Abstract

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally. Research indicates a disproportionate impact of glaucoma on racial and ethnic minorities. Existing deep learning models for glaucoma detection might not achieve equitable performance across diverse identity groups. We developed fair identify normalization (FIN) module to equalize the feature importance across different identity groups to improve model performance equity. The optical coherence tomography (OCT) measurements were used to categorize patients into glaucoma and non-glaucoma. The equity-scaled area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ES-AUC) was adopted to quantify model performance equity. With FIN for racial groups, the overall AUC and ES-AUC increased from 0.82 to 0.85 and 0.77 to 0.81, respectively, with the AUC for Blacks increasing from 0.77 to 0.82. With FIN for ethnic groups, the overall AUC and ES-AUC increased from 0.82 to 0.84 and 0.77 to 0.80, respectively, with the AUC for Hispanics increasing from 0.75 to 0.79.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucomatous optic neuropathy is the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally1,2,3 affecting 3.5% of the population between 40 and 80 years totaling 3 million patients in the US and 80 million patients worldwide1,4. However, most commonly, glaucoma patients are not aware of having the disease until the vision loss becomes severe enough to impair their daily activities, such as reading and driving due to the brain and fellow eye compensation5,6,7,8,9,10,11. It has been reported that 50% of people with glaucoma do not know they have the disease, and racial and ethnic minority groups are particularly affected due to a lack of access to ophthalmic care largely attributed to financial limitations12,13.

Increasing research indicates that glaucoma disproportionately impacts racial and ethnic minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged identity groups14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. We recently found that visual field (VF) loss in glaucoma patients at the first visit to an ophthalmology service is significantly worse in Blacks and Asians than in Whites and significantly worse in Hispanics than in non-Hispanics22. Noticeably, lower proficiency in English was also linked to a more pronounced VF loss in patients with glaucoma. Despite greater severity at the first visit, Black patients had lower VF test frequency compared to Whites. In a separate study, we found that compared with non-Hispanic Whites, Black individuals faced higher risks of developing early central and advanced VF loss23. Blacks and Hispanics are significantly more likely (4.4 and 2.5 times) to have undiagnosed and untreated glaucoma compared with non-Hispanic Whites12. Therefore, automated glaucoma screening with deep learning deployed at primary care and pharmacies would greatly benefit racial and ethnic minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged identity groups.

Though numerous deep learning studies have been conducted for automated glaucoma detection using retinal images (e.g., as illustrated in Fig. 1a)24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, it remains unclear if these deep learning models have equitable performance across different identity groups. In recent years, significant work in deep learning has been done to alleviate performance inequality in the models32,33,34. The performance inequality observed in deep learning models primarily stems from data inequality and data characteristic variability between different identity groups. Standard deep learning models without equity-improving design favor the majority group algorithmically and may not be able to represent the diverse data characteristic variability across different identity groups. For example, consistent with the US population composition35, there are fewer Black and Asian glaucoma patients present in ophthalmic care, which is data inequality14.

In this study, we introduce fair identity normalization (FIN) to promote equitable glaucoma screening. The fundamental premise of FIN rests on the notion that individuals within the same identity group exhibit a greater correlation compared to those from other groups. This correlation is cultivated by promoting distinct feature distributions across different identity groups during the deep learning model’s training phase. Our examination of FIN’s efficacy spanned across three deep learning frameworks: RETFound, EfficientNet and ResNet36,37,38. However, given that EfficientNet is more effective than ResNet and RETFound based on our experiments, we chose EfficientNet as the backbone model in this study. We aimed to diminish group disparities in glaucoma screening using retinal nerve fiber layer thickness (RNFLT) maps. In addition, a three-dimensional (3D) convolutional neural network (CNN)39, both standalone and in conjunction with FIN, was employed to predict glaucomatous status using 3D optical coherence tomography (OCT) B-scans. We compared FIN against other common methods, which incorporated several strategies: image augmentation to enhance the diversity of RNFLT maps, thus boosting model generalizability; oversampling to balance data representation across different groups; and a transfer learning technique where a deep learning model, initially trained on data from all patients, was fine-tuned for specific identity groups based on race, gender, and ethnicity. We adopted the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) to analyze overall screening accuracy and group-level accuracies. Furthermore, to account for the tradeoff between overall AUC and group disparity, we proposed a new metric called equity-scaled AUC (ES-AUC, similar for ES-AUPRC) to compare the model equity. Additionally, we used mean and max disparities to quantify the differences in screening accuracies across different identity groups.

Results

Dataset collection

In this study, we utilized a dataset comprising 7418 RNFLT maps obtained from 7418 patients who underwent tests at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear (MEE) glaucoma service from 2021 to 2023. Each of these two-dimensional (2D) RNFLT maps (Fig. 1b), with a dimension of 224 × 224, represents thickness values and was sourced from a spectral-domain OCT instrument (Cirrus, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, California). Only high-quality RNFLT maps with a signal strength of 6 or higher were considered. In addition, the dataset encompassed corresponding 3D OCT B-scans. Each of these 3D OCT B-scan volumes consists of 200 individual B-scans, with each B-scan measuring 200 × 200 in dimension. The participants’ age at the time of imaging ranged from 10 to 100 years (median: 61), and 57.8% were females. When examining ethnicity and race, 4.6% of the patients identified as Hispanic, while the racial distribution was 8.6% Asian, 14.9% Black, and 76.5% White (as shown in Table 1). It is important to note that race, gender, and ethnicity are distinct categories of identity that operate independently of one another. For example, an individual can identify as Female, Hispanic, and White. Our categorization is based on standard clinical questionnaire used at MEE, which is also widely used in many existing studies21,22. RNFLT and MD values show similar distributions across different identity groups (Supplementary Fig. 1). Notably, 46.7% of all 7418 patients were diagnosed with glaucoma.

In addition, we used a public dataset which is a glaucoma real-world appraisal progression ensemble (GRAPE) dataset40 to evaluate the proposed model. We used a total of 263 color fundus images available in GRAPE for predicting the glaucoma progression, which were collected from 263 eyes of 144 glaucoma patients between 2015 and 2022, with age ranging from 18 to 81 years (median: 41 years). Female and male patients comprise 48.7% and 51.3% of the population, respectively. The glaucoma progression was defined in three different criteria, with two based on point-wise linear regression (PLR) analysis and one based on mean deviation (MD) slope. For PLR, the baseline VF of one eye is defined as progressing if the number of test points with a significant negative regression slope (P value < 0.01) greater than or equal to two (PLR2) or three (PLR3). For the MD slope, an eye is considered to be undergoing progression when the slope of MD over the follow-up period shows a negative linear regression and the P value is less than 0.05. The distributions of non-progression and progression for the three types are as follows: (1) MD: 89.7% non-progression and 10.3% progression; (2) PLSR2: 84.8% non-progression and 15.2% progression; (3) PLSR3: 94.7% non-progression and 5.3% progression.

Glaucoma screening performance using RNFLT maps

For ResNet combined with FIN, the overall AUC and ES-AUC for the racial group increased from 0.805 to 0.82 and 0.757 to 0.77 (P value < 0.05). The corresponding AUCs improved by 0.02 (P value < 0.05) for Blacks, Asians, and Whites, respectively, although there were no improvements of mean and max disparities (Fig. 2a). Similarly, the overall AUCs for both gender and ethnic groups improved by 0.02 (P value < 0.001), while the improvement of ES-AUC was insignificant after integrating FIN with ResNet (Fig. 2b, c). However, the improvement of ES-AUC was insignificant after integrating FIN with ResNet for ethnic group (Fig. 2c). With the integration of FIN, RETFound enhanced the overall AUC and ES-AUC by 0.02 and 0.03, respectively, for race, 0.01 for both metrics on gender, and 0.01 and 0.04, respectively, on ethnicity (P value < 0.05, Fig. 2).

In comparison, after combining the FIN with EfficientNet, the overall AUC and ES-AUC for racial groups increased from 0.82 to 0.85 and 0.766 to 0.814 (P value < 0.001), respectively, with the AUC for Blacks increasing from 0.77 to 0.82 (P value < 0.001) (Fig. 2a). The mean and max disparities significantly decreased from 0.04 to 0.02 and 0.09 to 0.04 (P value < 0.001) (Fig. 2a), respectively. With FIN for gender groups, the overall AUC and ES-AUC increased from 0.82 to 0.84 and 0.80 to 0.82 (P value < 0.001), respectively, with an AUC improvement of 0.02 for both females and males (P value < 0.001) (Fig. 2b). With FIN for ethnic groups, the overall AUC and ES-AUC increased from 0.82 to 0.84 and 0.76 to 0.79 (P value < 0.001), respectively, with the AUC for Hispanics increasing from 0.74 to 0.79 (P value < 0.001) (Fig. 2c). The mean and max disparities decreased by 0.02 and 0.03 (P value < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 2c). If evaluating using AUPRC, improvements were observed across both race and gender categories, with increases of 0.03 in overall AUC and 0.02 in ES-AUPRC for race, and similar increases of 0.03 and 0.02, respectively, for gender (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The feature distributions learned by the deep learning model from RNFLT maps are shown in Fig. 3. After incorporating FIN with EfficientNet, Blacks were found to be more distant from Asians in the feature space, while both Blacks and Asians exhibited greater similarity with Whites (Fig. 3a, d). After integrating FIN, the features of female and male groups had become more similar (Fig. 3b, e). Conversely, the features of non-Hispanic and Hispanic groups had grown more dissimilar after the integration of FIN (Fig. 3c, f).

a Feature distribution in racial groups with EfficientNet. b Feature distribution in gender groups with EfficientNet. c Feature distribution in ethnic groups with EfficientNet. d Feature distribution in racial groups with EfficientNet + FIN. e Feature distribution in gender groups with EfficientNet + FIN. f Feature distribution in ethnic groups with EfficientNet + FIN.

While comparing the image augmentation, oversampling, and transfer learning methods, FIN generally achieved better AUC (or AUPRC) and ES-AUC (or ES-AUPRC) performances for different identity groups than baseline methods. For the attributes of race, gender, and ethnicity, augmentation-based method 2 (EfficientNet + augmentation 2) led to a 0.02 increase in the overall AUC (Fig. 4), with specific improvements of 0.07 for Asians and 0.02 for Females (P value < 0.05). In addition, the ES-AUC for gender increased by 0.02, though there were no significant enhancements for race and ethnicity (Fig. 4b). In contrast, augmentation-based method 1 (EfficientNet + augmentation 1) could not improve the AUC and ES-AUC performances of the baseline EfficientNet model (Fig. 4). With FIN, EfficientNet consistently outperformed the image augmentation-based methods in both overall (equality-scaled) AUC and AUPRC performances. However, compared to FIN, augmentation 2 exhibited a smaller mean disparity with respect to gender and both smaller mean and max disparities concerning ethnicity. For racial groups, the overall AUC and ES-AUC of FIN were 0.03 and 0.08 higher than the oversampling (P value < 0.001), and 0.03 and 0.07 higher than the transfer learning (P value < 0.001) (Fig. 4a). The mean and max disparities of FIN had a significant decrease of 0.03 and 0.08 compared to the oversampling approach (P value < 0.001), and 0.03 and 0.07 compared to the transfer learning (P value < 0.001). Similarly, for gender groups, the overall AUC and ES-AUC of FIN both improved by 0.02 compared with oversampling (P value < 0.05), where the improvements were 0.03 and 0.04 compared to the transfer learning (P value < 0.001) (Fig. 4b). The mean and max disparities of FIN significantly decreased by 0.03 and 0.04 compared to the transfer learning method (P value < 0.001), while no significant improvements were observed compared to the oversampling method. Lastly for ethnic groups, the overall AUC of FIN significantly improved by about 0.03 over the sampling and transfer learning methods (P value < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 4c). The ES-AUC of FIN increased by 0.05 over the oversampling method but there was no improvement over the transfer learning method (Fig. 4c). The corresponding mean and max disparities of FIN decreased by 0.07 and 0.1 compared to the oversampling method, and 0.06 and 0.08 compared to the transfer learning method, respectively (Fig. 4c).

Glaucoma screening performance using 3D OCT B-Scans

Using 3D OCT B-scans with FIN for glaucoma screening, the overall AUC and ES-AUC for racial groups improved from 0.81 to 0.85 and 0.76 to 0.80 (P value < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 5a), where the AUCs for Asians and Blacks both improved by 0.02. Similar improvements (0.03 and 0.04) for the overall and equity-scaled performances were observed based on the AUPRC (Supplementary Fig. 4a). With FIN for gender groups, the overall AUC and ES-AUC had an improvement of 0.03 and 0.02, respectively (Fig. 5b), while improved by 0.03 and 0.01 (P value < 0.05) for AUPRC and ES-AUPRC, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4b). With FIN for ethnic group, the overall AUC and ES-AUC both improved by 0.03 (P value < 0.001), respectively, with the AUCs both improved by 0.03 for non-Hispanic and Hispanic groups (P value < 0.001) (Fig. 5c). Compared with the oversampling method, the overall AUC and ES-AUC of FIN had an improvement of 0.03 and 0.05 (P value < 0.001) on race attribute, and 0.04 and 0.04 (P value < 0.001) on gender attribute (Fig. 5b). While for ethnicity attribute, the overall AUC improved 0.03 (P value < 0.001), with the ES-AUC had no improvement (Fig. 5c). In contrast, the overall AUC and ES-AUC of FIN generally had no improvement over the transfer learning method (Fig. 5).

Glaucoma progression prediction performance using color fundus

We tested the effectiveness of FIN for progression prediction on the GRAPE dataset. It should be noted that some evaluations were unavailable due to the highly imbalanced distribution between non-progression and progression cases (e.g., only a few dozen samples are in the non-progression category). This imbalance resulted in some groups lacking non-progression cases altogether. Using color fundus images with FIN to predict glaucoma progression, ResNet and EfficientNet showed no improvement in overall AUC and ES-AUC performances for MD and PLR2-based progressions (Supplementary Table 1). However, for PLR3-based progression, the overall AUCs for ResNet and EfficientNet improved by 0.02 and 0.01, respectively. After integrating with FIN, the overall AUCs of REFFound improved from 0.633 to 0.671 (P value < 0.001) on MD-based progression and improved from 0.689 to 0.756 on PLR3-based progression. For PLR2-based progression, integrating FIN into the RETFound model resulted in an increase in the overall AUC and ES-AUC from 0.70 to 0.73 (p value < 0.001) and from 0.64 to 0.69 (P value < 0.001), respectively. Similar for AUPRC as the evaluation metric, the overall AUPRC and ES-AUPRC of RETFound both significantly improved after integrating with FIN (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

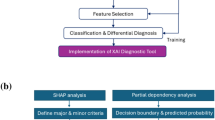

This paper demonstrates that deep learning models for glaucoma screening may perform quite differently across demographic groups, and it is possible to reduce the performance disparity gap between different demographic groups by model innovation. We proposed the fair identity normalization (FIN) module which has the potential to reduce group disparities with no overall performance deterioration or even overall performance improvement. We introduced a deep learning model that combines EfficientNet with FIN for equitable glaucoma screening utilizing RNFLT maps and 3D OCT B-scans (Fig. 6). In comparison to the standalone EfficientNet, the EfficientNet combined with FIN model enhanced the overall AUC and ES-AUC by 0.02 and 0.05 for racial groups, 0.02 and 0.02 for gender groups, and 0.02 and 0.03 for ethnic groups (Fig. 2). We compared EfficientNet with other deep learning models ResNet and RETFound with and without the enhancement of FIN (Fig. 2), which demonstrates that FIN is effective in promoting equitable glaucoma screening.

First, the model takes retinal nerve fiber layer thickness maps or three-dimensional optical coherence tomography B-scans as the input. Then, the model-learned features undergo normalization via FIN, where patients within the same identity groups are aligned to a consistent distribution. Finally, the normalized features, tailored to specific identity groups, are employed to predict the binary glaucomatous status. FIN fair identity normalization.

Previous studies have consistently highlighted that glaucoma has a disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minorities, as well as socioeconomically marginalized groups. For instance, upon their initial visit to an ophthalmology service, Black and Asian glaucoma patients typically display more severe visual field (VF) loss than their White counterparts. Similarly, the severity is worse in Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanics. Notably, Blacks and Hispanics are ~4.4 and 2.5 times more likely, respectively, to have undetected and untreated glaucoma than non-Hispanic Whites. While deep learning models have gained traction for automated glaucoma detection, they often overlook the crucial aspect of ensuring equal performance across diverse identity groups. In addition, existing study reported that population characteristics can affect model performance, which is consistent with our findings that different demographic groups may have model performance disparities41. Our proposed FIN effectively addresses these disparities across different identity groups. The incorporation of FIN with ResNet and RETFound, as well as its comparison to image augmentation, oversampling and transfer learning techniques based on the equity-scaled metrics, further underscores the efficacy of FIN in promoting equitable glaucoma screening. Although FIN did not consistently yield the lowest mean and max disparities compared to other methods. In this study, we regard ES-AUC (or ES-AUPRC) as a more comprehensive measure of equity than mean and max disparities. This is because ES-AUC represents both model equity and overall performance, whereas mean and max disparities focus primarily on model equity across different groups. Feature distribution visualizations indicate that FIN increased the distinction of learned features between Asians and Blacks compared to Whites (Fig. 3a, d). This suggests that the overlap of features for Asians and Blacks might have led to higher false positive rates in glaucoma screening for these groups. FIN’s enhancement of feature differentiation has sharpened the distinction, improving the AUC for Blacks by 0.04 (Fig. 2a). In addition, FIN has narrowed the feature gap between gender groups (Fig. 3b, e) and widened the feature variance between non-Hispanic and Hispanic groups. These changes demonstrate FIN’s role in refining feature distributions to optimize glaucoma screening outcomes and fairness.

AUC and ES-AUC were mainly used to evaluate model performance and fairness. It is interesting to note that the improvements of overall AUC and ES-AUC are not always aligned. For example, using RNFLT maps on the ethnic group, the overall AUC of ResNet after integrating with FIN had an improvement of 0.02 (P value < 0.001), while the corresponding ES-AUC had no significant improvement. This indicates while the overall AUC increased, the group disparity also increased, with the ES-AUC having limited improvement. Another interesting observation is that FIN typically aids in diminishing the mean and max disparities for race and gender, its integrations with ResNet and RETFound on RNFLT maps did not show any remarkable improvement in equity between the non-Hispanic and Hispanic groups. This observation can be linked to a couple of key factors. First, the efficiency of FIN can vary based on the deep learning model it is paired with. Different models have unique capabilities in extracting beneficial features from the RNFLT map that can enhance equity. Second, the metrics we employed to measure the equity of glaucoma screening across various identity groups might not capture the full picture. To obtain a thorough understanding, it would be beneficial to consider other fairness metrics in future research, such as demographic parity, equalized odds, and equal opportunity. Interestingly, when combined with EfficientNet, augmentation-based method 1 resulted in decreased performance (Fig. 4). This decline may be attributed to the random cropping operation, which was unique to Augmentation Method 1. This process may have altered the distribution of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and resulted in the loss of critical information at pathological locations, thereby impacting the accuracy of glaucoma detection. While FIN generally outperformed the image augmentation, oversampling and transfer learning methods when using both RNFLT maps and OCT B-Scans for detecting glaucoma, its performance could be less effective for certain specific identity groups. For instance, FIN did not perform as well (e.g., in terms of AUC) when compared with the oversampling method for Asians, and it was less effective than the transfer learning method for both Asian and Hispanic groups. (Fig. 4a, c). This is because different identity groups may have their intrinsic anatomical characteristics thus responded differently to oversampling and transfer learning strategies. However, as an independent fairness learning strategy, FIN can improve the baseline EfficientNet model regarding both overall performance and group performance disparities. FIN can also be combined with image augmentation, oversampling and transfer learning methods to potentially enhance model performance and group performance equity.

Our research has several limitations. First, even though we have achieved equitable glaucoma screening with comprehensive evaluations encompassing all severity stages, we have not examined the performance across different stages like mild versus severe glaucoma. Different identity groups could experience varied screening accuracies based on the stage of their condition. However, we observed that different identity groups demonstrate similar RNFLT and MD value distributions (Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, for the evaluation data used in this study, there is limited glaucomatous severity bias across different identity groups. Second, while the patient distribution across identity groups in our study mirrors real-world disparities (for instance, 8.6%, 14.9%, and 76.5% were identified as Asian, Black, and White respectively), we have not assessed the equity of glaucoma screening in scenarios where sample sizes across these groups are balanced. Third, our evaluation of FIN concentrated on its integration with EfficientNet, ResNet and RETFound. We have not explored its efficacy when paired with other prevalent deep learning models like vision transformers or the VGG network, even though FIN has the versatility to be paired with various learning frameworks. Fourth, our use of ES-AUC or ES-AUPRC, mean and max disparities to measure the fairness of glaucoma prediction among identity groups is limited. There exists a range of other fairness metrics, such as demographic parity, equalized odds, and equal opportunity, which we have not considered. Last, prior studies reported the RNFLT may contain artifacts42,43. Although we have constrained the signal strength to control the quality of OCT B-scans, it is interesting to study the impact of RNFLT artifacts on model fairness across different identity groups.

In summary, we introduced FIN that can seamlessly integrate with many mainstream deep learning frameworks for equitable glaucoma screening. FIN works by normalizing features derived from RNFLT maps or 3D OCT B-scans in alignment with patients’ identity groups. Our evaluations on prominent deep learning architectures, EfficientNet, RETFound and ResNet, underscore FIN’s capability to not only boost glaucoma screening accuracy but also curtail disparities across race, gender, and ethnicity, particularly in conjunction with EfficientNet. When compared against other strategies, FIN generally outperforms image augmentation, oversampling and transfer learning that aim for equity in glaucoma screening. With its potential for real-world clinical applications, our deep learning model incorporating FIN stands as a promising tool to promote equitable glaucoma screening outcomes across diverse identity groups.

Methods

Data specification

The institutional review boards (IRB) of MEE approved the creation of the database in this retrospective study. This study complied with the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. In light of the study’s retrospective design, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

For the MEE dataset for glaucoma detection, the glaucomatous status was determined by matching the reliable visual field (VF) test with OCT. In this study, we exclusively utilized reliable 24-2 VFs, characterized by fixation loss ≤ 33%, a false positive rate ≤ 20%, and a false negative rate ≤ 20%. These reliability criteria align with those employed in our previous research44,45. Glaucomatous status was defined based on the VF mean deviation (MD): an MD of less than -3 dB with abnormal glaucoma hemifield test and pattern standard deviation results was classified as glaucoma, while an MD greater than or equal to −1 dB with normal glaucoma hemifield test and pattern standard deviation results was identified as non-glaucoma. For the GRAPE dataset for progression prediction, the glaucoma progression was defined in three different criteria in the original work40, with two based on point-wise linear regression analysis and one based on mean deviation slope.

Glaucoma screening model with fair identity normalization

We designed a deep learning model based on the EfficientNet36, enhanced with fair identity normalization (FIN), to achieve equitable glaucoma screening (Fig. 6). The proposed FIN method enhances the model’s ability to handle demographic-specific biases by normalizing feature distributions on a subgroup basis. Initially, the model takes RNFLT maps or 3D OCT B-scans as the input, extracting pertinent and discriminative features through the EfficientNet architecture. Subsequently, these features undergo normalization via FIN, considering the group identity associated with the input image. We hypothesized that samples sharing the same group identity are inherently correlated with one another. As a result of this normalization, learned features from patients with same identity groups, such as racial and gender groups, are aligned to a consistent Gaussian distribution with learnable mean and standard deviation. This process reduces the model’s sensitivity to demographic attributes and equalizes the feature importance among different identity groups in deep learning, thereby achieving model equity across various identity groups. Finally, the normalized features, tailored to specific identity groups, are employed to predict the binary glaucomatous status. The flexibility of FIN’s conceptual framework allows it to be adapted to various medical imaging tasks beyond glaucoma detection. As artificial intelligence (AI) approaches continue to expand in the healthcare domain, techniques like FIN are crucial for developing fair and ethical diagnostic tools. This not only improves patient outcomes but also promotes trust in AI systems used in high-stakes medical environments.

The model training followed a supervised manner. The dataset underwent a patient-level random split: 70% was dedicated to model training and the remaining 30% was used for evaluating both glaucoma screening precision and group performance equity. We assessed FIN’s efficacy for equitable glaucoma screening across three distinct identity parameters: race, gender and ethnicity. This study examined three racial groups (Asian, Black, White), two gender groups (female and male), and two ethnic groups (non-Hispanic and Hispanic). The model-learned features for different identity groups can be projected into a two-dimensional feature space based on the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) for the purpose of visualization46.

Comparative methods

We selected three widely used deep learning methods for comparing glaucoma detection performance and performance equity across different identity groups. They are ResNet36, RETFound38, and EfficientNet36 which have been widely used for processing medical images. ResNet and EfficientNet were initialized with pretrained weights on ImageNet containing over 1.28 million labeled natural images. RETFound used vision transformer47 as the backbone and was trained on 1.6 million unlabeled retinal images. We compared the performance of these models with and without incorporating the FIN module following a consistent training and evaluation pipelines. For the EfficientNet model, we developed four different variant methods by introducing two types of image augmentation (Augmentation 1 and Augmentation 2), data oversampling and transfer learning strategies. Augmentation 1 is a frequently used image augmentation method that begins with randomly resizing an image to dimensions of 200 × 200, followed by a random horizontal flip (with a 50% probability), and concludes with normalization. Augmentation 2 involves applying an elastic transformation to all images, which changes the morphology of objects within the images, producing an effect akin to looking through water. This technique uses specific parameters, alpha (50.0) and sigma (5.0), to dictate the intensity and smoothness of the displacements, respectively. It creates displacement vectors for every pixel in an image based on random offsets. Oversampling addresses data imbalance by randomly duplicating samples to ensure that each identity group, such as different racial groups (Asian, Black, and White), has an equal number of samples. In the transfer learning-based approach, a global model was initially trained using samples from various identity groups. Subsequently, this global model was tailored to each specific identity group through fine-tuning with the available samples within that particular group.

Performance metrics and statistical analysis

The AUC and AUPRC served as our metrics for quantifying both overall glaucoma detection accuracy and group-specific accuracy, categorized by race, gender, and ethnicity. Specifically, we concentrated on the racial groups of Asians, Blacks, and Whites; the gender groups of Females and Males; and the ethnic groups of Non-Hispanics and Hispanics. To quantify AUC disparities in glaucoma screening across different identity groups of a specific demographic attribute, we proposed to use a new metric called equity-scaled AUC (ES-AUC) to compare the model performance equity. The ES-AUC is defined as the overall AUC divided by one plus the sum of the absolute differences between the overall AUC and each group’s AUC, formulated as \({{\boldsymbol{AUC}}}_{{\boldsymbol{ES}}}={{\boldsymbol{AUC}}}_{{\boldsymbol{overall}}}/({\boldsymbol{1}}{\boldsymbol{+}}{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}|{{\boldsymbol{AUC}}}_{{\boldsymbol{overall}}}{\boldsymbol{-}}{{\boldsymbol{AUC}}}_{{\boldsymbol{group}}}|)\). A maximized ES-AUC requires that group AUCs are close to the overall AUC, thus achieving minimized group AUC disparities. ES-AUPRC was calculated similarly to ES-AUC, where the overall AUPRC is divided by one plus the total of the absolute differences between the overall AUPRC and the AUPRC for each group. Additionally, we computed both mean disparity and max disparity as complementary measures to demonstrate the model’s equity. Mean disparity was calculated as the ratio of the standard deviation of individual group AUCs to the adjusted overall AUC, obtained by subtracting 0.5 from the overall AUC. Similarly, max disparity was determined by the ratio of the difference between the highest and lowest individual group AUCs to this adjusted overall AUC. Lower max and mean disparities signify better model equity. In addition to the primary metrics reported above, model performances using other standard metrics like accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, recall, and F1 scores are detailed in the supplementary material.

We reported AUC and AUPRC with 95% confidence intervals. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant result. Statistical analyses were performed in Python 3.8 (available at http://www.python.org) on a Linux system.

Data availability

The GRAPE is available at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-023-02424-4.

Code availability

The codes for the proposed model are open source and available at https://github.com/Harvard-Ophthalmology-AI-Lab/FairNormalization.

References

Tham, Y.-C. et al. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 121, 2081–2090 (2014).

Quigley, H. A. & Broman, A. T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90, 262–267 (2006).

Sun, Y. et al. Time trends, associations and prevalence of blindness and vision loss due to glaucoma: an analysis of observational data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ Open 12, e053805 (2022).

Stein, J. D., Khawaja, A. P. & Weizer, J. S. Glaucoma in adults—screening, diagnosis, and management: a review. JAMA 325, 164–174 (2021).

Artes, P. H. & Chauhan, B. C. Longitudinal changes in the visual field and optic disc in glaucoma. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 24, 333–354 (2005).

Crabb, D. P., Smith, N. D., Glen, F. C., Burton, R. & Garway-Heath, D. F. How does glaucoma look?: patient perception of visual field loss. Ophthalmology 120, 1120–1126 (2013).

Kellman, P. J. & Shipley, T. F. A theory of visual interpolation in object perception. Cogn. Psychol. 23, 141–221 (1991).

Morgan, M. J. & Watt, R. J. Mechanisms of interpolation in human spatial vision. Nature 299, 553–555 (1982).

Nelson-Quigg, J. M., Cello, K. & Johnson, C. A. Predicting binocular visual field sensitivity from monocular visual field results. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 2212–2221 (2000).

Hu, S., Smith, N. D., Saunders, L. J. & Crabb, D. P. Patterns of binocular visual field loss derived from large-scale patient data from glaucoma clinics. Ophthalmology 122, 2399–2406 (2015).

Teng, B. et al. Inter-eye association of visual field defects in glaucoma and its clinical utility. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 22 (2020).

Shaikh, Y., Yu, F. & Coleman, A. L. Burden of undetected and untreated glaucoma in the United States. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 158, 1121–1129 (2014).

Chua, J. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and visual features of undiagnosed glaucoma: the Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Diseases Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 133, 938–946 (2015).

Rudnicka, A. R., Mt-Isa, S., Owen, C. G., Cook, D. G. & Ashby, D. Variations in primary open-angle glaucoma prevalence by age, gender, and race: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 4254–4261 (2006).

Friedman, D. S., Jampel, H. D., Munoz, B. & West, S. K. The prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among blacks and whites 73 years and older: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Glaucoma Study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 124, 1625–1630 (2006).

Hoevenaars, J. G. M. M., Schouten, J. S. A. G., Van Den Borne, B., Beckers, H. J. M. & Webers, C. A. B. Socioeconomic differences in glaucoma patients’ knowledge, need for information and expectations of treatments. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 84, 84–91 (2006).

Shweikh, Y. et al. Measures of socioeconomic status and self-reported glaucoma in the UK Biobank cohort. Eye 29, 1360–1367 (2015).

Sukumar, S., Spencer, F., Fenerty, C., Harper, R. & Henson, D. The influence of socioeconomic and clinical factors upon the presenting visual field status of patients with glaucoma. Eye 23, 1038–1044 (2009).

Musa, I., Bansal, S. & Kaleem, M. A. Barriers to care in the treatment of glaucoma: socioeconomic elements that impact the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes in glaucoma patients. Curr. Ophthalmol. Rep. 10, 85–90 (2022).

Soh, Z. et al. The global extent of undetected glaucoma in adults. Ophthalmology 128, 1393–1404 (2021).

Halawa, O. A. et al. Racial and socioeconomic differences in eye care utilization among medicare beneficiaries with glaucoma. Ophthalmology 129, 397–405 (2022).

Halawa, O. A. et al. Race and ethnicity differences in disease severity and visual field progression among glaucoma patients. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 242, 69–76 (2022).

Kang, Jae H. et al. Cohort study of race/ethnicity and incident primary open-angle glaucoma characterized by autonomously determined visual field loss patterns. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 11, 1–11 (2022).

Asaoka, R. et al. Using deep learning and transfer learning to accurately diagnose early-onset glaucoma from macular optical coherence tomography images. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 198, 136–145 (2019).

Ran, A. R. et al. Detection of glaucomatous optic neuropathy with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: a retrospective training and validation deep-learning analysis. Lancet Digit. Health 1, e172–e182 (2019).

Medeiros, F. A., Jammal, A. A. & Mariottoni, E. B. Detection of progressive glaucomatous optic nerve damage on fundus photographs with deep learning. Ophthalmol. 128, 383–392 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Automatic feature learning for glaucoma detection based on deep learning. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 669–677 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Li, Z. et al. Efficacy of a deep learning system for detecting glaucomatous optic neuropathy based on color fundus photographs. Ophthalmology 125, 1199–1206 (2018).

Bojikian, K. D., Lee, C. S. & Lee, A. Y. Finding glaucoma in color fundus photographs using deep learning. JAMA Ophthalmol. 137, 1361–1362 (2019).

Kihara, Y. et al. Policy-driven, multimodal deep learning for predicting visual fields from the optic disc and OCT imaging. Ophthalmology 129, 781–791 (2022).

Christopher, M. et al. Deep learning approaches predict glaucomatous visual field damage from OCT optic nerve head En face images and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness maps. Ophthalmology 127, 346–356 (2020).

Quadrianto, N., Sharmanska, V. & Thomas, O. Discovering fair representations in the data domain. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 8227–8236 (IEEE, 2019).

Xu, H., Liu, X., Li, Y., Jain, A. & Tang, J. To be robust or to be fair: Towards fairness in adversarial training. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 11492–11501 (PMLR, 2021).

Yang, J., Soltan, A. A. S., Eyre, D. W., Yang, Y. & Clifton, D. A. An adversarial training framework for mitigating algorithmic biases in clinical machine learning. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 55 (2023).

Colby, S. L. & Ortman, J. M. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Population Estimates and Projections. Current Population Reports. P25-1143. (US Census Bureau, 2015).

Tan, M., & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International conference on machine learning. 6105-6114 (PMLR, 2019).

He, K., X. Zhang, S. Ren & J. Sun. Deep residual learning for image recognition. in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778 (IEEE, 2016).

Zhou, Y. et al. A foundation model for generalizable disease detection from retinal images. Nature 622, 156–163 (2023).

Ji, S., Xu, W., Yang, M. & Yu, K. 3D convolutional neural networks for human action recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35, 221–231 (2013).

Huang, X. et al. GRAPE: a multi-modal dataset of longitudinal follow-up visual field and fundus images for glaucoma management. Sci. Data 10, 520 (2023).

Christopher, M. et al. Effects of study population, labeling and training on glaucoma detection using deep learning algorithms. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 27 (2020).

Shi, Min. et al. Artifact-tolerant clustering-guided contrastive embedding learning for ophthalmic images in glaucoma. IEEE J. Biomed. and Health Informatics. 27, 4329–4340 (2023).

Min, S. et al. Artifact correction in retinal nerve fiber layer thickness maps using deep learning and its clinical utility in glaucoma. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 12, 12 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Characterization of central visual field loss in end-stage glaucoma by unsupervised artificial intelligence. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138, 190 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. An artificial intelligence approach to assess spatial patterns of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness maps in glaucoma. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 41 (2020).

McInnes, L., Healy, J., Saul, N. & Großberger, L. UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 861 (2018).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16×16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations. (ICLR, 2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R00 EY028631, NIH R21 EY035298, Research To Prevent Blindness International Research Collaborators Award, and Alcon Young Investigator Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W., M.S., and Y.L. conceived the study. M.S., Y.L., and M.W. developed the AI model. M.S., Y.L., M.E., Y.T., and S.K. collected the data. M.S., Y.L., M.E., Y.T., and S.K. performed data processing, experiment, and analysis. M.W., L.Q.S., N.Z., M.V.B., D.S.F., and L.R.P. contributed materials and clinical expertise. M.W. supervised the work. All authors wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, M., Luo, Y., Tian, Y. et al. Equitable artificial intelligence for glaucoma screening with fair identity normalization. npj Digit. Med. 8, 46 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01432-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01432-5

This article is cited by

-

Addressing Gender Disparities in Automatic Disease Detection: A Broad-Spectrum Analysis of Machine Learning Across Diverse Disease Types

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)