Abstract

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is often diagnosed late, as early symptoms and effective screening tools are lacking, and genetic or familial factors explain only ~10% of cases. Leveraging longitudinal electronic health record (EHR) data may offer a promising avenue for early detection. We developed a predictive model using large language model (LLM)-derived embeddings of medical condition names to enhance learning from EHR data. Across two sites—Columbia University Medical Center and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center—LLM embeddings improved 6–12 month prediction AUROCs from 0.60 to 0.67 and 0.82 to 0.86, respectively. Excluding data from 0–3 months before diagnosis further improved AUROCs to 0.82 and 0.89. Our model achieved a higher positive predictive value (0.141) than using traditional risk factors (0.004), and identified many PC patients without these risk factors or known genetic variants. These findings suggest that the EHR-based model may serve as an independent approach for identifying high-risk individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is often diagnosed at late stages when treatment options are limited, resulting in the lowest 5-year survival rate among all major cancers (13%)1. However, when diagnosed at an early stage, the 5-year survival rate significantly improves to 44%2. Despite this potential survival benefit, screening is currently limited to a small subset of individuals with familial or genetic risk factors, representing only 5 ~ 10% of cases3. This limitation underscores the urgent need for effective early detection methods to expand screening to a broader population and improve survival outcomes.

Although MRI and CT scans have high sensitivity (93%) and specificity (89%) for detecting PC4, their widespread use in the general population is impractical due to high costs, resource overutilization, and increased risk of false positives, which may lead to unnecessary surgeries and associated mortality. To optimize detection efficiency, methods for identifying high-risk individuals for targeted screening are needed.

Electronic Health Record (EHR) data, which contains rich longitudinal medical histories at the individual level, may hold early signals of PC that remain underutilized. While blood-based liquid biopsy tests (e.g., CA19-9) show promise for early detection5, EHR data offers complementary insights that blood tests alone might miss, such as the lack of personalized health history that EHR data provides, which is crucial for precision medicine6. EHR data is also more readily available in many healthcare settings, making EHR-based models more accessible and cost-effective, particularly in regions with limited access to advanced diagnostics. Furthermore, EHR-based models can integrate with other diagnostic tools, including liquid biopsies, to create a comprehensive diagnostic framework, potentially reducing false positives and unnecessary confirmatory tests in a synergistic way. This integration can enhance our understanding of disease mechanisms and progression, inform new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, and support personalized healthcare approaches6.

Recent advancements in deep learning have enabled more effective use of EHR data. In particular, Large Language Models (LLMs) have significantly impacted medical research by improving natural language processing, predictive analytics, and personalized treatment approaches7,8,9.

Inspired by the recent GenePT model10, which leverages NCBI text descriptions of individual genes with Open AI’s GPT-3.5 to generate gene embeddings—numerical representations that encode semantic relationships between genes for various downstream tasks—we hypothesized that LLM-generated embeddings of medical concept names could similarly capture contextual nuances, improving their representations for disease prediction.

To test this hypothesis, we generated embeddings for each medical concept name included in our longitudinal patient EHR data and conducted a comprehensive analysis. This included evaluating different model architectures and assessing the impact of including or excluding data close to the diagnosis (e.g., 0–3 months prior) on early prediction performance, with and without LLM embeddings. The findings from Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUMC) were further validated using EHR data from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC).

Results

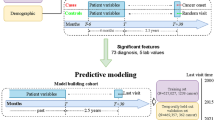

We utilized a Transformer architecture to develop a risk prediction model using EHR data in the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) format from CUMC and CSMC (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). This study leveraged embeddings from pre-trained models such as OpenAI GPT, Mistral, and a Relational Graph Convolutional Network (RGCN)11 to improve prediction performance (Fig. 1A). In addition to evaluating different embeddings, we assessed the impact of embedding size (e.g., 32 vs. 1536) and explored whether freezing or fine-tuning embeddings influenced model performance (Supplementary Table 2). Details on knowledge graph construction and RGCN model development are provided in the Supplementary Note 2.

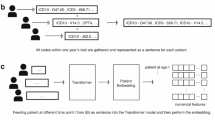

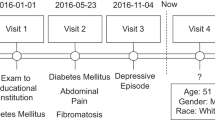

A An approach to integrate embeddings from pre-trained models. B A multi-label classification model designed to predict PC risk across multiple future time intervals (0–3, 3–6, 6–12, 12–36, and 36–60 months before diagnosis). This framework illustrates example patient data labeled as [0, 0, 0, 1, 1], indicating a PC diagnosis occurring 12–36 months after the last reported medical condition. The Transformer model predicts five binary outcomes, and the model’s predictions for the 12-36 month interval are evaluated based on the fourth label of the predicted probabilities. C Three binary classification models for early prediction at 3–6, 6–12, and 12–36 months before diagnosis, with augmented datasets. For example, to build the 12–36 month binary prediction model, we used patient data with a 0-3 month label [1,1,1,1,1] and excluded records reported less than 12 months before cancer diagnosis. By removing these proximal conditions, we adjusted the time gap between the last diagnosis and the cancer diagnosis, ensuring that the data aligns with the respective time intervals for each binary prediction model.

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed approach, we tested two modeling strategies: multi-label classification and binary classification. The multi-label classification model simultaneously predicted PC risk at 0–3, 3–6, 6–12, 12–36, and 36–60 months before diagnosis (Fig. 1B), while the binary classification model predicted PC at a specified interval of 3–6, 6–12, or 36–60 months before diagnosis (Fig. 1C).

With the multi-label classification model, the outcome included predicted probabilities across all five time intervals for each individual. However, including patients with proximal diagnoses (e.g., those with a label of[1,1,1,1,1]) in the evaluation of earlier predictions (e.g., 12–36 months) using their fourth predicted probabilities can inflate performance. This inflation occurs because the fourth label prediction may be influenced by preceding predictions based on conditions closer to the time of diagnosis.

To ensure a fair evaluation, we restricted performance evaluations for each specific time interval to patients whose diagnoses occurred within the respective interval. For example, for the 12–36 month prediction, only patients labeled [0,0,0,1,1] were included, and they were excluded from the 36–60 month analysis. Consequently, sample sizes decreased for earlier time intervals (Table 1), as it is uncommon for PC patients to have a prolonged interval between their last diagnosis and their PC diagnosis. To address this, we developed binary classification models with data augmentation (Fig. 1C).

Multi-label classification model

We observed a significant impact of increasing embedding size on improving prediction performance across all embedding models (baseline, RGCN, and GPT). However, the model using Mistral embeddings—the largest at 4096 dimensions—did not consistently show significant improvement compared to models using much smaller embeddings (e.g., 32 dimensions) across different prediction time windows. For the choice between fine-tuning and freezing, fine-tuning improved model performance for embeddings of size 32, whereas this impact diminished as the embedding size increased to 1536 (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2).

Among the different types of embeddings, GPT embeddings consistently yielded the best performance across most prediction intervals (Supplementary Table 2). While Mistral embeddings outperformed others in terms of maximum F1 score (p = 0.035) for the 6–12 month prediction window (Table 1), their AUROC and AUPRC performance was comparable to or lower than that of other models across all prediction windows (Supplementary Table 2). Compared to the CUMC, the CSMC model achieved higher AUROCs across all prediction intervals (Fig. 2). For instance, in the 12-36 month predictions, the CSMC model (AUROC = 0.824) outperformed the CUMC model (AUROC = 0.724). Additionally, GPT embeddings consistently improved performance in CSMC compared to baseline embeddings, whereas their impact varied in CUMC (Table 2).

Using CUMC data, GPT embeddings demonstrated the best performance among all embedding types evaluated (Baseline, RGCN, GPT, and Mistral embeddings). GPT embeddings also consistently improved prediction performance in CSMC data. Larger discrepancies in prediction performance between CUMC and CSMC were observed when using all available data (AUROC 0.673 vs. 0.858), but these differences significantly diminished after excluding data from the 0–3 months prior to diagnosis, due to substantial improvement in the CUMC model (AUROC 0.819 vs. 0.893; Table 1). This suggests a more pronounced data leakage effect in the CUMC dataset, potentially driven by control group characteristics that resemble early PC features.

To address potential data leakage caused by the inclusion of 0–3 month data due to its proximity to diagnosis, we evaluated the multi-label classification model’s performance after excluding the 0–3 month data and augmenting it into the 3–6 month prediction dataset. Removing 0–3 month data reduced the 3–6 month AUROC from 0.856 to 0.763 in CUMC and from 0.884 to 0.870 in CSMC. However, this adjustment improved AUROCs for earlier predictions (6–12, 12–36, and 36–60 months before diagnosis) in CUMC and for 6–12 month predictions in CSMC (Table 2).

Binary classification models

To address the limited sample size for earlier time interval predictions in the multi-label classification model, we developed three binary classification models to predict PC risk at 3-6, 6-12, and 12-36 months before diagnosis. For each model, data augmentation, as outlined in Fig. 1C, increased case samples to 1700, 1691, and 1719, respectively, with 785,332 control samples for CUMC, and 1082, 1078, and 1058 cases with 460,417 control samples for CSMC.

In these binary classification models, significant improvements were observed for the 3–6 month prediction at CUMC (p = 0.001) and the 6–12 month prediction at CSMC (p = 0.032) when using GPT embeddings (Fig. 3). While the GPT embedding model showed lower performance for the 12–36 month prediction, the differences were not statistically significant (CUMC: p = 1.0; CSMC: p = 0.933). Although the binary models used larger sample sizes, they did not outperform the multi-label model that excluded 0–3 month data.

LIME analysis

According to the LIME analysis results from both the CUMC and CSMC datasets (Supplementary Fig. 4), most of the top-ranked features were either directly related to the pancreas (e.g., cyst of pancreas, pseudocyst of pancreas) or known risk factors and symptoms such as type 2 diabetes, acute or chronic pancreatitis, and abdominal pain. In addition to these, several less-established features also emerged as potential early indicators, including disorder of the kidney and/or ureter, retention of urine, pure hypercholesterolemia, and liver disease.

When comparing LIME features between the baseline and GPT embedding models, the baseline model more frequently surfaced features with unclear relevance, such as closed fractures or unrelated musculoskeletal conditions, whereas the GPT embedding model consistently prioritized more interpretable and clinically meaningful features (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Evaluation of the clinical utility of the model

Using binary classification models for 3–6, 6–12, and 12–36 months before diagnosis, we evaluated the clinical utility of the EHR-based model compared to traditional risk factors (CA19-9, type 2 diabetes, pancreatitis) and genetic variants associated with PC (Supplementary Table 3). To assess the practical effectiveness of the model, we used positive predictive value (PPV) as the primary clinical utility metric (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4).

Compared to traditional risk factors, the EHR-based model consistently achieved higher PPVs across all time intervals, albeit at the cost of relatively lower sensitivity (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4). However, the sensitivity of the EHR-based model can be adjusted by modifying the classification threshold, with the optimal threshold determined based on screening capacity, which depends on factors such as cost and hospital resource utilization.

For example, as shown in Table 3, to achieve 50% sensitivity, the EHR-based model requires screening approximately 15% of the total population (17% at CUMC and 12% at CSMC). In contrast, a strategy targeting individuals with at least one traditional risk factor (CA19-9, type 2 diabetes, or pancreatitis) achieves lower sensitivity—28% at CUMC (96 out of 338 cases) and 44% at CSMC (95 out of 216 cases)—while requiring screening of 16% of the population (24,950 out of 157,405 at CUMC and 14,311 out of 92,300 at CSMC).

More importantly, among those PC cases (169 in CUMC and 108 in CSMC), over 50% and over 85% in the CUMC and CSMC models had neither (Table 2). This suggests that the EHR-based model captures high-risk individuals who would not be identified using single risk factors or genetic variants alone.

With genetic data available at CSMC, we identified 1500 individuals carrying genetic variants associated with PC (Supplementary Table 3), including 130 who were diagnosed with PC. Of these, our dataset included 50 individuals, all of whom had PC, resulting in a PPV of 1. The remaining 80 PC cases were excluded during data preprocessing, as described in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Discussion

In this study, we presented a novel approach that leverages embeddings of medical concept names from pre-trained models, including LLMs, to develop an early prediction model for PC. We hypothesized that these embeddings, which capture contextual semantics, would improve prediction performance compared to models trained from scratch with randomly initialized embeddings. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated our approach using EHR data from CUMC and validated the findings with external EHR data from CSMC.

Our results indicate that GPT embeddings have the potential to enhance prediction performance when encoding patient data for predictive modeling (Table 1, Fig. 2, and Supplementary Table 2). While Mistral embeddings had the largest dimensionality (4096), GPT embeddings—particularly those as small as 32 dimensions—performed comparably or even better in certain settings (e.g., 0–3 months, 12–36 months; p-value < 0.05). Even among GPT models, the 1536-dimensional embeddings did not consistently outperform their 32-dimensional counterparts. This counterintuitive result may reflect redundancy or noise introduced by very high-dimensional embeddings—especially given the short length of the input text—whereas compact embeddings may act as a form of regularization.

We further observed that fine-tuning had a greater impact on smaller embeddings (e.g., 32-dimensional GPT), whereas larger embeddings (e.g., 1536-dimensional GPT) showed limited performance gains. This pattern suggests that low-dimensional representations benefit more from task-specific adaptation, while higher-dimensional embeddings may already encode sufficient semantic richness from pretraining. These findings support future strategies that jointly consider embedding dimensionality and fine-tuning—particularly in resource-constrained settings or when computational efficiency is a priority.

Beyond embedding experiments, we explored the trade-offs between multi-label classification models, which predict risk across multiple time intervals, and binary classification models, which require separate models for each prediction interval. Our analysis highlighted key considerations when selecting between these model types.

For instance, in multi-label classification models, predictions for earlier time intervals (3–6, 6–12, 12–36, and 36–60 months) were influenced by data from the 0–3 month interval, which had a larger sample size and stronger PC-related signals. Notably, many of the top predictive features, such as “disorder of pancreas”, appeared in both the 0–3 month and 36–60 month predictions, despite almost no PC patients exhibiting this condition at earlier time points (Supplementary Fig. 6). Instead, many individuals in the control group had this condition but did not develop PC, leading to misclassifications and high false positive rates.

These challenges were also observed in CancerRiskNet, which employed a similar multi-label classification framework for PC prediction. The study reported that over 50% of the top 10 predictors for the 0–6 month interval also appeared among the top predictors for 24–36 months, with “unspecified jaundice” being one such feature12. These findings underscore a potential limitation of multi-label architectures: when dominant features near the diagnosis window are highly predictive, they can propagate into earlier intervals, potentially due to model leakage or overlapping feature attribution.

Compared to the national Danish registry used in CancerRiskNet, the institutional EHR datasets from CUMC and CSMC are smaller in scale and potentially more heterogeneous in terms of coding practices, data completeness, and care patterns—factors that may contribute to lower generalizability and predictive performance. For predicting PC occurrence within 36 months, our baseline model achieved an AUROC of 0.694 at CUMC and 0.744 at CSMC, compared to CancerRiskNet’s AUROC of 0.88. When excluding 0–3 month data, performance in our models remained robust (AUROC = 0.737 at CUMC and 0.771 at CSMC), though still lower than CancerRiskNet’s AUROC of 0.83 under the same exclusion. However, by incorporating LLM-based embeddings, model performance improved further (AUROC = 0.761 at CUMC and 0.811 at CSMC), demonstrating their incremental predictive value.

Another interesting observation was that excluding 0–3 month data led to a notable performance drop for 3–6 month predictions, with AUROC decreasing from 0.856 to 0.763 in CUMC and from 0.884 to 0.870 in CSMC, despite data augmentation (Table 2). However, performance improved for earlier predictions (6–12 and 12–36 months in CUMC, and 6–12 months in CSMC), suggesting that advanced symptoms appearing within 0–3 months of diagnosis may also be present up to 6 months prior but are unlikely to emerge beyond that timeframe.

We further observed that the large performance gap for 6–12 month predictions between CUMC and CSMC (Fig. 2) likely reflects differences in patient characteristics rather than data structure. For instance, features highly predictive of PC near diagnosis (e.g., “disorder of pancreas”) were largely absent in earlier intervals for CUMC cases but appeared more frequently among controls, increasing false positives and depressing model performance when 0–3 month data were included. After excluding this window, CUMC model performance improved substantially (AUROC = 0.82), becoming comparable to that of CSMC.

In comparison to these multi-classification models, when we tested binary classification models trained on the specified time windows without data leakage concerns, previously unseen features—absent from the multi-label model’s LIME outputs—such as kidney-related conditions emerged as one of top ranked features in 6-12 and 12–36 month window for both CUMC and CSMC (Supplementary Fig. 4). This finding is consistent with emerging studies suggesting that renal abnormalities—such as kidney disease or metabolic dysregulation—may be early systemic manifestations associated with PC development13. Similarly, liver-related features were also prominent, supporting recent evidence that conditions like nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and cirrhosis are associated with increased PC risk14,15. These observations may open new directions for exploring multi-organ signatures of PC risk and demonstrate the potential of AI-based models to uncover early, non-obvious risk patterns beyond traditional clinical indicators.

Comparing the PPVs of the EHR-based model with those of known risk factors highlights that the model identifies high-risk individuals based on longitudinal medical patterns, which single risk factors fail to capture (Table 2). This underscores the clinical utility of the EHR-based model as a complementary screening tool to traditional risk factors, potentially improving targeted screening strategies. For genetic variants, the PPV was 1 in our dataset. However, individuals with genetic variants or a family history of PC account for less than 10% of all PC cases16. Our dataset showed an even smaller proportion—less than 3% (total dataset: 50/1,781~2.8%; test set: 5/216~2.3%)—suggesting potential undertesting for genetic variants.

To further investigate the model’s predictive capacity beyond traditional risk factors, we examined clinical characteristics of PC patients with and without known risk factors (Supplementary Table 5). While some demographic differences were observed in CUMC (e.g., gender and ethnicity), no significant differences were found in CSMC. Among the top 20 most frequent comorbidities, several conditions—including inflammatory digestive disorders, headache, and low back pain—were found exclusively among PC patients without traditional risk factors. These findings suggest that the EHR-based model may be capturing subtle or underrecognized patterns of comorbidities that are not part of standard PC risk profiles. Given that approximately 50% of PC patients, for example, in the 6–12 month prediction window, had no documented traditional risk factors, this highlights the model’s potential to detect high-risk individuals who would otherwise remain unidentified through conventional screening criteria.

Lastly, as a supplementary analysis (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Note 5), we tested our hypothesis that a subset of individuals would consistently be identified as high-risk across different models (e.g., baseline, GPT embedding, RGCN embedding, Mistral embedding models), regardless of model variations in embedding size or training approach (e.g., freezing vs. fine-tuning embeddings). Identifying such a consistently high-risk group could inform strategies for targeted screening using EHR-based prediction models (Supplementary Fig. 7). Supporting this hypothesis, we found that the risk scores of consistently identified high-risk individuals were significantly higher (p < 0.0001, Supplementary fig. 8A and Supplementary Fig. 8B) compared to the other high-risk individuals. Additionally, predictive feature similarity was significantly greater among these individuals than among the other high-risk individuals (p < 0.0001, Supplementary Fig. 8C). These findings suggest that focusing on consistently high-risk individuals across multiple models could serve as an alternative approach to defining a targeted screening population for PC.

Our study is not without limitations. First, although our results demonstrate the potential of the EHR-based model as an independent risk assessment tool that complements traditional risk factors and genetic variants, direct comparisons between the EHR-based model and individual risk factors remain challenging. This is because the absence of certain risk factors in EHR data may reflect incomplete documentation in structured fields rather than a true absence. For example, familial pancreatic cancer status—an important clinical risk factor and key criterion in screening guidelines such as CAPS—is typically recorded in unstructured clinical notes (e.g., history and physical exams, oncology consults) rather than in structured data fields. We plan to incorporate unstructured text using NLP methods in future work to improve the capture of family history and enhance early detection efforts. Second, achieving high precision in identifying PC in a real-world population could be more difficult, as the actual prevalence of PC is considerably lower than in our evaluation cohort. According to estimates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, approximately 32 per 100,000 individuals were living with PC in the U.S. in 2022, compared to 215 per 100,000 in our hypothetical cohort. Finally, our prediction model relies solely on longitudinal medical condition data and does not incorporate other potentially predictive features, such as lab measurements or medications. While these additional data sources could further enhance predictive performance, our study does not yet fully leverage the multimodal nature of EHR data.

As LLMs and deep learning technologies continue to evolve, sustained efforts to integrate EHR data with AI-driven models will be essential for advancing early disease detection and risk stratification beyond PC. The approach demonstrated in this study, leveraging LLM-derived embeddings to enhance predictive modeling, is broadly applicable across a wide range of clinical prediction tasks and can be seamlessly integrated into diverse EHR-based modeling frameworks.

To implement the EHR-based model in clinical practice, we propose a flexible risk-thresholding strategy tailored to different clinical objectives, as illustrated in Table 3. For instance, a high threshold could be selected to prioritize specificity and maximize PPV, making the model suitable for targeted imaging triage. Alternatively, a more inclusive threshold could be calibrated to achieve a predefined sensitivity target (e.g., 20%) to capture more cases across a broader population.

These thresholds can be informed by cost-effectiveness analyses that incorporate downstream imaging costs, reimbursement frameworks, and patient preferences (e.g., willingness to pay or tolerate false positives). Once a threshold is selected, the model can be integrated into EHR systems to passively monitor at-risk individuals over time. Patients who exceed the risk threshold could then be flagged for follow-up actions, such as non-invasive imaging (e.g., MRI or endoscopic ultrasound), enabling prospective evaluation of early detection performance and its impact on clinical outcomes.

To ensure reliable interpretation of predicted risk probabilities in clinical settings, calibration of the risk scores is also critical. In our evaluation, the multi-label classification model benefited from post-hoc calibration, while the binary prediction model already exhibited well-calibrated risk scores (Supplementary Fig. 9). Well-calibrated outputs help align model predictions with observed PC incidence rates, which is essential when applying thresholds for population screening or imaging referral.

Beyond predictive accuracy, real-world adoption of the model depends on thoughtful integration into clinical workflows and clear model transparency. While seamless EHR integration is essential for real-time monitoring, alert thresholds should be calibrated to minimize alert fatigue by prioritizing high specificity. Equally important is interpretability—features such as risk trajectories, heatmaps of contributing conditions, and plain-language summaries (Supplementary Fig. 10) can promote clinician trust and support shared decision-making. These considerations are key to facilitating acceptance and enabling scalable early detection strategies.

Methods

The retrospective study protocol using de-identified patient data was reviewed and approved by the Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) Institutional Review Board (IRB protocols: AAAL0601, AAAS1319, and AAAV8800) and by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC) Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol: STUDY00003395), with a waiver of informed consent granted by both institutions due to the use of non-identifiable data and minimal risk to participants.

Patient data

We used EHR data in the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model (CDM) format17 from CUMC and CSMC. Pancreatic cancer (PC) cases were identified using diagnosis codes for malignant neoplasms of the pancreas, excluding those with a prior history of other cancers. Controls were drawn from the general patient pool after excluding individuals with any cancer-related terms (e.g., “malig,” “adenocarcinoma”), recent diagnoses within the past two years, or fewer than five recorded medical conditions. Patients under age 18 or over 100 were also excluded. This resulted in 3300 cases and 785,335 controls from CUMC, and 1781 cases and 484,515 controls from CSMC (Fig. S1 and Table S1). Detailed characteristics of identified cases and controls are discussed in the Supplementary Note 1, with additional analysis demonstrating that the discrepancies in age between cases and controls have no significant impact on model performance (Supplementary Fig. 2).

RGCN - Embeddings from graph

We constructed a knowledge graph based on the OMOP CDM, leveraging its hierarchical ancestor-descendant structure. Using this graph, we trained a Relational Graph Convolutional Network (RGCN)11 to capture the complex relationships between concepts and generate contextually rich embeddings for each concept ID. We optimized the mean reciprocal rank (MRR), a metric assessing the accuracy of predicted true edges within the graph. Additional details on the RGCN model development and training process are provided in the Supplementary Note 2.

GPT and Mistral - Embeddings from LLMs

We generated embeddings for each medical condition name associated with OMOP concept IDs using two LLMs (Fig. 1A): the OpenAI text-embedding-3-small model (referred to as OpenAI GPT or GPT) and the Mistral sentence transformer (Salesforce/SFR-Embedding-Mistral) trained on top of E5-mistral-7b-instruct and Mistral-7B-v0.1. Medical condition names were obtained from the OMOP vocabulary, which provides standardized names for each concept ID in the structured EHR data. These names were used as input to the LLMs for embedding generation (Supplementary Note 3). For GPT embeddings, we tested two sizes: 32 and 1536 dimensions, while the Mistral model generates embeddings of 4096 dimensions. These varied sizes allowed us to assess the impact of embedding dimensionality on the ability to capture semantic relationships relevant to the downstream prediction task.

Model architecture

We developed two types of prediction models based on a Transformer architecture: (1) a multi-label classification model predicting PC risk at 0–3, 3–6, 6–12, 12–36, and 36–60 months before diagnosis (Figs. 1B), and (2) three binary classification models predicting PC risk at 3–6, 6–12, and 36–60 months before diagnosis (Fig. 1C).

Case-control sampling and prediction intervals

We stratified PC cases into time windows of 0–3, 3–6, 6–12, and 12–36 months prior to diagnosis by evaluating the time gap between patient’s last recorded medical condition and their diagnosis date. Controls—individuals with no cancer diagnosis—were selected to represent the general population without cancer. To reduce the chance of including individuals with undiagnosed cancer, we excluded medical conditions from the two years prior to each control’s last recorded medical condition. We applied the same control group across all prediction windows to reflect real-world clinical settings where PC is rare. This consistent sampling approach enables evaluation of the model’s ability to identify increasingly rare cases as the prediction window extends further from the diagnosis date.

To mitigate potential data leakage from conditions recorded shortly before diagnosis, we developed an additional multi-label classification model that excluded the 0–3 month data. This data was instead used to augment samples for the 3–6 month prediction window.

We also trained binary classification models to address the limited sample sizes in earlier intervals of the multi-label model. For example, data from the 0–3 and 3–6 month intervals were used to augment the 6–12 month prediction window, and data from the 0–3, 3–6, and 6–12 month intervals were used to augment the 12–36 month prediction window. Specifically, for patients in the 3–6 month group (i.e., whose last recorded medical condition occurred between 3 and 6 months before diagnosis), we removed more recent conditions until the last remaining condition fell within the 12–36 month interval (Fig. 1C). Following the data selection process in Supplementary fig. 1, we included only samples with at least five condition records.

Model training

For models utilizing pre-trained embeddings, we initialized the model with these embeddings, while for the baseline, we used PyTorch’s nn.Embedding18, which randomly initializes embeddings for each OMOP concept ID at the start of training.

Pre-trained embeddings encode semantic knowledge from large-scale corpora, potentially improving downstream predictive tasks. However, the effectiveness of these embeddings in EHR-based predictive models remains uncertain. To assess their utility, we tested two training strategies:

-

Freezing the embeddings (keeping them non-trainable while learning only the attention weights). This preserves the pre-trained semantic structure, preventing the model from altering these representations based on the training data. Freezing is useful when pre-trained embeddings already provide meaningful representations, and additional training could introduce noise or overfit to dataset-specific biases.

-

Fine-tuning the embeddings (allowing them to be updated during training). This allows embeddings to adapt to dataset-specific characteristics, potentially improving performance when pre-trained embeddings do not fully capture EHR-specific nuances.

We evaluated 12 different models, varying by training strategy (freezing vs. fine-tuning), embedding type (PyTorch’s nn.Embedding, RGCN, GPT, Mistral), and embedding size (Supplementary Table 2). To highlight the effectiveness of GPT embeddings, we focused on the comparison between the Baseline and GPT embedding models, as shown in Table 1. The dataset was split into 60% training, 20% validation, and 20% testing. Additionally, we incorporated positional encoding based on the age at which medical conditions were recorded, enhancing the model’s ability to capture temporal dependencies in the data.

Statistical analysis

We conducted statistical analyses to compare demographic characteristics, model performance, and risk score distributions across patient groups. Bootstrap testing was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals and p-values for performance metrics, including AUROC, AUPRC, and maximum F1-score. For continuous variables (e.g., age, risk scores, length of diagnosis sequences, cosine similarities, and sensitivities across specificity thresholds), we used the Mann–Whitney U test to compare medians. For categorical variables (e.g., gender, race, and ethnicity), we applied the Chi-square test.

Data availability

Sharing EHR data is prohibited by HIPAA regulations. To ensure compliance, our study results from two independent institutions were obtained by sharing the code, which is available at https://github.com/jp4147/pdac_tf.

Change history

14 October 2025

The wrong Supplementary file was originally published with this article; it has now been replaced with the correct. The original article has been corrected.

References

Siegel, R. L., Kratzer, T. B., Giaquinto, A. N., Sung, H. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 75, 10–45 (2025).

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2021. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; (2021).

Owens, D. K. et al. Screening for pancreatic cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement. JAMA 322, 438–444 (2019).

Farr, K. P. et al. Imaging modalities for early detection of pancreatic cancer: current state and future research opportunities. Cancers 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14102539.

Zhao, Y. et al. Liquid biopsy in pancreatic cancer - Current perspective and future outlook. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1878, 188868 (2023).

Dash, S., Shakyawar, S. K., Sharma, M., Kaushik, S. Big data in healthcare: management, analysis and future prospects. J. Big Data-Ger. 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0217-0.

Li, L. et al. A scoping review of using Large Language Models (LLMs) to investigate Electronic Health Records (EHRs). arXiv preprint arXiv:240503066 (2024).

Guevara, M. et al. Large language models to identify social determinants of health in electronic health records. NPJ Digit Med. 7, 6 (2024).

Yan, C. et al. Large language models facilitate the generation of electronic health record phenotyping algorithms. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocae072.

Chen, Y. & Zou, J. GenePT: A Simple But Effective Foundation Model for Genes and Cells Built From ChatGPT. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.16.562533.

Patterson, J., Tatonetti N. KG-LIME: predicting individualized risk of adverse drug events for multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapy. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocae155. (2024).

Placido, D. et al. A deep learning algorithm to predict risk of pancreatic cancer from disease trajectories. Nat Med. 29, 1113–1122. (2023)

Malyszko, J., Tesarova, P., Capasso, G. & Capasso, A. The link between kidney disease and cancer: complications and treatment. Lancet 396, 277–287 (2020).

Sakaue, T., Terabe, H., Takedatsu, H. & Kawaguchi, T. Association between nonalcholic fatty liver disease and pancreatic cancer: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and antidiabetic medication. Hepatol. Res. 54, 729–735 (2024).

Park, J. H., Hong, J. Y., Han, K., Kan,g W., Park, J. K. Increased risk of pancreatic cancer in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep-Uk;12, doi: ARTN 10681 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14856-w.

Daly, M. B. et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 19, 77–102 (2021).

Ahmadi, N., Peng, Y., Wolfien, M. & Zoch, M., Sedlmayr, M. OMOP CDM can facilitate data-driven studies for cancer prediction: a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, doi: ARTN 11834 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911834. (2022).

Subramanian, V. Deep Learning with PyTorch: A practical approach to building neural network models using PyTorch: Packt Publishing Ltd. (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a National Institutes of Health grant K25CA267052 (JP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H. and N. T. are co-senior authors. J.P.1, J.P.2, and T.G. conceived the concept, with J.P.1 leading the project and developing the original draft. J.P.2 and T.G. participated in the study’s conceptualization, methodology development, investigation, and visualization, and provided critical review and editing of the manuscript. N.T. provided expertise, critical review, and guidance in bioinformatics data mining and analytical approach, while C.H. contributed clinical expertise in reviewing the study. N.T. also supported access to CSMC resources, and J.M.C. contributed to the investigation at CSMC through analysis of CSMC data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J., Patterson, J., Acitores Cortina, J.M. et al. Enhancing EHR-based pancreatic cancer prediction with LLM-derived embeddings. npj Digit. Med. 8, 465 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01869-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01869-8