Abstract

Two-dimensional materials such as gallium selenide (GaSe) hold promise for optoelectronics due to their tunable bandgaps. Gallium sesquiselenide (Ga2Se3), a related phase with a direct bandgap, is also suitable for integration on silicon due to its matching lattice constant. We demonstrate wafer-scale synthesis of GaxSey by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition, varying growth temperature (450–600 °C) and selenium-to-gallium ratio. To guide phase-pure growth, we construct a phase diagram. Raman spectroscopy confirms phase formation, while mass spectrometry of Di-iso-propyl selenide supports the temperature-dependent phase transition, induced by the actual selenium-to-gallium ratio on the wafer surface. Microscopy reveals distinct morphologies: Ga2Se3 forms epitaxial films with antiphase domains on GaP/Si, while GaSe grows as faceted 〈111〉 -oriented sheets. Optical spectroscopy confirms direct transitions at 1.34 eV (Ga2Se3) and 1.89 eV (GaSe). These results demonstrate controlled MOCVD growth of phase-pure GaxSey and highlight their potential for silicon-based optoelectronic integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2010, Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their pioneering work on the two-dimensional (2D) material graphene, a discovery that catalyzed extensive research into the broader class of 2D materials1. The monolayers of graphene, which they successfully isolated using the scotch tape method, also enabled the examination of bilayer graphene with precisely controlled moiré angles. Remarkably, when the twist angle between the two graphene layers is approximately 1.1°, superconductivity is observed2.

In parallel with graphene, other two-dimensional materials, such as transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), have garnered attention due to their exceptional thickness-dependent properties3,4. While most TMDCs exhibit an indirect bandgap in the multilayer regime, monolayer TMDCs typically exhibit a direct bandgap5,6. To further expand the landscape of 2D materials beyond TMDCs, increasing interest has been directed toward post-transition metal chalcogenides (PTMCs), including indium selenide (InSe), gallium telluride (GaTe), gallium sulfide (GaS), and gallium selenide (GaSe)7,8,9,10,11,12. Among these, GaSe and gallium sesquiselenide Ga2Se3 are the focus of the present study. GaSe is a layered 2D material with a hexagonal crystal structure and occurs in several polytypes distinguished by the stacking sequence of Se–Ga–Ga–Se tetralayers along the c-axis: β (AA′, layers rotated 180° relative to each other), ε (AB, alternating translation by 1/3 and 2/3 along 〈1010〉 directions), γ (ABC, translation by 1/3 along 〈1010〉), δ (ACABA)13. These stacking variations arise from combinations of rotation and lateral translation of the unit cell, and the most commonly reported polytypes in the literature are ε and γ. Additionally, a γ′ polymorph exists, in which the Se atoms of one half-layer shift to form parallel Se–Ga dumbbells, unlike the non-parallel configuration in γ, while the Ga positions remain unchanged9,13. These variations arise from shifts in the relative positioning of adjacent layers, leading to changes in symmetry and periodicity. In contrast, Ga2Se3 can be synthesized as a covalent crystal in two distinct polymorphs, exhibiting either a cubic structure in its high-temperature stable α-phase or a monoclinic structure in its low-temperature stable β-phase. The β-Ga2Se3 structure is a superstructure of the α-phase, characterized by an approximately threefold larger unit cell volume14,15. Both GaSe and Ga2Se3 exhibit direct bandgaps under specific conditions14,16. Ga2Se3 has demonstrated direct band-edge emission at 1.85 eV (670 nm), although a range of bandgap values, spanning from 1.3 to 2.4 eV (954–517 nm), have been reported14,17,18,19,20,21,22. In contrast, the bandgap of GaSe in multilayer configurations varies between 1.74 and 2.00 eV (713 nm to 620 nm), contingent upon the strain induced by the substrate or the presence of screw dislocations. For the monolayer, the bandgap increases to approximately 3.3 eV (376 nm), exhibiting a quasi-indirect transition16,23,24. This quasi-indirect bandgap in few-layered GaSe is characterized by a distinctive ‘Mexican hat’ dispersion profile25. Additionally, investigations into the alloying of GaSe with sulfur to produce GaS1−xSex have demonstrated tunability of the bandgap within the range of 2.0–2.5 eV (713 to 496 nm) in multilayer structures16. Theoretical studies have also explored the Janus configuration of Ga2SeTe, further expanding the scope of bandgap engineering in these materials16,26. Collectively, these properties position GaSe as a highly promising candidate for light-emitting diode (LED) and laser applications across the entire visible spectrum16. Additionally, GaSe demonstrates significant potential for applications in the development of single-photon emitters, second-harmonic generators, and photodetectors27,28,29,30. Similarly, the related phase, Ga2Se3, holds potential for applications in visible-light-driven photocatalytic water splitting, as well as in photovoltaic devices and LEDs14,31,32,33.

While significant progress has been made in the investigation of 2D materials, the majority of studies have relied on either mechanically exfoliated flakes or powder-based chemical vapor deposition (CVD) techniques34,35,36,37,38. These top-down and bottom-up approaches, respectively, present inherent challenges in terms of scalability. Metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), by contrast, offers a promising solution due to its well-established capability for producing large-area films with excellent uniformity and reproducibility39. Other wafer-scale growth techniques include molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) and atomic layer deposition (ALD). However, MBE is limited by its requirement for ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions, while ALD is constrained by the availability of suitable chemical precursors.

To enable the growth of either GaSe or Ga2Se3 using these techniques, careful consideration of the relevant phase diagram is essential40. Successful growth of GaxSey has already been demonstrated by both MBE and MOCVD41,42,43,44,45. However, because phase formation can vary depending on the growth method—such as MOCVD, MBE, or physical vapor deposition (PVD)—due to differences in growth temperature and element ratios, it is necessary to develop a phase diagram for each growth technique.

The formation of either GaSe or Ga2Se3 is highly dependent on both temperature and the selenium-to-gallium partial pressure ratio (ΦSe/Ga), with distinct phases emerging under different growth conditions40. To capture this behavior under MOCVD conditions, we construct a temperature- and ΦSe/Ga-dependent phase diagram for the GaxSey system in the range of 450–600 °C. This phase diagram identifies the specific growth regimes in which phase-pure GaSe and Ga2Se3 can be obtained and serves as a practical reference for future studies focused on MOCVD growth of these two materials.

To enable a well-defined epitaxial relationship between the substrate and the grown material, specific substrates were chosen for the investigated materials. (100)-oriented gallium phosphide on silicon (GaP/Si) was chosen due to its favorable lattice matching with Ga2Se314,46,47. Furthermore, for integration into optoelectronic systems, the GaP/Si substrate is of particular relevance, as it has previously enabled the successful demonstration of both optically and electrically pumped Ga(N, P, As) lasers, as well as the growth of high-quality single (Ga,In)As quantum dots as single-photon emitters48,49,50,51. For the growth of GaSe, hexagonal c-plane sapphire was used, as its crystallographic symmetry supports the hexagonal structure of GaSe, an approach previously demonstrated to be effective for other two-dimensional materials, such as tungsten disulfide (WS2) and GaS10,52,53. This epitaxial approach offers promising potential for the integration of these materials into silicon-based optoelectronic devices, particularly given that both GaSe and Ga2Se3 can exhibit direct bandgap characteristics, as previously discussed.

The growth of GaSe and Ga2Se3 was achieved using di-iso-propyl-selenide (DiPSe), tri-tert-butyl-gallium (TTBGa) and tri-ethyl-gallium (TEGa), which are well-established in the industry for the growth of doped III-V compounds. Compared to other common organoselenium precursors such as diethyl selenide (DESe) and dimethyl selenide (DMSe), which exhibit higher activation energies, DiPSe offers a lower activation energy, enabling more efficient precursor decomposition at lower temperatures54,55,56,57. DiPSe has already been employed in the MOCVD growth of various chalcogenide materials, including Cu(GaIn)Se2, 2D GaSe on Si(111), and 2D tungsten diselenide (WSe2)44,58,59,60.

In this work, GaSe and Ga2Se3 were grown by MOCVD and systematically characterized to elucidate their structural and optical properties. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were used to reveal surface morphology, while confocal Raman spectroscopy enabled phase identification, mapping, and the construction of a phase diagram confirming phase-pure material. High-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (HR-STEM) was employed to investigate the epitaxial alignment, interface quality, and the presence of ordered gallium vacancies along the {111} planes in Ga2Se3. In addition, mass spectrometry of DiPSe was performed to correlate its decomposition kinetics with the observed phase formation. Photoluminescence (PL) and cathodoluminescence (CL) measurements demonstrated emission in the visible range of the spectrum for GaSe and infrared luminescence for Ga2Se3, underscoring their potential for optoelectronic applications.

Results

Phase diagram for MOCVD of GaxSey

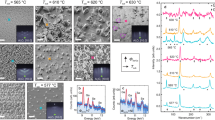

We carried out Raman spectroscopy on the samples grown as listed in Table 1 to confirm phase formation under different selenium-to-gallium partial pressure ratios (ΦSe/Ga, defined in Eq. (1)) and within a temperature range of 450–600 °C. Raman fingerprint data used for the identification of Ga2Se3 and GaSe phases were taken from previously published spectra13,24,61,62,63,64,65,66,67, while reference spectra for the substrate materials sapphire (Al2O3), GaP, and Si were also obtained from literature68,69,70,71,72,73. Figure 1 shows the resulting GaxSey phase diagram, which also includes the known crystal structures of GaSe and Ga2Se3. The corresponding Raman spectra for all samples are provided in the Supporting Information (Figs. S1–S4), covering the various growth conditions described in the figure captions. Raman mapping further confirms the phase homogeneity of our samples across the wafer. The radial profiles, recorded from the center of the wafer to the edge, reveal deviations only at the outermost region, which can be attributed to reactor-specific edge effects typical for AIX 200 systems74. This behavior is exemplarily demonstrated for GaSe and Ga2Se3 in Fig. S5.

a Side (top) and top (bottom) views of GaSe generated using VESTA.103. b The obtained MOCVD phase diagram shows the GaSe to Ga2Se3 transition driven by increasing ΦSe/Ga or increasing temperature. The phases have been concluded from Raman spectroscopy of all samples (see Figs. S1–4). The gray and green background regions in the diagram serve as a guide to the eye, indicating the observed phase. One additional datapoint for a GaSe on Si(111) sample is taken from literature.44. c Structures of the high-temperature stable cubic α-Ga2Se3 (top), which features one-third gallium vacancy sites, and the low-temperature stable monoclinic β-Ga2Se3 (bottom), which is a superstructure of the α-phase. Both structures were generated using VESTA103.

Figure 1a presents the layered structure of GaSe, with a Ga:Se ratio of 1:1, shown in both, side and top views. This composition corresponds to the gray region in the phase diagram depicted in Fig. 1b. In contrast, the green region in Fig. 1b represents Ga2Se3, characterized by a Ga:Se ratio of 2:3, whose crystal structure is illustrated in Fig. 1c. All points measured in this phase diagram are phase-pure GaSe or Ga2Se3, respectively. As a transition region containing both phases would be expected, a color gradient from grey to green is applied. The upper part of Fig. 1c shows the cubic α-phase of Ga2Se3, which has a defective sphalerite structure in which one-third of the Ga sites are vacant. The lower part depicts the monoclinic β-phase, a superstructure derived from the cubic α-phase14. The phase diagram in Fig. 1b illustrates the transition from GaSe to Ga2Se3 at four different growth temperatures: 450, 500, 550, and 600 °C, using two different substrates: GaP/Si and c-plane sapphire. To supplement the phase diagram and due to the limited availability of literature on GaSe and Ga2Se3 grown by MOCVD using DiPSe as the Se precursor, a single reported data point—GaSe grown on Si(111) at a ΦSe/Ga ratio of 5 and 550 °C using tri-methyl-gallium (TMGa) and DiPSe—has been included44. By increasing the ΦSe/Ga ratio, a phase transition from GaSe to Ga2Se3 is observed, which is consistent with previous reports40. A similar transition can also be induced by increasing the growth temperature. While in the Ge–Se and Sn–Se systems, temperature-dependent phase transitions—such as from Ge4Se9 to GeSe275 and from SnSe to SnSe276—can be explained by liquid–solid phase diagrams75,77, such behavior is not observed in the Ga–Se system within the studied temperature range40,78,79. Instead, this phenomenon is related to the temperature-dependent incorporation efficiency of selenium, which quantifies the effective amount of selenium incorporated into the film relative to the supplied precursor flux54. Incorporation efficiency reflects various processes, including precursor decomposition and desorption, and can be understood as the growth rate normalized by the molar flow of the selenium precursor. To confirm that the observed temperature-dependent phase transition is directly linked to the decomposition behavior of DiPSe, mass spectrometry measurements were carried out across the relevant growth temperature range, as shown in Fig. 2. To ensure direct comparability with growth conditions, all decomposition measurements were performed under the same parameters as in Fig. 1, namely a reactor pressure of 50 mbar, H2 as carrier gas, and a partial pressure of PSe = 2.1 × 10−3 mbar.

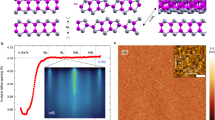

Temperature-dependent decomposition curve of DiPSe (165 u) on a bare graphite susceptor in a MOCVD AIX 200 GFR reactor. A partial pressure PSe = 2.1 × 10−3 mbar was applied, corresponding to typical growth conditions (H2 as carrier gas, 50 mbar reactor pressure). The decomposition temperature T50 is (441.3 ± 10) °C.

The decomposition temperature T50 of DiPSe was determined to be (441.3 ± 10) °C. Complete decomposition is only achieved at around 550 °C, while partial decomposition still occurs in the range of 450–500 °C. In contrast, the gallium precursors decompose at much lower temperatures, approximately 250 °C for TEGa and 140 °C for TTBGa80. This mismatch implies that at lower growth temperatures, a higher supply of DiPSe is required to compensate for its limited decomposition and to ensure sufficient selenium incorporation. The resulting deficiency is directly reflected in the temperature-dependent phase transition from GaSe to Ga2Se3 shown in Fig. 1b. To further quantify the influence of DiPSe on the Ga–Se phase formation, a comparison with another selenium precursor, such as DESe, under identical growth conditions would be required. However, due to limitations in precursor purity and availability, such a comparison could not be performed. Consequently, the effect of DiPSe on the phase transition can be assessed only qualitatively rather than quantitatively.

This observed decomposition temperature for DiPSe is consistent with previous studies on related II–VI systems. Bourret et al. reported that the growth efficiency of ZnSe using DiPSe reaches an optimum close to 500 °C at a reactor pressure of 130–140 mbar in a vertical stainless-steel MOCVD reactor (Emcore GS 3100) with hydrogen as carrier gas54. Since our experiments were conducted at a lower reactor pressure of 50 mbar, a correspondingly higher growth temperature is expected to be required to achieve efficient selenium incorporation. Similarly, Bevan et al. demonstrated that ZnSe growth can already be initiated at 400 °C55, in good agreement with the decomposition onset of DiPSe.

To overcome the dependence on the decomposition temperature, approaches used in the MOCVD growth of Sn–Se or Ge–Se systems could be applied. Instead of a single cold-wall reactor design, a two- or multi-chamber reactor can be employed, where the precursors are fully decomposed in the first chamber and then cooled to the desired growth temperature before reaching the substrate75,76.

It should be noted, however, that decomposition data are usually obtained under unimolecular conditions. During growth, the simultaneous presence of gallium precursors can facilitate catalytic or alkyl-exchange reactions that reduce the decomposition temperature. Maßmeyer et al. demonstrated such effects for group V precursors in the presence of group III species, suggesting that DiPSe could similarly decompose more readily under MOCVD growth conditions80. To investigate this, bimolecular decomposition studies of DiPSe were carried out in the presence of TEGa and TTBGa. The resulting decomposition temperatures T50 were (433.3 ± 10) °C with TTBGa and (427.9 ± 10) °C with TEGa (Fig. S6). Since these values lie within the experimental uncertainty, no significant catalytic influence of the gallium precursors on the decomposition behavior of DiPSe can be confirmed.

Notably, the resulting phase remains unchanged when switching the substrate from GaP/Si to c-plane sapphire under identical growth conditions, specifically, at 600 °C with a ΦSe/Ga ratio of 2.7 and at 500 °C with ΦSe/Ga = 440.4 as confirmed by the consistent Raman signatures shown in Figs. 3c and 4d.

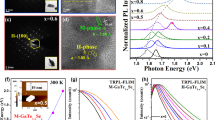

a 5 × 5 µm2 AFM image showing up to 1 µm Ga2Se3 clusters with rod-like features on GaP/Si. b 2 × 2 µm2 AFM image of smaller Ga2Se3 clusters on Al2O3 under identical growth conditions. c Raman spectra corresponding to the samples shown in (a) and (b) exhibit vibrational modes consistent with Ga2Se3 as reported in literature64,65,66,67. Substrate-related peaks above 350 cm−1 are not marked for clarity but are consistent with reported spectra68,69,70,71,72,73, and the corresponding Raman spectra of the substrates are provided in the Supplementary Information (Fig. S7). d HAADF image of a Ga2Se3 cluster. Carbon deposition and tungsten deposition used for FIB sample preparation appear as dark and bright contrast above the cluster, respectively. Rod-like features similar to those observed in (a) are present. Additionally, a thin film containing Ga2Se3 is visible beneath the cluster. e HAADF image adjacent to the cluster, revealing the thin Ga2Se3 layer on the GaP substrate with ordered vacancies along the {111} planes and characteristic ‘sawtooth’-like antiphase domains (APDs). EDX analysis verifies the stoichiometry, yielding a Ga:Se ratio of 2:3, as shown in Fig. S8. f HAADF image of the Ga2Se3/GaP interface, illustrating an epitaxial relation of the Ga2Se3 layer to the underlying GaP. g HAADF image of the ordered vacancies, revealing a van der Waals-like boundary along the {111} plane, analogous to 2D GaSe. Across the APD boundary, gallium and selenium atomic positions are reversed.

a 15 × 15 µm2 AFM image of 175 nm-high, out-of-plane GaSe sheets on GaP/Si. b 2 × 2 µm2 AFM image of planar GaSe on Al2O3, showing screw dislocations and hexagonal/trigonal edges, with a 1.5× magnified inset of an individual screw dislocation. c SEM image of GaSe on GaP/Si showing sheet-like out-of-plane growth in 〈111〉 directions of GaP substrate. EDX analysis verifies the stoichiometry, yielding a Ga:Se ratio of 1:1, as shown in Fig. S9. d Raman spectra for (a) and (b) show vibrational modes consistent with GaSe, including an additional out-of-plane mode (marked in orange), as reported in literature13,24,61,62,63. Substrate peaks are not marked for clarity but are consistent with reported spectra68,69,70,71,72,73, and the corresponding Raman spectra of the substrates are provided in the Supplementary Information (Fig. S7). e A high-resolution STEM image of the GaP/GaSe interface. The red and cyan squares indicate the regions of GaP and GaSe, respectively, from which FFTs were generated. The FFTs of GaP and GaSe are shown in (f) and (h), respectively. The FFT of the full field of view is shown in (g). The corresponding simulated diffraction patterns are depicted in (i)–(k). To highlight the epitaxial orientation relation, the (002) diffraction spots of each material are marked.

Structural characterization

Figures 3 and 4 present structural data of two representative samples selected to investigate the influence of c-plane sapphire and GaP/Si substrates on the growth of Ga2Se3 and GaSe, respectively.

To assess the substrate influence on the morphology of Ga2Se3, samples grown under identical conditions (500 °C, ΦSe/Ga = 440.4) were compared. On GaP/Si, Ga2Se3 forms micron-scale three-dimensional islands with heights approaching 1 µm. On Al2O3, these islands are significantly smaller, with diameters below 200 nm and nanometer-scale heights, as shown in the AFM images in Fig. 3a, b, respectively. The observed morphological differences can be primarily attributed to differences in the diffusion constant D of gallium on sapphire compared to GaP substrates. According to the relationship \(N\propto {\left(F/D\right)}^{p}\), where N denotes the island density, F represents the flux rate of the metal-organic precursor, and p is a function of the critical cluster size, the island density is inversely dependent on the diffusion constant81. Given that both F and p are assumed to remain constant for GaP and sapphire, the disparity in D emerges as the principal factor influencing island formation. In addition to diffusion-related effects, the substantial difference in lattice mismatch between the two substrates may also play a significant role. On GaP/Si, Ga2Se3 grows with a (100) orientation and exhibits an almost negligible lattice mismatch of less than 0.01%, whereas growth on sapphire occurs along the (111) plane and is characterized by a considerably larger lattice mismatch of approximately 19%. These combined effects in diffusion dynamics and lattice mismatch could therefore account for the pronounced morphological differences observed between the two substrates. Despite the morphological differences, both samples exhibit identical Raman modes at 106, 121, 155, 185, and 295 cm−1, which are consistent with literature values for Ga2Se3 (Fig. 3c)64,65,67. The broad Raman feature at 251 cm−1 is attributed to Ga2Se3 and overlaps with amorphous and crystalline selenium modes at 255 cm−1 and 238 cm−1, respectively64,65,66,67,82,83,84. The 295 cm−1 peak broadening is likely due to the presence of multiple Ga2Se3 Raman modes, as well as a nearby Si mode at 303 cm−1, which is also observed for samples grown under different conditions and shown in Fig. S3–572,73. Additional peaks at 367 and 418 cm−1 originate from the GaP and Al2O3 substrates68,69,70,71,72. Hence, the Raman data confirms that both samples contain only phase-pure Ga2Se3 and no GaSe. The Raman spectra of the GaP/Si and Al2O3 substrates are presented for comparison in Fig. S7. For integration into optoelectronic systems, the GaP/Si substrate is of particular relevance, as it has previously enabled the successful demonstration of both optically and electrically pumped Ga(N, P, As) lasers, as well as the growth of high-quality single (Ga,In)As quantum dots as single-photon emitters48,49,50,51. Since defects can originate at the interface and negatively impact device performance, a detailed examination of the Ga2Se3/GaP interface is essential to mitigate their formation85,86. Therefore, we present cross-sectional electron microscopic investigations of this sample in Fig. 3d–g. The high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy images of the Ga2Se3 film grown on the GaP/Si substrate show both the Ga2Se3 three-dimensional features and the thin, epitaxial layer forming directly at the interface with the GaP. The presence of the Ga2Se3 layer shown in Fig. 3e is further confirmed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), as detailed in Fig. S8. Within the Ga2Se3 three-dimensional features and the layer beneath, ‘sawtooth’-like antiphase domains (APDs) are observed. These are attributed to the ordering of gallium vacancies along the {111} planes, resulting in a two-dimensional van der Waals-like gap as previously reported by Okamoto et al.87. This gap is characterized by alternating stacking of gallium above selenium and selenium above gallium on adjacent APDs. For III–V growth on Si, APDs typically form at the interface due to mono-layer-high steps of the substrate. In zincblende structures, these APDs create homopolar III–III or V–V bonds along their boundaries85. In contrast, for the Ga2Se3/GaP/Si system, the APDs do not originate at the interface. Instead, they appear within the van der Waals-like gap, where homopolar Se–Se bonds form, giving rise to the APDs. As discussed in the introduction, Ga2Se3 has a lattice constant that closely matches that of GaP and Si. Figure 3f shows the Ga2Se3/GaP interface, which reveals an epitaxial alignment and structural continuation from the GaP substrate into the Ga2Se3 layer. This raises the question of whether similar behavior can be achieved for GaSe when grown on different substrates, particularly on GaP/Si.

Under growth conditions of 600 °C and a ΦSe/Ga ratio of 2.7, phase-pure GaSe is obtained on both GaP/Si and Al2O3 substrates. On GaP/Si, GaSe exhibits faceted growth, forming out-of-plane sheets oriented along the 〈111〉 directions of the GaP substrate, as shown in the AFM and SEM images in Fig. 4a, c. This behavior is attributed to the unintended interface roughness of the GaP, which does not present a perfectly (001) surface but instead follows the 〈111〉 orientation, as shown in Fig. S9. The (111) surface also supports GaSe growth due to its hexagonal symmetry with a lattice mismatch of less than 3%. Comparable growth behavior along the 〈111〉 directions has been reported for GaSe deposited on GaAs(001), further confirming the influence of this surface orientation62,88,89,90. On sapphire, GaSe forms in-plane hexagonal or trigonal flakes, exhibiting screw dislocations, and aligning with the hexagonal symmetry of the substrate surface, despite the large lattice mismatch of ~21%, as evidenced by the AFM in Fig. 4b. The growth behavior of GaSe on GaP/Si and sapphire is similar to that observed for β-In2Se3 and γ-InSe grown by MBE or MOCVD91,92,93, exhibiting an island-like morphology with screw dislocations. These defects can be mitigated by providing a higher selenium flux (Figs. S1 and S2). The formation of hexagonal flakes is also typical under low selenium supply, as seen in other layered materials such as WSe2 and In2Se392,94. Furthermore, the growth of β-In2Se3 on Si(111) shows similarities to GaSe growth on GaP/Si, where the 〈111〉 substrate orientation guides the out-of-plane alignment of the layers93.

This structural and morphological analysis is further supported by Raman spectroscopy, which provides insight into the crystallographic quality and phase purity of the GaSe layers on both substrates.

The presence of an additional Raman peak at 206 cm−1, alongside the characteristic 212 cm−1 peak observed in Fig. 4d, supports the occurrence of screw dislocation-driven growth24. In the case of the GaP samples, however, these features may also originate from the out-of-plane growth of GaSe62. The Raman mode at 206 cm−1 could also indicate the γ′-phase of GaSe13. Both substrates show identical GaSe Raman modes at 60, 134 and 308 cm−113,24,61,62,63. The 250 cm−1 peak is attributed to an out-of-plane GaSe mode rather than to elemental selenium or ε-GaSe. Elemental selenium can be ruled out due to the gallium-rich environment, the formation of H2Se above 400 °C in the presence of H2, and the absence of selenium droplets in SEM or AFM images65,66,82,83,84,95. EDX analysis further verifies the stoichiometry, yielding a Ga:Se ratio of 1:1 (Fig. S9). The out-of-plane growth of GaSe supports excluding ε-GaSe as a possible source of this peak24,61,62,63. Additional peaks from the substrates (Al2O3: 417 cm−1; GaP: 368, 405 cm−1) are unmarked in the spectrum, while the Si mode at 303 cm−1 appears as a shoulder on the GaSe peak68,69,70,71,72,73. These findings confirm phase-pure GaSe growth on both substrates under identical conditions. The specific growth habit of GaSe on GaP/Si is further investigated using STEM. Figure 4e shows a high-resolution HAADF image of the GaP/GaSe interface. It becomes apparent that the interface follows a GaP (111) plane. Consequently, the GaSe layers stack on this plane, resulting in the observed out-of-plane growth. The red and cyan squares indicate the regions of GaP and GaSe, respectively, from which FFTs were generated. The FFTs of GaP and GaSe are shown in (f) and (h), respectively. The FFT of the full field of view is shown in (g). The corresponding simulated diffraction patterns in the110 viewing direction (GaP) and the [1 1 -2 0] direction (GaSe) are depicted in (i)–(k). To highlight the epitaxial orientation relation, the (002) diffraction spots of each material are marked.

Optical characterization

To further assess the suitability of our layers for integration into silicon-based optoelectronic devices, PL and CL measurements were performed on Ga2Se3 and GaSe samples grown on GaP/Si, as shown in Fig. 5. It should be noted that in GaAs, APBs can act as non-radiative recombination centers and introduce electrical leakage paths, thereby degrading device performance96. In contrast, for Ga2Se3, similar defect-related effects are intrinsic due to the one-third gallium vacancy in the crystal structure, which can lead to shifts in the emission energy22. The Ga2Se3 sample shows a PL peak at 1.34 eV (925 nm), consistent with literature, and a shoulder at 1.50 eV (827 nm), which can be attributed to the GaP/Si substrate21,22. The peak position at 1.34 eV corresponds to the midpoint of a relatively flat emission feature spanning 1.31–1.38 eV (900–950 nm), reflecting the limited resolution in precisely defining the exact maximum.

a µPL spectrum of Ga2Se3 on GaP/Si measured at 80 K (blue), showing a distinct emission maximum at 1.34 eV, which corresponds to the midpoint of a relatively flat peak spanning 1.31–1.38 eV, reflecting the limited resolution to precisely define the exact maximum. A substrate-related shoulder appears at 1.50 eV. For comparison, the reference PL spectrum of the GaP/Si substrate is shown in black. b CL spectrum of GaSe on GaP/Si samples grown at 600 °C for 3 (red curve) and 30 (black curve) minutes at 20 K. Both peaks (1.89 eV, 1.65 eV) seen in the 30-min sample originate from GaSe. The 3-min grown sample shows a spectrally sharp emission feature in contrast to the longer grown sample. c µPL emission spectra of the high-thickness sample (grown for 30 minutes) measured at 4 K under varying excitation powers. The cut-off at 630 nm in the μPL spectra originates from the long-pass filter used to block the excitation laser. The excitation spot size was approximately 3–5 µm. The inset displays the integrated emission intensity as a function of excitation power on a log–log scale. A power-law fit yields a slope of 0.77 ± 0.05. (d) µPL spectra of the low-thickness sample (grown for 3 min). The spectra exhibit well-defined, sharp lines instead of the broad emission seen in panel (c) for the thicker sample. A representative peak fitted with a Lorentzian profile (blue curve) shows a narrow linewidth of (2.16 ± 0.06) meV, pointing to high spectral purity and reduced inhomogeneous broadening. The inset shows the excitation-power dependence of the two peaks at 1.914 eV (X1) and 1.933 eV (X2), yielding power-law slopes of 1.13 ± 0.02 and 1.85 ± 0.07, respectively.

The CL measurements of the samples (see Fig. 5b) reveal two pronounced emission bands at ~1.88 eV (656 nm) and 1.65 eV (752 nm), characteristic of multilayer GaSe23,24,88,90,97. As shown in Fig. 4e, this emission originates from a mixture of the γ and γ′ polytypes of GaSe. The broad feature at 1.65 eV is consistent with donor–acceptor pair recombination, as reported by Untila et al.97. Notably, the 3-min GaSe sample exhibits highly localized and spectrally sharp emission spanning approximately 1.91–1.67 (see Fig. 5b, red curve), indicative of discrete localized states. In contrast, the thicker 30-min GaSe MOCVD film in panel (b) shows a much broader emission, reflecting ensemble, delocalized recombination. To obtain further insight into the optical properties, both samples were also measured using a confocal micro-PL (μPL) setup, which includes a closed-cycle cryostat with a three-axis piezo stage, excitation at 532 nm (spot size ~3–5 μm), a monochromator with a 300 lines/mm grating, and detection with a Si CCD leading to a spectral resolution of 350 meV. The μPL results for the thicker sample shown in Fig. 5c were measured at 4 K under variable pump power, revealing a broad emission band extending from 1.80 to 1.97 eV, consistent with the CL observations. The inset illustrates the integrated emission intensity versus excitation power on a log–log scale, yielding a power-law exponent of 0.77 ± 0.05. This sub-linear dependence is typical of defect-mediated or localized-state recombination rather than free-exciton emission.

Conversely, the μPL spectra of the thinner 3-min sample plotted in Fig. 5d feature sharp, well-defined lines instead of a broad emission band in case of the thicker sample. A representative line, fitted with a Lorentzian profile (blue curve), exhibits a linewidth of (2.16 ± 0.06) meV, indicating high spectral purity and minimal inhomogeneous broadening28,98. Importantly, the excitation-power dependence of two peaks at 1.914 eV (X1) and 1.933 eV (X2) yields power-law slopes of 1.13 ± 0.02 and 1.85 ± 0.07, respectively (inset of Fig. 5d). The slight super-unity slope (~1.13) is characteristic of excitonic emission, whereas the pronounced super-linear slope (~1.85) suggests biexcitonic or higher-order complex behavior99,100.

These observations underscore that thinner, defect-controlled GaSe layers support quantum-dot-like excitonic emission, potentially enabling single-photon sources, while thicker layers show broader, defect-dominated emission typical of classical ensembles. Sharp, localized emission in thin GaSe aligns well with prior findings on single-photon emitters (SPEs) in layered GaSe, where strain-induced exciton localization leads to narrow emission lines, exciton–biexciton cascades, and in some cases photon antibunching behavior28,98. Thus, our data demonstrate that MOCVD growth time and thickness control not only the phase (GaSe vs. Ga2Se3), but also the optical emission propoerties—from broad, defect-dominated recombination in thicker films to sharp, localized, quasi-quantum-dot emission in thinner films. This offers a promising strategy for engineering GaSe-based quantum emitters28,98,99.

For samples grown on sapphire substrates, the photoluminescence signal from the substrate itself dominated the measurements, effectively overshadowing the emission from the Ga2Se3 and GaSe layers. As a result, only the PL data obtained from GaSe and Ga2Se3 grown on GaP/Si are presented in this study.

Discussion

We demonstrate that phase-pure GaSe and Ga2Se3 can be grown via MOCVD in the temperature range of 450–600 °C. The effective incorporation of selenium in this regime is closely linked to the unimolecular decomposition of DiPSe, which occurs at T50 = (441.3 ± 10) °C. Additional studies in the presence of gallium precursors (TEGa and TTBGa) show no significant catalytic effect on DiPSe decomposition, confirming that the temperature-dependent phase transition between GaSe and Ga2Se3 is primarily governed by the thermal behavior of the selenium precursor itself. This decomposition behavior influences the phase transition, shifting it to lower ΦSe/Ga ratios at higher temperatures. To mitigate this effect, the use of a selenium precursor that decomposes at lower temperatures would be preferable for the growth of GaxSey without inducing phase transitions. Alternatively, the development of a single-source precursor for the growth of phase-pure GaSe or Ga2Se3 would be of significant interest.

Furthermore, growth on GaP/Si yields micron-scale, three-dimensional Ga2Se3 islands and layers with excellent lattice matching and clear epitaxial alignment, featuring ‘sawtooth’-like APDs attributed to the ordering of gallium vacancies along the {111} planes. In contrast, growth on Al2O3 results in significantly smaller islands due to the larger lattice mismatch. Photoluminescence measurements reveal a direct optical transition in Ga2Se3 at 1.34 eV (925 nm) on the GaP/Si substrate.

Similarly, GaSe shows substrate-dependent growth behavior under comparable conditions. GaSe grows faceted and out-of-plane on GaP/Si due to the unintended 〈111〉 surface orientation, which aligns well with the substrate’s hexagonal symmetry and minimal lattice mismatch. On Al2O3, GaSe instead forms in-plane hexagonal or trigonal flakes with screw dislocations, consistent with the hexagonal surface structure of sapphire. In the GaP/Si system, multilayer GaSe exhibits CL emission around 1.88 eV (656 nm). Thinner films show sharp, localized lines ( ~ 2.2 meV linewidth), indicative of excitonic or biexcitonic recombination, while thicker films display broader, ensemble-like emission. μPL measurements at 4 K confirm these trends, with power-law behavior supporting excitonic and defect-mediated processes. These results demonstrate that growth time controls emission character, from localized, quantum-dot-like in thin films to delocalized in thicker films.

Together, the demonstrated structural continuity and near-perfect lattice matching with GaP and Si highlight the strong potential of Ga2Se3/GaP heterostructures for advanced optoelectronic devices, while also providing a clear pathway for the tailored integration of GaSe into future layered optoelectronic systems based on a silicon platform.

Methods

Metal-organic chemical vapor deposition

The growth of GaxSey was conducted using an AIXTRON AIX 200 GFR system via metal–organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), featuring a horizontal reactor design. A schematic representation of the reactor and gas supply system is provided in Fig. S10. Metal–organic compounds were employed as precursors. Hydrogen (H2) gas was bubbled through the liquid precursors, carrying the saturated vapor into the reactor. The partial pressures for this study were calculated using the following equation:

In this equation, Qs represents the carrier gas flow through the bubbler into the reactor, Qtot is the total gas flow into the reactor, Pv is the vapor pressure of the liquid precursor, PC is the pressure in the bubbler, and PR is the reactor pressure. For this study, DiPSe and TTBGa or TEGa were used as the selenium and gallium precursors, respectively. All precursors were sourced from Dockweiler Chemicals GmbH.

During the growth process, the bubblers were maintained at a temperature of 20 °C and 500 mbar for DiPSe and TEGa, and at 200 mbar for TTBGa. The decomposition temperatures T50 for the gallium precursors were 140 °C for TTBGa and 250 °C for TEGa80. In contrast, the selenium precursor, DiPSe, incorporates Se effectively at 496 °C under 133 mbar, which necessitates higher temperatures at a reactor pressure of 50 mbar54.

The substrates used in this study included commercially available 2-inch c-plane oriented sapphire substrates from SITUS Technicals GmbH and 20-in., (100)-oriented GaP/Si wafers from NAsP III/V GmbH. These substrates were cleaved and placed on a graphite susceptor positioned at the center of the reactor for each growth run to ensure consistent and stable conditions. Additionally, the susceptor was rotated during growth to promote uniformity deposition across the wafer surface. Prior to precursor introduction, the Al2O3 substrates were heated at the growth temperature for 10 minutes to remove any potential contaminants. For the GaP/Si substrate, a GaP buffer layer was grown at 675 °C with a thickness of approximately 4 nm to achieve a smooth surface. The precursors trertiary-butylphosphine (TBP) and TEGa were employed for the GaP buffer layer, both commercially available from Dockweiler Chemicals GmbH.

Subsequently, the temperature was reduced to the desired growth temperature, and phosphorus was supplied to stabilize the GaP layer before the GaxSey growth commenced. All samples were grown in continuous mode, with the gallium and selenium sources supplied simultaneously. Growth times varied between 3 and 120 min, with the temperature set between 450 °C and 600 °C. The total gas flow during all experiments was maintained at a constant rate of 6800 sccm. The carrier gas flow through the gallium bubbler was adjusted to maintain a constant partial pressure of 3.5 × 10−3 mbar for TEGa and between 59.5 and 66.5 × 10−6 mbar for TTBGa. The carrier gas flow through the selenium bubbler was varied to induce the phase transition from GaSe to Ga2Se3. For all experiments, the reactor pressure was kept at 50 mbar.

Mass spectroscopy

All decomposition experiments in this work were carried out in an AIXTRON AIX 200 GFR reactor using DiPSe as selenium precursor, either under unimolecular conditions or in combination with the gallium precursors TEGa and TTBGa. The experiments were conducted under conditions representative of epitaxial growth, with a constant total gas flow of 6800 sccm, a reactor pressure of 50 mbar, with H2 as carrier gas, and active rotation of the susceptor. For the bimolecular experiments, the partial pressures of TEGa and TTBGa were adjusted to values typically employed during growth processes.

The decomposition of DiPSe was followed as a function of the susceptor surface temperature, which was calibrated using the phase transition of an Al-coated Si reference substrate. The resulting decomposition curves exhibited the expected sigmoidal behavior and were analyzed by fitting with a Boltzmann function to determine the characteristic decomposition temperature T50. From repeated measurements and calibration accuracy, the uncertainty in T50 is estimated to be within ±10 °C.

Gas-phase products were analyzed with a quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer (iTrap, Carl Zeiss SMT GmbH) coupled to the MOVPE system via a bypass line. Process gas was sampled through a quartz nozzle located directly above the center of the susceptor and injected into the ion trap in short pulses using an atomic layer deposition-type valve, enabling millisecond inlet. Within the ion trap, analytes were ionized by 70 eV electron impact. The generated ions were confined in a Paul trap consisting of a ring electrode and two end-caps, where an applied radio-frequency field induced mirror image currents in the electrodes. These signals were processed by fast Fourier transform to obtain mass spectra with acquisition times below 2 s, allowing real-time tracking of the decomposition behavior. Furthermore, the setup enabled selective removal of specific mass-to-charge ranges using SWIFT excitation, thereby enhancing sensitivity. A detailed description of the system can be found in ref. 101.

Atomic force microscopy

Two different atomic force microscopes (AFMs) were used to analyze the surface topography of the samples: a Digital Instruments III and an Alphacen 300. The latter of the two is commercially available from Nanosurf. The raw data from the AFM measurements were processed and analyzed using the Gwyddion software. For these measurements, commercially available probes from MikroMasch Europe, with a nominal tip radius of less than 7 nm, were utilized.

Confocal Raman spectroscopy

Confocal Raman spectroscopy was performed using a Horiba XPloRA Plus Raman microscope configured in backscattering geometry. A 100× objective lens with a numerical aperture (NA) of 0.8 was employed, and the excitation wavelength was set to 532 nm. The technique was utilized as a fingerprinting method to confirm the phase composition of the sample. Spectral calibration was conducted using a Si reference, aligning the characteristic Si Raman peak at 520 cm−1. The spectral resolution was limited to approximately ±1 cm−1, constrained by the resolution of the diffraction grating.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy

From selected samples, electron transparent lamellae were prepared in cross-sectional geometry using a JEOL JIB 4601 Ga-FIB. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) measurements were carried out in a double aberration-corrected JEOL JEM-2200FS microscope at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The high-angle ADF (HAADF) imaging mode was used providing so-called Z-contrast. To determine the local composition, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) measurements were carried out using an XFlash 5060 system.

Scanning electron microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Helios 5 Hydra CX, operating in Ultra-High Resolution (UHR) immersion mode. The acceleration voltage and beam current were set to 4 kV and 0.1 nA.

Photoluminescence

The photoluminescence (PL) measurements were conducted using the 442 nm emission from a He-Cd laser (Kimmon IK5352R-D) with a power of 5 and 3200 µW to excite the Ga2Se3 sample and GaP/Si substrate, respectively. Neutral density filters were used in order to adjust the excitation power. The laser spot was focused onto the samples using an infinity-corrected apochromatic microscope objective (Mitutoyo) with a magnification of 10×, which also collected the emitted PL. A 500 nm dichroic longpass filter was utilized to separate the PL from the laser and outcouple the former into the detection path. There, the residual laser radiation was removed from the signal by means of a 540 nm longpass absorption filter. Subsequently, the PL was focused onto the entrance-slit of a spectrometer (Andor Kymera). The spectrally resolved signal was then captured using a coupled EMCCD camera (Andor iXon).

During the PL measurements, the samples were mounted inside a gas flow microscopy cryostat (CryoVac Konti Micro), which was evacuated and cooled down to 80 K using liquid nitrogen to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio.

The obtained spectra were corrected using a Fourier bandstop filter in order to remove oscillations present at higher wavelengths, which are caused by an etalon effect inside the detector. Subsequently, residual artifacts observed in the GaP spectra—presumed to originate from the laser source and associated with a low signal-to-noise ratio—were suppressed using a rolling average filter.

Cathodoluminescence

Cathodoluminescence (CL) measurements were carried at a temperature of 20 K out using a customized electron beam lithography system equipped with CL extension and a He-flow cryostat102. An acceleration voltage of 20 kV and a 30 μm aperture were used, resulting in a beam current of 250 pA. The emitted luminescence was collected using a high NA parabolic mirror and directed into a monochromator with a 100 μm entrance slit and equipped with a grating of 300 lines/mm. The signal was recorded with an integration time of 100 ms using a Si CCD. Unlike the PL samples, the sample used for CL measurements was coated with a 5 nm layer of gold to mitigate surface charging effects, which would otherwise suppress the emission within seconds.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the paper and Supplementary Information.

Change history

16 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00649-y

References

NobelPrize.org. The Nobel Prize in Physics 2010. (2010).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Lo Gerfo Morganti, G. et al. Transient ultrafast and negative diffusion of charge carriers in suspended MoSe2 from multilayer to monolayer. Nat. Commun. 16, 5184 (2025).

Bergmann, M. et al. Excitons in epitaxially grown WS2 on Graphene: a nanometer-resolved EELS and DFT study (2024).

Khan, M. A. & Leuenberger, M. N. Optoelectronics with single layer group-VIB transition metal dichalcogenides. Nanophotonics 7, 1589–1600 (2018).

Bhimanapati, G. R. et al. Recent Advances in Two-Dimensional Materials beyond Graphene. ACS Nano 9, 11509–11539 (2015).

Zallo, E. et al. Two-dimensional single crystal monoclinic gallium telluride on silicon substrate via transformation of epitaxial hexagonal phase. npj 2D Mater. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-023-00390-4 (2023).

Hilse, M. et al. Mixed polytype/polymorph formation in InSe films grown by molecular beam epitaxy on GaAs(111)B. npj 2D Mater. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00535-7 (2025).

Yu, M. et al. Quasi-Van der Waals epitaxial growth of γ‘-GaSe nanometer-thick films on GaAs(111)B substrates. ACS Nano 18, 17185–17196 (2024).

Maßmeyer, O. et al. Synthesis of 2D gallium sulfide with ultraviolet emission by MOCVD. Small (Weinh. der Bergstr., Ger.) 20, e2402155 (2024).

Song, S. et al. Indium selenides for next-generation low-power computing devices, 17.03.2025.

Leisgang, N. et al. Optical second harmonic generation in encapsulated single-layer InSe. AIP Adv. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5052417 (2018).

Grzonka, J., Claro, M. S., Molina-Sánchez, A., Sadewasser, S. & Ferreira, P. J. Novel Polymorph of GaSe. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202104965 (2021).

Ho, C.-H. Ga2Se3 defect semiconductors: the study of direct band edge and optical properties. ACS Omega 5, 18527–18534 (2020).

Zheng, F. et al. Thermodynamic optimization of the Ga–Se system. Calphad 32, 432–438 (2008).

Jung, C. S. et al. Red-to-ultraviolet emission tuning of two-dimensional gallium sulfide/selenide. ACS Nano 9, 9585–9593 (2015).

Park, K.-H. et al. Optical properties of Ga2Se3:Co2+ single crystals. Solid State Commun. 70, 971–974 (1989).

Abdal-Rahman, M. & Shaikh, H. A. E. Photoelectric properties of single crystals. J. Phys. D 29, 889–892 (1996).

Park, K. et al. GaAsSe ternary alloy nanowires for enhanced photoconductivity. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 3908–3915 (2019).

Peressi, M. & Baldereschi, A. Structural and electronic properties of Ga2Se3. J. Appl. Phys. 83, 3092–3095 (1998).

Springford, M. The luminescence characteristics of some group III-VI compounds. Proc. Phys. Soc. 82, 1020–1028 (1963).

Okamoto, T., Yamada, A., Konagai, M. & Takahashi, K. Polarized photoluminescence in vacancy-ordered Ga2Se3. J. Cryst. Growth 138, 204–207 (1994).

Liu, C.-W. et al. Substrate-induced strain in 2D layered GaSe materials grown by molecular beam epitaxy. Sci. Rep. 10, 12972 (2020).

Diep, N. Q. et al. Growth mode transition in two-dimensional GaSe on three-dimensional GaN/sapphire platform: implication for self-powered photodetection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 3042–3049 (2024).

Chen, M.-W. et al. Large-grain MBE-grown GaSe on GaAs with a Mexican hat-like valence band dispersion. npj 2D Mater. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-017-0047-x (2018).

Huang, A., Shi, W. & Wang, Z. Optical properties and photocatalytic applications of two-dimensional Janus group-III monochalcogenides. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 11388–11396 (2019).

Hu, P., Wen, Z., Wang, L., Tan, P. & Xiao, K. Synthesis of few-layer GaSe nanosheets for high performance photodetectors. ACS Nano 6, 5988–5994 (2012).

Tonndorf, P. et al. Single-photon emitters in GaSe. 2D Mater. 4, 21010 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Strong second-harmonic generation in atomic layered GaSe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7994–7997 (2015).

Rakhlin, M. et al. Allotropic Ga2Se3/GaSe nanostructures grown by van der Waals epitaxy: narrow exciton lines and single-photon emission. Nanoscale 16, 2039–2047 (2024).

Isik, M. & Gasanly, N. M. Investigation of structural and optical characteristics of thermally evaporated Ga2Se3 thin films. Vacuum 179, 109501 (2020).

Guo, S.-P. et al. Large second harmonic generation (SHG) effect and high laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) observed coexisting in gallium selenide. Angew. Chem. 131, 8171–8175 (2019).

Jin, H. et al. Data-driven systematic search of promising photocatalysts for water splitting under visible light. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 5211–5218 (2019).

George, A. et al. Controlled growth of transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers using Knudsen-type effusion cells for the precursors. J. Phys. Mater. 2, 16001 (2019).

Shi, Y., Li, H. & Li, L.-J. Recent advances in controlled synthesis of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides via vapour deposition techniques. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2744–2756 (2015).

Ji, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, Z. Chemical vapour deposition of group-VIB metal dichalcogenide monolayers: engineered substrates from amorphous to single crystalline. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2587–2602 (2015).

Li, H., Wu, J., Yin, Z. & Zhang, H. Preparation and applications of mechanically exfoliated single-layer and multilayer MoS2 and WSe2 nanosheets. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1067–1075 (2014).

Magda, G. Z. et al. Exfoliation of large-area transition metal chalcogenide single layers. Sci. Rep. 5, 14714 (2015).

Stringfellow, G. B. Development and current status of organometallic vapor phase epitaxy. J. Cryst. Growth 264, 620–630 (2004).

Okamoto, H. Ga-Se (Gallium-Selenium). J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 30, 658 (2009).

Gillan, E. G. & Barron, A. R. Chemical vapor deposition of hexagonal gallium selenide and telluride films from cubane precursors: understanding the envelope of molecular control. Chem. Mater. 9, 3037–3048 (1997).

Ng, T. L. et al. Metal-organic vapor phase epitaxial growth of cubic Gallium selenide, Ga 2 Se 3. Chem. Vap. Depos. 2, 185–189 (1996).

Maung, N., Fan, G., Ng, T.-L., Williams, J. O. & Wright, A. C. A study of the mechanism of the reaction of trimethylgallium with hydrogen selenide. J. Mater. Chem. 9, 2489–2494 (1999).

Martin, M. et al. 200 mm-scale growth of 2D layered GaSe with preferential orientation. APL Mater. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0087684 (2022).

Lee, C. H. et al. Molecular beam epitaxy of 2D-layered gallium selenide on GaN substrates. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4977697 (2017).

D’Ans, J. Taschenbuch für Chemiker und Physiker (Springer, Berlin, 1943).

Kunert, B., Németh, I., Reinhard, S., Volz, K. & Stolz, W. Si (001) surface preparation for the antiphase domain free heteroepitaxial growth of GaP on Si substrate. Thin Solid Films 517, 140–143 (2008).

Liebich, S. et al. Monolithic integration of Ga(NAsP) laser on Si(001) substrate, pp. 1054–1055.

Zimprich, M. Optimierung Ga(NAsP)-basierender Heterostrukturen auf Si-Substrat für Laseranwendungen. Dissertation. Philipps-Universität Marburg.

Kröner, M. Growth and Optimisation of Ga(N, As, P, Sb)/(B, Ga)(As, P) Heterostructures for Laser Applications on Si (001). Dissertation. Philipps-Universität Marburg.

Limame, I. et al. High-quality single InGaAs/GaAs quantum dot growth on a silicon substrate for quantum photonic applications. Opt. Quantum 2, 117 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Controlled vapor phase growth of single crystalline, two-dimensional GaSe crystals with high photoresponse. Sci. Rep. 4, 5497 (2014).

Chubarov, M. et al. Wafer-scale epitaxial growth of unidirectional WS2 monolayers on sapphire. ACS Nano 15, 2532–2541 (2021).

Bourret, E. D., Zach, F. X., Yu, K. M. & Walker, J. M. Growth and characterization of ZnSe grown by organometallic vapor phase epitaxy using diisopropyl selenide and diethyl zinc. J. Cryst. Growth 147, 47–54 (1995).

Bevan, M. J., Shih, H. D., Liu, H. Y., Syllaios, A. J. & Duncan, W. M. Growth of high quality ZnSe on closely lattice-matched InGaAs substrates by metal organic chemical vapor deposition. J. Cryst. Growth 170, 467–471 (1997).

Shenai-Khatkhate, D. V. Ultrapure Metal-Organic Precursors for MOVPE. In Metalorganic Vapor Phase Epitaxy (MOVPE), (eds S. Irvine & P. Capper) (Wiley, 2019), pp 467–506.

Patnaik, S. et al. Decomposition of allylselenium sources in the metalorganic chemical vapor deposition of zinc selenide. Chem. Mater. 5, 305–310 (1993).

SPINDLER, C. Optical Detection of Deep Defects in Cu(In,Ga)Se2.

Grundmann, A. et al. Impact of synthesis temperature and precursor ratio on the crystal quality of MOCVD WSe2monolayers. Nanotechnology https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/acb947 (2023).

Grundmann, A. O. Entwicklung von Gasphasendepositionsprozessen zur Herstellung von Übergangsmetalldichalkogenid-Monolagen und Heterostrukturen für optoelektronische Bauelemente. (RWTH Aachen University, 2023).

Rodriguez, R. D. et al. Selective Raman modes and strong photoluminescence of gallium selenide flakes on sp2 carbon. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Nanotechnol. Microelectron. https://doi.org/10.1116/1.4881995 (2014).

Avdienko, P. et al. Structural and optical properties of GaSe/GaAs(001) layers grown by molecular beam epitaxy. Acta Phys. Pol. A 136, 608–612 (2019).

Diep, N. Q. et al. Screw-dislocation-driven growth mode in two dimensional GaSe on GaAs(001) substrates grown by molecular beam epitaxy. Sci. Rep. 9, 17781 (2019).

Bletskan, D. I., Kabatsii, V. N. & Kranjčec, M. Photoelectric properties of ordered-vacancy Ga2Se3 single crystals. Inorg. Mater. 46, 1290–1295 (2010).

Emde et al. MOCVD growth of Ga2Se3 on GaAs(100) and GaP(100): a Raman study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 104-105, 575–579 (1996).

Märkl, A. et al. Investigation of Se capping of epitaxial Ga 2 Se 3 layers. Surf. Sci. 331-333, 631–635 (1995).

Finkman, E., Tauc, J., Kershaw, R. & Wold, A. Lattice dynamics of tetrahedrally bonded semiconductors containing ordered vacant sites. Phys. Rev. B 11, 3785–3794 (1975).

Vural, S. & Sari, Ö Synthesis and characterization of SDS assistant α-alumina structures and investigation of the effect of the calcination time on the morphology. Colloid Polym. Sci. 297, 107–114 (2019).

Kadleı́ková, M., Breza, J. & Veselý, M. Raman spectra of synthetic sapphire. Microelectron. J. 32, 955–958 (2001).

Seo, H. W., Bae, S. Y., Park, J., Yang, H. & Kim, S. Synthesis of gallium phosphide nanowires via sublimation method. Chem. Commun. 21, 2564–2565 (2002).

Dubey, R. L., Dubey, S. K., Yadav, A. D., Sulania, I. & Kanjilal, D. Raman scattering and FTIR studies of 100 MeV Fe 9+ ion-irradiated gallium phosphide. Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids 166, 743–748 (2011).

Abdullayeva, S. H. et al. GaInPN/Si heterostructure growth by metal-organic vapour phase epitaxy. Fiz. (Baku) 15, 18–23 (2009).

Lee, W.-J. & Chang, Y.-H. Growth without postannealing of monoclinic VO2 thin film by atomic layer deposition using VCl4 as precursor. Coatings 8, 431 (2018).

Söllner, J. et al. Production scale MOCVD growth of II–VI semiconductors. J. Cryst. Growth 184-185, 158–162 (1998).

Noh, G. et al. Large memory window of van der Waals heterostructure devices based on MOCVD-grown 2D layered Ge4 Se9. Adv. Mater. (Deerfield Beach, Fla.) 34, e2204982 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. Phase-centric MOCVD enabled synthetic approaches for Wafer-Scale 2D tin selenides. Adv. Mater. (Deerfield Beach, Fla.) 36, e2400800 (2024).

Shi, X.-L., Tao, X., Zou, J. & Chen, Z.-G. High-performance thermoelectric snse: aqueous synthesis, innovations, and challenges. Adv. Sci. (Weinh., Baden.-Wurtt., Ger.) 7, 1902923 (2020).

Kim, C., Kurosaki, K., Ishimaru, M., Muta, H. & Yamanaka, S. Effect of vacancy distribution on the thermal conductivity of Ga2Te3 and Ga2Se3. J. Elec Mater. 40, 999–1004 (2011).

Gnatenko, Y. P., Skubenko, P. A., Kovalyuk, Z. D. & Kaminskii, V. M. An isothermal annealing effect on the luminescence spectra of GaSe single crystals. Phys. Status Solidi B https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.2221230155 (1984).

Maßmeyer, O. et al. Revealing the significance of catalytic and alkyl exchange reactions during GaAs and GaP growth by metal organic vapor phase epitaxy. ACS Omega 6, 28229–28241 (2021).

Tuktamyshev, A. Droplet Epitaxy Quantum Dots on GaAs (111)A Substrates for Quantum Information Applications. Dissertation. (Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, 2021).

Goldan, A. H. et al. Molecular structure of vapor-deposited amorphous selenium. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4962315 (2016).

Yannopoulos, S. N. Structure and photo-induced effects in elemental chalcogens: a review on Raman scattering. J. Mater. Sci. 31, 7565–7595 (2020).

Poborchii, V. V., Kolobov, A. V., Caro, J., Zhuravlev, V. V. & Tanaka, K. Polarized Raman spectra of selenium species confined in nanochannels of AlPO4-5 single crystals. Chem. Phys. Lett. 280, 17–23 (1997).

Volz, K. et al. GaP-nucleation on exact Si (001) substrates for III/V device integration. J. Cryst. Growth 315, 37–47 (2011).

Syshchyk, O. et al. Deep-level transient spectroscopy of GaAs nanoridge diodes grown on Si substrates. Phys. Rev. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.14.024093 (2020).

Okamoto, T., Yamada, A., Konagai, M., Takahashi, K. & Suyama, N. Characterization of the interface between Ga2Se3 epitaxial layer and (100)GaP substrate by transmission electron microscopy. In Control of Semiconductor Interfaces (Elsevier, 1994), pp 467–470.

Sorokin, S. V. et al. Molecular beam epitaxy of layered group III metal chalcogenides on GaAs(001) substrates. Materials (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163447 (2020).

Kojima, N. et al. Molecular beam epitaxial growth and characterization of epitaxial GaSe films on (001)GaAs. J. Cryst. Growth 150, 1175–1179 (1995).

Kojima, N., Sato, K., Yamada, A., Konagai, M. & Kiyoshi Takahashi, K. T. Epitaxial growth of GaSe films by molecular beam epitaxy on GaAs(111), (001) and (112) substrates. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 33, L1482 (1994).

Claro, M. S., Grzonka, J., Nicoara, N., Ferreira, P. J. & Sadewasser, S. Wafer-scale fabrication of 2D β-In 2 Se 3 photodetectors. Adv. Opt. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202001034 (2021).

Wu, S.-K. et al. Control of lateral epitaxial nanothin β-In 2 Se 3 grown by molecular beam epitaxy: implications in fabricating of next-generation transistors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 20445–20453 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Epitaxial growth of few-layer β-In2Se3 thin films by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. J. Cryst. Growth 533, 125471 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Diffusion-controlled epitaxy of large area coalesced WSe2 monolayers on sapphire. Nano Lett. 18, 1049–1056 (2018).

Brauer, G. (ed.). Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry. 2nd ed. (Academic Press, New York, 1963).

Yang, J. et al. Low threading dislocation density and antiphase boundary free GaAs epitaxially grown on on-axis Si (001) substrates. Nanoscale 14, 17247–17253 (2022).

Untila, D. et al. Photoluminescence properties of lamellar nano-composites obtained by Cd intercalation of GaSe and GaSe:Eu single crystals. Phys. Status Solidi C. 12, 65–69 (2015).

Luo, W. et al. Improving strain-localized GaSe single photon emitters with electrical doping. Nano Lett. 23, 9740–9747 (2023).

Helversen et al. Temperature dependent temporal coherence of metallic-nanoparticle-induced single-photon emitters in a WSe 2 monolayer. 2D Mater. 10, 45034 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Revealing the biexciton and trion-exciton complexes in BN encapsulated WSe2. Nat. Commun. 9, 3719 (2018).

Nattermann, L. et al. An experimental approach for real time mass spectrometric CVD gas phase investigations. Sci. Rep. 8, 319 (2018).

Rodt, S. & Reitzenstein, S. High-performance deterministic in situ electron-beam lithography enabled by cathodoluminescence spectroscopy. Nano Express 2, 14007 (2021).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) via SFB 1083 (Project number 223848855), INST 131/795-1 FUGG, and via SPP 2244 (Project number 443416027). The authors thank Dockweiler Chemicals GmbH, Marburg, for collaboration regarding precursor development and purification.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.F.L. and N.G. grew the samples using the MOCVD setup and performed AFM and Raman measurements. N.F.L. performed mass spectrometry and wrote the manuscript. D.M. performed PL measurements. I.L. performed CL measurements, which were evaluated by M.B. J.B. performed SEM and TEM measurements, and A.B. performed additional TEM measurements. K.V., M.G., S.R., M.K. and R.G. supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Langlotz, N.F., Günkel, R., Muth, D. et al. MOCVD growth of covalent and 2D GaxSey: a phase validation and characterization. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 105 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00635-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00635-4