO mice, Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6.

To elucidate the necessity of IL-11 signaling in tumor progression, we conducted experiments comparing the growth of IL-11Rα knockout cell line MC38 (IL-11RαKO-MC38) with wild-type MC38, as well as comparing the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma Hepa1-6 in wild-type versus the IL-11Rα knock-out mice (IL-11RαKO-mice). Both IL-11RαKO groups displayed significantly slower tumor growth compared to wild-type counterparts (Fig. 1D, E). These data indicate that IL-11 signaling pathway, both in tumor cells (MC38 versus IL-11RαKO-MC38) and within the tumor microenvironment (WT mice versus IL-11RαKO-mice) contribute to tumor growth, implying that IL-11 pathway inhibitors could exert anti-tumor effects through multiple mechanisms.

Together, these findings strongly support the potential of blocking IL-11 signaling as a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of solid tumors.

9MW3811 blocks IL-11 signaling

To evaluate the potential of IL-11 signaling blockade as an anti-tumor therapeutic approach, we generated a panel of anti-IL-11 monoclonal antibodies using mouse hybridoma technology, followed by antibody humanization and affinity maturation. Among these candidates, 9MW3811 emerged with robust IL-11 binding activity and strong IL-11 signaling disrupting ability. Importantly, 9MW3811 demonstrated broad cross-reactivity with IL-11 derived from human, Mouse, Rat, and Canis, with EC50 values in the low nanomolar range (0.1–0.3 nM), indicating its potency across species (Fig. 2A). Notably, 9MW3811 showed no cross-reactivity with cynomolgus IL-11 (Fig. 2A, B).

A Binding activity of 9MW3811 with recombinant IL-11 from different species. B Binding activity of 9MW3811 with human IL-11, compared with X203, a reported anti-IL-11 neutralizing antibody. C Blocking activity of 9MW3811 against the formation of IL-11/IL-11Rα/gp130 protein complex, compared with X203. D Schematic representation of JAK/STAT3 signaling downstream of IL-11. E JAK/STAT3 signaling transduction inhibitions by 9MW3811 and X203 were performed by luciferase reporter gene assay, using IL-11Rα/STAT3-luc HEK293 cell line. F The inhibition of pSTAT3 stimulated by human IL-11 in HGC-27 tumor cells was detected by immunoblotting assay using Simple Western-Jess. Data is shown as mean± SD.

Blocking ELISA experiments confirmed that 9MW3811 effectively inhibits the formation of the IL-11/IL-11Rα/gp130 protein complex, achieving EC50 of 6.7 nM. Given that IL-11 is known to promote cancer development through activation of JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway15,16,17 (Fig. 2D), we assessed the inhibition activity of 9MW3811 against JAK-STAT3 signal activation. Consistent with the result of blocking ELISA, treatment with 9MW3811 dose-dependently reduced STAT3 phosphorylation and attenuated luciferase expression driven by STAT3 (Fig. 2E, F). Additionally, the inhibition of IL-11-induced phosphorylated ERK was also observed, further corroborating its capacity to disrupt IL-11 downstream signaling pathways (Supplementary Fig. 1). Comparison with X203, an IL-11-neutralizing antibody, which has been reported for the treatment of fibrotic diseases3,18, 9MW3811 displayed stronger activities across multiple assays ranging from 1.3 to 20-fold enhancements (Fig. 2B, F and Supplementary Fig. 1).

In summary, 9MW3811 could effectively block the formation of IL-11/IL-11Rα/gp130 protein complex, and inhibit the downstream signaling transduction pathways associated with IL-11.

9MW3811 exhibits anti-tumor activity and synergizes with anti-PD-1

We then used different tumor models to further evaluate the anti-tumor efficacy of 9MW3811 in vivo. In the NSCLC A549 xenograft model, treatment with 9MW3811 at 2 mg/kg significantly inhibited tumor growth compared with isotype control hIgG, achieving a tumor growth inhibition (TGI) of 62% (Fig. 3A). This data demonstrated promising anti-tumor activity of 9MW3811 in a xenograft setting. Further validation was conducted in two lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models. Treatment with 9MW3811 at 10 mg/kg resulted in TGIs of 50% and 28%, respectively (Fig. 3B, C), confirming its efficacy across different LUAD contexts through direct effects on tumor cells, as immunodeficient mice were used in these xenograft models.

A Anti-tumor effect of 9MW3811 in the lung cancer A549 model, as described in material and methods, cells were inoculated subcutaneously at the right flank of BALB/C nude mice, and 9MW3811 are administered by biw×9 when the tumor grew to approximately 60 mm3, n = 8. B and C Efficacy of 9MW3811 in LUC5351 and LUC-023 PDX model. tumor fragment (2–3 mm diameter) was inoculated subcutaneously at the right flank of NOD/SCID(B) or BABL/C nude mice (C). Drugs are administered by biw×8, n = 4 (B) or biw×9, n = 8 (C), when the tumor grows to 60–100 mm3. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. D–G Tumor growth (left panel) and tumor weight (right panel) measurement of MC38, Hepa1-6, CT26, H22 derived tumors after treatment of 9MW3811 (murine 9MW3811, m9MW3811), αPD-1, a combination of 9MW3811 and αPD-1, and control mouse IgG1. Hepa1-6 (D) and MC38 (E) cells were inoculated subcutaneously in C57BL/6J mice, while CT26 (F) and H22 (G) cells were inoculated subcutaneously in BALB/C mice. When the tumor grew to approximately 60-90 mm3, m9MW3811 and αPD-1 were administrated by i.p. as follows: m9MW3811 was administrated for 15 mpk and αPD-1 for 2 mpk, BIW×3 in Hepa1-6 (n = 6) (D), or m9MW3811 for 10 mpk, BIW×2 and αPD-1 for 0.5 mpk with single dose in MC38 model (n = 5) (E), or m9MW3811 for 10 mpk and αPD-1 for 1.5mpk, BIW×4 in CT26 model (n = 8) (F), or m9MW3811 for 10 mpk, BIW×6 and αPD-1 for 7.5mpk, BIW×4 in H22 model (n = 5) (G). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

IL11 signaling also promotes tumor growth by regulating TME (Fig. 1E). Therefore, we explored the potential synergistic effects of 9MW3811 in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors across four syngeneic tumor models. In MC38 and Hepa1-6 models (Fig. 3D, E), a single treatment with 9MW3811 or anti-PD-1 antibody individually showed moderate tumor inhibition (TGI around 30–40%). However, a combination of 9MW3811 with anti-PD-1 antibody resulted in significantly enhanced tumor growth inhibition, with total TGIs reaching 75–83%, indicating synergistic effects between anti-IL-11 and anti-PD-1 therapies. In the H22 model (Fig. 3G), where 9MW3811 alone had minimal effect on tumor growth, its combination with anti-PD-1 antibody increased the TGI from 71% to 84%, highlighting its ability to augment the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy. Notably, in the CT26 model (Fig. 3F), which was initially unresponsive to either anti-IL-11 or anti-PD1 monotherapy, the combination of 9MW3811 and anti-PD-1 antibody exhibited remarkable anti-tumor activity, achieving a TGI of 67%. This data underscores the potential of 9MW3811 to sensitize otherwise resistant tumors to anti-PD-1 therapy, demonstrating its versatility and broad applicability in combination treatments.

Taken together, these results further confirm the multi-dimensional effects of IL11 on tumor growth aligning with our IL-11RαKO studies (Fig. 1D, E), and strongly support the use of both monotherapy with 9MW3811 and combination therapy with anti-PD-1 and anti-IL-11 as potential strategies for treating patients with various types of cancer.

9MW3811 remodels the immune TME

Beyond the direct effects on tumor cells, anti-IL-11 therapy appears to exhibit crosstalk with anti-PD-1 therapy within the tumor microenvironment (TME). Tumor microenvironment is a complex and dynamically evolving milieu that supports tumor proliferation and progression. To explore the underlying mechanisms through which 9MW3811 affects the TME, we utilized FACS and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to analyze changes within the TME post-treatment. Cell infiltration analysis revealed that 9MW3811 treatment induced alterations in clusters of lymphocytes, macrophages, granulocytes, and fibroblasts (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 2). In both the Hepa1-6 and MC38 models, which responded favorably to anti-IL-11 therapy, we observed a noticeable increase in CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) following administration of 9MW3811 (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 2). In the Hepa1-6 model, we further delineated these CD8+ TILs into ten distinct clusters (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 3), among which a cluster characterized by high levels of Klrc1 showed a notable expansion (Fig. 4C). Klcr1 is a common marker associated with repeated TCR triggering and the proliferative potential of CD8+ T cells19,20. Recent single-cell analyses have linked Klrc1 expression with high cytotoxicity in CD8+ T cells21, suggesting its association with active local immunity in cancer patients and mouse models22. The increased proportion of Teff_Klrc cells indicates enhanced T cell cytotoxicity following 9MW3811 treatment.

The Hepa 1-6 syngeneic model was used for single-cell sequencing analysis. A and B Histograms indicating the proportion of major cell types (A, left panel) and CD8 T cell states (B, left panel) in each treatment group. Scatter plots showing the fraction of CD8+ T cells among immune cells (A, right panel) and Klc1+ Teff cells among CD8+ T cells (B, right panel) for each treatment group. The p-values were calculated by the two-sided Student’s t-test. C Boxplots indicating the mean expression levels of chemokines XCL1 (left panel) and CCL7 (right panel) in each treatment group. D Density plot showing the distribution of CD8+ T cell density over pseudotime for each treatment group. E Scatter plot showing the relationship between Pdcd1 expression and Klrc1 expression in cells from each treatment group. The plot includes a linear regression line (black). The Spearman correlation coefficient (rho) is 0.202, and the p-value is 7.61e−149, indicating a significant positive correlation. F Violin plots showing the mean expression levels of Gzmk (left panel), Ifng (middle panel), and Prf1 (right panel) in each treatment group. The p-values were calculated by the two-sided Student’s t-test. G Expression levels of Gzmk (left panel), Ifng (middle panel), and Prf1 (right panel) by qPCR analysis. Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH with N = 5. C–G Different colors indicate different treatment groups: black, NC-mIgG1; red, m9MW3811; Blue, anti-PD-1; purple, a combination of m9MW3811 and anti-PD-1.

To further investigate the mechanisms driving increased CD8+ TILs, we analyzed the gene expression profiles within the TME and identified alternations in chemokine expression. Specifically, we observed upregulation of XCL1 and downregulation of CCL7 after 9MW3811 treatment (Fig. 4C). Increased XCL1 levels are crucial for efficient cytotoxic immunity through the XCL1-XCR1 axis23, consistent with findings linking XCL1 expression with tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells24. Conversely, the downregulation of CCL7, a monocyte-specific chemokine, associated with MDSC migration and immune suppression25, likely contributes to enhanced CD8+ T cell infiltration post-9MW3811 treatment.

Mechanisms of the synergistic effects of anti-IL-11 combination with anti-PD-1

Our findings indicate that the enhanced TME immunity induced by anti-IL-11 therapy mainly stems from the increased tumor-infiltration of CD8+ T cells, particularly Teff_Klrc1, along with the modulation of chemokines such as XCL1 and CCL7. These findings are consistent with the synergistic effects observed with the combination of anti-IL-11 and anti-PD-1 therapies compared to anti-PD-1 monotherapy. Further, scRNA-seq analysis also provides additional evidence supporting the benefits of combining anti-IL-11 and anti-PD-1 therapies. ScRNA-seq profiling included the stimulation of a developmental trajectory of different T cells to describe their distribution across various states in different treatment groups. We observed a significant enrichment of exhausted T cells characterized by high TOX expression after PD-1 antibody treatment, suggesting that single anti-PD-1 therapy may accelerate T cell exhaustion. However, this exhaustion progress was attenuated by the addition of 9MW3811, indicating that combination with 9MW3811 can enhance immune function following anti-PD-1 treatment (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, spearman analysis showed an upregulation of PD-1 in the Teff_Klrc1 cell cluster after 9MW3811 treatment, highlighting the potential benefit of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade to maximum the efficacy of anti-IL-11 treatment (Fig. 4E).

Furthermore, the combination therapy group exhibited a marked increase in cytokines associated with sustained activation of cytotoxic Teff cells (e.g., Ifng, Prf1, Gzmk), whereas the monotherapy groups showed only modest upregulation of these cytokines (Fig. 4F, G and Supplementary Fig 4). Furthermore, significant suppression of Wnt signaling was observed in CD8+ T cells in both 9MW3811 and combination therapy groups. Likewise, downregulation of Wnt signaling is also observed in tumor cells in both treatment groups (Fig. 5A–D). These findings align with reports suggesting that IL-11 enhances Wnt signaling by suppressing expression of its inhibitors26, and studies indicating that inhibition of Wnt signaling increases infiltrating of CD8+ T cells in the TME27.

The Hepa 1-6 syngeneic model was used for analysis. A, C Heatmaps showing the activity of 14 signaling pathways in CD8+ T cells (A) and cancer cells (C) across different treatment groups. Colors represent the PROGENy scores, with red indicating higher activity and blue indicating lower activity. B, D Scatter plots showing the PROGENy scores for specific signaling pathways in CD8+ T cells (B) and cancer cells (D), comparing the four treatment groups. The p-values were calculated by the two-sided Student’s t-test. A–D Different colors indicate different treatment groups: black, NC-mIgG1; red, m9MW3811; Blue, anti-PD-1; purple, a combination of m9MW3811 and anti-PD-1.

The data presented above provide compelling evidence of a significant association between CD8+ T cells and the effects of 9MW3811 on the TME, which contributes to the enhanced efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy. Consistently, CD8+ T cell depletion through administration of anti-CD8 antibodies reduced the therapeutic efficacy of 9MW3811with TGI shifting from 46% to 16%, further highlighting the crucial involvement of CD8+ T cells in the anti-tumor effects of 9MW3811 within the TME (Supplementary Fig. 5).

In conclusion, our results uncover multiple mechanisms contributing to the reciprocal benefits achieved through a combination of anti-IL-11 therapy and anti-PD-1 therapies.

Pharmacokinetic and safety profile of 9MW3811 in SD rats and Beagle dogs

The PK profiles of 9MW3811 were characterized in single-dose studies conducted in SD rats and Beagle dogs, both are relevant species for 9MW3811 preclinical evaluation. In SD rats, following administration of 9MW3811 at doses of 10, 30, and 60 mg/kg (dose ratio 1:3.0:6.0), the mean AUClast values for serum 9MW3811 were 41.0, 126, and 263 h*mg/mL, respectively (inter-group ratio 1:3.1:6.4); mean AUC0-∞ values were 45.6, 143, and 289 h*mg/mL (inter-group ratio 1:3.1:6.3); mean Cmax values were 196, 544, and 1510 µg/mL (inter-group ratio 1:2.8:7.7); mean elimination half-lives (T1/2) were 400, 430, and 400 h, respectively (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Table 1). In Beagle dogs, following a single dose of 9MW3811 at 10, 30, and 60 mg/kg (dose ratio 1:3.0:6.0), the mean AUClast values for serum 9MW3811 were 23.8, 65.2, and 133 h*mg/mL (inter-group ratio 1:2.7:5.6); mean AUC0-∞ values were 24.7, 66.2, and 140 h*mg/mL (inter-group ratio 1:2.7:5.7); mean Cmax values were 123, 337, and 597 µg/mL (inter-group ratio 1:2.7:4.9); mean volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) values were 121, 124, and 154 mL/kg, respectively (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Table 2).

Following a single intravenous dose at 10, 30, and 60 mg/kg in naïve SD rats and Beagle dogs, the increases in AUClast, AUC0-∞, and Cmax were generally dose-proportional over the dose range. No significant gender differences were observed in the main pharmacokinetic parameters within each dose group (data not shown). An elimination pattern resembling that of a typical antibody was evident, characterized by slow clearance (CL of 0.215–0.227 mL/h/kg for rats and 0.419–0.471 mL/h/kg for dogs) and prolonged elimination half-life (T1/2 of 400–430 h for rats and 150–248 h for dogs). Distribution of 9MW3811 extended beyond the circulation system in rats, whereas it predominantly remained within the circulation system in dogs, as indicated by Vss when compared with weight-normalized animal plasma volume.

In the pivotal GLP-compliant repeat-dose study, 9MW3811 was well tolerated after weekly intravenous administrations for up to 3 doses in Beagle dogs (30, 100, or 300 mg/kg) and SD rats (30, 100, or 300 mg/kg). The main toxicological findings included anemia (decreased peripheral blood RBC, HGB, HCT, and decreased erythroid series (%) in bone marrow) and mild changes in lymphocyte counts in axillary or inguinal lymph nodes in Beagle dogs, but not in SD rats (Supplementary Table 3). Considering the tissue cross-reactivity observed in frozen Beagle dog tissues, these changes may be attributed to the binding of the test article to immune tissues, though detailed mechanisms require further investigation. The no observed adverse effect levels (NOAEL) were determined to be 300 mg/kg for SD rats and 100 mg/kg for Beagle dogs, respectively, while the highest non-severely toxic dose (HNSTD) was determined to be 300 mg/kg for Beagle dogs.

Discussion

IL-11 exhibits multifaceted effects across various cell types, initially recognized for its pro-fibrotic role in fibroblast, promoting migration and invasion associated with invasive fibroblasts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)3. Given its important role in fibrosis, IL-11 has become a promising therapeutic target for patients with IPF, with three ongoing phase I clinical trials (Lassen Therapeutics, NCT05331300; Boehringer Ingelheim, NCT05658107; and Mabwell Therapeutics, NCT05740475, CTR20231721). Additionally, IL-11’s pro-fibrotic effects extended to stimulating HSCs mesenchymal transitions and fibrosis in NASH and alcoholic liver disease, positioning IL-11 signaling as a target in these diseases18,28,29. Recent studies have revealed evidence for pro-tumorigenic activities elicited by IL-11 through both the autocrine effect on cancer cells and its suppressive effect on TME13,30,31,32. In this study, we developed a potent IL-11 neutralizing antibody, 9MW3811, to target both mechanisms and demonstrated its efficacy in suppressing tumor growth as a monotherapy and in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy (Fig. 7).

In three LUAD CDX and PDX models, we used immunodeficient mice lacking T cells to evaluate the effect of blocking the IL-11 autocrine pathway on tumor cells. Treatment with 9MW3811 resulted in significant, albeit moderate, tumor inhibition. These findings underscore the critical role of the IL-11-gp130/IL-11Ra-STAT3 signaling axis in cancer progression. However, they also suggest that disrupting the IL-11 autocrine pathway alone is insufficient for achieving sustained tumor suppression. This is not surprising, as cancer cells often rely on multiple pro-survival and pro-proliferation pathways, such as MAPK and PI3K, to support their uncontrolled growth. Single-pathway inhibition can often be bypassed by alternative signaling routes, which may help explain why many therapeutic strategies targeting the JAK/STAT3 pathway have failed in the treatment of solid tumors33.

IL-11 plays a crucial role in shaping an immunosuppressive TME13,30,31. In this study, we also aimed to evaluate this effect in syngeneic models. IL-11 blockade therapy with 9MW3811 increased CD8+ T cell infiltration, possibly by altering the expression profile of chemokines. PD-1/PD-L1 are key checkpoints in tumor immunotherapy; however, a significant number of cancer patients are either inherently resistant or eventually become refractory to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies. T cell infiltration into the TME is a critical determinant of response to such immunotherapies. Our findings in the CT26 model demonstrated resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy, which was notably overcome by combining 9MW3811 with anti-PD-1, resulting in a significant tumor growth inhibition of 67% (Fig. 3D). Additionally, our analyses revealed exacerbated T cell exhaustion following anti-PD-1 treatment, which may dampen the T cell-mediated immune response and contribute to therapy resistance. In contrast, the combination of 9MW3811 and anti-PD-1 antibody attenuated CD8+ T cell exhaustion. By enhancing T cell infiltration and reducing T cell exhaustion, 9MW3811 alleviates the suppressive TME, thereby enabling checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1 to elicit a stronger CD8+ T cell response. This therapeutic approach holds promise for clinical applications, particularly for patients resistant to checkpoint blockade therapy, and offers new insights into TME remodeling to improve immunotherapy efficacy.

The findings in our study differ from those of other recent studies that have also reported the immune-suppressive role of IL-1113,30,31. Huynh et al. reported that IL-11 suppressed host CD4+ T cells by decreasing the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFNg and TNFα13. Wenjun Xiong demonstrated that IL-11 activates STAT3 signaling while inhibiting IFN-γ-induced STAT1 phosphorylation, as well as downstream effects on T cell chemokine CXCL9 and MHC-I molecules, which lead to reduced CD8+ T cell infiltration and ultimately impairs immune surveillance31. Additionally, Sumida et al. found that IL-11 promotes the generation of CD11b+ CD14+ monocytic MDSCs via STAT3 activation30. Together, these studies, along with our findings, highlight the diverse and multifaceted immuno-regulatory roles of IL-11 within the TME. In specific contexts, one aspect of IL-11’s function may predominate.

IL-11 is a classic TGF-β response gene, with numerous studies confirming that cancer cell-derived TGF-β stimulates IL-11 production in various stromal cell types4. TGF-β has been shown to promote tumor growth by harnessing several key processes such as tumor cell proliferation, matrix remodeling, angiogenesis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), all of which can promote tumor progression and facilitate immune evasion34,35. TGF-β signaling inhibition has been introduced to anti-tumor therapy development, which is currently in clinical evaluation as monotherapy or combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, animal studies with TGFBR1 and pan-TGF-β antibodies have confirmed a risk for overt cardiovascular adverse effects characterized by heart valve thickening, hemorrhage, inflammation, and endothelial and stromal hyperplasia36,37, which arises pending safety concerns for clinical consideration. Targeting key downstream signaling of TGF-β, such as IL-11, may offer a more promising and attractive therapeutic approach, circumventing the potential drawbacks associated with upstream TGF-β blockade. Compared to TGF-β inhibition, neutralizing IL-11 with 9MW3811 demonstrates similar synergistic effects in the TME remodeling, enhancing PD-1 inhibition therapy. We speculate that the role of TGF-β in the TME may rely significantly on downstream IL-11 signaling. Notably, while TGF-β is expressed by various cell types across all tissues, IL-11 exhibits a more restricted expression pattern and is closely associated with pathological conditions such as infection, cancer, and fibrosis. This suggests that IL-11 signaling could serve as a more specific and targeted approach for systemic therapy.

There have already been several attempts to target IL-11 for cancer treatment, one example being the IL-11 mutein, which exhibited 20 times higher affinity to the IL-11 receptor than that of its wild-type counterpart, and effectively suppressed IL-11/STAT3 activation38. Consistent with our findings, IL-11 mutein has demonstrated efficacy in treating multiple tumors in gastric and colon xenograft models32. In comparison, 9MW3811, as a monoclonal antibody, is expected to have a long half-life, as demonstrated in our pharmacokinetic studies, making it a more convenient option for clinical administration.

In summary, based on compelling preclinical evidences, 9MW3811 shows promising potential as a monotherapy, particularly in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy. Currently undergoing phase 1 clinical trials for safety and tolerability (NCT05740475 and CTR20231721), 9MW3811 holds promise for advancing cancer treatment paradigms.

Methods

Patient datasets and data processing

GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index) was used to analyze IL-11 expression in different cancers (data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)) and normal tissues (data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx)). A difference was considered to be statistically significant when p < 0.01 and |log2 FC (fold change) ≥ 1 by two-tailed Student’s t-tests. The “Survival Map” module of GEPIA2 to obtain the Kaplan–Meier (K–M) curves of overall survival (OS) to IL-11 expression level was analyzed for BRCA, CESC, CHOL, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, LUAD and LUSC. All datasets were classified into high-risk and low-risk subgroups according to high (50%) and low (50%) cutoff values.

Generation of 9MW3811 and preparation of antibodies

B-IL-11 KO mice (112261, Biocytogen) mice were immunized with human IL-11 recombinant protein (S20030016, Qilu pharmaceutical). Titers of antibodies against human IL-11 in the mice serum were tested by ELISA. Three days after the last immunization, the spleen was harvested for hybridoma generation. Hybridomas producing antibodies specific for human IL-11 and mouse IL-11 were identified by ELISA. The candidate antibody, 9MW3811, was then obtained after humanization and affinity maturation. For the preparation of recombinant antibodies used in this study, heavy- and light-chain plasmids were transiently co-transfected into HEK293 cells or stably expressed in CHO-K1 cells followed by purification with Protein A resin.

ELISA-based binding assay

Human IL-11, Mouse IL-11 (50117-MNCE, Sino Biological), Cynomolgus IL-11 (cat. 90925-CNCE, Sino Biological), Rat IL-11 (Accession #G3V890, in house), or Canis IL-11 (Accession#FIPPR5, in house) was coated on 96-well plates at 0.5 μg/mL in 100 μL at 4 °C overnight. And then the plates were blocked with 2% FBS in PBS at 37 °C for 2 h. After washing 4 times with PBST, serially diluted antibodies were added to each well, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. Plates were washed 4 times with PBST before being incubated with anti-human IgG-HRP (2044-05, Southern Biotech) for 1 h. TMB was used for color development and absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

ELISA-based blocking assay

Human IL-11Rα-His (Accession #NP_004503.1, generated in-house) recombinant protein was coated on a 96-well plate at 0.5 μg/mL in 100 μL at 4 °C overnight, and then the plate was blocked with 2% FBS in PBS at 37 °C for 2 h. The mixture of 2 μg/mL human IL-11 and serially diluted antibodies (1:1) were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then same volume of 5 μg/mL gp130-mFc was added in and fully mixed, and the final mixture was added to the plate coated with IL-11Rα-His at 50 μL/well. After incubation at 37 °C 45 min, the plate was washed 4 times with PBST. Anti-mouse IgG-HRP (1030-05, Southern Biotech) was used for chemiluminescent detection. TMB was used for color development and absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Luciferase reporter gene assay

IL-11Rα/STAT3-luc HEK293 reporter cell line was constructed by transfecting the expression vector containing human IL-11Rα full-length gene (HG10252-UT, Sino Biological) into STAT3-Luc/HEK293 cells which constitutively express human gp130 STAT3-luciferase (CBPB0002, Nanjing Cobioer). IL-11Rα/STAT3-luc HEK293 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate (3 × 104/well). Serially diluted antibodies were added to the 96-well, and then human IL-11(S20030016, Qilu pharmaceutical) was added at a concentration of 0.64 ng/mL. The plate was incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 6 h. Bio-lite luciferase reporter gene assay kit (D1201-02, Vazyme) was used for luciferase activity analysis. The wells treated with only IL-11 or medium were used as the positive control (RLUpositive) and negative control (RLUnegative). The inhibition rate (%) was calculated as (RLUpositive−RLUsample)/(RLUpositive−RLUnegative)×100%.

Phospho-STAT3 signaling assays

HGC-27 (CL-0107, Wuhan Pricella) cells were seeded the day before the assay in a 12-well plate at 2 × 105 cells per well. Cells were starved in serum-free media for 16 h. For antagonism assays, IL-11 at 50 ng/mL simultaneously with the indicated concentration of 9MW3811, X203, or Isotype control NC-hIgG1 were added to the serum-starved cells for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS. Cell lysates were obtained using RIPA Lysis buffer (P0013B, Beyotime) and quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay (23225, ThermoFisher Scientific). Samples electrophoresis immunoblots were performed using the Simple Western system (ProteinSimple). The following primary and secondary antibodies were used: Total-STAT3 (12640, CST), phospho-STAT3 (9131, CST), vinculin (13901, CST), Total-ERK (4695, CST), phospho-ERK (80031-1-RR, Proteintech), β-Actin (4970, CST), Anti-Rabbit Detection Module (DM001, ProteinSimple). Data were analyzed using the Compass for SW software (ProteinSimple). Chemiluminescent signals were measured as the area under the curve. The inhibition (%) was calculated as: (correction area of single IL-11 stimulation−correction area of sample)/(correction area of single IL-11 stimulation−correction area of IL-11 free)×100%.

Mouse tumor models

All mouse experiments were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Yicon (Beijing) BioMedical Technology Inc. Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions, dark/light cycles: 12-h light/12-h dark, ambient temperature 20–26 °C and humidity 40–70%, ventilated four times per hour. Six to eight-week-old mice are randomly divided into different groups for subsequent experiments. Euthanasia was implemented under some circumstances: such as tumor volume was more than 3000 mm3, extremely weak physiology conditions, and tumor burden that leads to ulcers and abnormal behavior. After euthanizing the mice with carbon dioxide, individual tissues from each group of mice were collected for subsequent experiments. Animal studies complied with the ARRIVE guidelines (Supplementary File 2).

IL-11/IL-11Ra signaling influence on tumor growth

6-8 weeks male C57BL/6J (Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.) mice (n = 16) were selected and randomly divided into two groups, MC38 (KC-1279, KYinno) or IL-11RαKO-MC38 (KC-2286, KYinno) cells were resuspended in PBS (3 × 107/mL) and then inoculated subcutaneously into the back of mice at 100 μL/mouse.

Hepa 1-6 cells (CRL-1830, ATCC) were resuspended in PBS (5 × 107/mL) inoculated subcutaneously into the back of C57BL/6 IL-11Ra1-KO (NM-KO-190453, Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc.) mice (IL-11RαKO-mice) or wild type C57BL/6 mice (male and female, 1:1 in quantity, 6-8 weeks, n = 10 for each) at 100 μL/mouse.

9MW3811 antitumor efficacy Analysis

For the A549 CDX model, A549 cells were resuspended in PBS (5 × 107/mL) were inoculated subcutaneously into the back of 6–8 weeks female BALB/c nude mice (n = 30, GemPharmatech Co., Ltd.) at 100 μL/mouse. When the average TV reached about 62 mm3, the mice were randomized into three groups (n = 8). 9MW3811 was administrated for 0.4 and 2.0 mpk by i.p., BIW×9, and Isotype control NC-hIgG1 was administrated for 10.0 mpk by i.p., BIW×9.

For the human LUAD PDX LU5351 model, 6–8 weeks female NOD/SCID mice (n = 40, GemPharmatech Co., Ltd.) were inoculated subcutaneously at the right flank with one tumor fragment (2–3 mm diameter). When the average TV reached about 80–100 mm3, the mice were randomized into two groups. 9MW3811 and Isotype control NC-hIgG1 were administrated for 10.0 mpk by i.p., BIW×8. For the human LUAD PDX LUC-023 model, female BALB/c nude mice were used.

For syngeneic models, MC38 (KC-1307, KYinno) at a density of 5 × 107/mL or Hepa 1-6 (CRL-1830, ATCC) at a density of 5 × 106/mL were inoculated subcutaneously at the right flank of C57BL/6J mice at 100 μL/mouse, CT-26 (CRL-2638, ATCC) at a density of 5 × 106/mL or H22 (3111C0001CCC000309, NSTI-BMCR) at a density of 1 × 107/mL were inoculated subcutaneously at the right flank of Balb/C mice at 100 μL/mouse. When the tumor grew to ~60–90 mm3, NC-IgG1, murine 9MW3811 (m9MW3811), αPD-1, and a combination of m9MW3811 and αPD-1 was administrated as per the experimental design.

Tumor volume was measured twice a week using a vernier caliper, with the long and short diameters of the tumors measured, and the volume was calculated as

At the end of the study, animals were euthanized, tumors were removed and weighed, and placed neatly and photographed.

Flow cytometry analysis

Tumors were collected and processed under sterile conditions. Single-cell tumor digest suspensions were prepared, and red blood cells were lysed. For analysis of immune cell populations, cells (tumor digest suspension from 0.1 g tumor) were incubated for 30–60 min with mCD45 (563891, BD), mCD3 (100204, Biolegend), mCD335 (560755, BD), mCD11b (550993, BD), mCD11c (117339, Biolegend), mCD86 (105043, Biolegend), mCD206 (25-2061-82, eBioscience) in staining buffer on ice in dark for surface expression analysis, according to the manufacturer. After washing cells with 1×PBS for twice, cells were incubated for 5–10 min with Live/Dead F4/80 (63-4801-82, eBioscience) in 1×PBS at room temperature in the dark. Samples were gated and analyzed by Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher).

ScRNA-seq data analysis

The Hepa 1–6 syngeneic model was utilized for scRNA-seq analysis. C57BL/6J mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 5 × 106 Hepa 1-6 cells per mouse into the right flank. Treatment groups were administered m9MW3811 at 10 mg/kg and αPD-1 at 1 mg/kg via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection biweekly for four doses, starting when the tumors reached ~50 mm3 (n = 6 per group). Tumors were monitored, and the study was concluded when tumor volume in the control group exceeded 2000 mm³ (~2 weeks after the final treatment). Tumors from each group, with a size range of 400–1000 mm³, were collected for scRNA-seq analysis.

For library preparation, tumor tissue was stored in MACS® Tissue Storage Solution (PN:130-100-008; Miltenyi Biotec) for ~32 h prior to dissociation into single cells using the Tumor Dissociation Kit (PN:130-096-730; Miltenyi Biotec) and the gentleMACS™ Octo Dissociator with Heaters (PN:130-096-427; Miltenyi Biotec). Red blood cells were lysed with Red Blood Cell Lysis Solution (10×) (PN:130-094-183; Miltenyi Biotec), followed by washing with PBS and dead cell removal using the Dead Cell Removal Kit (PN:130-090-101; Miltenyi Biotec). The resulting viable single-cell suspension was resuspended in 1× PBS supplemented with 0.04% BSA at a final concentration of 700–1200 cells/μL.

A total of 16,500 cells were loaded onto the Single Cell G Chip (PN:1000127; 10x Genomics, Inc.) using the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3’ v3.1 Reagent Kit (PN:1000130; 10x Genomics, Inc.) and the Chromium Controller (PN:120270; 10x Genomics, Inc.). Cell suspensions were mixed with barcoded Single Cell 3’ v3.1 Gel Beads and Partitioning Oil to generate nanoliter-scale Gel Beads in Emulsion (GEMs). Reverse transcription PCR was performed to generate full-length cDNA, followed by incubation at 53 °C for 45 min, 85 °C for 5 min, and holding at 4 °C. The first-strand cDNA was then purified using Dynabeads MyOne SILANE (PN:1000048; 10x Genomics, Inc.) cleanup mix. The cDNA was amplified in an amplification reaction mix using the Thermal Cycler (Long Gene A300) under the following program: 98 °C for 3 min, 98 °C for 15 s, 63 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 1 min (steps 2–4 for a total of 11 cycles), and then held at 4 °C. Subsequently, the amplified cDNA was used to generate a single-cell 3’ gene expression dual-index library using the Library Construction Kit (PN:1000196; 10x Genomics, Inc.) and the Dual Index Kit TT Set A (PN:1000215; 10x Genomics, Inc.). The final single-cell 3’ gene expression libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer.

scRNA-seq data were aligned and quantified using the kallisto39 against the reference genome GRCm39. Empty droplets were filtered using the emptyDrops function of the R package dropletUtils40. Cell doublets were predicted by Scrublet41 and removed before the next analysis. Cells of low quality were also removed; these were evaluated based on multiple metrics: (1) cells with a total UMI count (library size) of 0; (2) cells where the percentage of mitochondrial genes exceeded 25%; (3) cells with a high doublet score and concurrent high expression of markers from multiple cell types. After quality control was completed for individual samples, cell-gene count matrices integration and batch effect removal were conducted using Scanpy42 and Harmony43, respectively.

To determine the major T cell types and states, multiple layers of evidence were integrated. First, cell types were delineated using well-known marker genes44,45, such as Cd8a, Cd8b1 for CD8 T cells, and Cd4, Foxp3and Il2Ra for CD4 T cells. Second, cluster-specific exclusive genes were identified, defined by a log fold change >1.2, a Benjamini–Hochberg-corrected P value < 0.05, and expression in at least 30% of the cells in each cluster. Third, gene signature scores associated with T cell differentiation and cell functionality46 using R package UCell47 were calculated. Finally, by amalgamating all evidence and information, comprehensive cellular annotations for T cell types and states were defined. Two-sided Student’s t-test with unpaired samples was used to identify changes in cell cluster proportions across treatment conditions.

RNA velocity analysis48 utilizes the ratio of unspliced to spliced mRNAs to project the future states of individual cells, serving as a predictor of cellular dynamism. The unspliced and spliced UMIs were counted by kallisto39. Building on this processed data, velocity analysis was performed using the Python package scVelo49. The velocity vector and pseudotime for each cell were calculated using the dynamical model in scVelo.

To discern transcriptional disparities among four distinct cell cluster cohorts, normalized datasets derived from triplicates for each treatment group were employed to calculate mean expression values to generate pseudo-bulk samples. Statistical comparison of expression variances across groups was facilitated through the application of a Student’s t-test.

To assess the interrelation of Pdcd1 and Klrc1 expression at the single-cell level, a correlation analysis was executed across four distinct cell populations. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho) was calculated to measure the association strength and direction between the two genes’ expression levels. A best-fit line was plotted through the data points to graphically delineate the connection.

Pathway activity for 14 signaling pathways, including Androgen, Estrogen, EGFR, Hypoxia, JAK-STAT, MAPK, NFkB, PI3K, p53, TGFb, TNFa, Trail, VEGF, and WNT, was inferred using the tool PROGENy50. The PROGENy scores by cell population within each sample were depicted in a heatmap. Additionally, pairwise comparisons of the scores across four treatment groups were performed using Student’s t-tests.

Expression levels of cytokines by qPCR analysis

Hepa 1-6 cells(CRL-1830, ATCC) were resuspended in PBS (1 × 108/mL) were inoculated subcutaneously into the back of 5–6 weeks male C57BL/6 mice (Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.) at 100 μL/mouse. When the average TV reached about 80 mm3, the mice were randomized for 4 groups (n = 5), and murine 9MW3811 (m9MW3811) was administrated for 10 mpk and αPD-1 for 1mpk by i.p., BIW×3. At the end of the study, animals were euthanized, and tumor tissues were collected and snap-frozen for RNA extraction. RNA was isolated using the FastPure Complex Tissue/Cell Total RNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme, RC113) and then converted to cDNA. qPCR analysis was performed using the SYBR Green System (Vazyme, Q712). The primers used for qPCR were as follows: Mouse Ifng (Beyotime, QM03298S), Mouse Prf1 (Beyotime, QM04414S), Mouse Gzmk (Beyotime, QM14326S), and Mouse GAPDH (Beyotime, QM00014M). Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH, and the relative mRNA quantification was calculated accordingly.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) and toxicity study of 9MW3811

All SD rat and Beagle dog-related experiments were conducted at WestChina-Frontier PharmaTech Co., Ltd. (WCFP) in accordance with the standard operating procedure and the related protocols complied with relevant ethical regulations.

The pharmacokinetic profiles of 9MW3811 were assessed in SD rats and Beagle dogs, chosen as pharmacologically relevant species. In SD rats, 24 animals were randomly divided into 3 groups (4 males and 4 females per group), receiving intravenous injections of 9MW3811 at doses of 10, 30, and 60 mg/kg, respectively, with a dose volume of 2 mL/kg. Blood samples for pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis were collected pre-dose and at 5 min, 2, 8, 24, 96, 168, 336, 504, 672, 1008, and 1334 h post-dose. Similarly, in Beagle dogs, 18 animals were randomly allocated into 3 groups (3 males and 3 females per group), receiving single intravenous doses of 9MW3811 at 10, 30, and 60 mg/kg, with a dose volume of 2 mL/kg. Blood samples for PK analysis were collected pre-dose and at 5 min, 6, 24, 72, 144, 240, 336, 504, 672, 1008, and 1344 h post-dose. Serum concentrations of 9MW3811 were determined using a validated ELISA method conducted by an independent laboratory (Jiangsu Tripod Preclinical Research Laboratories Co., Ltd.). Key pharmacokinetic parameters such as area under the concentration-time curve (AUC), maximum concentration (Cmax), elimination half-life (T1/2), and volume of distribution (Vd) were calculated using WinNonlin 8.1 software.

The toxicity study of 9MW3811 was conducted by WCFP in a GLP-compliant, 4-week pivotal toxicity study in SD rats and Beagle dogs. For SD rats, 76 animals (19 rats per sex per group, with 4 rats per sex designated for TK analysis) were divided into 4 groups. They received intravenous administrations of either control article or 9MW3811 dose formulations at 30, 100, and 300 mg/kg once a week for 5 consecutive doses. The dosing was conducted using a dose volume of 10 mL/kg administered at a rate of 1 mL/min. For Beagle dogs, 50 animals (5 dogs per sex per group) were divided into 5 groups. They received intravenous administrations of negative control or 9MW3811 dose formulations at 30, 100, and 300 mg/kg once a week for 4 consecutive weeks (totaling 5 doses), followed by a 4-week recovery phase. The dose volume administered was 10 mL/kg, and each dose was administered over ~30 min. Post-dose observations, clinical pathology evaluations, immunotoxicity-related tests, assessments of local tolerance, and examinations of gross pathology and histopathology were conducted as part of the comprehensive assessment of potential toxicities associated with 9MW3811 in both species.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism (v 9.0) and all data were expressed as means ± SE or means ± SD as indicated. Statistical analyses were performed using a nonparametric two-tailed t-test or two-way ANOVA. Unless specially described, error bars stand for the standard error of the mean. P values < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), and < 0.001 (***) were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and the supplementary file linked to this article. Any additional information, resources, and reagents related to this paper are available from the corresponding author (Shuang Wang, shuang.wang@mabwell.com) upon request. The materials and data will be made available upon request after the completion of a material transfer agreement.

References

Garbers, C. & Scheller, J. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-11: same same but different. Biol. Chem. 394, 1145–1161 (2013).

Scheller, J., Garbers, C. & Rose-John, S. Interleukin-6: from basic biology to selective blockade of pro-inflammatory activities. Semin. Immunol. 26, 2–12 (2014).

Ng, B. et al. Interleukin-11 is a therapeutic target in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, 511 (2019).

Putoczki, T. L. & Ernst, M. IL-11 signaling as a therapeutic target for cancer. Immunotherapy 7, 441–453 (2015).

Einarsson, O. et al. Interleukin-11: stimulation in vivo and in vitro by respiratory viruses and induction of airways hyperresponsiveness. J. Clin. Investig. 97, 915–924 (1996).

Lewis, V. O. et al. BMTP-11 is active in preclinical models of human osteosarcoma and a candidate targeted drug for clinical translation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8065–8070 (2017).

Yap, J. et al. Interleukin 11 is upregulated in uterine lavage and endometrial cancer cells in women with endometrial carcinoma. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 8, 63 (2010).

Necula, L. G. et al. IL-6 and IL-11 as markers for tumor aggressiveness and prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma patients without mutations in Gp130 subunits. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 21, 23–29 (2012).

Sotiriou, C. et al. Interleukins-6 and -11 expression in primary breast cancer and subsequent development of bone metastases. Cancer Lett. 169, 87–95 (2001).

Cui, M. et al. The role of IL-11 and IL-Ra in angiogenesis of breast cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 9, 11682–11687 (2016).

Solakoglu, O. et al. Heterogeneous proliferative potential of occult metastatic cells in bone marrow of patients with solid epithelial tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2246–2251 (2002).

Maroni, P. et al. Interleukin 11 (IL-11): role(s) in breast cancer bone metastases. Biomedicines 9, 659 (2021).

Huynh, J. et al. Host IL11 signaling suppresses CD4(+) T cell-mediated antitumor responses to colon cancer in mice. Cancer Immunol. Res. 9, 735–747 (2021).

Kang, Y. et al. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell 3, 537–549 (2003).

Putoczki, T. & Ernst, M. More than a sidekick: the IL-6 family cytokine IL-11 links inflammation to cancer. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 1109–1117 (2010).

Bollrath, J. et al. gp130-mediated Stat3 activation in enterocytes regulates cell survival and cell-cycle progression during colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 15, 91–102 (2009).

To, S. Q. et al. STAT3 signaling in breast cancer: multicellular actions and therapeutic potential. Cancers (Basel) 14, 429 (2022).

Widjaja, A. A. et al. Inhibiting interleukin 11 signaling reduces hepatocyte death and liver fibrosis, inflammation, and steatosis in mouse models of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 157, 777–792.e14 (2019).

Borst, L. et al. NKG2A is a late immune checkpoint on CD8 T cells and marks repeated stimulation and cell division. Int. J. Cancer 150, 688–704 (2022).

Byers, A. M., Andrews, N. P. & Lukacher, A. E. CD94/NKG2A expression is associated with proliferative potential of CD8 T cells during persistent polyoma virus infection. J. Immunol. 176, 6121–6129 (2006).

Mathewson, N. D. et al. Inhibitory CD161 receptor identified in glioma-infiltrating T cells by single-cell analysis. Cell 184, 1281–1298.e26 (2021).

van Montfoort, N. et al. NKG2A blockade potentiates CD8 T cell immunity induced by cancer vaccines. Cell 175, 1744–1755.e15 (2018).

Dorner, B. G. et al. Selective expression of the chemokine receptor XCR1 on cross-presenting dendritic cells determines cooperation with CD8+ . T Cells Immun. 31, 823–833 (2009).

Tamura, R. et al. XCL1 expression correlates with CD8-positive T cells infiltration and PD-L1 expression in squamous cell carcinoma arising from mature cystic teratoma of the ovary. Oncogene 39, 3541–3554 (2020).

Mise, Y. et al. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in uterine serous carcinoma via CCL7 signal with myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Carcinogenesis 43, 647–658 (2022).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by interleukin-11 via AP-1 and Smad signaling. Endocr. J. 59, 91–101 (2012).

Wall, J. A. et al. Manipulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to promote anti-tumor immune infiltration into the TME to sensitize ovarian cancer to ICB therapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 160, 285–294 (2021).

Effenberger, M. et al. Interleukin-11 drives human and mouse alcohol-related liver disease. Gut 72, 168–179 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Nanoparticle-mediated RNA therapy attenuates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and related fibrosis by targeting activated hepatic stellate cells. ACS Nano 17, 14852–14870 (2023).

Sumida, K. et al. IL-11 induces differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells through activation of STAT3 signalling pathway. Sci. Rep. 5, 13650 (2015).

Xiong, W. et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of IL11/STAT3 signaling increases MHC-I expression and T cell infiltration. J. Transl. Med. 21, 416 (2023).

Putoczki, T. L. et al. Interleukin-11 is the dominant IL-6 family cytokine during gastrointestinal tumorigenesis and can be targeted therapeutically. Cancer Cell 24, 257–271 (2013).

Huynh, J. et al. The JAK/STAT3 axis: a comprehensive drug target for solid malignancies. Semin. Cancer Biol. 45, 13–22 (2017).

Batlle, E. & Massagué, J. Transforming growth factor-β signaling in immunity and cancer. Immunity 50, 924–940 (2019).

Principe, D. R. et al. TGF-β: duality of function between tumor prevention and carcinogenesis. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 106, djt369 (2014).

Anderton, M. J. et al. Induction of heart valve lesions by small-molecule ALK5 inhibitors. Toxicol. Pathol. 39, 916–924 (2011).

Mitra, M. S. et al. A potent Pan-TGFβ neutralizing monoclonal antibody elicits cardiovascular toxicity in mice and cynomolgus monkeys. Toxicol. Sci. 175, 24–34 (2020).

Lee, C. G. et al. Endogenous IL-11 signaling is essential in Th2- and IL-13-induced inflammation and mucus production. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 39, 739–746 (2008).

Melsted, P. et al. Modular, efficient and constant-memory single-cell RNA-seq preprocessing. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 813–818 (2021).

Lun, A. T. L. et al. EmptyDrops: distinguishing cells from empty droplets in droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 20, 63 (2019).

Wolock, S. L., Lopez, R. & Klein, A. M. Scrublet: computational identification of cell doublets in single-cell transcriptomic data. Cell Syst. 8, 281–291.e9 (2019).

Wolf, F. A., Angerer, P. & Theis, F. J. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 19, 15 (2018).

Korsunsky, I. et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods 16, 1289–1296 (2019).

Jiang, S. et al. Cell Taxonomy: a curated repository of cell types with multifaceted characterization. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D853–D860 (2023).

van der Leun, A. M., Thommen, D. S. & Schumacher, T. N. CD8(+) T cell states in human cancer: insights from single-cell analysis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 218–232 (2020).

Chu, Y. et al. Pan-cancer T cell atlas links a cellular stress response state to immunotherapy resistance. Nat. Med. 29, 1550–1562 (2023).

Andreatta, M. & Carmona, S. J. UCell: robust and scalable single-cell gene signature scoring. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 3796–3798 (2021).

La Manno, G. et al. RNA velocity of single cells. Nature 560, 494–498 (2018).

Bergen, V. et al. Generalizing RNA velocity to transient cell states through dynamical modeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1408–1414 (2020).

Schubert, M. et al. Perturbation-response genes reveal signaling footprints in cancer gene expression. Nat. Commun. 9, 20 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Mabwell (Shanghai) Bioscience Co., Ltd. We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by colleagues at Mabwell (Shanghai) Bioscience Co., Ltd. Thanks for the support on the drug efficacy study in vivo by Yicon(Beijing) BioMedical Technology Inc. Thanks for the support on ScRNA-seq data analysis by Precision Scientific (Beijing) Co., Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W. and X.G. are co-corresponding authors and each has a significant contribution to this work. S.W. and X.G.: conception and design. C.Z.: development of methodology. C.Z., R.W., D.Z., W.J., S.J., B.Z., and M.W.: acquisition of data (provided animals, provided facilities, etc.). C.Z. and S.J.: analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis). W.J., S.J., S.W., and X.G.: writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript. C.Z. and R.W.: material support. S.W: study supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.Z., S.J., W.J., R.W, M.W., B.Z., S.W., and X.G. are employees of Mabwell (Shanghai) Bioscience Co., Ltd, and may hold shares in Mabwell (Shanghai) Bioscience Co., Ltd, suggesting a financial interest in the outcomes of the research. No competing interests were declared by the other authors, indicating that beyond their employment, they do not have any additional financial stakes that could be perceived as influencing the research outcomes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Jiao, S., Zeng, D. et al. IL-11/IL-11R signal inhibition by 9MW3811 remodels immune tumor microenvironment and enhances anti-tumor efficacy of PD-1 blockade. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 138 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00913-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00913-w

This article is cited by

-

Circulating IFNγ-associated protein signatures predict response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with stage III melanoma

Cancer Cell International (2025)