Abstract

Surgical planning can be highly complicated and personalized, where a surgeon needs to balance multiple decisional dimensions including surgical effectiveness, risk, cost, and patient’s conditions and preferences. Turning to artificial intelligence is a great appeal. This study filled in this gap with Multi-Dimensional Recommendation (MUDI), an interpretable data-driven intelligent system that supported personalized surgical recommendations on both the patient’s and the surgeon’s side with joint consideration of multiple decisional dimensions. Applied to Pelvic Organ Prolapse, a common female disease with significant impacts on life quality, MUDI stood out from a crowd of competing methods and achieved excellent performance that was comparable to top urogynecologists, with a transparent process that made communications between surgeons and patients easier. Users showed a willingness to accept the recommendations and achieved higher accuracy with the aid of MUDI. Such a success indicated that MUDI had the potential to solve similar challenges in other situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a crucial clinical decision-making issue, treatment selection is an essential component of clinical practice1. For diseases with explicit guidelines and recognized optimal treatment, determining a specific therapy is typically standardized and, therefore, uncomplicated. Nevertheless, for diseases lacking a recognized optimum treatment, the selection of treatment can become highly personalized and challenging. For instance, deciding on a procedure commonly involves considerations of its effectiveness, safety, and cost2,3,4. Though, it is often the case that the potentially most effective procedure is linked with increased expenses or safety concerns, so we would have to compromise for a comparatively suitable one for a particular patient by carefully evaluating his or her physical, mental, and financial circumstances, weighing multiple decision dimensions while also considering the preferences of the patient and surgeon. This type of surgical decision is highly personalized, comprehensive, and reliant on expert experience. However, it can be challenging to directly describe or even quantify this experience to reveal subtle tendencies and trade-offs, and sometimes even experts could hardly reach a consensus. This situation highlights the appeal of developing an intelligent data-driven approach to treatment recommendations.

Efforts have been made in the literature to find a solution. Initial attempts focused on rule-based expert systems that made decisions according to pre-defined deterministic rules set by experts5. Though this strategy has successfully recommended treatments for prostate cancer6, breast cancer7, hemophilia8, beta-thalassemia9, and so on, it lacks the flexibility for personalized medicine and is costly to keep up with the latest medical evidence5. Further efforts turned to the use of data-driven artificial intelligence based on statistical rules learned from extensive clinical data through diverse machine learning methods such as clustering analysis, logistic regression, decision tree, and tabular Q‐learning. Treatment optimization and recommendation along this research line have proven to be successful in ICU10, diabetes11, atrial fibrillation12, postmenopausal osteoporosis13, basal cell carcinoma14, breast cancer15, cardiovascular disease16, ovarian cancer17, and led to a well-known commercialized product, Watson for Oncology designed by International Business Machine which was able to offer dependable treatment recommendations for different types of cancer, e.g., breast cancer18 and lung cancer19. More recently, taking advantage of the rapid development of deep learning and reinforcement learning, more data-driven clinical applications have emerged as powerful tools in medical informatics20,21, drug development22, medical image analysis23,24,25,26, disease diagnosis21,27, prognosis prediction28,29,30, chronic disease management31 as well as treatment recommendation30,32,33,34. A major limitation of these deep-learning-based methods, however, is that they are often doubted for lack of transparency and interpretability.

We observed that none of the extant studies on treatment recommendation fully considered multiple decision-making dimensions concurrently, nor could make an intelligent treatment recommendation that is personalized for both the patient and the decision maker in an interpretable way. In this study, we filled in this gap with Multi-Dimensional Recommendation (MUDI), an interpretable data-driven intelligent system that facilitates bilaterally individualized procedure recommendation with joint consideration of multiple decision-making dimensions under the general framework of Multicriteria Decision Making (MCDM), which considers different qualitative and quantitative criteria that need to be fixed to find the best solution35,36,37. Compared to regular machine learning approaches that recommend treatments based on the patient’s raw features directly, MUDI enjoys the following advantages. First, it outlines a comprehensive framework for intelligible and rational compromise across all dimensions of decision-making. Second, it is capable of providing a quantitative representation of a surgeon or medical center’s decision-making philosophy with the backing of corresponding clinical data. Third, it is personalized for both the patient’s side and the surgeon’s side with straightforward interpretation that perfectly aligns with the thought process of surgeons in practice. Last, it utilizes explicit and implicit medical knowledge elegantly to provide probabilistic recommendations that could appropriately reflect the uncertainty in treatment selection for a complex disease. On the other hand, compared to conventional expert-driven methods for MCDM that balance conflicting decision-making dimensions based on subjective opinions of human experts via the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) or the Multi-Attribute Utility (MAU), MUDI is superior in objectivity, transparency, and efficient implementation due to its data-driven nature.

To verify the effectiveness of MUDI, we employed it in Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP), a common female disease related to the descent of the female pelvic organs into or through the vagina, which has a profoundly negative impact on the quality of life of the patients38. Lacking a straightforward guideline to select dozens of available procedures associated with heterogeneous treatment effects, impact on sexual function, risk of complications, operation complexity, and medical cost38,39,40,41(refer to Supplementary Materials for more details), surgery selection for POP patients is very challenging and highly reliant on expert experience. Worse still, professional urogynecologists are in great shortage in most countries42, including China. Developing a dependable AI tool to attain high-quality personalized surgical recommendations for patients with POP holds substantial medical significance. The ample decision-making components in POP render it an ideal specialist disease for motivating and validating the suggested method. A carefully designed simulation experiment involving over 1,000 POP patients at multiple medical centers in China has validated MUDI’s remarkably precise performance in recommending surgical options that closely align with top Chinese urogynecologists. To the best of our knowledge, none of the current knowledge-based or data-driven therapy recommendation systems for POP-related diseases43,44,45,46,47,48 could equal MUDI’s accuracy, flexibility, and interpretability. Such success on POP reveals the potential of MUDI as a general tool for decision-making for other diseases or situations facing a similar dilemma.

Results

Clinical problem and data preparation

Formally, let \({\mathcal{S}}=\{{s}_{1},\cdots ,{s}_{K}\}\) be the action space composed of \(K\) possible surgeries for the disease of interest, which is POP in this study. For a particular patient \(i\) whose surgery plan is under consideration, let \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i}\) be her feature vector that carries on all necessary pre-treatment covariates encoding her physical, psychological, and economic conditions. Our goal is to establish a quantitative model for recommending elements in \({\mathcal{S}}\) for the best benefit of patients. We hope that the established recommendation model can be well aligned with the thought process of surgeons in practice (i.e., interpretable), and can sufficiently reflect the preferences of patients and surgeons (i.e., personalized).

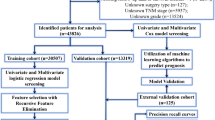

To support this study, we collected all patients who had POP procedures in Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH or \({H}_{1}\)) between January 2015 and August 2022 as the primary dataset to support this study. After a data quality control procedure, 242 patients were excluded due to missing data or receiving other surgical procedures beyond the 6 surgical procedures of our interest, leaving 997 qualified patients. Hereinafter, we referred to this single-center dataset with 997 qualified patients as \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s}\). Five-fold cross-validation was conducted for model training and validating: we split \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s}\) into a training dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,t}\) for model training with 799 patients who received surgeries between January 2015 and December 2020, and a testing dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,v}\) for method validation with 198 patients who received surgeries between January 2021 and August 2022.

To overcome the potential limitations of the internal validation based on \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s},\) we also collected an additional multi-center dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{m}\) for external validation, which contained 212 POP patients who received surgeries between September 2021 and September 2022 in 3 other hospitals, including Peking University First Hospital (PUFH or \({H}_{2}\)), Peking University People’s Hospital (PHPH or \({H}_{3}\)), and the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (TAHGMU or \({H}_{4}\)). Based on this multi-center dataset, we created a synthetic dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{m,v}\) containing 100 patients selected from \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,v}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{m}\) to compare MUDI with human surgeons. Table 1 summarizes the basic information of these datasets.

For each patient \(i\) in these datasets, 3 types of variables were recorded to form the following medical record for her:

where \({\boldsymbol{X}}_{i}=\left({\boldsymbol{X}}_{i,b},{\boldsymbol{X}}_{i,k}\right)\) are pre-treatment background covariates and key indicators, \(\left({Z}_{i},{T}_{i}\right)\) are treatment-related variables with \({Z}_{i}\) standing for the surgery received by patient \(i\) and \({T}_{i}\) being the time label of the surgery, and \(\left({\boldsymbol{Y}}_{i,k},{C}_{i}\right)\) are the post-treatment outcome variables with \({{\boldsymbol{Y}}}_{i,k}\) being the key indicators after treatment and \({C}_{i}\) being the medical cost. Note that we encode \({T}_{i}\)’s in a reverse chronological order for convenience, where the present time is encoded as 0 and an earlier time is encoded as a negative number. In case that the time label \({T}_{i}\) is not precisely known for some cases, we discretize \({T}_{i}\)’s in an appropriate granularity, e.g., a month or a year, for simplicity. Table 2 demonstrates the medical records of a few typical POP patients, with elements of \({{\boldsymbol{R}}}_{i}\) explicitly highlighted. More details about these datasets are provided in Supplementary Materials. Variables displayed in Table 2 were selected from a large number of variables in the original medical records based on clinical knowledge and evidence from the literature. Only important variables that are closely related to POP surgery selection with clear medical significance were selected for the establishment of a concise and interpretable AI model for surgery recommendation.

Method overview

A straightforward solution to the aforementioned surgery recommendation problem is to build a machine-learning prediction model with the feature vector \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i}\) as predictors to predict the surgery, e.g., generalized logistic regression, naïve Bayes, decision tree, or neural network. Although such a simple strategy often leads to good predictions when there is sufficient high-quality clinical data available as training data, it often suffers from untransparent decision-making procedures and unstable performance when the training dataset is relatively small (which is often the case in clinical studies).

In this study, we propose an alternative strategy for surgical recommendation under the framework of MCDM, where we characterize the impacts of each surgery on the patient from multiple decision-making dimensions quantitatively and compromise across these dimensions wisely. To characterize the impacts of surgery treatment \(s\in {\mathcal{S}}\) on a patient with pre-treatment covariates \({\boldsymbol{X}}=({\boldsymbol{X}}_{b},{\boldsymbol{X}}_{k})\), a series of prediction models are established to provide quantitative prediction on effectiveness, risk, cost, and complexity of surgery \(s\) for the specific patient, resulting in \({\rho }_{{e|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}},{\rho }_{{r|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}},{\rho }_{{c|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}},{\rho }_{{o|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) as the index values of effectiveness, risk, cost, and complexity, respectively. Moreover, an additional preference term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) is also calculated to reflect the “prior” preference on surgery \(s\) given the background covariates \({X}_{b}\) without considering the other decision-making dimensions. For conceptual and practical convenience, we normalize these index values so that they are all positive numbers with a higher \(\rho\) indicating a better performance of surgery \(s\) on the corresponding decision-making dimension for the patient.

Integrating all these quantitative indices for each surgery \(s\in {\mathcal{S}}\), we get the following surgery feature profiles:

where

By transforming the raw pre-treatment covariates \(X\) of a patient into the surgery feature profiles \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}={\left\{{\boldsymbol{F}}_{s}({\boldsymbol{X}})\right\}}_{s\in {\mathcal{S}}},\) we come up with a collection of new predictors summarizing the potential outcomes of taking different surgeries form multiple aspects, including effectiveness, safety, medical cost, operation complexity and so on. The transformation from \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) to \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) makes it possible to establish an interpretable model for surgery planning under the framework of MCDM, because the elements of \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) precisely align with the major concerns of a surgeon to make decisions in clinical practice. As we will show in detail in the next subsection, the transformation from \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) to \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) is non-trivial, because a lot of information beyond \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) is poured into \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) during the transformation, providing richer signals and broader perspectives for decision-making. When more decision dimensions beyond the proposed ones are under consideration, we can expand \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) for the additional dimensions.

Intuitively, a rational surgeon should always choose a surgery with a large preference term, higher effectiveness, lower risk, lower cost, and lower complexity for the patient, and make a wise compromise when there does not exist a single surgery that can optimize all decision-making dimensions simultaneously. Following such an intuition, we proposed in this study the following quantitative model for the probability of choosing surgery \(s\) by a surgeon with preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\) for a patient with pretreatment covariates \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) under an established surgery feature profile \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\):

where

being the decision preference vector of the surgeon with its elements as the weight parameters to balance different decision-making dimensions. Here, we chose to fix \({\alpha }_{p}=1\) and constrained \({\alpha }_{e},{\alpha }_{r},{\alpha }_{c},{\alpha }_{o}\ge 0\) to better keep the probabilistic interpretation of \({\mathbb{P}}\left(s|{\boldsymbol{X}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} ;{\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\right)\), and made sure that a surgery associated with larger index values enjoys a higher chance to be selected. Moreover, we noted that the model in Eq. (4) was equivalent to the following log-linear model with concise vector form that was widely adopted in machine learning:

with \(\log {\boldsymbol{F}}_{s}\left(\boldsymbol{X}\right)\), instead of \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{s}\left(\boldsymbol{X}\right)\), as the predictors. Though the majority of the five terms (i.e., \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\), \({\rho }_{{e|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}},\) and \({\rho }_{{r|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\)) had clear probabilistic meanings, we chose to define the model for \({\mathbb{P}}\left(s|{\boldsymbol{X}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} ;{\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\right)\) by Eq. (4), instead of its equivalent long-linear form, to better highlight its probabilistic interpretation.

Given the surgery feature profiles \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\), personalized surgical planning can be achieved for a patient with feature vector \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) and a surgeon with decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\) by maximizing \({\mathbb{P}}\left(s|{\boldsymbol{X}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} ;{\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\right)\), i.e., recommending

The recommended surgery \({\hat{s}}_{{\boldsymbol{X}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}\) is personalized from both the patient’s and the surgeon’s perspectives, because it is determined by the patient feature vector \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) and the surgeon preference vector \(\alpha\). Under such a framework, a surgeon with a specific decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\) would give differentiated surgical recommendations to patients with different feature vectors, while a patient with a specific feature vector \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) might receive different surgical treatment recommendations from surgeons with different preference vectors.

In this study, we refer to the surgical recommendation based on target function \({\mathbb{P}}\left(s|{\boldsymbol{X}};{\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} \right)\) in Eq. (4) with the preference term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) established by generalized logistic regression as a MUDI recommendation. Figure 1 demonstrates the overall architecture of MUDI, which indicates that MUDI contains two primary stages: a preparation stage where surgery feature profiles \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) are estimated based on multiple information sources (e.g., literature, domain knowledge, and historical medical records), and an application stage where the feature vector \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) of the patient and the decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\) of the surgeon are fed to MUDI for personalized surgical planning according to the estimated \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\). Hereinafter, we refer to the preparation stage for estimating \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) as MUDIF, and the application stage for treatment recommendation as MUDIA, respectively. Additionally, in case the decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\) of the surgeon is unknown, we also need to estimate \({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\) properly based on observed data via an additional estimation stage referred to as \({{\rm{MUDI}}}_{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}\) .

Establishment of the surgery feature profiles \({F}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) via \({\rm{MUD}}{{\rm{I}}}_{F}\)

Summarizing key characteristics of the involved surgeries in multiple decision-making dimensions, the surgery feature profiles \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}={\left\{\boldsymbol{F}_{s}\left(\boldsymbol{X}\right)\right\}}_{s\in {\mathcal{S}}}\) play a critical role in MUDI. In principle, surgery feature profiles \({\boldsymbol{F}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) can be estimated from clinical data with the support of domain knowledge. In practice, however, because each element of \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{s}\left({\boldsymbol{X}}\right)\) is a complicated function of surgery \(s\) and patient feature vector \({\boldsymbol{X}}\), it is often challenging to develop reliable prediction models for \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{s}\left({\boldsymbol{X}}\right)=\left({{\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}},\rho }_{{e|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}},{\rho }_{{r|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}},{\rho }_{{c|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}},{\rho }_{{o|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\right)\) in its general form. Considering that surgery \(s\) is often the major factor in determining the risk, medical cost, and operational complexity of surgeries for POP, here we choose to simplify \({\rho }_{{r|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\), \({\rho }_{{c|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) and \({\rho }_{{o|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) to functions of surgery \(s\) only via the following approximation:

where \({\rho }_{{r|s}}\), \({\rho }_{{c|s}}\) and \({\rho }_{{o|s}}\) stand for the corresponding average values over the patient population. In this subsection, we will discuss how to establish the concrete formulation of the simplified feature profile

based on multiple information sources, including medical literature, domain knowledge, and a collection of historical medical records \({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}={\left\{{{\boldsymbol{R}}}_{i}\right\}}_{1\le i\le n}\) of \(n\) patients.

First, we consider the specification of the three patient-independent indices \({\rho }_{{r|s}}\), \({\rho }_{{c|s}}\) and \({\rho }_{{o|s}}\). Because short-term and long-term complications are the major risks of POP-related surgeries, we specify the risk index \({\rho }_{{r|s}}\) based on the complication rate of surgy \(s\). Let \({r}_{s}\) be the overall complication rate of surgy \(s\) reported by large-scale cohort studies on POP49,50, \({o}_{s}\) be the complexity score of surgery \(s\) based on domain knowledge, and \({\bar{C}}_{s}\) be the average cost for receiving surgery \(s\), i.e.,

We specify the risk index, the cost index, and the complexity index of surgery \(s\) as:

Next, we consider the evaluation of \({\rho }_{{e|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\), the personalized effectiveness index of surgery \(s\) for a patient with pretreatment covariates \({\boldsymbol{X}}\). Strict efficacy evaluation of surgeries typically involves strict clinical trials or cohort studies, which are limited. Here, we simplify the problem for conceptual and practical convenience by quantifying \({\rho }_{{e|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) with the rough probability of cure, which can be estimated based on the medical records in \({\boldsymbol{D}}\). To be concrete, for each patient \(i\) in \({\boldsymbol{D}}\), define her observed improvement of POP-Q score (refer to Supplementary Material Note 2 for more details) due to the surgery she received as the difference of her key indicators after and before the surgical treatment, i.e.,

Let \({{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{s}\) be the random vector standing for the potent improvement of a patient by receiving surgery \(s\). We can learn the distribution of \({{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{s}\) based on \({\left\{{\mathbf{\Delta}}_{i}\right\}}_{i\in {{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s}}\) by specifying an appropriate parametric model for \({{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{s}\). Once the probability distribution of \({{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{s}\) is established, the effectiveness of surgery \(s\), which is specified as the cure probability, can be calculated as follows:

where \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{X}}}}_{k}\) is a pre-defined value range indicting the quantitative standard for curation.

A last, we establish the prior preference term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) by a regular machine learning method (e.g., logistic regression, decision tree, naïve Bayes classifier or neural network) to model the probability of selecting surgery \(s\) for patient \(i\) solely based on her raw pretreatment covariates \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i}.\) Such a term plays three roles in MUDI. First, it summarizes the “prior preference” for surgery \(s\) based on only the shallow-level information in \({\boldsymbol{X}}\), before deep-level information in \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) (i.e., the four additional dimensions) is utilized. Second, it serves as a baseline for evaluating MUDI, because MUDI would degenerate to the baseline when \({\alpha }_{e},{\alpha }_{r},{\alpha }_{c},{\alpha }_{o}\) are all set to 0. Third, it serves as a supplement of the risk term \({\rho }_{{r|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\). Ideally, the risk term \({\rho }_{{r|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) should fully measure the personalized risk of a patient with pre-treatment covariates \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) for taking surgery \(s\). In this study, however, considering that it’s infeasible to establish a complete risk model, i.e., \({\rho }_{{r|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\), due to limitations on clinical data and lack of high-quality follow-up studies, we retreated to a simplified risk model, i.e., \({\rho }_{{r|s}}\), which reports the average risk of taking surgery \(s\) without specifying the personalized risk for a particular patient with pre-treatment covariates \({\boldsymbol{X}}\). The simplified risk model \({\rho }_{{r|s}}\) is incomplete, but can be backed up by the preference term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\), because experienced surgeons tend to avoid high-risk surgeries based on patient covariates \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) in clinical practice and such preference is typically well encoded in the term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\). Details of the establishment of the prior preference term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\), or equivalently the baseline method, via various machine learning models can be found in Method.

Specification of the decision-making preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) via \({\bf{MU}}{{\bf{DI}}}_{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}\)

In case the decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) is known for a surgeon, we directly specify \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) to the known value; otherwise, we need to estimate it properly. A possible way to estimate the unknown α is to consult a group of carefully selected medical experts for their opinions on the specification of α under the framework of MCDM via the AHP or the MAU. Such a traditional strategy, however, often suffers from the subjectivity of human experts, untransparent interpretation, deviation from the spirit of evidence-based medicine, and low efficiency in implementation due to a tedious iterative voting procedure of experts.

In this study, we propose an alternative data-driven strategy to estimate α that does not require direct inputs from human experts anymore. Our key argument relies on the fact that real clinical datasets, e.g., \({D}_{s}\) and \({D}_{m}\) in this study, contain rich information about how a surgeon balances different decision-making dimensions in practice. If we reformulate the surgery recommendation problem as a prediction problem aiming to predict the actual surgery a patient received based on her surgery feature profiles \({F}_{S}={\left\{{F}_{s}\left(X\right)\right\}}_{s\in S}\), we would be able to learn statistical rules about surgery selection, based on what has been done by the surgeon via a collection of his/her medical records \({\mathcal{D}}={\left\{{{\boldsymbol{R}}}_{i}\right\}}_{1\le i\le n}\). To be concrete, for patient \(i\), let

be her surgery recommendation probability under decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\), where probability \({\mathbb{P}}\left({s}_{1}|{{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i},{\boldsymbol{\alpha }};{{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\right)\) is defined in Eq. (4). The cross-entropy loss function below

gives the log-likelihood of dataset \({\mathcal{D}}={\left\{{{\boldsymbol{R}}}_{i}\right\}}_{1\le i\le n}\) under the prediction model, which quantifies how it is likely to observe the surgery selections in dataset \({\mathscr{D}}\) under the prediction model equipped with parameter vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\). Based on the maximum likelihood principle in statistical inference, it’s reasonable to specify \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) with the maximizer of \(l\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\right)\), i.e., the maximum likelihood estimate

where \(\Theta\) is the admissible space of parameter \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\). The above optimization can be achieved conveniently by standard software for logistic regression51. Compared to the conventional expert-driven strategy for MCDM, this data-driven strategy enjoys the advantages of more objective and transparent results and more efficient implementation.

In establishing the standard MUDI, we quantified the preference of patients by several main questions (e.g., cost matter, sexual life, vagina reserve, mesh aversion). For example, if a patient shows great tolerance to cost, we would exclude the cost dimension from consideration by setting the corresponding element \({\alpha }_{c}\) to be zero. If a patient is averse to mesh, we would set the prior probability \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) of mesh procedures (e.g., ATVM, PTVM) to a value (e.g., 0.01) to reflect her preference. Similarly, if the patient has sexual life or wants to preserve the vagina, we would set the prior probability \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) of the surgery against it (i.e., Colpocleisis or \({s}_{6}\)) to a low value (e.g., 0.001).

In practice, considering that a group of surgeons from the same medical center often share similar decision-making preferences, we can pool medical records from a medical center together to estimate the center-level decision-making preference vector in the same way.

Application of MUDI in surgical treatment recommendation for POP

To establish MUDI for surgical planning for POP patients, we learned the surgery feature profiles \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) and decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) for MUDI from the training dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,t}\) via the \({{\rm{MUDI}}}_{{\boldsymbol{F}}}\) module and the \({{\rm{MUDI}}}_{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}\) module as shown in Fig. 2. The trained model is then applied to the testing datasets \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,v}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{m,v}\) for internal and external performance evaluation, respectively. In the internal performance evaluation, we used the actual surgeries chosen in the original medical records in \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,v}\) as the gold standard. In the external performance evaluation, 20 human experts were invited to make procedure recommendations for the 100 cases in \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{m,v}\) independently. Based on their seniority and expertise, the 20 experts were divided into 3 groups: the first group contained 8 members of the Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery Society of China (URPSC), the most authoritative academic organization in China on the field; the second group covered 6 senior gynecologists who had clinical practice of >10 years in major medical centers of China (i.e., tertiary hospitals recognized by the Chinese government) and had received formal urogynecology training for at least 1 year; the third group was composed of 6 junior surgeons who had clinical practice of 5–8 years in major medical centers of China but had never received formal urogynecology training. We referred to these three groups as “top experts”, “experts” and “junior surgeons”, respectively. Treating the most voted surgery by the top experts as the gold standard, the top-\(k\) accuracy of MUDI (see the Method section for detailed definition) was calculated and reported in Fig. 2, which equals 60% in internal validation and 62% in external validation for \(k=1\), and both increases to 92% for \(k=3\). The top-\(k\) accuracy of each human expert group for the external validation dataset is also listed in Fig. 2 for comparison. The top-\(k\) accuracy of human experts equals 55%, 75%, and 82% for \(k\) = 1, 2, and 3 in the top expert group, and decreases to 27%, 47%, and 61% in the inexperienced surgeon group.

These results reveal the following insights: (a) surgery recommendation for POP patients is a challenging task with significant uncertainty where inexperienced surgeons often fail to identify the appropriate surgery and even top experts often recommend different surgeries for the same patient due to heterogeneous preference on different decision-making dimensions; (b) MUDI enjoys excellent performance in external evaluation that is comparable to top experts and significantly better than experts and inexperienced surgeons; (c) MUDI demonstrates strong robustness with small performance variation between internal and external evaluations. These results suggest that MUDI is a reliable approach for surgical treatment planning with transparent interpretation, under the support of the transformed predictors \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\).

To further quantify how MUDI’s recommendation would influence surgeons in practice, we conducted an additional experiment where surgeons of 3 different levels as defined above were asked to make decisions for provided cases independently and then with the aid of MUDI. In case a surgeon gave a recommendation inconsistent with MUDI, we would ask the surgeon whether he/she was willing to change his/her mind and accept MUDI’s recommendation. In the experiment, the 3 groups of surgeons showed an average of 49–97% willingness to change recommendations (either the surgeries or their rank) and achieved an improvement of accuracy by 21% for top-1, and 27% for top-3 recommendations. It indicated that surgeons were willing to accept the recommendations of MUDI in practice, and the MUDI-aided decision-making improved surgery recommendation quality concerning our “gold” standard. We believe that the way MUDI makes recommendations plays a key role here in gaining the trust of surgeons. Instead of just recommending the top-ranked candidate surgeries, MUDI explains explicitly how the recommendation was made (as demonstrated in Fig. 1), with the predicted consequences of each candidate surgery sufficiently exposed in various decision dimensions with uncertainty. These facts make it much easier for surgeons to understand the scientific logic behind MUDI, reevaluate their decisions, and make their own choice after being reminded of MUDI’s recommendation, as pointed out by Wang et al.52.

To obtain real-world evidence to support the advantage of utilizing MUDI over the baseline without MUDI, we followed a small prospective cohort of 122 patients who received POP procedures between Sep. 2021 and Aug. 2022 to collect their symptom information, POP-Q score, complications, and POP-related questionnaires. We partitioned the 122 patients into 4 groups, namely Top 1 (74 patients), Top 2 (27 patients), Top 3 (10 patients), and Others (11 patients), based on how the actual surgeries they received matched MUDI’s recommendations. For example, all patients in the Top 2 group received the second-best recommendation by MUDI as their actual treatment. Efficacy and safety performance of surgeries were compared across different patient groups. If MUDI worked well in practice, we would observe better results in the Top 1 group than in other groups. Although we cannot evaluate the long-term performance yet because the cohort is still ongoing, we found that the Top 1 group reached the highest 3-month anatomic satisfaction rate, the highest 3 month average PFIQ-7 (Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire short form)53 score improvement, and the highest proportion of patients who reported very much better in PGI-I (Patient Global Impression of Improvement questionnaire for urogenital prolapse)53. Moreover, for patients who underwent ULS, the Top 1 group reached the lowest 1 year reoccurrence rate. Although not conclusive, these evidence indicate that MUDI has good potential to be more effective in the real world.

Illustrating examples of personalized surgical planning via MUDI

To illustrate how the trained MUDI model can help surgeons achieve personalized surgery planning in practice, we designed a thought experiment as shown in Fig. 3 to illustrate the decision-making procedure of two virtual surgeons with different decision preference vectors (i.e., surgeon \(I\) and \({II}\)) for two real patients (i.e., patient \(A\) and \(B\)) under MUDI. In this experiment, both virtual surgeons share the common surgery feature profiles \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\), which are learned from the training dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s}\) via the \({{\rm{MUDI}}}_{{\boldsymbol{F}}}\) module. A surgeon-specific decision preference vector is assigned for each of the two virtual surgeons via the \({{\rm{MUDI}}}_{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}\) module, where the vector \({{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}_{I}\) for surgeon \(I\) is learned from the uni-center dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,t}\), and the vector \({{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}_{{II}}\) for surgeon \({II}\) is learned from the multicenter dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{m}\). The two bar plots in Fig. 3 next to the two surgeons visualize the two decision preference vectors, from which we can see that the two virtual surgeons indeed prioritize various decision-making dimensions differently. Because patient A wants to preserve the vagina, we set the prior probability \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) of \({s}_{6}\) (i.e., Colpocleisis) to a low value of 0.001. In the end, the \({{\rm{MUDI}}}_{{\boldsymbol{A}}}\) module is called by each surgeon to generate probabilistic surgery recommendations for every patient as listed in Fig. 3.

The results in Fig. 3 reveal that the surgery recommendations by MUDI are patient-personalized as the same surgeon gave different recommendations to different patients due to their heterogeneity in pre-treatment background covariates and key indicators. Furthermore, the surgery recommendations by MUDI are also surgeon-personalized because different surgeons may recommend different surgeries to the same patient as they prioritize different decision-making dimensions.

Additional comparison to baseline methods

From the perspective of machine learning methodology, the key contribution of MUDI is the proposal of transforming the original pre-treatment features \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i}\) into a collection of new features that align well with the scientific logic of the application scenario and thus enjoy transparent interpretation, i.e., the surgery feature profiles \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}={\left\{{{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{s}({\boldsymbol{X}})\right\}}_{s\in {\mathcal{S}}}\). As we have shown previously, such a strategy yielded high-quality performance on surgery recommendations of POP patients. In practice, however, we can always stick with the original pre-treatment features \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i}\) as predictors for surgery treatment \({Z}_{i}\) to train a machine learning model for predictive surgical recommendation, e.g., generalized logistic regression, decision tree, Naïve Bayes, neural network, and so on. In this study, we refer to these simple predictive machine learning models with the \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i}\) as predictors as the baseline methods.

To compare MUDI to these baseline methods, given the cases in the training dataset \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,t}\), i.e., \({\left\{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i},{Z}_{i}\right\}}_{{i}{\in}{{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s,t}}\), we called the “multinom” function in the R package to establish the generalized logistic regression model, the “rpart” function to build the decision tree, the “naiveBayes” function to establish the Naïve Bayes model with the prior distribution of surgeries specified as their empirical frequencies and all continuous variables fitted by Gaussian distribution, the “tensorflow.keras” function to establish the full connect neural network. Details on the establishment of these baseline methods are reported in Method.

Given an established baseline method \({\mathcal{B}}\), e.g., logistic regression, we can specify the preference term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) of MUDI with the probabilistic recommendation by \({\mathcal{B}}\), resulting in a specific version of MUDI, referred to as \({MUD}{I}_{{\mathcal{B}}}\). Apparently, \({MUD}{I}_{{\mathcal{B}}}\) absorbs the output of baseline method \({\mathcal{B}}\) as the evidence from one of its decision-making dimensions, and the baseline method \({\mathcal{B}}\) can be treated as a special case of \({MUD}{I}_{{\mathcal{B}}}\) where the extra decision-making dimensions, including effectiveness, safety, medical cost, and operational complexity, are abandoned.

Table 3 summarizes the top-\(k\) accuracy of 6 competing methods, including the 4 established baseline methods and the corresponding versions of MUDI, in internal and external validation, respectively. From the table, we can gain the following insights: (a) remaining robust between internal and external validations, the performance of MUDI is competitive in all cases; (b) although some baseline methods achieve a slightly higher prediction accuracy than MUDI in internal validation, they all have a significant performance degeneration in external validation; (c) every baseline method \({\mathcal{B}}\) is dominated by its MUDI-enhanced counterpart in terms of robustness as well as accuracy; (d) achieving the highest recommendation accuracy in external evaluation, MUDI is the strongest version of the MUDI-series methods. These results confirm the advantages of MUDI over traditional machine learning approaches, and cast light on a general principle for establishing reliable and interpretable AI models that was often overlooked in the past: re-organizing the input features appropriately according to the scientific logic of the application problem often leads to a better solution than brute-force model fitting of raw features without explicit interpretation.

The interactive online platform of MUDI for POP-related surgeries

To promote the clinical application of MUDI in practice, we established an interactive online platform of MUDI for POP-related surgeries, whose graphical interface is illustrated in Fig. 4. By loading pre-treatment background covariates and key indicators of the patient from the medical record database, and asking the patient a series of questions (Q1-Q7) in a pre-defined order and the surgeon an additional question (Q8), the platform outputs the probabilistic recommendation by MUDI automatically with the reasoning procedure visualized intuitively. Based on the feedback we received from surgeons who have experienced experimental use of the platform, we found that such a platform could significantly improve the decision accuracy of inexperienced surgeons and the communication efficiency between surgeons and patients. Since the algorithm is the core, similar online platforms for other situations can be developed in the same fashion with slight modifications of the interface as the module of the framework is adaptive.

This tool could ease communications between surgeons and patients via an intuitive graphical illustration of the decision-making process. Webpage URL: https://female-pelvic-floor-disease-diagnostic-tool.v-dk.com/.

Discussion

Combined with medical evidence, transforming plain pre-treatment covariates of a patient into a series of surgery feature profiles to reflect the multiple decision-making dimensions in surgery selection and estimating the surgeon-specific decision preference vector from clinical data using the maximum likelihood principle, MUDI established a transparent and interpretable framework for intelligent surgical recommendation that is personalized for both patients and surgeons. Applied to surgical recommendations for patients with POP, MUDI achieved an excellent performance that was comparable to that of leading Chinese urogynecologists and considerably outperformed inexperienced surgeons. The data-driven methodology of MUDI provided a quantitative and objective approach to revealing and summarizing implicit medical knowledge for the treatment of complex diseases. Visualizing the logical steps behind MUDI with a user-friendly interface, we obtained a concrete and intuitive pipeline that may enable surgeons to better communicate with patients. Compared to ambiguous POP guidelines, the established pipeline is a more accessible tool for general practitioners who lack expertise in POP. Numerous developing countries suffer from a severe shortage of professional urogynecologists, especially in non-tertiary hospitals, where many patients with POP do not receive appropriate treatments, causing severe health implications and high medical expenses. With the help of MUDI, even doctors in non-tertiary hospitals without expertise in POP can efficiently identify suitable treatments for patients with POP and refer them to qualified experts at tertiary hospitals for complex procedures. We believe these efforts would alleviate the scarcity of urogynecologists, benefit a lot of patients, and enhance the overall effectiveness of the healthcare system in numerous countries.

However, there are certain limitations to the existing studies on MUDI. First, the \(\rm{MUDI}_{{\boldsymbol{F}}}\) module utilized highly simplified models to estimate the surgery feature vector \({F}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) for conceptual simplicity, which may have over-simplified the problem. Such a sub-optimal strategy highlights the strength of MUDI to achieve high-quality recommendations when indices of individual decision dimensions are roughly estimated. Second, extra efforts need to be conducted to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of the surgeon-specific decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) learned by \(\rm{MUDI}_{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}\). A carefully designed self-evaluation survey for the decision-making preference of experts in the involved medical center may serve as a gold standard for such an evaluation. Due to practical challenges in designing and conducting such a survey, however, we would like to reserve this important but challenging issue for future study. Additionally, we have to be careful in interpreting the estimated decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) due to the heterogeneity on the numerical scale of its elements. For example, \({\alpha }_{e}\) equals to 0.1 and 0.05 for the two virtual surgeons in Fig. 3, while \({\alpha }_{s}\) equals to 0.75 and 0.2 instead, which are around 4-8 times larger than \({\alpha }_{e}\). However, such a fact does not mean that virtual surgeons are 10 times more concerned about the operation complexity of surgery than its effectiveness. Instead, the huge difference between \({\alpha }_{e}\) and \({\alpha }_{o}\) is mainly because the variance of effectiveness indices is typically much larger than the variance of complexity indices, as shown in Fig. 1. Such a phenomenon would be alleviated if we could normalize the variance of different indices into the same scale. In practice, however, it is non-trivial to implement such an idea because some indices vary with the patient feature vector \({\boldsymbol{X}}\).

In this study, we assumed that the surgeon and the patient share a common interest in finding the “best” surgery for the patient in establishing the model. In practice, however, such an assumption may not always hold due to various reasons. When the interest of surgeons deviates significantly from the interest of patients, the recommendation of MUDI may not be the ideal choice anymore. Anyway, serving as a decision maker, according to the Recommendation on the Ethics of AI54, MUDI requires human surgeons to oversee its use. While the recommendation of the model is to promote surgeon-patient communication, the divergence of opinion under special circumstances needs to be resolved by shared decision-making.

Additionally, we would like to emphasize that MUDI is tightly tied to evidence-based medicine. MUDI is composed of two key components: surgery feature profiles \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}={\left\{{{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{s}({\boldsymbol{X}})\right\}}_{s\in {\mathcal{S}}}\), and decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\). Surgery feature profile \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{s}({\boldsymbol{X}})\) summarizes the multi-dimensional potential outcomes, e.g., the probability of cure and complications, of a patient with pre-treatment covariates \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) if she receives surgery \(s\in {\mathcal{S}}\) hypothetically. The construction of these potential outcomes in MUDI is completely evidence-based by summarizing medical knowledge, literature, and clinical data. Determination of decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\), the other key component of MUDI, however, is achieved by mimicking what has been done by human experts via fitting clinical data, and thus may deviate from the evidence-based best practice. Therefore, MUDI has essential two faces: one face towards evidence-based medicine related to the construction of surgery feature profiles \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}={\left\{{{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{s}({\boldsymbol{X}})\right\}}_{s\in {\mathcal{S}}}\), and one face towards mimicking expert behaviors related to the specification of decision preference vector \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\). Anyway, involving the evidence-based surgery feature profiles \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}={\left\{{{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{s}({\boldsymbol{X}})\right\}}_{s\in {\mathcal{S}}}\) as one of its key components, we are comfortable to claim that MUDI is partially evidence-based at least.

In practice, MUDI can be further enhanced and extended in multiple ways. First, it can be integrated into mobile terminals or hospital information systems to better serve patients and surgeons in more hospitals, and we would expect an enhanced MUDI when more real-world evidence becomes available via feedback from these terminals. Second, we can enhance the effectiveness module and the risk module by considering more factors, such as the recurrent rate, the reoperation rate, and the short/long-term complication rate from domestic large-scale cohort studies. We could also easily add other dimensions in the framework if needed. Third, though we have seen the advantages of MUDI in real-world validation, more systematic follow-up studies are needed to formally establish the statistical significance of these advantages. We have been promoting the clinical application of MUDI in practice nationwide and expect a better performance of MUDI in the larger scale validation. Last but not least, because the framework of MUDI and the online platform can be flexibly modified, we would like to apply MUDI to other diseases or situations with similar challenges and evaluate its performance. Shoulder surgery referral, which typically involves the consideration of multifaceted etiology, the experience of providers, and the burden of patient demands55, is a concrete example. Moreover, therapy selection in the early outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 before clear treatment guidelines were available is another example, as the severity of the disease, the patient’s condition (age, pregnancy, and renal function) must be comprehensively considered together with cost, side effects, and method of administration of the drug56. However, although the core of the problem is common and the framework is relatively mature, it is still necessary to adapt the model according to the main challenge of each situation. Due to the significant differences in the types and characteristics of variables, we may also face new difficulties in the data-driven-based processing of variables and the estimation of the relationships between variables, so we still need to explore them practically.

Methods

Evaluating the performance of MUDI via external validation

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by Peking Union Medical College Hospital’s independent ethics committee (approval number: I-24PJ1291; Feb. 25th, 2020). Informed consent was waived by the ethics committee because this was an observational study, no additional information or samples were taken other than medical record data, and all sensitive information was removed at the time of data collection.

Let \({\mathcal{M}}({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha }})\) be a well-trained MUDI model equipped with model parameters (\(({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha }})\)). The performance of \({\mathcal{M}}({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha }})\) on a testing dataset can be evaluated by the consistency between recommendations by \({\mathcal{M}}({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}},{\boldsymbol{\alpha }})\) and practically implemented surgeries for cases in the testing dataset.

To be concrete, assume that there are \(m\) cases in the test dataset, with \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{j}\) and \({Z}_{j}\) being the pre-surgery covariates and the practically implemented surgery for the \(j\)-th case, respectively. For an arbitrary surgery recommendation method \({\mathcal{M}}\), let \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{j,k}\) be the top-\(k\) surgeries recommended by \({\mathcal{M}}\) for case \(j\). We define the top-\(k\) accuracy of \({\mathcal{M}}\) as follows:

A \({\gamma }_{k}\) closer to 1 indicates a better consistency between the recommended surgeries and the practically implemented ones, suggesting that the recommendation method \({\mathcal{M}}\) can better predict the behavior of the target surgeon in practice.

Implementing MUDI for POP surgery planning

To implement MUDI for POP surgery recommendation based on the simplified surgery feature profiles in (7), we need to finish the following additional tasks: (a) specify the preference term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) by choosing \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{b}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{k}\) wisely and fitting them with appropriate parametric distributions; (b) specify the effectiveness index \({\rho }_{{e|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) according to Eq. (13) by fitting the surgery-specific improvement \({{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{s}\) with an appropriate parametric distribution and defining \({{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{X}}}}_{k}\), the quantitative standard for curation concerning the critical indicator \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{k}\), explicitly; and (c) estimate the three patient-independent indices \({\rho }_{{r|s}}\), \({\rho }_{{c|s}}\) and \({\rho }_{{o|s}}\) precisely according to Eq. (11) based on the medical data of POP patients.

For task (a), according to domain knowledge on POP, we choose

where variable Age stands for the patient’s age at the time of surgery, variable BMI stands for her Body Mass Index, variable MA stands for a binary indicator Mesh Aversion highlighting the patient’s unwillingness to mesh implantation surgeries due to objective contraindication or subjective concerns (refer to Supplementary Material Note 3 for more details), variable VR stands for another binary indicator Vagina Reservation highlighting the patient’s request to reserve vagina during treatment, and vector POP-Q Scores stands for a 3-dimensional measurement for the severity of pelvic floor dysfunction at 3 anatomic positions in the pelvic cavity (namely, Ba, C, and Bp). More details about these pre-treatment variables and the reasons for choosing them as \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{b}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{k}\) are further explained in the Supplementary Materials. Because Age, BMI, and POP-Q scores are all continuous variables that are roughly normally distributed, we model them with Gaussian distribution in this study. The two binary variables, i.e., \(\text{MA}\) and \(\text{VR}\), are modeled with Bernoulli distribution instead.

For task (b), we model \({{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{s}\) with a 3-dimensional Gaussian distribution with independent components, whose mean vector and variances are estimated based on \({\left\{{{\mathbf{\Delta }}}_{i}\right\}}_{i\in {{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{D}}}}_{s}}\) with \({{\mathbf{\Delta }}}_{i}={{\boldsymbol{Y}}}_{i,k}-{{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{i,k}\), and specify a quantitative standard for cured POP concerning the critical indicator \({\boldsymbol{X}}_{k}\) as \({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{X}}}_{k}=\left(-\infty ,0\right]\times \left(-\infty ,-\frac{2}{3}{\rm{Tvl}}\right]\times (-\infty ,0]\) based on the literature57,58, where TVL stands for the Total Vaginal Length of the patient. Table 4 reports the fitted Gaussian distributions of \({\left\{{{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{s}\right\}}_{s\in {\mathcal{S}}}\).

For task (c), we listed in Table 4 the complication rate and operational complexity of every involved surgery obtained from literature, and the corresponding average medical cost calculated from the medical records. Concrete values of \({\rho }_{{r|s}}\), \({\rho }_{{c|s}}\) and \({\rho }_{{o|s}}\) are calculated according to Eq. (11) and reported in Table 4 as well.

Details of the established baseline methods

Tables 5–6 and Figs. 5–6 summarize the key information of the 4 established baseline methods.

Multinomial logistic regression

To generate a probabilistic recommendation of surgery via multinomial logistic regression, we calculate the preference term \({\rho }_{{p|s},{\boldsymbol{X}}}\) as below:

where \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{{s}}\) is the parameter vector specific to surgery \(s\).

Naïve Bayes

Let \({\pi }_{s}\) be the prior popularity of surgery \(s\) reflecting the overall probability to choose surgery \(s\) in practice, and \({f}_{{\boldsymbol{X}}{|s}}\) be the conditional density function of pre-treatment covariates \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) in the subpopulation of patients who have received surgery treatment \(s\). Both \({\pi }_{s}\) and \({f}_{{\boldsymbol{X}}{|s}}\) are also important factors in the decision-making procedure, because a more popular surgery treatment (i.e., with a larger \({\pi }_{s}\)) and better matches the pre-treatment covariates of the patient (i.e., with a higher \({f}_{{\boldsymbol{X}}{|s}}\)) is more preferred, when the other factors are fixed.

Decision tree

Decision tree learning employs a divide-and-conquer strategy by conducting a greedy search to identify the optimal split points within a tree. This process of splitting is then repeated in a top-down, recursive manner until all, or the majority of records have been classified under specific class labels. This algorithm utilizes Gini impurity to identify the ideal attribute to split on. Gini impurity measures how often a randomly chosen attribute is misclassified with Gini Impurity = 1 − ∑(pi)2 where pi represents the probability of classifying a random data point into surgery i.

Neural network

A fully connected neural network is constructed using Sigmoid as the activation function, adaptive moment estimation (Adam) as the optimizer, and sparse categorical cross-entropy as the loss function. The network contains one input layer, one hidden layer, and one output layer.

Data availability

The minimal dataset that would be necessary to interpret, replicate, and build upon the methods or findings reported in the article is available through email requests to the corresponding authors.

Code availability

The software codes are publicly available at the following links: https://female-pelvic-floor-disease-diagnostic-tool.v-dk.com/. The source codes are available upon request to the corresponding authors for academic use.

References

Loftus, T. J. et al. Artificial intelligence and surgical decision-making. JAMA Surg. 155, 148–158, (2020).

Maher, C. et al. Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, Cd012376 (2016).

Burstein, H. J. et al. Customizing local and systemic therapies for women with early breast cancer: the St. Gallen international consensus guidelines for treatment of early breast cancer 2021. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1216–1235 (2021).

Fatoye, F., Yeowell, G., Wright, J. M. & Gebrye, T. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions following total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 141, 1761–1778 (2021).

Hughes, C. A., Gose, E. E. & Roseman, D. L. Overcoming deficiencies of the rule-based medical expert system. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 32, 63–71, (1990).

Bartels, P. H., Thompson, D., Montironi, R., Mariuzzi, G. & Hamilton, P. W. Automated reasoning system in histopathologic diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer and its precursors. Eur. Urol. 30, 222–233 (1996).

Ravdin, P. M. et al. Computer program to assist in making decisions about adjuvant therapy for women with early breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 980–991 (2001).

Hermans, C. et al. Hemophilia treatment in 2021: choosing the“optimal” treatment using an integrative, patient-oriented approach to shared decision-making between patients and clinicians. Blood Rev. 52, 100890 (2022).

Banjar, H. R. et al. Web-based expert system with quick response code for beta-thalassemia management. Health Inform. J. 27, 1460458221989397 (2021).

Fuest, K. E. et al. Clustering of critically ill patients using an individualized learning approach enables dose optimization of mobilization in the ICU. Crit. Care 27, 1 (2023).

Granda Morales, L. F., Valdiviezo-Diaz, P., Reátegui, R. & Barba-Guaman, L. Drug recommendation system for diabetes using a collaborative filtering and clustering approach: development and performance evaluation. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e37233 (2022).

Barrett, C. D. et al. Evaluation of quantitative decision-making for rhythm management of atrial fibrillation using tabular Q-learning. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e028483 (2023).

Bonaccorsi, G. et al. Predicting treatment recommendations in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J. Biomed. Inf. 118, 103780 (2021).

Andrew, T. W. et al. Machine-learning algorithm to predict multidisciplinary team treatment recommendations in the management of basal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 126, 562–568 (2022).

Lin, F. P., Pokorny, A., Teng, C., Dear, R. & Epstein, R. J. Computational prediction of multidisciplinary team decision-making for adjuvant breast cancer drug therapies: a machine learning approach. BMC Cancer 16, 929 (2016).

Dogan, A. et al. A utility-based machine learning-driven personalized lifestyle recommendation for cardiovascular disease prevention. J. Biomed. Inf. 141, 104342 (2023).

Havrilesky, L. J. et al. Patient preferences for attributes of primary surgical debulking versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy for treatment of newly diagnosed ovarian cancer. Cancer 125, 4399–4406 (2019).

Somashekhar, S. P. et al. Watson for oncology and breast cancer treatment recommendations: agreement with an expert multidisciplinary tumor board. Ann. Oncol. 29, 418–423 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. Using artificial intelligence (Watson for Oncology) for treatment recommendations amongst Chinese patients with lung cancer: feasibility study. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e11087 (2018).

Juhn, Y. & Liu, H. Artificial intelligence approaches using natural language processing to advance EHR-based clinical research. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 145, 463–469 (2020).

Liang, H. et al. Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric diseases using artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 25, 433–438 (2019).

Gupta, R. et al. Artificial intelligence to deep learning: machine intelligence approach for drug discovery. Mol. Divers 25, 1315–1360 (2021).

Tonn, J. C., Thon, N., Schnell, O. & Kreth, F. W. Personalized surgical therapy. Ann. Oncol. 23, x28–32, (2012).

Moldovan, F., Gligor, A. & Bataga, T. Structured integration and alignment algorithm: a tool for personalized surgical treatment of Tibial Plateau fractures. J. Pers. Med. 11, 190 (2021).

Fu, F. et al. Rapid vessel segmentation and reconstruction of head and neck angiograms using 3D convolutional neural network. Nat. Commun. 11, 4829 (2020).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 42, 60–88 (2017).

Qiu, S. et al. Multimodal deep learning for Alzheimer’s disease dementia assessment. Nat. Commun. 13, 3404 (2022).

Dayan, I. et al. Federated learning for predicting clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 27, 1735–1743 (2021).

Raghunath, S. et al. Prediction of mortality from 12-lead electrocardiogram voltage data using a deep neural network. Nat. Med. 26, 886–891 (2020).

Koo, K. C. et al. Long short-term memory artificial neural network model for prediction of prostate cancer survival outcomes according to initial treatment strategy: development of an online decision-making support system. World J. Urol. 38, 2469–2476 (2020).

Nimri, R. et al. Adjusting insulin doses in patients with type 1 diabetes who use insulin pump and continuous glucose monitoring: variations among countries and physicians. Diab Obes. Metab. 20, 2458–2466 (2018).

Komorowski, M., Celi, L. A., Badawi, O., Gordon, A. C. & Faisal, A. A. The artificial intelligence clinician learns optimal treatment strategies for sepsis in intensive care. Nat. Med. 24, 1716–1720 (2018).

Guo, H., Li, J., Liu, H. & He, J. Learning dynamic treatment strategies for coronary heart diseases by artificial intelligence: real-world data-driven study. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 22, 39 (2022).

min, X., Li, W., Yang, J., Xie, W. & Zhao, D. Dual-level diagnostic feature learning with recurrent neural networks for treatment sequence recommendation. J. Biomed. Inf. 134, 104165 (2022).

Mardani, A. et al. Multiple criteria decision-making techniques and their applications—a review of the literature from 2000 to 2014. Econ. Res. Ekonomska Istraživanja 28, 516–571 (2015).

Hulbaek, M. et al. Pelvic organ prolapse and treatment decisions- developing an online preference-sensitive tool to support shared decisions. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 20, 265 (2020).

Adunlin, G., Diaby, V. & Xiao, H. Application of multicriteria decision analysis in health care: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Health Expect. 18, 1894–1905 (2015).

Practice bulletin no. 176: pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 129, e56–e72 (2017).

[Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and management of pelvic orang prolapse (2020 version)]. Zhonghua. Fu. Chan. Ke. Za. Zhi. 55, 300–306 (2020).

NICE Guidance - urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management: © NICE (2019) urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. BJU Int. 123, 777–803 (2019).

Lin, F. C., Gilleran, J. P., Powell, C. R. & Atiemo, H. O. To mesh or not mesh “apical prolapse,” that is the question! Neurourol. Urodyn. 43, 1626–1630 (2024).

Mazloomdoost, D., Crisp, C. C., Kleeman, S. D. & Pauls, R. N. Primary care providers’ experience, management, and referral patterns regarding pelvic floor disorders: a national survey. Int. Urogynecol. J. 29, 109–118 (2018).

Slade, E. et al. Primary surgical management of anterior pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review, network meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. Bjog 127, 18–26 (2020).

Hullfish, K. L., Trowbridge, E. R. & Stukenborg, G. J. Treatment strategies for pelvic organ prolapse: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 22, 507–515 (2011).

Jelovsek, J. E. Predicting urinary incontinence after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 28, 399–406 (2016).

Bordeianou, L. et al. Rectal prolapse: an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and patient-specific management strategies. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 18, 1059–1069 (2014).

Naldini, G., Fabiani, B., Sturiale, A. & Simoncini, T. Complex pelvic organ prolapse: decision-making algorithm. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 34, 189–192 (2019).

Koutsojannis, C., Lithari, C. & Hatzilygeroudis, I. Managing urinary incontinence through hand-held real-time decision support aid. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 107, 84–89 (2012).

Wihersaari, O. et al. Complications of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the 2015 finnish pelvic organ prolapse surgery survey study. Obstet. Gynecol. 136, 1135–1144 (2020).

Grzybowska, M. E., Futyma, K., Kusiak, A. & Wydra, D. G. Colpocleisis as an obliterative surgery for pelvic organ prolapse: is it still a viable option in the twenty-first century? narrative review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 33, 31–46 (2022).

Dunn, P. K. & Smyth, G. K. Generalized Linear Models With Examples in R 1st ed. 2018 edition, Vol. 562 (Springer New York, 2018).

Wang, D. Y. et al. Artificial intelligence suppression as a strategy to mitigate artificial intelligence automation bias. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 30, 1684–1692 (2023).

Szymczak, P., Grzybowska, M. E., Sawicki, S., Futyma, K. & Wydra, D. G. Perioperative and long-term anatomical and subjective outcomes of laparoscopic pectopexy and sacrospinous ligament suspension for POP-Q stages II-IV apical prolapse. J. Clin. Med. 11, 2215 (2022).

UNESCO. in UNESCO. General Conference, 41st, 2021. https://www.unesco.org/en/general-conference/41 (2021).

Taylor, K., Baxter, G. D. & Tumilty, S. Clinical decision-making for shoulder surgery referral: an art or a science? J. Eval. Clin. Pr. 27, 1159–1163 (2021).

Yildirim, F. S. et al. Comparative evaluation of the treatment of COVID-19 with multicriteria decision-making techniques. J. Health Eng. 2021, 8864522 (2021).

Jelovsek, J. E. et al. Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioral therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319, 1554–1565 (2018).

Nygaard, I. et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA 309, 2016–2024 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. Z190021) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12371269 and No. 81971366). The study sponsors played no role in the study design, conduct, data acquisition, analysis, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. We thank Professor Ye Lu from Peking University First Hospital (PUFH), Professor Xin Yang and Professor Xiuli Sun from Peking University People’s Hospital (PHPH), and Juan Liu from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (TAHGMU) for providing multi-center validation data and expert opinion as validation gold standard along with other members belonging to Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery Society of China (URPSC), professor Jinsong Han from Peking University Third Hospital, professor Luwen Wang from The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, and professor Jingye Xie from Nanjing First Hospital. We also appreciate contributions from Xiaohui Wang, PhD, Bing Ye, Bs, Zebin Lu, and Guangzhou Huibo Information Technology Co, Ltd, who/which worked on some groundwork for model development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.D. and Z.S. conceptualized the study. Z.D. and Z.L. wrote the code, trained the model, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with guidance from K.D., Z.S., and L.Z. Also, L.F. and C.W. contributed to the literature review, validation data collection, and analysis. All authors were involved in critical revisions of the manuscript, and have read and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, Z., Liu, Z., Fu, L. et al. Interpretable personalized surgical recommendation with joint consideration of multiple decisional dimensions. npj Digit. Med. 8, 168 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01509-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01509-1