Abstract

KRAS mutations drive pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) progression. This study investigates molecular heterogeneity among KRAS subtypes and their prognostic implications. This study explores KRAS mutations in PDAC, analyzing molecular heterogeneity and prognosis across our hospital cohort (SDFM, n = 113) with TCGA cohort (n = 183) and QCMG cohort (n = 383). KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4 were the main mutated genes. Co-mutations of KRAS with TP53, and TP53 with CDKN2A, correlated with higher tumor mutation burden and poorer outcomes. KRAS subtypes G12D and Q16&others had worse prognosis than G12V and G12R. Combining TP53 status with KRAS subtypes improved risk stratification: high-risk patients had shorter survival (P ≤ 0.001), higher PD-L1 expression, P53 pathway alterations, fewer CD4+/CD8 + T cells and macrophages (p < 0.05), but more neutrophils (p < 0.001). These findings underscore the prognostic impact of KRAS and TP53 mutations, guiding personalized treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, pancreatic cancer is the 12th most common cancer, and the seventh leading cause of cancer-related deaths1. In Asia, the incidence of pancreatic cancer is increasing2. Pancreatic cancer is notorious for its high degree of malignancy. Due to the lack of distinctive clinical symptoms and early diagnostic tools, many patients are diagnosed at late stages of the disease, leading to poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of only 10%3,4,5. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common type of pancreatic cancer, accounting for approximately 85% of all types of pancreatic cancer. The advancement of molecular diagnostics has enabled researchers to gradually pinpoint targets for treating PDAC, including KRAS6,7,8.

KRAS mutations are the most prevalent genetic alterations in PDAC, occurring in approximately 90% of cases9,10. However, the specific molecular structure of KRAS results in its low drug ability. Cancer-associated mutations in KRAS cluster in one of three hotspots, with a majority (84%) of mutations causing single amino acid substitutions at G1211. Of the possible single-base missense mutations that can occur at G12, G12D is the most predominant (42%), followed by G12V. Currently, Adagrasib6,7 and Sotorasib8 can be used for targeted therapy in PDAC patients with the KRAS G12C mutation. However, as G12C mutations are relatively low, this means that the majority of PDAC patients with G12D and G12V mutations face a lack of targeted therapies. In a recent cohort study from MDA, the overall positive rate of KRAS mutations was 82%, with the most common mutation being KRAS G12D (39%), followed by KRAS G12V (31%), KRAS G12R (14%), KRAS Q61 (6%), and other rarer KRAS variants (9%)12. In terms of prognosis, patients with KRAS G12D or KRAS Q61 mutations have a lower survival rate compared to KRAS wild-type patients, regardless of disease stage. The overall survival of patients with KRAS G12R mutations is similar to that of wild-type patients. Other studies have also indicated that different KRAS mutations have varying impacts on prognosis13,14.

Considering the significant roles of KRAS in PDAC, we conducted analyses to examine the influence of KRAS mutations on the molecular characteristics of patients. Our study aimed to provide new insight into KRAS mutations and the development of PDAC. These findings will provide a theoretical foundation for future research on targeted treatments for PDAC

Results

Mutation overview and analysis

To characterize the mutational landscape of PDAC, we analyzed genomic profiles from three independent cohorts. Consistent with the known molecular architecture of PDAC9, KRAS and TP53 were the most commonly mutated genes across all datasets (SDFM, TCGA, QCMG), followed by CDKN2A and SMAD4 (Fig. 1A–C). Statistically significant co-occurrence was observed between KRAS and TP53, as well as between TP53 and CDKN2A (p < 0.05 in all cohorts; Fig. 1A–C).

The mutation landscape and co-mutation patterns of the top 20 genes in pancreatic cancer patients were analyzed across three distinct cohorts: 113 patients from the SDFM cohort (A), 183 patients from the TCGA cohort (B), and 383 patients from the QCMG cohort (C); Additionally, in all three cohorts, PDAC patients with mutations in KRAS, TP53, and CDKN2A exhibited significantly higher TMB values compared to those with wild-type alleles (P < 0.01), whereas no significant correlation was observed for SMAD4 mutations (D–F).

Mutations in KRAS, TP53, and CDKN2A were consistently associated with significantly elevated TMB compared to their respective wild-type groups across all cohorts (p < 0.05; Fig. 1D–F and Table S1), whereas SMAD4 mutations were not significantly associated with TMB. Despite these associations, overall TMB levels remained low, with mean values ranging from 0.86 to 3.13 mutations per megabase (Table S1).

Survival analysis based on mutation analysis

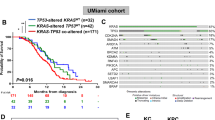

To investigate the impact of KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4 mutations on prognosis, we conducted a univariate regression analysis of OS using the TCGA cohort data. The results are depicted in Fig. 2A. Factors such as age, KRAS, and TP53 mutations showed significant associations with overall survival (OS) (p < 0.05). In the multivariate regression analysis (Fig. 2B), only KRAS mutation and age remained significant factors (p < 0.05). Detailed information on regression analysis is provided in Table S2. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed mutations in KRAS and TP53 were significantly associated with both poorer OS and progression-free survival (PFS) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2C, D). Combined KRAS and TP53 mutations result in the worst survival outcomes (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2E). However, no significant difference in OS or PFS between PDAC patients aged <65 and those aged ≥65 (Fig. S2).

A Univariate Cox regression analysis identified Stage II (HR = 2.42, p = 0.026), KRAS mutation (HR = 0.44, p < 0.001), and TP53 mutation (HR = 0.59, p = 0.014) as significant factors for overall survival (OS); B Multivariate analysis highlighted age (HR = 1.026, p = 0.011) and KRAS mutation (HR = 0.571, p = 0.028) as independent prognostic factors; C–E Kaplan–Meier survival analyses demonstrated: KRAS mutations are associated with worse outcomes in both OS (p = 0.00032) and PFS (p = 0.01); TP53 mutations predict poorer survival compared to wild-type (OS: p = 0.013, PFS: p = 0.0056); combined KRAS and TP53 mutations result in the worst survival outcomes (OS: p = 0.0023, PFS: p = 0.011) in TCGA cohort.

Survival analysis of PDAC patients with KRAS mutation

In our genetic mutation prognosis analysis, we further differentiated KRAS mutations. Figure 3A shows that the KRAS G12D, G12V, and G12R mutations were predominant across all three cohorts, followed by KRAS Q61 and other mutations. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses on the TCGA cohort with KRAS mutations (Table 1) revealed that the G12D, Q61, and other mutations were associated with a worse prognosis compared to the G12V mutation subgroup. Notably, the Q61 and other mutations were statistically significant (P < 0.05). However, analysis of clinical characteristics and driver gene mutations across the three cohorts (Tables S3–S5) showed no significant differences in age, gender, tumor stage, TP53, CDKN2A, SMAD4 mutations, TMB, and MSI (Fig. S1). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis indicated that the KRAS G12D, Q61, and other mutations had a worse prognosis, while G12R and G12V mutations had the highest median OS or PFS (Fig. 3B). Further analysis of TP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4 mutations within KRAS subgroups showed no inter-group differences in TP53 (Fig. 3C), CDKN2A (Fig. S3A), or SMAD4 (Fig. S4A). However, TP53 mutations were significantly more prevalent in the KRAS G12D and Q61&other mutation subgroups compared to other KRAS mutations (p < 0.05) across all three cohorts.

A Bar charts illustrating the distribution of KRAS mutation subtypes (G12D, G12V, G12R, Q61X, and other KRAS mutations) in the SDFM (n = 113), TCGA (n = 183), and QCMG cohorts (n = 383); B Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing OS and PFS stratified by KRAS mutation subtypes in TCGA cohort; C Bar charts representing the proportion of TP53 mutation status within each KRAS mutation subtype across the three cohorts; D, E Kaplan–Meier survival curves illustrating OS and PFS for KRAS mutation subtypes (G12D, G12V, G12R) in TP53 mutation and TP53 wildtype groups.

Prognostic analysis (Fig. S5) revealed that TP53 mutations do not significantly impact prognosis in cases with KRAS G12D mutations. In contrast, KRAS G12V mutation is associated with poorer prognosis in TP53-mutant patients, while TP53 wild-type patients show relatively better outcomes. Conversely, an opposite trend was observed in KRAS G12R mutation cases. Further analysis of KRAS mutation subtypes in TP53-mutant patients demonstrated that KRAS G12R mutation is associated with significantly better prognosis compared to other subtypes (Fig. 3D, P < 0.01). In TP53 wild-type patients, KRAS G12V mutation was linked to a relatively better prognosis (Fig. 3E). Notably, patients with both KRAS G12R and TP53 mutations showed survival outcomes similar to those with wild-type KRAS, while KRAS G12V mutation in TP53 wild-type patients (Fig. S6). Conversely, no clear patterns were observed in prognosis analyses based on CDKN2A (Fig. S3B–F) and SMAD4 (Fig. S4B–F).

Survival value with risk status and relevant differential expressive gene analysis

In light of these observations, we categorized PDAC patients into high- or low-risk cohorts based on their KRAS and TP53 mutation status, as delineated below: Those with KRAS G12D or KRAS G12V mutations co-occurring with TP53 mutations, as well as those with KRAS G12R mutations co-occurring with TP53 wild-type or KRAS Q61 and other mutations, were designated as high-risk. Meanwhile, patients with KRAS wild-type, KRAS G12V mutations co-occurring with TP53 wild-type, and KRAS G12R mutations co-occurring with TP53 mutations were classified as low-risk individuals. Based on this risk stratification, we conducted a prognostic analysis in TCGA and MSK cohorts. As illustrated in Figs. 4A and S7, high-risk PDAC patients demonstrated significantly shorter median OS, PFS, DFS (disease free survival), and DSS (disease free survival) compared to low-risk patients in TCGA cohort (p ≤ 0.0001). Multivariate regression analysis further identified high-risk status as an independent predictor of poor prognosis (Fig. 4B). The prognostic analysis of the MSK cohort further validated that risk stratification based on KRAS mutation status is a reliable predictor of outcomes in PDAC patients (Fig. S8).

Kaplan–Meier plot of OS and PFS with risk status and validation with MSK cohort (n = 2270) (A); multivariate regression analysis of the association between overall survival and risk status in patients (B); the heatmap of gene differential expression profile between risk status (C); the volcano map of gene up or downregulation in the high and low-risk group (D); Bar graph of the GO enrichment analysis results in high-risk group (E); Enrichment analysis plot of differential expression gene (F).

To understand the potential mechanisms underlying these prognostic differences, we conducted a gene differential analysis. As depicted in the heatmap (Fig. 4C), the gene expression profiles of high-risk patients show obvious differences compared to low-risk patients. Specifically, high-risk patients exhibit a marked upregulation of genes compared to low-risk patients (232 vs 26, Fig. 4D). As shown in Fig. 4E, GO enrichment analysis revealed that, in terms of Biological Processes, genes upregulated in high-risk patients were significantly enriched in pathways related to epidermis development, skin development, cornification, epidermal cell differentiation, and keratinization. Regarding Cellular Components, highly enriched categories included the intermediate filament cytoskeleton, anchored components of the membrane, membrane components, intermediate filaments, and lipid droplets. For Molecular Functions, the upregulated genes were predominantly associated with retinol dehydrogenase activity, signal receptor ligand activity, serine-type endopeptidase activity, serine-type peptidase activity, and extracellular matrix structural constituents. Furthermore, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (Fig. 4F) identified significant enrichment in key signaling pathways, including retinol metabolism, estrogen signaling, and PPAR signaling. Collectively, these findings suggest that the gene expression profile of high-risk patients is marked by the activation of pathways related to epidermal development, cytoskeletal organization, and signal transduction.

Analysis of tumor signaling pathways with risk status

To further investigate the underlying mechanisms, we conducted a differential mutation analysis of oncogenic signaling pathways. In the SDFM cohort, high-risk patients exhibited a higher TP53 pathway mutation rate (96.2% vs. 67.86%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5A and Table S6). In the TCGA cohort, high-risk patients showed higher mutation rates in TP53 (96.2% vs. 67.86%, p < 0.001), Cell Cycle (34.07% vs. 5.95%, p < 0.001), TGF-Beta (32.97% vs. 19.05%, p < 0.05), and Hippo (29.67% vs. 16.67%, p < 0.05) signaling pathways (Fig. 5B and Table S6). In the QCMG cohort, high-risk patients exhibited higher mutation rates in TP53 (76.23% vs. 51.28%, p < 0.001) and WNT (21.13% vs. 8.55%, p < 0.01) signaling pathways (Fig. 5C and Table S6). The corresponding pathway mutation profiles are shown in Fig. 5D–F. The three cohorts exhibited significant differences in the TP53 pathway, consistent with the analysis of clinical characteristics and driver mutation status between high-risk and low-risk groups (Tables S7–S9).

A–C Bar plots showing the proportion of tumor signaling pathway mutations in high-risk and low-risk groups across three cohorts: SDFM, TCGA, and QCMG. Statistical significance between the groups was assessed using the Wilcoxon test, where “”, “”, and “” represent P < 0.05, P < 0.011, and P < 0.001, respectively. Exploratory analyses with FDR-adjusted p-values in Supplementary Table S6, see “Methods” for analysis definitions; D–F Heatmaps showing the mutation profiles of pathway-related genes for high-risk and low-risk groups in the three cohorts.

Analysis of PD-L1 expression and immune infiltration with risk status

We further analyzed the association between mutations in KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4 with PD-L1 expression levels. When setting the threshold of PD-L1 expression using TPS at 1%, a significantly higher proportion of PD-L1 positivity was observed in patients with PDAC harboring KRAS or TP53 mutations compared to wild-type cases, with the increase being particularly pronounced in TP53-mutated patients (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A, B). Similarly, a higher proportion of PD-L1 positive cases was noted in the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 6C). When the TPS threshold was gradually increased to 5% and 10%, a similar distribution trend in PD-L1 expression was consistently observed (Fig. S9). Notably, the trend appeared more prominent at the 5% threshold, suggesting a degree of stability in the observed association (Table S10). However, when the threshold was further increased to 50%, these differences in distribution became less evident (Table S10). In contrast, mutations in CDKN2A and SMAD4 showed no significant impact on PD-L1 expression across all threshold settings (1%, 5%, or 10%) (Fig. S9). Moreover, we found no significant correlation between PD-L1 expression and TMB levels (Fig. 6D and Table S10).

A–C Bar charts displaying the proportion of PD-L1 expression (TPS ≥ 1%) stratified by KRAS mutation status, TP53 mutation status, and risk status in SDFM cohort (n = 113). Statistical significance was evaluated using the Chi-square test, and p-values are indicated; D Correlation analysis between TMB and PD-L1 expression. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (R) and corresponding p-value are shown; E–H The expression levels of immune checkpoint genes (CD274, CTLA4, and PDCD1), ESTIMATE scores, TIMER immune infiltration scores, and QUANTISEQ scores between low-risk (blue) and high-risk (red) groups in TCGA cohort, “*”, “**”, and “***” indicate P < 0.05, P < 0.011, and P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Exploratory analyses with FDR-adjusted p-values in Supplementary Table S11, see “Methods” for analysis definitions.

Through the analysis of TCGA transcriptome data, it was found that the mRNA expression level of CD274 was higher in high-risk patients compared to the low-risk group, while the mRNA expression levels of CTLA4 and PDCD1 were lower, although the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 6E). However, we found the expression levels of CD3(composed of CD3D, CD3E, and CD3G subunits) and CD8 (composed of CD8A and CD8B subunits) were markedly elevated in the low-risk group relative to the high-risk group (Fig. S10). The ESTIMATE immune scoring analysis showed that the immune scores (including StromalScore, ImmuneScore, and ESTIMATEScore) of high-risk patients were significantly lower than those of the low-risk group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6F and Table S11). Further analysis of immune infiltration levels between the two groups using TIMER (Fig. 6G) and QUANTISEQ (Fig. 6H) revealed that the infiltration levels of CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells were significantly lower in the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group (P < 0.05) (Table S11). However, QUANTISEQ analysis also found that the infiltration levels of Tregs and M2 macrophages were significantly lower in the high-risk group (P < 0.05), while the infiltration levels of M1 macrophages and neutrophils were significantly higher than those in the low-risk group (P < 0.05) (Table S11).

Discussion

KRAS mutations are a key event in pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC). In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of KRAS mutations and their subtypes in the SDFM cohort, and performed parallel validation in the TCGA and QCMG cohorts. Consistent with previous studies12, we identified KRAS, TP53, SMAD4, and CDKN2A mutations as the most common driver mutations in PDAC across all three cohorts. Additionally, KRAS mutations frequently co-occur with TP53 mutations, which in turn often co-occur with CDKN2A mutations. Prognostic analyses have shown that KRAS mutations and TP53 mutations are associated with poorer prognosis, which is consistent with earlier research on PDAC15,16. A preclinical study suggested that KRAS and TP53 mutations synergistically promote PDAC growth and metastasis through interactions with CREB117, potentially explaining the poor prognosis associated with these mutations. Additionally, KRAS, TP53, and CDKN2A mutations correlate with higher TMB, which is considered a key factor in generating immune neoantigens18. However, despite this correlation, TMB did not show a significant link to PDAC prognosis in this study. Most patients had TMB values below the clinical threshold for TMB-H (10 mutations/Mb), indicating that the role of TMB and these mutations in prognosis and treatment warrants further exploration.

Our study found that the proportion of KRAS wild-type mutations is approximately 10%, and the prognosis is better than that of KRAS mutant types, which is consistent with previous research19. The analysis of KRAS mutation subtypes in PDAC patients aligns with previous studies11,12, showing KRAS G12D, G12V, and G12R as the most common, followed by Q61 and other rare mutations. Among them, G12D, Q61, and other mutations are linked to shorter PFS and OS, while G12V and G12R mutations are associated with better prognosis. This finding is consistent with the research conducted by MD Anderson Cancer Center12,20. The prognosis differences among G12D, Q61, G12V, and G12R mutations may stem from their distinct effects on KRAS protein function and the activation of downstream signaling pathways. The G12D/Q61 mutations may enhance RAF/MEK/ERK signaling21 or create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment22,23, promoting tumor proliferation, survival, and invasion. Spatial profiling reveals revealed elevated oncogenic signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in G12D tumors, whereas G12R tumors exhibited increased nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling20.

Given the high prevalence of TP53 mutations across all KRAS subtypes, with mutation rates exceeding 60%, particularly in the G12D, Q61, and other mutant subtypes, we further explored the relationship between specific KRAS mutations and TP53 alterations. Our analysis reveals, for the first time, that TP53 mutation status may impact the prognosis of patients with certain KRAS mutation subtypes. As previously reported24, the KRAS G12D mutation is associated with poorer survival outcomes, both independently and in combination with TP53 mutations. In contrast, for KRAS G12V subtype, those with the TP53 wild-type tend to have a longer survival than those with TP53 mutations. TP53 mutations are linked to worse OS in various cancers, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC)20, likely due to TP53’s critical role in tumor suppression and DNA repair. Mutations in TP53 lead to uncontrolled cell cycle progression and accumulation of DNA damage, exacerbating tumor malignancy. Research by Zou et al. suggests that KRAS G12D and TP53 co-mutation patients exhibit a low Th1/Th2 ratio and an immunosuppressive microenvironment (high Treg, high ratio of Treg to tumor-specific CD4 + T cell), while KRAS G12V and TP53 wild-type patients show a more inflammatory microenvironment and significant survival improvement following adjuvant chemotherapy25. Based on KRAS mutation subtypes and TP53 mutation status, PDAC patients are categorized into high-risk and low-risk groups. The low-risk group, including some patients with specific KRAS G12V and G12R mutations, exhibits significantly better prognosis, as confirmed in the large-scale MSK PDAC cohort10. Pathway enrichment analysis reveals that mutations in high-risk patients are primarily concentrated in TP53 and cell cycle-related pathways, with a particularly high co-occurrence rate of KRAS and TP53 mutations. Previous studies have demonstrated a synergistic effect between KRAS and TP53 mutations in the development and metastasis of pancreatic cancer17,26. TP53 mutations cause abnormal exon retention, upregulating hnRNPK, which promotes GAP17 membrane localization and sustains Ras signaling, driving tumorigenesis27. These findings underscore the importance of considering TP53 mutation status when treating KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer, underscoring the need for risk stratification.

IHC analysis of PD-L1 protein expression is a critical biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response. Studies consistently show that high PD-L1 expression in PDAC is associated with a poorer prognosis28,29,30. Notably, patients exhibiting PD-L1 expression levels of ≥10%, as assessed using the anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody SP142, demonstrated significantly reduced disease-specific survival, as reported by Tessier-Cloutier et al.30 Our findings further demonstrate that PD-L1 positivity is more frequently observed in PDAC patients carrying KRAS or TP53 mutations, particularly those with TP53 mutations, and classified in the high-risk group. Notably, the most pronounced difference in PD-L1 expression distribution was observed when a TPS threshold of 5% was applied. These results suggest that PD-L1 positivity or upregulation may contribute to the poor prognosis observed in these patients; however, further data are required to substantiate this association. In immune infiltration analysis, low-risk patients show higher levels of CD4/CD8 T cells and Treg cells, which correlate with better prognosis across various cancers31,32. CD4 + T cells activate CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, playing a vital role in anti-tumor immunity33,34. However, in high-risk PDAC patients, reduced CD4 + T cell infiltration weakens CD8 + T cell function, diminishing anti-tumor responses and worsening prognosis. We also observed higher neutrophil infiltration in high-risk PDAC patients, which has been linked to increased malignancy and poorer prognosis35. KRAS and TP53 mutations, common in high-risk PDAC, are associated with a higher density of immunosuppressive myeloid cells like MDSCs and Tregs, which inhibit CD4 + Th1 and CD8 + T cell activity, creating an immune-tolerant microenvironment36. TP53 mutations increase CD8 + T cell density, but this effect is influenced by other mutations37. KRAS mutations, in particular, enhance Treg conversion and suppress CD8 + T cell anti-tumor activity38,39. Furthermore, KRAS mutations elevate PD-L1 expression, contributing to immune suppression and tumor progression40,41. Interestingly, tumors with both KRAS and TP53 mutations exhibit higher PD-L1 levels, which have been associated with better immunotherapy outcomes42,43, highlighting the complex interplay between genetic mutations and immune responses in PDAC prognosis.

This study has several limitations. First, although PDAC patients were included, the sample size was small, and detailed pathological staging data were unavailable. To mitigate this, two external PDAC cohorts were analyzed. However, some cohorts lacked complete clinical and prognostic data, with notable imbalances in pathological stage distribution. Future studies should focus on larger, well-characterized cohorts with balanced clinical profiles for validation. Additionally, the unmeasured treatment modality and performance status may affect the clinical generalizability of the risk stratification. Future prospective studies should incorporate these factors to refine the prognostic model. Second, this study’s SDFM cohort utilized a 639-gene panel to detect mutations and calculate TMB, rather than WES, which might have some impact on the mutation profile and TMB calculation, although the results are quite similar to those of TCGA and QCMG. Also, our study primarily focuses on molecular subtyping based on mutational profiles, without in-depth analysis of transcriptomic or proteomic data. Due to practical constraints, key transcriptional features of pancreatic cancer subtypes, such as the classical and basal-like types, were not included. Third, although we conducted prognostic validation using large-scale cohorts, we did not account for the impact of postoperative adjuvant therapy or systemic treatment, which may significantly influence survival outcomes. The absence of treatment factors could limit the generalizability of our findings. Therefore, future studies should incorporate these treatment variables into the analysis to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of their potential effects on prognosis. Lastly, the results of the mechanistic analysis are based solely on the characteristics of the study cohort and require further validation. Therefore, future studies should validate these observations in larger cohorts and explore the functional significance of the identified molecular changes, with the aim of providing a more robust scientific foundation for the management and prognosis improvement of pancreatic cancer patients.

In conclusion, the aforementioned findings provide a comprehensive analysis of the complex molecular landscape of pancreatic cancer, with a particular focus on the critical roles of different KRAS mutation subtypes and TP53 mutations in patient prognosis. The risk stratification and immune infiltration analysis based on these findings could offer significant insights for personalized treatment strategies in PDAC, helping to identify patient subgroups that may benefit from targeted or immunotherapy treatments.

Methods

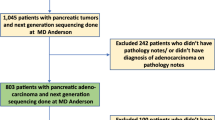

Patient and sample characteristics

This study included 113 patients diagnosed with PDAC, confirmed through pathological evaluation, and enrolled between June 2021 and December 2023 at Shandong Cancer Hospital, constituting the SDFM cohort. To minimize potential confounders and ensure data accuracy, patients who had previously received anti-RAS inhibitors or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) were excluded, as these treatments could alter the tumor microenvironment and mutation profiles. Additionally, inclusion was limited to patients with both tumor tissue and paired blood samples available for genetic analysis. Tumor tissue specimens, obtained via surgical resection or biopsy, were required to contain at least 20% tumor cells to ensure the reliability of genetic testing. Rigorous exclusion criteria were applied to maintain the integrity of the study. Patients without a confirmed PDAC diagnosis, those lacking either tumor tissue or paired blood samples, or those with tumor samples containing less than 20% tumor cells, were excluded to guarantee that the genetic analyses were based on high-quality, representative tumor specimens. Clinical data, including patient age and gender, were retrieved from medical records. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review board of Shandong Cancer Hospital (SDTHEC2023011024) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

DNA extraction and library construction

Tumor DNA and peripheral blood genomic DNA were extracted using commercial kits from YunYing (Shanghai, China), specifically the Human Tissue DNA Extraction Kit and the Human Blood Genomic DNA Extraction Kit, respectively, following the manufacturer’s protocols. DNA was eluted in the provided elution buffer, and its concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. All DNA samples were stored at −20 °C until further processing.

Library preparation was carried out using the VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Targeted enrichment was performed using proprietary probes optimized by Shanghai YunYing, which cover the exonic regions and selected intronic sequences of 639 cancer-associated genes (see Table S12 for full gene list)44. Sequencing was conducted on an Illumina NextSeq500 platform using standard protocols.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based assay and bioinformatics analysis

FastQC software (version 0.11.2) and customized Python script were used to screen FASTQ files, with the adaptor sequences and sequences with Q below 30 removed. Clean reads were mapped to the reference human genome GRCh37/hg19 using BWA (Burrows Wheeler Aligner version 0.7.7). BAM files were then realigned and recalled using GATK3.545, which was also used to detect mutations. Duplicate sequences were removed using Picard MarkDuplicates (version 1.35) to reduce any potential polymerase chain reaction bias. VarScan (version 2.3.2)46 was used to select single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) satisfying the following criteria: depth ≥ 100, reads ≥ 10, and allele frequency ≥ 5% (if hotspot, ≥ 1%). Pindel (version 0.2.5b8)47 was used for insertion or deletion (indel) detection using default parameters, with at least 5 unique reads.

Compared with matched normal samples, somatic SNVs and InDels of tumors were named and functionally annotated using MuTect v. 1.1.4 and Varscan2 v. 2.3.9 software. Mutations with a variant allele frequency of ≥5% were defined as high-confidence mutations (≥1% for hotspots). Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was calculated using the number of all somatic, coding, base substitution, and indel mutations per megabase, including synonymous mutations. The total number of mutations counted was divided by the size of the coding region of the targeted territory (1.36 Mb of the coding genome) to calculate the TMB per megabase. Microsatellite instability (MSI) scores of all samples were calculated using MSIsensor48 with default parameters, a software tool for quantifying MSI in genome sequencing data using tumor-only or paired tumor-normal samples. We used 29 microsatellite sites as input files for MSI detection of tumor-only patterns. The MSI score was defined as the percentage of unstable microsatellites among all microsatellites used. Each microsatellite site had at least 20 spanning reads and single-nucleotide mutations.

PD-L1 expression test

The PD-L1 expression level for each patient was determined using the Dako 22C3 pharmDx system (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) assay, and the results are presented as a tumor proportion score (TPS)49.

Data collection and statistical analysis

This study utilized two external validation groups for comparative analysis with the SDFM cohort: 184 PDAC patients from the TCGA cohort and 383 PDAC patients from the QCMG cohort, all of which have comprehensive genetic mutation data. These cohorts served as parallel groups for comparative analysis within the SDFM cohort (detailed clinical information see in Table S13). The data were sourced from the publicly available cBioPortal database (https://www.cbioportal.org/datasets). Among them, 116 KRAS-mutant patients from the TCGA cohort were analyzed for survival outcomes across different groups. Additionally, a large validation cohort (MSK cohort, comprising 2270 patients with survival data) was used to validate subsequent risk stratification10. We used the survfit function from the R package “survival” to analyze the differences in prognosis between different groups of samples. We then assessed the difference in gene expression between the groups using the limma method in the Sangerbox platform50,51,52 (http://www.sangerbox.com/tool, a free online platform for comprehensive data analysis).

The prevalence and distribution of genomic alterations were visualized using the R package “maftools”53. The “IOBR” package is used for immune infiltration analysis54. The R package “ggplot2” was used to draw the boxplots. The nonparametric Wilcox test was subsequently used to test for the significance of the difference in means between the two populations. For exploratory post hoc comparisons, multiple testing adjustments were performed using the FDR to control the false discovery rate.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Abbreviations

- PDAC:

-

pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- KRAS:

-

Kirsten Rat Sarcoma

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed Death-Ligand 1

- TP53:

-

Tumor Protein 53

- TPS:

-

Tumor Proportion Scores

- TMB:

-

Tumor Mutational Burden

- MSI:

-

MicroSatellite Instability

- OS:

-

Overall Survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-Free Survival

- TGF-Beta:

-

Transforming Growth Factor-Beta

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424 (2018).

Collaborators, G. P. C. The global, regional, and national burden of pancreatic cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4, 934–947 (2019).

Maisonneuve, P. & Lowenfels, A. B. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: an update. Dig. Dis. 28, 645–656 (2010).

Wood, L. D. et al. Pancreatic cancer: pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 163, 386–402.e1 (2022).

Cai, J. et al. Advances in the epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: trends, risk factors, screening, and prognosis. Cancer Lett. 520, 1–11 (2021).

Bekaii-Saab, T. S. et al. Adagrasib in advanced solid tumors harboring a KRAS(G12C) mutation. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 4097–4106 (2023).

Rose, S. Adagrasib moving ahead in GI cancers. Cancer Discov. 12, 590–591 (2022).

Hong, D. S. et al. KRAS(G12C) inhibition with sotorasib in advanced solid tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1207–1217 (2020).

The-Cancer-Genome-Atlas-Research-Network Integrated genomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 32, 185–203.e13 (2017).

Varghese, A. M. et al. Clinicogenomic landscape of pancreatic adenocarcinoma identifies KRAS mutant dosage as prognostic of overall survival. Nat. Med. 31, 466–477 (2025).

Cox, A. D. et al. Drugging the undruggable RAS: mission possible? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 828–851 (2014).

Yousef, A. et al. Impact of KRAS mutations and co-mutations on clinical outcomes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 27 (2024).

Diehl, A. C. et al. KRAS mutation variants and co-occurring PI3K pathway alterations impact survival for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Oncologist 27, 1025–1033 (2022).

Lee, J. K. et al. Comprehensive pan-cancer genomic landscape of KRAS altered cancers and real-world outcomes in solid tumors. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 6, 91 (2022).

Kim, S. T. et al. Impact of KRAS mutations on clinical outcomes in pancreatic cancer patients treated with first-line gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. Mol. Cancer Ther 10, 1993–1999 (2011).

Nakano, Y. et al. KRAS mutations in cell-free DNA from preoperative and postoperative sera as a pancreatic cancer marker: a retrospective study. Br. J. Cancer 118, 662–669 (2018).

Kim, M. P. et al. Oncogenic KRAS recruits an expansive transcriptional network through mutant p53 to drive pancreatic cancer metastasis. Cancer Discov. 11, 2094–2111 (2021).

Schumacher, T. N. & Schreiber, R. D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 348, 69–74 (2015).

Singh, H. et al. Oncogenic drivers and therapeutic vulnerabilities in KRAS wild-type pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 4627–4643 (2023).

McIntyre, C. A. et al. Distinct clinical outcomes and biological features of specific KRAS mutants in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 42, 1614–1629.e5 (2024).

Hunter, J. C. et al. Biochemical and structural analysis of common cancer-associated KRAS Mutations. Mol. Cancer Res. 13, 1325–1335 (2015).

Hou, P. et al. Tumor microenvironment remodeling enables bypass of oncogenic KRAS Dependency in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 10, 1058–1077 (2020).

Dey, P. et al. Oncogenic KRAS-driven metabolic reprogramming in pancreatic cancer cells utilizes cytokines from the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 10, 608–625 (2020).

McIntyre, C. A. et al. Alterations in driver genes are predictive of survival in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer 126, 3939–3949 (2020).

Zou, S. et al. Driver mutation subtypes involve with differentiated immunophenotypes influencing pancreatic cancer outcomes. Cancer Lett. 599, 217134 (2024).

Bailey, J. M. et al. p53 mutations cooperate with oncogenic Kras to promote adenocarcinoma from pancreatic ductal cells. Oncogene 35, 4282–4288 (2016).

Escobar-Hoyos, L. F. et al. Altered RNA splicing by mutant p53 activates oncogenic RAS signaling in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 38, 198–211.e8 (2020).

Soares, K. C. et al. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade together with vaccine therapy facilitates effector T-cell infiltration into pancreatic tumors. J. Immunother. 38, 1–11 (2015).

Yamaki, S. et al. PD-L1 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is a poor prognostic factor in patients with high CD8(+) tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: highly sensitive detection using phosphor-integrated dot staining. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 726–733 (2017).

Tessier-Cloutier, B. et al. Programmed cell death ligand 1 cut-point is associated with reduced disease specific survival in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 17, 618 (2017).

Öjlert, ÅK. et al. The immune microenvironment in non-small cell lung cancer is predictive of prognosis after surgery. Mol. Oncol. 13, 1166–1179 (2019).

Zeng, D. et al. Tumor microenvironment characterization in gastric cancer identifies prognostic and immunotherapeutically relevant gene signatures. Cancer Immunol. Res. 7, 737–750 (2019).

Borst, J. et al. CD4(+) T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 635–647 (2018).

Kruse, B. et al. CD4(+) T cell-induced inflammatory cell death controls immune-evasive tumours. Nature 618, 1033–1040 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Neutrophils infiltrating pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma indicate higher malignancy and worse prognosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 501, 313–319 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. Unveiling the role of KRAS in tumor immune microenvironment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 171, 116058 (2024).

Biton, J. et al. TP53, STK11, and EGFR mutations predict tumor immune profile and the response to anti-PD-1 in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 5710–5723 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Impact of KRAS mutation on the tumor microenvironment in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 20, 1947–1964 (2024).

Mahadevan, K. K. et al. Elimination of oncogenic KRAS in genetic mouse models eradicates pancreatic cancer by inducing FAS-dependent apoptosis by CD8(+) T cells. Dev. Cell 58, 1562–77.e8 (2023).

Coelho, M. A. et al. Oncogenic RAS signaling promotes tumor immunoresistance by stabilizing PD-L1 mRNA. Immunity 47, 1083–1099.e6 (2017).

Canon, J. et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature 575, 217–223 (2019).

Dong, Z. Y. et al. Potential predictive value of TP53 and KRAS mutation status for response to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 3012–3024 (2017).

Budczies, J. et al. KRAS and TP53 co-mutation predicts benefit of immune checkpoint blockade in lung adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 131, 524–533 (2024).

Ding, W. et al. Unraveling EGFR-TKI resistance in lung cancer with high PD-L1 or TMB in EGFR-sensitive mutations. Respiratory Res. 25, 40 (2024).

Van der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 43, 11.0.1–0.33 (2013).

Koboldt, D. C. et al. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics 25, 2283–2285 (2009).

Ye, K. et al. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 25, 2865–2871 (2009).

Boeva, V. et al. Multi-factor data normalization enables the detection of copy number aberrations in amplicon sequencing data. Bioinformatics 30, 3443–3450 (2014).

Roach, C. et al. Development of a companion diagnostic PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assay for pembrolizumab therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 24, 392–397 (2016).

Shen, W. et al. Sangerbox: a comprehensive, interaction-friendly clinical bioinformatics analysis platform. iMeta 1, e36 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. RAB42 overexpression correlates with poor prognosis, immune cell infiltration and chemoresistance. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1445170 (2024).

Bu, Y. et al. MSR1 in lung squamous cell carcinoma: prognostic and immunological values in pan-cancer and single-cell analyses and a cohort study. Int. Immunopharmacol. 145, 113811 (2025).

Mayakonda, A. et al. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28, 1747–1756 (2018).

Zeng, D. et al. IOBR: multi-omics immuno-oncology biological research to decode tumor microenvironment and signatures. Front. Immunol. 12, 687975 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shandong Province Medical and Health Science and Technology project [202303111291]; the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang province [2023C03057]; the Jiaxing Science and Technology Program-Social Development Special Project [2025BS009]; and the Key Technology Innovation Projects of Jiaxing [2024BZ20002]. We thank the patients who agreed to participate in this study. We thank the clinical teams who cared for the patients and the Yunying laboratory teams who realized NGS assay and bioinformatics analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Yubo Jiang, Daoyun Zhang, Huirong Xu; Validation: Yubo Jiang, Gang Mai, Meng, Tang, Qian Cheng, He Tian, Zuoxing Niu; Investigation: Yubo Jiang, Meng Tang, Qian Cheng, He Tian, Zuoxing Niu; Writing–original draft: Yubo Jiang, Gang Mai, Xiaokai Zhao, Pengmin Yang; Writing–review & editing: Meng Tang, Qian Cheng, He Tian, Huirong Xu; Formal analysis: Xiaokai Zhao, Pengmin Yang, Ziying Gong; Visualization: Xiaokai Zhao, Pengmin Yang, Jieyi Li; Methodology: Gang Mai, Xiaokai Zhao, Ziying Gong; Data curation: Xintao Wang, Jiao Wang, Yudong Zhu, Daoyun Zhang, Huirong Xu; Supervision: Ziying Gong, Daoyun Zhang, Huirong Xu; Project administration: Daoyun Zhang, Huirong Xu; Funding acquisition: Ziying Gong, Daoyun Zhang, Huirong Xu. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, and read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Xiaokai Zhao, Pengmin Yang, Xintao Wang, Jiao Wang, Yudong Zhu, Jieyi Li, Ziying Gong, and Daoyun Zhang were employed by the Jiaxing Yunying Medical Inspection Co., Ltd., and the Shanghai Yunying Biopharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Mai, G., Zhao, X. et al. Molecular characterization and prognostic implications of KRAS mutations in pancreatic cancer patients: insights from multi-cohort analysis. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 299 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01087-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01087-1