Abstract

Autonomous artificial intelligence (AI) for pediatric diabetic retinal disease (DRD) screening has demonstrated safety, effectiveness, and the potential to enhance health equity and clinician productivity. We examined the cost-effectiveness of an autonomous AI strategy versus a traditional eye care provider (ECP) strategy during the initial year of implementation from a health system perspective. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was the main outcome measure. Compared to the ECP strategy, the base-case analysis shows that the AI strategy results in an additional cost of $242 per patient screened to a cost saving of $140 per patient screened, depending on health system size and patient volume. Notably, the AI screening strategy breaks even and demonstrates cost savings when a pediatric endocrine site screens 241 or more patients annually. Autonomous AI-based screening consistently results in more patients screened with greater cost savings in most health system scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinal disease (DRD) is one of the most common complications of diabetes and the leading cause of blindness in working-age adults1. Early screening and diagnosis of DRD can significantly reduce the risk of vision loss and blindness from DRD. For this reason, professional societies such as the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommend regular diabetic eye exams2,3. Yet adherence remains low due to many reasons, including inequitable access, cost, burden of an additional visit, and ophthalmic availability for screening, particularly in rural and low resource settings4. With DRD screening rates as low as 20% nationwide, health systems and medical practices are considering alternative methods to increase screening access and adherence4.

First receiving De Novo authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2018, autonomous AI systems—defined as machine learning- based devices capable of making clinical decisions without physician or human oversight5—have demonstrated efficacy in diagnosing referable DRD at the point of care (in primary care and endocrine offices), improving diabetic eye exam completion rates, reducing health disparities in underserved minority populations6, and increasing clinician productivity7. Previous analyses have also shown that autonomous AI exams for the detection of DRD are effective compared to standard eye care provider (ECP) exams, leading to improved visual outcomes at the population level8. Additionally, autonomous AI systems have demonstrated greater cost- savings from the patient perspective and have been shown to be cost saving in socialized healthcare systems and in a rural primary care network in Australia when compared to teleretinal screening programs and office-based screenings9,10,11,12,13,14. However, no study, to our knowledge, has examined the cost-effectiveness from the perspective of a health system in the United States (U.S.).

The introduction of new technologies, including autonomous AI, into routine health care delivery can be challenging due to changing practice patterns and the financial and human resources required to integrate new technologies into clinical practice15,16. Consideration of the financial expenditures, particularly in terms of the cost of technology integration and maintenance and total cost of care, as well as screening effectiveness, patient care benefits, and operational value, even without considering reimbursement, are important in determining whether and how to implement these systems. We hypothesize that autonomous AI for DRD screening in youth will be cost-effective for the health system, compared to the standard eye care provider (ECP) exams.

Results

Screening cost-effectiveness

Our base-case analysis shows that the expected cost of the AI strategy is between $19,368 and $133,900, compared to the expected cost of the ECP strategy, which is between $8927 and $357,072. Thus, excluding insurance reimbursements, the AI strategy results in additional costs of up to $10,441 and potential cost savings of up to $240,972 depending on the size of the health system. Regarding effectiveness, the AI strategy consistently results in more patients being screened, ranging between 43 and 1724 additional patients screened annually, depending on patient volume (Table 1).

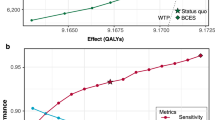

As expected, the ICER varies with the size of the health system. In general, the ICER decreases as the patient volume per site increases. For example, in a medium-sized health system with an annual patient volume of 400 patients spread across 2 sites, the ICER is $36 per additional patient screened but decreases to –$33 (i.e., cost saving) when the annual patient volume increases to 600 patients across both sites. Figure 1 shows these ICER values in relation to the benchmark willingness-to-pay threshold of $413 per DRD case averted (Fig. 1). Ultimately, the AI screening strategy reaches a break-even point and becomes cost-saving when a single endocrine site has 241 or more patients per year eligible for DRD screening, under base-case assumptions. Beyond this volume, the operational efficiencies gained through AI screening offset the cost of implementation (Fig. 1).

This graph illustrates the necessary annual screening volume (x-axis) and health system size (indicated by line color) for the autonomous AI screening strategy to be cost-effective compared to the ECP strategy. ICER values falling below the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of $413 (dashed line) indicate that the autonomous AI strategy is cost-effective.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses reveal that ICERs for DRD screening are influenced by AI cost parameters, primarily the cost of AI maintenance that encompass troubleshooting, software updates, and technical support (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). At a WTP threshold of $413, the AI screening strategy is preferred to the ECP strategy when the annual cost of AI maintenance remains below certain thresholds that depend on the scale of the health system. For a single site with 100 patients, the AI strategy is cost-effective as long as the AI support cost remains below $17,360. However, the threshold increases to $92,838 for a single site with 400 patients, and the AI strategy begins to dominate across all cost parameters when the annual patient volume per site reaches 600 patients (Supplementary Table 2).

After running 10,000 simulations for the probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), the AI strategy was found to be cost-effective (i.e., generating an ICER < WTP of $413 per patient) for a small health system of 100 patients in 47% of iterations. Since an iteration represents a specific health system configuration, this percentage translates to “47% of health system configurations.” At this patient volume, the probability of cost-effectiveness reaches 95% only at a willingness-to-pay threshold of at least $5000. Nevertheless, the likelihood of cost-effectiveness increases with the size of the health system. For a medium-sized health system (600 patients across 2 sites), the probability rises to 86% for our base-case WTP of $413, and for a large health system (4000 patients across 3 sites), it reaches 98% (Supplementary Table 1).

Cost effectiveness of adherence to follow up eye exams

For patients who successfully completed their diabetic eye exams and screened positive through either strategy (ECP or AI) or whose images were insufficient for interpretation by AI, we evaluated the cost-effectiveness of adherence to follow-up with an ECP within and outside the health system. Again, excluding reimbursement, the base-case analysis shows that the cost difference of follow-up between the AI and ECP screening strategies can range from +$3047 to +$12,342 for a small health system, −$26,459 to +$13,770 for a medium-sized health system, and −$262,560 to +$16,615 for a large health system, depending on whether the patient follows up within or outside the health system. Regardless of referral route, AI is expected to increase follow-up rates by 11.72 times over ECP (Supplementary Table 3).

Paralleling the trends observed for the cost-effectiveness of screening, ICERs for follow-up adherence tend to decrease as the size of a health system increases (i.e., more cost effective and cost savings). For small health systems, the additional cost per patient who follows up with an ECP after an initial screening using the AI strategy ranges from $309 to $1106 for within-system follow-up and $137 to $934 per patient for outside-system follow-up. In medium-sized health systems, each additional adherent patient results in maximum cost of $309 to savings of $223 for within-system follow-up, and cost of $137 to savings of $395 for outside system follow-up. Finally, large health systems can see cost of $149 to savings of $370 for each additional patient follow-up internally, and savings ranging from $23 to $588 per patient follow-up externally (Table 2).

A PSA of the follow-up model indicates that AI is cost-effective in 14% to 95% of cases, depending on the scenario. As with the DRD screening model, the likelihood that the AI strategy is more cost-effective than the ECP strategy for ensuring follow-up adherence increases with the size of the health system (Supplementary Table 4). Therefore, there is a higher level of confidence that AI is more cost-effective in larger health systems.

For follow-up adherence, ICER values are sensitive to a number of cost parameters, especially when patients follow up with an ECP within versus outside the health system (Tables 3 and 4). For instance, AI proves to be comparatively cost-effective for a small health system with an annual patient volume of 200 if the per site AI start-up cost is less than $21,608, integration cost is less $5322, or support cost is less than $12,322. For this sized health system, AI is also cost-effective if the ECP exam cost exceeds $144. However, for the same patient volume referred outside the health system, fewer parameters drive the ICER over the WTP threshold. Moreover, AI remains cost-effective over a broader range of parameter values when considering external referrals compared to internal referrals. This indicates that the thresholds for external referrals are more favorable toward AI being the cost-effective option. Additionally, as the scale of the health system increases, AI demonstrates greater resilience to changes in parameter values for larger health systems.

Discussion

Recent research indicates a growing, yet cautious, adoption of FDA-cleared AI, especially autonomous AI, into routine healthcare practices17, highlighting a critical challenge of scaling medical AI. Given that in many cases, health systems are responsible for the acquisition and implementation of such AI, it is essential to assess the cost-effectiveness of these devices from the perspective of the health systems themselves. This perspective is critical to making informed decisions about the integration of AI into health care. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the cost-effectiveness of operationalizing an autonomous AI strategy for DRD screening contextualized within a U.S. health system.

Using a WTP threshold of $413 per averted case of DRD as a benchmark, our base-case analysis shows that the AI strategy, compared to the ECP standard of care, results in more patients screened and completing follow-up exams at an incremental cost for smaller health systems and cost savings for larger health systems: For a single pediatric endocrine practice with a 100 patients annually eligible for DRD screening, the incremental cost of the AI strategy compared to the ECP strategy is $242 per additional patient screened and $1106 per additional patient follow-up within the health system and $934 for follow-up outside the health system. However, cost effectiveness improves with increasing health system scale, and the AI strategy becomes cost-savings (i.e., negative ICER values) at larger scale: A medium-sized system consisting of 1-2 endocrine sites with a total of 400-600 patients eligible annually for DRD screening achieves baseline cost-effectiveness at +$36 to −$102 (representing cost savings of up to $102) per additional patient screened, $309 to −$223 (cost savings up to $223) per additional follow-up within the system, and $137 to −$395 (cost savings up to $395) per additional follow-up outside the system.

We evaluated both strategies against stringent standards. Our model includes several cost parameters that a health system would realistically encounter in the initial year of implementation; even though, these parameters may not apply to every setting. Due to uncertainties in AI costs stemming from lack of access to proprietary information, the complexity of IT integration, and any disruption to clinical and operational workflows, we conducted deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses over wide cost intervals for setup, integration, and vendor support costs of the AI system (Table 5). Our findings demonstrate that the cost-effectiveness of the AI strategy varies significantly with health system size. Specifically, across both screening and follow-up models, AI was shown to be cost-effective in 14-42% iterations of the PSA for smaller health systems, while this probability increased substantially to 51-95% for larger health systems. This probability indicates that across the diverse range of health systems in the United States encountering a multitude of costs, AI is likely to be cost-effective for 14-42% of smaller health systems, increasing to 51-95% for larger health systems. These results suggest that larger health systems may have a distinct advantage in implementing AI technology, potentially due to economies of scale and greater resource availability.

The results of the deterministic sensitivity analysis indicate that AI cost parameters significantly influence the cost-effectiveness of AI for DRD screening and follow-up care, with increasing thresholds and cost parameter tilting in favor of AI as the size of the health system increases (Tables 3 and 4). Estimation of these costs should take into account varying clinical labor costs by geography and other factors.

Our analysis shows that the AI strategy breaks even and becomes cost-saving at a threshold of 241 patients eligible for screening per site, an annual patient volume less than that of a typical pediatric endocrine clinic18. Although we explicitly excluded revenue from our model19, health systems operating under both fee- for- service and value-based care20 could potentially break even and recoup their initial investment at even lower patient volumes if insurance reimbursement revenue were included. Accounting for reimbursement would effectively mitigate the implementation and vendor support costs of the AI system, allowing for much faster cost recovery. This mitigation is particularly important when comparing the cost-effectiveness of AI for follow-up care within the health systems versus outside the system. Since our model considers internal follow-up with an ECP as a cost to the health system—a cost avoided by external referrals—AI appears less cost-effective for internal follow-ups. However, these internal costs could be offset by ophthalmic care reimbursements. Thus, the lower cost-effectiveness of internal referrals should not outweigh the benefits of keeping patients within the health system, which allows for better continuity of care, potentially improving outcomes and reducing long-term costs.

Under value-based care, meeting quality standards and MIPS/HEDIS measures during health screenings for individuals aged 18-21 further presents an opportunity for health systems to receive financial incentives, thereby increasing the overall cost-effectiveness of adopting an AI strategy. These opportunities, in turn, would further tilt the ICER in favor of the AI strategy.

While beyond the scope of this study, we acknowledge the potential downstream productivity gains that could increase the cost-effectiveness of autonomous AI systems for DRD screening7. By handling routine DRD screening, autonomous AI systems allow ophthalmologists to focus their expertise on more complex cases. These systems can also improve efficiency by screening and identifying more patients for early intervention, increasing health system capacity, leading to better clinical outcomes and potentially reducing long term healthcare costs and expenditures7,8. However we recognize that the benefits of AI are dependent on patient and provider inclination for AI. While “algorithmic aversion” may be a potential issue, where the patient and/or provider may prefer human judgment over algorithmic decision-making even when the algorithms have been shown to perform better, we did not find evidence of this in published literature7.

One of our goals for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of autonomous AI systems for DRD care was to explore the potential of these systems to maximize health equity by expanding access to care particularly in underserved areas with limited availability of eye care professionals, financial resources, and access to care. Autonomous AI systems can address health disparities by bringing eye care to these areas. However, the resources needed for AI-implementation may prevent adoption in low-resource settings, further exacerbating the digital divide and health disparities. Opportunities to improve affordability through lower hardware costs and smaller clinical footprint, combined with more sophisticated algorithms has the potential to improve accessibility even more.

To evaluate the AI strategy under the most stringent criteria, we considered a comprehensive range of costs that a health system might encounter in implementation, even though not all of these costs may be a factor in every real-world implementation scenario. Thus, our results likely underestimate the true cost-effectiveness. Our analysis was also limited to the initial year, so IT integration costs in subsequent years may be negligible. This could further prove the AI strategy’s potential to be even more cost-effective and cost-savings. While using AI to screen for DRD in primary diabetes care settings is cost-effective, ophthalmologist visits may provide additional benefits for children beyond screening for DRD. Moreover, we modeled health system scale based on patient volume and number of sites, but there are other variables that describe scale.

Future studies could include more granular cost estimates of the screening provided through the AI and ECP strategies using activity-based costing21. It would also be beneficial to conduct cost-effectiveness analyses across different insurance and demographic distributions, locations, and age groups. Furthermore, pediatric patients with diabetes are most likely to receive care in a multidisciplinary diabetes clinic, whereas adults with diabetes may be treated in a primary care or endocrine setting. Thus, future analyses will need to account for both settings in cost-effectiveness studies.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of an autonomous AI screening strategy for DRD from the perspective of a U.S. health system. Our analysis shows that autonomous AI-based screening is a more effective screening strategy compared to the standard ECP- performed eye exam with greater cost-effectiveness for smaller health systems and cost-saving for larger ones. By using a decision model, our study provides a template for health systems to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of emerging technologies. Our hope is that this analysis will assist providers in weighing the value proposition of implementing AI screening and support informed adoption decisions.

Methods

Model design and target population

Using decision analysis22, we evaluated the cost effectiveness of implementing an autonomous AI strategy for the diagnosis of pediatric DRD. Our model considers patients under the age of 21 with Type 1 (T1D) and Type 2 diabetes (T2D) who are cared for by a primary care physician, pediatric endocrinologist, or other licensed provider and who are eligible for DRD screening according to AAO/ADA guidelines2,3.

Our analysis was conducted from the perspective of a health system providing care to patients. We examined cost-effectiveness during the first year that a health system considers adding capacity via AI eye exams at the point of care. Since most youth with diabetes receive care in an endocrine practice, the focus of analysis is either a single or a conglomeration of pediatric endocrine practices operating under one organization.

The two DRD screening strategies are as follows: (1) Autonomous AI: The autonomous AI diabetic eye exam is performed at the pediatric endocrine site during a diabetes care visit. The operator is guided by the AI system to capture retinal images, and the AI algorithm provides an immediate diagnosis of whether DRD or diabetic macular edema (DME) is present. (2) ECP: The standard of care proceeds with a referral to an ECP (either an optometrist or ophthalmologist) who performs indirect ophthalmoscopy and stereo biomicroscopy under pharmacologic dilation within a health system. In both strategies, patients with positive (i.e., referable DR, ETDRS 35 or greater) or insufficient results would be referred to a retina specialist or ophthalmologist for further management and treatment 2,3 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

This study did not require authorization from the institutional review board as it did not involve human subjects.

Parameters estimates and ranges

To comprehensively assess the cost effectiveness of the two alternatives, our model incorporates specific population-level parameters (Table 5) including the prevalence of pediatric DRD, the diagnostic accuracy of the screening modalities including sensitivity and specificity, human behavioral factors as reflected by the probabilities of adherence to follow-up recommendations, health system costs associated with the AI strategy, and reimbursement levels for ECP-conducted DRD exams as a proxy for the costs of the ECP strategy. While Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance reimbursement exist for AI-based DRD screening, because of the variability in reimbursement rate and the fact that many health systems operate through value-based care mechanisms, we excluded reimbursement from our analysis20. Parameter values were obtained from peer-reviewed published literature, empirical observations, and stakeholder interviews with vendors and hospital administrators. Pediatric data were used when available; otherwise, parameter values were taken from adult data. In choosing our base-case estimates, we opted for a conservative approach, with each parameter estimate tilting the analysis against the AI strategy. We also acknowledge that our model incorporates a variety of cost considerations that may not be applicable to every health system; however, these costs were incorporated to evaluate AI against rigorous criteria.

The SEARCH trial estimated the prevalence of DRD among youths with T1D and T2D as 5.6% and 9.1%, respectively23. For the base case, we used the weighted average (6.8%) of these estimates. Other studies have reported divergent prevalence values, ranging as low as 3.4% for T1D and 6% for T2D24 to as high as 20.1% for T1D25 and 51.0% for youth onset T2D26; these varying figures were used for the low and high estimates in sensitivity analyses.

ECPs performing adult eye exams achieve a sensitivity of 33% (estimated 95% CI: 20-50%)27,28,29. In comparison, the three FDA-cleared autonomous AI systems have demonstrably higher sensitivity in detecting DRD, ranging from 87.2% - 93.0% (95% CI: 81.8-97.2%) against a prognostic standard, a proxy for clinical outcome, depending on the sample evaluated30,31,32. Even when applied to pediatric cases, autonomous AI systems have demonstrated higher sensitivity at 85.7% (95% CI: 42.1-99.6%)33.

The specificity of ECP-conducted exams in adults averages 95%28, and the specificity of autonomous AI systems in pediatrics and adults ranges from 79.3-91.36% (95% CI: 74.3-93.72%)30,31,32,33. We used the mean specificity values for the base case and the minimum and maximum values of the 95% CI for the sensitivity analysis.

Diagnosability of the autonomous AI system, defined as the percentage of assessed patients with an interpretable image, ranges from 96.1% and 97.5% for adult and pediatric cases, respectively, and were averaged for base-case estimates30,33. Low and high estimates were derived from the 95% CI of the adult study30.

The model accounts for patient behavioral factors that influence screening acceptance and completion. Among youths, ECP exam acceptance rate averages 52% and can be as high as 72% 34. While some adult cohorts exhibit a screening acceptance probability as low as 15.3%4. Acceptance rates for autonomous AI eye exams average between 95-96.4%33,35. The probability that a patient will follow up with an ECP after receiving a positive result differs between modalities. After a positive result from an ECP exam, the probability of the patient following-up with an in-person ECP visit is 29-95%36, while the probability of follow-up after a positive AI recommendation is 55.4-64%35,37. The parameter ranges reflect the low and high values observed in the literature and in practice.

FDA De Novo- authorized or cleared AI systems incur a range of expenses that vary by device. Most AI vendors offer pricing models that are based on a per patient usage fee or a subscription model with associated setup fees. Furthermore, health systems take on additional expenses to integrate AI into clinical workflows related to change management, process redesign, and IT system integration. Due to limited availability of such proprietary data, we used the geometric mean of $10,000 as the base case, and we assumed a per practice AI acquisition and ongoing vendor support cost range of $1000-100,000. Since the AI acquisition cost is a one-time up-front fee, a 20% amortization rate to account for the depreciation of assets over time was also applied38. Based on stakeholder interviews, we estimated the cost of integrating an AI system with existing clinical workflows and health IT systems to be a geometric mean of $3000 per site (with a range of $1000 to $20,000). All start-up costs and maintenance costs are included in this one-year time horizon.

We assumed an hourly wage of $33 for the AI operator based on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services estimates39 and varied this parameter from $7.25 (the federal minimum wage)40 to $42 (the mean hourly wage of office-based nurses as they may be the ones to operate AI systems in pediatric endocrine practices)41. Frequently, in adult DRD screening, nurse practitioners (with a substantially higher wage), operate the AI; however, that is less common in pediatric endocrine clinics. Based on clinical experience, it is estimated that such operators can complete a maximum of 4 exams per hour33. Another significant cost consideration is the space required to house the AI system. Current AI DRD systems are desktop- based and may be placed in an existing room designed for ancillary services, but in some cases endocrine practices may need additional space for the AI system. Using an average exam room size of 100 sq. ft42 at $28/sq ft43 which is the rental cost based on commercial real estate rates in Baltimore where this analysis was conducted, we estimated an annualized opportunity cost of $2800 for the space required (range of the parameter over $0-8500).

We used the mean CMS reimbursement of $172 as a base case proxy for the cost of an initial DRD exam and follow-up exam with an ECP and the 10th and 90th percentiles ($110 and $240, respectively) for the sensitivity analysis range. Thus, while we did not account for revenue from insurers or patients for providing screening services, our rationale for using the CMS reimbursement as the basis for the cost estimate of the ECP strategy was that it represents the allowed cost of providing the service, including ophthalmic equipment, eye care professional salaries, clinic space and ancillary costs44. Although we recognize there are setup costs associated with training and credentialing ECPs and integrating them into clinical workflows, these costs are assumed to be built into the system and thus are not accounted for in the model, which also tilts the analysis against the AI strategy.

Outcomes and willingness to pay threshold

The primary outcome measure of interest is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of implementing the AI strategy compared to the ECP strategy. ICER is used in decision-analysis models and cost-effectiveness studies to gauge the additional cost associated with a unit increase in effectiveness of one diagnostic strategy compared with another. We defined effectiveness as 1) the additional number of DRD screenings completed and 2) the additional number of patients who followed up with an ECP for further evaluation and treatment. The cost was the total burden to the health system before reimbursement, resulting from the cost and probability estimates in Table 5, so the two ICERs are interpreted as the “marginal financial cost of completing one additional screening with AI, compared with ECP,” and “the marginal financial cost to complete one additional follow up with the ECP among patients screened positive by AI, with respect to ECP.” An ICER value of 0 indicates the point at which the costs of the AI and ECP strategies are equivalent (i.e., the break-even point) and an ICER value less than 0 indicates that the AI strategy is less expensive than the ECP strategy, resulting in cost savings to the health system.

To further rigorously assess the cost-effectiveness of AI strategy, we established a willingness to pay (WTP) benchmark of $413 per averted case of DRD, far below the standard $50,000 threshold45. This conservative ceiling was calculated using the lowest Medicaid reimbursement rate of $28.08 for AI DRD exams46 divided by the most probable prevalence of diabetes-related disease (6.8%)23.

Scenarios

Since the costs associated with the two screening strategies scale with the size of the health system, we modeled a series of scenarios based on practice size estimates of pediatric diabetes volumes: (1) a small endocrine practice with an annual volume of 100-200 pediatric patients due for DRD screening, (2) a medium-sized health system consisting of 1-2 pediatric endocrine sites with a total annual screening volume of 400-600 patients (200-600 patients per site), and (3) a large health system consisting of 3-4 pediatric endocrine sites with a total annual screening volume of 1000-4000 patients (250- ~1333 patients per site)18.

For patients that are identified to have an abnormal diabetic eye exam (by AI or ECP) or whose images are insufficient and thus require referral to an ECP, we examined the cost-effectiveness of follow-up with an ECP and considered two additional scenarios for each sized health system—whether the follow-up with the ECP takes place 1) within the same health system or 2) outside the health system. For example, if the follow-up visit occurs within the health system, then the total cost would include both the initial screening cost based on the modality and the cost of the ECP follow-up visit itself. If the follow-up visit occurs outside the health system, such as at another private practice or hospital system, the total cost would include only the initial screening.

To account for sampling and parameter uncertainties, deterministic and PSA were performed within each of the scenarios using the ranges shown in Table 5. The deterministic sensitivity analysis informs the thresholds where one strategy is preferrable over the other. The PSAprovides a measure of confidence in the outputs of the base-case analysis. To translate the PSA into meaningful terms, we also report the minimum WTP at which the AI strategy achieves 95% cost-effectiveness probability within each scenario. Modeling and sensitivity analyses were performed using the TreeAge Pro software version (TreeAge Pro 2023, Williamstown, MA, USA). The study was conducted from June 2023 to August 2024.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

The model was built using the TreeAge software. No separate code was written to run the model.

References

Bourne, R. R. et al. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe in 2015: Magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 102, 575–585 (2018).

Flaxel, C. J. et al. Diabetic retinopathy preferred practice pattern®. Ophthalmology 127, (2020).

Draznin, B. et al. 14. Children and adolescents: standards of medical care in diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 45, (2022).

Benoit, S. R., Swenor, B., Geiss, L. S., Gregg, E. W. & Saaddine, J. B. Eye Care Utilization among insured people with diabetes in the U.S., 2010–2014. Diabetes Care 42, 427–433 (2019).

Frank, R. A. et al. Developing current procedural terminology codes that describe the work performed by machines. npj Digital Med. 5, 177 (2022).

Liu, T. Y. A. et al. Autonomous artificial intelligence for diabetic eye disease increases access and health equity in underserved populations. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 220 (2024).

Abramoff, M. D. et al. Autonomous artificial intelligence increases real-world specialist clinic productivity in a cluster-randomized trial. npj Dig. Med. 6, 184 (2023).

Channa, R., Wolf, R. M., Abràmoff, M. D. & Lehmann, H. P. Effectiveness of artificial intelligence screening in preventing vision loss from diabetes: A policy model. Npj Digital Med. 6, 53 (2023).

Fuller, S. D. et al. Five-year cost-effectiveness modeling of primary care-based, Nonmydriatic automated retinal image analysis screening among low-income patients with diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 16, 415–427 (2020).

Srisubat, A. et al. Cost-utility analysis of deep learning and trained human graders for diabetic retinopathy screening in a nationwide program. Ophthalmol. Ther. 12, 1339–1357 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Economic evaluation of combined population-based screening for multiple blindness-causing eye diseases in China: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 11, e456–e465 (2023).

Huang, X.-M. et al. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence screening for diabetic retinopathy in rural China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 260 (2022).

Wolf, R. M., Channa, R., Abramoff, M. D. & Lehmann, H. P. Cost-effectiveness of autonomous point-of-care diabetic retinopathy screening for pediatric patients with diabetes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138, 1063 (2020).

Hu, W. et al. Population impact and cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence-based diabetic retinopathy screening in people living with diabetes in Australia: a cost effectiveness analysis. EClinicalMedicine 67, 102387 (2024).

Dai, T. & Abràmoff, M. D. Incorporating artificial intelligence into healthcare workflows: Models and insights. Tutorials in Operations Research: Advancing the Frontiers of OR/MS: From Methodologies to Applications 133–155 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1287/educ.2023.0257 (2023).

Spatharou et al. Transforming healthcare with AI: The impact on the workforce and organizations. (McKinsey & Company Executive Briefing, 2023).

Wu Kevin et al. Characterizing the Clinical Adoption of Medical AI Devices through U.S. Insurance Claims. NEJM AI 1, AIoa2300030 (2023).

Marks, B. E. et al. Baseline Quality Improvement Capacity of 33 Endocrinology Centers Participating in the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative. Clin. Diabetes 41, 35–44 (2022).

Abràmoff, M. D. et al. A reimbursement framework for artificial intelligence in healthcare. NPJ Digit Med. 5, 72 (2022).

Abramoff, M. D. et al. Scaling adoption of medical artificial intelligence: Reimbursement from value-based care and fee-for-service perspectives. NEJM-AI 1, (2024).

Keel, G., Savage, C., Rafiq, M. & Mazzocato, P. Time-driven activity-based costing in health care: A systematic review of the literature. Health Policy 121, 755–763 (2017).

Sox, H. C., Higgins, M. C., Owens, D. K. & Schmidler, G. S. Medical Decision Making 3rd edition. (John Wiley & Sons, 2024).

Dabelea, D. et al. Association of type 1 diabetes vs type 2 diabetes diagnosed during childhood and adolescence with complications during teenage years and young adulthood. JAMA 317, 825 (2017).

Porter, M. et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in children and adolescents at an Urban Tertiary Eye Care Center. Pediatr. Diabetes 21, 856–862 (2020).

Wang, S. Y., Andrews, C. A., Herman, W. H., Gardner, T. W. & Stein, J. D. Incidence and risk factors for developing diabetic retinopathy among youths with type 1 or type 2 diabetes throughout the United States. Ophthalmology 124, 424–430 (2017).

Bjornstad, P. et al. Long-term complications in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 2014–2016 (2021).

Lin, D. Y., Blumenkranz, M. S., Brothers, R. J. & Grosvenor, D. M. The sensitivity and specificity of single-field nonmydriatic monochromatic digital fundus photography with remote image interpretation for diabetic retinopathy screening: A comparison with ophthalmoscopy and standardized mydriatic color photography11internetadvance publication at ajo.com. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 134, 204–213 (2002).

Pugh, J. A. et al. Screening for diabetic retinopathy: The wide-angle retinal camera. Diabetes Care 16, 889–895 (1993).

Lim, J. I. et al. Artificial Intelligence Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy: Subgroup Comparison of the EyeArt System with Ophthalmologists’ Dilated Examinations. Ophthalmol. Sci. 3, 100228 (2023).

Abràmoff, M. D., Lavin, P. T., Birch, M., Shah, N. & Folk, J. C. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in Primary Care Offices. npj Digital Med. 1, 39 (2018).

Bhaskaranand, M. et al. The value of automated diabetic retinopathy screening with the EyeArt system: A study of more than 100,000 consecutive encounters from people with diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Therapeutics 21, 635–643 (2019).

AEye Health Inc. 2022. AEYE-DS Device. [510(K) Summary, Document Number: K221183]. Food and Drug Administration. URL: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf22/K221183.pdf.

Wolf, R. M. et al. The SEE study: Safety, efficacy, and equity of implementing autonomous artificial intelligence for diagnosing diabetic retinopathy in Youth. Diabetes Care 44, 781–787 (2021).

Wang, S. Y. et al. Ophthalmic screening patterns among youths with diabetes enrolled in a large US Managed Care Network. JAMA Ophthalmol. 135, 432 (2017).

Wolf, R. M. et al. Autonomous artificial intelligence increases screening and follow-up for diabetic retinopathy in youth: The Access Randomized Control Trial. Nat. Commun. 15, 421 (2024).

Crossland, L. et al. Diabetic retinopathy screening and monitoring of early stage disease in Australian general practice: Tackling preventable blindness within a chronic care model. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 1–7 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Diabetic retinopathy screening with automated retinal image analysis in a primary care setting improves adherence to Ophthalmic Care. Ophthalmol. Retin. 5, 71–77 (2021).

Reiter, K. L., Song, P. H. & Gapenski, L. C. Gapenski’s Healthcare Finance: An introduction to accounting and Financial Management. (Health Administration Press, 2021).

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; CY 2022 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Provider Enrollment Regulation Updates; and Provider and Supplier Prepayment and Post-Payment Medical Review Requirements. Federal Register vol. 86 64996–66031 (2021).

Minimum Wage. DOL https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/wages/minimumwage.

Registered Nurses. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291141.htm (2023).

Wells, J. E. Efficient office design for a successful practice. Fam. Pract. Manag. 14, 46–50 (2007).

Baltimore City Office Price per Sqft and Office Market Trends. https://www.commercialcafe.com/office-market-trends/us/md/baltimore-city/.

Pantley, S. & Hammer, C. Cost of an Initial Examination for Diabetic Retinopathy. (2020).

Hirth, R. A., Chernew, M. E., Miller, E., Fendrick, A. M. & Weissert, W. G. Willingness to pay for a quality-adjusted life year. Med. Decis. Mak. 20, 332–342 (2000).

Alabama Medicaid. https://medicaid.alabama.gov/alert_detail.aspx?ID=16254.

Acknowledgements

This clinical trial was supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01EY033233 to R.M.W. R.C. receives research support in part by an Unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. to the UW-Madison Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, and by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5K23EY030911-03. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. No support was received from Digital Diagnostics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: R.M.W., R.C., H.L., M.A., T.D., M.D.A. Data collection: R.M.W., R.C., H.L., M.A., T.D., M.D.A. Data analysis and interpretation: R.M.W., R.C., H.L., M.A., T.D., M.D.A. Drafting the article: R.M.W., R.C., H.L., M.A., T.D., M.D.A. Critical revision of the article: All. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.D.A. reports the following conflicts of interest: Investor, Director, Consultant, Digital Diagnostics Inc., Coralville, Iowa, USA; patents and patent applications assigned to the University of Iowa and Digital Diagnostics that are relevant to the subject matter of this manuscript; Chair Healthcare AI Coalition, Washington DC; member, American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) AI Committee; member, AI Workgroup Digital Medicine Payment Advisory Group (DMPAG); member, Collaborative Community for Ophthalmic Imaging (CCOI), Washington DC; Chair, Foundational Principles of AI CCOI Workgroup. R.M.W. reports receiving research support from Novo Nordisk, Lilly, and Sanofi outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, M., Dai, T., Channa, R. et al. Cost-effectiveness of AI for pediatric diabetic eye exams from a health system perspective. npj Digit. Med. 8, 3 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01382-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01382-4