Abstract

Accurate prediction of lymph node metastasis (LNM) in T1 esophageal squamous cell cancer is critical for guiding treatment decisions after endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). We developed a deep learning-based artificial intelligence model using whole slide images (WSIs) to predict LNM and reduce overtreatment. The model was trained, validated, and internally tested on 160 surgically resected cases (72 LNM+, 88 LNM–) from 374 patients without prior ESD, achieving an AUC of 0.949 (95% CI: 0.912–0.986) on internal test. Further validation was performed on an external ESD cohort comprising clinically high-risk cases with invasion depths from MM to SM2. The model attained an accuracy of 90.1%, sensitivity of 81.8%, specificity of 91.4%, and an F1-score of 69.2%. It correctly classified 90.1% of samples, with a negative predictive value (NPV) of 96.9%. The high NPV and specificity underscore the model’s utility in minimizing overtreatment while preserving diagnostic accuracy in high-risk T1 esophageal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) remains a substantial global health burden, with disproportionately high incidence and mortality rates in China1,2. For early-stage lesions limited to the mucosa or superficial submucosa (T1a), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is established as the first-line curative treatment3. Post-ESD histopathological evaluation identifies high-risk features such as lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and tumor budding, which correlate with lymph node metastasis (LNM), and often prompt recommendations for supplemental esophagectomy4. However, the significant invasiveness and morbidity associated with esophagectomy, particularly in the old or those with multiple comorbidities, raise concerns about overtreatment, as only ~10% of patients with LVI ultimately develop nodal metastases5. These findings underscore the critical need for refined risk stratification in post-ESD specimens to accurately identify occult LNM, thereby enabling personalized management and reducing unnecessary surgery in low-risk cohorts.

The conventional diagnostic paradigm for detecting tumor metastases, particularly micrometastases, relies on labor-intensive manual slide evaluation by pathologists, a process prone to diagnostic uncertainty due to subtle morphological features6. These challenges highlight the need for automated, objective tools to augment histopathological assessment. Over the past decade, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative tool in medical diagnostics, enabling automated or semi-automated analysis of complex imaging data7. Advances in computational pathology-fueled by high-throughput slide scanning, enhanced computing power, and scalable storage solutions, have further expanded AI’s capacity to mine microscopic lesions and interpret gigapixel-sized digital images (WSIs)8. While AI-driven prediction of LNM has been explored in multiple cancers9,10, its application to ESCC remains unexplored, representing a critical gap in optimizing risk stratification for early-stage disease.

A cornerstone of AI implementation in WSIs analysis involves segmenting high-resolution images into smaller, computationally manageable patches. Current methodologies predominantly employ supervised learning frameworks, utilizing dichotomized LNM status (positive/negative) as supervisory labels11,12. This methodology offers distinct advantages for LNM prediction in cancer. First, supervised learning leverages histologically validated labels to establish a robust ground truth, enabling models to discern metastasis-associated features with high diagnostic accuracy13. Second, it explicitly models known clinicopathological features such as LVI or tumor budding that correlate strongly with metastatic risk, ensuring biologically relevant feature prioritization14. Third, supervised frameworks enhance interpretability by linking predictions to specific histopathological patterns, a prerequisite for clinical adoption where model transparency and reliability are paramount15. Finally, the flexibility of supervised learning supports integration with advanced architectures, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and graph neural networks (GNNs), which excel at capturing spatial and contextual dependencies within WSIs16.

To address the unmet need for precise LNM risk assessment in early-stage ESCC with invasion depths from MM to SM2, we developed an AI-driven GNN model using supervised learning in order to analyze WSIs from ESD specimens. This approach aims to reduce diagnostic subjectivity, improve detection of micrometastases, and ultimately guide personalized post-resection management.

Results

Study population and cohort characteristics

This study was conducted utilizing two independent patient cohorts. The model was developed from a surgical cohort comprising 374 patients who underwent primary esophagectomy without prior ESD. Within this cohort, 72 patients were LNM+, and 302 were LNM–. To address the class imbalance and enhance model generalizability, a balanced training set was constructed, comprising 72 LNM+ and 88 randomly selected LNM– cases. The representativeness of this LNM subset was confirmed, as no significant differences in key baseline characteristics were observed compared to the remaining 214 LNM– patients (Table S1).

This cohort of 160 patients was then randomly divided into a training/validation set (n = 112, 442 WSIs) and an internal test set (n = 48, 217 WSIs) in a 7:3 ratio. The distribution of critical prognostic factors, including LVI (61.6% vs. 64.6%) and actual LNM rate (46.4% vs. 41.6%), was well-balanced between these sets, with no statistically significant differences in age, sex, tumor size, clinical stage, tumor location, differentiation grade, lymphovascular or perineural invasion status, or lymph node yield (Table 1).

For external validation, we utilized a separate cohort of 35 high-risk patients who had previously undergone ESD. This cohort comprised patients who subsequently received esophagectomy with systematic lymphadenectomy (n = 18, 85 WSIs) and those who managed with surveillance alone (n = 17, 76 WSIs), resulting in a total of 161 WSIs for analysis. The final nodal status, confirmed by histology or follow-up, identified 4 patients as LNM+ and 31 as LNM–. The model’s performance was rigorously evaluated on this independent ESD cohort to assess its clinical applicability.

Validation performance of the AI model

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the optimal cutoff value for the model was determined from the internal test set. At this optimized threshold, the model demonstrated robust performance in predicting LNM in ESCC, achieving an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.949 (95% CI: 0.912–0.986) in the internal validation cohort and 0.866 (95% CI: 0.768–0.964) in the external ESD validation cohort.

Test performance and clinical utility

Table 2 summarizes the distribution of histopathological features, including submucosal invasion depth and tumor budding grade, within the external validation cohort, providing context for correlation analyses with model predictions.

On a per-slide basis within the external cohort, the AI model achieved an accuracy of 90.1%. Performance metrics included a sensitivity of 81.8%, specificity of 91.4%, an F1-score of 69.2%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 96.9% (Fig. 2). This high NPV suggests a potential to reduce unnecessary surgeries by correctly identifying a substantial proportion of non-metastatic cases, highlighting its utility for patient stratification towards non-surgical surveillance.

The corresponding confusion matrix is detailed in Table 3, which shows 18 true positives (TP), 4 false negatives (FN), 127 true negatives (TN), and 12 false positives (FP). These results underscore the model’s high accuracy and reliability, particularly in correctly classifying non-metastatic cases, thereby effectively minimizing the risk of false-positive predictions.

Case-level diagnostic performance aligned with clinical practice

Reflecting real-world clinical decision-making, where a single positive slide typically defines a case as high-risk, we aggregated slide-level predictions to the case level using a max-pooling rule. In the external ESD cohort, the model achieved robust case-level performance, with a sensitivity of 100.0% (4/4), a specificity of 83.9% (26/31), and an overall accuracy of 85.7% (30/35). Notably, the NPV at the case level reached 100.0% (26/26) (Table 4). This exceptionally high NPV indicates the model’s high reliability in identifying patients who can safely avoid esophagectomy, while maintaining high sensitivity for the detection of true metastatic cases.

Discussion

The strategic management of T1 ESCC with submucosal invasion (MM-SM2) following ESD remains a considerable clinical challenge, primarily due to the substantial risk of LNM (approximately 15~30%)17,18. Current clinical guidelines rely on conventional histopathological assessment, evaluating features such as depth of invasion, LVI, poor differentiation, and other high-risk histopathological features, to guide decisions regarding additional esophagectomy19,20. Nevertheless, this approach is hampered by considerable interobserver variability and limited reproducibility in identifying features predictive of nodal involvement. The suboptimal discriminative capacity of these morphological criteria can lead to potential overtreatment of patients with minimal LNM risk and underscoring the urgent need for more precise and objective risk stratification tools21,22.

To address this critical unmet need, we developed an AI-driven model for predicting LNM using computational pathology. Our model utilizes a hierarchical GNN architecture to autonomously learn multi-scale histopathological representations from WSIs, capturing intricate morphological patterns without relying on subjective human interpretation. Due to the scarcity of ESD specimens with surgically confirmed nodal status, model development incorporated surgically resected T1–T4 cases, while external validation was rigorously restricted to T1 ESD cases to ensure clinical relevance. This approach enables a fully automated, objective, and reproducible prediction of metastatic risk. The model demonstrated robust performance in internal validation (AUC: 0.949), and, crucially, in an external cohort of real-world MM-SM2 ESD cases, the most relevant subgroup of post-ESD decision-making. It achieved a sensitivity of 81.8% and a high NPV of 96.9%, with case-level max-pooling further enhancing its clinical utility (100% sensitivity, 100% NPV, 83.9% specificity). The consistently high NPV underscores the model’s capability to reliably identify patients at low risk of LNM, for whom conservative management may be appropriate, thereby potentially reducing unnecessary surgeries.

A key innovation of our framework is its ability to transcend the limitations of conventional region-of-interest (ROI) or patch-based analyses10,23,24. By constructing a biologically interpretable k-nearest neighbor graph integrating multimodal features (including color histograms, spatial coordinates, and deep feature embeddings)25,26,27, our GNN architecture effectively models local and global tissue architecture without manual annotation, overcoming the limitations of methods that introduce noise or fail to capture spatial dependencies. This end-to-end, supervised approach explicitly captures spatial relationships among histopathological patches, addressing the “needle-in-a-haystack” challenge inherent in WSI analysis and identifying subtle metastatic signatures potentially overlooked in conventional assessment28,29.

Notably, our AI system autonomously learned prognostically relevant morphological patterns directly from WSIs, without explicit programming of established risk factors30,31, It successfully identified a subset of low-risk patients, confirmed by postoperative histology, who might otherwise have been recommended for surgery under current guidelines32,33. To enhance interpretability and mitigate the “black box” concern, we generated decision heatmaps that visualized model-prioritized regions. These heatmaps consistently highlighted areas concordant with established high-risk features, such as the invasive front and lymphocyte-rich stroma, a finding validated by independent expert pathologists, thereby providing biologically plausibility to the model’s predictions. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that heatmaps remain indirect proxies of the underlying model reasoning.

Notwithstanding these promising performances, several limitations merit consideration. The single-center, retrospective design may affect generalizability, necessitating future multi-institutional prospective validation. The inclusion of multiple tumor slides per patient, while improving data utilization, introduces analytical complexity regarding intra-patient dependency. Furthermore, the incorporation of more advanced ESCC cases during training, necessitated by the limited availability of node-positive T1 ESD cases, creates a potential domain shift, a common compromise in computational pathology. In the external cohort, the inference of nodal status based on recurrence-free survival for non-surgical patients, while clinically accepted, represents an indirect method of outcome assessment. Future work should also systematically investigate case-level prediction integration, which may yield even higher diagnostic performance.

In conclusion, we developed and validated a pathologist-independent AI model that accurately predicts LNM risk in T1 ESCC from WSIs. This GNN-based framework provides a robust, automated decision-support tool to optimize post-ESD management pathways, facilitating personalized care and potentially improving quality of life. Future efforts should focus on external validation, real-world clinical integration, and the development of hybrid models combining AI predictions with molecular biomarkers for enhanced risk stratification.

Methods

Study design

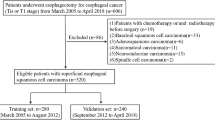

This retrospective single-center study enrolled 374 patients with ESCC, stages T1–T4, who underwent primary esophagectomy with systematic lymphadenectomy without previous ESD at Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University from January 2019 to December 2024 (Fig. 3). Among them, 72 were LNM+ and 302 were LNM–. To address class imbalance, 72 LNM+ and 88 randomly selected LNM– cases were included as the surgical cohort (n = 160) for model training, validation, and internal testing.

From January 2019 to December 2024, 160 patients with 1284 WSIs were considered for the surgical cohort, 625 WSIs were excluded due to no tumor tissue, the remaining 160 patients with 659 WSIs were randomly divided into a training set (112 patients, 442 WSIs) and a test set (48 patients, 217 WSIs) at a 7:3 ratio, and an ESD cohort of 35 patients with 161 WSIs was used as an external validation set for the prediction model. Only surgically resected cases were used for model training and internal validation. ESD cases were used solely for external testing to simulate real-world post-ESD clinical scenarios.

An independent external validation cohort comprised 35 patients with T1 ESCC (MM to SM2) who underwent ESD. This cohort included patients with LNM+ status confirmed by subsequent surgical resection, as well as LNM– patients defined by the absence of tumor recurrence during a 3-year follow-up period after ESD34. This follow-up criterion is grounded in established oncological principles, where 3-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) serves as a clinically validated surrogate for confirming true nodal negativity in non-surgically managed patients35.

This AI model employed a supervised GNN framework to analyze histopathological patterns in WSIs. Notably, no handcrafted histologic features (such as submucosal invasion depth, tumor budding, LVI, etc.) were manually extracted or explicitly incorporated as input variables. Instead, the model was trained directly on raw WSIs, allowing it to infer predictive patterns from the underlying morphology in a data-driven manner. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics review committee (No. 2024ZDSYLL385-P01).

Conventional histologic assessment

All specimens obtained were immediately fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. They were then cut at the point where the deepest invasion area could be exposed on the cut end surface. Histological sections of ESD specimens were cut into parallel 2–3 mm-thick sections, and esophagectomy specimens into 4–5 mm-thick sections, followed by Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. All specimens were diagnosed on the basis of the 2019 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors and the categorizing lesions as well differentiated, moderately differentiated, or poorly differentiated3,5. Submucosal invasion depth was measured vertically from the muscularis mucosa, with cases stratified as SM1 (≤200 μm) or SM2 (>200 μm)17. LVI was assessed through combined immunohistochemical (D2-40) and histochemical methods (Victoria blue staining)17. Tumor budding, defined as isolated cancer cell clusters (≤5 cells) at the invasive margin, was graded as BD1 (0–4 buds/field), BD2 (5–9 buds/field), or BD3 (≥10 buds/field) under 200× magnification4. At our institution, additional surgery following ESD is recommended if any of the following features are present: (1) submucosal invasion depth >200 μm (SM2), (2) presence of LVI, (3) poorly differentiated histology, (4) positive vertical or horizontal resection margins, and (5) tumor budding grade ≥BD2. For surgically resected cases, both the number of metastatic lymph nodes and the total number of dissected lymph nodes were recorded from pathology reports. Lymph node yield was used to assess the adequacy of lymphadenectomy, with reference to guideline standards (≥15 nodes for accurate staging according to AJCC criteria)36.

Data preparation and preprocessing

Among the 1284 WSIs obtained from the surgical cohort, slides without tumor tissue, slides of inadequate quality, or those containing only blank regions were excluded. As a result, 659 WSIs containing sufficient tumor regions were retained for model development. To provide a clinically interpretable workflow, the selected WSIs were then divided into small patches, morphological and spatial features were extracted, and graphs were constructed to represent the histological architecture. The proposed computational framework implements a unified analytical workflow for predicting LNM in T1-stage ESCC by systematically combining multimodal computational histopathological feature extraction with a hierarchical GNN architecture. Multimodal features (color histograms, spatial coordinates, ResNet-50 embeddings) were concatenated and normalized to a shared latent space via a fully connected layer (512 dimensions).

The overall framework of the proposed method is illustrated in Fig. 4. The ‘GNNClassifier’ leverages two graph convolutional layers (GCNConv) with ReLU activation and dropout (p = 0.4) to propagate node features across the graph structure, ultimately aggregating slide-level representations via global mean pooling for classification. Results, including predicted probabilities and binary classifications, are systematically logged in ‘prediction_results.txt’ for retrospective analysis. Auxiliary utilities validate CUDA compatibility and GPU acceleration prerequisites, completing a robust computational ecosystem that bridges histopathological feature engineering with clinical decision support through modular, reproducible design.

The workflow comprises: (1) Input WSIs are divided into 224 × 224 pixel patches (stride 112), followed by spatial domain preprocessing and graph construction. (2) ResNet-50 extracts patch features (2048 channels), reduced to 512 channels via dimensionality reduction, and fused through multimodal integration. (3) A hierarchical architecture with two-stage graph convolutional layers (GCNConv), feature compression, and global context aggregation modules learns spatial dependencies and semantic representations. (4) Global mean pooling and a softmax classifier perform binary classification, outputting invasion probabilities.

WSI acquisition and annotation

H&E-stained slides of all the tissue masses in each case were selected for further analysis. The slides were captured as WSIs at 40× magnification using NanoZoomer (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). QuPath (https://qupath.github.io) was used to annotate and designate cancerous regions by two experienced pathologists (T.K.H. and X.J.J.). All results were double reviewed and were discussed with an independent and blinded pathologist (W.X.Y.) if not in concordance. The captured WSIs were partitioned into non-overlapping 224 × 224 pixel patches. Blank patches and patches without cancerous areas were excluded. Patches were assigned slide-level labels according to the LNM status of the corresponding patient, and patches in cases without LNM were defined as LNM-negative patches.

Data preprocessing and feature extraction

To balance computational efficiency with tissue representation, a maximum of 1000 patches per WSI was retained. Data augmentation strategies included random horizontal/vertical flipping and 30° rotation to enhance rotational invariance, supplemented by a multi-scale sampling strategy (0.5~1.5× scaling) by randomly selecting patches across different WSI pyramid levels to improve scale invariance. For feature extraction, a pretrained ResNet-50 architecture (with final classification layers removed) generated 2048-dimensional feature vectors. These features were subsequently reduced to 512 dimensions via a fully connected layer. To address illumination invariance, LAB color space-based histogram matching was applied for standardization, with additional random brightness/contrast perturbations (±20%) simulating tissue staining variations under diverse exposure conditions. Spatial coordinates were normalized to the [0,1] range, followed by construction of a 10-nearest neighbor graph (k = 10) using the ‘knn graph’ function, establishing topological connections to model spatial relationships between adjacent tissue regions. The selection of k = 10 for nearest neighbor graph construction was empirically validated through ablation studies (k = 5, 10, 15, 20). Performance peaked at k = 10, which balances local context capture and computational efficiency.

Graph neural network architecture

The proposed hierarchical GNN model was trained on graph representations constructed from WSIs. First, each WSI was divided into non-overlapping 224 × 224 pixel patches. Patch-level feature vectors were extracted using a pretrained ResNet-50 backbone (2048 dimensions), followed by a linear compression layer that reduced the features to 512 dimensions. Spatial adjacency among patches was then used to construct a graph, where each patch served as a node and neighboring patches were connected via edges. This hierarchical design was chosen to capture both local tumor microenvironment features and global tissue architecture, which are both critical for predicting LNM. The detailed process of patch division, feature extraction, and graph construction is shown in Table 5.

The resulting graph was processed through two graph convolutional layers (GCNConv) with 512 hidden units, ReLU activation, and dropout. A global mean pooling layer was applied to aggregate node-level information into a slide-level embedding. Finally, a fully connected classification head (512 → 2 units) with softmax activation outputs the predicted probability of LNM. The GCN layers allowed the model to capture spatial patterns within the tumor microenvironment, while global pooling enabled holistic WSI-level prediction based on local features.

Supervised training protocol

The model was trained using PyTorch Lightning with class-weighted cross-entropy loss to address class imbalance. Optimization was performed via the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate = 1 × 10⁻⁴) paired with a ‘ReduceLROnPlateau’ scheduler (factor = 0.1, patience = 5 epochs). Early stopping (patience = 4000 epochs) monitored validation accuracy to mitigate overfitting, while mixed-precision training (16-bit) on NVIDIA A100 GPUs accelerated computational efficiency. Early stopping at 4000 epochs was determined by plateau analysis of validation loss (no improvement for 50 epochs), preventing overfitting while ensuring convergence. Class weighting and early stopping were implemented to reduce bias from class imbalance and to prevent overfitting, thereby improving the generalizability of the model. Five-fold cross-validation demonstrated stable performance across partitions (accuracy: 88.7% ± 1.1%, F1-score: 0.85 ± 0.03). Three independent trials with randomized seeds yielded consistent results (accuracy: 89.2% ± 1.3%, F1-score: 0.87 ± 0.02), confirming low variance. Augmentation robustness tests with randomized parameters (rotation, flipping, multi-scale sampling) showed negligible performance degradation (accuracy <1.5%), underscoring feature invariance under diverse transformations. This multi-faceted validation framework ensured statistical reliability and minimized bias in clinical deployment.

Evaluation of the trained model

Model performance was evaluated using the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). The optimal classification threshold was determined by maximizing Youden’s J statistic. Results were compared against the actual pathological condition. Threshold optimization prioritized NPV (maximizing Youden’s J with NPV > 95%), as false negatives (missed LNM) may lead to under-treatment, whereas false positives (unnecessary surgery) were deemed clinically tolerable.

Model interpretability and attention heatmap generation

To improve model interpretability, we computed node-level attention scores from the hierarchical GNN and generated attention heatmaps overlaid on the original WSIs. Each node corresponded to a histopathological patch, with color intensity reflecting its relative contribution to the final prediction. These heatmaps consistently highlighted histological regions of interest, such as invasive tumor fronts and areas rich in lymphoid tissue with clustered vessels, features that are known to be associated with LNM risk. All heatmaps were independently reviewed by two gastrointestinal pathologists (both with >10 years of diagnostic experience), who confirmed that the high-attention regions corresponded closely with established pathological risk areas. Representative examples are shown in Fig. 5.

Warmer colors indicate regions with higher attention scores, reflecting greater contribution to the model’s final prediction. The highlighted areas frequently correspond to invasive tumor fronts, tumor budding foci, and lymphovascular invasion, which align with established pathological risk features. The marked boxes denote regions independently confirmed by expert gastrointestinal pathologists.

Statistical analysis

The translation model was developed using Python 3.8 (Python Software Foundation) with PyTorch 1.12.0 and PyTorch Geometric 2.2.0 libraries. The architecture integrated a GNN with CNNs. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Continuous variables were assessed for normality via the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variance with Levene’s test. Normally distributed variables were compared using Student’s t-test, while non-parametric data were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were evaluated by χ²-test or Fisher’s exact test when expected cell counts fell below 5. The discriminative performance of the predictive model was quantified by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), with 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated through bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) using the percentile method. For the primary endpoint of predicting LNM in patients with T1 ESCC undergoing ESD, model performance was evaluated using standard diagnostic metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, NPV, F1-score, and ROC AUC. The results were comprehensively summarized both in tabular format and through graphical presentations. All P-values were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Predictions were saved to a file that contains detailing filenames, LNM probabilities, and classifications for clinical review.

Data availability

Due to the privacy of patients, the data related to patients cannot be available for public access, but can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request approved by the institutional review board of all enrolled centers.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is available on GitHub and can be accessed via this link: https://github.com/dingy97/WSI-main.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Yang, H. et al. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet 404, 1991–2005 (2024).

Fleischmann, C., Probst, A. & Messmann, H. Indications for endoscopic treatment of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer of the esophagus. Ann. Esophagus 6 (2023).

Fuchinoue, K. et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor budding as predictor of lymph node metastasis from superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Esophagus 17, 168–174 (2020).

Nagtegaal, I. D. et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 76, 182–188 (2020).

Weaver, D. L. et al. Pathologic analysis of sentinel and nonsentinel lymph nodes in breast carcinoma: a multicenter study. Cancer 88, 1099–1107 (2000).

Esteva, A. et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 542, 115–118 (2017).

Komura, D. & Ishikawa, S. Machine learning methods for histopathological image analysis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 16, 34–42 (2018).

Ichimasa, K. et al. Efficacy of a whole slide image-based prediction model for lymph node metastasis in T1 colorectal cancer: a systematic review. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 39, 2555–2560 (2024).

Ehteshami Bejnordi, B. et al. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning algorithms for detection of lymph node metastases in women with breast cancer. JAMA 318, 2199–2210 (2017).

Mi, S. et al. Development and validation of a machine-learning model to predict lymph node metastasis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Biosci. Trends 18, 535–544 (2024).

Ueki, H. et al. Utility of machine learning models to predict lymph node metastasis of Japanese localized prostate cancer. Cancers 16, 4073 (2024).

Rani, V. et al. Self-supervised learning: a succinct review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30, 2761–2775 (2023).

Cheplygina, V., de Bruijne, M. & Pluim, J. P. W. Not-so-supervised: a survey of semi-supervised, multi-instance, and transfer learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 54, 280–296 (2019).

Qi, G. J. & Luo, J. B. Small data challenges in big data era: a survey of recent progress on unsupervised and semi-supervised methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 2168–2187 (2022).

Ericsson, L. et al. Self-supervised representation learning: introduction, advances, and challenges. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 39, 42–62 (2022).

Mine, S. et al. Japanese classification of esophageal cancer, 12th edition: part I. Esophagus 21, 179–215 (2024).

Rice, T. W., Patil, D. T. & Blackstone, E. H. 8th edition AJCC/UICC staging of cancers of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: application to clinical practice. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 6, 119–130 (2017).

Altorki, N. K. et al. Total number of resected lymph nodes predicts survival in esophageal cancer. Ann. Surg. 248, 221–226 (2008).

Ajani, J. A. et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 2.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl Compr. Cancer Netw. 21, 393–422 (2023).

Al-Haddad, M. A. et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on endoscopic submucosal dissection for the management of early esophageal and gastric cancers: methodology and review of evidence. Gastrointest. Endosc. 98, 285–305.e38 (2023).

van Hagen, P. et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 2074–2084 (2012).

Hou, L. et al. Patch-based convolutional neural network for whole slide tissue image classification. In Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern Recognition 2424–2433 (2016).

Shafique, A. et al. Automatic multi-stain registration of whole slide images in histopathology. In Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 3622–3625 (2021).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Transformer-based unsupervised contrastive learning for histopathological image classification. Med. Image Anal. 81, 102559 (2022).

Lu, M. Y. et al. Data-efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole-slide images. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 555–570 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Weakly supervised deep learning for whole slide lung cancer image analysis. IEEE Trans. Cyber. 50, 3950–3962 (2020).

Zhou, H. J. et al. ccRCC metastasis prediction via exploring high-order correlations on multiple WSIs. In 27th International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Palmeraie Conf Ctr, Marrakesh, MOROCCO, Oct 06-10; Palmeraie Conf Ctr, Marrakesh, MOROCCO 145–154 (2024).

Li, J. W. et al. In Dynamic Graph Representation with Knowledge-aware Attention for Histopathology Whole Slide Image Analysis, IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, Jun 16-22; Seattle, WA, 2024; pp 11323-11332.

Ha, R. K. et al. Histopathologic risk factors for lymph node metastasis in patients with T1 colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 93, 266–271 (2017).

Yasue, C. et al. Pathological risk factors and predictive endoscopic factors for lymph node metastasis of T1 colorectal cancer: a single-center study of 846 lesions. J. Gastroenterol. 54, 708–717 (2019).

Asano, M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and surgical treatment for gastrointestinal cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 4, 438–447 (2012).

Lee, H. Management strategy of non-curative ESD in gastric cancer: curative criteria, and the critical building block for determining beyond it. J. Gastric Cancer 25, 210–227 (2025).

Chang, C. et al. Monitoring for recurrence after esophagectomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 114, 211–217 (2022).

Tanaka, T. et al. Comparison of long-term outcomes between esophagectomy and chemoradiotherapy after endoscopic resection of submucosal esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis. Esophagus 32, doz023 (2019).

Amin, M. B. et al. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 93–99 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grants from the Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University, Jiangsu Province High-Level Hospital Pairing Assistance Construction Funds (zdlyg12); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82404088); Jiangsu Provincial Basic Research Special Fund (Natural Science Foundation) Youth Fund (BK20241683); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M730587).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R., Y.D., Y.Z., and K.T. contributed equally to the article. The four authors drafted the manuscript together. L.W., W.Z., Y.Z., and B.W. contributed to the data collection. J.X. and X.W. contributed to the pathological interpretation. L.R., K.H., and R.S. conceived and designed the project and are responsible for the overall content. All authors contributed significantly and agree with the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, LH., Ding, Y., Zhang, YX. et al. Artificial intelligence-driven prediction of lymph node metastasis in T1 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma using whole slide images. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01186-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01186-z